![]()

![]()

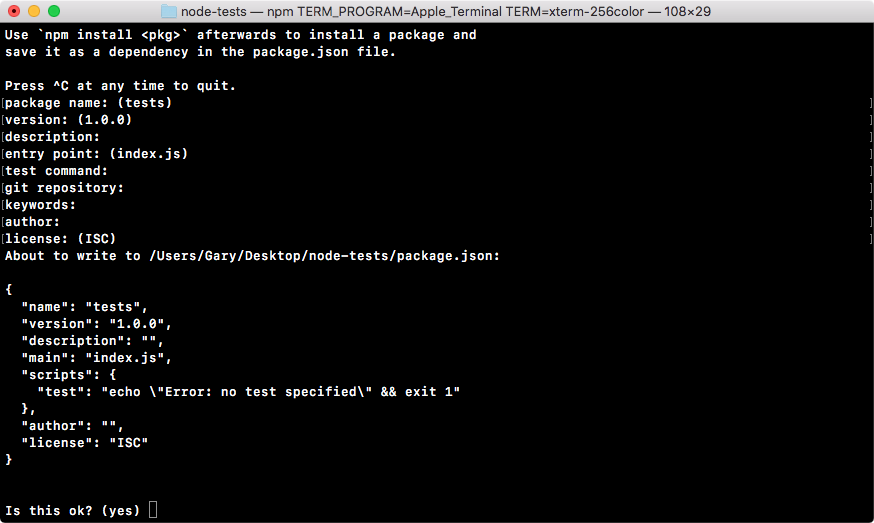

Copyright © 2018 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing or its dealers and distributors, will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

Acquisition Editor: Ben Renow-Clarke

Content Development Editor: Monika Sangwan

Technical Editors: Anupam Tiwari, Gaurav Gavas

Copy Editors: Safis Editing, Tom Jacob

Project Editor: Suzanne Coutinho

Proofreader: Safis Editing

Indexer: Pratik Shirodkar

Production Coordinator: Nilesh Mohite

First published: January 2018

Production reference: 1300118

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham

B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78839-554-0

Mapt is an online digital library that gives you full access to over 5,000 books and videos, as well as industry leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career. For more information, please visit our website.

Spend less time learning and more time coding with practical eBooks and Videos from over 4,000 industry professionals

Improve your learning with Skill Plans built especially for you

Get a free eBook or video every month

Mapt is fully searchable

Copy and paste, print, and bookmark content

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at service@packtpub.com for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters, and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

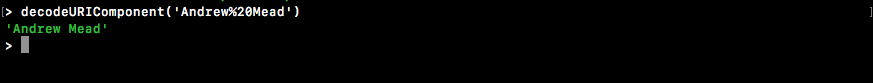

Andrew Mead is a full-stack developer living in beautiful Philadelphia! He launched his first Udemy course in 2014 and had a blast teaching and helping others. Since then, he has launched 3 courses with over 21,000 students and over 1,900 5-star reviews.

Andrew currently teaches Node, Gulp, and React. Before he started teaching, he created a web app development company. He has helped companies of all sizes launch production web applications to their customers. He has had the honor of working with awesome companies such as Siemens, Mixergy, and Parkloco. He has a Computer Science degree from Temple University, and he has been programming for just over a decade. He loves creating, programming, launching, learning, teaching, and biking.

If you're interested in becoming an author for Packt, please visit authors.packtpub.com and apply today. We have worked with thousands of developers and tech professionals, just like you, to help them share their insight with the global tech community. You can make a general application, apply for a specific hot topic that we are recruiting an author for, or submit your own idea.

Welcome to Learning Node.js Development. This book is packed with a ton of content, projects, challenges and real-world examples, all designed to teach you Node by doing. This means you'll be getting your hands dirty early on in the upcoming chapters writing some code, and you'll be writing code for every project. You will be writing every line of code that powers our applications. Now, we would require a text editor for this book. We have various text editor options that you can use. I always recommend using Atom, which you can find at atom.io. It's free, open-source, and it's available for all operating systems, namely Linux, macOS, and Windows. It's created by the folks behind GitHub.

All the projects in the book are fun to build and they were designed to teach you everything required to launch your own Node app, from planning to development and testing to deploying. Now, as you launch these different Node applications and move through the book, you will run into errors, which is bound to happen. Maybe something doesn't get installed as expected, or maybe you try to run an app and instead of getting the expected output, you get a really long obscure error message. Don't worry, I am there to help. I'll show you tips and tricks to get pass through those errors in the chapters. Let's go ahead and get to it.

This book targets anyone looking to launch their own Node applications, switch careers, or freelance as a Node developer. You should have a basic understanding of JavaScript in order to follow this book.

Chapter 1, Getting Set Up, talks about what Node is and why you want to use it. In this chapter, you'll learn Node installation and by the end of the chapter, you'll be able to run your first Node application.

Chapter 2, Node Fundamentals - Part 1, talks about building Node applications. The Node Fundamentals topic has been divided into 3 parts. Part 1 of this topic includes module basics, requiring own files, and third-party NPM modules.

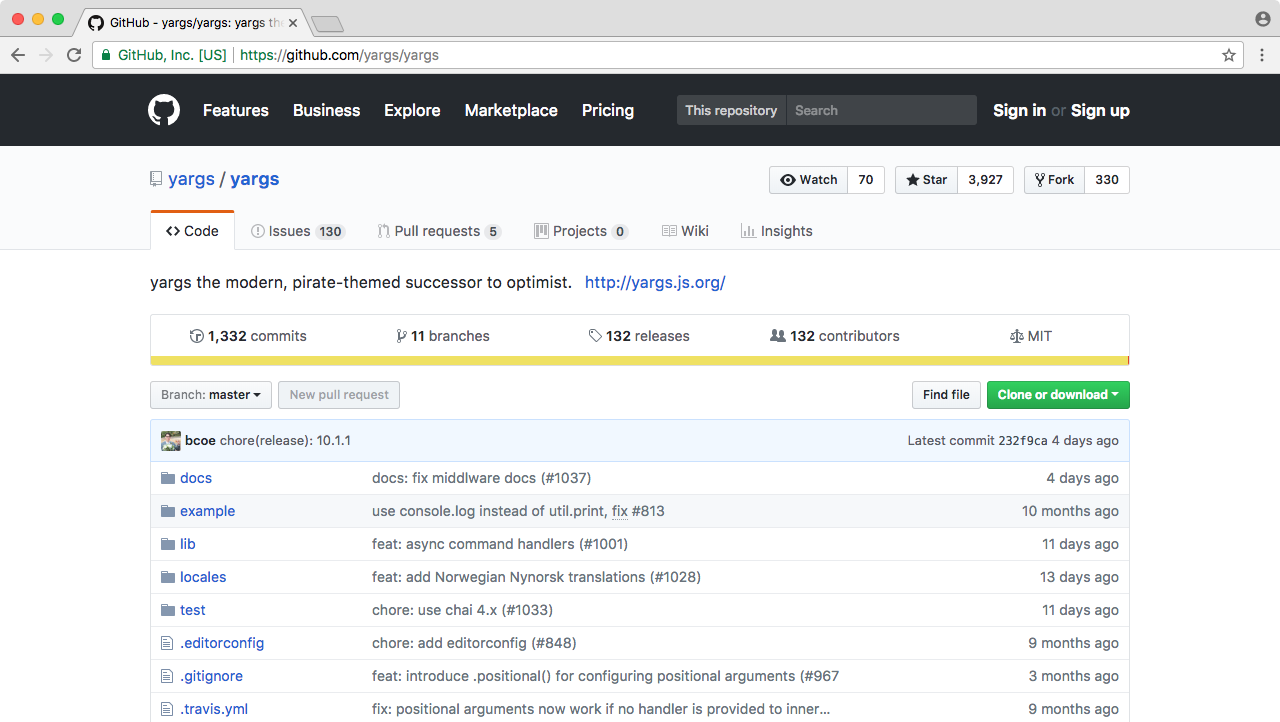

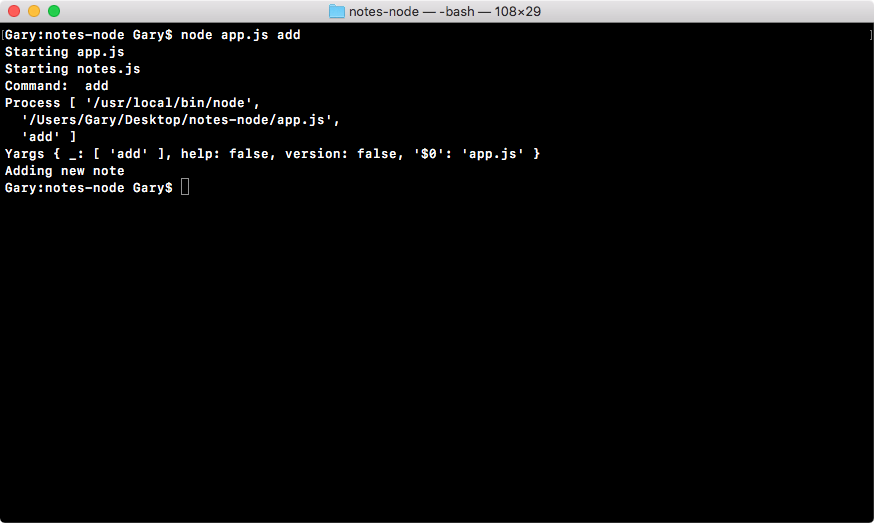

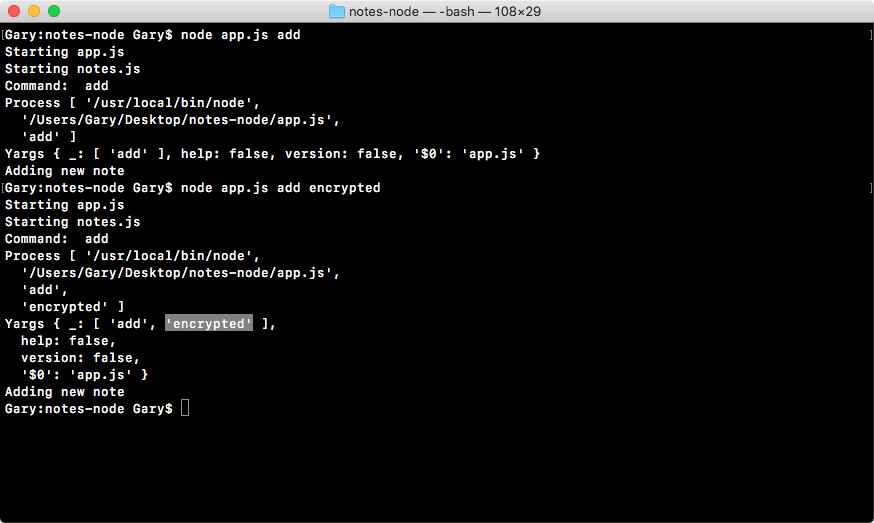

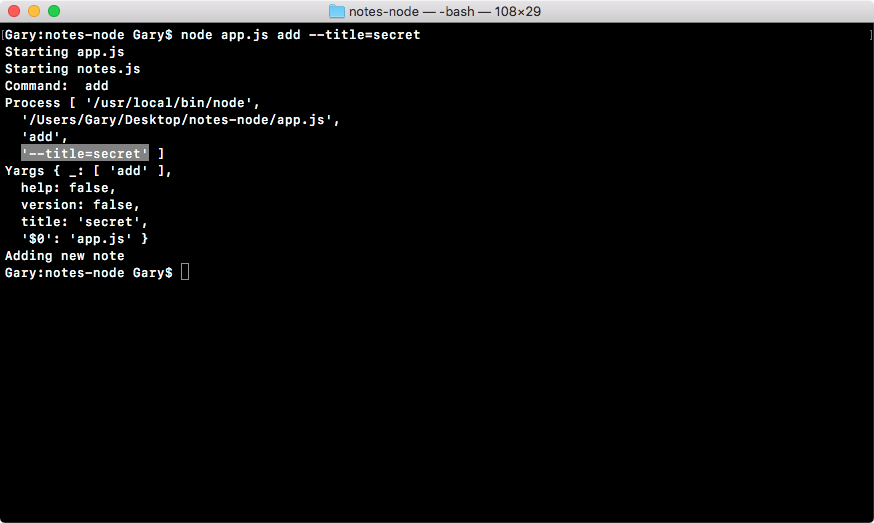

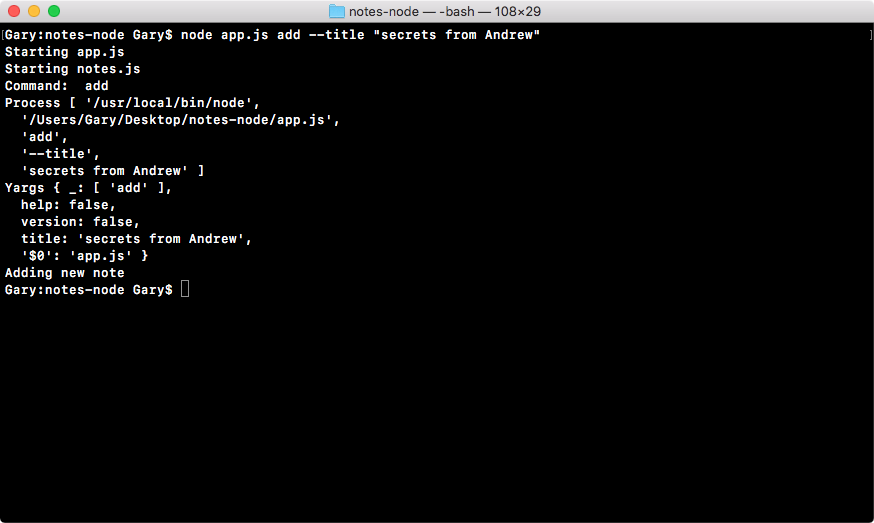

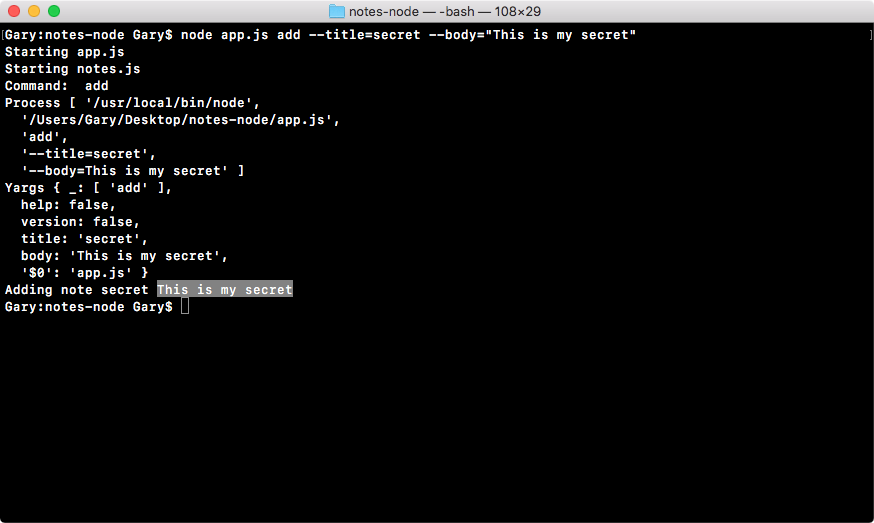

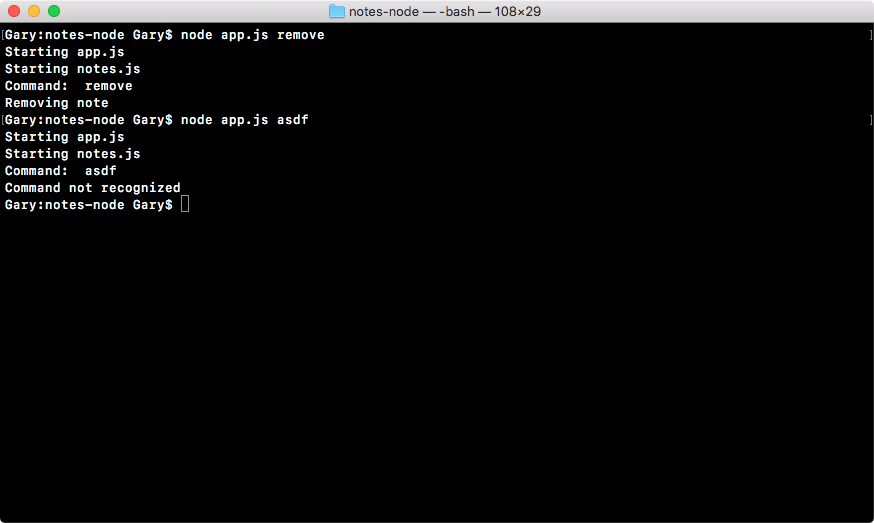

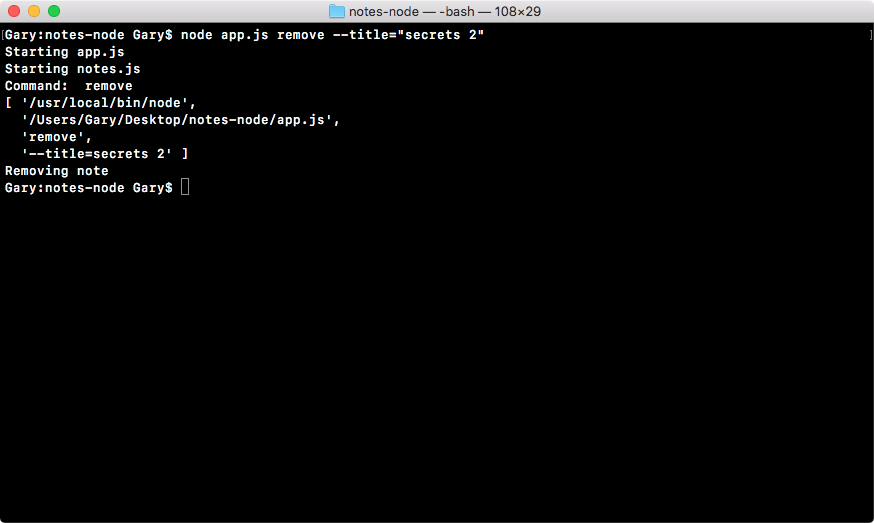

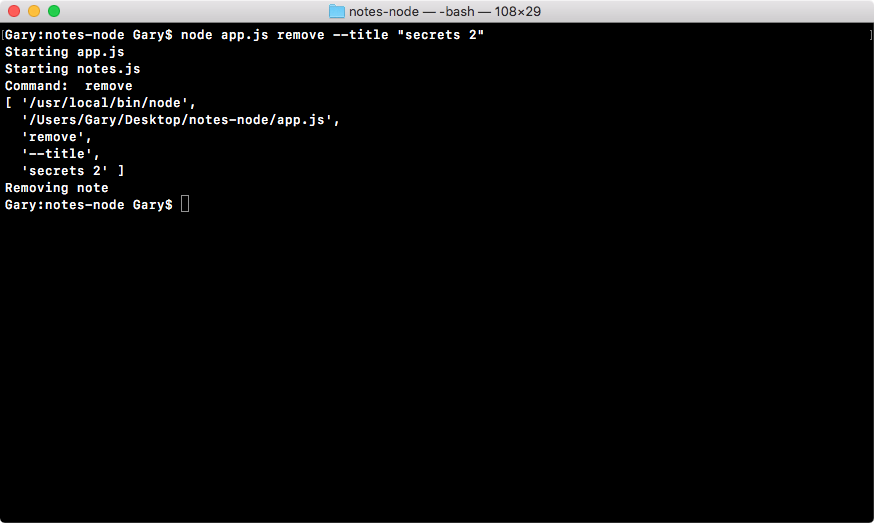

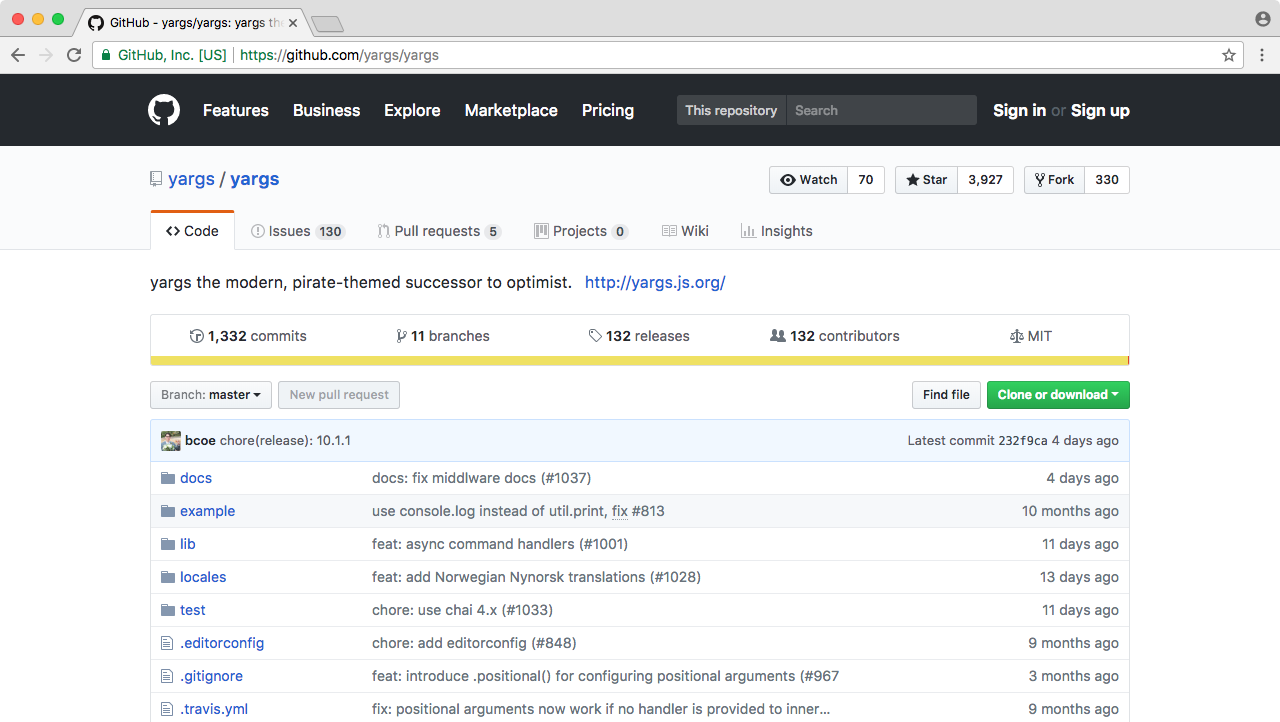

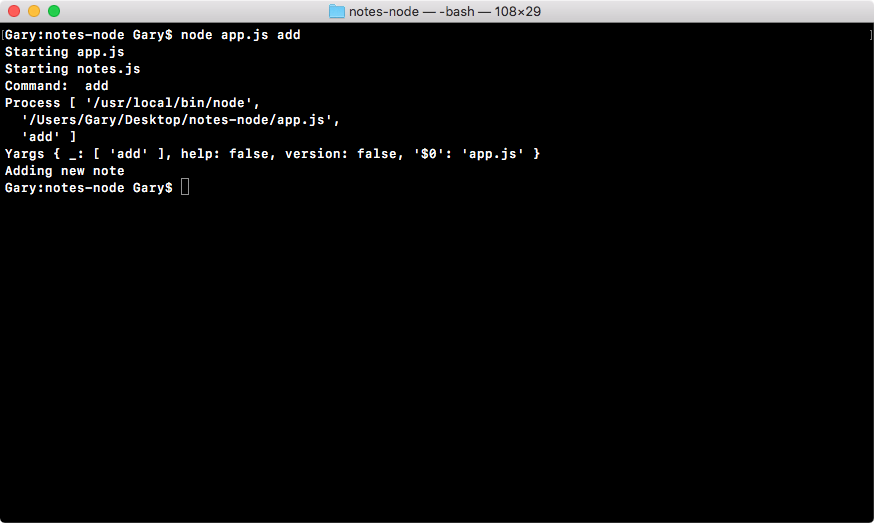

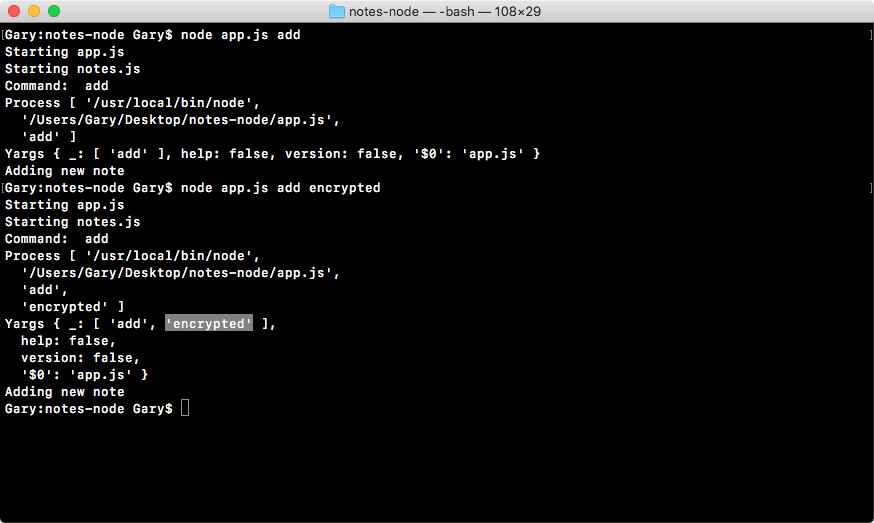

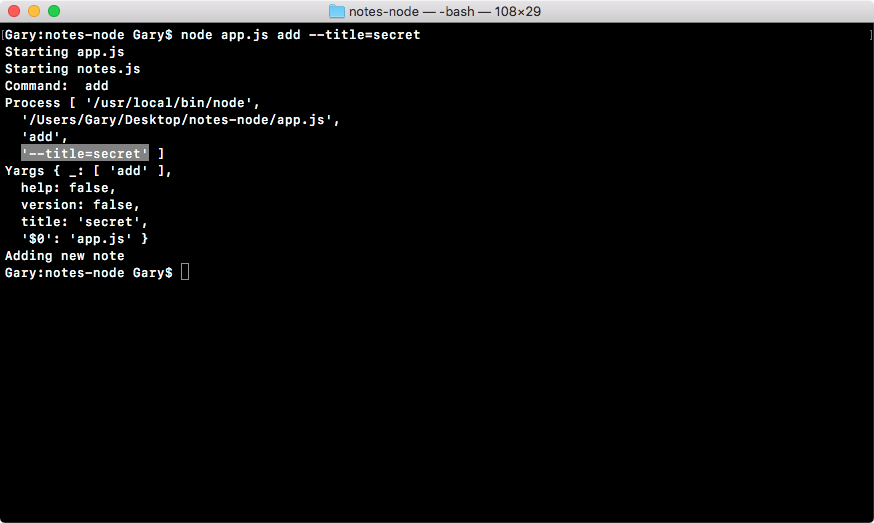

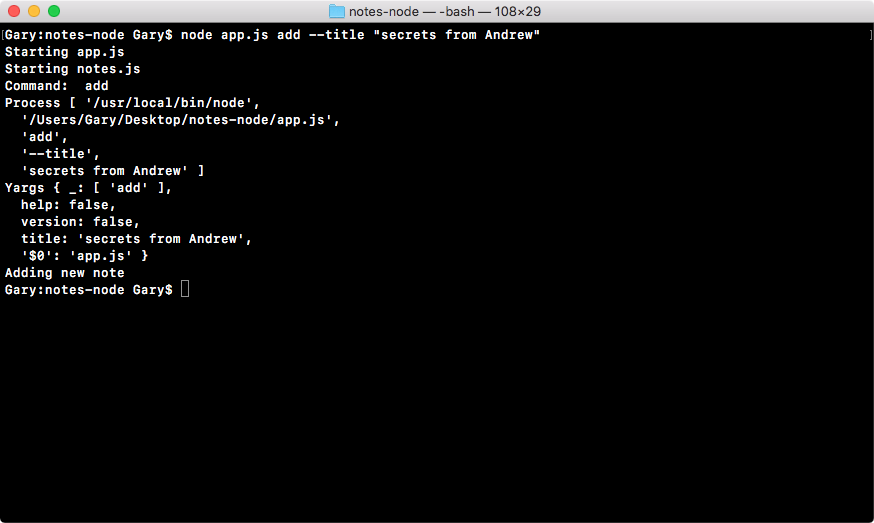

Chapter 3, Node Fundamentals - Part 2, continues our discussion on some more Node fundamentals. This chapter explores yargs, JSON, the addNote function, and refactor, moving functionality into individual functions and testing the functionality.

Chapter 4, Node Fundamentals - Part 3, includes things such as read and write from the file system. We'll look into advanced yargs configuration, debugging broken apps, and some new ES6 functions.

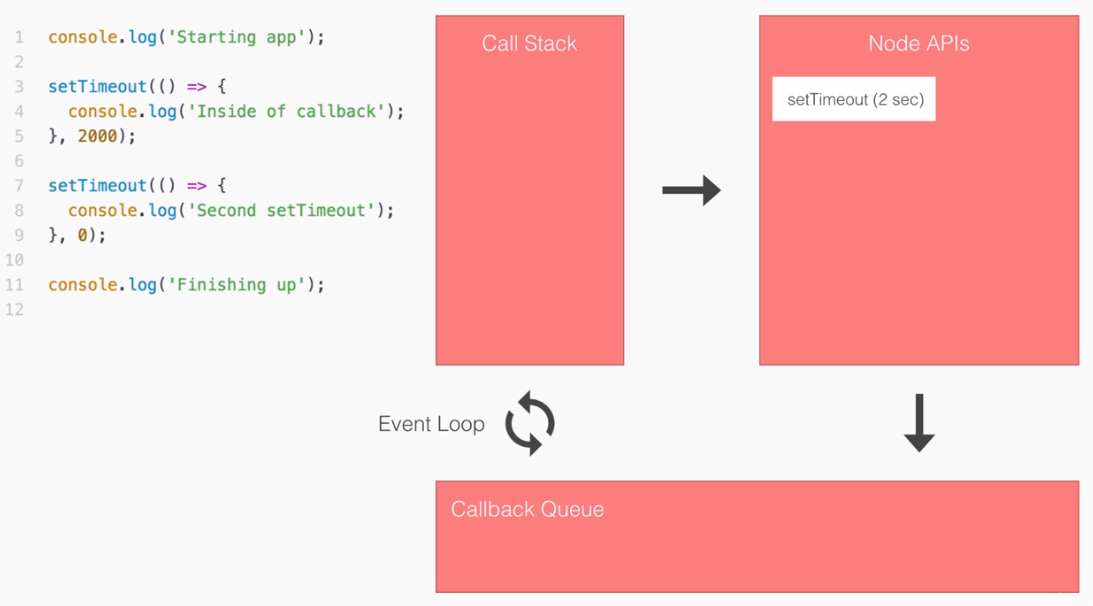

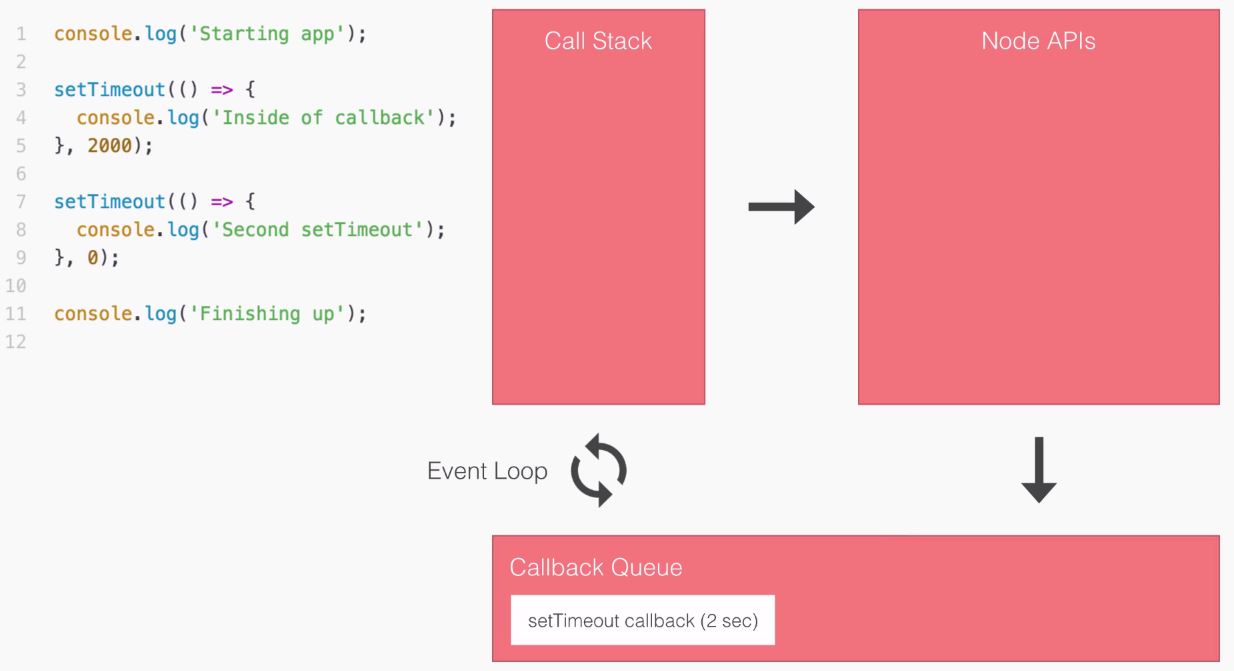

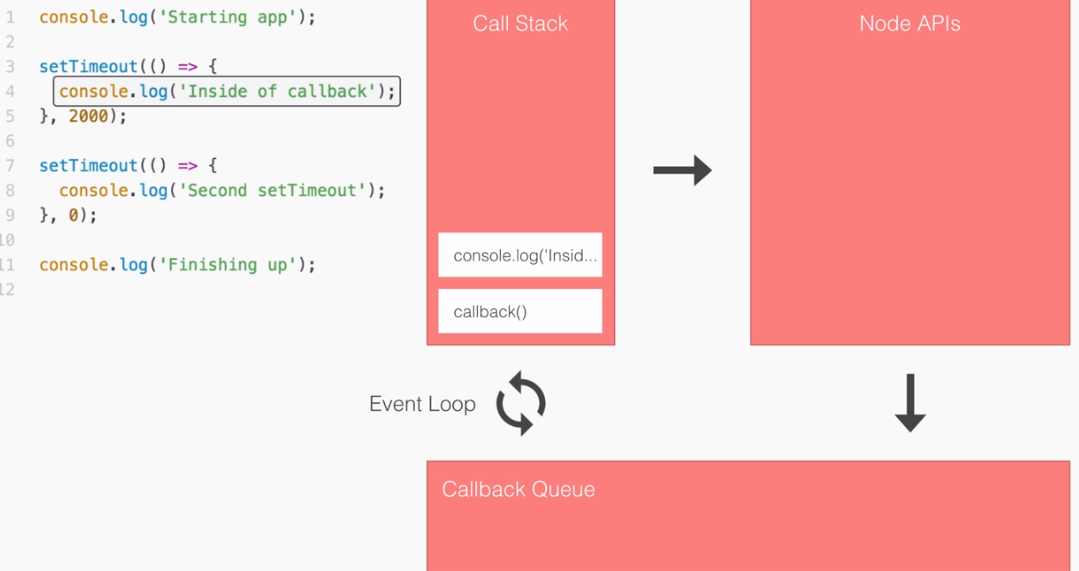

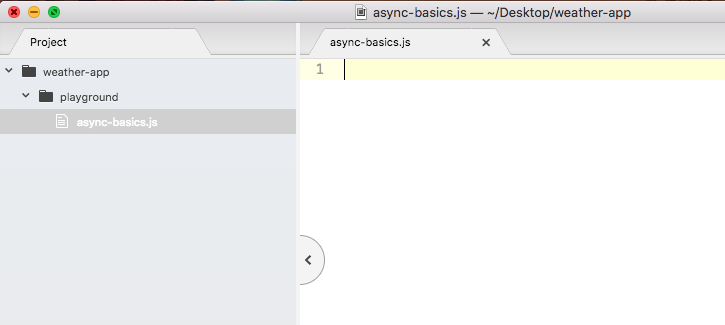

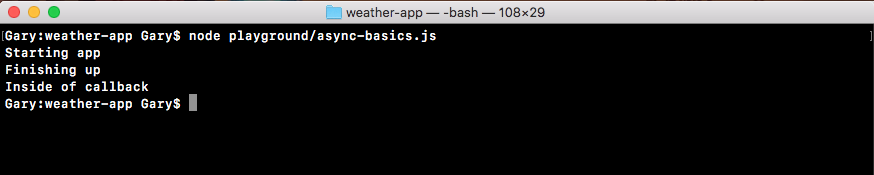

Chapter 5, Basics of Asynchronous Programming in Node.js, covers basic concepts, terms, and technologies related to the async programming, making it super-practical and using it in our weather application.

Chapter 6, Callbacks in Asynchronous Programming, is the second part of async programming in Node. We'll look into callbacks, HTTPS requests, and error handling inside of our callback functions. We'll also look into the forecast API and fetching real-time weather data for our address.

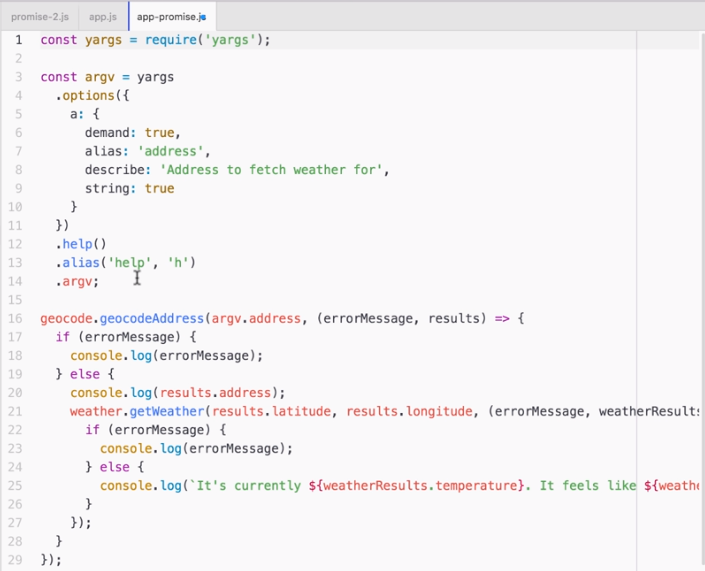

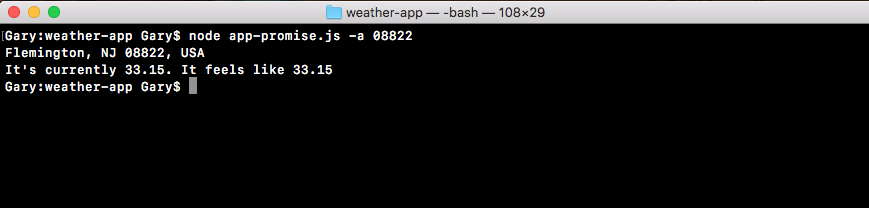

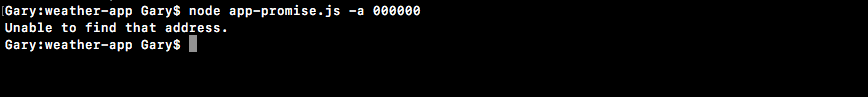

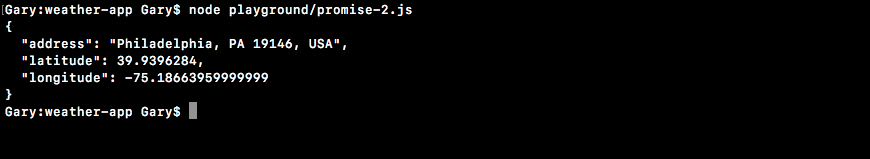

Chapter 7, Promises in Asynchronous Programming, is the third and last part of async programming in Node. This chapter focuses on Promises, how it works, why they are useful, and so on. At the end of this chapter, we'll use Promises in our weather app.

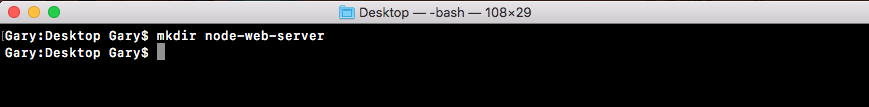

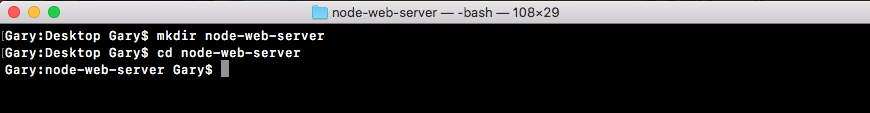

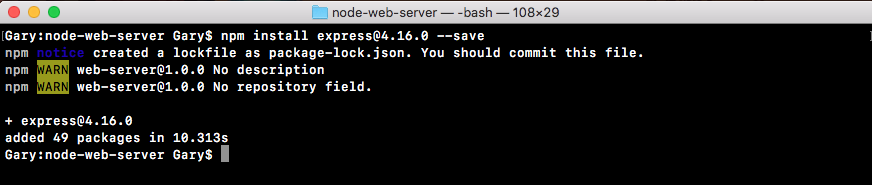

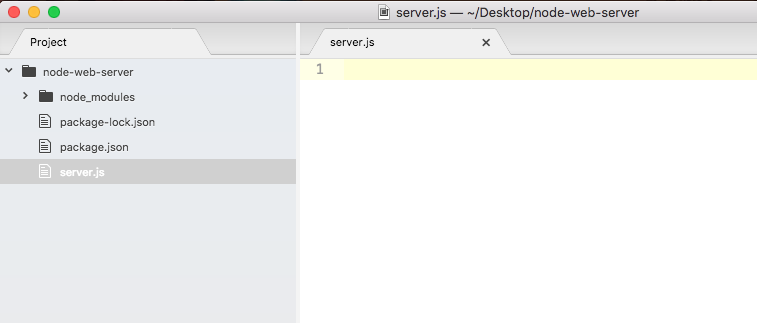

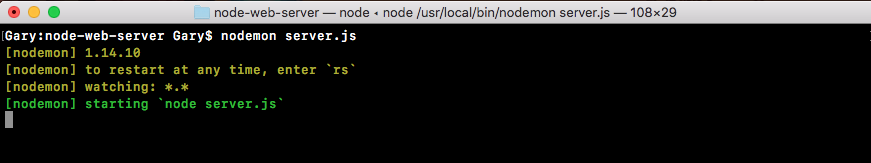

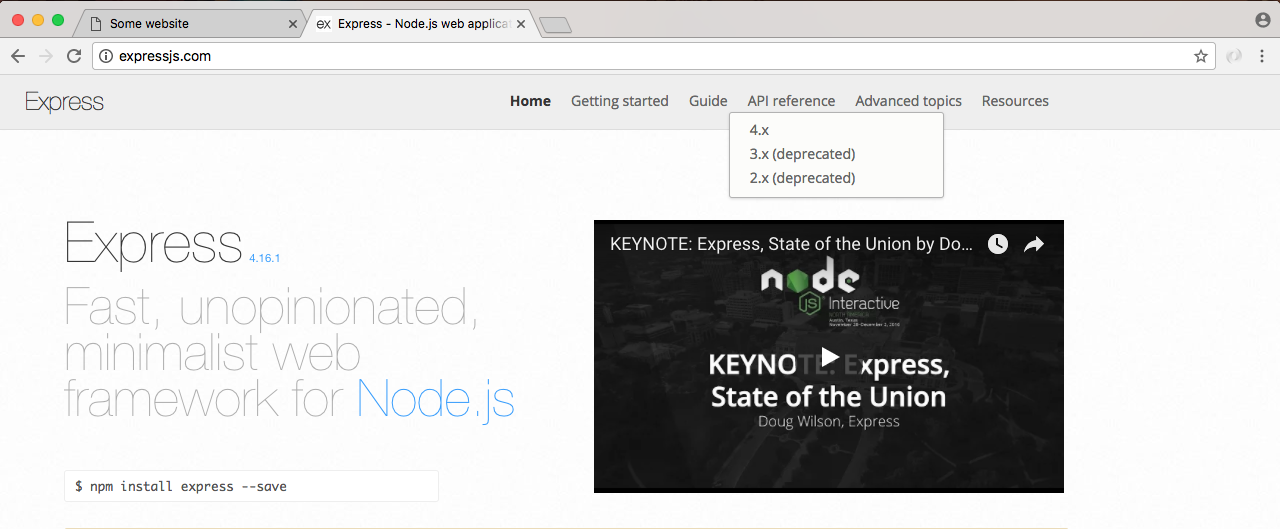

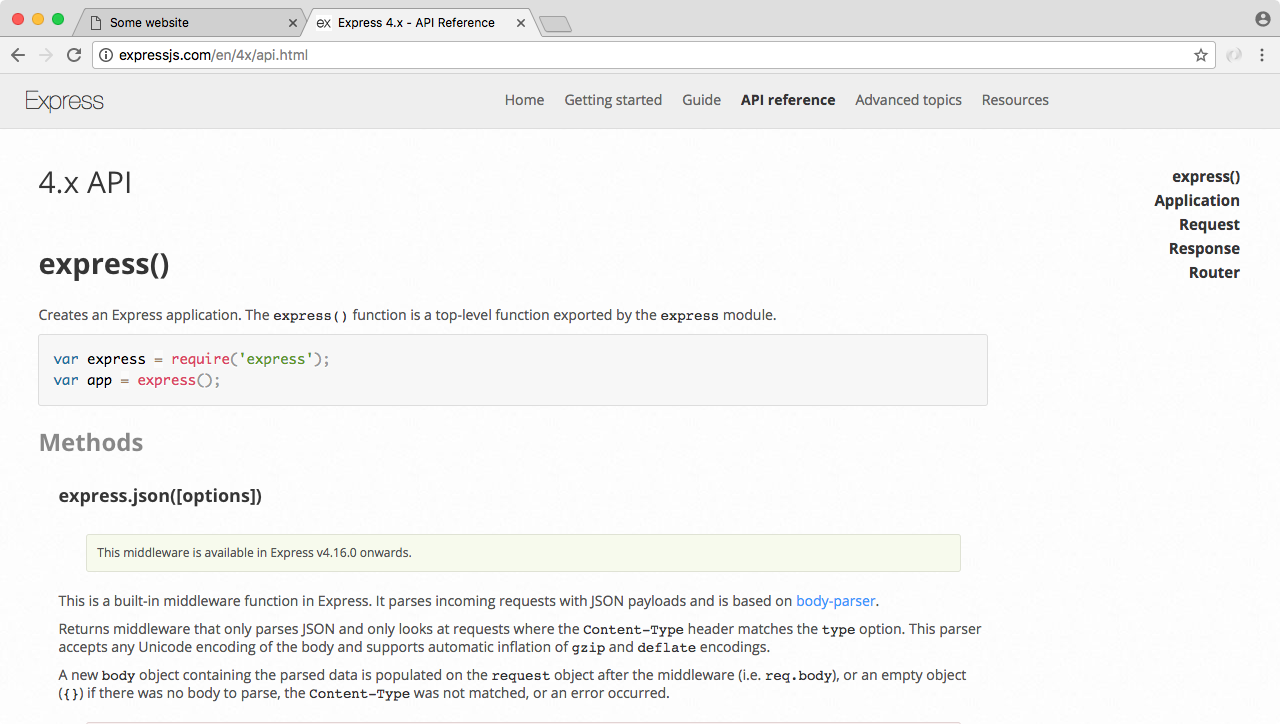

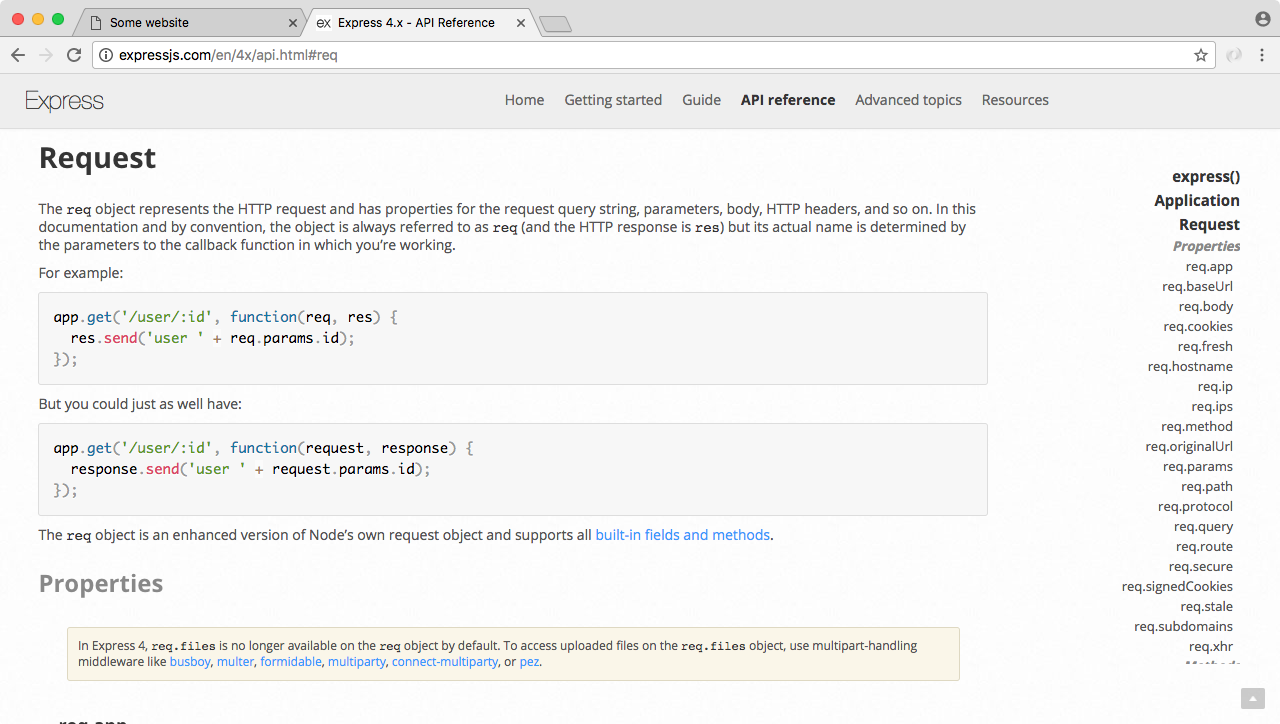

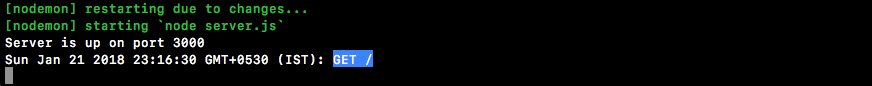

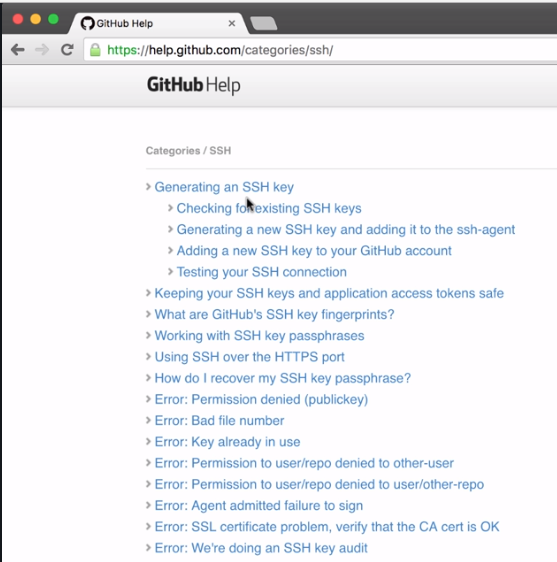

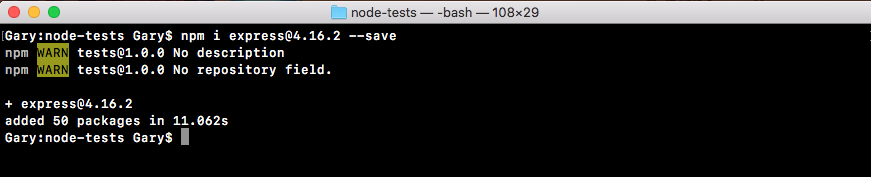

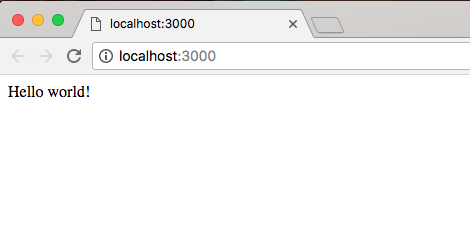

Chapter 8, Web Servers in Node, talks about Node web servers and integrating version control into Node applications. We'll also introduce a framework called Express, one of the most important NPM libraries.

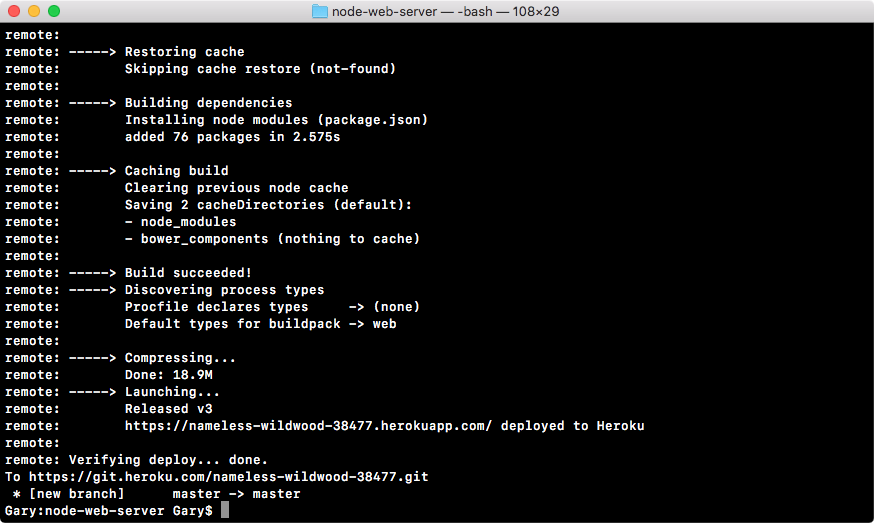

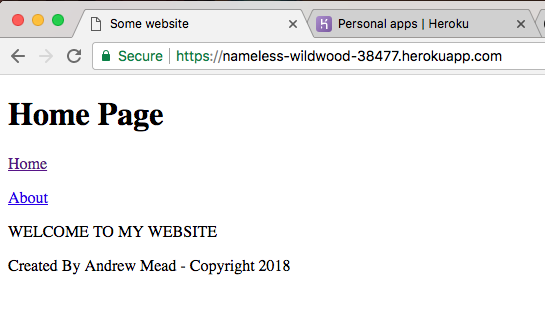

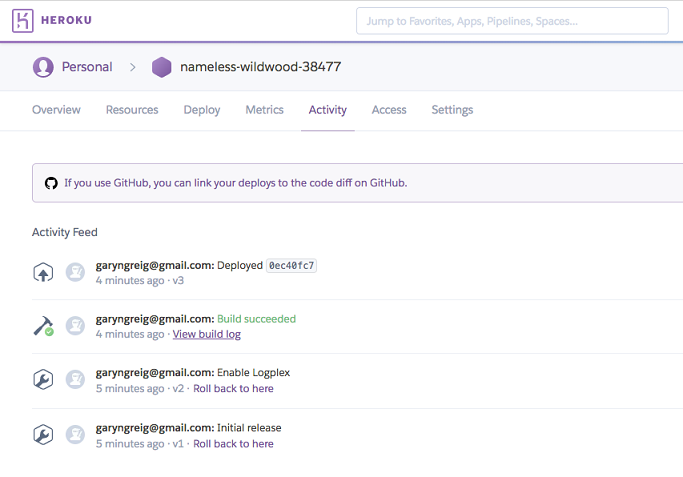

Chapter 9, Deploying Applications to Web, talks about deploying the applications to the Web. We'll be using Git, GitHub, and deploy our live app to the Web using these two services.

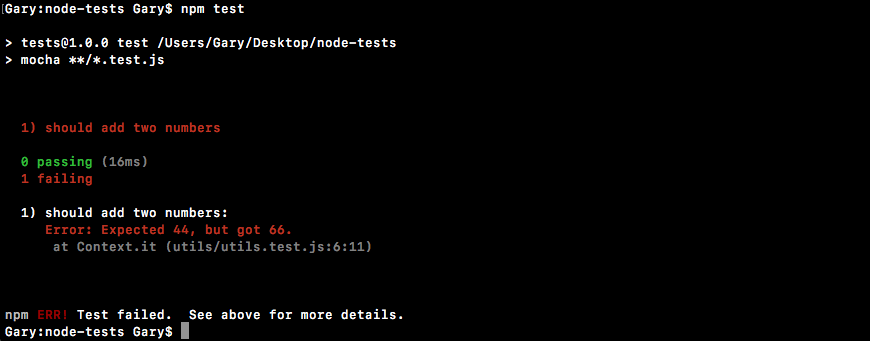

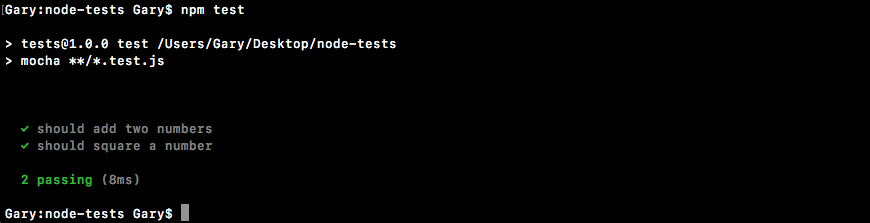

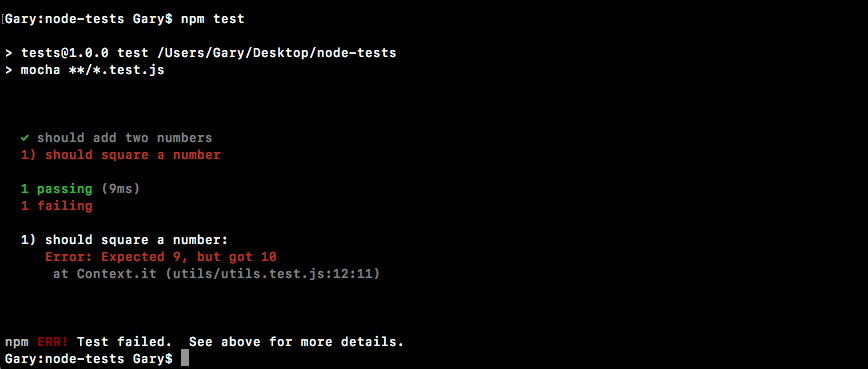

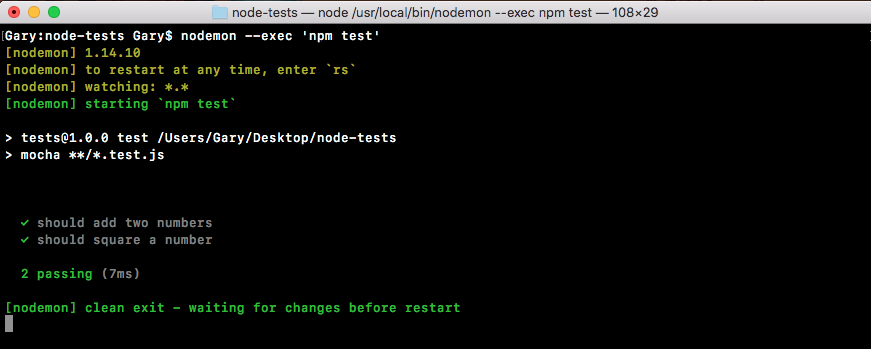

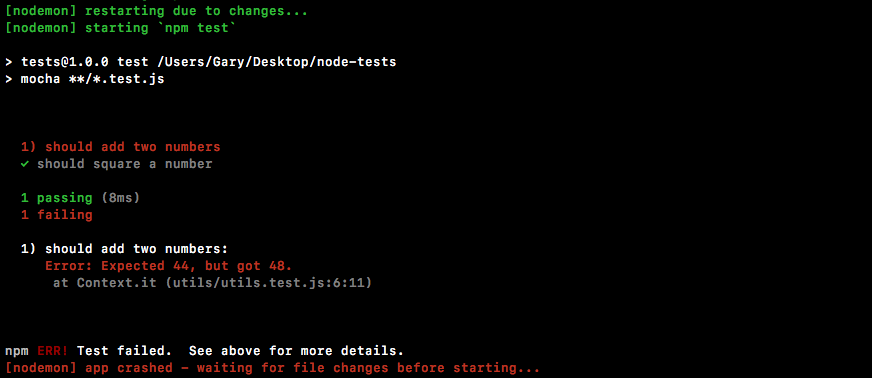

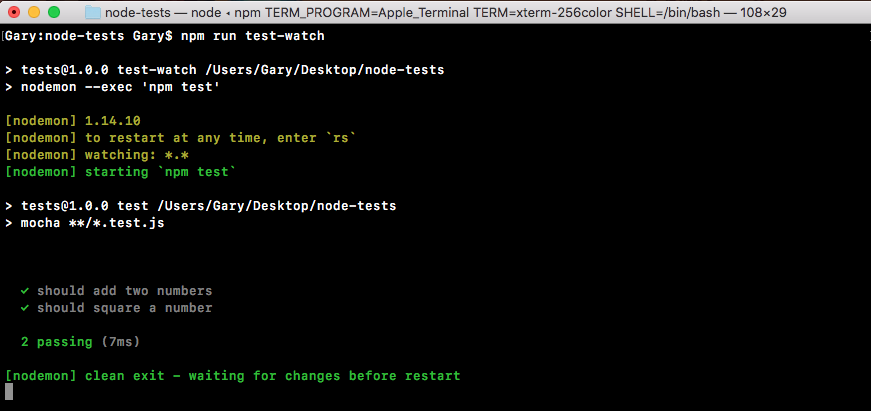

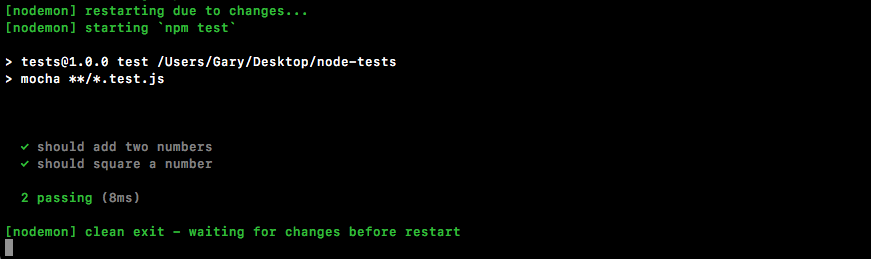

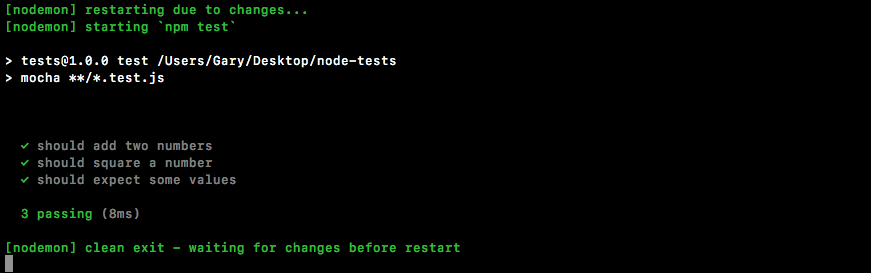

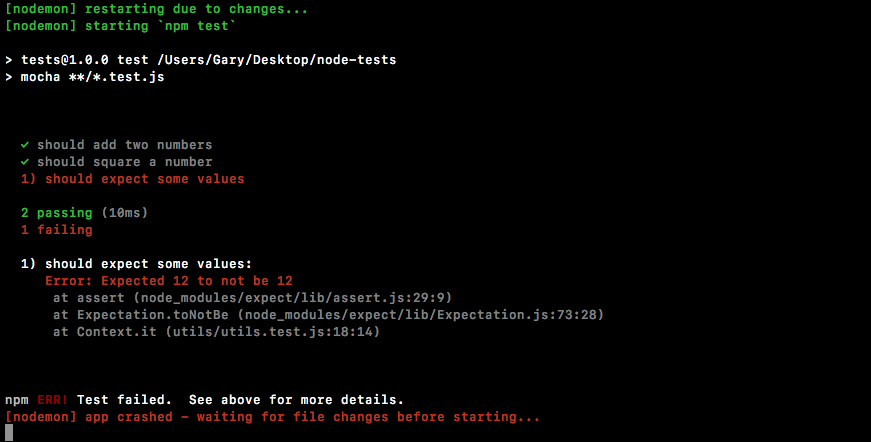

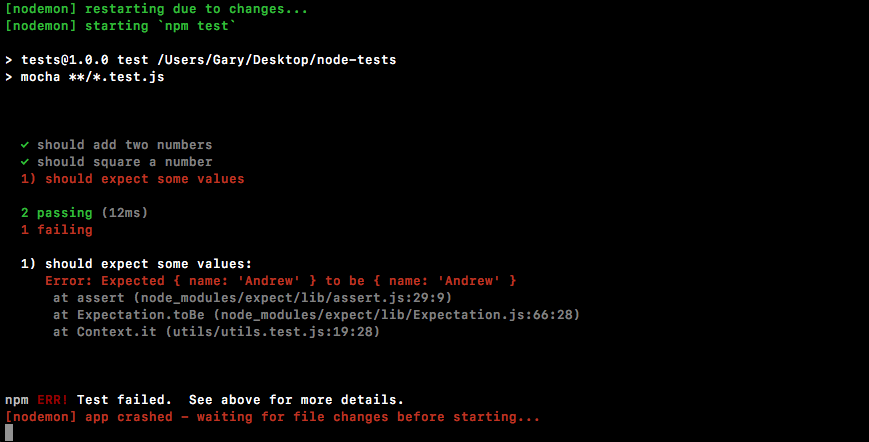

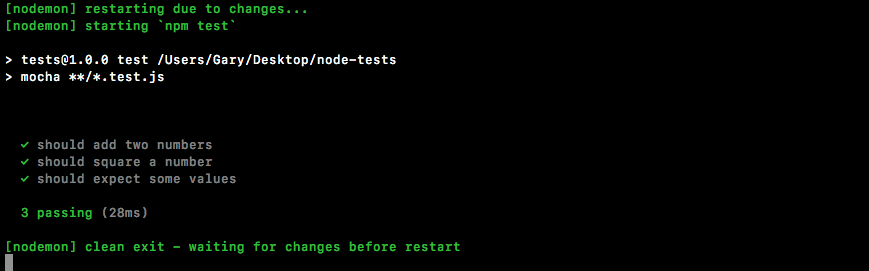

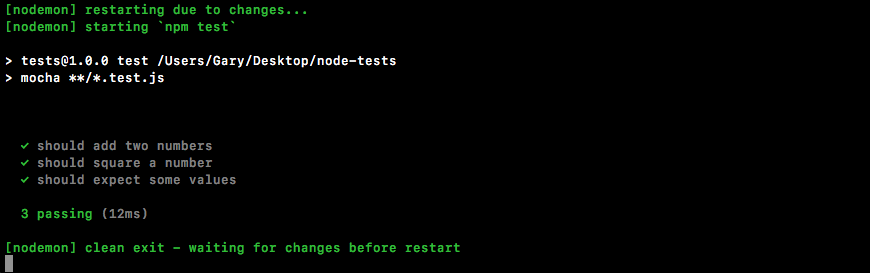

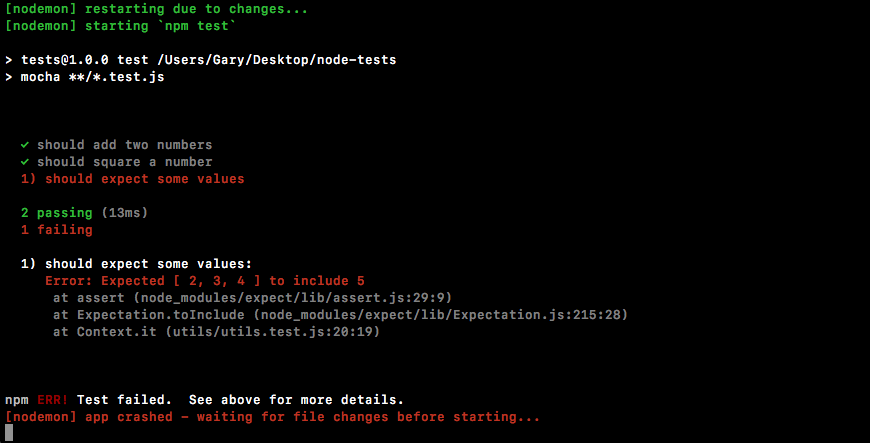

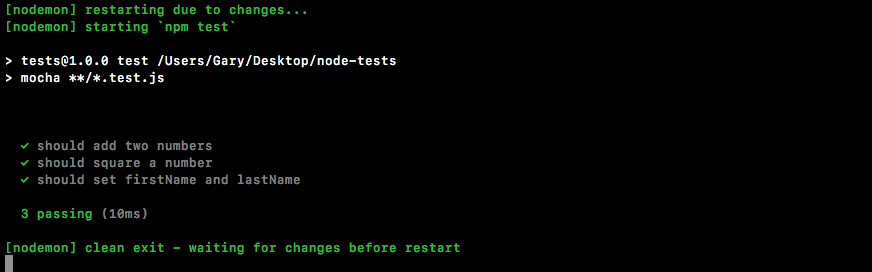

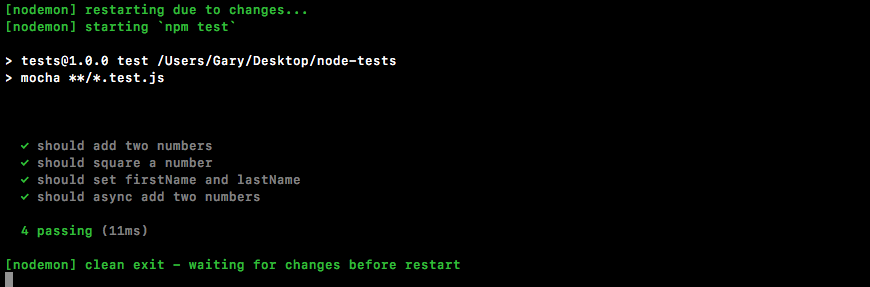

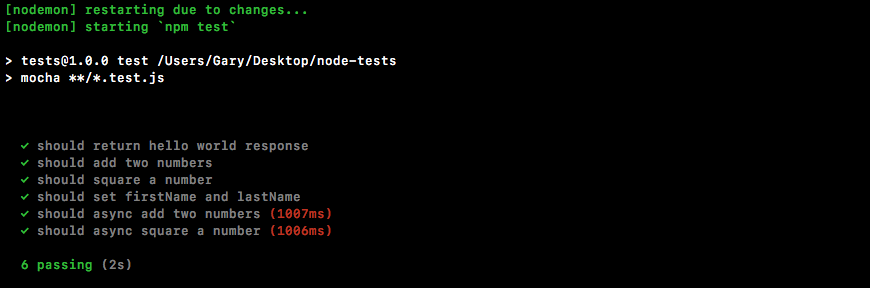

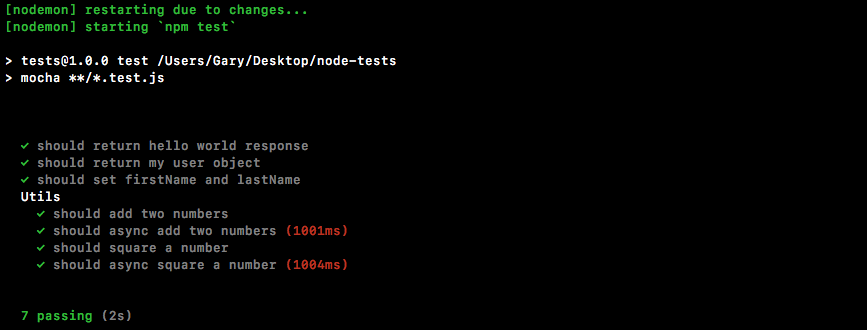

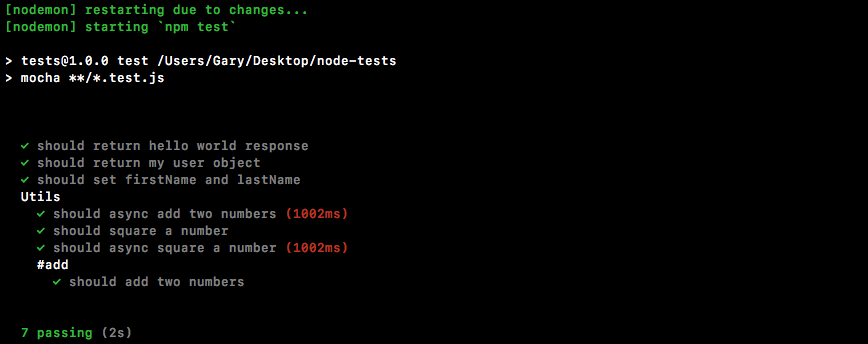

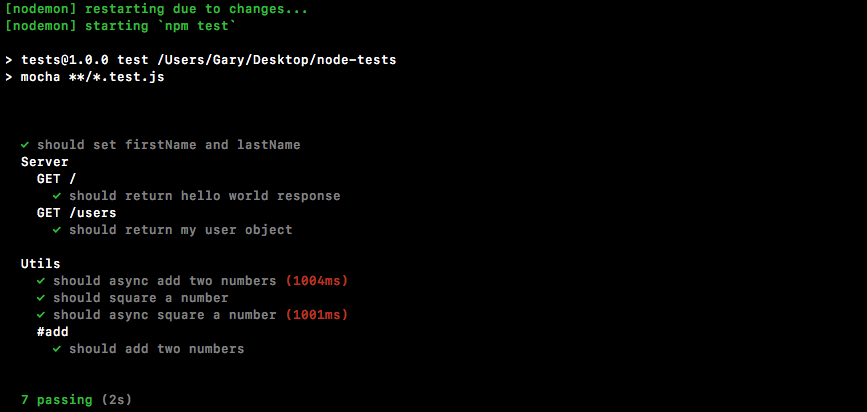

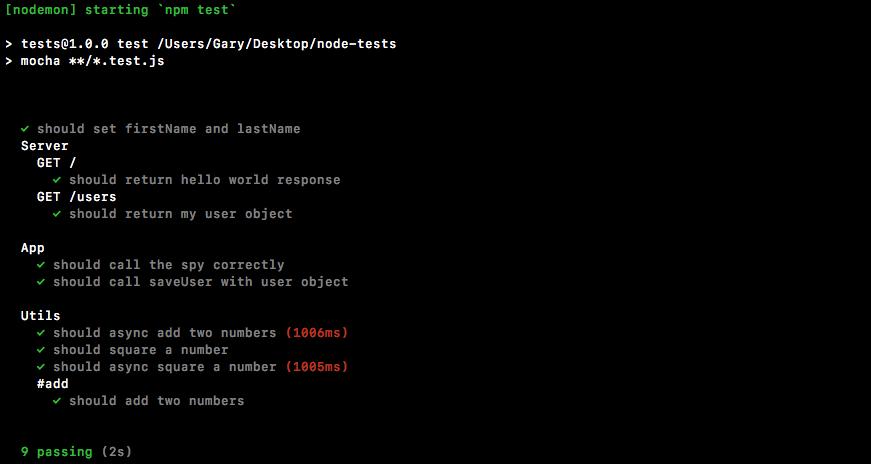

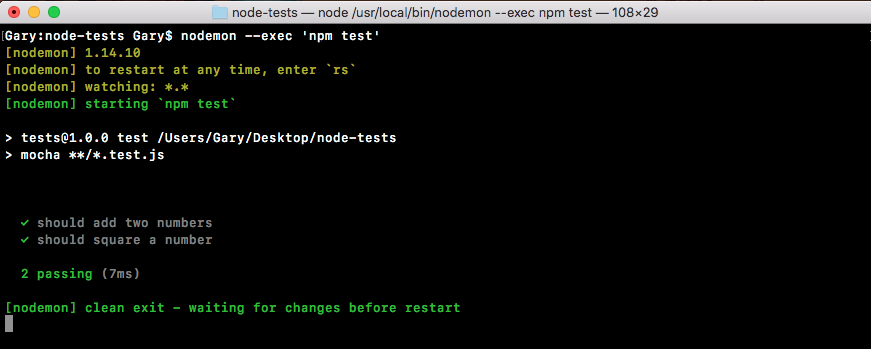

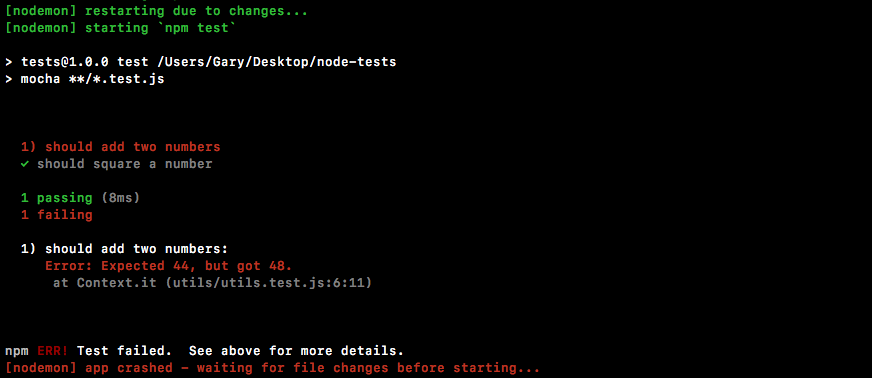

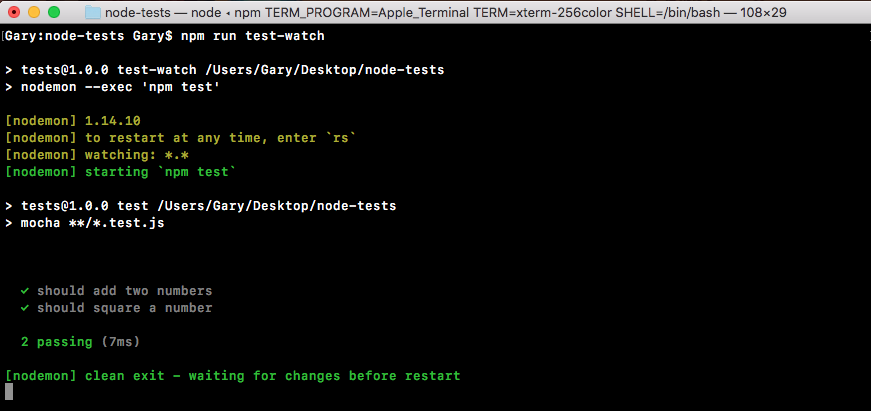

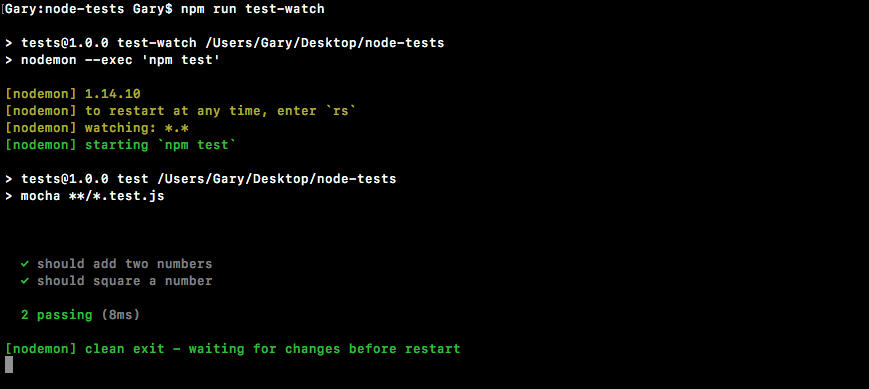

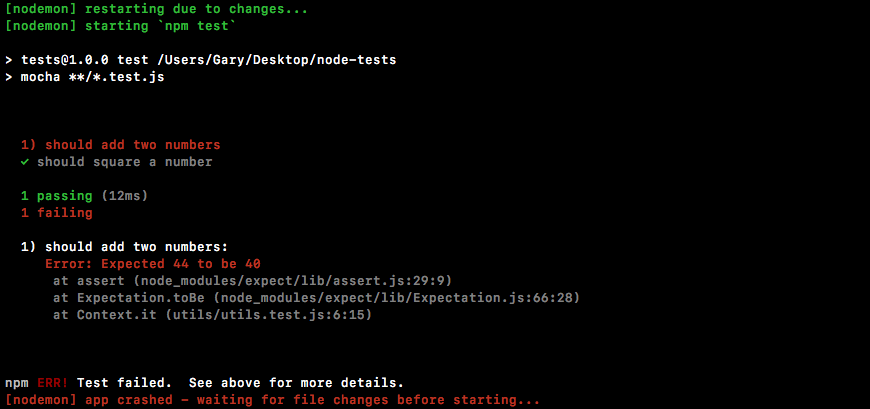

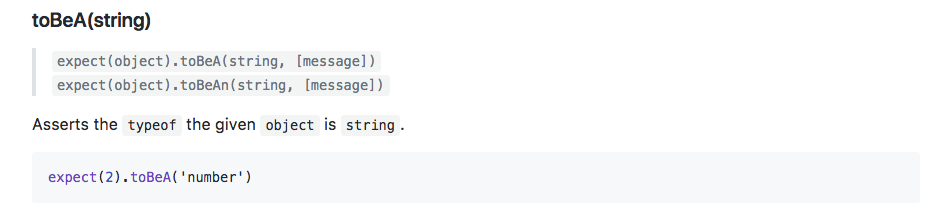

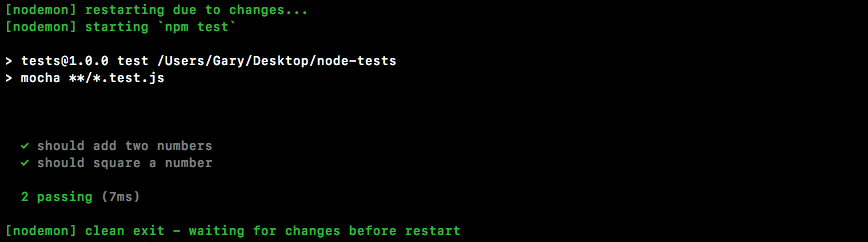

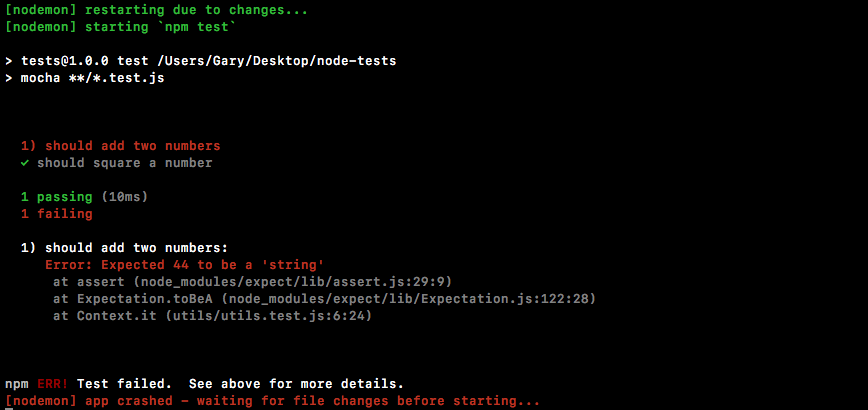

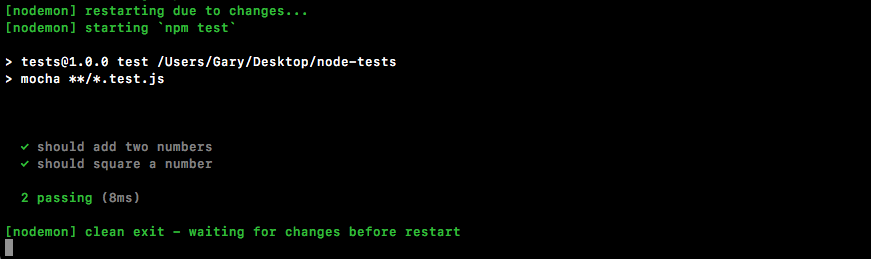

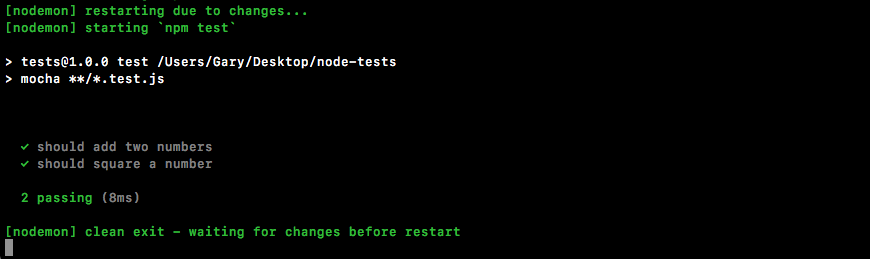

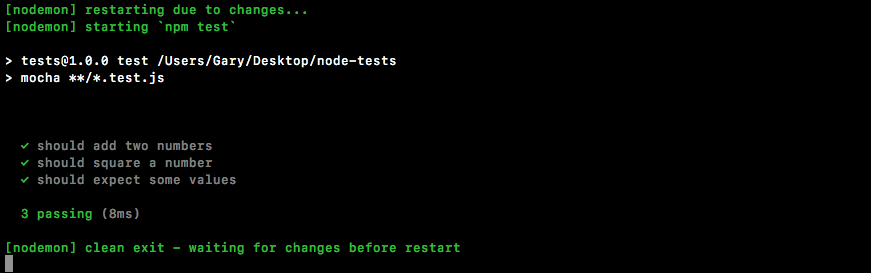

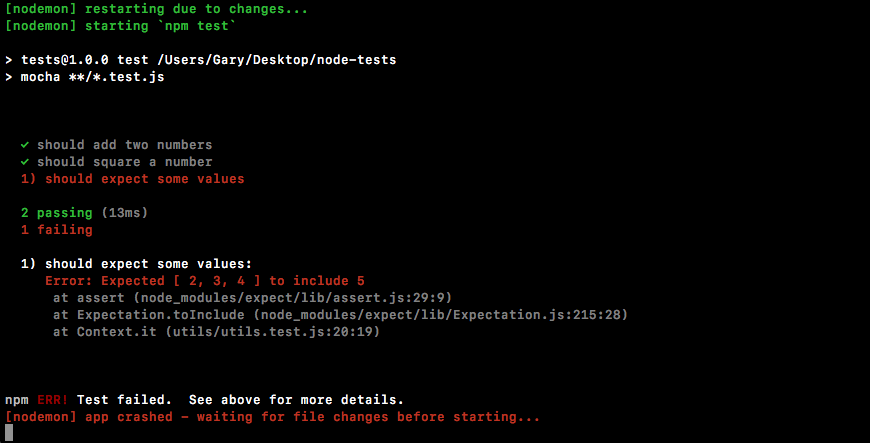

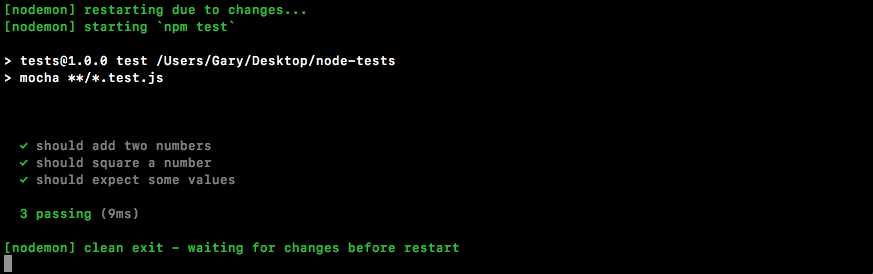

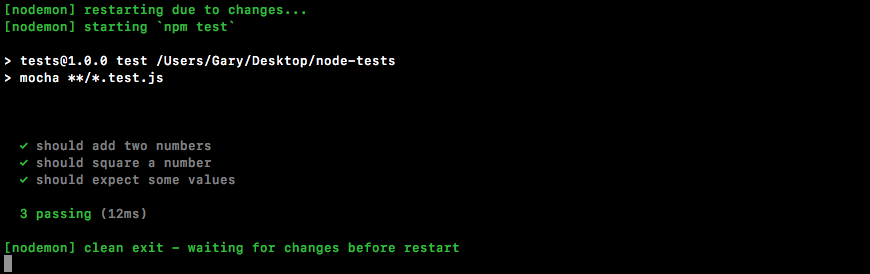

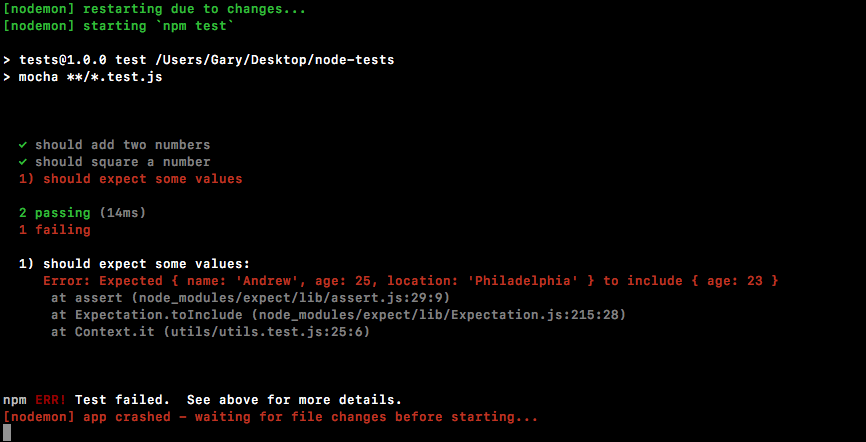

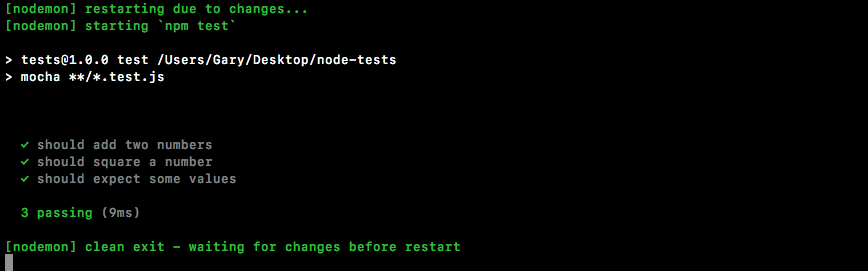

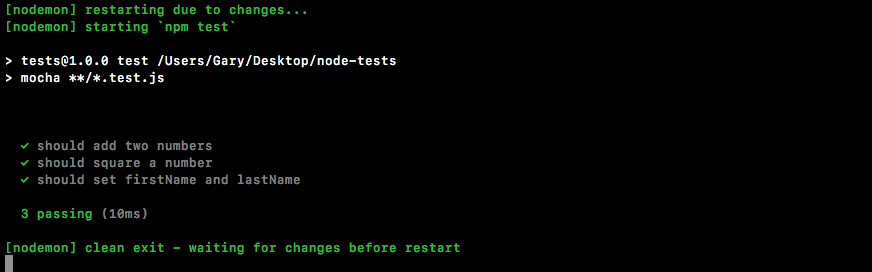

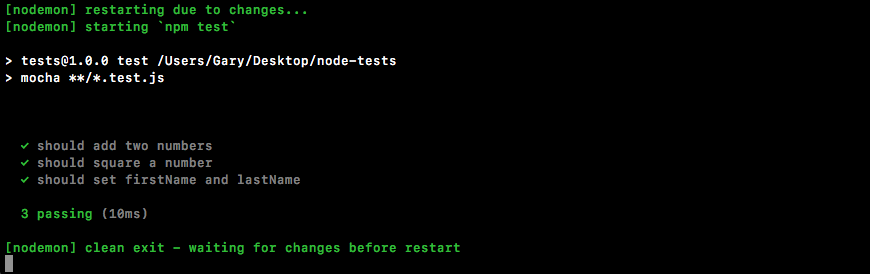

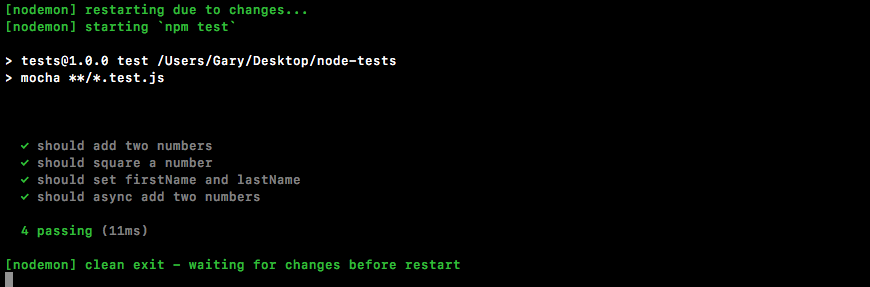

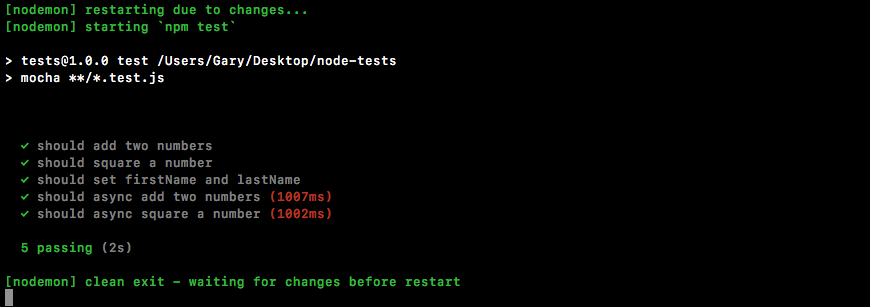

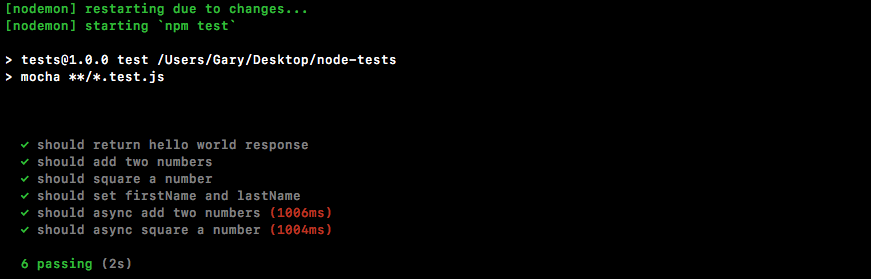

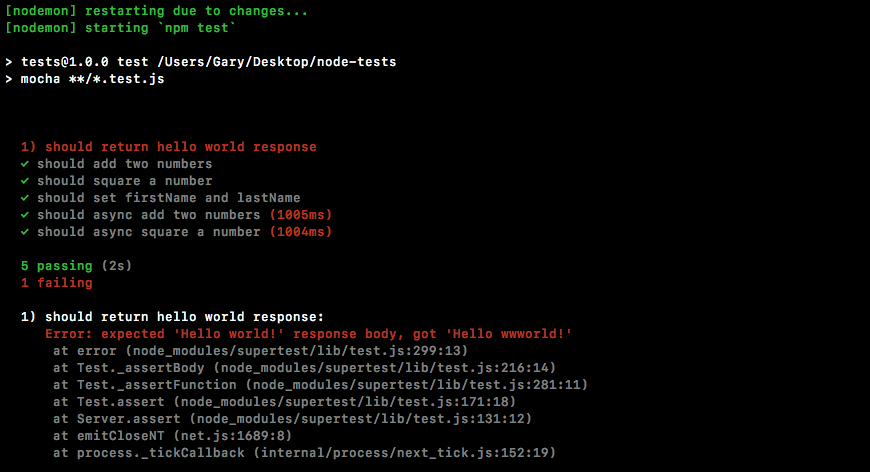

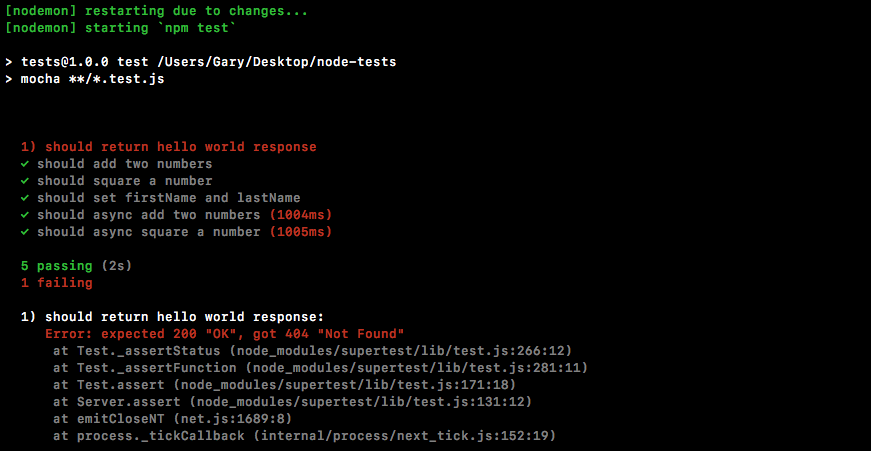

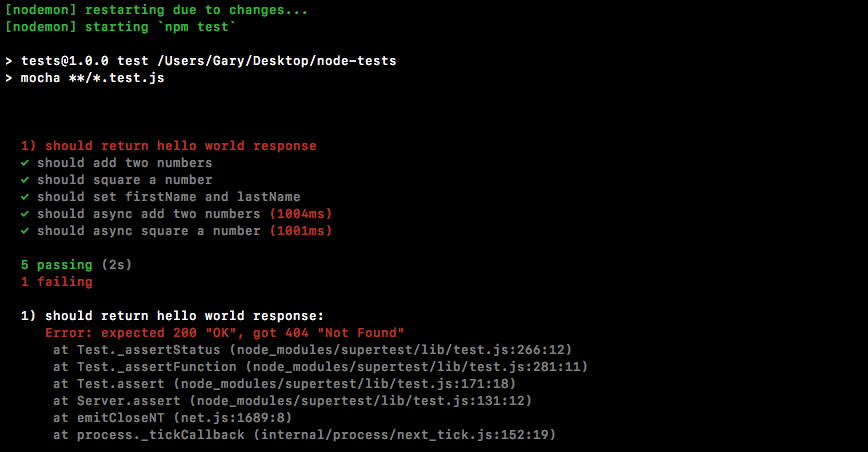

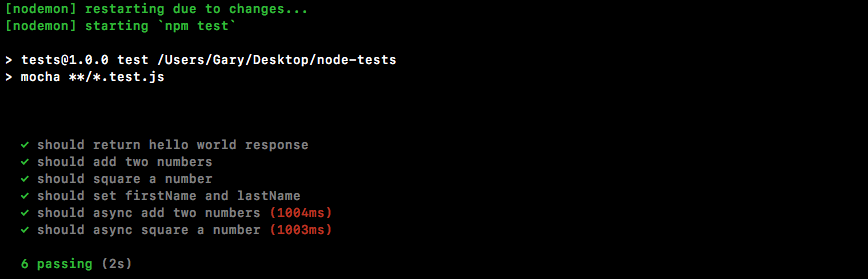

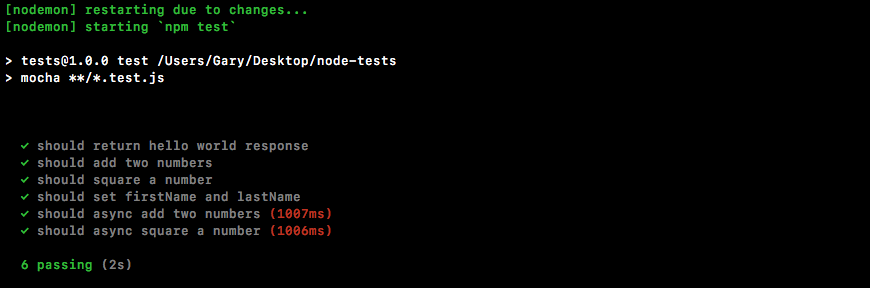

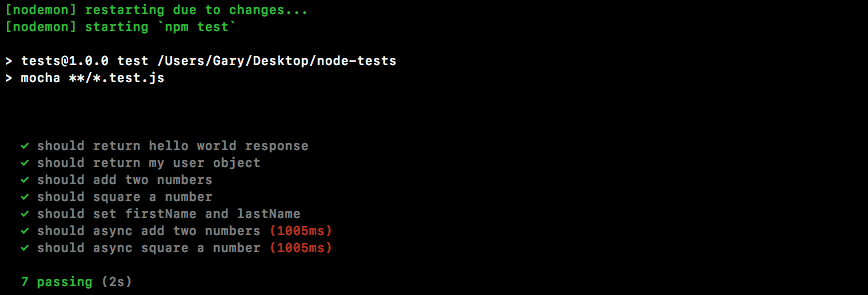

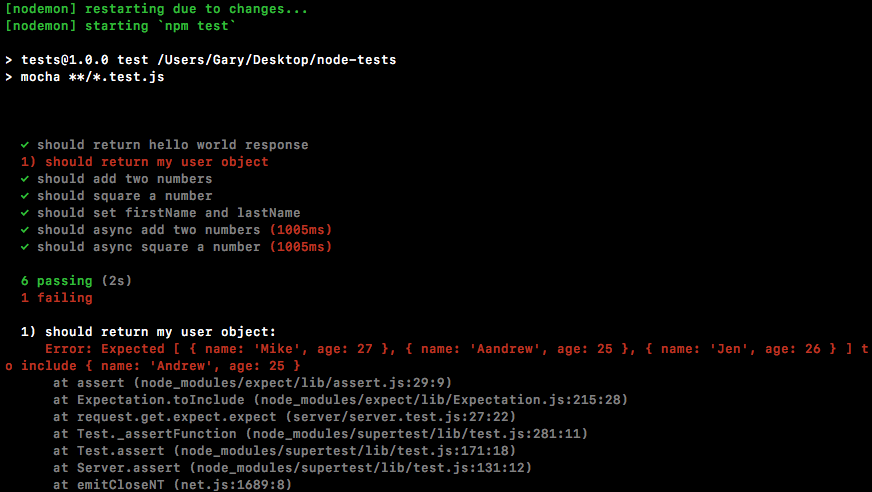

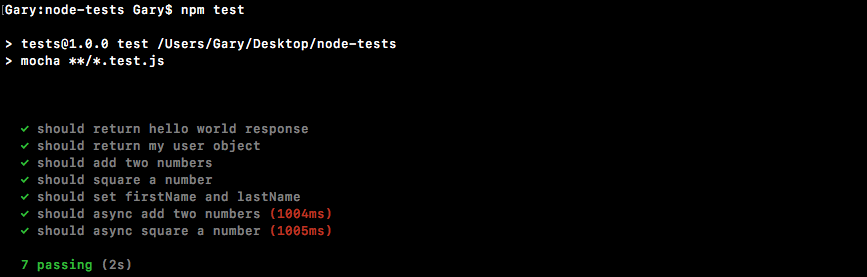

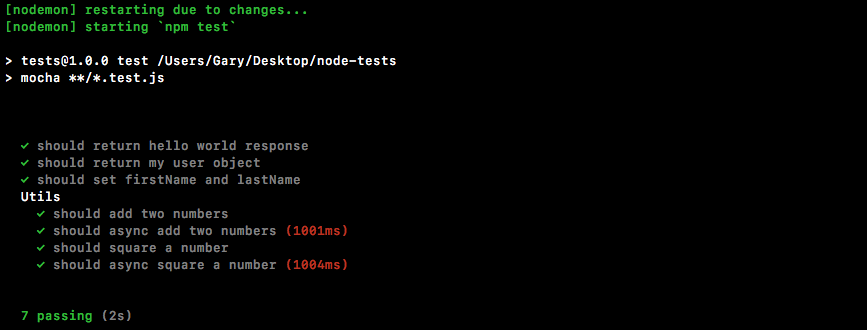

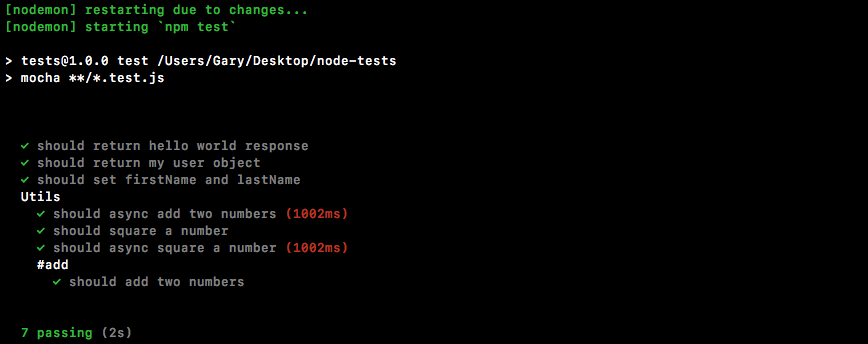

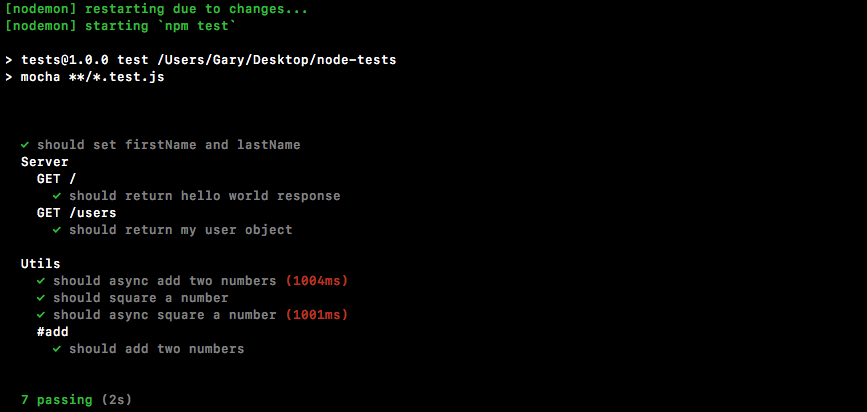

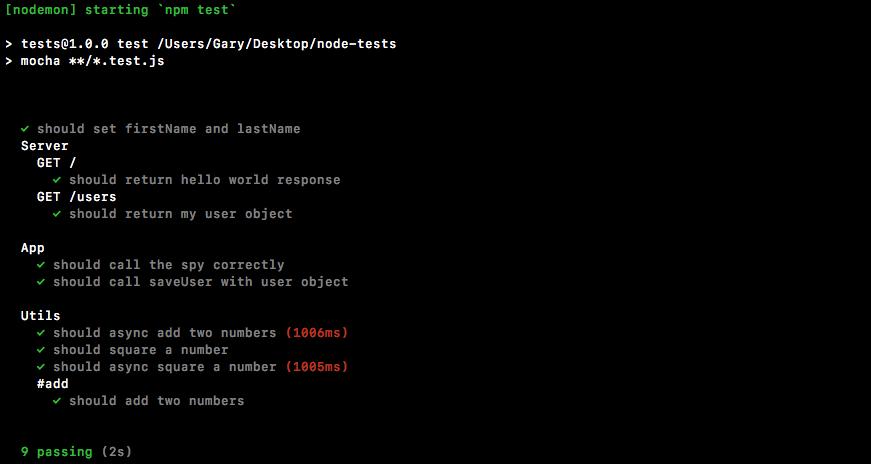

Chapter 10, Testing the Node Applications- Part 1, talks about how we can test our code to make sure it is working as expected. We'll work on setting up for testing and then writing our test cases. We'll look into the basic testing framework and asynchronous testing.

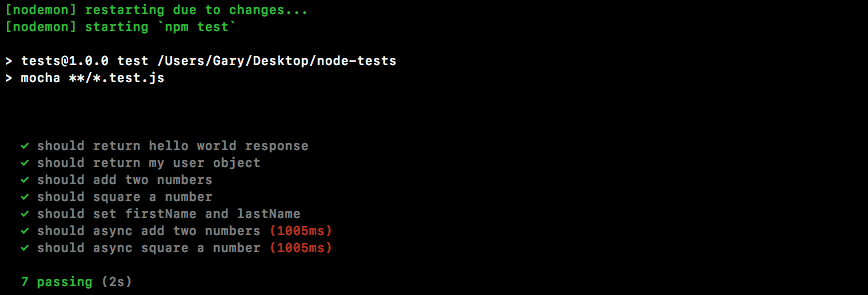

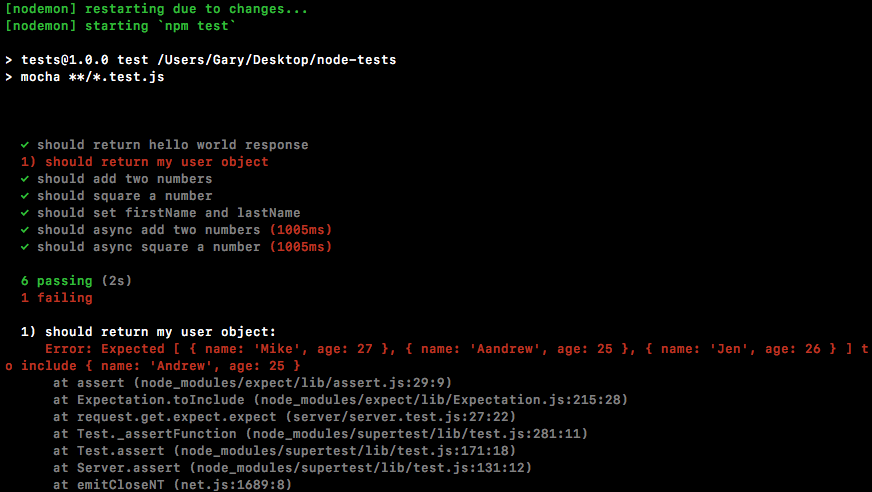

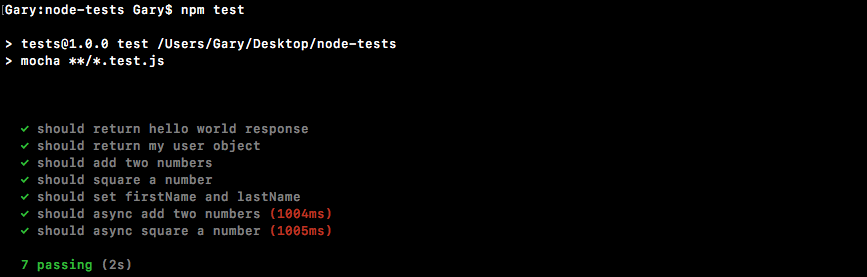

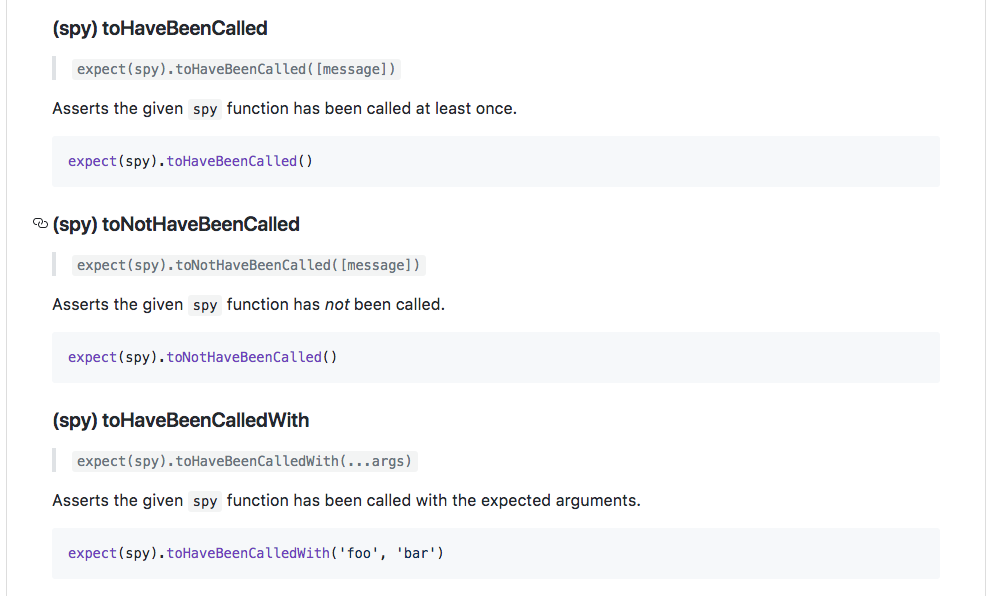

Chapter 11, Testing the Node Application - Part 2, continues our journey of testing Node applications. In this chapter, we'll work on testing the Express applications and look into some advanced methods of testing.

A web browser, we'll be using Chrome throughout the course book but any browser will do, and Terminal, sometimes known as the command line on Linux or the Command Prompt on Windows. Atom as the text editor. The following list of modules will be used throughout the course of this book:

You can download the example code files for this book from your account at www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files emailed directly to you.

You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

The code bundle for the book is also hosted on GitHub at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/Learning-Node.js-Development. We also have other code bundles from our rich catalog of books and videos available at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/. Check them out!

There are a number of text conventions used throughout this book.

CodeInText: Indicates code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles. Here is an example: "Mount the downloaded WebStorm-10*.dmg disk image file as another disk in your system."

A block of code is set as follows:

console.log('Starting app.js');

const fs = require('fs');

const _ = require('lodash');

const yargs = require('yargs');

When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

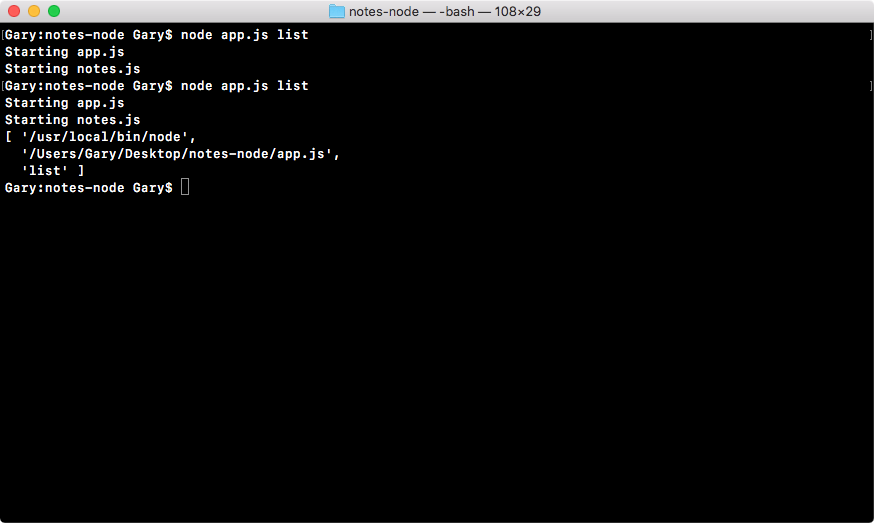

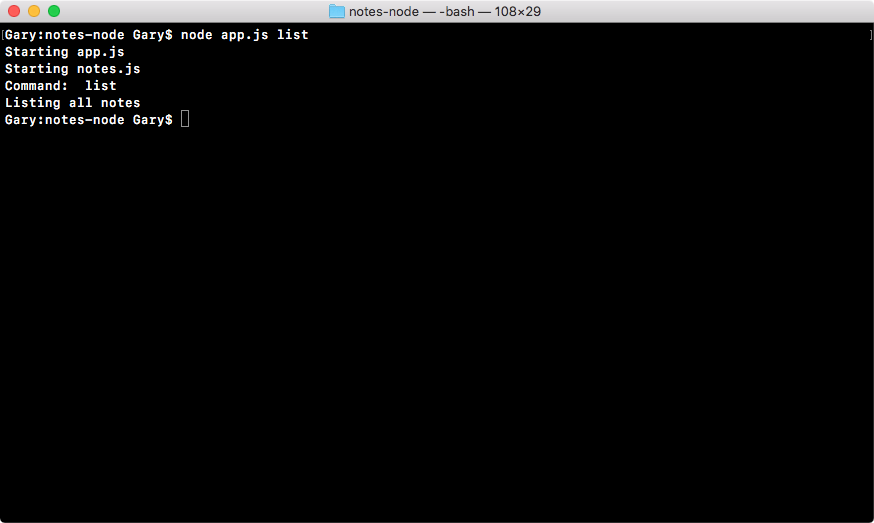

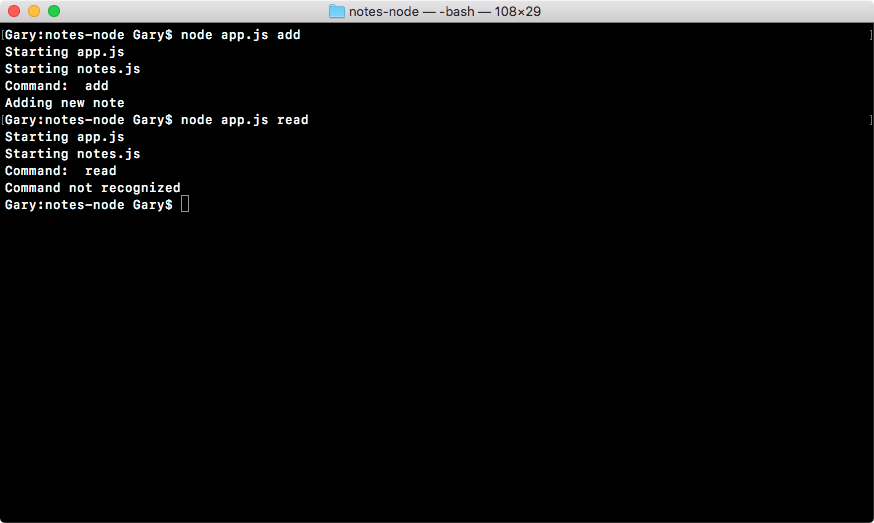

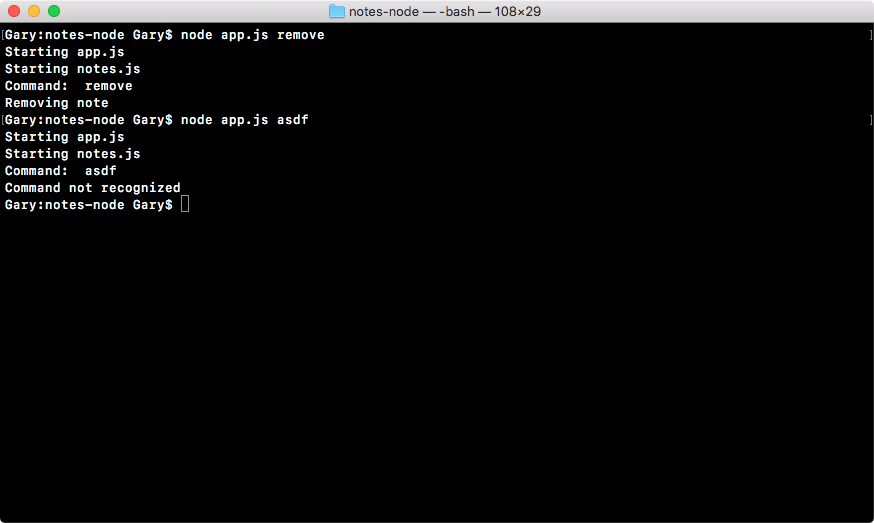

const argv = yargs.argv;

var command = process.argv[2];

console.log('Command:', command);

console.log('Process', process.argv);

console.log('Yargs', argv);

Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

cd hello-world

node app.js

Bold: Indicates a new term, an important word, or words that you see onscreen. For example, words in menus or dialog boxes appear in the text like this. Here is an example: "Select System info from the Administration panel."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome.

General feedback: Email feedback@packtpub.com and mention the book title in the subject of your message. If you have questions about any aspect of this book, please email us at questions@packtpub.com.

Errata: Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you have found a mistake in this book, we would be grateful if you would report this to us. Please visit www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details.

Piracy: If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, we would be grateful if you would provide us with the location address or website name. Please contact us at copyright@packtpub.com with a link to the material.

If you are interested in becoming an author: If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, please visit authors.packtpub.com.

Please leave a review. Once you have read and used this book, why not leave a review on the site that you purchased it from? Potential readers can then see and use your unbiased opinion to make purchase decisions, we at Packt can understand what you think about our products, and our authors can see your feedback on their book. Thank you!

For more information about Packt, please visit packtpub.com.

In this chapter, you'll get your local environment set up for the rest of the book. Whether you're on macOS, Linux, or Windows, we'll install Node and look at exactly how we can run Node applications.

We'll talk about what Node is, why you would ever want to use it, and why you would want to use Node as opposed to something like Rails, C++, Java, or any other language that can accomplish similar tasks. By the end of this chapter, you will be running your very first Node application. It's going to be simple, but it is going to get us to the path to creating real-world production Node apps, which is the goal of this book.

More specifically, we'll cover the following topics:

Before we start talking about what Node is and why it's useful, you need to first install Node on your machine, because in the next couple of sections, we'll want to run a little bit of Node code.

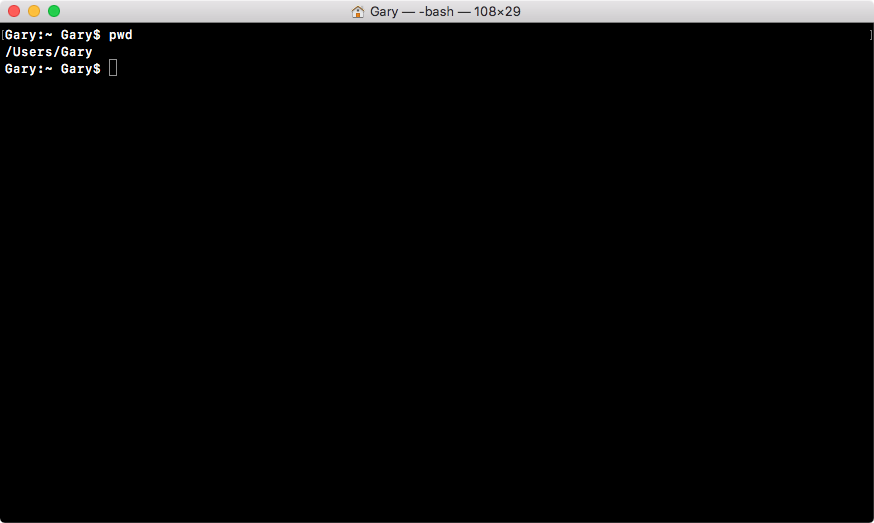

Now, to get started, we just need two programs—a browser, I'll be using Chrome throughout the book, but any browser will do, and Terminal. I'll use Spotlight to open up Terminal, which is what it's known as on my operating system.

If you're on Windows, look for the Command Prompt, you can search using the Windows key and then by typing command prompt, and on Linux, you're looking for the command line, although depending on your distribution it might be called Terminal or Command Prompt.

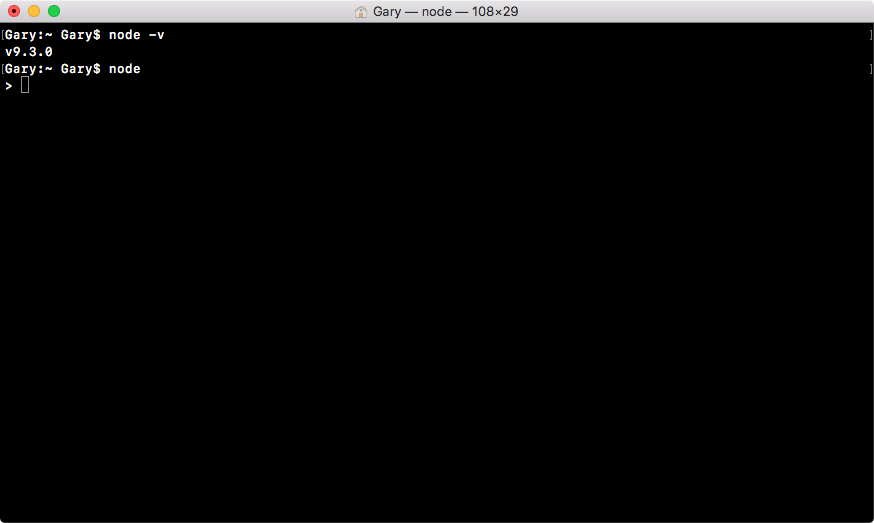

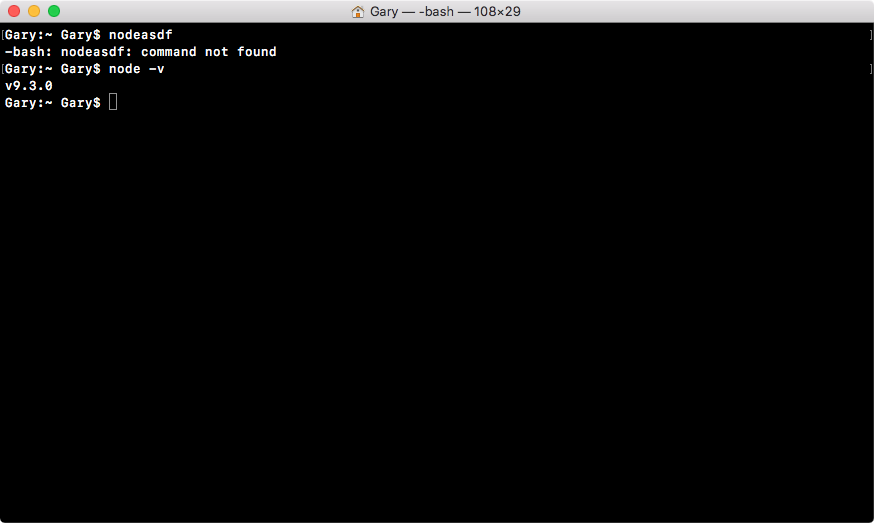

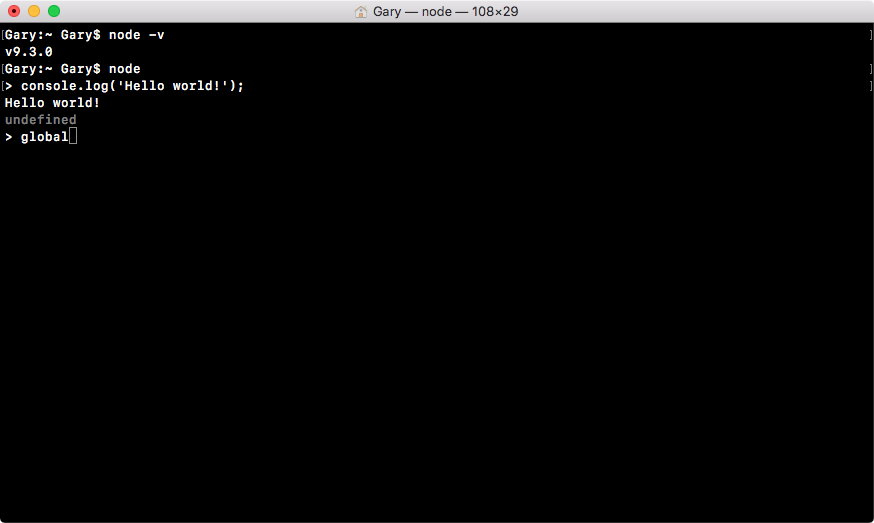

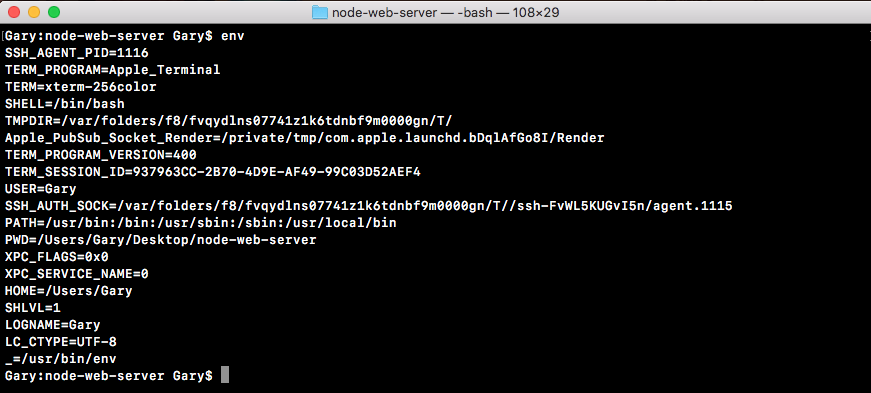

Now, once you have that program open, you'll see a screen, as shown in the following screenshot:

Essentially, it's waiting for you to run a command. We'll run quite a few commands from Terminal throughout the book. I'll discuss it in a few sections later, so if you've never used this before, you can start navigating comfortably.

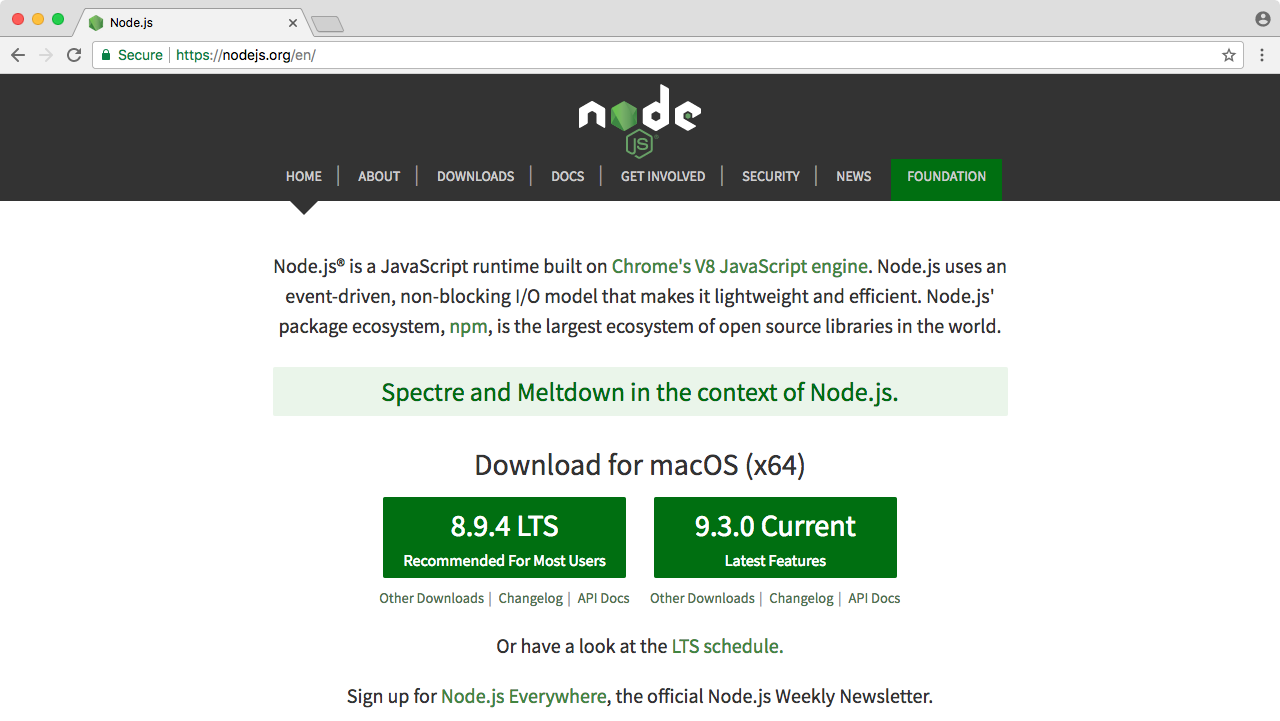

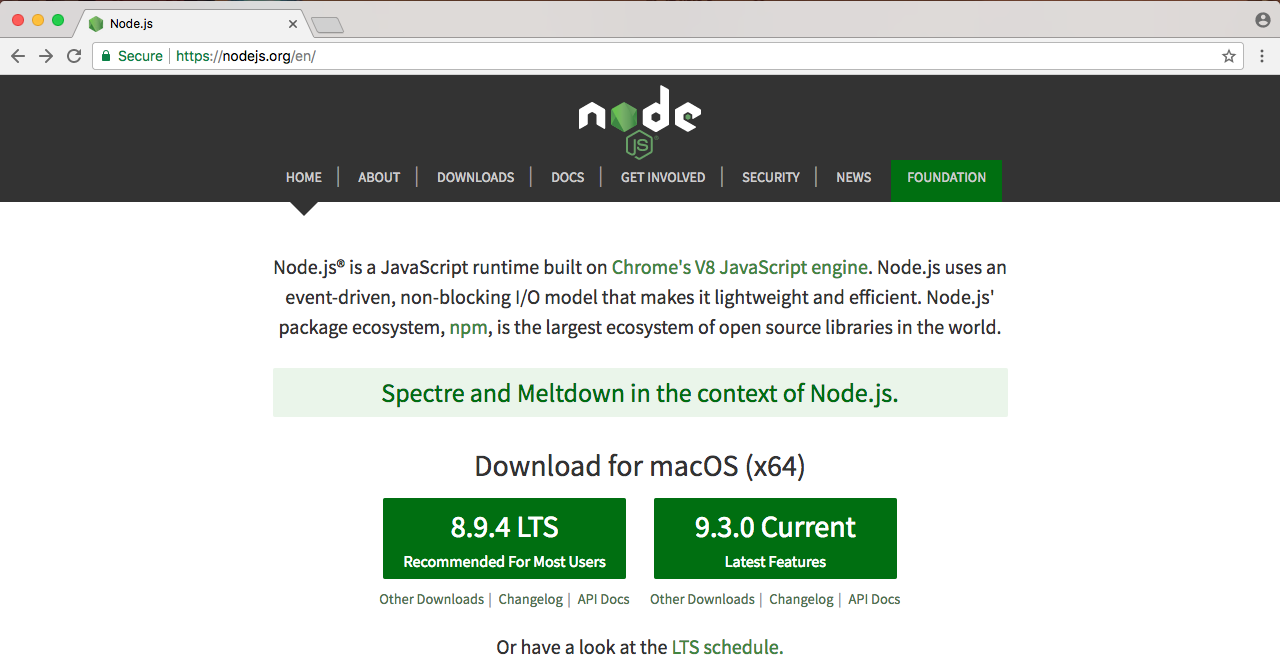

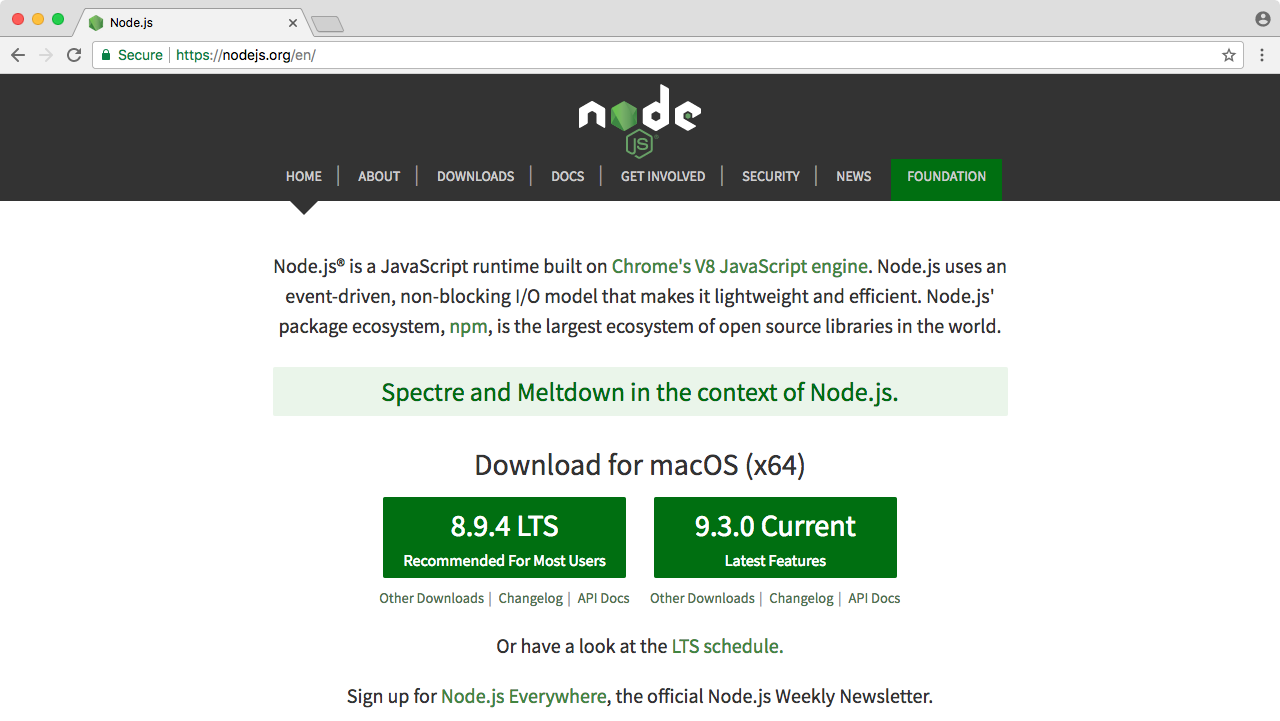

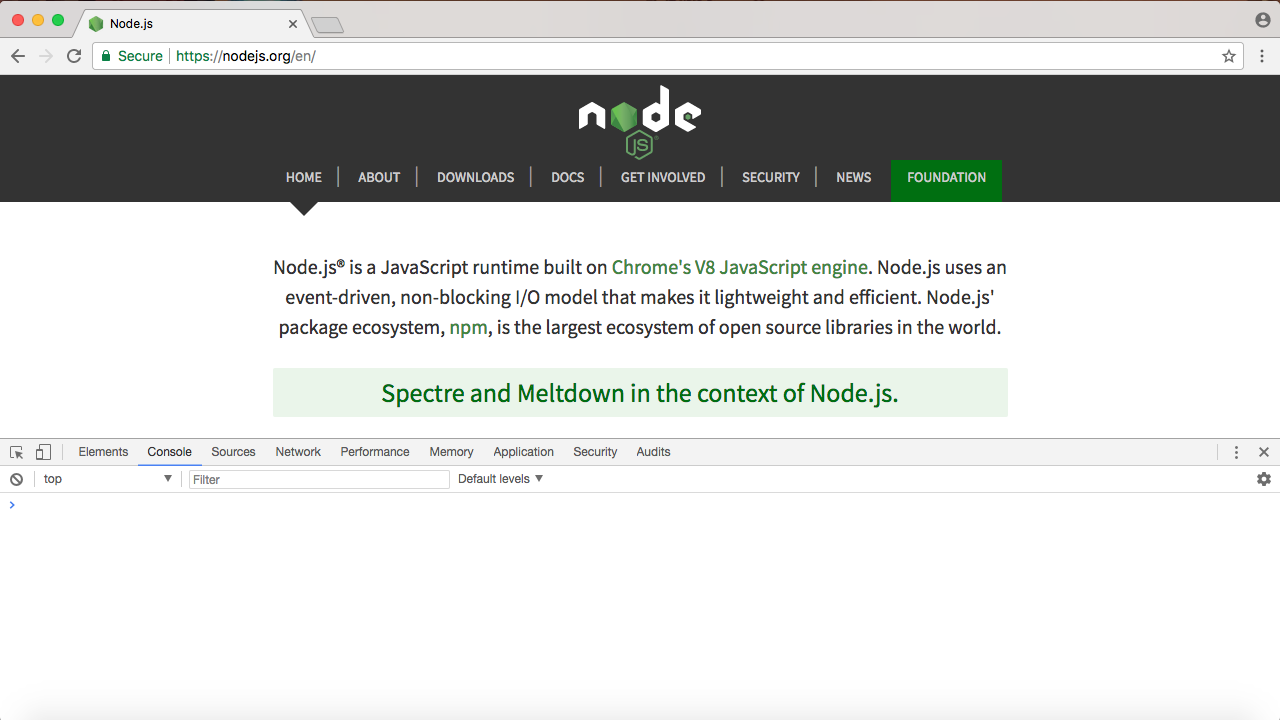

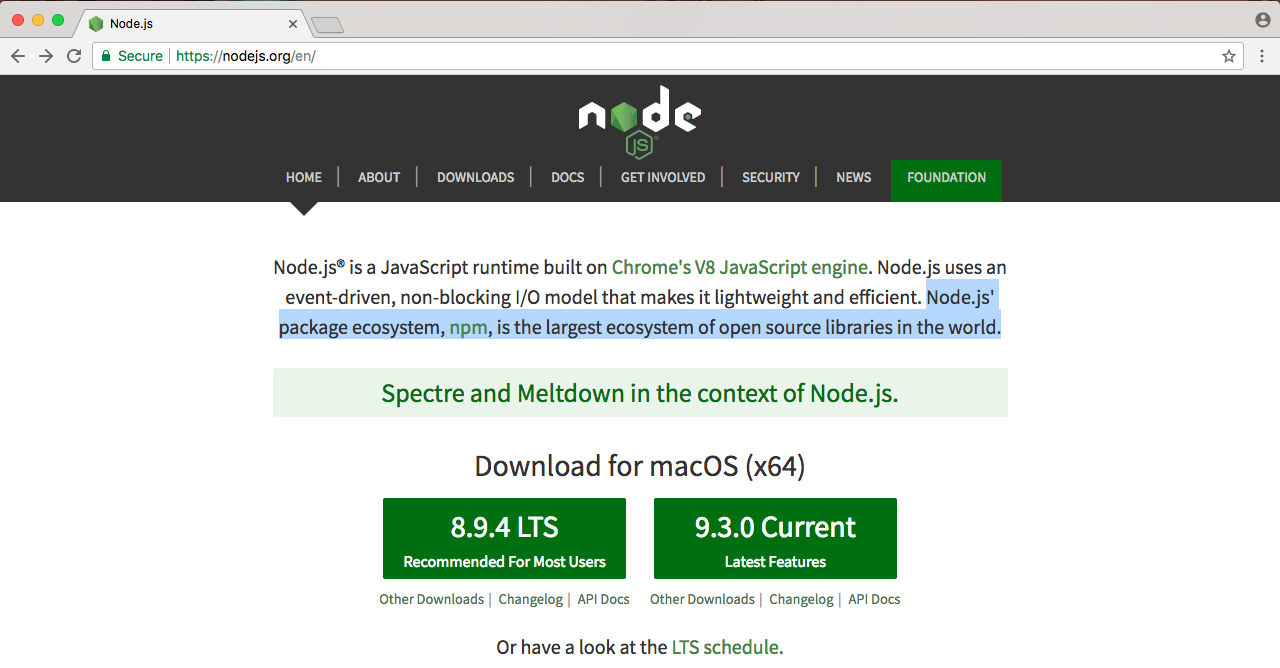

In the browser, we can head over to nodejs.org to grab the installer for the latest version of Node(as shown here). In this book, we'll use the most recent version, version 9.3.0:

ES6 is the next version of JavaScript and it comes with a lot of great enhancements we'll be using throughout the book. If you look at the following image, Node.js Long Term Support Release Schedule (https://github.com/nodejs/LTS), you can see that the current Node version is V8, out in April 2017:

Before going further, I would like to talk about the Node release cycle. What I have in the preceding image is the official release cycle, this is released by Node. You'll notice that only next to the even Node numbers do you find the active LTS, the blue bar, and the maintenance bar. Now, LTS stands for long-term support, and this is the version that's recommended for most users. I'd recommend that you stick with the currently offered LTS option (Node v 8.9.4 LTS), though anything on the left-hand side will do, this is shown as the two green buttons on nodejs.org.

Now, as you can see, the major version numbers, bump every six months. Regardless of any sort of big overarching change, this happens like clockwork even if nothing drastic has changed. It's not like Angular where jumping from 1.0 to 2.0 was almost like using a completely different library. This is just not the case with Node, what you're getting from this book is the latest and greatest Node has to offer.

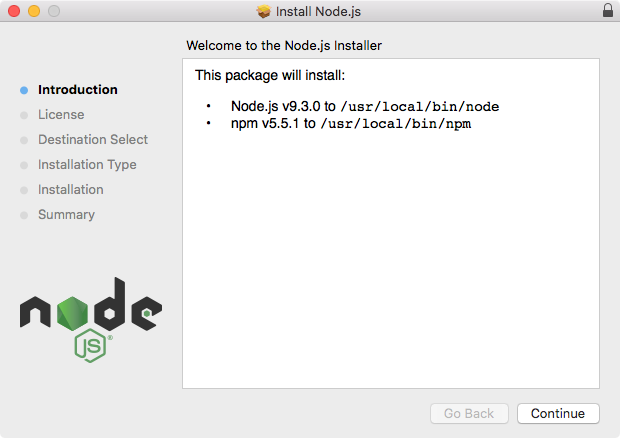

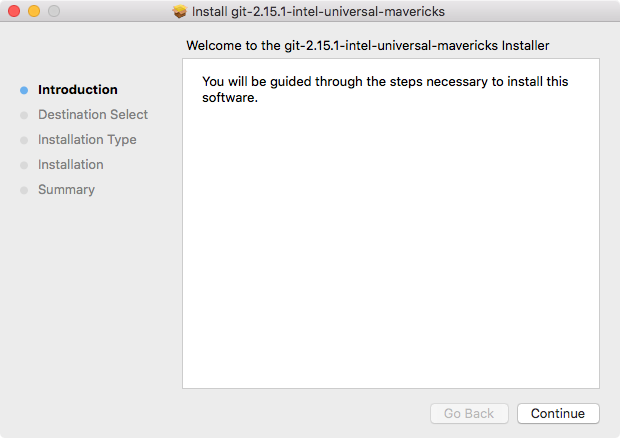

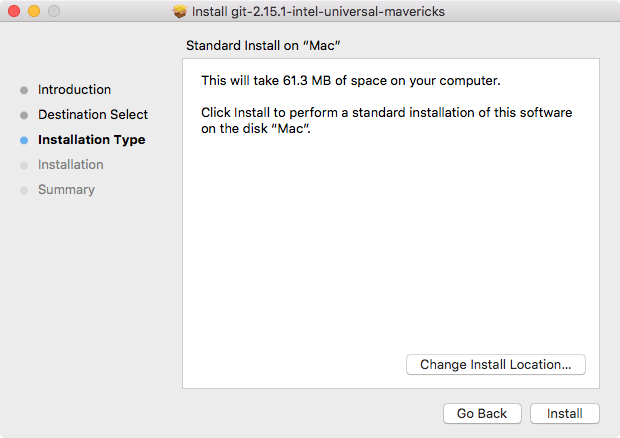

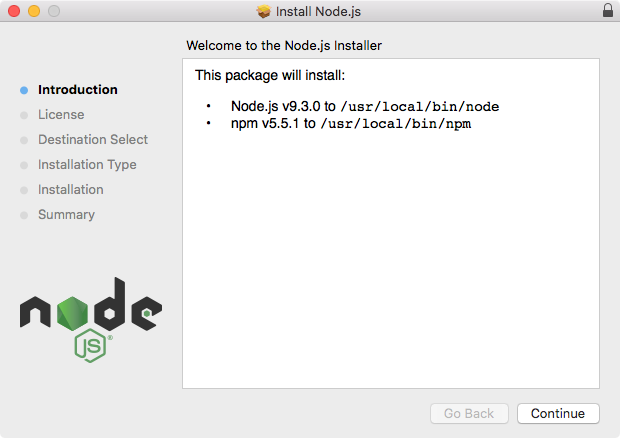

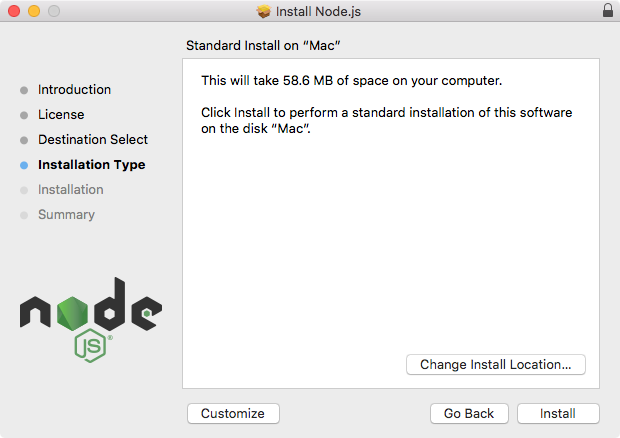

Once the version is confirmed and selected, all we have to do is to click the required version button on the Node website (nodejs.org) and download the installer. The installer is one of those basic click Next a few times and you're done type of installers, there's no need to run any fancy commands. I'll start the installer. As shown in the following screenshot, it'll just ask a few questions, then let's click on Next or Continue through all of them:

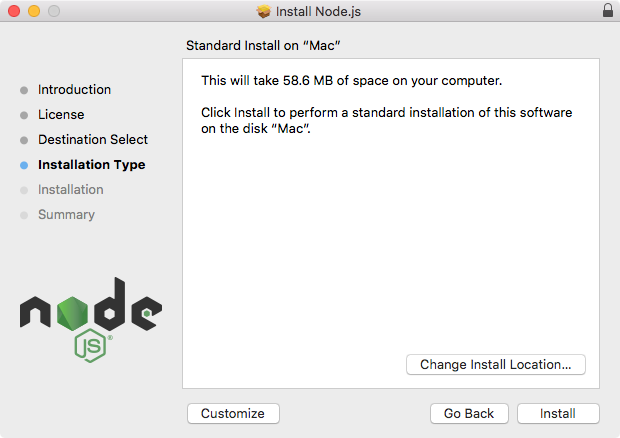

You might want to specify a custom destination, but if you don't know what that means, and you don't usually do it when installing programs, skip that step too. Here, in the next screenshot, you can see that I'm using just 58.6 MB, no problem.

I'll run the installer by entering my password. And once I enter my password, it should really only take a couple of seconds to get Node installed:

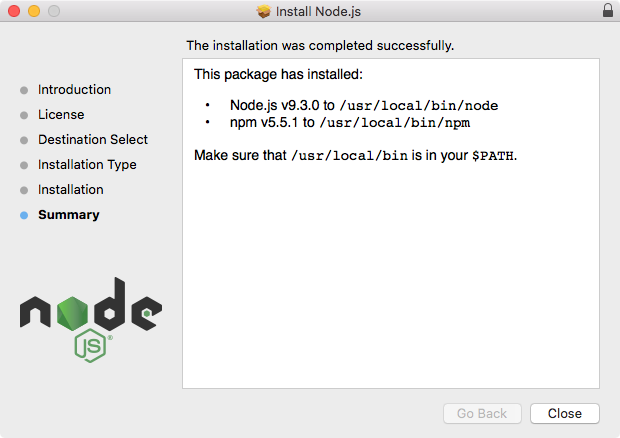

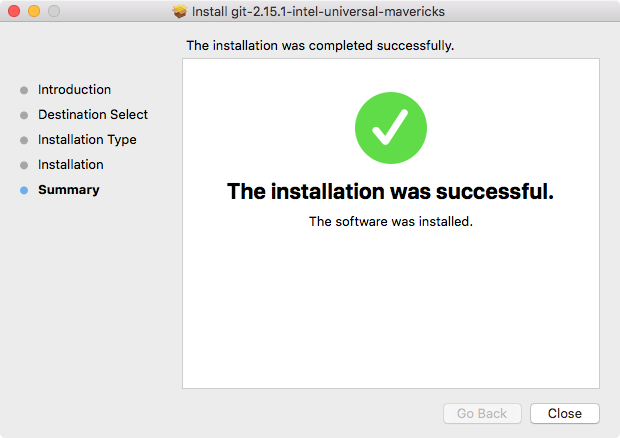

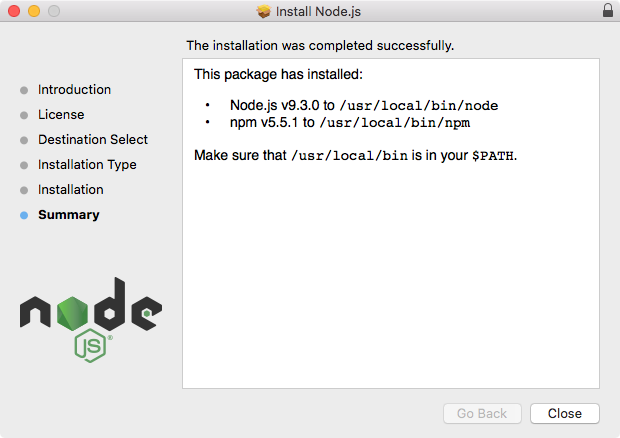

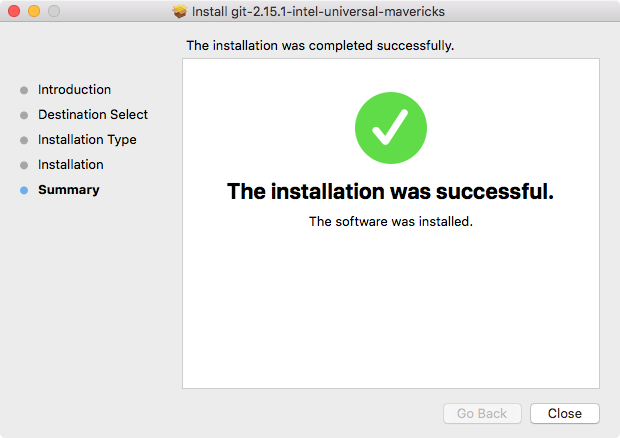

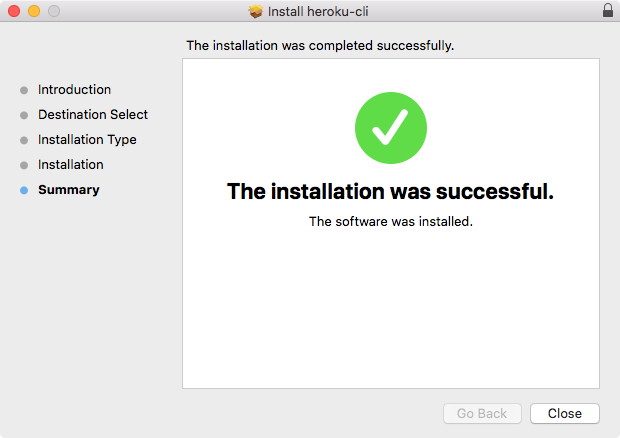

As shown in the following screenshot, we have a message that says The installation was completed successfully, which means we are good to go:

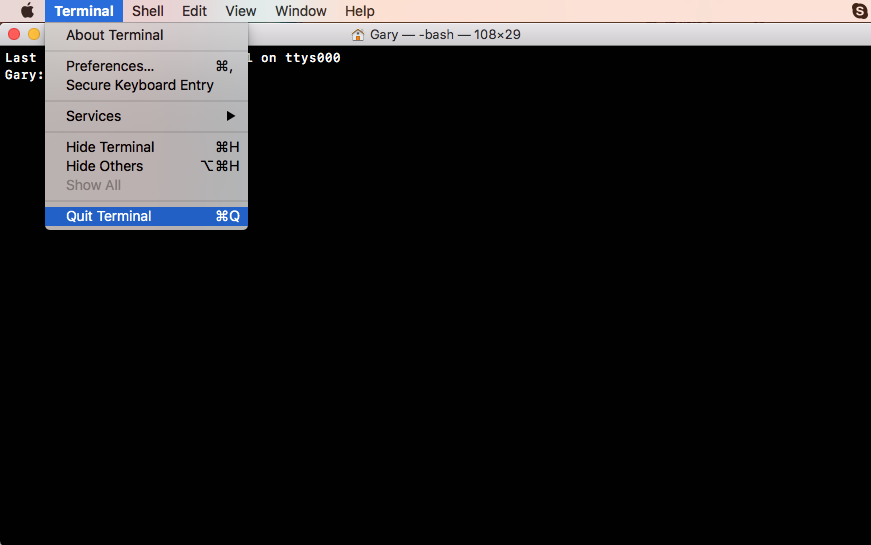

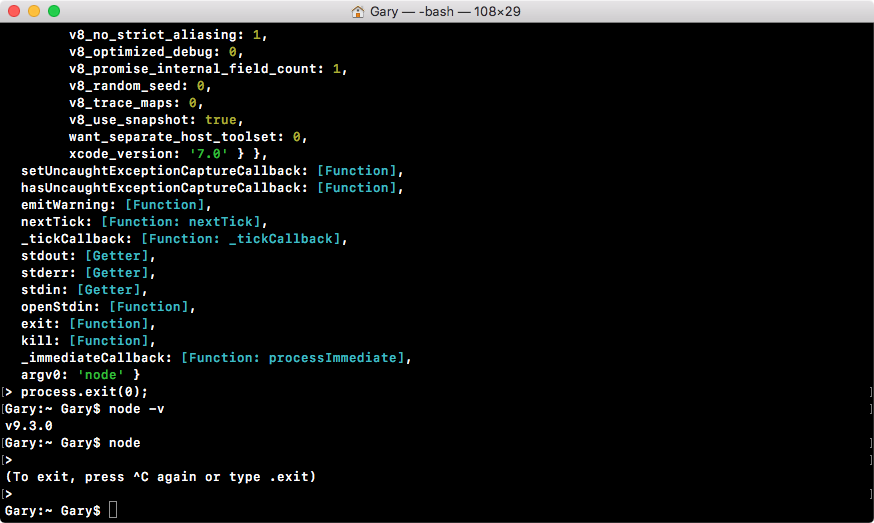

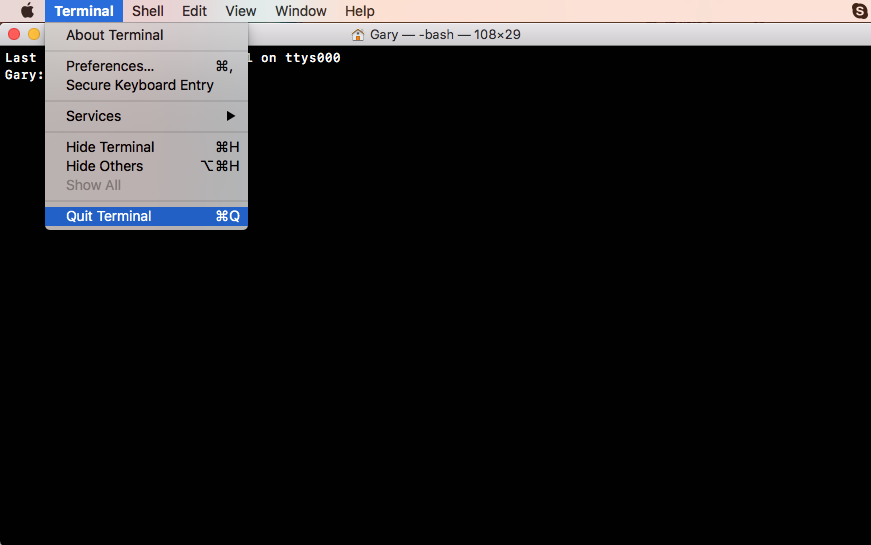

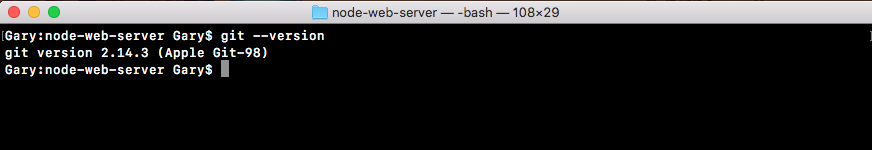

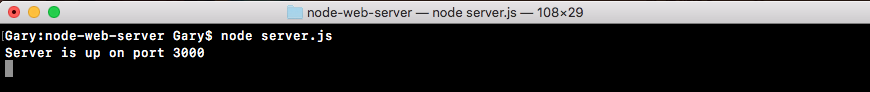

Now that Node has been installed successfully, we can go ahead and verify that by running Node from Terminal. Inside Terminal, I'll shut it down by going to Quit Terminal and open it up again:

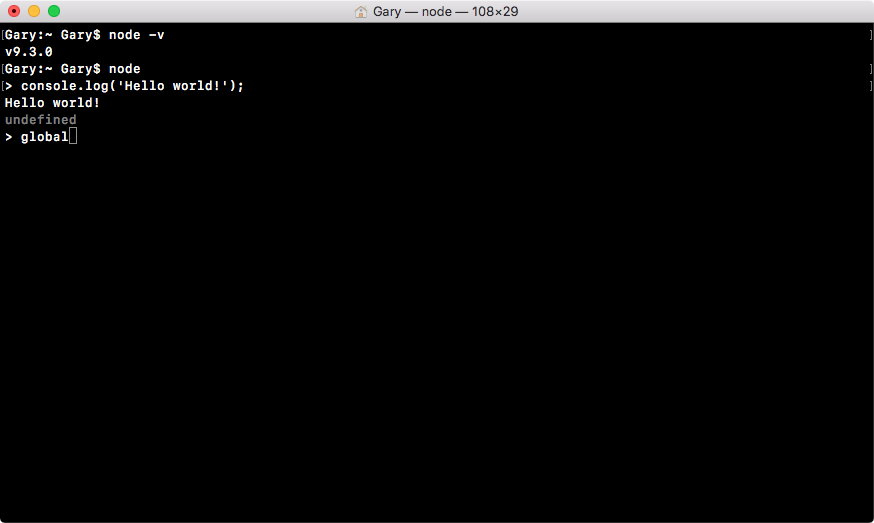

In our case, we restarted things and we can run our brand new command so, we'll type it:

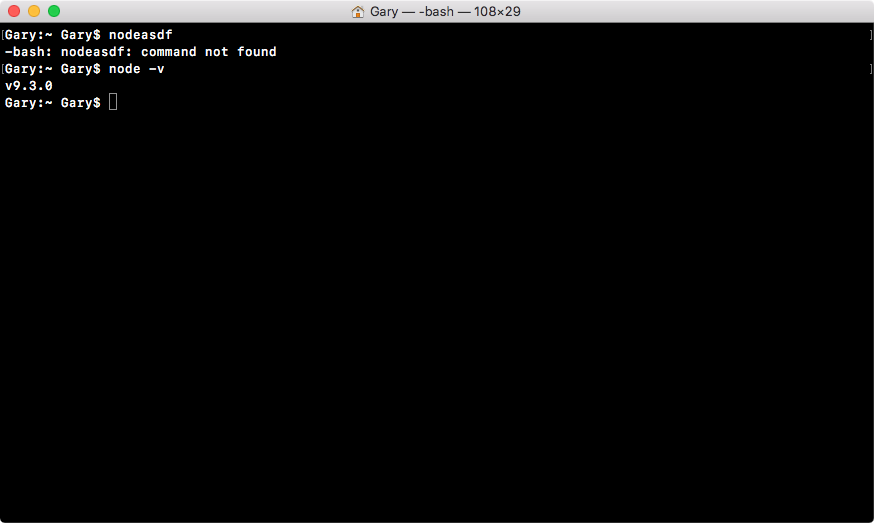

node -v

What we're doing in this command is we're running the Node command, and we're passing in what's called a flag, a hyphen sign followed by a letter. It could be a, it could be j, or in our case it's v. This command will print the version of Node currently installed.

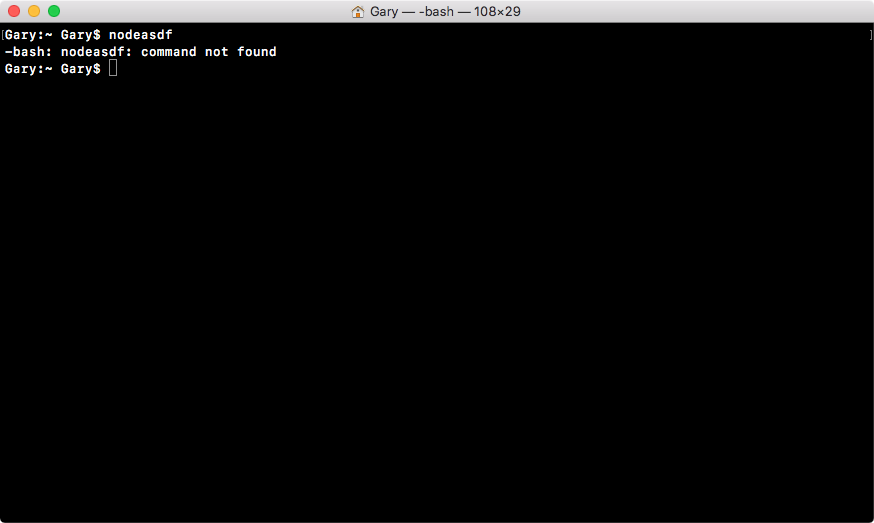

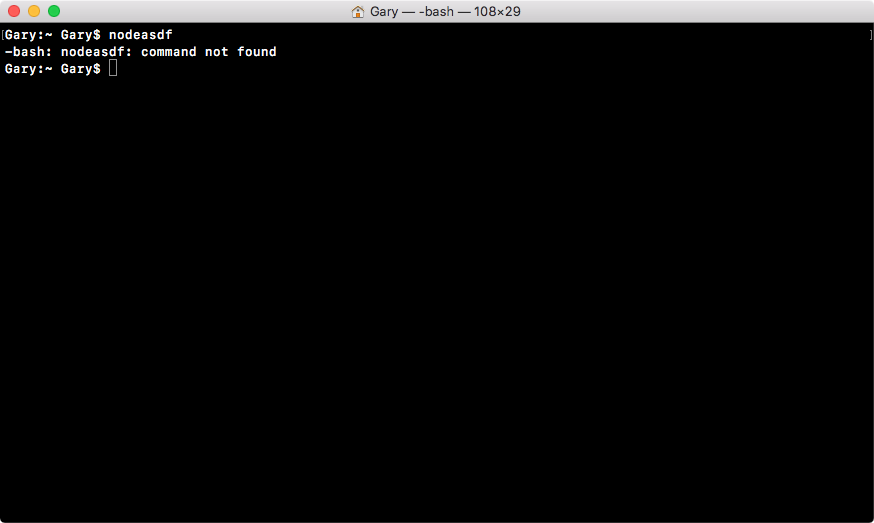

We might get an error like this:

If you try to run a command that doesn't exist, such as nodeasdf, you'll see command not found. If you see this, it usually means the Node installer didn't work correctly, or you haven't run it in the first place.

In our case though, running Node with the v flag should result in a number. In our case, it's version 9.3.0. If you do have Node installed, and you see something like the following screenshot, then you are done. In the next section, we'll start exploring exactly what Node is.

Node came about when the original developers took JavaScript, something you could usually only run inside the browser, and they let it run on your machine as a standalone process. This means that we could create applications using JavaScript outside the context of the browser.

Now, JavaScript previously had a limited feature set. When I used it in the browser, I could do things such as update the URL and remove the Node logo, adding click events or anything else, but I couldn't really do much more.

With Node, we now have a feature set that looks much more similar to other languages, such as Java, Python, or PHP. Some of these are as follows:

These were things that were not possible in the past, and they are because of Node.

Now, both Node and the JavaScript that gets executed inside of your browser, they're both running on the exact same engine. It's called the V8 JavaScript runtime engine. It's an open source engine that takes JavaScript code and compiles it into much faster machine code. And that's a big part of what makes Node.js so fast.

Machine code is low-level code that your computer can run directly without needing to interpret it. Your machine only knows how to run certain types of code, for example, your machine can't run JavaScript code or PHP code directly without first converting it into low-level code.

Using this V8 engine, we can take our JavaScript code, compile it to much quicker machine code, and execute that. This is where all those new features come in. The V8 engine is written in a language called C++. So if you want to extend the Node language, you don't write Node code, you write C++ code that builds off of what V8 already has in place.

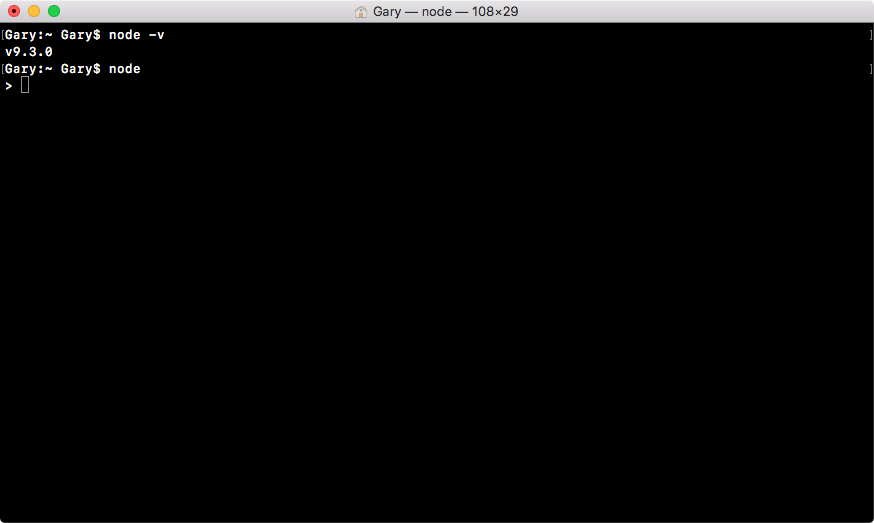

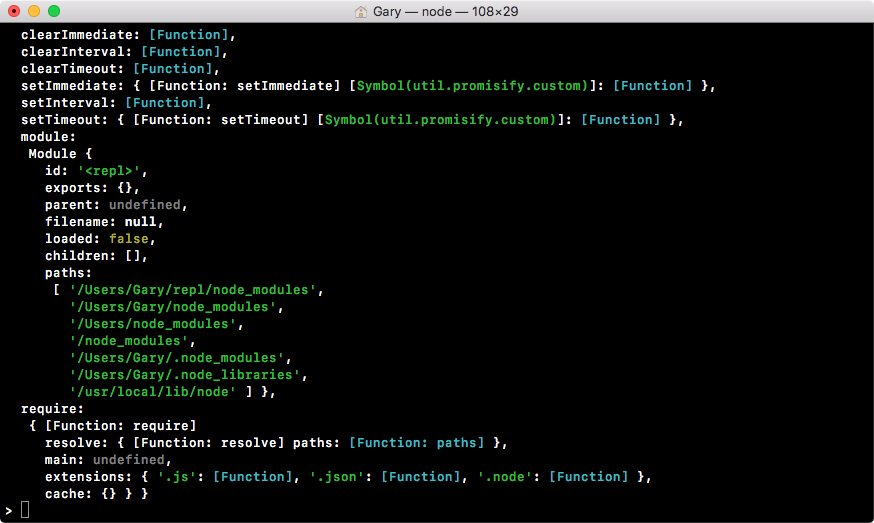

Speaking of JavaScript code, let's start writing some inside Terminal. Now, throughout the book, we'll be creating files and executing those files, but we can actually create a brand new Node process by running the node command.

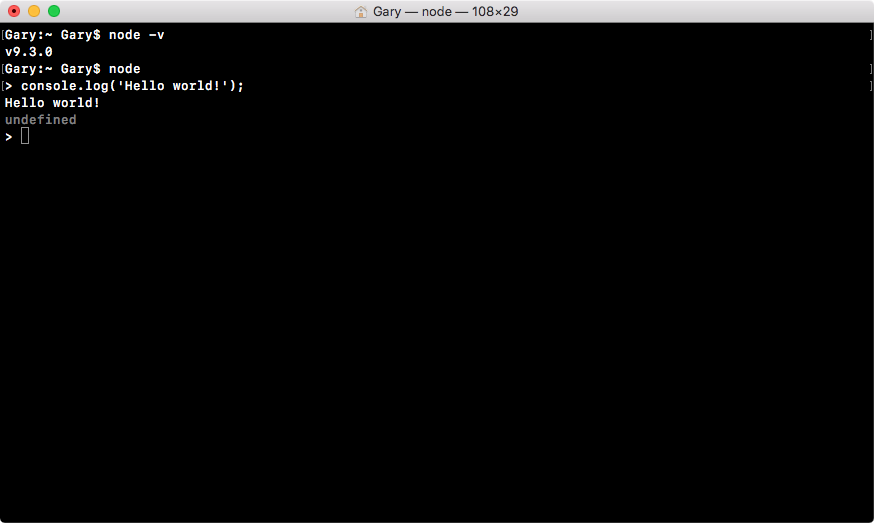

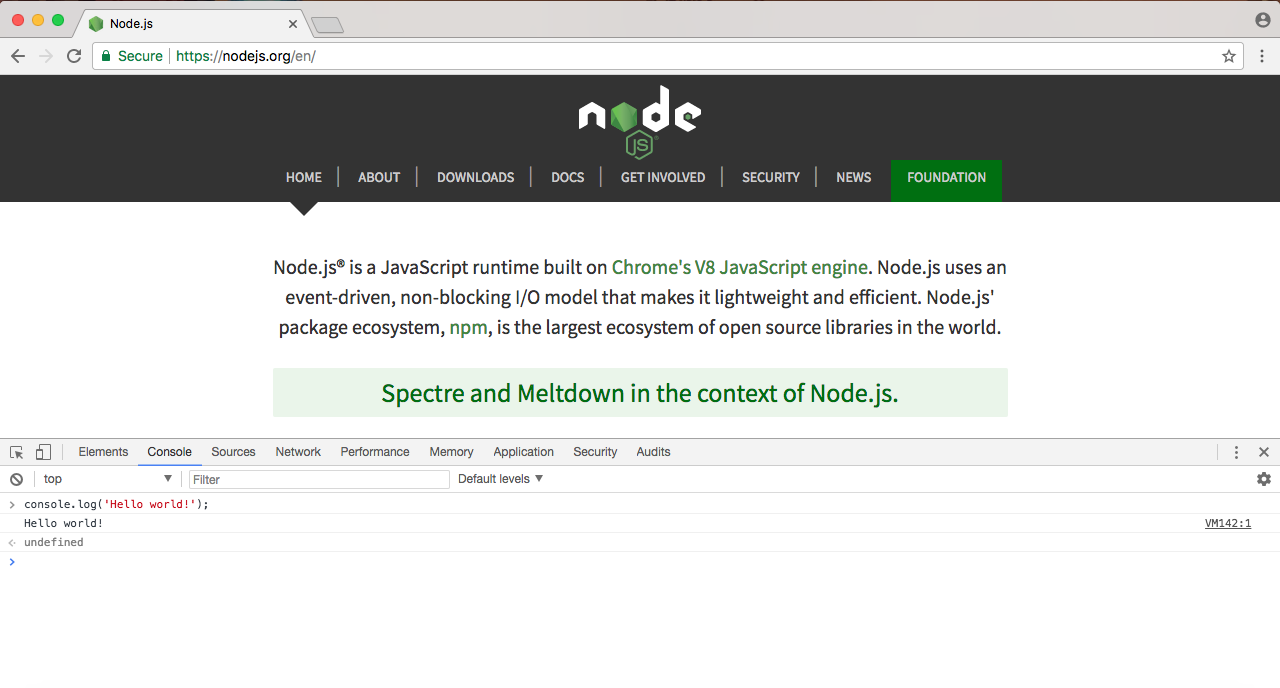

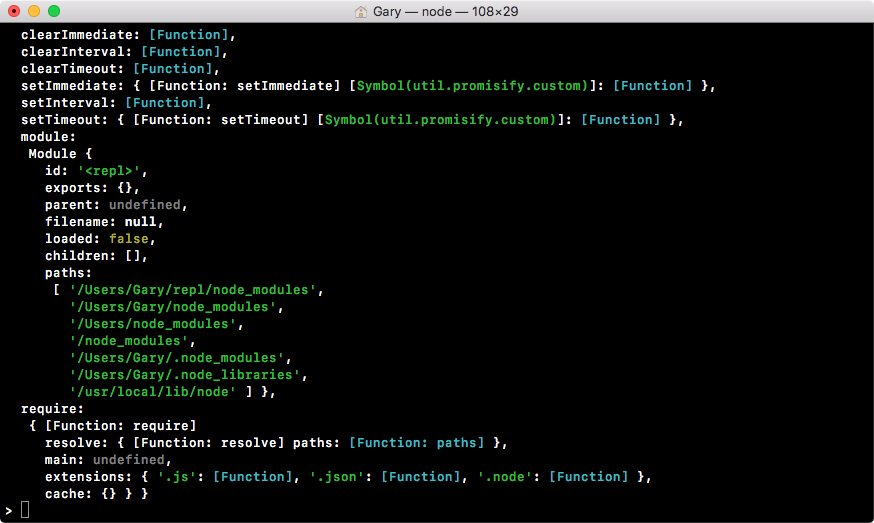

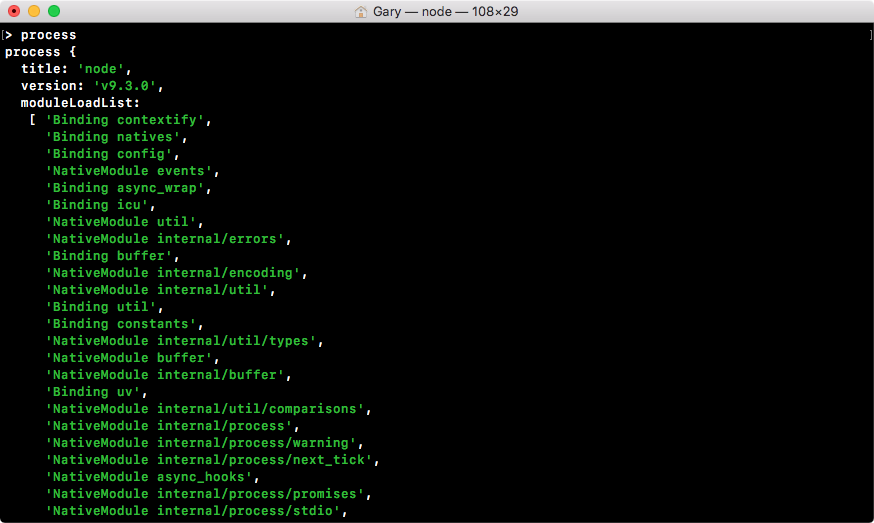

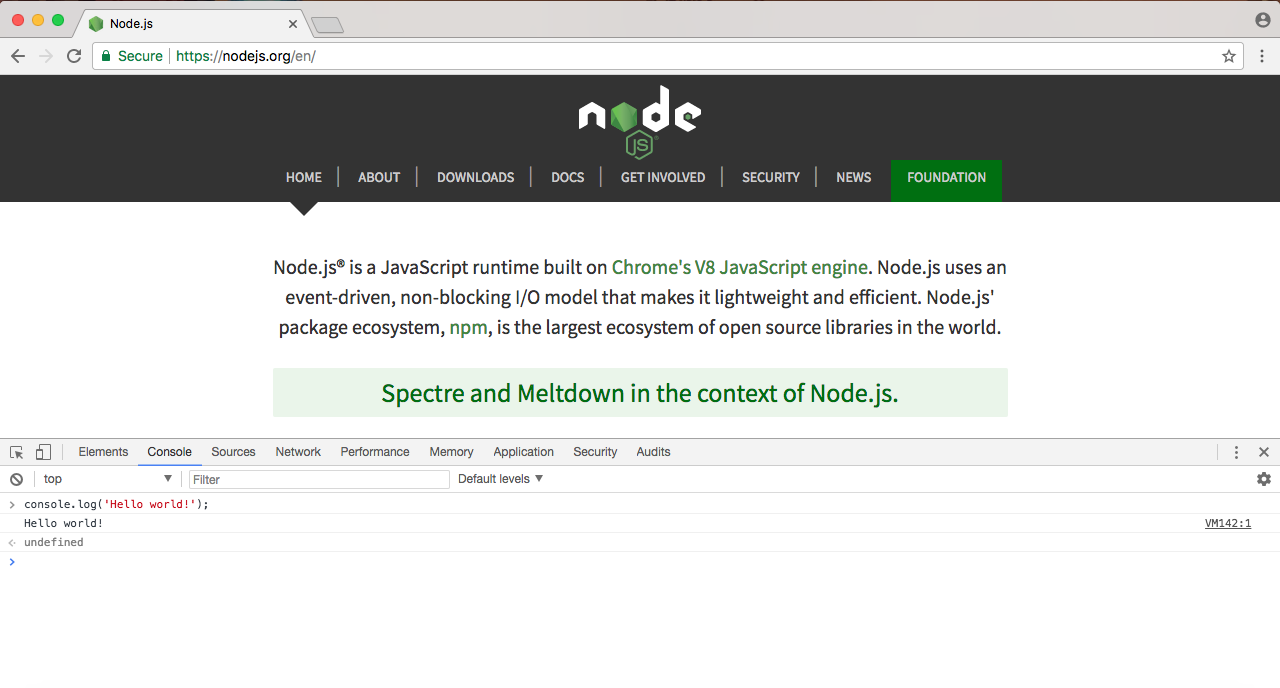

Referring to the following screenshot, I have a little right caret, which is waiting for JavaScript Node code, not a new command-prompt command:

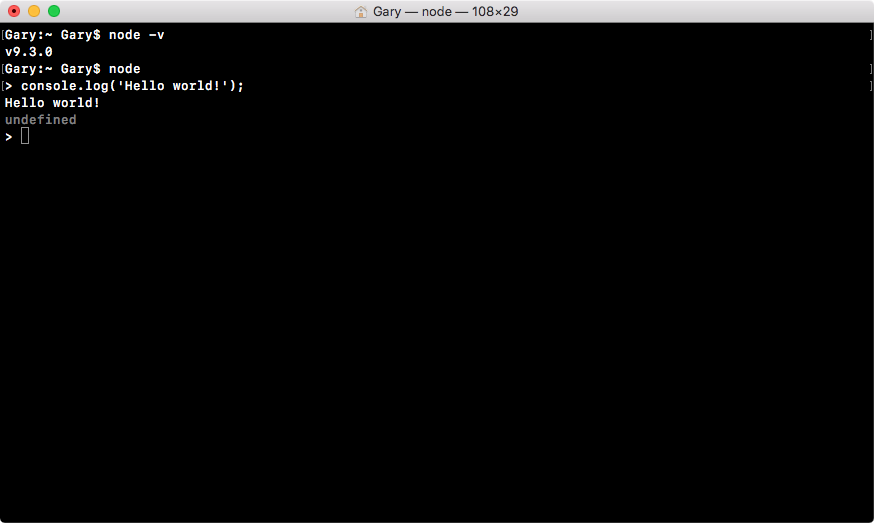

This means that I can run something like console.log, which, as you probably already know, logs a message to the screen. log is a function, so I'll call it as such, opening and closing my parentheses, and passing in a string inside two single quotes, a message Hello world!, as shown in the following command line:

console.log('Hello world!');

This will print Hello world to the screen. If I hit enter, Hello world! prints just like you'd expect, as shown in the following code output:

Now, what actually happened behind the scenes? Well, this is what Node does. It takes your JavaScript code, it compiles it into machine code, and executes it. In the preceding code, you can see it executed our code, printing out Hello world!. Now, the V8 engine is running behind the scenes when we execute this command, and it's also running inside the Chrome browser.

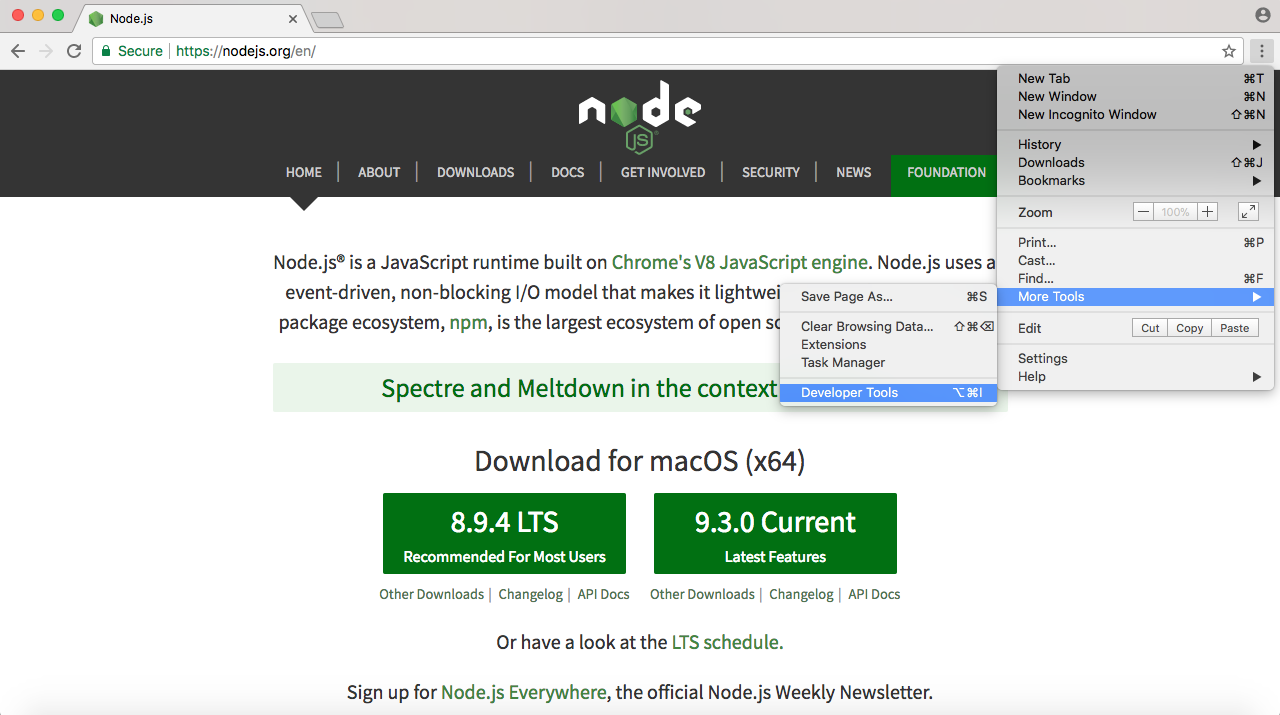

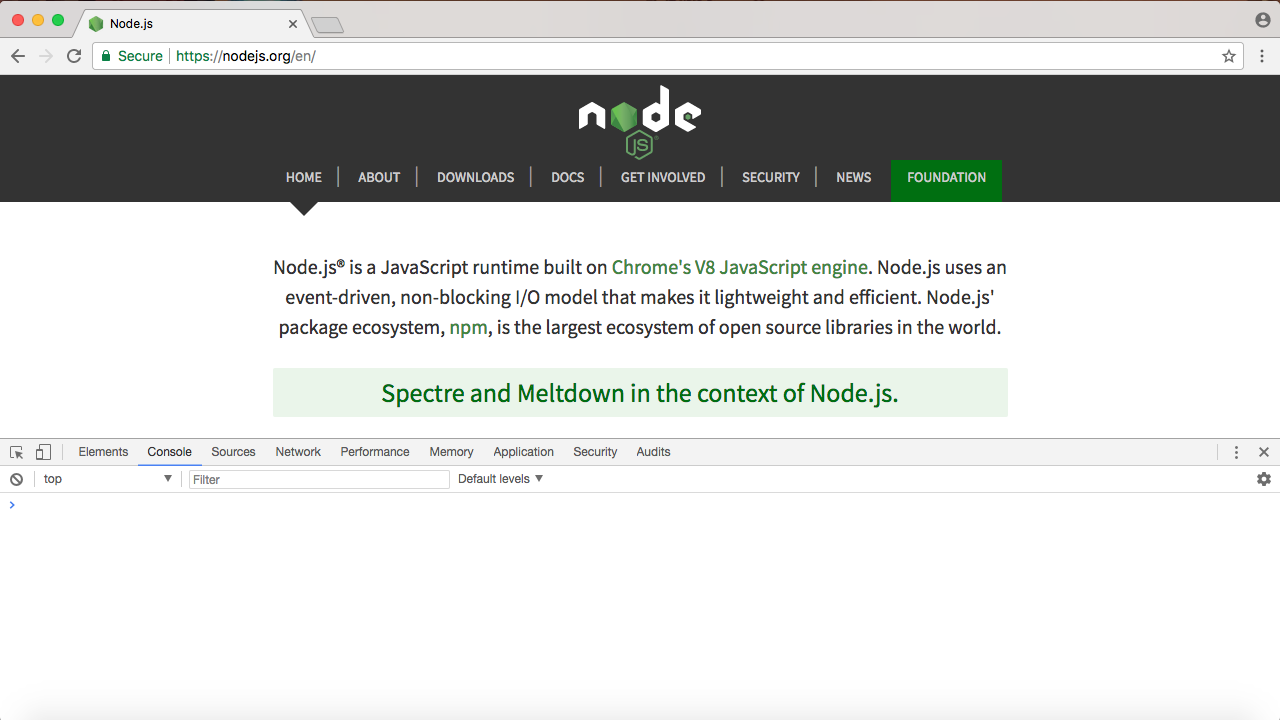

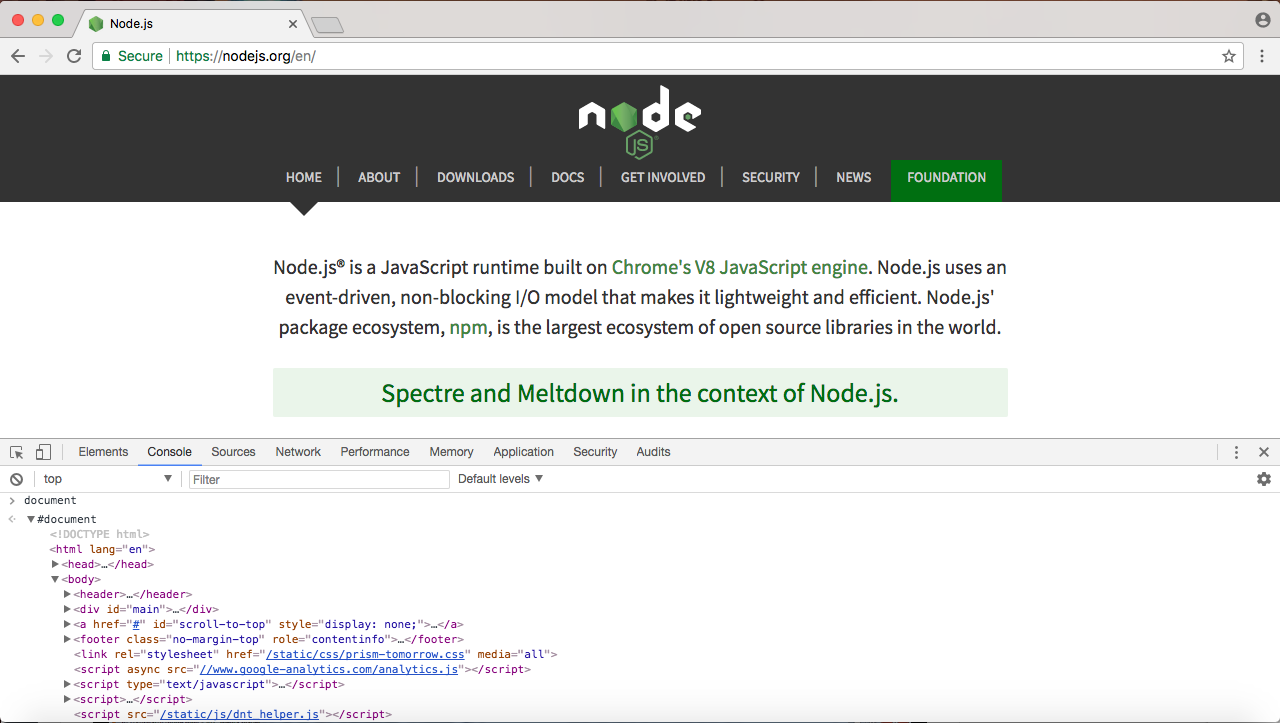

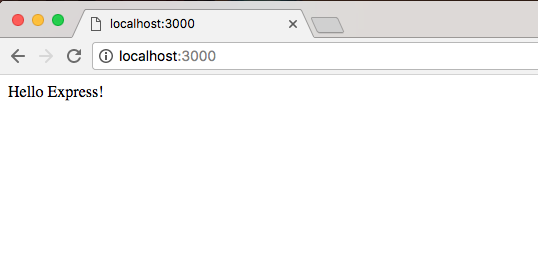

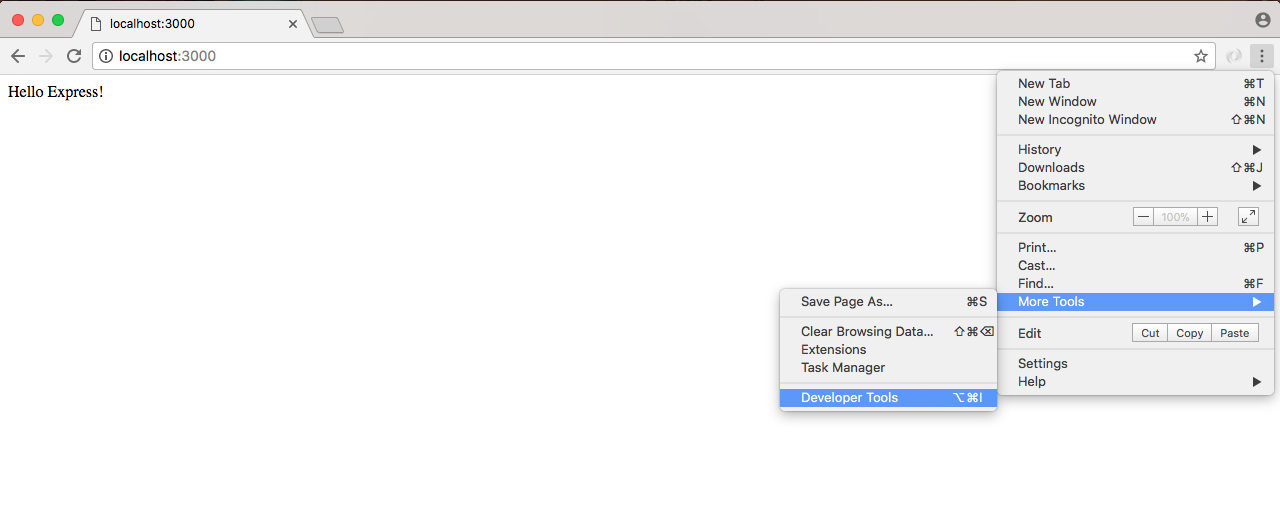

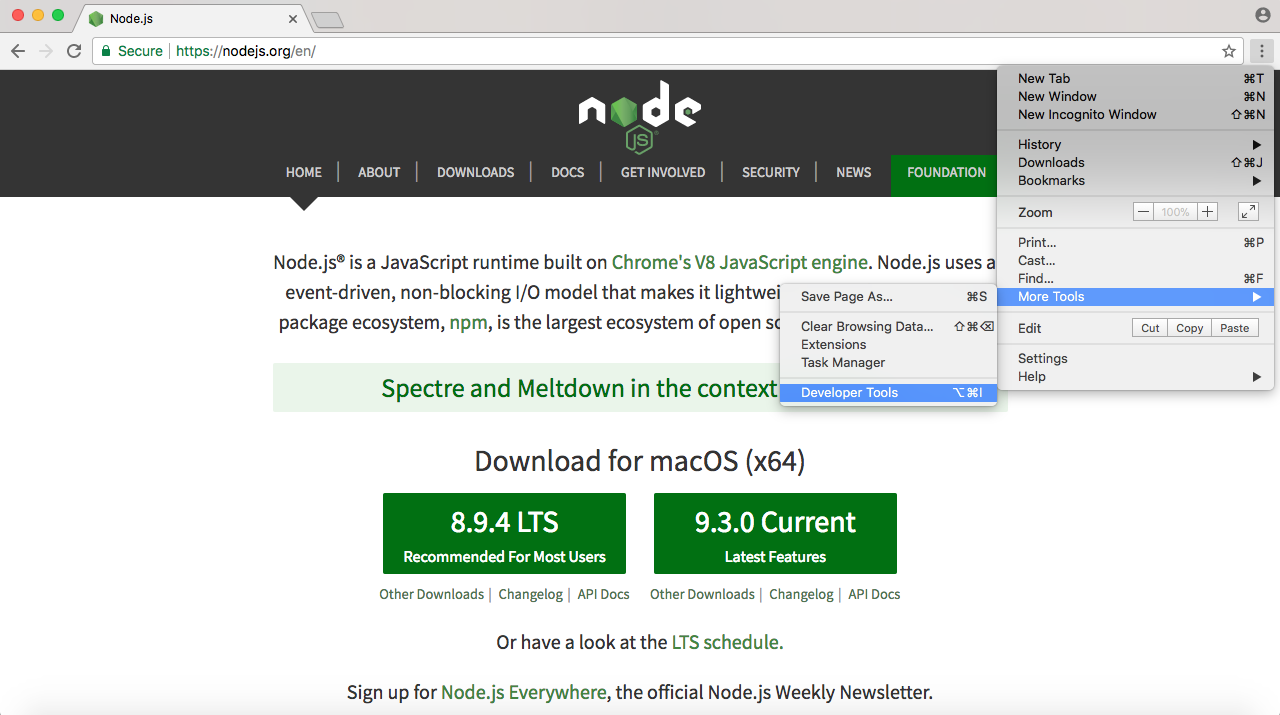

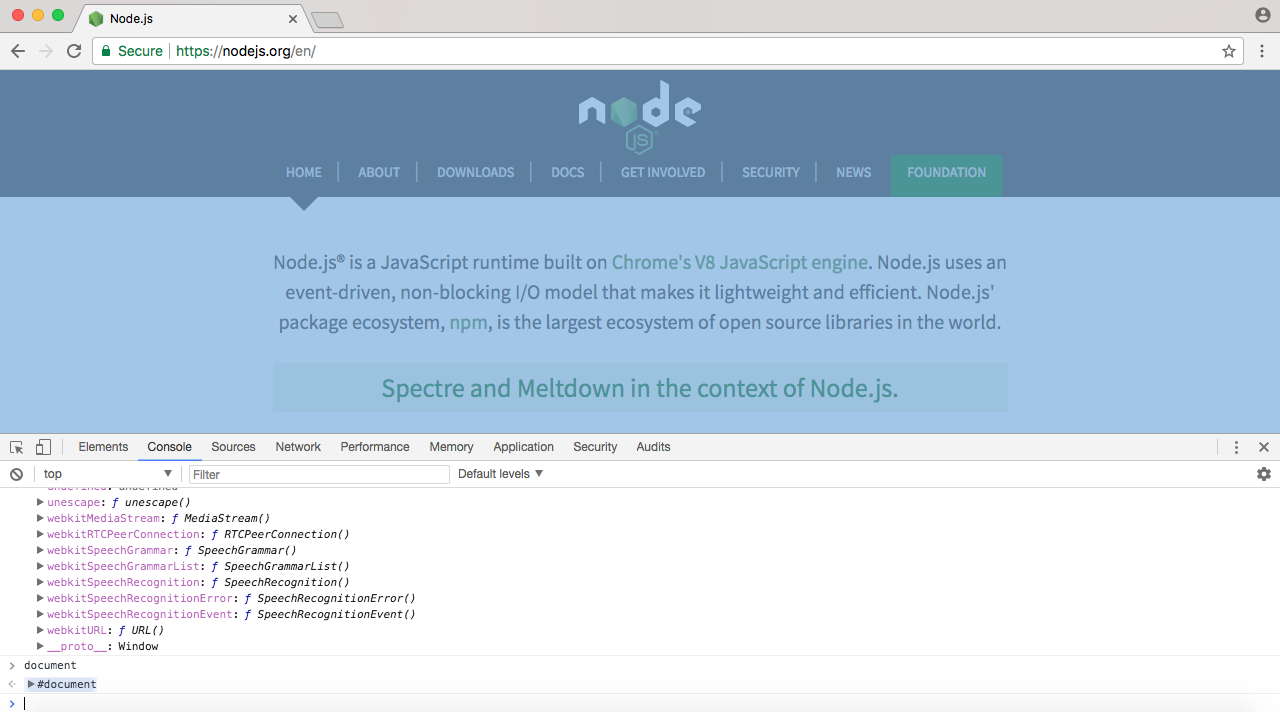

If I open up the developer tools in Chrome by going to Settings | More Tools | Developer Tools:

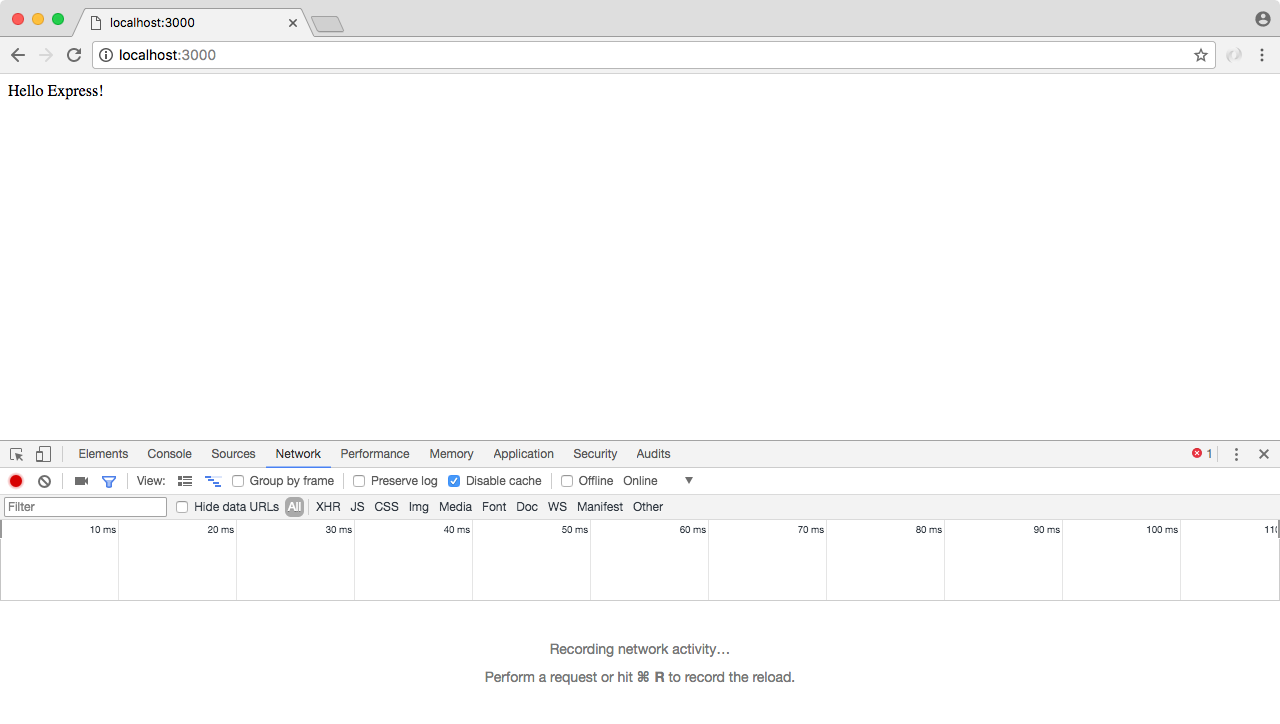

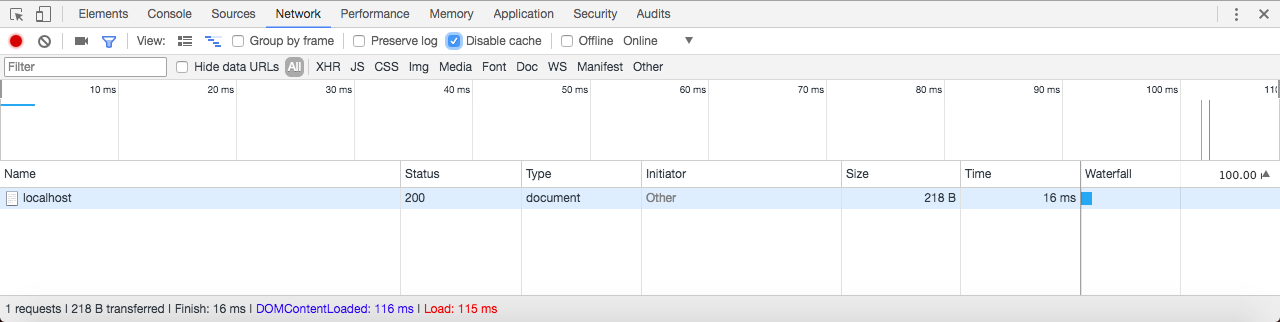

I can ignore most of the things. I'm just looking for the Console tab, as shown in the following screenshot:

The preceding screenshot showing the console is a place where we can run some JavaScript code. I can type the exact same command, console.log('Hello world!'); and run it:

As you can see in the preceding screenshot, Hello world! prints to the screen, which is the exact same result we got when we ran it up earlier using Terminal. In both cases, we're running it through the V8 engine, and in both cases the output is the same.

Now, we already know that the two are different. Node has features such as filesystem manipulation, and the browser has features such as manipulating what's shown inside the window. Let's take a quick moment to explore their differences.

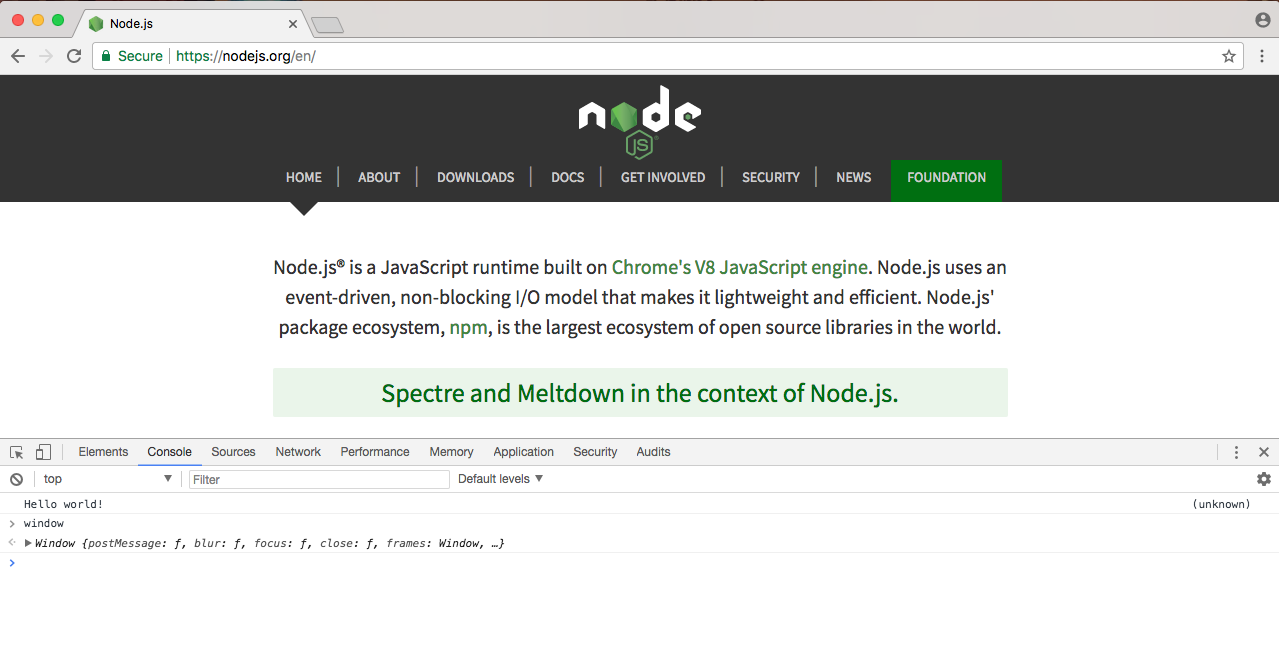

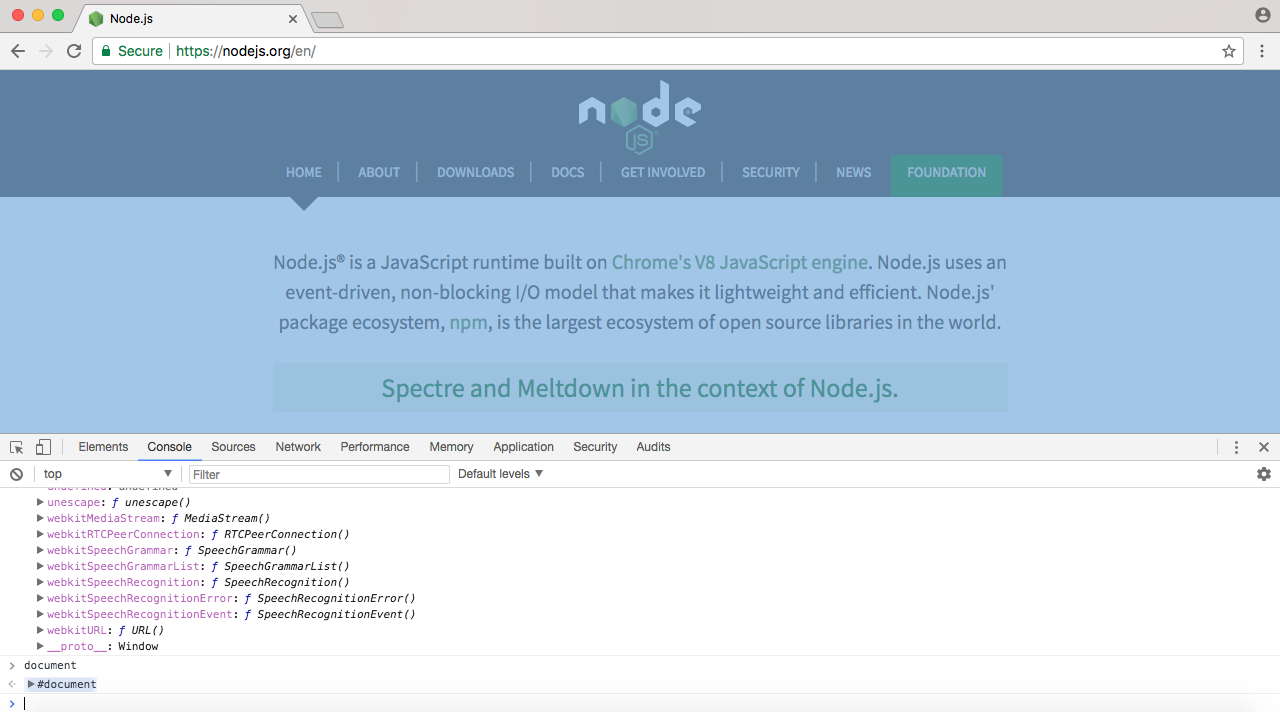

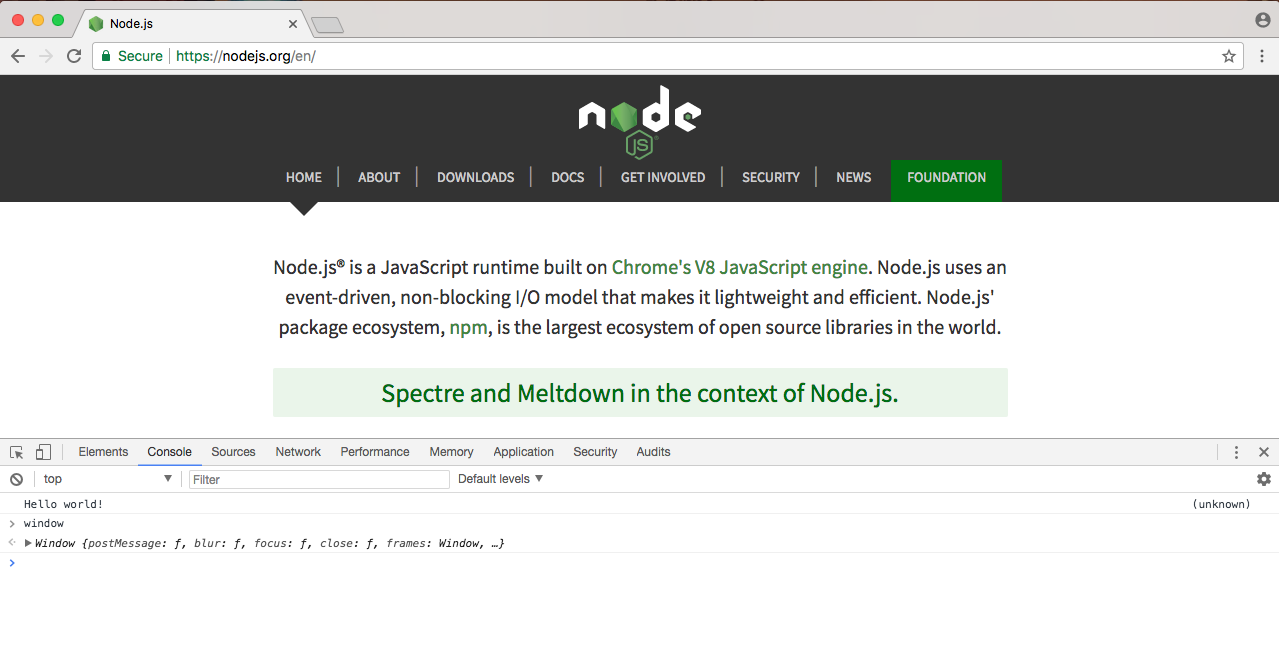

Inside the browser, you've probably used window if you've done any JavaScript development:

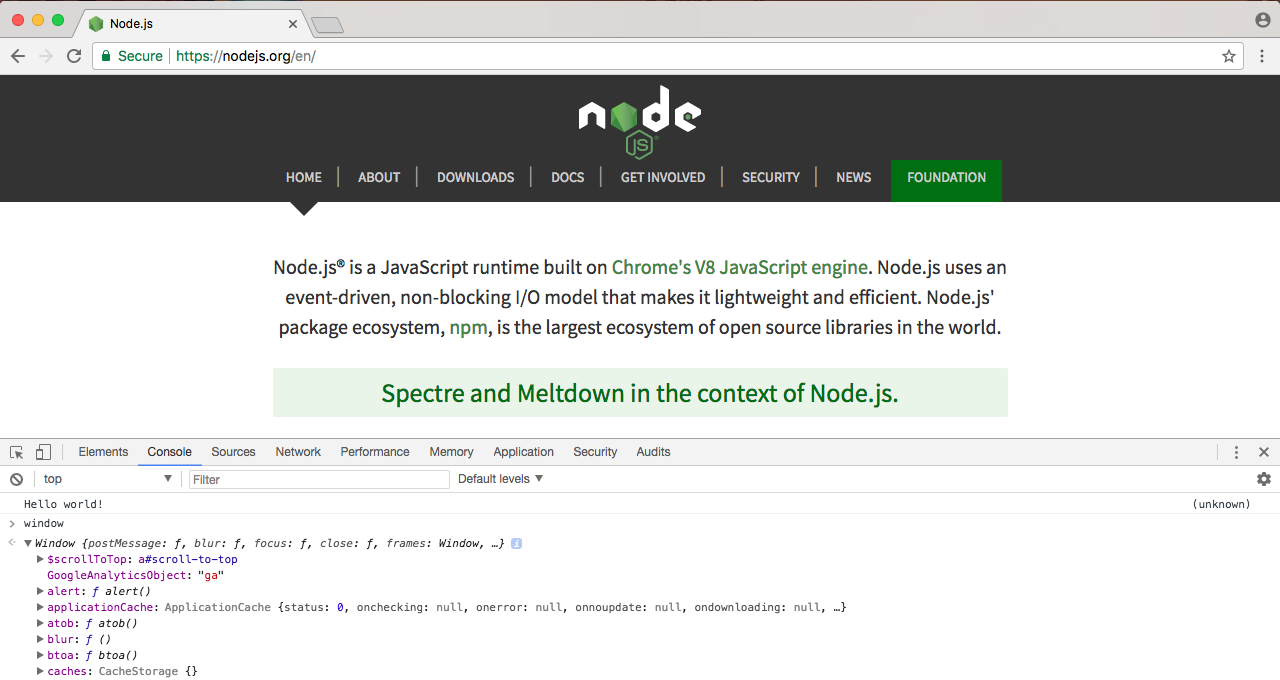

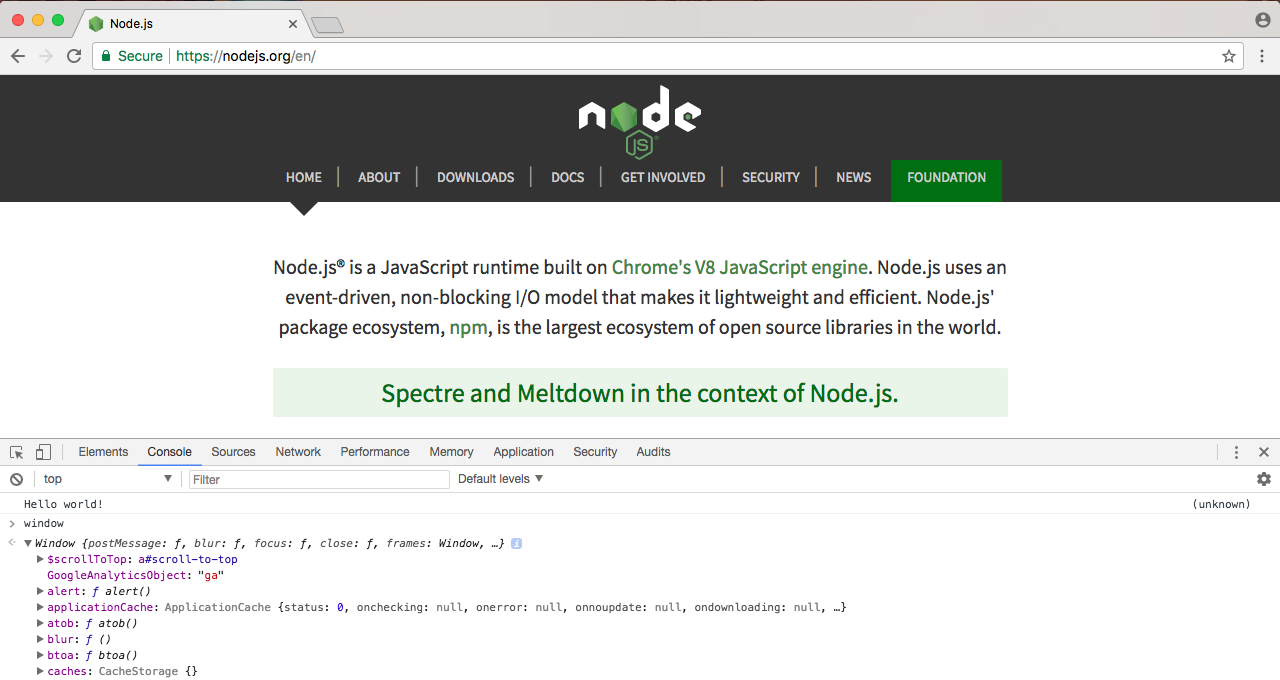

Window is the global object, it stores basically everything you have access to. In the following screenshot, you can see things such as array, we have all sorts of CSS manipulation and Google Analytics keywords; essentially every variable you create lives inside Window:

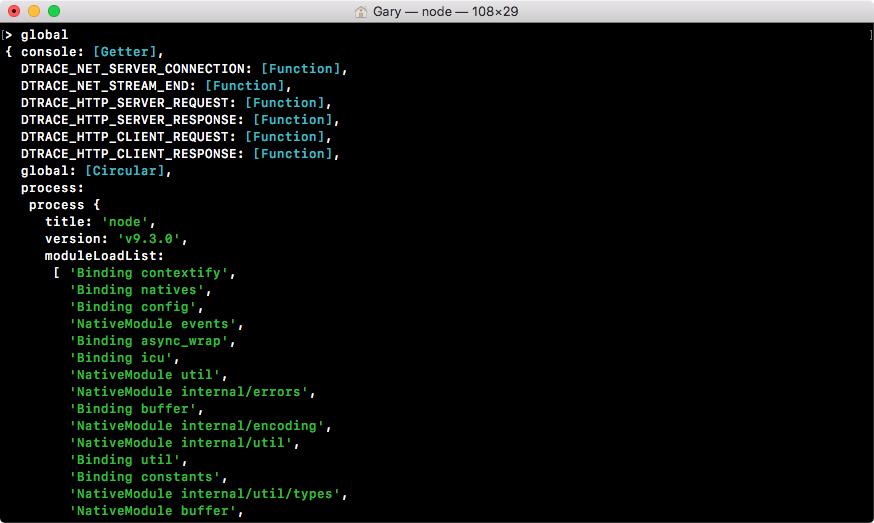

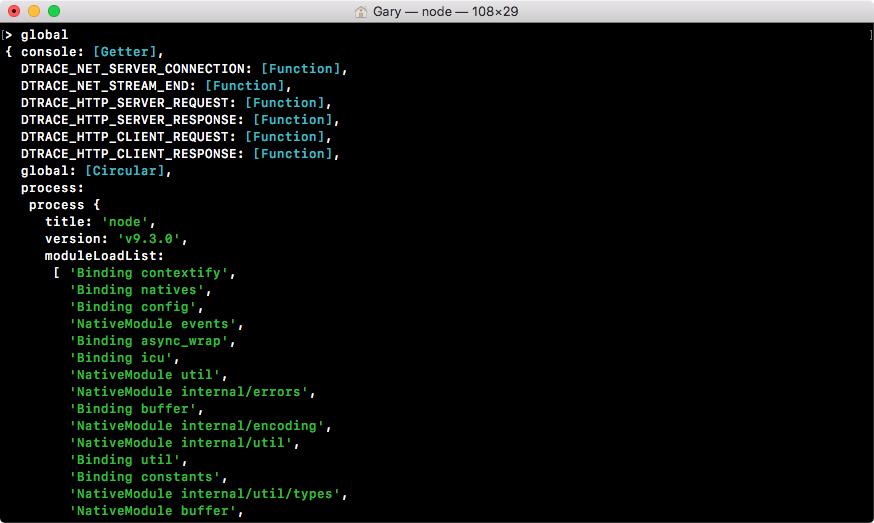

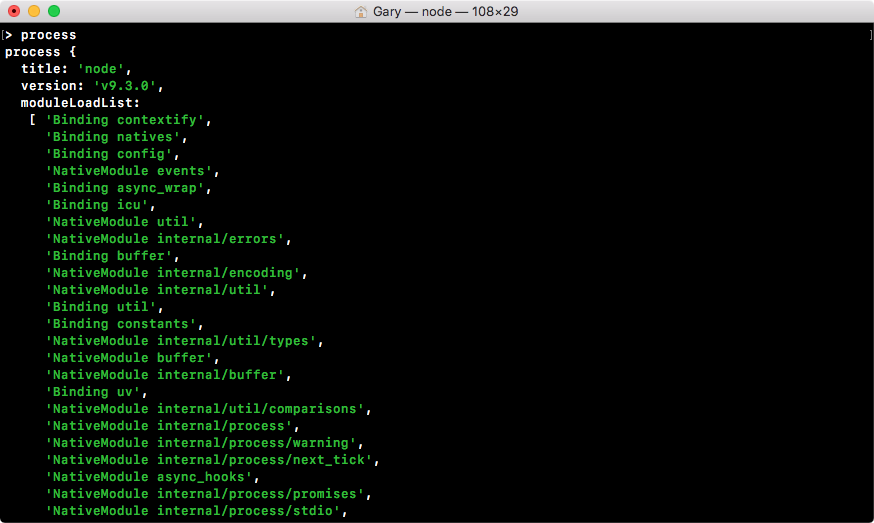

We have something similar inside Node called global, as shown here:

It's not called window because there is no browser window in Node, thus it is called global. The global object stores a lot of the same things as window. In the following screenshot, you can see methods that might be familiar, such as setTimeout and setInterval:

If we look at this code screenshot, we have most of the things that are defined inside the window, with some exceptions, as shown in the following screenshot:

Now, inside the Chrome browser, I also have access to document:

The document object stores a reference to the Document Object Model (DOM) in the Node website. The document object shows exactly what I have inside the browser's viewport, as shown in the following screenshot:

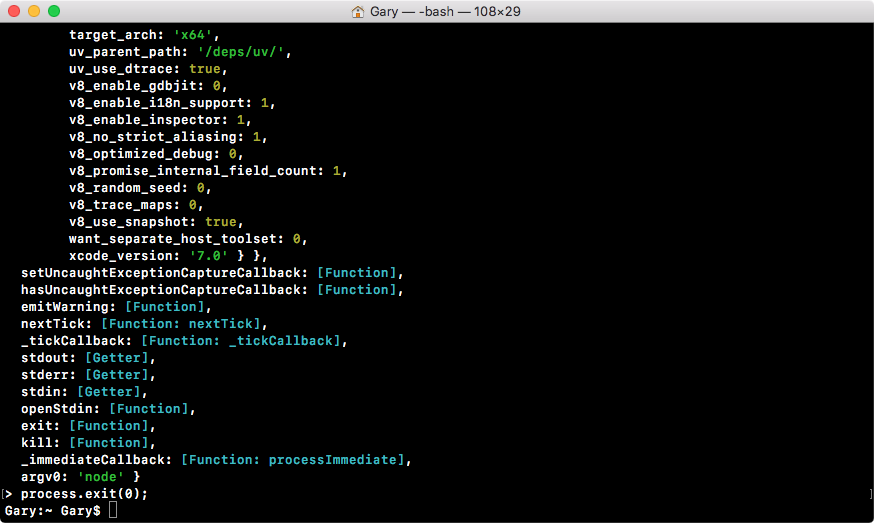

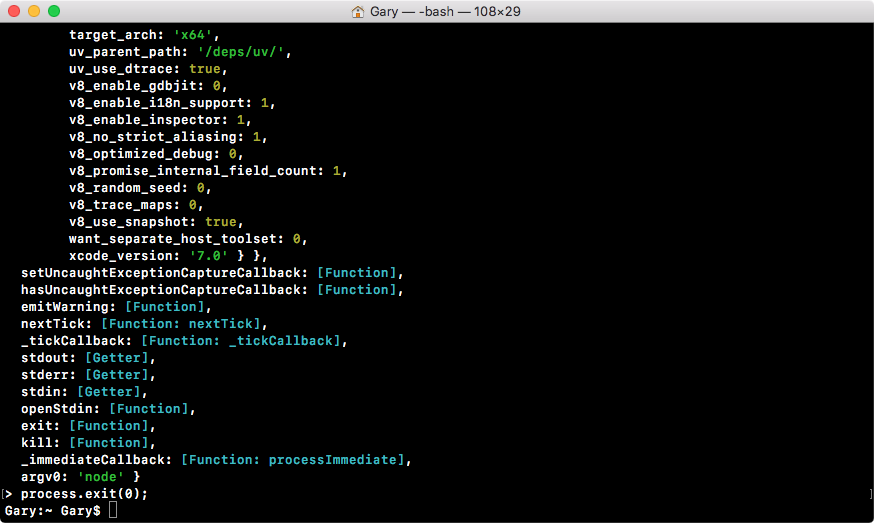

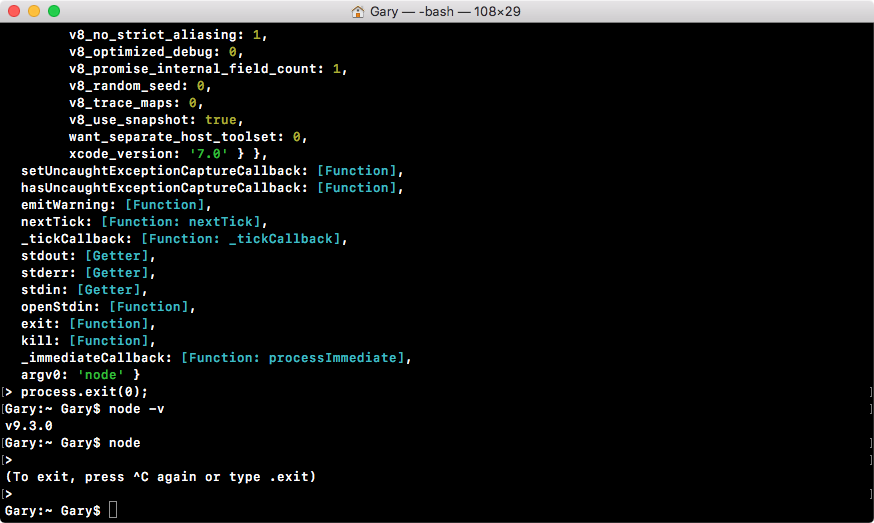

I can make changes to the document to update what gets shown up on the browser's viewport. Now, obviously we don't have this HTML document inside Node, but we do have something similar, which is called process. You can view it by running process from Node, and in the following screenshot, we have a lot of information about the specific Node process that's being executed:

There's also methods available here to shut down the current Node process. What I'd like you to do is run the process.exit command, passing in as an argument the number zero, to say that things exited without error:

process.exit(0);

When I run this command, you can see I'm now back at the command prompt, as shown in the following screenshot:

I've left Node, and I'm at a place where I can run any regular command prompt command, such as checking my Node version. I can always get back into Node by running node, and I can leave it without using the process.exit command by using control + C twice.

Now, I'm back at my regular command prompt. So, these are the notable differences, obviously inside the browser you have the viewable area, window gets changed to global, and a document basically becomes process. Now, obviously that's a generalization, but those are some of the big picture changes. We'll be exploring all the minutiae throughout the book.

Now, when someone asks you what is Node? You can say Node's a JavaScript runtime that uses the V8 engine. When they ask you what the V8 engine is, you can say the V8 engine is an open source JavaScript engine written in C++ that takes JavaScript code and compiles it to machine code. It's used inside Node.js and it's used in the Chrome browser.

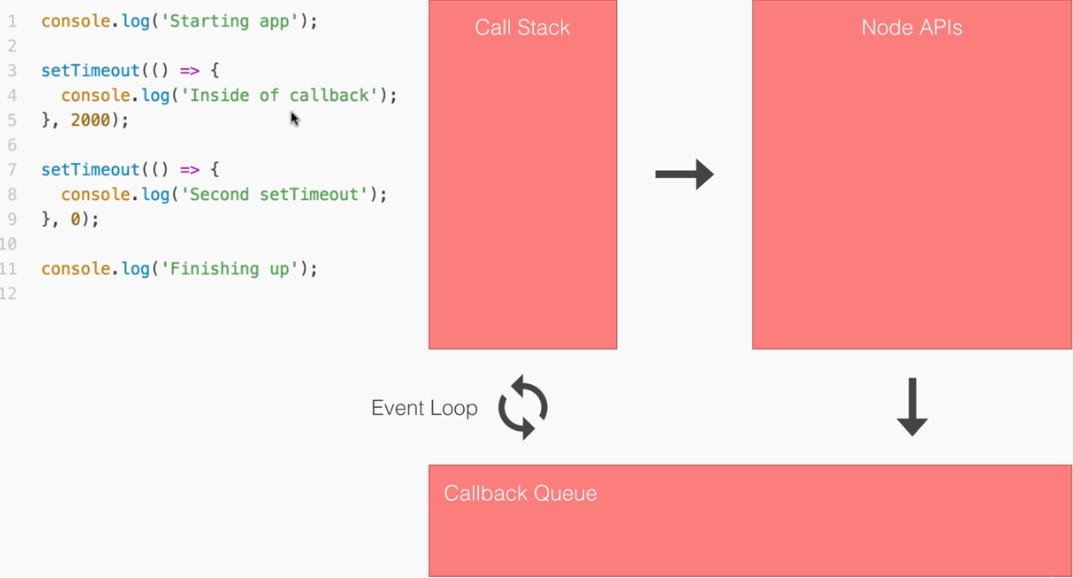

In this section, we'll cover the why behind Node.js. Why is it so good at creating backend apps? And why is it becoming so popular with companies such as Netflix, Uber and Walmart, who are all using Node.js in production?

As you might have noticed since you're taking this course, when people want to learn a new backend language, more and more they're turning to Node as the language they want to learn. The Node skillset is in hot demand, for both frontend developers who need to use Node day to day to do things such as compile their applications, to engineers who are creating applications and utilities using Node.js. All of this has made Node the backend language of choice.

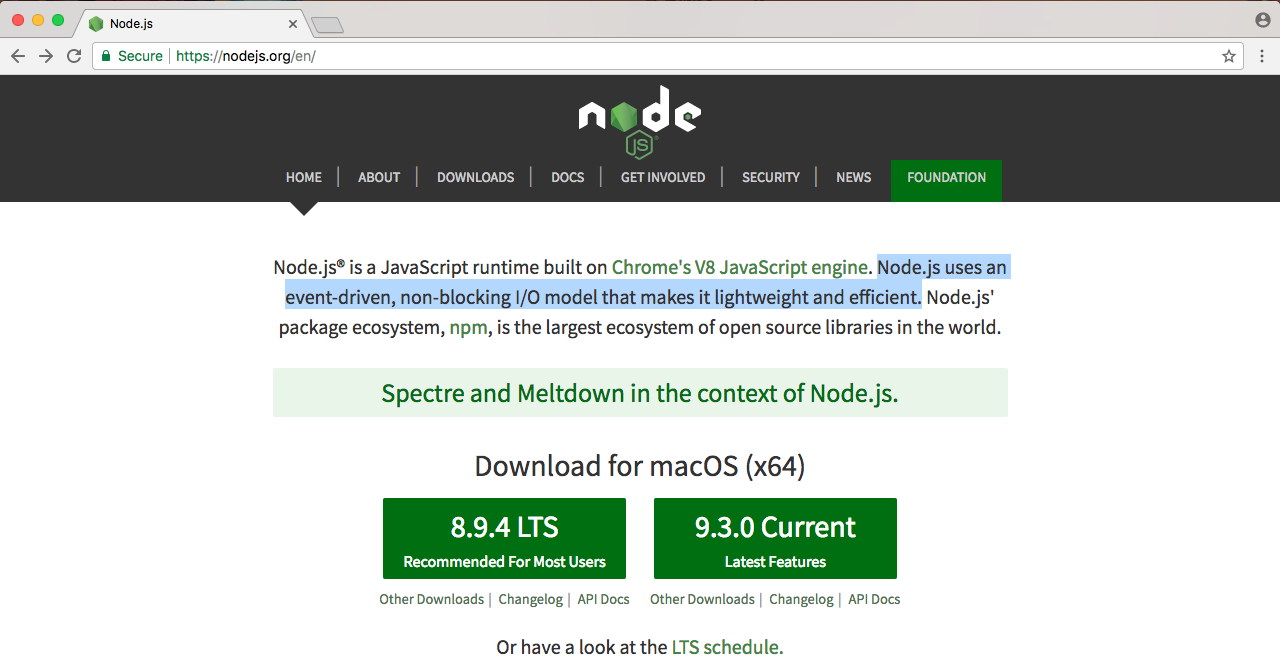

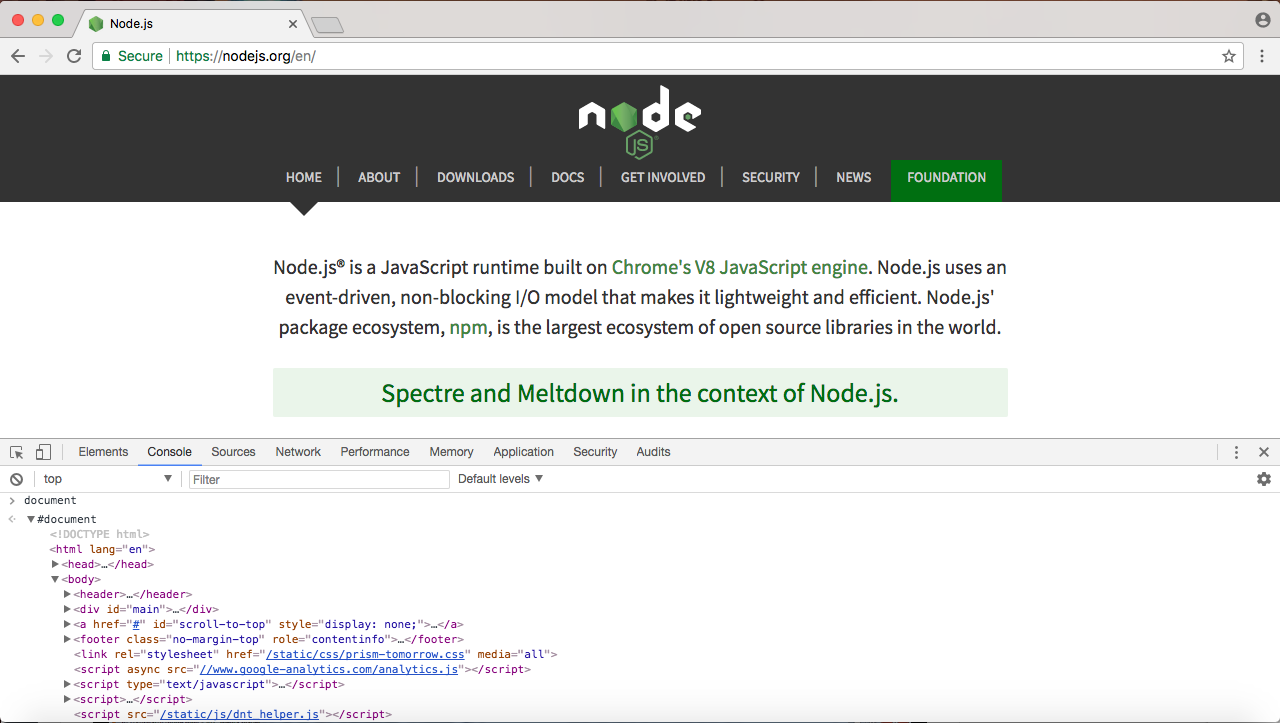

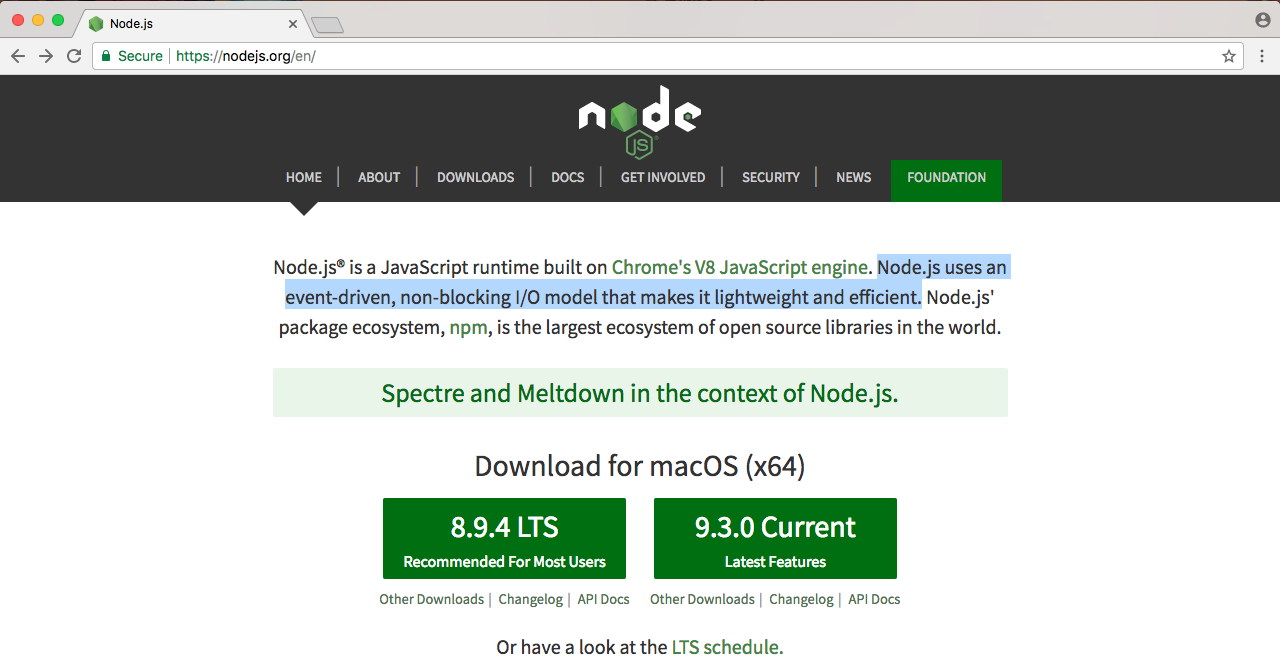

Now, if we look at the homepage of Node, we have three sentences, as shown in the following screenshot:

In the previous section, we addressed the first sentence. We took a look at what Node.js is. There's only three sentences in the image, so in this section, we'll take a look at the second two sentences. We'll read them now, then we'll break it down, learning exactly why Node is so great.

The first sentence, Node.js uses an event-driven, non-blocking I/O model that makes it lightweight and efficient; we'll explore all of this now. The second sentence we'll explore at the end of the section—Node.js' packaged ecosystem, npm, is the largest ecosystem of open source libraries in the world. Now, these two sentences have a ton of information packed into them.

We'll go over a few code examples, we'll dive into some charts and graphs, and we'll explore what makes Node different and what makes it so great.

Node is an event-driven, non-blocking language. Now, what is I/O? I/O is something that your application does all of the time. When you're reading or writing to a database, that is I/O, which is short form for input/output.

This is the communication from your Node application to other things inside of the Internet of Things. This could be a database read and write request, you may be changing some files on your filesystem, or you may be making an HTTP request to a separate web server, such as a Google API for fetching a map for the user's current location. All of these use I/O, and I/O takes time.

Now, the non-blocking I/O is great. That means while one user is requesting a URL from Google, other users can be requesting a database file read and write access, they can be requesting all sorts of things without preventing anyone else from getting some work done.

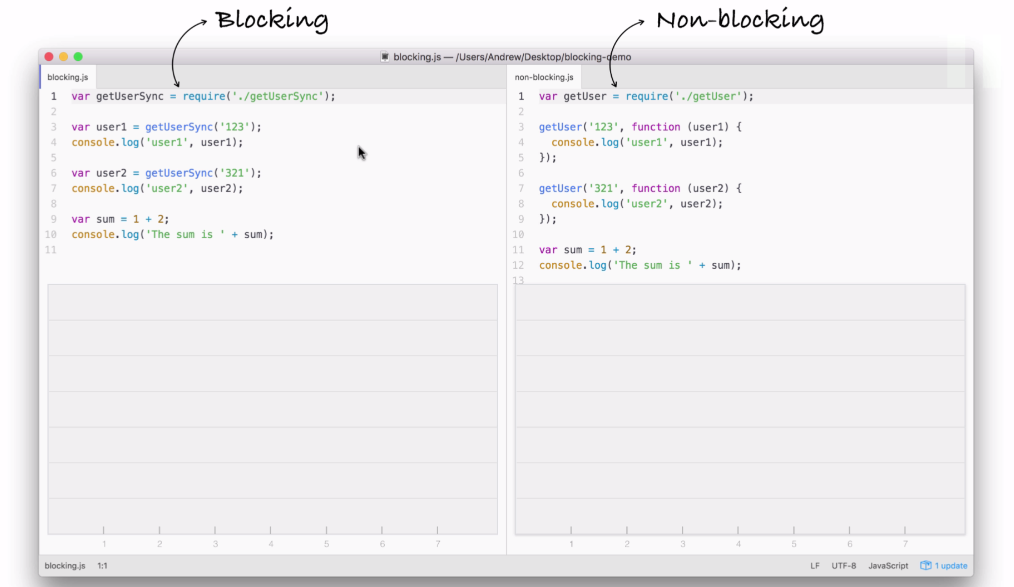

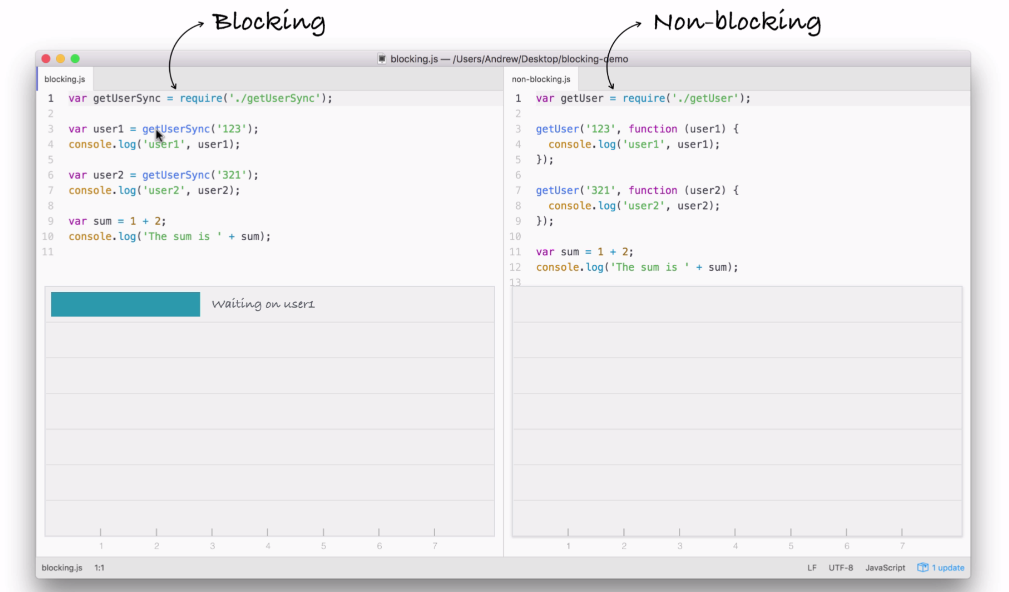

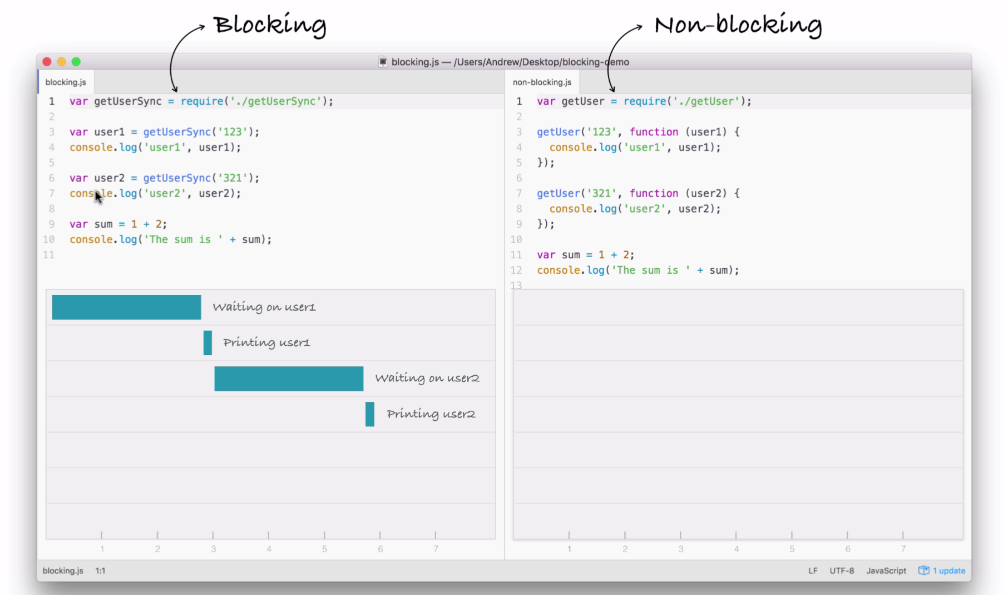

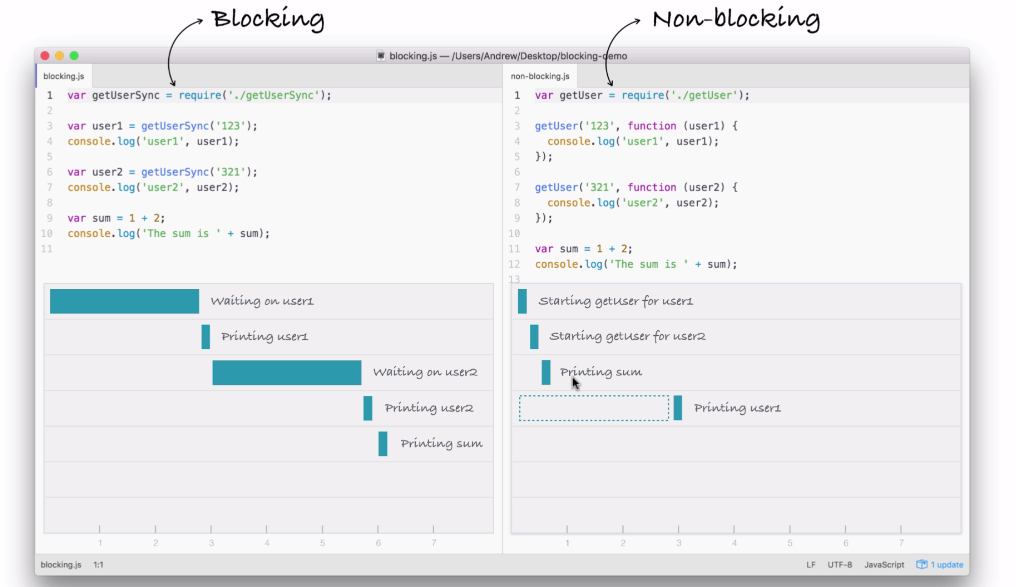

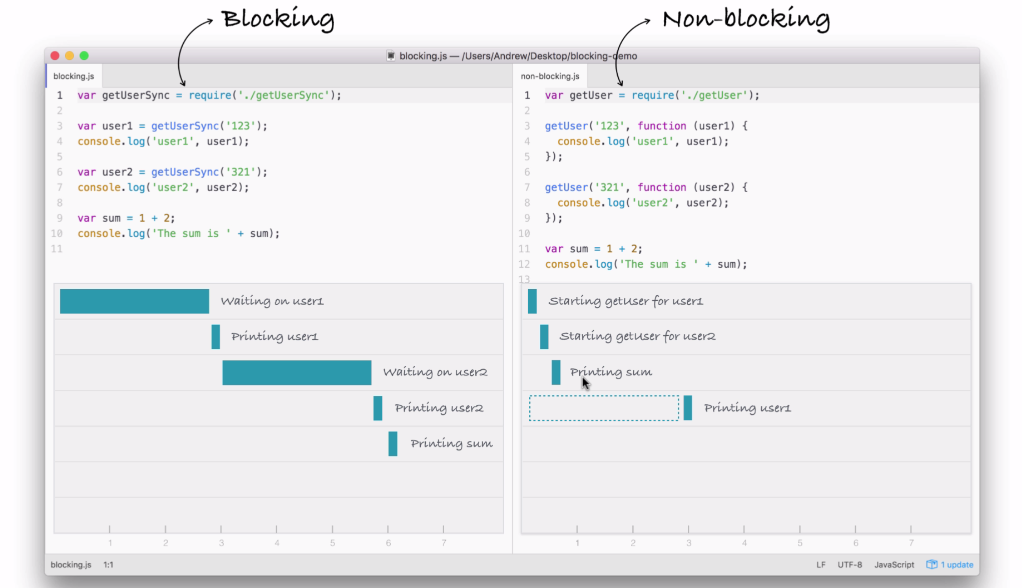

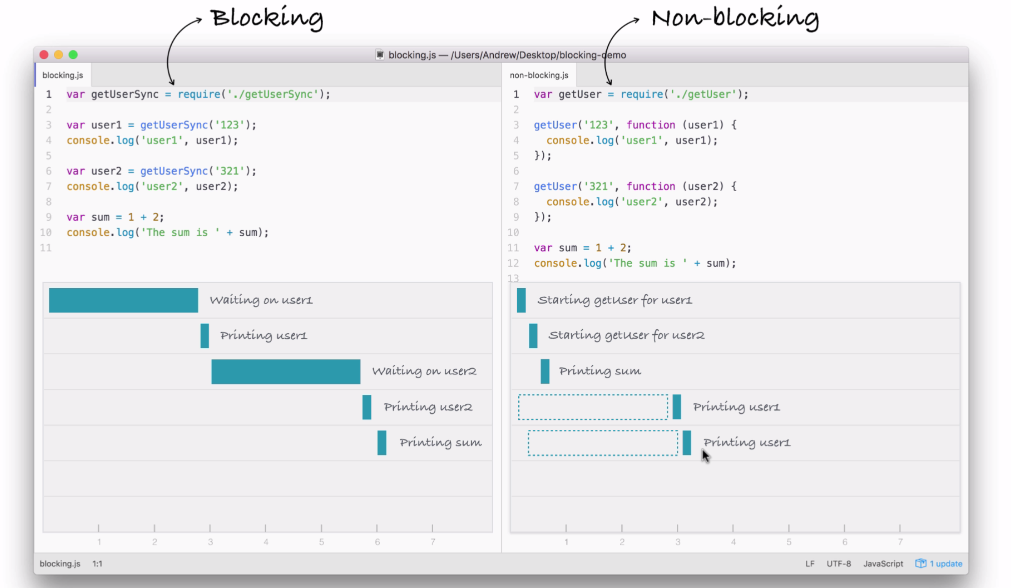

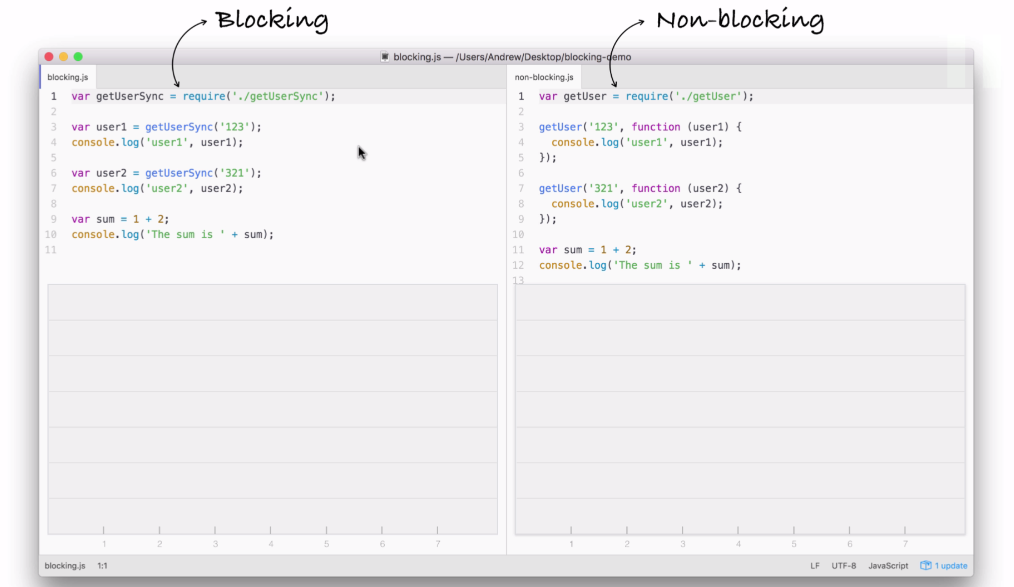

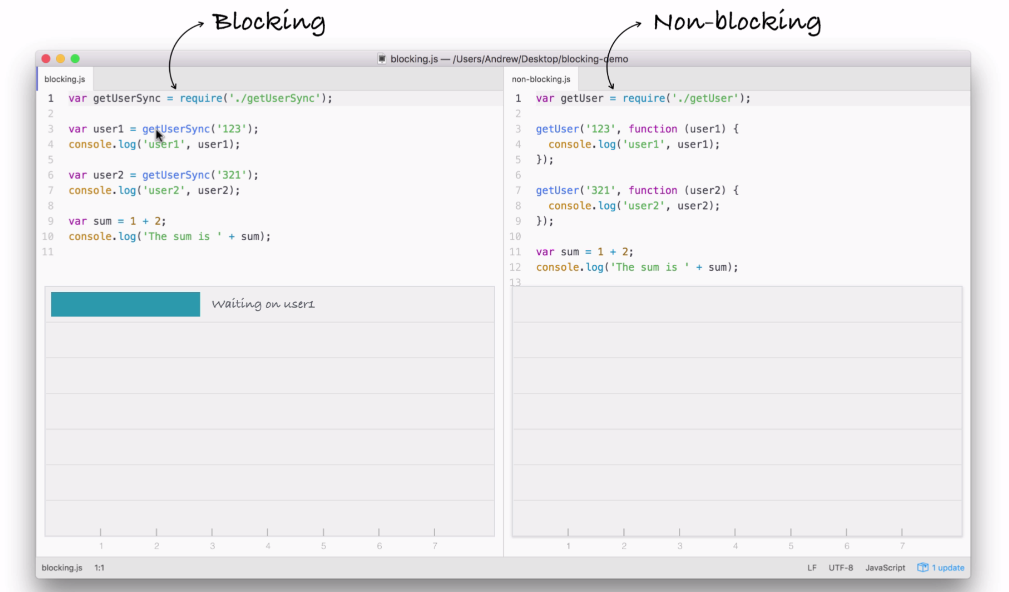

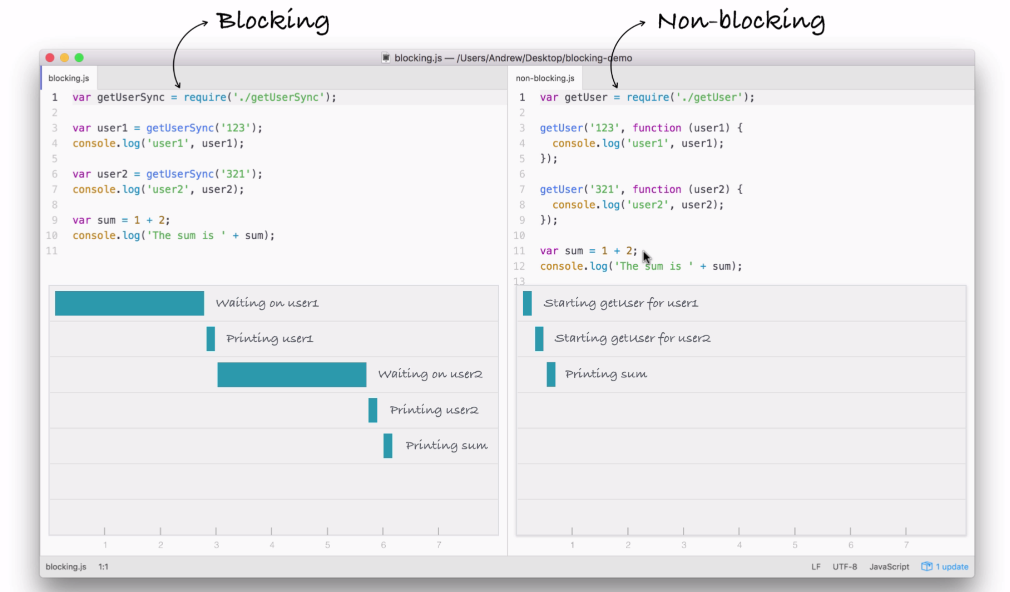

Let's go ahead and take a look at the differences between blocking and non blocking software development:

In the preceding screenshot, I have two files that we'll be executing. But before going to that, first let's explore how each of these files operates, the steps that are required in order to finish the program.

This will help us understand the big differences between blocking, which I have on the left side of the image, which is not what Node uses, and non-blocking is on the right side, which is exactly how all of our Node applications in the book are going to operate.

You don't have to understand the individual details, such as what require is, in order to understand what's going on in this code example. We'll be breaking things down in a very general sense. The first line on each code is responsible for fetching a function that gets called. This function will be our simulated I/O function that is going to a database, fetching some user data and printing it to the screen.

Refer to the preceding code image. After we load in the function, both files try to fetch a user with an ID of 123. When it gets that user, it prints it to the screen with the user1 string first, and then it goes on and it fetches the user with 321 as the ID. And it prints that to the screen. And finally both files add up 1 + 2, storing the result, which is 3, in the sum variable and print it to the screen.

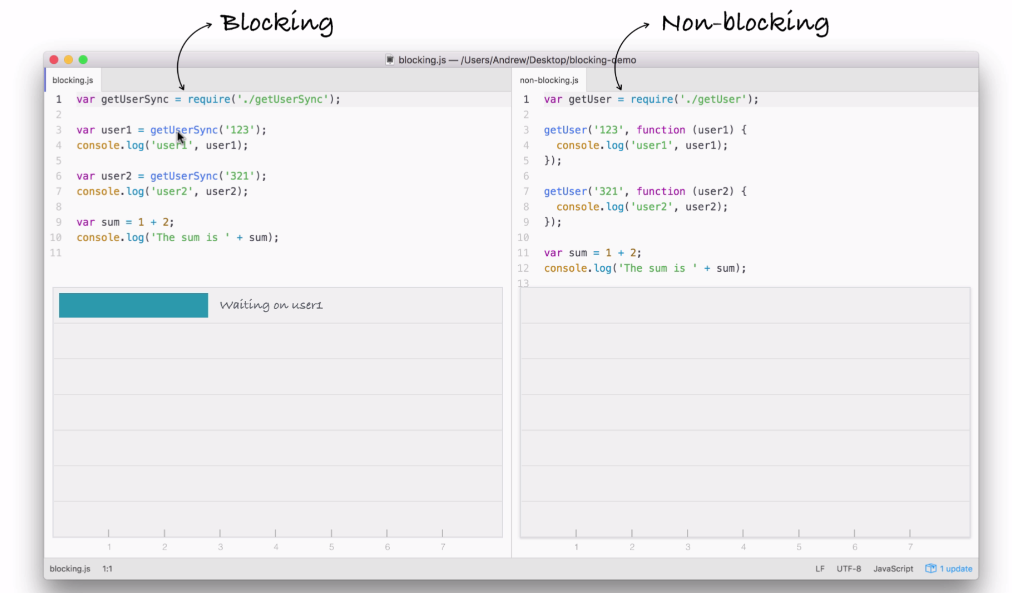

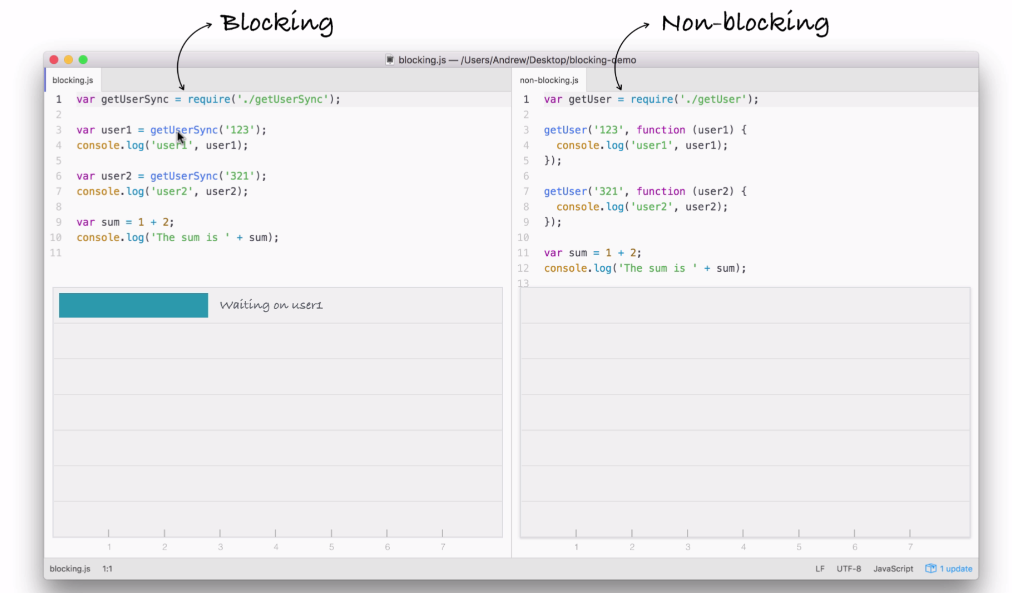

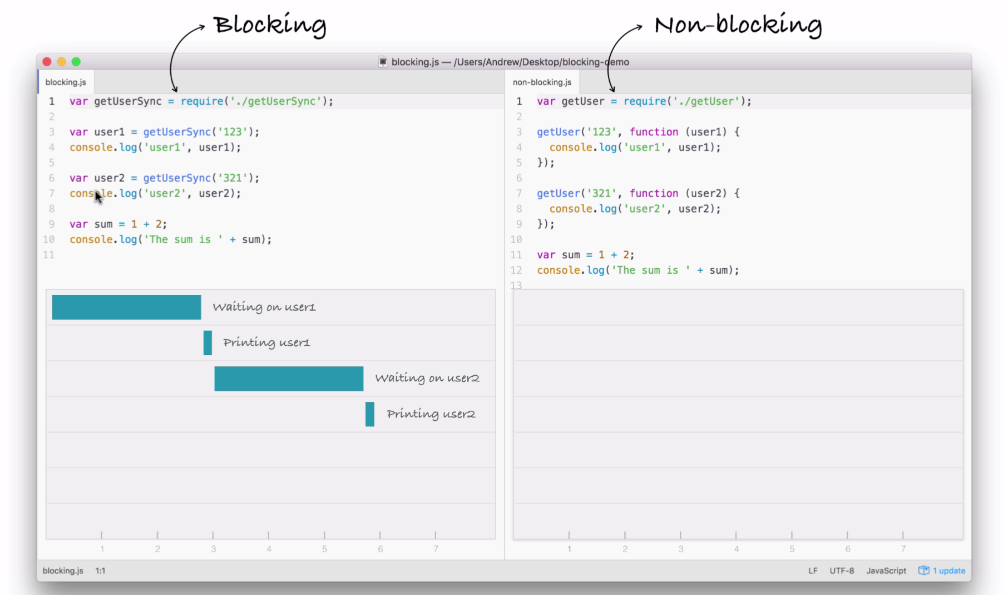

Now, while they all do the same thing, they do it in very different ways. Let's break down the individual steps. In the following code image, we'll go over what Node executes and how long it takes:

You can consider the seconds shown in the preceding screenshot; it doesn't really matter, it's just to show the relative operating speed between the two files.

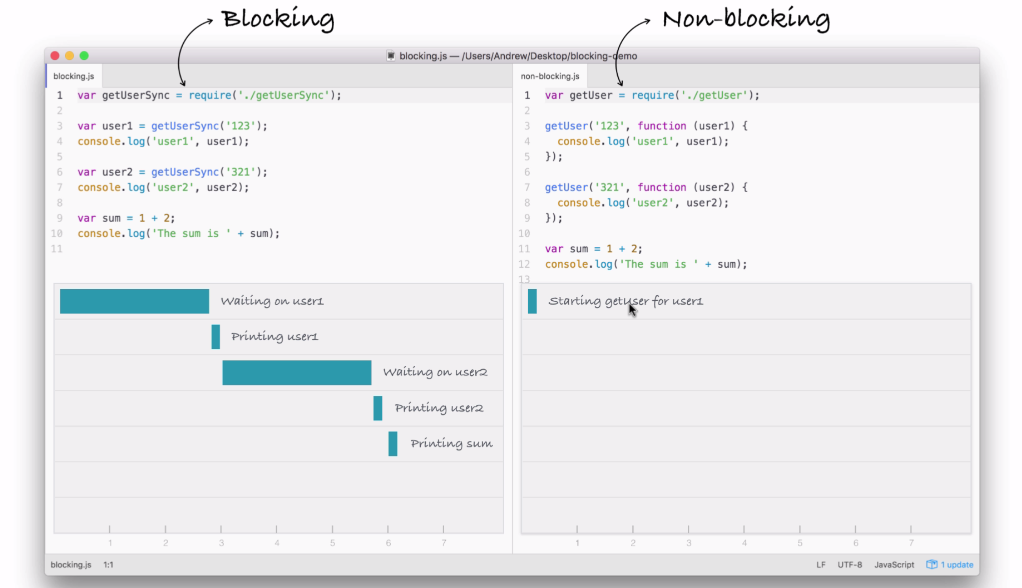

The blocking example can be illustrated as follows:

The first thing that happens inside our blocking example, as shown in the preceding screenshot, is that we fetch the user on line 3 in the code:

var user1 = getUserSync('123');

Now, this request requires us to go to a database, which is an I/O operation to fetch that user by ID. This takes a little bit of time. In our case, we'll say it takes three seconds.

Next, on line 4 in the code, we print the user to the screen, which is not an I/O operation and it runs right away, printing user1 to the screen, as shown in the following code:

console.log('user1', user1);

As you can see in the following screenshot, it takes almost no time at all:

Next up, we wait on the fetching of user2:

var user2 = getUserSync('321');

When user2 comes back, as you might expect, we print it to the screen, which is exactly what happens on line 7:

console.log('user2', user2);

Finally, we add up our numbers and we print it to the screen:

var sum = 1 + 2;

console.log('The sum is ' + sum);

None of this is I/O, so right here we have our sum printing to the screen in barely any time.

This is how blocking works. It's called blocking because while we're fetching from the database, which is an I/O operation, our application cannot do anything else. This means our machine sits around idle waiting for the database to respond, and can't even do something simple like adding two numbers and printing them to the screen. It's just not possible in a blocking system.

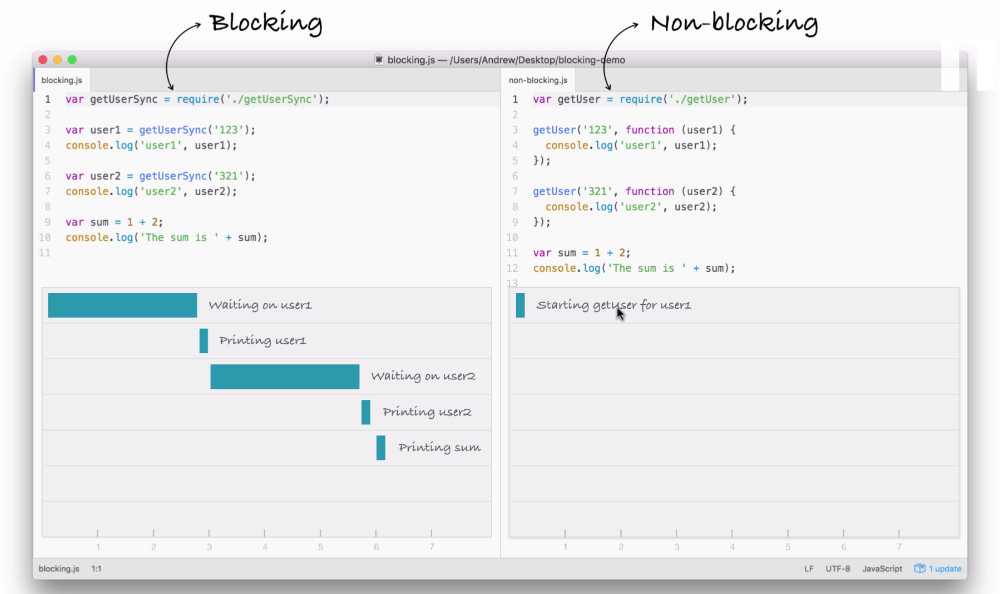

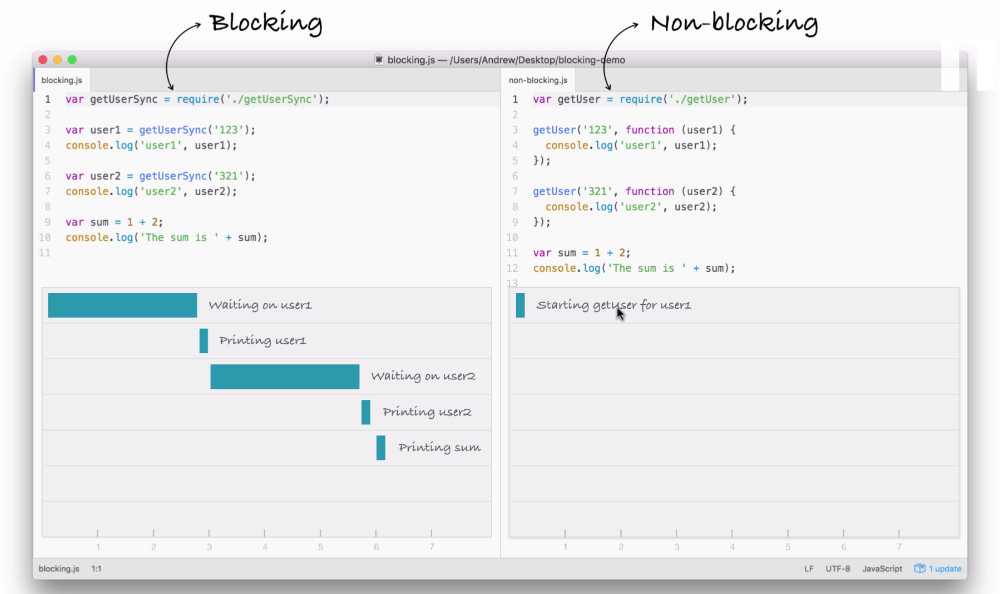

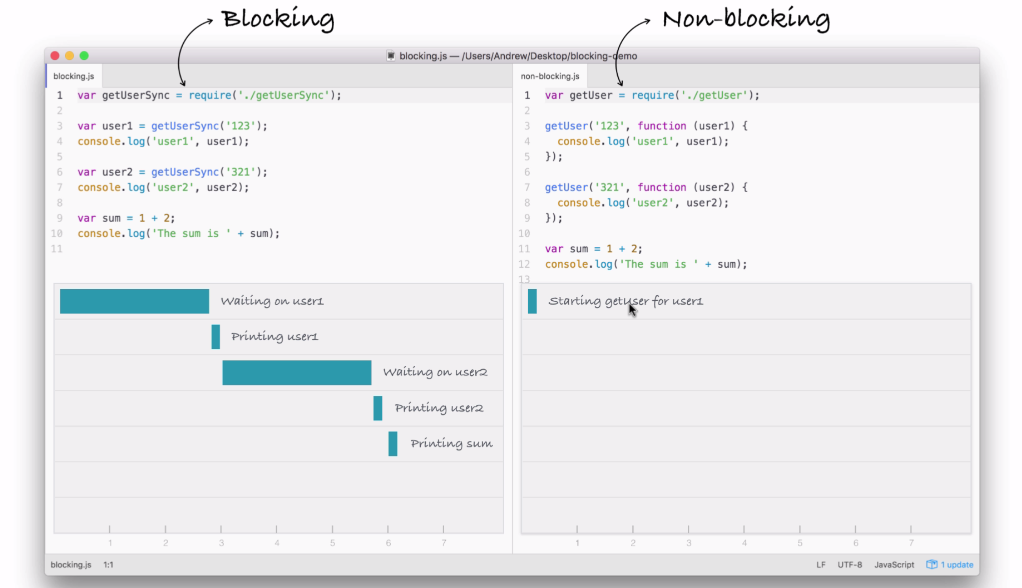

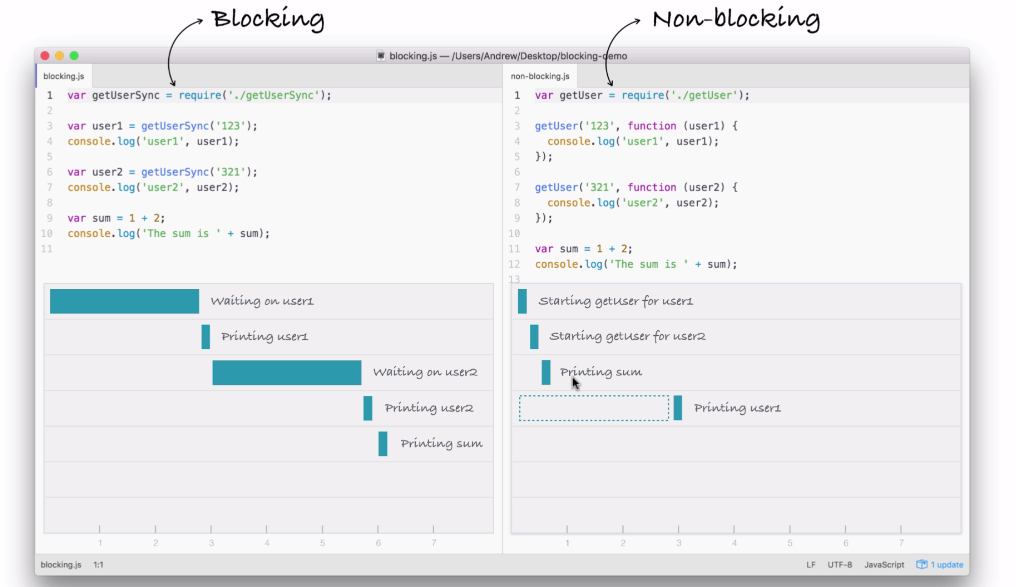

In our non-blocking example, this is how we'll be building our Node applications.

Let's break this code example down line by line. First up, things start much the same way as we discussed in the blocking example. We'll start the getUser function for user1, which is exactly what we did earlier:

But we're not waiting, we're simply kicking off that event. This is all part of the event loop inside Node.js, which is something we'll be exploring in detail.

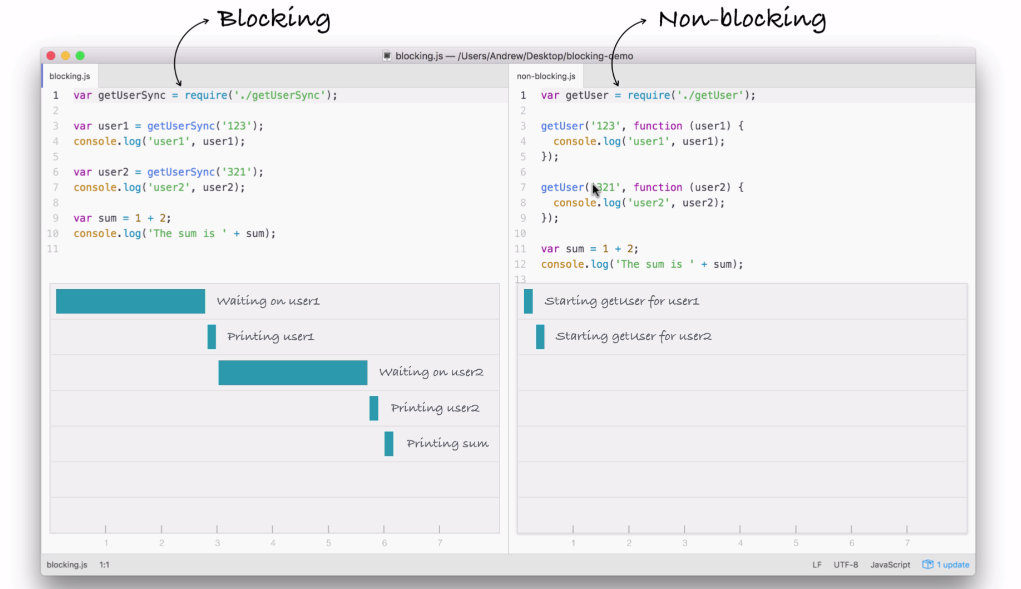

Notice it takes a little bit of time; we're just starting the request, we're not waiting for that data. The next thing we do might surprise you. We're not printing user1 to the screen because we're still waiting for that request to come back, instead we start the process of fetching our user2 with the ID of 321:

In this part of the code, we're kicking off another event, which takes just a little bit of time to do-it is not an I/O operation. Now, behind the scenes, the fetching of the database is I/O, but starting the event, calling this function is not, so it happens really quickly.

Next up, we print the sum. The sum doesn't care about either of the two user objects. They're basically unrelated, so there's no need to wait for the users to come back before I print that sum variable, as shown in the following screenshot:

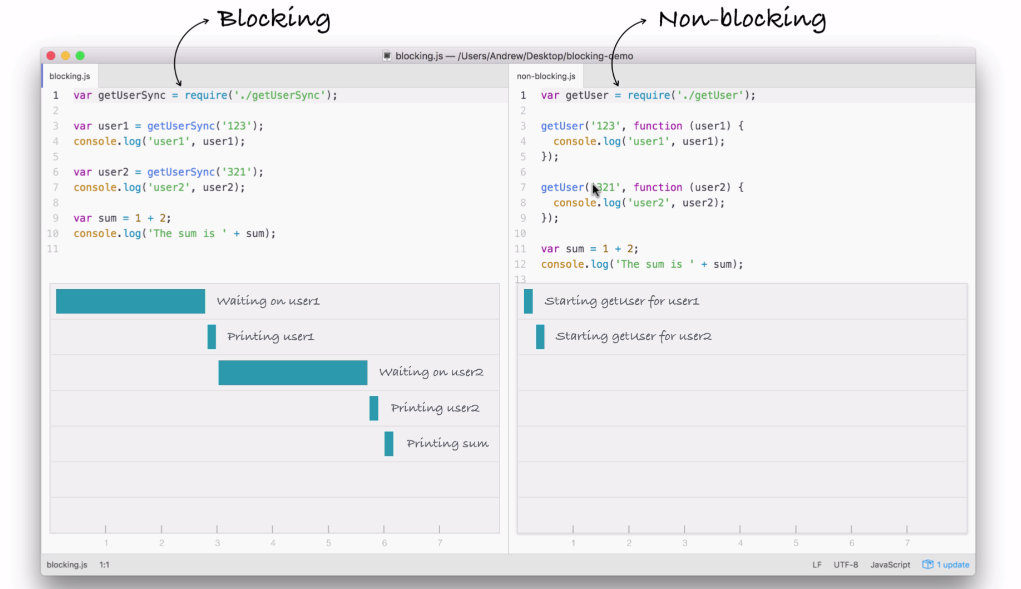

What happens after we print the sum? Well, we have the dotted box, as shown in the following screenshot:

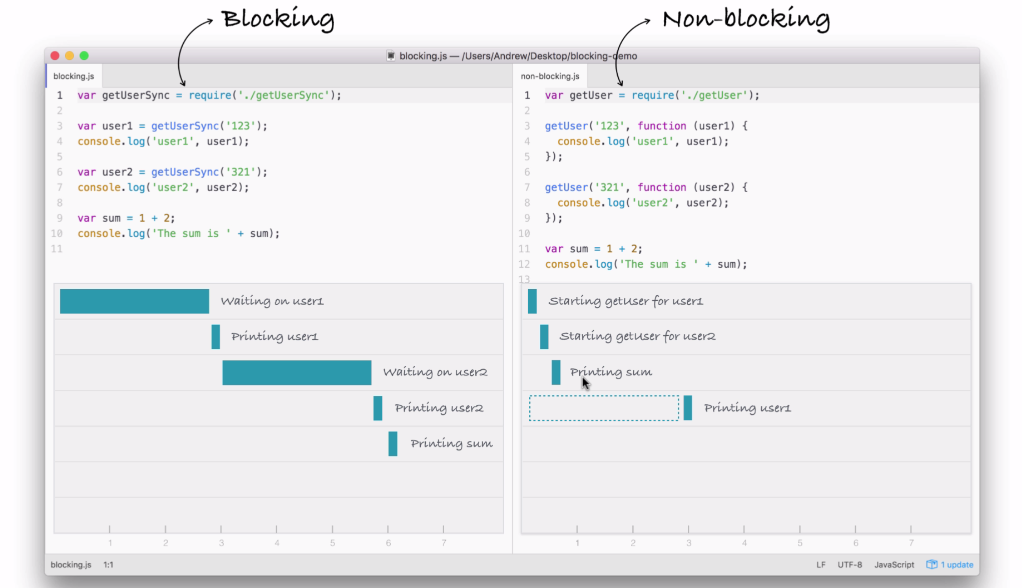

This box signifies the simulated time it takes for our event to get responded to. Now, this box is the exact same width as the box in the first part of the blocking example (waiting on user1), as shown here:

Using non-blocking doesn't make our I/O operations any faster, but what it does do is it lets us run more than one operation at the same time.

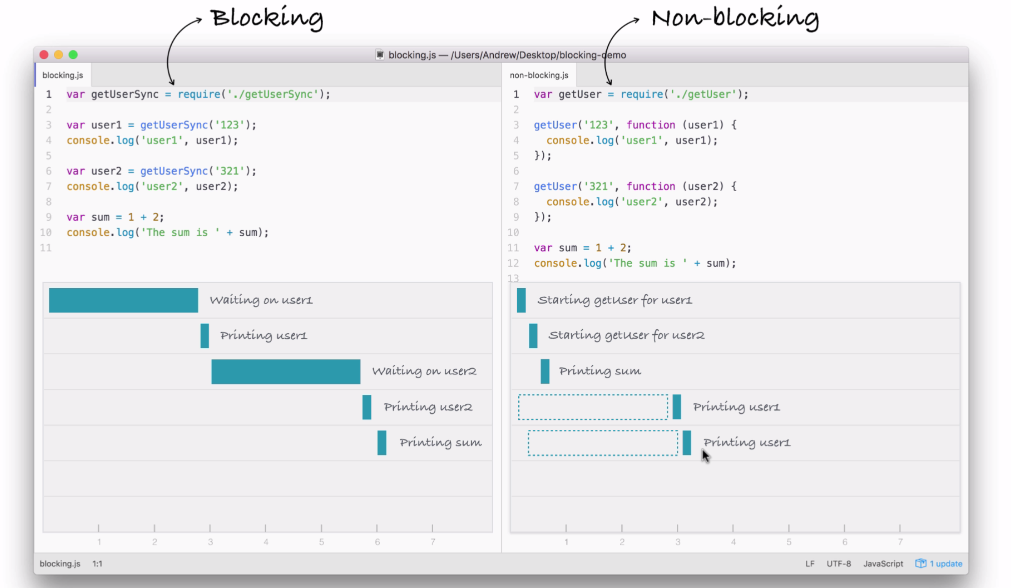

In the non-blocking example, we start two I/O operations before the half second mark, and in between three and a half seconds, both come back, as shown in the following screenshot:

Now, the result here is that the entire application finishes much quicker. If you compare the time taken in executing both the files, the non-blocking version finishes in just over three seconds, while the blocking version takes just over six seconds. A difference of 50%. This 50% comes from the fact that in blocking, we have two requests each taking three seconds, and in non-blocking, we have two requests each taking three seconds, but they run at the same time.

Using the non-blocking model, we can still do stuff like printing the sum without having to wait for our database to respond. Now, this is the big difference between the two; blocking, everything happens in order, and in non-blocking we start events, attaching callbacks, and these callbacks get fired later. We're still printing out user1 and user2, we're just doing it when the data comes back, because the data doesn't come back right away.

Inside Node.js, the event loop attaches a listener for the event to finish, in this case for that database to respond back. When it does, it calls the callback you pass in the non-blocking case, and then we print it to the screen.

In a blocking context, we could handle two requests on two separate threads, but that doesn't really scale well, because for each request we have to beef up the amount of CPU and RAM resources that we're using for the application, and this sucks because those threads, are still sitting idle. Just because we can spin up other threads doesn't mean we should, we're wasting resources that are doing nothing.

In the non-blocking case, instead of wasting resources by creating multiple threads, we're doing everything on one thread. When a request comes in, the I/O is non-blocking so we're not taking up any more resources than we would be if it never happened at all.

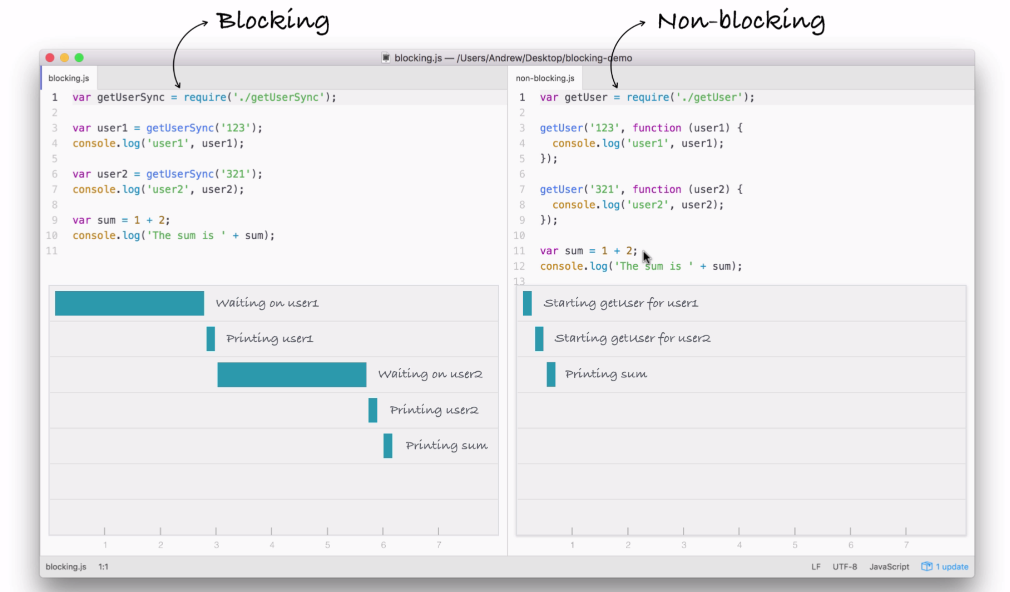

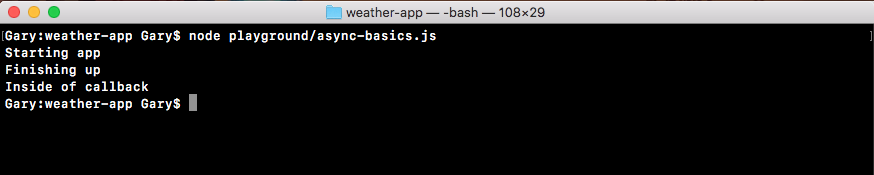

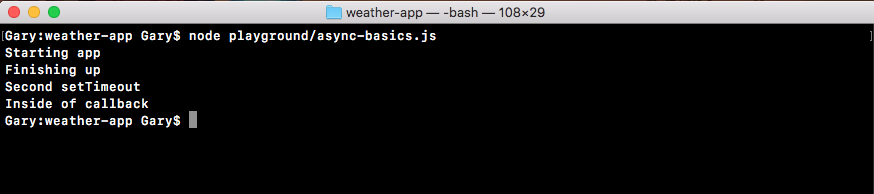

Let's run these examples in real time and see what we get. And we have the two files (blocking and non-blocking files) that we saw in the previous section.

We'll run both of these files, and I'm using the Atom editor to edit my text files. These are things we'll be setting up later in the section, this is just for your viewing purpose, you don't need to run these files.

Now, the blocking and non-blocking files, will both get run and they'll do similar things to those we did in the previous section, just in a different way. Both use I/O operations, getUserSync and getUser, that take five seconds apiece. The time is no different, it's just the order they execute in that makes the non-blocking version much quicker.

Now, to simulate and show how things work, I'll add a few console.log statements as shown in the following code example, console.log('starting user1'), console.log('starting user2').

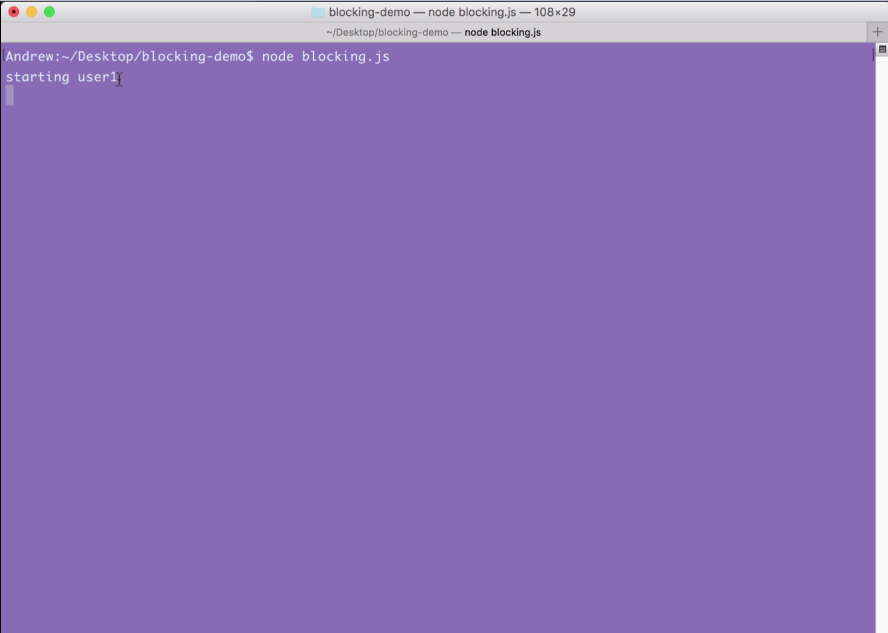

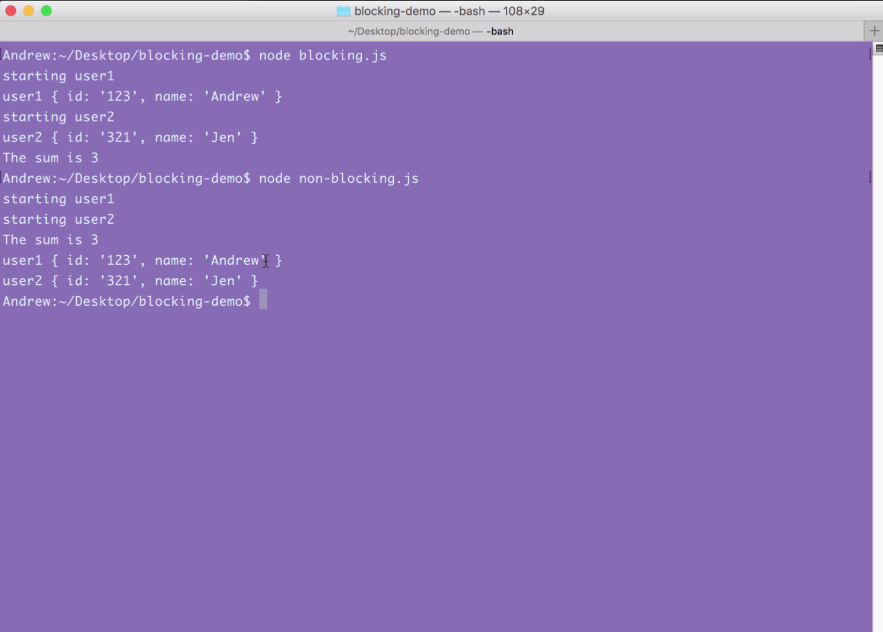

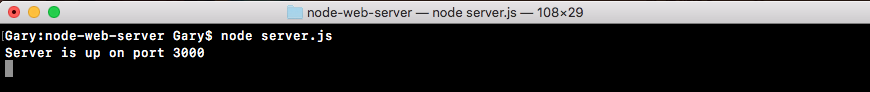

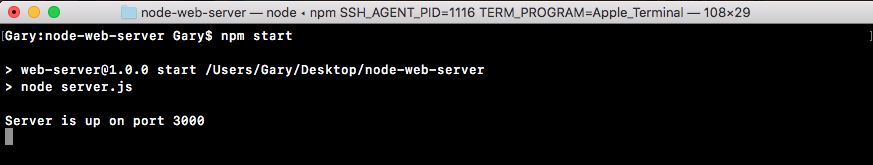

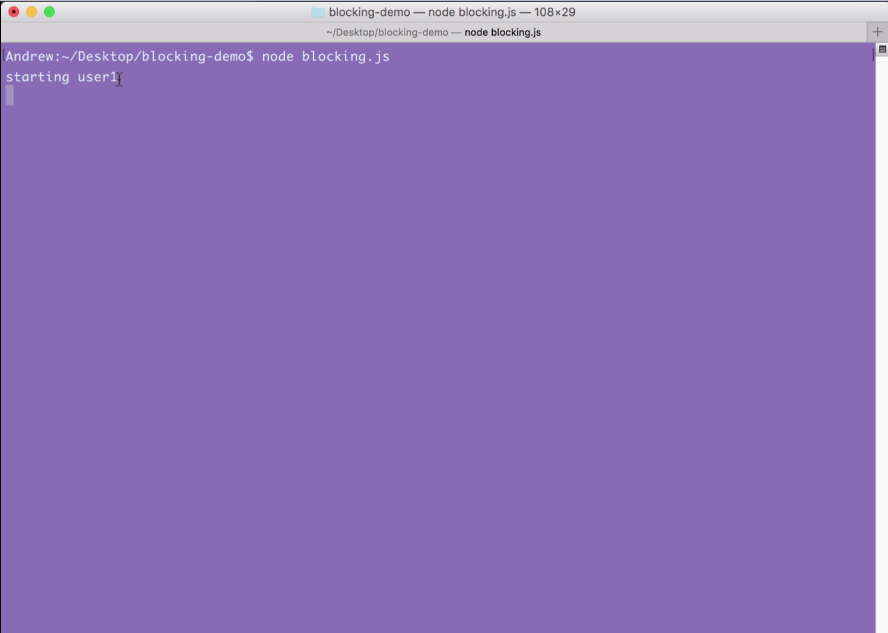

This will let us visualize how things work inside Terminal. By running node blocking.js, this is how we run files. We type node and we specify the filename, as shown in the following code:

node blocking.js

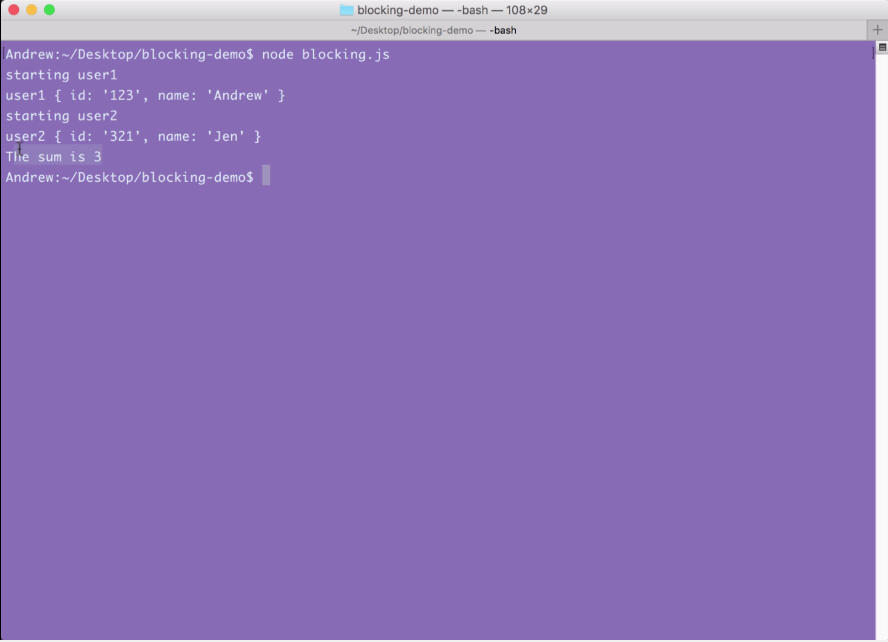

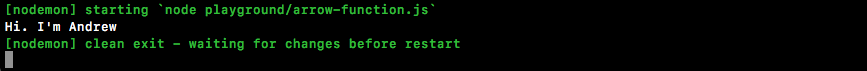

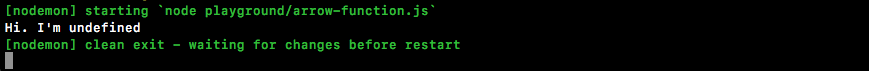

When I run the file, we get some output. starting user1 prints to the screen and then it sits there:

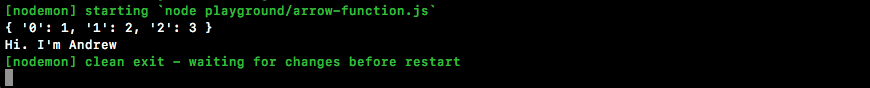

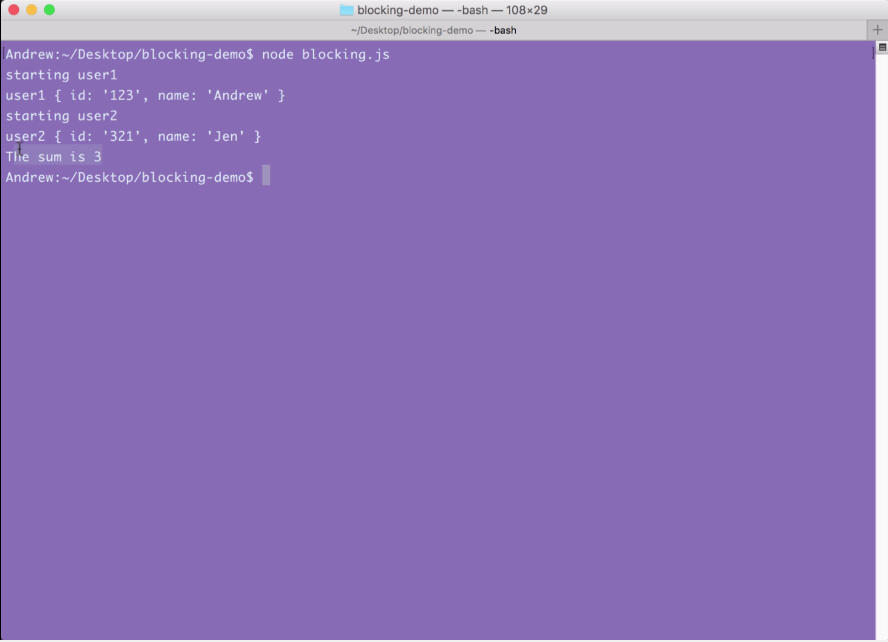

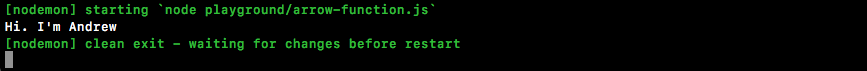

Now, we have the user1 object printing to the screen with the name Andrew, and starting user2 prints to the screen, as shown in the following code output:

After that, the user2 object comes back around five seconds later with the name of Jen.

As shown in the preceding screenshot, our two users have printed to the screen, and at the very end our sum, which is 3, prints to the screen; everything works great.

Notice that starting user1 was immediately followed by the finishing of user1, and starting user2 was immediately followed by the finishing of user2 because this is a blocking application.

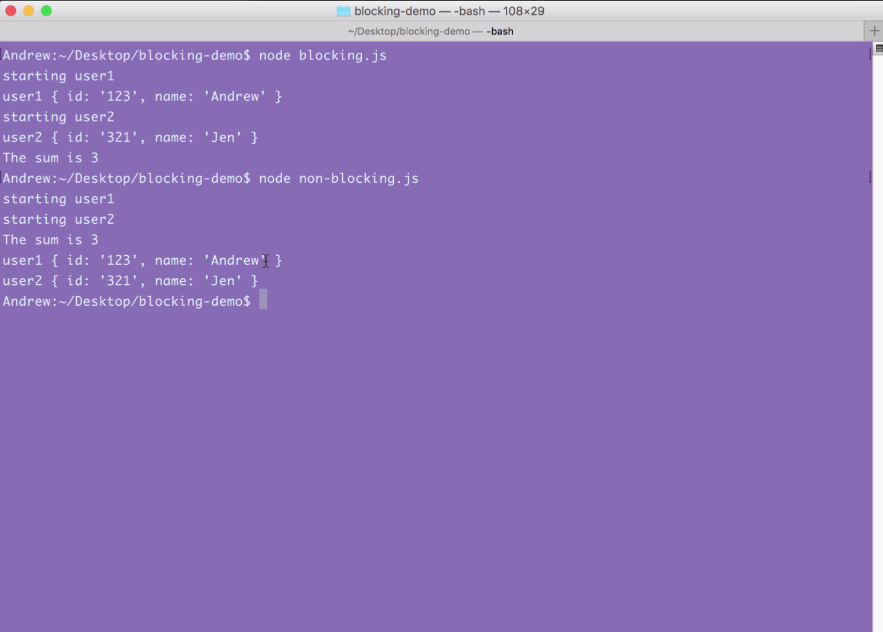

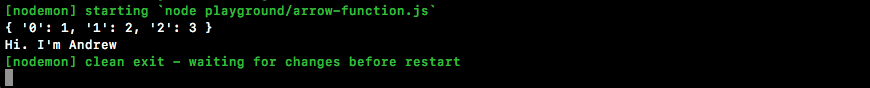

Now, we'll run the non-blocking file, which I've called non-blocking.js. When I run this file, starting user1 prints, starting user2 prints, then the sum prints all back to back:

Around 5 seconds later, at basically the same time, user1 and user2 both print to the screen.

This is how non-blocking works. Just because we started an I/O operation doesn't mean we can't do other things, such as starting another one and printing some data to the screen, in this case just a number. This is the big difference, and this is what makes non-blocking apps so fantastic. They can do so many things at the exact same time without having to worry about the confusion of multi-threading applications.

Let's move back into the browser and take a look at those sentences again in the Node website:

Node.js uses an event-driven, non-blocking I/O model that makes it lightweight and efficient, and we saw that in action.

Because Node is non-blocking, we were able to cut down the time our application took by half. This non-blocking I/O makes our apps super quick, this is where the lightweight and efficient comes into play.

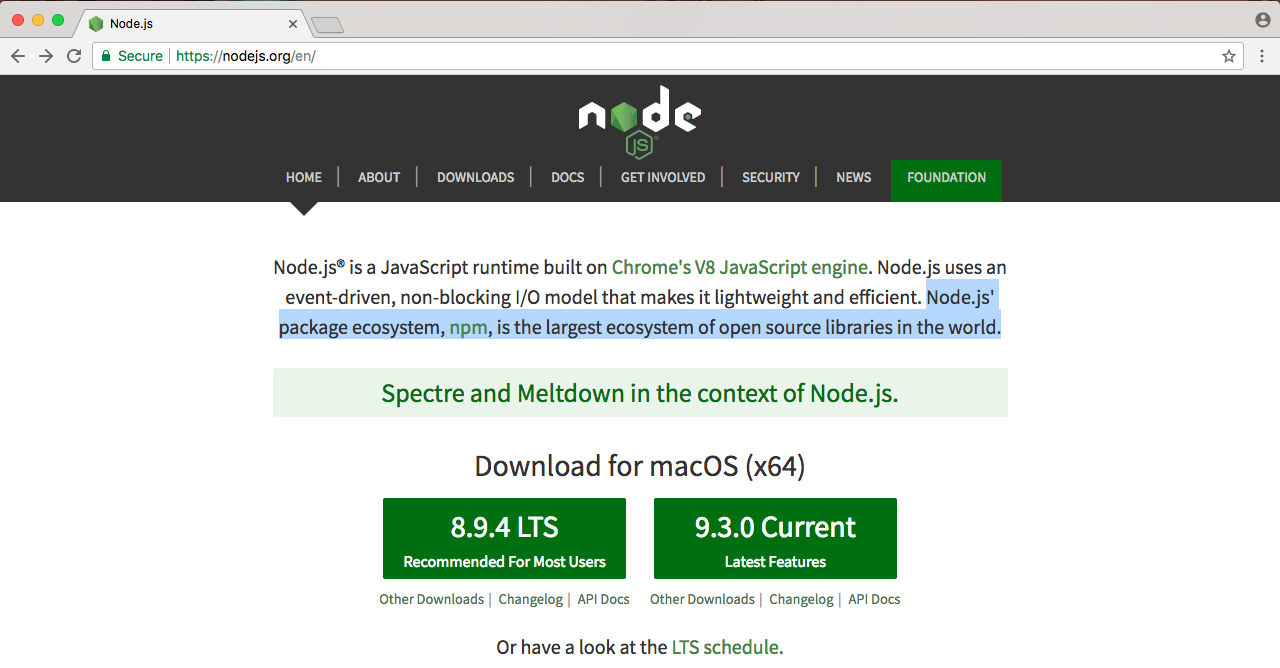

Now, let's go to the last sentence on the Node website, as shown in the following screenshot:

Node.js' package ecosystem, npm, is the largest ecosystem of open-source libraries in the world. This is what really makes Node fantastic. This is the cherry on top-the community, the people every day developing new libraries that solve common problems in your Node.js applications.

Things such as validating objects, creating servers, and serving up content live using sockets. There's libraries already built for all of those so you don't have to worry about this. This means that you can focus on the specific things related to your application without having to create all this infrastructure before you can even write real code, code that does something specific to your apps use case.

Now, npm, which is available on npmjs.org, is the site we'll be turning to for a lot of third-party modules:

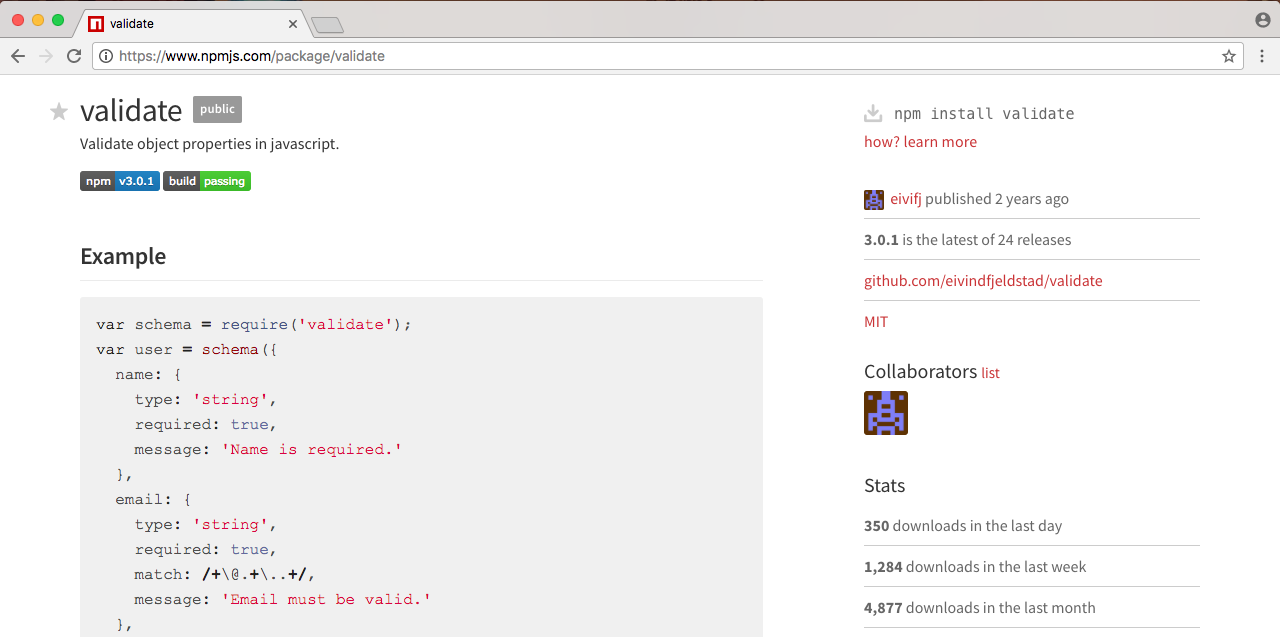

If you're trying to solve a problem in Node that sounds generic, chances are that someone's already solved it. For example, if I want to validate some objects, let's say I want to validate that a name property exists and that there's an ID with a length of three. I could go into Google or go into npm; I usually choose Google, and I could Google search npm validate object.

When I google that, I'll just look for results from npmjs.com, and you can find the first three or so are from that:

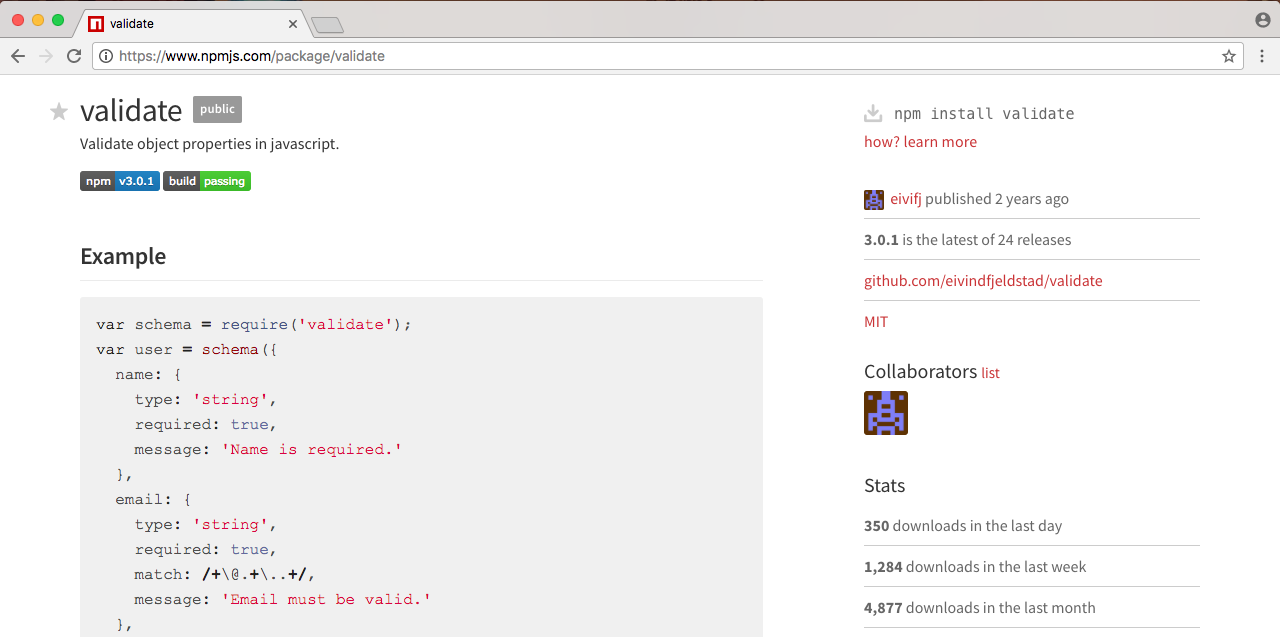

I can click the first one, and this will let me explore the documentation and see if it's right for me:

This one looks great, so I can add it to my app without any effort.

Now, we'll go through this process. Don't worry, I'm not going to leave you high and dry on how to add third-party modules. We'll be using a ton of them in the book because this is what real Node developers do. They take advantage of the fantastic community of developers, and that's the last thing that makes Node so great.

This is why Node has come to the position of power that it currently sits at, because it's non-blocking, meaning it's great for I/O applications, and it has a fantastic community of developers. So, if you ever want to get anything done, there's a chance someone already wrote the code to do it.

This is not to say you should never use Rails or Python or any other blocking language again, that is not what I'm getting at. What I'm really trying to show you is the power of Node.js and how you can make your applications even better. Languages like Python have things such as the library Twisted, which aims to add non-blocking features to Python. Though the big problem is all of the third-party libraries, as they are still written in a blocking fashion, so you're really limited as to which libraries you can use.

Since Node was built non-blocking from the ground up, every single library on npmjs.com is non-blocking. So you don't have to worry about finding one that's non blocking versus blocking; you can install a module knowing it was built from the ground up using a non blocking ideology.

In the next couple of sections, you'll be writing your very first app and running it from Terminal.

In this section, I want to give you a tour of the various text editors you can use for this book. If you already have one you love using, you can keep using the one you have. There's no need to switch editors to get anything done in this book.

Now, if you don't have one and you're looking for a few options, I always recommend using Atom, which you can find at atom.io. It's free, open source, and it's available on all operating systems, Linux, macOS, and Windows. It's created by the folks behind GitHub and it's the editor that I'll be using inside of this book. There's an awesome community of theme and plug-in developers so you really can customize it to your liking.

Now, aside from Atom there are a few other options. I've heard a lot of people talking about Visual Studio Code. It is also open source, free, and available on all operating systems. If you don't like Atom, I highly recommend you check this out, because I've heard so many good things by word of mouth.

Next up, we always have Sublime Text, which you can find at sublimetext.com. Now, Sublime Text is not free and it's not open source, but it's a text editor that a lot of folks do enjoy using. I prefer Atom because it's very similar to Sublime Text, though I find it snappier and easier to use, plus it's free and open source.

Now, if you are looking for a more premium editor with all of the bells and whistles in IDE as opposed to a text editor, I always recommend JetBrains. None of their products are free, though they do come with a 30-day free trial, but they really are the best tools of the trade. If you find yourself in a corporate setting or you're at a job where the company is willing to pay for an editor, I always recommend that you go with JetBrains. All of their editors come with all of the tools you'd expect, such as version control integration, debugging tools, and deploying tools built in.

So, take a moment, download the one you want to use, play around with it, make sure it fits your needs, and if not, try another one.

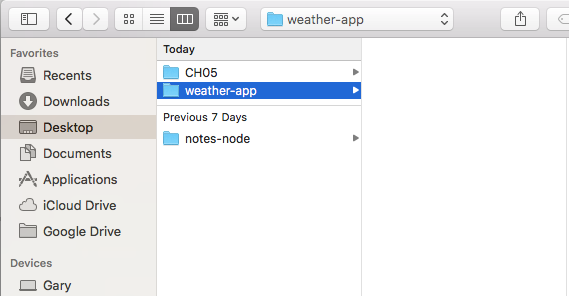

In this section, you will be creating and running your very first Node app. Well, it will be a simple one. It'll demonstrate the entire process, from creating files to running them from Terminal.

The first step will be to create a folder. Every project we create will go live inside of its own folder. I'll open up the Finder on macOS and navigate to my desktop. What I'd like you to do is open up the desktop on your OS, whether you're on Linux, Windows, or macOS, and create a brand new folder called hello-world.

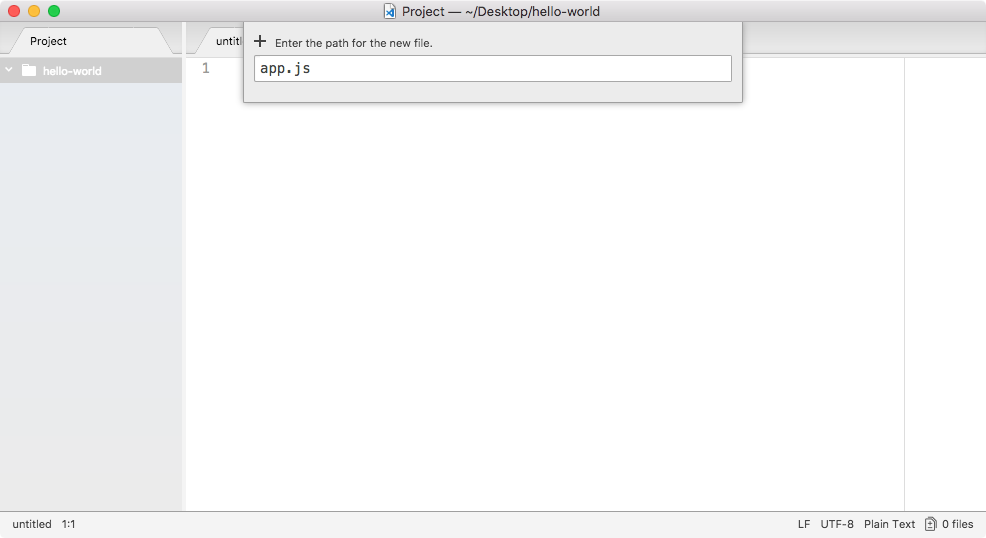

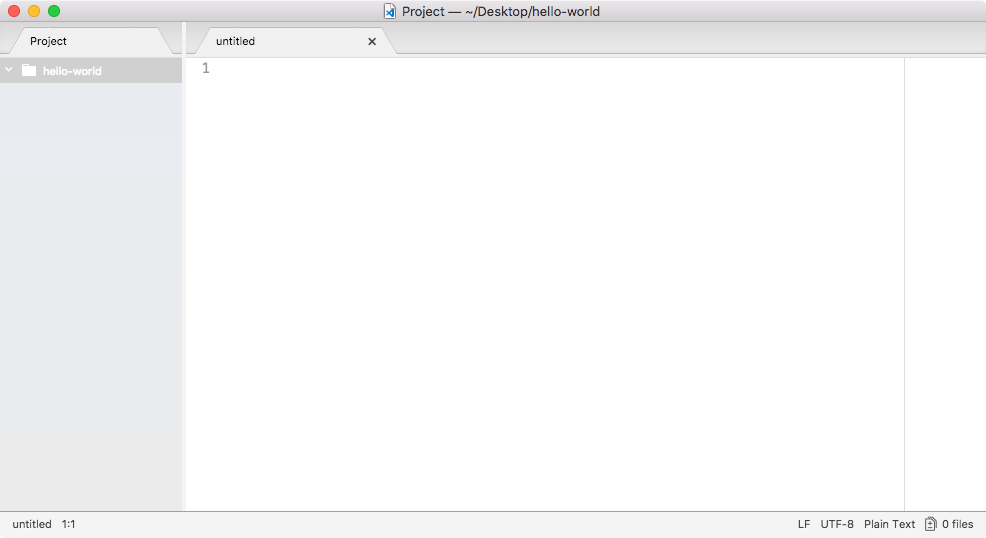

Now I'll use command + O (Ctrl + O for Windows users) to open up, and I'll navigate to the desktop and double-click my hello-world folder, as shown here:

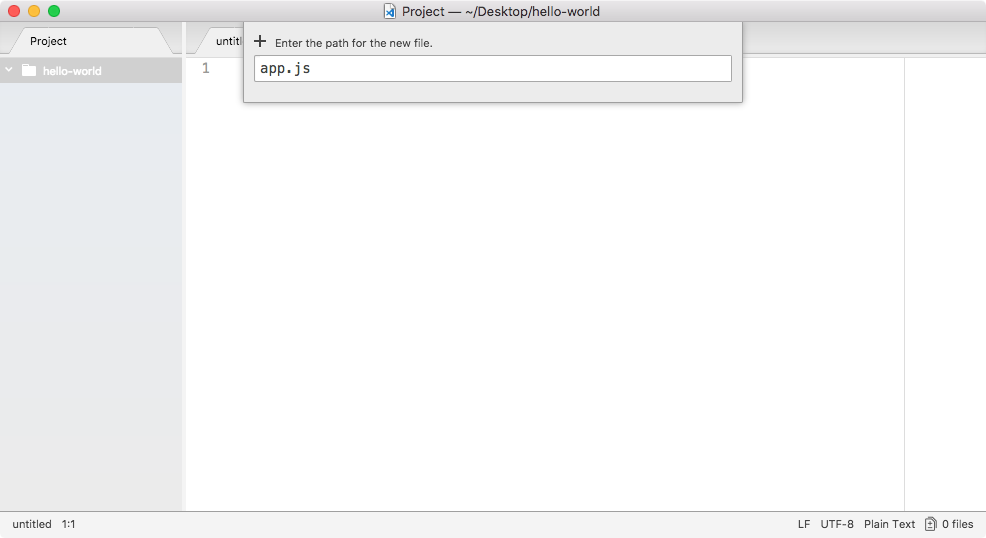

On the left I have my files, which are none. So, let's create a new one. I'll make a new file in the root of the project, and we'll call this one app.js, as shown here:

This will be the only file we have inside our Node application, and in this file we can write some code that will get executed when we start the app.

In the future, we'll be doing crazy stuff like initializing databases and starting web servers, but for now we'll simply use console.log, which means we're accessing the log property on the console object. It's a function, so we can call it with parentheses, and we'll pass in one argument as string, Hello world!. I'll toss a semicolon on the end and save the file, as shown in the following code:

console.log('Hello world!');

This will be the first app we run.

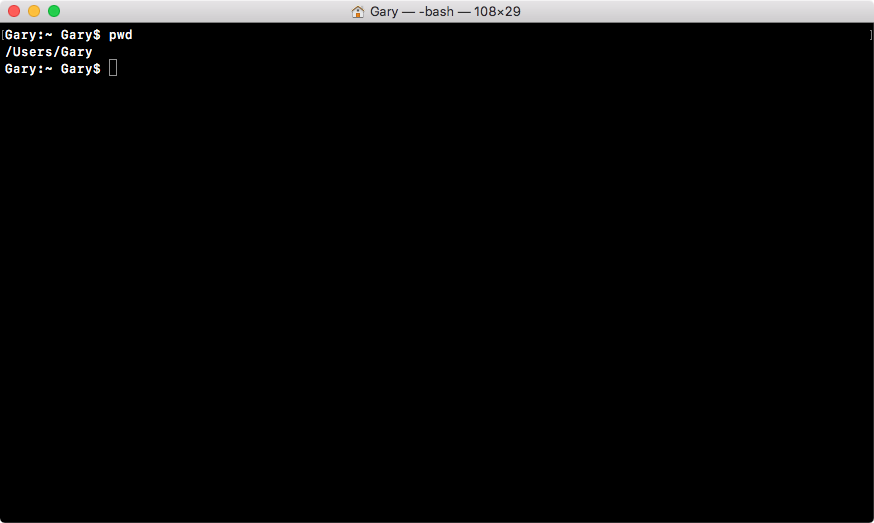

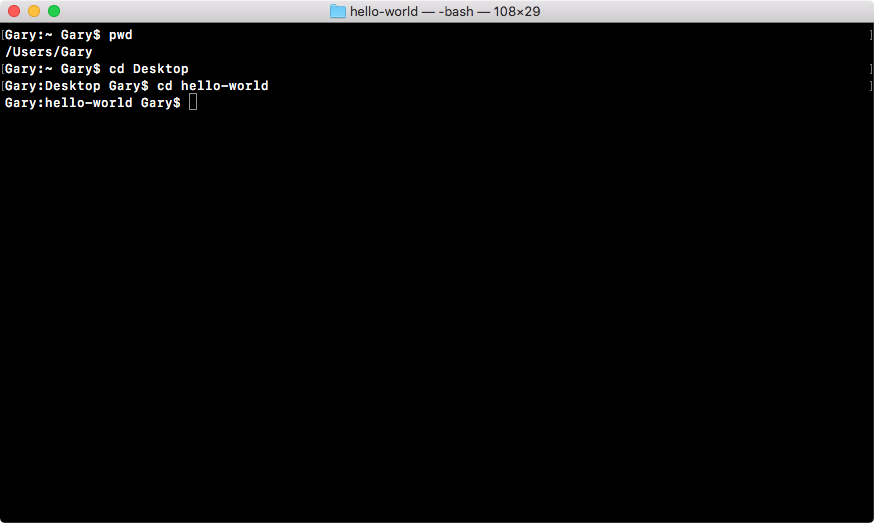

Now that we have our app.js file, the only thing left to do is to run it, and we'll do that over in Terminal. Now, to run this program, we have to navigate into our project folder. If you're not familiar with Terminal, I'll give you a quick refresher.

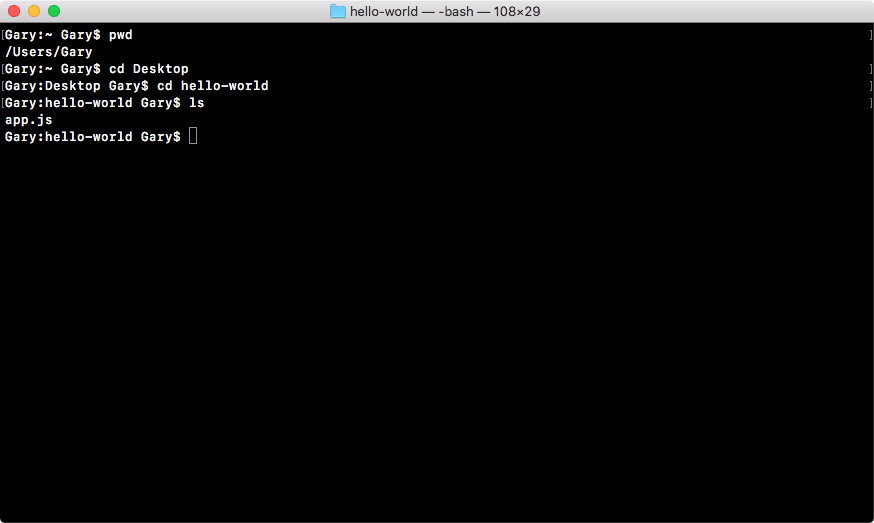

You can always figure out where you are using pwd on Linux or macOS, or the dir command on Windows. When you run it, you'll see something similar to the following screenshot:

I'm in the Users folder, and then I'm in my user folder, and my user name happens to be Gary.

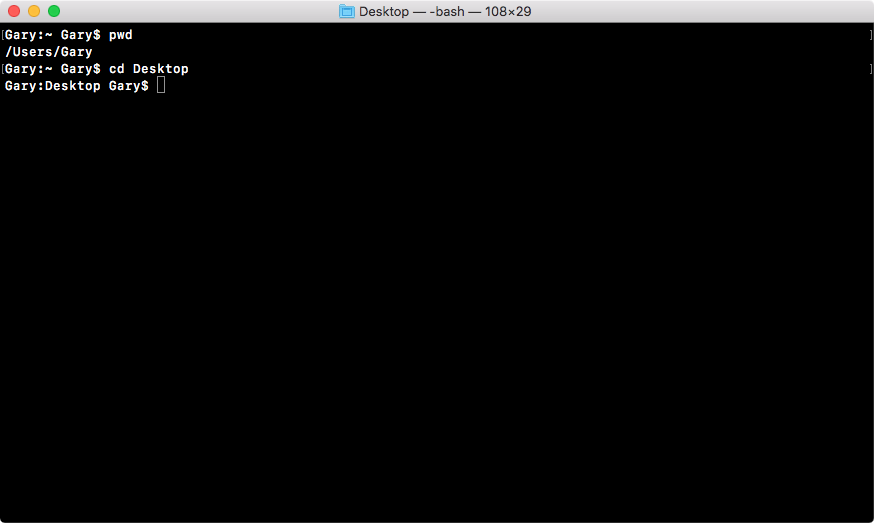

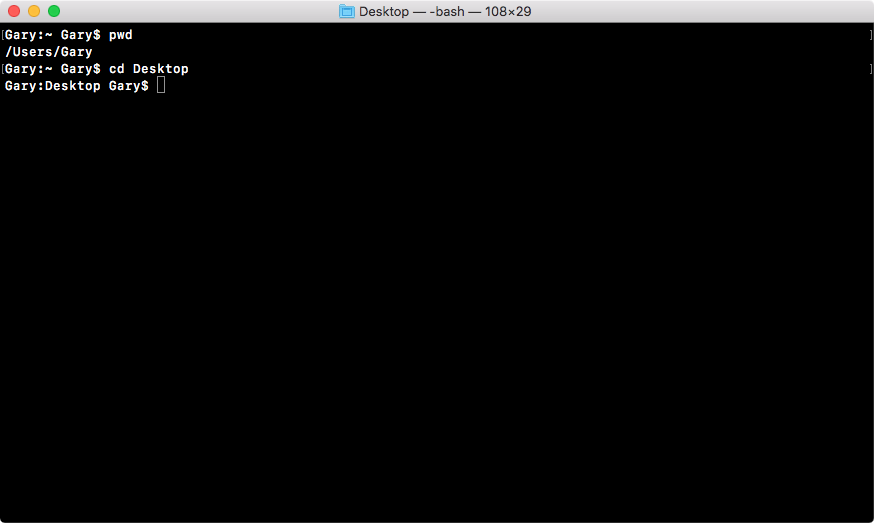

We can use cd to navigate into the desktop, and here we are:

Now we're sitting in the desktop. The other command you can run from anywhere on your computer is cd /users/Gary/desktop. And this will navigate to your desktop, no matter what folder you're located in. The command cd desktop, requires you to be in the user directory to work correctly.

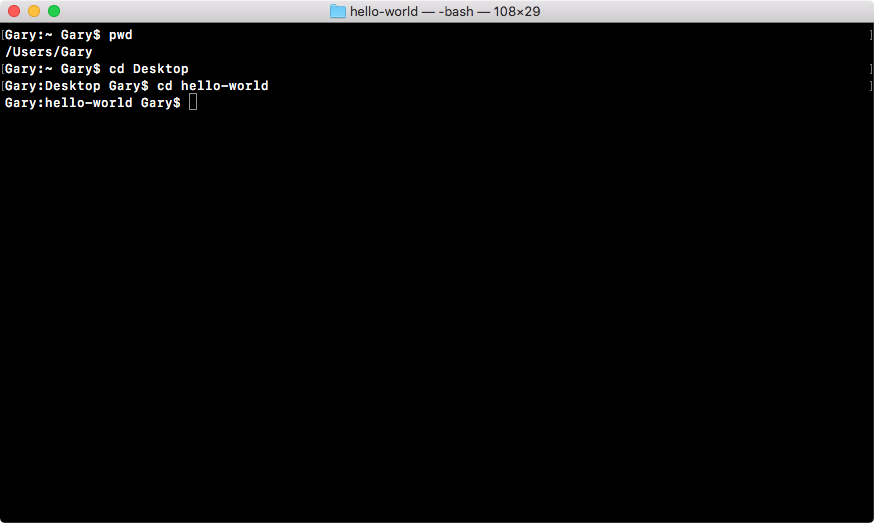

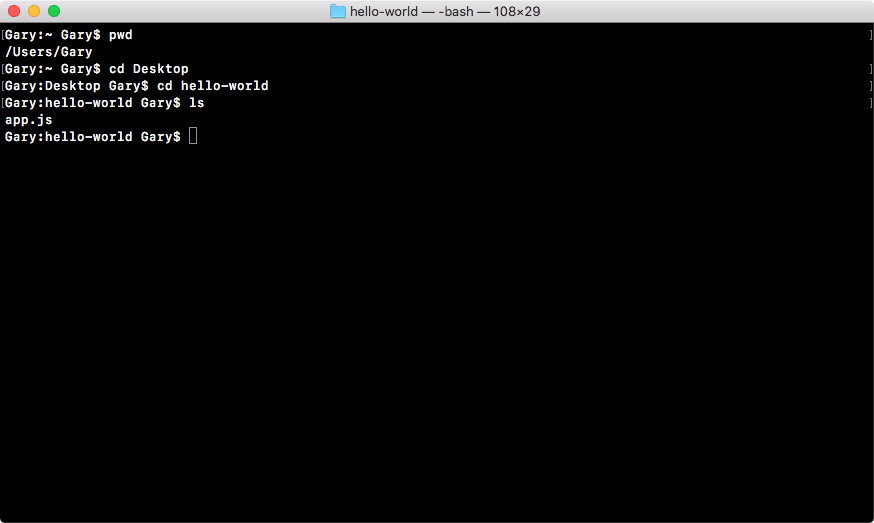

Now we can start by cd-ing into our project directory, which we called hello-world, as shown in the following command:

cd hello-world

With the following screenshot:

Once we're in this directory, we can run at the ls command on Linux or Mac (which is the dir command on Windows) to see all of our files, and in this case we just have one, we have app.js:

This is the file we'll run.

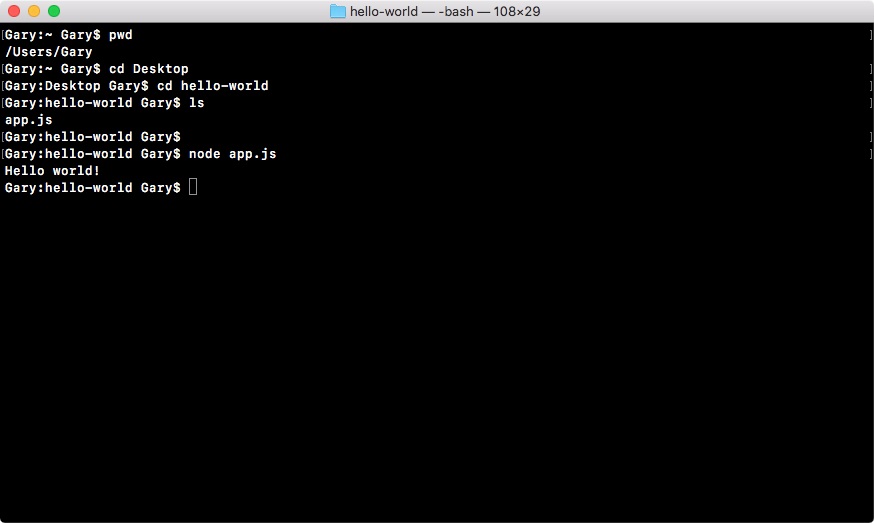

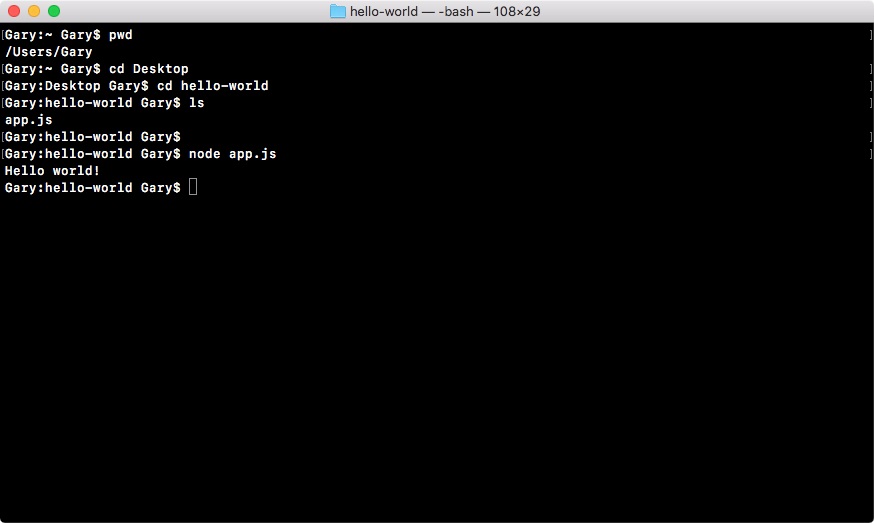

Now, before you do anything else, make sure you are in the hello-world folder and you should have the app.js file inside. If you do, all we'll do is run the node command followed by a space so we can pass in an argument, and that argument will be the filename, app.js as shown here:

node app.js

Once you have this in place, hit enter and there we go, Hello world! prints to the screen, as shown here:

And that is all it takes to create and run a very basic Node application. While our app doesn't do anything cool, we'll be using this process of creating folders/files and running them from Terminal throughout the book, so it's a great start on our way to making real-world Node apps.

In this chapter, we touched base with the concept of Node.js. We took a look at what Node is and we learned that it's built on top of the V8 JavaScript engine. Then we explored why Node has become so popular, its advantages and its disadvantages. We took a look at the different text editors we can choose from and, at the end, you created your very first Node application.

In the next chapter, we'll dive in and create our first app. I am really excited to start writing real-world applications.

In this chapter, you'll learn a ton about building Node applications, and you'll actually build your first Node application. This is where all the really fun stuff is going to start.

We'll kick things off by learning about all of the modules that come built in to Node. These are objects and functions that let you do stuff with JavaScript you've never been able to do before. We'll learn how to do things, such as reading and writing from the filesystem, which we'll use in the Node's application to persist our data.

We'll also be looking at third-party npm modules; this is a big part of the reason that Node became so popular. The npm modules give you a great collection of third-party libraries you can use, and they also have really common problems. So you don't have to rewrite that boilerplate code over and over again. We'll be using a third-party module in this chapter to help with fetching input from the user.

The chapter will specifically cover the following topics:

In this section, you will finally learn some Node.js code, and we'll kick things off by talking about modules inside Node. Modules are units of functionality, so imagine I create a few functions that do something similar, such as a few functions that help with math problems, for example, add, subtract, and divide. I could bundle those up as a module, call it Andrew-math, and other people could take advantage of it.

Now, we'll not be looking at how to make our own module; in fact, we will be looking at how we can use modules, and that will be done using a function in Node, called require(). The require() function will let us do three things:

If you have all of your code in one file, it will be really hard to test, maintain, and update. Now, require() isn't that bad. In this section, we'll explore the first use case for require().

We'll take a look at two built-in modules; we'll figure out how to require them and how to use them, and then we'll move on to starting the process of building that Node application.

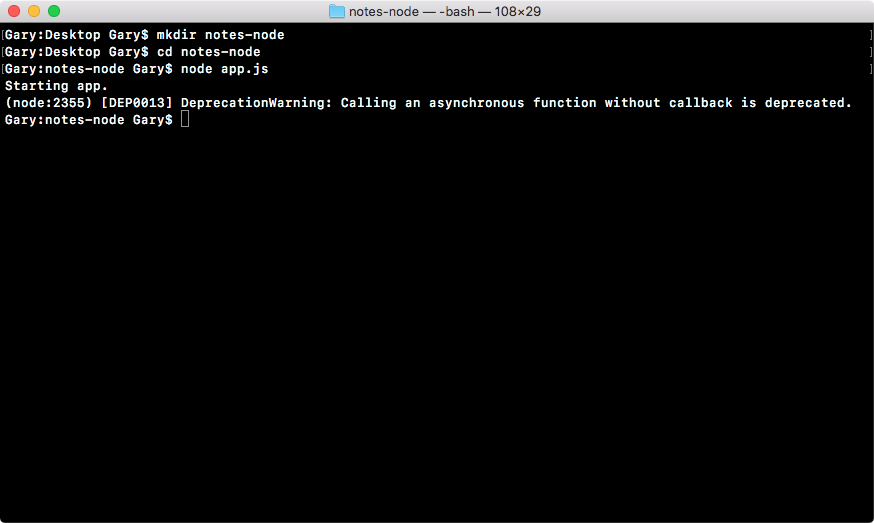

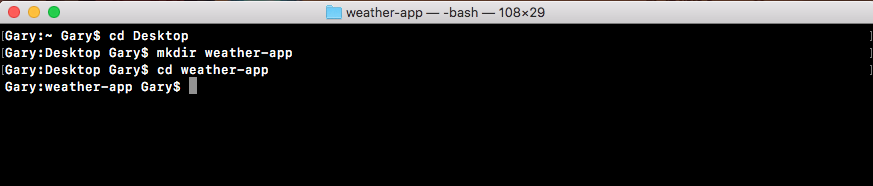

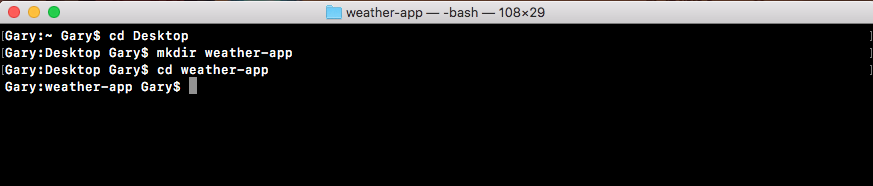

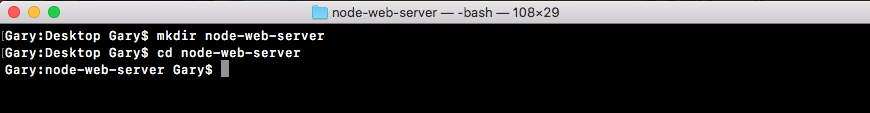

The first step we'll take inside of the Terminal is that we'll make a directory to store all of these files. We'll navigate from our home directory to the desktop using the cd Desktop command:

cd Desktop

Then, we'll make a folder to store all of the lesson files for this project.

Now, we'll make that folder using the mkdir command, which is the short form for make directory. Let's call the folder notes-node, as shown in the following code:

mkdir notes-node

We'll make a note app in Node so that notes-node seems appropriate. Then we'll cd into notes-node, and we can get started playing around with some of the built-in modules:

cd notes-node

These modules are built in, so there's no need to install anything in Terminal. We can simply require them right inside of our Node files.

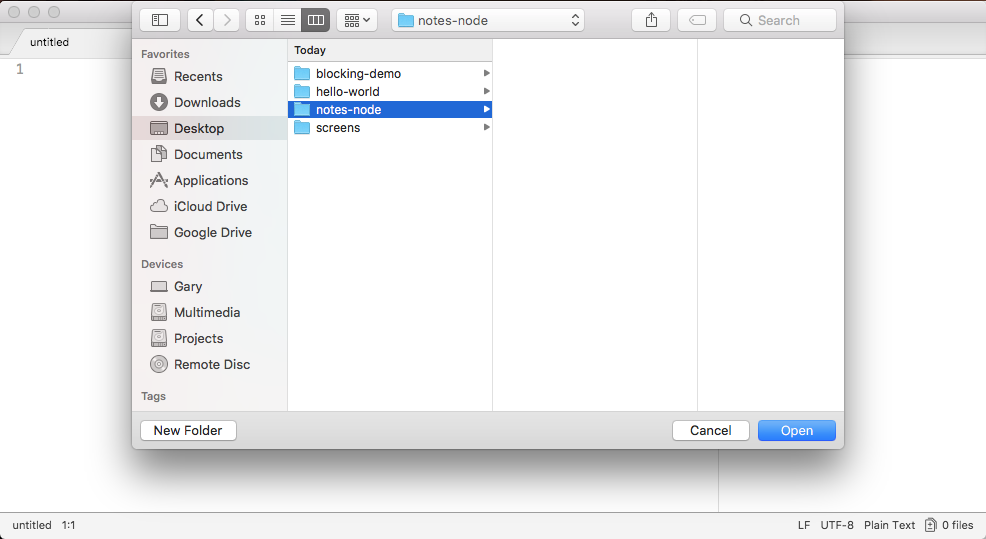

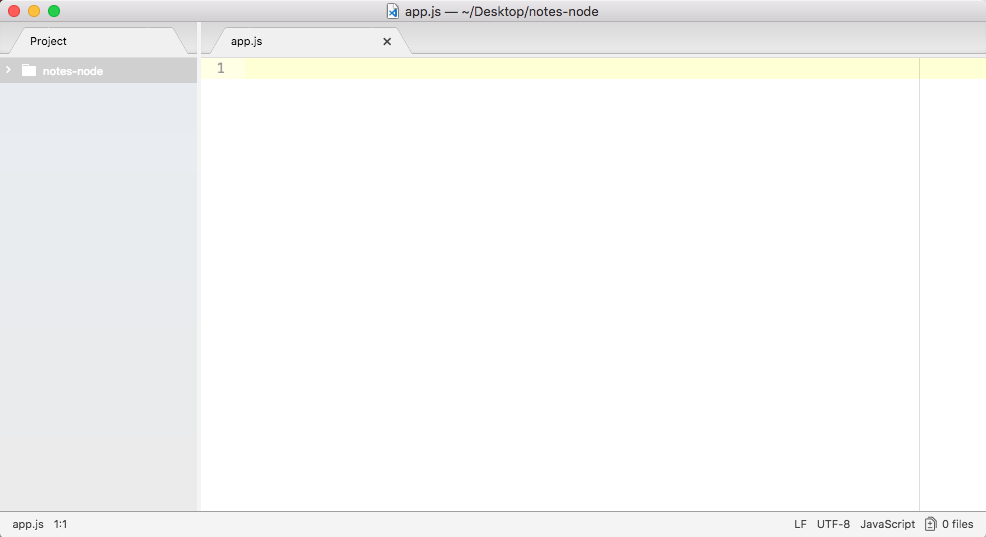

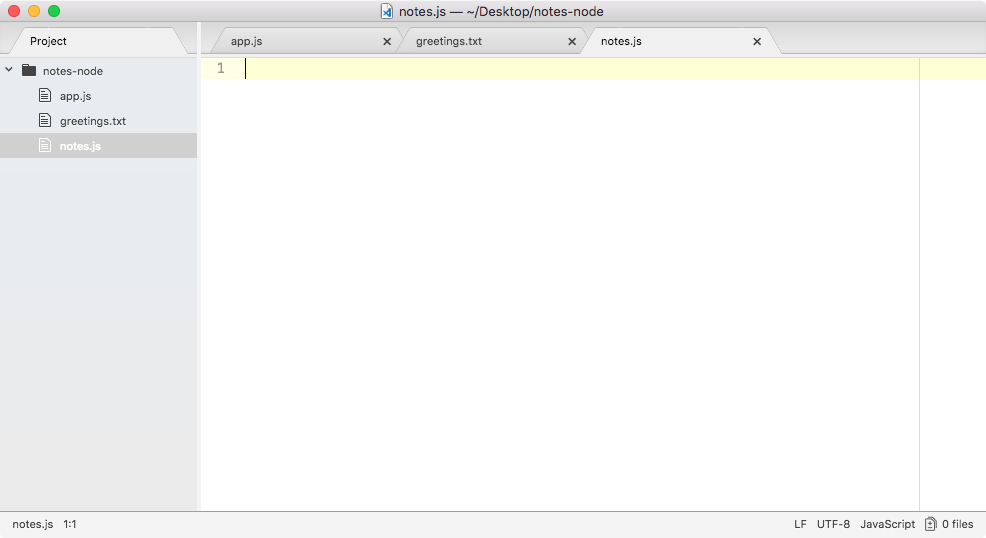

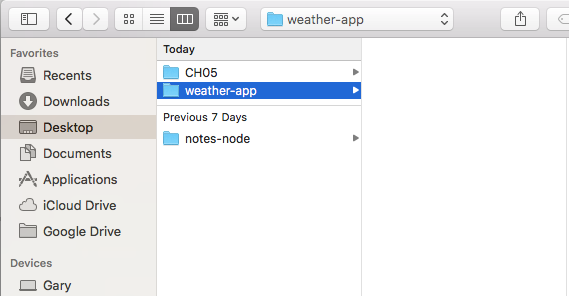

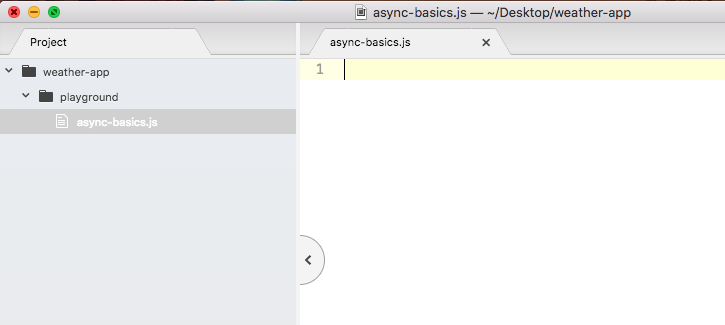

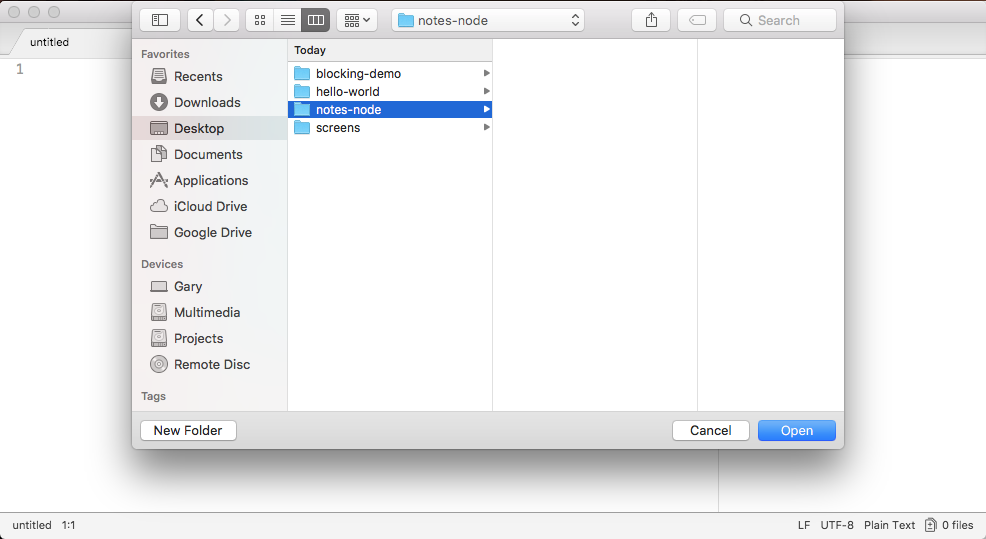

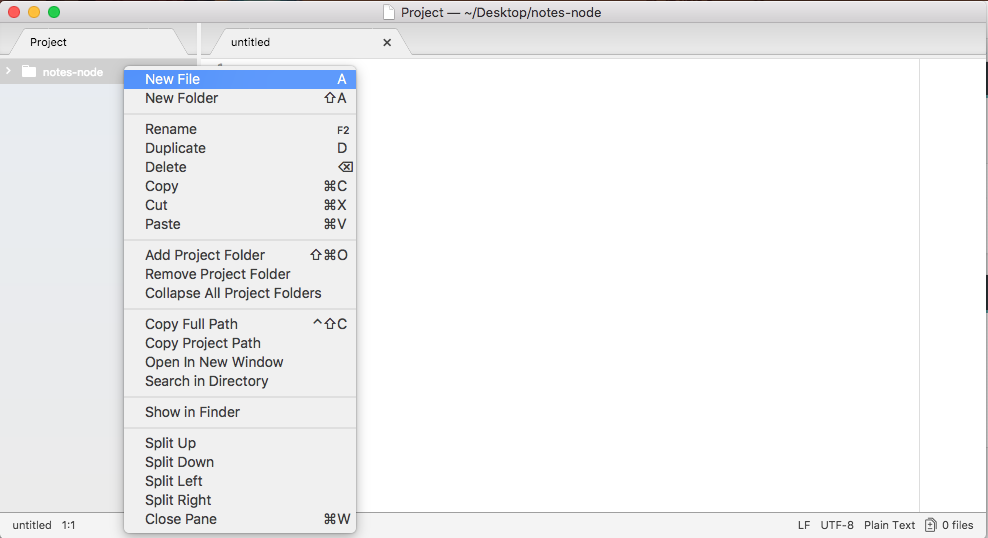

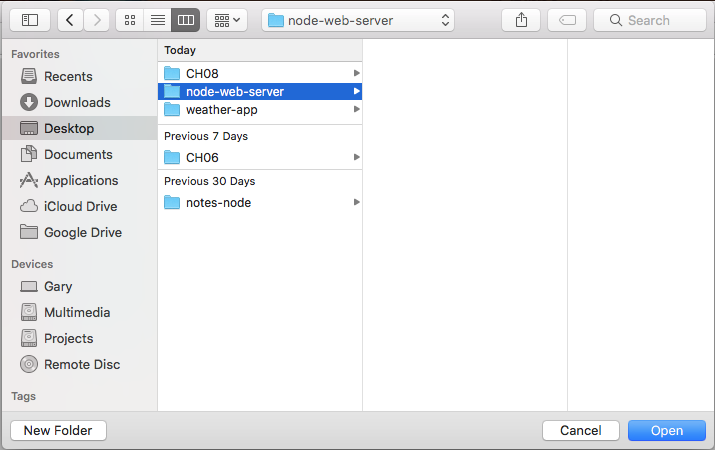

The next step in the process is to open up that directory inside the Atom text editor. So open up the directory we just created on the Desktop, and you will find it there, as shown in the following screenshot:

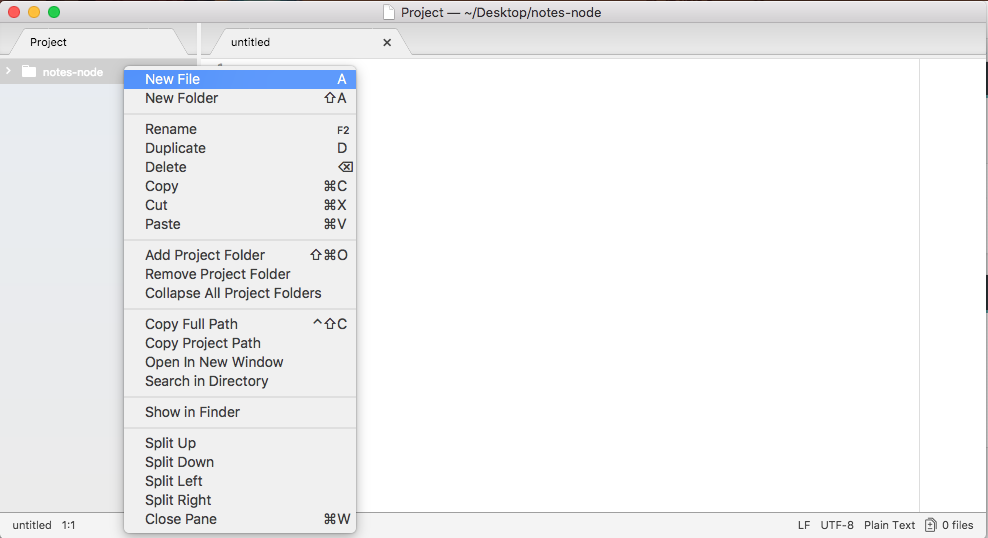

Now, we will need to make a file, and we'll put that file in the root of the project:

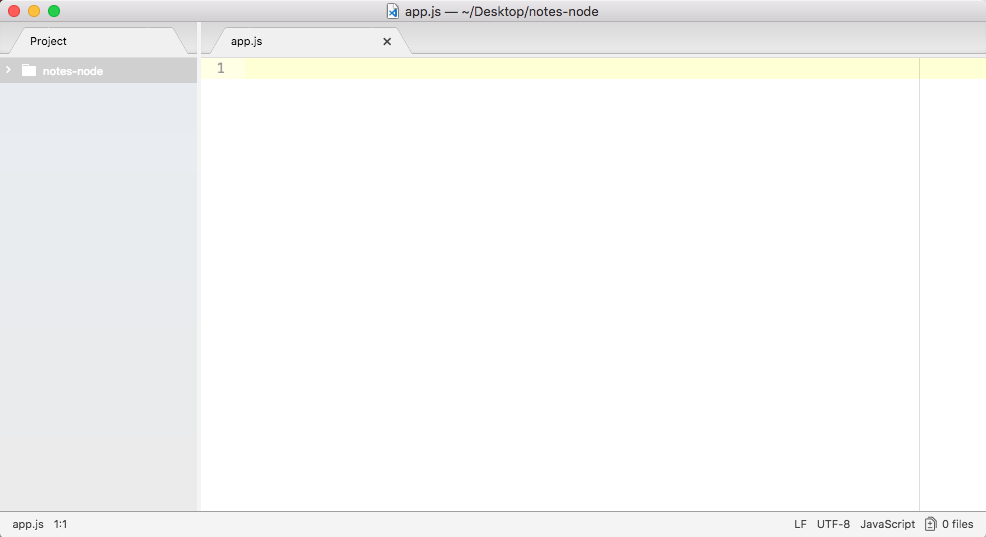

We'll call this file app.js, and this is where our application will start:

We will be writing other files that get used throughout the app, but this is the only file we'll ever be running from Terminal. This is the initialization file for our application.

Now, to kick things off, the first thing I will do is to use console.log to print Starting app, as shown in the following code:

console.log('Starting app');

After we call the console.log starting app, we'll load in a built-in module using require().

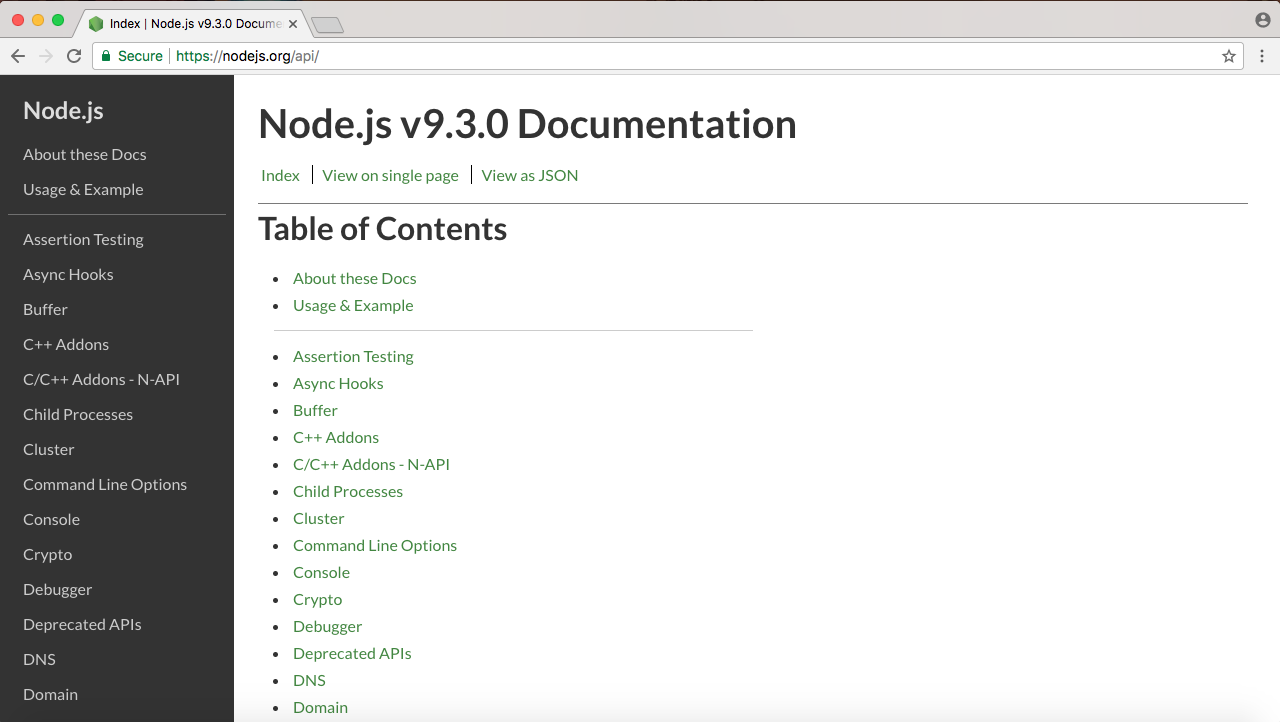

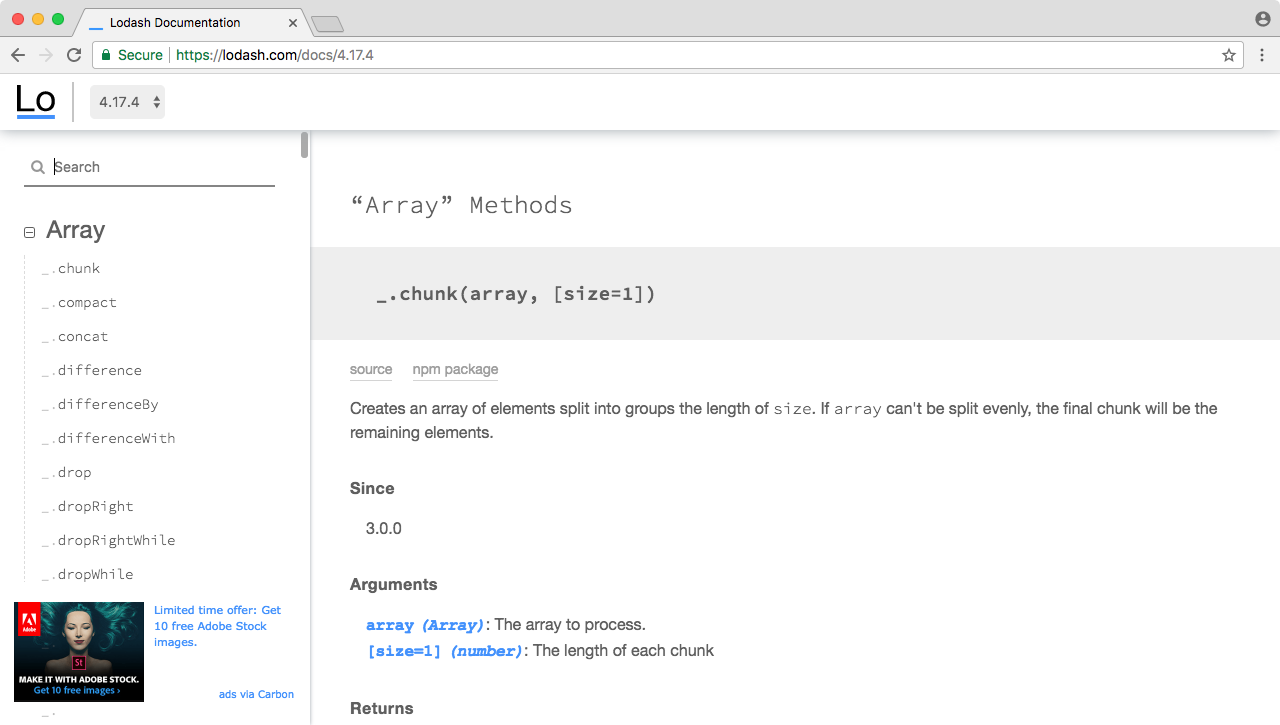

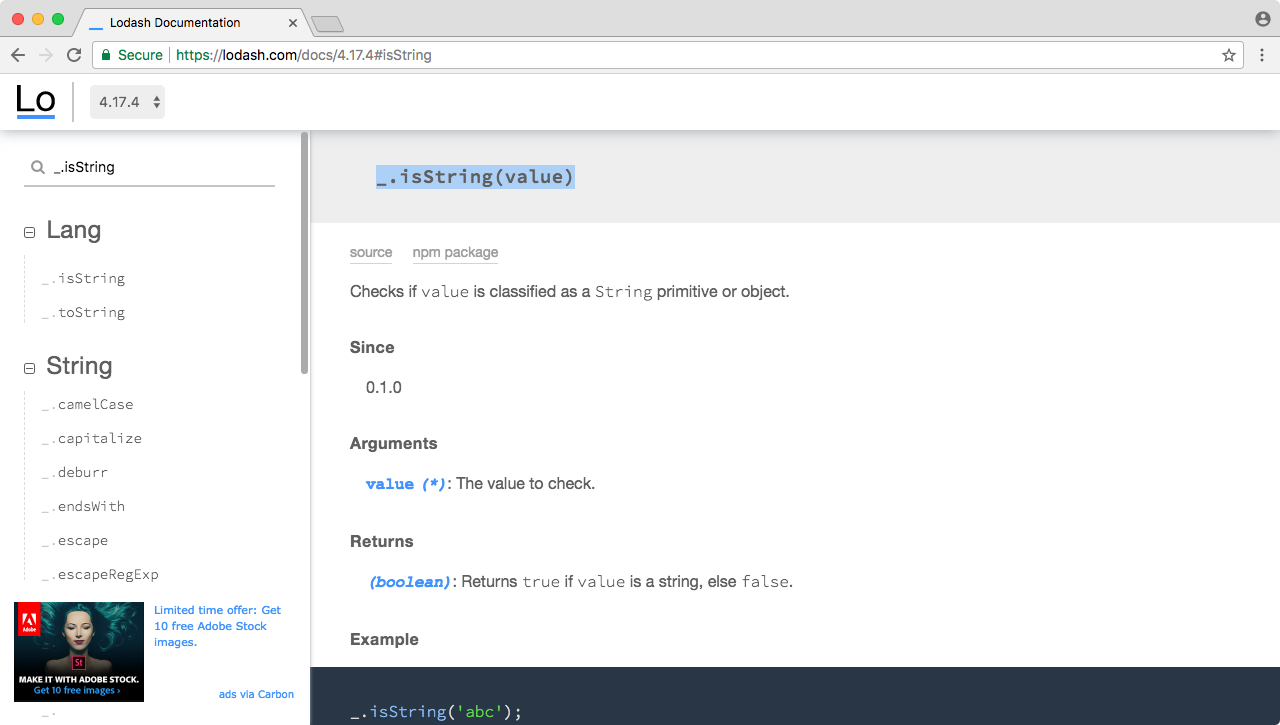

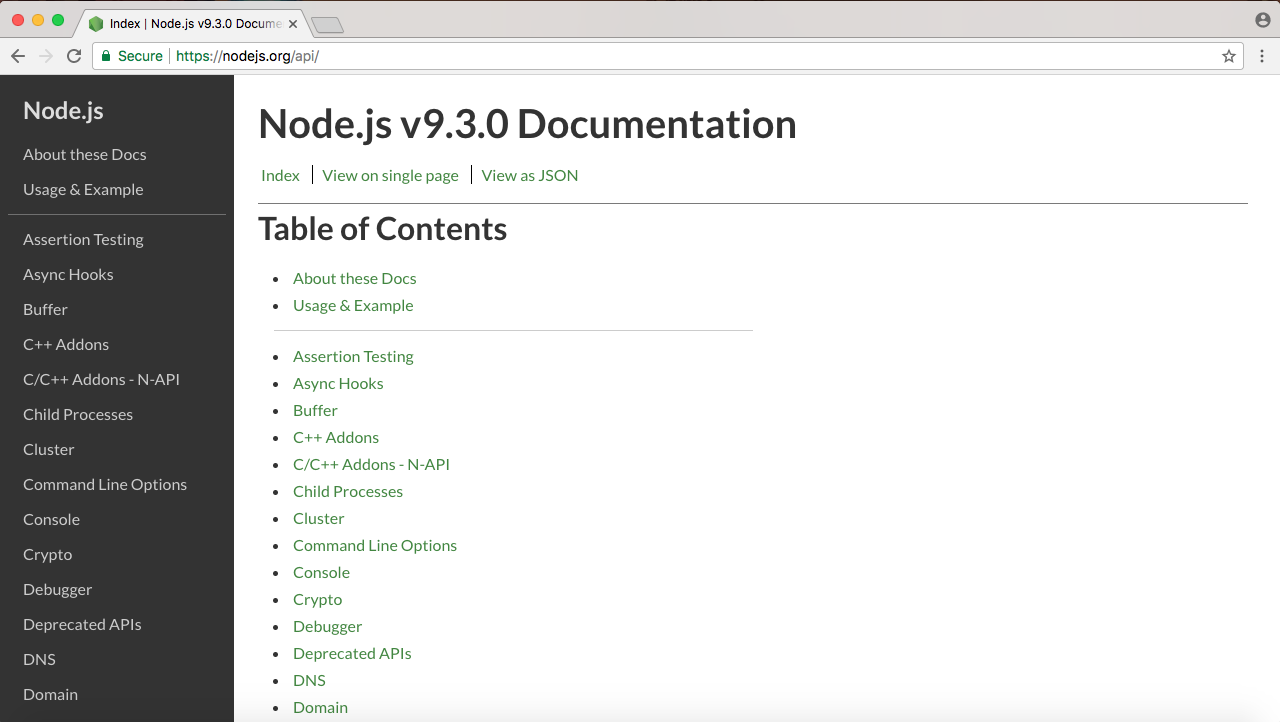

To view Node.js API docs, go to nodejs.org/api. When you go to this URL, you'll be greeted with a long list of built-in modules. Using the File System module we'll create a new file and the OS module. The OS module will let us fetch things such as the username for the currently logged-in user.

To kick things off though, we will start with the File System module. We'll go through the process of creating a file and appending to it:

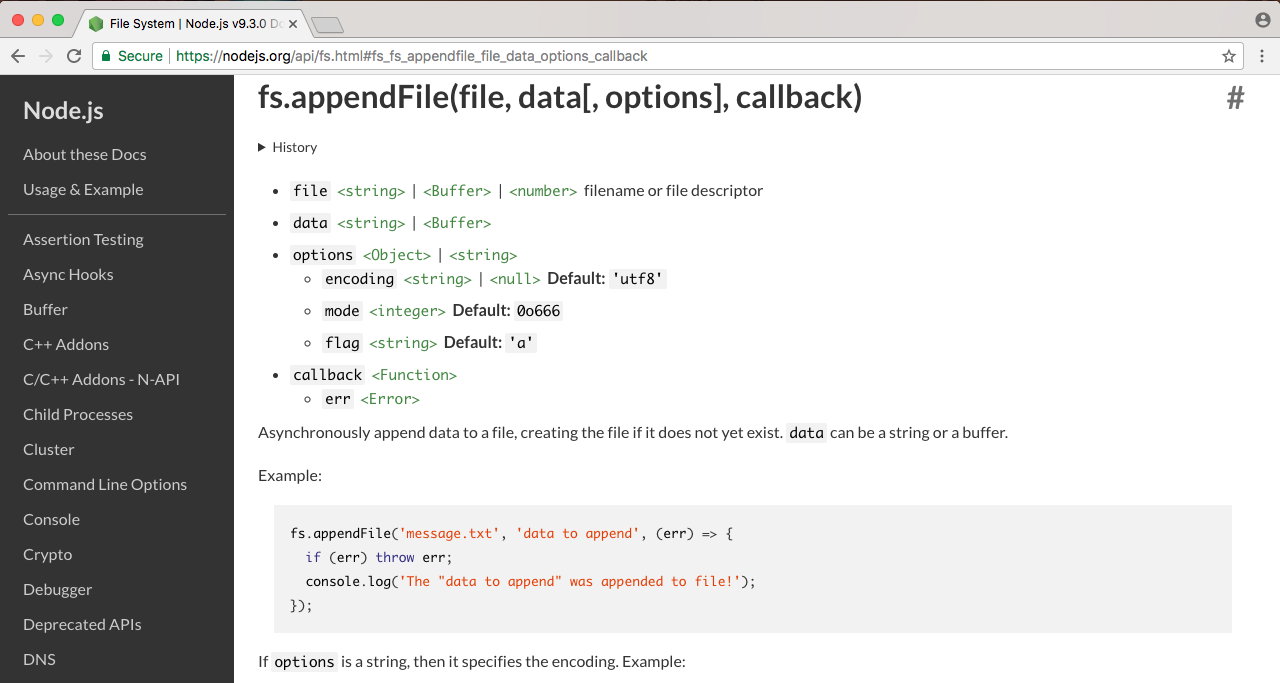

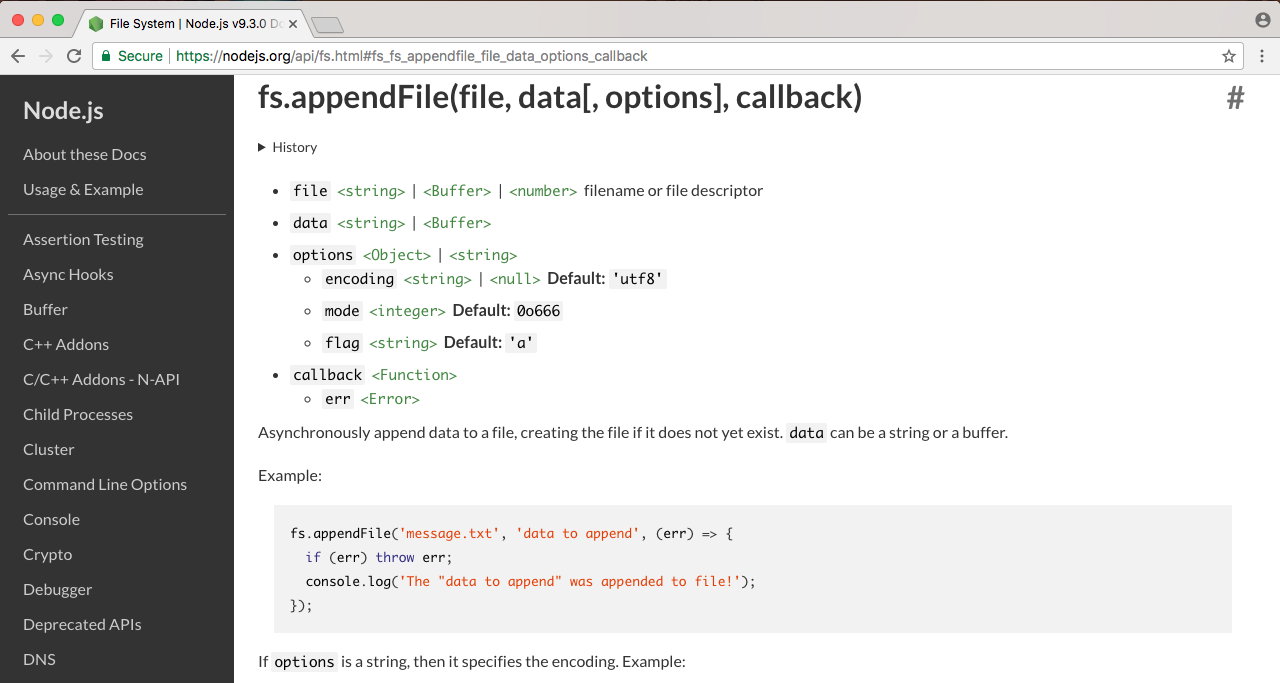

When you view a docs page for a built-in module, whether it's File System or a different module, you'll see a long list of all the different functions and properties that you have available to you. The one we'll use in this section is fs.appendFile.

If you click on it, it will take you to the specific documentation, and this is where we can figure out how to use appendFile, as shown in the following screenshot:

Now, appendFile is pretty simple. We'll pass to it two string arguments (shown in the preceding screenshot):

This is all we need to provide in order to call fs.appendFile. Before we can call fs.appendFile, we need to require it. The whole point of requiring is to let us load in other modules. In this case, we'll load in the fs module from app.js.

Let's create a variable that will be a constant, using const.

Then we'll give it a name, fs and set it equal to require(), as shown in the following code:

const fs = require()

Here, require() is a function that's available to you inside any of your Node.js files. You don't have to do anything special to call it, you simply call it as shown in the preceding code. Inside the argument list, we'll just pass one string.

In our case, we'll pass in the module name, which is fs and toss in a semicolon at the end, as shown in the following code:

const fs = require('fs');

This will tell Node that you want to fetch all of the contents of the fs module and store them in the fs variable. At this point, we have access to all of the functions available on the fs module, which we explored over in the docs, including fs.appendFile.

Back in Atom, we can call the appendFile by calling fs.appendFile, passing in the two arguments that we'll use; the first one will be the filename, so we add greetings.txt, and the second one will be the text you want to append to the file. In our case, we'll append Hello world!, as shown in the following code:

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', 'Hello world!');

Let's save the file, as shown in the preceding command, and run it from Terminal to see what happens.

// Orignal line

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', 'Hello world!');

// Option one

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', 'Hello world!', function (err){

if (err) {

console.log('Unable to write to file');

}

});

// Option two

fs.appendFileSync('greetings.txt', 'Hello world!');

In the preceding code, we have the original line that we have inside our program.

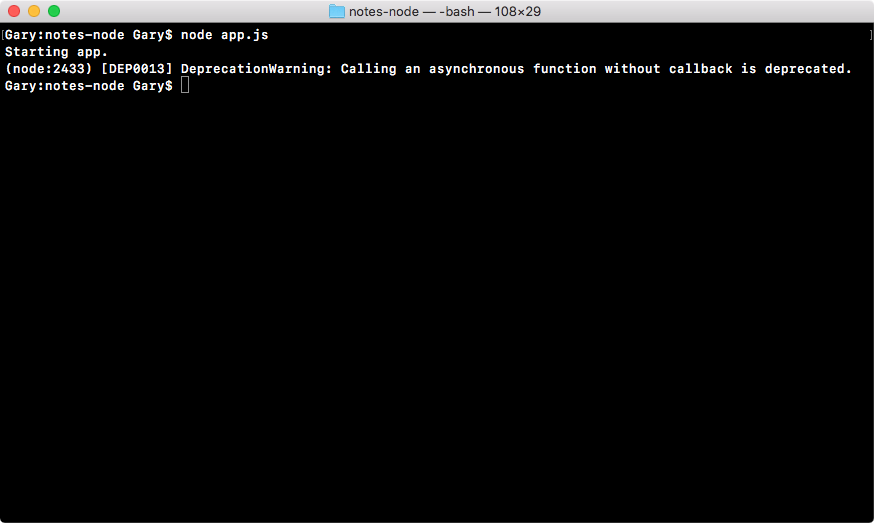

In Option one here is to add a callback as the third argument to the append file. This callback will get executed when either an error occurs or the file successfully gets written too. Inside option one, we have an if statement; if there is an error, we simply print a message to the screen, Unable to write to file.

Now, our second option in the preceding code, Option two, is to call appendFileSync, which is a synchronous method (we'll talk more about that later); this function does not take the third argument. You can type it as shown in the preceding code and you won't get the warning.

So, pick one of these two options if you see the warning; both will work much the same.

If you are on v6, you can stick with the the original line, shown at the top of the preceding code, although you might as well use one of the two options below that line to make your code a little more future proof.

Fear not, we'll be talking about asynchronous and synchronous functions, as well as callback functions, extensively throughout the book. What I'm giving you here in the code is just a template, something you can write in your file to get that error removed. In a few chapters, you will understand exactly what these two methods are and how they work.

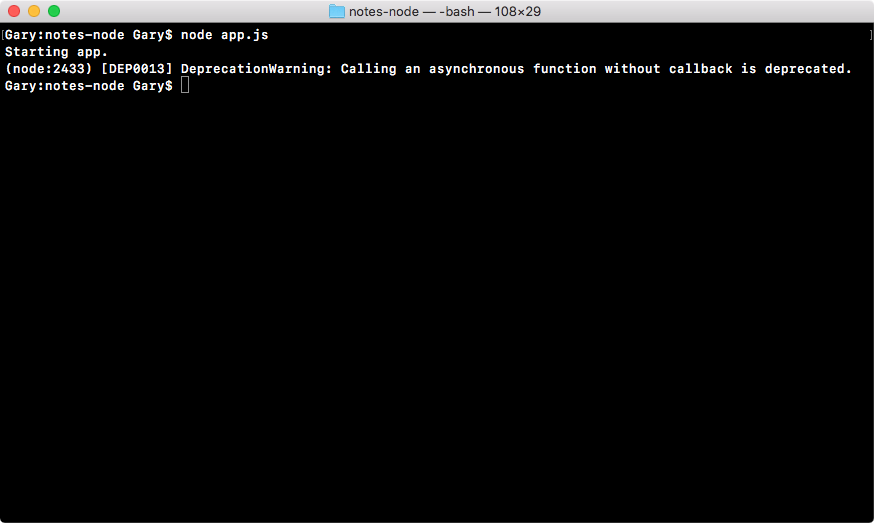

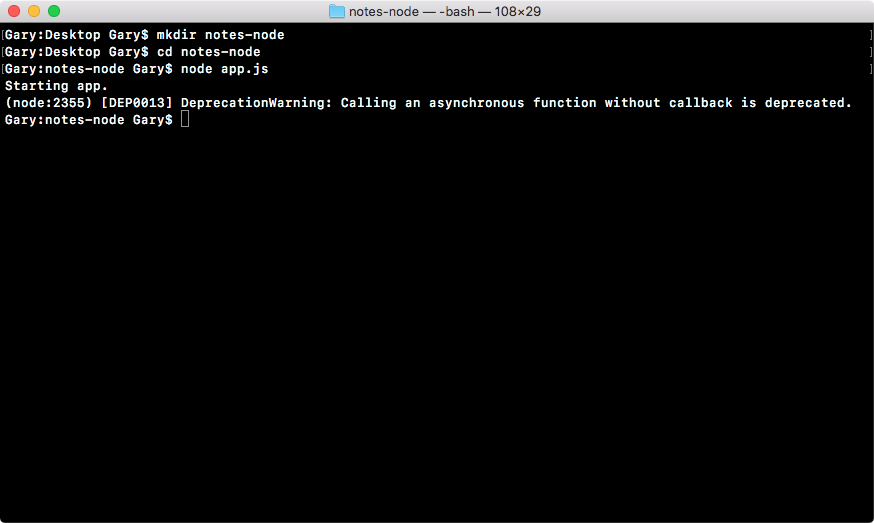

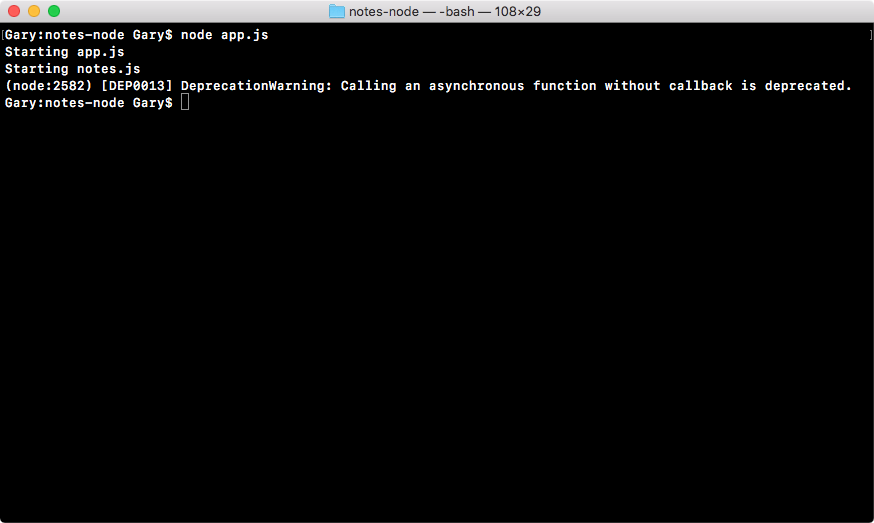

If we do the appending over in Terminal, node app.js, we'll see something pretty cool:

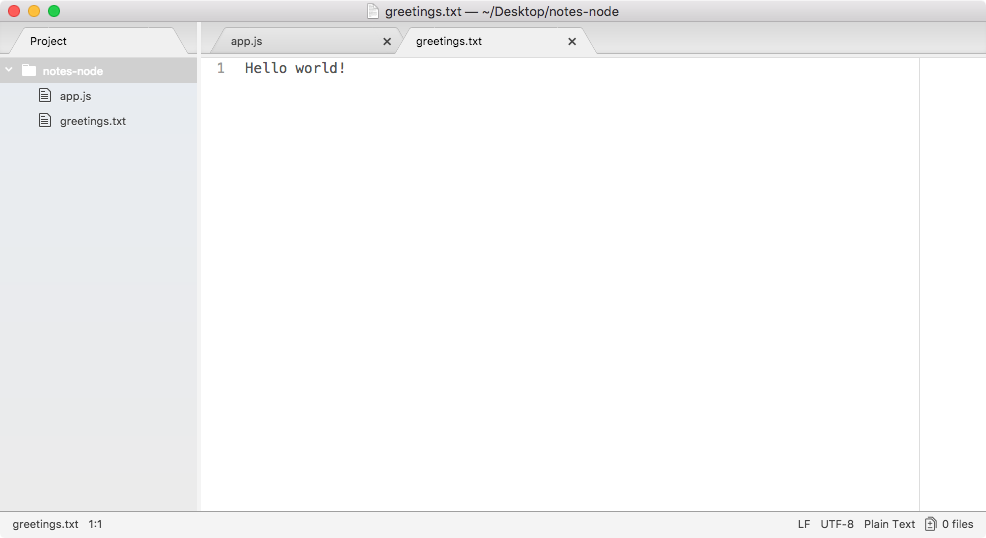

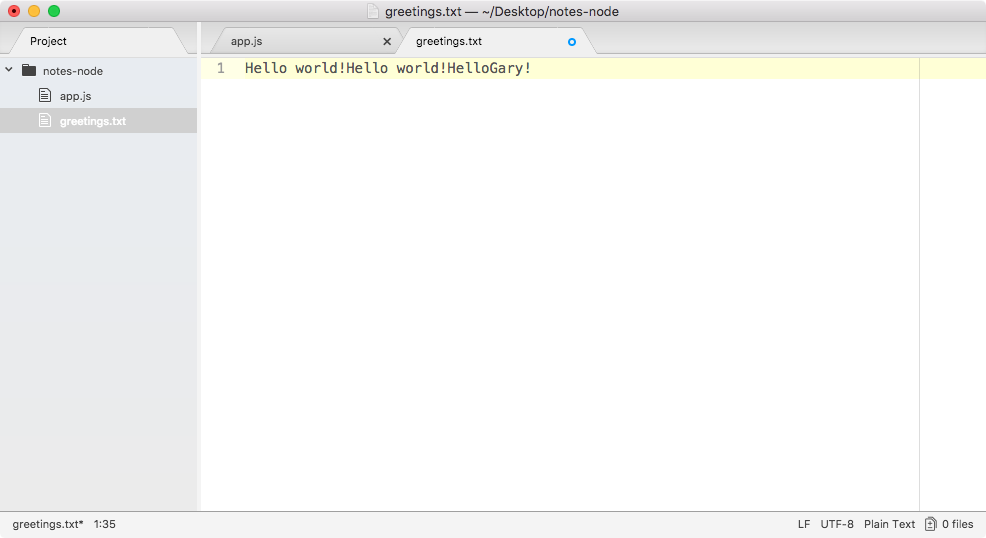

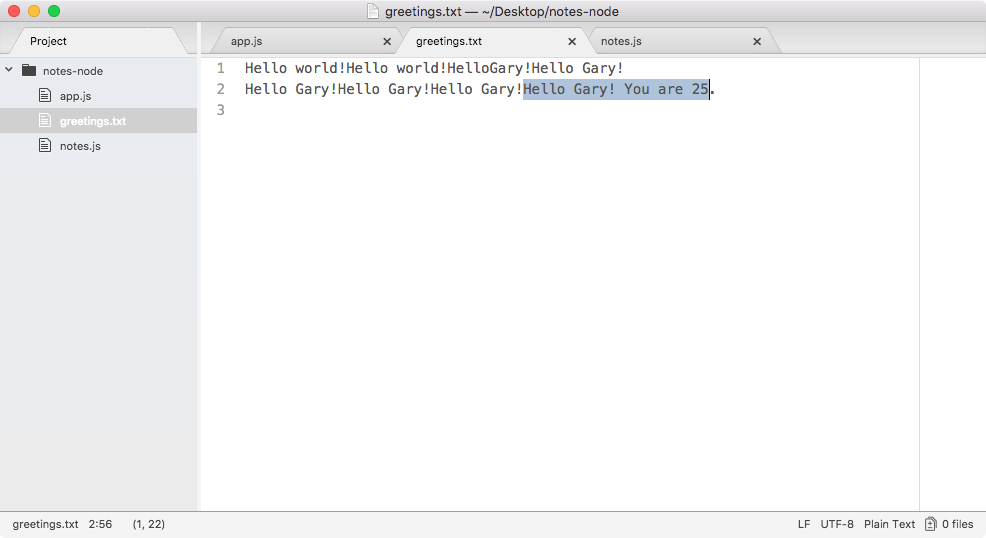

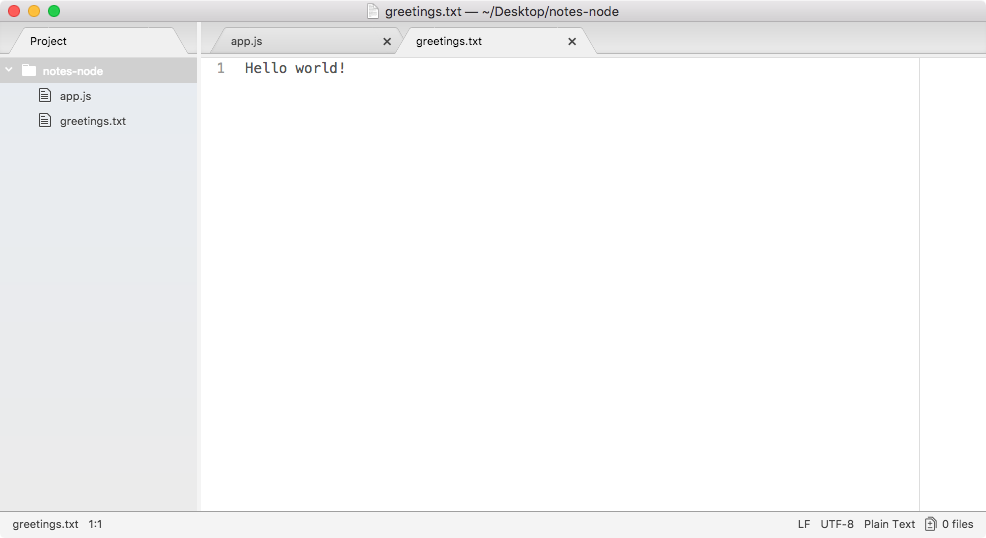

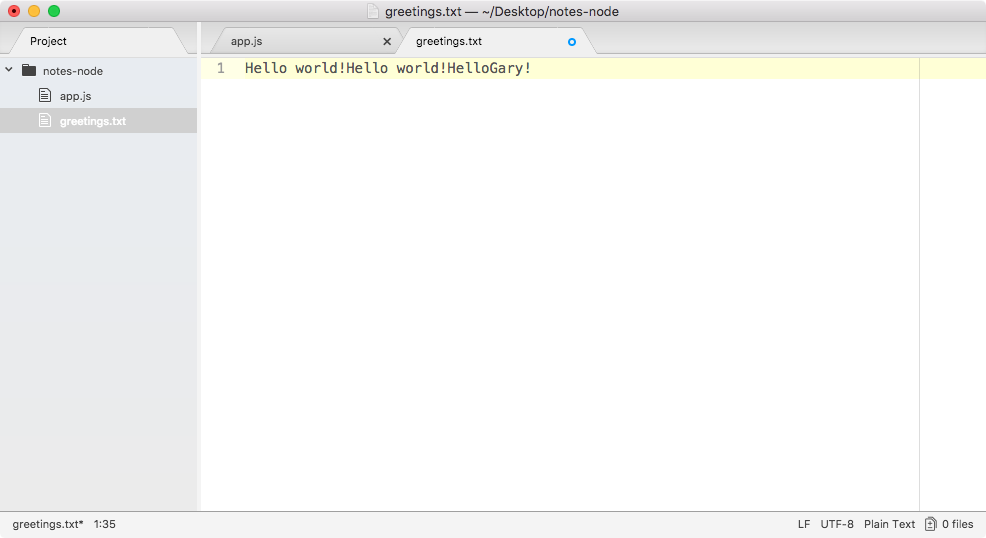

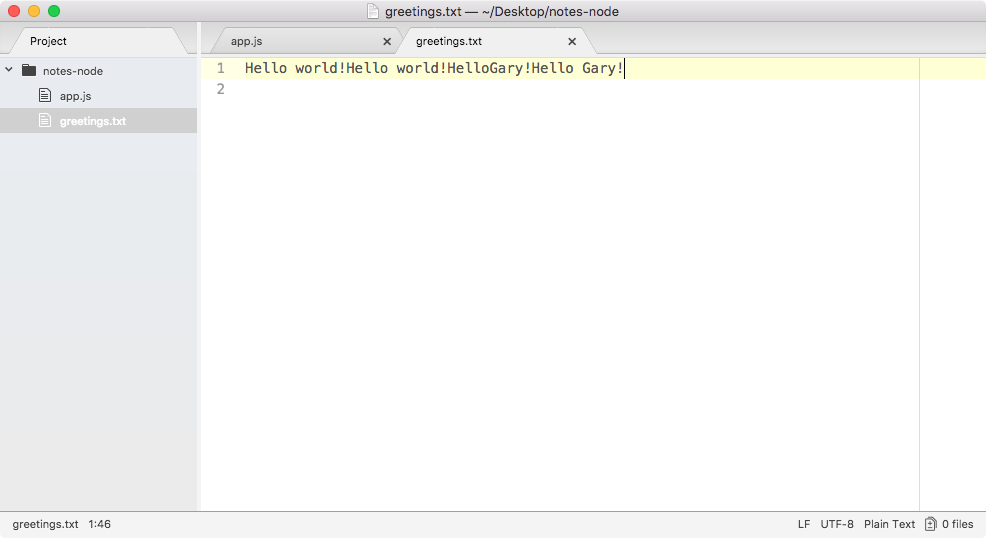

As shown in the preceding code, we get our one console.log statement, Starting app.. So we know the app started correctly. Also, if we head over into Atom, we'll actually see that there's a brand new greetings.txt file, as shown in the following code. This is the text file that was created by fs.appendFile:

console.log('Starting app.');

const fs = require('fs');

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', 'Hello world!');

Here, fs.appendFile tries to append greetings.txt to a file; if the file doesn't exist, it simply creates it:

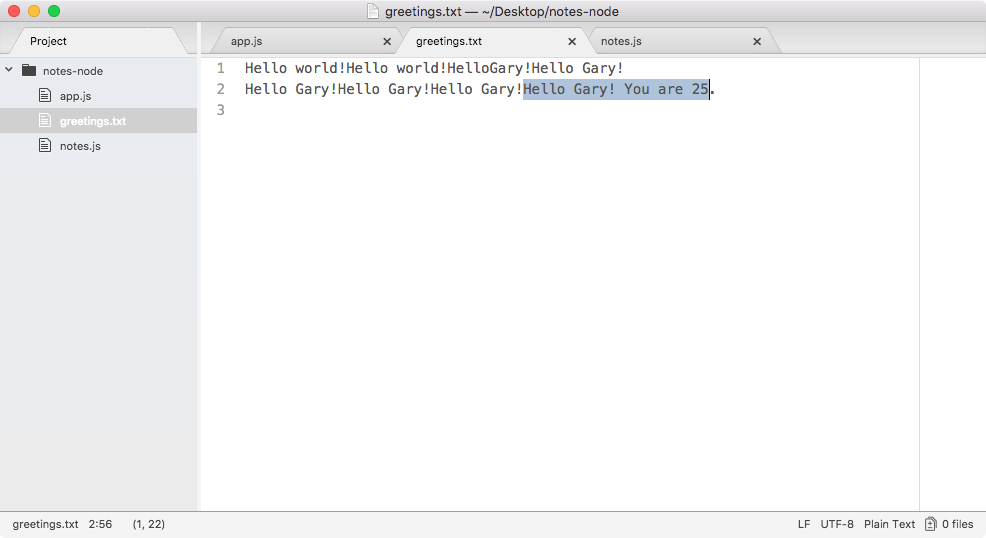

You can see that we have our message, Hello world! in the greetings.txt file, printing to the screen. In just a few minutes, we were able to load in a built-in Node module and call a function that lets us create a brand new file.

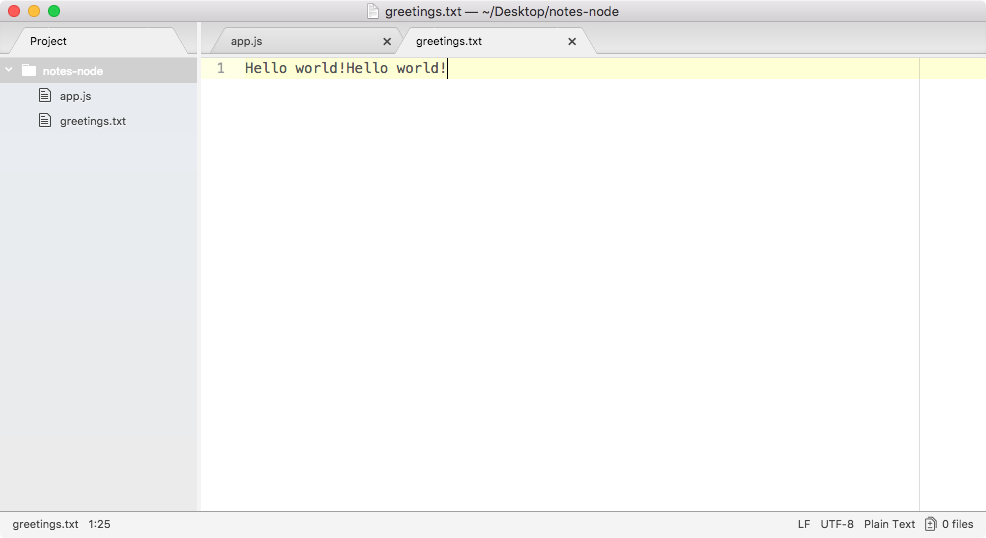

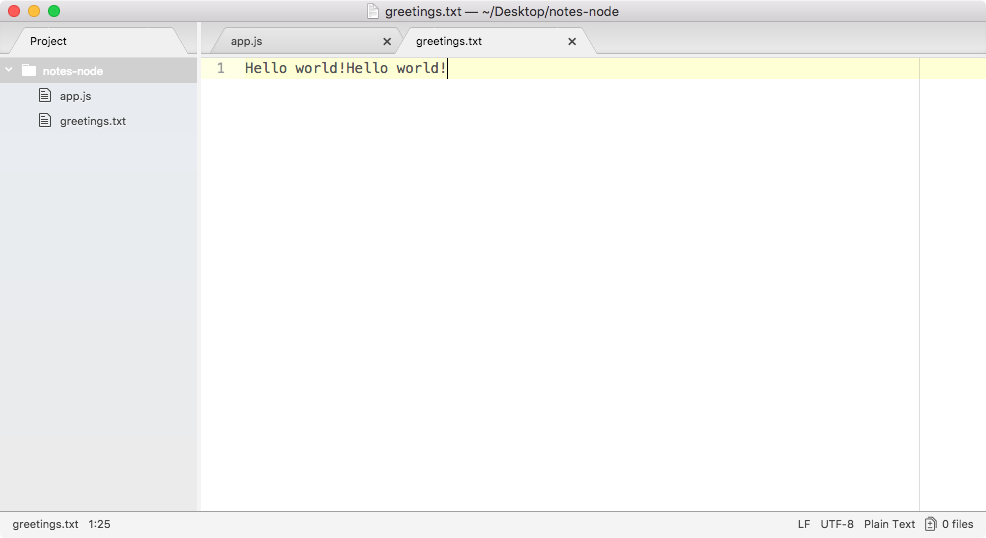

If we call it again by rerunning the command using the up arrow key and the enter key, and we head back into the contents of greetings.txt, you can see this time around that we have Hello world! twice, as shown here:

It appended Hello world! one time for each time we ran the program. We have an application that creates a brand new file on our filesystem, and if the file already exists, it simply adds to it.

Once we have created and appended the greetings.txt file, we'll customize this greeting.txt file. To do this, we'll explore one more built-in module. We'll be using more than just appendFile in the future. We'll be exploring other methods. For this section, the real goal is to understand require(). The require() function lets us load in the module's functionality so that we can call it.

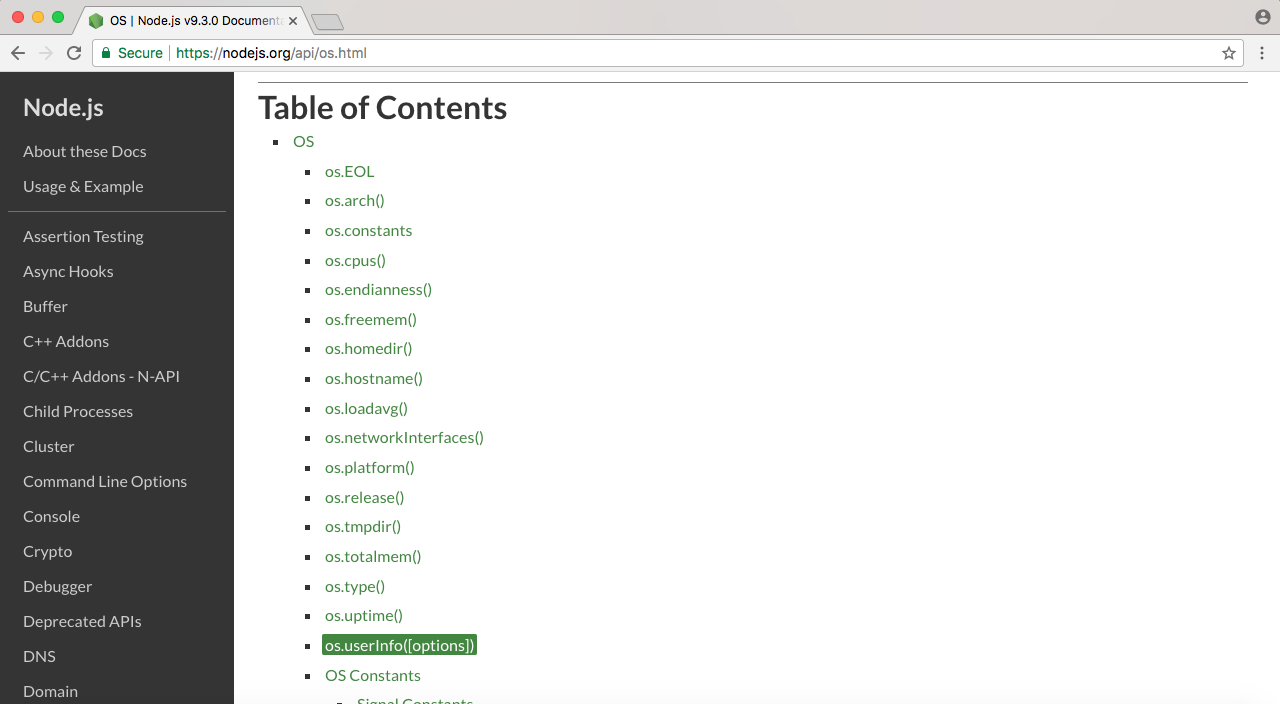

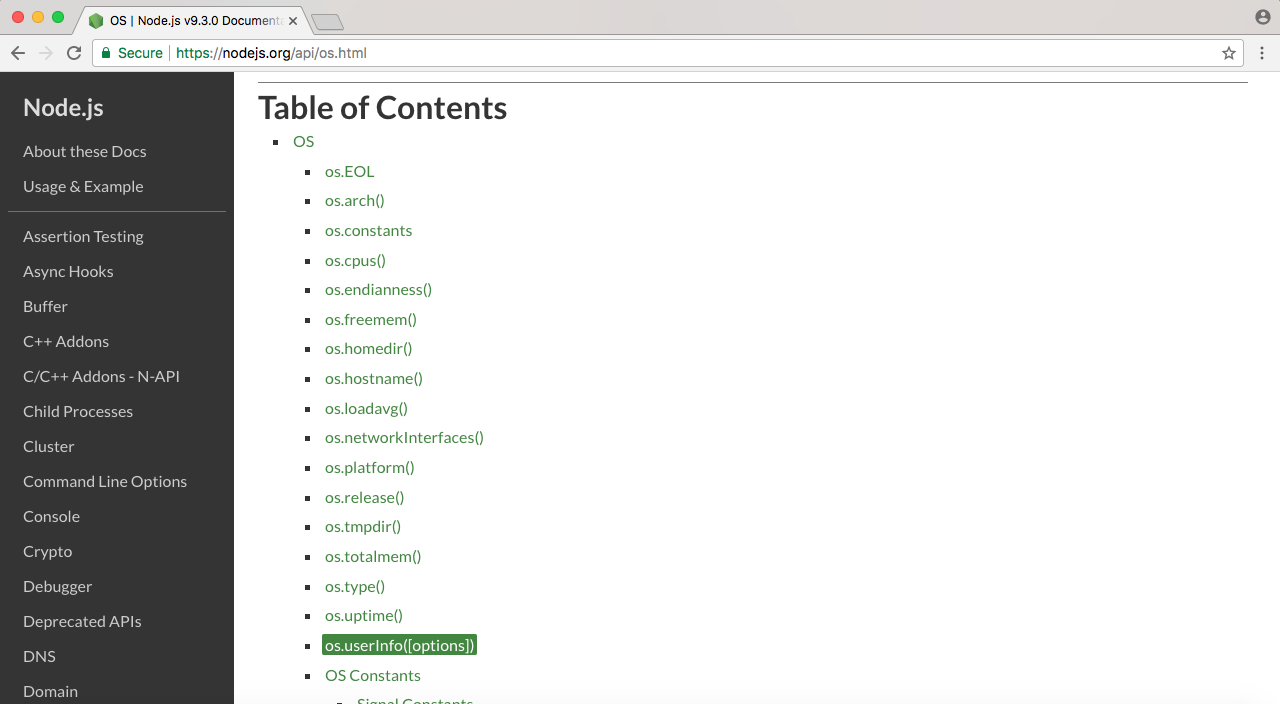

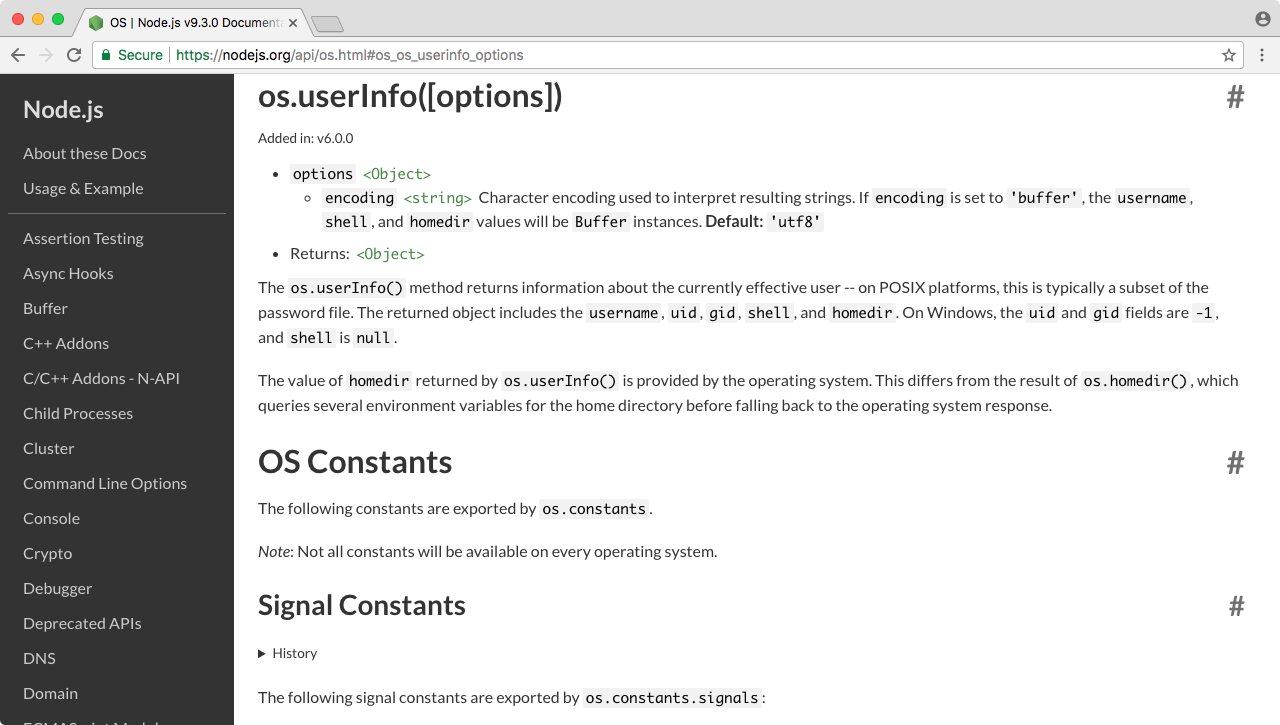

The second module that we'll be using is OS, and we can view it in the documentation. In the OS module, we'll use the method defined at the very bottom, os.userInfo([options]):

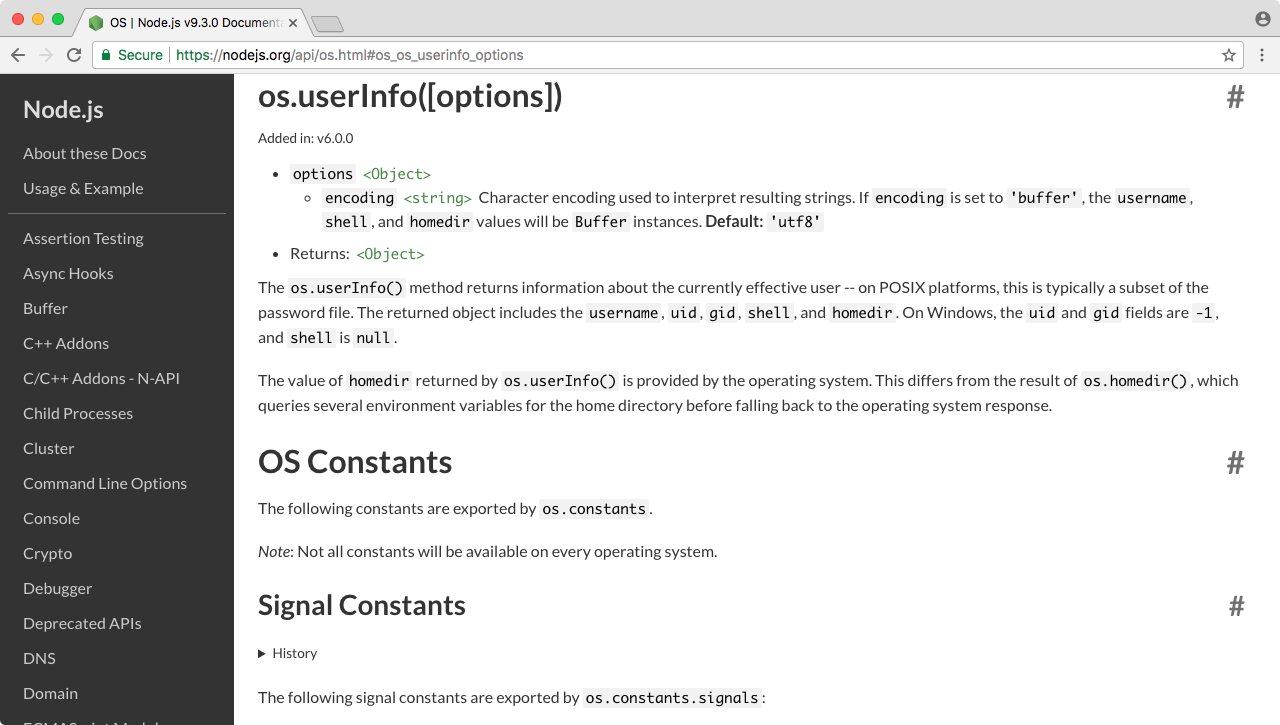

The os.userInfo([options]) method gets called and returns various information about the currently logged-in user, such as the username, and this is what we'll pull off:

Using the username that comes from the OS, we can customize the greeting.txt file so that instead of Hello world! it can say Hello Gary!.

To get started, we have to require OS. This means that we'll go back inside Atom. Now, just below where I created my fs constant, I'll create a new constant called os, setting it equal to require(); this gets called as a function and passes one argument, the module name, os, as shown here:

console.log('Starting app.');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', 'Hello world!');

From here, we can start calling methods available on the OS module, such as os.userInfo([optional]).

Let's make a new variable called user to store the result. The variable user will get set equal to os.userInfo, and we can call userInfo without any arguments:

console.log('Starting app.');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

var user = os.userInfo();

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', 'Hello world!');

Now, before we do anything with the fs.appendFile line, I'll comment it out and print the contents of the user variable using console.log:

console.log('Starting app.');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

var user = os.userInfo();

console.log(user);

// fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', 'Hello world!');

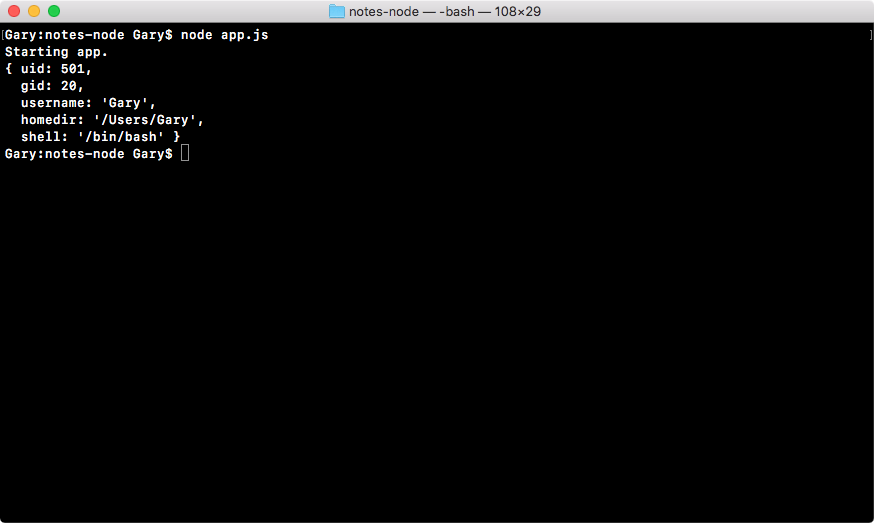

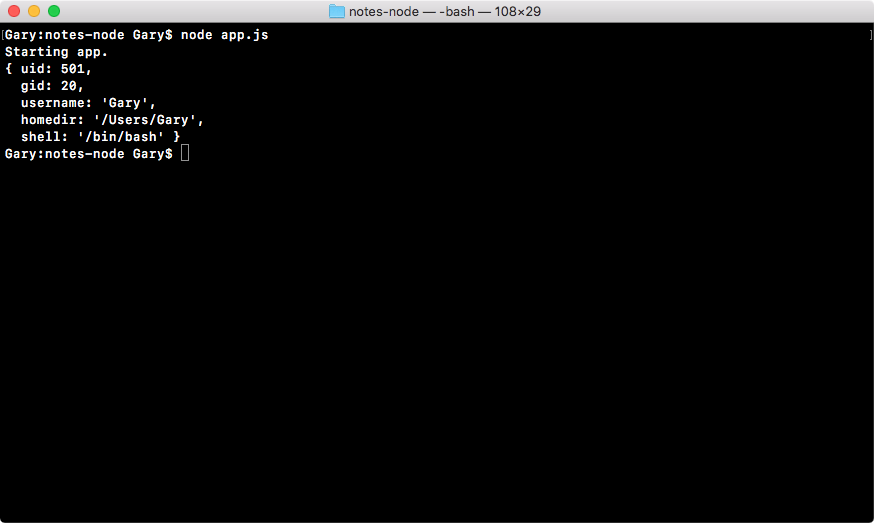

This will let us explore exactly what we get back. Over in Terminal, we can rerun our program using the up arrow key and enter key, and right here in the following code, you see that we have an object with a few properties:

We have uid, gid, username, homedir, and shell. Depending on your OS, you'll not have all of these, but you should always have the username property. This is the one we care about.

This means that back inside Atom, we can use user.username inside of appendFile. I'll remove the console.log statement and uncomment our call to fs.appendFile:

console.log('Starting app.');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

var user = os.userInfo();

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', 'Hello world!');

Now, where we have world in the fs.appendFile, we'll swap it with user.username. There are two ways we can do this.

The first way is to remove world! and concatenate user.username. Then we can concatenate another string using the + (plus) operator, as shown in the following code:

console.log('Starting app.');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

var user = os.userInfo();

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', 'Hello' + user.username + '!');

Now if we run this, everything is going to work as expected. Over in Terminal, we can rerun our app. It prints Starting app:

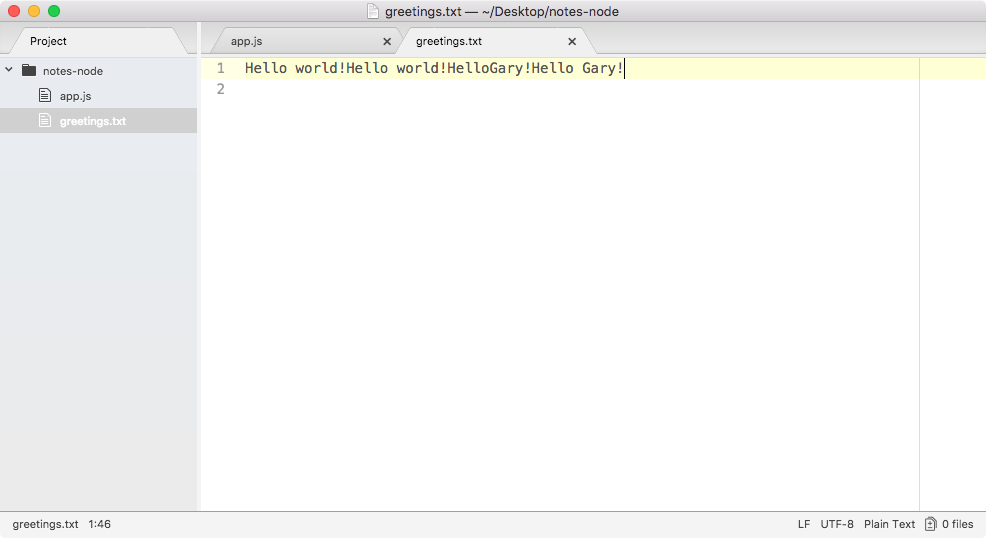

Over in the greetings.txt file, you should see something like Hello Gary! printing to the screen, as shown here:

Using the fs module and the os module, we were able to grab the user's username, create a new file, and store it.

The second way to swap world with user.username in the fs.appendFile is, using an ES6 feature known as template strings. Template strings start and end with the ` (tick) operator, which is available to the left of the 1 key on your keyboard. Then you type things as you normally would.

This means that we'll first type hello, then we'll add a space with the ! (exclamation) mark, and just before !, we will put the name:

console.log('Starting app.');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

var user = os.userInfo();

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', `Hello !`);

To insert a JavaScript variable inside your template string, you use the $ (dollar) sign followed by opening and closing curly braces. Then we will just reference a variable such as user.username:

console.log('Starting app.');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

var user = os.userInfo();

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', `Hello ${user.username}!`);

This is all it takes to use template strings; it's an ES6 feature available because you're using Node v6. This syntax is much easier to understand and update than the string/concatenation version we saw earlier.

If you run the code, it will produce the exact same output. We can run it, view the text file, and this time around, we have Hello Gary! twice, which is what we want here:

With this in place, we are now done with our very basic example and we're ready to start creating our own files for our notes application and requiring them inside app.js in the next section.

First up, you learned that we can use require to load in modules. This lets us take existing functionality written by either the Node developers, a third-party library, or ourselves, and load it into a file so that it can be reusable. Creating reusable code is essential for building large apps. If you have to build everything in an app every time, no one would ever get anything done because they would get stuck at building the basics, things such as HTTP servers and web servers. There are already modules for such stuff, and we'll be taking advantage of the great npm community. In this case, we used two built-in modules, fs and os. We loaded them in using require and we stored the module results inside two variables. These variables store everything available to us from the module; in the case of fs, we use the appendFile method, and in the case of OS, we use the userInfo method. Together, we were able to grab the username and save it into a file, which is fantastic.

In this section, you will learn how to use require() to load in other files that you created inside your project. This will let you move functions outside app.js into more specific files; this will make your application easier to scale, test, and update. To get started, the first thing we'll do is to make a new file.

In the context of our notes app, the new file will store various functions for writing and reading notes. As of now, you don't need to worry about that functionality, as we'll get into the detail later in the section, but we will create the file where it will eventually live. This file will be notes.js, and we'll save it inside the root of our application, right alongside app.js and greetings.txt, as shown here:

For the moment, all we'll do inside notes is to use console.log to print a little log showing the file has been executed using the following code:

console.log('Starting notes.js');

Now, we have console.log on the top of notes and one on the top of app.js. I'll change console.log in the app.js from Starting app. to Starting app.js. With this in place, we can now require the notes file. It doesn't export any functionality, but that's fine.

We'll look at how to export stuff later in the section. For now though, we'll load our module in much the same way we loaded in the built-in Node modules.

Let's make const; I'll call this one notes and set it equal to the return result from require():

console.log('Starting app.js');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

const notes = require('');

var user = os.userInfo();

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', `Hello ${user.username}!`);

Inside the parentheses, we will pass in one argument that will be a string, but it will be a little different. In the previous section, we typed in the module name, but what we have in this case is not a module, but a file, notes.js. What we need to do is to tell Node where that file lives using a relative path.

Now, relative paths start with ./ (a dot forward slash), which points to the current directory that the file is in. In this case, this points us to the app.js directory, which is the root of our project notes-node. From here, we don't have to go into any other folders to access notes.js, it's in the root of our project, so we can type its name, as shown in the following code:

console.log('Starting app.js');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

const notes = require('./notes.js');

var user = os.userInfo();

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', `Hello ${user.username}!`);

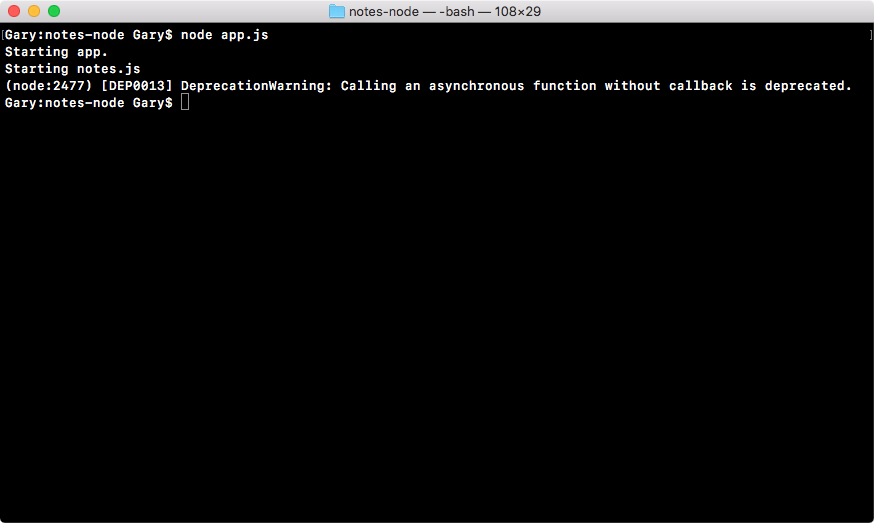

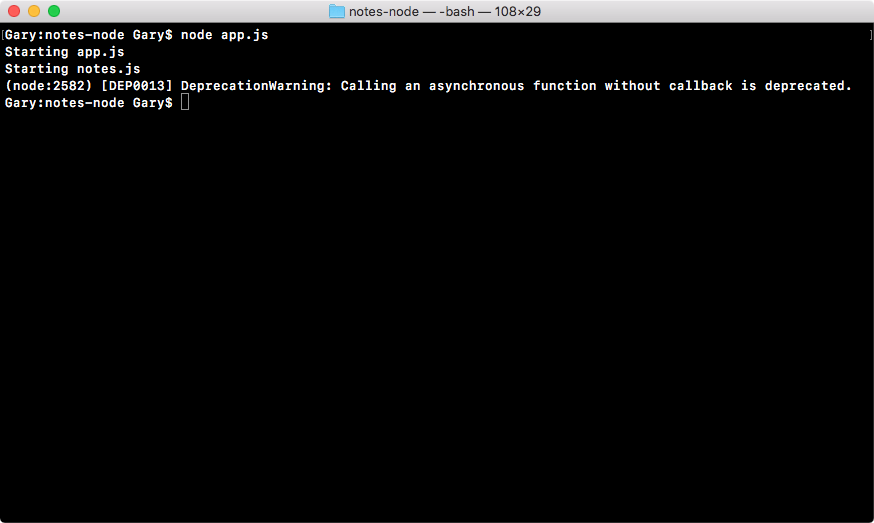

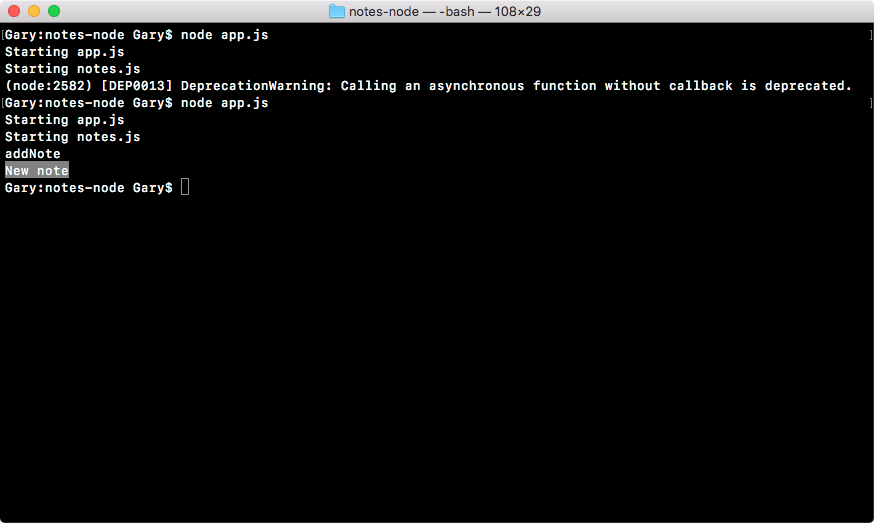

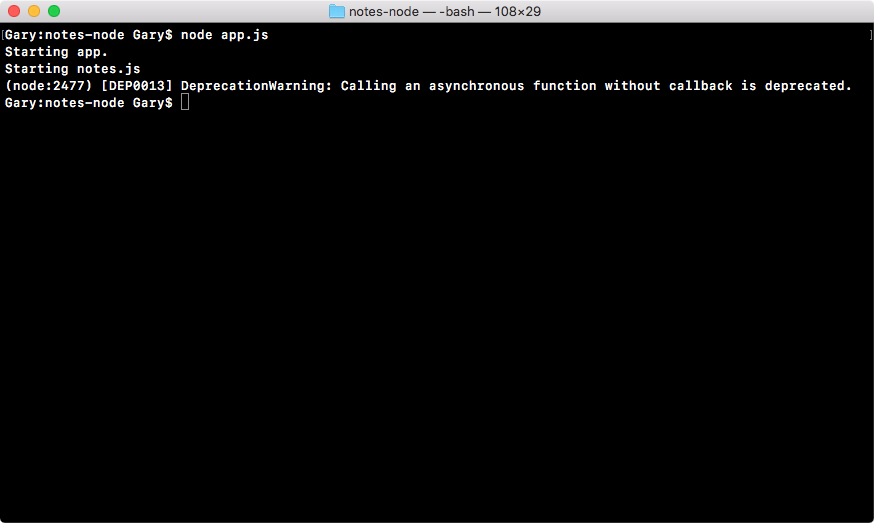

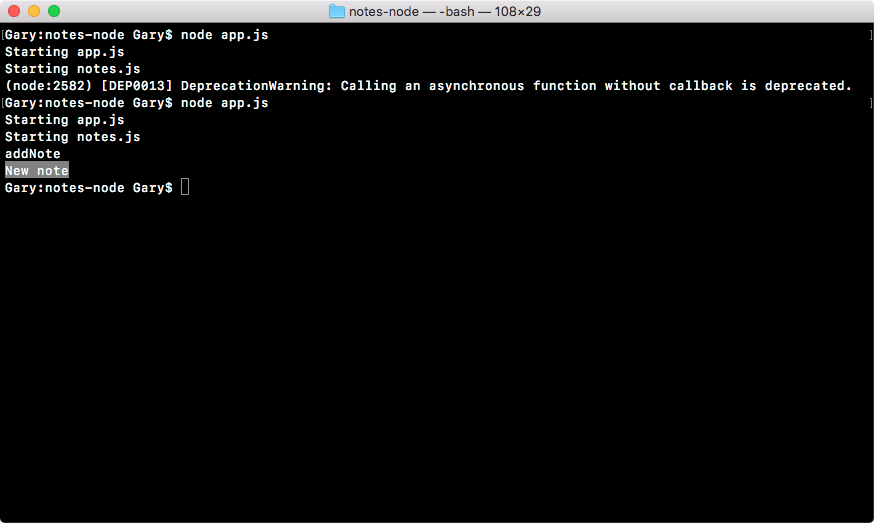

With this in place, we can now save app.js and see what happens when we run our application. I'll run the app using the node app.js command:

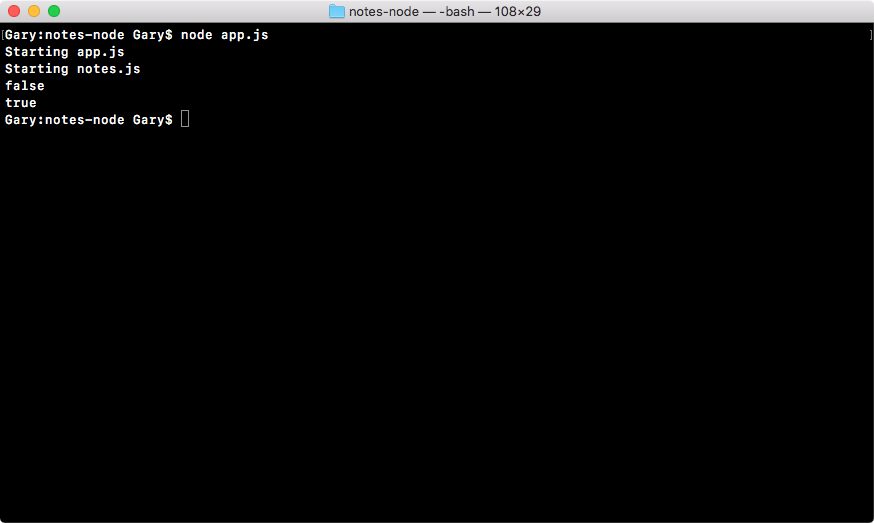

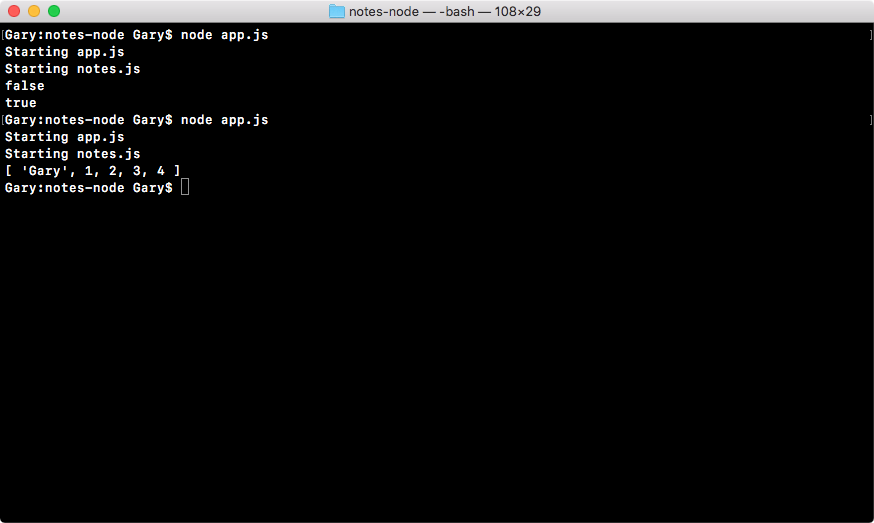

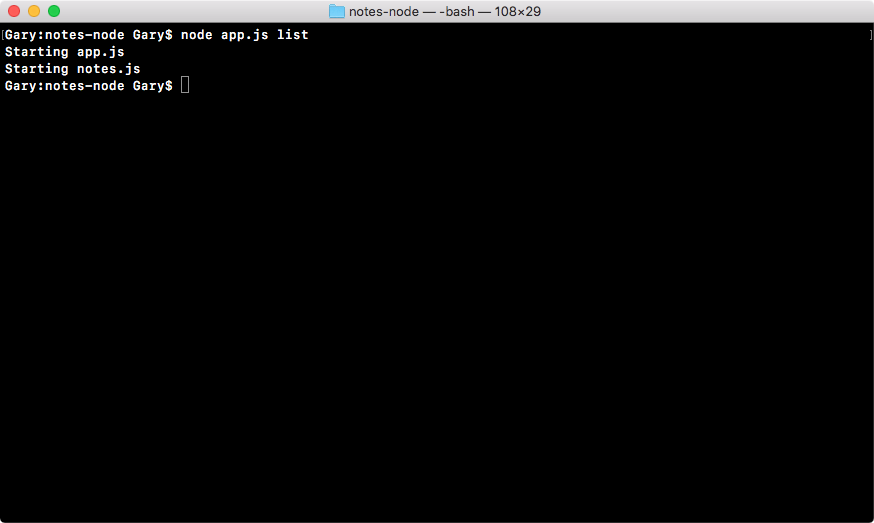

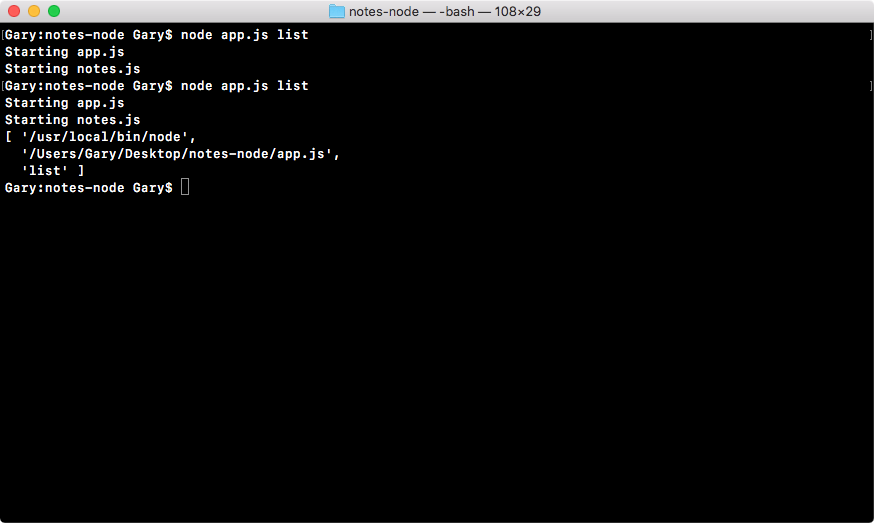

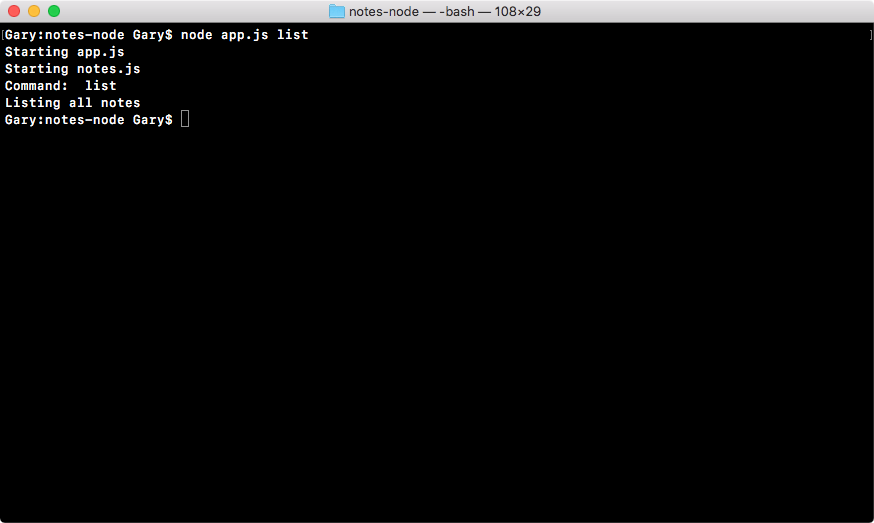

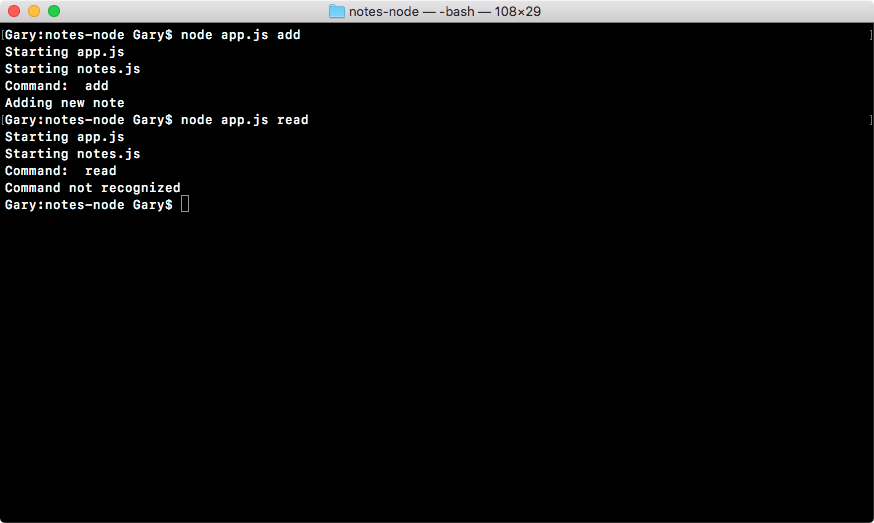

As shown in the preceding code output, we get our two logs. First, we get Starting app.js and then we get Starting notes.js. Now, Starting notes.js comes from the note.js file, and it only runs because we required the file inside of app.js.

Comment out this command line from the app.js file, as shown here:

console.log('Starting app.js');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

// const notes = require('./notes.js');

var user = os.userInfo();

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', `Hello ${user.username}!`);

Save the file, and rerun it from Terminal; you can see the notes.js file never executes because we never explicitly touch it.

We never call it inside Terminal as we do in the preceding example, and we never require.

For now though, we will be requiring it, so I'll uncomment that line.

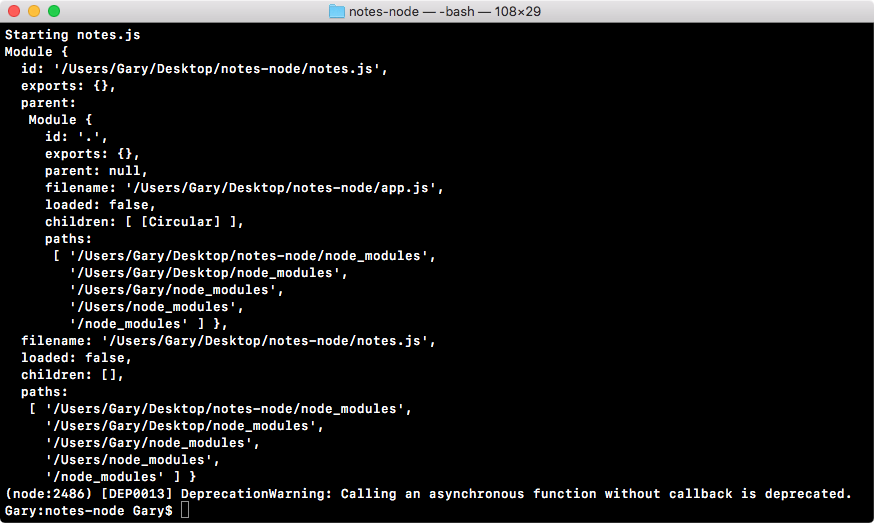

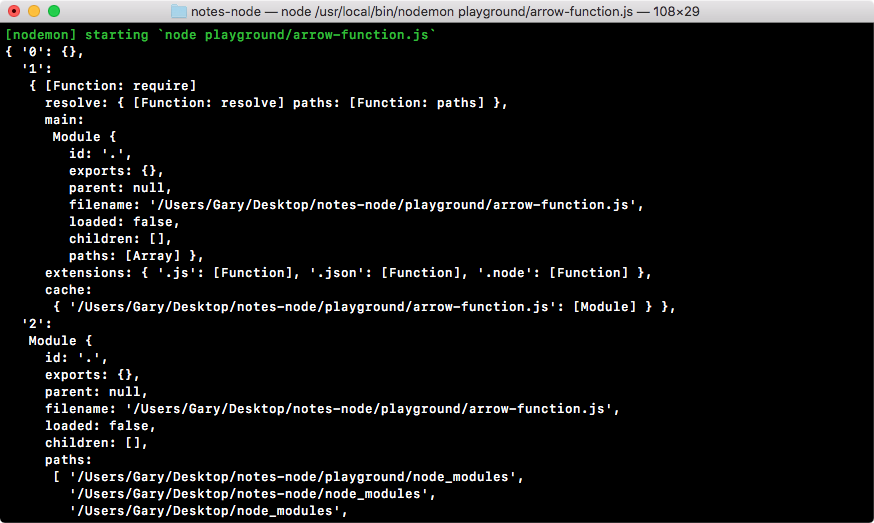

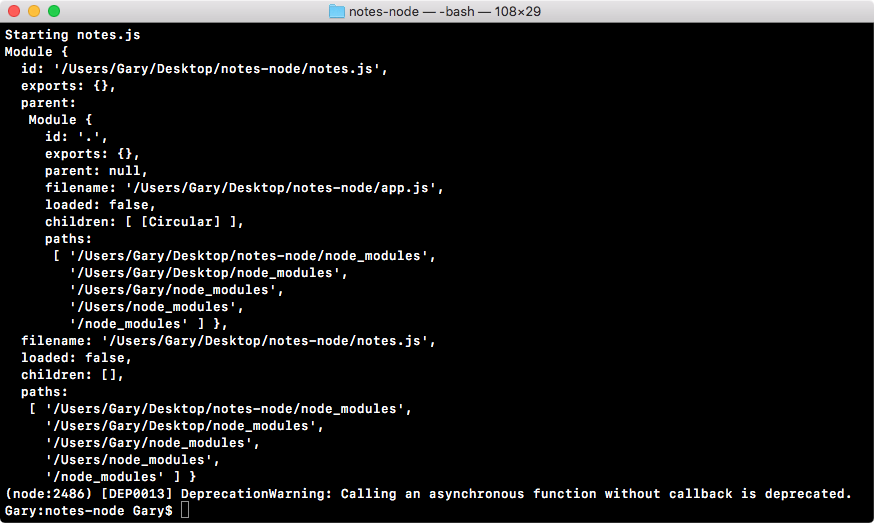

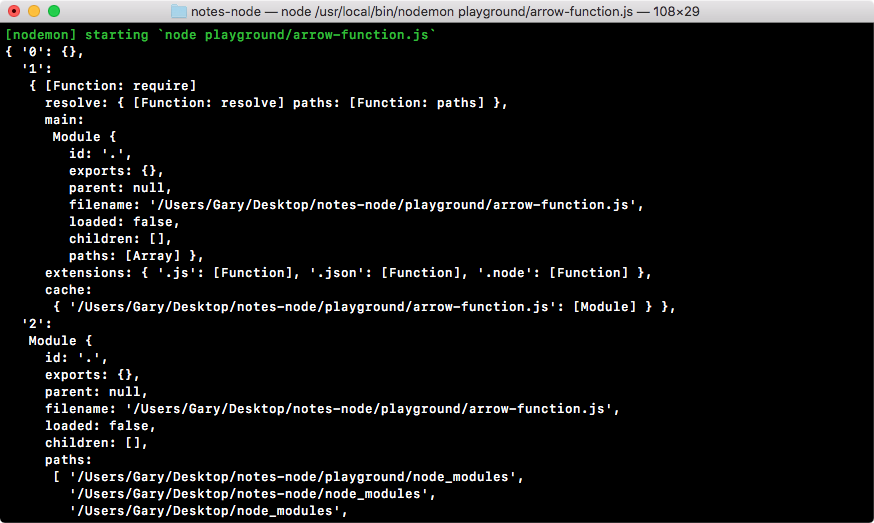

For now though, the focus will be to export something from notes.js which we can use in app.js. Inside notes.js (actually, inside all of our Node files), we have access to a variable called module. I'll use console.log to print module to the screen so that we can explore it over in Terminal, as shown here:

console.log('Starting notes.js');

console.log(module);

Let's rerun the file to explore it. As shown in the following screenshot, we get a pretty big object, that is, different properties related to the notes.js file:

Now, to tell the truth, we'll not be using most of these properties. We have things such as id, exports, parent, and filename. The only one property we'll ever use in this book is exports.

The exports object on the module property and everything on this object gets exported. This object gets set as the const variable, notes. This means that we can set properties on it, they will get set on notes, and we can use them inside app.js.

Let's take a quick look at how that works. What we'll do is to define an age property using module.exports, the object we just explored over in Terminal. Also, we know that it's an object because we can see it in the preceding screenshot (exports: {}); this means that I can add a property, age, and set it equal to my age, which is 25, as shown here:

console.log('Starting notes.js');

module.exports.age = 25;

Then I can save this file and move into app.js to take advantage of this new age property. The const variable notes will be storing all of my exports, in the present case, just age.

In fs.appendFile, after the greeting.txt file, I'll add You are followed by the age. Inside template strings, we will use $ with curly braces, notes.age, and a period at the end, as shown here:

console.log('Starting app.js');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

const notes = require('./notes.js');

var user = os.userInfo();

fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', `Hello ${user.username}! You are ${notes.age}.`);

Now our greeting should say Hello Gary! You are 25. It's getting the 25 value from our separate file (that is, note.js), which is fantastic.

Let's take a quick moment to rerun the program over in Terminal using the up arrow key and enter keys:

Back inside the app, we can open greetings.txt, and as shown in the following screenshot, we have Hello Gary! You are 25:

Using require(), we were able to require a file that we created, and this file stored some properties that were advantageous to the rest of the project.

Now, obviously, the preceding example is pretty contrived. We'll not be exporting static numbers; the real goal of exports is to be able to export functions that get used inside app.js. Let's take a quick moment to export two functions. In the notes.js file, I'll set module.exports.addnote equal to a function; the function keyword followed by opening and closing parentheses, which is followed by the curly braces:

console.log('Starting notes.js');

module.exports.addNote = function () {

}

Now, throughout the course, I'll be using arrow functions where I can, as shown in the preceding code. To convert a regular ES5 function into an arrow function, all you do is remove the function keyword and replace it with an => sign right between the parentheses and the opening curly braces, as shown here:

console.log('Starting notes.js');

module.exports.addNote = () => {

}

For now though, we'll keep things really simple, using console.log to print addNote. This will let us know that the addNote function was called. We'll return a string, 'New note', as shown here:

console.log('Starting notes.js');

module.exports.addNote = () => {

console.log('addNote');

return 'New note';

};

Now, the addNote function is being defined in notes.js, but we can take advantage of it over in app.js.

Let's take a quick second to comment out both the appendFile and user line in app.js:

console.log('Starting app.js');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

const notes = require('./notes.js');

// var user = os.userInfo();

//

// fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', `Hello ${user.username}! You are ${notes.age}.`);

I'll add a variable, call the result, (res for short), and set it equal to the return result from notes.addNote:

console.log('Starting app.js');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

const notes = require('./notes.js');

var res = notes.addNote();

// var user = os.userInfo();

//

// fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', `Hello ${user.username}! You are ${notes.age}.`);

Now, the addNote function is a dummy function for the moment. It doesn't take any arguments and it doesn't actually do anything, so we can call it without any arguments.

Then we'll print the result variable, as shown in the following code, and we would expect the result variable to be equal to the New note string:

console.log('Starting app.js');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

const notes = require('./notes.js');

var res = notes.addNote();

console.log(res);

// var user = os.userInfo();

//

// fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', `Hello ${user.username}! You are ${notes.age}.`);

If I save both of my files (app.js and notes.js) and rerun things from Terminal, you can see that New note prints to the screen at the very end and just before addNote prints:

This means that we successfully required the notes file we called addNote, and its return result was successfully returned to app.js.

Using this exact pattern, we'll be able to define our functions for adding and removing notes over in our notes.js file, but we'll be able to call them anywhere inside of our app, including in app.js.

Now it's time for a quick challenge. What I'd like you to do is make a new function in notes.js called add. This add function will get set on the exports object.

This add function will take two arguments, a and b; it'll add them together and return the result. Then over in app.js, I'd like you to call that add function, passing in two numbers, whatever you like, such as 9 and -2, then print the result to the screen and make sure it works correctly.

So, take a moment, create that add function inside notes.js, call it inside app.js, and make sure the proper result prints to the screen. How'd it go? Hopefully, you were able to make that function and call it from app.js.

The first step in the process will be to define the new function. In notes.js, I'll set module.exports.add equal to that function, as shown here:

console.log('Starting notes.js');

module.exports.addNote = () => {

console.log('addNote');

return 'New note';

};

module.exports.add =

Let's set it equal to an arrow function. If you used a regular function, that is perfectly fine, I just prefer using the arrow function when I can. Also, inside parentheses, we will be getting two arguments, we'll be getting a and b, as shown here:

console.log('Starting notes.js');

module.exports.addNote = () => {

console.log('addNote');

return 'New note';

};

module.exports.add = (a, b) => {

};

All we need to do is return the result, which is really simple. So we'll enter return a + b:

console.log('Starting notes.js');

module.exports.addNote = () => {

console.log('addNote');

return 'New note';

};

module.exports.add = (a, b) => {

return a + b;

};

Now, this was the first part of your challenge, defining a utility function in notes.js; the second part was to actually use it over in app.js.

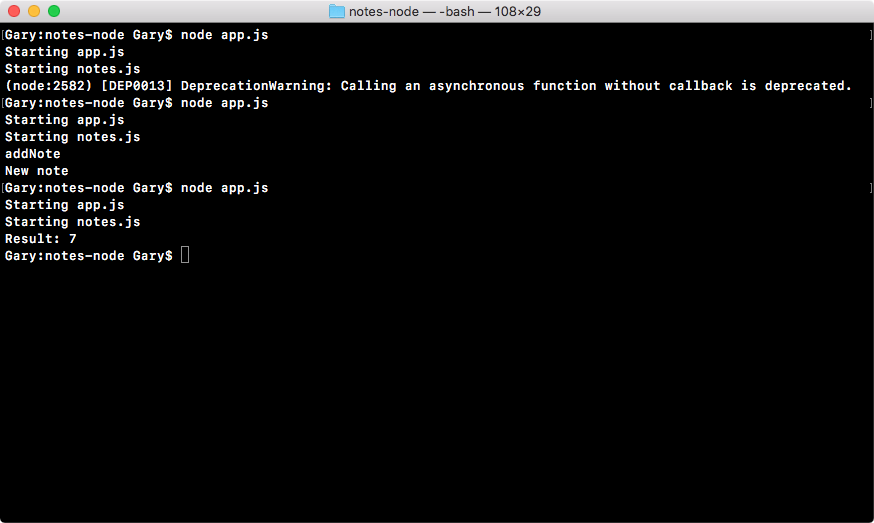

In app.js, we can use our function by printing the console.log result with a colon : (this is just for formatting). As the second argument, we'll print the actual results, notes.add. Then, we'll add up two numbers; we'll add 9 and -2, as shown in this code:

console.log('Starting app.js');

const fs = require('fs');

const os = require('os');

const notes = require('./notes.js');

console.log('Result:', notes.add(9, -2));

// var user = os.userInfo();

//

// fs.appendFile('greetings.txt', `Hello ${user.username}! You are ${notes.age}.`);

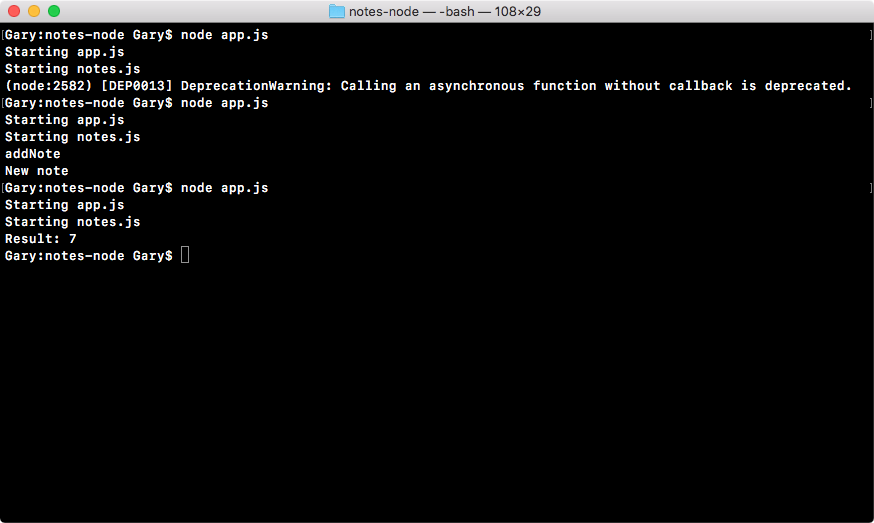

The result in this case should be 7. If we run the program you can see that we get just that, 7 prints to the screen:

If you were able to get this, congratulations, you successfully completed one of your first challenges. These challenges will be sprinkled throughout the book and they'll get progressively more complex. But don't worry, we'll keep the challenges pretty explicit; I'll tell you exactly what I want and exactly how I want it done. Now, you can play around with different ways to do it, the real goal is to just get you writing code independent of following someone else's lead. That is where the real learning happens.

In the next section, we will explore how to use third-party modules. From there, we'll start building the notes application.

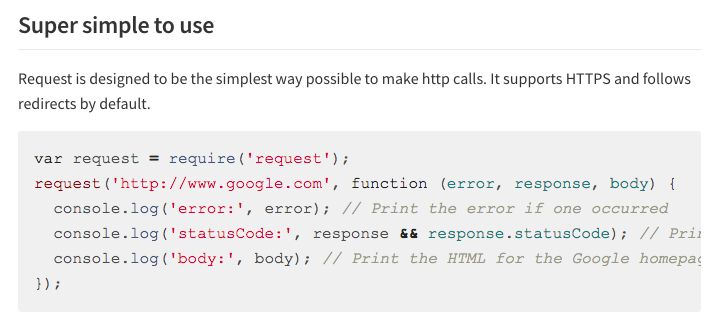

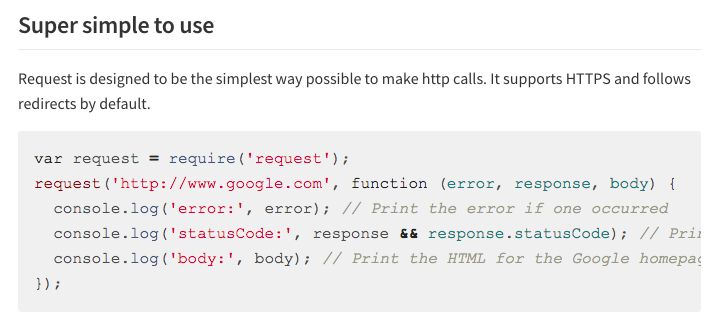

You now know two out of the three ways to use require(), and in this section, we'll explore the last way, which is to require a package you've installed from npm. As I mentioned in the first chapter, npm is a big part of what makes Node so fantastic. There is a huge community of developers that have created thousands of packages that already solve some of the most common problems in Node applications. We will be taking advantage of quite a few packages throughout the book.

Now, in the npm packages, there's nothing magical, it's regular Node code that aims to solve a specific problem. The reason you'd want to use it is so you don't have to spend all your time writing these utility functions that already exist; not only do they exist, they've been tested, they've been proven to work, and others have used them and documented them.

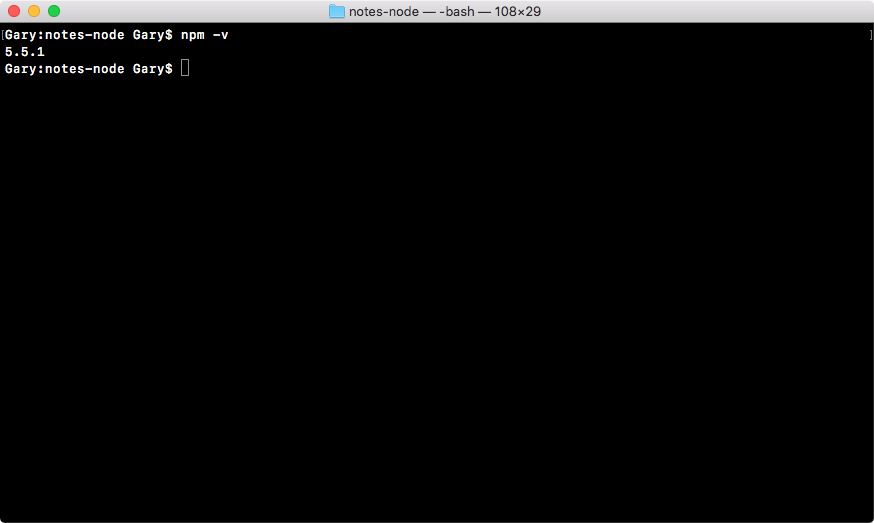

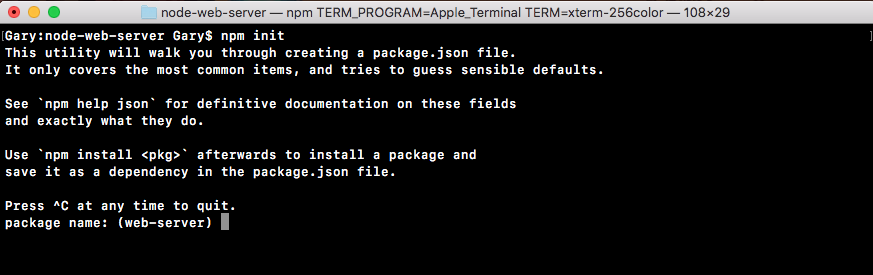

Now, with all that said, how do we get started? Well, to get started, we actually have to run a command from the Terminal to tell our application we want to use npm modules. This command will be run over in the Terminal. Make sure you've navigated inside your project folder and inside the notes-node directory. Now, when you installed Node, you also installed something called npm.

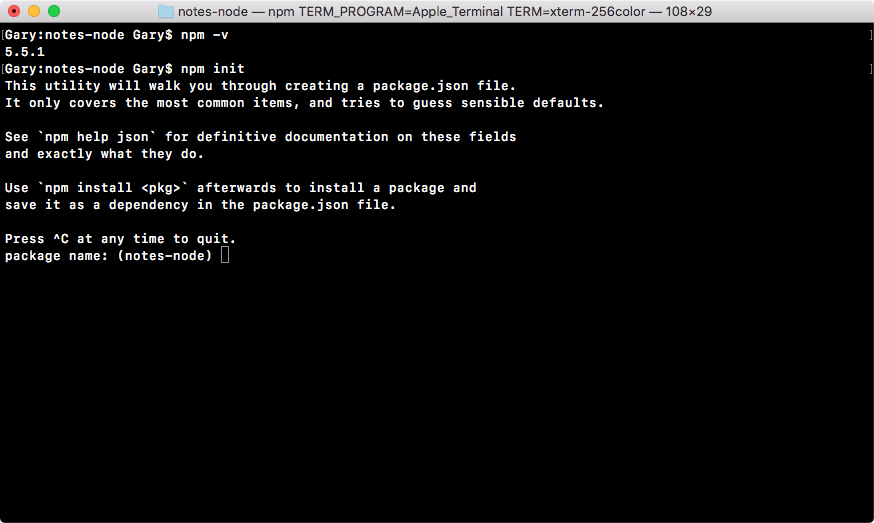

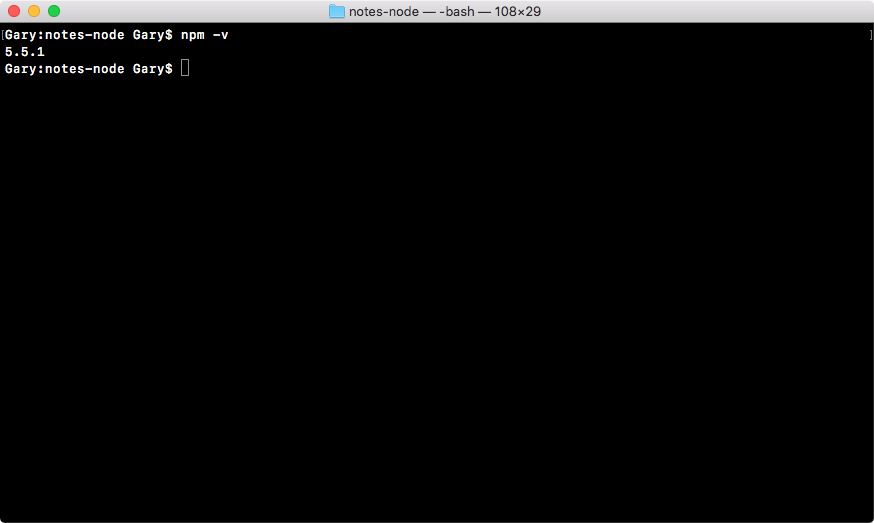

We will be running some npm commands and you can test that you have it installed by running npm, a space, and -v (we're running npm with the v flag). This should print the version, as shown in the following code:

It's okay if your version is slightly different, that's not important; what is important is that you have npm installed.

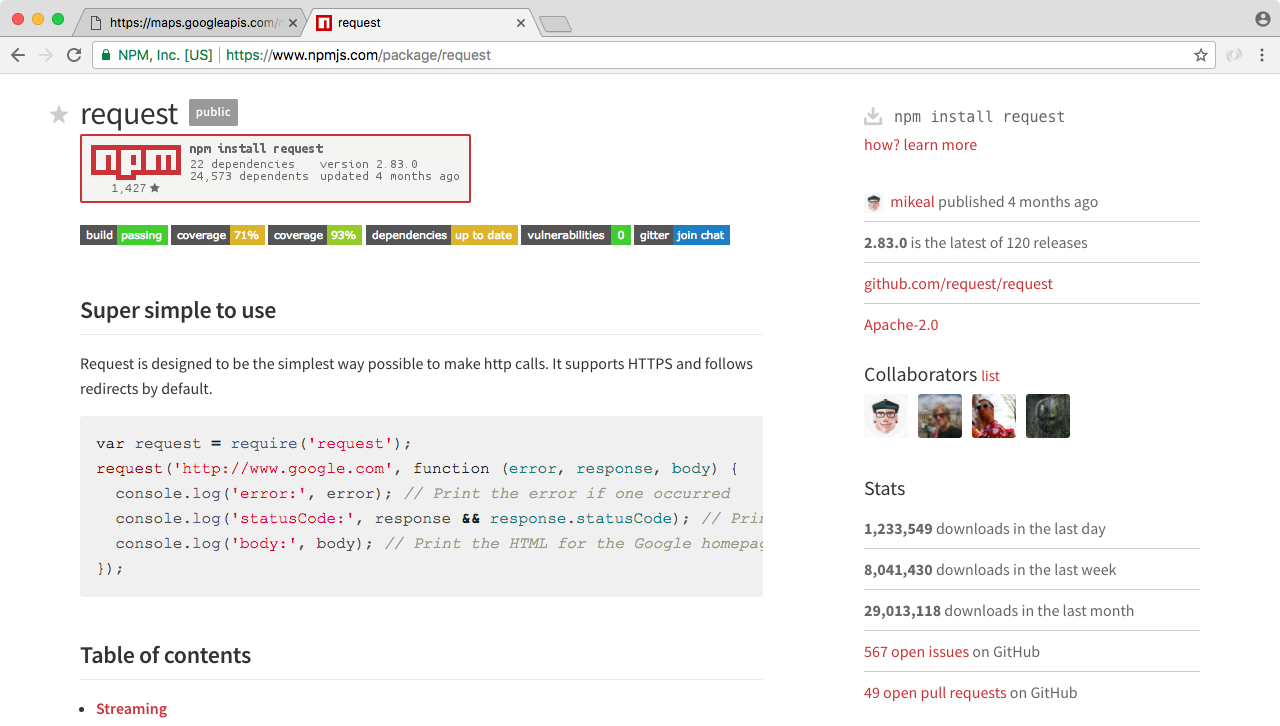

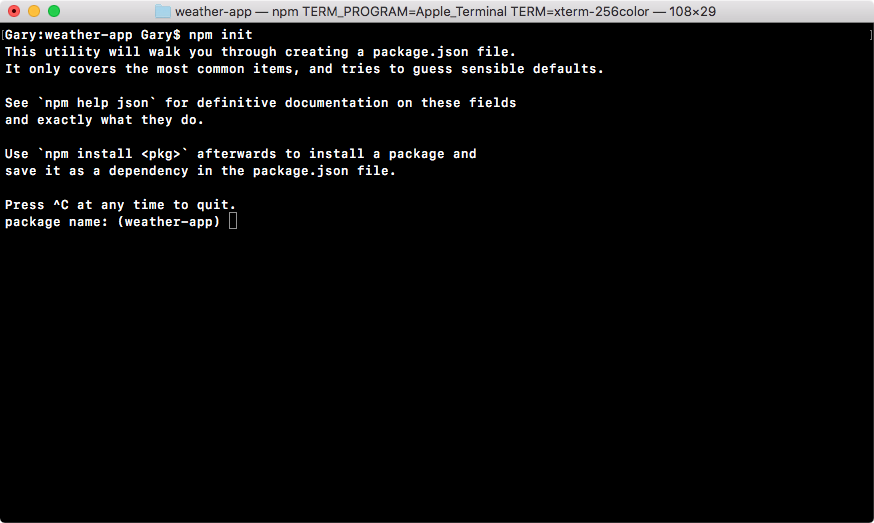

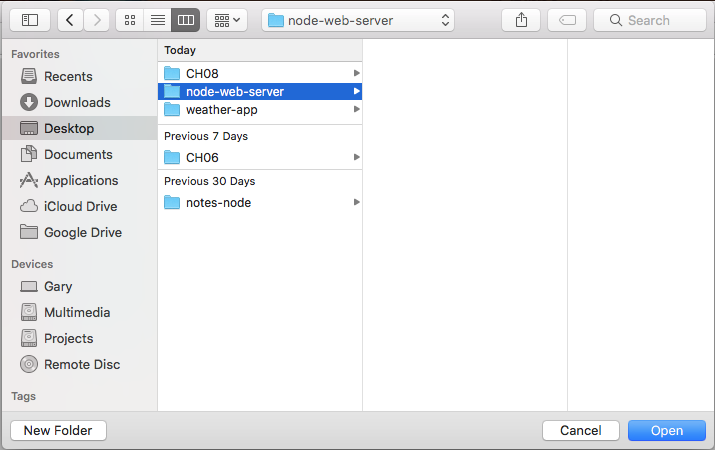

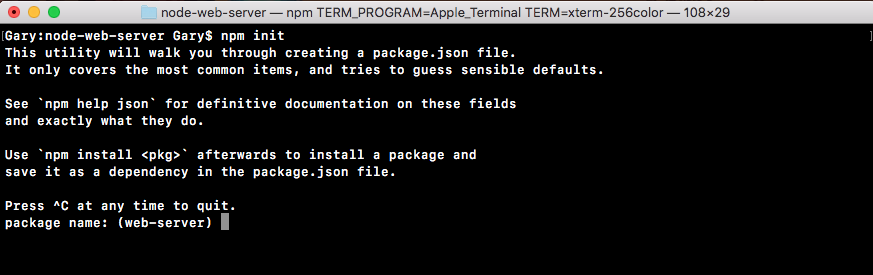

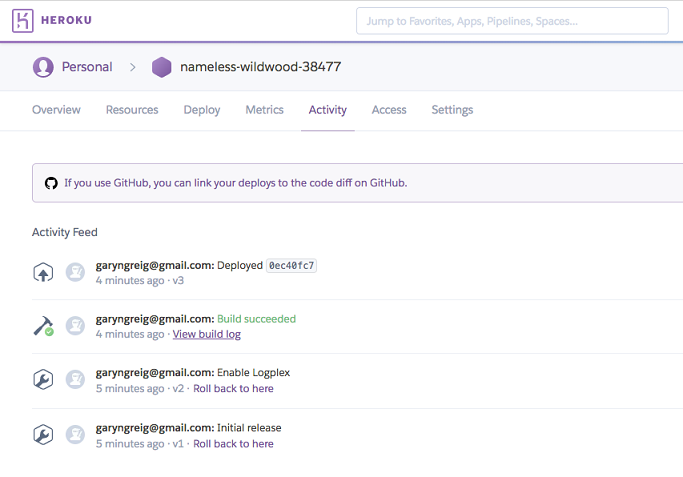

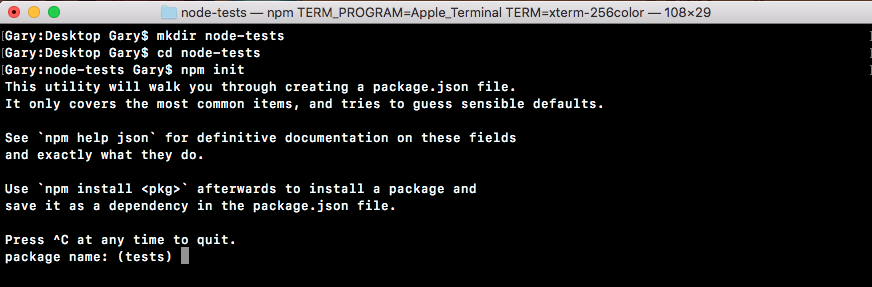

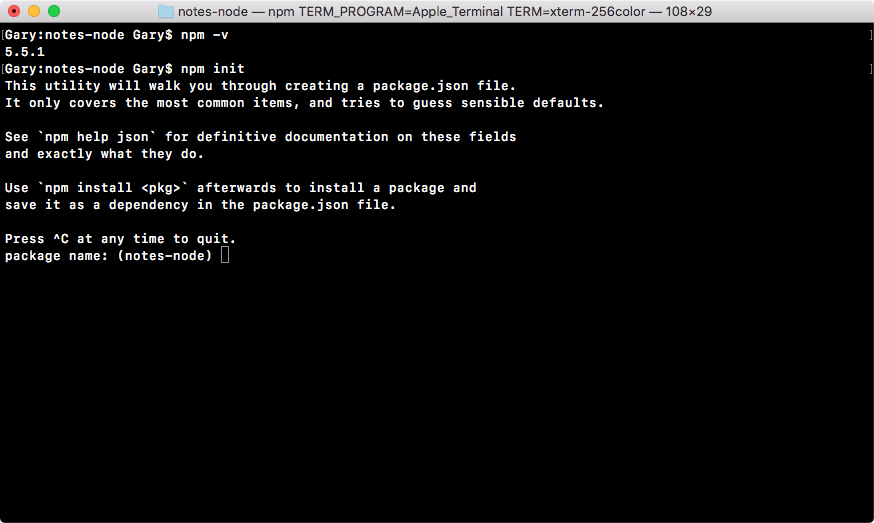

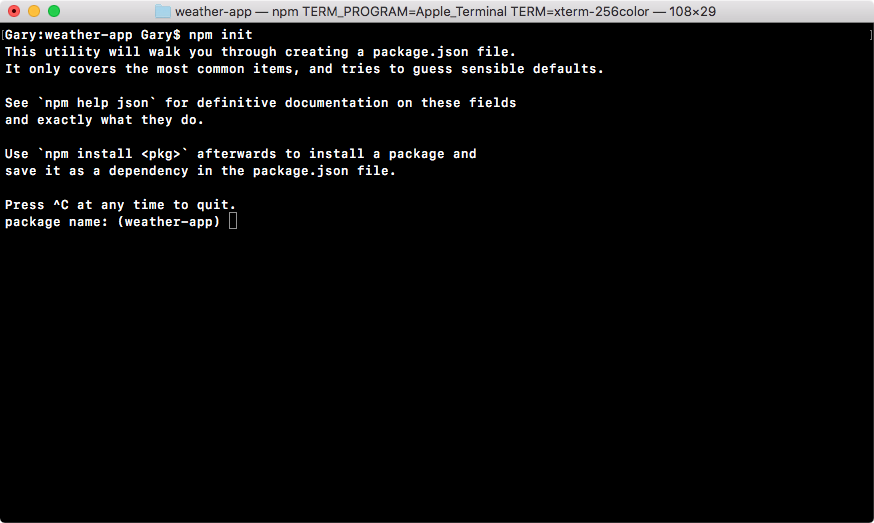

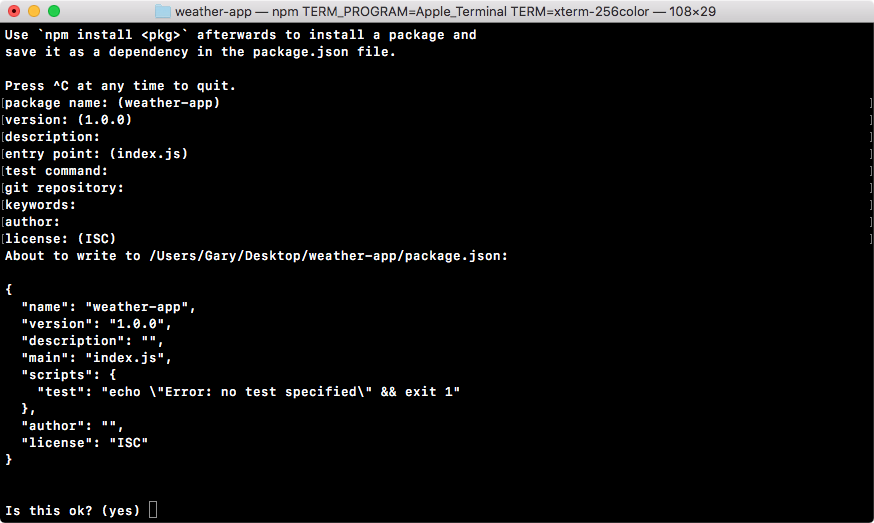

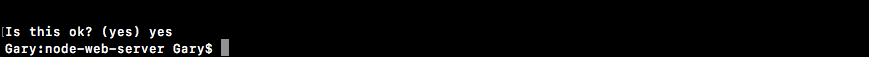

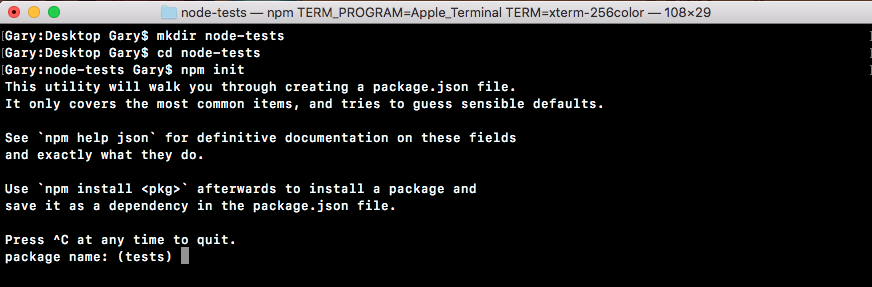

Now, we'll run a command called npm init in Terminal. This command will prompt us to fill out a few questions about our npm project. We can run the command and we can cycle through the questions, as shown in the following screenshot:

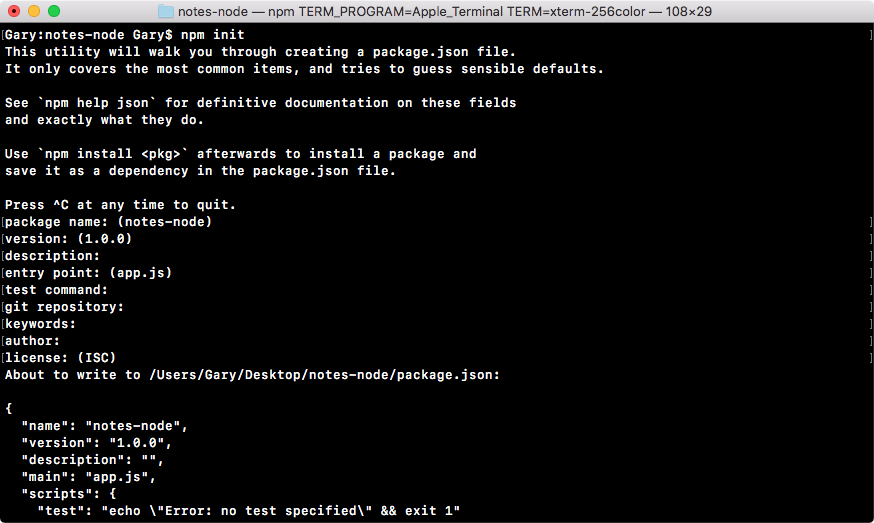

In the preceding screenshot, at the top is a quick description of what's happening, and down below it'll start asking you a few questions, as shown in the following screenshot:

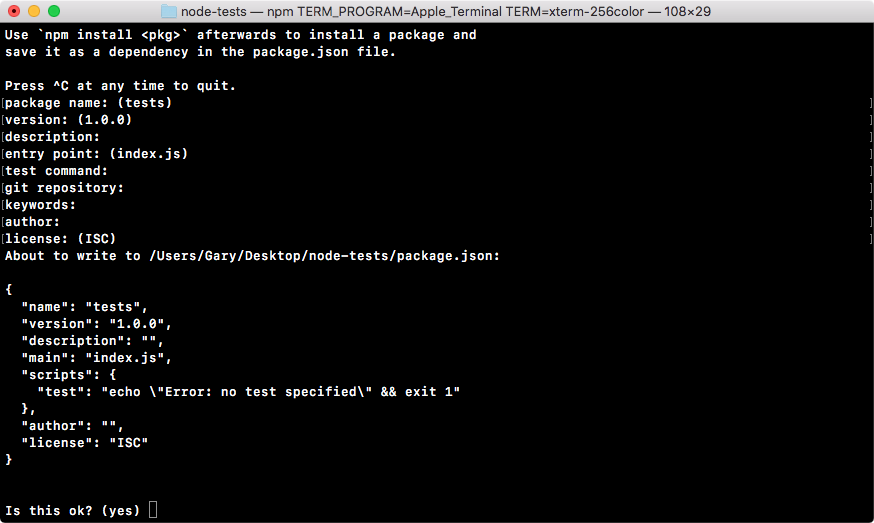

The questions include the following:

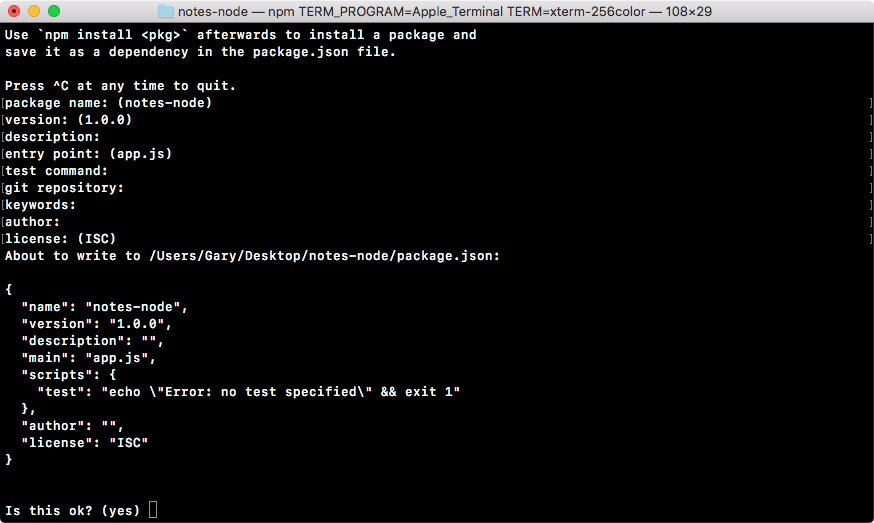

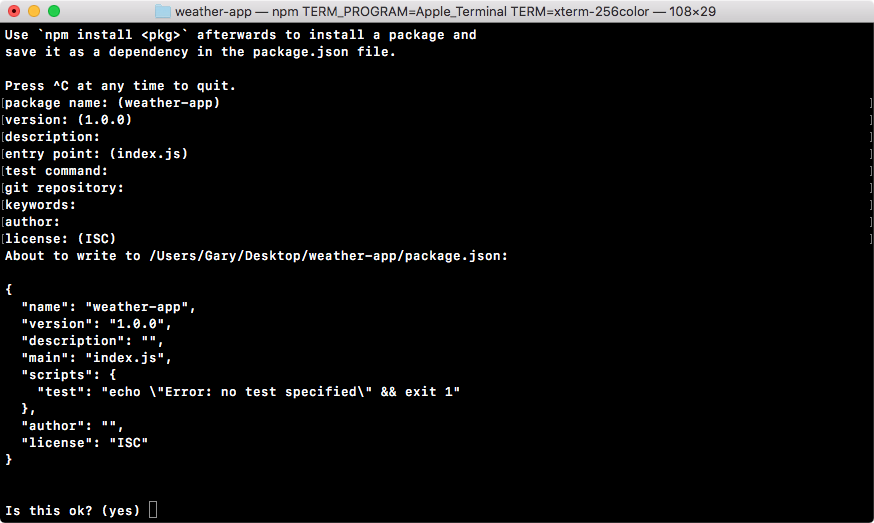

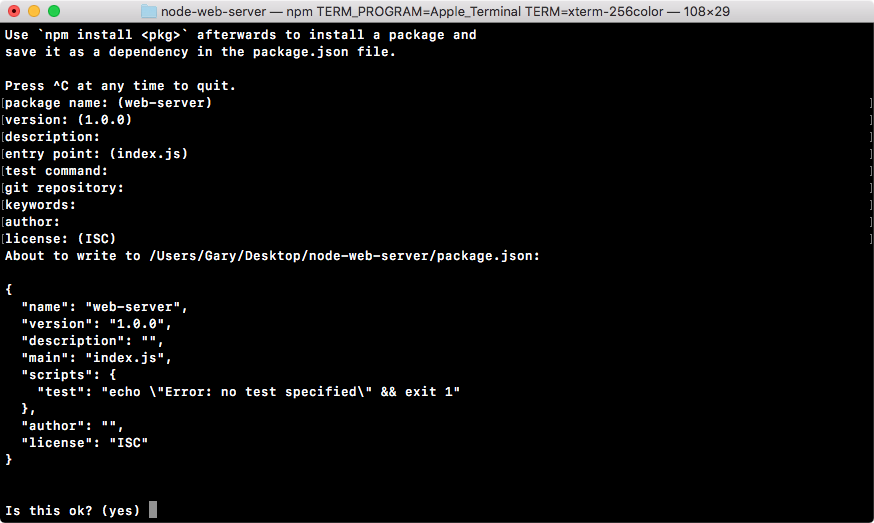

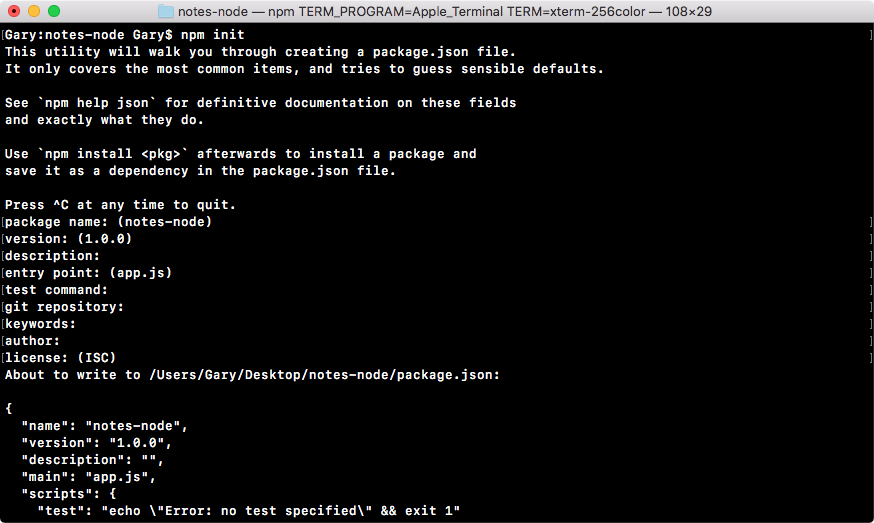

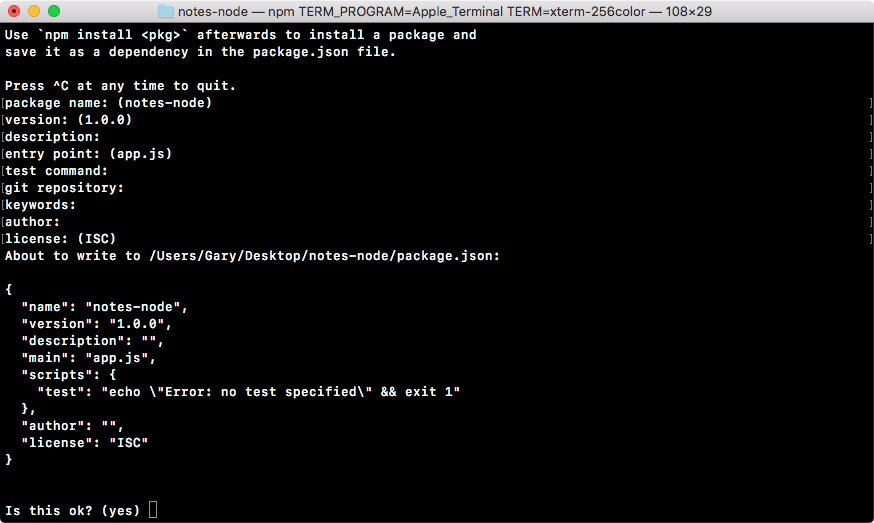

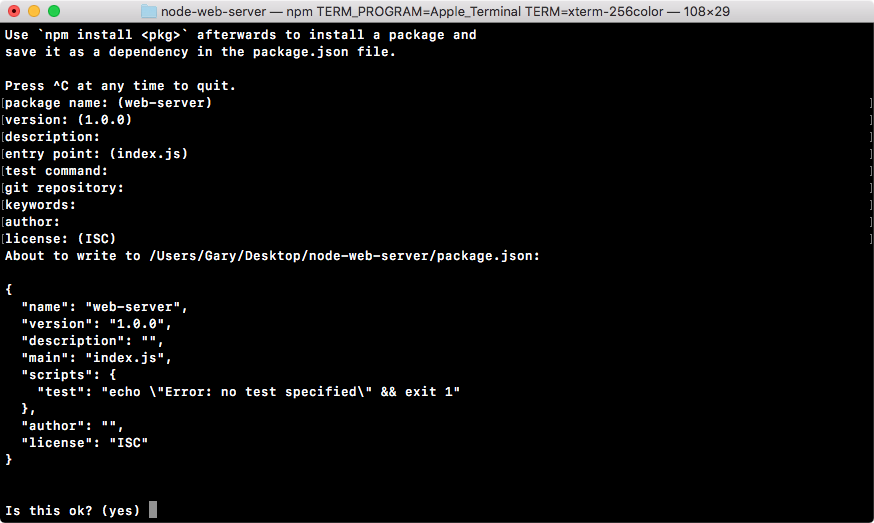

After answering these questions, if we hit enter, we'll get the following on our screen and a final question:

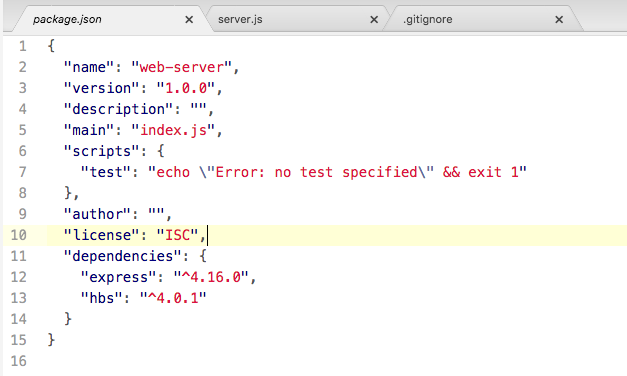

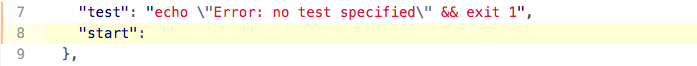

Now, I want to dispel the myth that this command is doing anything magical. All this command is doing is creating a single file inside your project. It'll be in the root of the project and it's called package.json, and the file will look exactly like the preceding screenshot.

To the final question, as shown down below in the preceding image, you can hit enter or type yes to confirm that this is what you want to do:

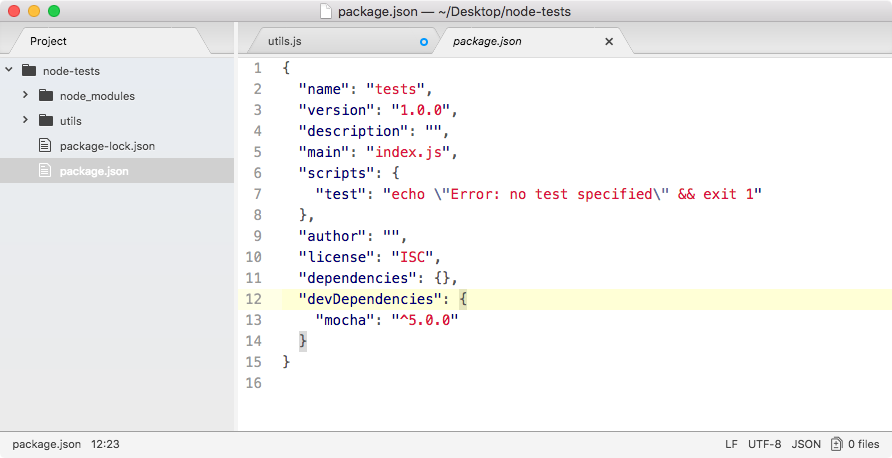

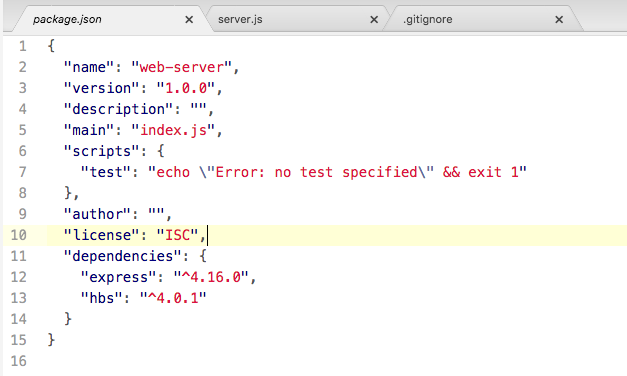

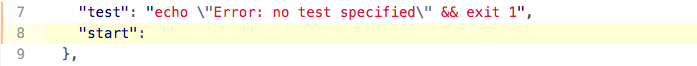

Now that we have created the file, we can actually view it inside our project. As shown in the following code, we have the package.json file:

{

"name": "notes-node",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "",

"main": "app.js",

"scripts": {

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1"

},

"author": "",

"license": "ISC"

}

And this is all it is, it's a simple description of your application. Now, as I mentioned, we'll not be publishing our app to npm, so a lot of this information really isn't important to us. What is important, though, is that package.json is where we define the third-party modules we want to install in our application.

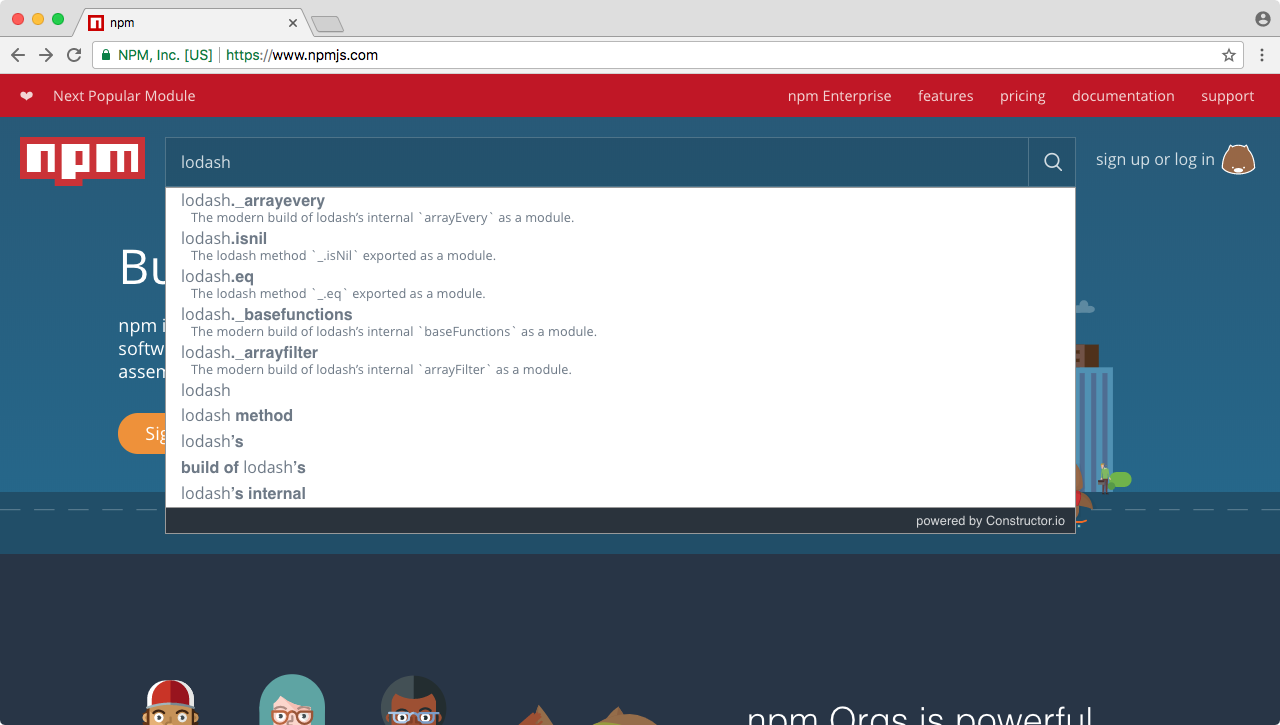

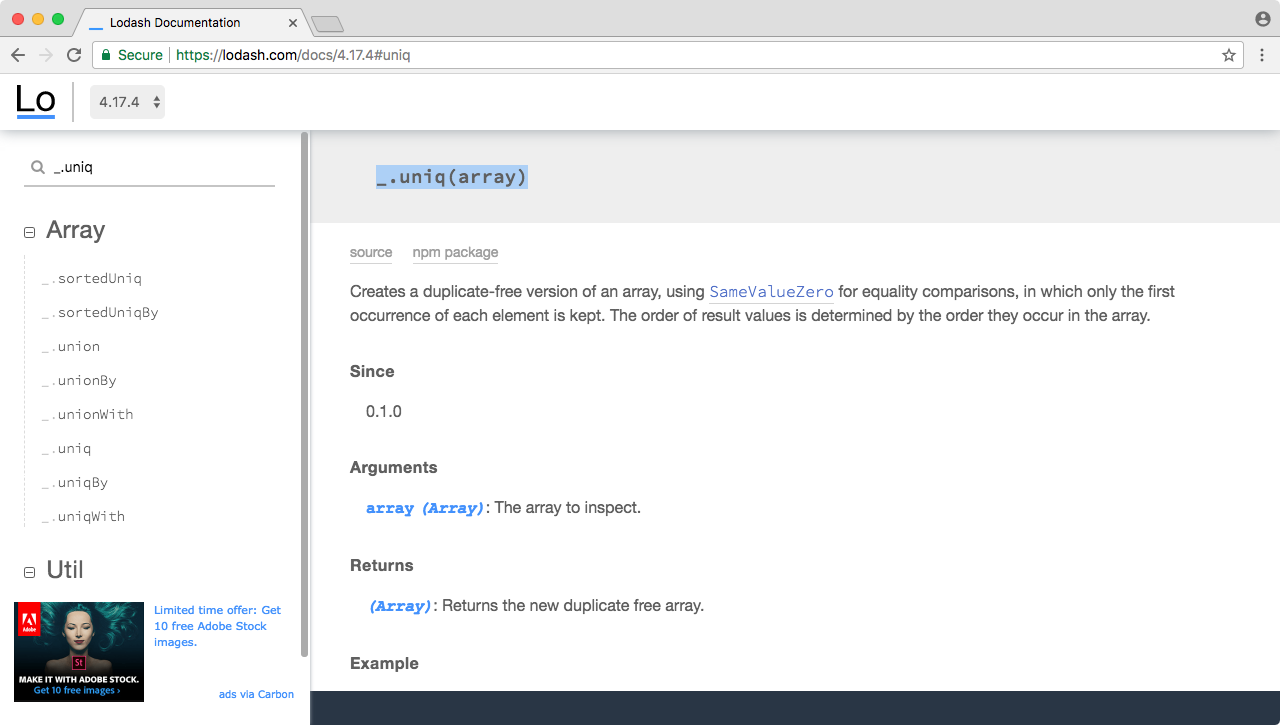

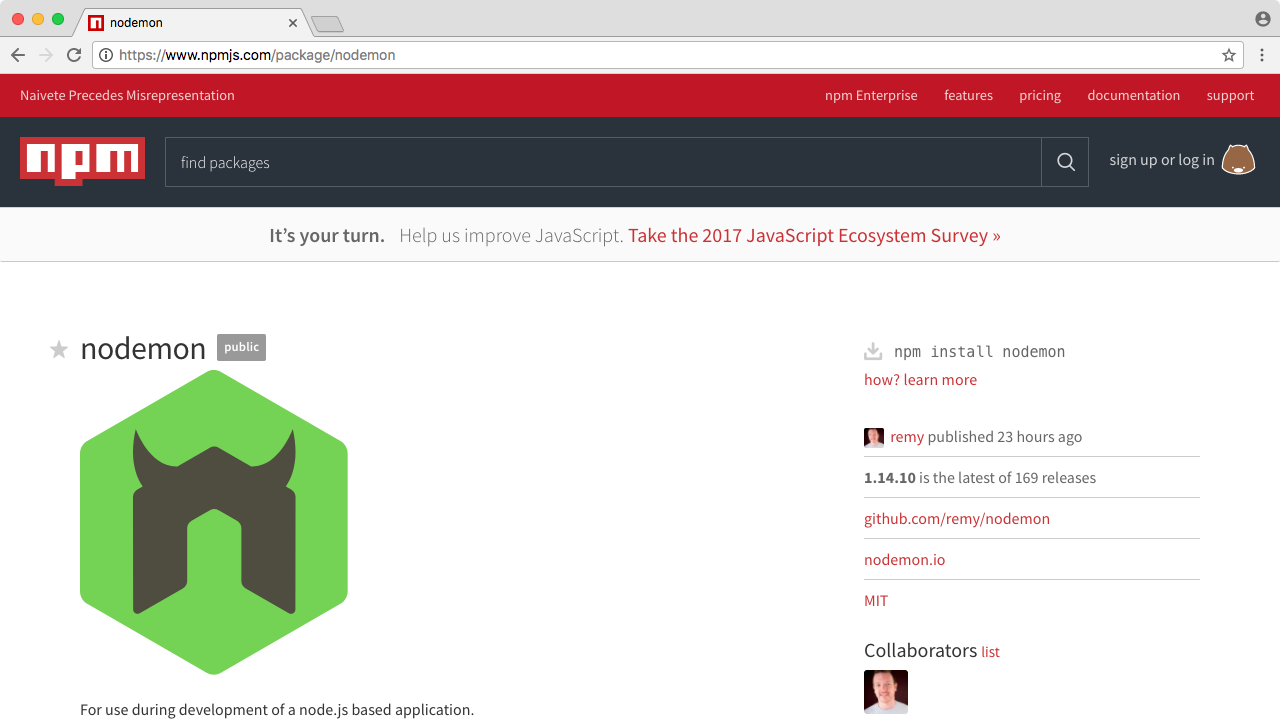

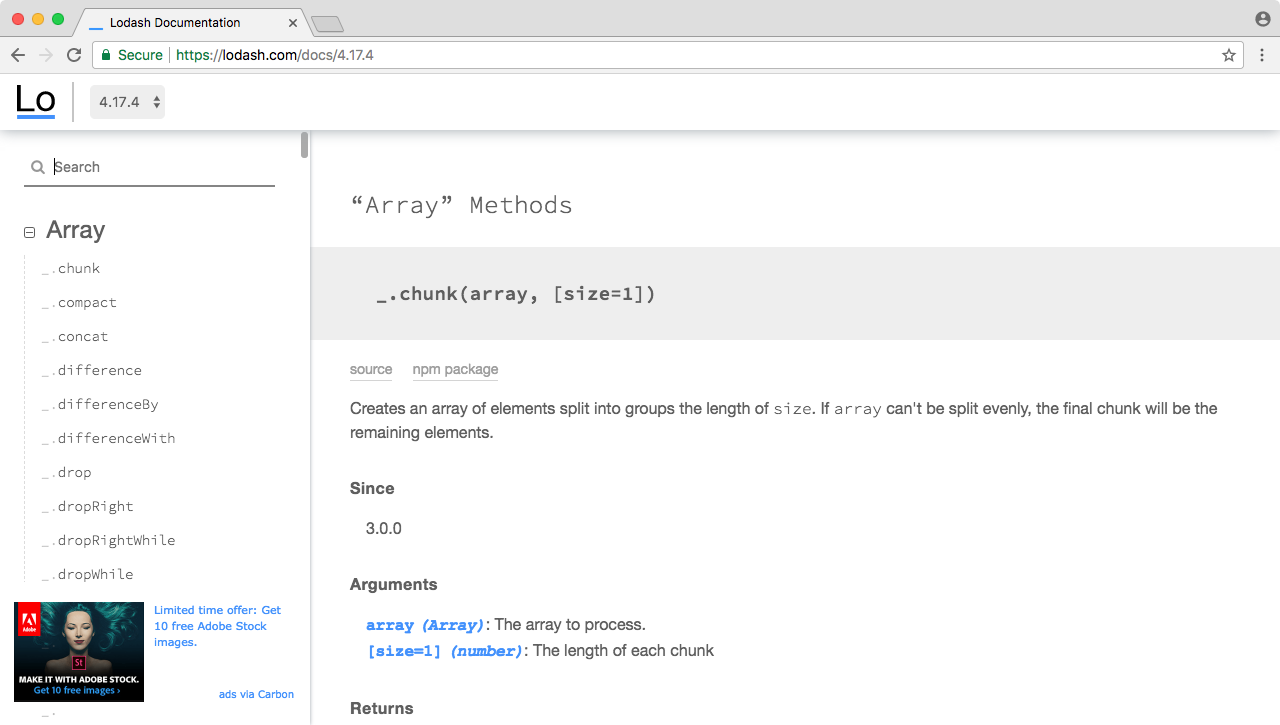

To install a module in the app, we will run a command over in the Terminal. In this chapter, we'll be installing a module called lodash. The lodash module comes with a ton of utility methods and functions that make developing inside Node or JavaScript a heck of a lot easier. To take a look at what exactly we're getting into, let's move into the browser.

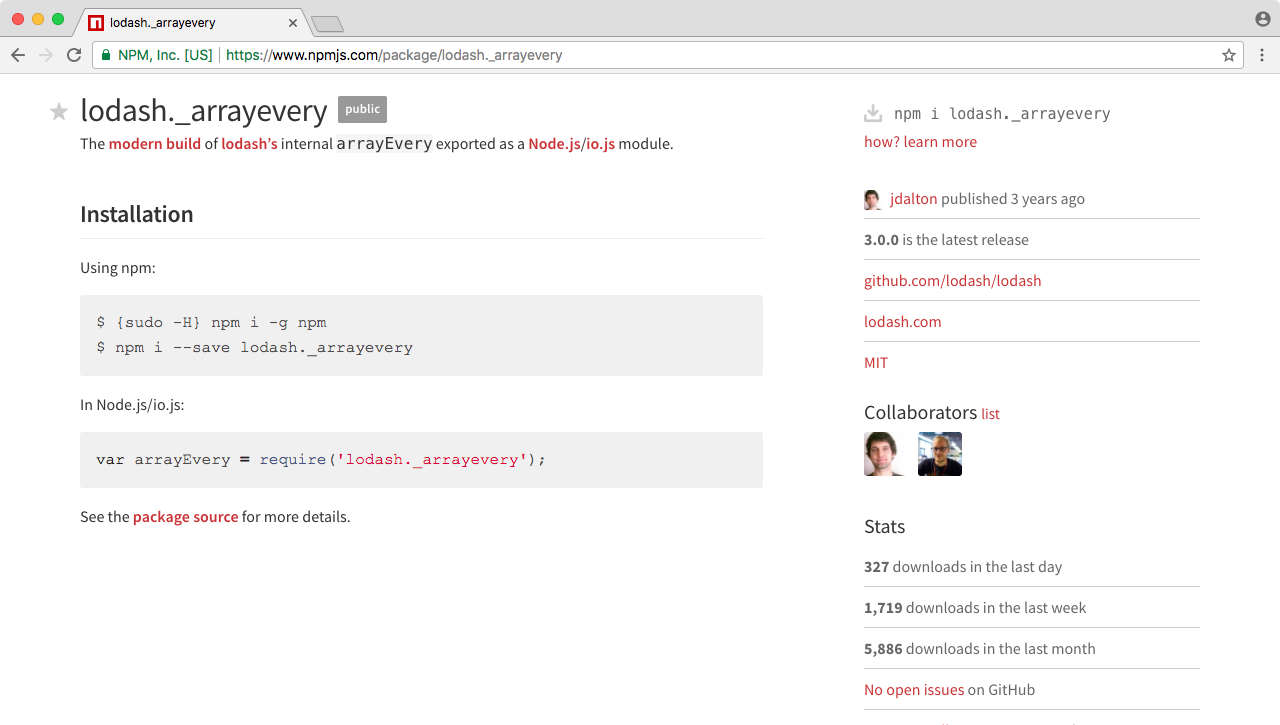

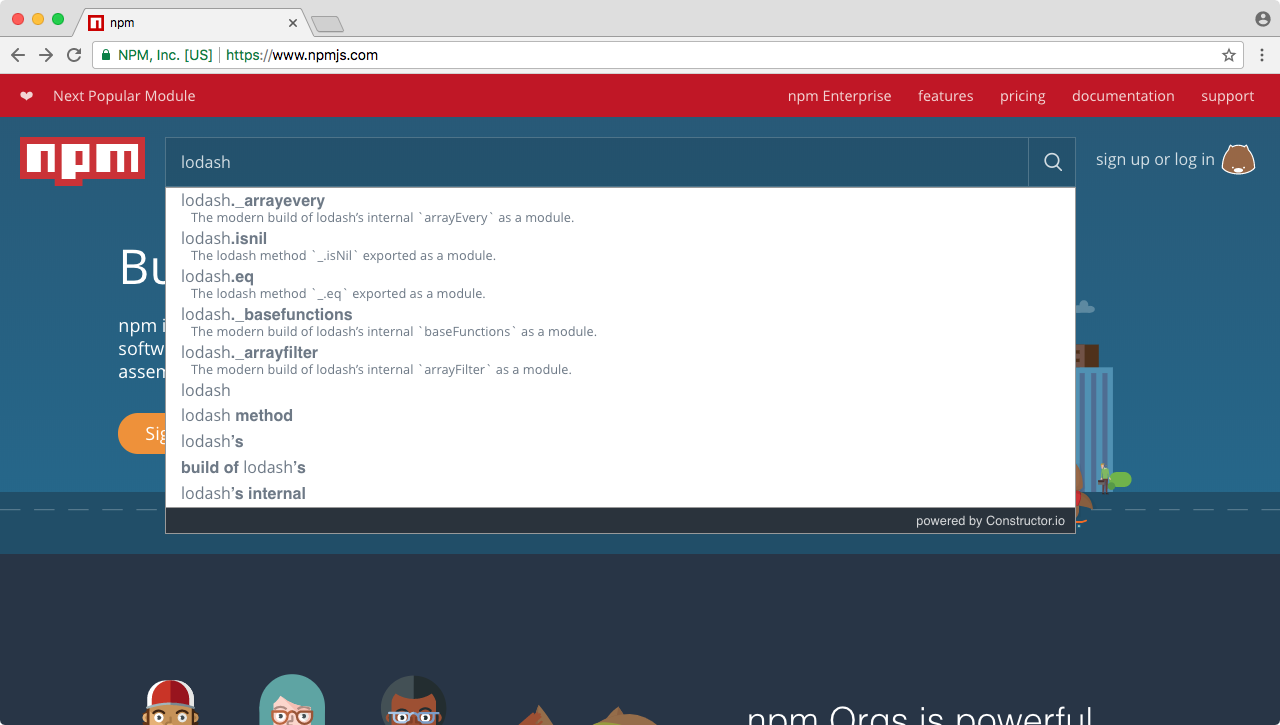

We'll to go to https://www.npmjs.com. Then we'll search for the package, lodash, and you can see it comes up, as shown in the following screenshot:

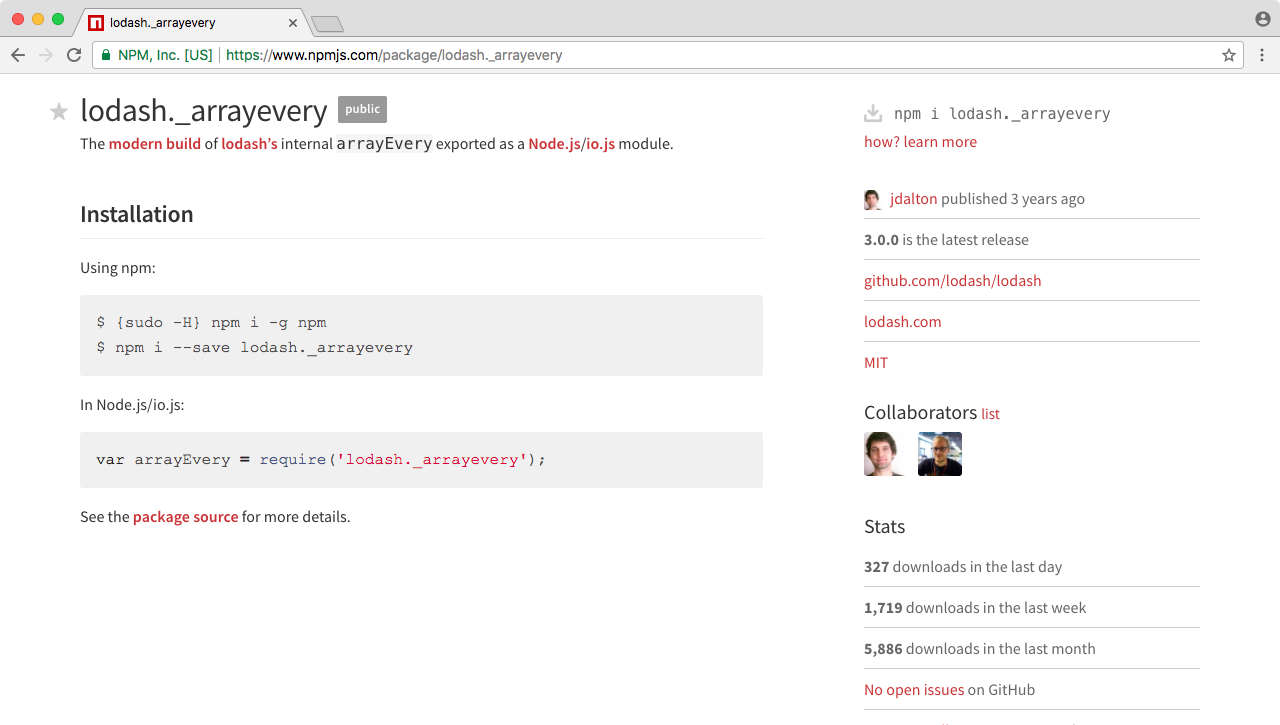

When you click on it, you should be taken to the package page, and the package page will show you a lot of statistics about the module and the documentation, as shown here:

Now, I use the lodash package page when I'm looking for new modules; I like to see how many downloads it has and when it was last updated. On the package page, you can see it was updated recently, which is great it means the package is most likely compatible with the latest versions of Node, and if you go further down the page, you can see this is actually one of the most popular npm packages, with over a million downloads a day. We will be using this module to explore how to install npm modules and how to actually use them in a project.

To install lodash, the first thing you need to grab is just a module name, which is lodash. Once you have that information, you're ready to install it.

Coming to Terminal, we'll run the npm install command. After installing, we'll specify the module, lodash. Now, this command alone would work; what we'll also do, though, is provide the save flag.

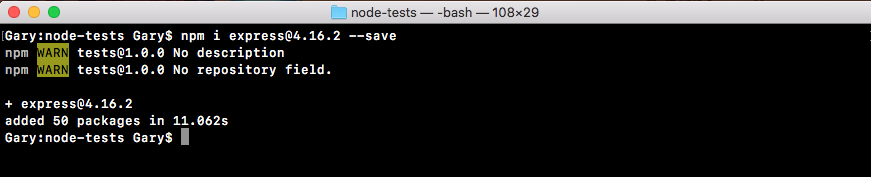

The npm install lodash command will install the module, and the save flag, -- (two) hyphens followed by the word save, will update the contents of the package.json file. Let's run this command:

npm install loadsh --save

The preceding command will go off to the npm servers and fetch the code and install it inside your project, and any time you install an npm module, it'll live in your project in a node_modules folder.

Now, if you open that node_modules folder, you'll see the lodash folder as shown in the following code. This is the module that we just installed:

{

"name": "notes-node",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "",

"main": "app.js",

"scripts": {

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1"

},

"author": "",

"license": "ISC",

"dependencies": {