In some setups, it is simply inconvenient to save static backups of a database on regular intervals. With continuous archiving, we can archive the changes made to our database, and roll back to a previous stable state on failure or corruption. With this archiving method, PostgreSQL automatically saves logs in a binary format to a destination location, and can restore the whole database from those logs if necessary. The main disadvantage of this method is that the whole cluster is saved, and there is no way to specify which parts we would like to archive.

First of all, what is a cluster? In PostgreSQL terms, a cluster contains every data stored in a PostgreSQL installation. A cluster can contain multiple databases containing multiple schemas with multiple tables. Using continuous archiving is crucial in production servers where corruption or data loss is a real threat, and the ability to roll back to a previous state is required.

First of all, let's find out where our PostgreSQL cluster is located on the disk. The default path is different on different operating systems, and, besides that, we can specify a custom location for our cluster. For example, as I use an SSD for the OS, and PostgreSQL would store its database on the SSD by default, I specified the postgres folder in a partition of my HDD mounted at /database for the database. We can see the path to our cluster by running the following query:

SHOW data_directory;

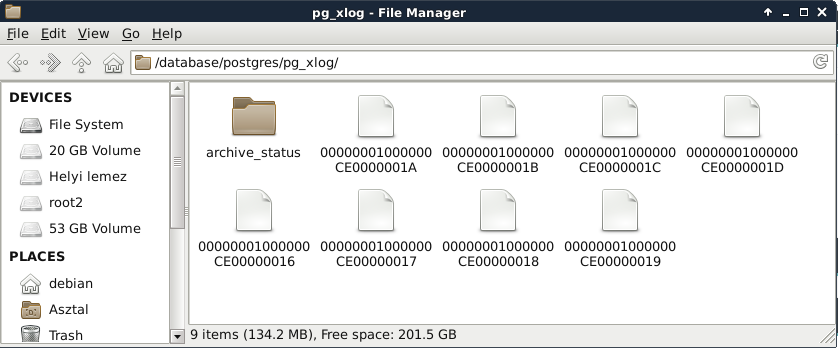

If we open the path we got from the previous query in a file manager, we will see the files and folders our PostgreSQL cluster consists of. From the folders located there, the pg_xlog contains the WALs (Write Ahead Logs) of our database transactions. WALs are part of PostgreSQL's ACID implementation, as it can restore the last stable state from these logs if something bad happens. They can be also used for continuous archiving by saving them before PostgreSQL recycles them:

To use continuous archiving, we need a base version of our cluster. This base version is the first checkpoint. From this checkpoint, logs are preserved, and we can restore previous states by restoring the first checkpoint, specifying a date, and letting PostgreSQL replay the logged transactions until the specified date. To enable WAL archiving, we have to set some system variables using a superuser role as follows:

- Set the wal_level variable to archive with the expression ALTER SYSTEM SET wal_level = 'archive';.

- Set the archive_mode variable to on with the expression ALTER SYSTEM SET archive_mode = 'on';.

- Create a place for your archives. Remember the absolute path to that place. I will use the /home/debian/postgres_archive path.

- Set the archive_command variable to the system call that PostgreSQL should archive WALs with. On Linux and macOS systems, it can be ALTER SYSTEM SET archive_command = 'test ! -f /home/debian/postgres_archive/%f && cp %p /home/debian/postgres_archive/%f';, while, on Windows, it should be something like ALTER SYSTEM SET archive_command = 'copy "%p" "C:\\postgres_archive\\%f"';. In the call, %f denotes the WAL file's name, while %p denotes its absolute path with its name.

- Restart the server.

Next, we have to set up the first checkpoint, and create a physical copy of this base version. We can put this backup wherever we like, although it should be placed somewhere along the WAL files.

- Start creating the first checkpoint with the query SELECT pg_start_backup('backup', true);. By specifying true, we ask PostgreSQL to create the checkpoint as soon as possible. Without it, creating the checkpoint takes up about 2.5 minutes with the default settings. Wait for the query to finish.

- Copy out everything from the cluster to the backup folder. You can use any tool for this, although you must make sure that file permissions remain the same. On Linux and macOS, tar is a great tool for this. With my paths, the command looks like the following:

tar -czvf /home/debian/postgres_archive/basebackup.tar.gz

/database/postgres.

- Stop the backup mode with the query SELECT pg_stop_backup();.

Let's say the worst has happened, and our database is corrupted. In that case, our first task is to find out the last time our database was stable. We can guess, but in this case, guessing is a bad practice. We should look through our logs to see when our database went off. We don’t want to have to rollback more transactions than necessary, as this can have a significant impact on a production server. When we have a date, we can start recovering with PostgreSQL's PITR (Point-in-Time Recovery) technique:

- Shut down the PostgreSQL server.

- Make a backup copy from the corrupted cluster's pg_xlog folder, as it might contain WAL files which haven't been archived yet. It is a good practice to make a copy of the corrupted cluster for later analysis if you have the required free disk space.

- Delete the cluster, and replace it with the base backup's content.

- The base backup's pg_xlog folder's content is now obsolete, as those changes were already incorporated in the backup database. Replace its content with the corrupted cluster's logs. Watch out for keeping the correct permissions!

- Create a file named recovery.conf in the cluster. The file's content must contain the inverse of the archiving command saved to the restore_command variable. It should also contain the date until the recovery should proceed to be saved to the recovery_target_time variable:

restore_command = 'cp /home/debian/postgres_archive/%f %p'

recovery_target_time = '2017-02-21 13:00:00 GMT'

- Start the server. When PostgreSQL is done with the recovery, it will rename recovery.conf to recovery.done.