One of the greatest perks of GeoServer is its internal tiling and tile-caching capability. It uses GeoWebCache, which is integrated into GeoServer, and enabled by default. Of course, this behavior can be also considered a downside, as cached tiles always use up some disk space. GeoServer's default tiling behavior is dynamic. It creates tiles on demand, and stores them until expiration for reuse. Tiling can greatly increase the speed of serving images, with the expense of additional disk usage. Although there are multiple tiling services served by GeoServer, every one of them can be served with the same tiles (gridset). Only the layout differs, which is calculated by GeoServer before serving the right tiles.

If we go to Data | Layers, and inspect a layer by clicking on its name, we can see the default tiling and tile caching options in the Tile Caching tab. As we can see, tile caching is enabled for two formats (PNG and JPEG) by default. Furthermore, tiles can be generated for two gridsets, one using the EPSG:4326 CRS, and one using the EPSG:9009013 CRS. Finally, tiles can be generated for every style associated with the given layer, which is only the default style by default.

If we go into Tile Caching | Gridsets, we can open the properties of the two enabled gridsets, and check their properties. Gridsets tile up the whole extent of a CRS, and create a layout for every zoom level. They start with only a few tiles for the smallest zoom level, and increase quadratically with every defined new zoom level. If we calculate the theoretic maximum of stored tiles for the EPSG:4326 gridset, we get the value 11,728,124,029,610. For the other gridset, we get a much higher value of 1,537,228,672,809,129,200. These are the number of tiles which can be stored by GeoServer, theoretically, for both of the image formats. According to GeoSolution's presentation at https://www.slideshare.net/geosolutions/geoserver-in-production-we-do-it-here-is-how-foss4g-2016 (they are contributors to the GeoServer project), GeoWebCache's tile storing mechanism is very efficient, as about 58,377 tiles can fit into a single megabyte. Still, to store a layer in both of the default gridsets in a single format, we would need about 24 exabytes of space. I do not think we would need any more proof that managing tile caching is a very good practice, otherwise, GeoWebCache can fill up every bit of free disk space it can use quite quickly.

The first thing we can configure is the disk quota. Despite the large space requirement of tiles, we shouldn't give up on serving tiled variants of WMS images, as they are beneficial if used wisely. We can restrict the space GeoWebCache can take up, and let it create tiles for whatever layers we would like to give a boost. If it reaches its quota, it will free up some space by removing or overwriting unused tiles:

- Go to Tile Caching | Disk Quota.

- Check in the Enable disk quota box.

- Specify an appropriate size for GeoWebCache in the Maximum tile cache size field.

- Select a recycling behavior from the two available options (that is, Least frequently used and Least recently used).

- Apply the disk quota by clicking on Submit.

Now we can deal with the tiled variants of our layers. Despite having a quota, we should not leave GeoWebCache filled with tiles we do not need. We can manage tile layers by going to Data | Layers, opening a layer, and navigating to the Tile Caching tab like we did previously:

- If we would like to disable tile generating for the entire layer, we can uncheck the Create a cached layer for this layer option.

- If we would like to disable only caching tiles for a layer, we can uncheck the Enable tile caching for this layer option.

- We can disable the image/jpeg format for every layer safely. The usual image format we use on the web is PNG, as it can store transparency. By using JPEG, we get smaller image sizes, but we also get a white background where there aren't any features.

- We can also remove unused gridsets from layers with the red minus button. For the gridsets that we would like to use, we can define the minimum and maximum zoom levels we would like to publish or cache.

As our GeoServer is not public, do not bother with the tile setup for now. Let's create a tiled variant for our new layer group in our local projection instead:

- Go to Tile Caching | Gridsets.

- Select the Create a new gridset option.

- Name the gridset to represent the local projection we use. Avoid using special characters, whitespaces, or slashes.

- Supply the EPSG code of the local projection in the Coordinate Reference System field.

- Click on Compute from maximum extent of CRS to make GeoServer calculate the bounding box of the gridset automatically.

- Click on Add zoom level as many times as the zoom levels we would like to provide. Create at least 10 zoom levels. The optimal number of zoom levels highly depends on the size of the CRS's extent. You can take a hint from the Scale column of the zoom levels. A scale of 1:500 is building level.

- Save the new gridset with the Save button.

- Navigate to Data | Layer Groups, and select our layer group from the list. This is the same as selecting the layer group from the layers list, but more convenient.

- Go to the Tile Caching tab, and add our new gridset by selecting it in the Add grid subset field, and clicking on the green plus button.

- Save the edits made to the layer group.

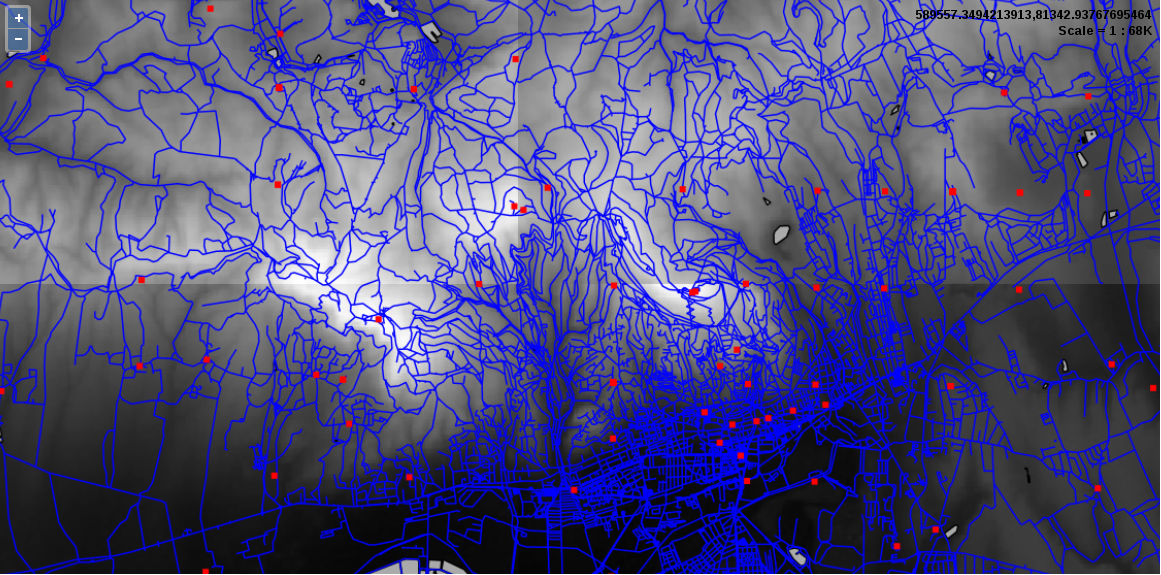

Now we can preview the tiled version of our layer group in our CRS by navigating to Tile Caching | Tile Layers, finding the row of our group layer, and selecting the appropriate gridset and format combination from its Preview column:

We can instantly see the greatest benefit of using tiled layers when we browse the preview. The first time when we pan or zoom around, GeoServer takes some time to render the tiles. Then, if we navigate to already visited areas, it loads the content instantly. If we navigate to Tile Caching | Disk Quota, we can also see our disk slowly filling up by browsing the preview. You may ask now: where are the tiles? They are stored in GeoServer's data_dir/gwc folder. Tiling provided by GeoWebCache does not only mean that a separate module does tile providing and caching; it also means that we can only request tiled resources from a third endpoint--gwc:

http://localhost:8080/geoserver/gwc

As GeoServer provides various tiling services from which only WMTS is an OGC standard (therefore, has similar parameters to WMS, WFS, and WCS providers), tile requests are slightly different. We have to specify the service in the path of the URL, and can use service-related parameters after that. For example, to query the WMTS capabilities of our GeoServer, we can use the following URL:

http://localhost:8080/geoserver/gwc/service/wmts?

Version=1.0.0&Request=GetCapabilities