The first task in Chapter 8, Spatial Analysis in QGIS was to select every house which is at least 200 meters away from busy roads and 500 meters away from industrial areas. To complete this task, we created buffer zones around the problematic features and areas, calculated their union, and selected every disjoint house. Following the same approach, we can use two functions of PostGIS--ST_Intersects and ST_Buffer. We do not have to discuss ST_Intersects again, as we have already used it several times. ST_Buffer, on the other hand, is a different function. It does not act as a filtering function, but it creates and returns new geometries based on the input geometries and buffer distances. To buffer the busy roads of our roads layer, we can create the following expression:

SELECT ST_Buffer(geom, 200) AS geom

FROM spatial.roads r

WHERE r.fclass LIKE 'motorway%' OR r.fclass LIKE 'primary%';

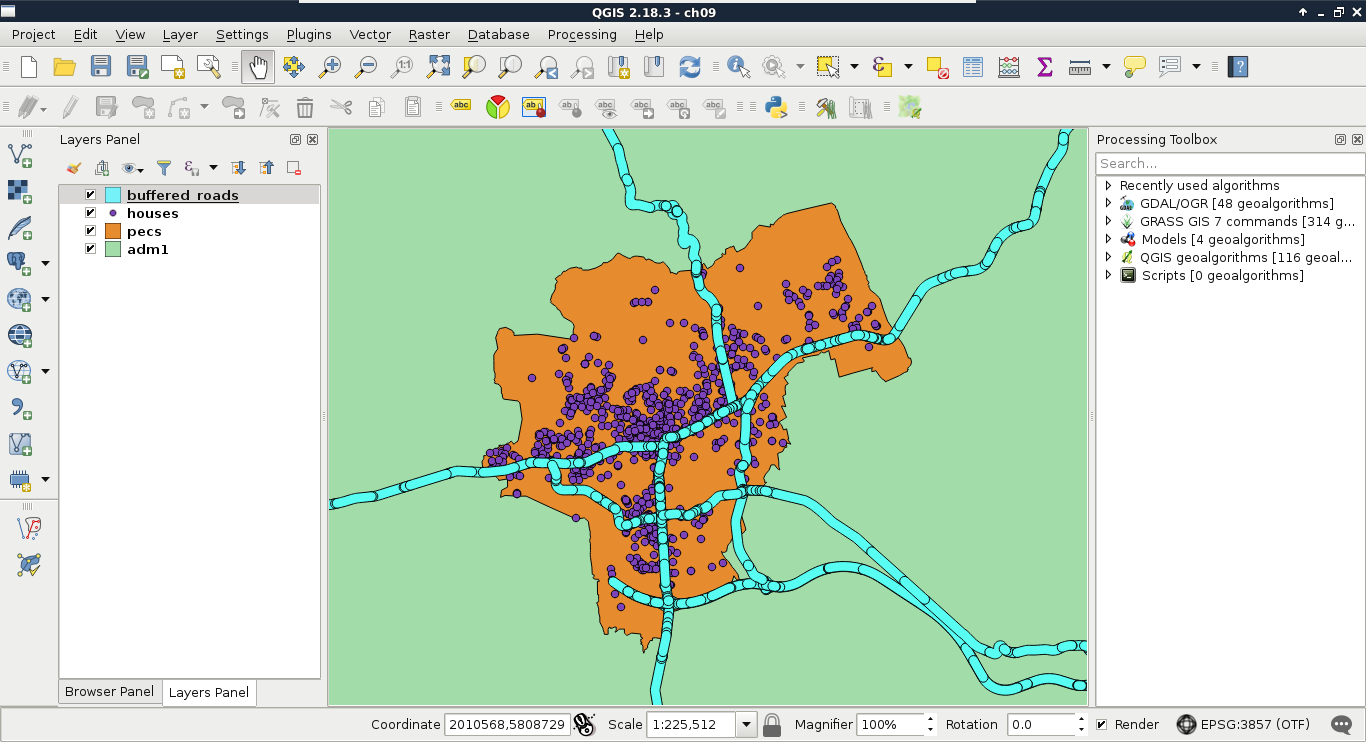

If we execute the expression with the Execute button, we can see the resulting geometries, while, if we load the result as a layer by checking the Load as a new layer box, filling out the required fields, and selecting Load now!, we can see the buffered roads in QGIS:

It is as easy as that. PostGIS iterates through the filtered roads, and buffers them on a row-by-row basis. It does not dissolve the results, or do anything else, but just returns the raw buffered geometries, and additionally, the attributes if we ask for them. As we will only use the geometries of the roads, we do not need any other attributes.

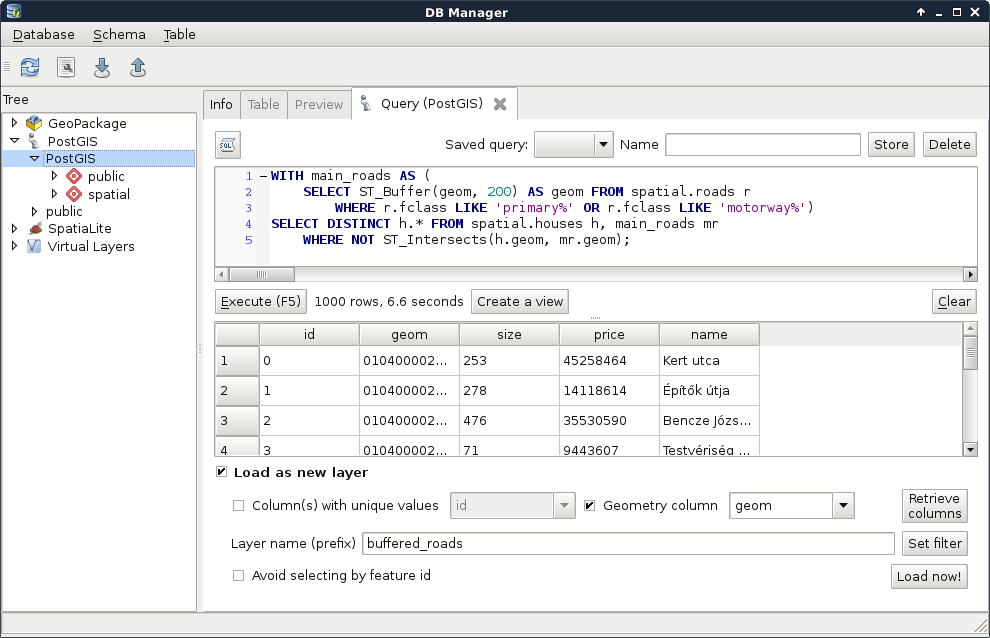

The only thing left to do is to check if our houses intersect with the buffer zones. As we only need a subset of the roads, which is effectively a subquery, we should precalculate the buffer zones in a CTE (Common Table Expression) table by using the WITH keyword as follows:

WITH main_roads AS (

SELECT ST_Buffer(geom, 200) AS geom

FROM spatial.roads r

WHERE r.fclass LIKE 'primary%' OR r.fclass LIKE 'motorway%')

SELECT h.* FROM spatial.houses h, main_roads mr

WHERE NOT ST_Intersects(h.geom, mr.geom);

Make sure to only execute the query; do not load as a layer. What did you get as a result? For me, this query returned more than 1 million rows. That's definitely a cross join between the individual buffer zones and the houses. Let's see if the results are correct, though. We can select only unique rows by using the DISTINCT operator after the SELECT keyword:

WITH main_roads AS (

SELECT ST_Buffer(geom, 200) AS geom FROM spatial.roads r

WHERE r.fclass LIKE 'primary%' OR r.fclass LIKE 'motorway%')

SELECT DISTINCT h.* FROM spatial.houses h, main_roads mr

WHERE NOT ST_Intersects(h.geom, mr.geom);

The preceding query returns 1000 rows. That's the number of features we have in our houses layer.

By creating a cross join, PostgreSQL returned every occurrence, where a house is disjoint with a buffer zone. That is, it returned every house multiple times. The magic we can use to solve this problem is to calculate the union of the buffer zones with ST_Union:

WITH main_roads AS (

SELECT ST_Union(ST_Buffer(geom, 200)) AS geom

FROM spatial.roads r

WHERE r.fclass LIKE 'primary%' OR r.fclass LIKE 'motorway%')

SELECT h.* FROM spatial.houses h, main_roads mr

WHERE NOT ST_Intersects(h.geom, mr.geom);

You must be wondering if this even makes any sense. If PostGIS goes row by row, why would it matter if we use union on every individual buffered geometry? The answer is that ST_Union is an aggregate function. Aggregate functions in PostGIS behave differently when they are called with one argument in a SELECT clause. They act on every returned row, and return a single geometry if there are no additional groupings defined. Now that the main_roads table has a single row, PostgreSQL behaves nicely, and returns only the disjoint features in less than a second.

The only thing left to do is to query houses which do not reside in the 500 meters buffer zone of industrial areas. For this, we need an additional CTE table with the union of the buffered industrial areas. In PostgreSQL, we can create multiple virtual tables in a single WITH clause by separating them with commas as follows:

WITH main_roads AS (

SELECT ST_Union(ST_Buffer(geom, 200)) AS geom

FROM spatial.roads r

WHERE r.fclass LIKE 'primary%' OR r.fclass LIKE 'motorway%'),

industrial_areas AS (

SELECT ST_Union(ST_Buffer(geom, 500)) AS geom

FROM spatial.landuse l

WHERE l.fclass = 'industrial' OR l.fclass = 'quarry')

SELECT h.* FROM spatial.houses h, main_roads mr,

industrial_areas ia

WHERE NOT ST_Intersects(h.geom, mr.geom) AND NOT

ST_Intersects(h.geom, ia.geom);

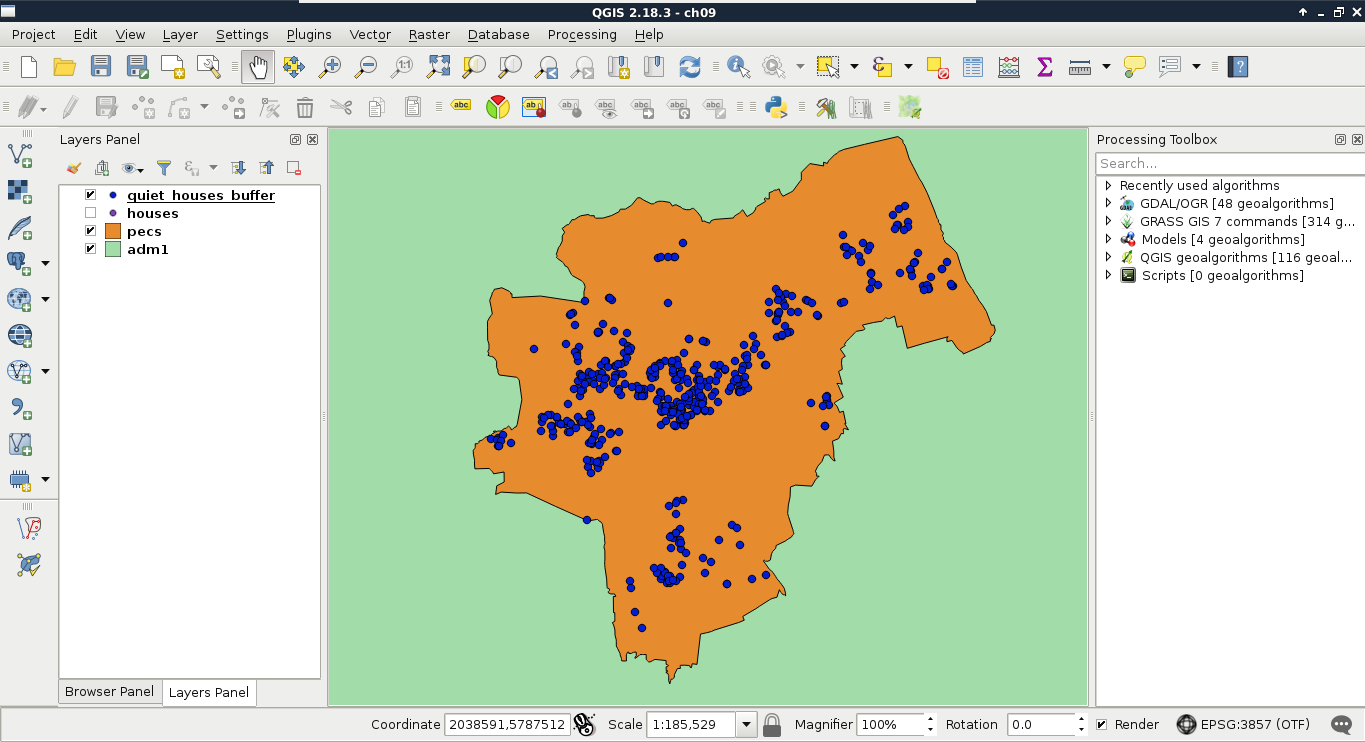

Quite a complex query, isn't it? On the other hand, it still returns the correct houses in less than a second, which is a serious performance boost. Let's load the results as a layer in QGIS, named something like quiet_houses_buffer:

What is really great about PostGIS is that we do not have to rely on traditional ways of analysis. We can cook up new methods if they can be done on a row-by-row basis, and return correct results. For example, we do not have to buffer the constraint features, just measure their distances to the houses with ST_Distance. This way, we can use a more lightweight aggregate function--ST_Collect. It does not calculate the union of the input geometries, but just merges them into a single one. If we supply polygons, the resulting geometry will be a multipart polygon containing the input polygons as members.

Let's create a query using ST_Distance and ST_Collect:

WITH main_roads AS (

SELECT ST_Collect(geom) AS geom

FROM spatial.roads r

WHERE r.fclass LIKE 'primary%' OR r.fclass LIKE 'motorway%'),

industrial_areas AS (

SELECT ST_Collect(geom) AS geom FROM spatial.landuse l

WHERE l.fclass = 'industrial' OR l.fclass = 'quarry')

SELECT h.* FROM spatial.houses h, main_roads mr,

industrial_areas ia

WHERE ST_Distance(h.geom, mr.geom) > 200 AND ST_Distance(

h.geom, ia.geom) > 500;

This method has a similar performance to the last one; however, it returned fewer features for me. If you experienced the same, load the results of this query in QGIS, and examine the difference.