Now that we know how projections work, let's discuss how should we choose the right projection for our work. We learned before that projections distort reality, as we cannot convert an ellipsoid to a flat surface. Projections have some properties, which are shape, area, direction, distance, scale, and bearing. From these properties, a single projection can only fully preserve a few, at the expense of other properties. Based on the preserved properties, we distinguish between the following types:

- Conformal: Preserves bearings, and shapes locally (still distorts shapes, but it creates the best global approximations). Conformal maps (like Mercator) were life savers back in time, when sailors only had a compass and a map. As it preserves bearing, we can connect two points with a straight line, align our compass, and walk between them based on the bearing. It distorts areas beyond recognition, though.

- Equal-area: Preserves areas, but distorts shapes. It is used for visualizing and analyzing data, where showing areas proportionally is important (such as using indices normalized by area). The Albers is an equal-area projection.

- Azimuthal: Preserves directions. Straight lines represent the shortest routes on the ellipsoid between two arbitrary points, also called great circles.

- Equidistant: Preserves distances from the distortion-free part or parts of the map. From its center, or another distortion-free point, we can measure a straight line, which corresponds to the real distance. This property is not preserved for other pairs of points.

- Compromise: Does not preserve any property, but strives for minimizing errors. Compromise projections are great for global mapping if the map doesn't have to preserve a property.

We did not talk about an important property of projections--scale. Only a few projections preserve scale, most of them distort it. However, the printed and digital maps always show a constant scale, usually with a scale bar. Also, we witnessed during our work that the scale always changes when we pan the map (Plate Carrée does not preserve scale). To overcome this issue, the scale value in these cases is an approximation based on the center of the map (or less often, some kind of average from different parts of it). It simply displays the exact scale in the center, and assumes that we know if our projection preserves or distorts scale to the edges.

Some of the CRSs do not need these kinds of considerations, as they are fitted on a small area. This means that distortions are mostly negligible in their validity extents. If we have a small enough area to map (just like our study area), we can choose such a CRS. For countries too big for an all-purpose CRS, there are multiple ones. There are CRSs to visualize the entire country with different properties, while there are also CRSs for smaller regions giving a better fit.

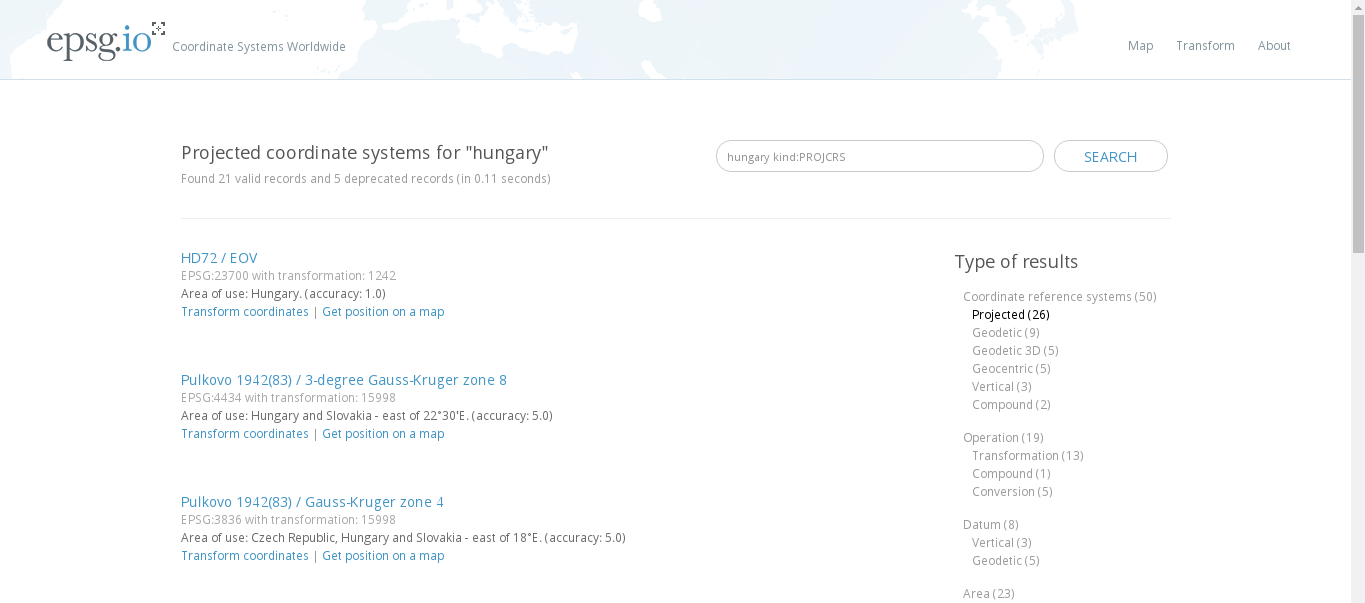

We do not need to know about all the existent CRSs to choose one. There are databases of CRSs which we can browse. The most widely used database is the EPSG (European Petrol Survey Group), which maintains an up-to-date catalogue of all of the popular CRSs. These CRSs identified by their EPSG codes (such as EPSG:4326 for Plate Carrée) are supported by all kinds of GIS software, such as QGIS. Let's select a CRS from an online version of this catalogue at http://epsg.io/. We can type our country's name in the search field, and the site will list all of the projections for our country. We can filter our results to see only projected CRSs (exclude datums) by clicking on Projected on the right-hand side:

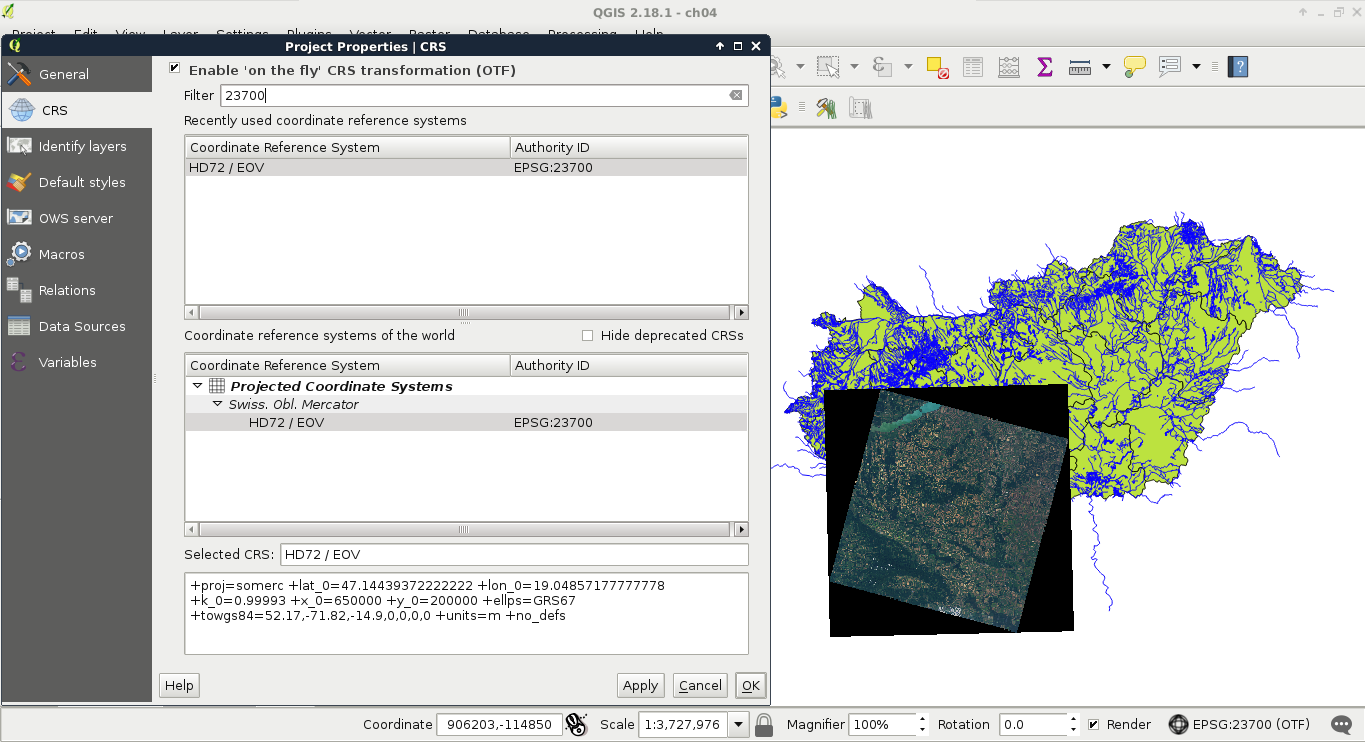

What we have to remember is the EPSG code of our preferred CRS. For example, I will work with EPSG:23700 (HD72 / EOV) from now on. In QGIS, we can change our project's projection in the following way:

- Click on the project's current projection (EPSG:4326).

- In the projection dialog, enable OTF (on-the-fly transformation) by checking in the appropriate check box.

- In the Filter field, type the EPSG code from the online catalogue.

- Select and apply the right CRS from the results:

Let's see the consequences of using a more appropriate projection. If you have multiple projections for the country you are working with, choose a projection for the whole country for now. For this task, we need our administrative boundaries layer. First of all, to access the transformed metrics of our layer, we need to define an ellipsoid for measurements:

- Open Project | Project Properties | General, and select the WGS84 ellipsoid in Measurements | Ellipsoid.

- Open the attribute table of the administrative boundaries layer, and choose the Field Calculator tool.

- Name the updated population density column. I'll use the name pd_correct.

- Choose the Decimal number as a type, and add two decimal places with the Precision field.

- Calculate the column with the formula used in the last chapter ("population" / ($area / 1000000) for SI units).

If we compare the new population density column with the older one, we can see some differences. The farther our country lies from the equator, the bigger the differences are.