Before we dive into the body, let's discuss about the response object. We can look at the response object by printing it to the screen. Let's swap out body in the console.log statement for response in the code:

const request = require('request');

request({

url: 'https://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/geocode/json?address=1301%20lombard%20street%20philadelphia',

json: true

}, (error, response, body) => {

console.log(JSON.stringify(response, undefined, 2));

});

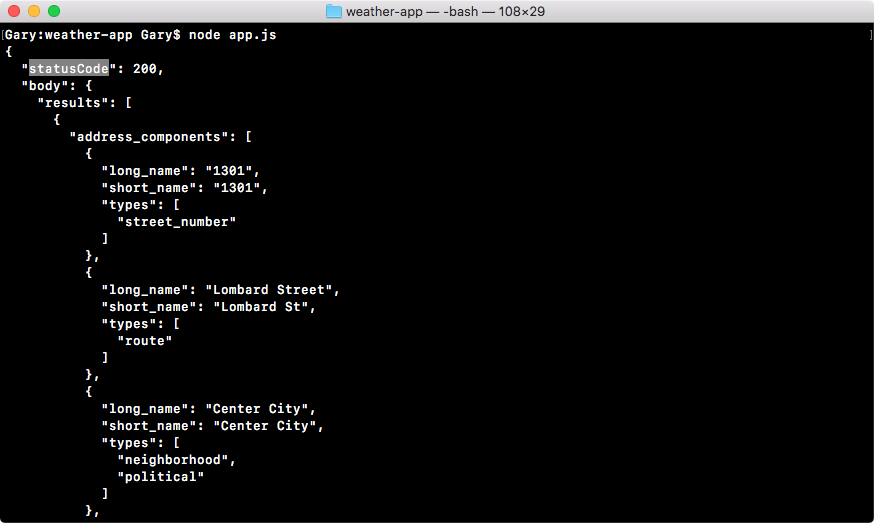

Then save the file and rerun things inside of the Terminal by running the node app.js command. We'll get that little delay while we wait for the request to come back, and then we get a really complex object:

In the preceding screenshot, we can see the first thing we have in the response object is a status code. The status code is something that comes back from an HTTP request; it's a part of the response and tells you exactly how the request went.

In this case, 200 means everything went great, and you're probably familiar with some status codes, like 404 which means the page was not found, or 500 which means the server crashed. There are other body codes we'll be using throughout the book.

In this section, all we care about is that the status code is 200, which means things went well. Next up in the response object, we actually have the body repeated because it is part of the response. Since it's the most useful piece of information that comes back, the request module developers chose to make it the third argument, although you could access it using response.body as you can clearly see in this case. Here, we have all of the information we've already looked at, address components, formatted address geometry, so on.

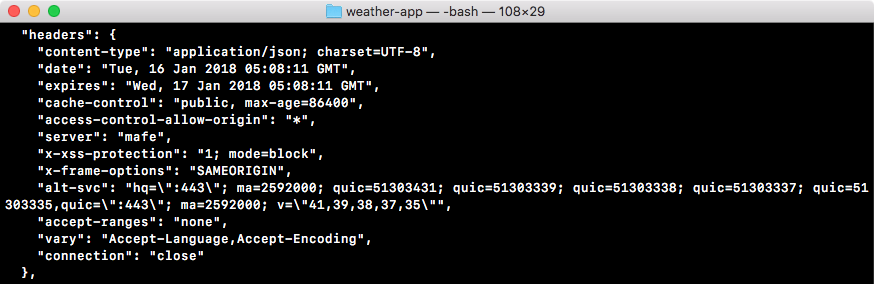

Next to the body argument, we have something called headers, as shown here:

Now, headers are part of the HTTP protocol, they are key-value pairs as you can see in the preceding screenshot, where the key and the value are both strings. They can be sent in the request, from the Node server to the Google API server, and in the response from the Google API server back to the Node server.

Headers are great, there's a lot of built-in ones like content-type. The content-type is HTML for a website, and in our case, it's application/json. We'll talk about headers more in the later chapters. Most of these headers are not important to our application, and most we're never ever going to use. When we go on and create our own API later in the book, we'll be setting our own headers, so we'll be intimately familiar with how these headers work. For now, we can ignore them completely, all I want you to know is that these headers you see are set by Google, they're headers that come back from their servers.

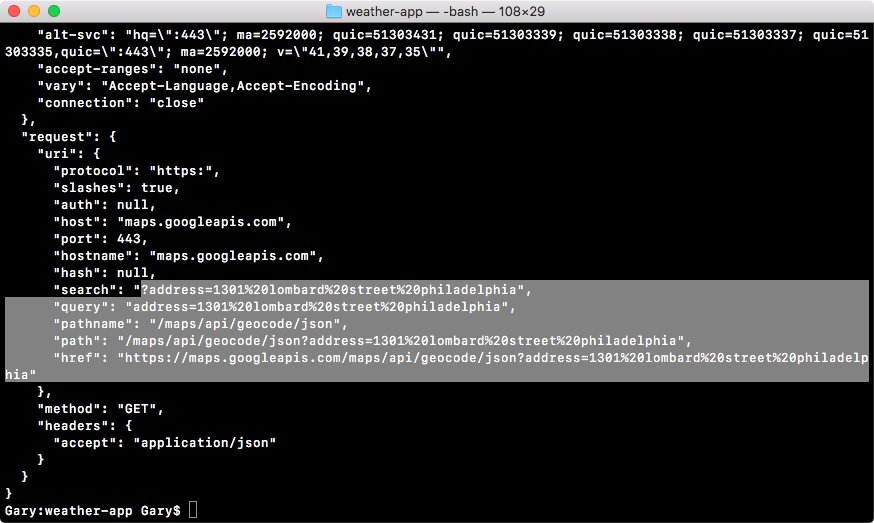

Next to the headers we have the request object, which stores some information about the request that was made:

As shown in the preceding screenshot, you can see the protocol HTTPS, the host, the maps.googleapis.com website, and other things such as the address parameters, the entire URL, and everything else about the request, which is stored in this part.

Next, we also have our own headers. These are headers that were sent from Node to the Google API:

This header got set when we added json: true to options object in our code. We told request we want JSON back and request went on to tell Google, Hey, we want to accept some JSON data back, so if you can work with that format send it back! And that's exactly what Google did.

This is the response object, which stores information about the response and about the request. While we'll not be using most of the things inside the response argument, it is important to know they exist. So if you ever need to access them, you know where they live. We'll use some of this information throughout the book, but as I mentioned earlier, most of it is not necessary.

For the most part, we're going to be accessing the body argument. One thing we will use is the status. In our case it was 200. This will be important when we're making sure that the request was fulfilled successfully. If we can't fetch the location or if we get an error in the status code, we do not want to go on to try to fetch the weather because obviously we don't have the latitude and longitude information.