In the composer window, we can access the layout properties of our map instantly. In the right panel, we can choose the paper size, and its orientation. On the left toolbar, we have access to the most important cartographic elements, which are added on demand as separate, configurable items. The first four tools are for item management. We can use the Select/Move item tool to move and resize items, and the Move item content tool to pan the map inside the data frame item. Under those tools, we can access the items which can be added.

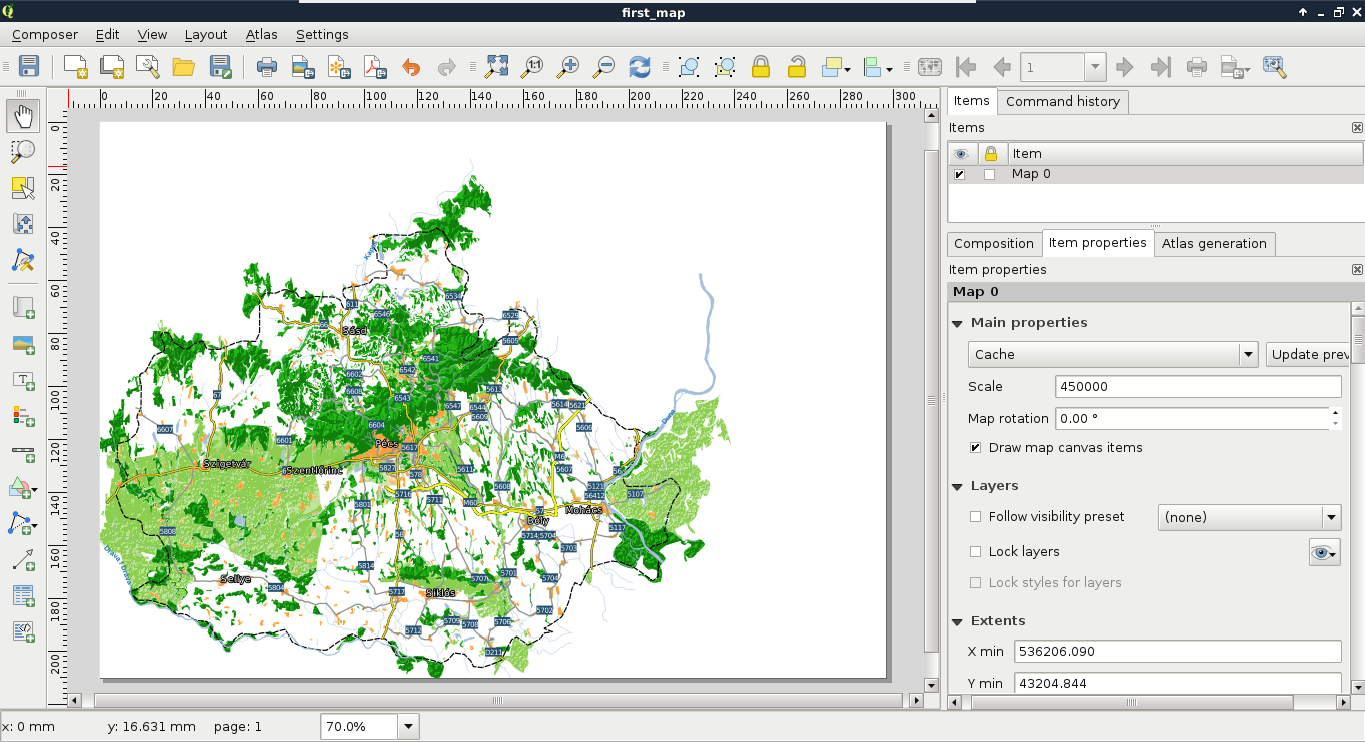

First, let's add the dataframe to the map. To do this, click on the Add new map tool, and draw a rectangle on the canvas. Let's resize the map to match the paper's dimensions. Once an item is added, we can snap its borders to the borders of our canvas. Now we have access to the item's properties in the right panel. Under Item properties, we can see the parameters of our map content. The first thing to change is its scale. It has a different scale from the browser's canvas, as it is now calculated to match our paper's size. Let's modify it to a nice, round number. When we change the scale, QGIS automatically updates the map on our canvas. However, it does not render the map at panning or zooming unless we change the Cache property to Render. Changing it degrades performance, but updates the map at every change. When you've found the right scale to use, align the map on the canvas with the Move item content tool:

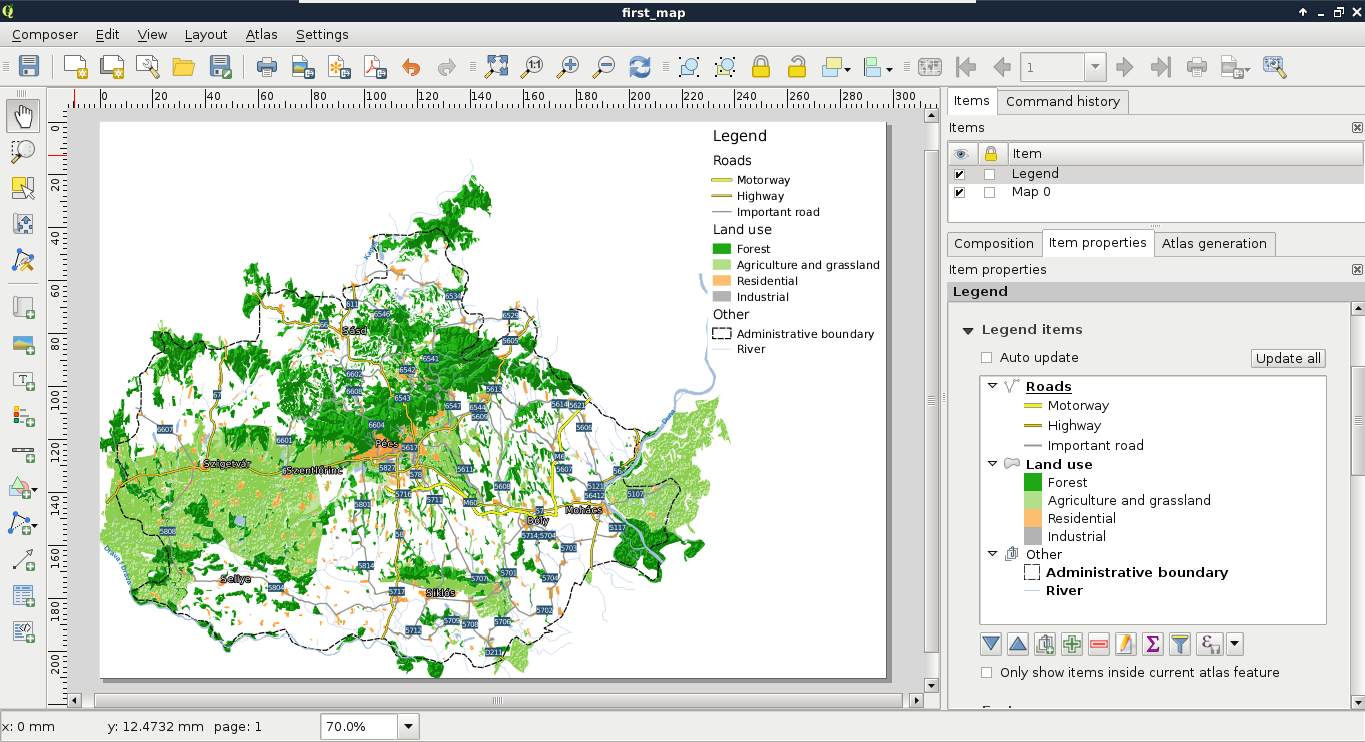

The next thing we add to the composition is a legend. We can create a legend by selecting the Add new legend tool, and drawing a rectangle on the canvas. As we can see, the legend is automatically created from the Layers Panel by default. As we have some layers which do not fit into the legend (for example, the srtm layer or the GeoNames layer), we can choose to manually customize the legend item. For this, we need to uncheck the Auto update box in the legend item's properties. Now we can delete superfluous entries by selecting them and clicking on the minus button. We can also rename the existing labels and groups, and change their order.

Let's get rid of the extra layers, and rename the rest of them to have more descriptive names. Also, there are two thematics (roads and land use) grouped, and two layers (waterways, administrative boundaries) ungrouped. To make the legend more consistent, let's create a custom group with the Add group button, name it as Other, and drag those entries into it. Finally, we should make the group fonts more consistent. The Other group has a different font, as it is a group, while the others are considered subgroups by QGIS.

To change this, you can right-click on the subgroups, and change their categorizations to group:

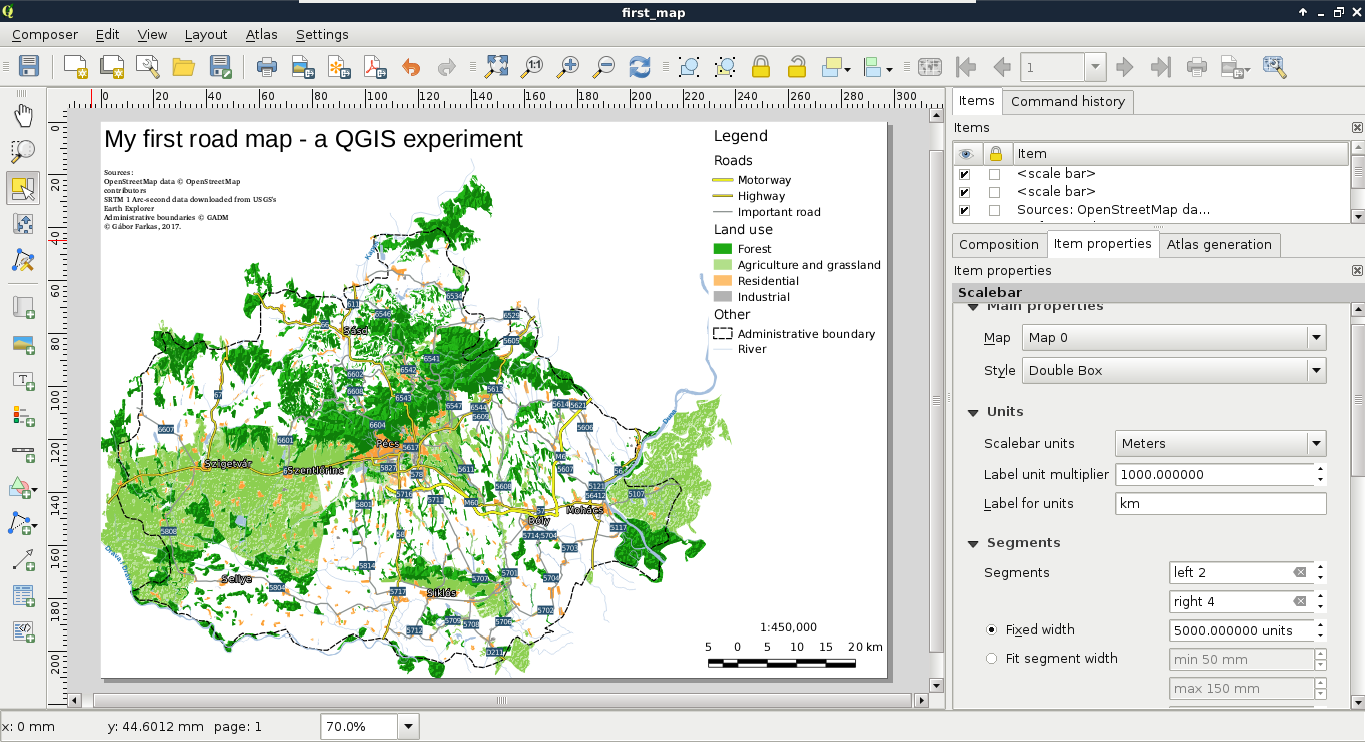

Next, we add some text content. Specifically, we add a title and proper attributions to the map. We can add custom text boxes with the Add new label button. Editing the label is not as interactive as in a vector editing software, but we can customize the label in its properties window in the right panel. The name of the layer should be concise, but descriptive. I used the name My first road map - a QGIS experiment. The attributions should go in a separate text box with a smaller font size. We should add the following four statements to the attributions:

- OpenStreetMap data © OpenStreetMap contributors.

- SRTM 1 Arc-second data downloaded from USGS's Earth Explorer.

- Administrative boundaries © GADM (or Natural Earth if you used their data instead).

- © Your Name, year of composition.

Now let's add the final piece to our map--the scale and the scale bar. We can add them both with the Add new scalebar tool. It comes with a fixed size, which needs some tinkering to modify. The easiest way to reduce its size is to modify the number of units it shows under Segments | Fixed width. We can also choose between some templates in its Style menu.

The second scale bar should only contain the scale in a numeric form. To achieve this, we can choose the Numeric style:

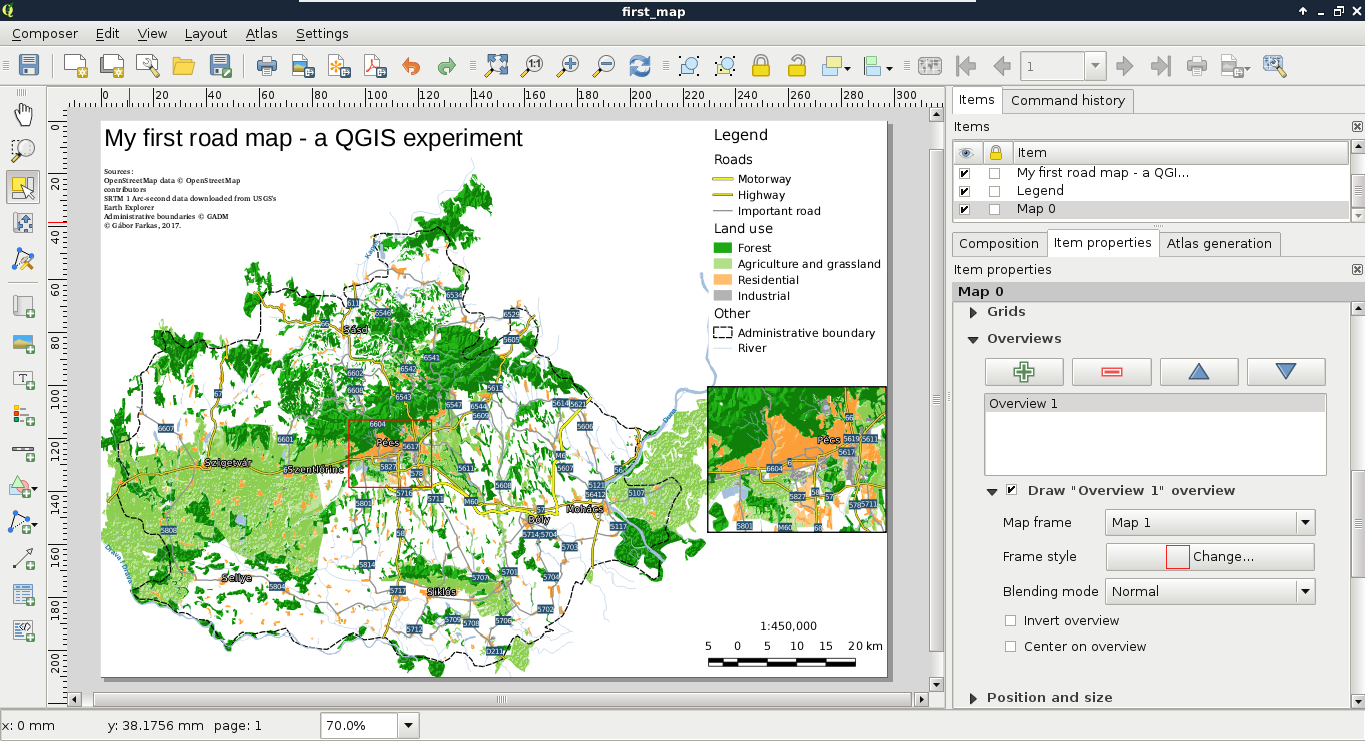

As a bonus task, let's add one final element to take up the empty space between the legend and the scale--an inset map. By adding additional data frames, we can focus on smaller areas in greater detail. Let's choose an area we would like to emphasize, and create a new data frame with the Add new map tool. If we resize it to fit the width of the legend and the scale bar, we end up with a large map and a small map showing exactly the same area. However, by using the Move item content tool, we can zoom and pan our new map to fit our needs.

QGIS offers a very handy tool for showing the extent of a data frame on another data frame. To access this property, let's select the large map's item, and navigate to Overviews. If we add an overview with the plus sign, and specify the reference to our second map in the Map frame property, we can see the extent of our inset map showing up on our main map. We can customize the look of this extent in the Frame style property:

The only thing we did not add to our map is the north arrow, as our map is oriented towards North. Unfortunately, adding a north arrow is far from trivial in QGIS 2. The first step is to add an image with the Add image tool. Under the image item's properties, we can find the Search directories menu, which contains some of the default SVG images shipped with QGIS. Among them there are some north arrows. The only problem remaining if we have to add a north arrow is that our map is rotated. An image item, on the other hand, is not. To solve this problem, we can check the Sync with map checkbox in the Image rotation menu. If our map is not rotated by hand, but by the CRS used, we can use the True north option in North alignment (Appendix 1.2).