To illustrate the difference, I'll make a variable called user, which will be an object. On this object we'll specify one property, name. Set name equal to the string, your name, in this case I'll set it equal to the string Andrew:

var user = {

name: 'Andrew'

};

Then we can define a method on the user object. Right after name, with my comma at the end of the line, I'll provide the method sayHi, setting it equal to an arrow function (=>) that doesn't take any arguments. For the moment, we'll keep the arrow function really simple:

var user = {

name: 'Andrew',

sayHi: () => {

}

};

All we'll do inside sayHi is use console.log to print to the screen, inside of template strings Hi:

var user = {

name: 'Andrew',

sayHi: () => {

console.log(`Hi`);

}

};

We're not using template strings yet, but we will later so I'll use them here. Down following the user object, we can test out sayHi by calling it, user.sayHi:

var user = {

name: 'Andrew',

sayHi: () => {

console.log(`Hi`);

}

};

user.sayHi();

I'll call it then save the file, and we would expect that Hi prints to the screen because all our arrow function (=>) does is use console.log to print a static string. Nothing in this case will cause any problems; you'd be able to swap out a regular function for an arrow function (=>) without issue.

Now the first issue that will arise when you use arrow functions is the fact that arrow functions do not bind a this keyword. So if you are using this inside your function, it's not going to work when you swap it out for an arrow function (=>). Now, this binding; refers to the parent binding, in our case there is no parent, function so this would refer to the global this keyword. Now we have our console.log that does not use this, I'll swap it out for a case that does.

We'll put a period after Hi, and I'll say I'm, followed by the name, which we would usually be able to access via this.name:

var user = {

name: 'Andrew',

sayHi: () => {

console.log(`Hi. I'm ${this.name}`);

}

};

user.sayHi();

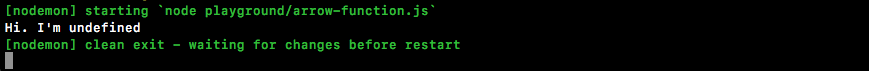

If I try to run this code, it is not going to work as expected; we're going to get Hi I'm undefined printing to the screen, as shown here:

In order to fix this, we'll look at an alternative syntax to arrow functions that's great when you're defining object literals, as we are in this case.

After sayHi, I'll make a new method called sayHiAlt using a different ES6 feature. ES6 provides us a new way to make methods on objects; you provide the method name, sayHiAlt, then you go right to the parentheses skipping the colon. There's also no need for the function keyword, even though it is a regular function it's not an arrow function (=>). Then we move on to our curly braces as shown here:

var user = {

name: 'Andrew',

sayHi: () => {

console.log(`Hi. I'm ${this.name}`);

},

sayHiAlt() {

}

};

user.sayHi();

Inside here I can have the exact same code we have in the sayHi function, but it is going to work as expected. It's going to print Hi. I'm Andrew. I'll call sayHiAlt down following instead of the regular sayHi method:

var user = {

name: 'Andrew',

sayHi: () => {

console.log(`Hi. I'm ${this.name}`);

},

sayHiAlt() {

console.log(`Hi. I'm ${this.name}`);

}

};

user.sayHiAlt();

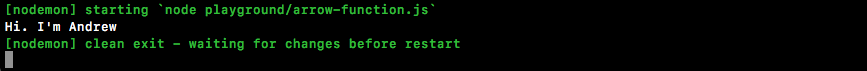

And in Terminal, you can see Hi. I'm Andrew, prints to the screen:

The sayHiAlt syntax is a syntax that you can use to solve this problem when you create functions on object literals. Now that we know that the this keyword does not get bound, let's explore one other quirk that arrow functions have, it also does not bind the arguments array.