The only question that remains is; how can spatial data be inserted into this architecture? Well, they can be stored as static resources in vector formats like KML or GeoJSON. The browser can read the content of these structured text files, and client-side web mapping software can use them. Publishing raster layers is a little more tricky. As web browsers do not have a concept about raster data, they need those layers as regular images. Therefore, we have to create a representation model on the server side, and send the resulting images to the client. The usual way of storing pre-rendered raster layers is to tile them, and serve the tiles. Then, if the client-side web mapping software knows the tiling scheme, it can create an interactive map by requesting visible tiles, and sewing them together. For this, we need to create tiles for various zoom levels (fixed scales) for the entire extent of our raster layer. In order to improve compatibility, there are various open source tiling standards. Two of the more popular standards are OpenStreetMap's slippy map, and OSGeo's TMS (tile map service).

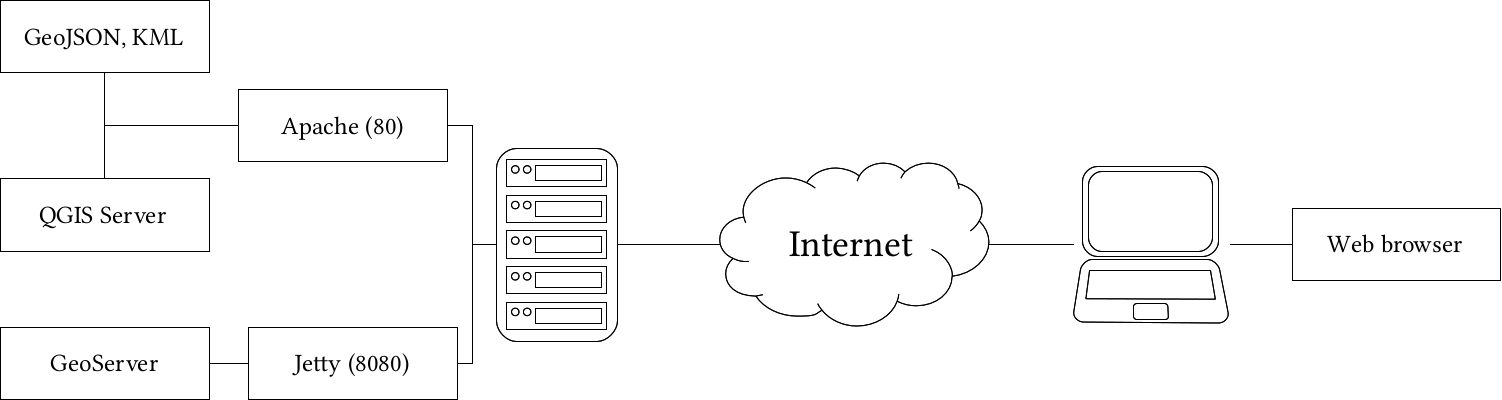

The other way to serve maps is, of course, via a CGI application. QGIS Server, for example, is a completely valid CGI application we can use with any web server. By sending parameters in a URL, we can get an image containing the requested layers rendered by QGIS Server on the fly. To make this concept a little bit more complex, there is also GeoServer, which is written in Java. Java is an exceptional language for writing web applications, as web servers cannot invoke those software directly as CGI scripts. In order to use a Java web application, we need a Java servlet, which is a specialized web server for running it. The platform-independent binary version of GeoServer is bundled with Jetty, a lightweight Java servlet listening on port 8080:

Using spatial servers instead of static files has a lot of advantages. For example, spatial servers can read out layers from spatial databases, therefore, we can always provide up-to-date data. We can also send only extracts of large datasets querying them by various means, or reproject them on the fly. As spatial servers need to be invoked by using some parameters, their interfaces are also standardized. Most of those standards are also maintained by experts and organizations forming the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC). They define interfaces, that is, the communication between web clients and spatial servers. From the various OGC standards, there are some targeting the web. They are called Open Web Services (OWS), and define general spatial data transmission over the web. These standards are as follows:

- Web Map Service (WMS): Layers rendered on the server side, and returned to the client as regular images.

- Web Map Tile Service (WMTS): Layers rendered, tiled, and cached on the server side. Tiles are returned to the client.

- Web Feature Service (WFS): Vector layers sent to the client as structured text. By default, WFS uses the GML vector format.

- Web Coverage Service (WCS): Raster layers sent to the client as raw raster data. It is used by desktop GIS clients capable of reading raw raster data (for example, QGIS), therefore, we won't discuss it further.

While OWS standards allow communicating through GET and POST requests, both QGIS Server and GeoServer are mainly used with GET requests, therefore, parameterized URLs. There are some common parameters for every service, which are listed as follows:

- Service: The abbreviation of the requested service. It can be WMS, WMTS, WFS, or WCS.

- Version: The version of the requested service, as spatial servers can provide data using different versions for backward compatibility. For WMS, it is usually 1.3.0; 1.1.0, 2.0, and 2.0.2 are widely used for WFS, while for WMTS, it is 1.0.

- Request: The type of the operation that the spatial server should perform. A common value is GetCapabilities, which requests the metadata of the provided layers used with the requested service. For WMS, it is usually GetMap, for WFS it is GetFeature, while for WMTS, it is usually GetTile.

If we put this together, we can craft an URL, which can query a spatial server's WMS capabilities the following way:

http://mysite.com/spatialserver?

Service=WMS&Version=1.3.0&Request=GetCapabilities