BIRMINGHAM - MUMBAI

BIRMINGHAM - MUMBAI

Copyright © 2017 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

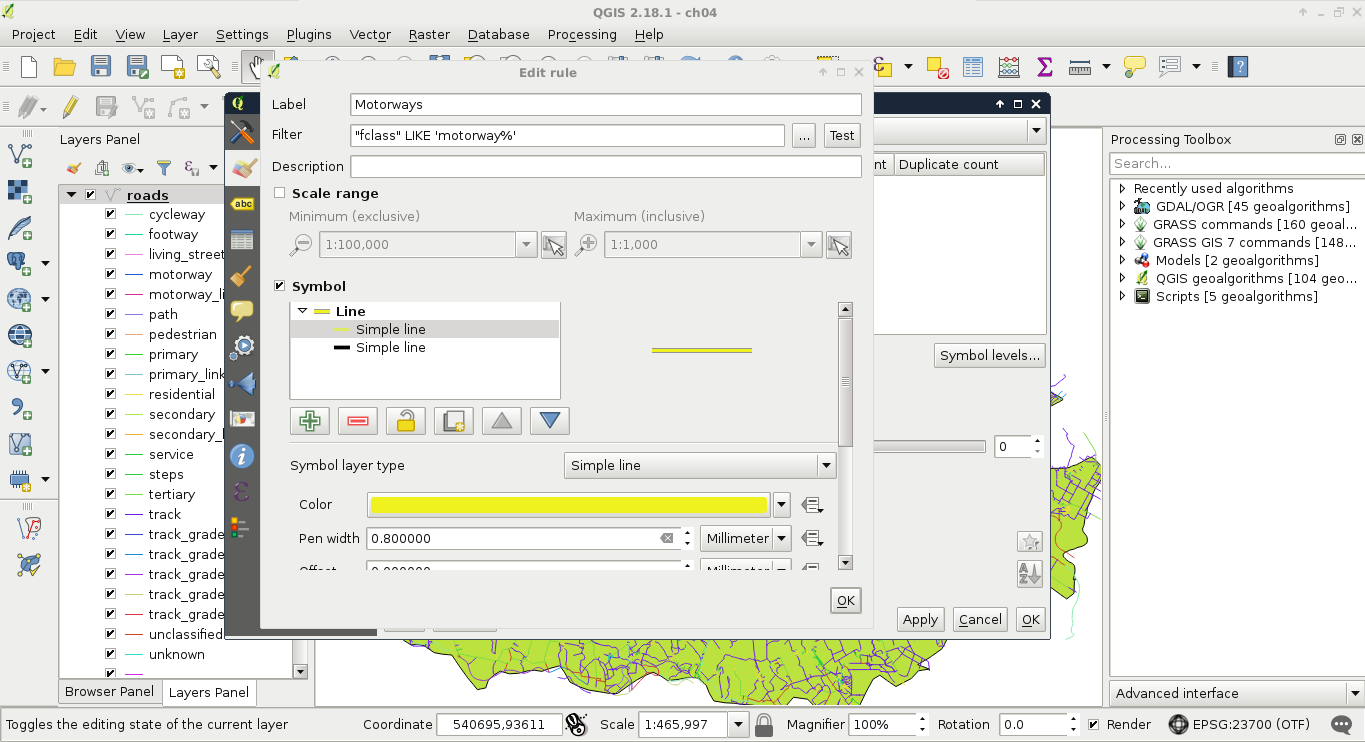

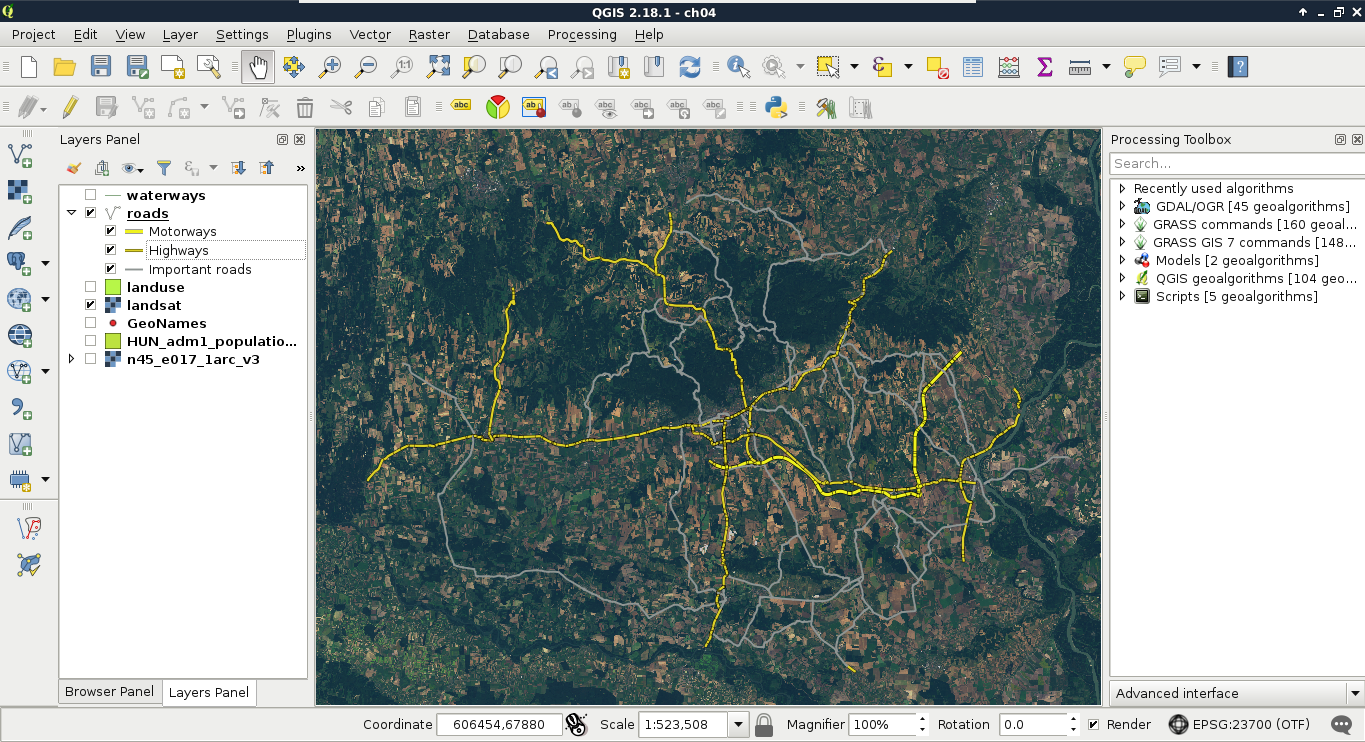

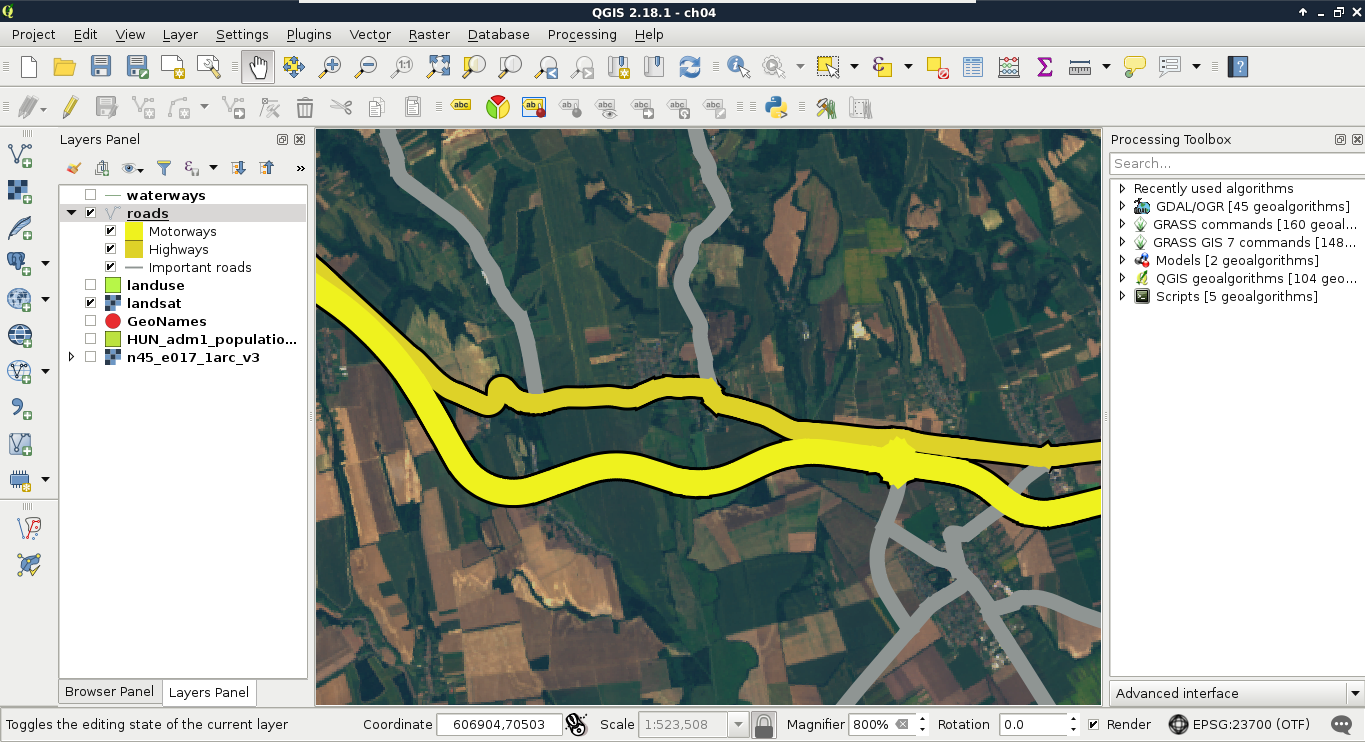

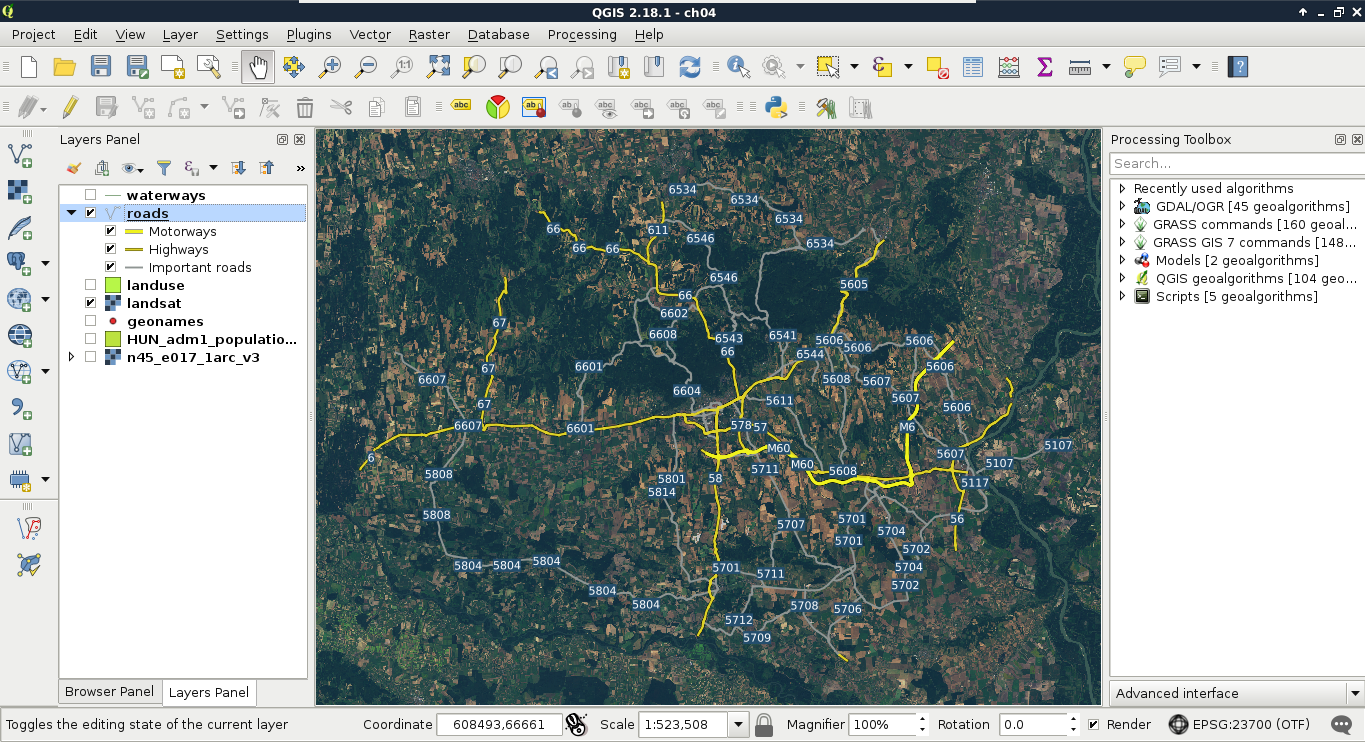

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing, and its dealers and distributors will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

First published: June 2017

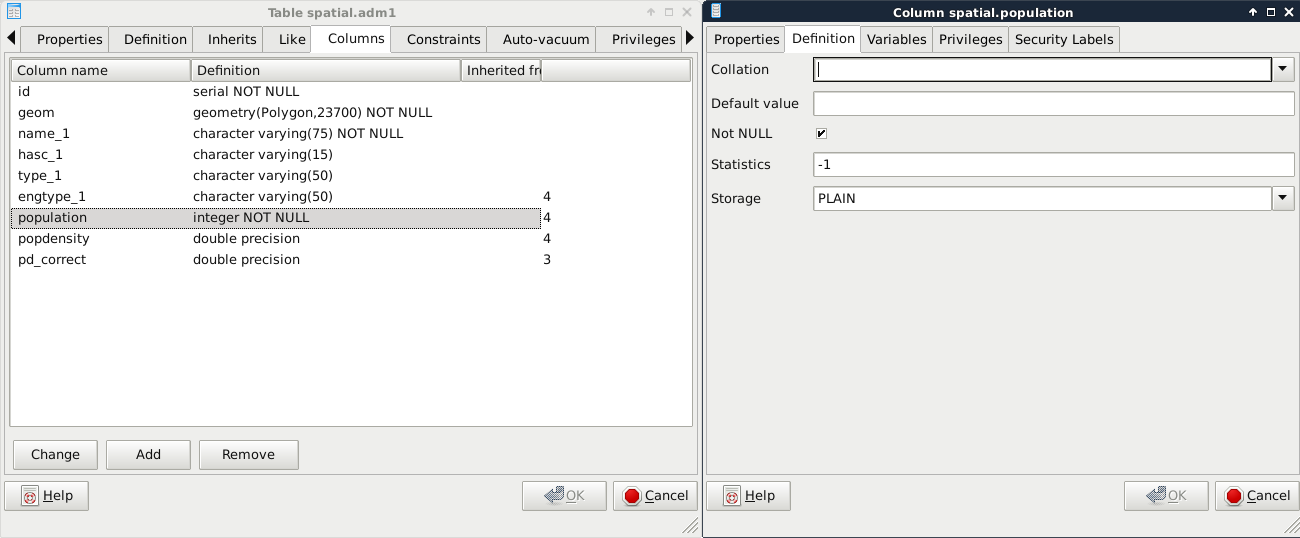

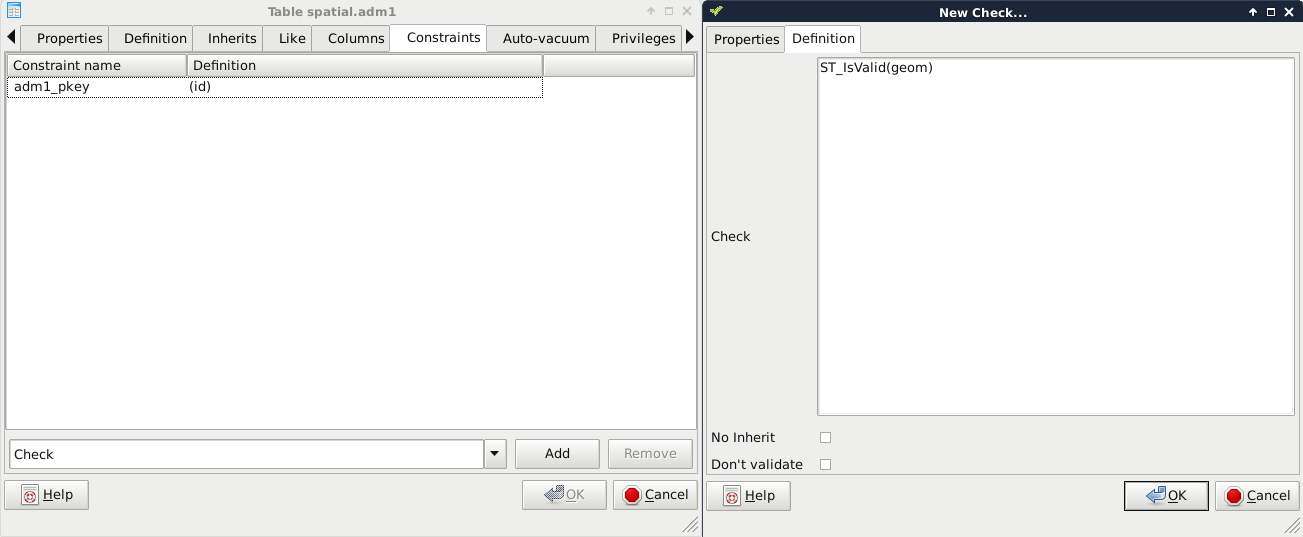

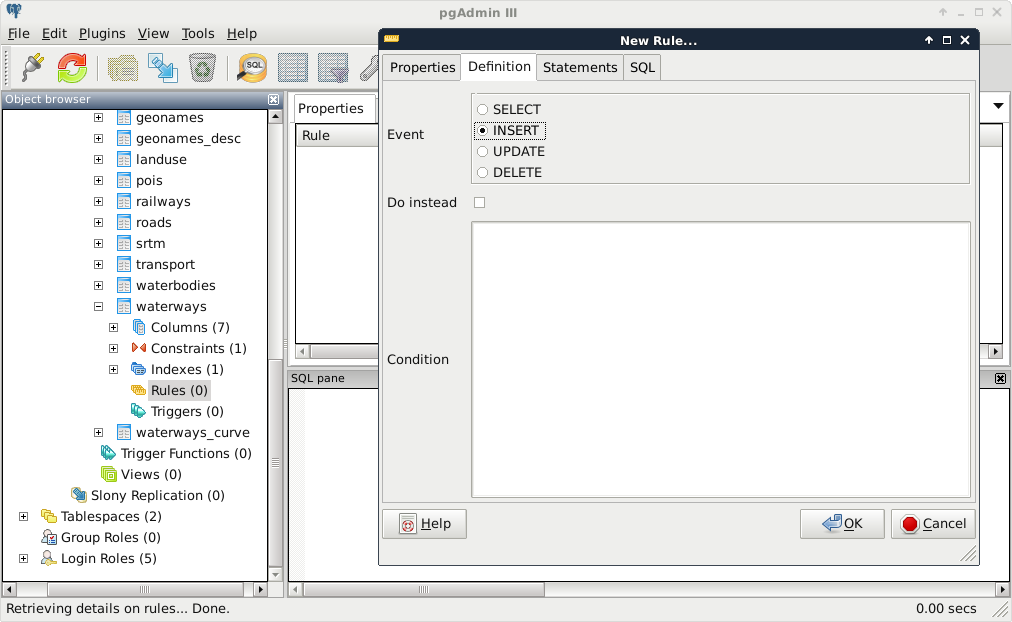

Production reference: 1080617

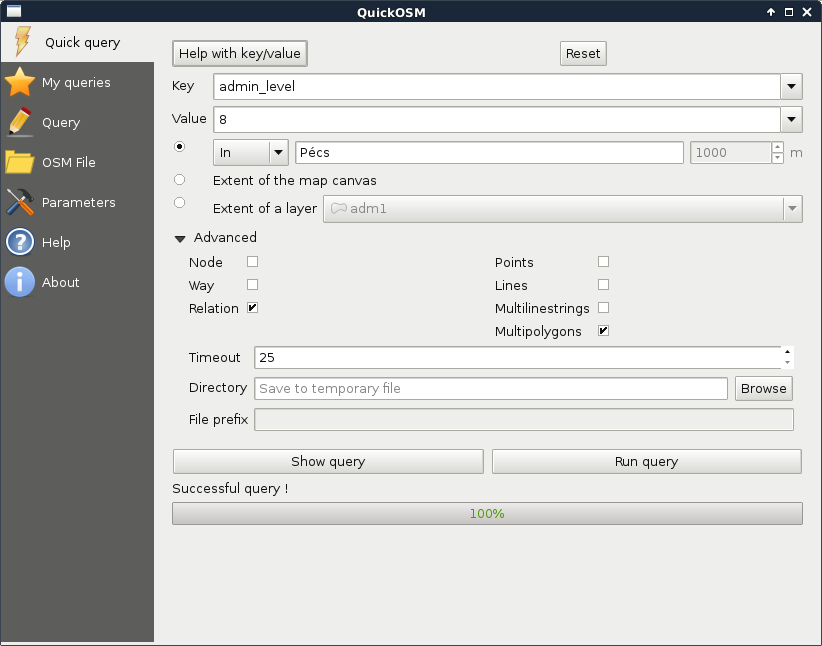

ISBN 978-1-78712-332-8

|

Author |

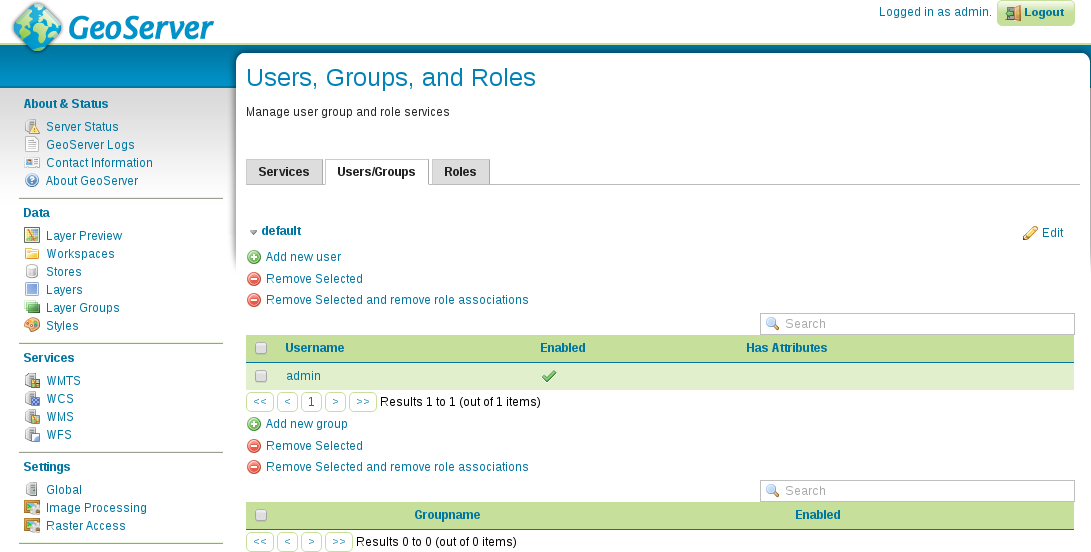

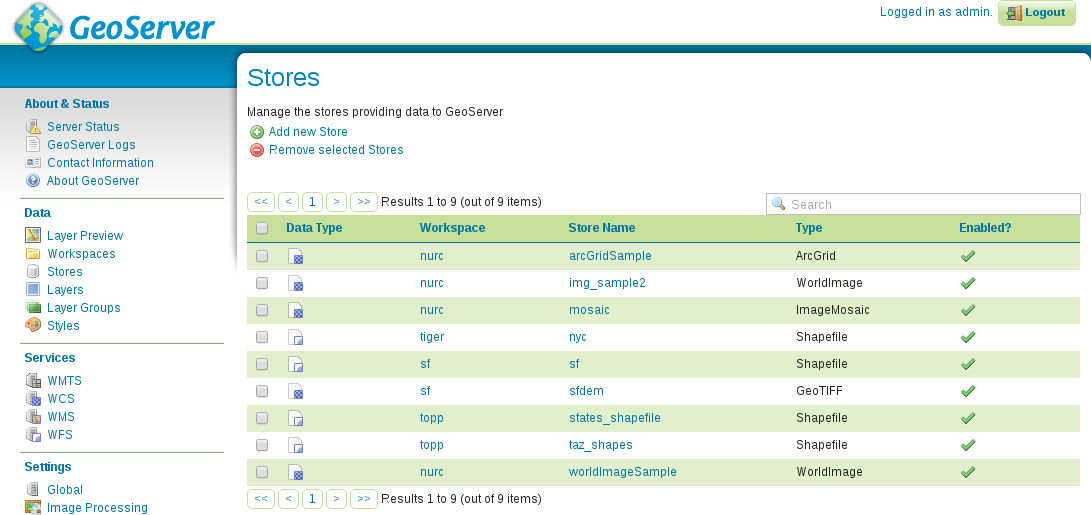

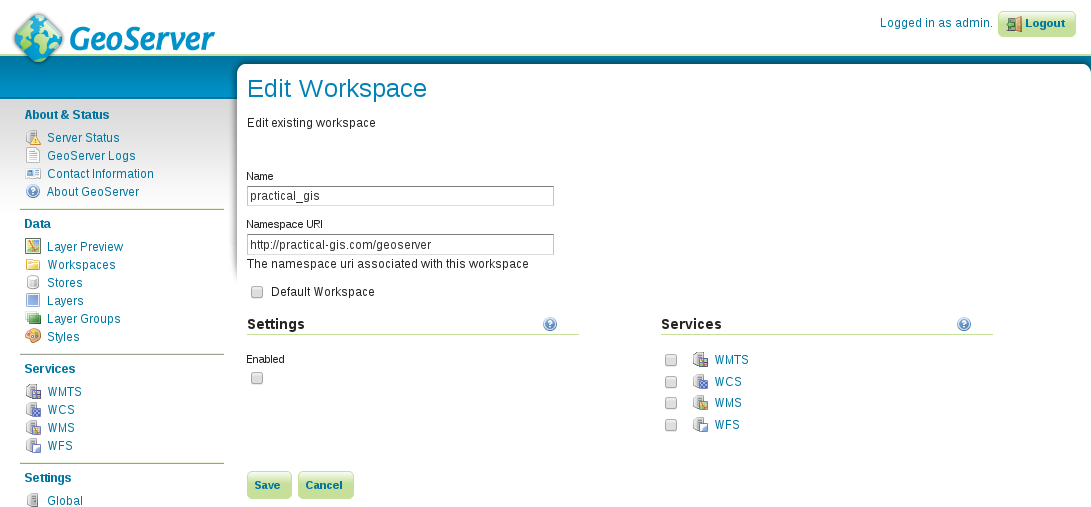

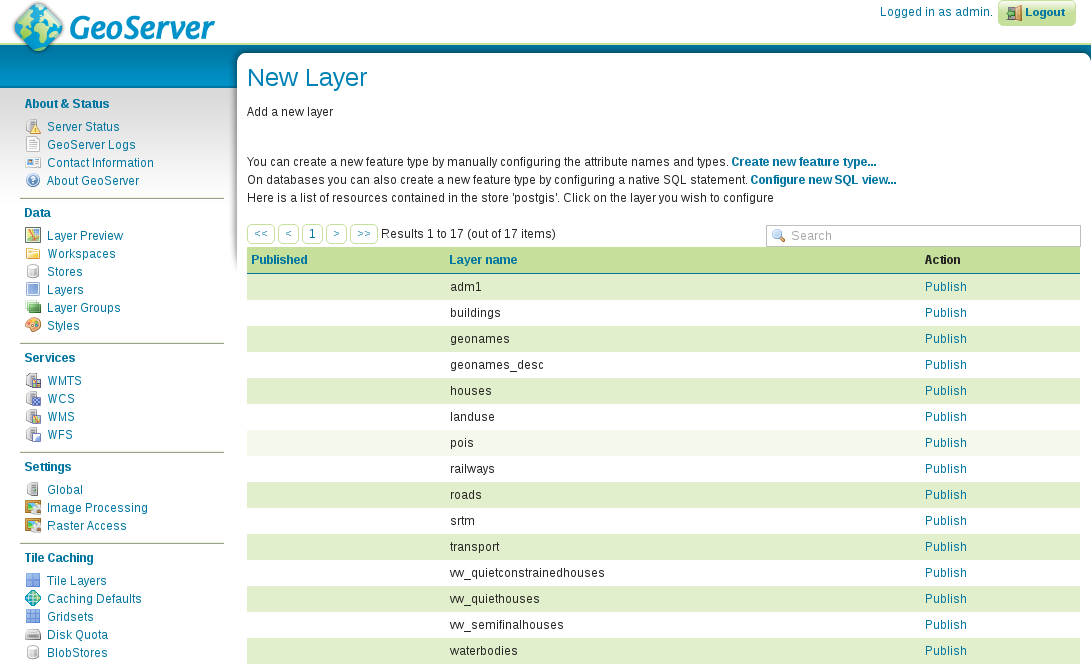

Copy Editor Sonia Mathur |

|

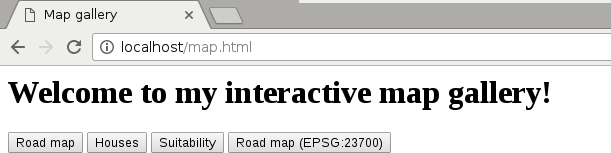

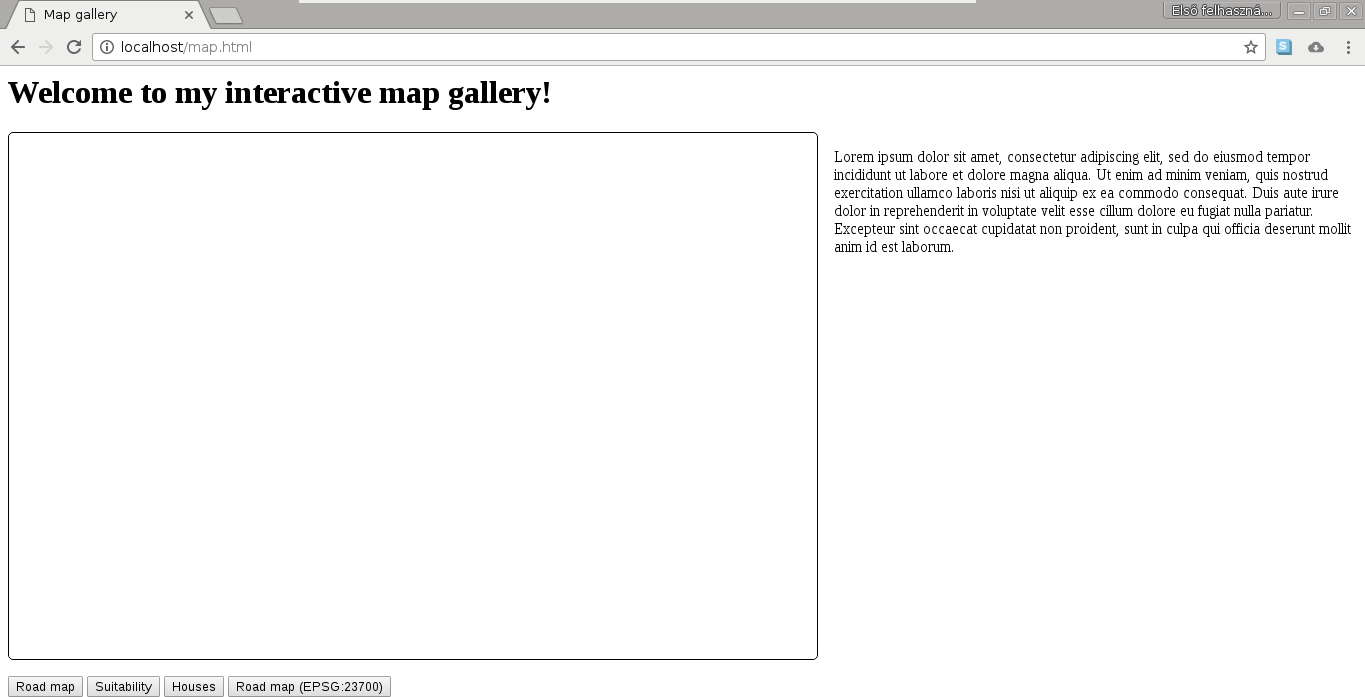

Reviewers Mark Lewin David Bianco |

Project Coordinator Prajakta Naik |

|

Commissioning Editor Aaron Lazar |

Proofreader Safis Editing |

|

Acquisition Editor Angad Singh |

Indexer Mariammal Chettiyar |

|

Content Development Editor Lawrence Veigas |

Graphics Abhinash Sahu |

|

Technical Editor Abhishek Sharma |

Production Coordinator Shantanu Zagade |

Gábor Farkas is a PhD student in the University of Pécs's Institute of Geography. He holds a master's degree in geography, although he moved from traditional geography to pure geoinformatics in his early studies. He often studies geoinformatical solutions in his free time, keeps up with the latest trends, and is an open source enthusiast. He loves to work with GRASS GIS, PostGIS, and QGIS, but his all time favorite is Web GIS, which mostly covers his main research interest.

Mark Lewin has been developing, teaching, and writing about software for over 16 years. His main interest is GIS and web mapping. Working for ESRI, the world's largest GIS company, he acted as a consultant, trainer, course author, and a frequent speaker at industry events. He has subsequently expanded his knowledge to include a wide variety of open source mapping technologies and a handful of relevant JavaScript frameworks including Node.js, Dojo, and JQuery.

Mark now works for Oracle’s MySQL curriculum team, focusing on creating great learning experiences for DBAs and developers, but remains crazy about web mapping.

He is the author of books such as Leaflet.js Succinctly, Go Succinctly, and Go Web Development Succinctly for Syncfusion. He is also the co-author of the forthcoming second edition of Building Web and Mobile ArcGIS Server Applications with JavaScript, which is to be published by Packt.

For support files and downloads related to your book, please visit www.PacktPub.com.

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at service@packtpub.com for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

![]()

Get the most in-demand software skills with Mapt. Mapt gives you full access to all Packt books and video courses, as well as industry-leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career.

Thanks for purchasing this Packt book. At Packt, quality is at the heart of our editorial process. To help us improve, please leave us an honest review on this book's Amazon page at https://www.amazon.com/dp/1787123324.

If you'd like to join our team of regular reviewers, you can e-mail us at customerreviews@packtpub.com. We award our regular reviewers with free eBooks and videos in exchange for their valuable feedback. Help us be relentless in improving our products!

In the past, professional spatial analysis in the business sector was equivalent to buying an ArcGIS license, storing the data in some kind of Esri database, and publishing results with the ArcGIS Server. These trends seem to be changing in the favor of open source software. As FOSS (free and open source software) products are gaining more and more power due to the hard work of the enthusiastic open source GIS community, they pique the curiosity of the business sector at a growing rate. With the increasing number of FOSS GIS experts and consulting companies, both training and documentation--the two determining factors that open source GIS products traditionally lacked--are becoming more available.

Chapter 1, Setting Up Your Environment, guides you through the basic steps of creating an open source software infrastructure you can carry out your analyses with. It also introduces you to popular open data sources you can freely use in your workflow.

Chapter 2, Accessing GIS Data with QGIS, teaches you about the basic data models used in GIS. It discusses the peculiarities of these data models in detail, and also makes you familiar with the GUI of QGIS by browsing through some data.

Chapter 3, Using Vector Data Effectively, shows you how you can interact with vector data in the GIS software. It discusses GUI-based queries, SQL-based queries, and basic attribute data management. You will get accommodated to the vector data model and can use the attributes associated to the vector features in various ways.

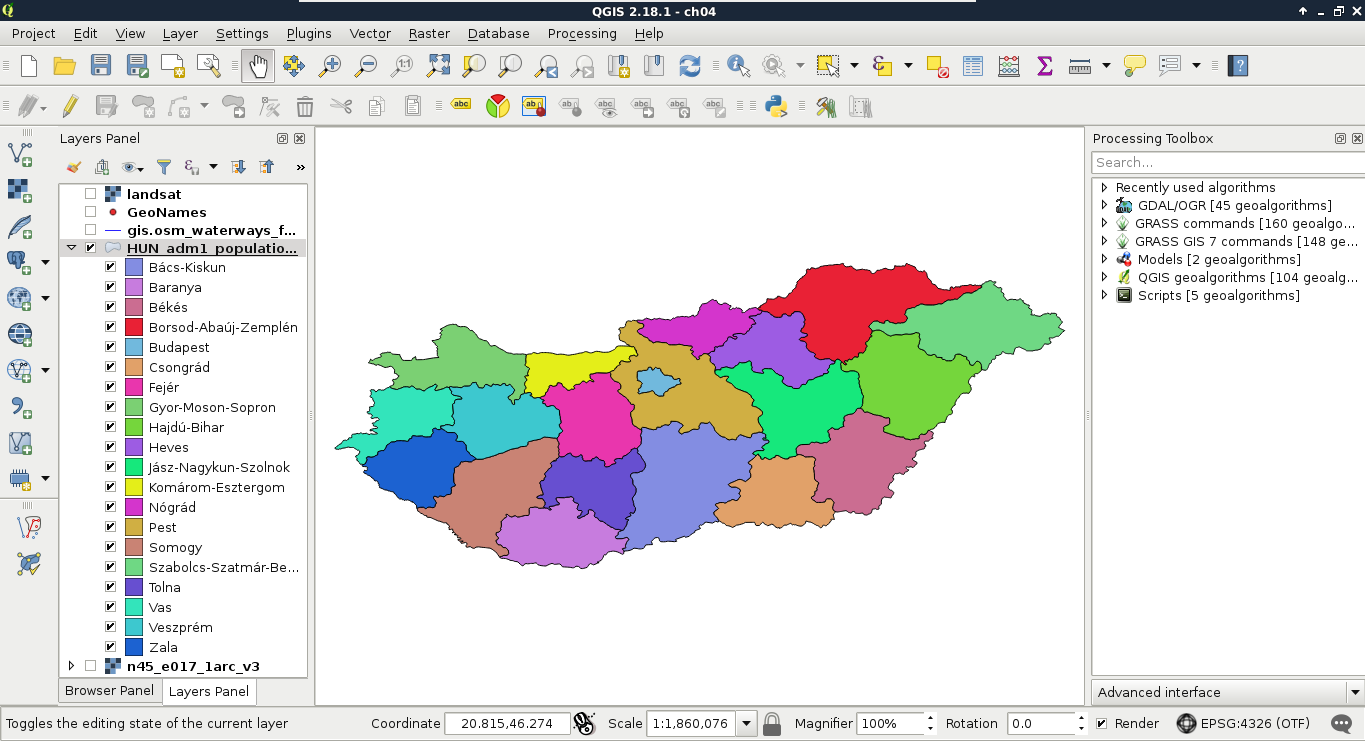

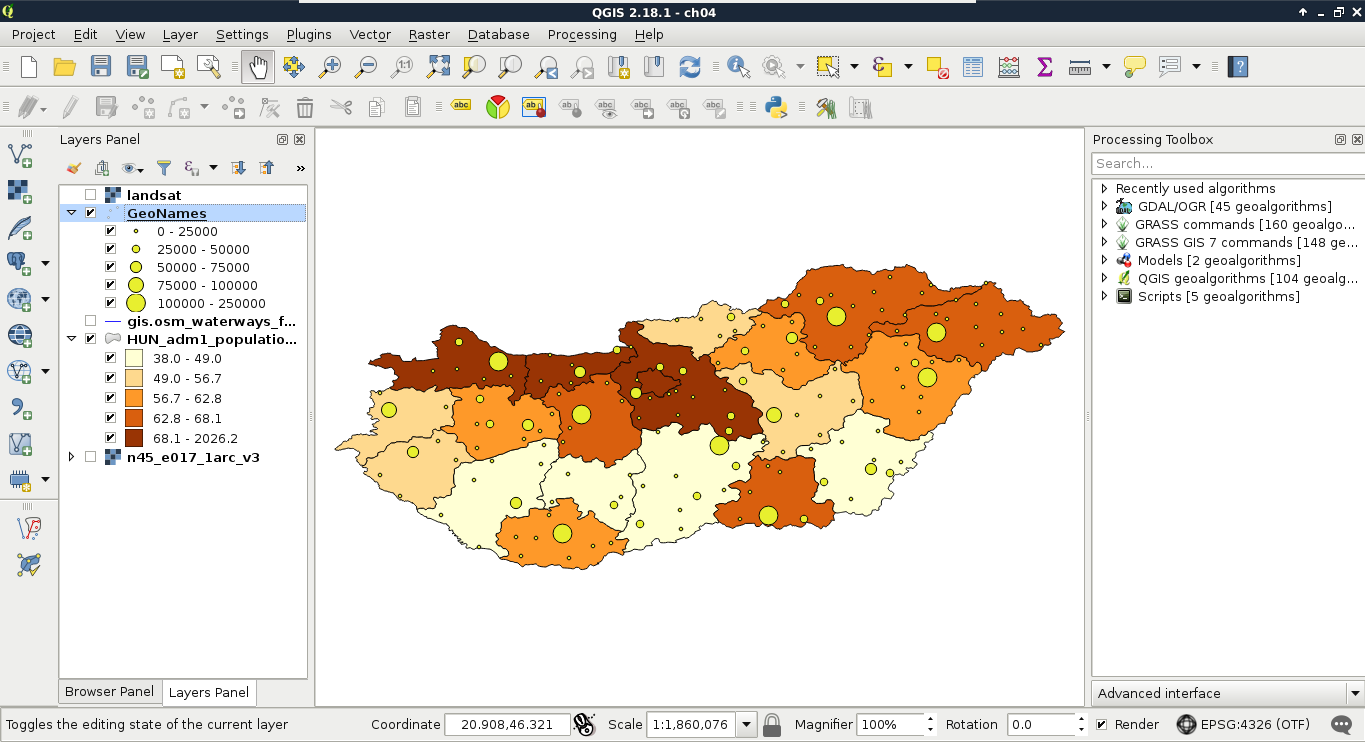

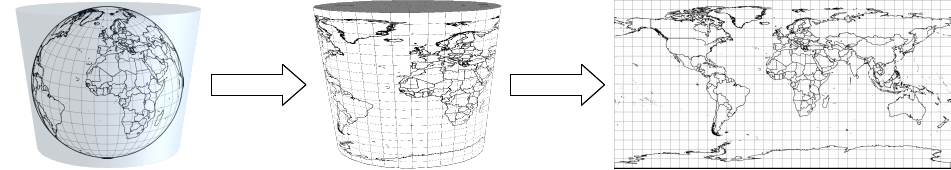

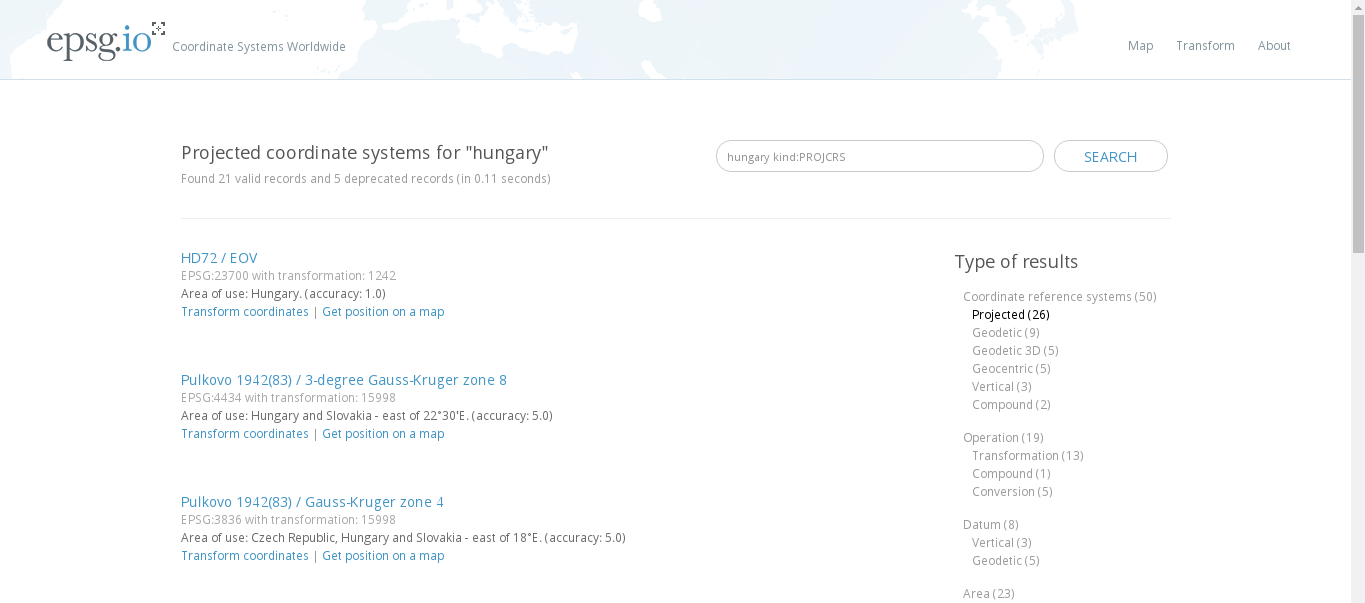

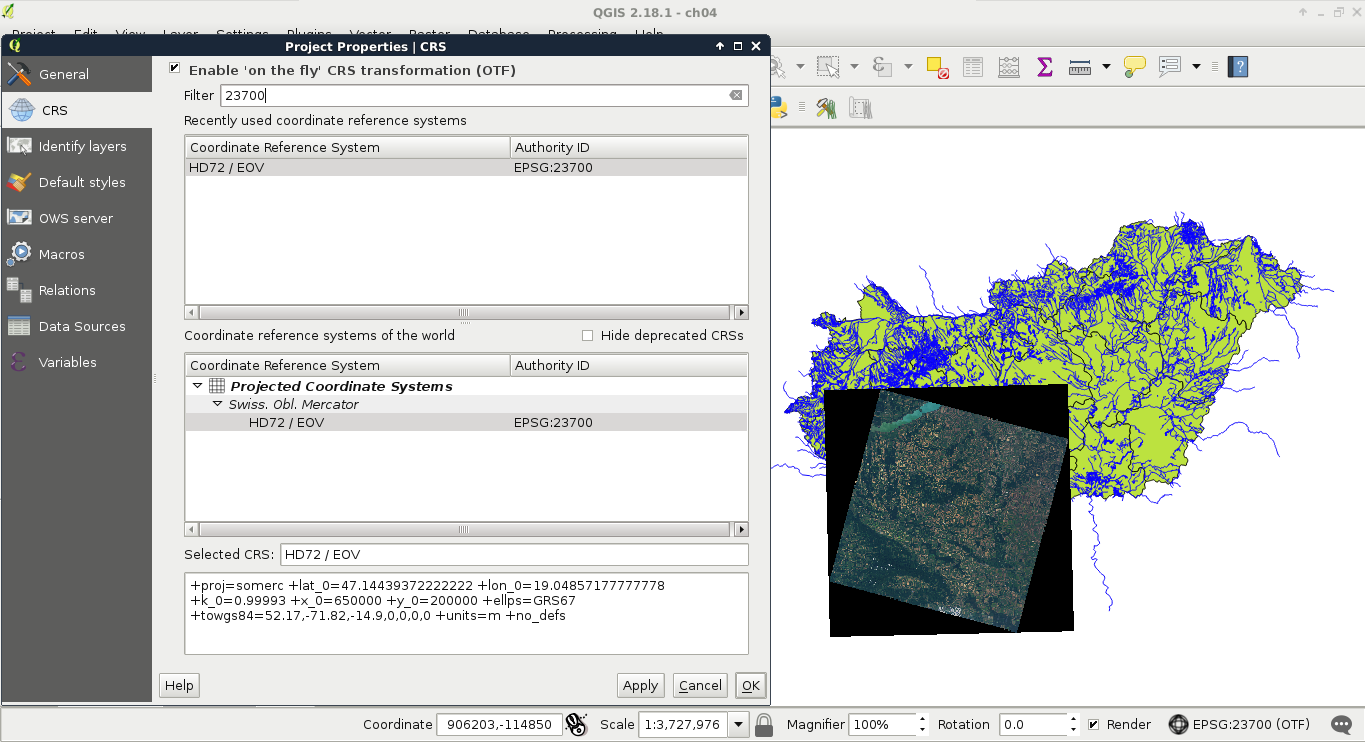

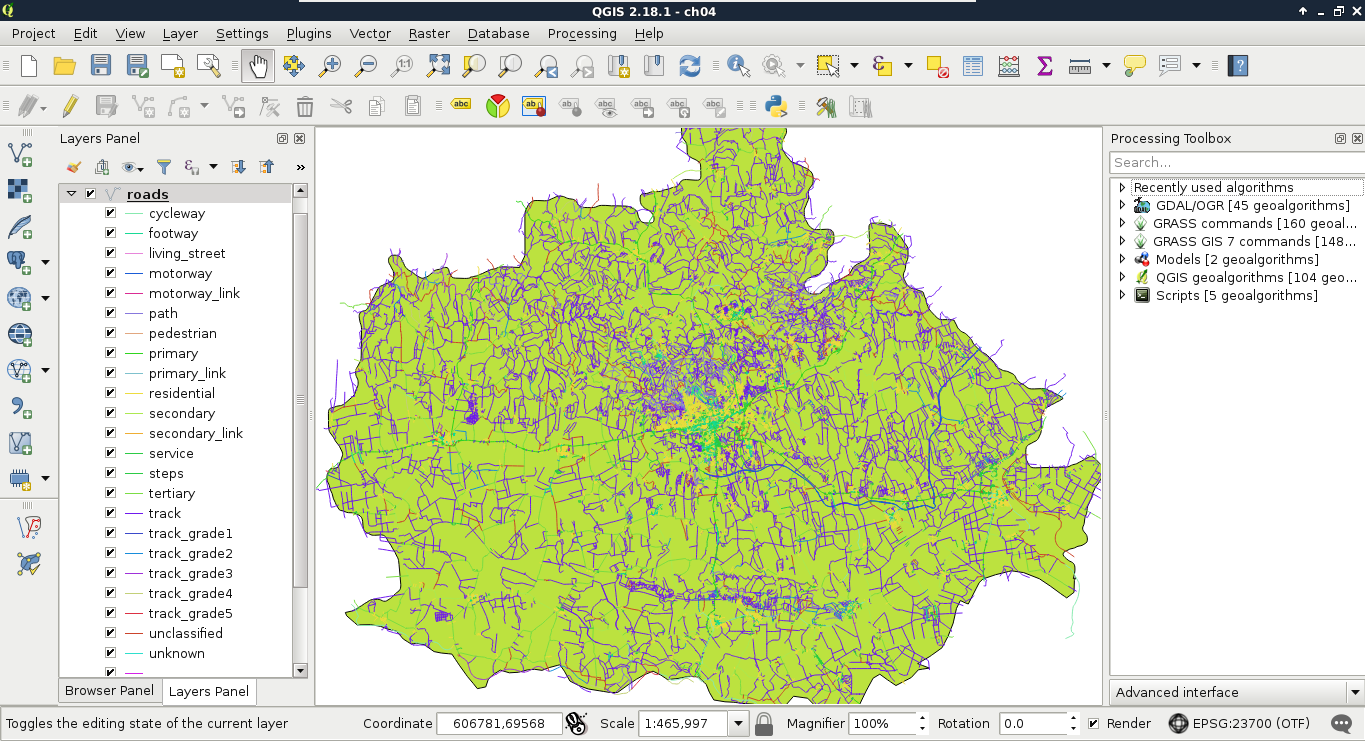

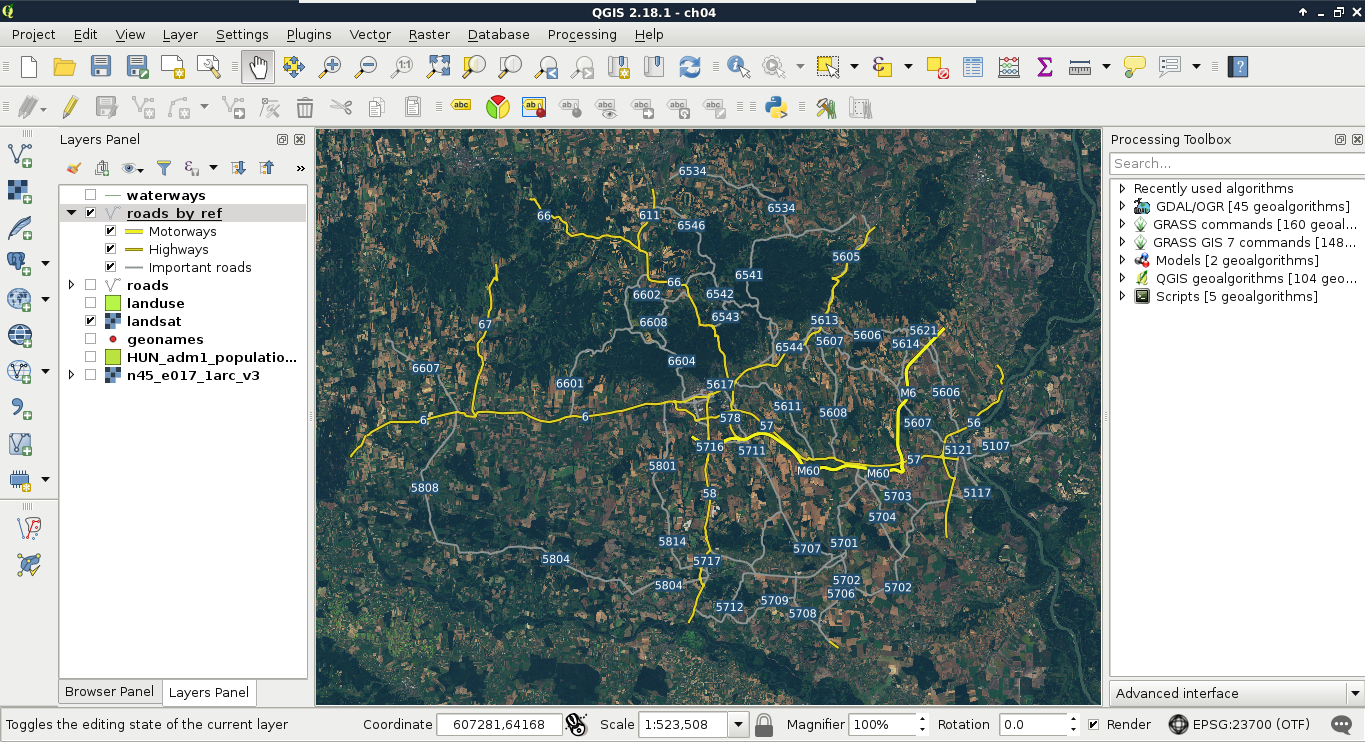

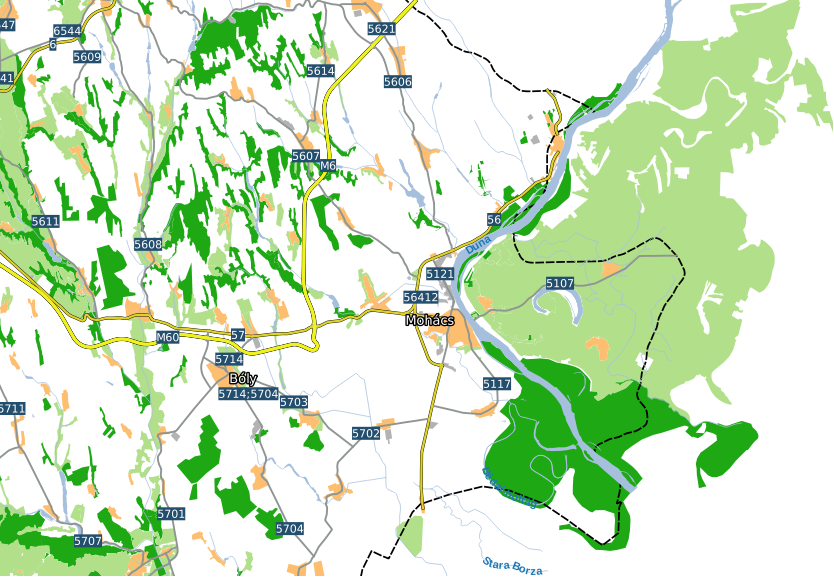

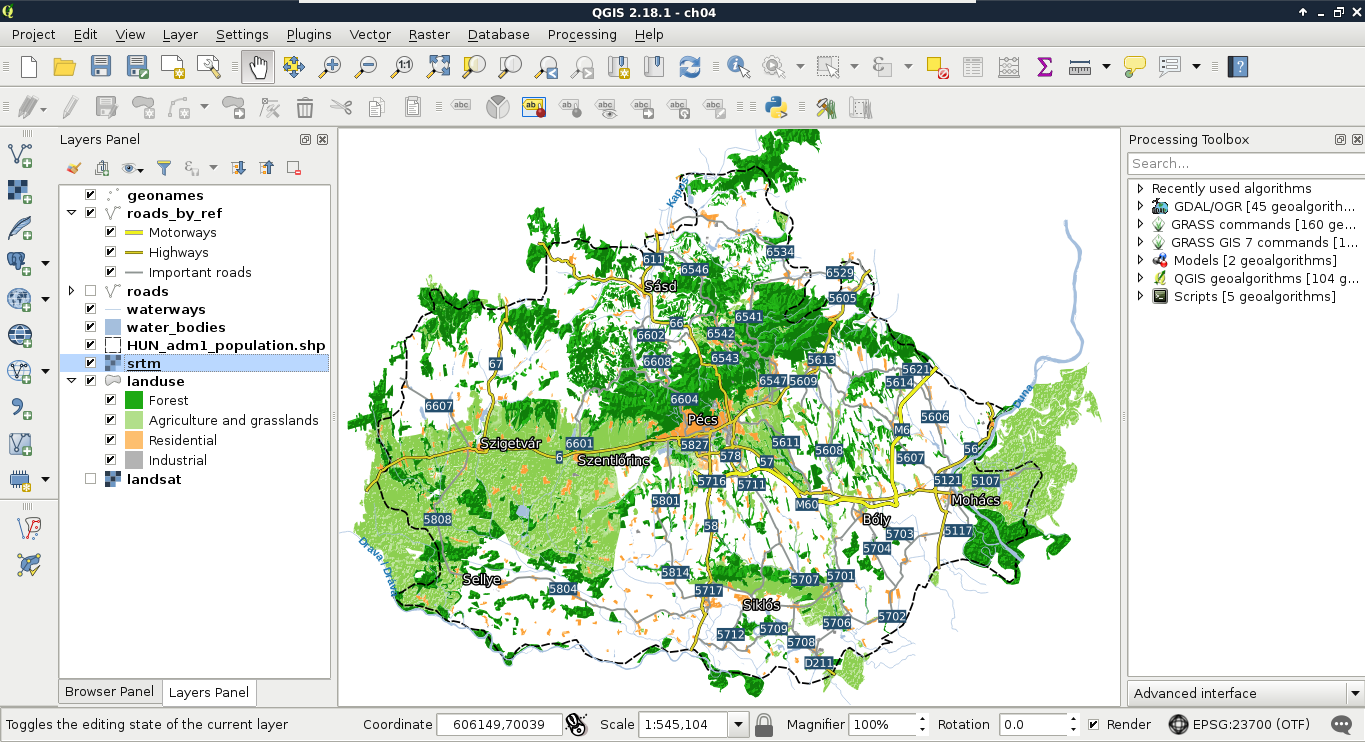

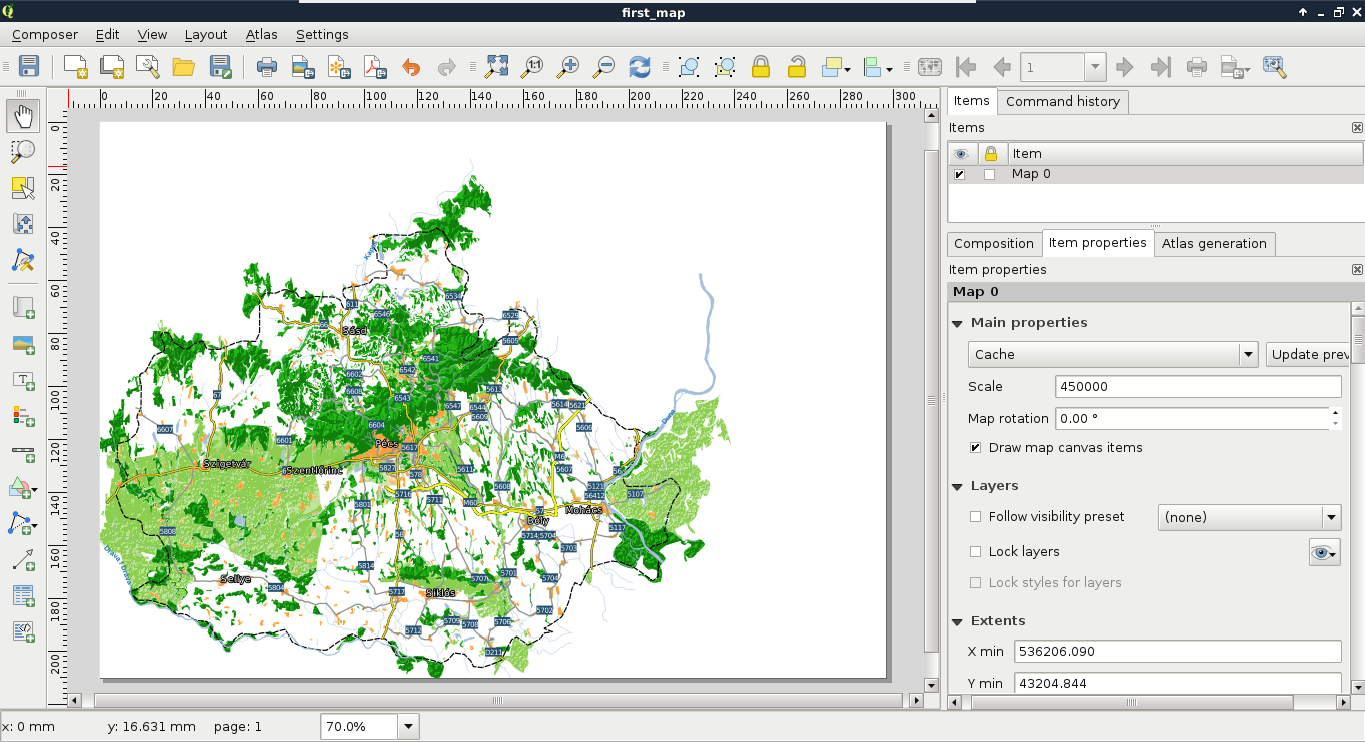

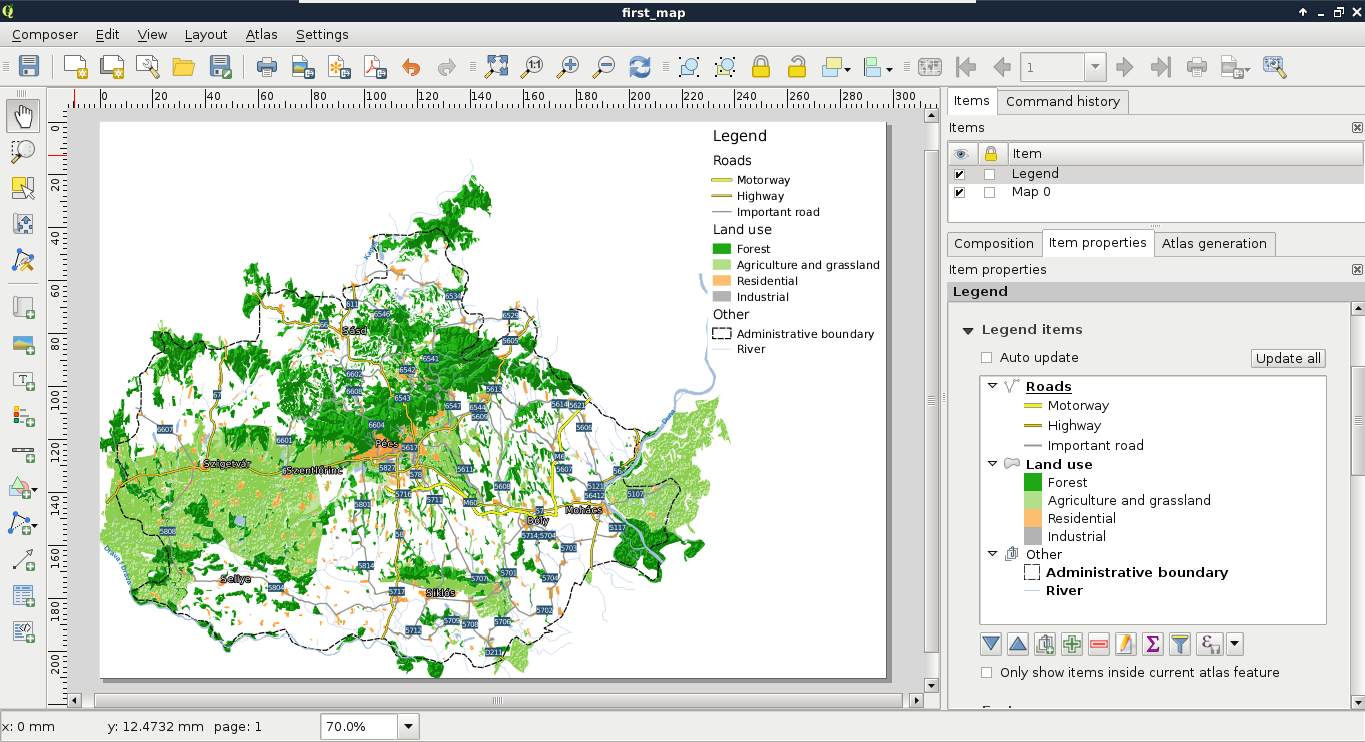

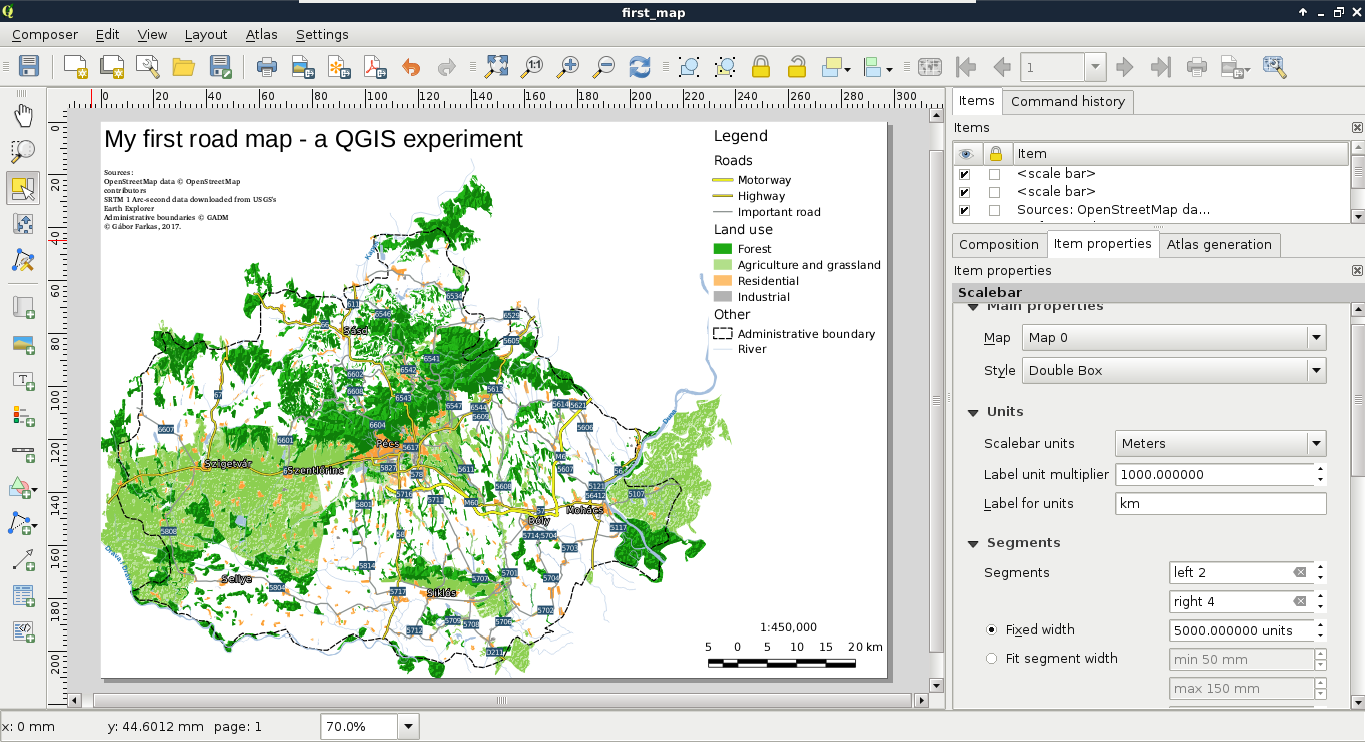

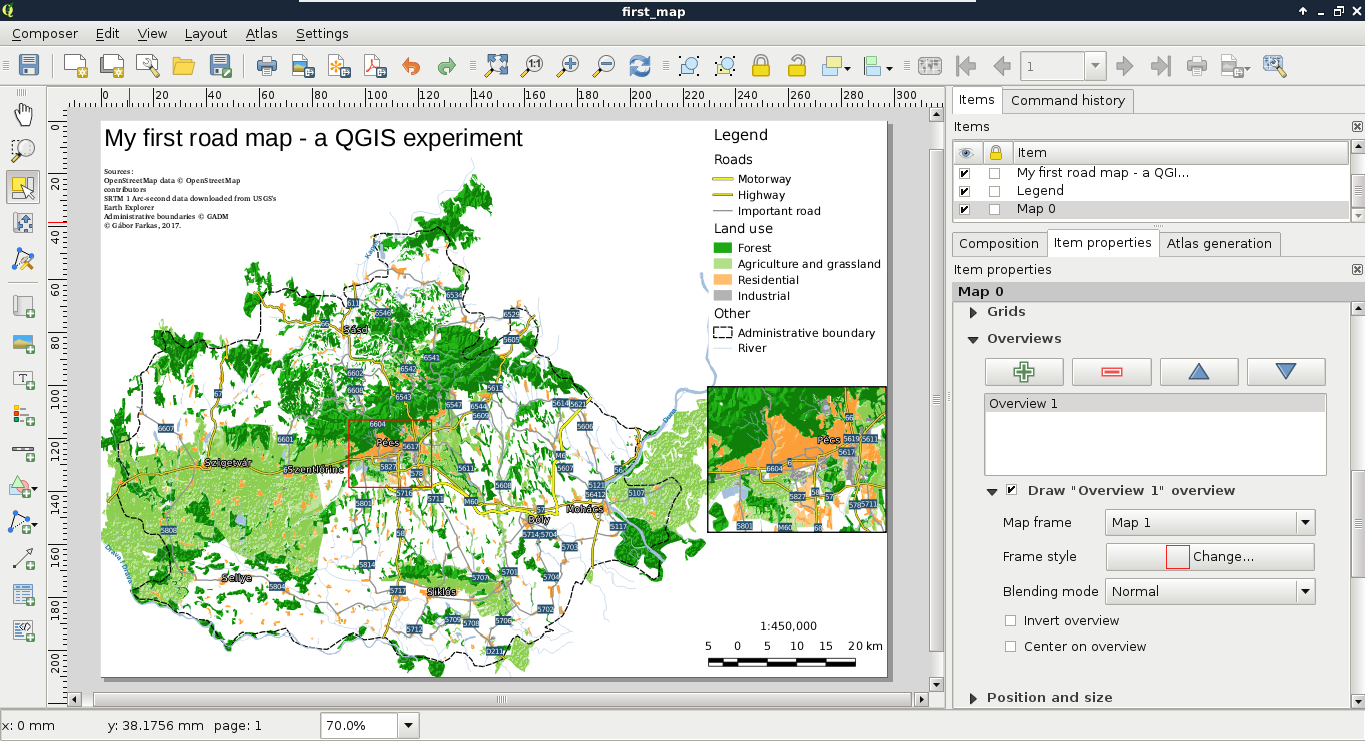

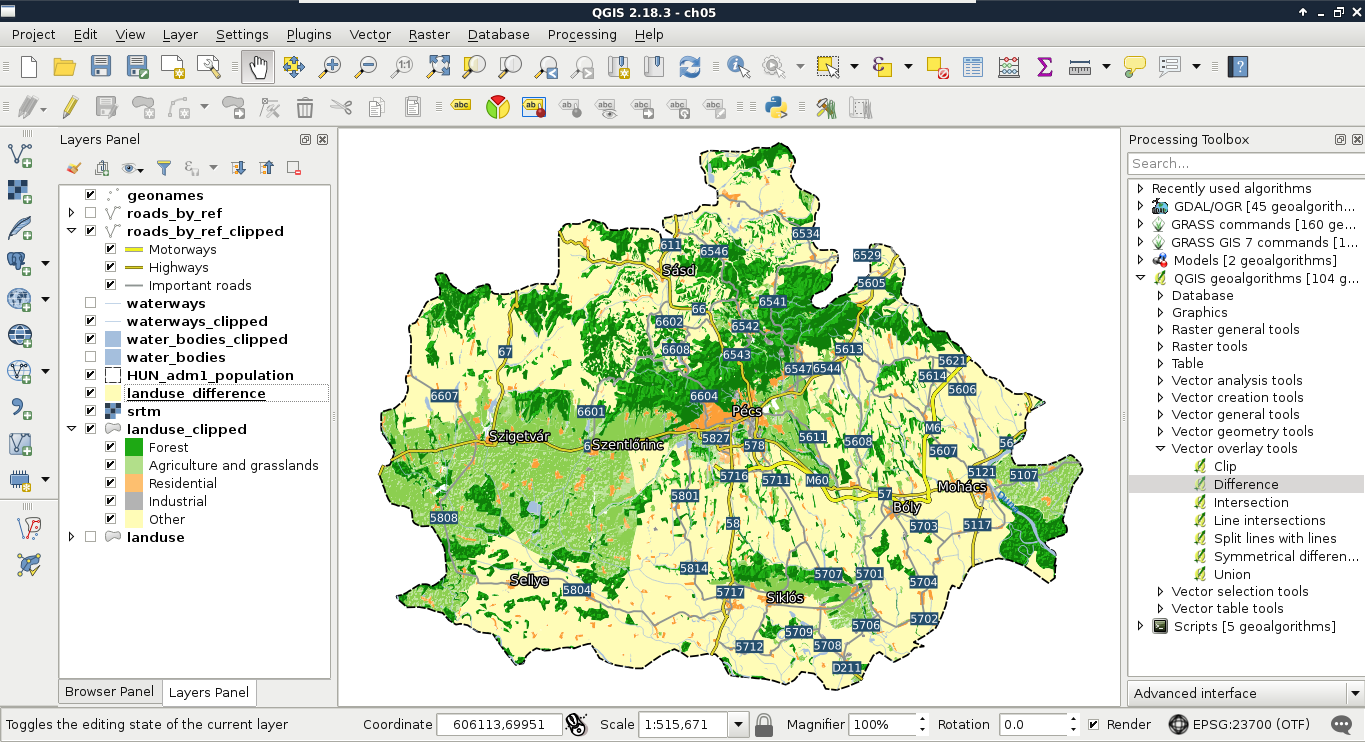

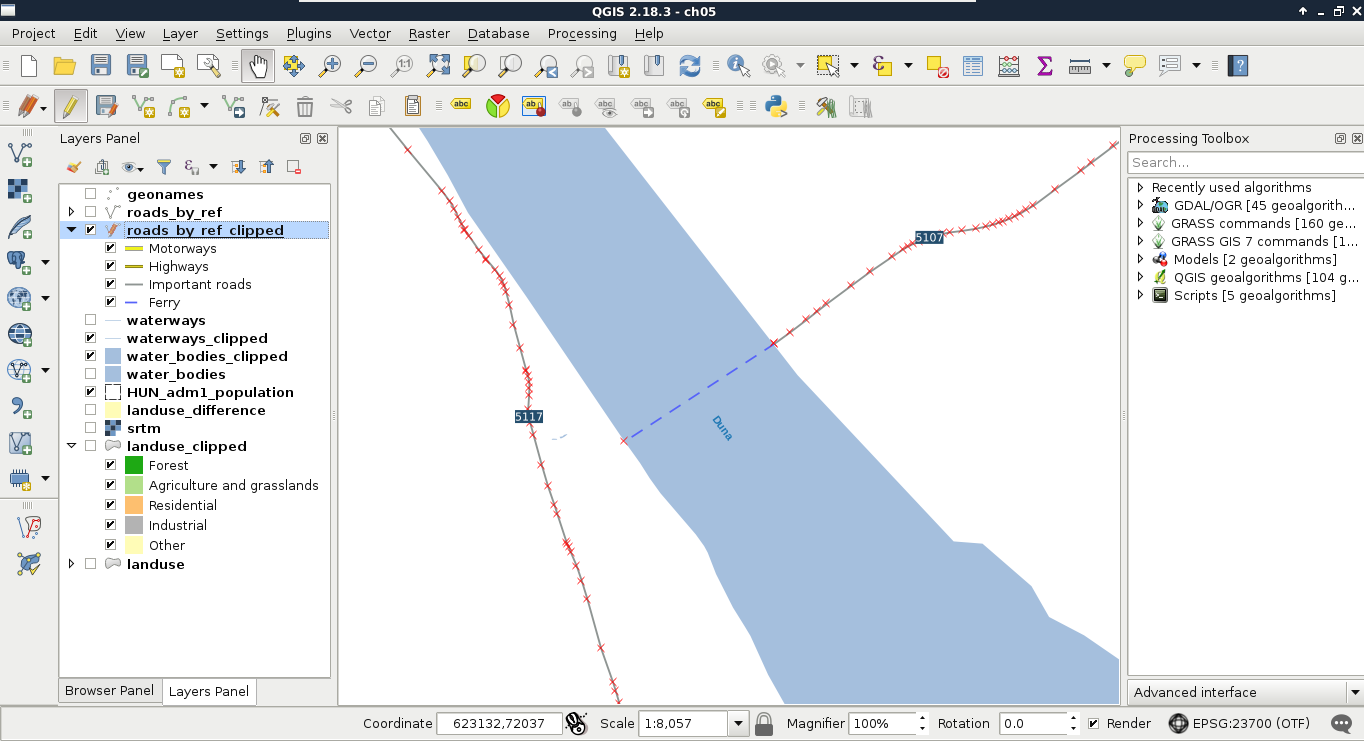

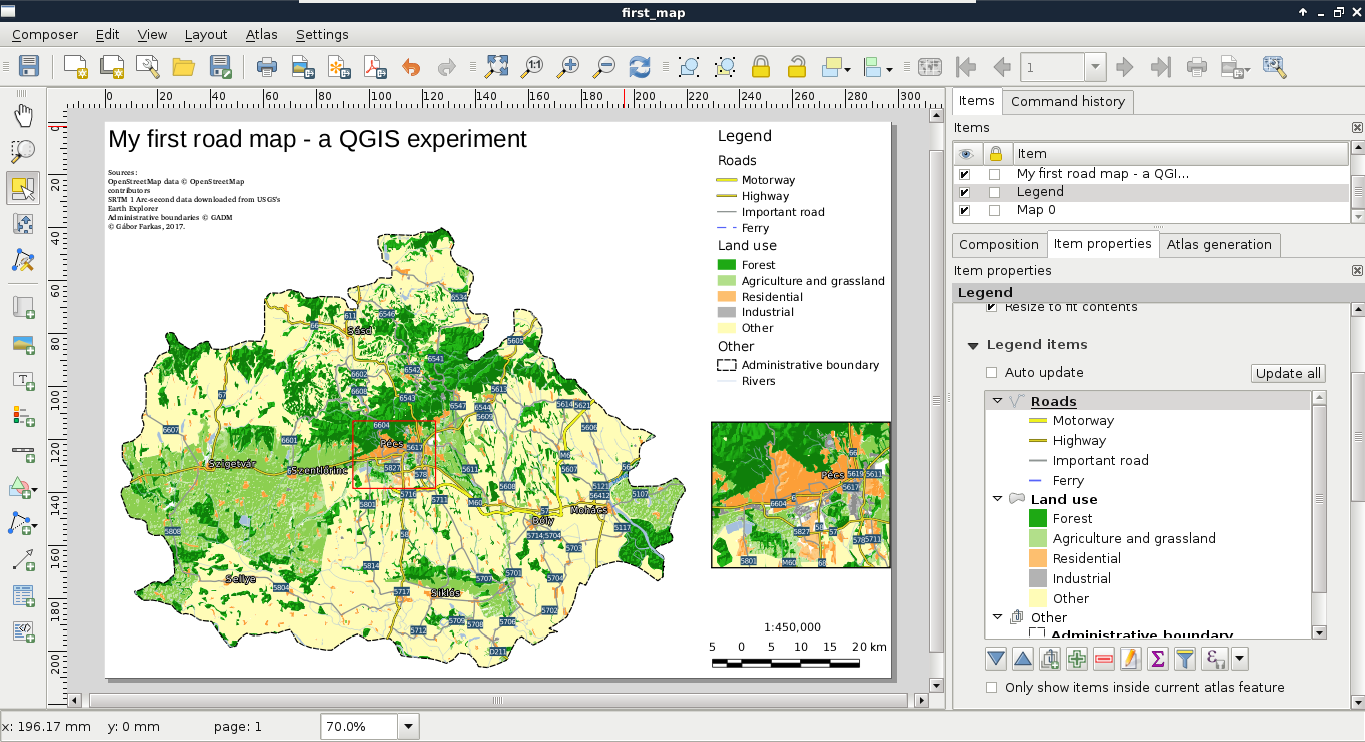

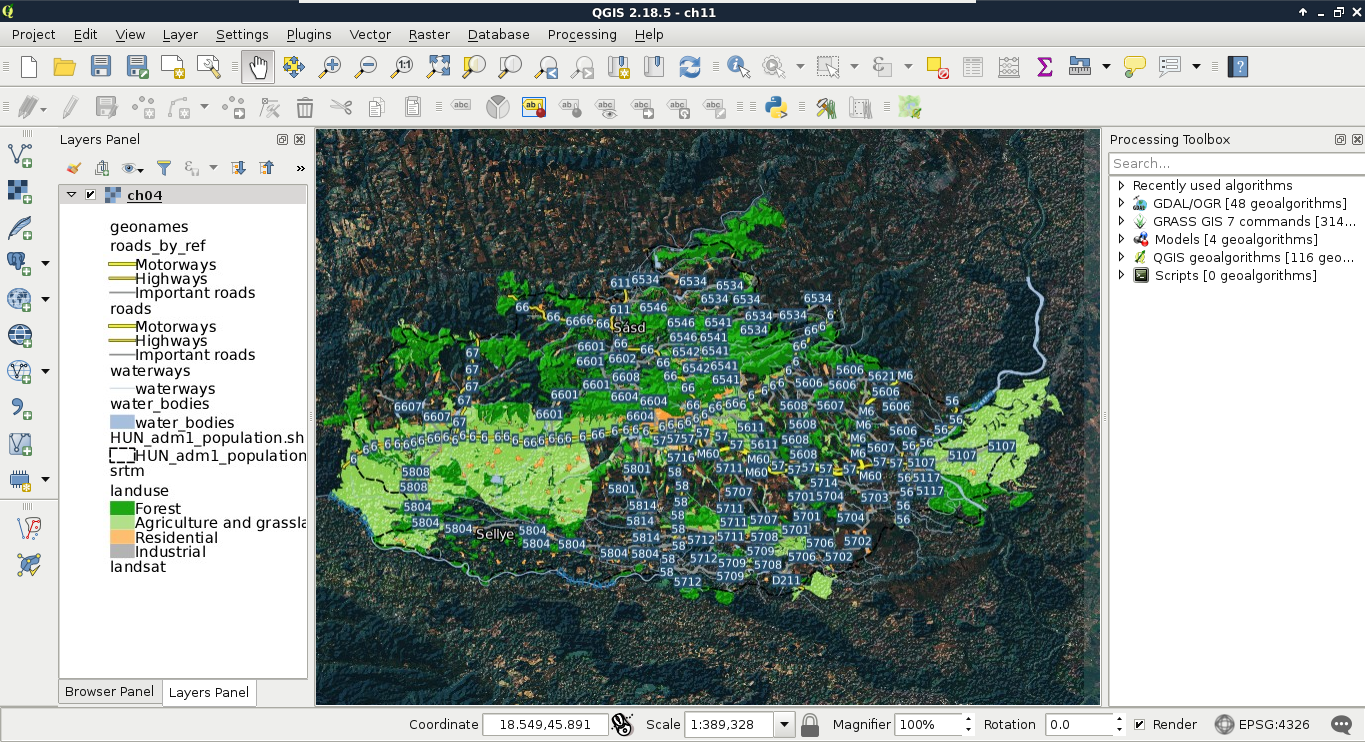

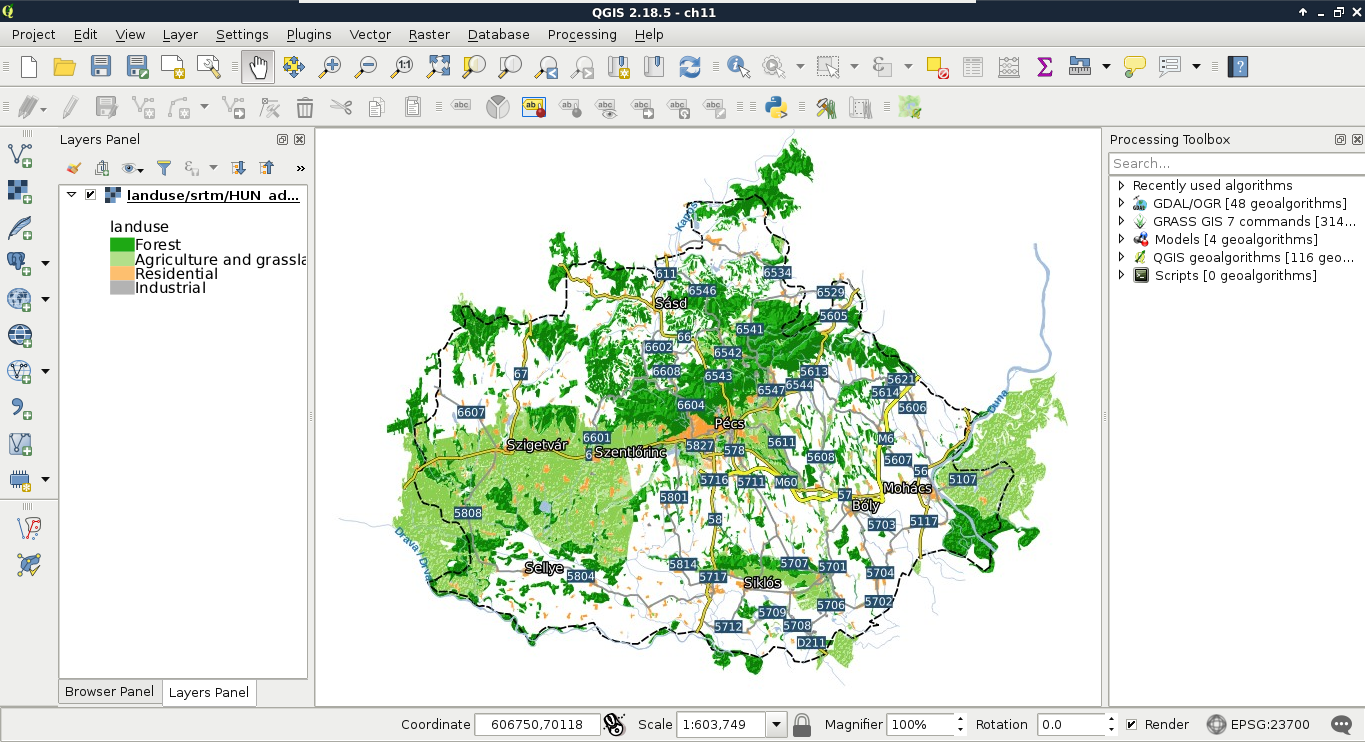

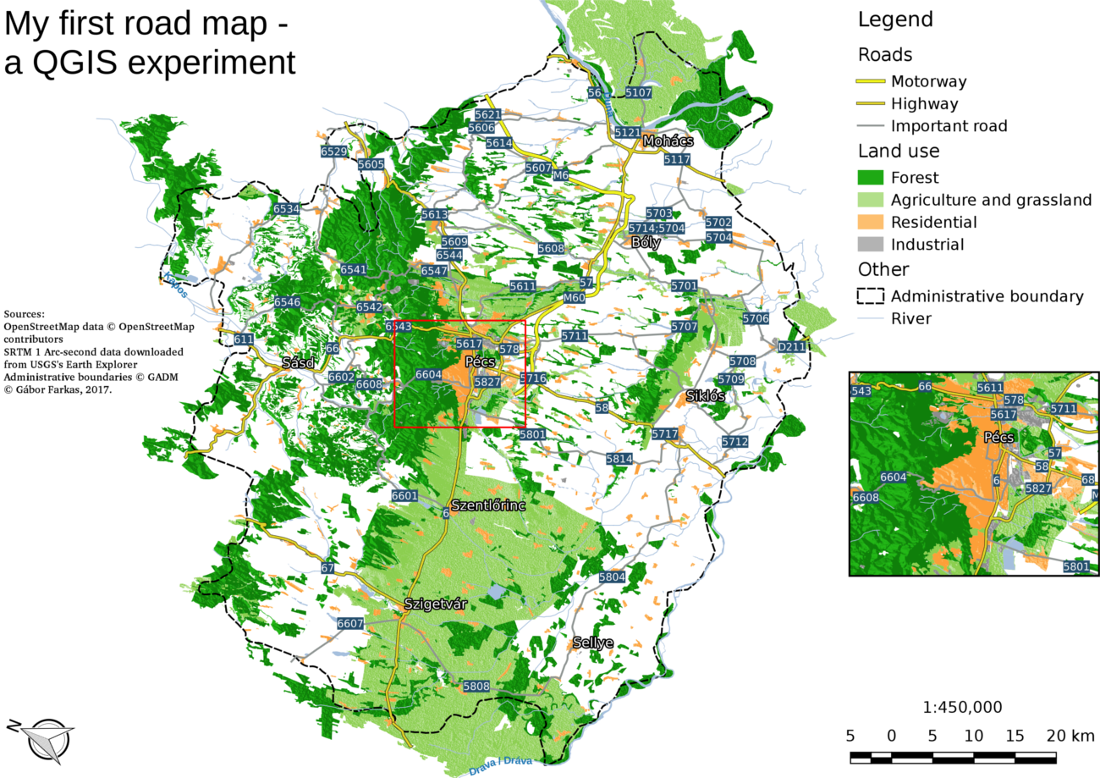

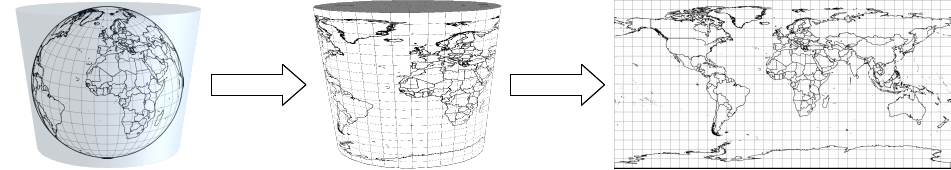

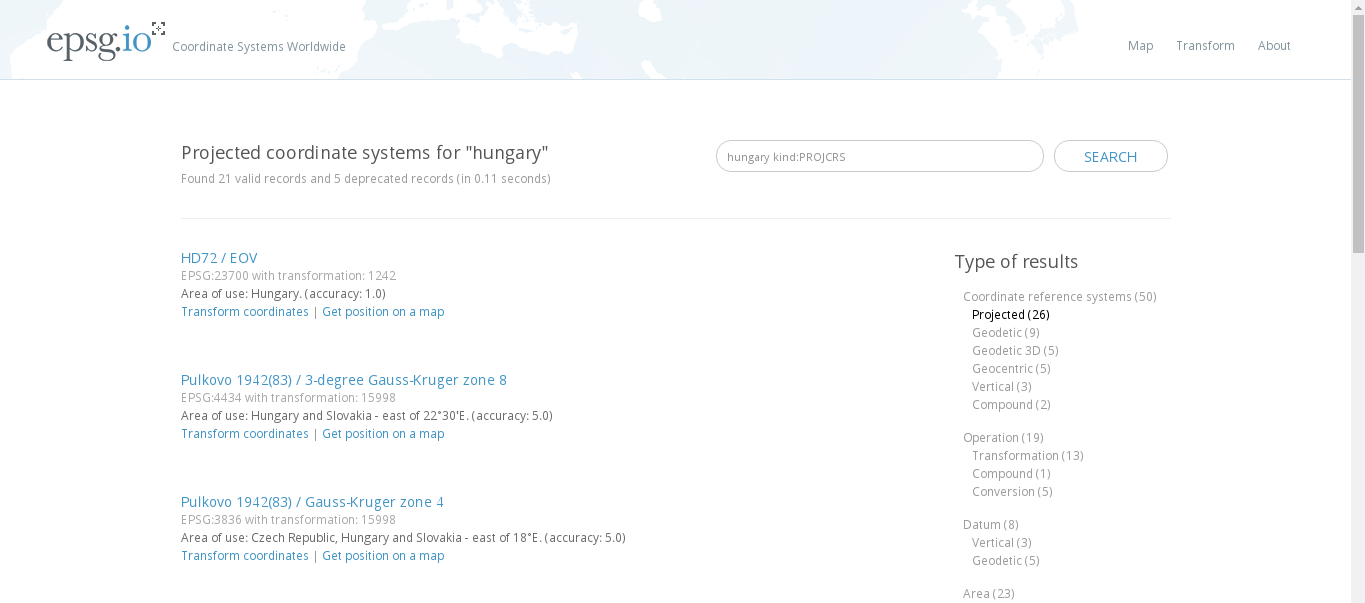

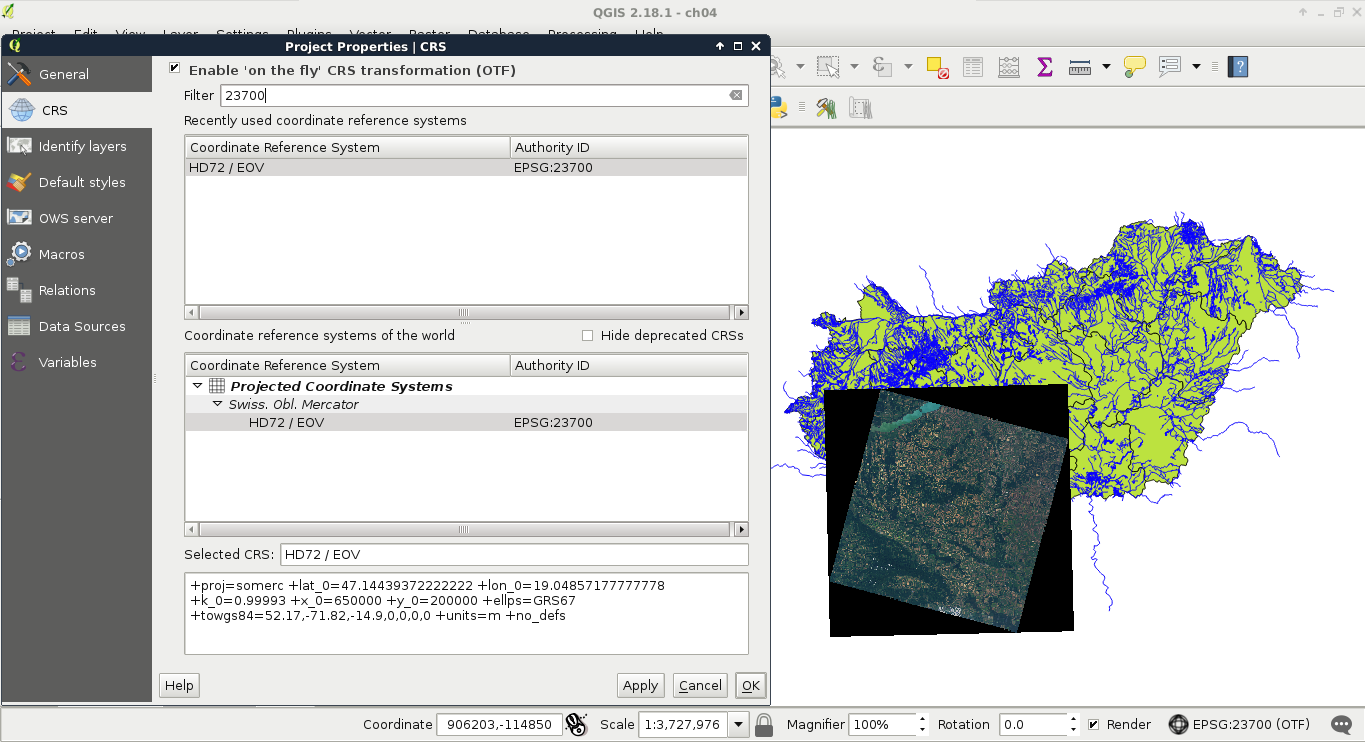

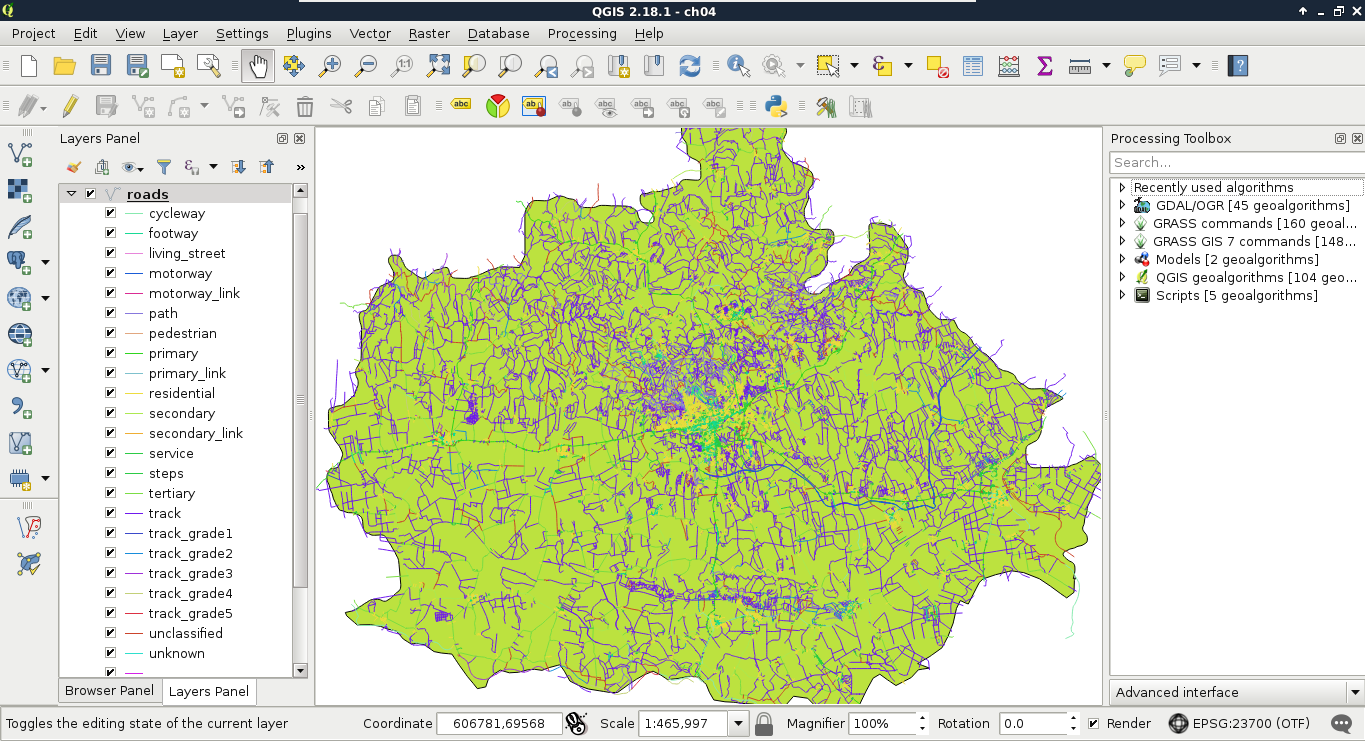

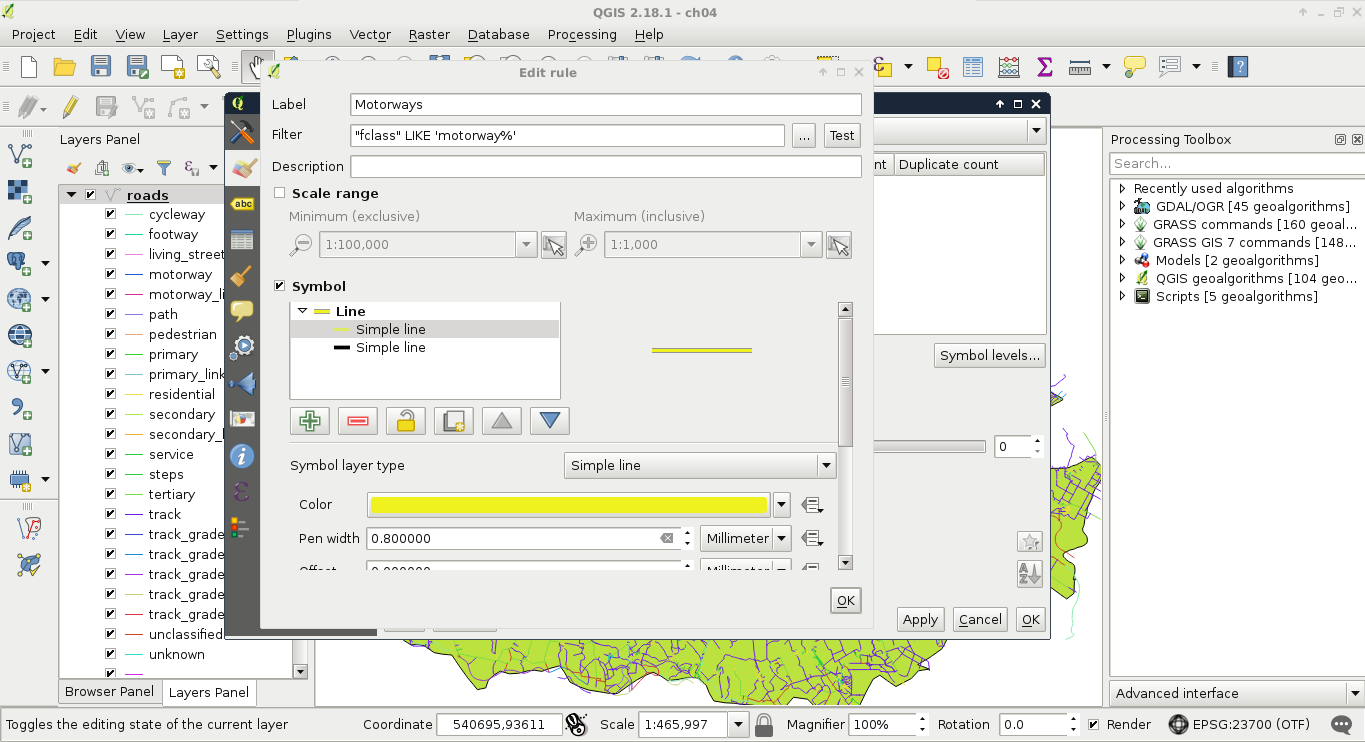

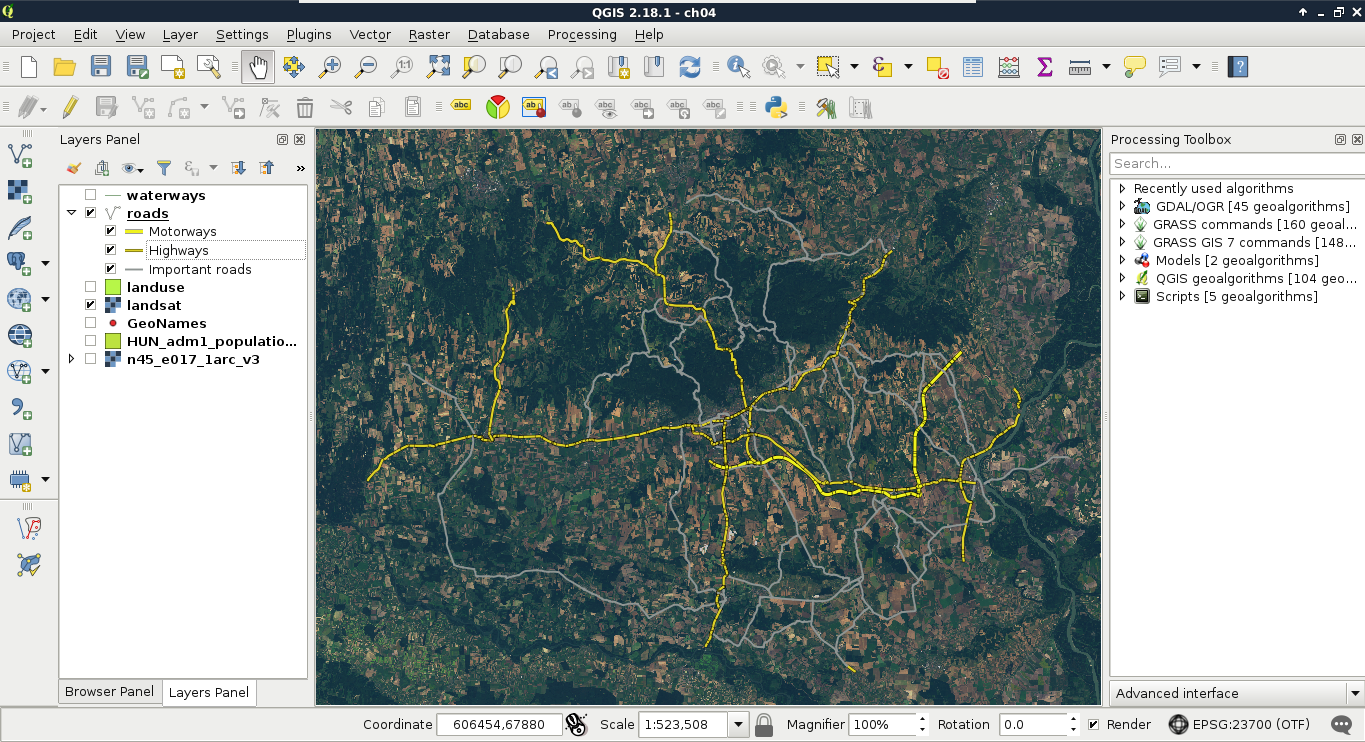

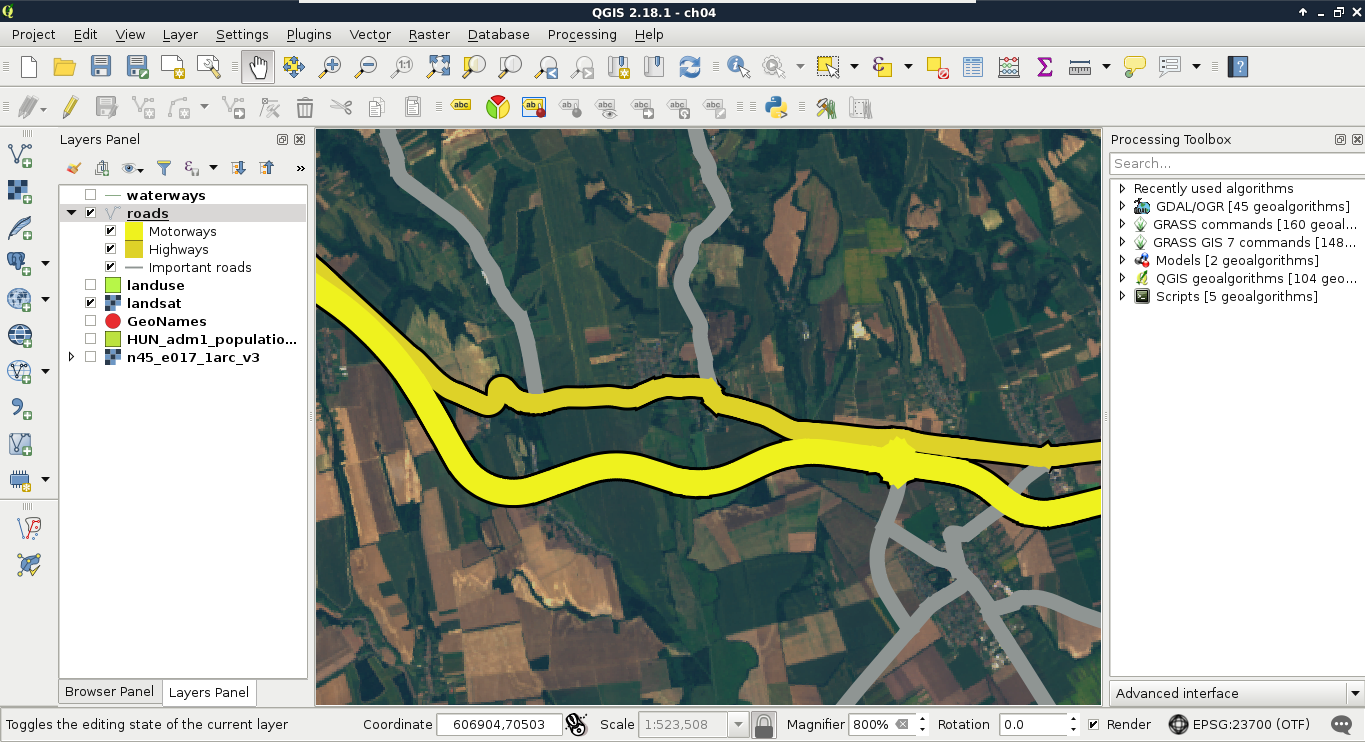

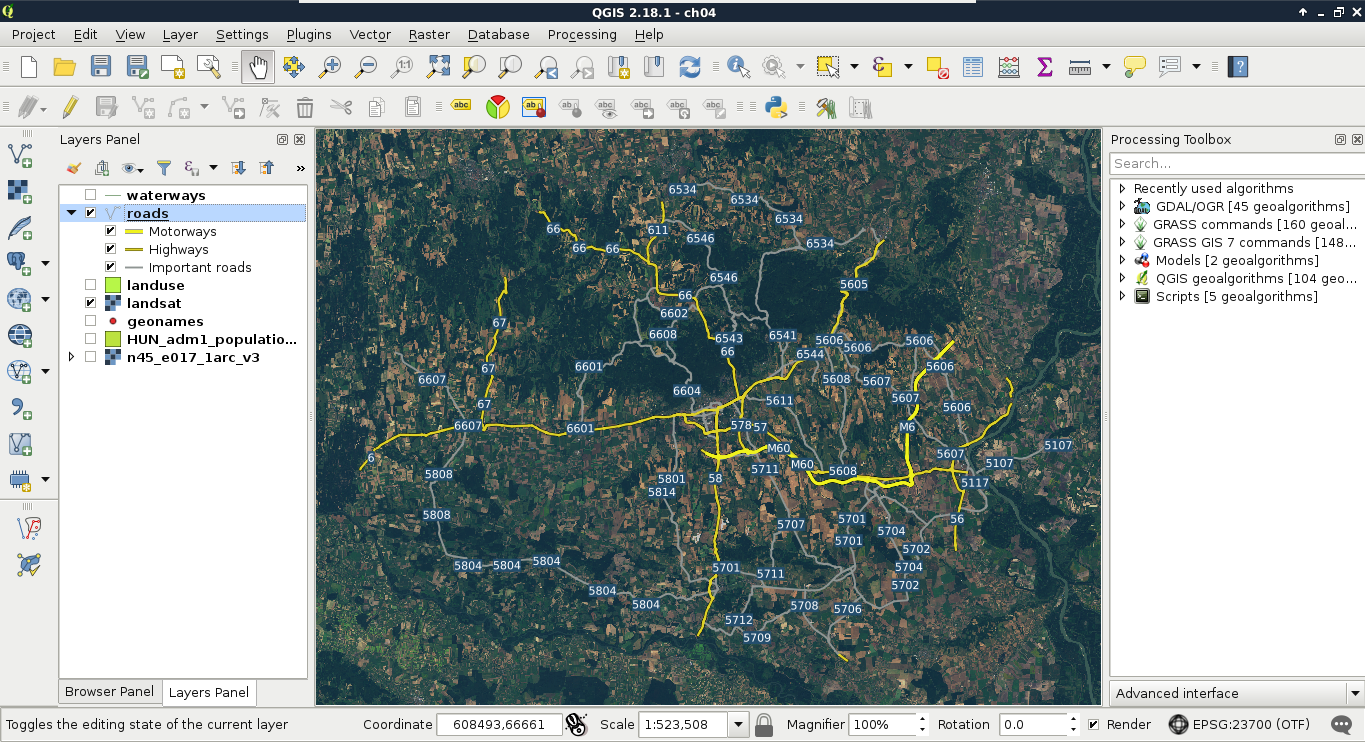

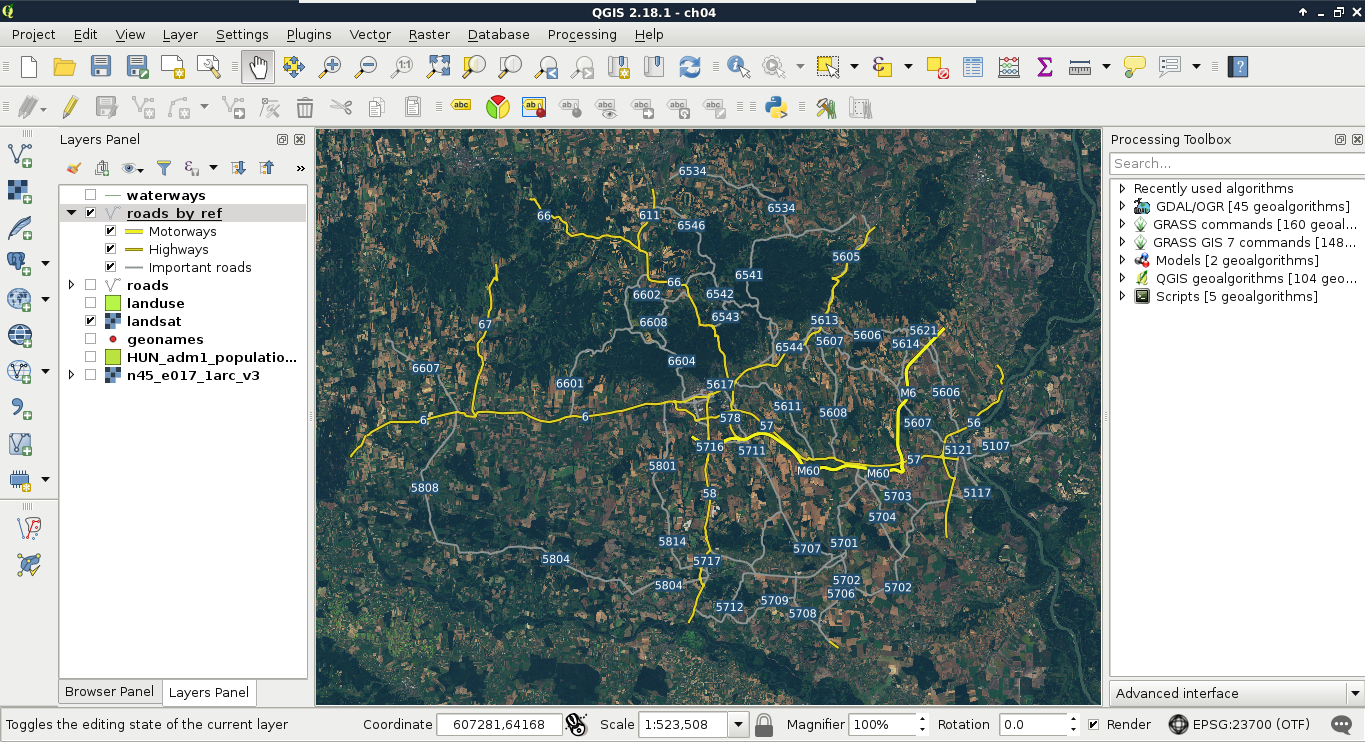

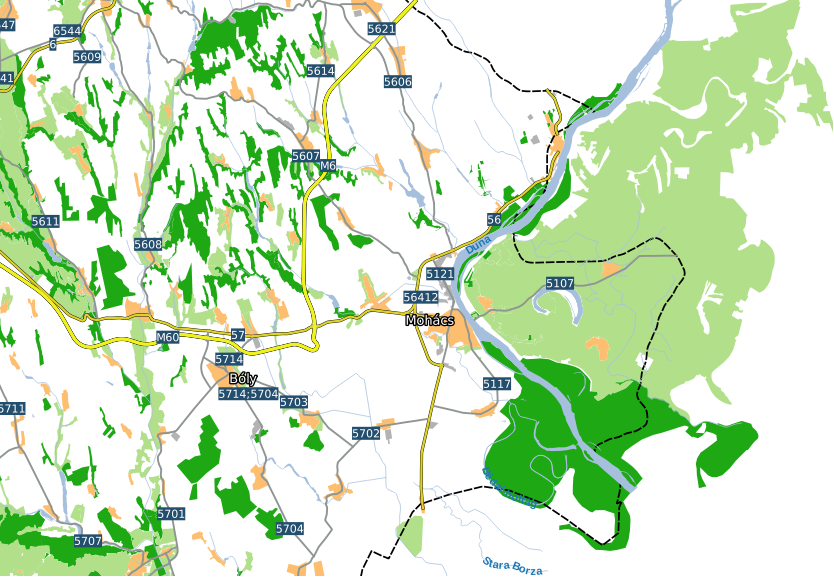

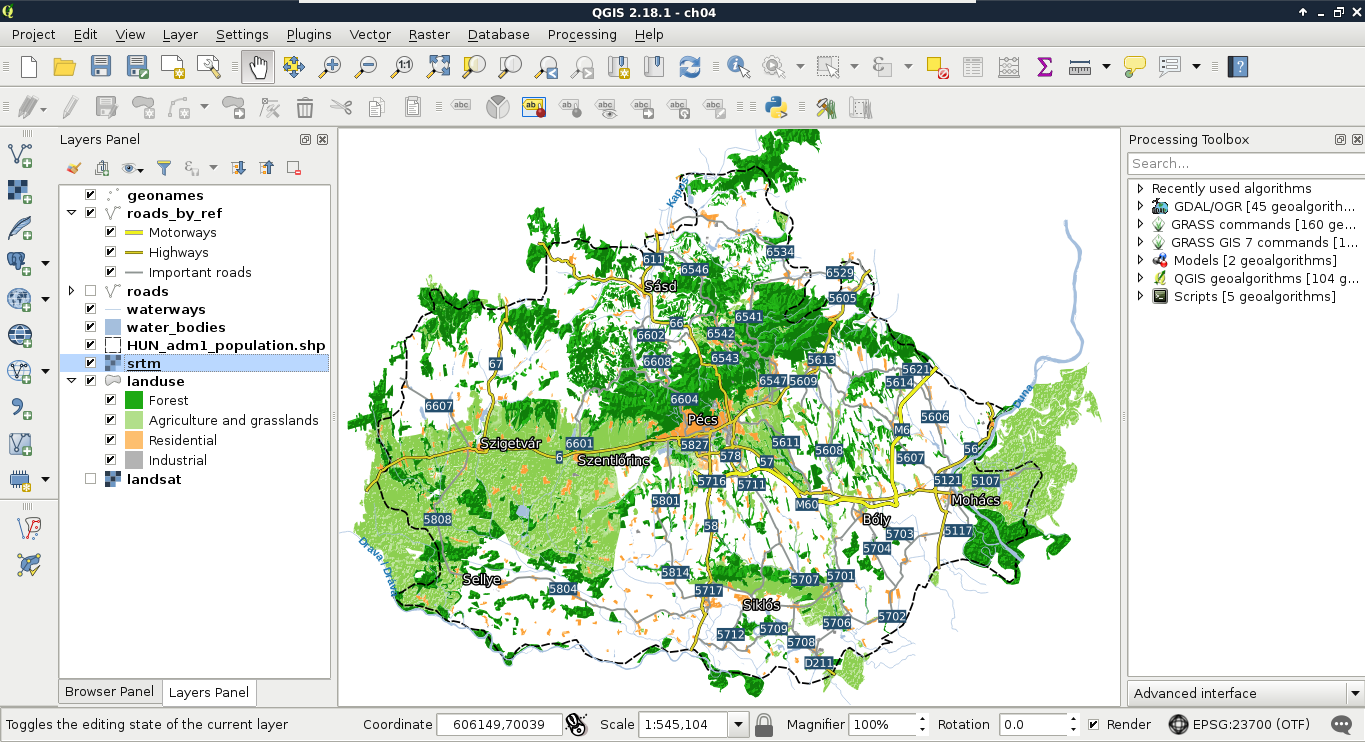

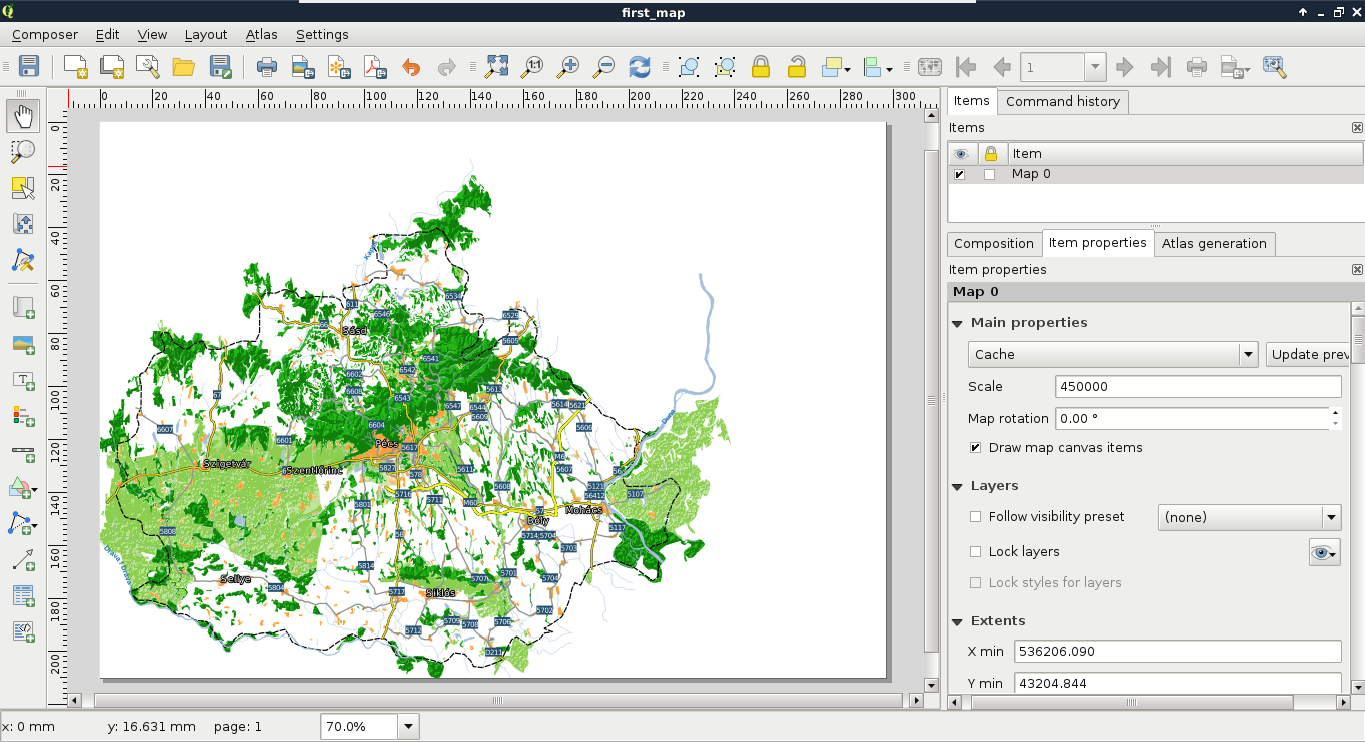

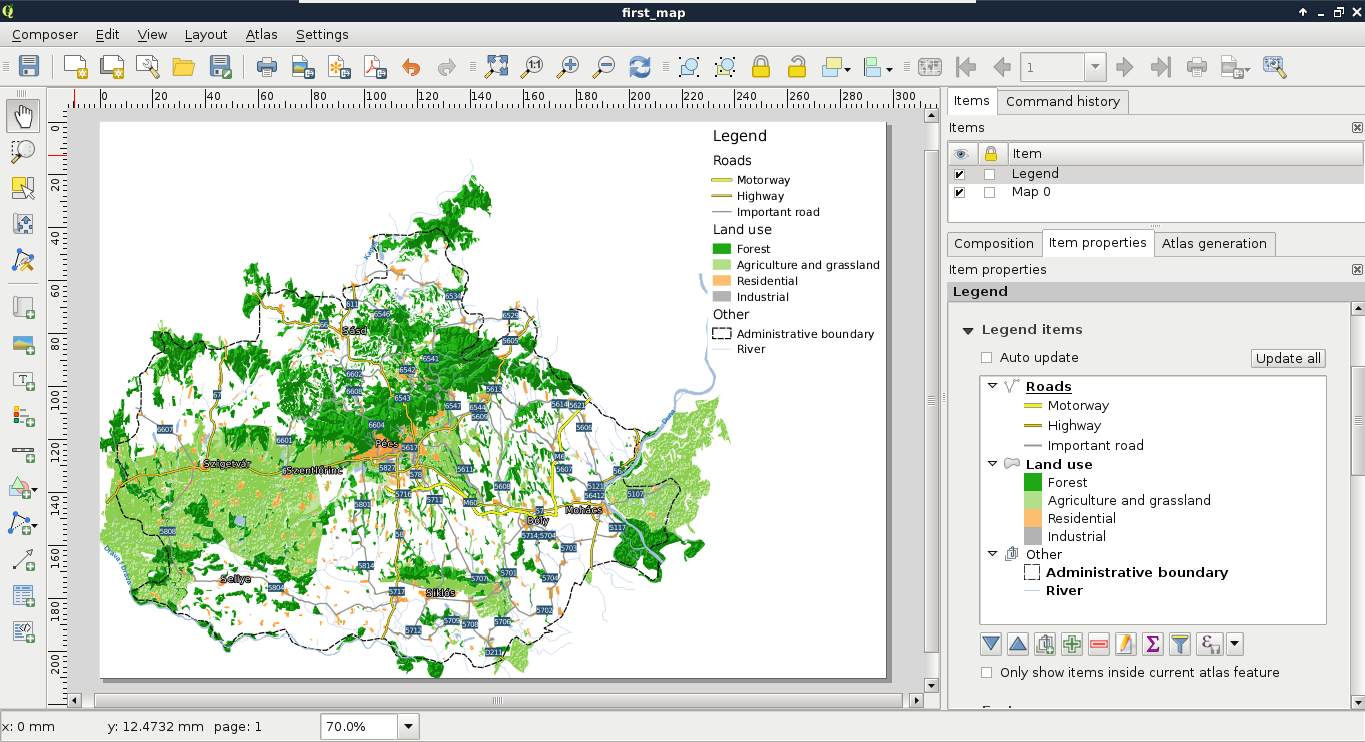

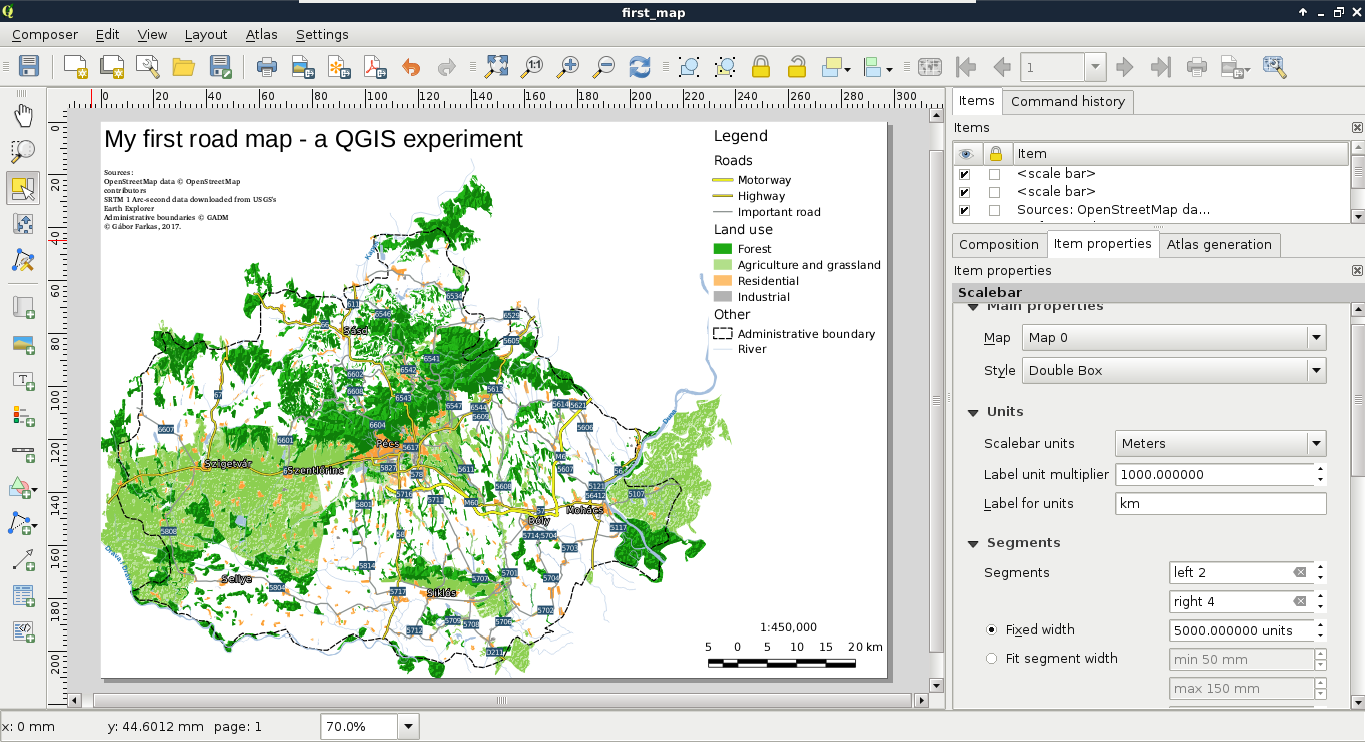

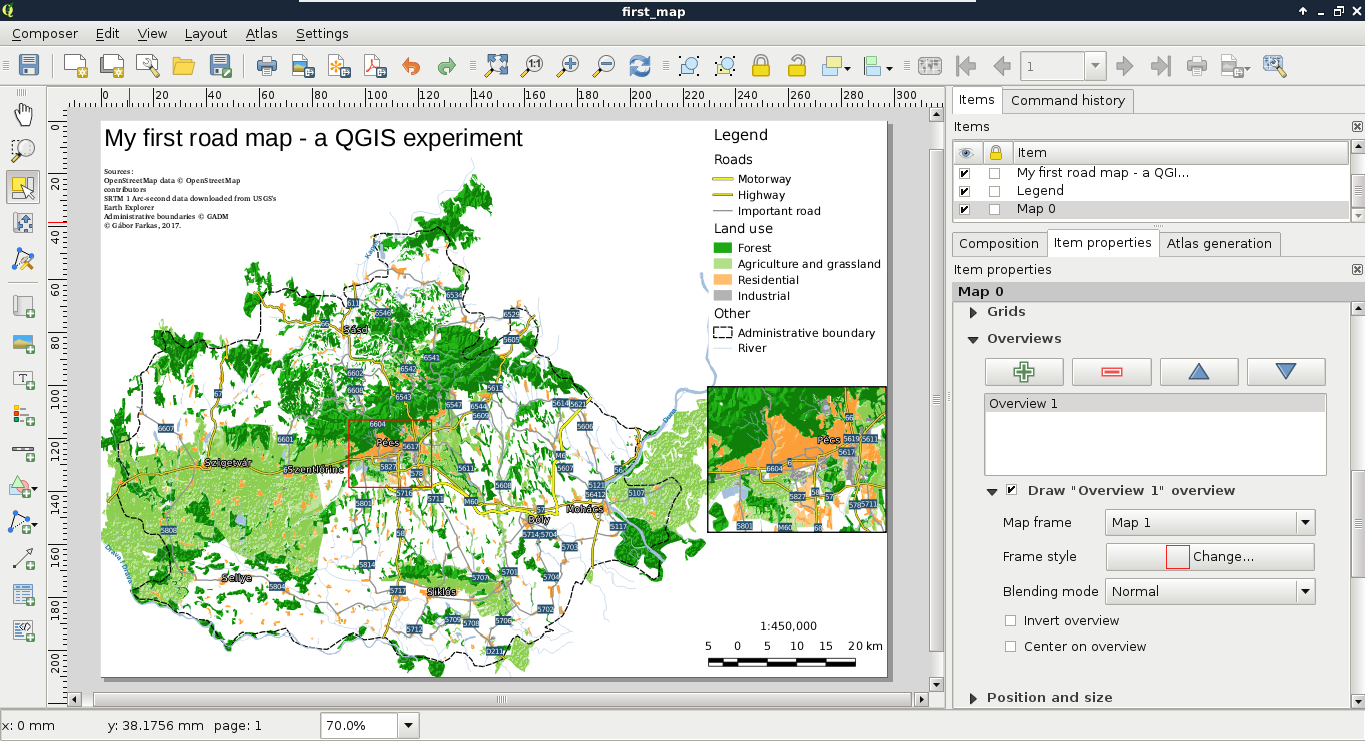

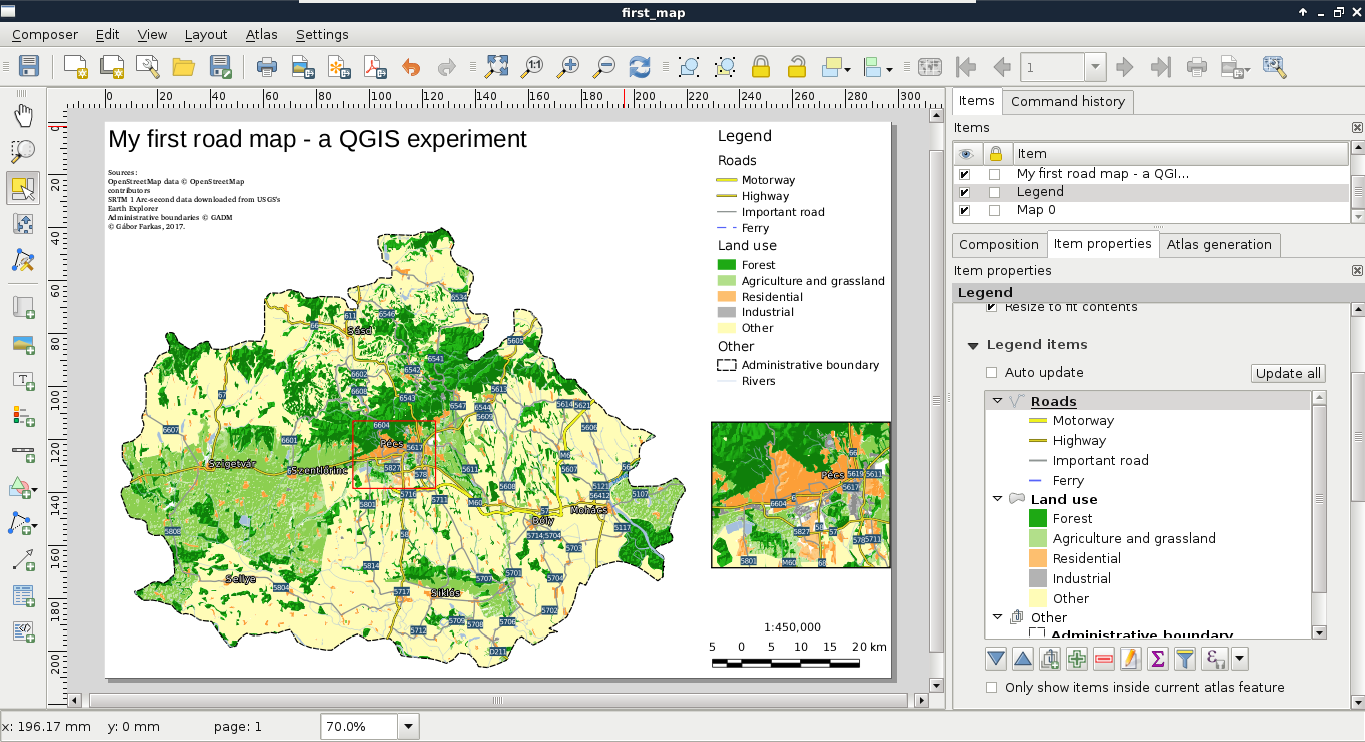

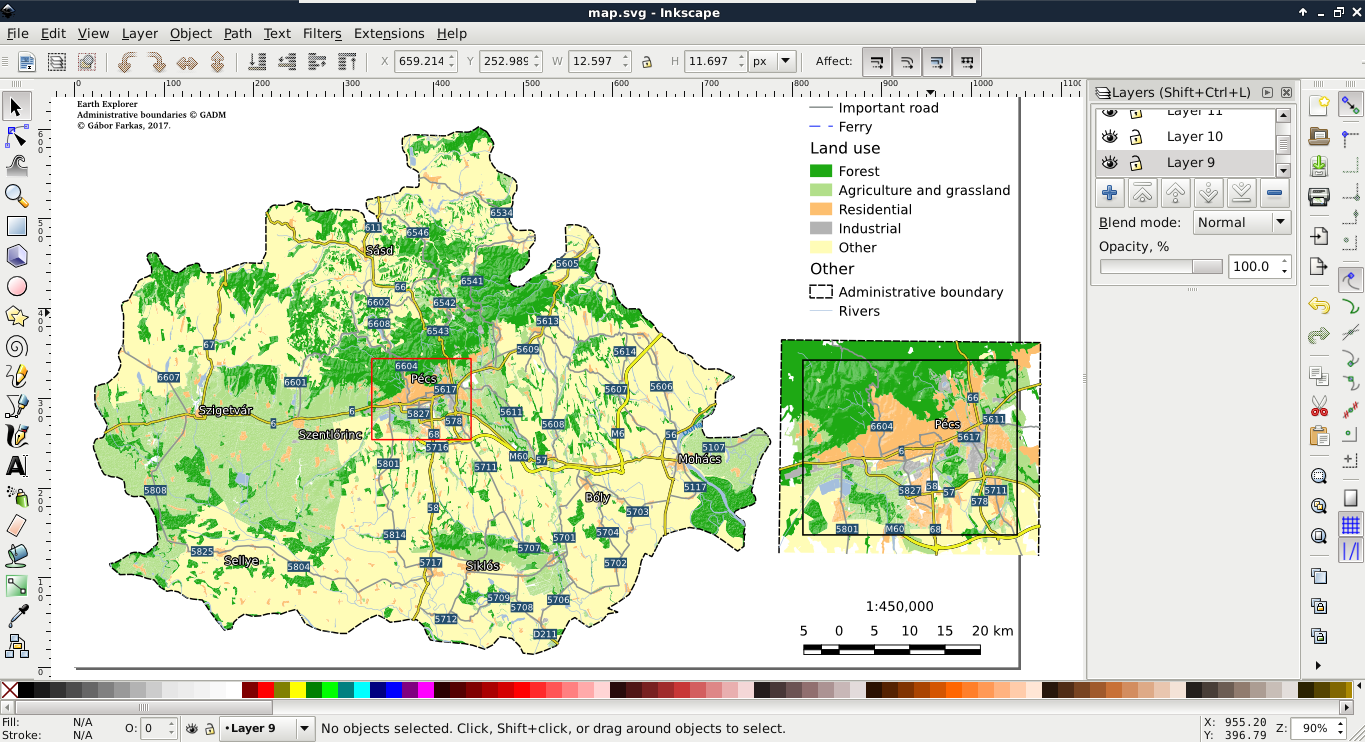

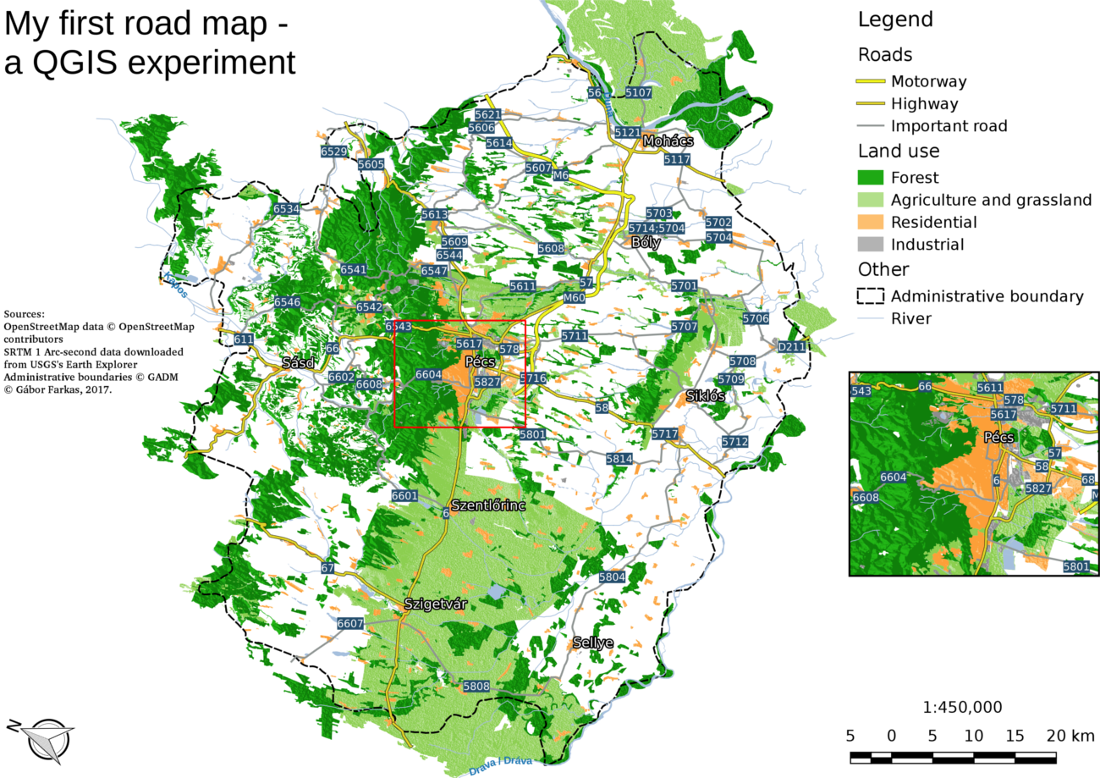

Chapter 4, Creating Digital Maps, discusses the basics of digital map making by going through an exhaustive yet simple example in QGIS. It introduces you to the concept of projections and spatial reference systems, and the various steps of creating a digital map.

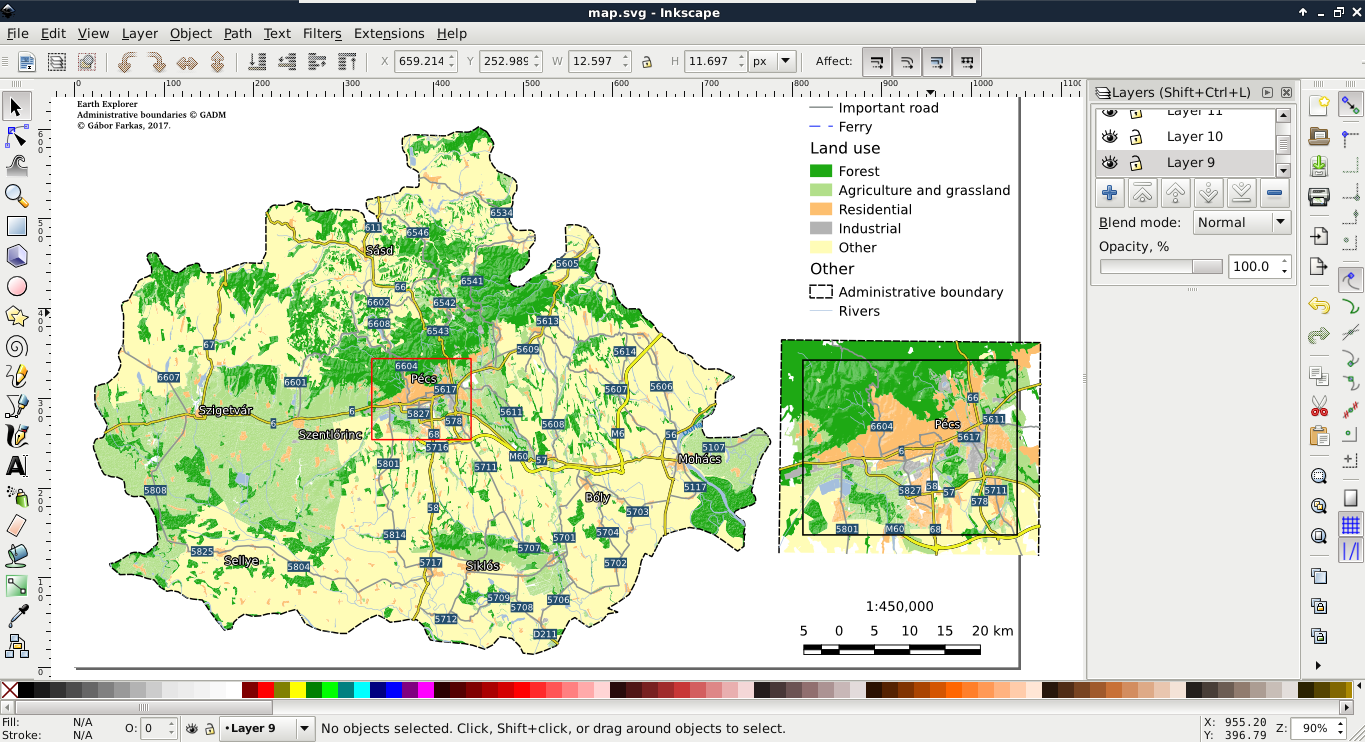

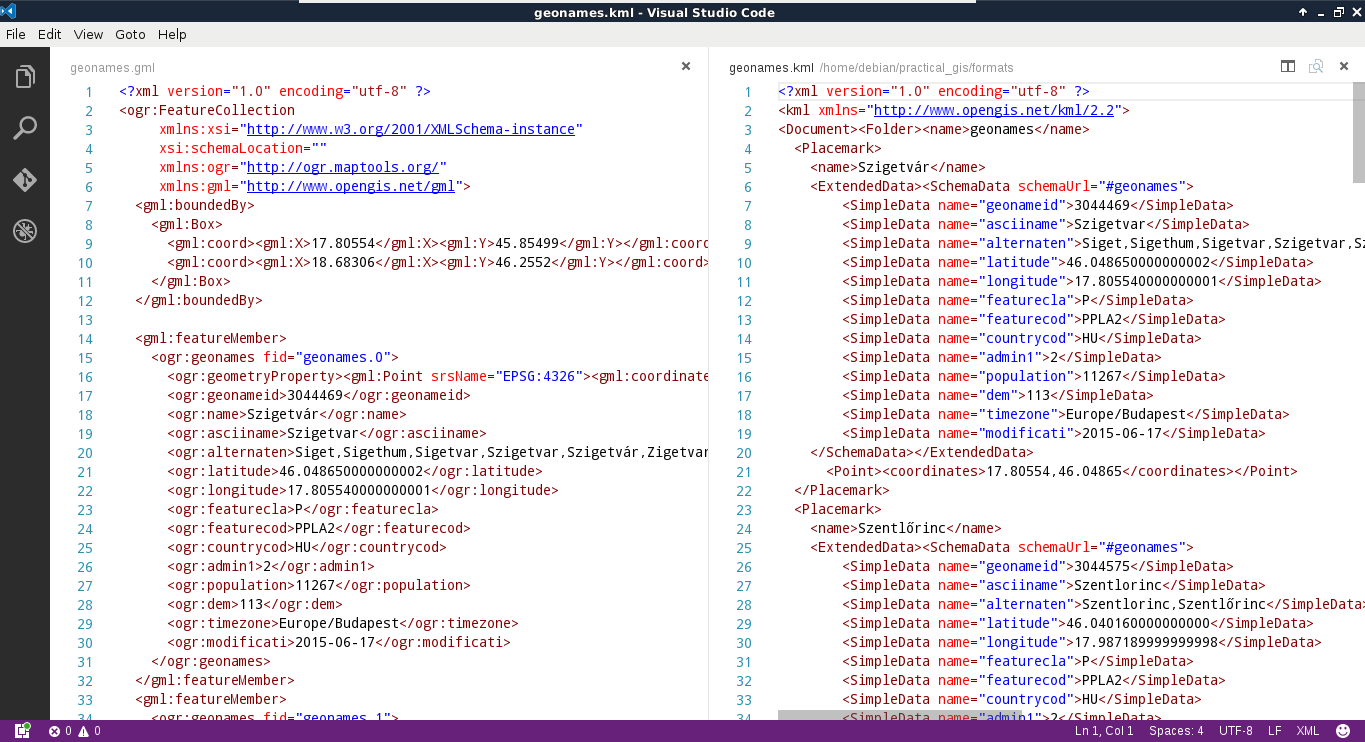

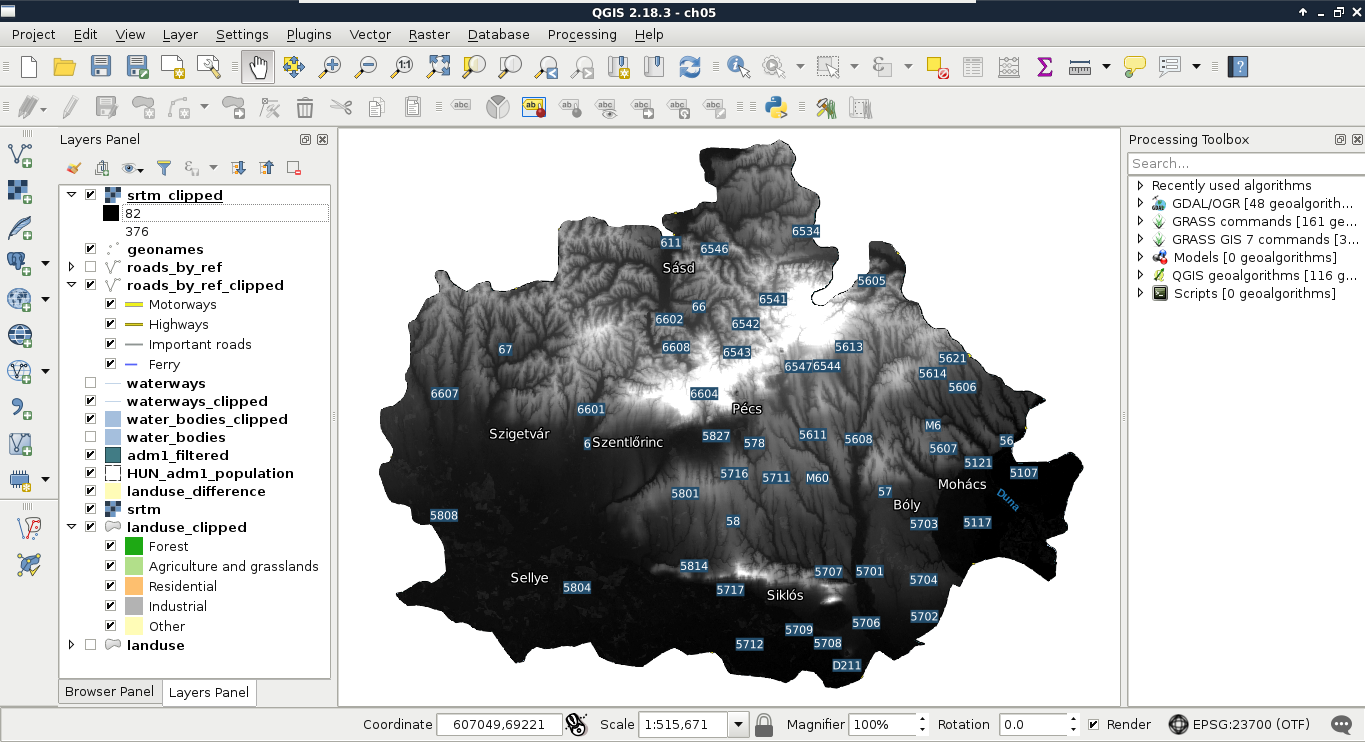

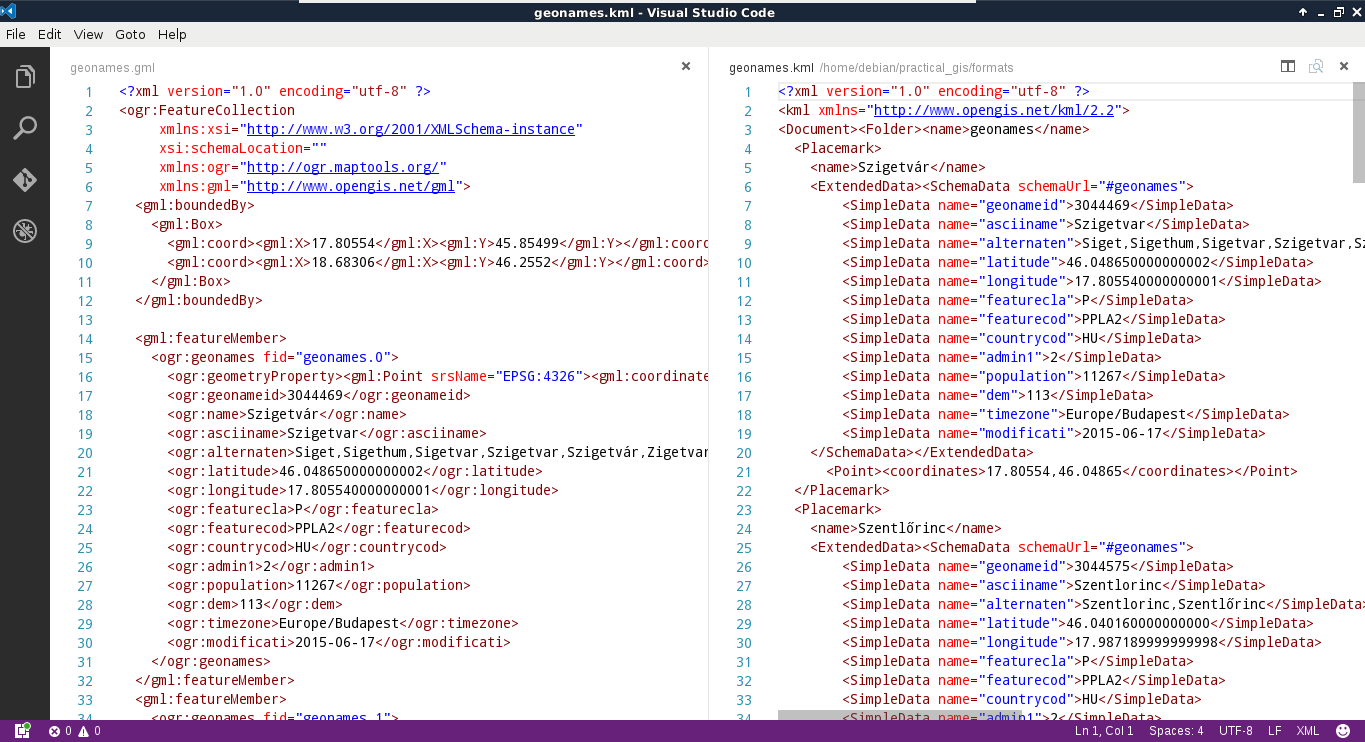

Chapter 5, Exporting Your Data, guides you through the most widely used vector and raster data formats in GIS. It discusses the strengths and weaknesses of the various formats, and also gives you some insight on under what circumstances you should choose a particular spatial data format.

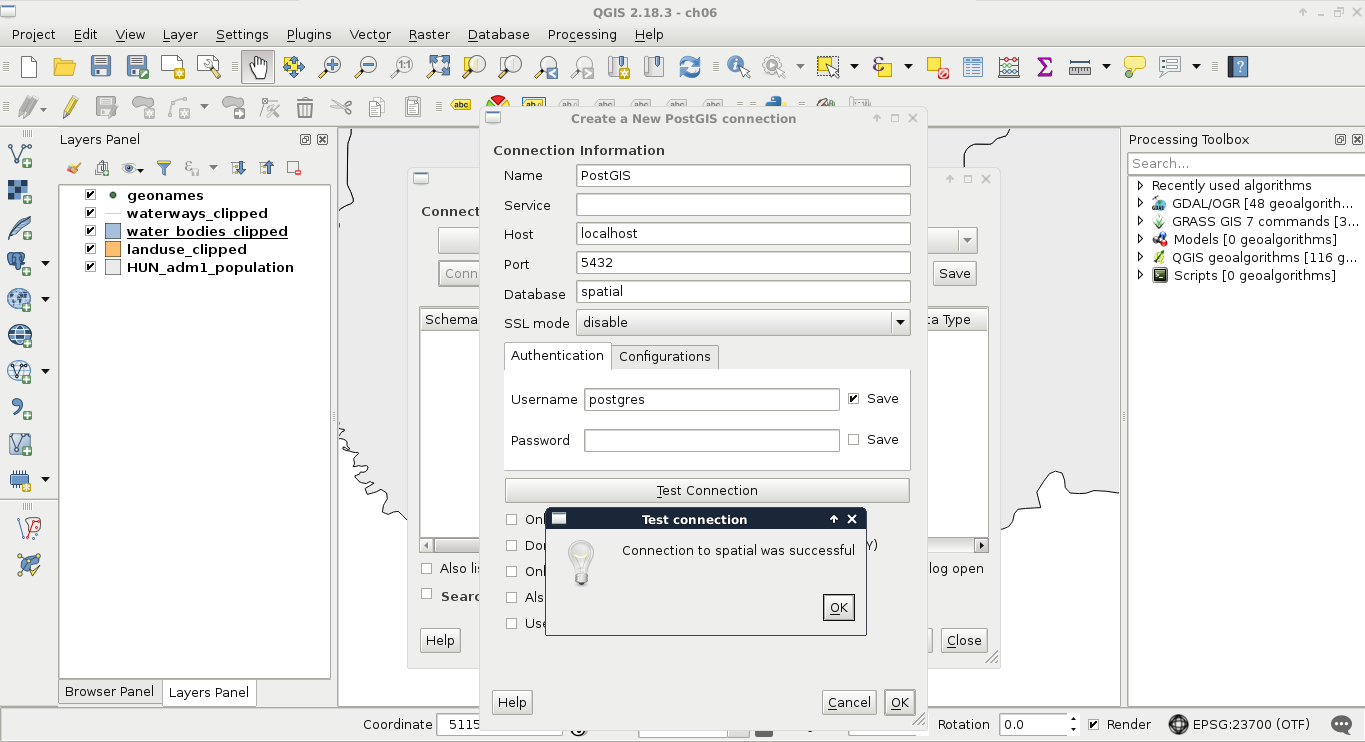

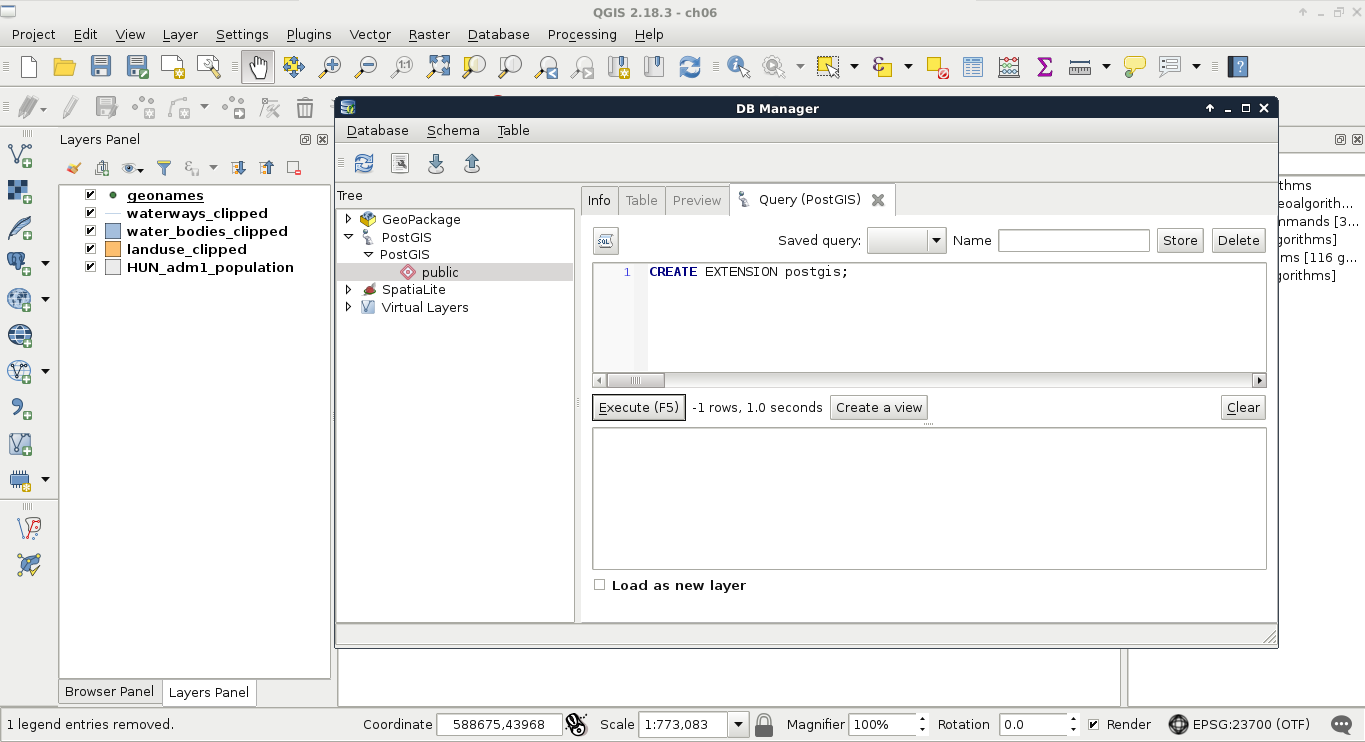

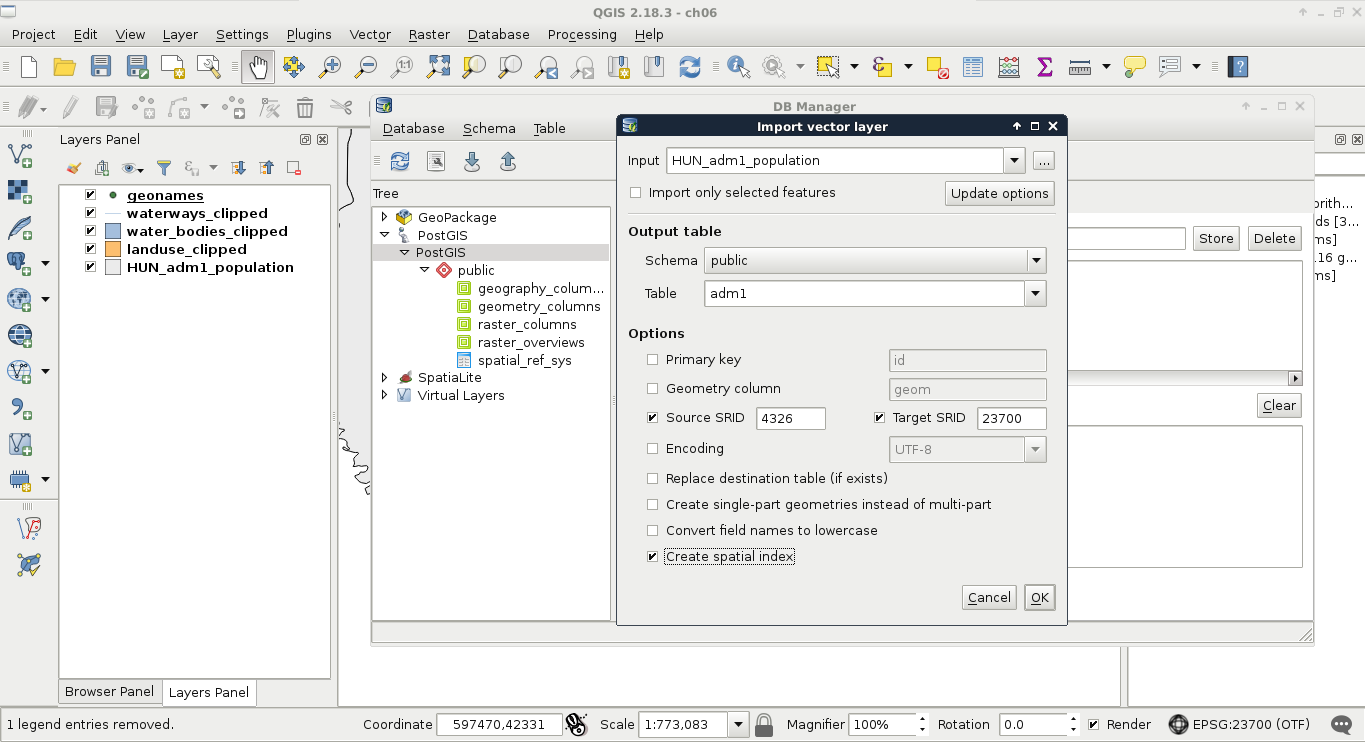

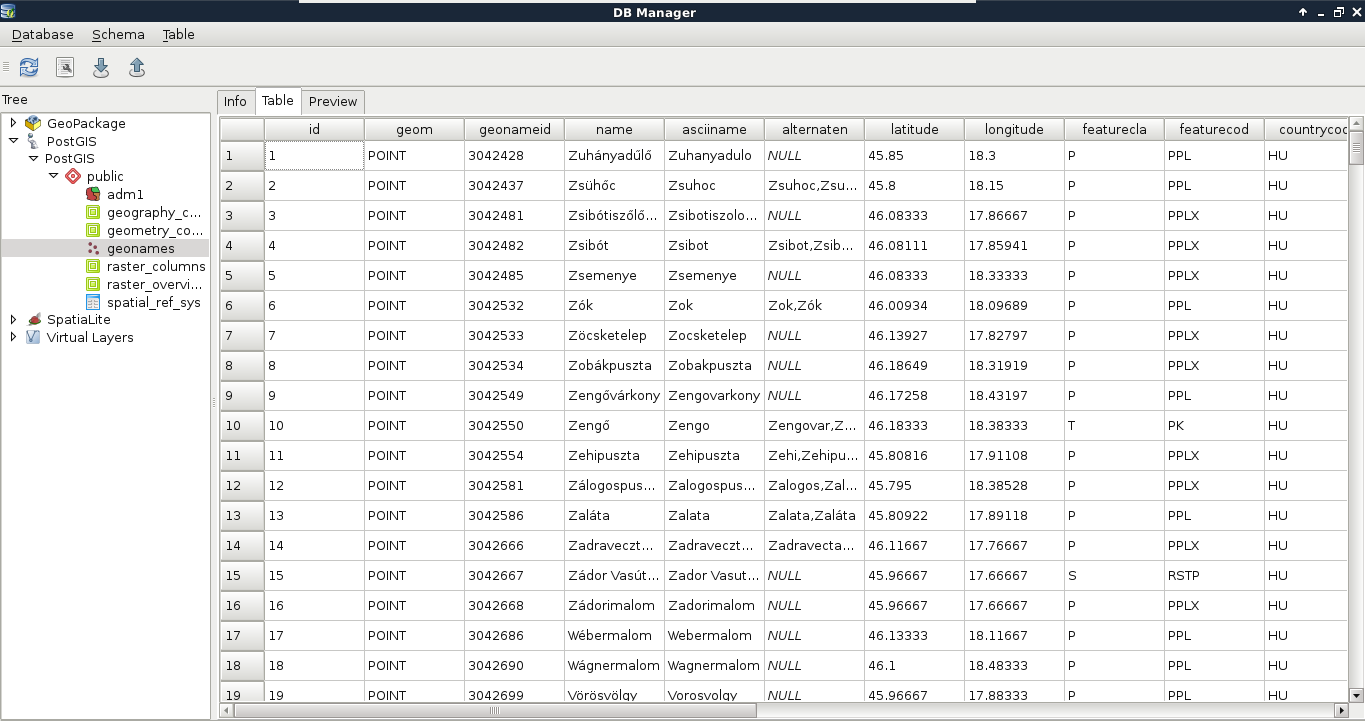

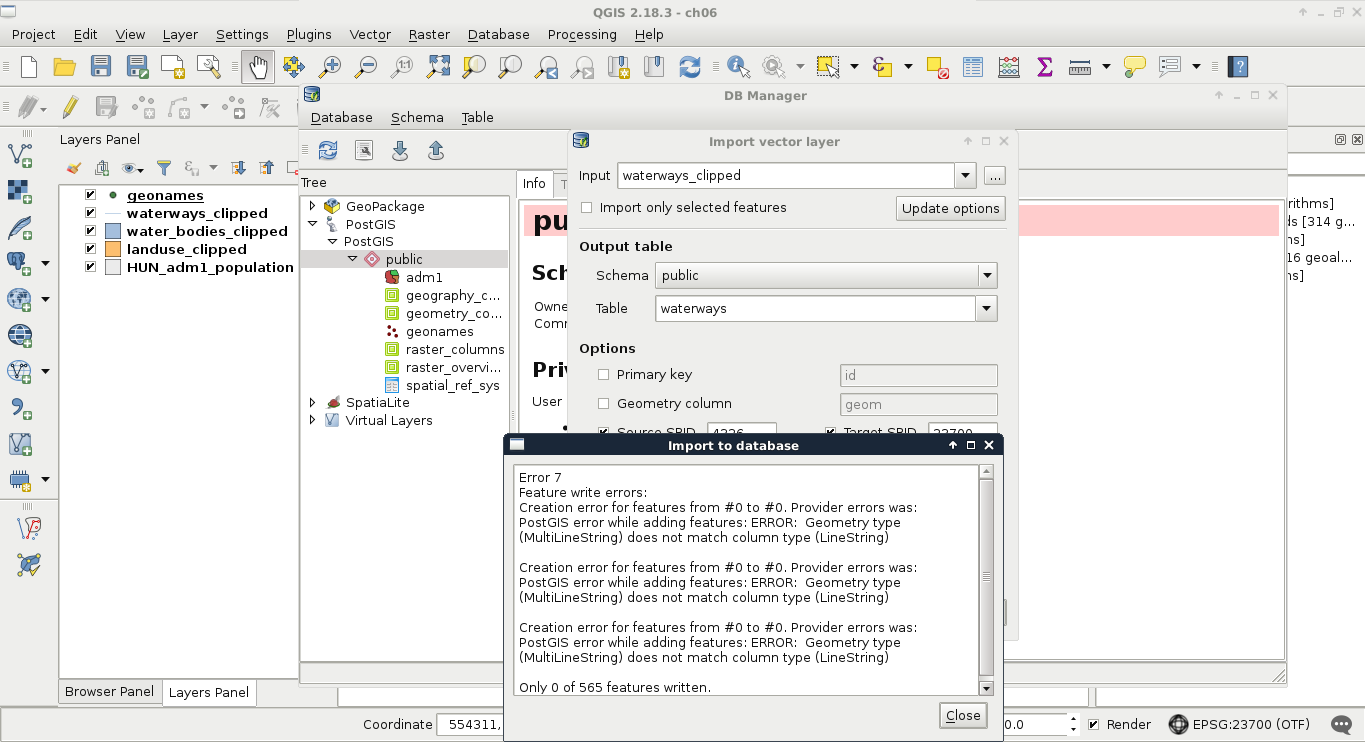

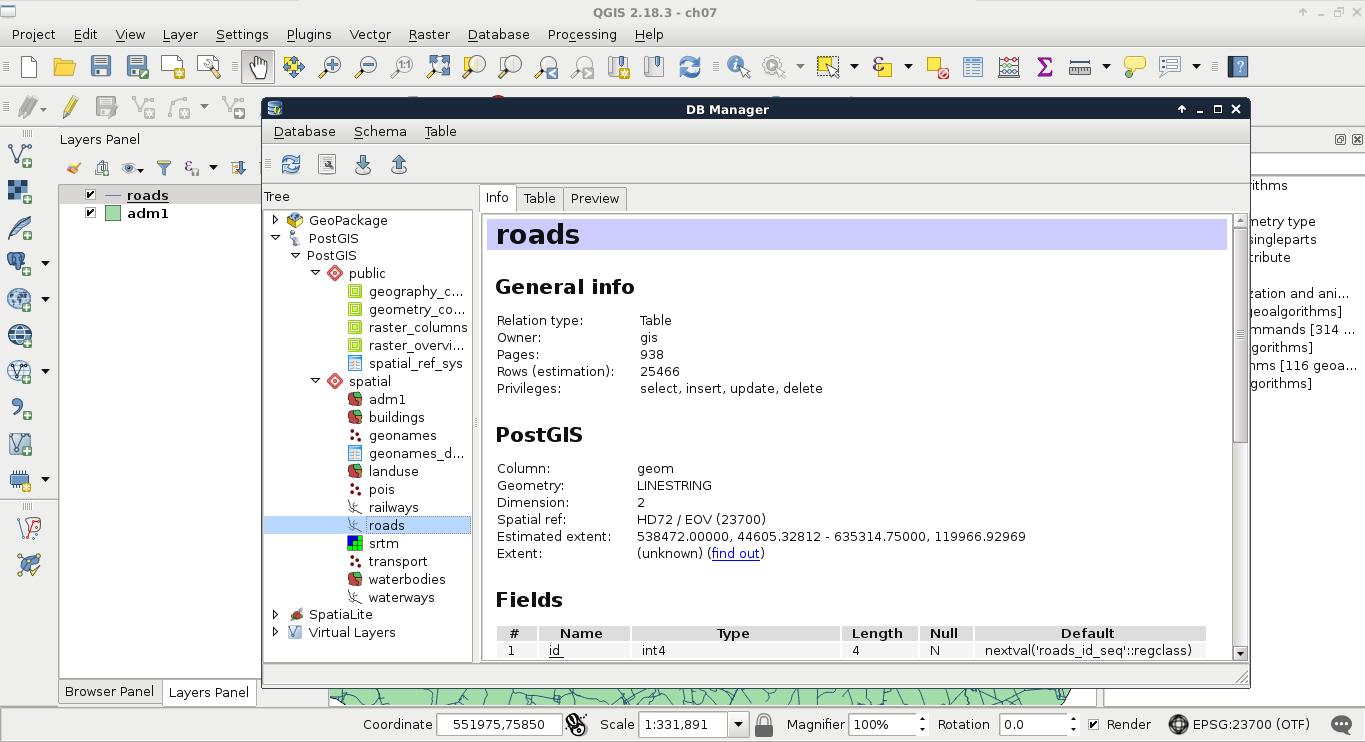

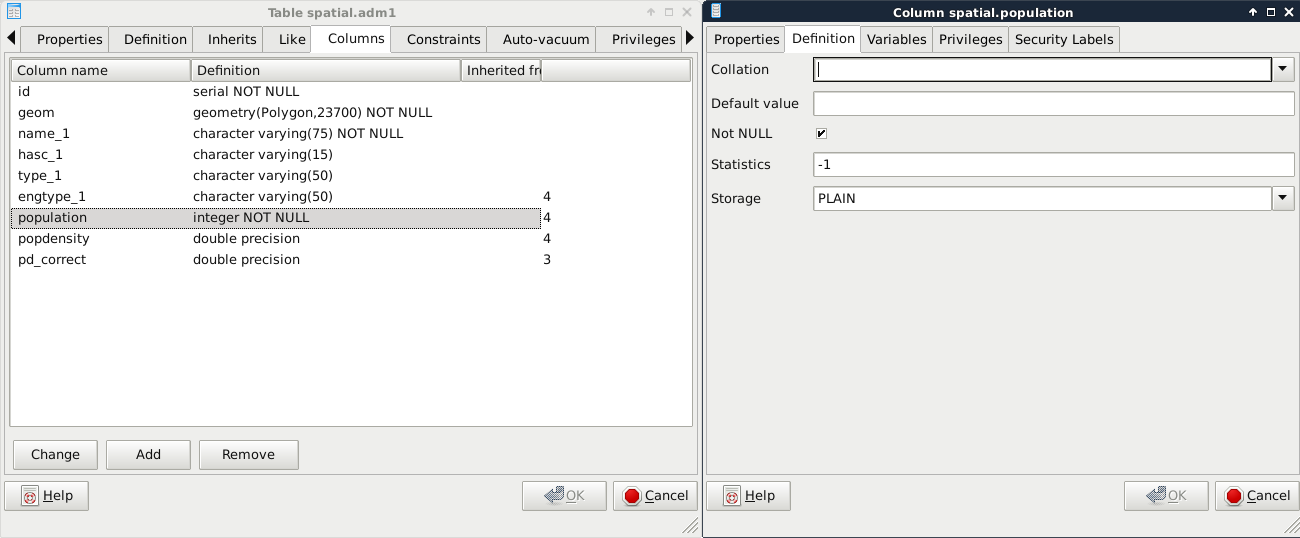

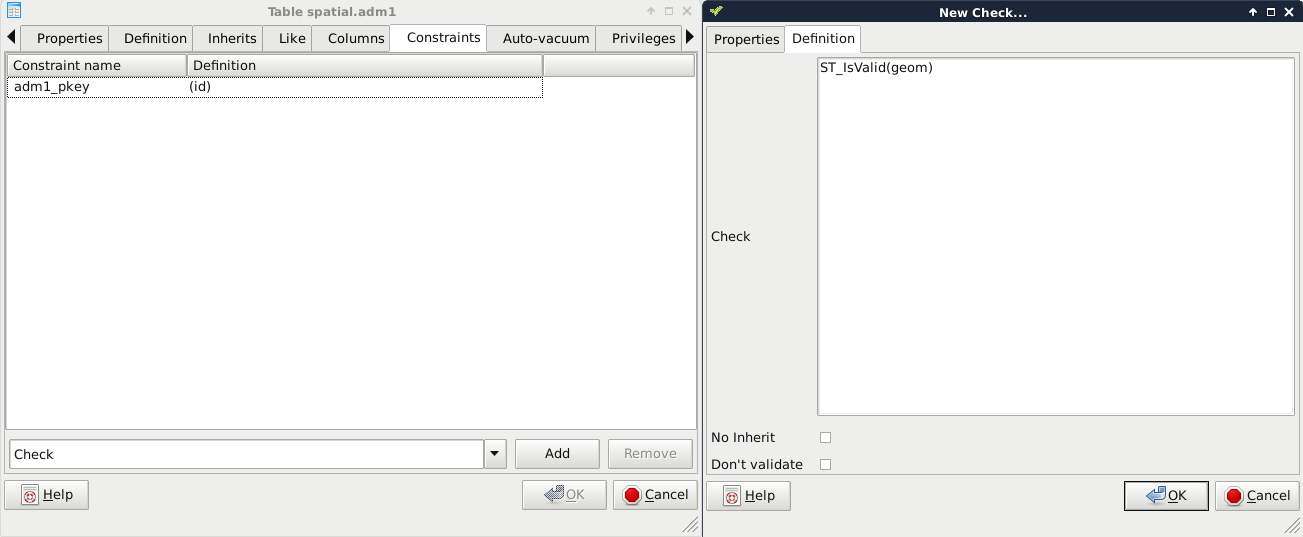

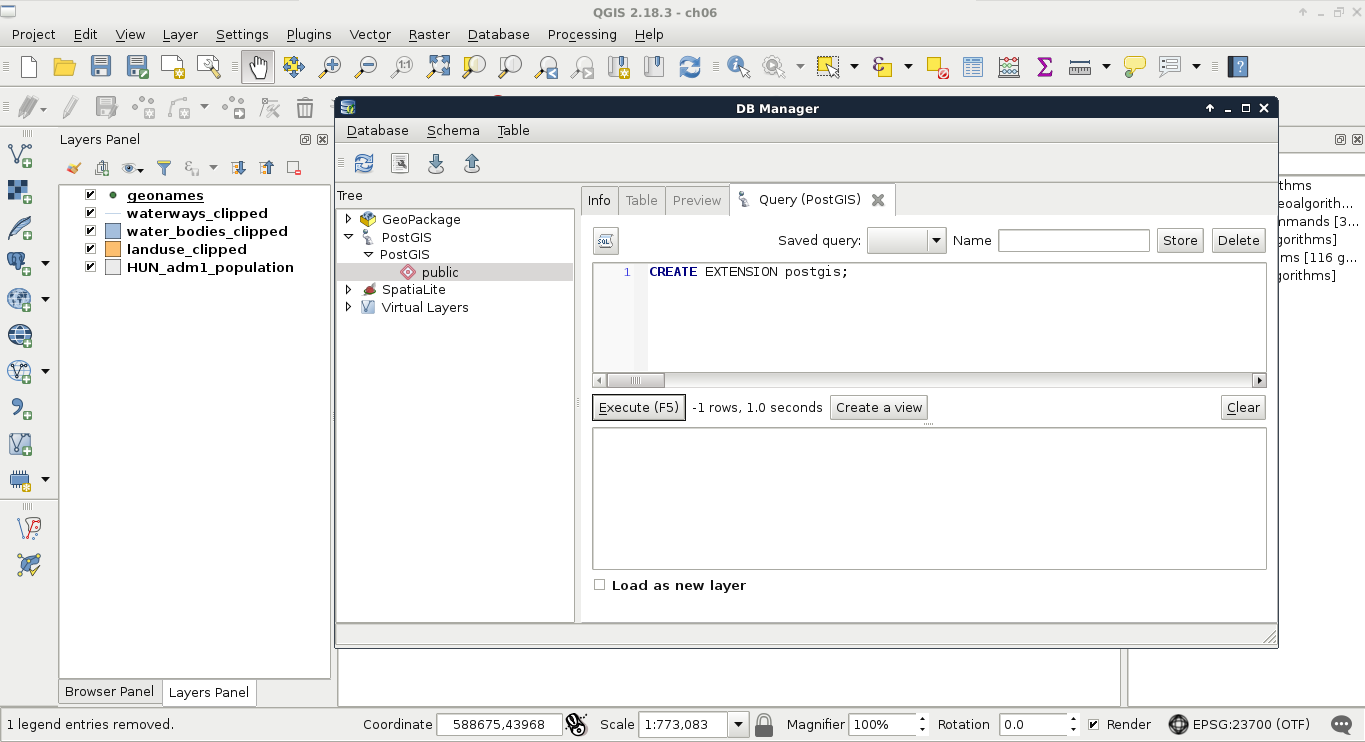

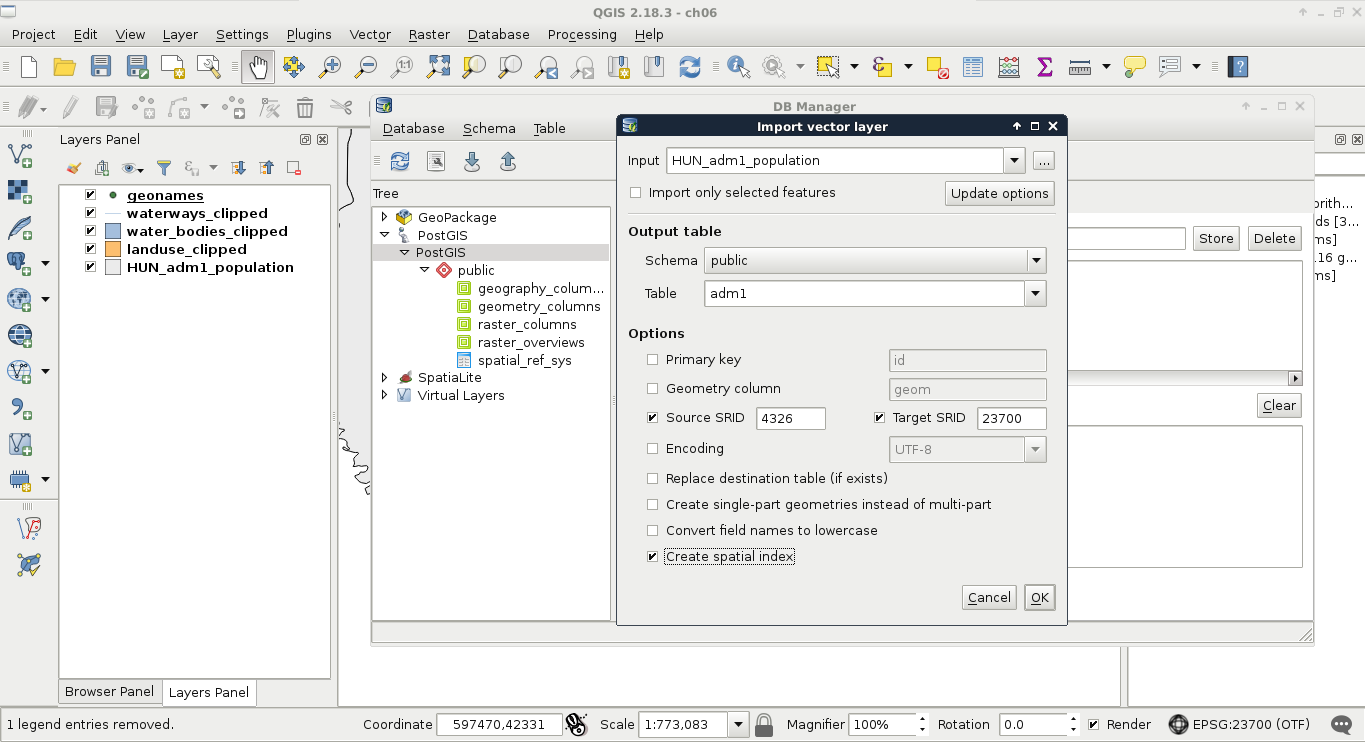

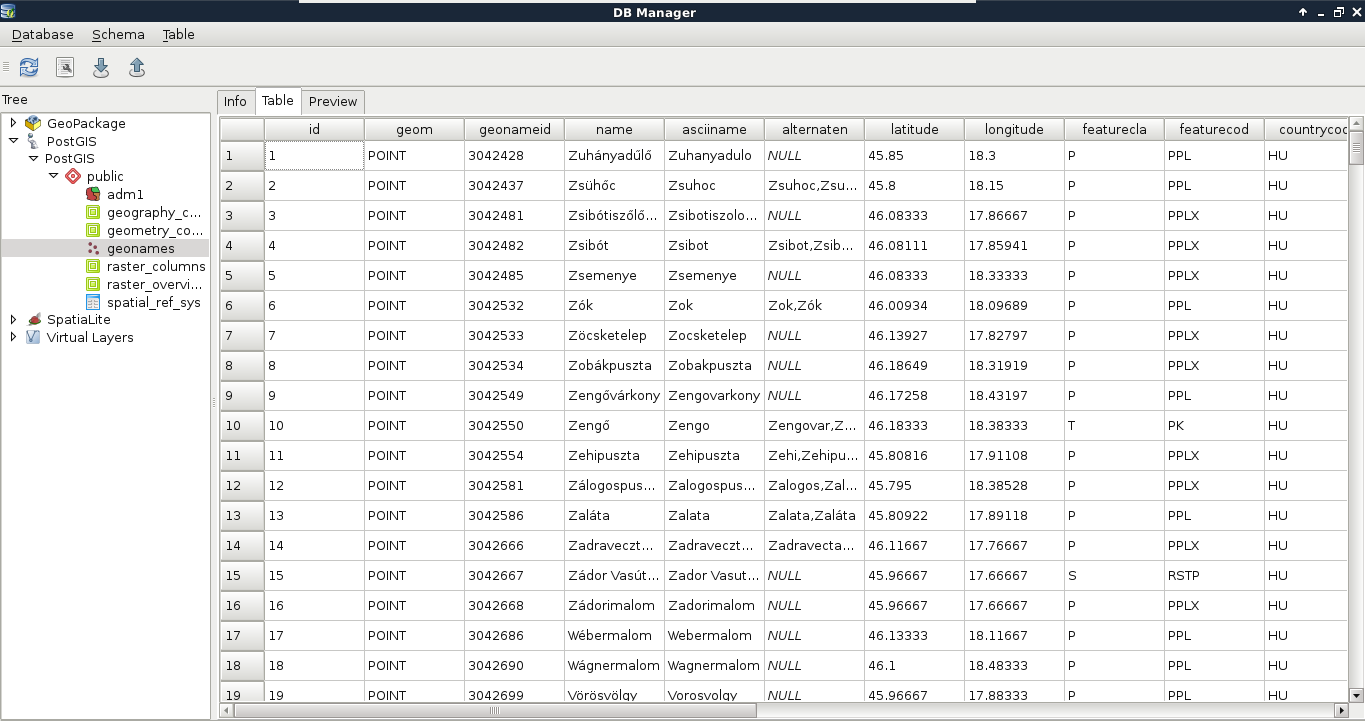

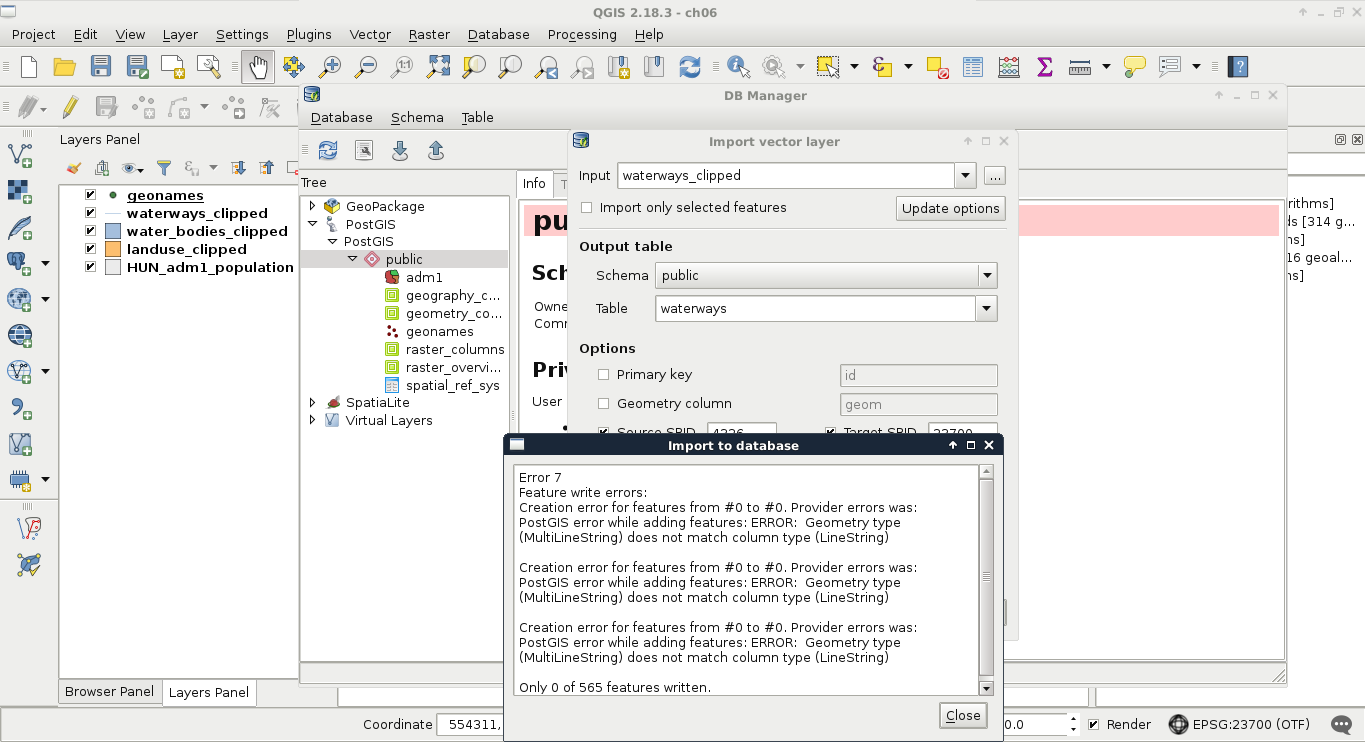

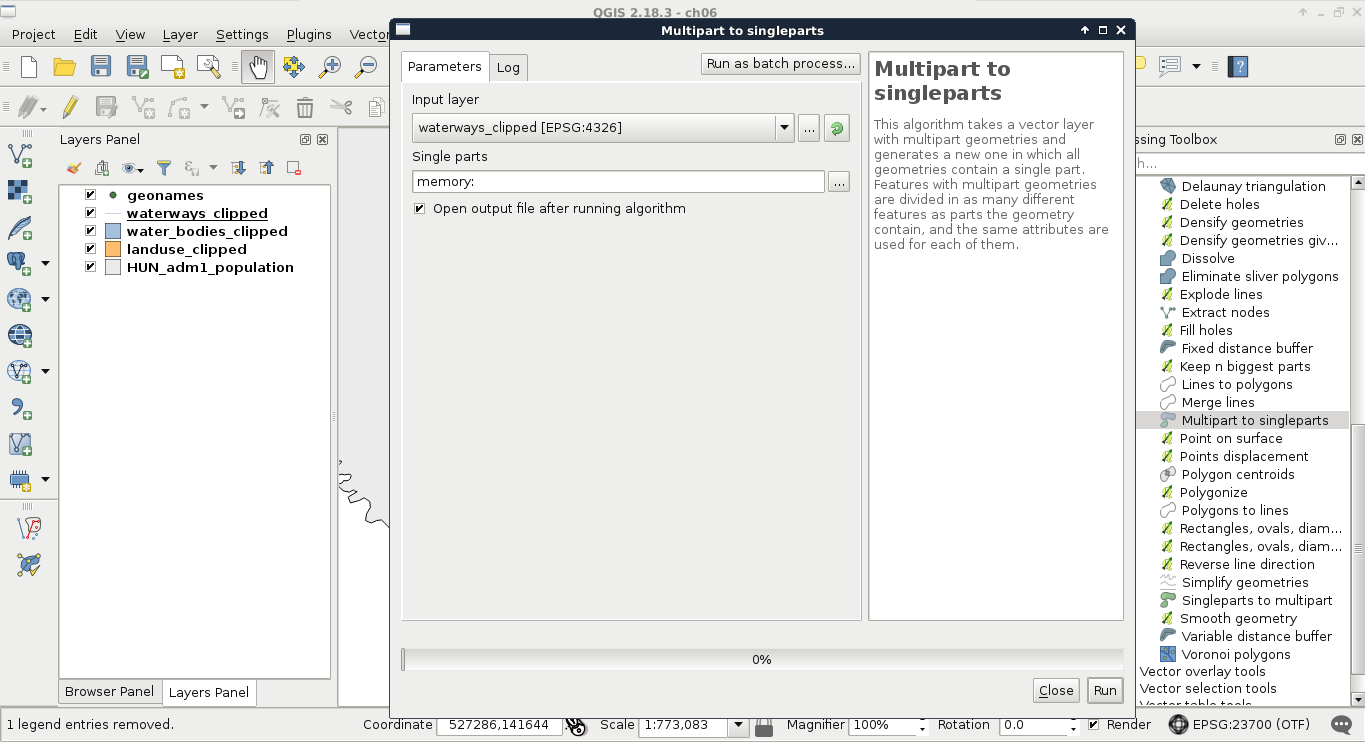

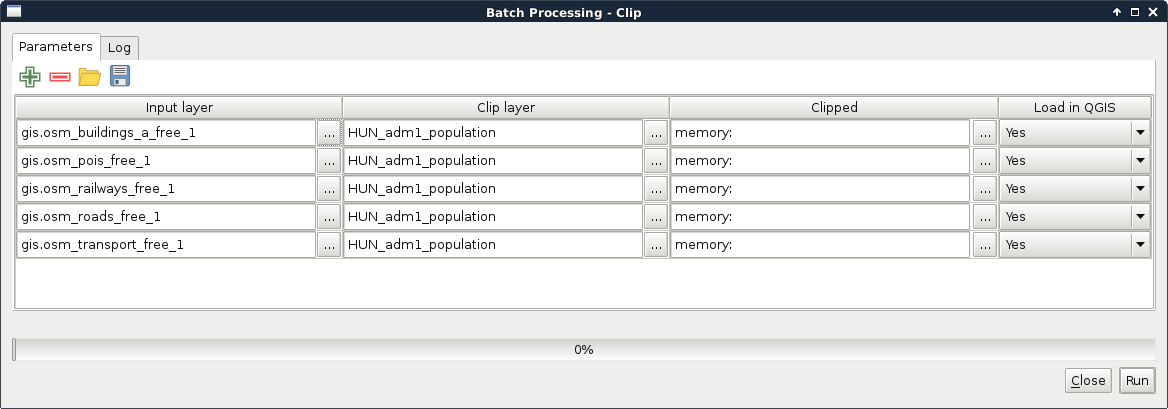

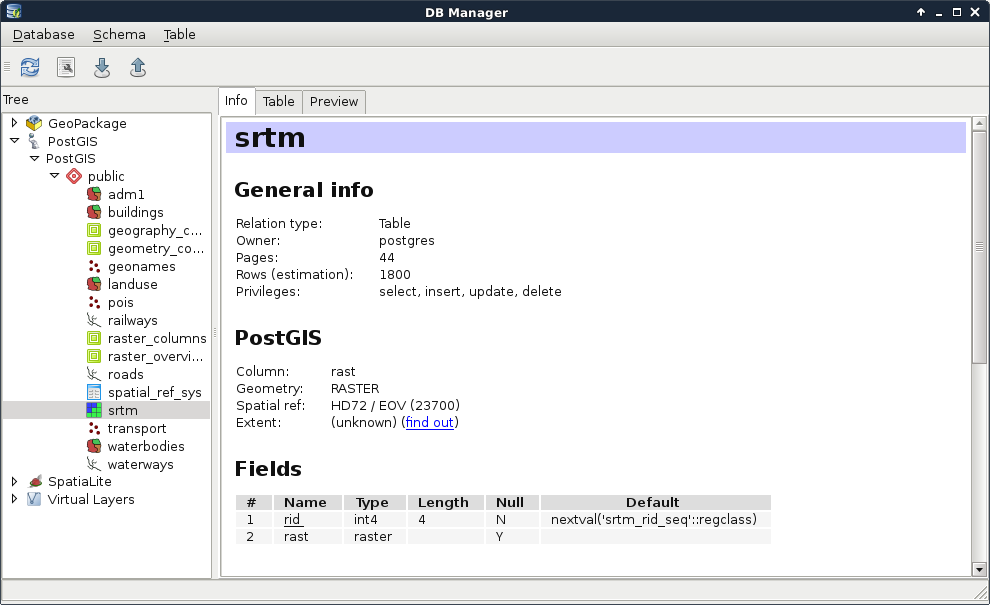

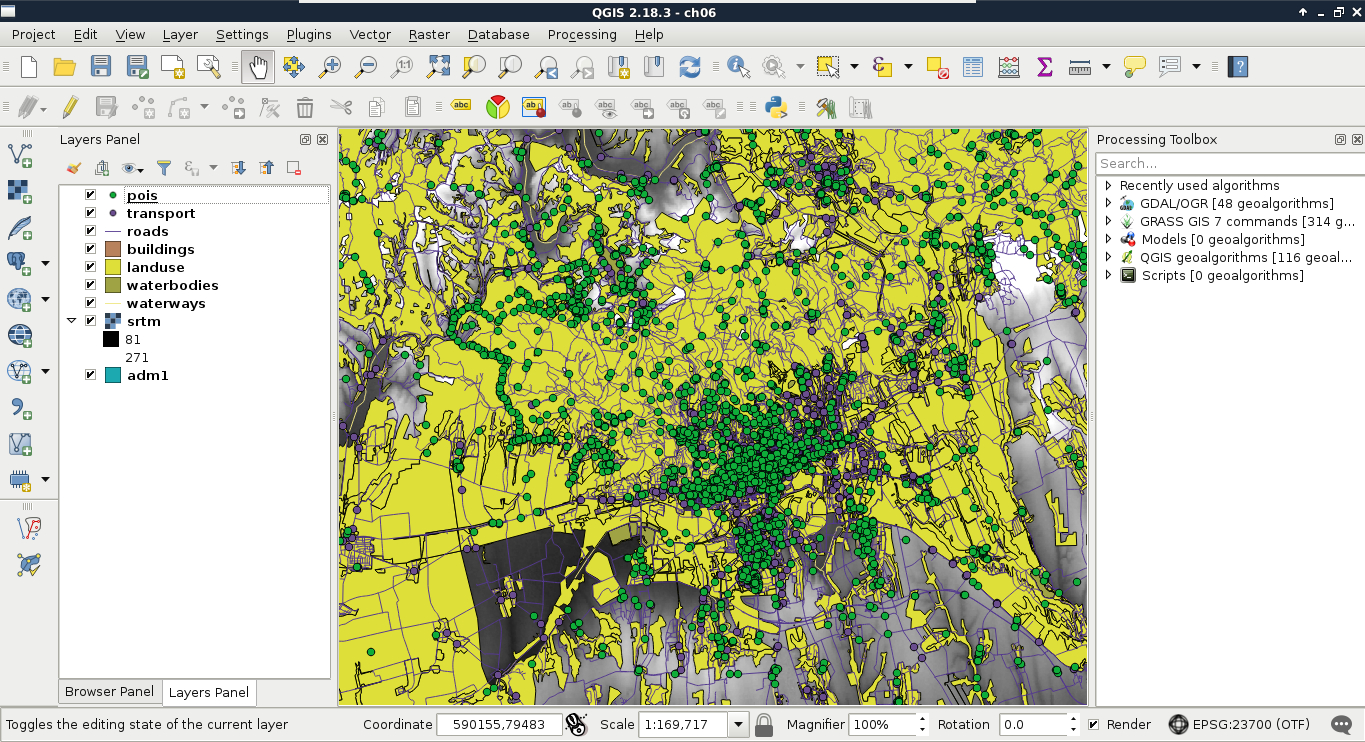

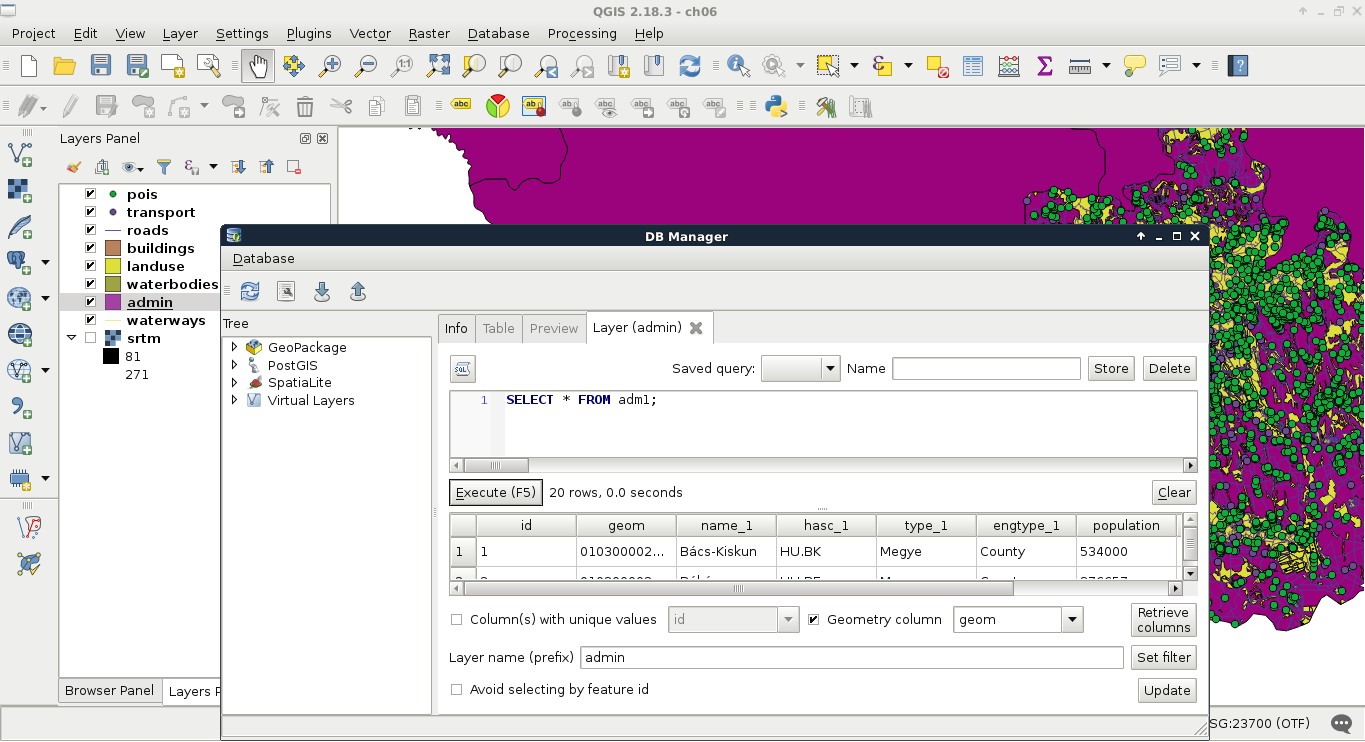

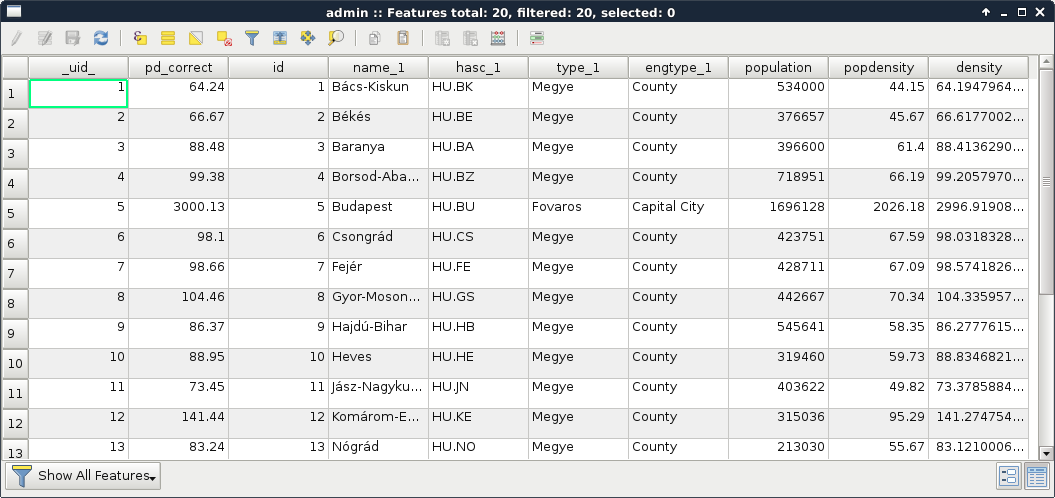

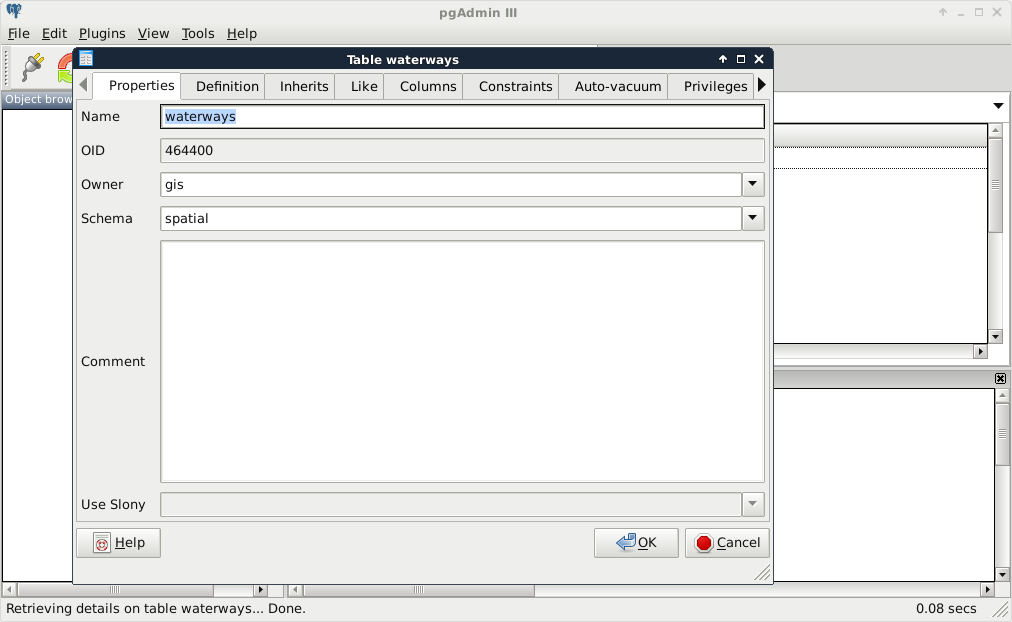

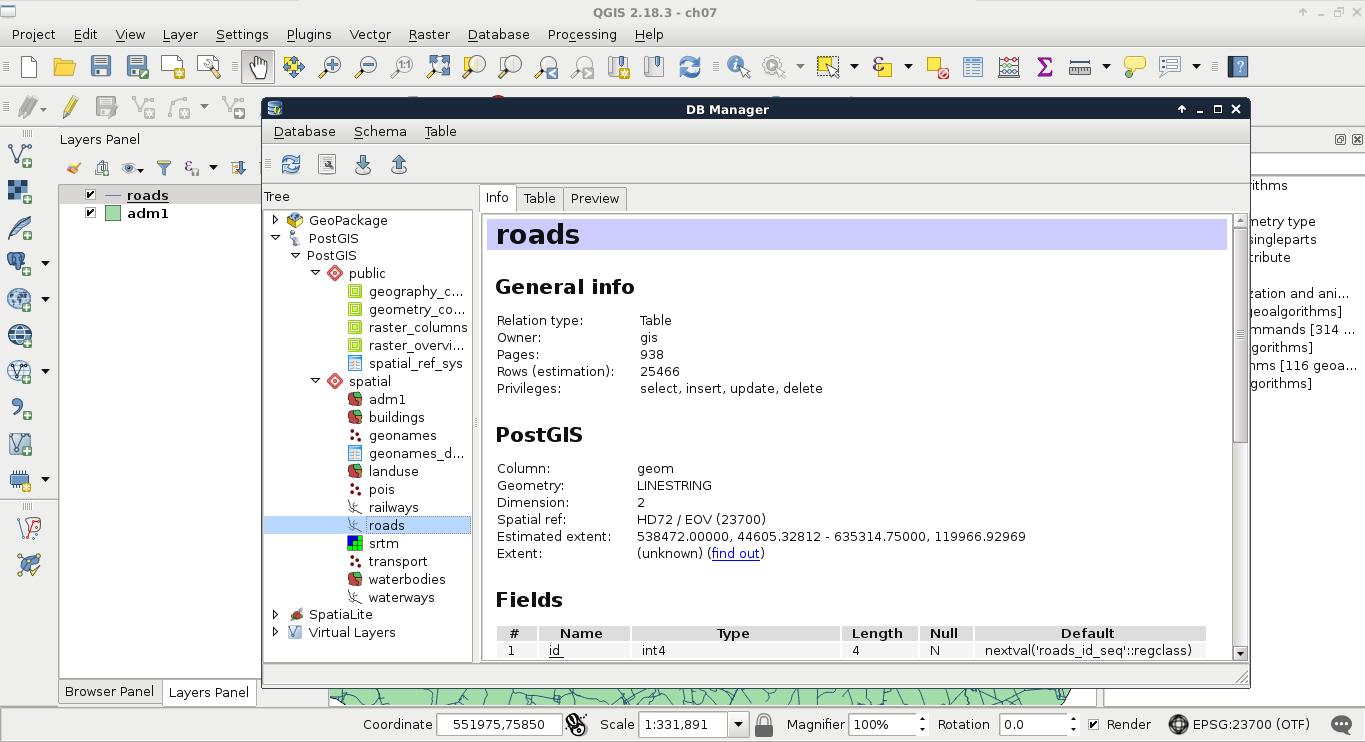

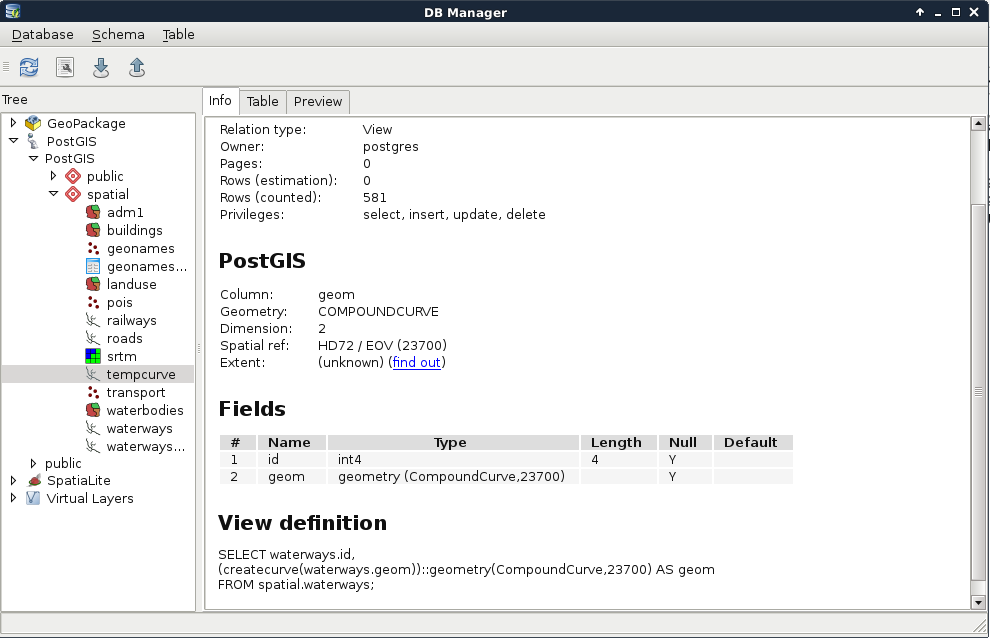

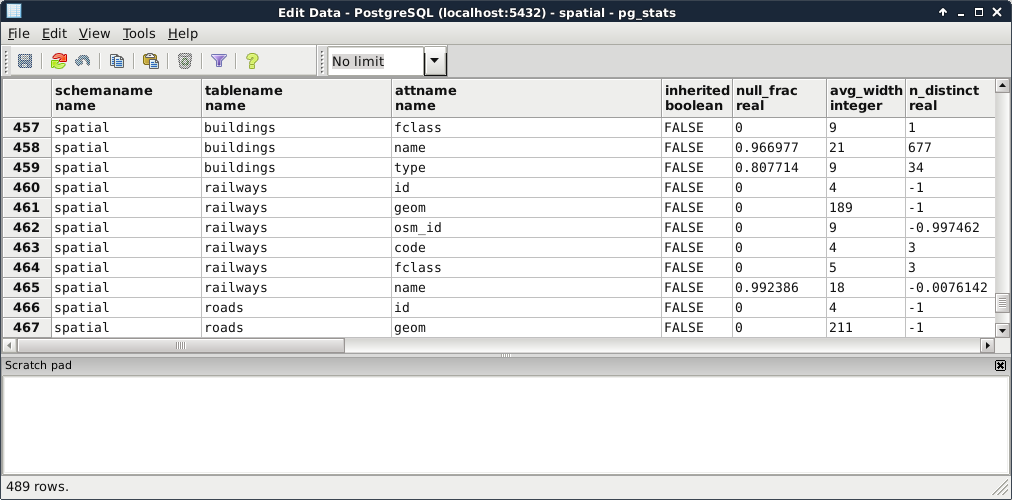

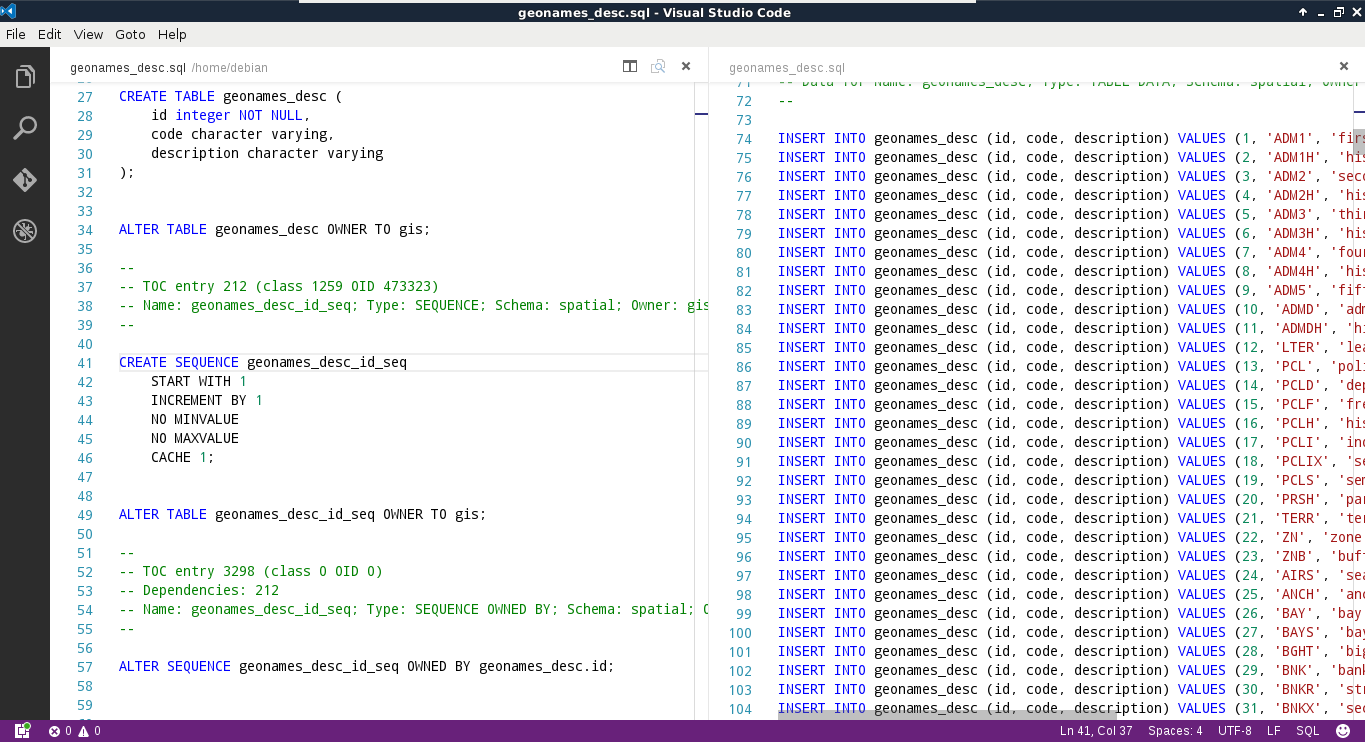

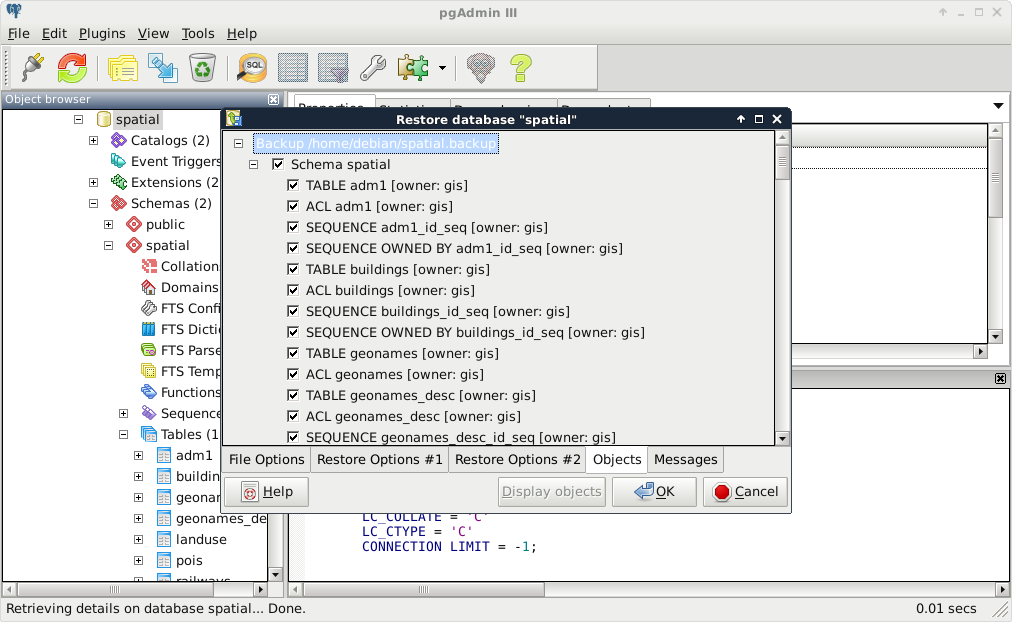

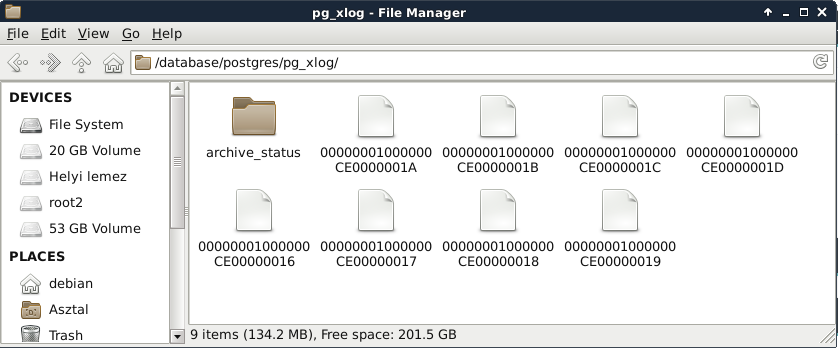

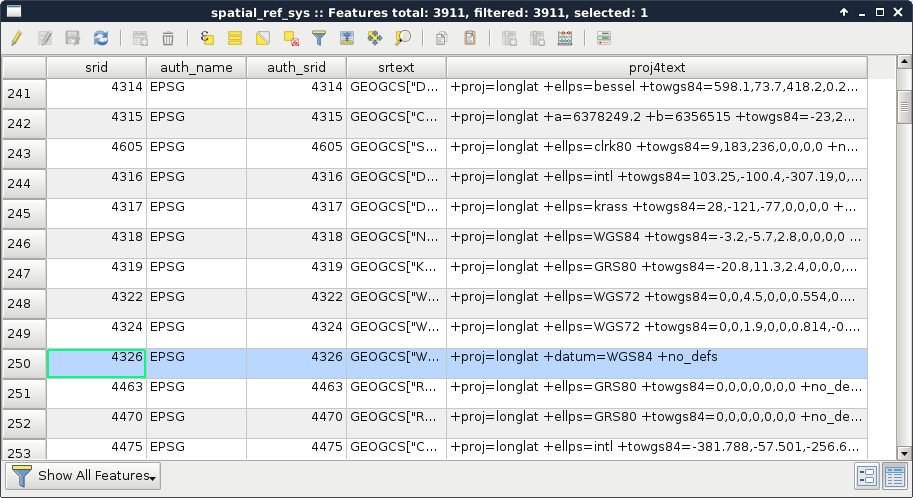

Chapter 6, Feeding a PostGIS Database, guides you through the process of making a spatial database with PostGIS. It discusses how to create a new database, and how to fill it with various kinds of spatial data using QGIS. You will also learn how to manage existing PostGIS tables from QGIS.

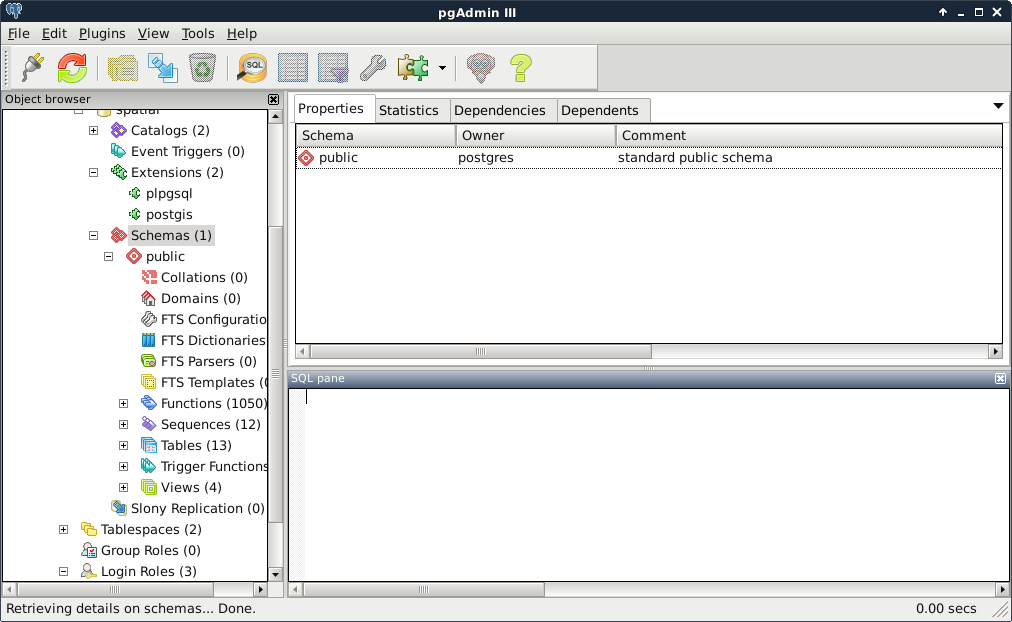

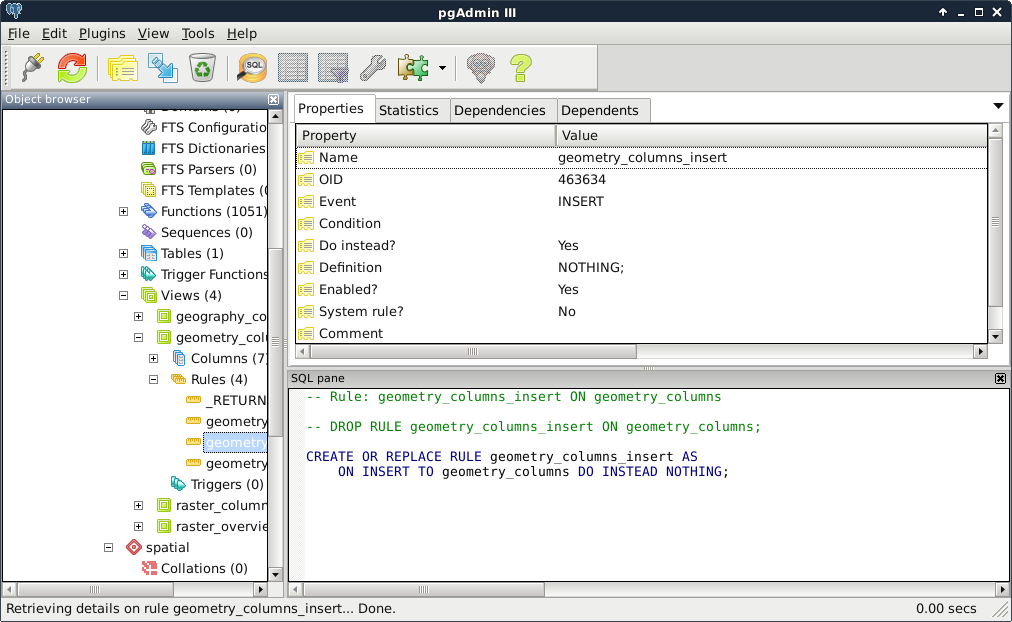

Chapter 7, A PostGIS Overview, shows what other options you have with your PostGIS database. It leaves QGIS and talks about important PostgreSQL and PostGIS concepts by managing the database created in the previous chapter through PostgreSQL's administration software, pgAdmin.

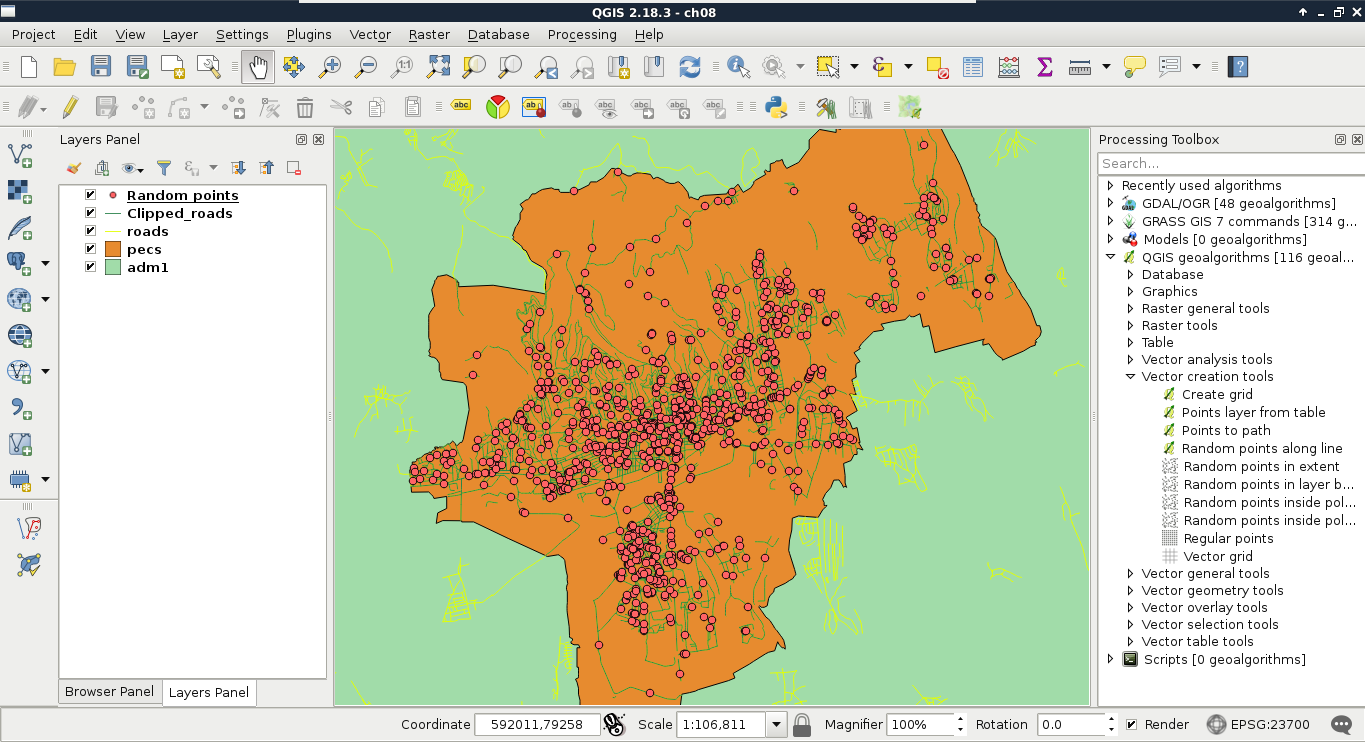

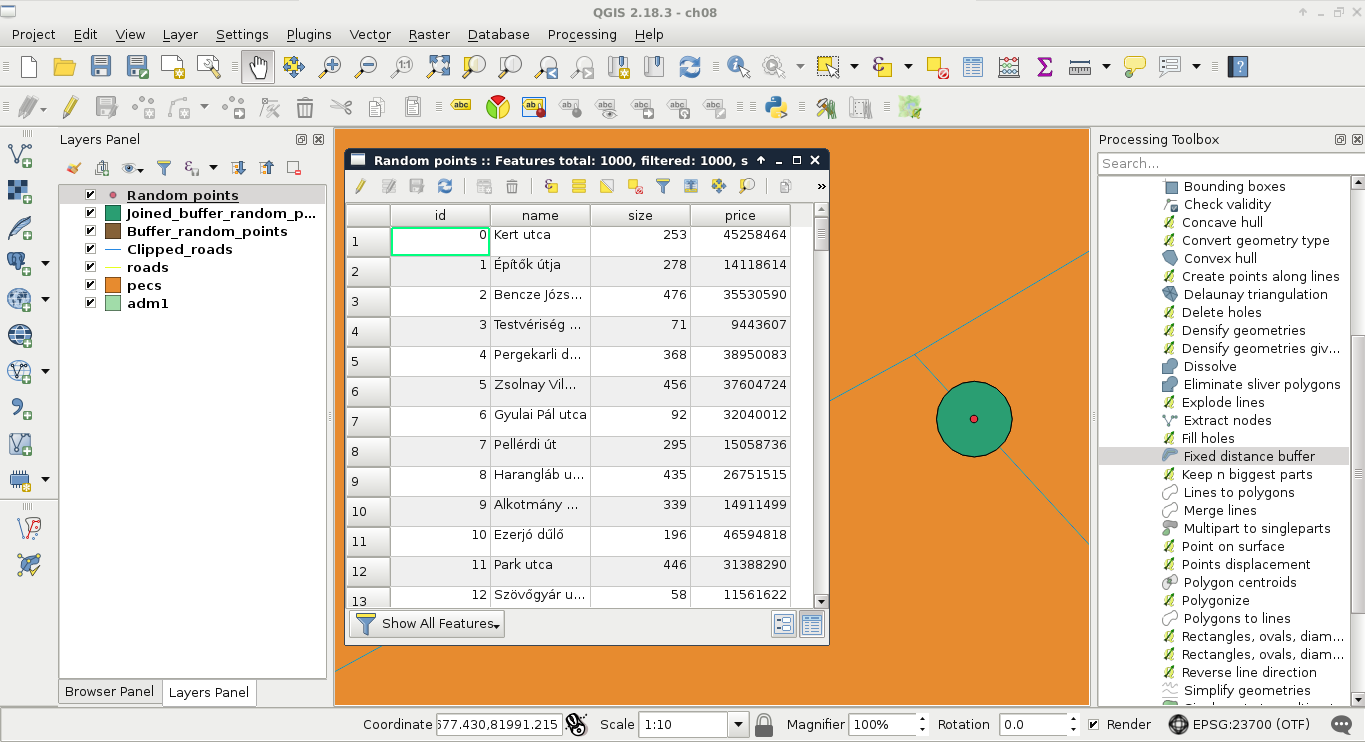

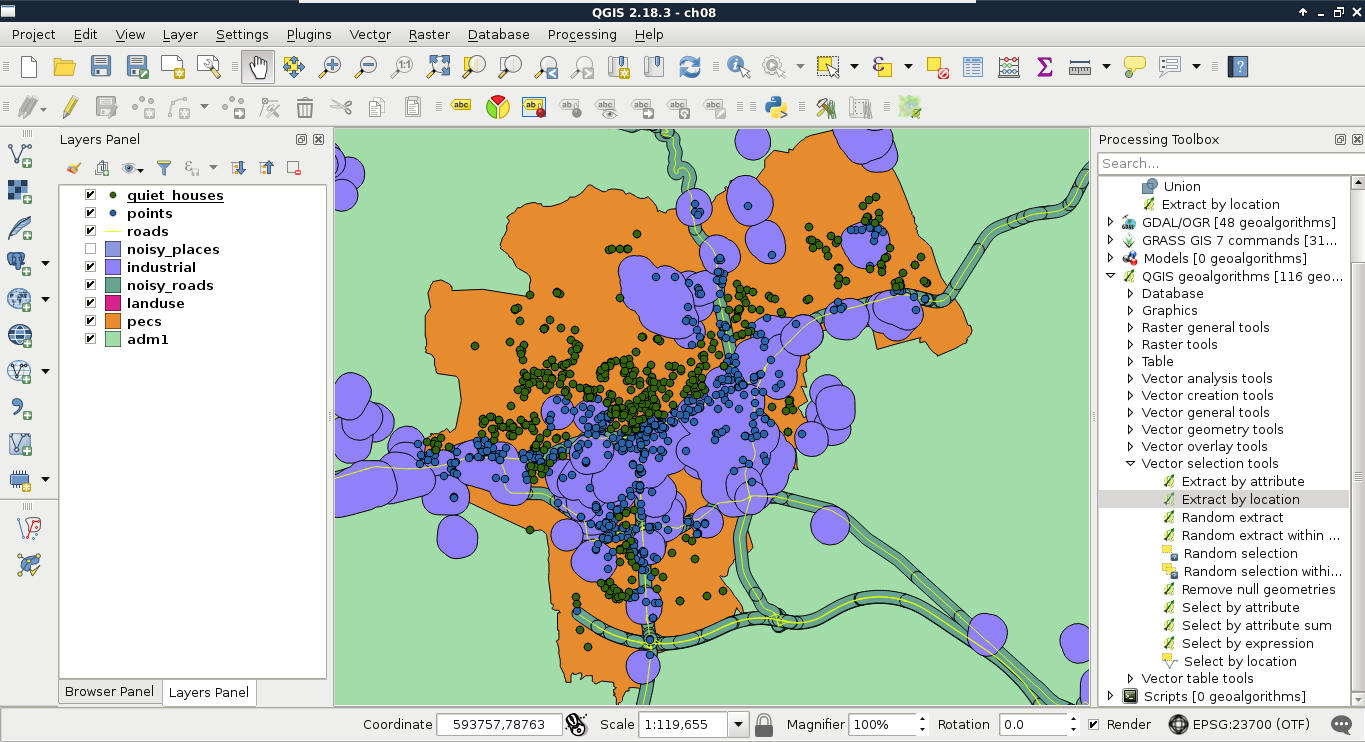

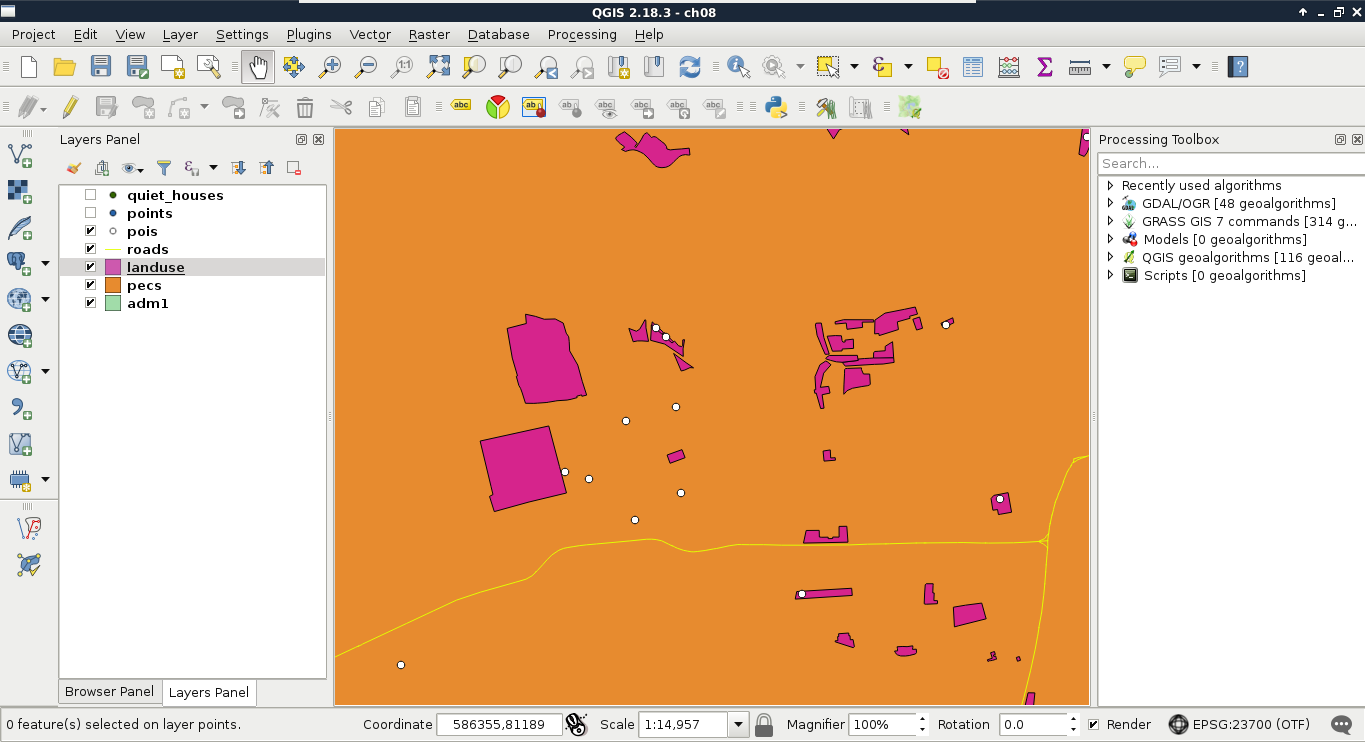

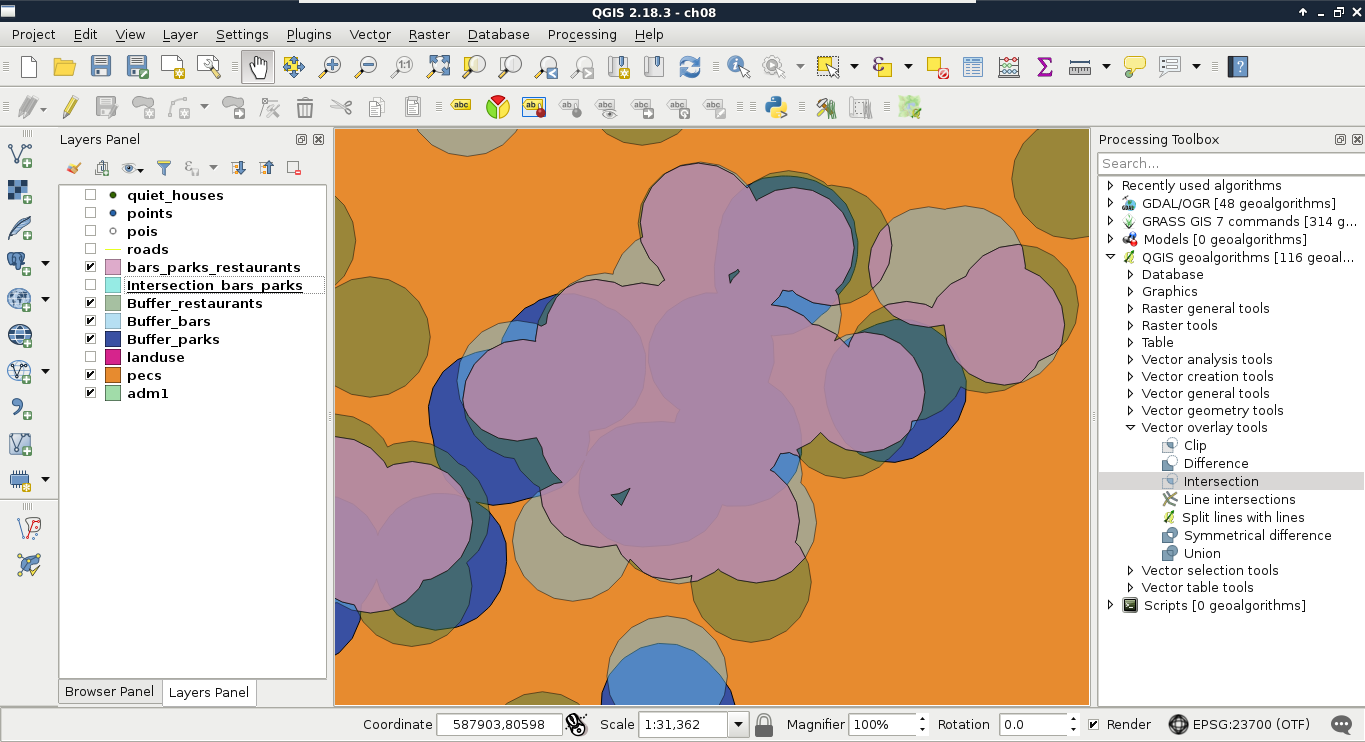

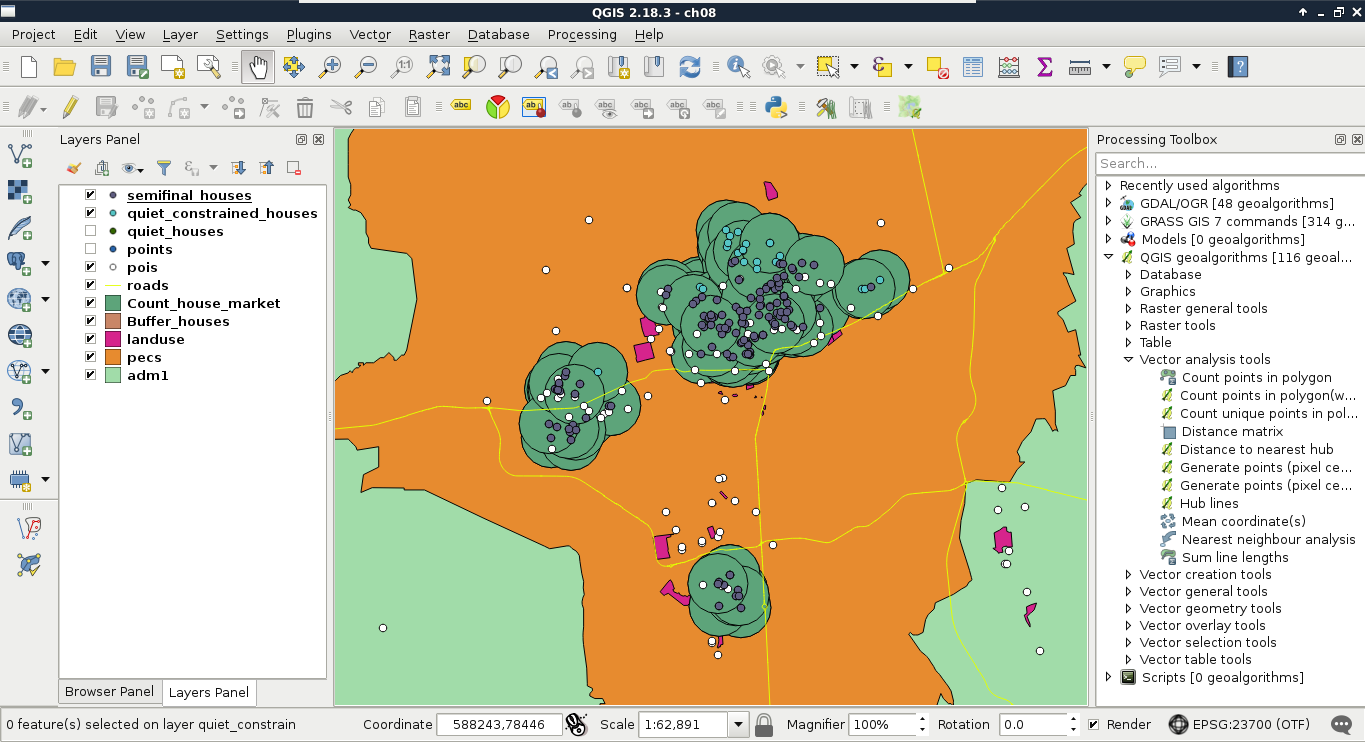

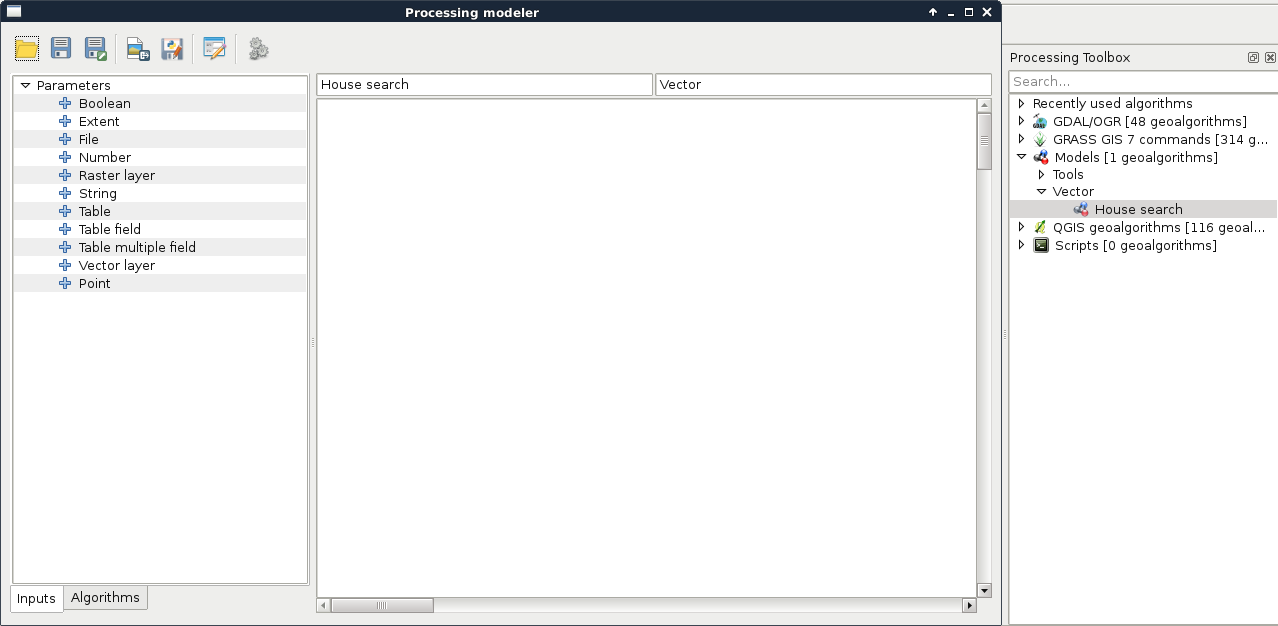

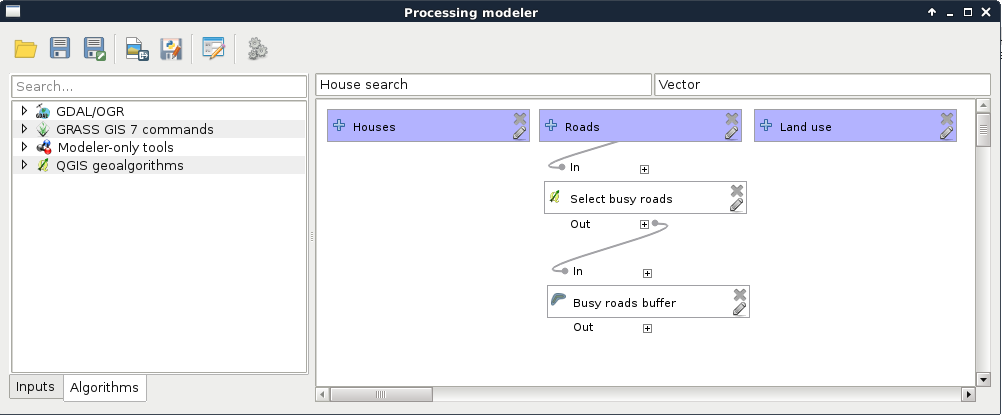

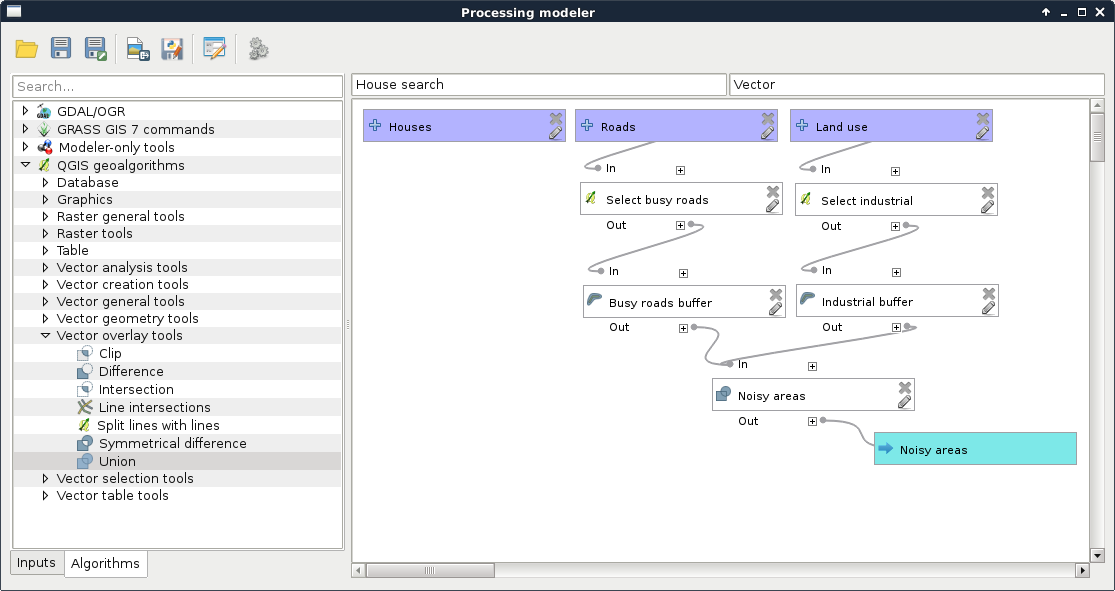

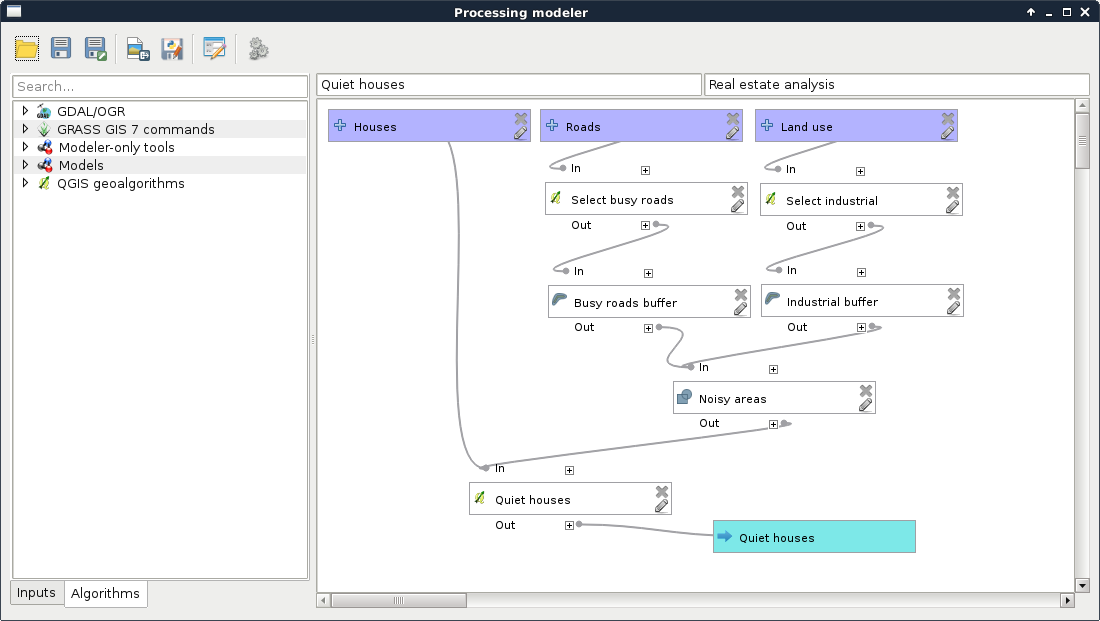

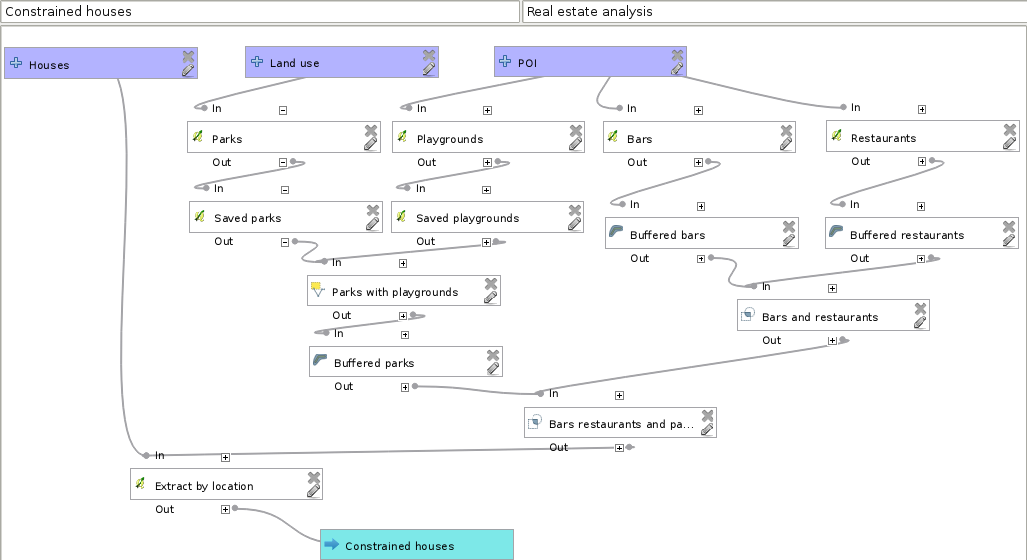

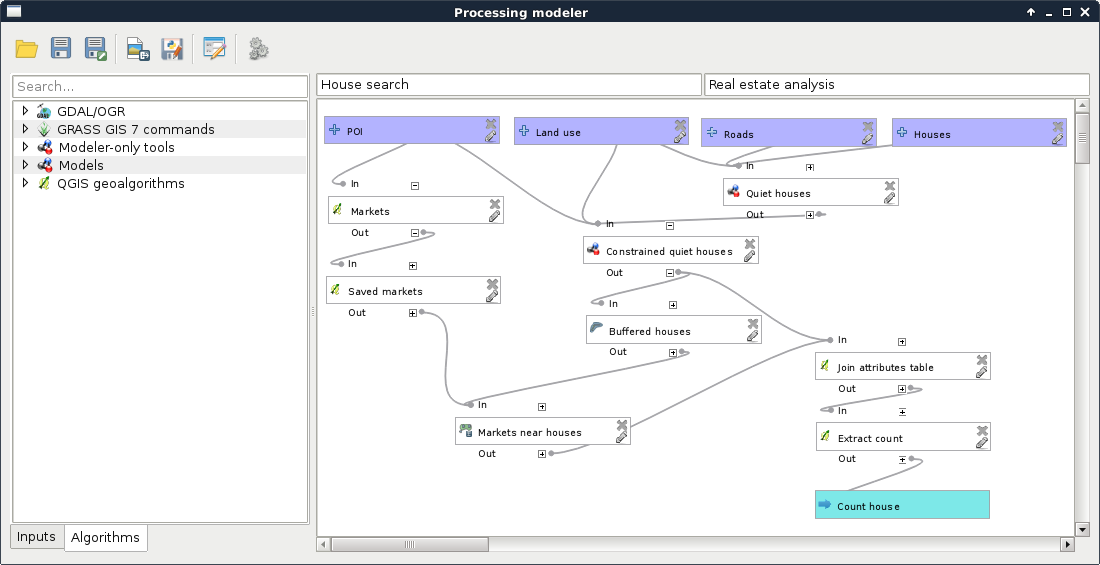

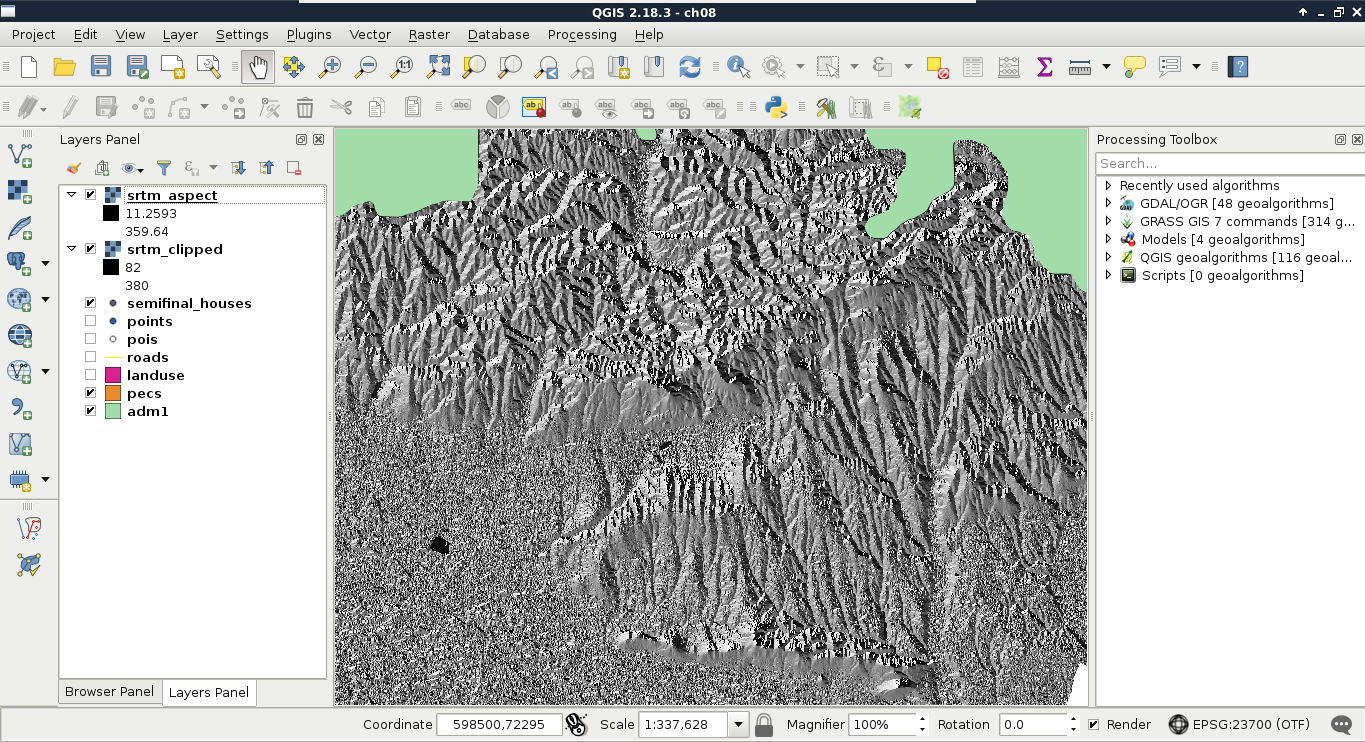

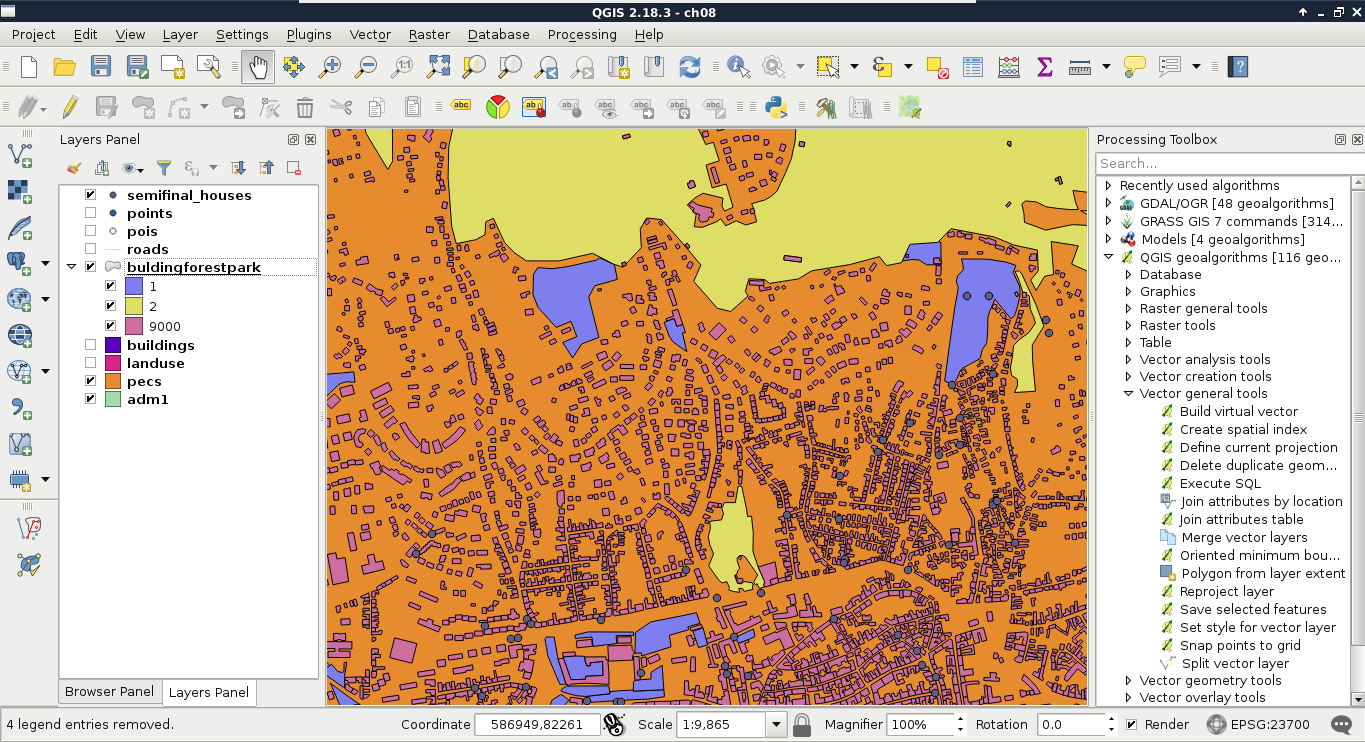

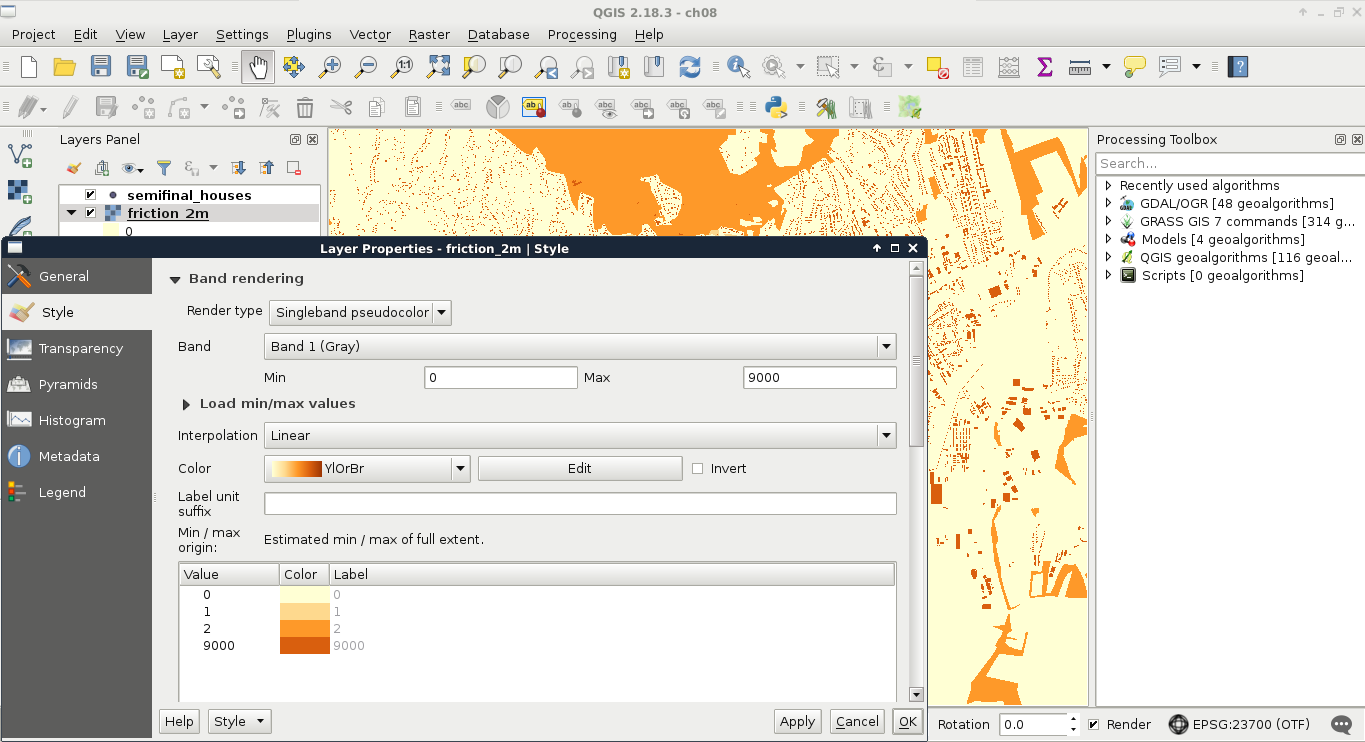

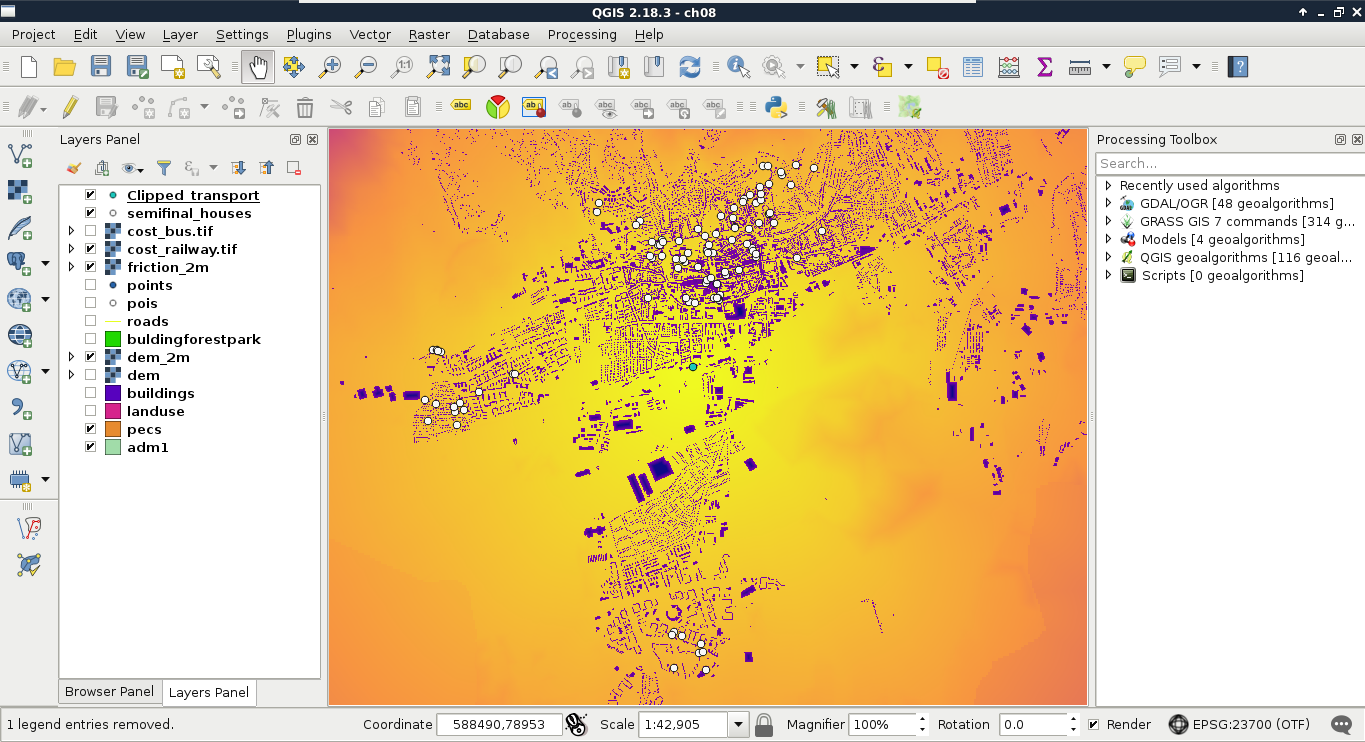

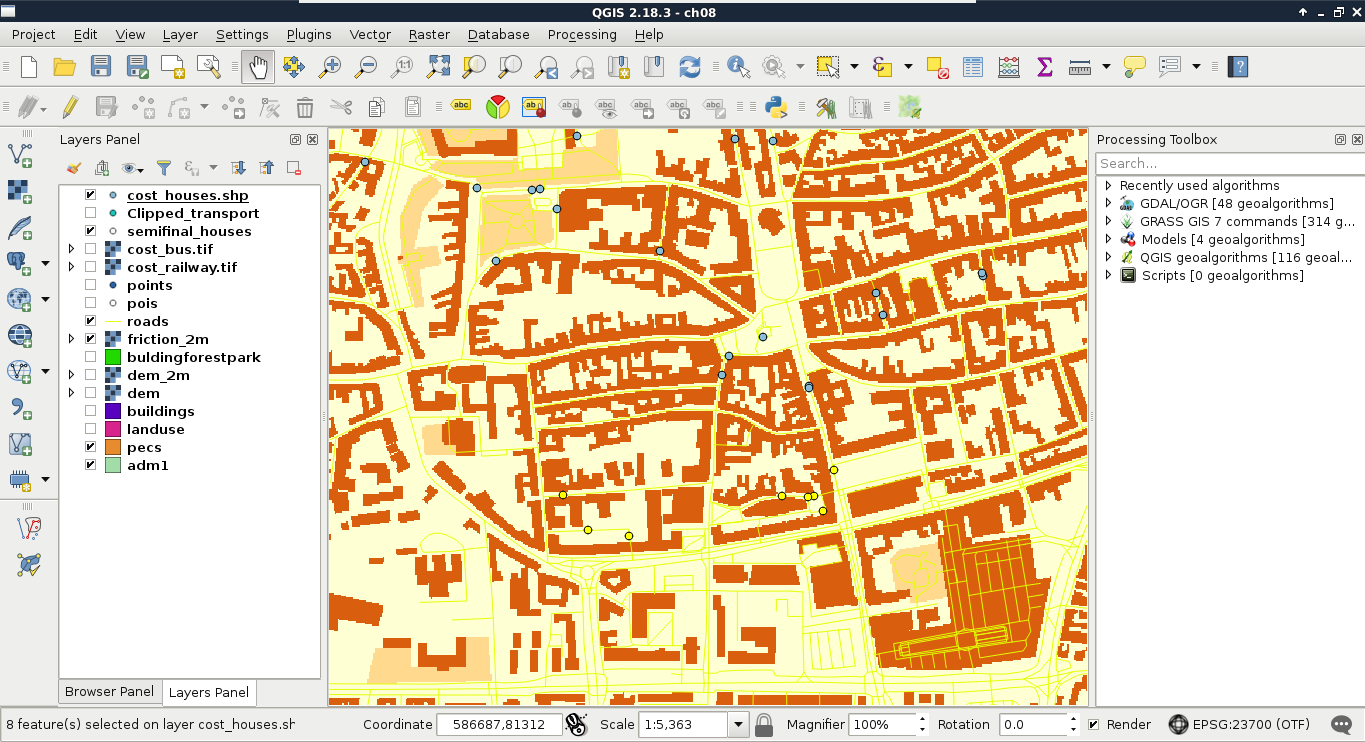

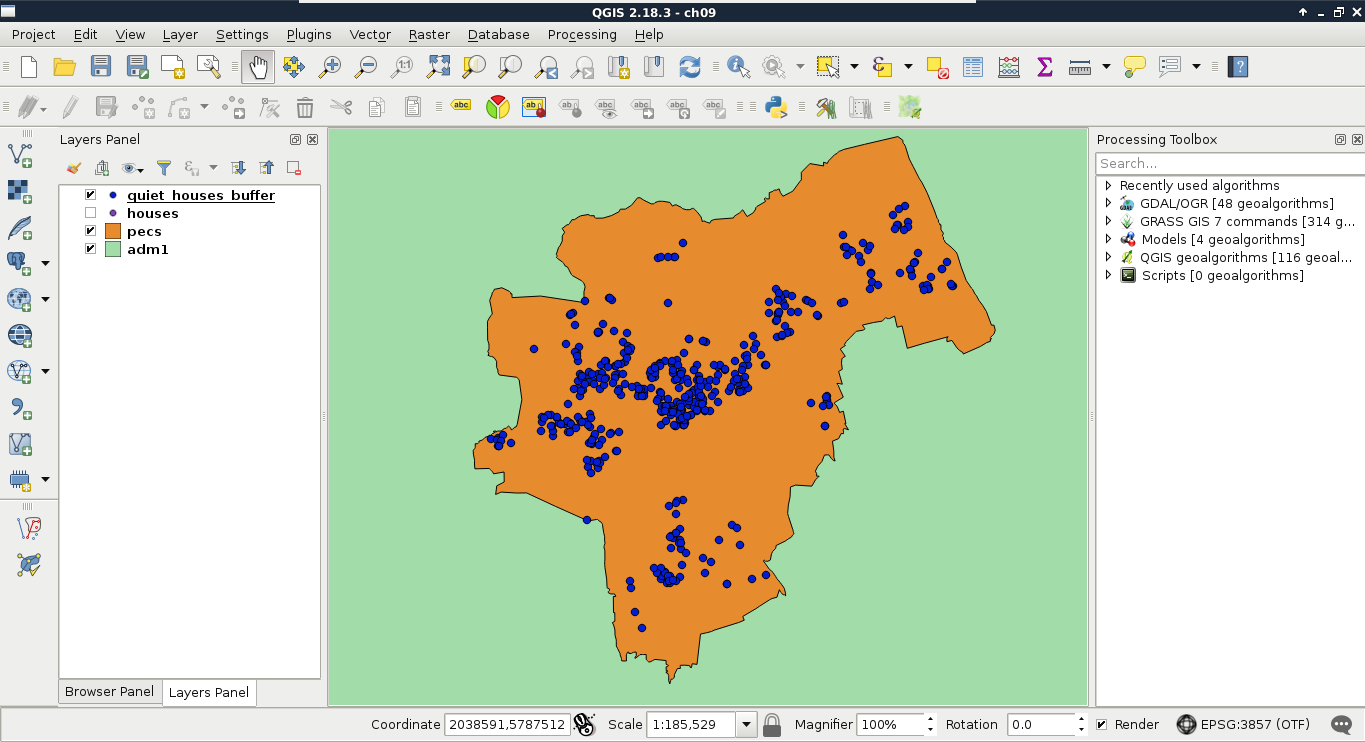

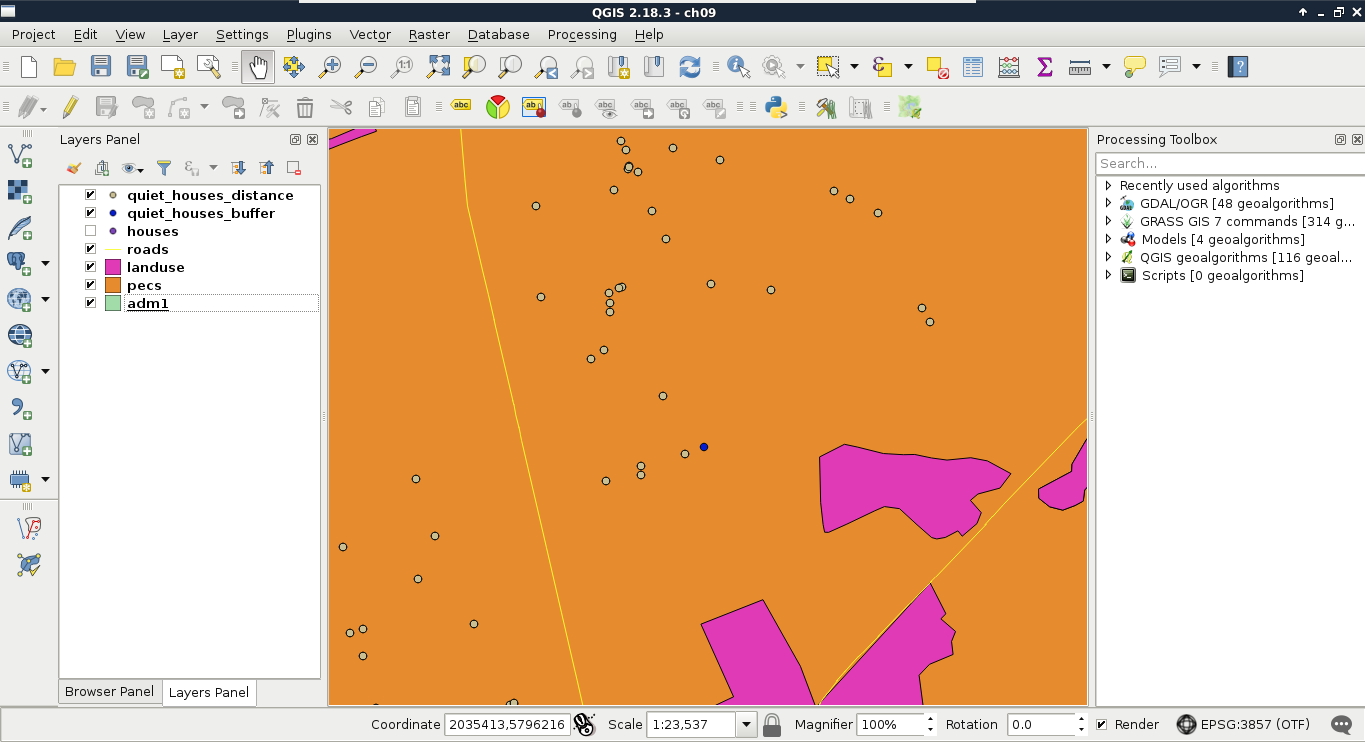

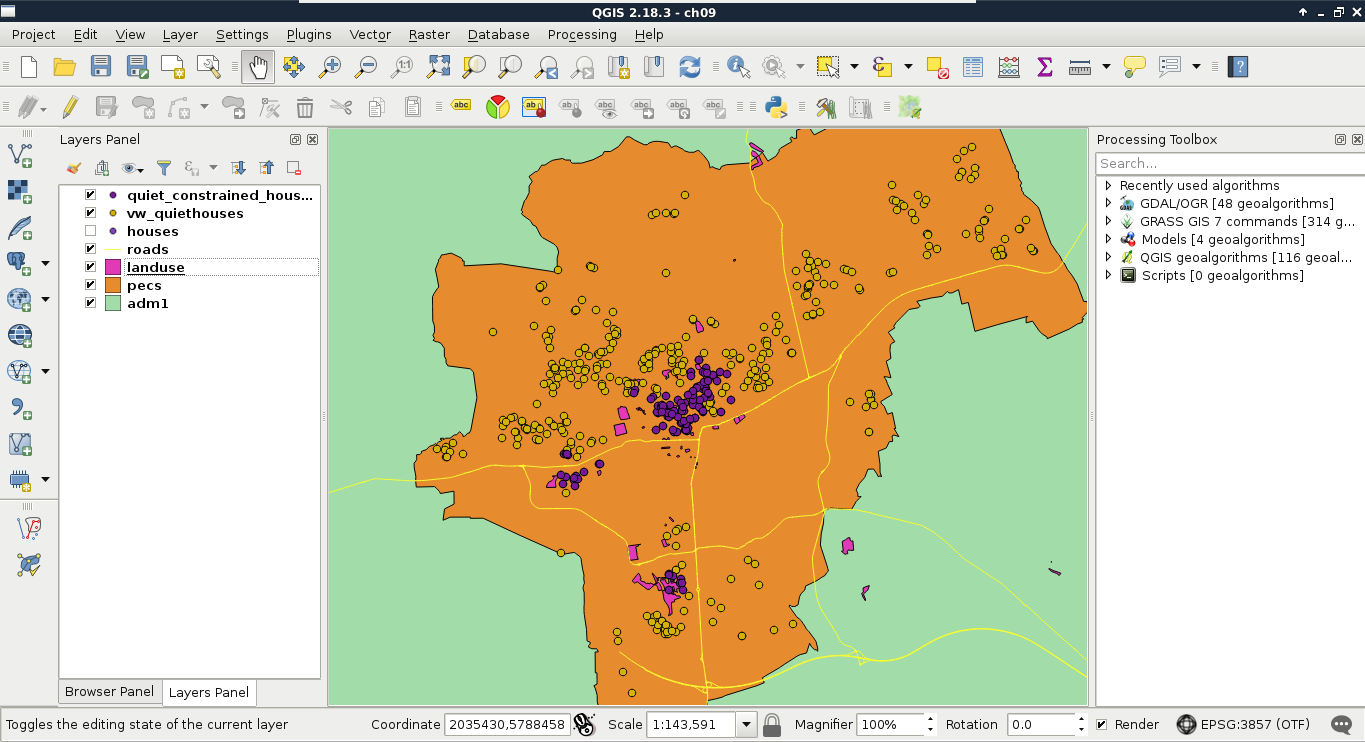

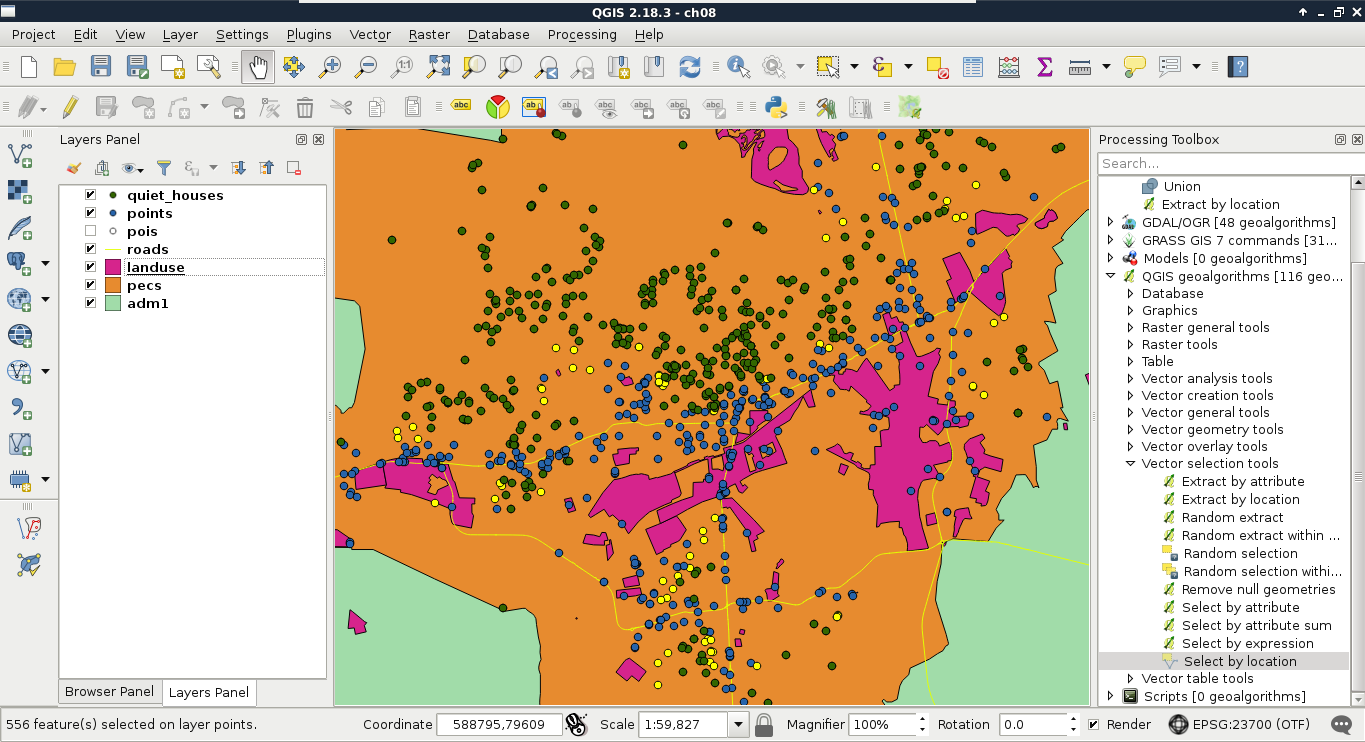

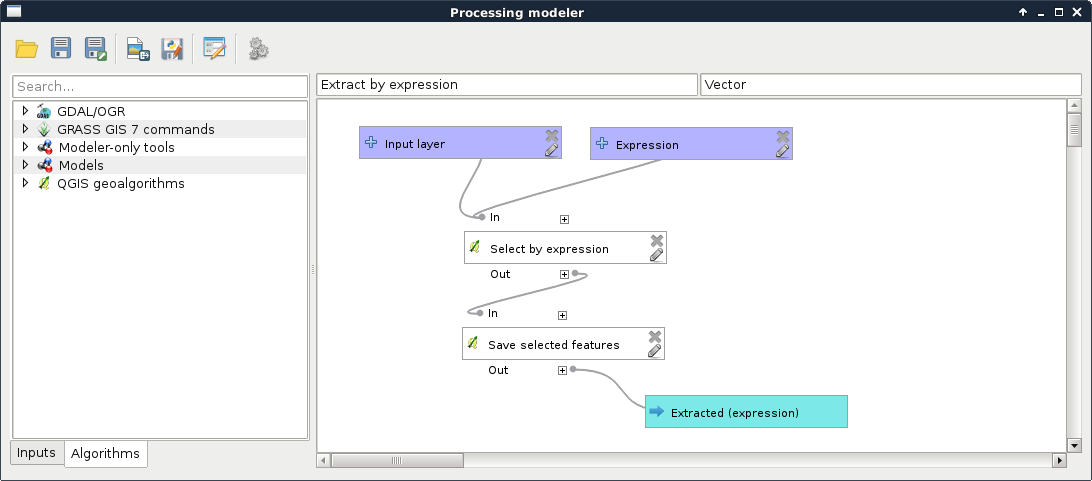

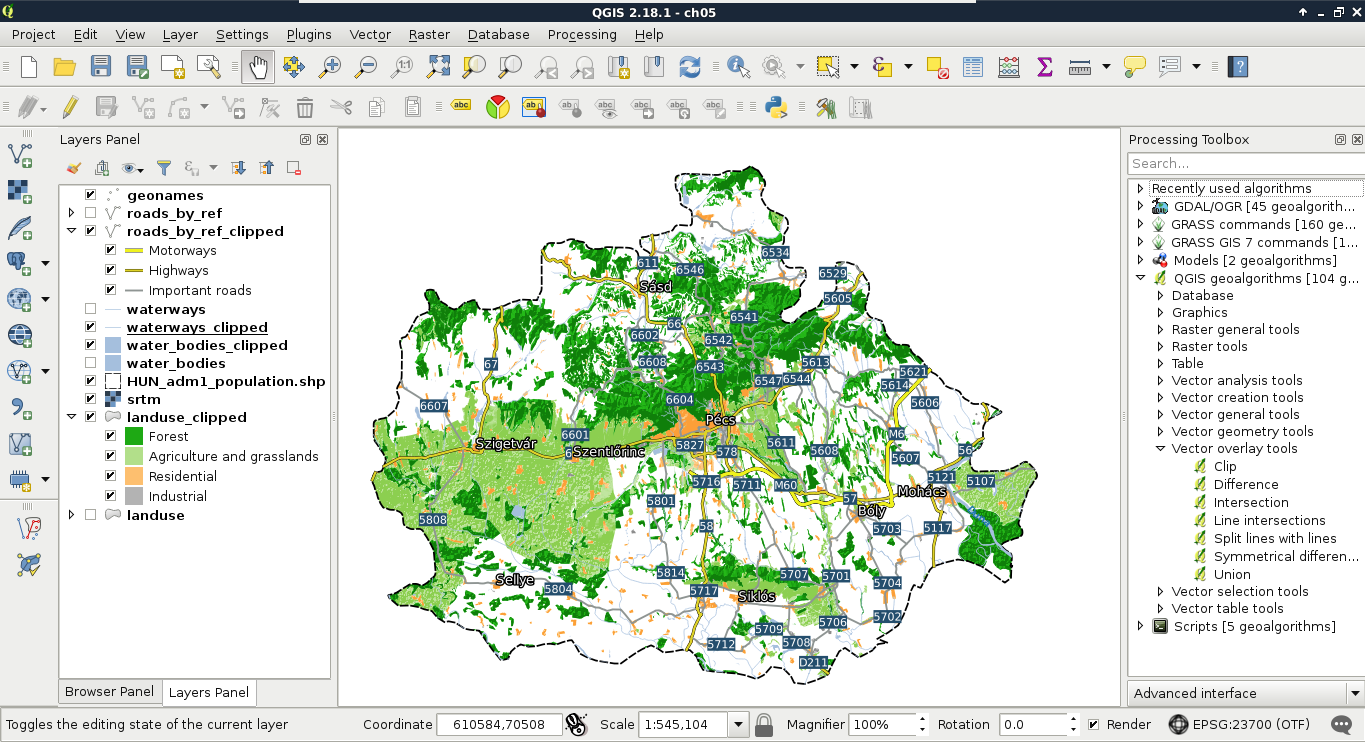

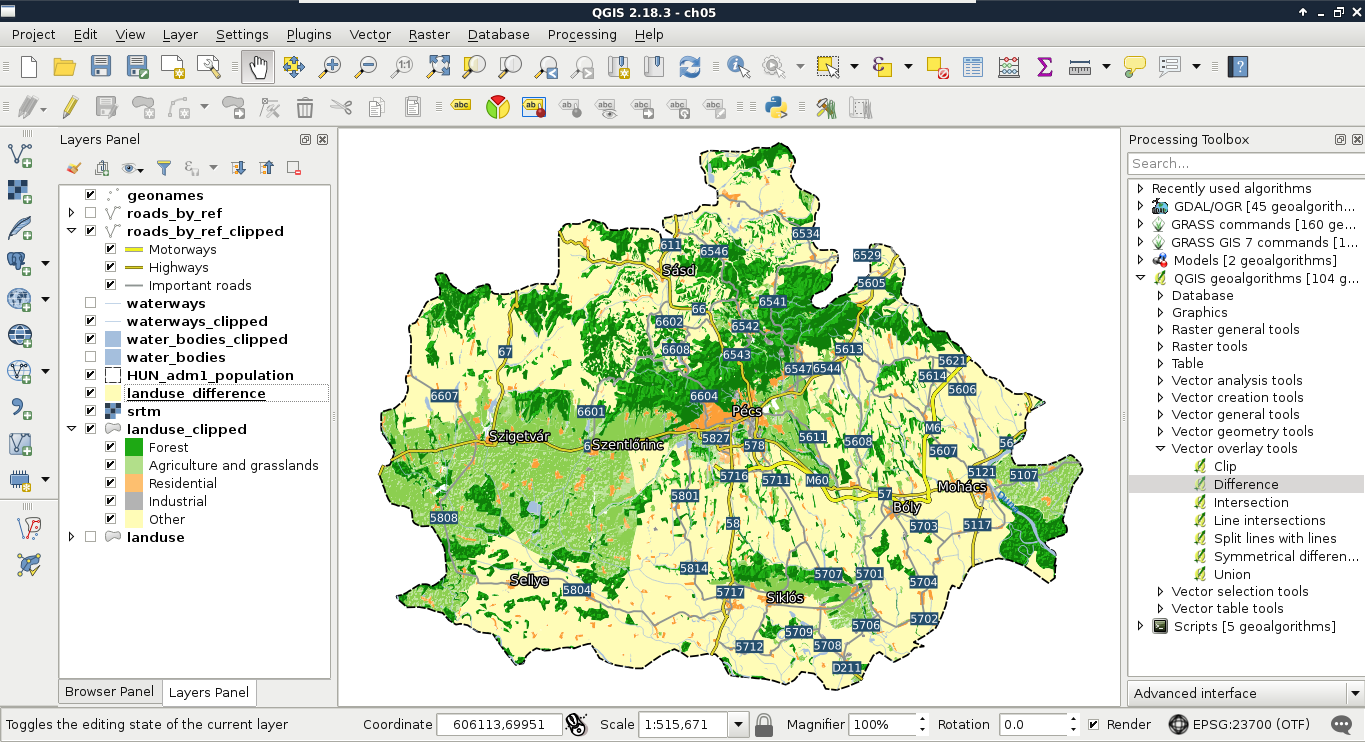

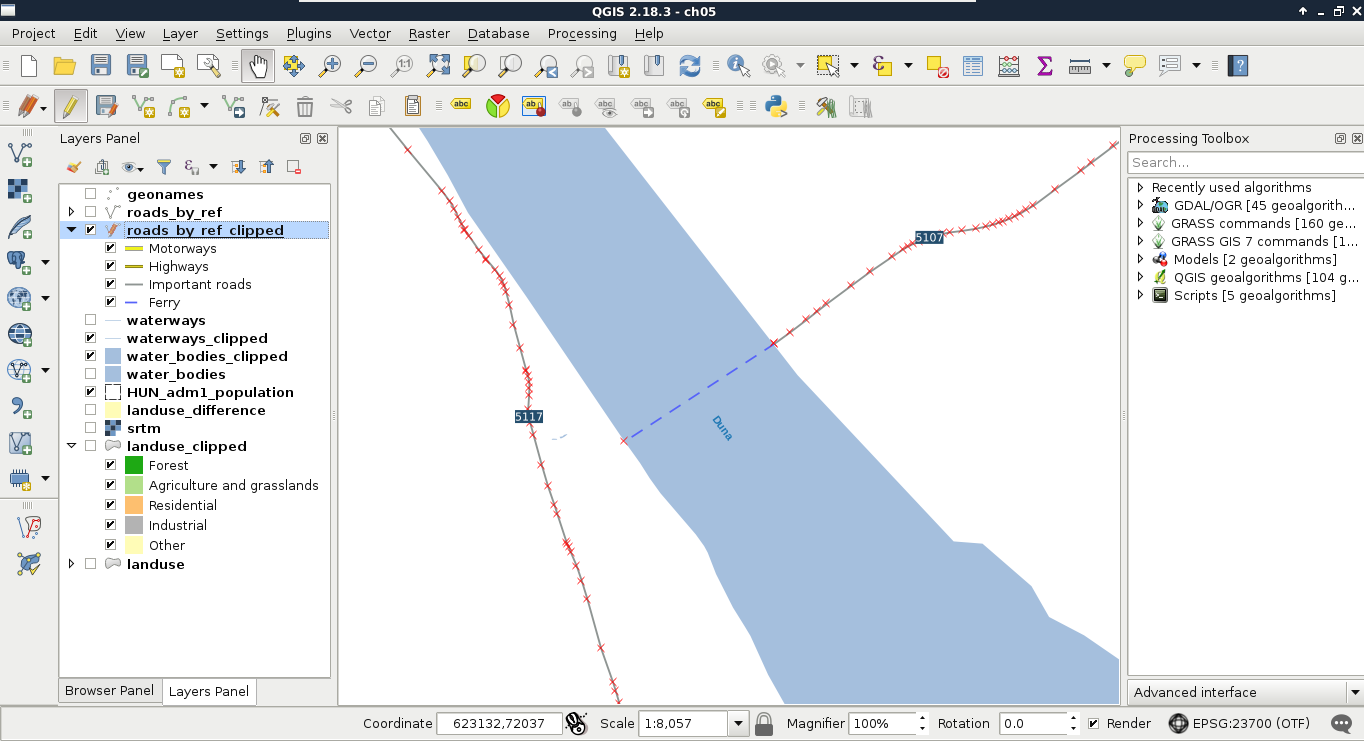

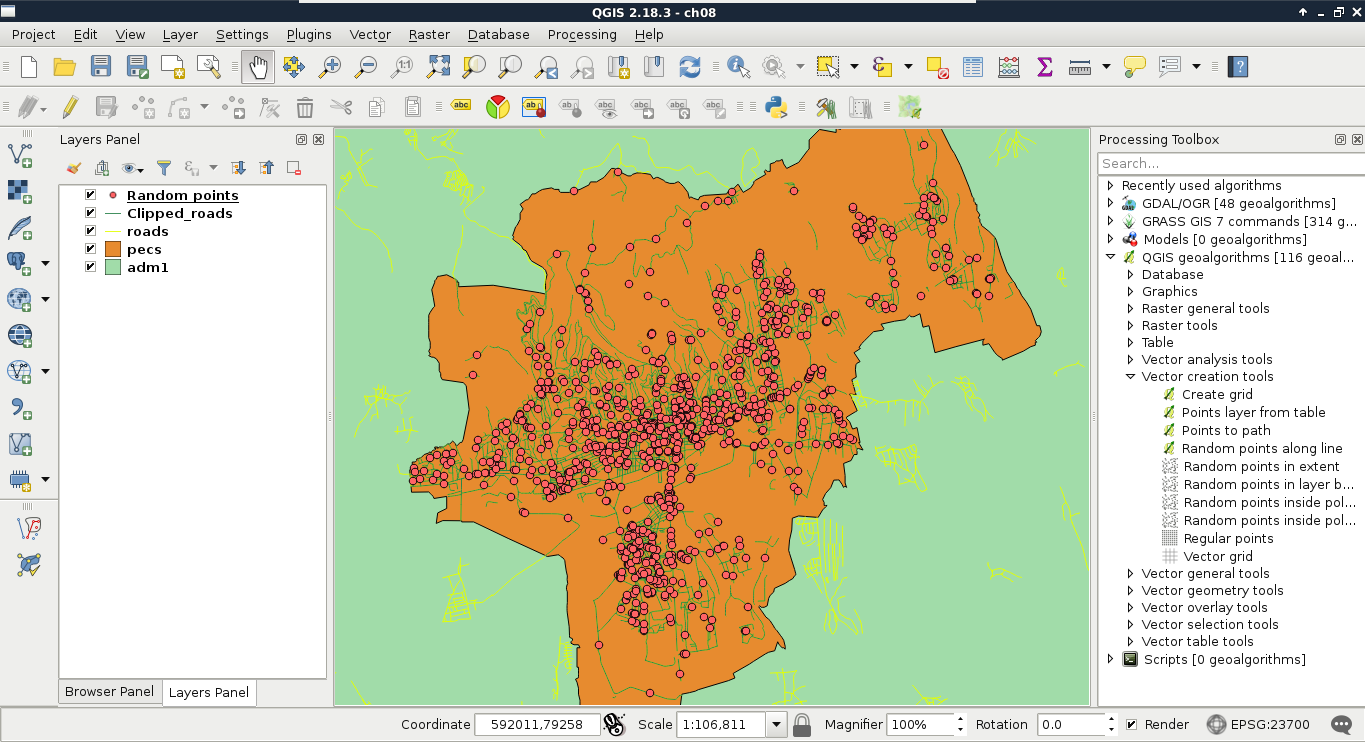

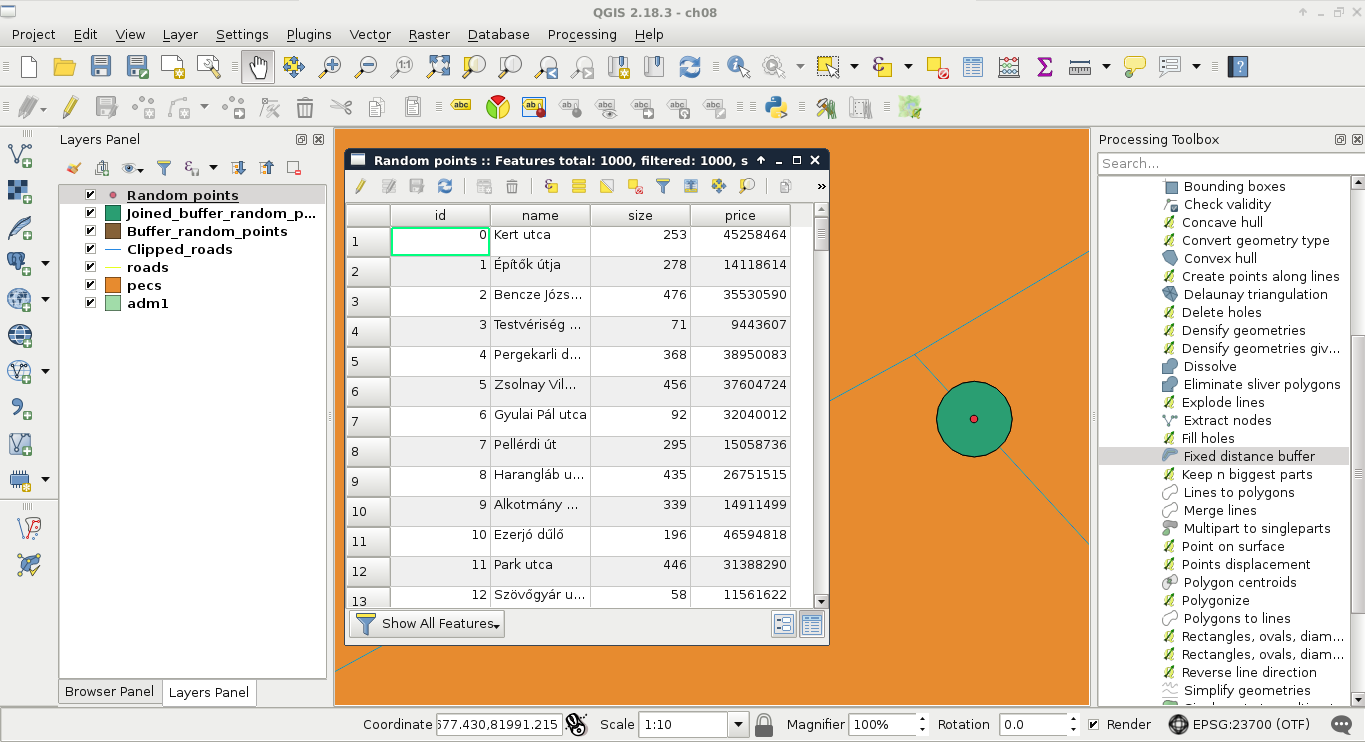

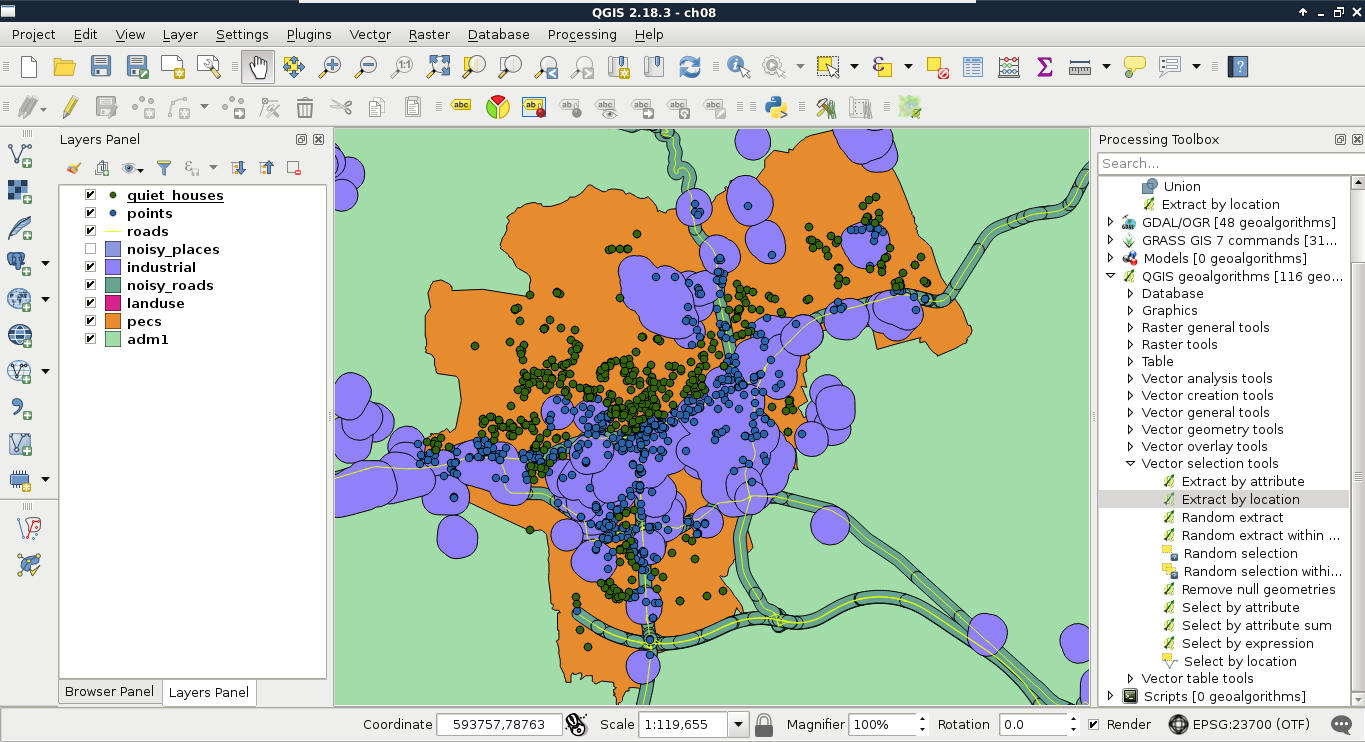

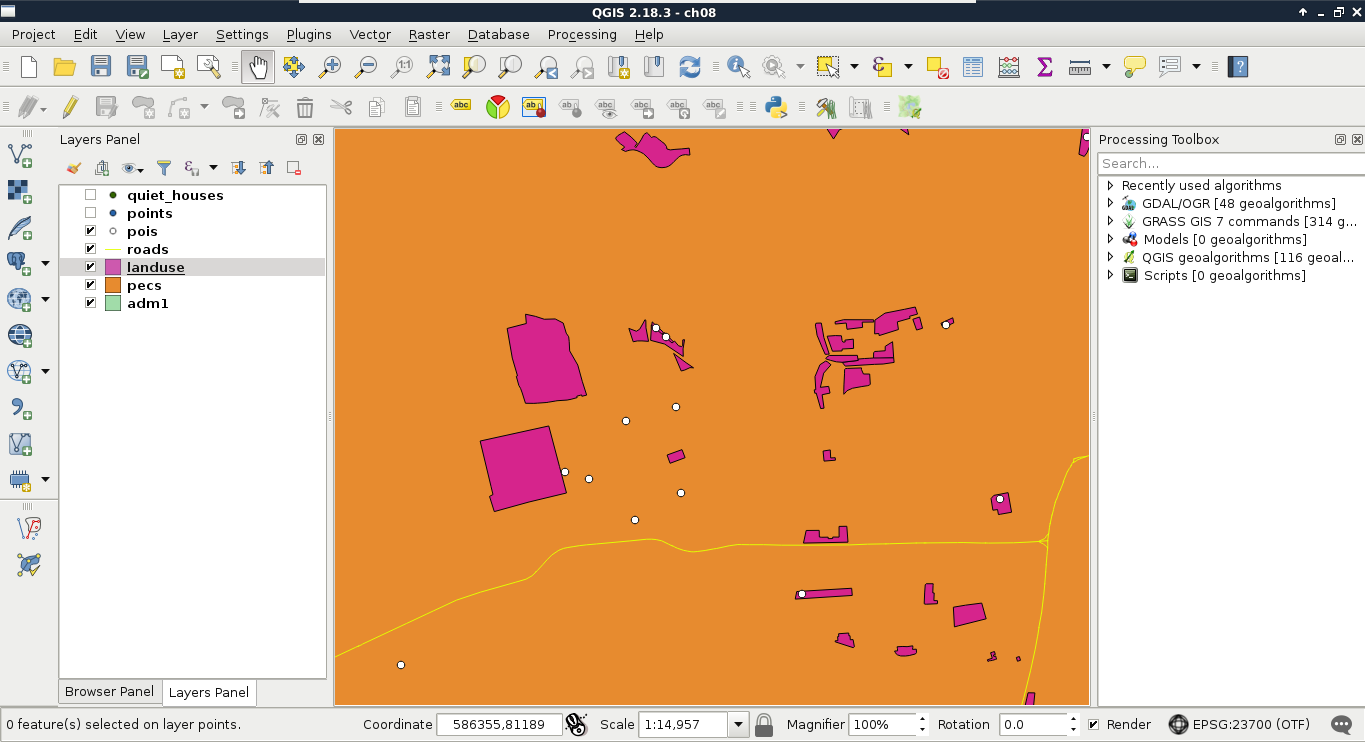

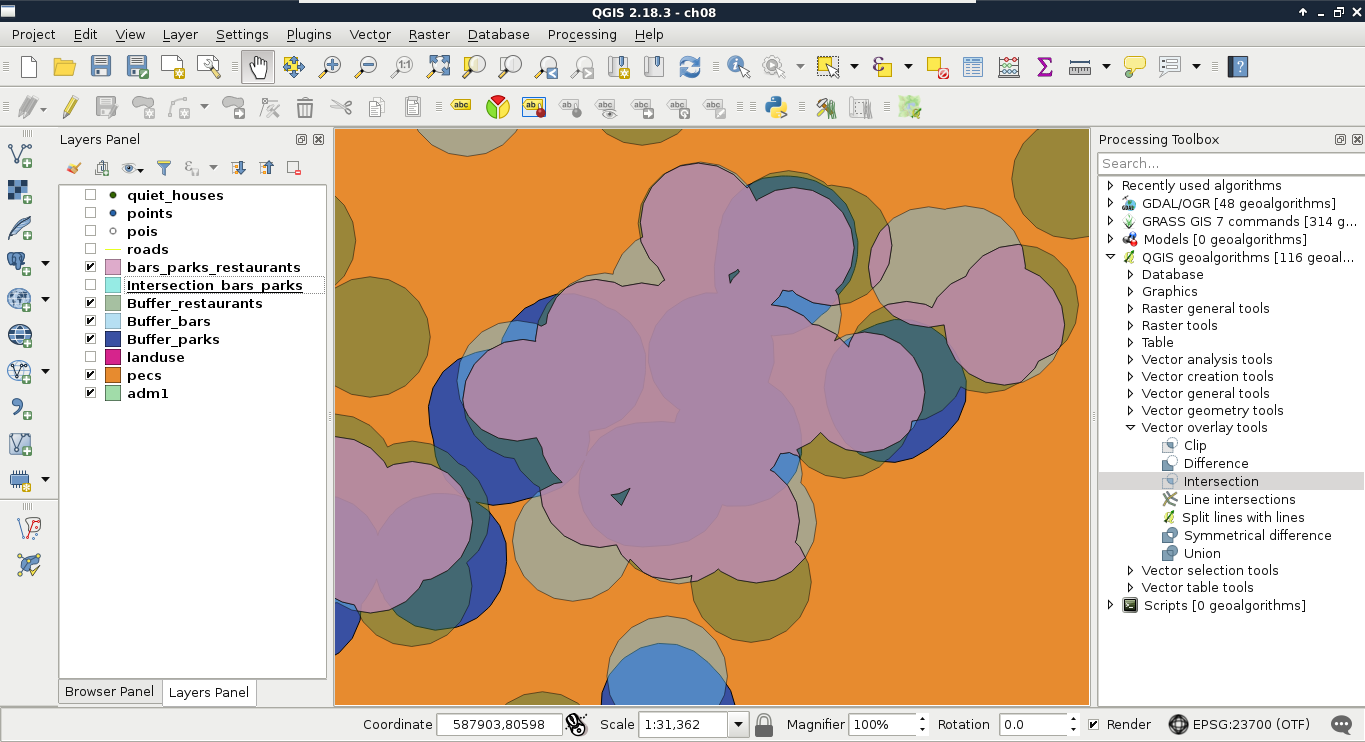

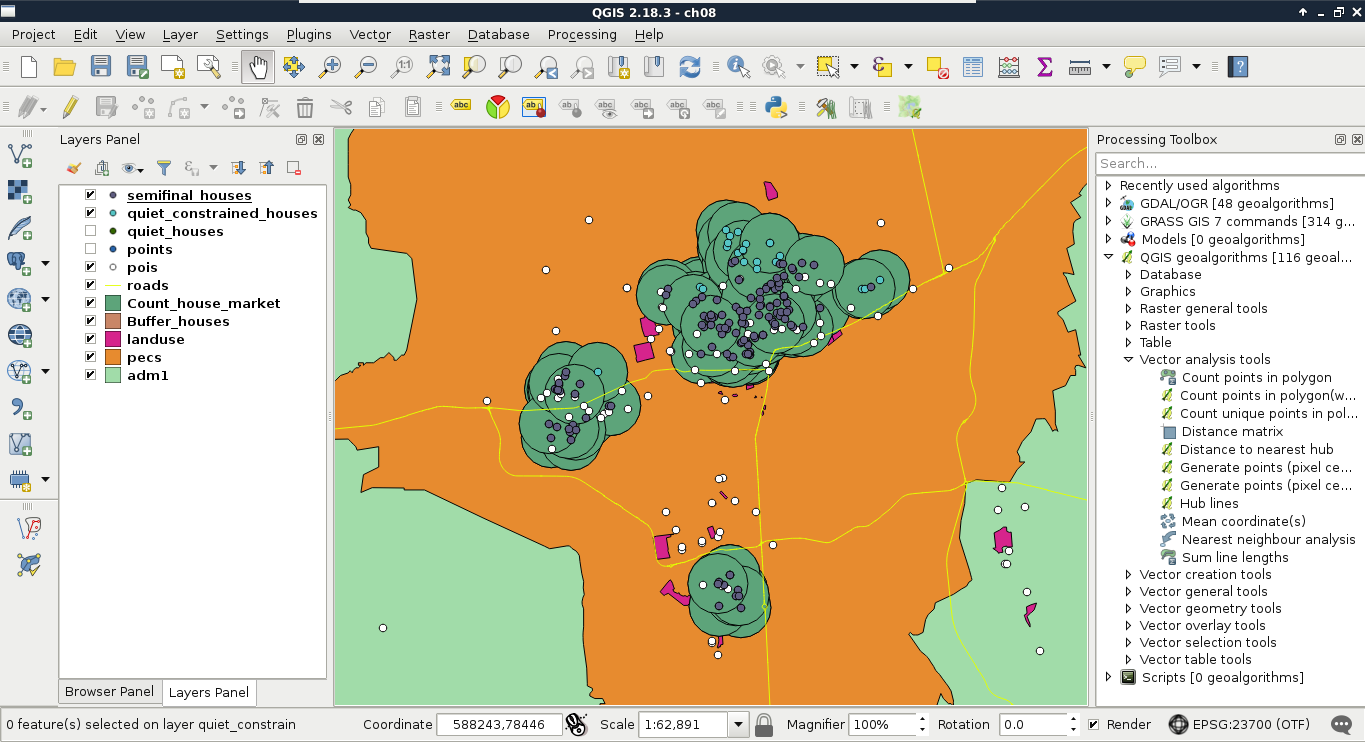

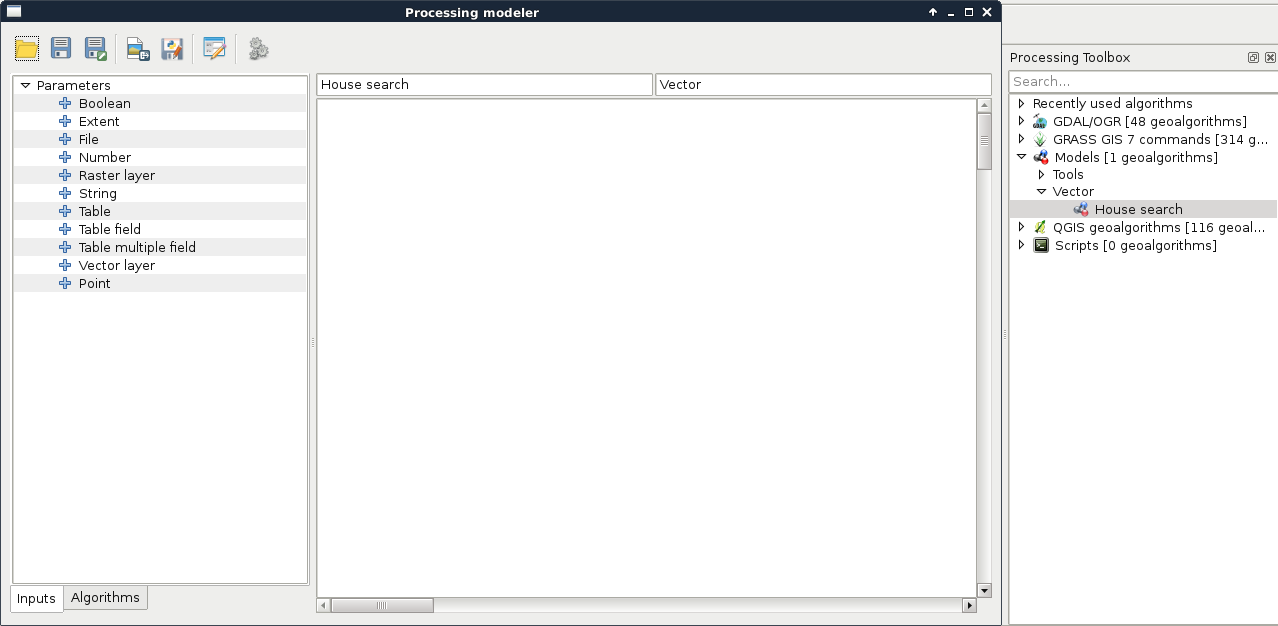

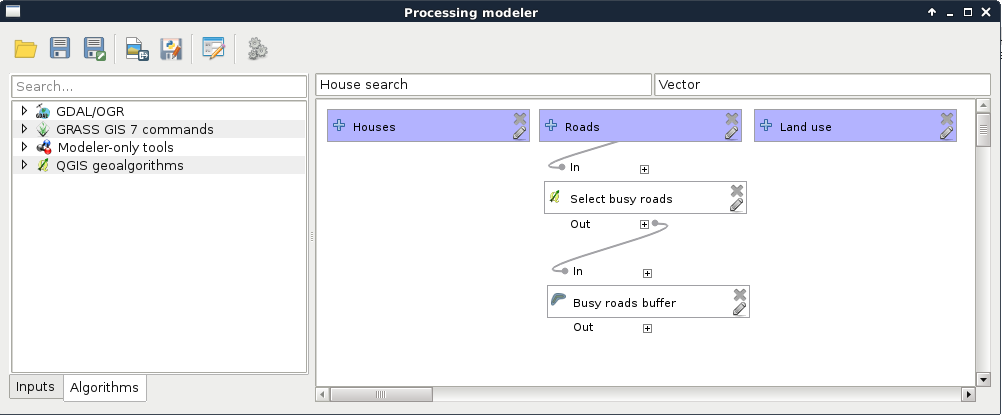

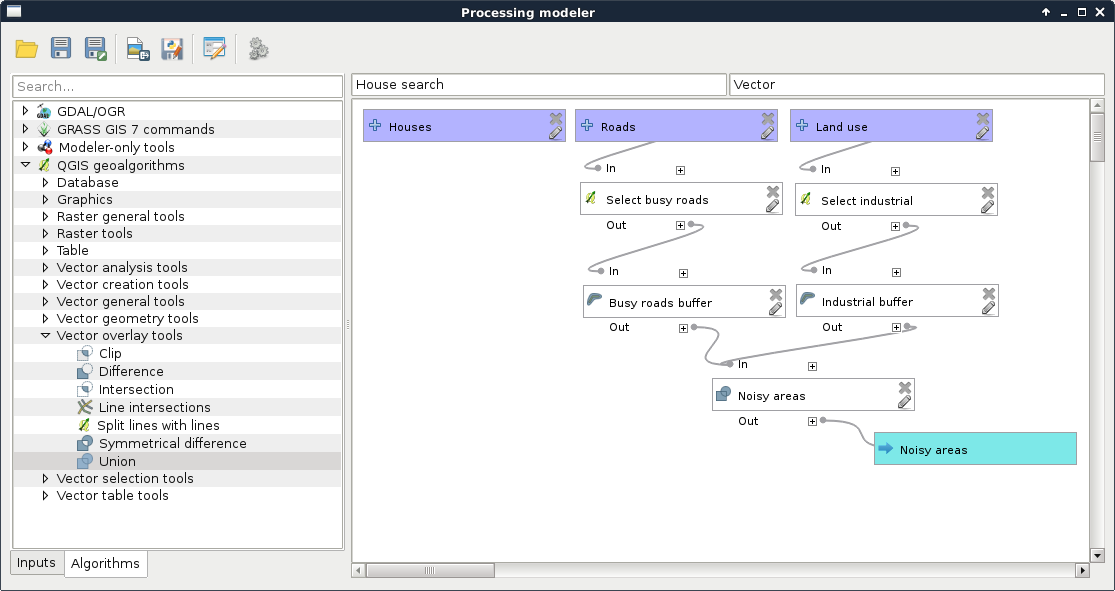

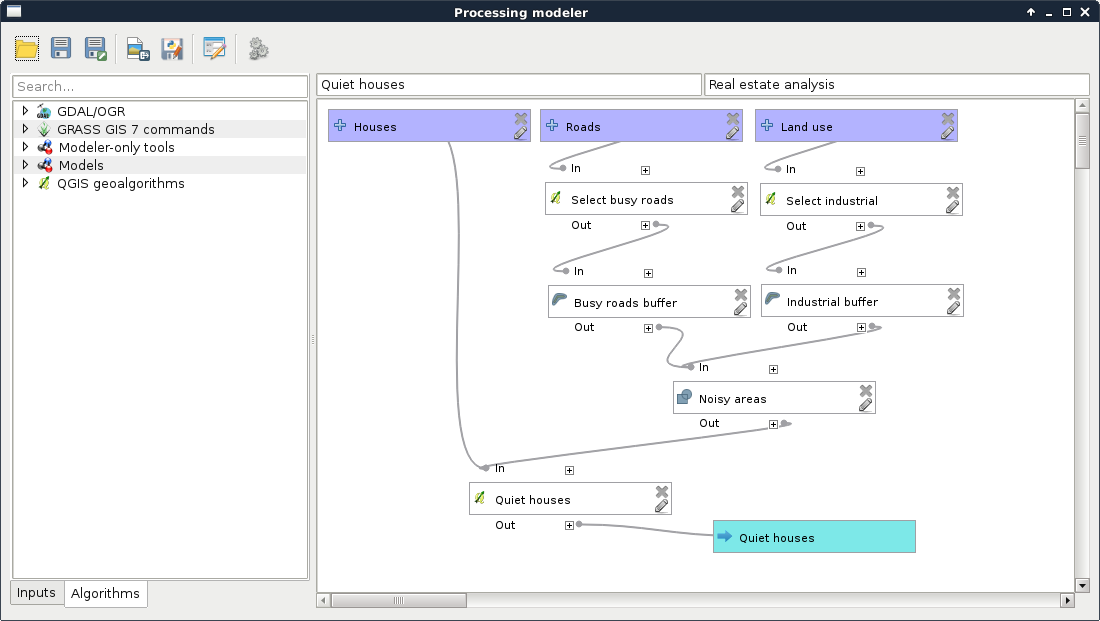

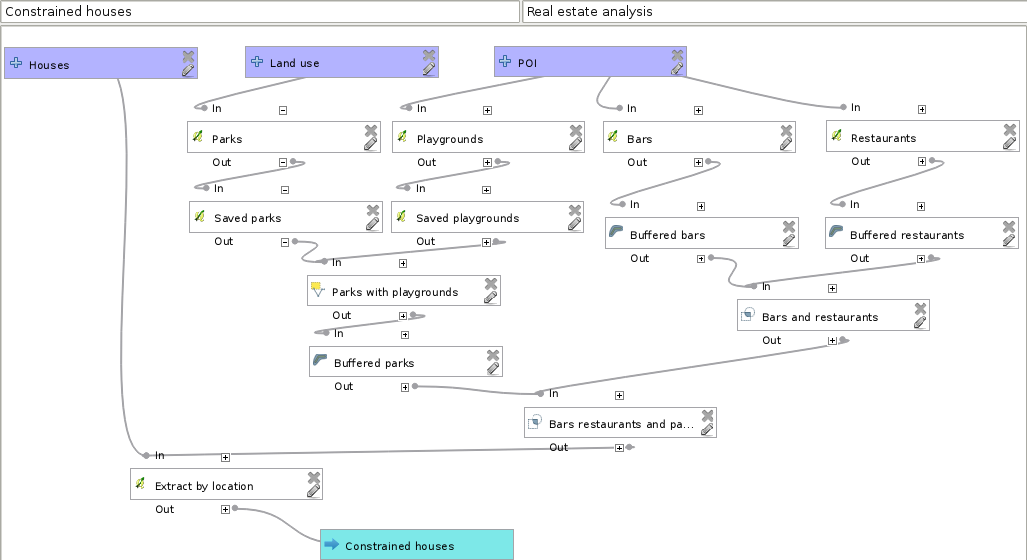

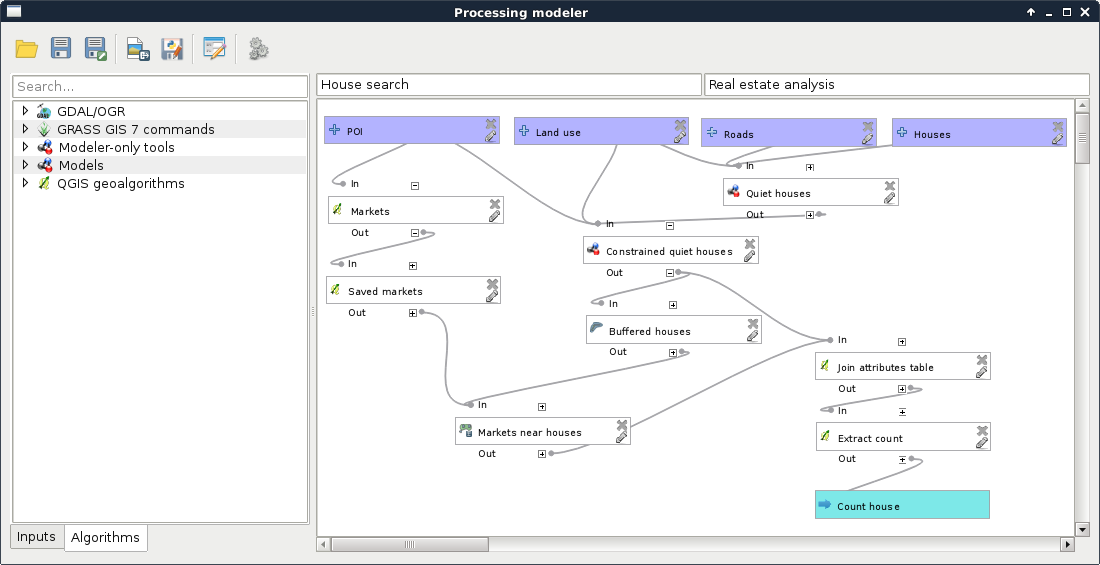

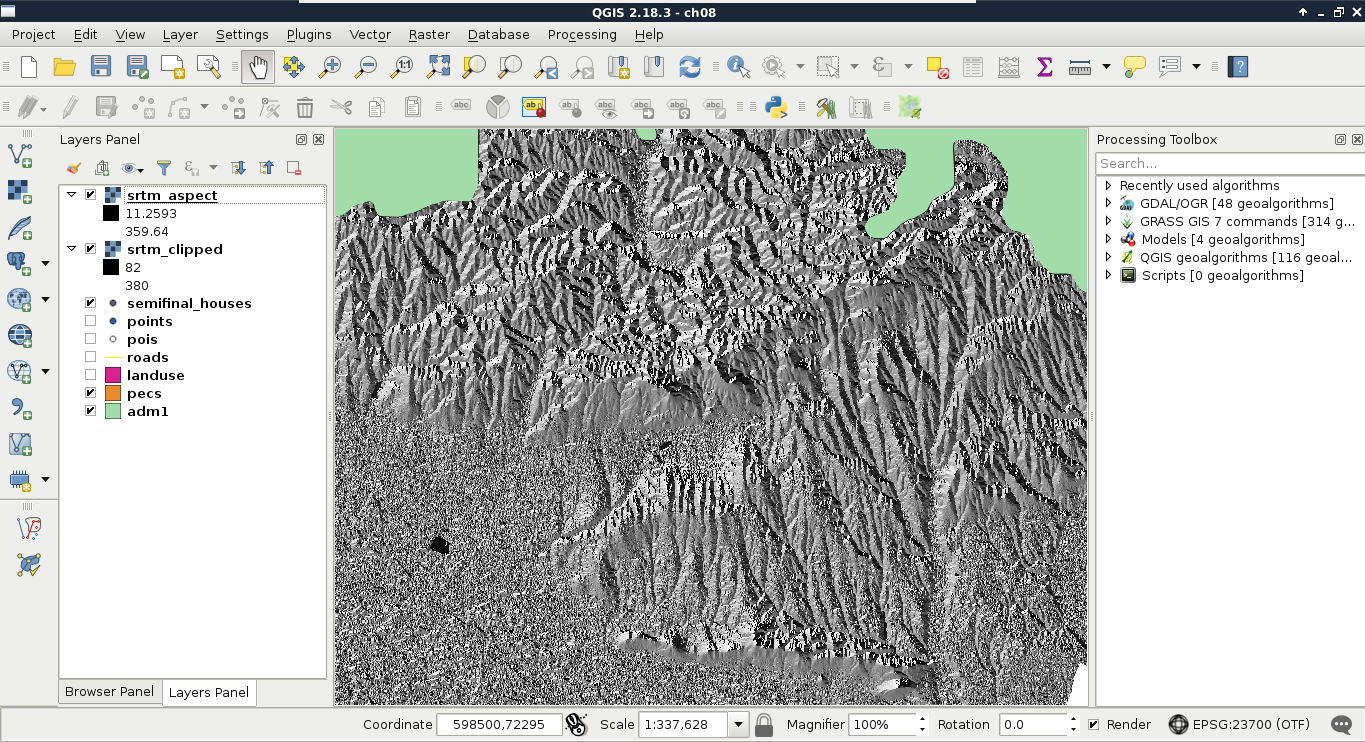

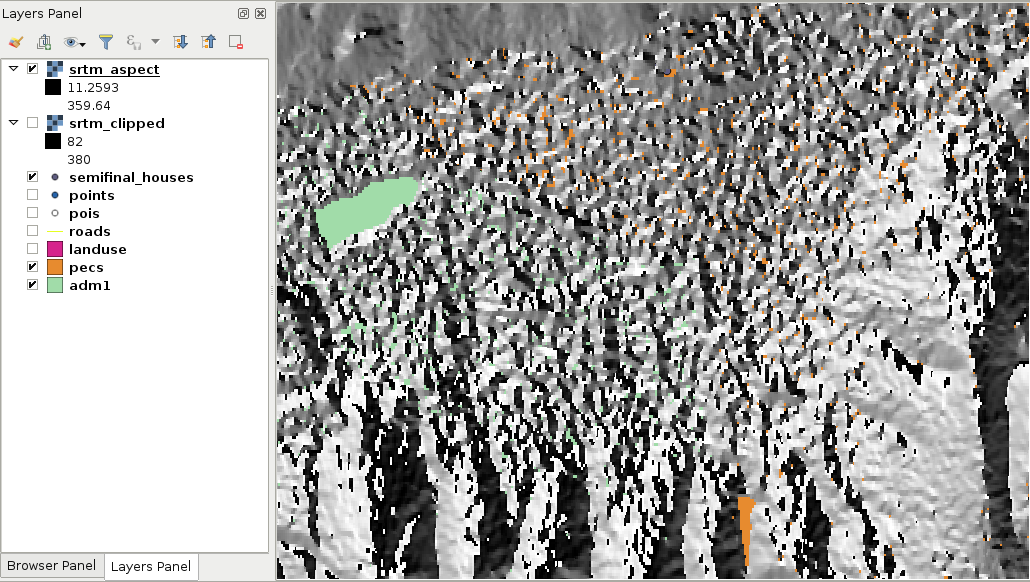

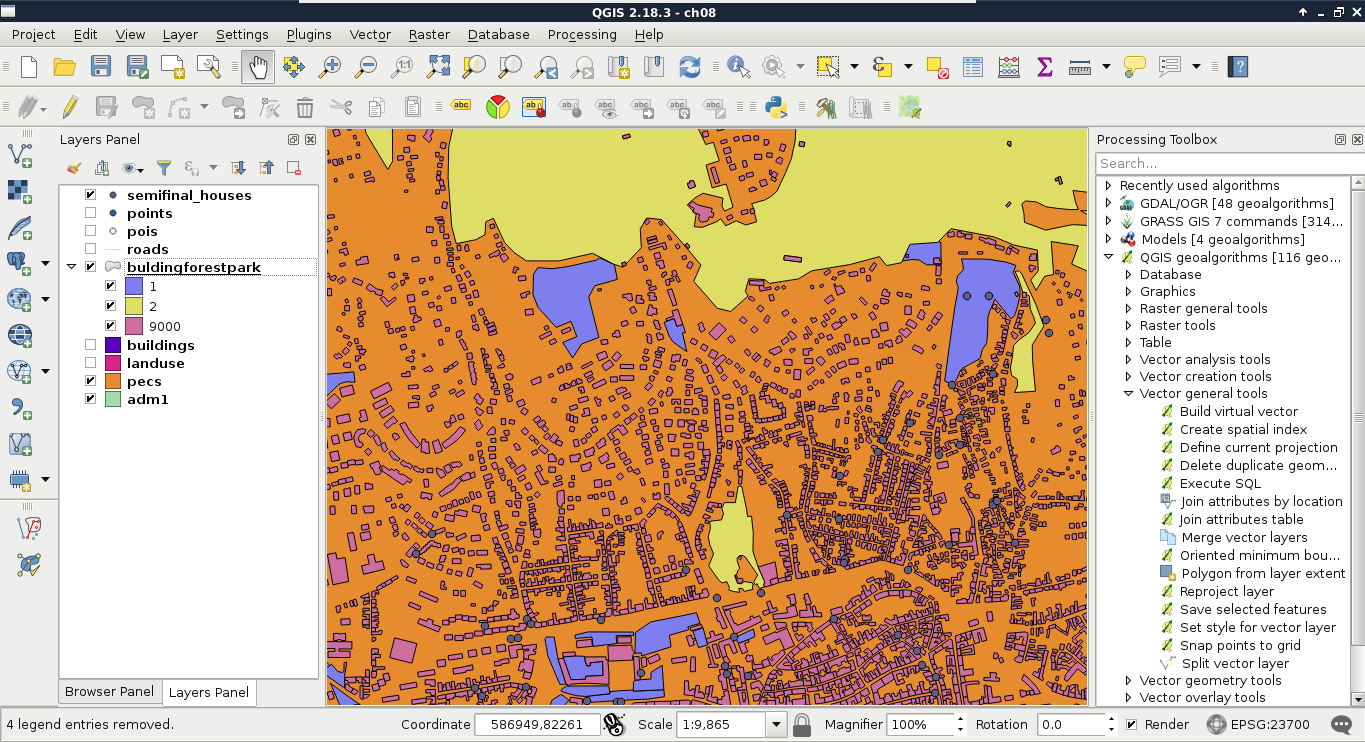

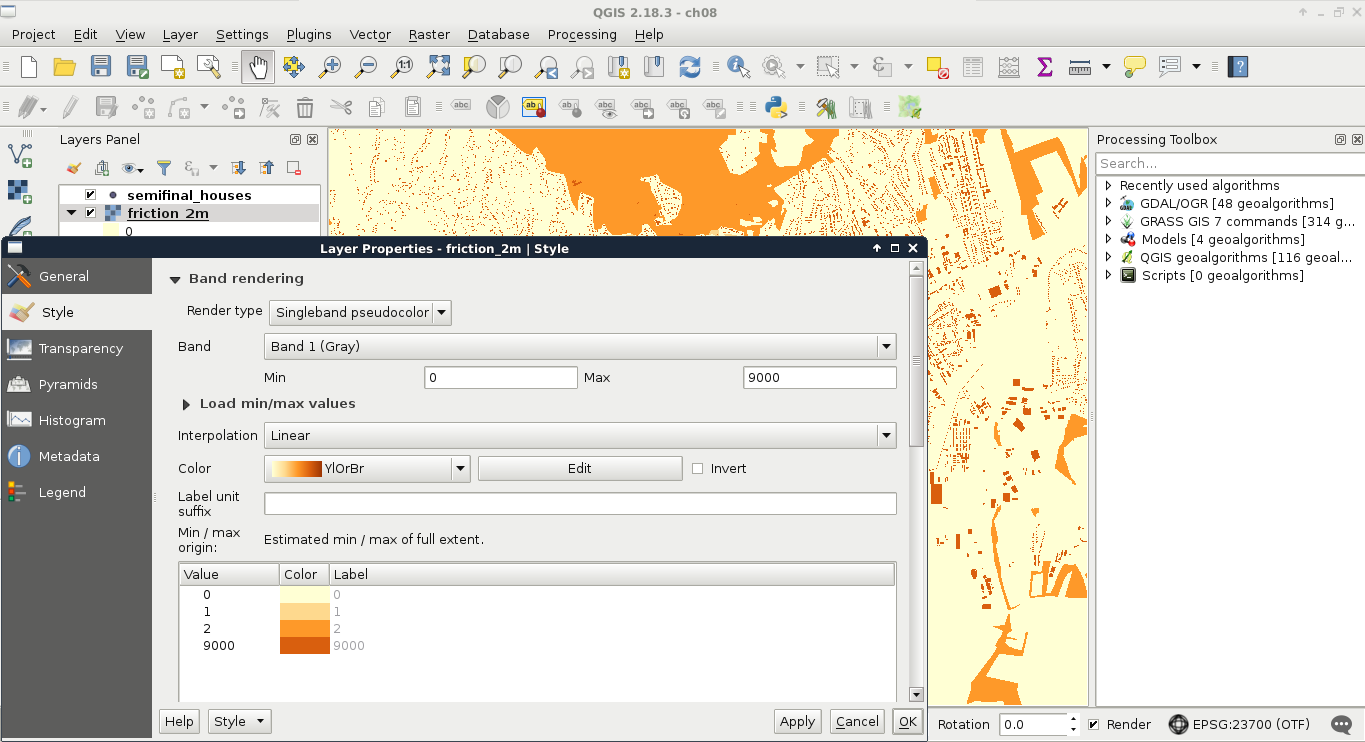

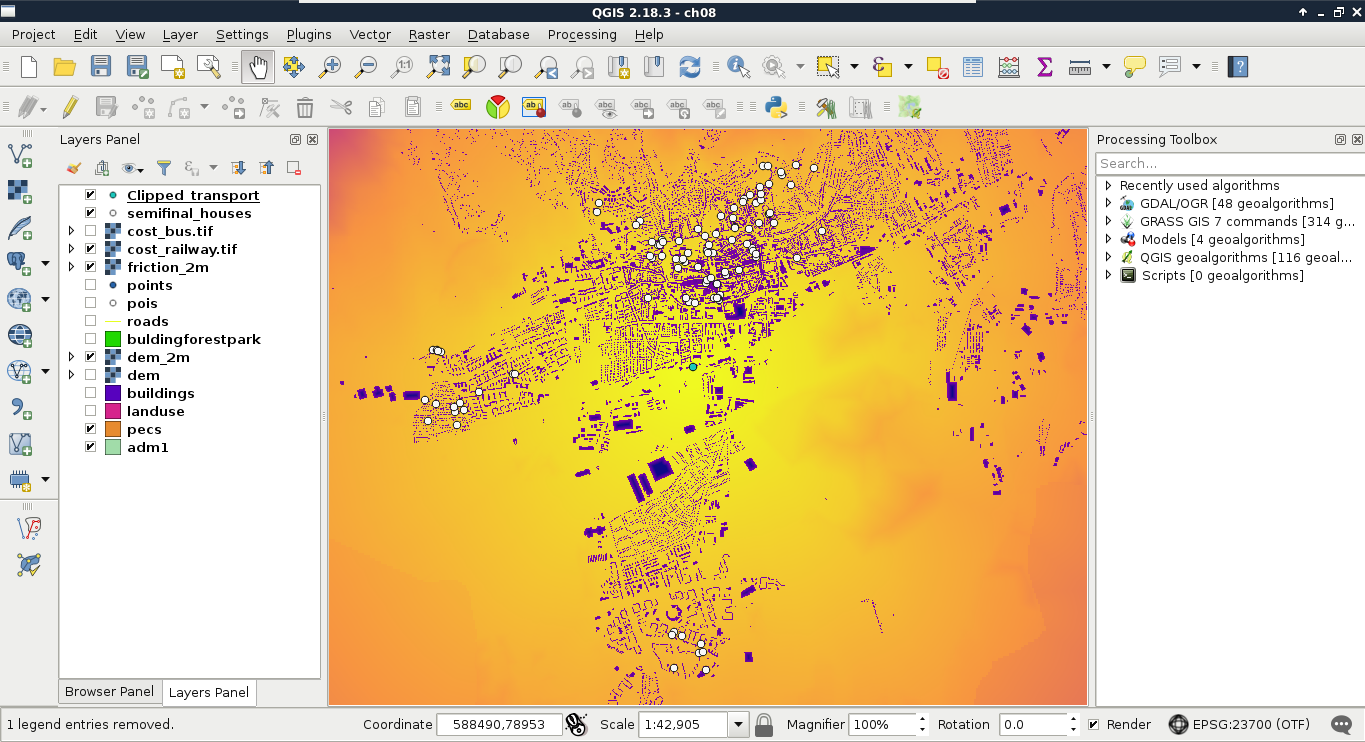

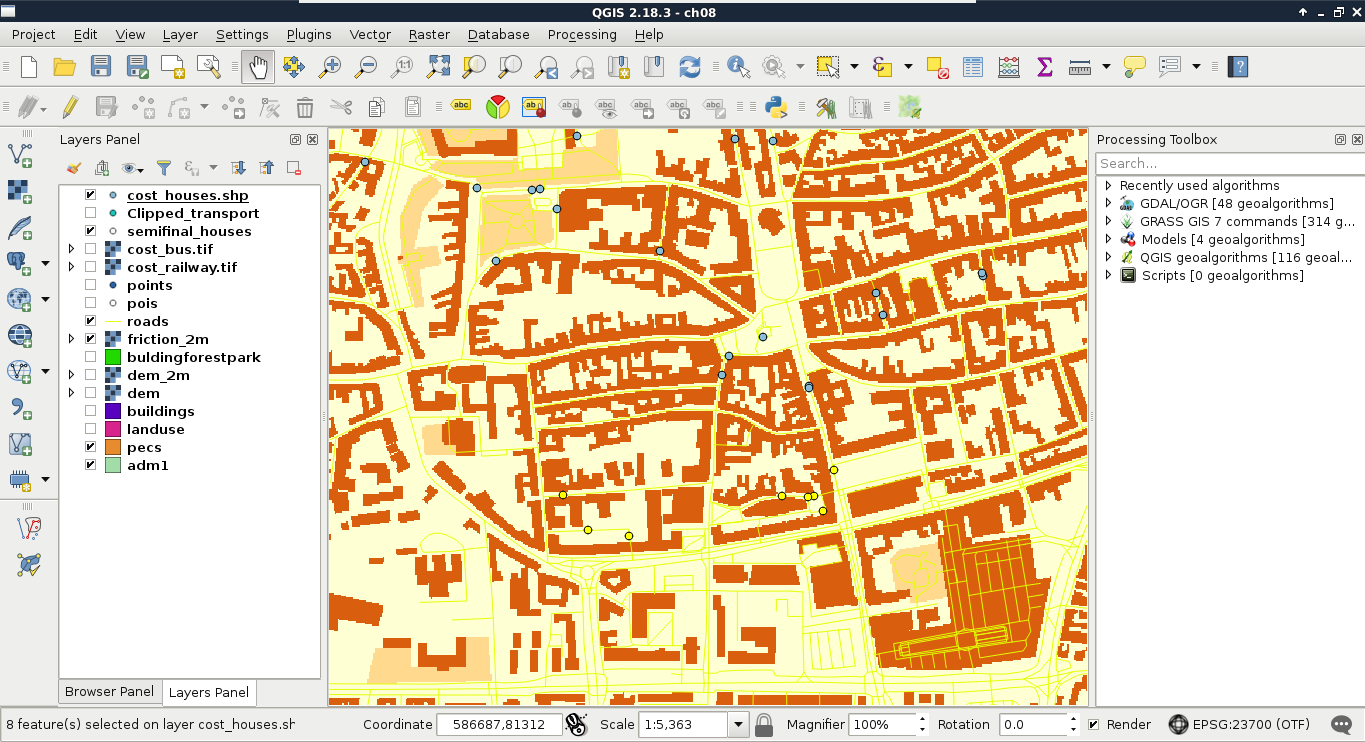

Chapter 8, Spatial Analysis in QGIS, goes back to QGIS in order to discuss vector data analysis and spatial modeling. It shows you how different geometry types can be used to get some meaningful results based on the features' spatial relationship. It goes through the practical textbook example of delimiting houses based on some customer preferences.

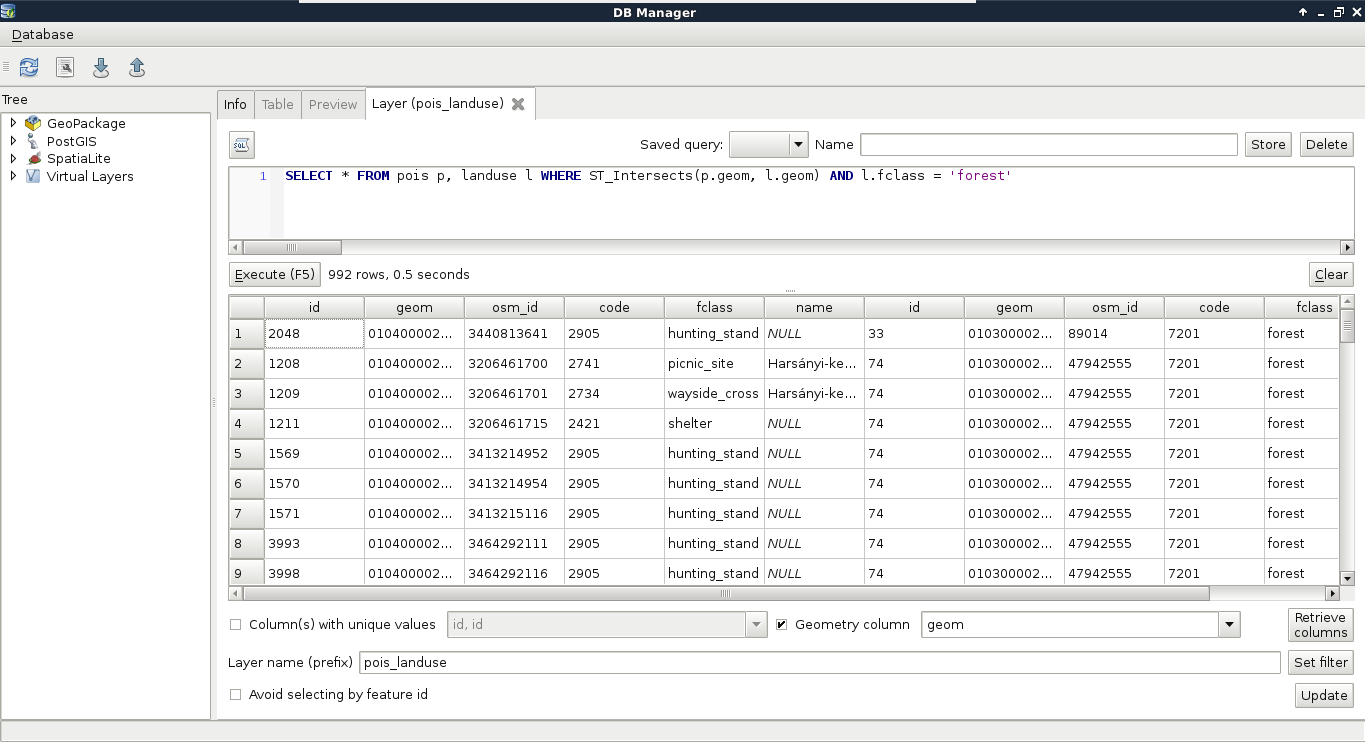

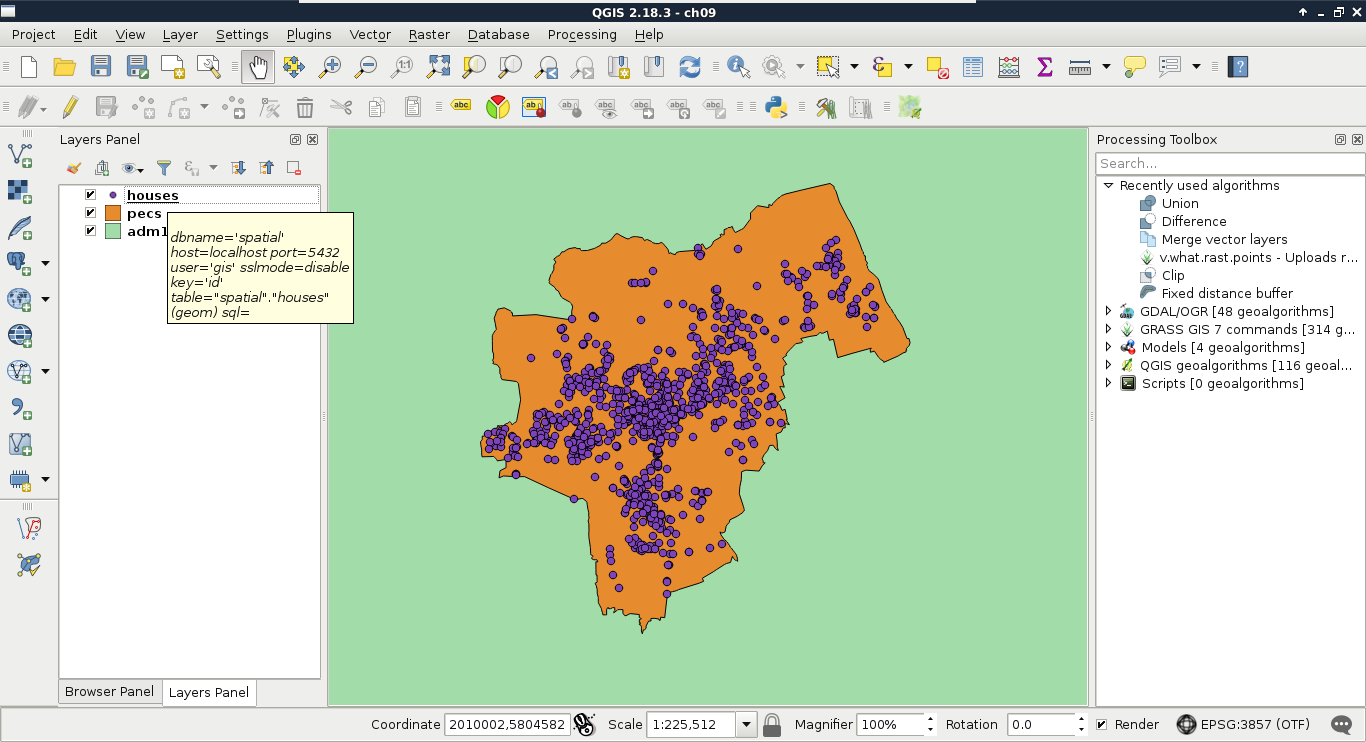

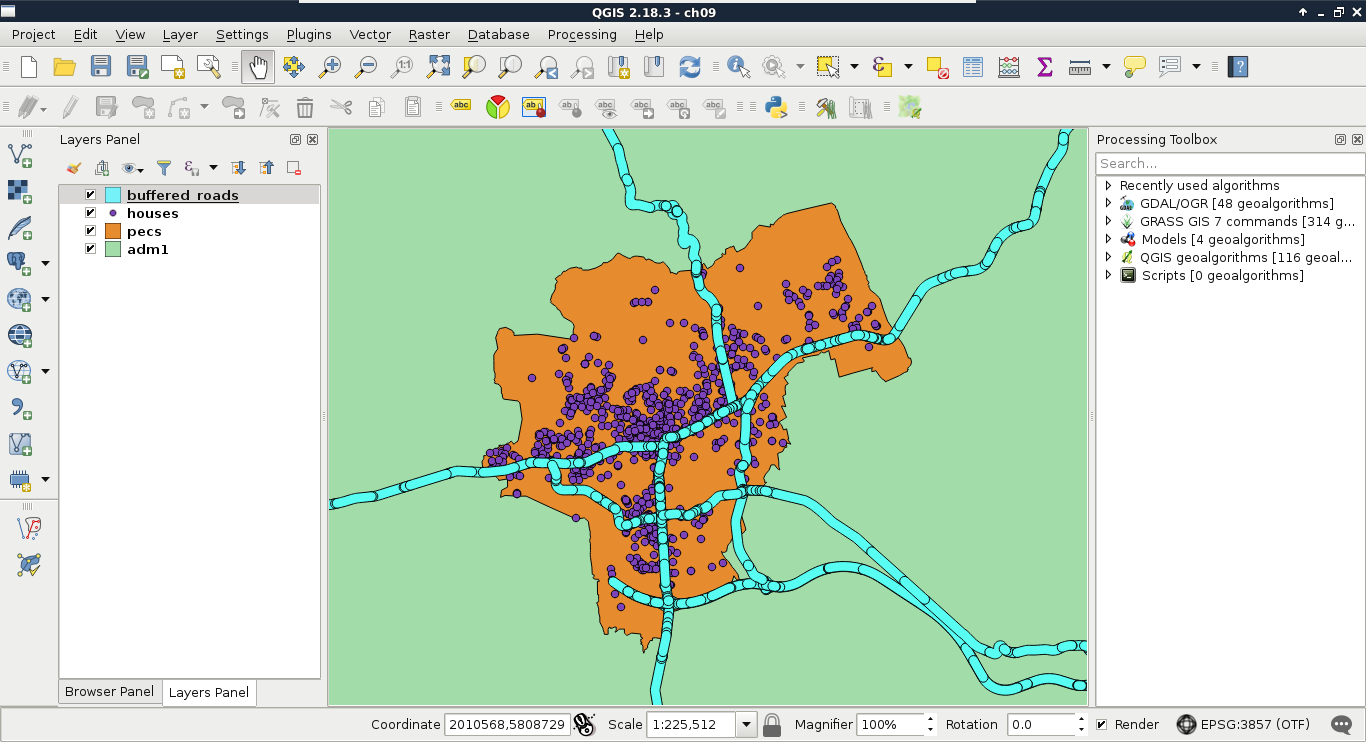

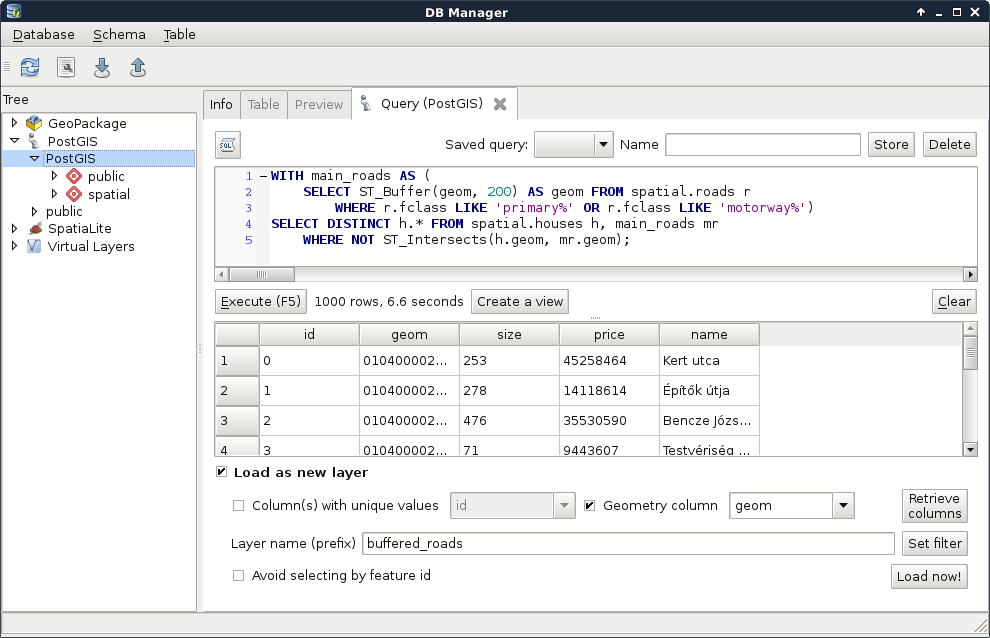

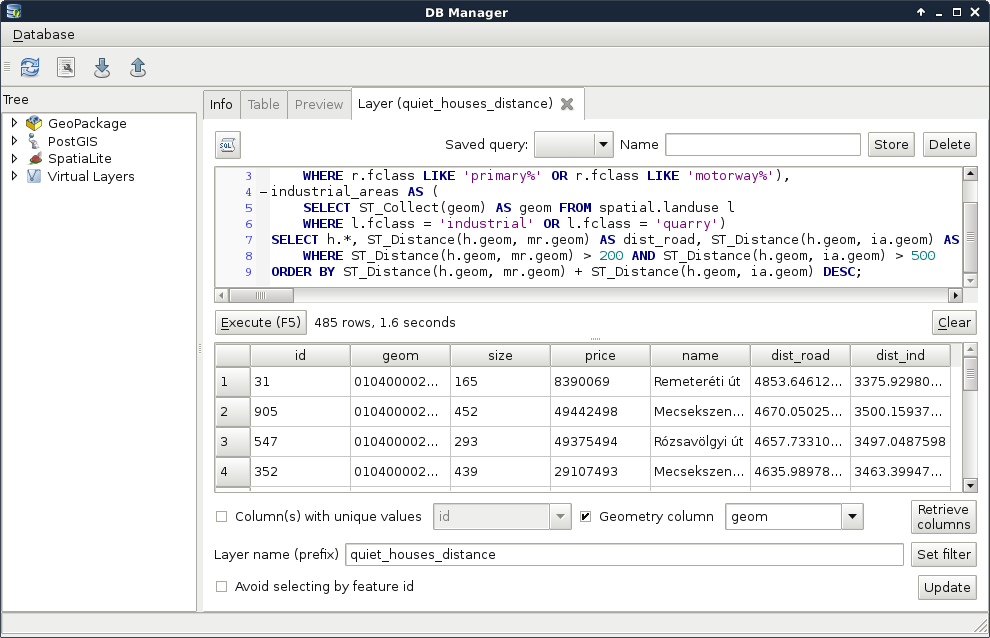

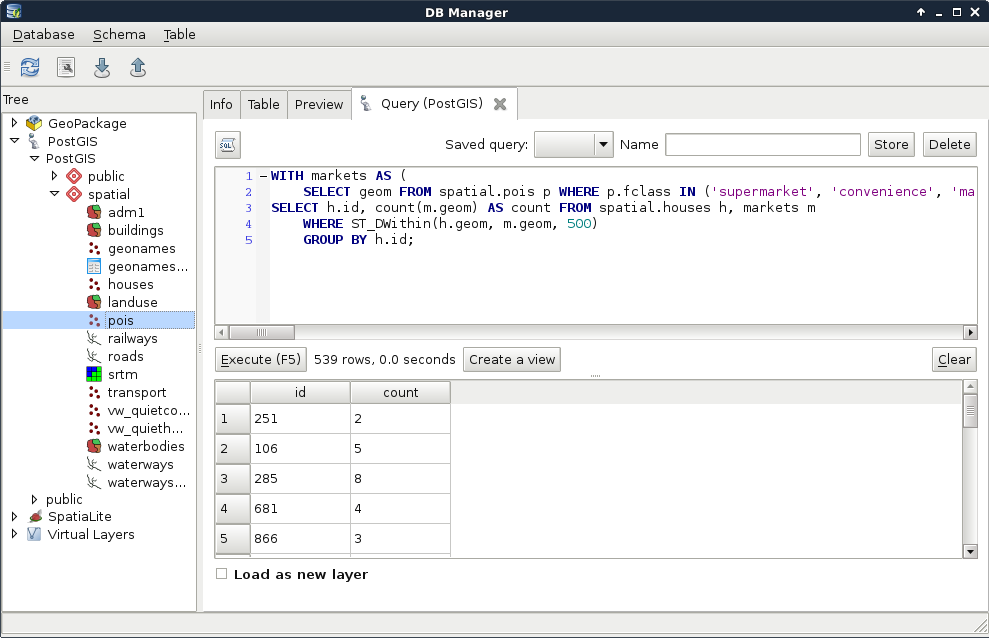

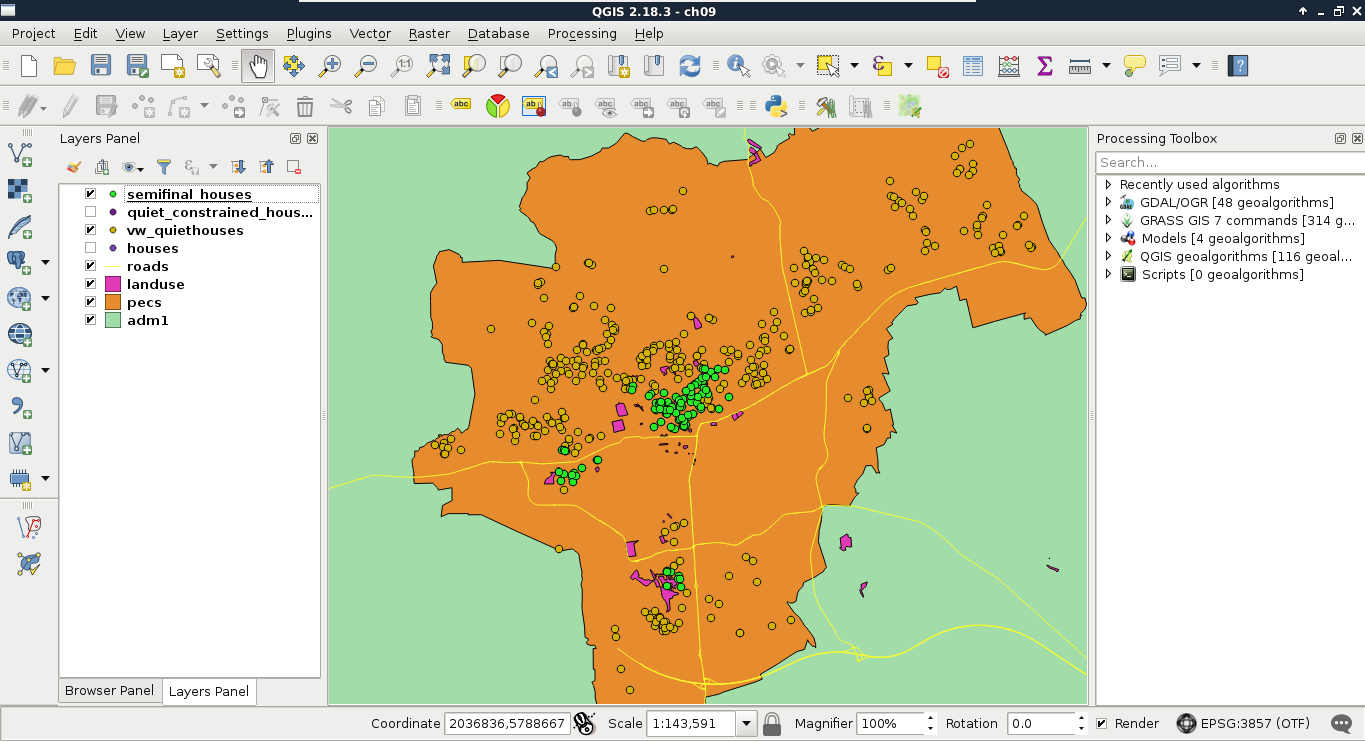

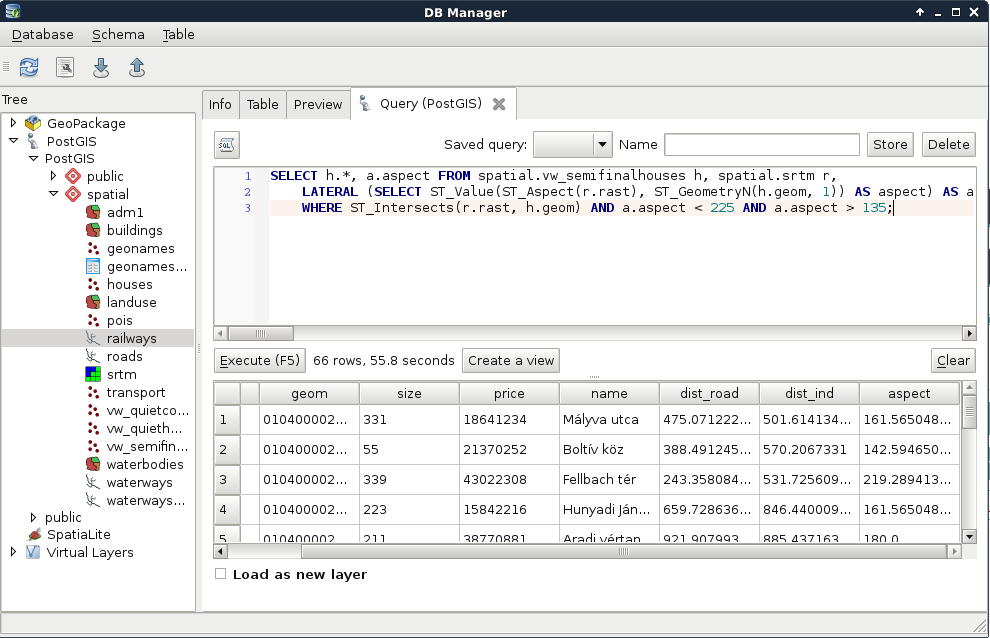

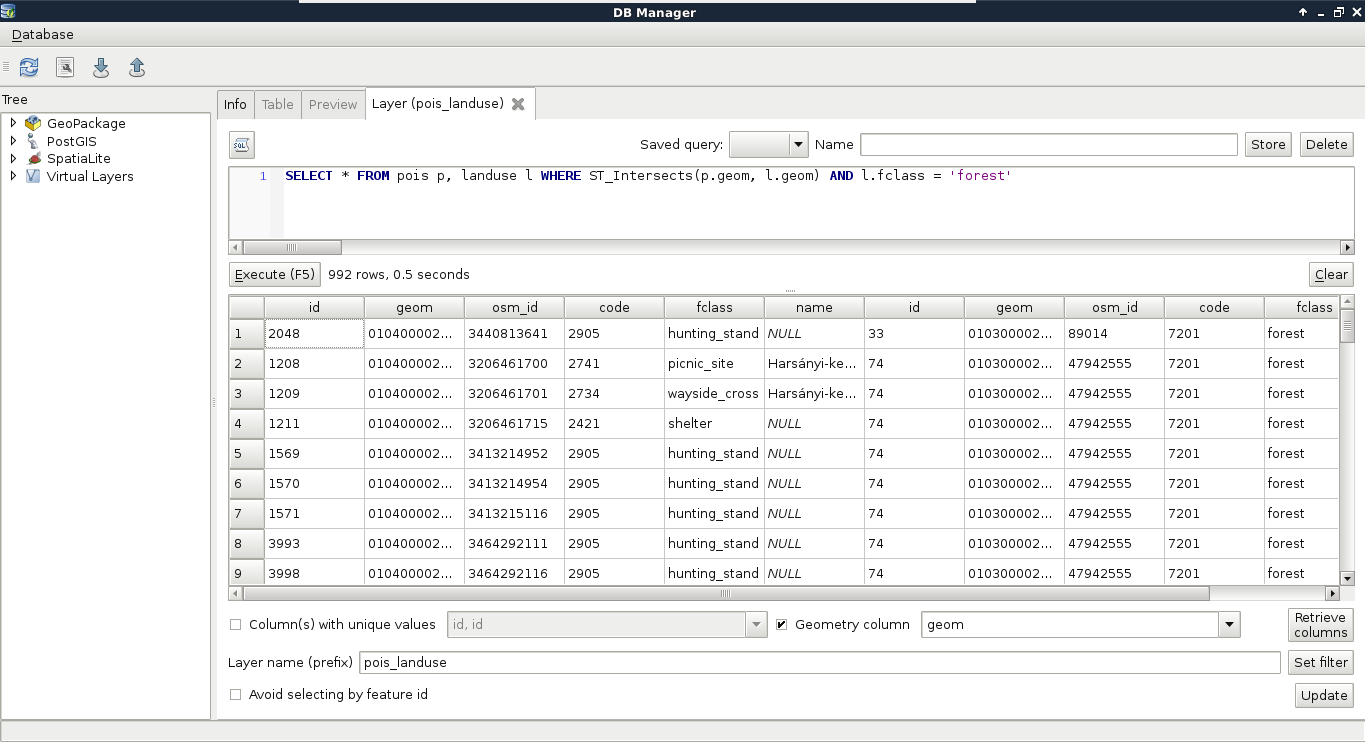

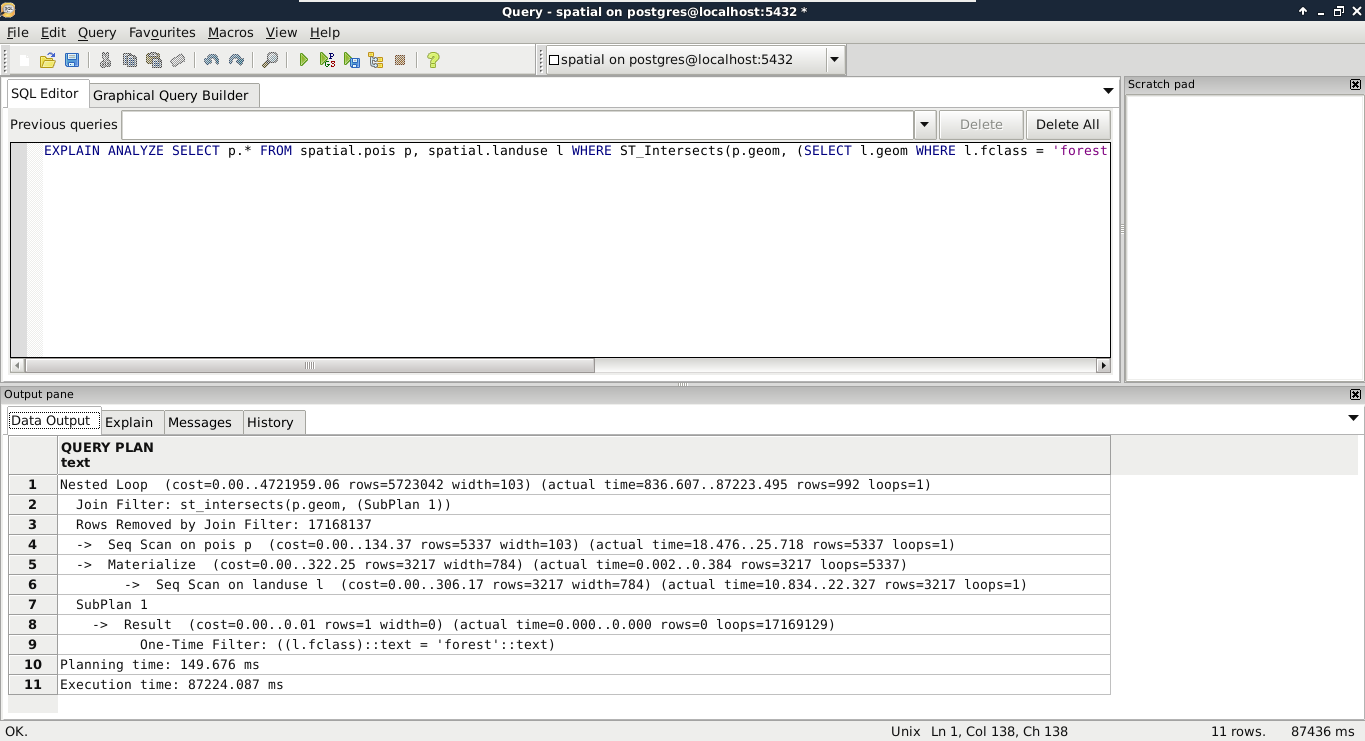

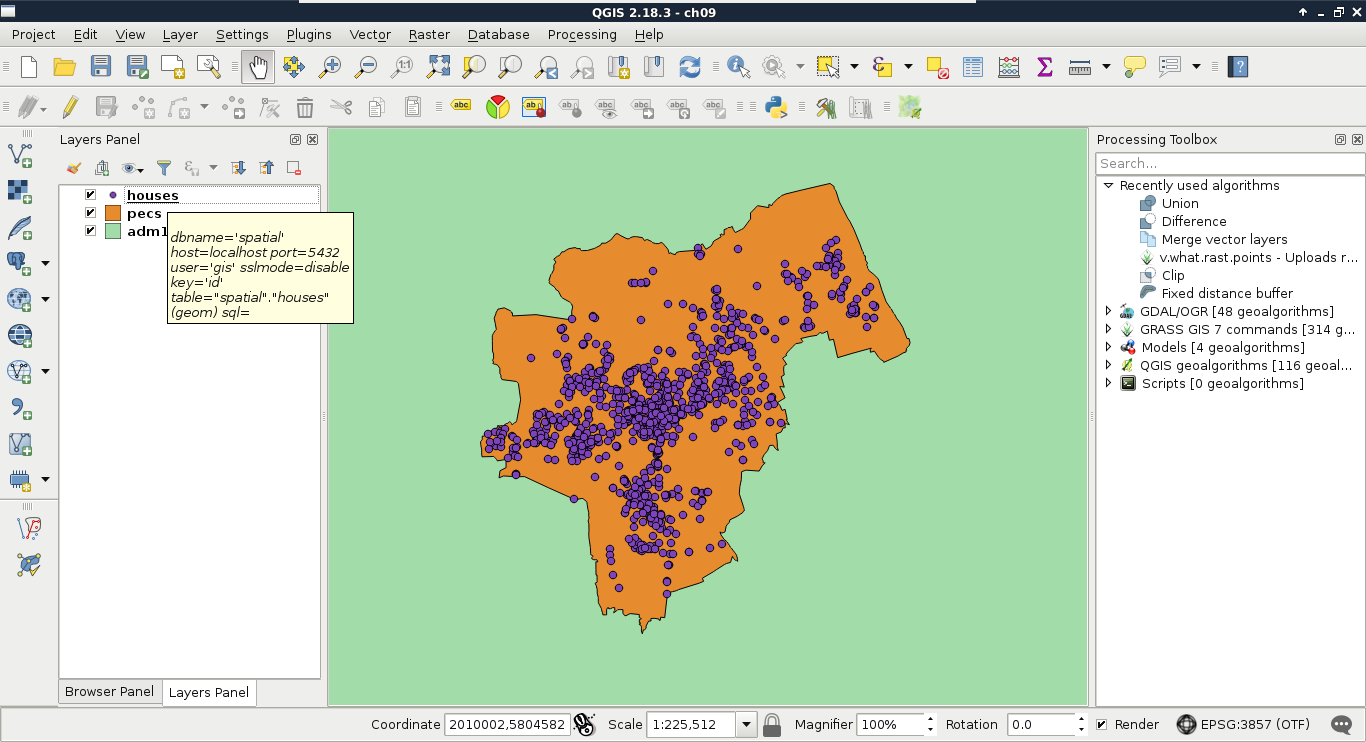

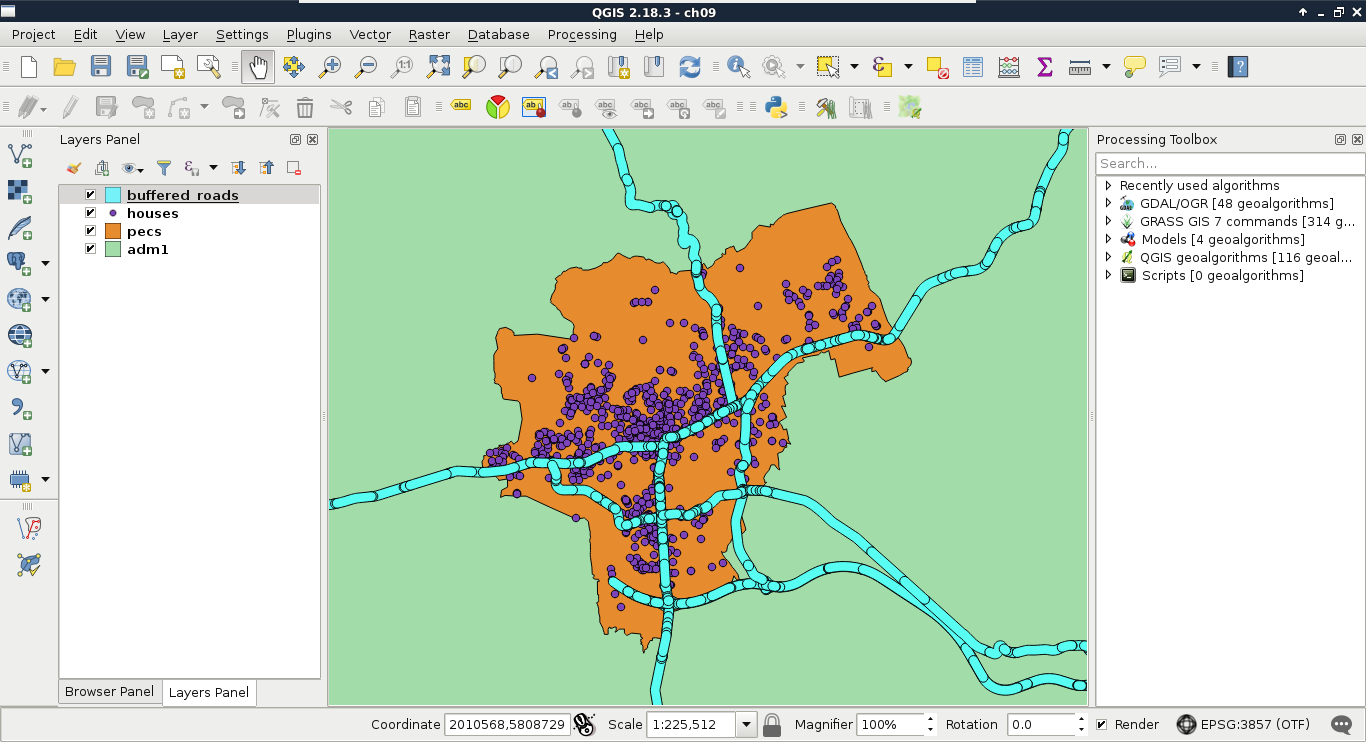

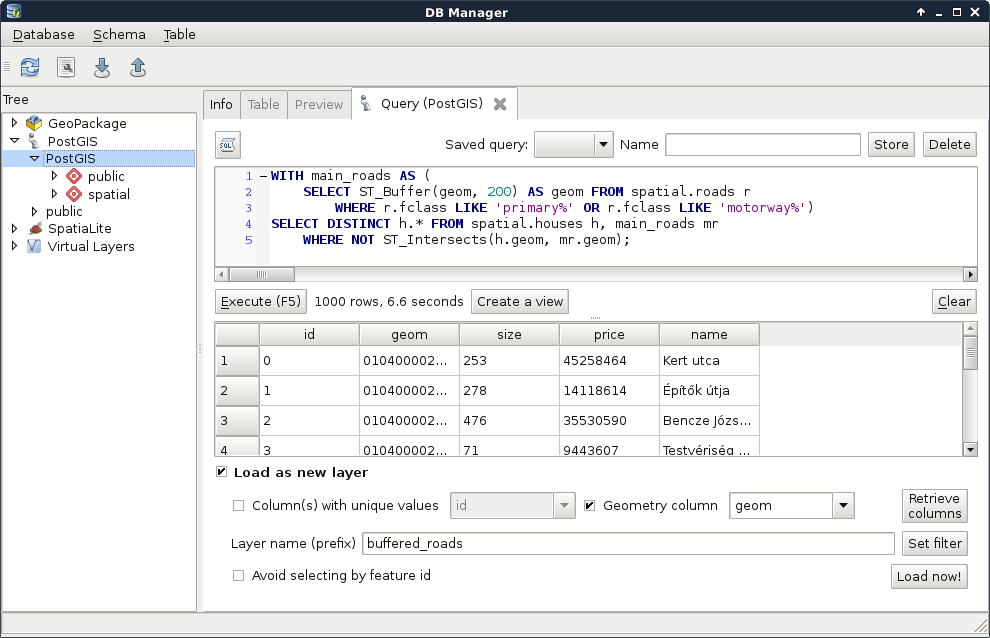

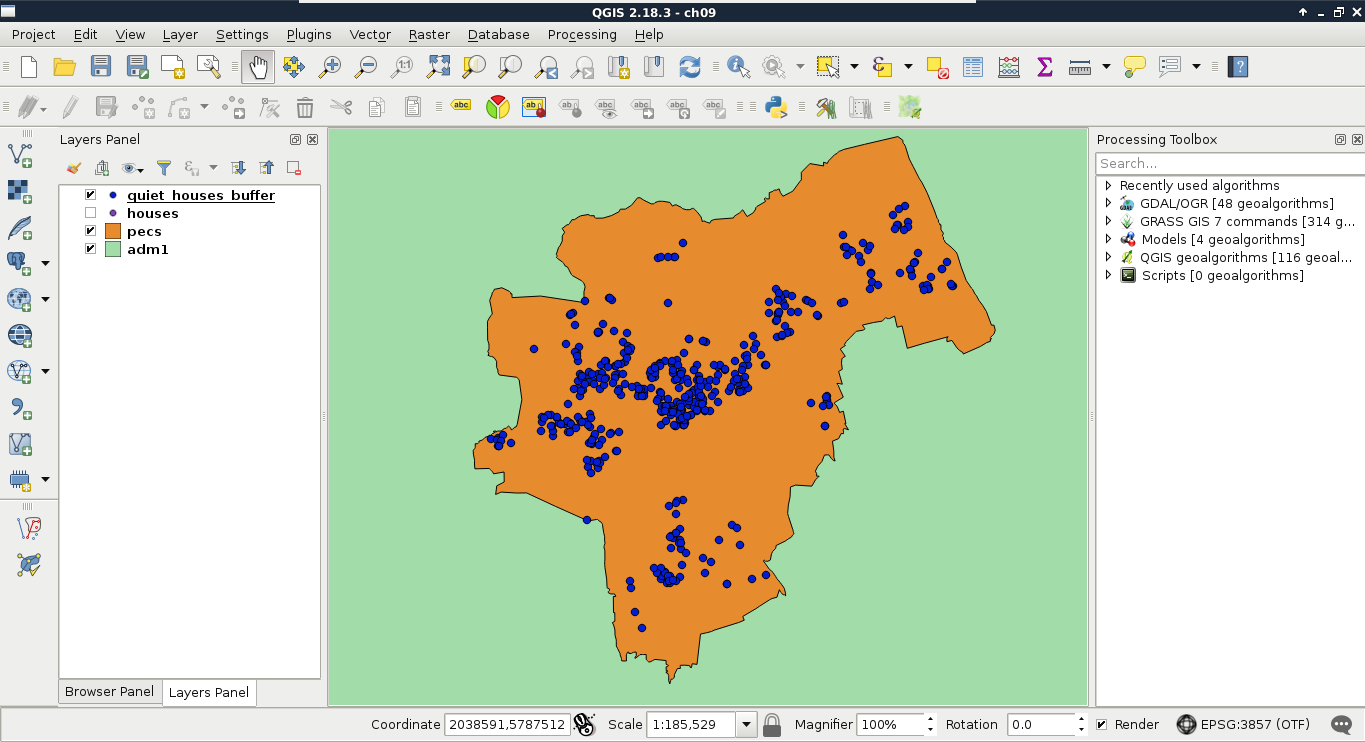

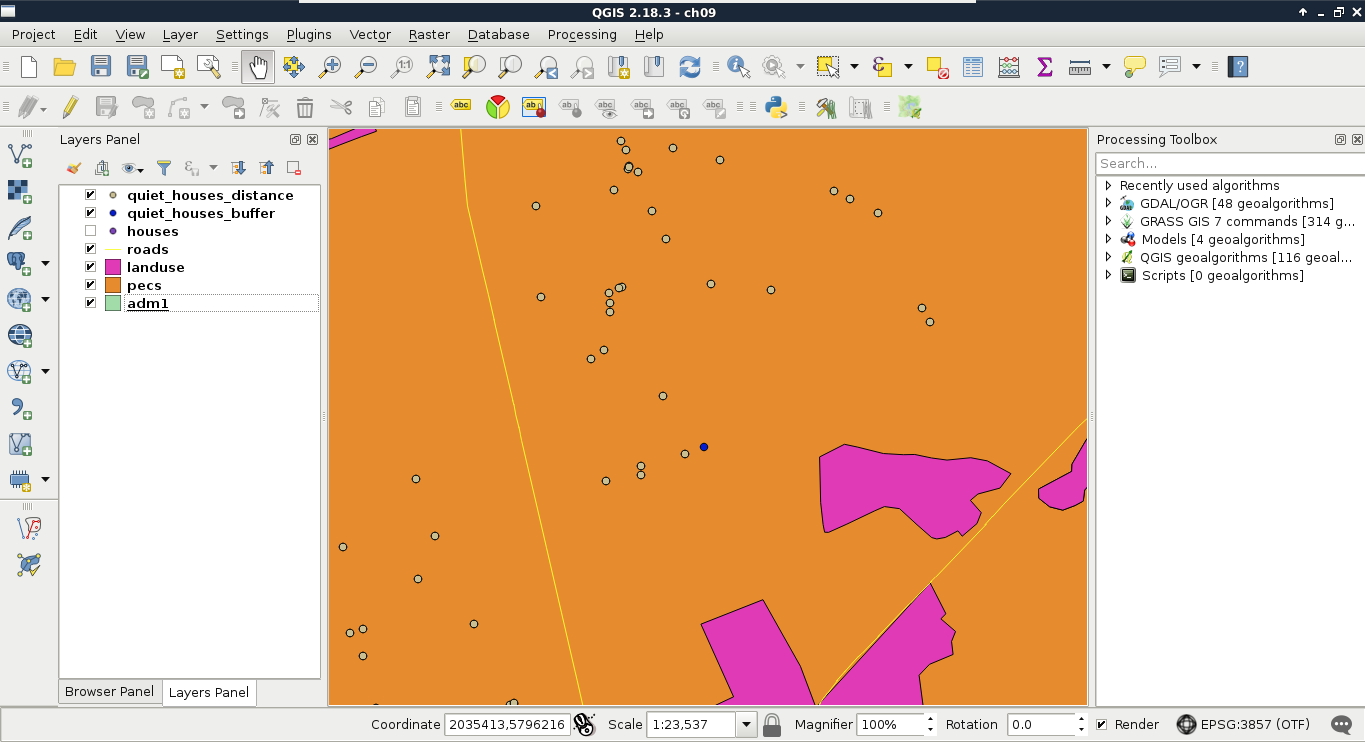

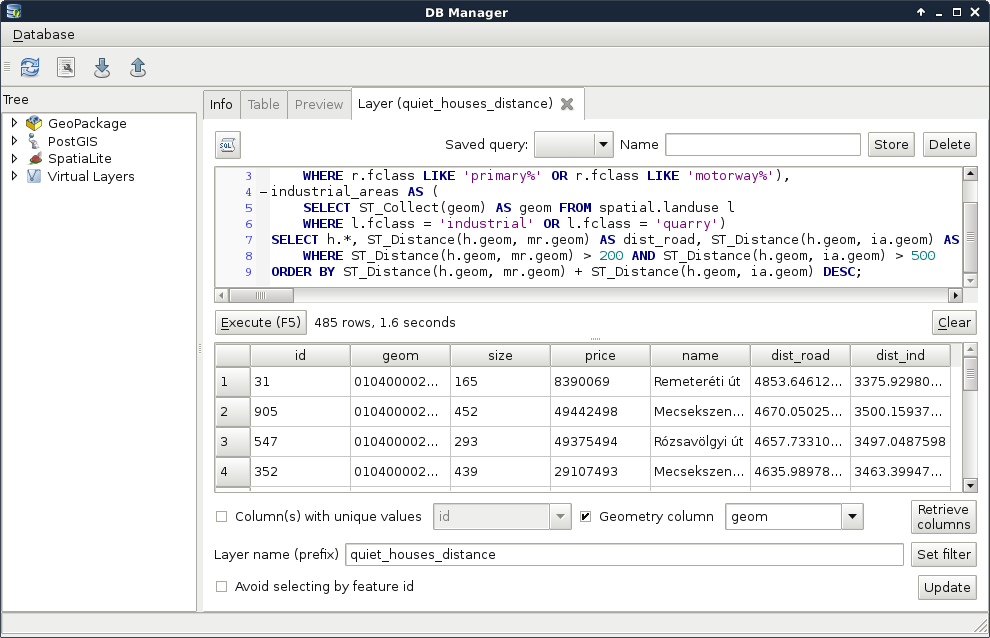

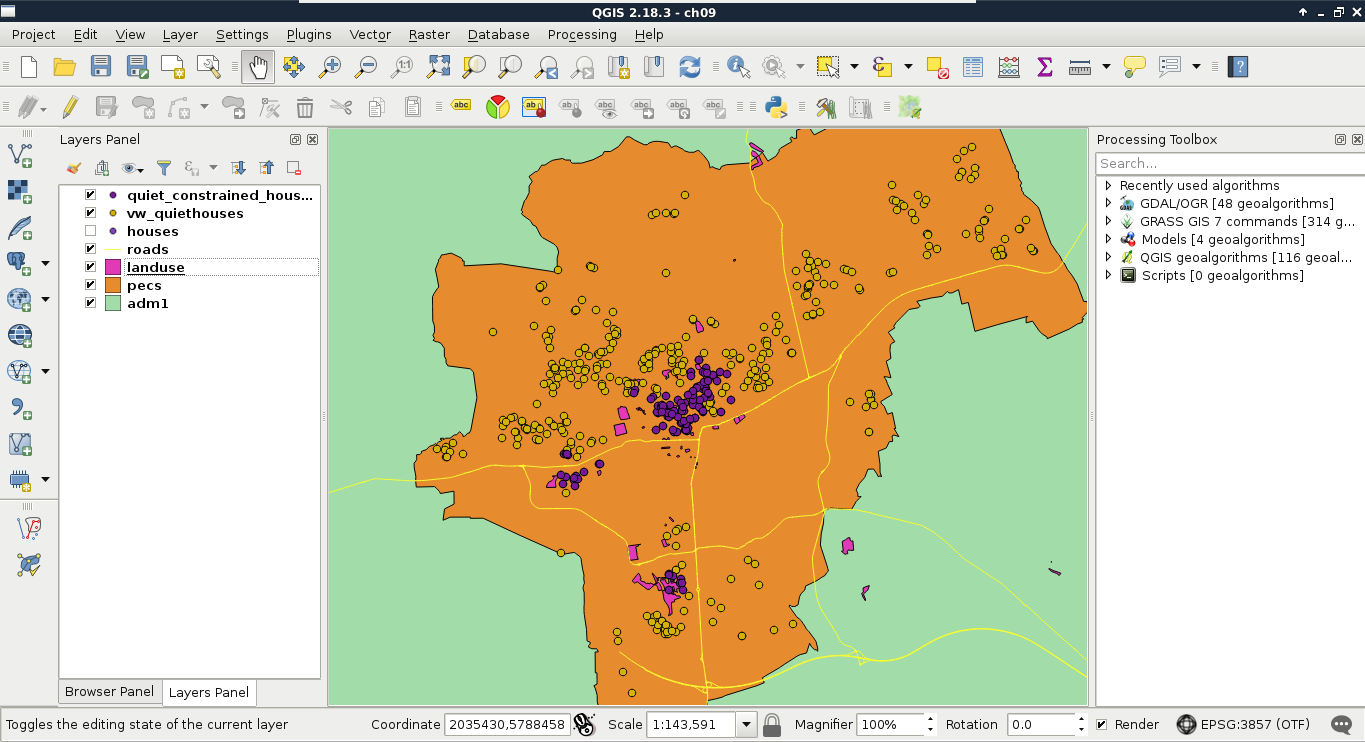

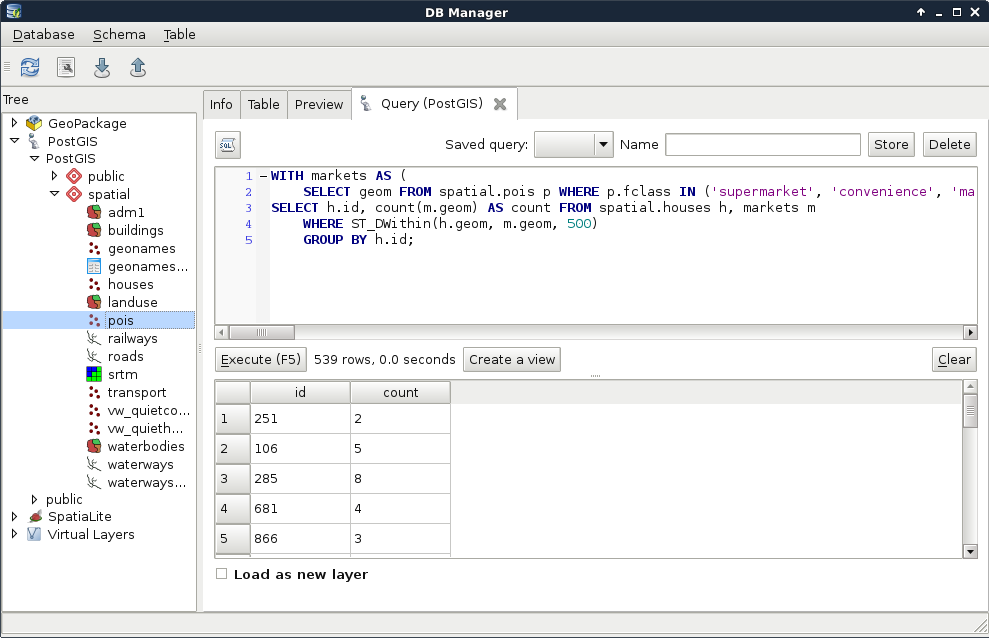

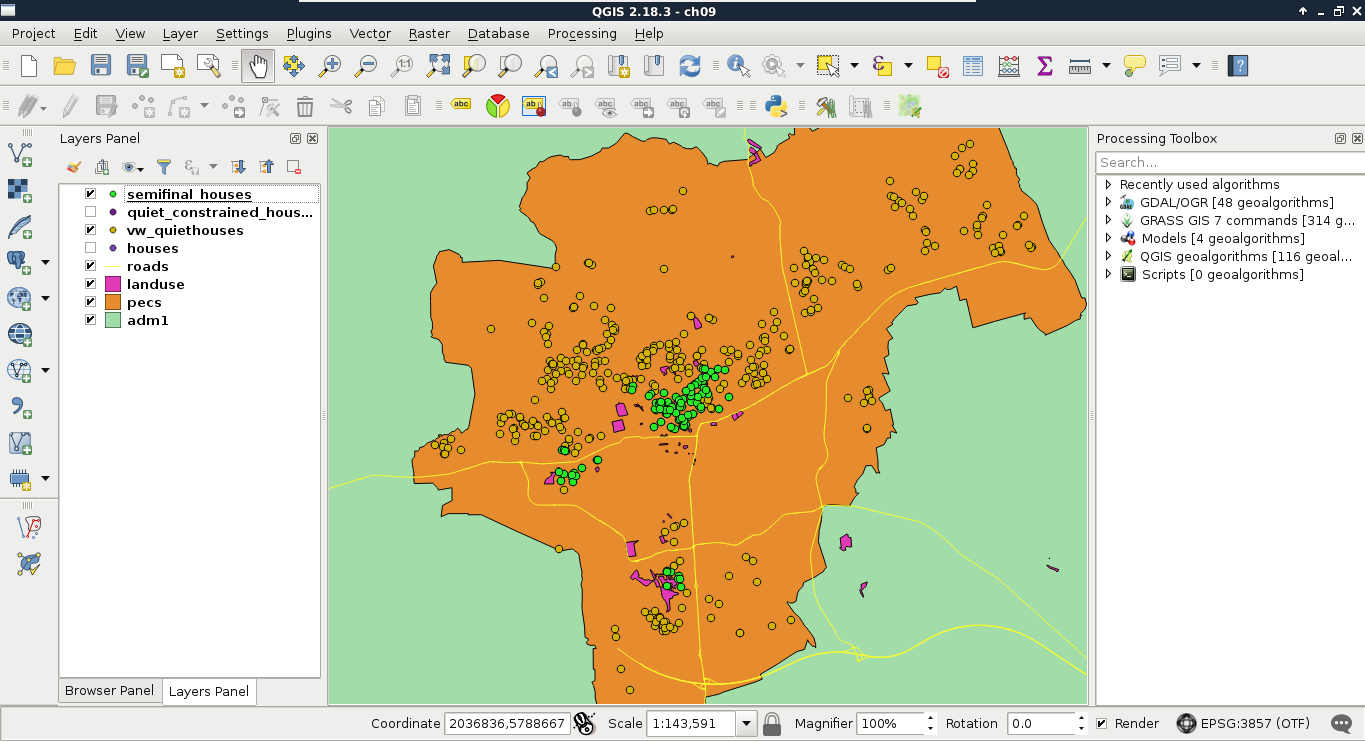

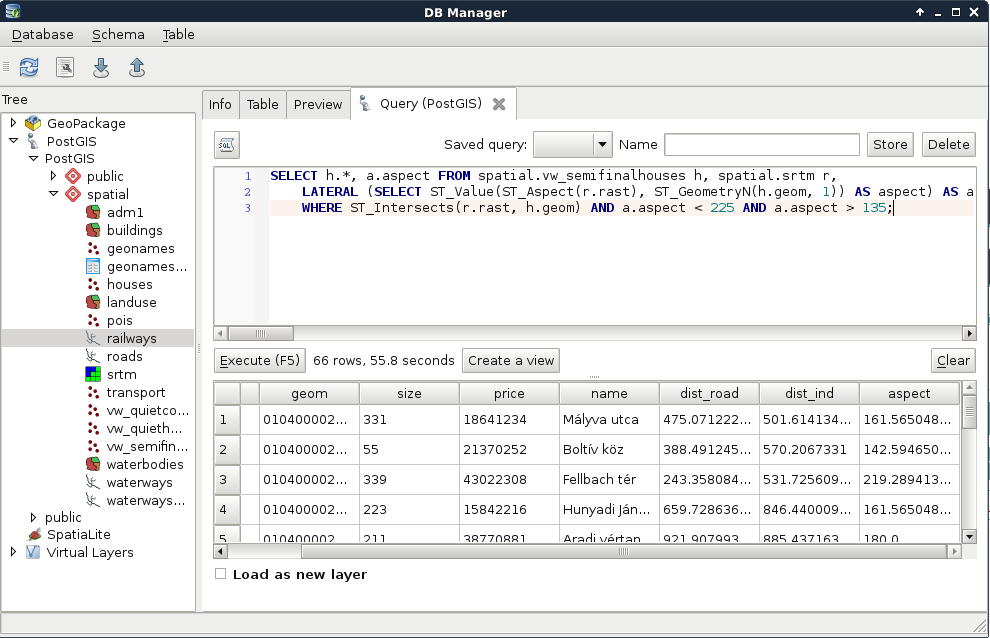

Chapter 9, Spatial Analysis on Steroids - Using PostGIS, reiterates the example of the previous chapter, but entirely in PostGIS. It shows how a good software choice for the given task can enhance productivity by minimizing manual labor and automating the entire workflow. It also introduces you to the world of PostGIS spatial functions by going through the analysis again.

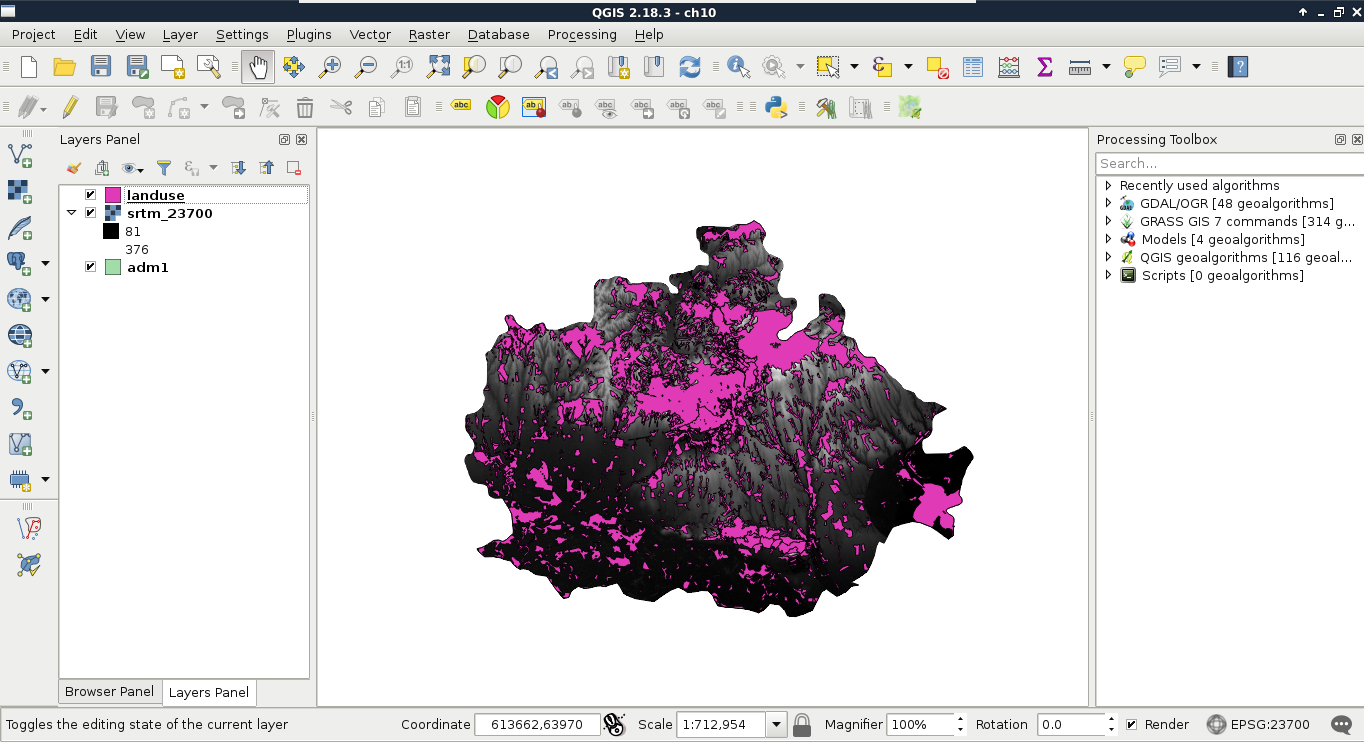

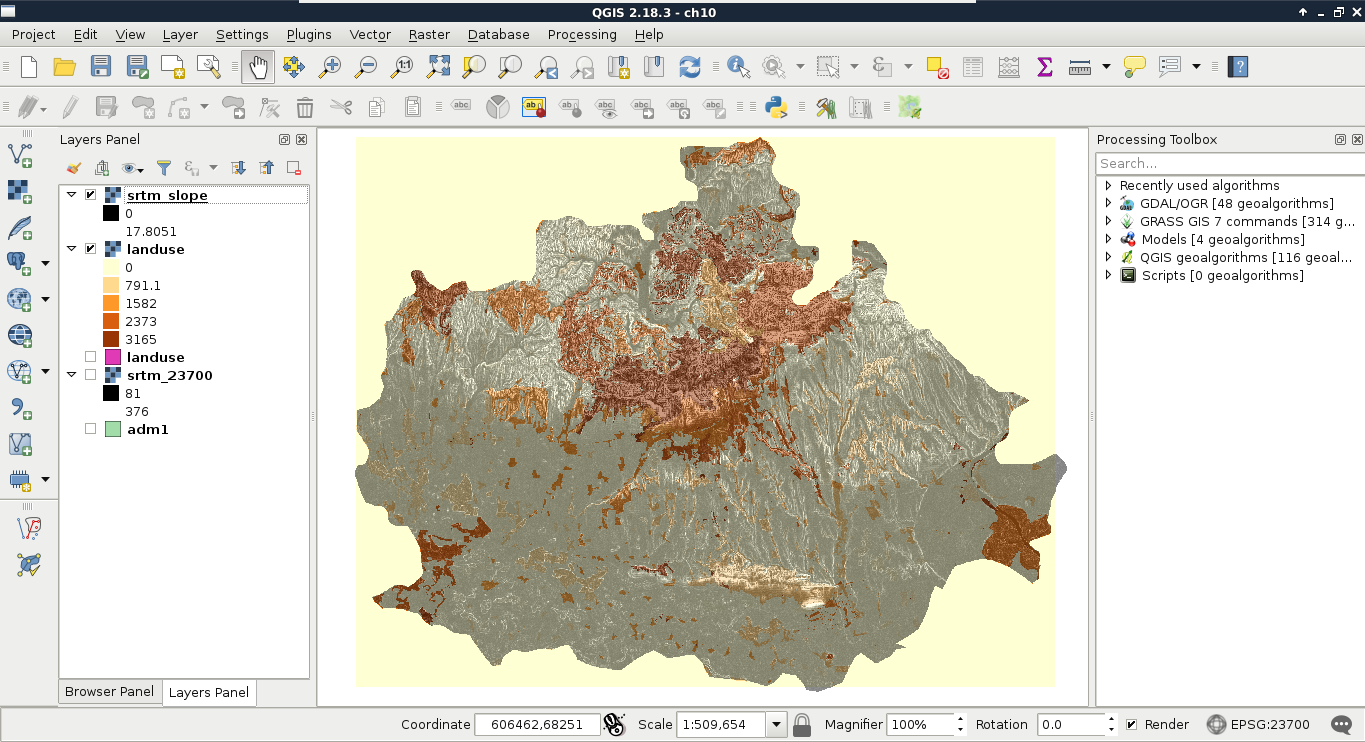

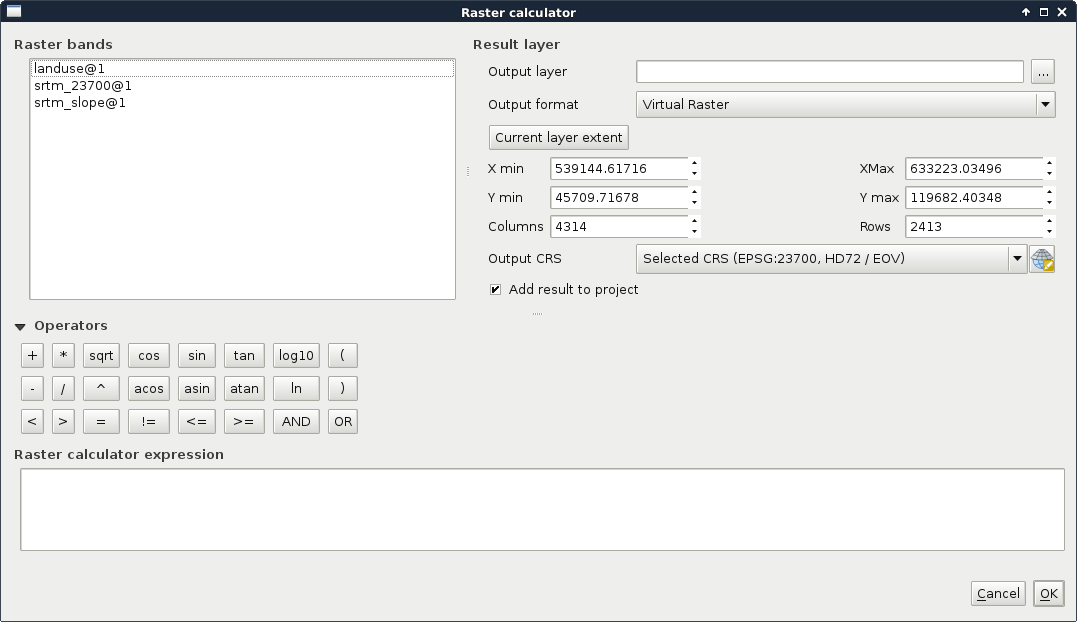

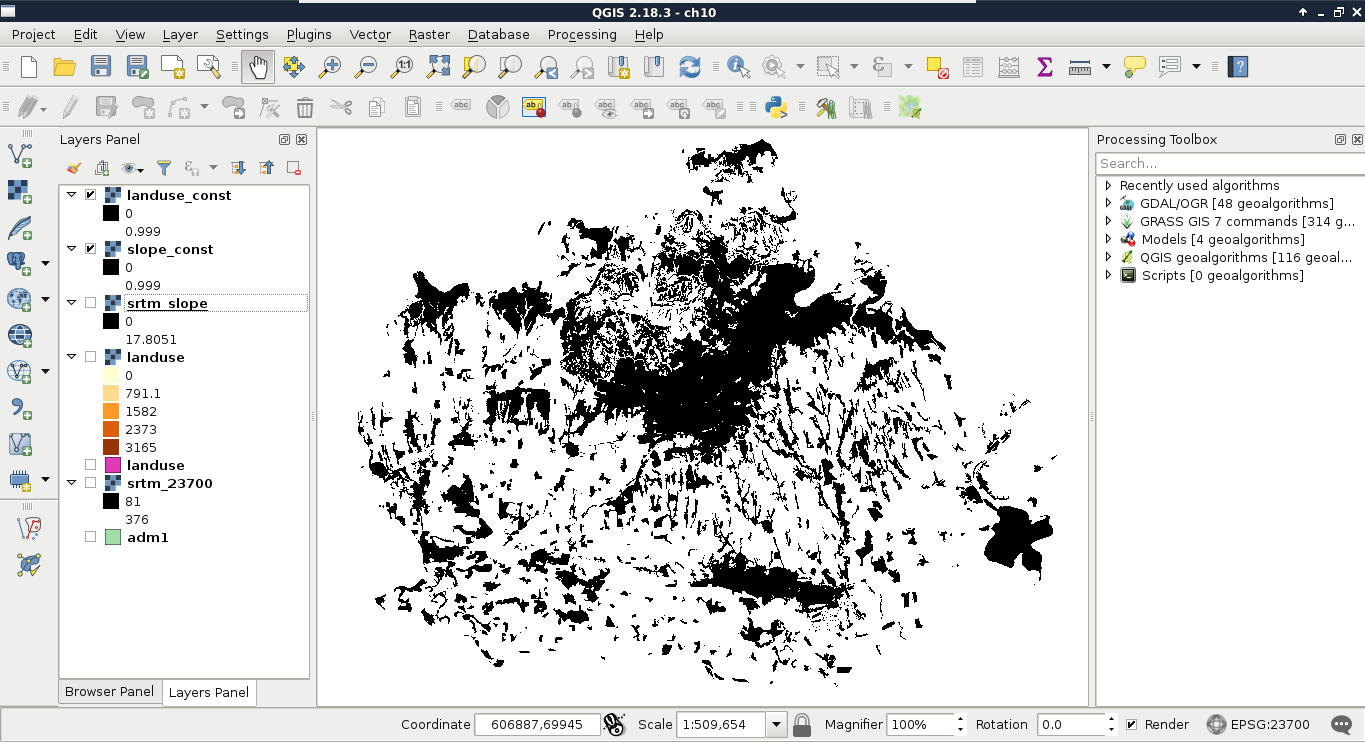

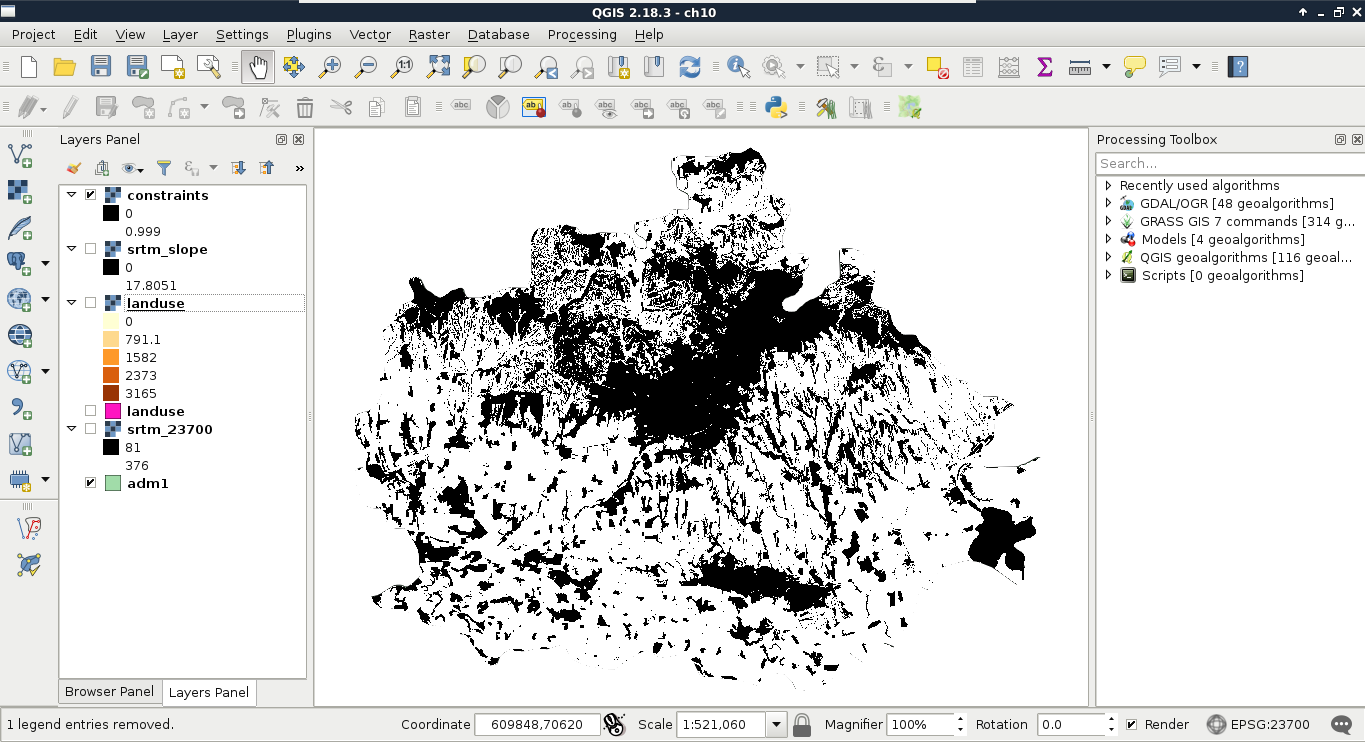

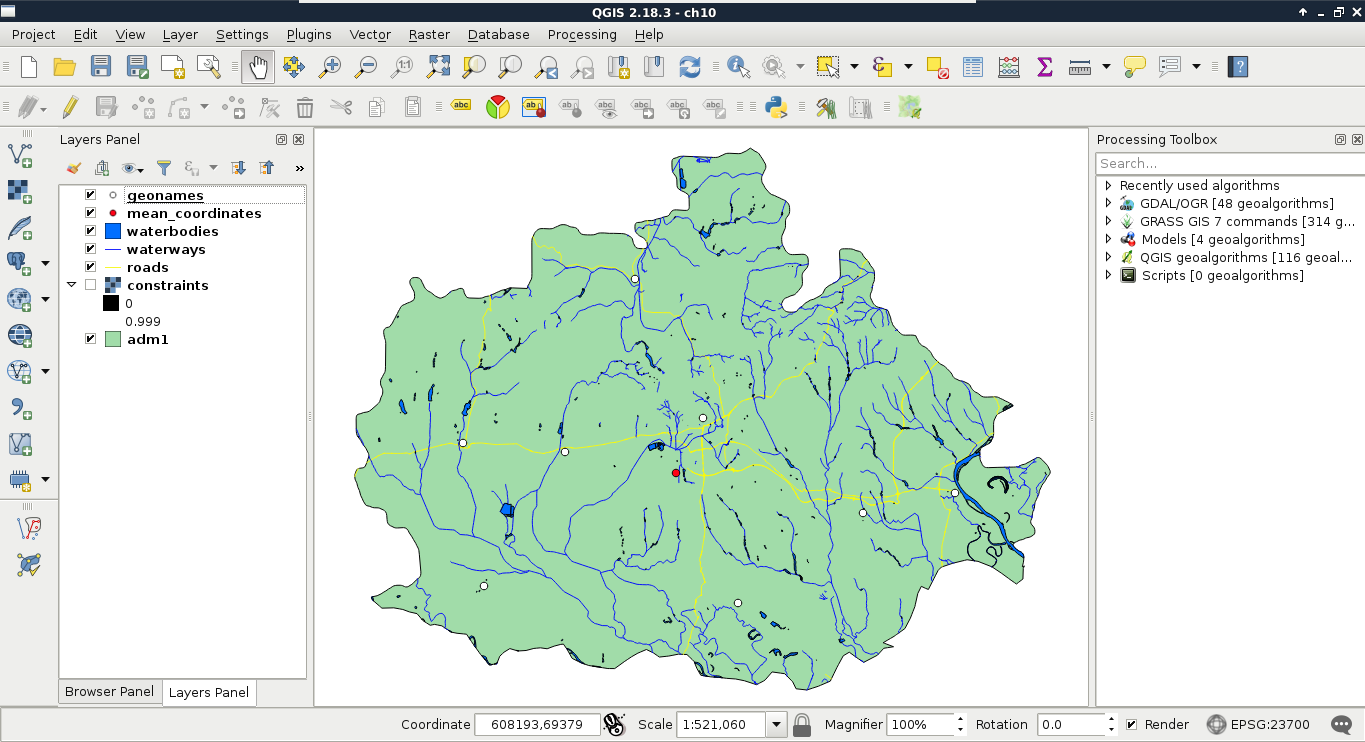

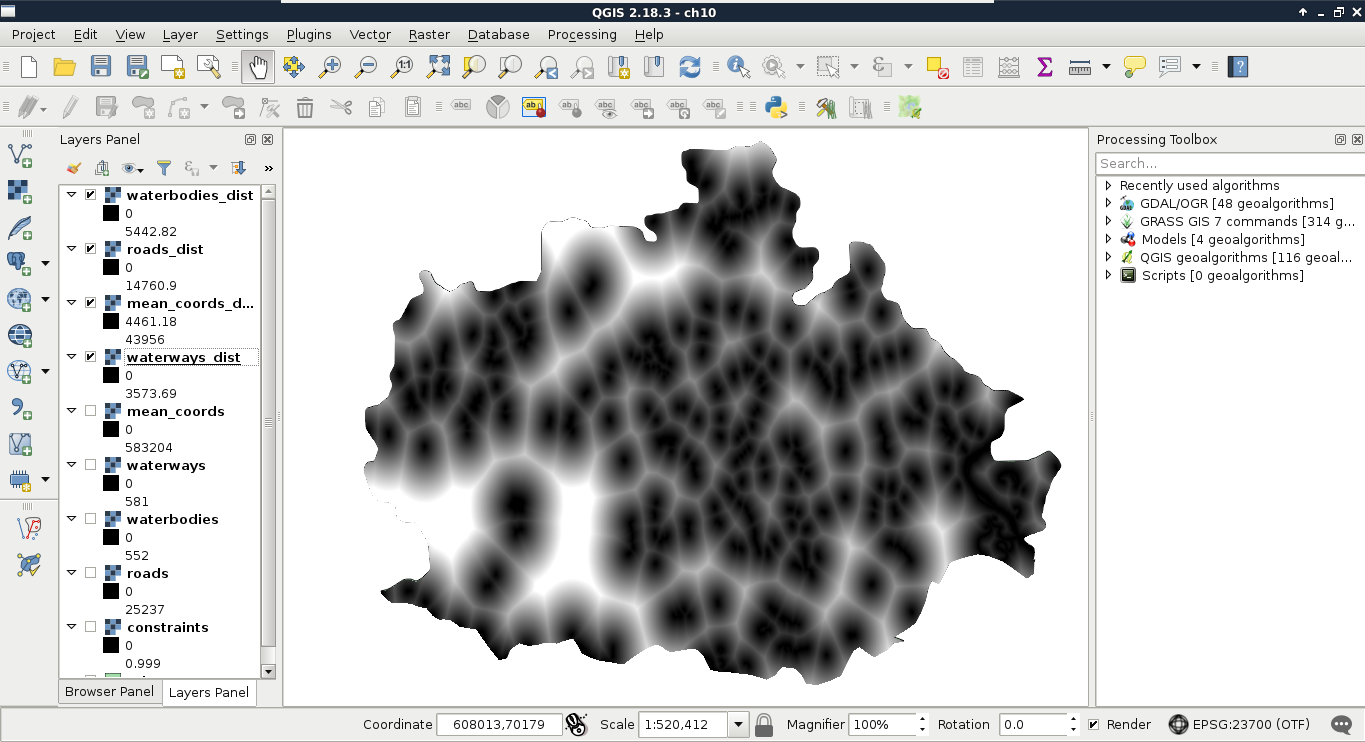

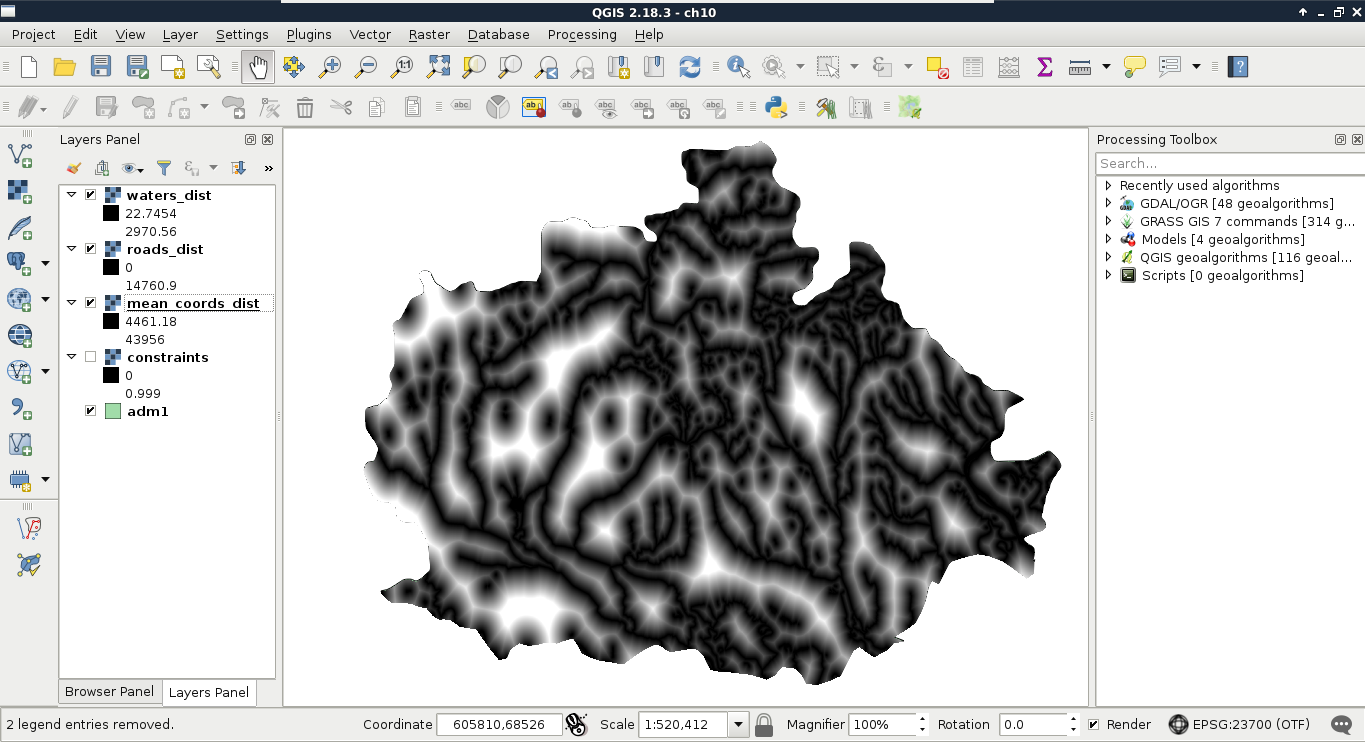

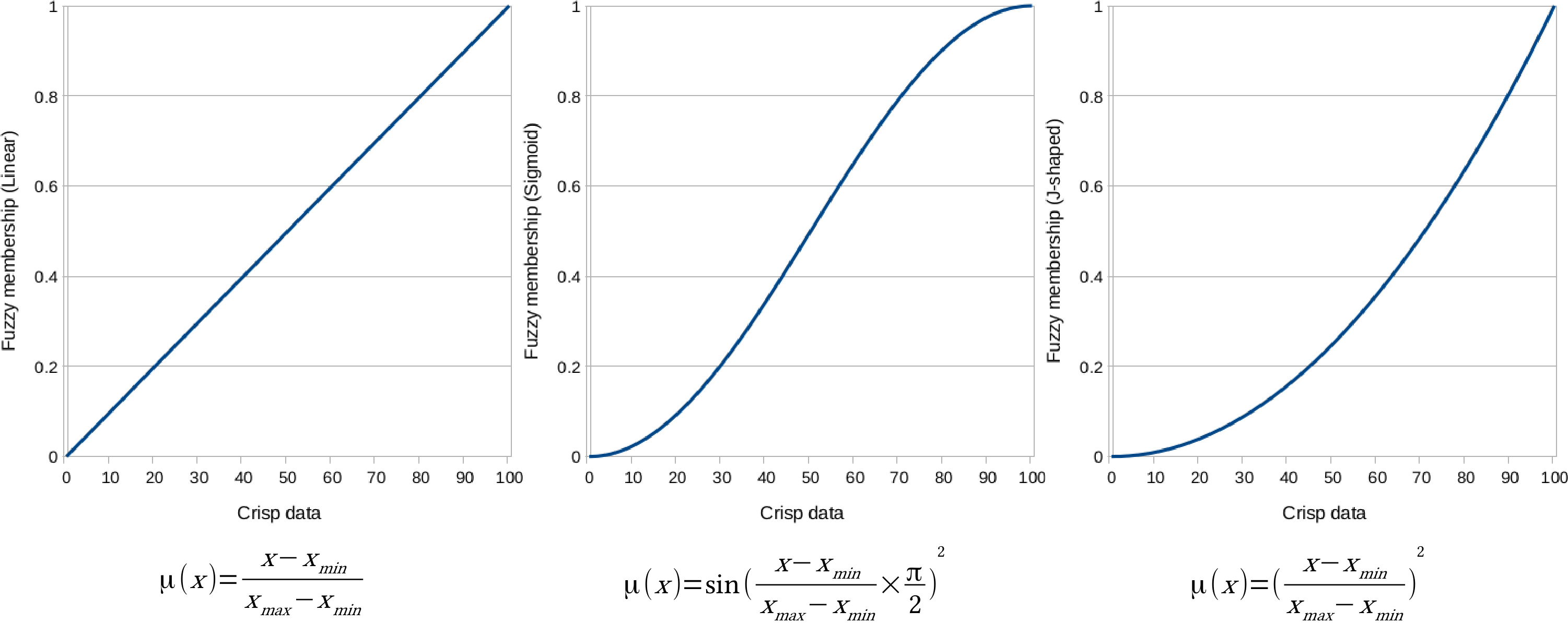

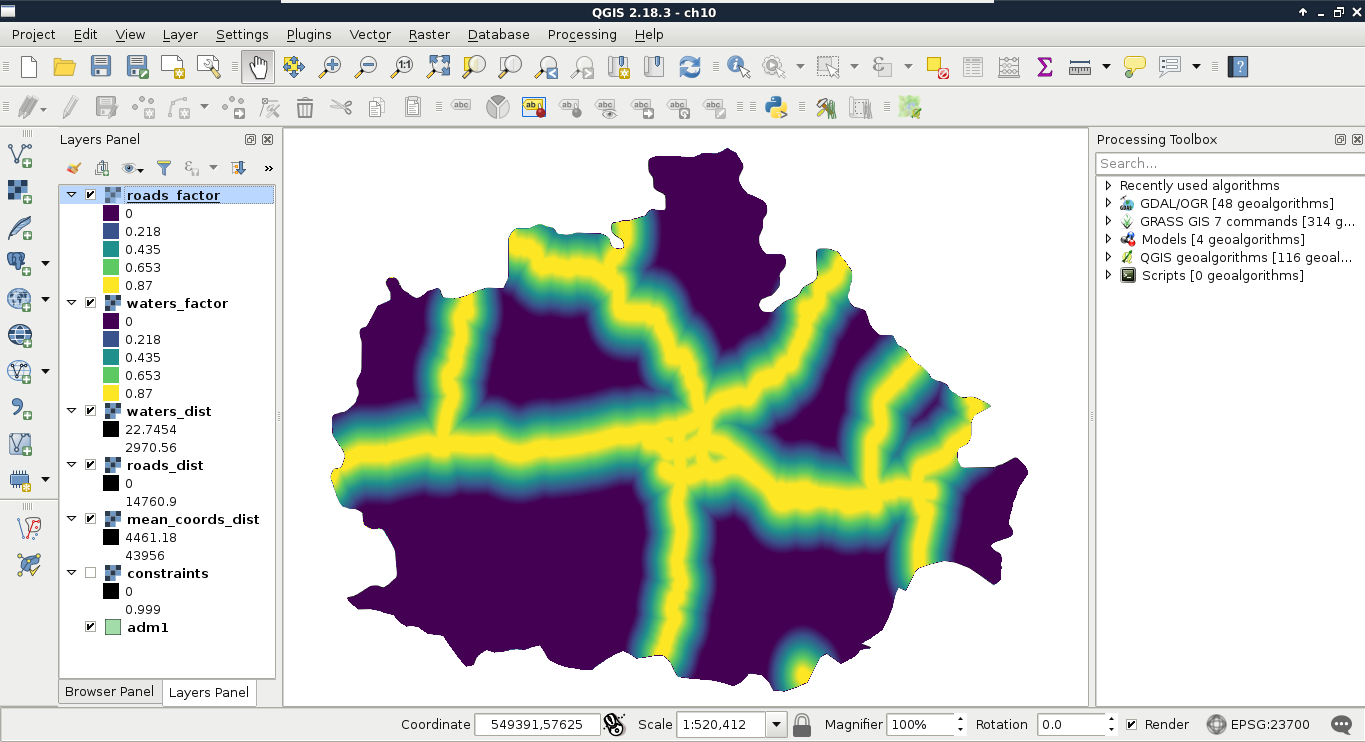

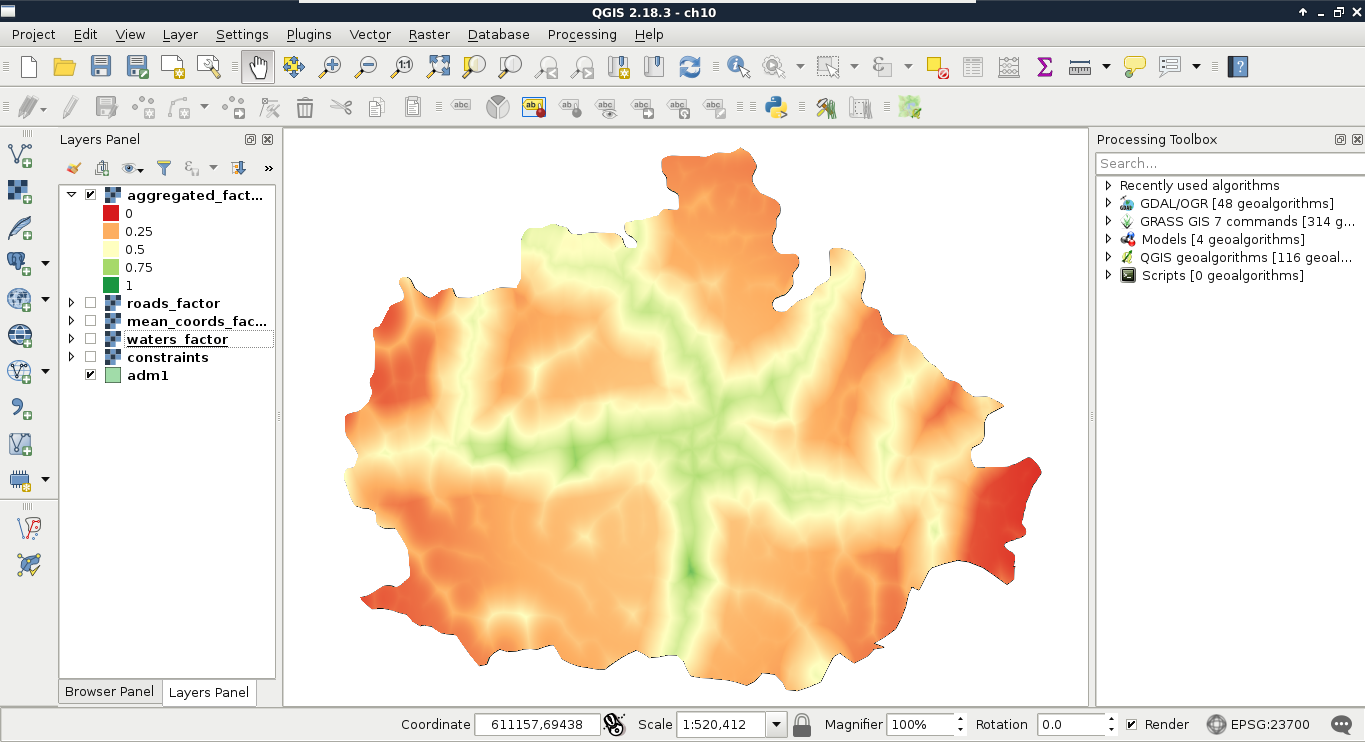

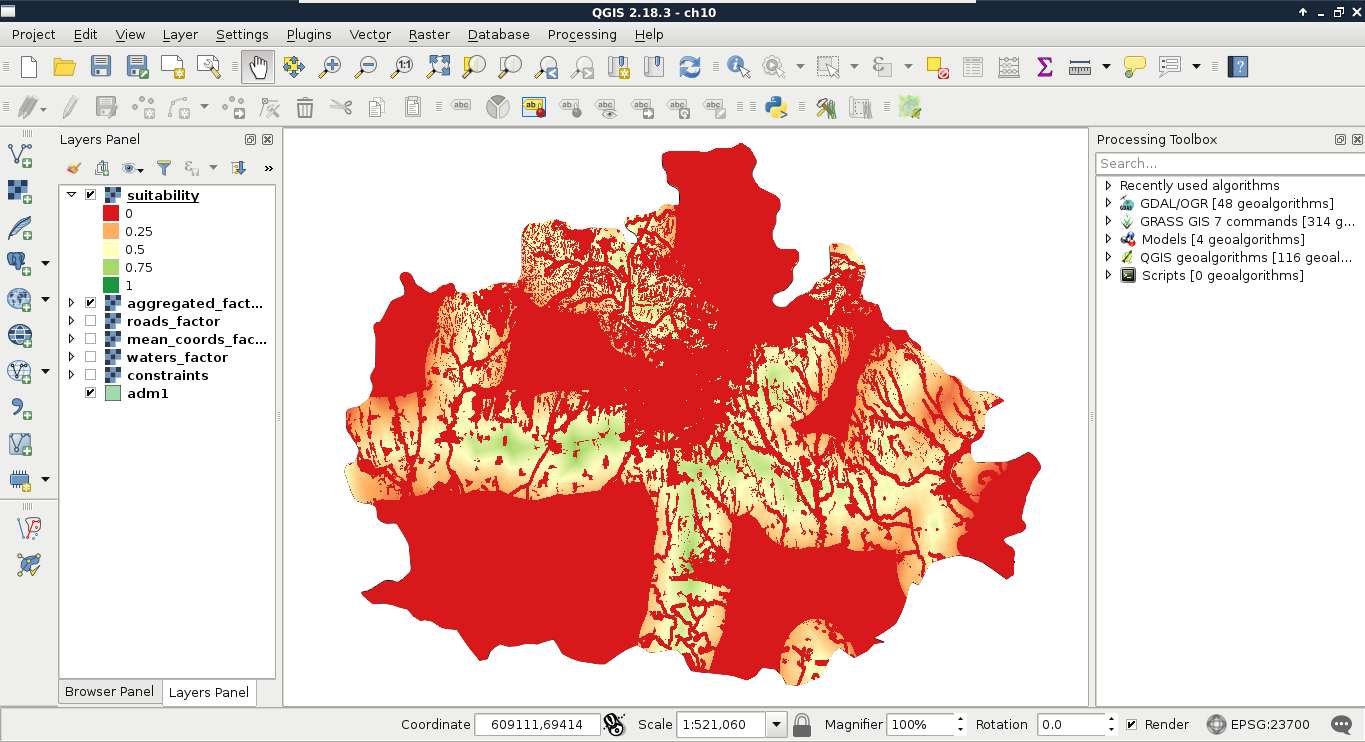

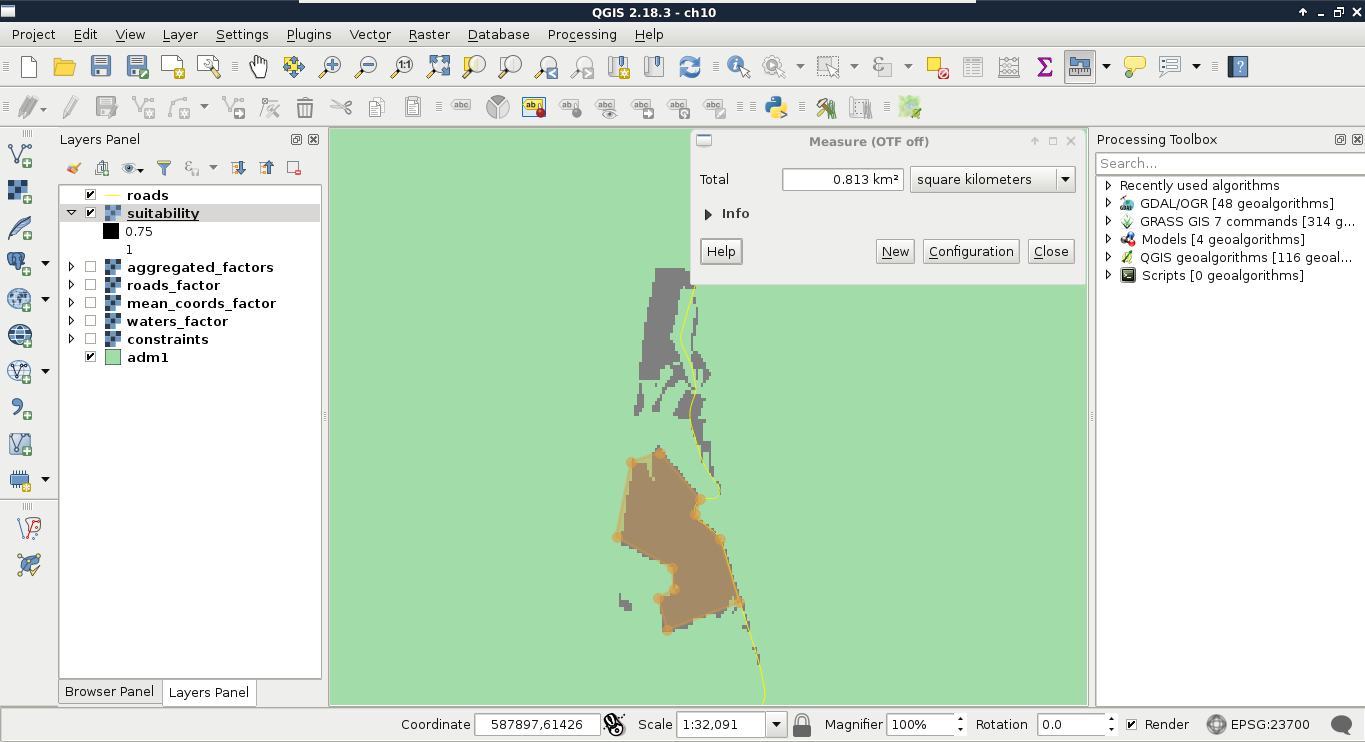

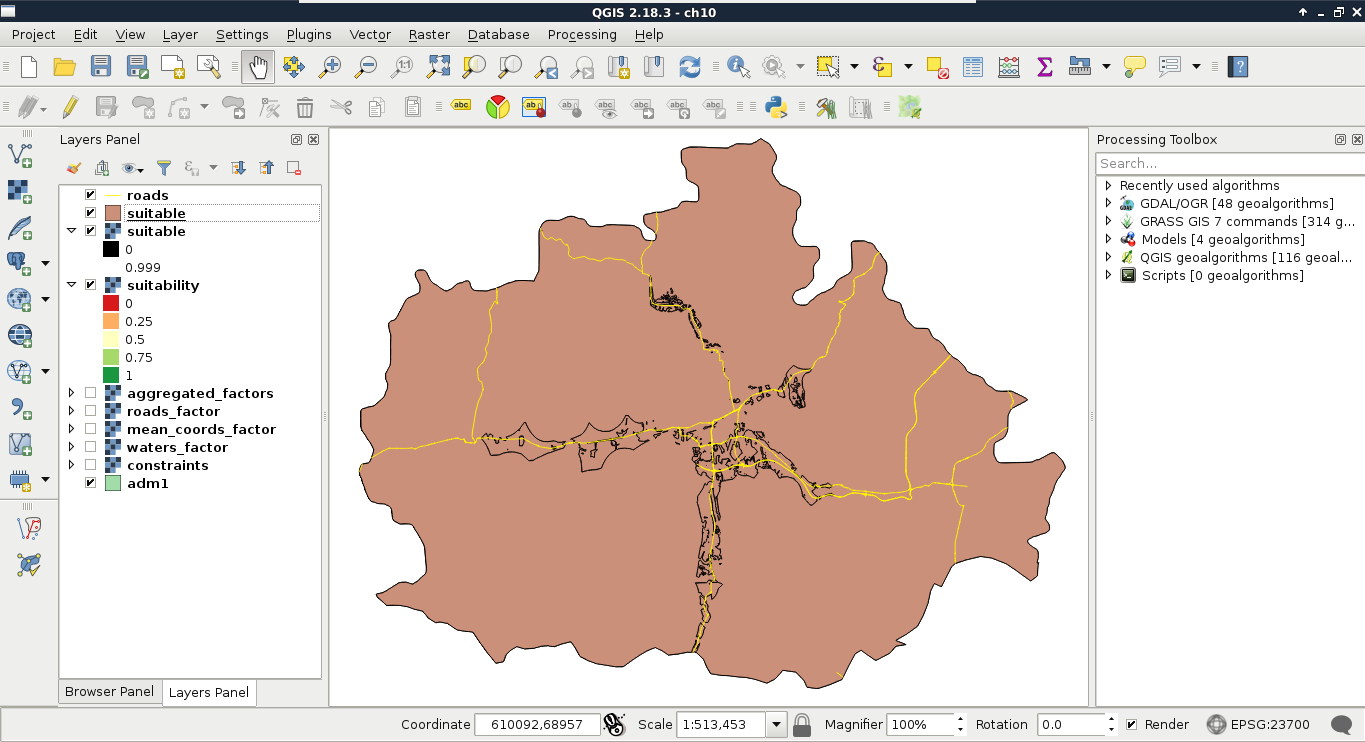

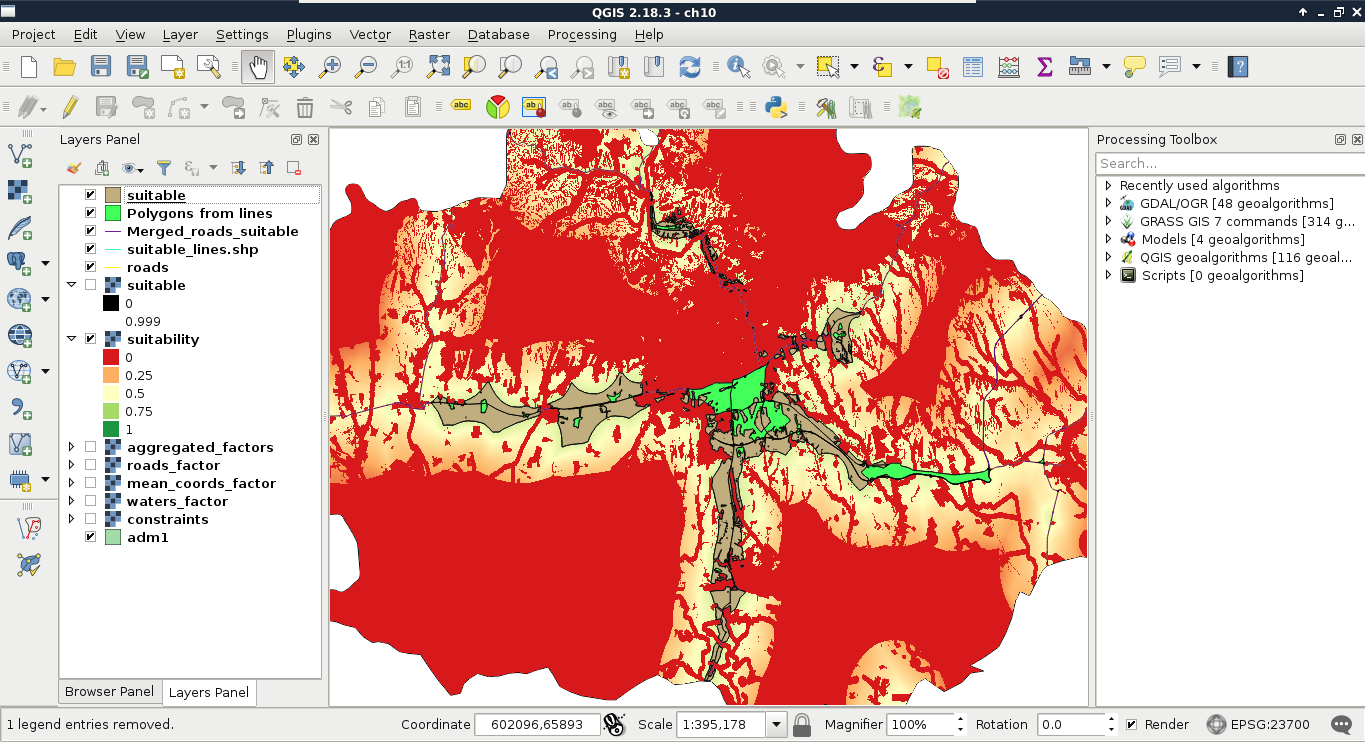

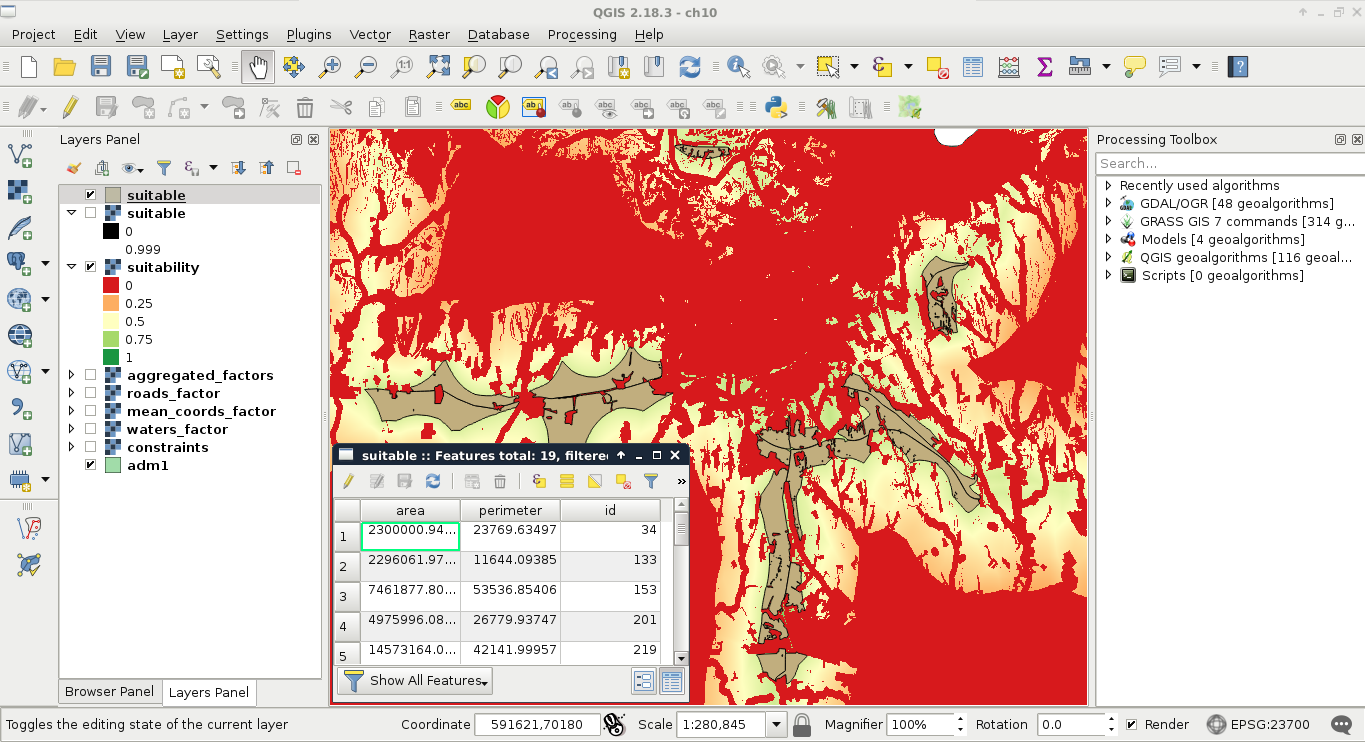

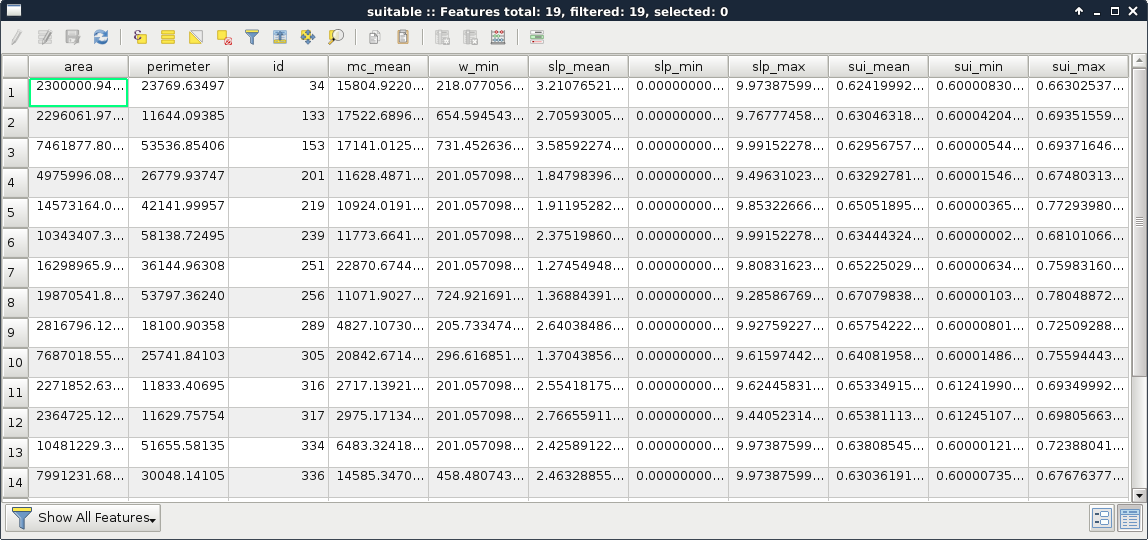

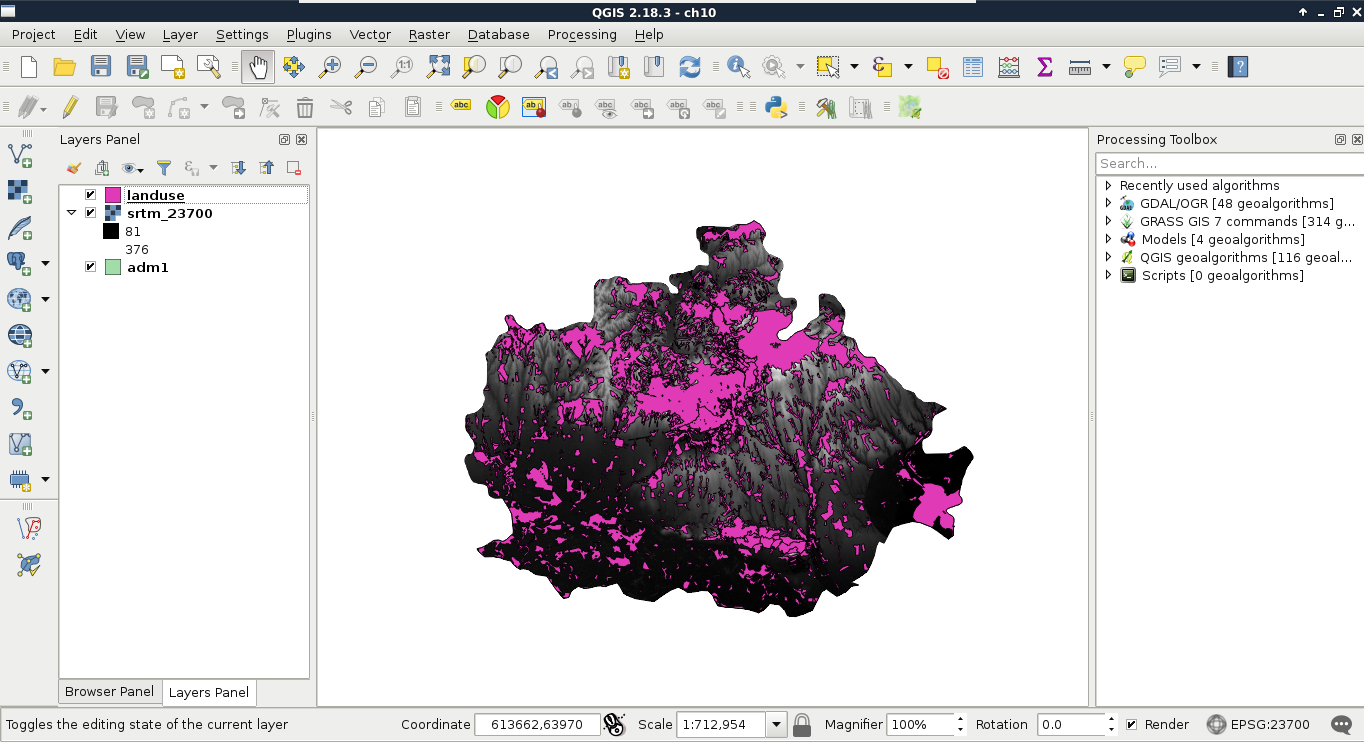

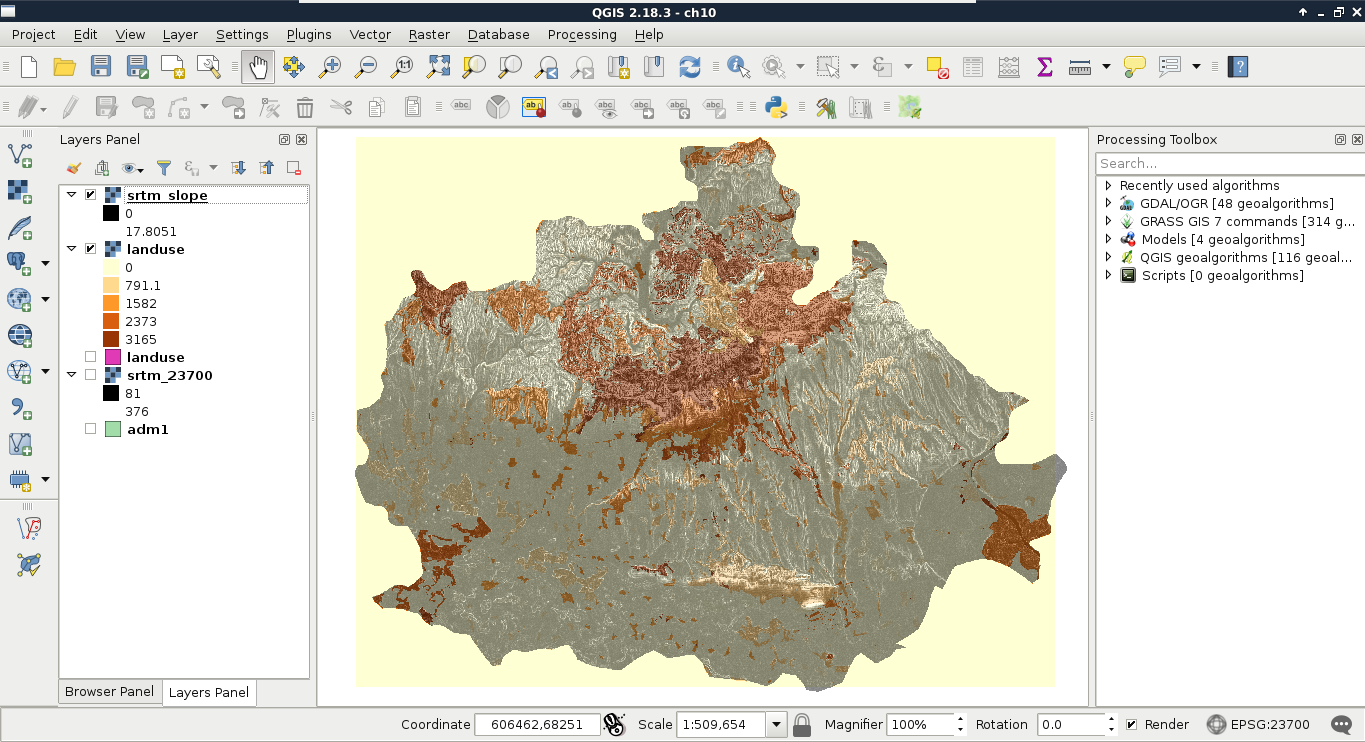

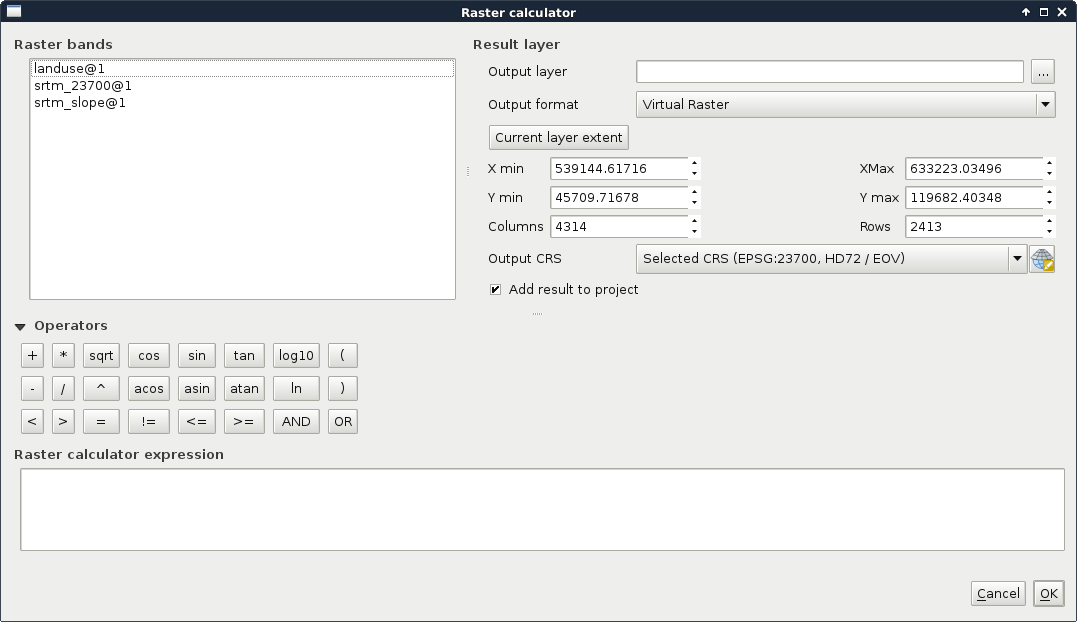

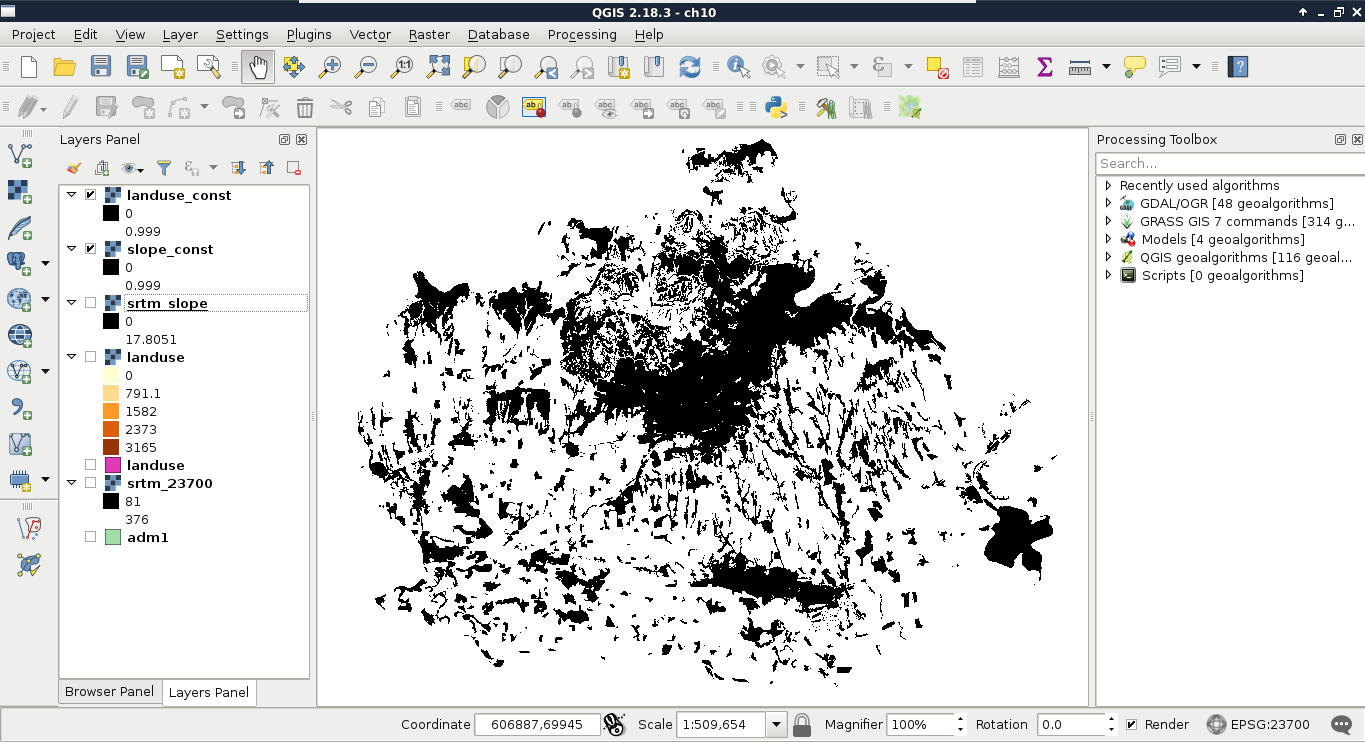

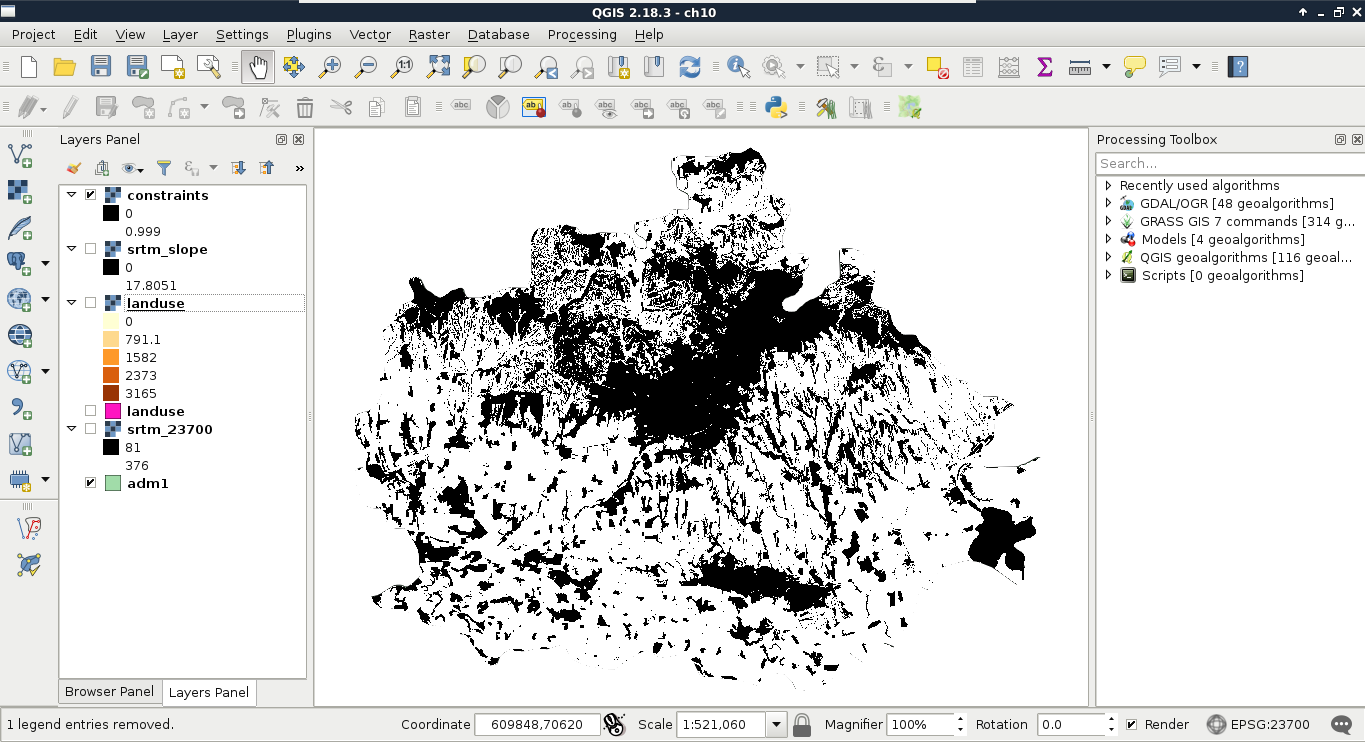

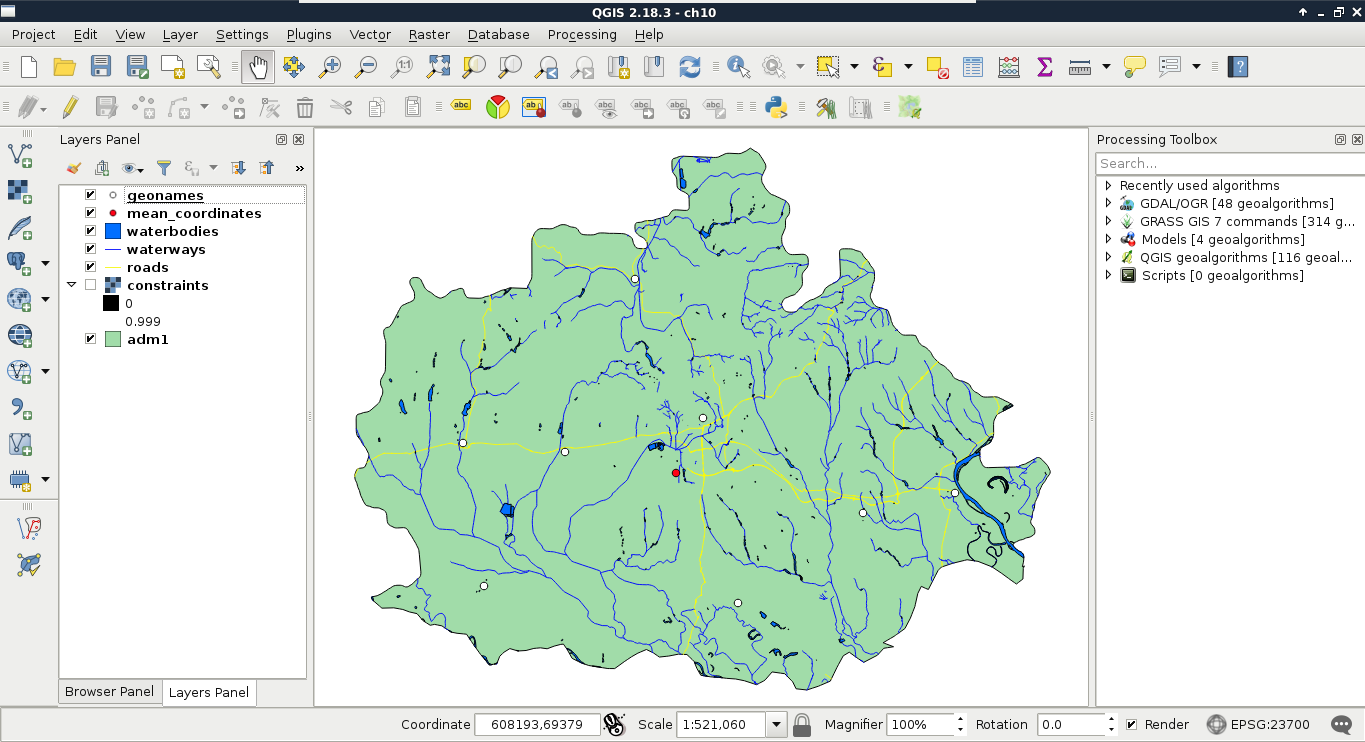

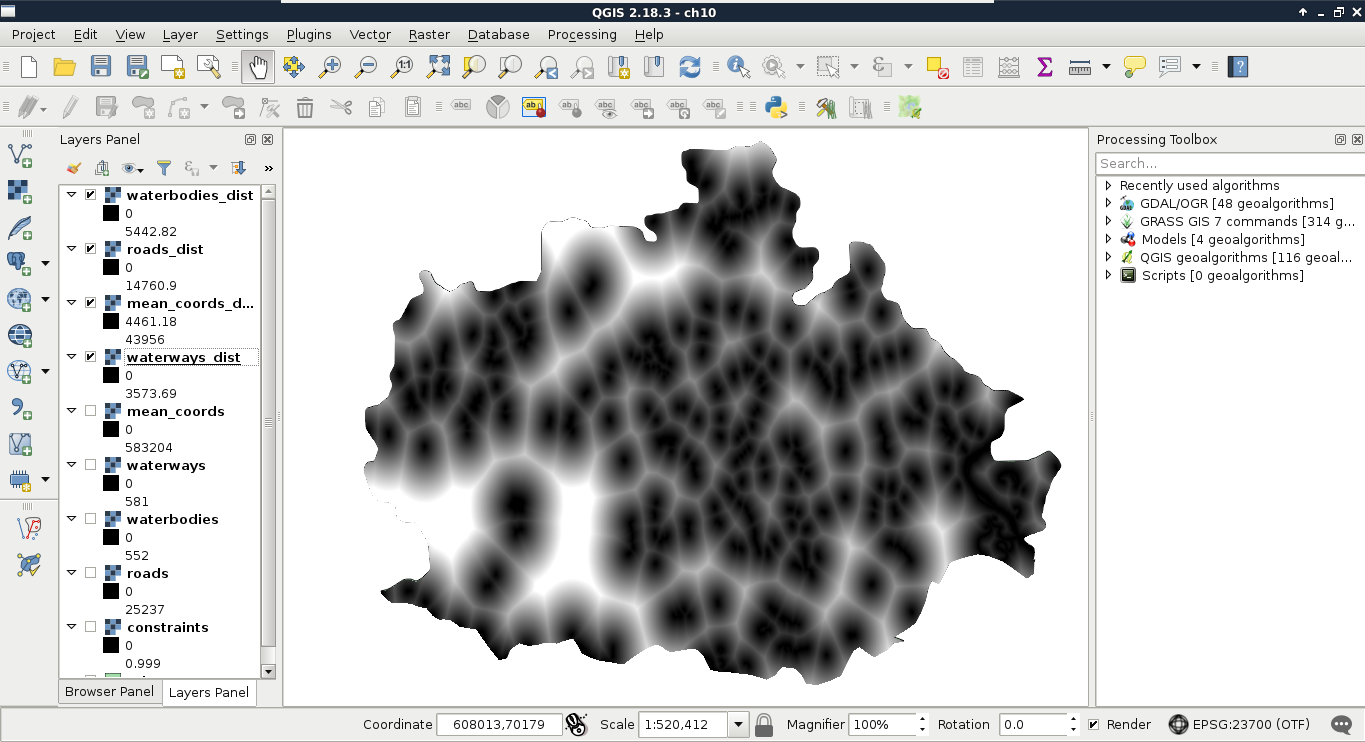

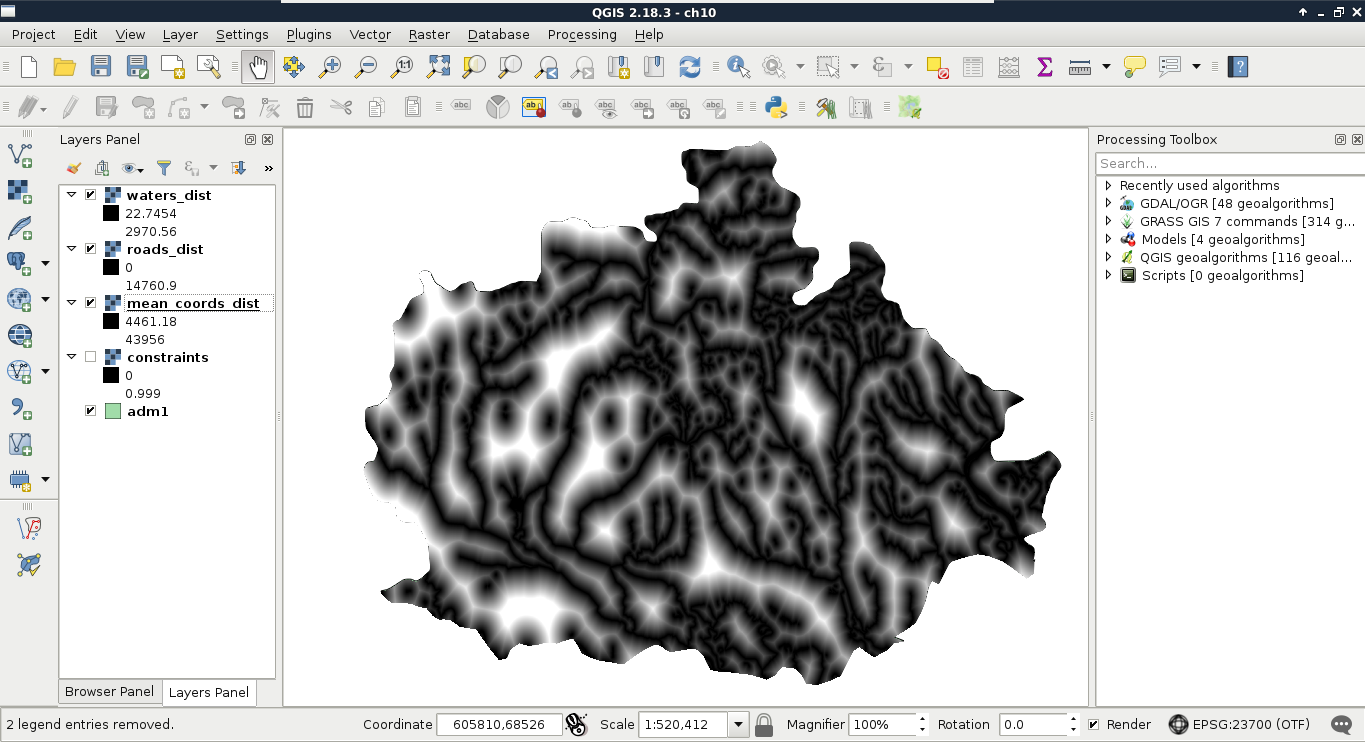

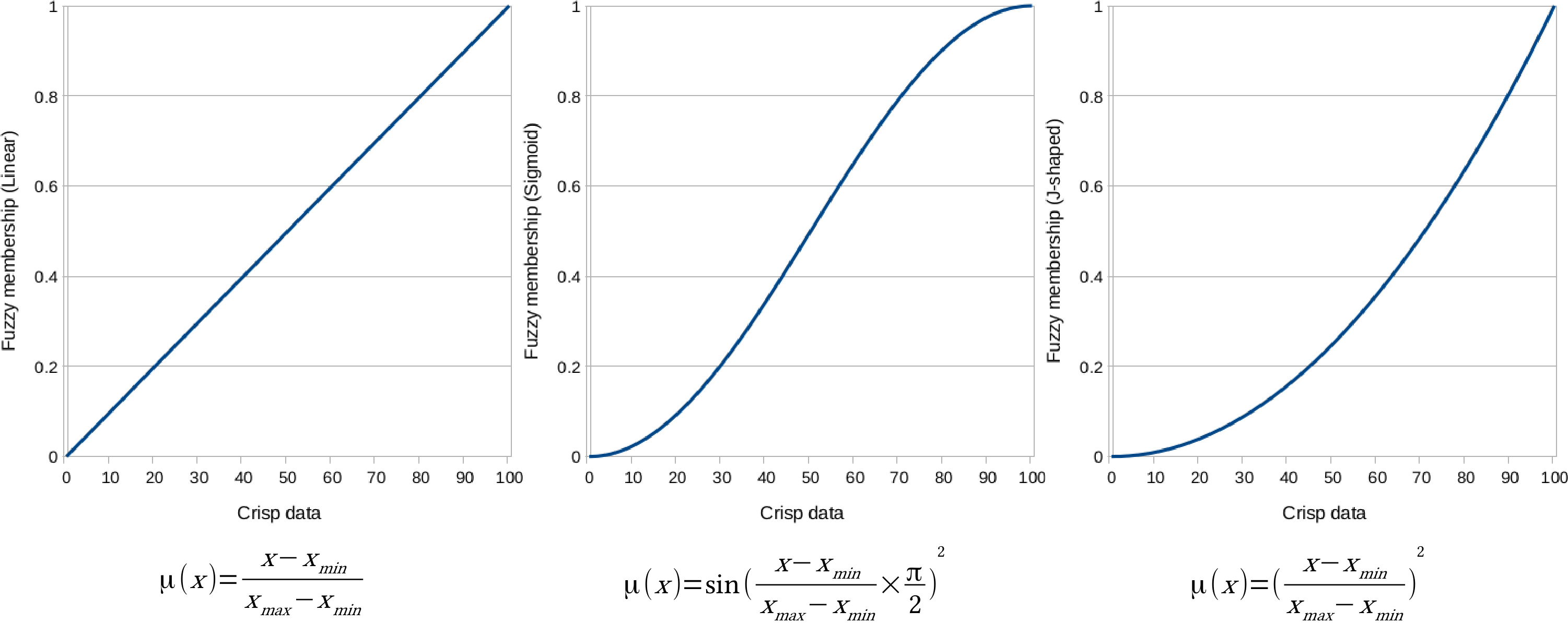

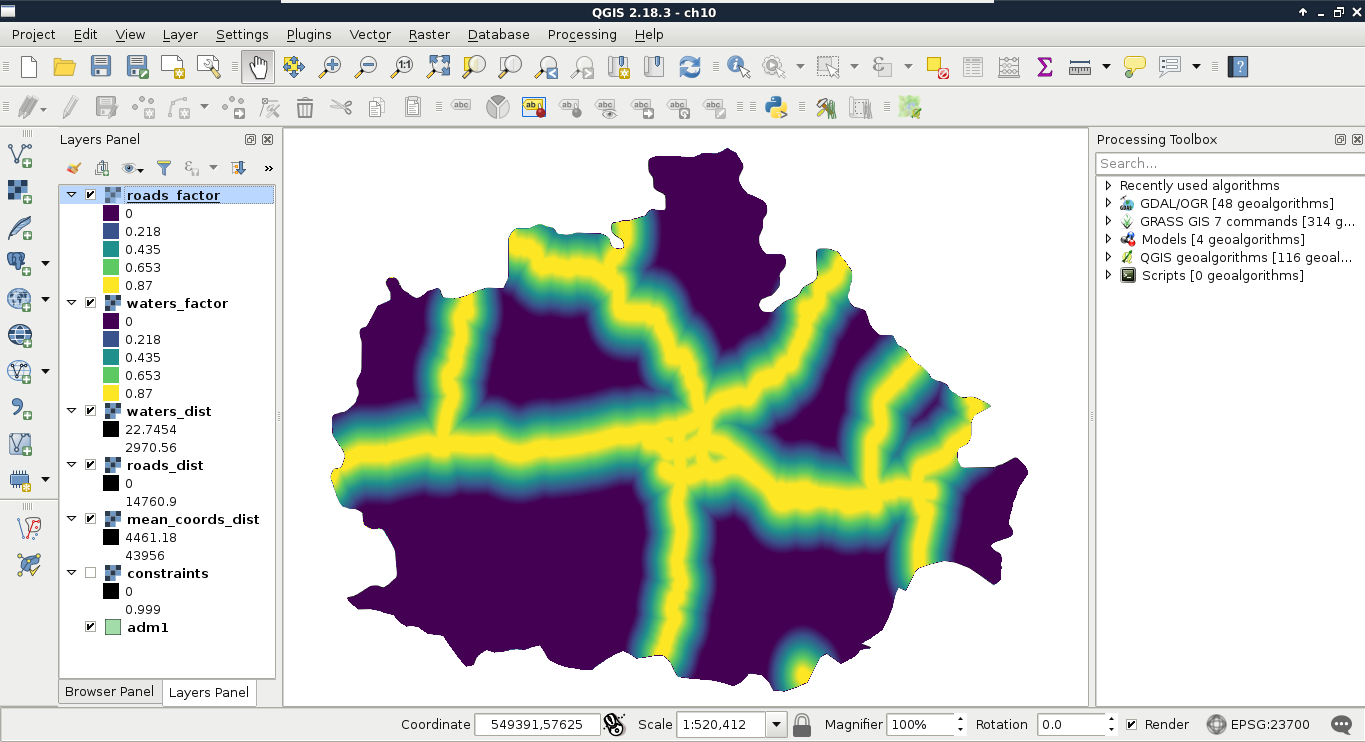

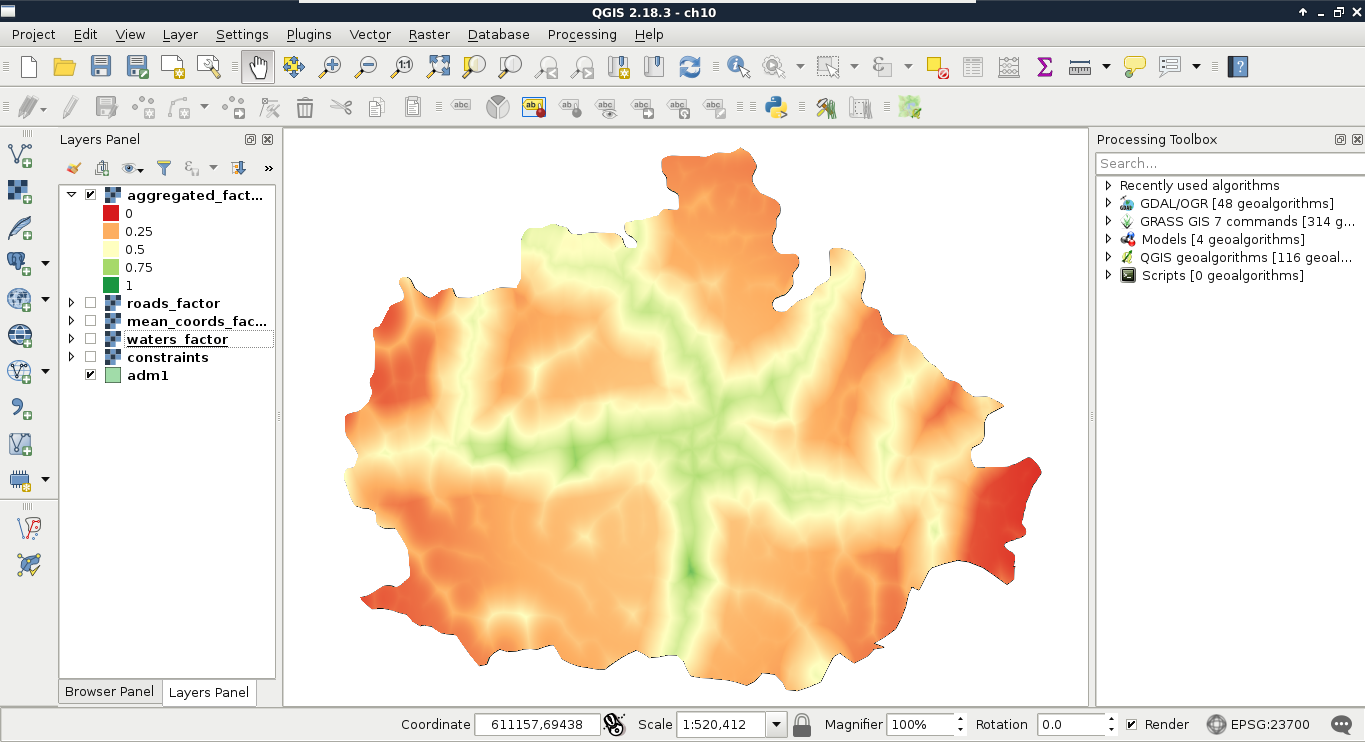

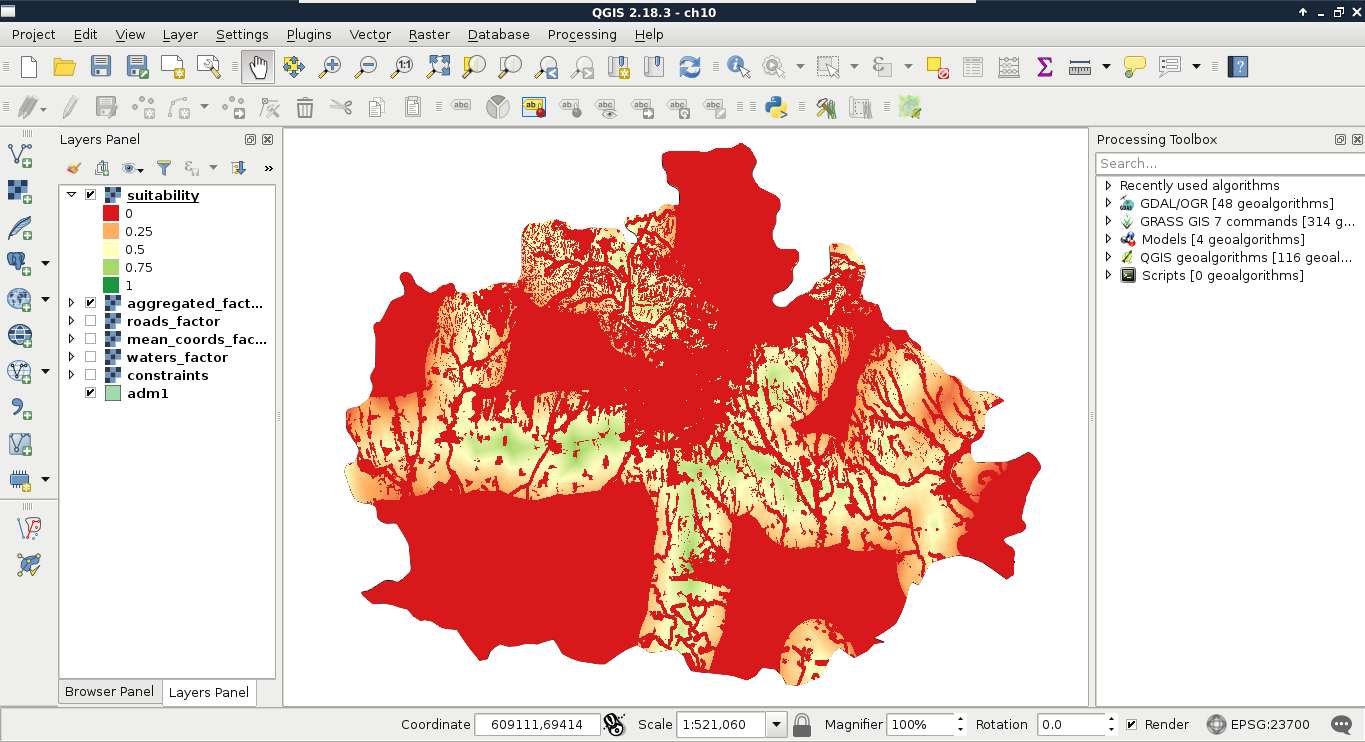

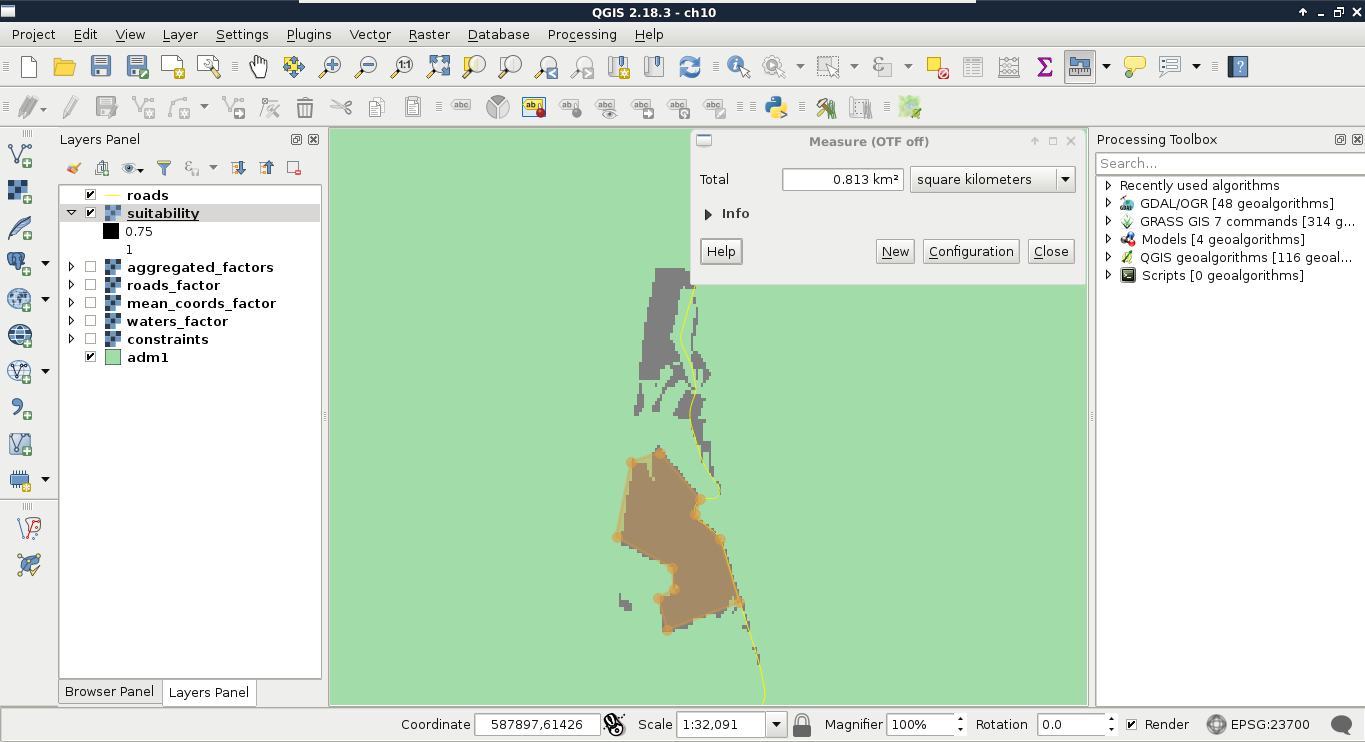

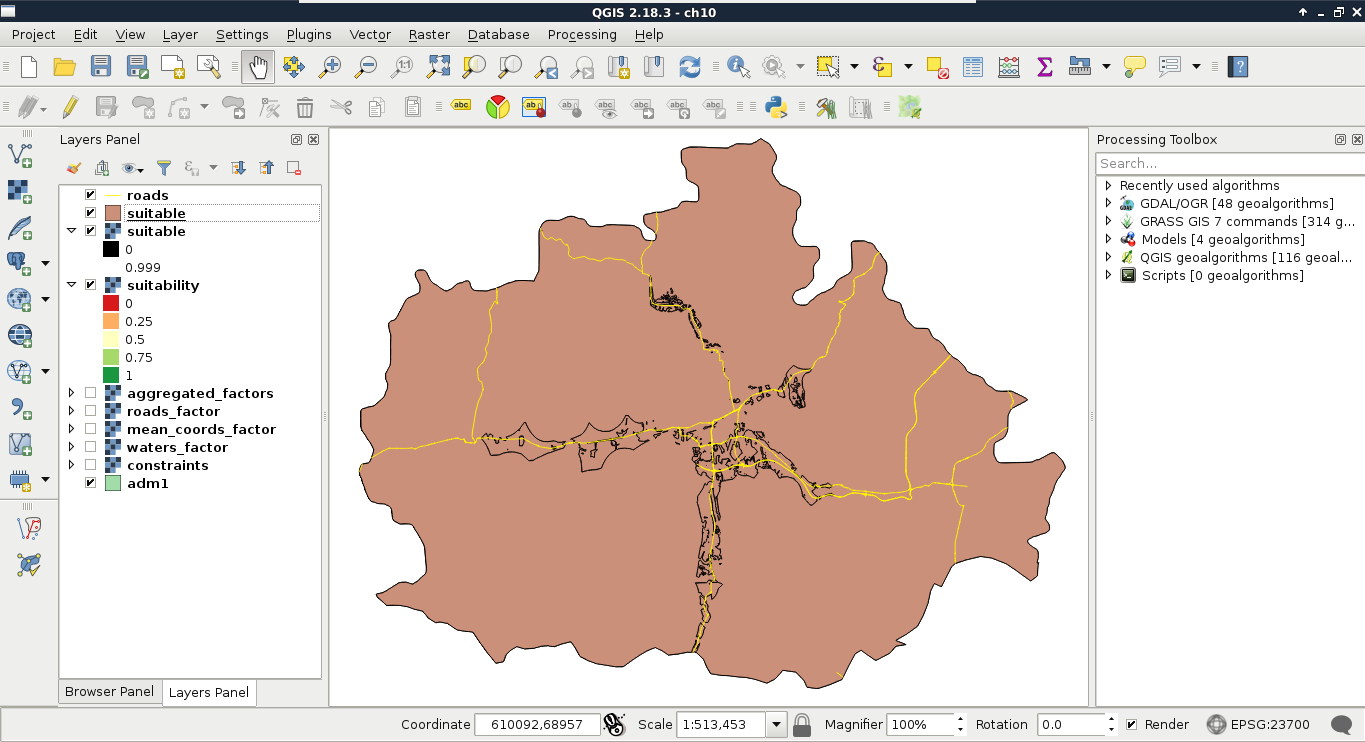

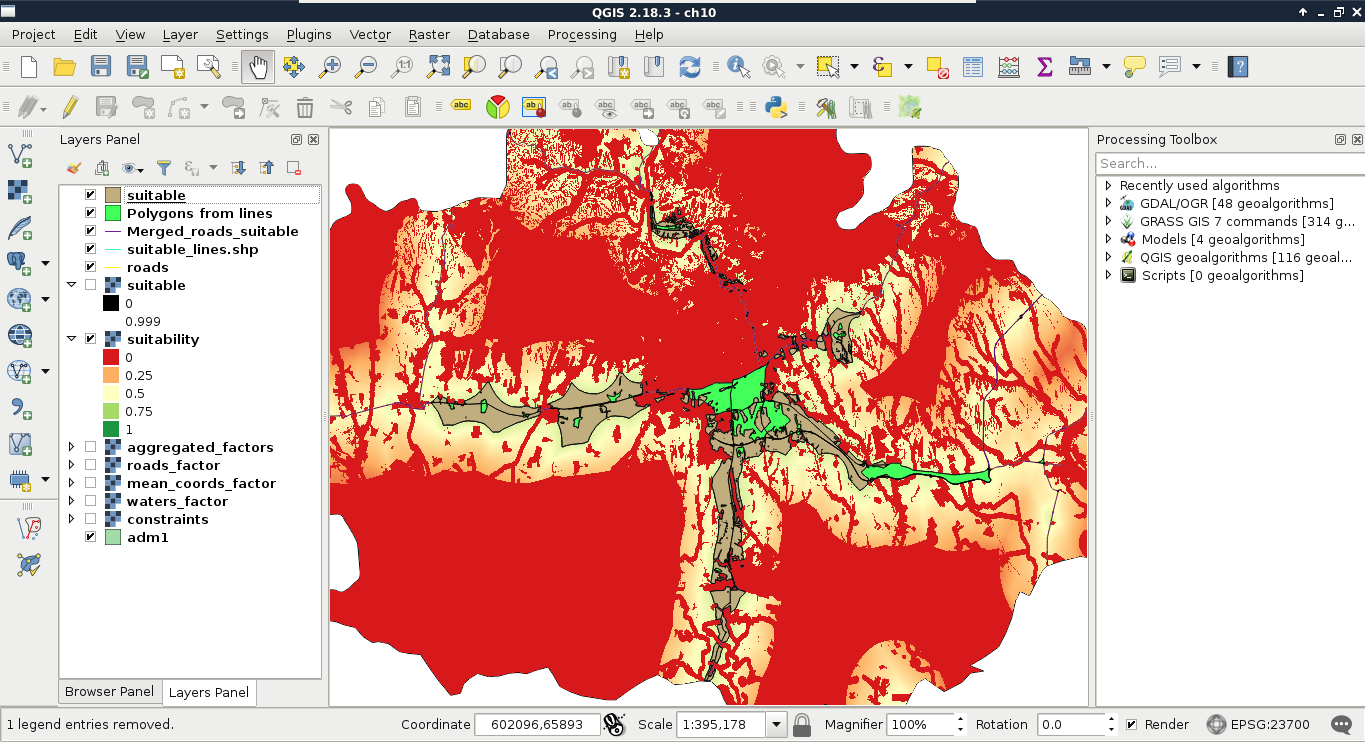

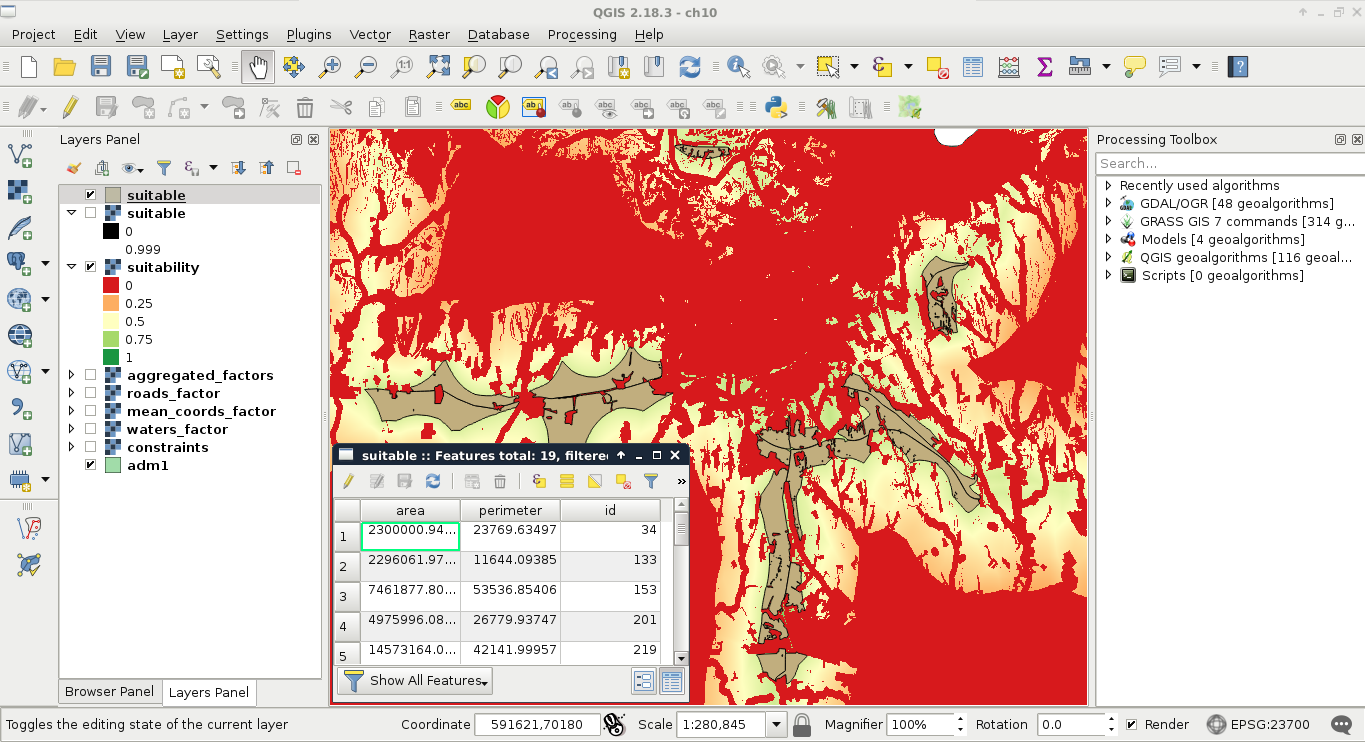

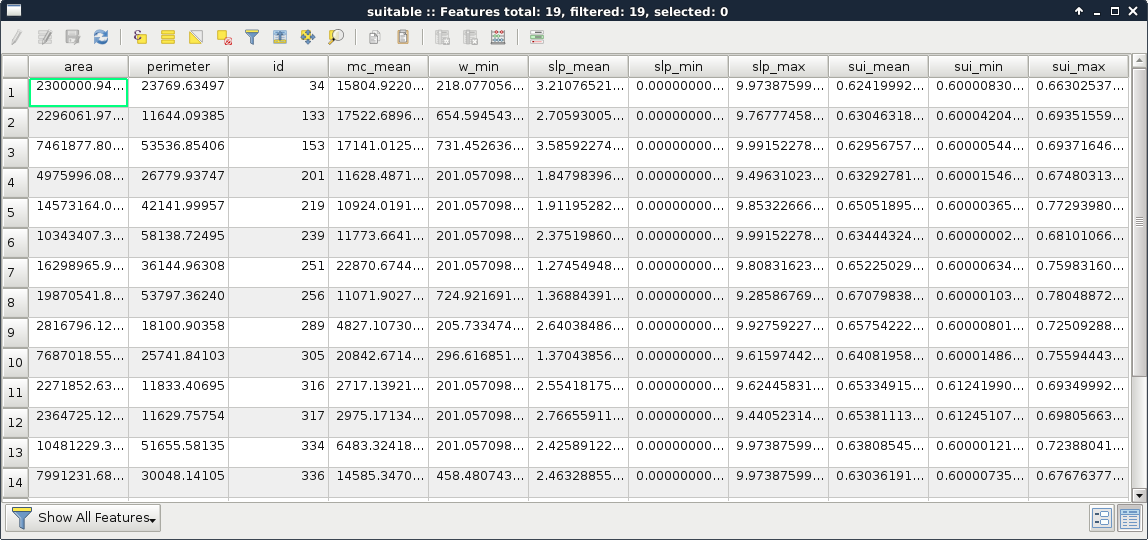

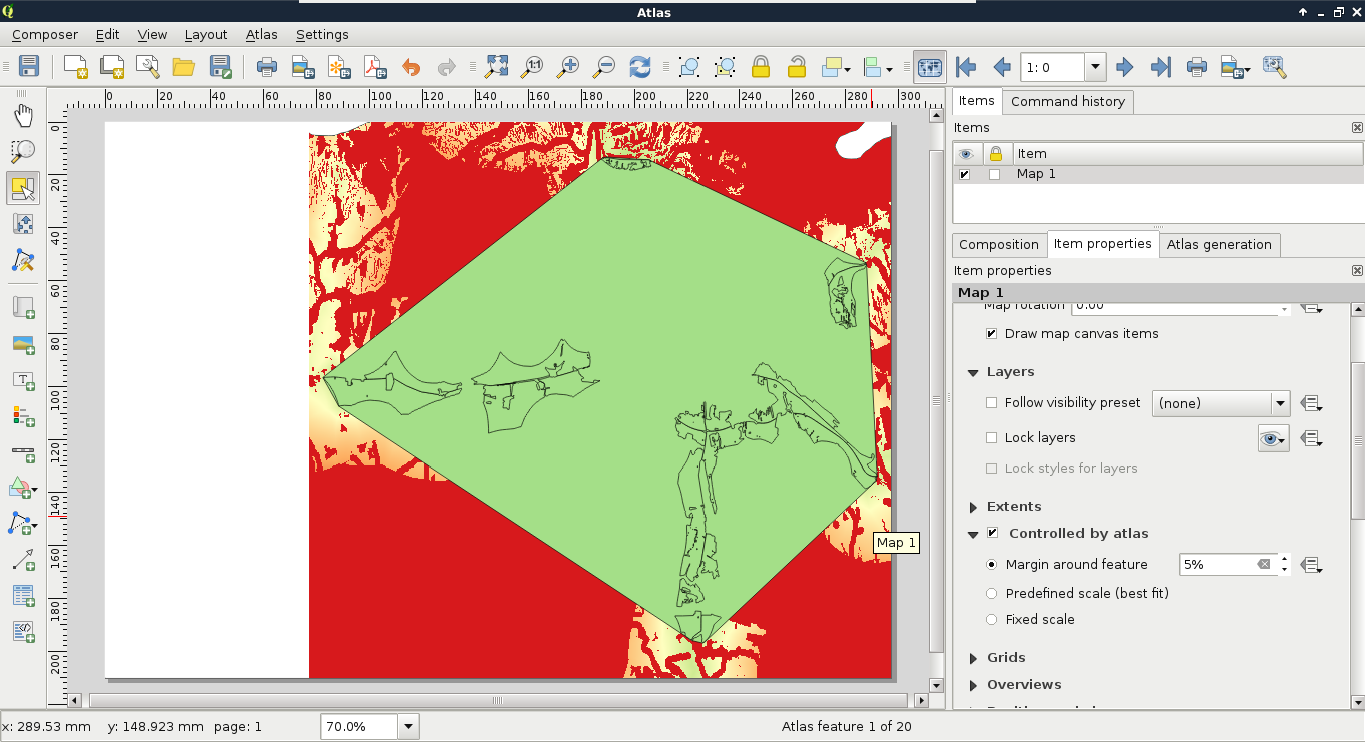

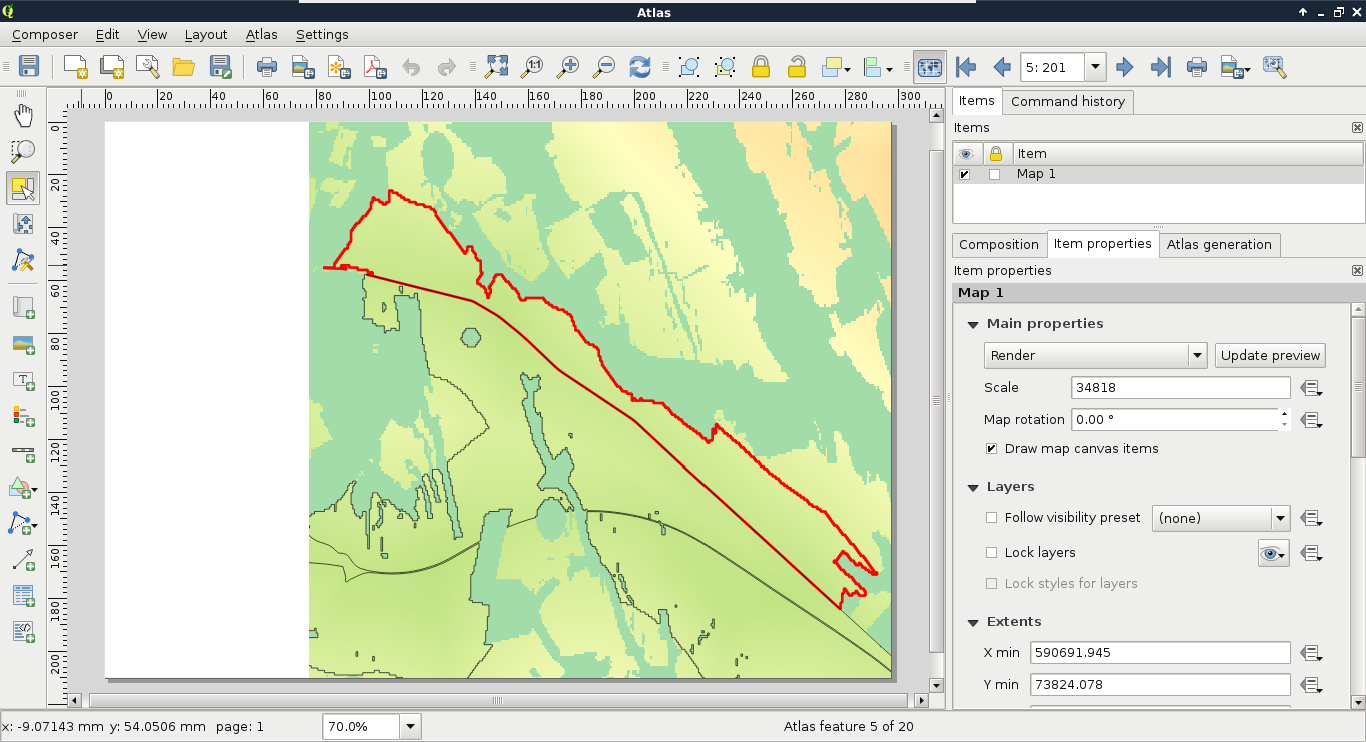

Chapter 10, A Typical GIS Problem, shows raster analysis, where spatial databases do not excel. It discusses typical raster operations by going through a decision making process. It sheds light on typical considerations related to the raster data model during an analysis, while also introducing some powerful tools and valuable methodology required to make a good decision based on spatial factors and constraints.

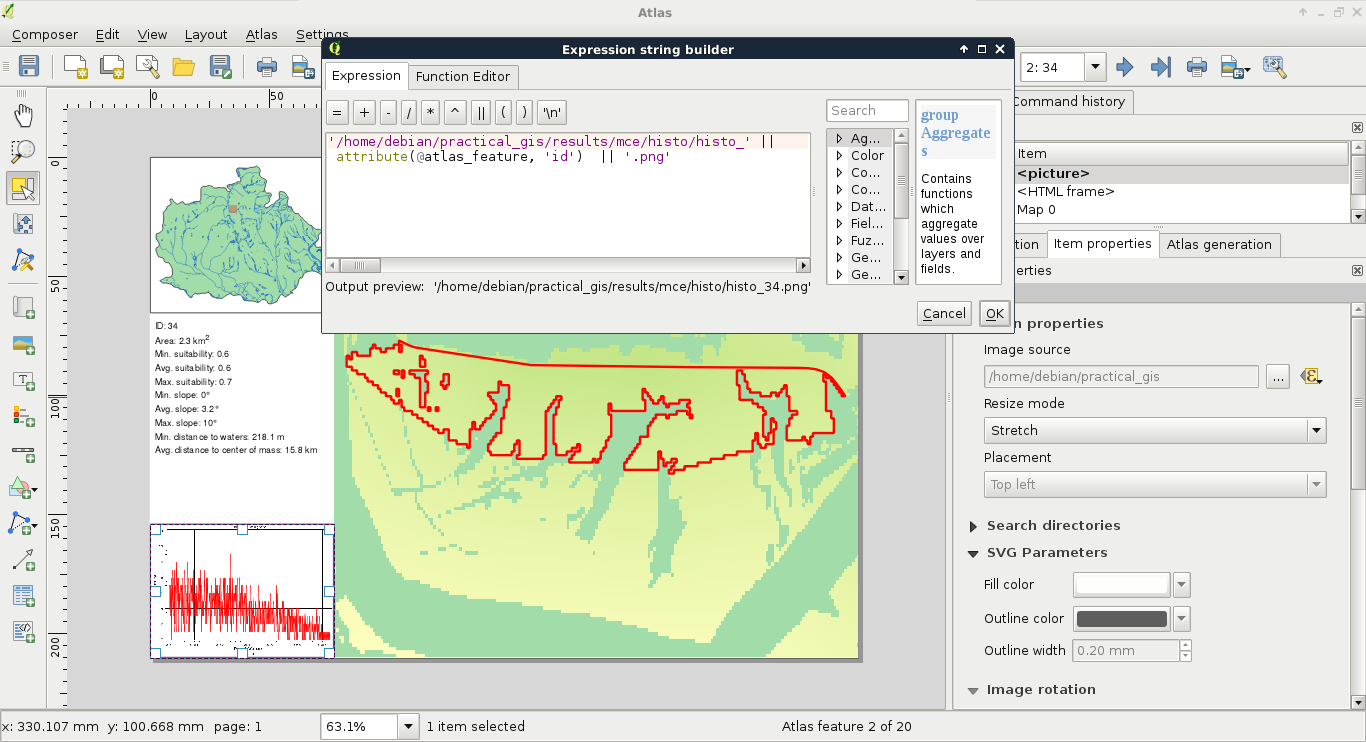

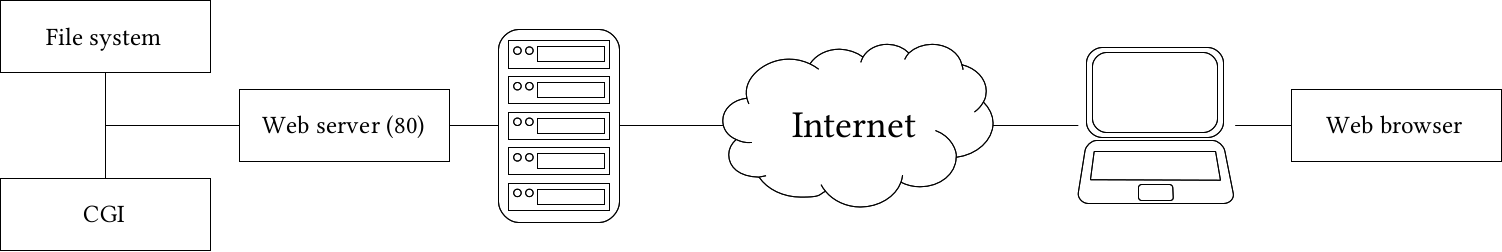

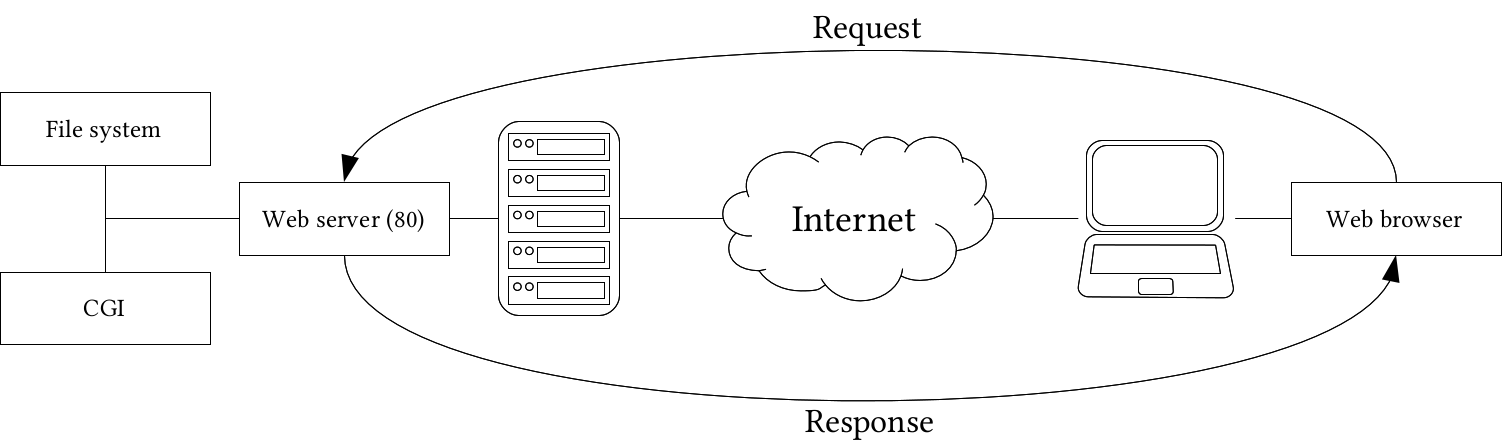

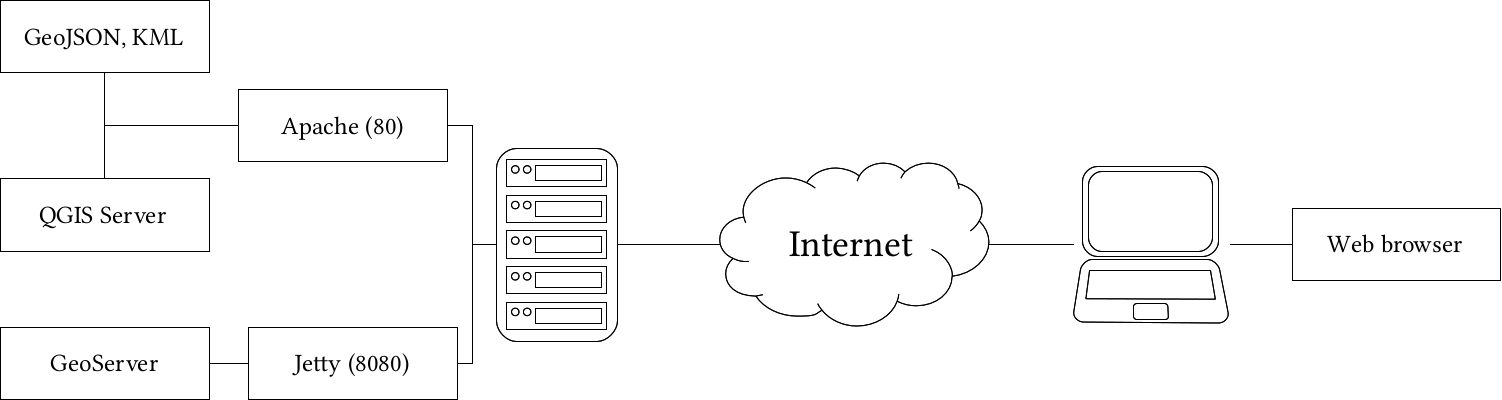

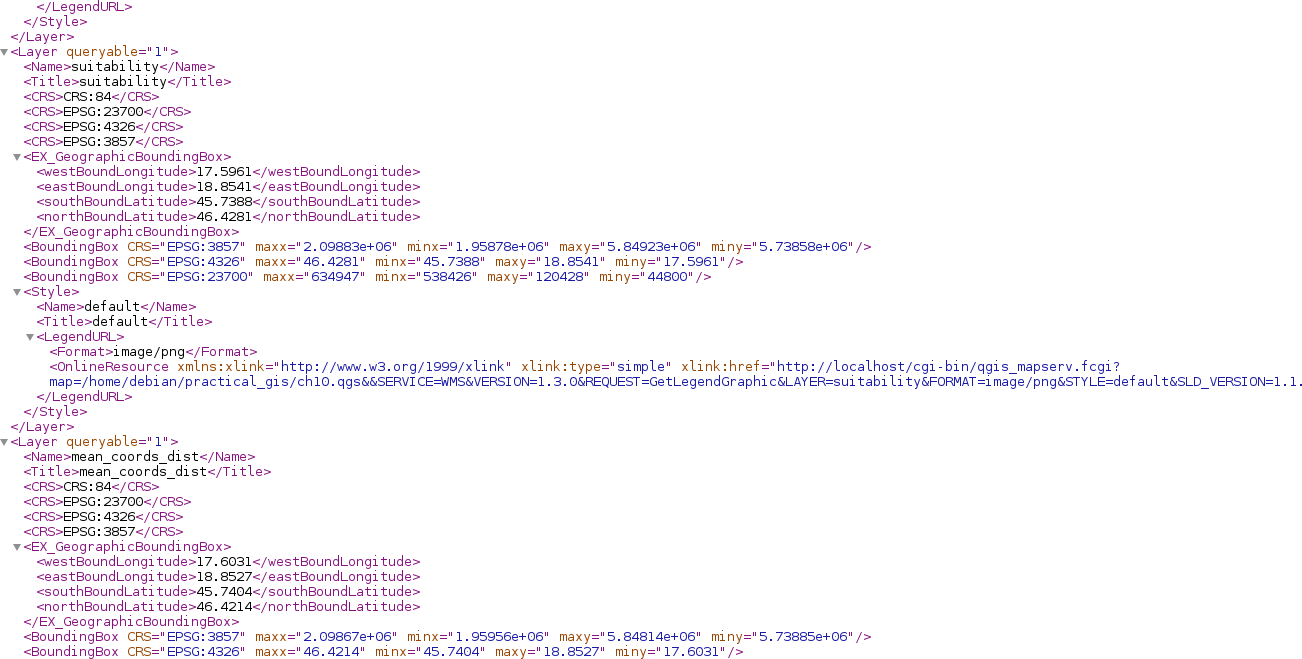

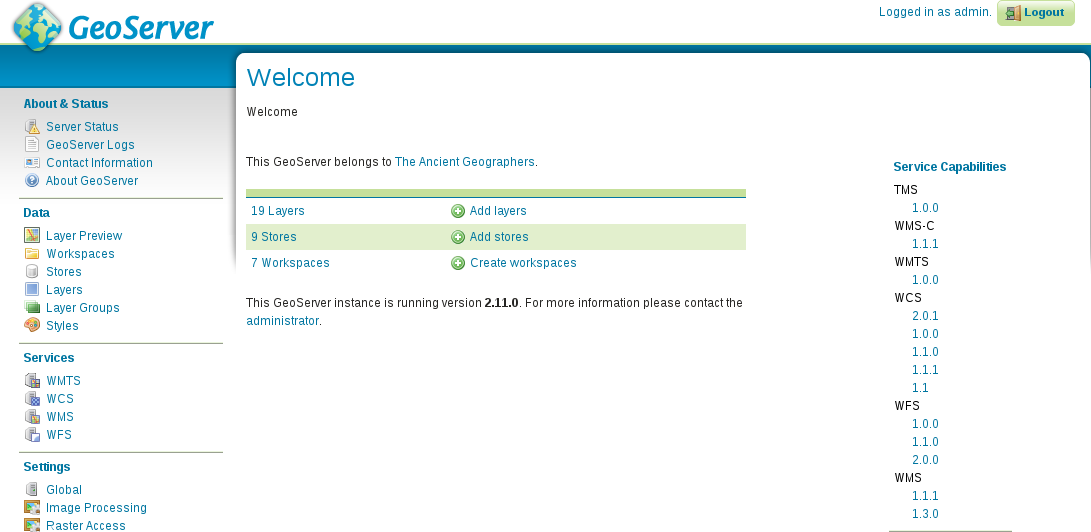

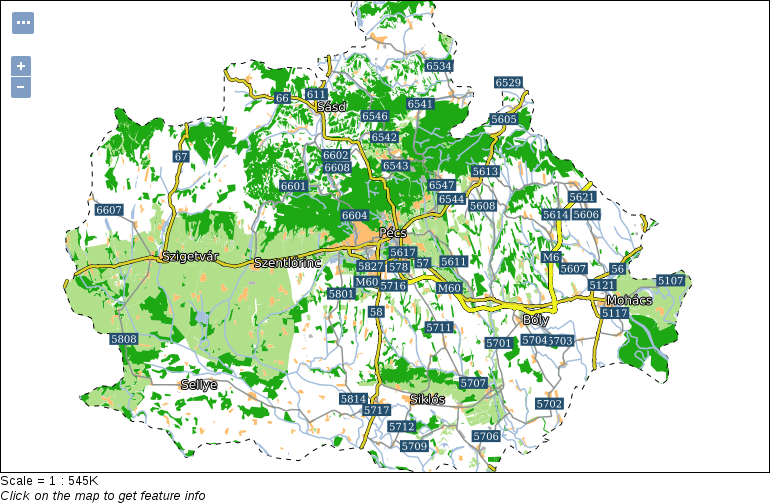

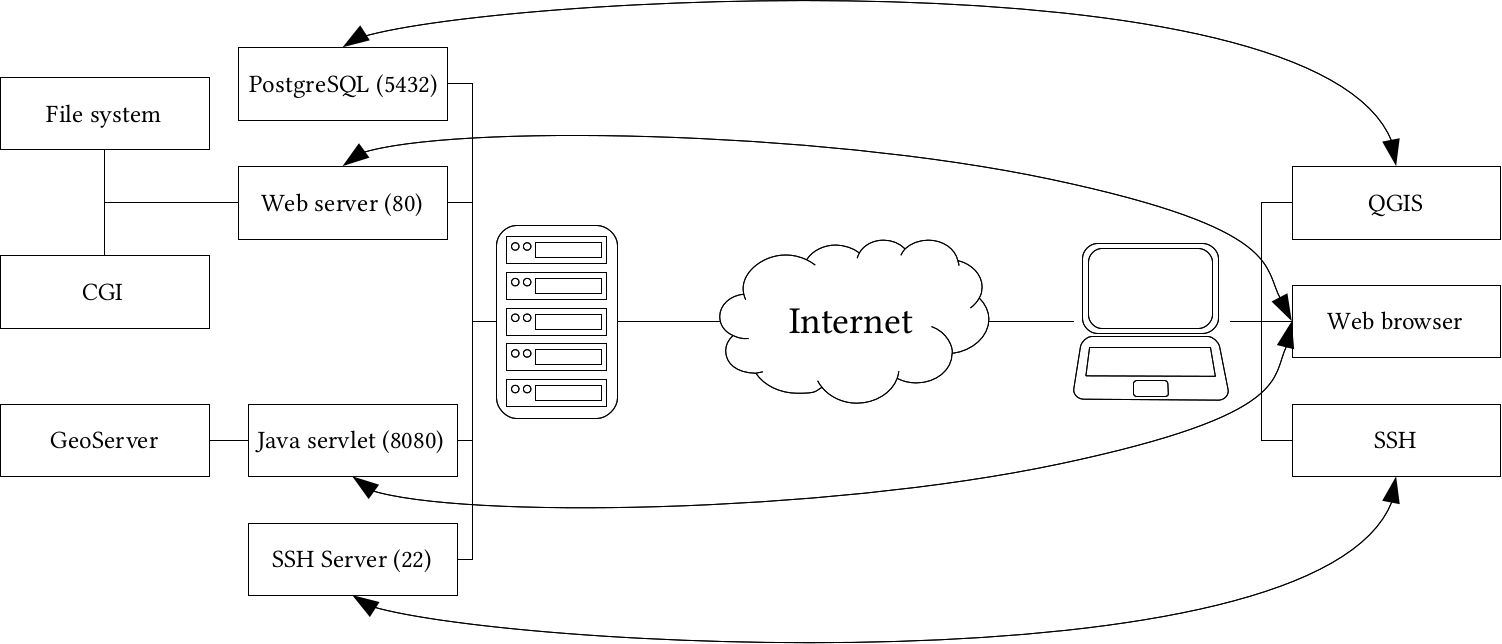

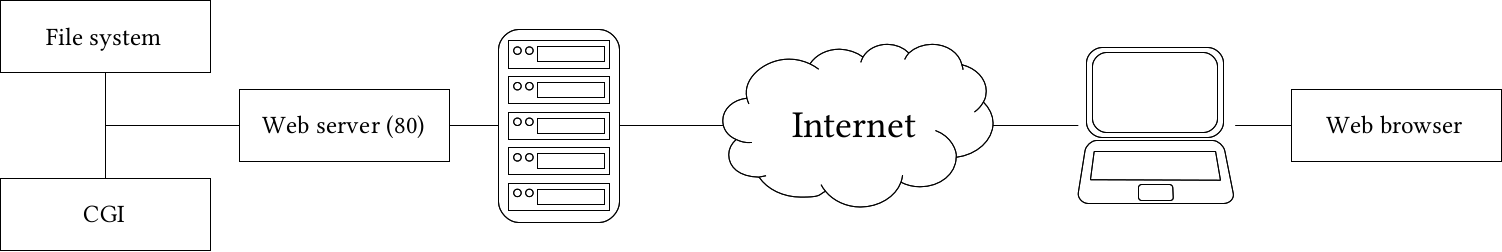

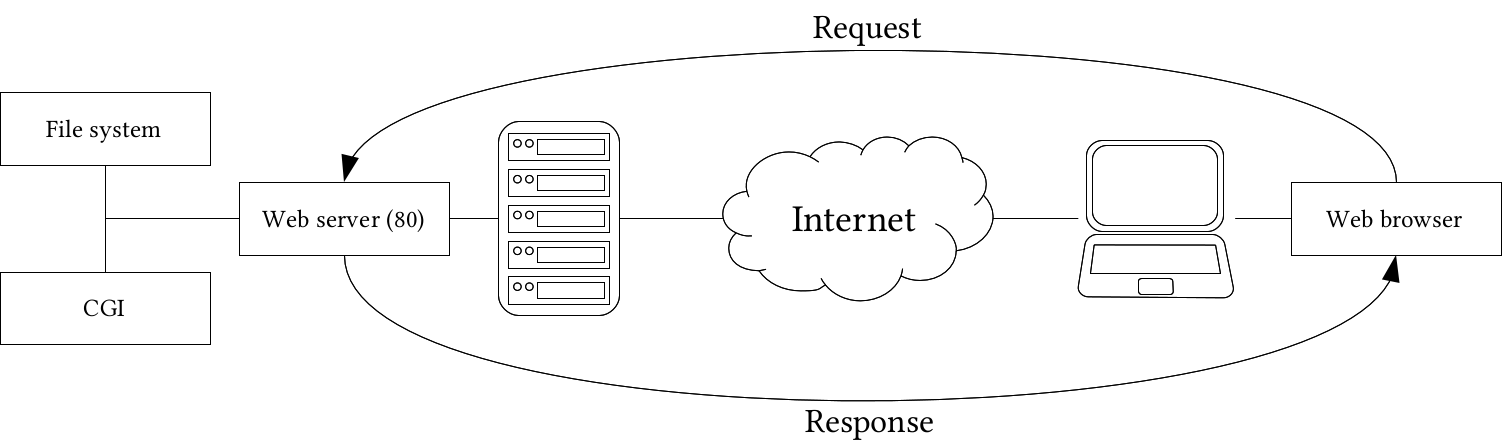

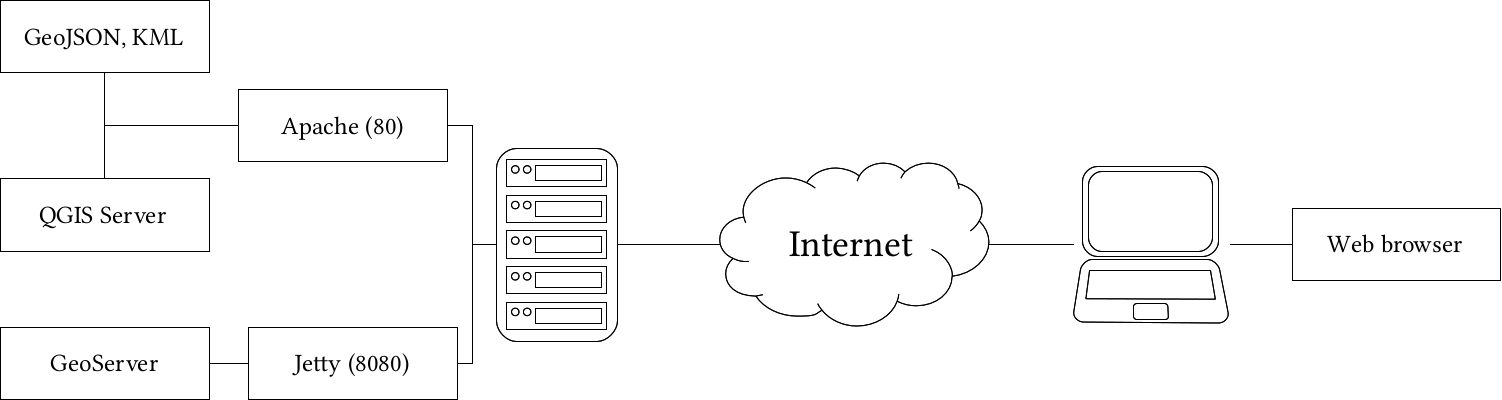

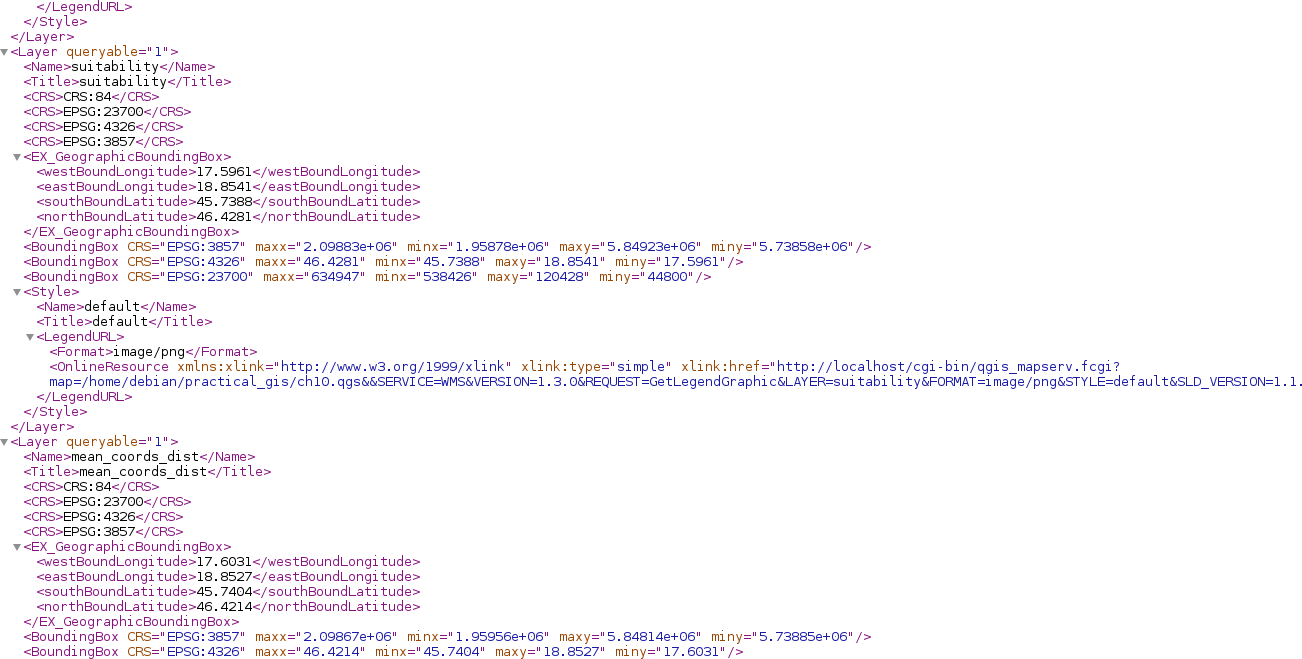

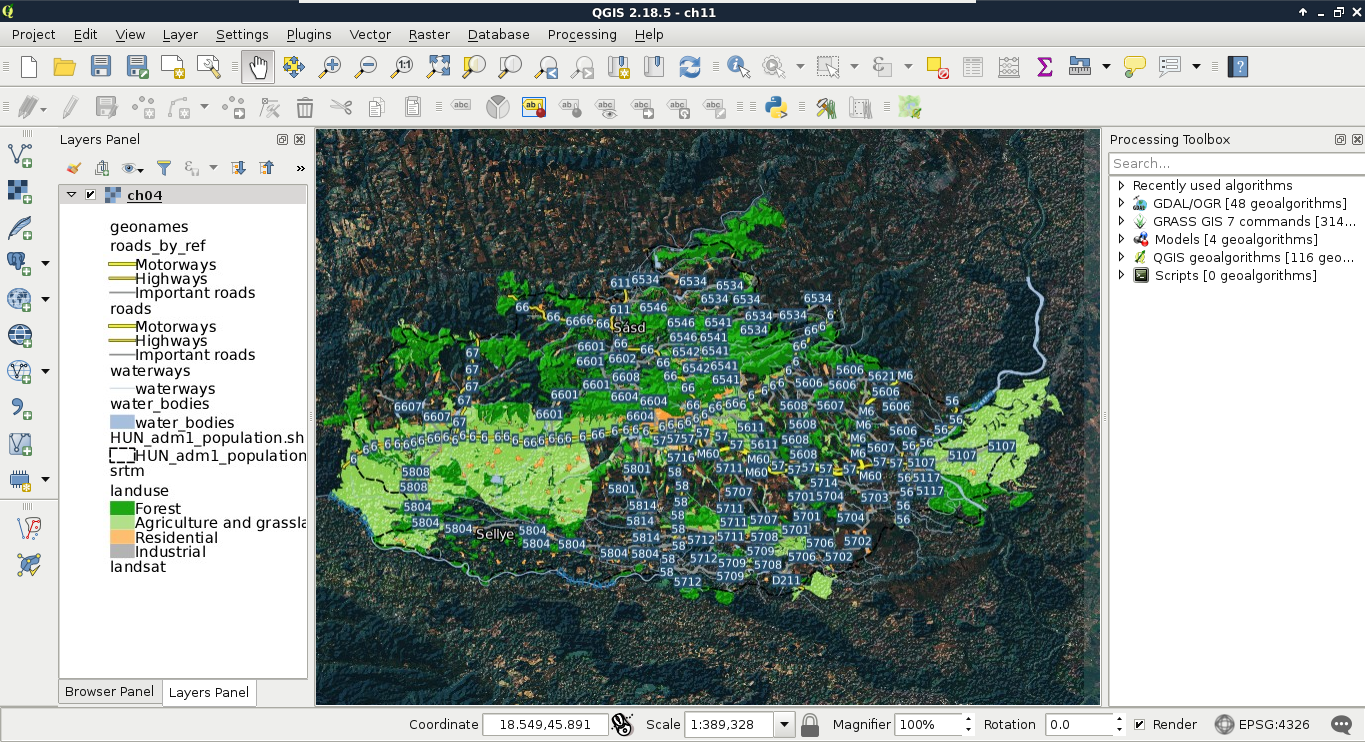

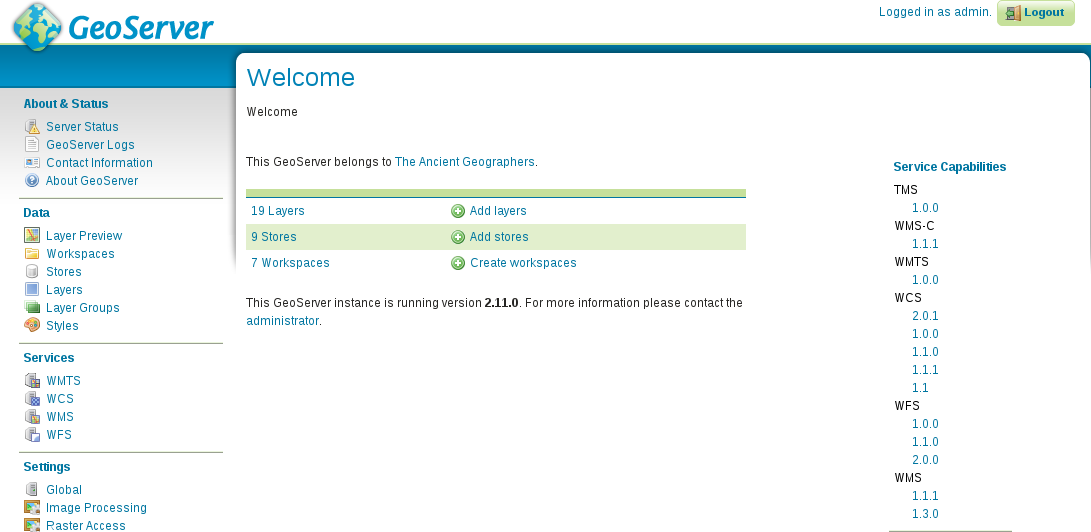

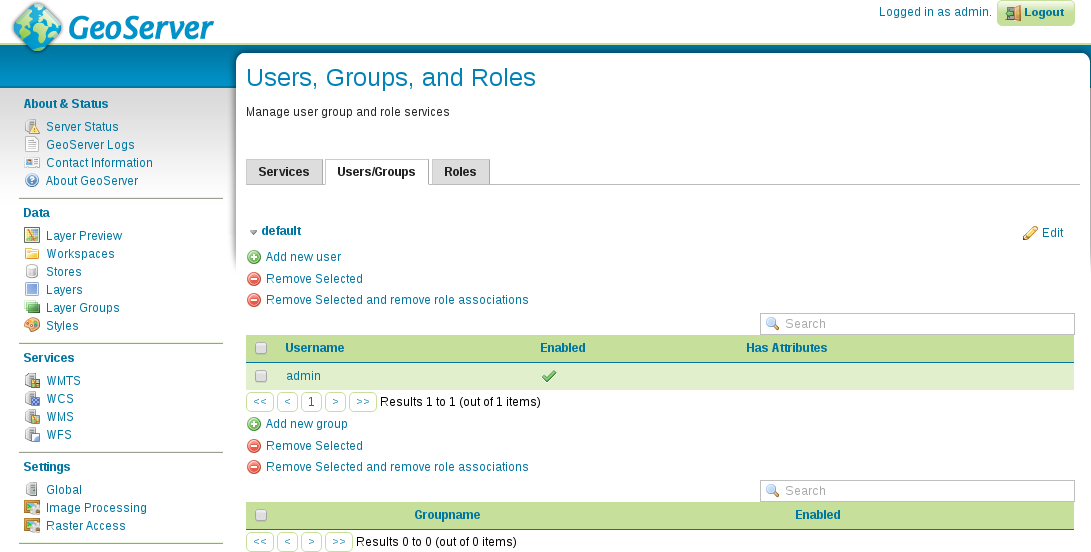

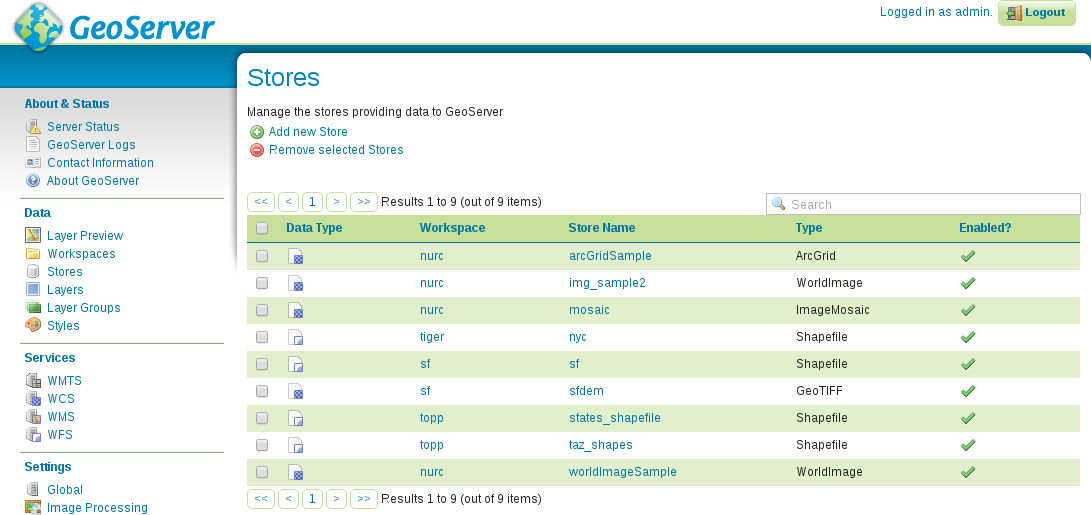

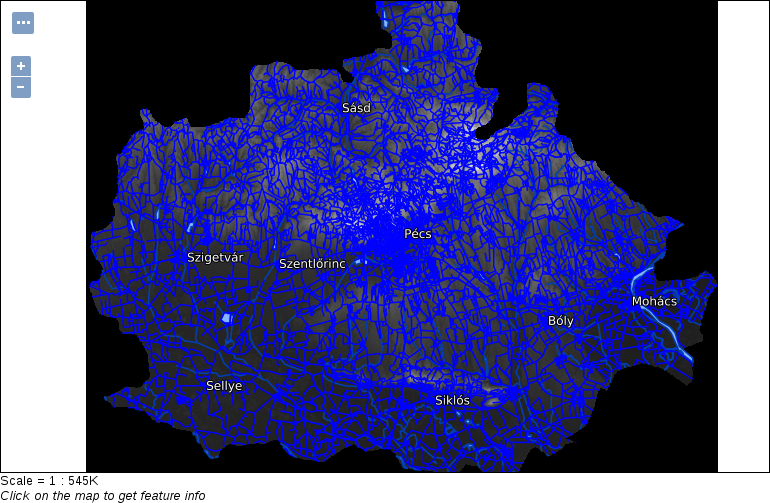

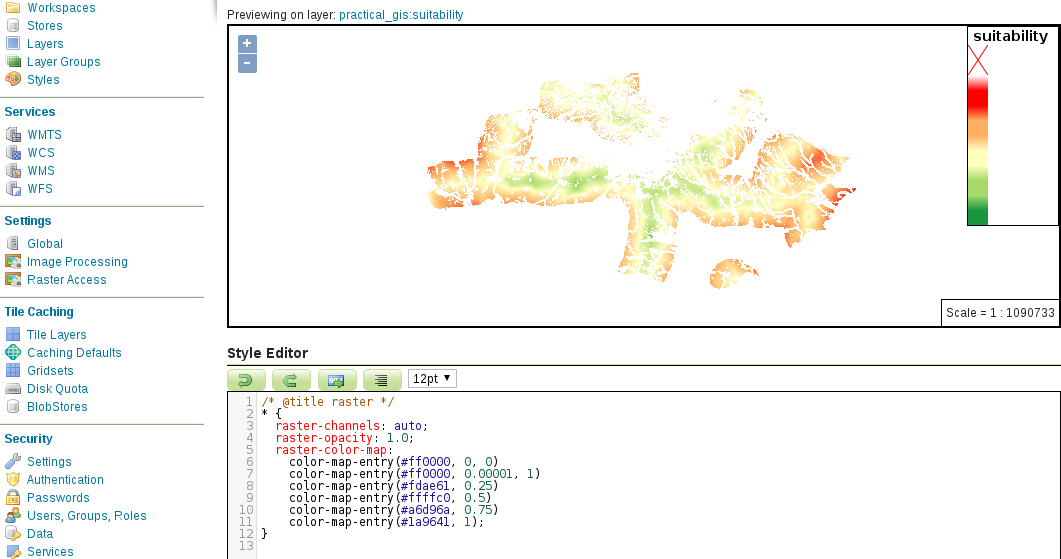

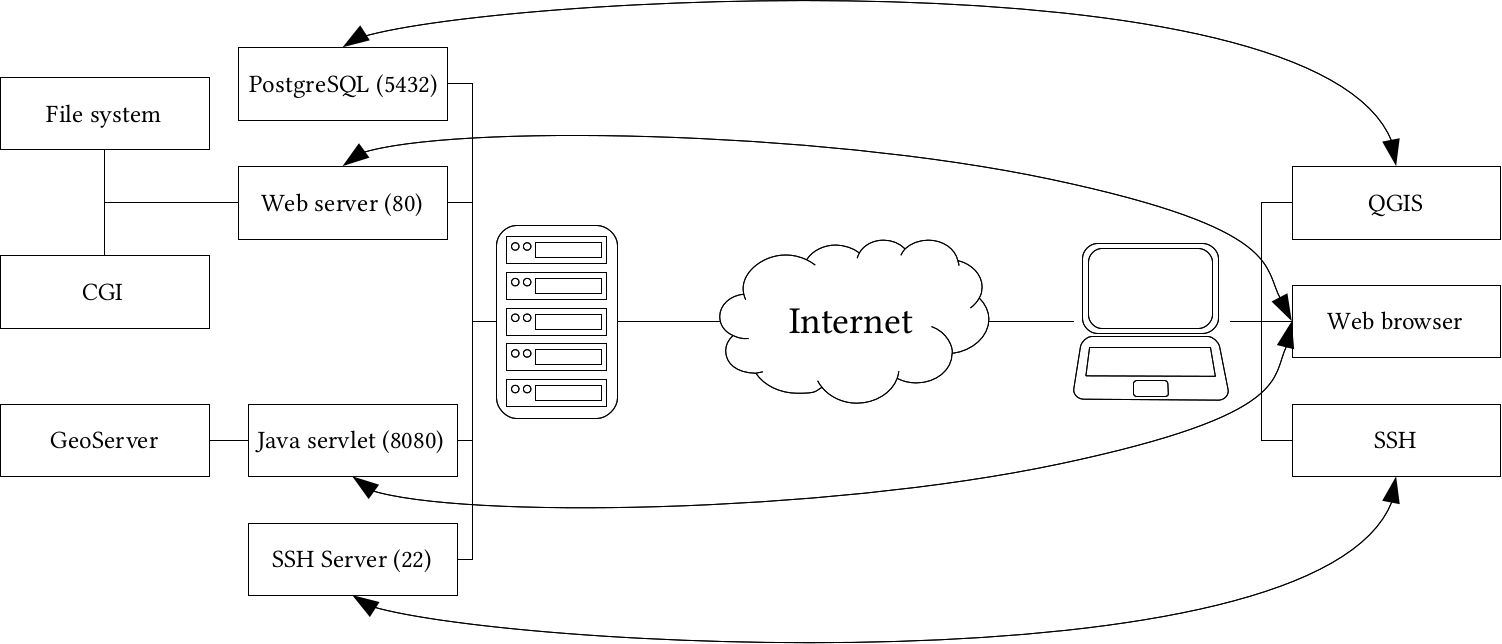

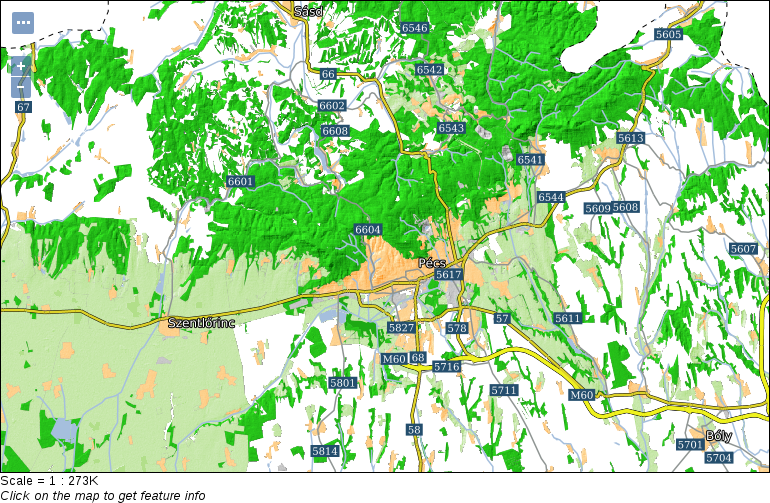

Chapter 11, Showcasing Your Data, goes on to the Web stack, and discusses the basics of the Web, the client-server architecture, and spatial servers. It goes into details on how to use the QGIS Server to create quick visualizations, and how to use GeoServer to build a powerful spatial server with great capabilities.

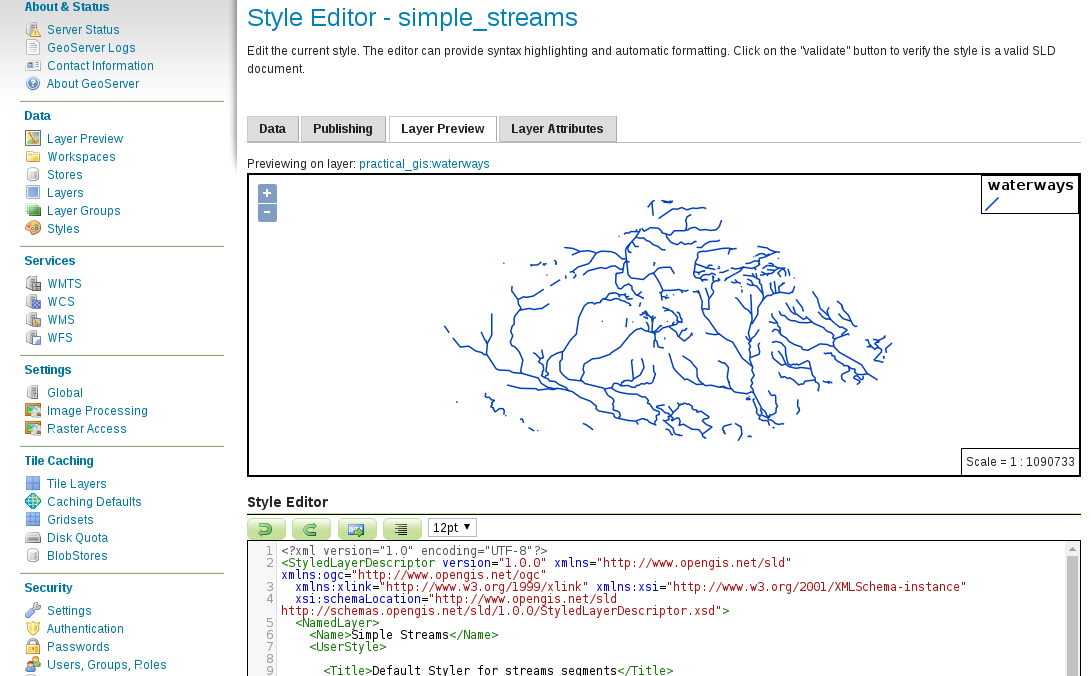

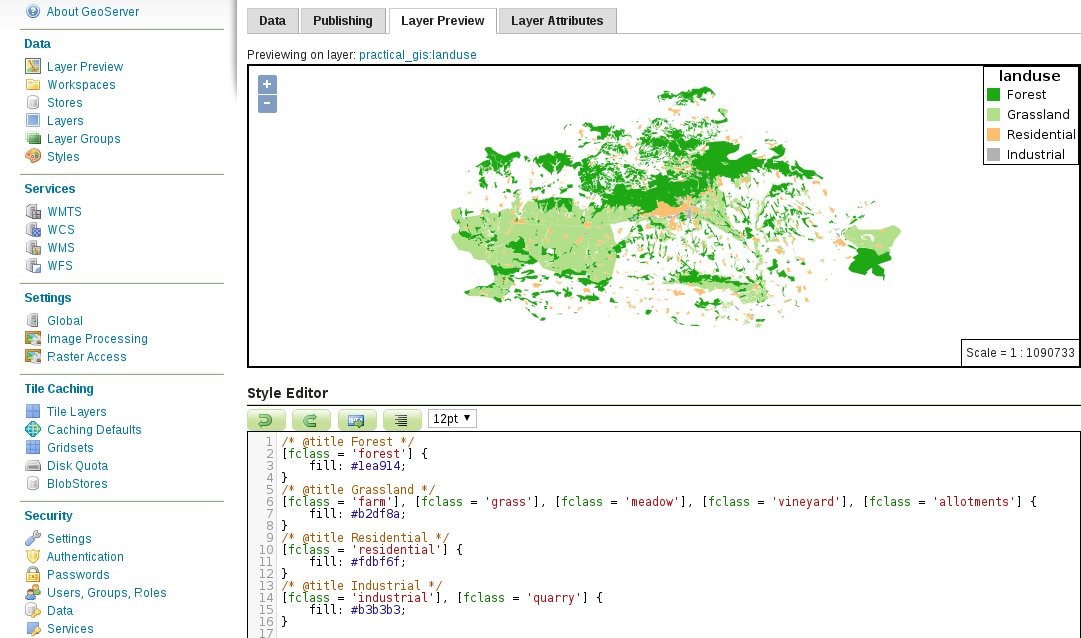

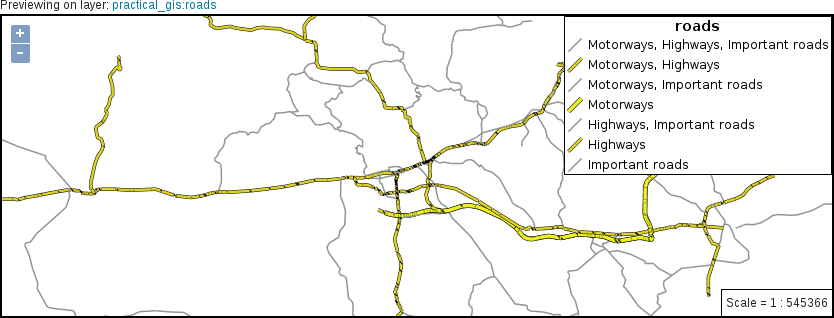

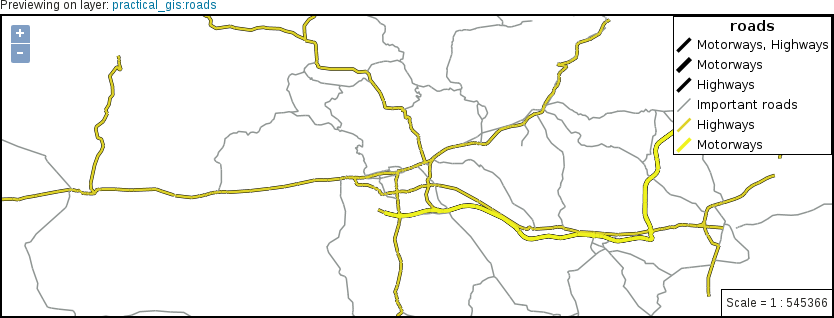

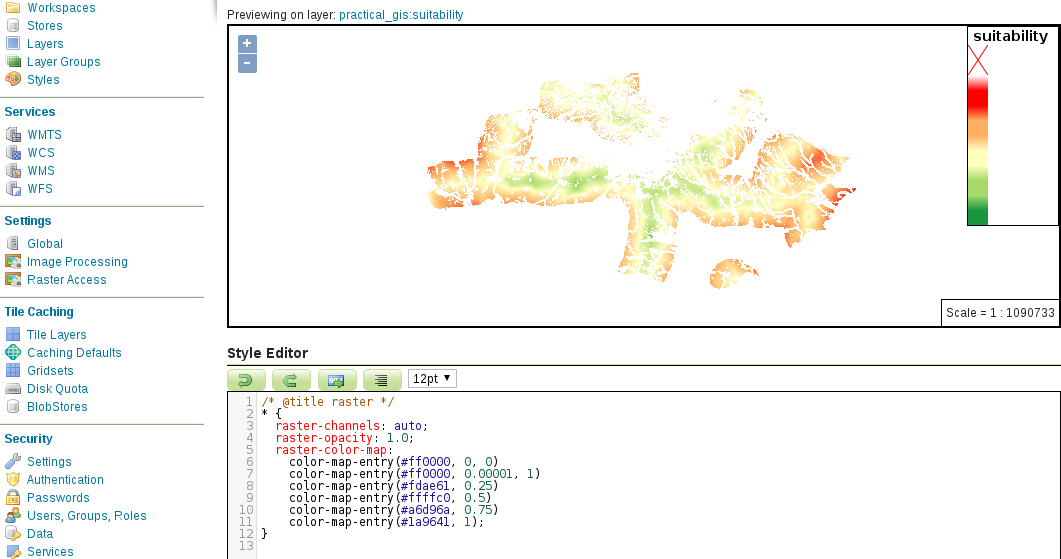

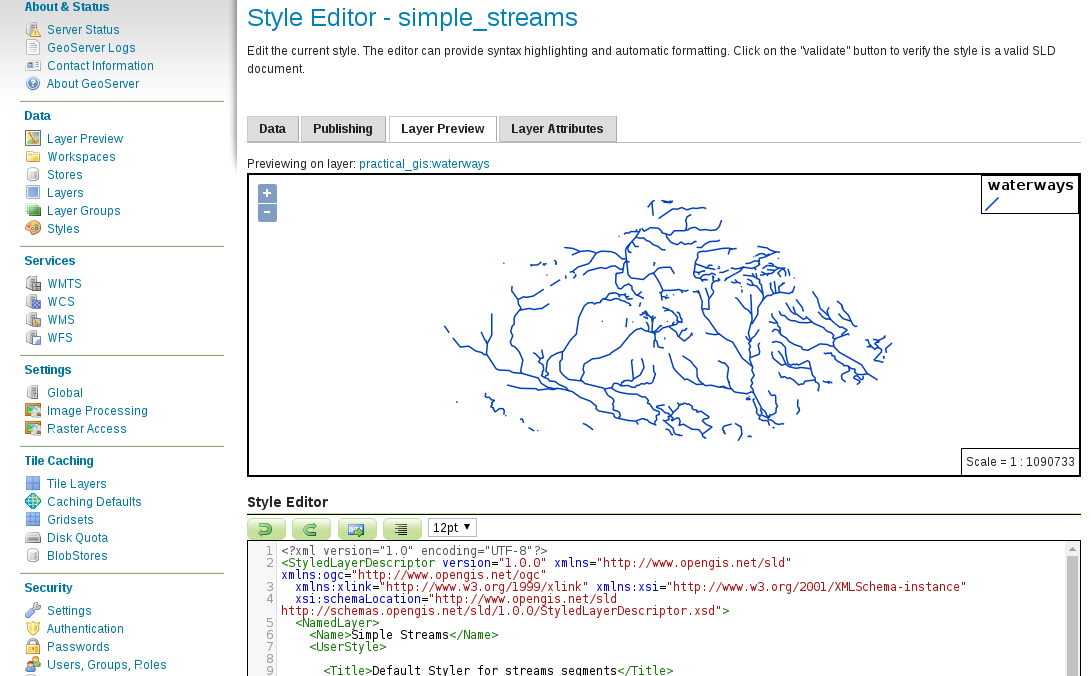

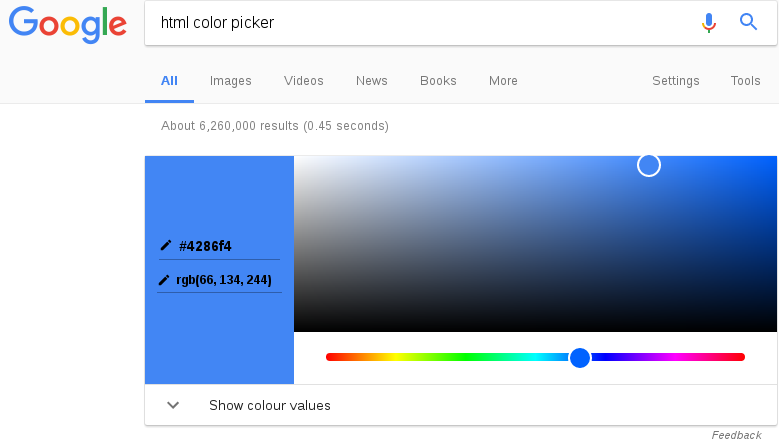

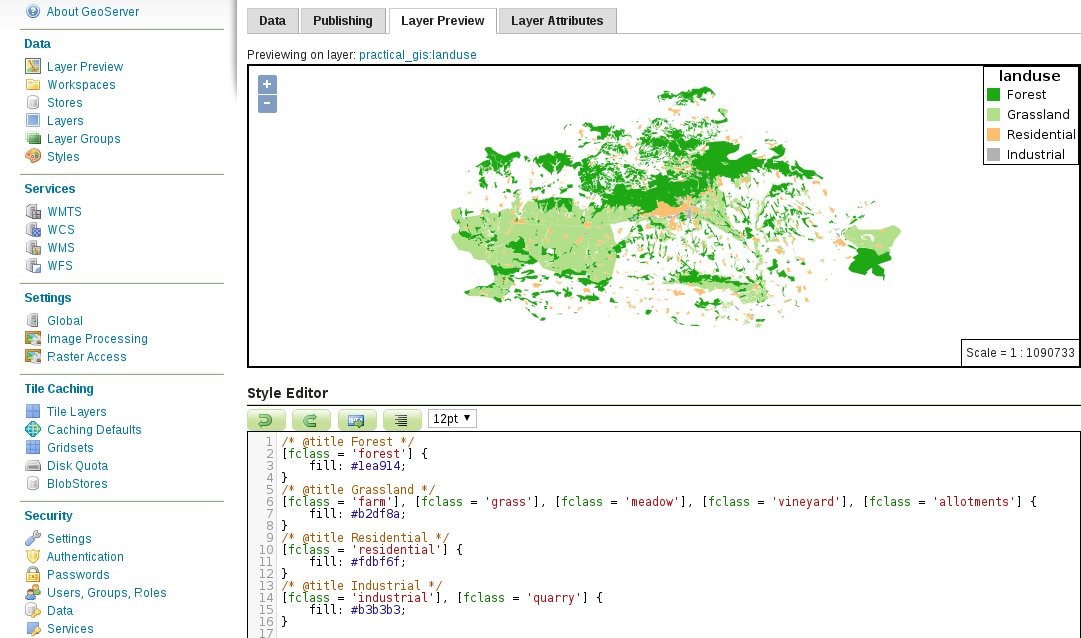

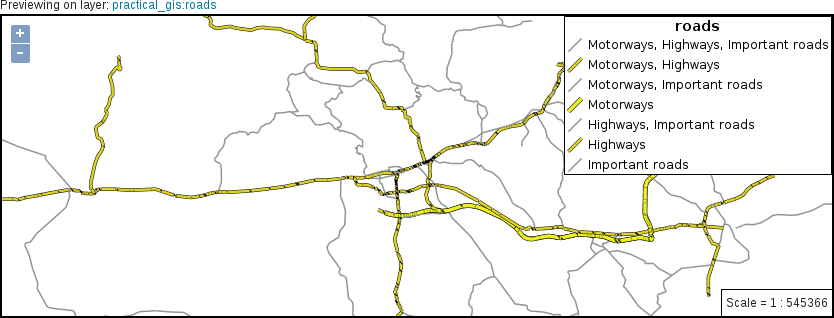

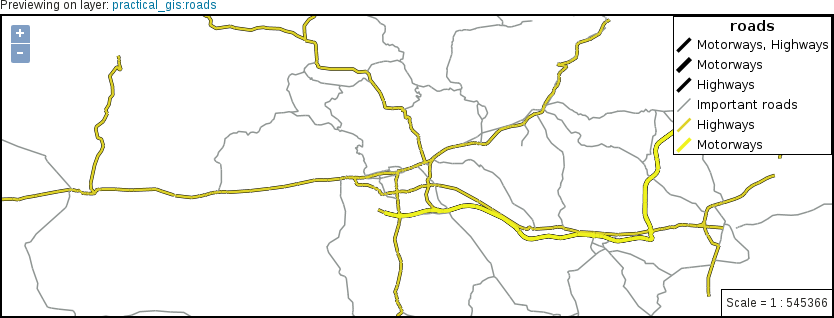

Chapter 12, Styling Your Data in GeoServer, discusses the basic vector and raster symbology usable in GeoServer. It goes through the styling process by using traditional SLD documents. When the concepts are clear, it introduces the powerful and convenient GeoServer CSS, which is also based on SLD.

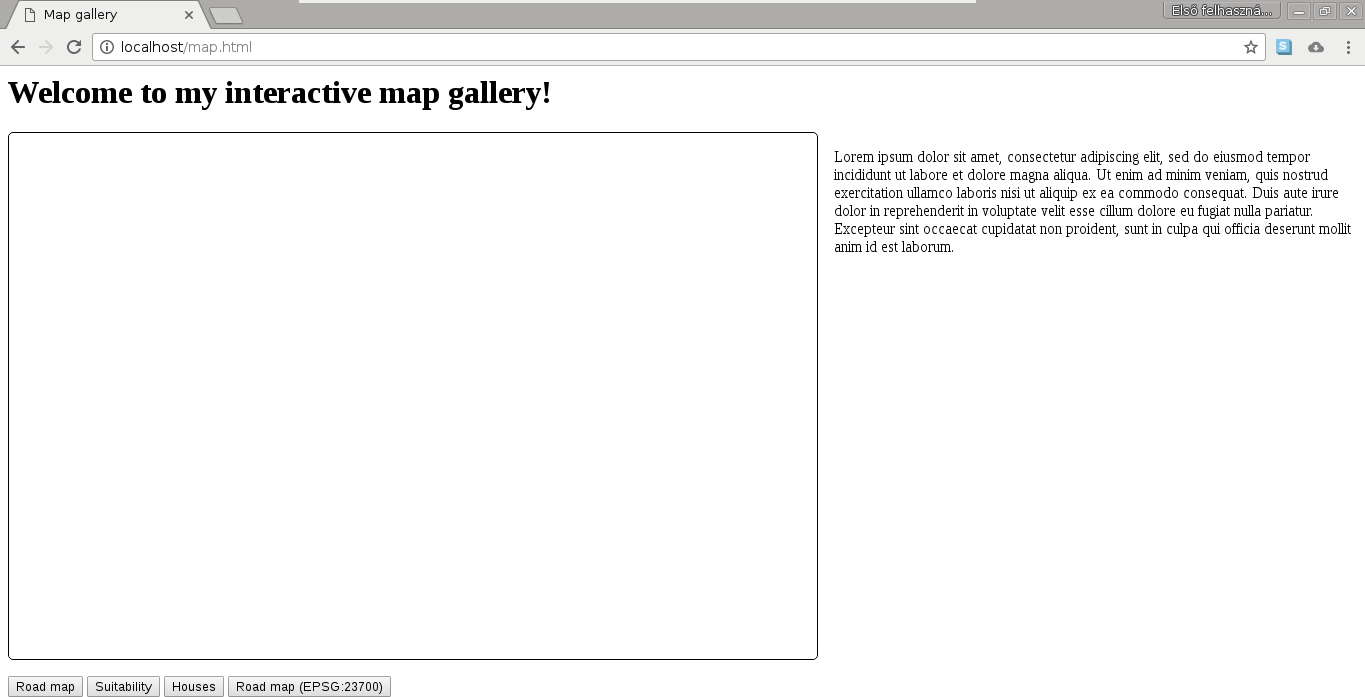

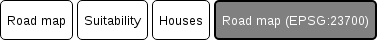

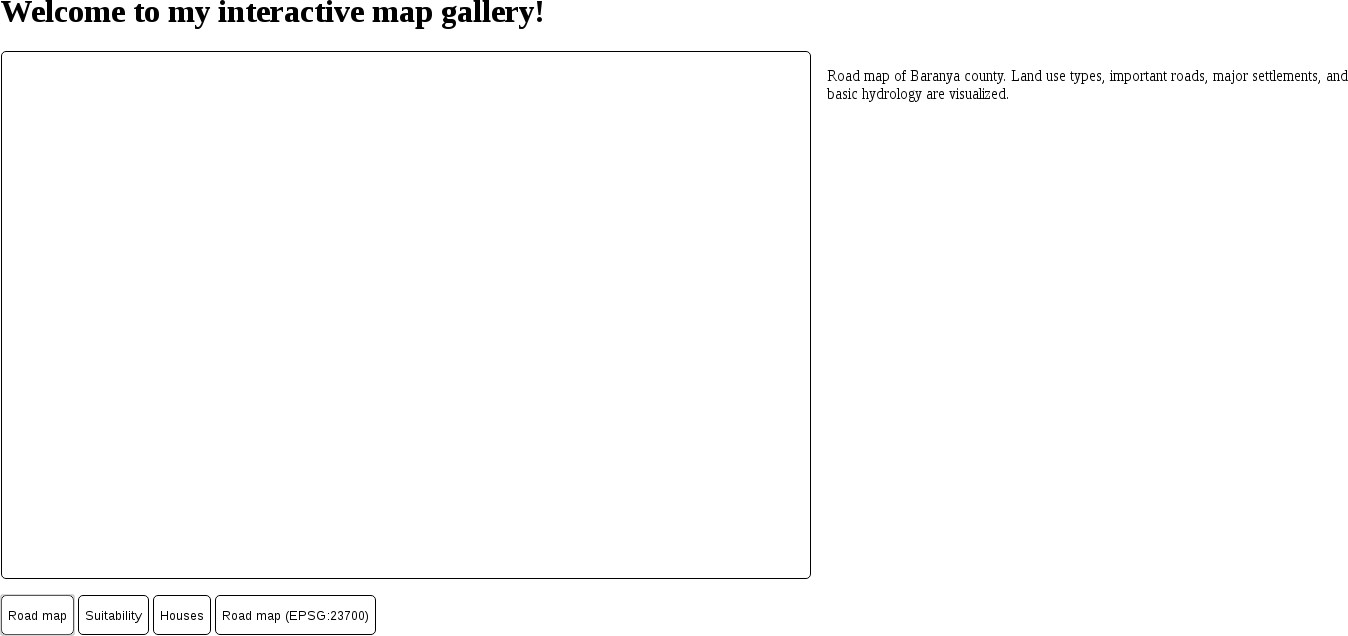

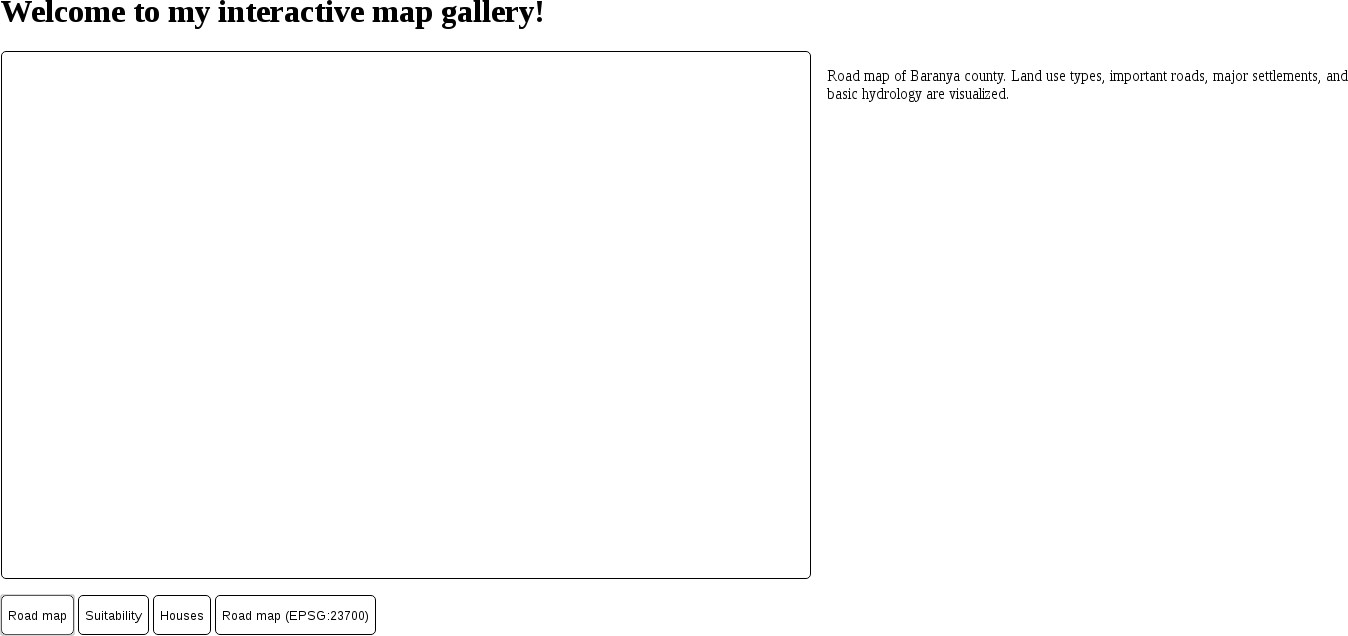

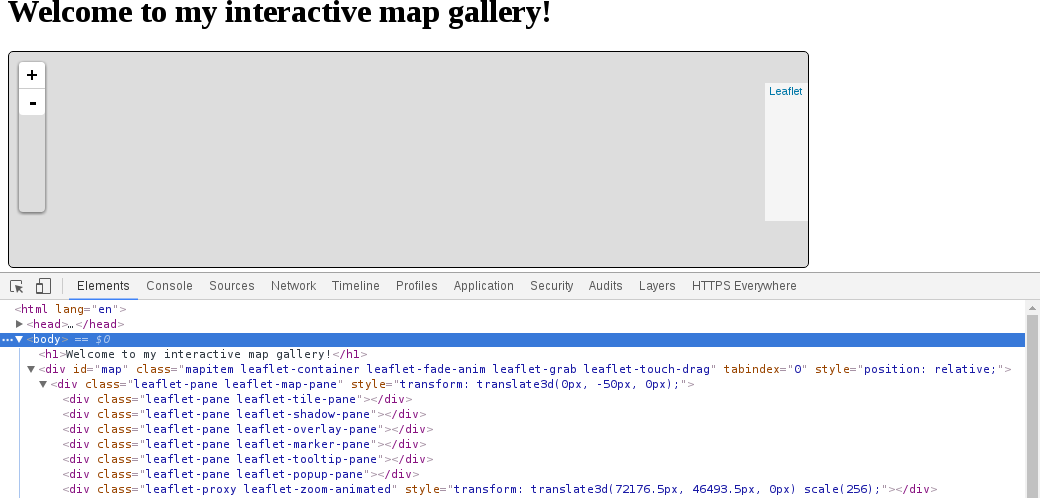

Chapter 13, Creating a Web Map, jumps to the client side of the Web and shows you how to create simple web maps using the server architecture created before, and the lightweight web mapping library--Leaflet. It guides you through the process of creating a basic web map, ranging from creating an HTML document to scripting it with JavaScript.

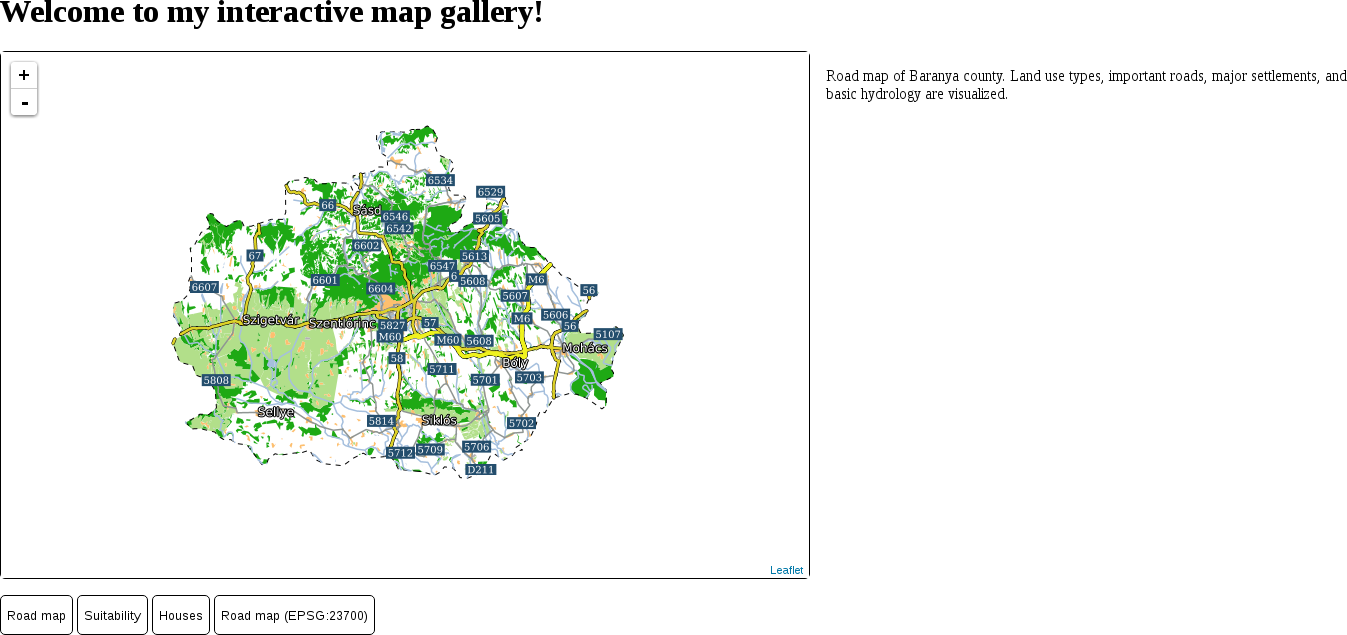

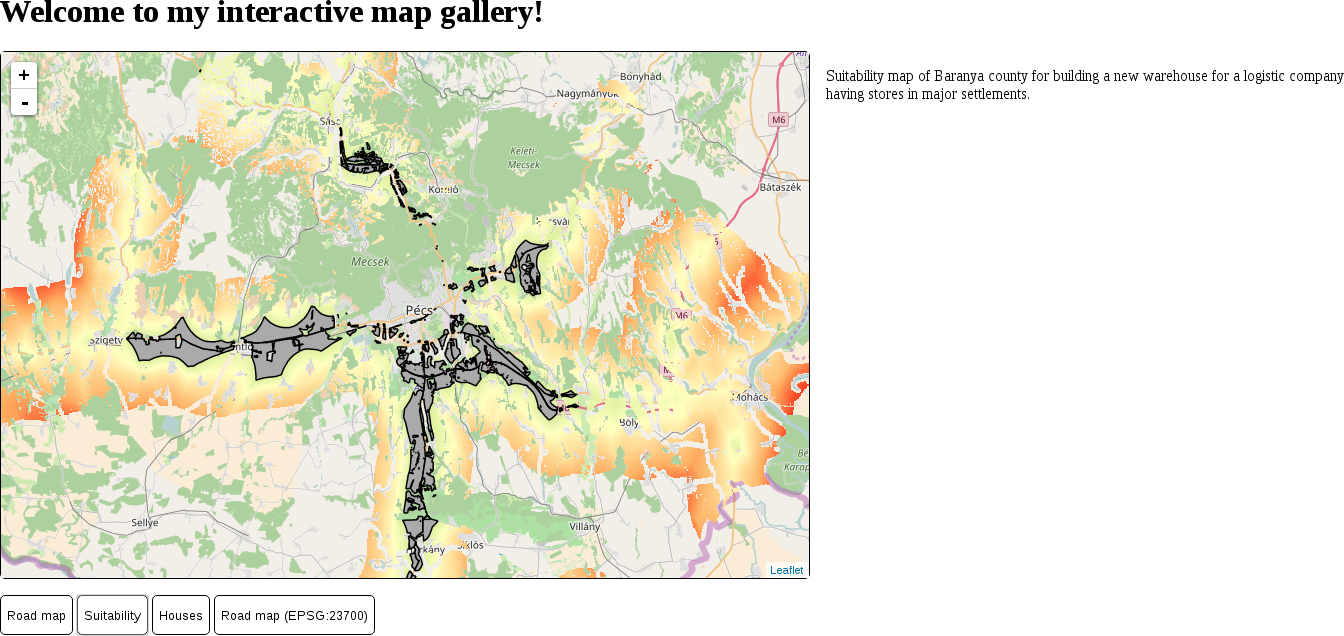

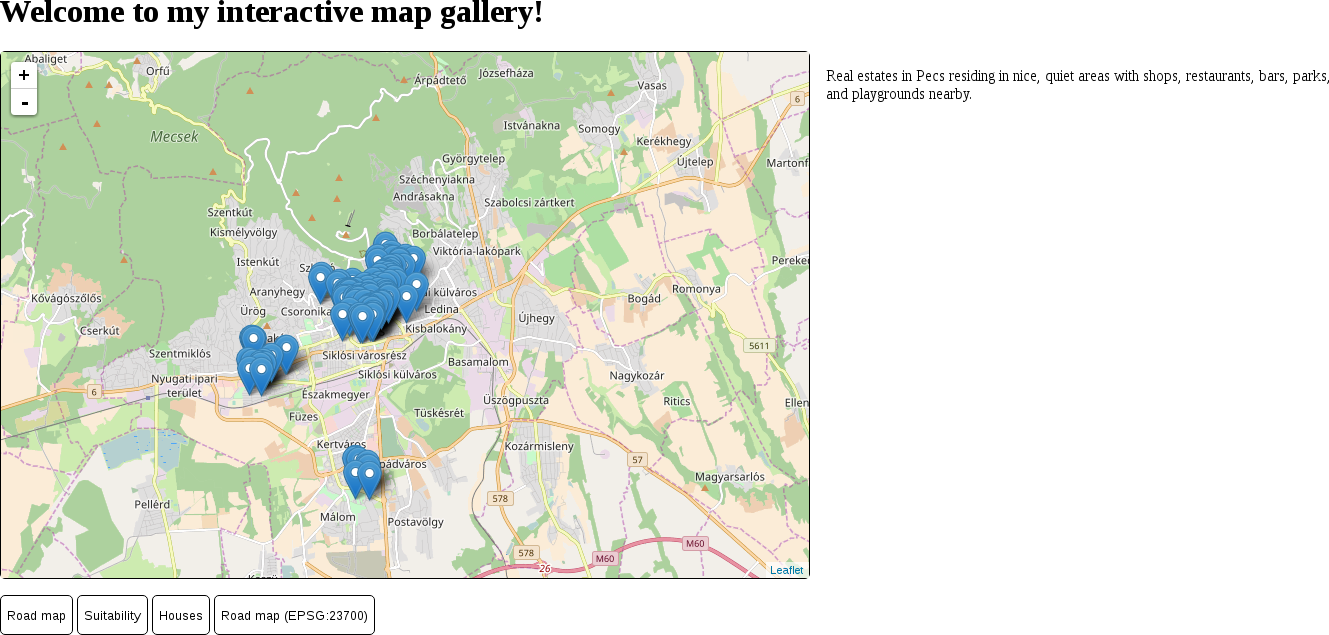

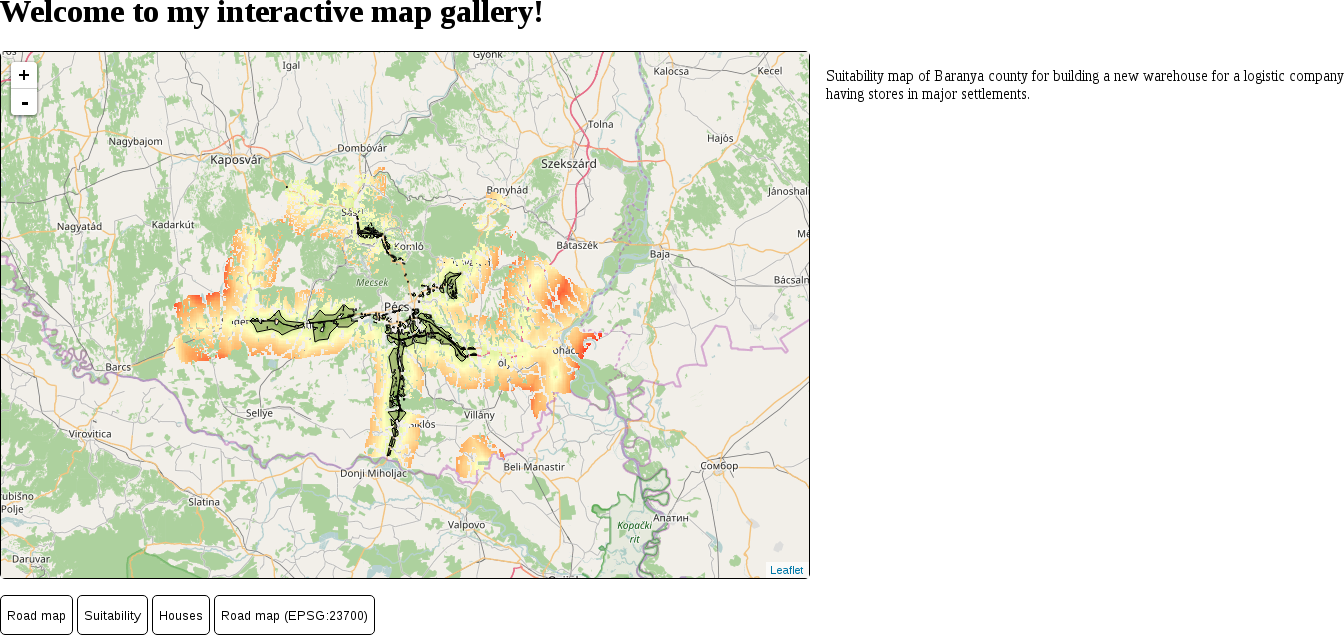

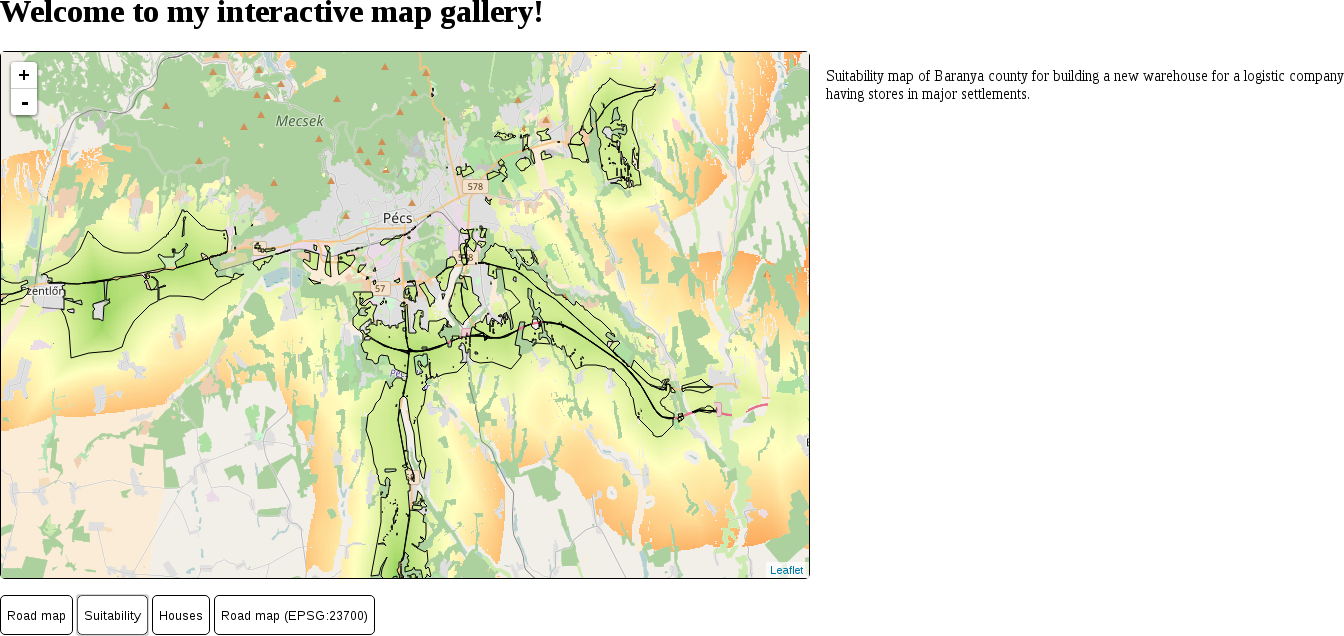

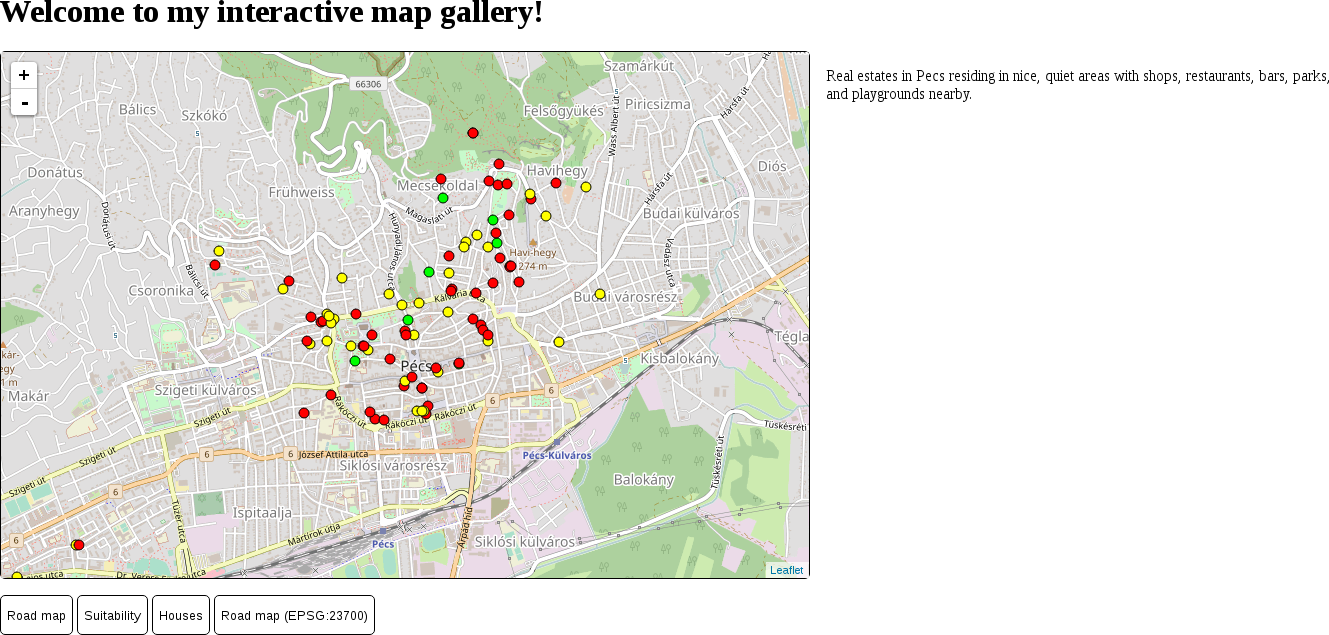

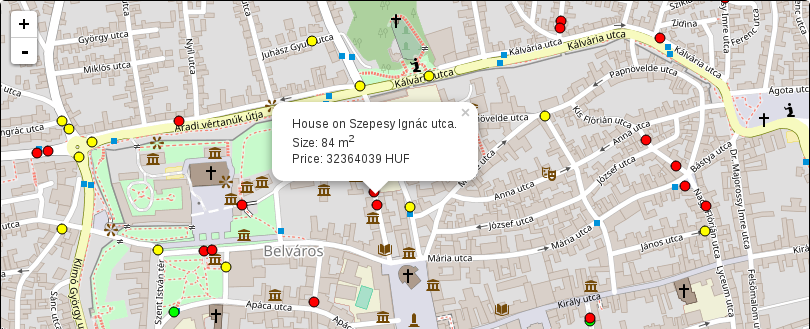

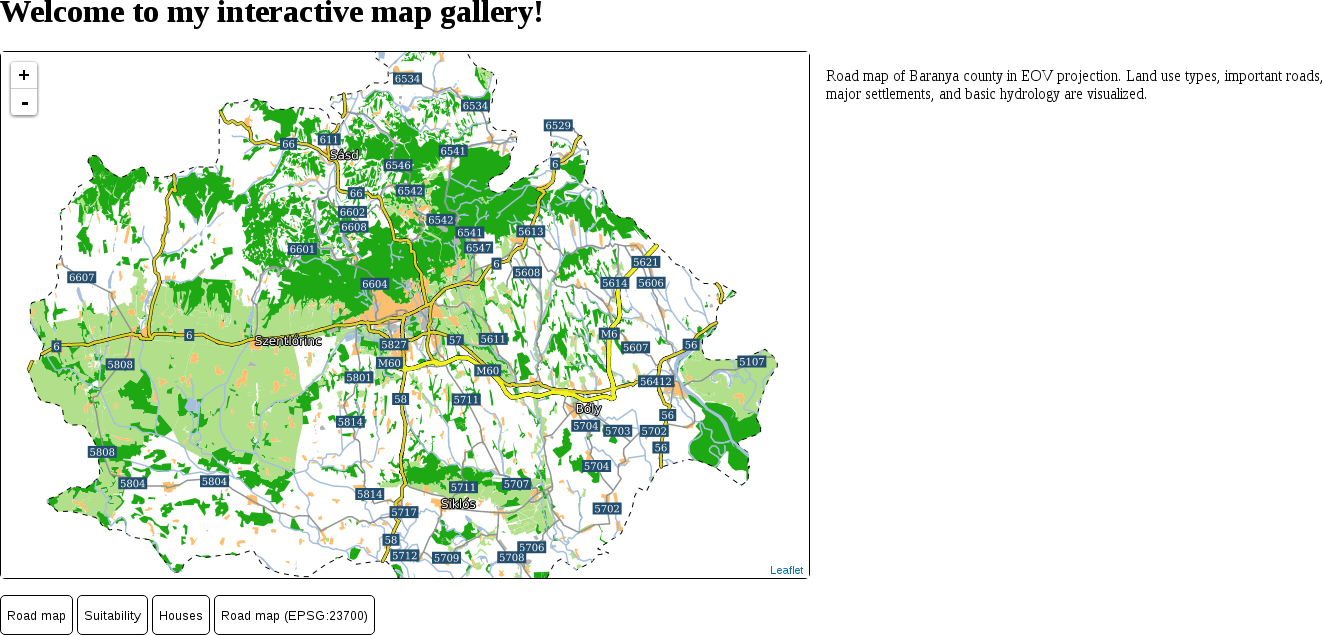

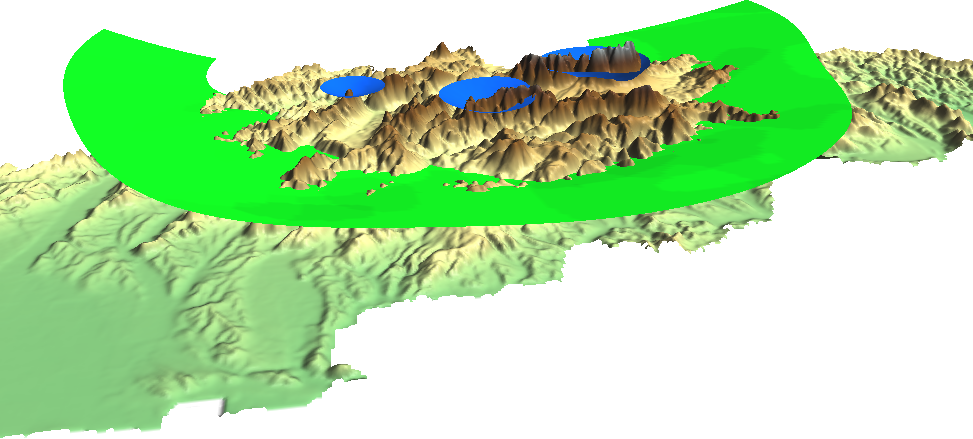

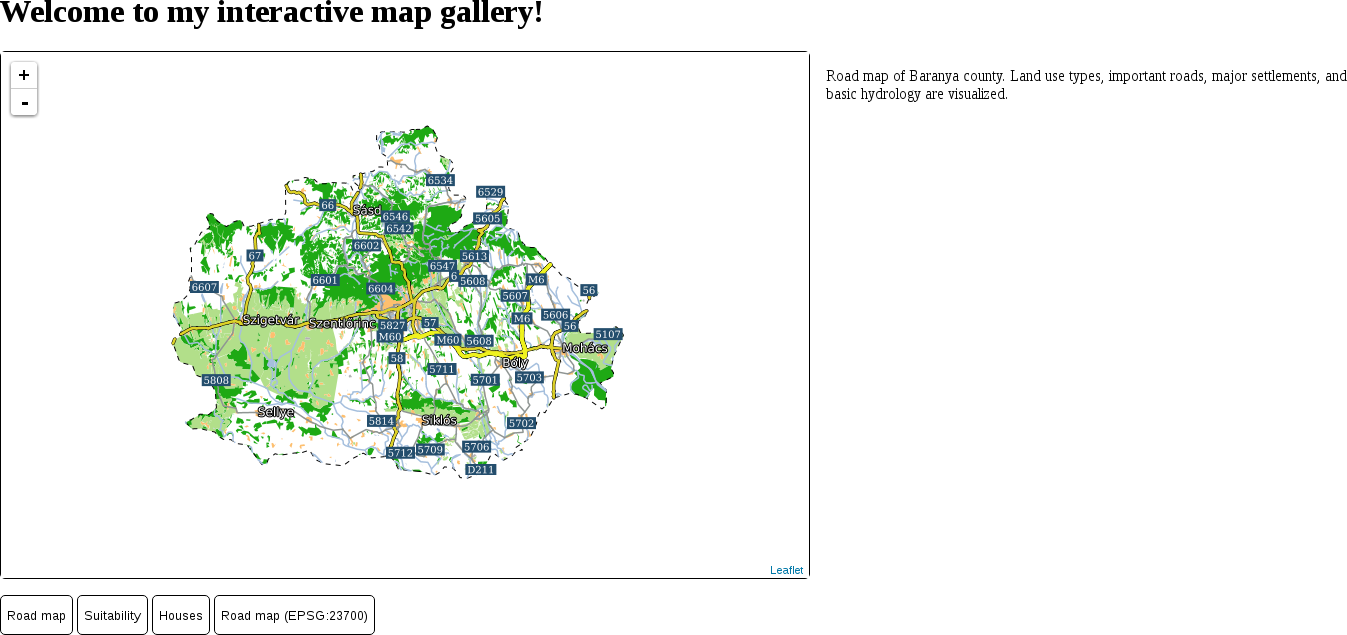

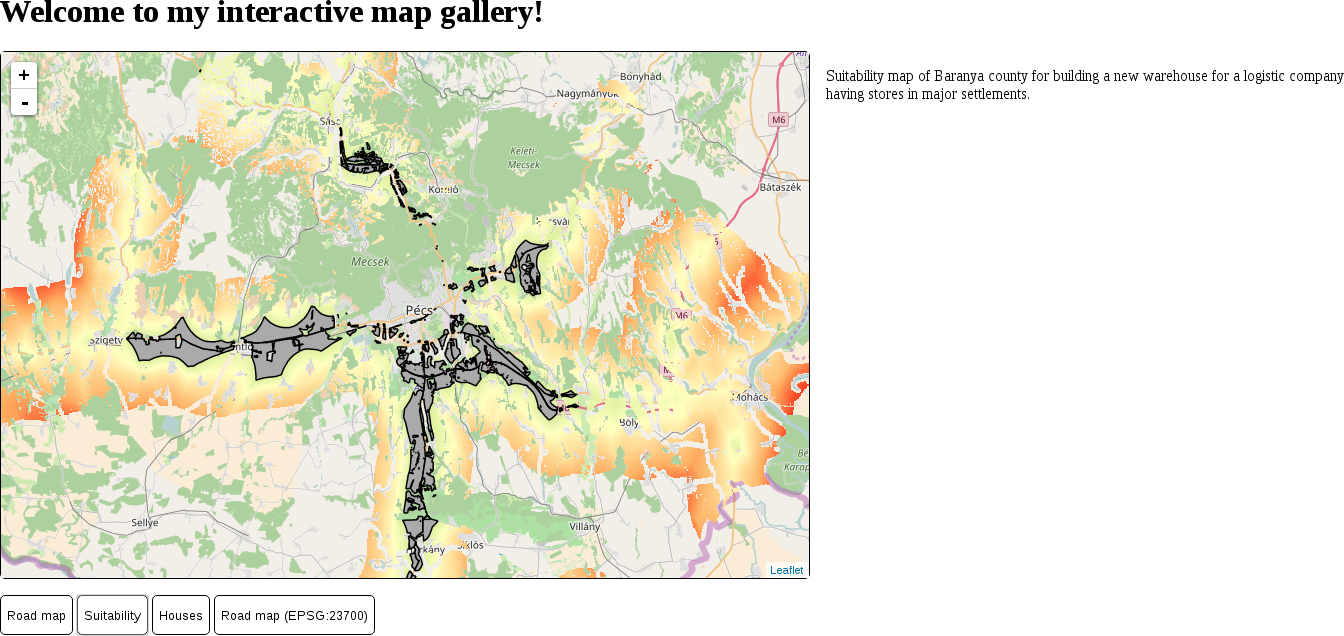

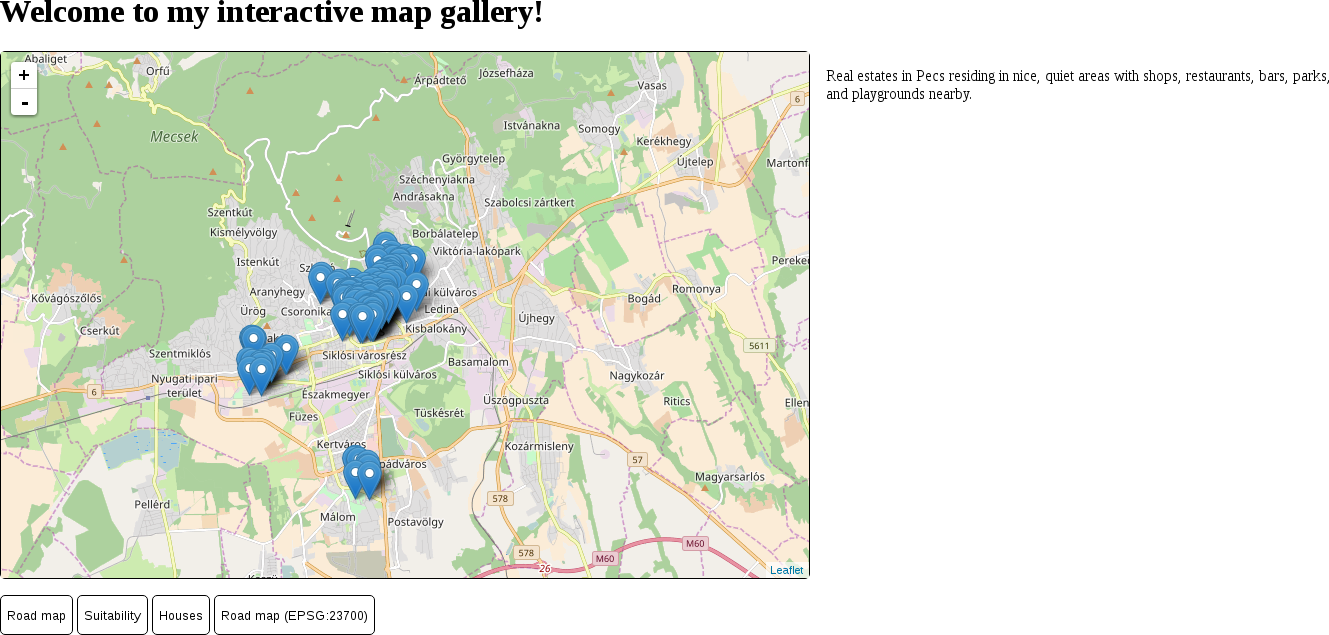

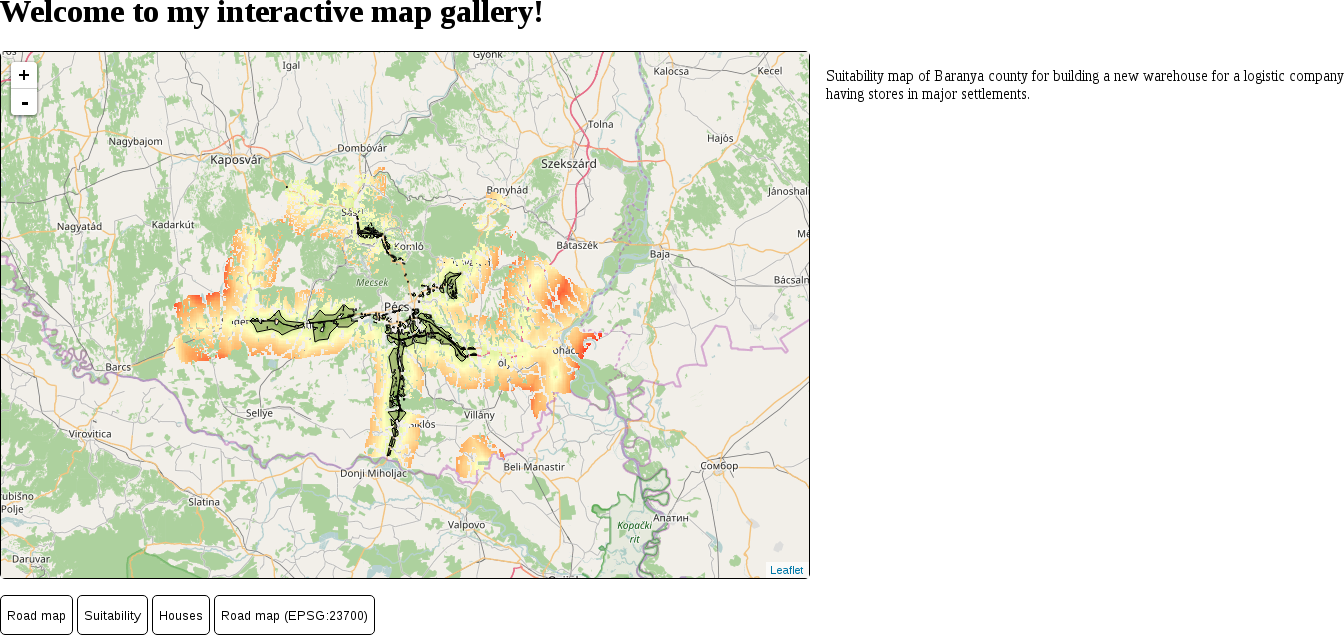

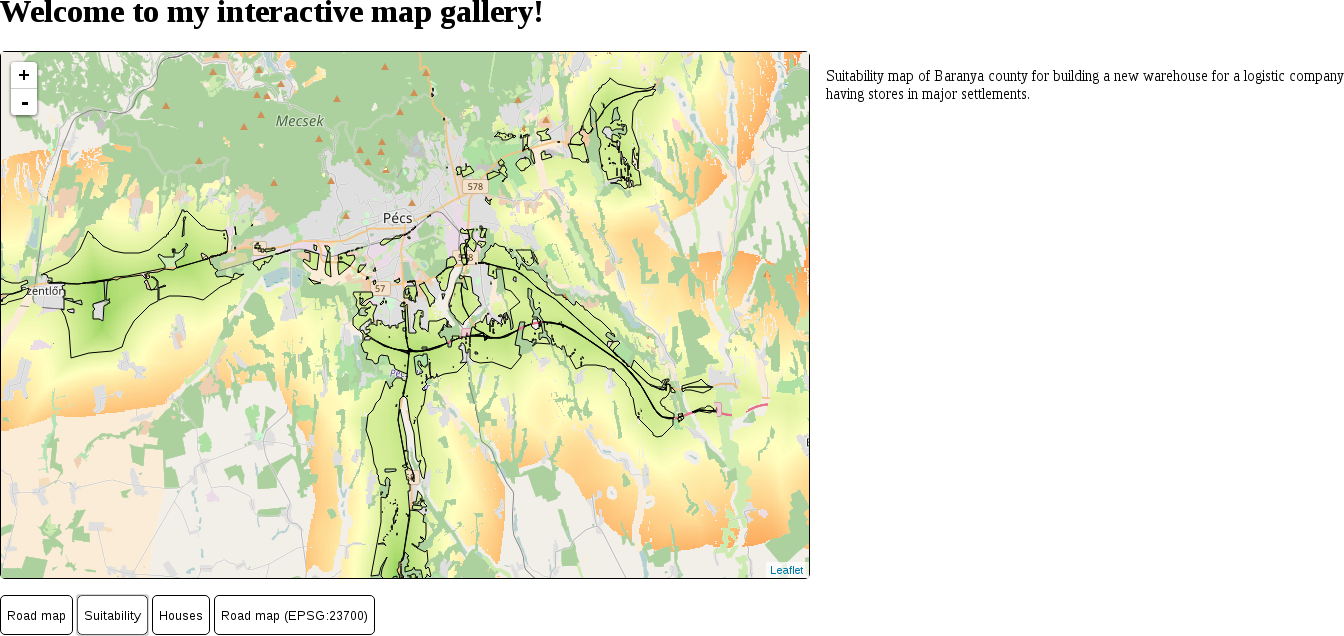

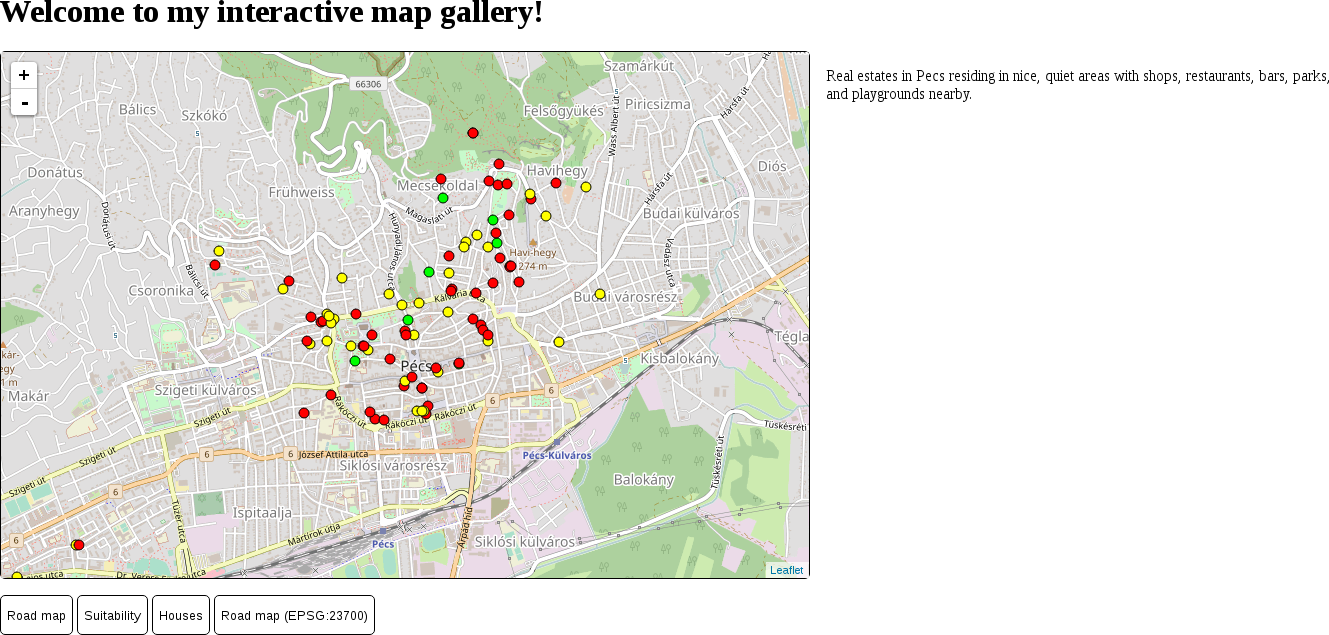

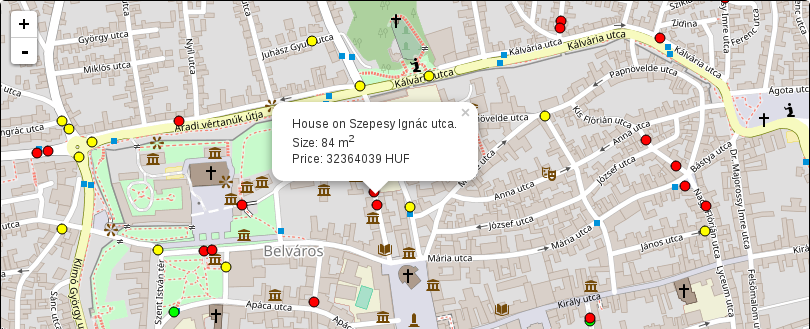

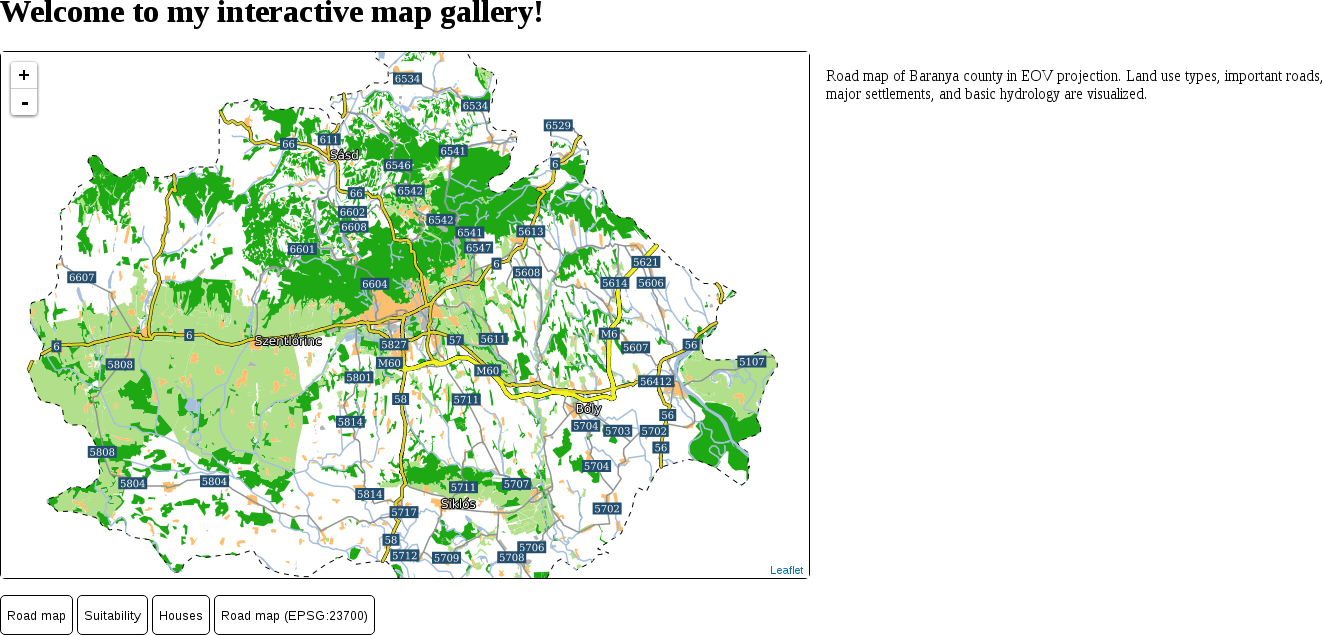

Appendix shows additional information and interesting use cases of the learned material through images and short descriptions.

For this book, you will need to have a computer with mid-class computing capabilities. As the open source GIS software is not that demanding, you don't have to worry about your hardware specification when running the software, although some of the raster processing tools will run pretty long (about 5-10 minutes) on slower machines.

What you need to take care of is that you have administrator privileges on the machine you are using, or the software is set up correctly by an administrator. If you don't have administrator privileges, you need to write the privilege at least to the folder used by the web server to serve content.

The aim of this book is to carry on this trend and demonstrate how even advanced spatial analysis is convenient with an open source product, and how this software is a capable competitor of proprietary solutions. The examples from which you will learn how to harness the power of the capable GIS software, QGIS; the powerful spatial ORDBMS (object-relational database management system), PostGIS; and the user-friendly geospatial server, GeoServer are aimed at IT professionals looking for cheap alternatives to costly proprietary GIS solutions with or without basic GIS training.

On the other hand, anyone can learn the basics of these great open source products from this practical guide. If you are a decision maker looking for easily producible results, a CTO looking for the right software, or a student craving for an easy-to-follow guide, it doesn't matter. This book presents you the bare minimum of the GIS knowledge required for effective work with spatial data, and thorough but easy-to-follow examples for utilizing open source software for this work.

In this book, you will find a number of text styles that distinguish between different kinds of information. Here are some examples of these styles and an explanation of their meaning.

Code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, and user input are shown as follows: "It uses the * wildcard for selecting everything from the table named table, where the content of the column named column matches value."

A block of code is set as follows:

SELECT ST_Buffer(geom, 200) AS geom

FROM spatial.roads r

WHERE r.fclass LIKE 'motorway%' OR r.fclass LIKE 'primary%';

Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

update-alternatives --config java

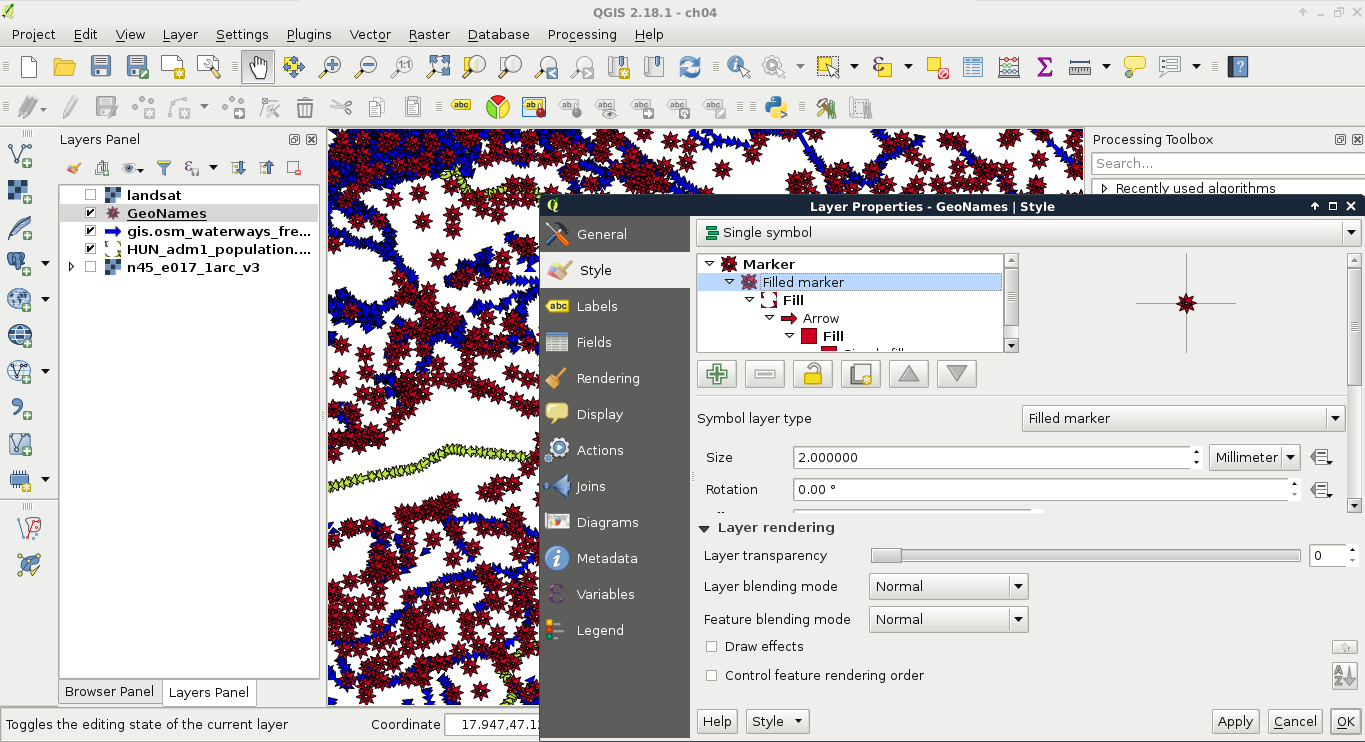

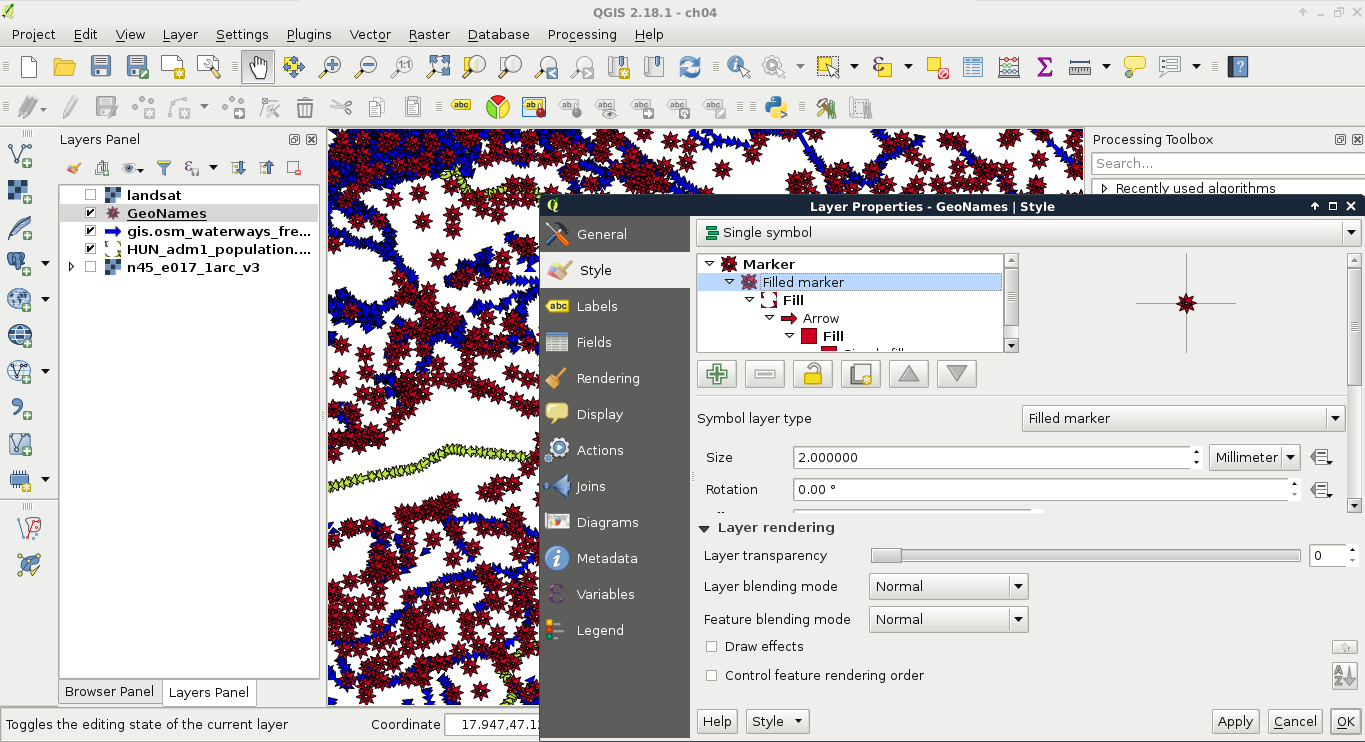

New terms and important words are shown in bold. Words that you see on the screen, for example, in menus or dialog boxes, appear in the text like this: "If we open the Properties window of a vector layer and navigate to the Style tab, we can see the Single symbol method applied to the layer."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome. Let us know what you think about this book—what you liked or disliked. Reader feedback is important for us as it helps us develop titles that you will really get the most out of.

To send us general feedback, simply e-mail feedback@packtpub.com, and mention the book's title in the subject of your message.

If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, see our author guide at www.packtpub.com/authors.

Now that you are the proud owner of a Packt book, we have a number of things to help you to get the most from your purchase.

You can download the example code files for this book from your account at http://www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit http://www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files e-mailed directly to you.

You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

The code bundle for the book is also hosted on GitHub at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/Practical-GIS. We also have other code bundles from our rich catalog of books and videos available at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/. Check them out!

We also provide you with a PDF file that has color images of the screenshots/diagrams used in this book. The color images will help you better understand the changes in the output. You can download this file from https://www.packtpub.com/sites/default/files/downloads/PracticalGIS_ColorImages.pdf.

Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you find a mistake in one of our books—maybe a mistake in the text or the code—we would be grateful if you could report this to us. By doing so, you can save other readers from frustration and help us improve subsequent versions of this book. If you find any errata, please report them by visiting http://www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details of your errata. Once your errata are verified, your submission will be accepted and the errata will be uploaded to our website or added to any list of existing errata under the Errata section of that title.

To view the previously submitted errata, go to https://www.packtpub.com/books/content/support and enter the name of the book in the search field. The required information will appear under the Errata section.

Piracy of copyrighted material on the Internet is an ongoing problem across all media. At Packt, we take the protection of our copyright and licenses very seriously. If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, please provide us with the location address or website name immediately so that we can pursue a remedy.

Please contact us at copyright@packtpub.com with a link to the suspected pirated material.

We appreciate your help in protecting our authors and our ability to bring you valuable content.

If you have a problem with any aspect of this book, you can contact us at questions@packtpub.com, and we will do our best to address the problem.

The development of open source GIS technologies has reached a state where they can seamlessly replace proprietary software in the recent years. They are convenient, capable tools for analyzing geospatial data. They offer solutions from basic analysis to more advanced, even scientific, workflows. Moreover, there are tons of open geographical data out there, and some of them can even be used for commercial purposes. In this chapter, we will acquaint ourselves with the open source software used in this book, install and configure them with an emphasis on typical pitfalls, and learn about some of the most popular sources of open data out there.

In this chapter, we will cover the following topics:

Before jumping into the installation process, let's discuss geographic information systems (GIS) a little bit. GIS is a system for collecting, manipulating, managing, visualizing, analyzing, and publishing spatial data. Although these functionalities can be bundled in a single software, by definition, GIS is not a software, it is rather a set of functionalities. It can help you to make better decisions, and to get more in-depth results from data based on their spatial relationships.

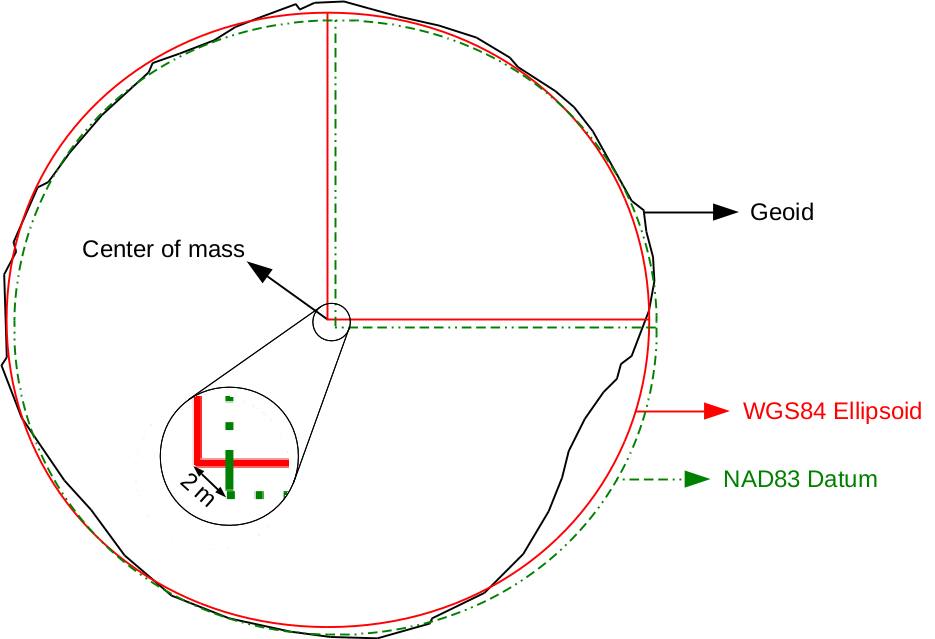

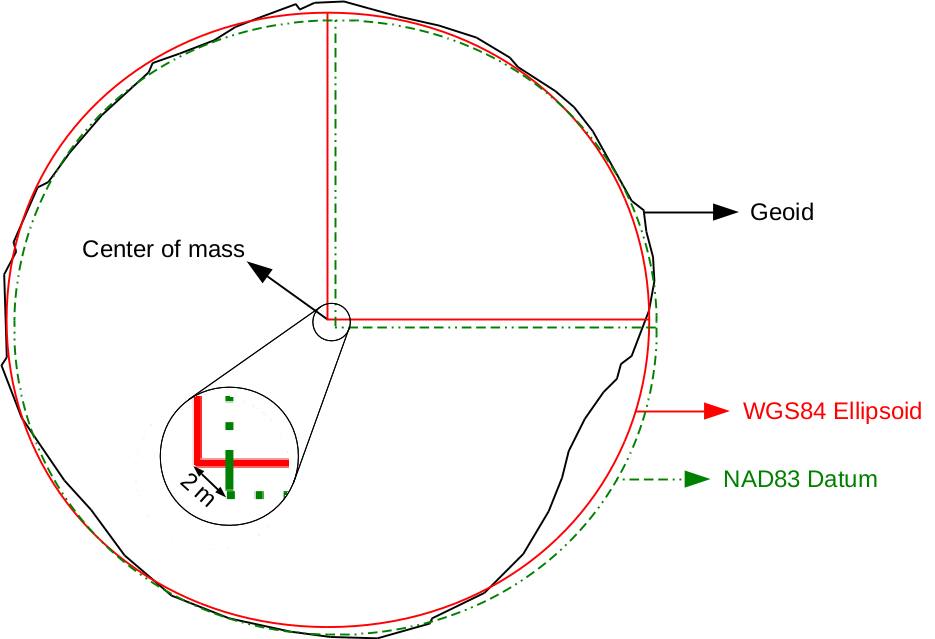

The most important part of the former definition is spatial data. GIS handles data based on their locations in a coordinate reference system. This means, despite GIS mainly being used for handling and processing geographical data (data that can be mapped to the surface of Earth), it can be used for anything with dimensions. For example, a fictional land like Middle-Earth, the Milky Way, the surface of Mars, the human body, or a single atom. The possibilities are endless; however, for most of them, there are specialized tools that are more feasible to use.

The functionalities of a GIS outline the required capabilities of a GIS expert. Experts need to be able to collect data either by surveying, accessing an other's measurements, or digitizing paper maps, just to mention a few methods. Collecting data is only the first step. Experts need to know how to manage this data. This functionality assumes knowledge not only in spatial data formats but also in database management. Some of the data just cannot fit into a single file. There can be various reasons behind this; for example, the data size or the need for more sophisticated reading and writing operations. Experts also need to visualize, manipulate, and analyze this data. This is the part where GIS clients come in, as they have the capabilities to render, edit, and process datasets. Finally, experts need to be able to create visualizations from the results in order to show them, verify decisions, or just help people interpreting spatial patterns. This phase was traditionally done via paper maps and digital maps, but nowadays, web mapping is also a very popular means of publishing data.

From these capabilities, we will learn how to access data from freely available data sources, store and manage them in a database, visualize and analyze them with a GIS client, and publish them on the Web.

Most of the software used in this book is platform-dependent; therefore, they have different ways of getting installed on different operating systems. I assume you have enough experience with your current OS to install software, and thus, we will focus on the possible product-related pitfalls in a given OS. We will cover the three most popular operating systems--Linux, Windows, and macOS. If you don't need the database or the web stack, you can skip the installation of the related software and jump through the examples using them.

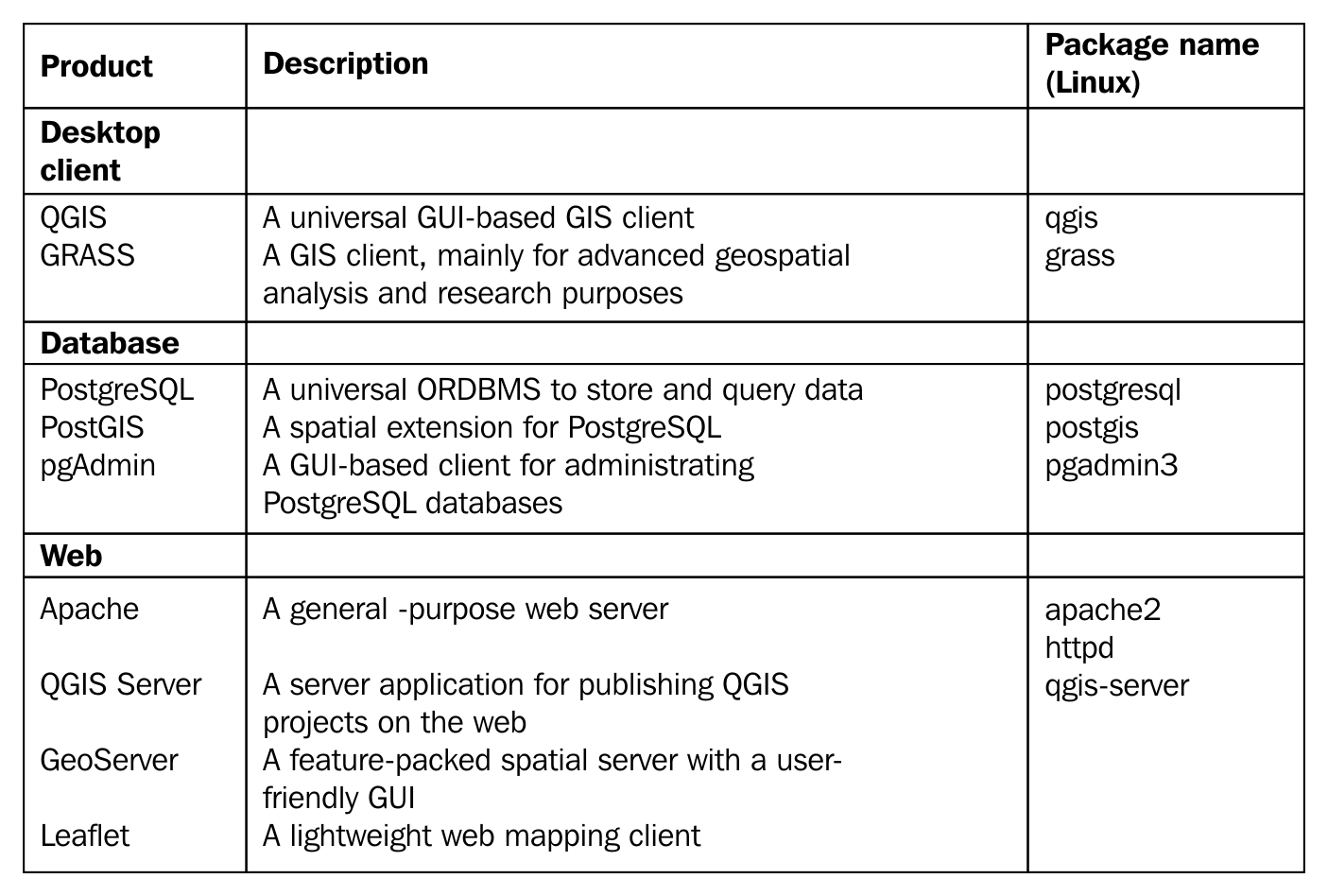

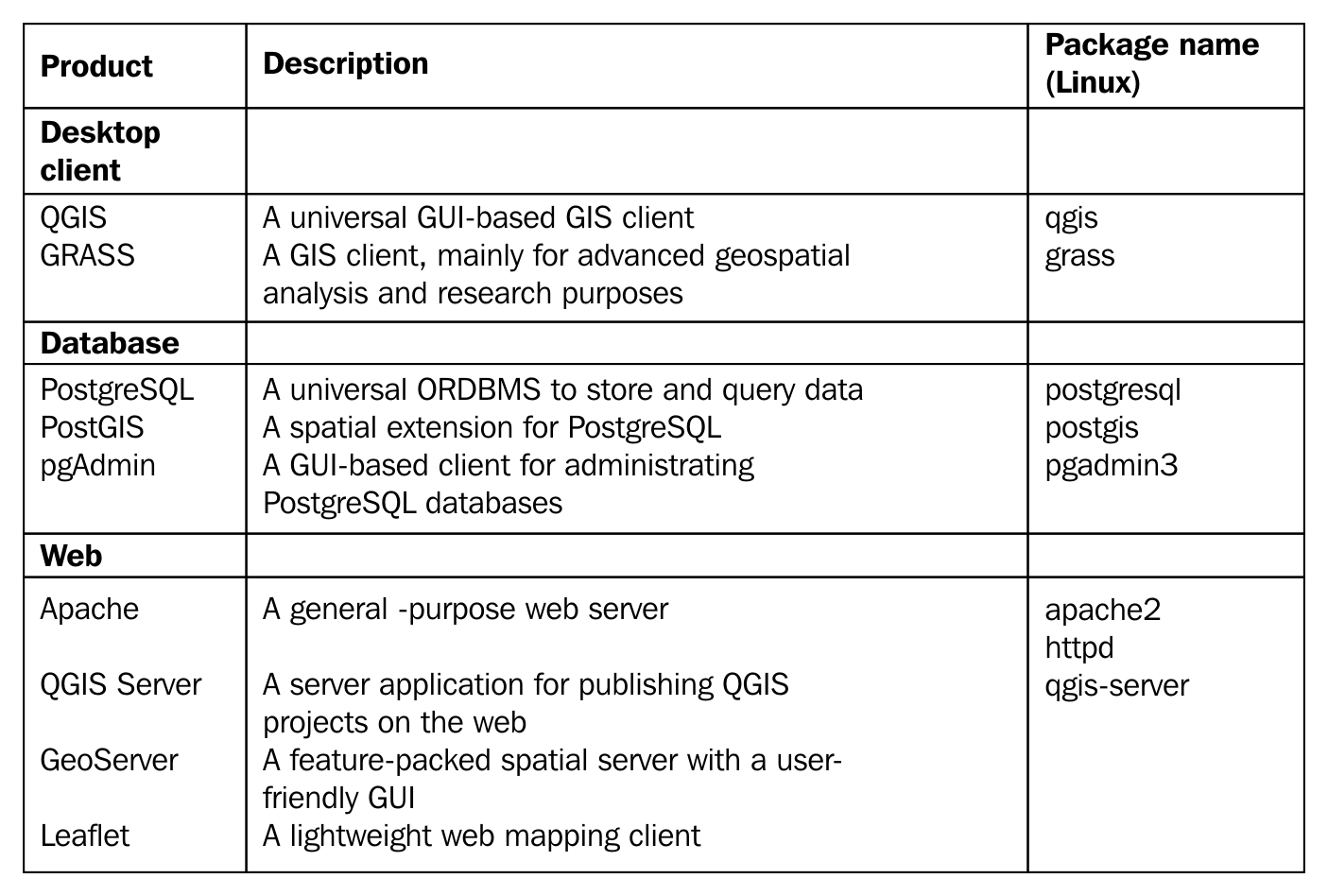

The list of the software stack used in this book can be found in the following thematically grouped table:

Installing the packages on Linux distributions is pretty straightforward. The dependencies are installed with the packages, when there are any. We only have to watch out for three things prior to installing the packages. First of all, the package name of the Apache web server can vary between different distributions. On distros using RPM packages (for example--Fedora, CentOS, and openSUSE), it is called httpd, while on the ones using DEB packages (for example--Debian and Ubuntu), it is called apache2. On Arch Linux, it is simply called apache.

The second consideration is related to distributions which do not update their packages frequently, like Debian. GeoServer has a hard dependency of a specific JRE (Java Runtime Environment). We must make sure we have it installed and configured as the default. We will walk through the Debian JRE installation process as it is the most popular Linux distribution with late official package updates. Debian Jessie, the latest stable release of the OS when writing these lines, is packed with OpenJDK 7, while GeoServer 2.11 requires JRE 8:

update-alternatives --config java

The last consideration before installing the packages is related to the actual version of QGIS. Most of the distributions offer the latest version in a decent time after release; however, some of them like Debian do not. For those distros, we can use QGIS's repository following the official guide at http://www.qgis.org/en/site/forusers/alldownloads.html.

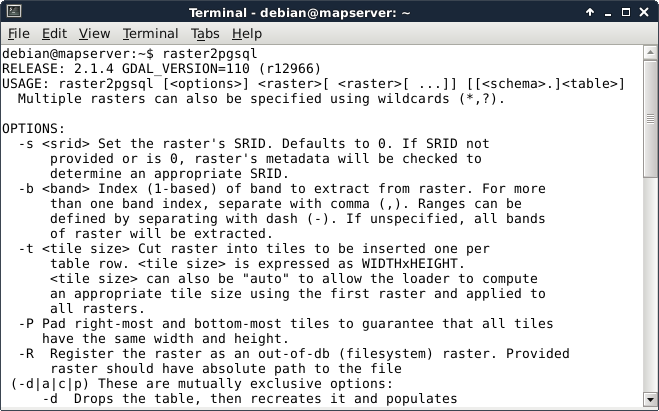

After all things are set, we can proceed and install the required packages. The order should not matter. If done, let's take a look at GeoServer, which doesn't offer Linux packages to install. It offers two methods for Linux: a WAR for already installed Java servlets (such as Apache Tomcat), and a self-containing platform independent binary. We will use the latter as it's easier to set up:

cd <geoserver's folder>/bin

./startup.sh

Installing the required software on Windows only requires a few installers as most of the packages are bundled into the OSGeo4W installer.

Don't worry if you end up with no solutions, we will concentrate on GeoServer, which runs perfectly on Windows. Just make sure Apache is installed and working (i.e. http://localhost returns a blank page or the OSGeo4W default page), as we will need it later.

Installing the software on macOS could be the most complicated of all (because of GRASS). However, thanks to William Kyngesburye, the compiled version of QGIS already contains a copy of GRASS along with other GIS software used by QGIS. In order to install QGIS, we have to download the disk image from http://www.kyngchaos.com/software/qgis.

PostgreSQL and PostGIS are also available from the same site, you will see the link on the left sidebar. pgAdmin, on the other hand, is available from another source: https://www.pgadmin.org/download/pgadmin-4-macos/. Finally, the GeoServer macOS image can be downloaded from http://geoserver.org/release/stable/, while its dependency of Java 8 can be downloaded from https://www.java.com/en/download/.

The only thing left is configuring the QGIS Server. As the OS X and macOS operating systems are shipped with an Apache web server, we don't have to install it. However, we have to make some configurations manually due to the lack of the FastCGI Apache module, on which QGIS Server relies. This configuration can be made based on the official guide at http://hub.qgis.org/projects/quantum-gis/wiki/QGIS_Server_Tutorial.

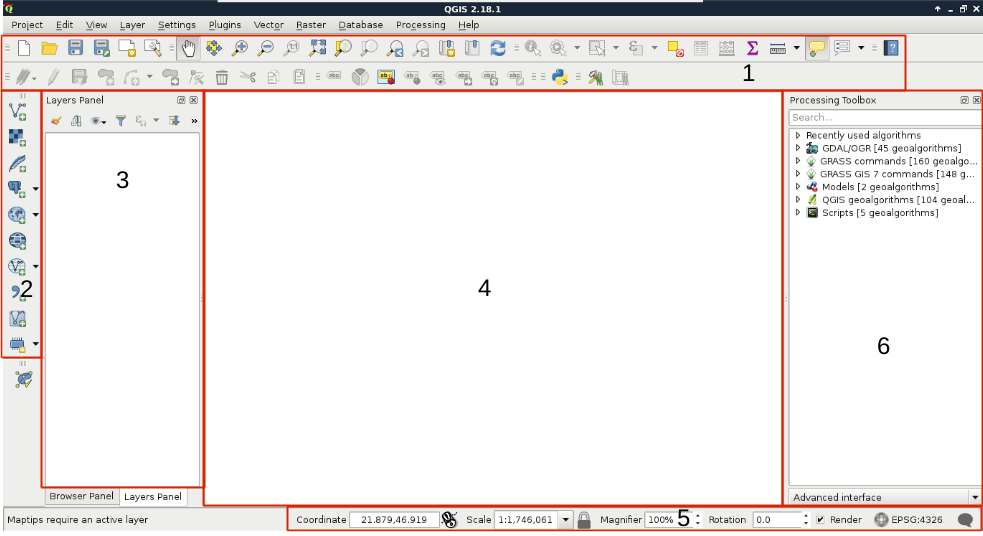

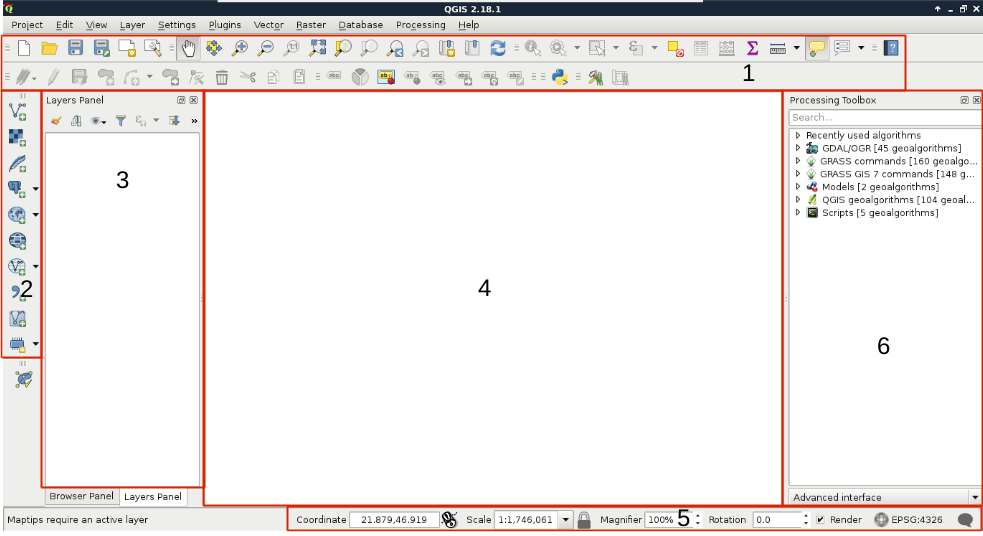

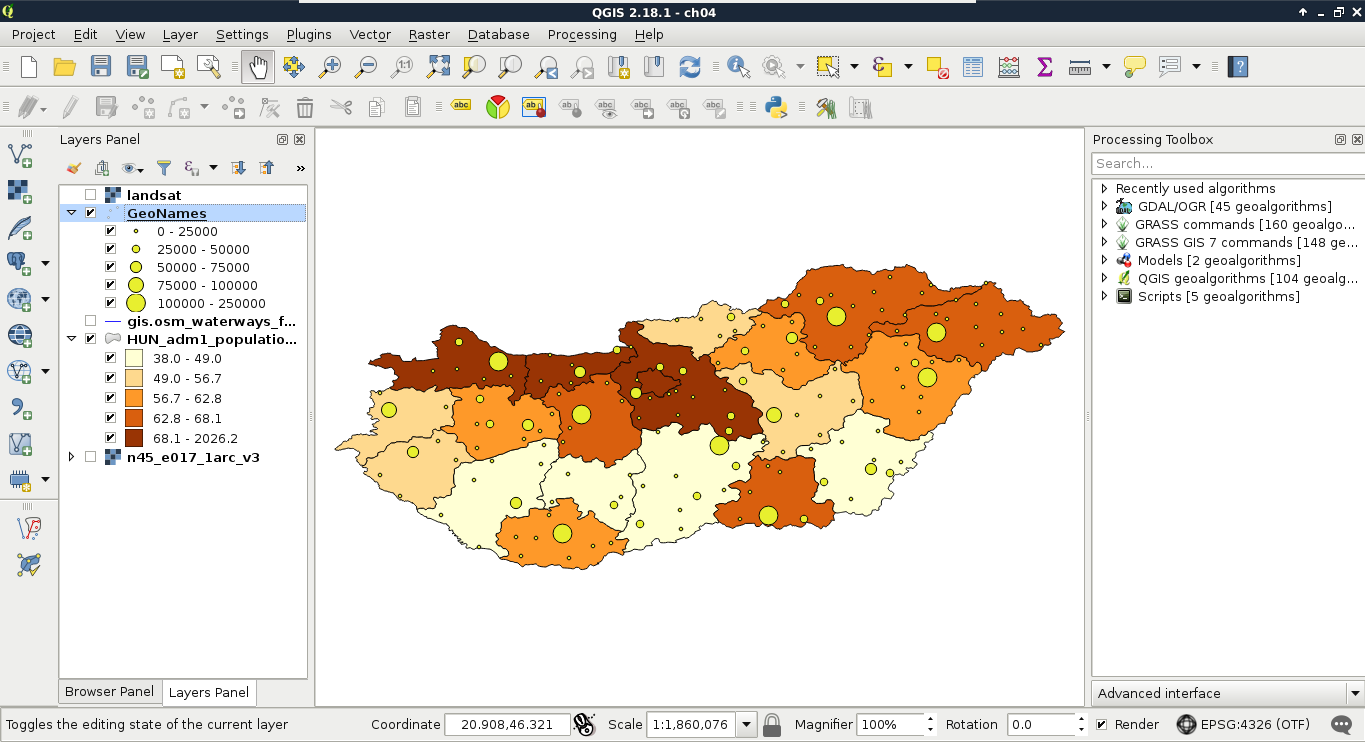

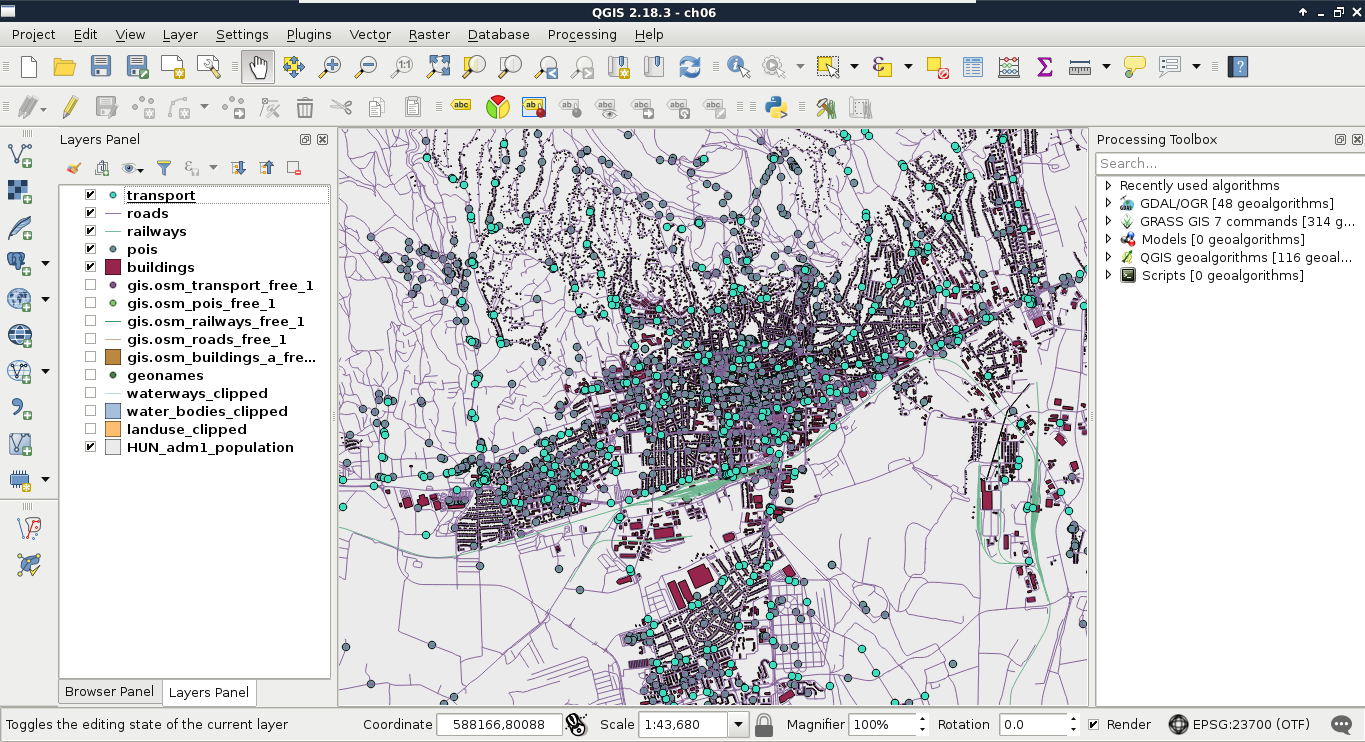

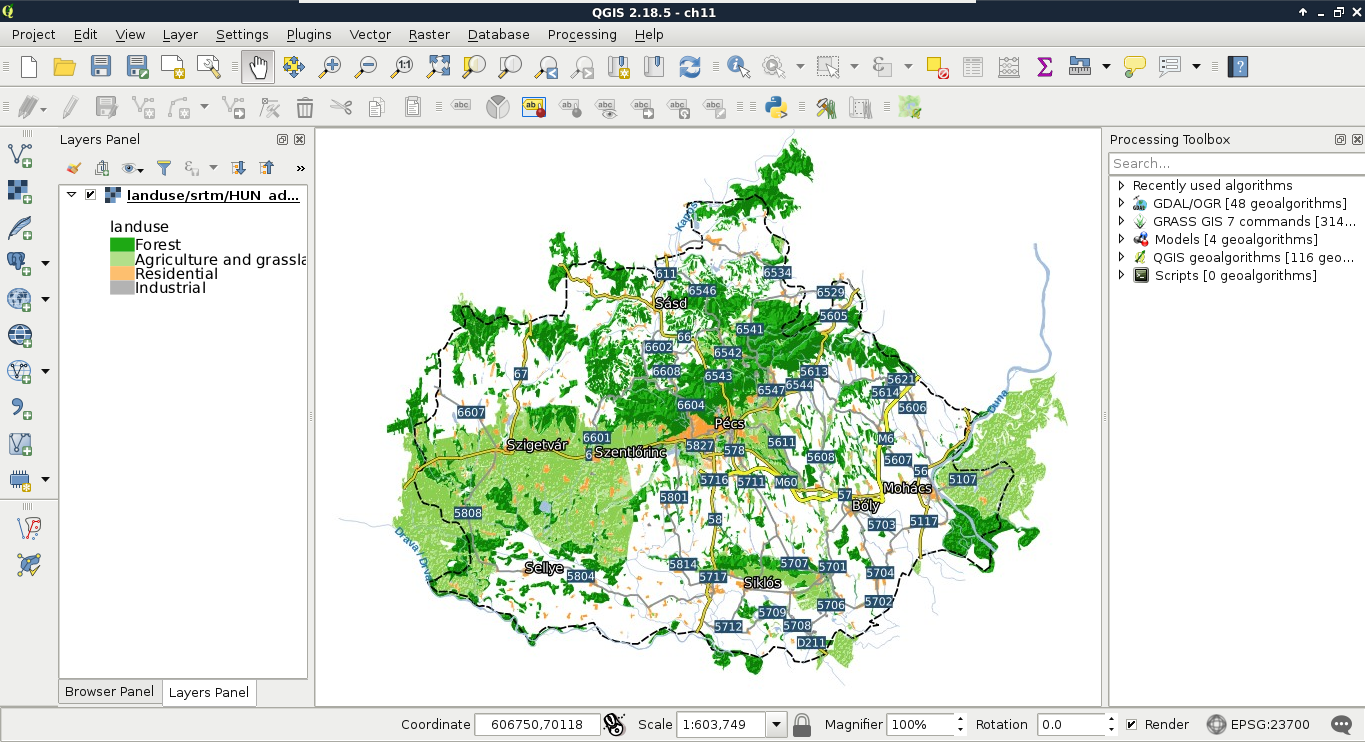

Congratulations! You're through the hardest part of this chapter. The following step is to make some initial configurations on the installed software to make them ready to use when we need them. First of all, let's open QGIS. At first glance, it has a lot of tools. However, most of them are very simple and self-explanatory. We can group the parts of the GUI as shown in the following image:

We can describe the distinct parts of the QGIS GUI as follows:

The only thing we will do now without having any data to display, is customizing the GUI. Let's click on Settings and choose the Options menu. In the first tab called General, we can see some styles to choose from. Don't forget to restart QGIS every time you choose a new style.

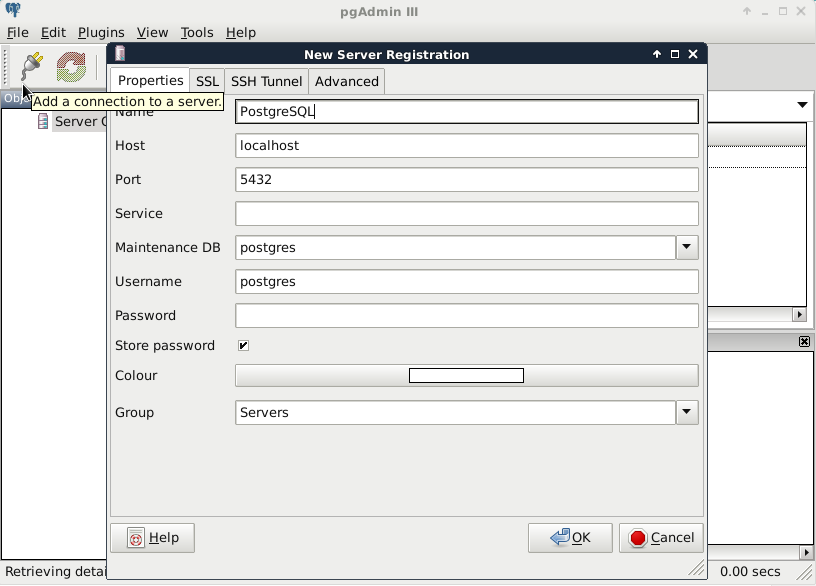

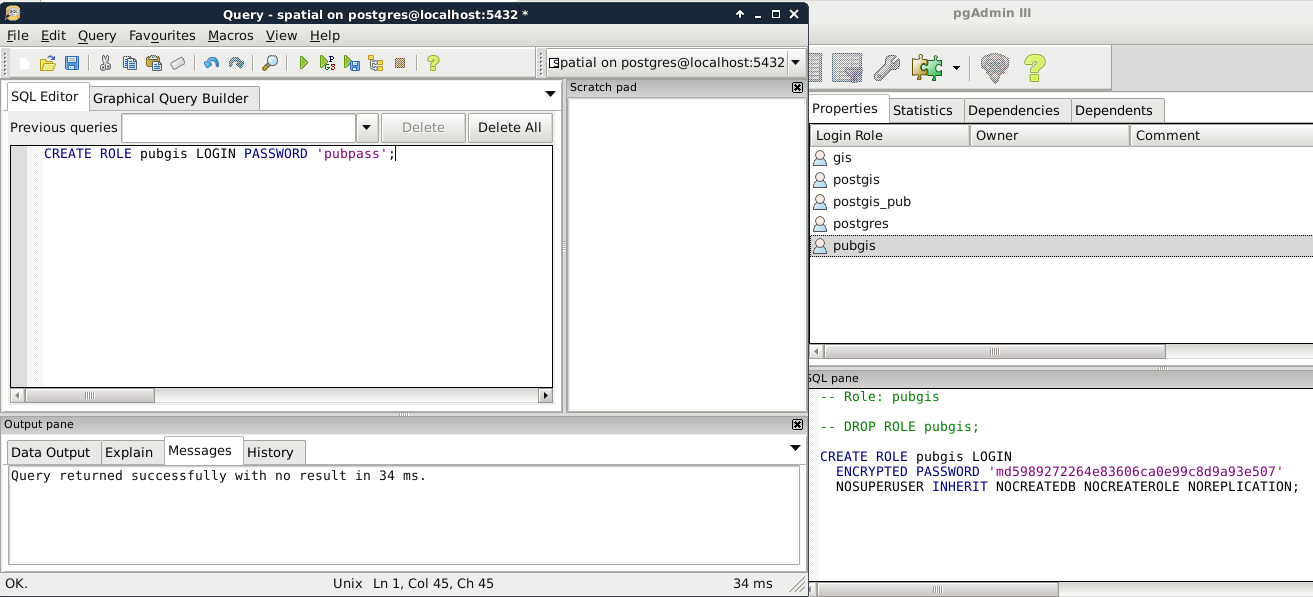

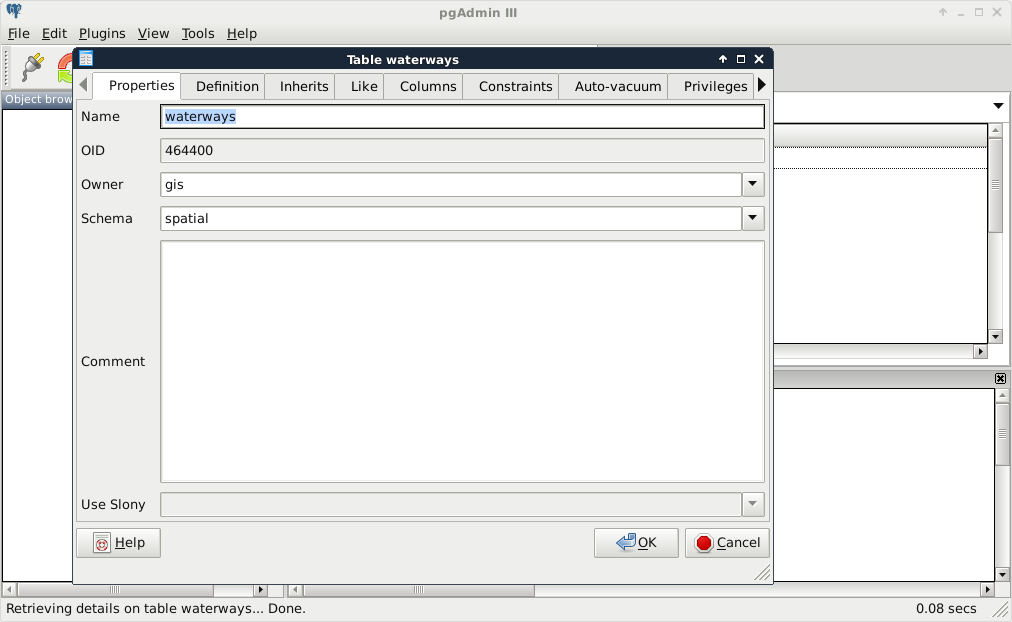

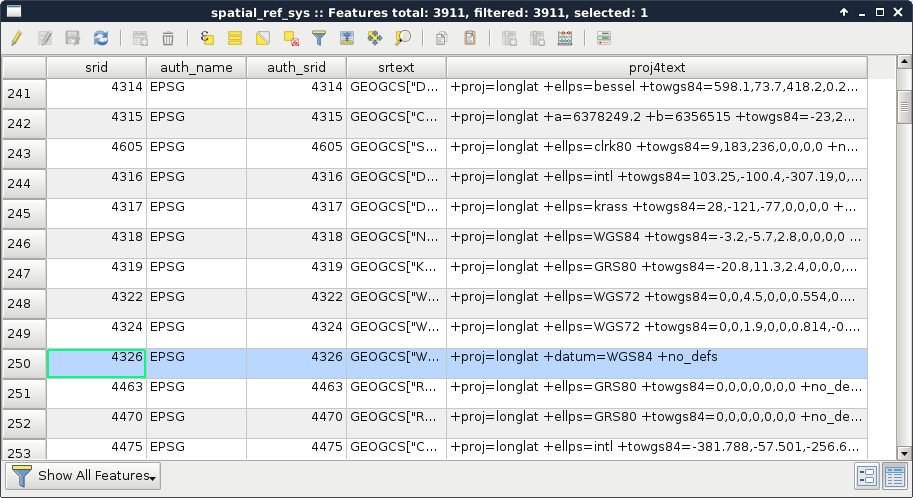

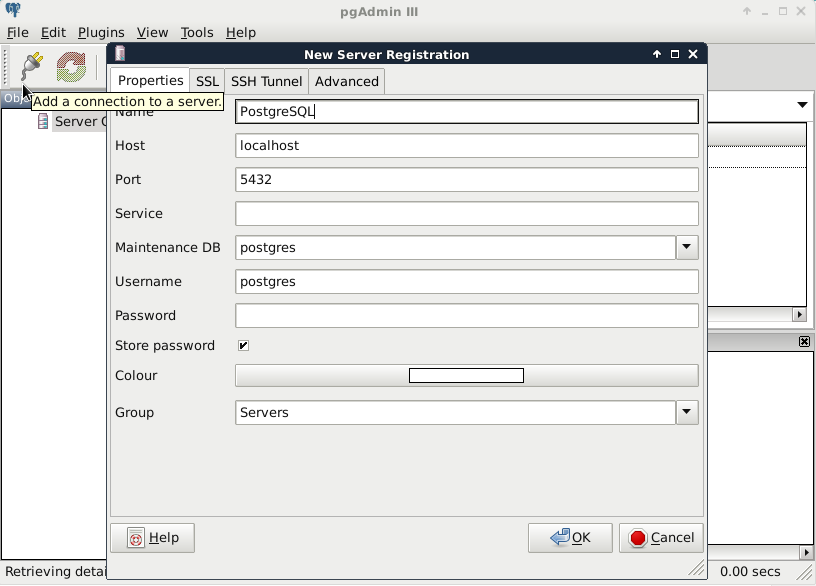

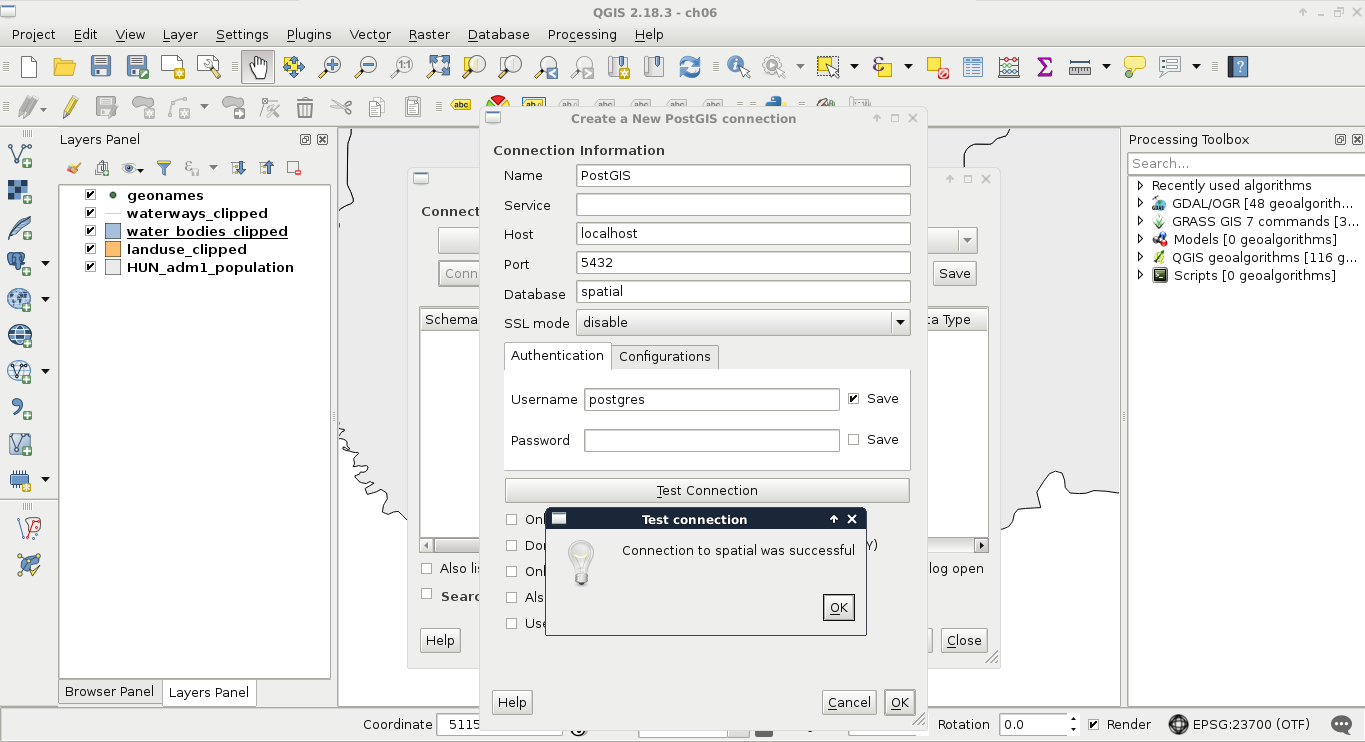

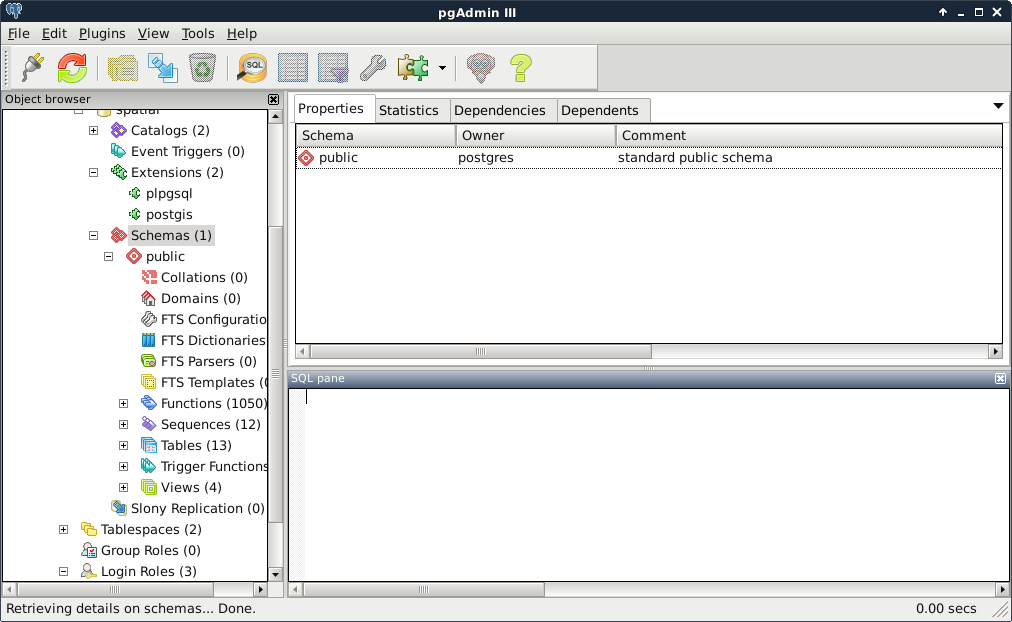

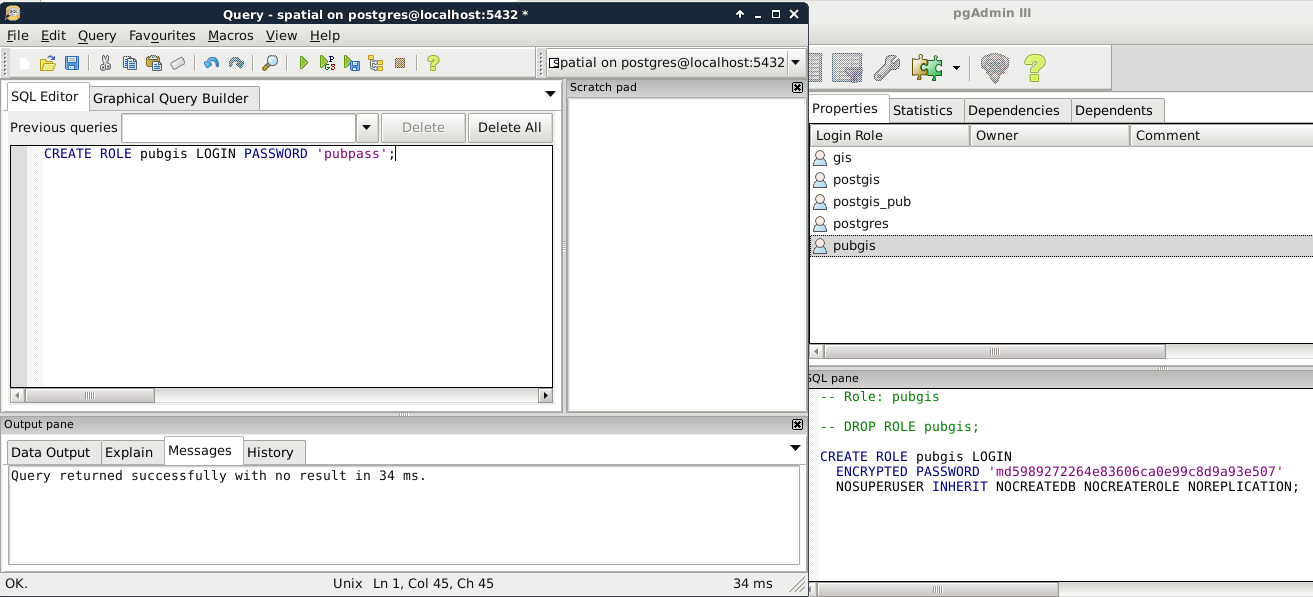

The next piece of software we look at is PostGIS via pgAdmin. If we open pgAdmin, the least we will see is an empty Server Groups item on the left panel. If this is the case, we have to define a new connection with the plug icon and fill out the form (Object | Create | Server in pgAdmin 4), as follows:

The Name can be anything we would like, it only acts as a named item in the list we can choose from. The Host, the Port, and the Username, on the other hand, have to be supplied properly. As we installed PostgreSQL locally, the host is 127.0.0.1, or simply localhost. As the default install comes with the default user postgres (we will refer to users as roles in the future due to the naming conventions of PostgreSQL), we should use that.

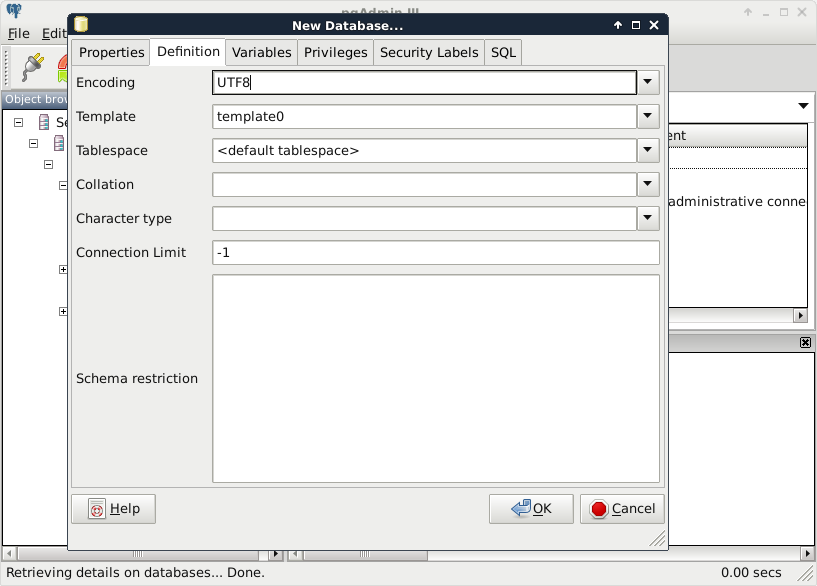

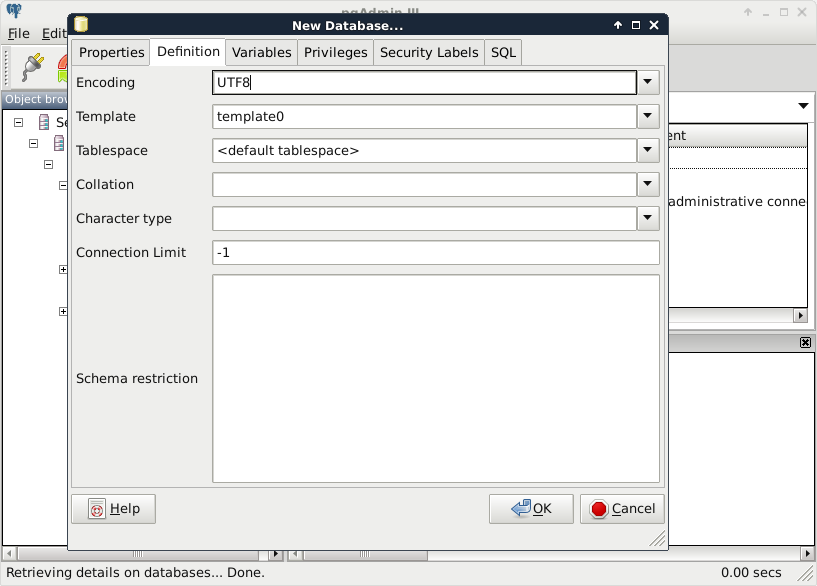

Upon connecting to the server, we can see a single database called postgres. This is the default database of the freshly installed PostgreSQL. As the next step, we create another database by right-clicking on Databases and selecting New Database. The database can be named as per our liking (I'm naming it spatial). The owner of the database should be the default postgres role in our case. The only other parameter we should define is the default character encoding of the database:

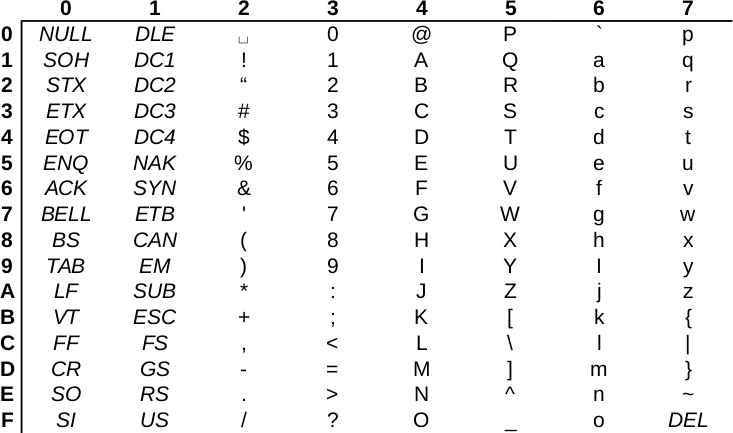

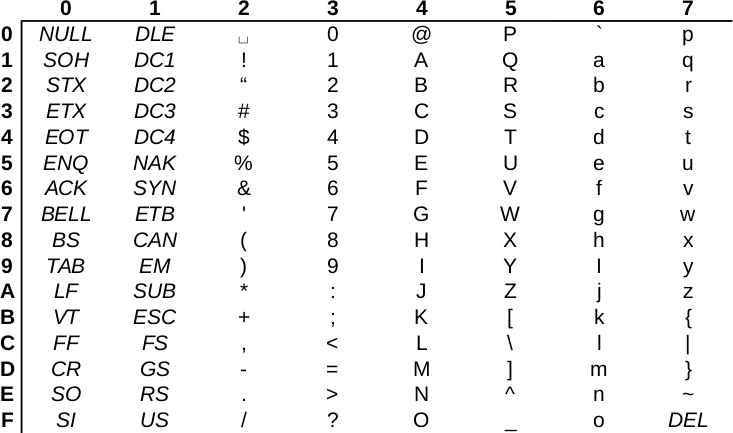

Choosing the template0 template is required as the default template's character encoding is a simple ASCII. You might be familiar with character encoding; however, refreshing our knowledge a little bit cannot hurt. In ASCII, every character is encoded on 8 bits, therefore, the number of characters which can be encoded is 28 = 256. Furthermore, in ASCII, only the first 7 bits (first 128 places) are reserved, the rest of them can be localized. The first 7 bits (in hexadecimal, 00-7F) can be visualized as in the following table. The italic values show control characters (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C0_and_C1_control_codes#C0_.28ASCII_and_derivatives.29):

Open source GIS software offer a very high degree of freedom. Their license types can differ; however, they are all permissive licenses. That means we can use, distribute, modify, and distribute the modified versions of the software. We can also use them in commercial settings and even sell the software if we can find someone willing to buy it (as long as we sell the software with the source code under the same license). The only restriction is for companies who would like to sell their software under a proprietary license using open source components. They simply cannot do that with most of the software, although some of the licenses permit this kind of use, too.

There is one very important thing to watch out for when we use open source software and data. If somebody contributes often years of work to the community, at least proper attribution can be expected. Most of the open source licenses obligate this right of the copyright holder; however, we must distinguish software from data. Most of the licenses of open source software require the adapted product to reproduce the same license agreement. That is, we don't have to attribute the used software in a work, but we must include the original license with the copyright holders' name when we create an application with them. Data, on the other hand, is required to be attributed when we use it in our work.

There are a few licenses which do not obligate us to give proper attribution. These licenses state that the creator of the content waives every copyright and gives the product to the public to use without any restrictions. Two of the most common licenses of this kind are the Unlicense, which is a software license, and the Creative Commons Public Domain, which is in the GIS world mostly used as a data license.

Now that we have our software installed and configured, we can focus on collecting some open source data. Data collecting (or data capture) is one of the key expertise of a GIS professional and it often covers a major part of a project budget. Surveying is expensive (for example, equipment, amortization, staff, and so on); however, buying data can also be quite costly. On the other hand, there is open and free data out there, which can drastically reduce the cost of basic analysis. It has some drawbacks, though. For example, the licenses are much harder to attune with commercial activity, because some of them are more restrictive.

There are two types of data collection. The first one is primary data collection, where we measure spatial phenomena directly. We can measure the locations of different objects with GPS, the elevation with radar or lidar, the land cover with remote sensing. There are truly a lot of ways of data acquisition with different equipment. The second type is secondary data collection, where we convert already existing data for our use case. A typical secondary data collection method is digitizing objects from paper maps. In this section, we will acquire some open source primary data.

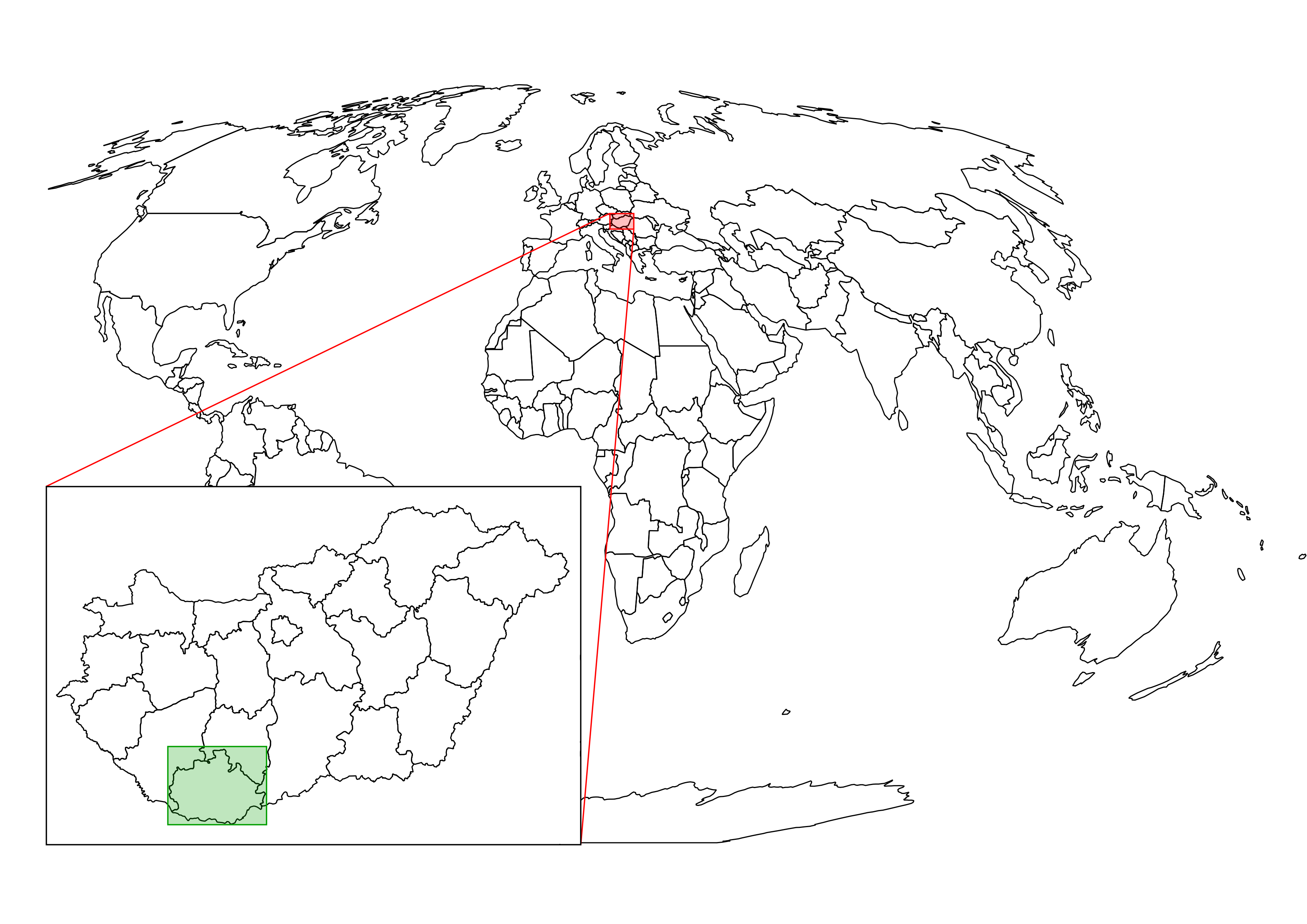

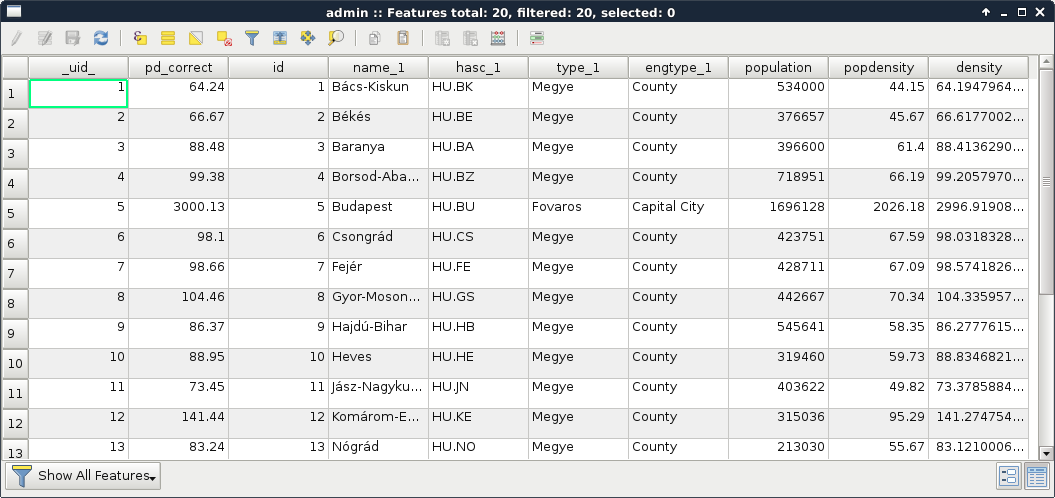

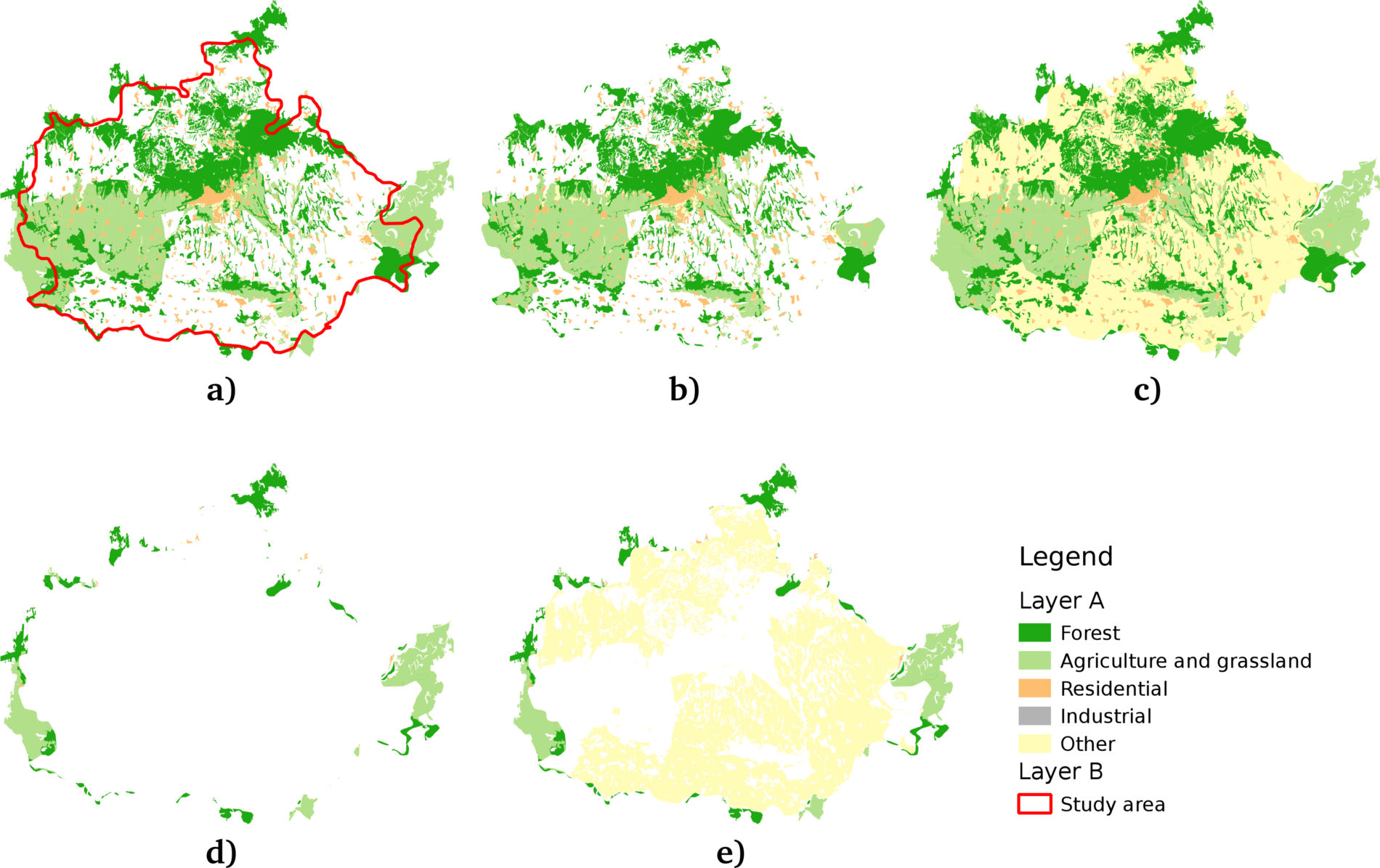

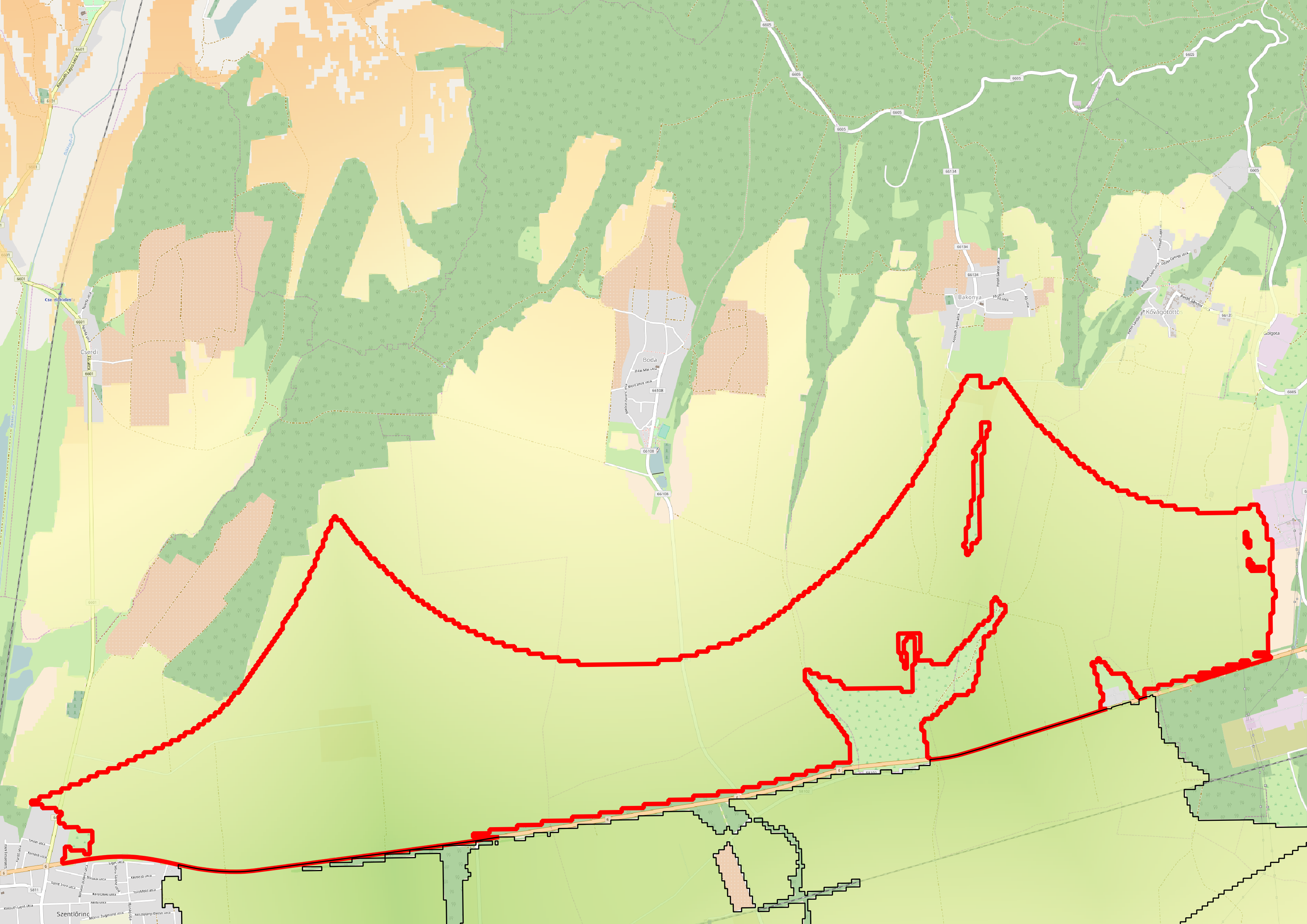

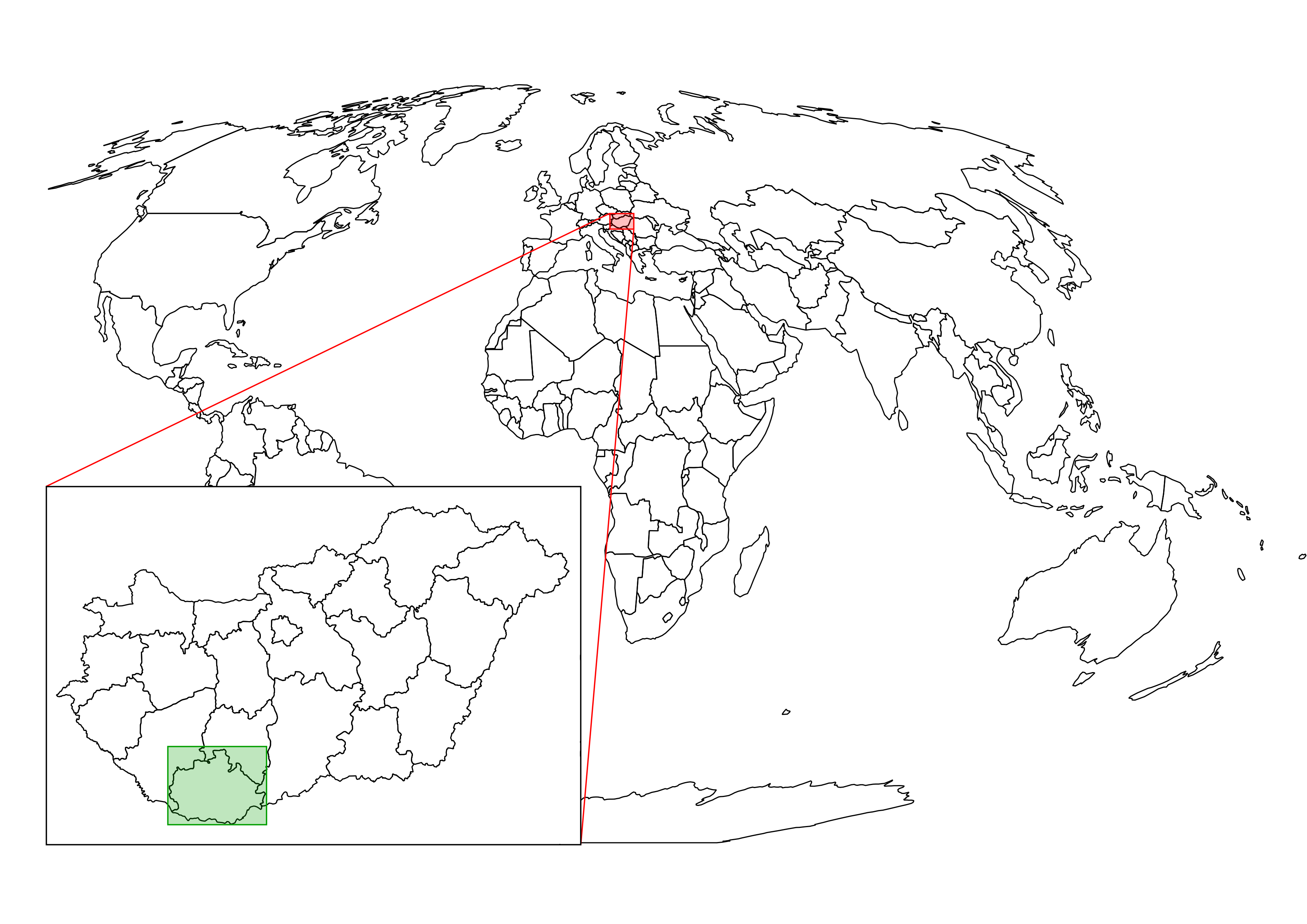

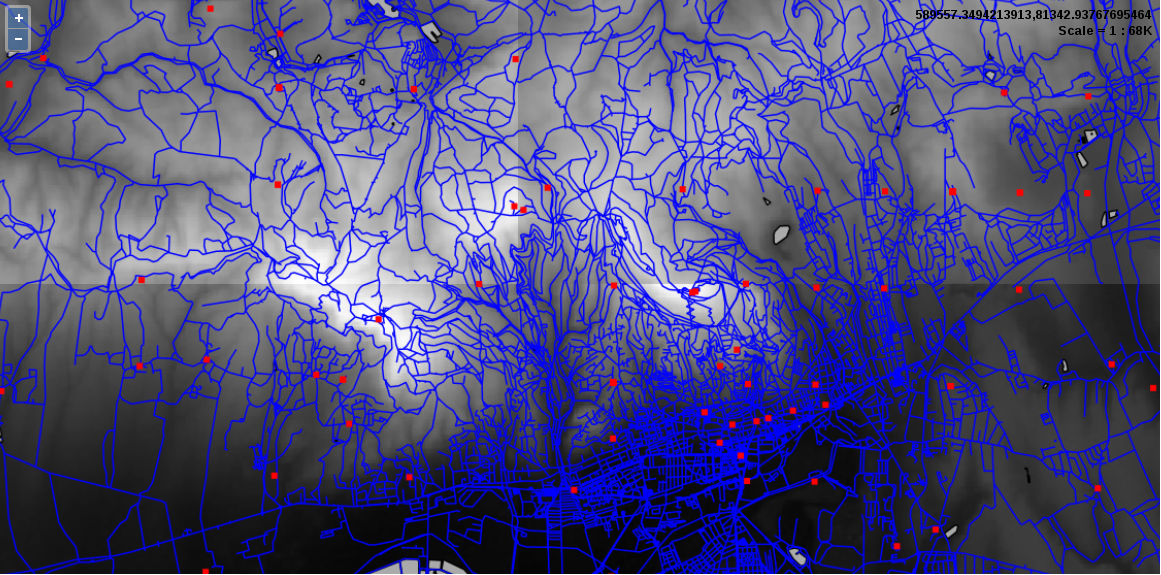

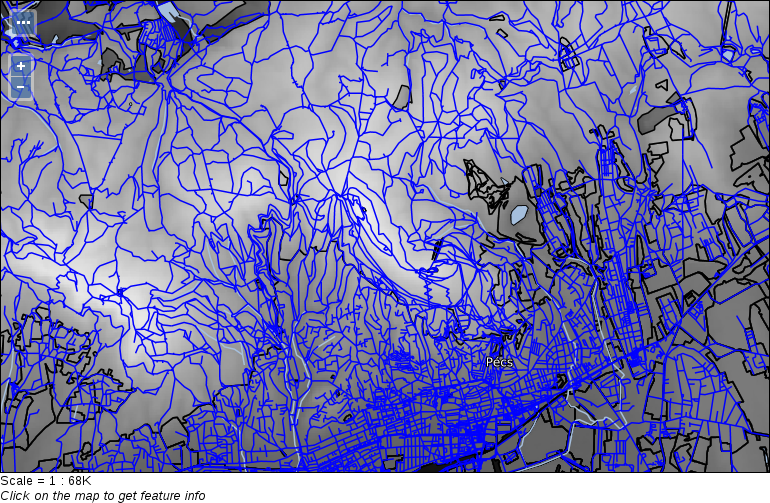

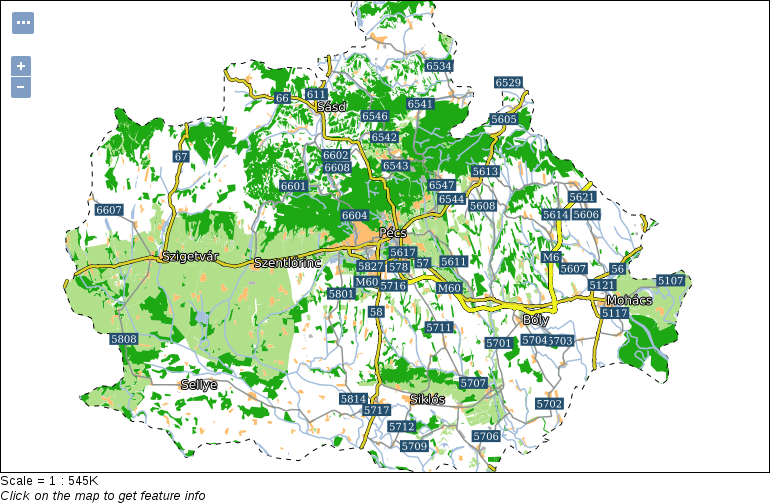

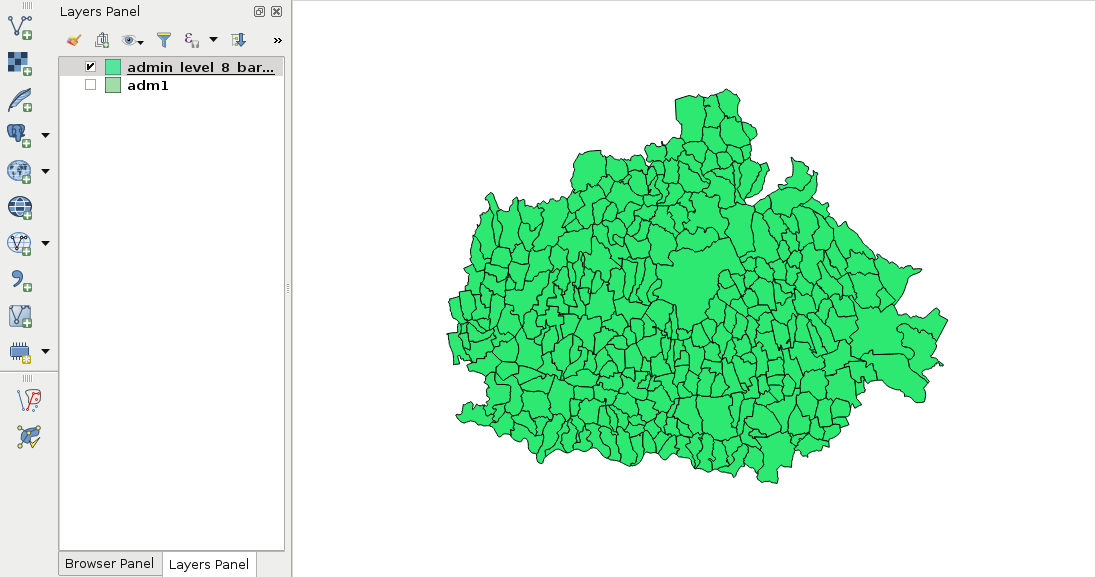

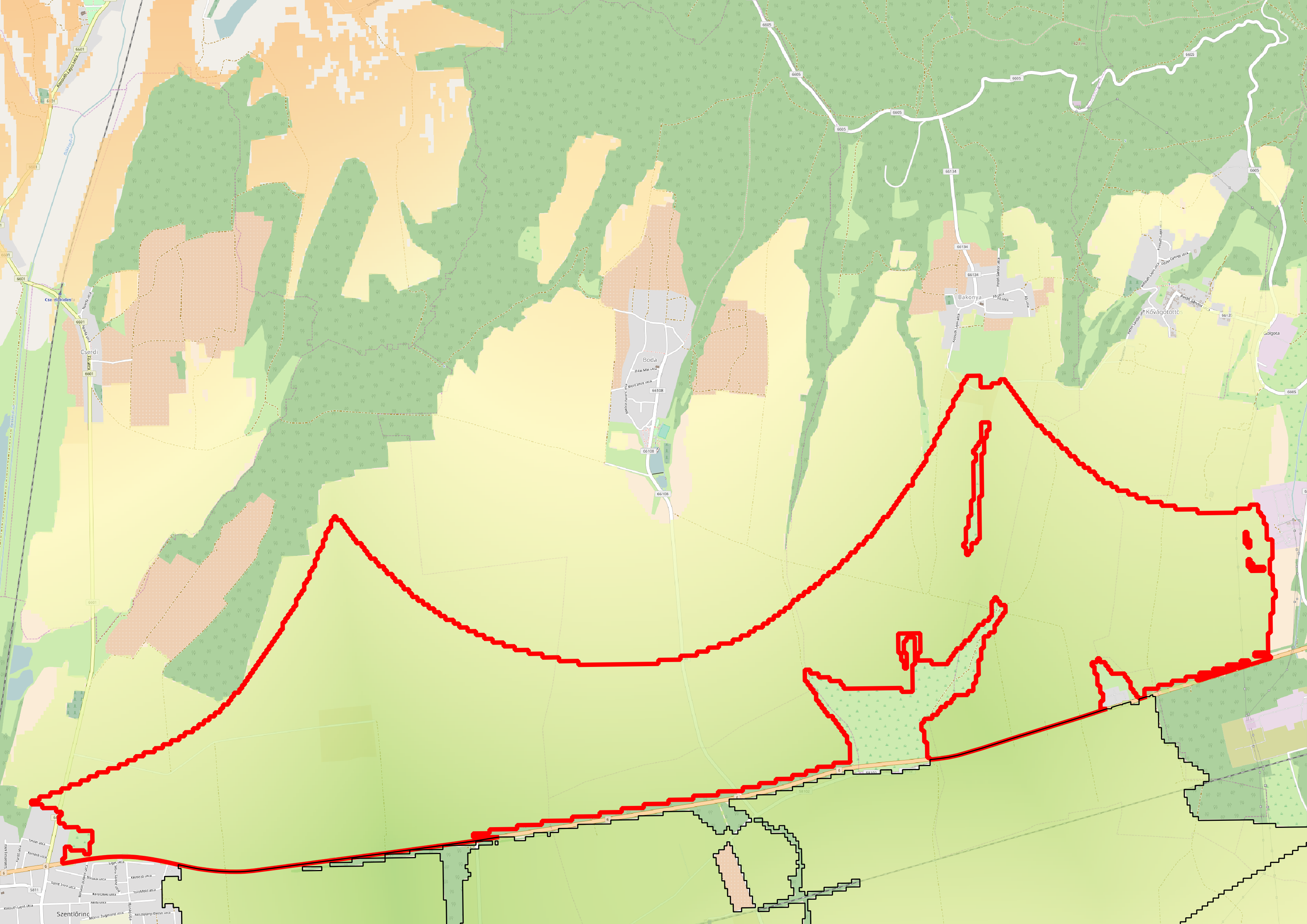

The only thing to consider is our study area. We should choose a relatively small administrative division, like a single county. For example, I'm choosing the county I live in as I'm quite familiar with it and it's small enough to make further analysis and visualization tasks fast and simple:

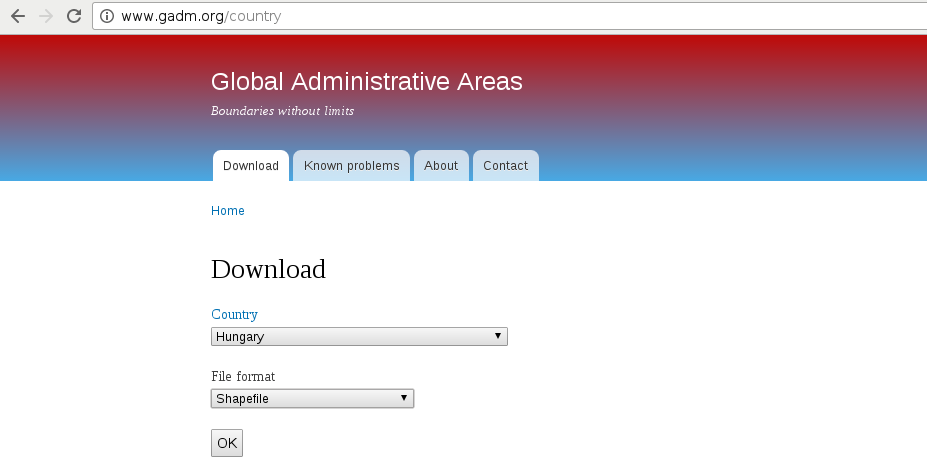

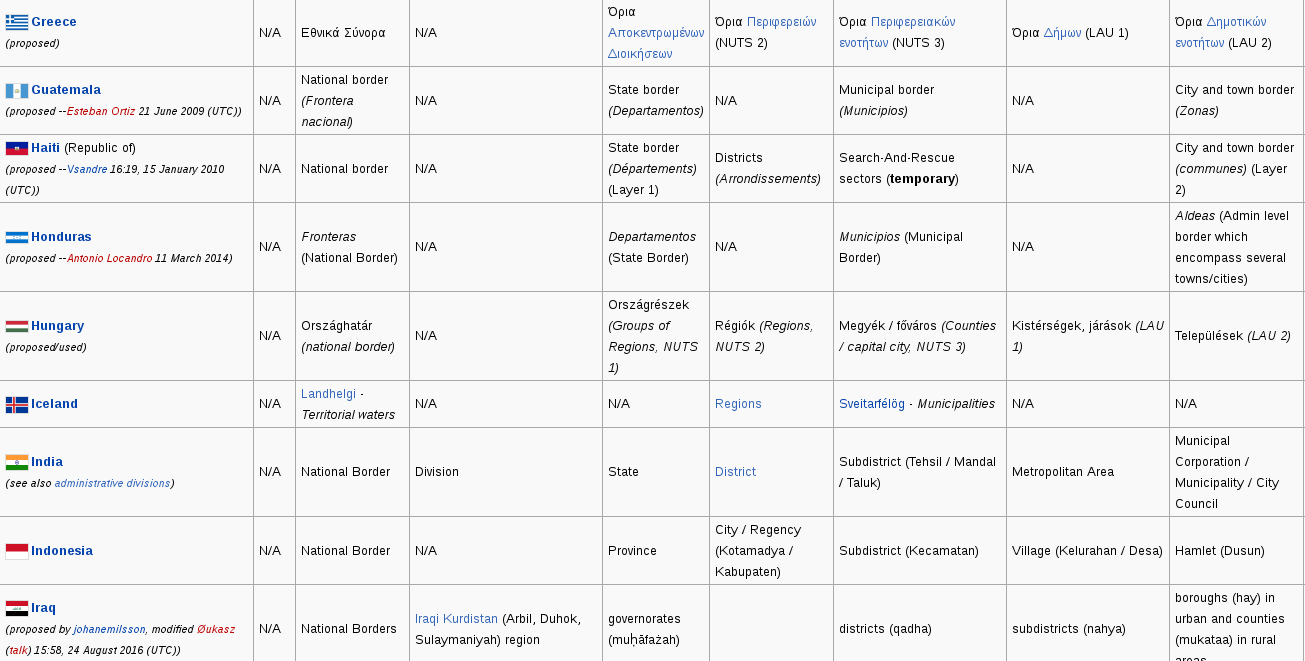

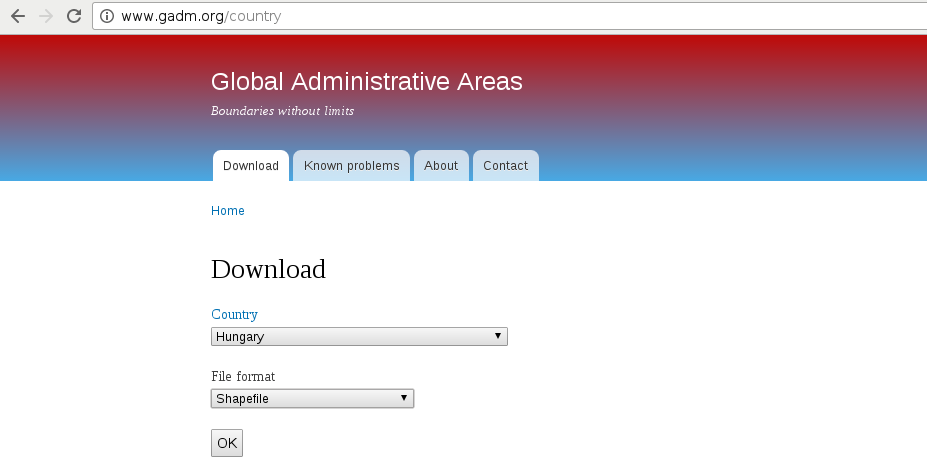

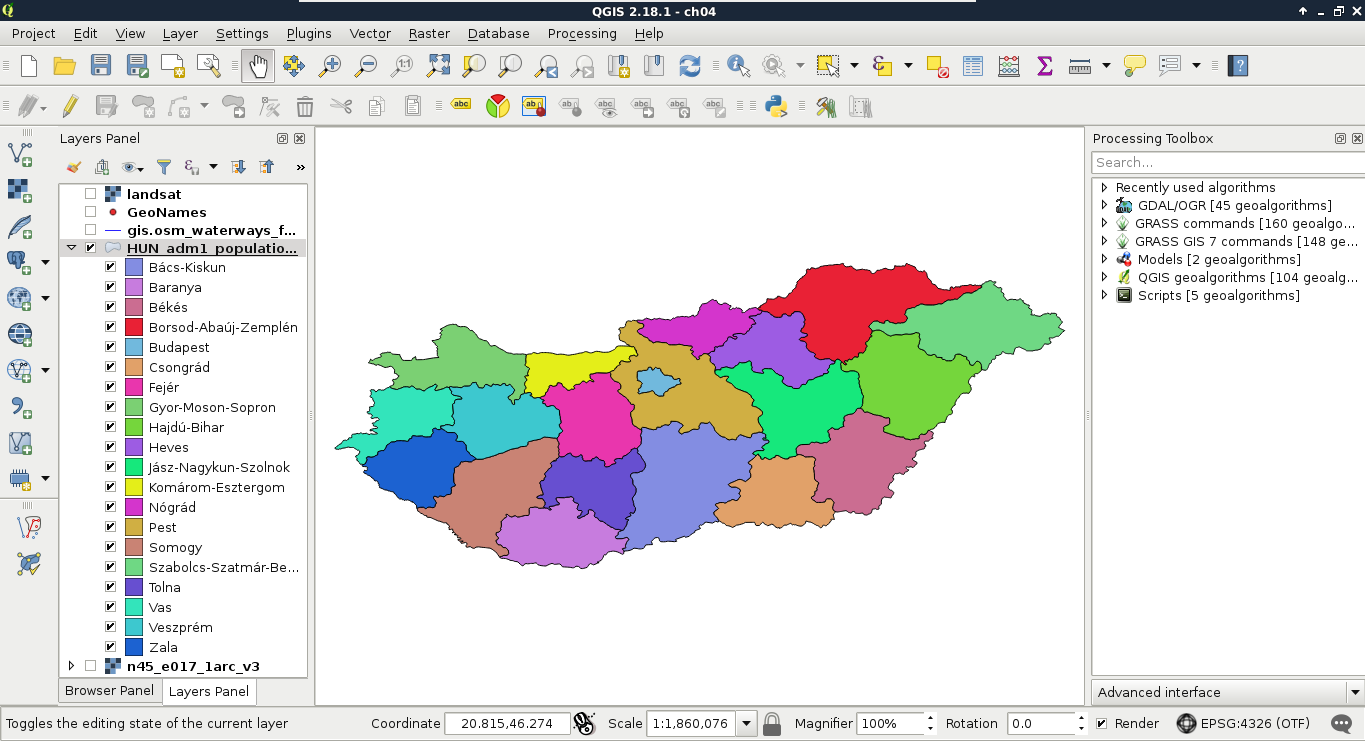

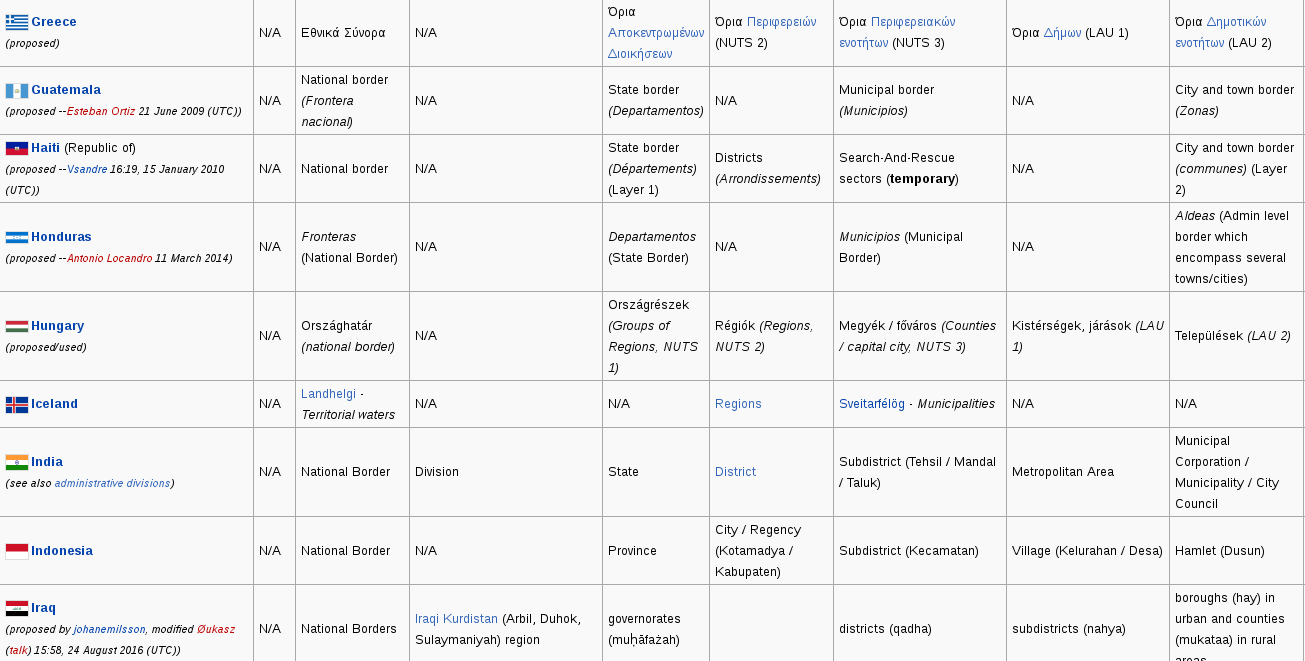

The first data we will download is the administrative boundaries of our country of choice. Open data for administrative divisions are easy to find for the first two levels, but it becomes more and more scarce for higher levels. The first level is always the countries' boundaries, while higher levels depend on the given country. There is a great source for acquiring the first three levels for every country in a fine resolution: GADM or Global Administrative Areas. We will talk about administration levels in more details in a later chapter. Let's download some data from http://www.gadm.org/country by selecting our study area, and the file format as Shapefile:

In the zipped archive, we will need the administrative boundaries, which contain our division of choice. If you aren't sure about the correct dataset, just extract everything and we will choose the correct one later.

The second vector dataset we download is the GeoNames archive for the country encasing our study area. GeoNames is a great place for finding data points. Every record in the database is a single point with a pair of coordinates and a lot of attribute data. Its most instinctive use case is for geocoding (linking names to locations). However, it can be a real treasure box for those who can link the rich attribute data to more meaningful objects. The country-level data dumps can be reached at http://download.geonames.org/export/dump/ through the countries' two-letter ISO codes.

GADM's license is very restrictive. We are free to use the downloaded data for personal and research purposes but we cannot redistribute it or use it in commercial settings. Technically, it isn't open source data as it does not give the four freedoms of using, modifying, redistributing the original version, and redistributing the modified version without restrictions. That's why the example dataset doesn't contain GADM's version of Luxembourg.

GeoNames has two datasets--a commercially licensed premium dataset and an open source one. The open source data can be used for commercial purposes without restrictions.

Data acquisition with instruments mounted on airborne vehicles is commonly called remote sensing. Mounting sensors on satellites is a common practice by space agencies (for example, NASA and ESA), and other resourceful companies. These are also the main source of open source data as both NASA and ESA grant free access to preprocessed data coming from these sensors. In this part of the book, we will download remote sensing data (often called imagery) from USGS's portal: Earth Explorer. It can be found at https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/. As the first step, we have to register an account in order to download data.

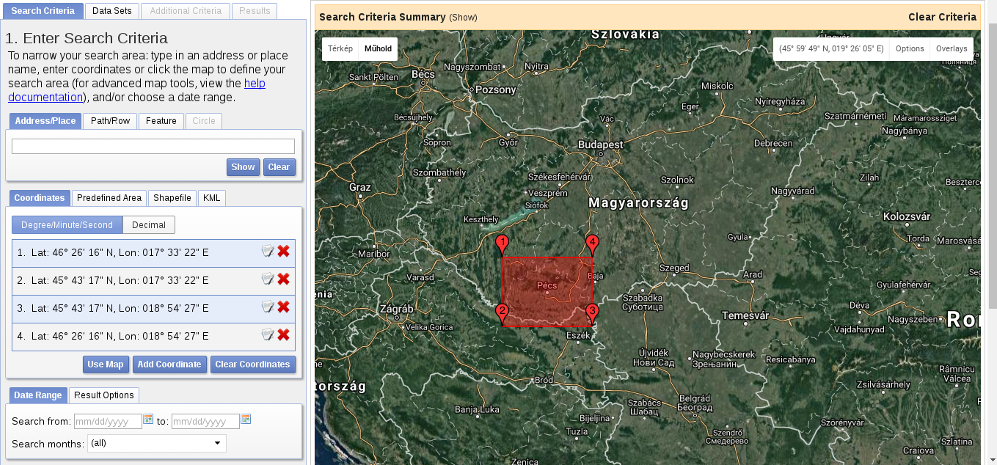

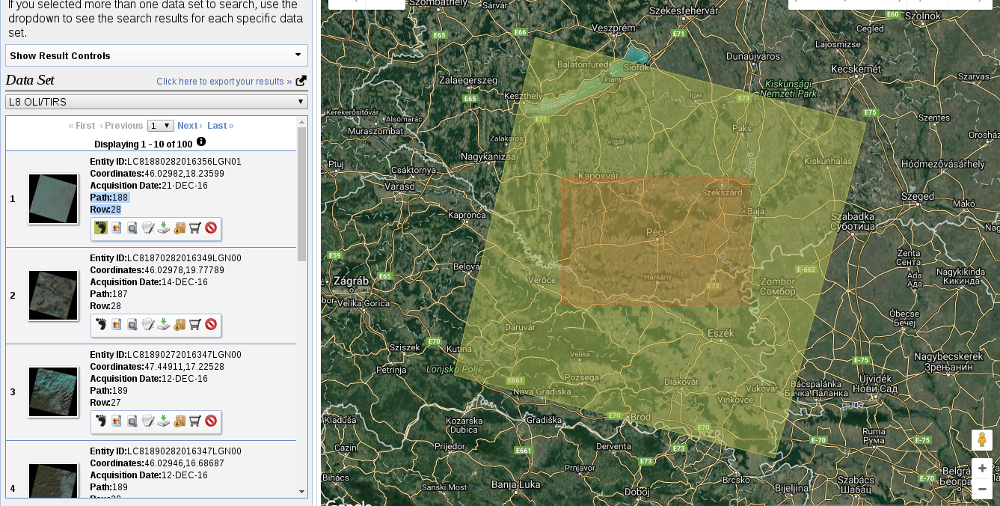

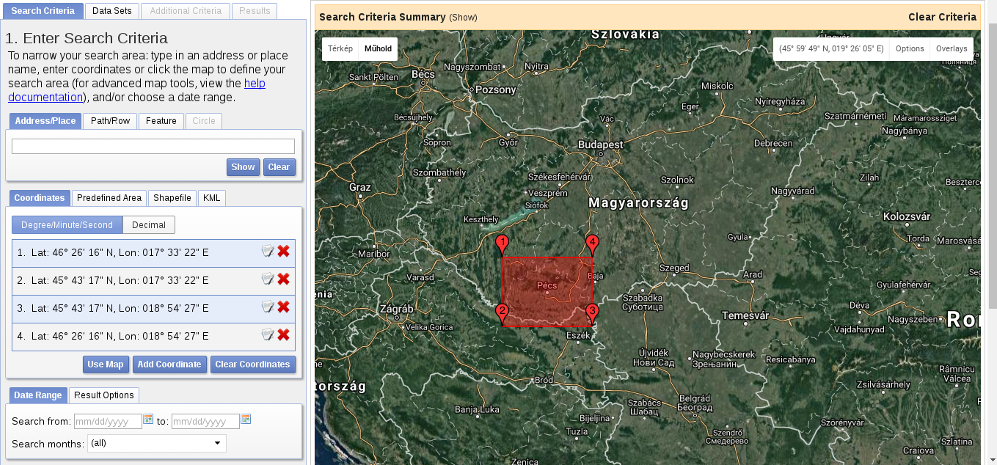

When we have an account, we should proceed to the Earth Explorer application and select our study area. We can select an area on the map by holding down the Shift button and drawing a rectangle with the mouse, as shown in the following screenshot:

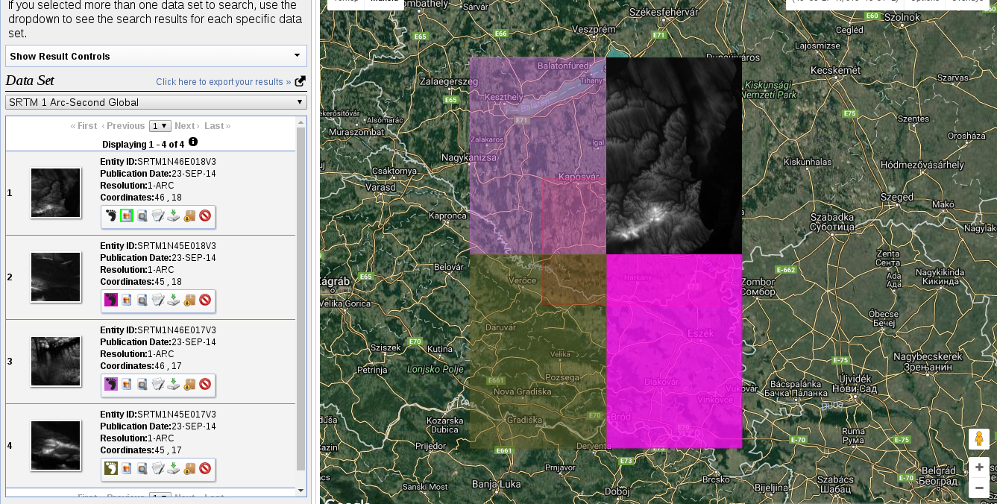

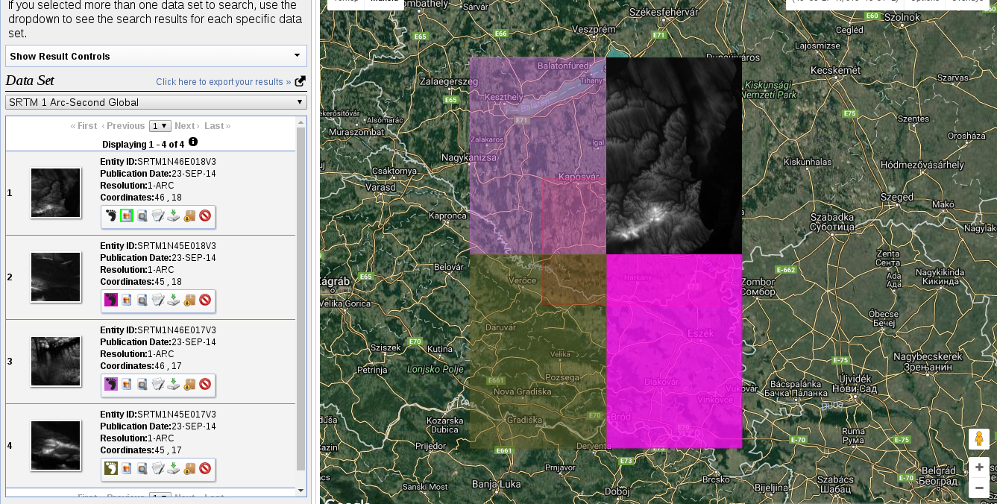

As the next step, we should select some data from the Data Sets tab. There are two distinct types of remote sensing based on the type of sensor: active and passive. In active remote sensing, we emit some kind of signal from the instrument and measure its reflectance from the target surface. We make our measurement from the attributes of the reflected signal. Three very typical active remote sensing instruments are radar (radio detection and ranging) using radio waves, lidar (light detection and ranging) using laser, and sonar (sound navigation and ranging) using sound waves. The first dataset we download is SRTM (Shuttle Radar Topographic Mission), which is a DEM (digital elevation model) produced with a radar mounted on a space shuttle. For this, we select the Digital Elevation item and then SRTM. Under the SRTM menu, there are some different datasets from which we need the 1 Arc-Second Global. Finally, we push the Results button, which navigates us to the results of our query. In the results window, there are quite a few options for every item, as shown in the following screenshot:

The first two options (Show Footprint and Show Browse Overlay) are very handy tools to show the selected imagery on the map. The footprint only shows the enveloping rectangle of the data, therefore, it is fast. Additionally, it colors every footprint differently, so we can identify them easily. The overlay tool is handy for getting a glance at the data without downloading it.

Finally, we download the tiles covering our study area. We can download them individually with the item's fifth option called Download Options. This offers some options from which we should select the BIL format as it has the best compression rate, thus, our download will be fast.

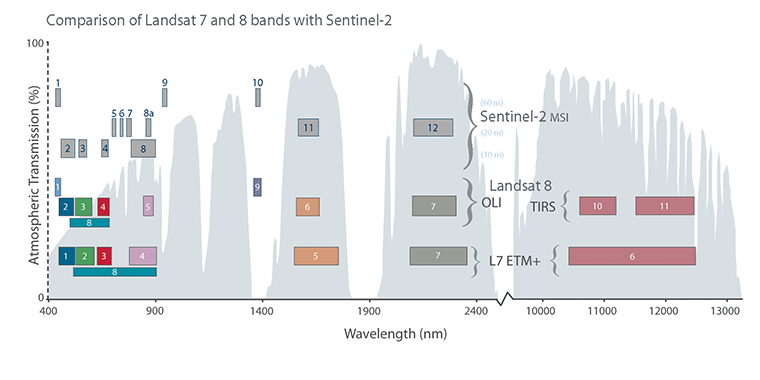

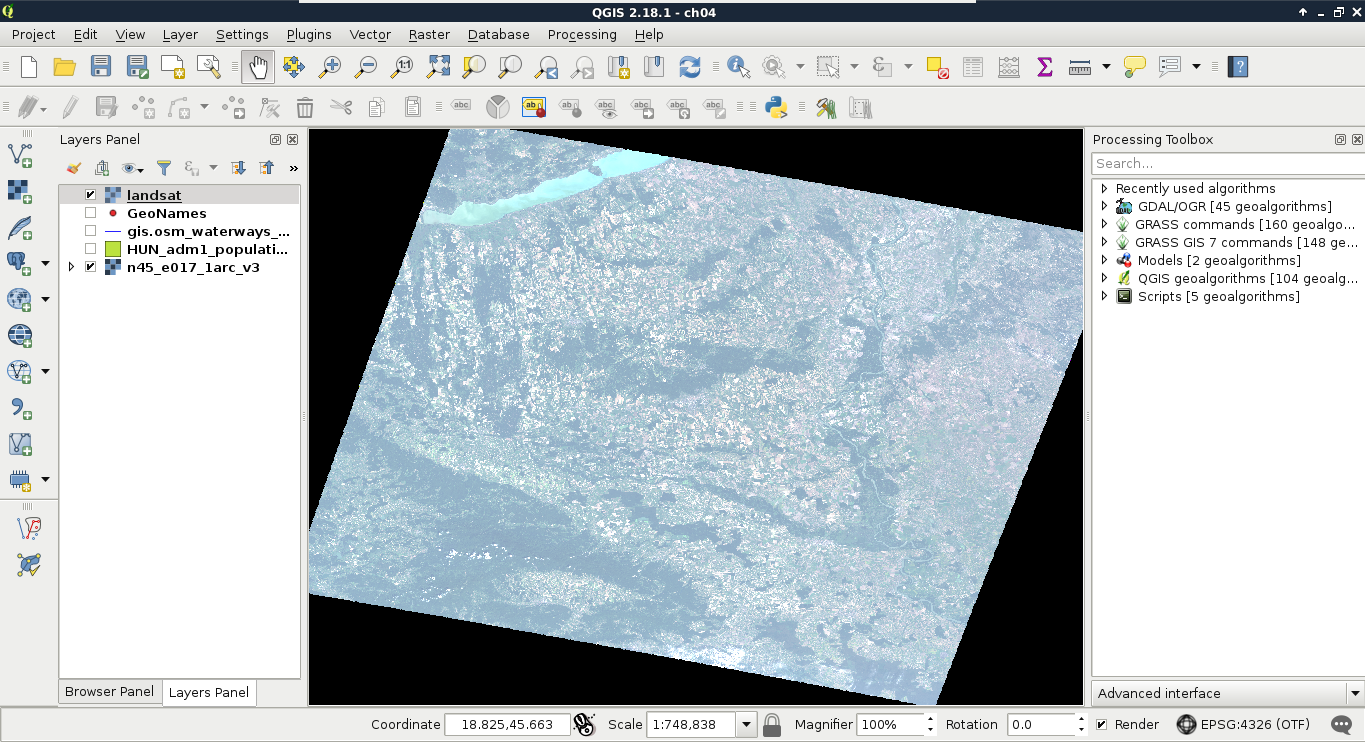

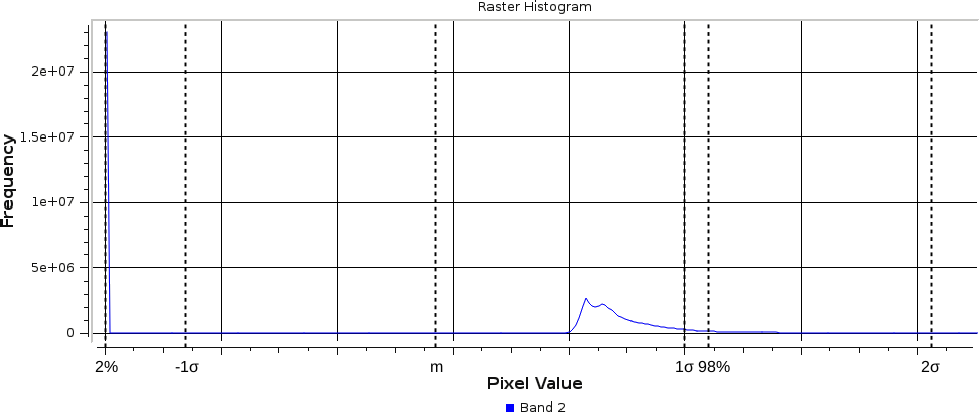

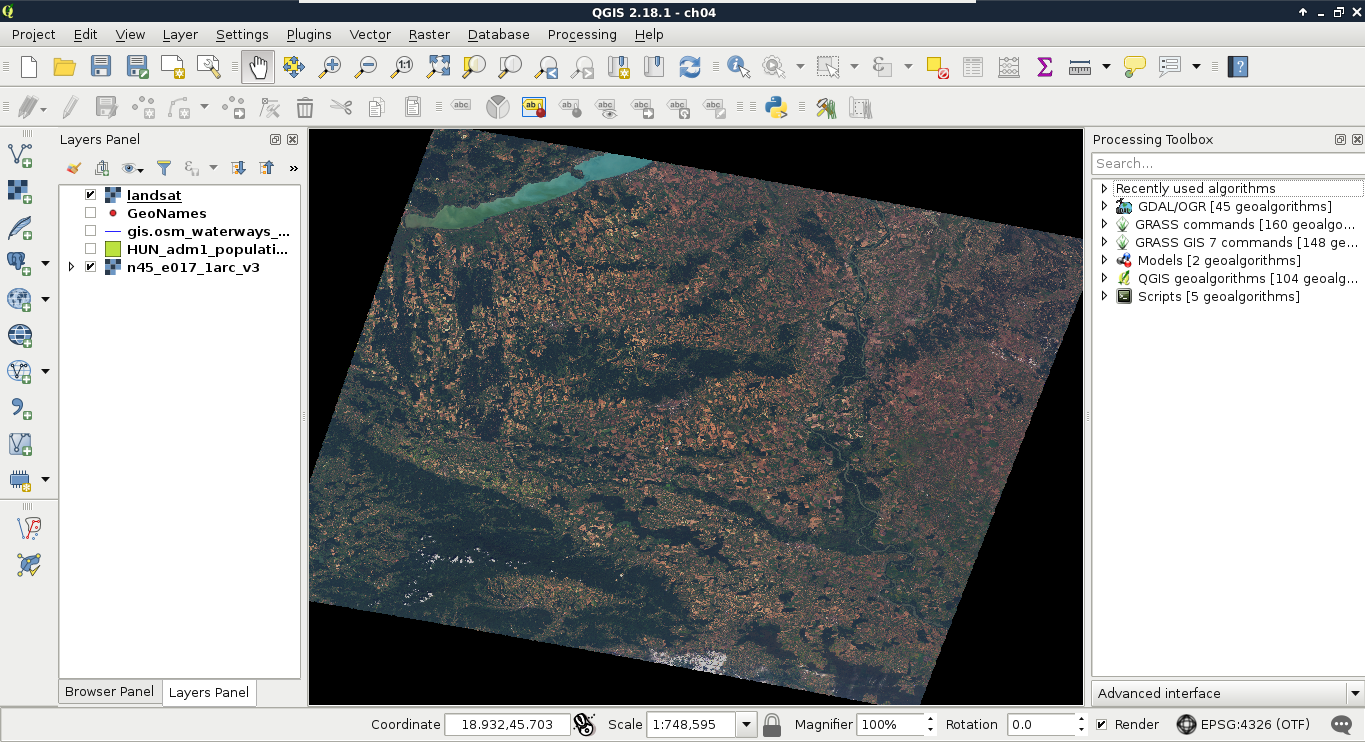

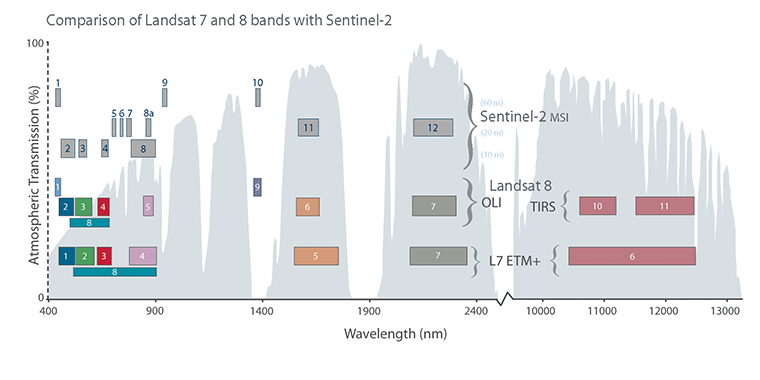

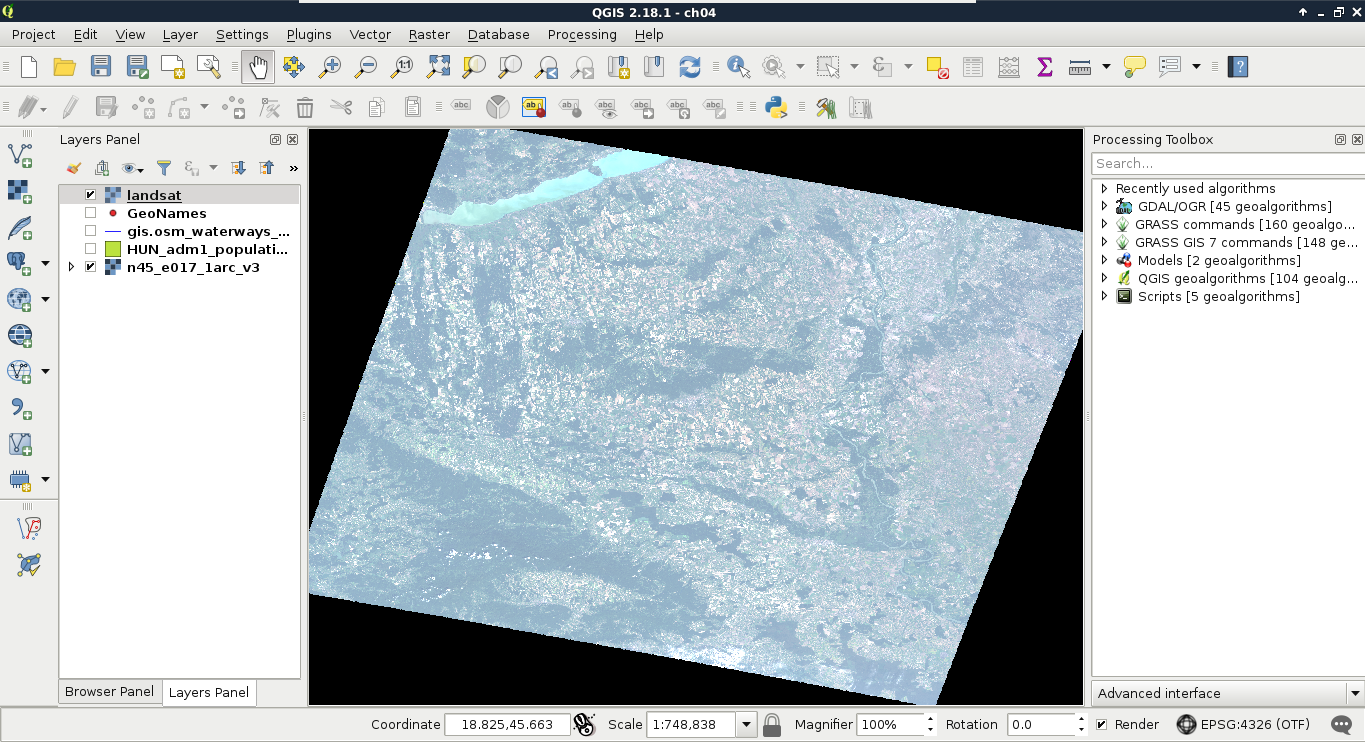

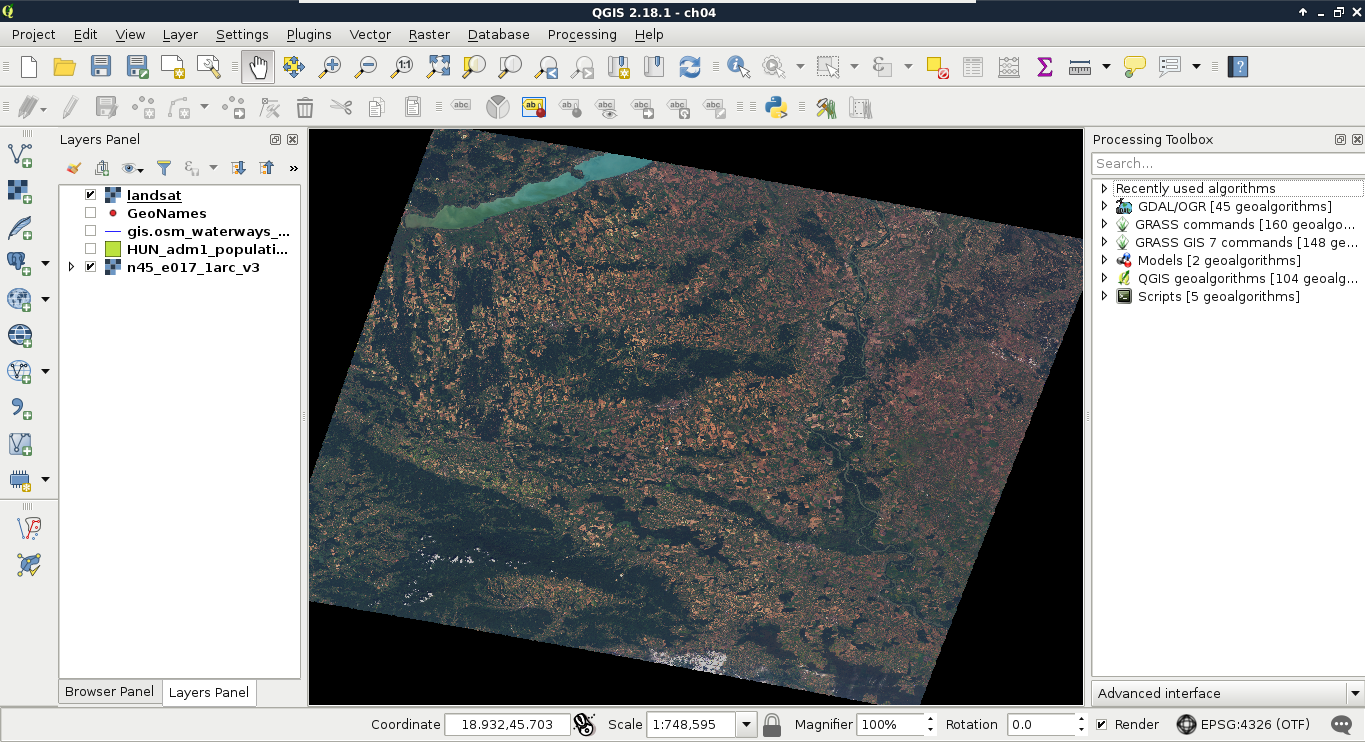

Let's get back to the Data Sets tab and select the next type of data we need to download--the Landsat data. These are measured with instruments of the other type--passive remote sensing. In passive remote sensing, we don't emit any signal, just record the electromagnetic radiance of our environment. This method is similar to the one used by our digital cameras except those record only the visible spectrum (about 380-450 nanometers) and compose an RGB picture from the three visible bands instantly. The Landsat satellites use radiometers to acquire multispectral images (bands). That is, they record images from spectral intervals, which can penetrate the atmosphere, and store each of them in different files. There is a great chart created by NASA (http://landsat.gsfc.nasa.gov/sentinel-2a-launches-our-compliments-our-complements/) which illustrates the bands of Landsat 7, Landsat 8, and Sentinel-2 along with the atmospheric opacity of the electromagnetic spectrum:

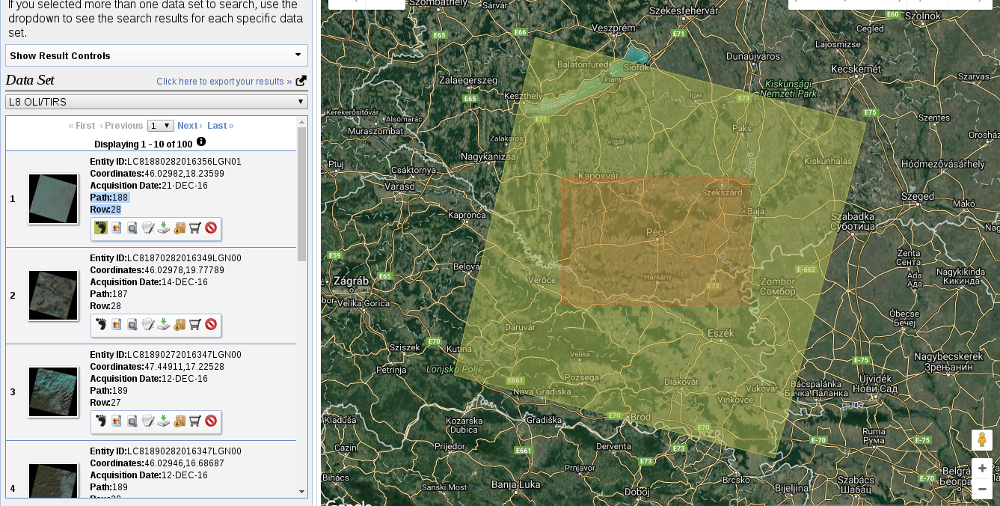

From the Landsat Archive, we need the Pre-Collection menu. From there, we select L8 OLI/TIRS and proceed to the results. With the footprints of the items, let's select an image which covers our study area. As Landsat images have a significant amount of overlap, there should be one image which, at least, mostly encases our study area. There are two additional information listed in every item--the row number and the path number. As these kinds of satellites are constantly orbiting Earth, we should be able to use their data for detecting changes. To assess this kind of use case (their main use case), their orbits are calculated so that, the satellites return to the same spot periodically (in case of Landsat, 18 days). This is why we can classify every image by their path and row information:

Let's note down the path and row information of the selected imagery and go to the Additional Criteria tab. We feed the path and row information to the WRS Path and WRS Row fields and go back to the results. Now the results are filtered down, which is quite convenient as the images are strongly affected by weather and seasonal effects. Let's choose a nice imagery with minimal cloud coverage and download its Level 1 GeoTIFF Data Product. From the archive, we will need the TIFF files of bands 1-6.

SRTM is in the public domain; therefore, it can be used without restrictions, and giving attribution is also optional. Landsat data is also open source; however, based on USGS's statement (https://landsat.usgs.gov/are-there-any-restrictions-use-or-redistribution-landsat-data), proper attribution is recommended.

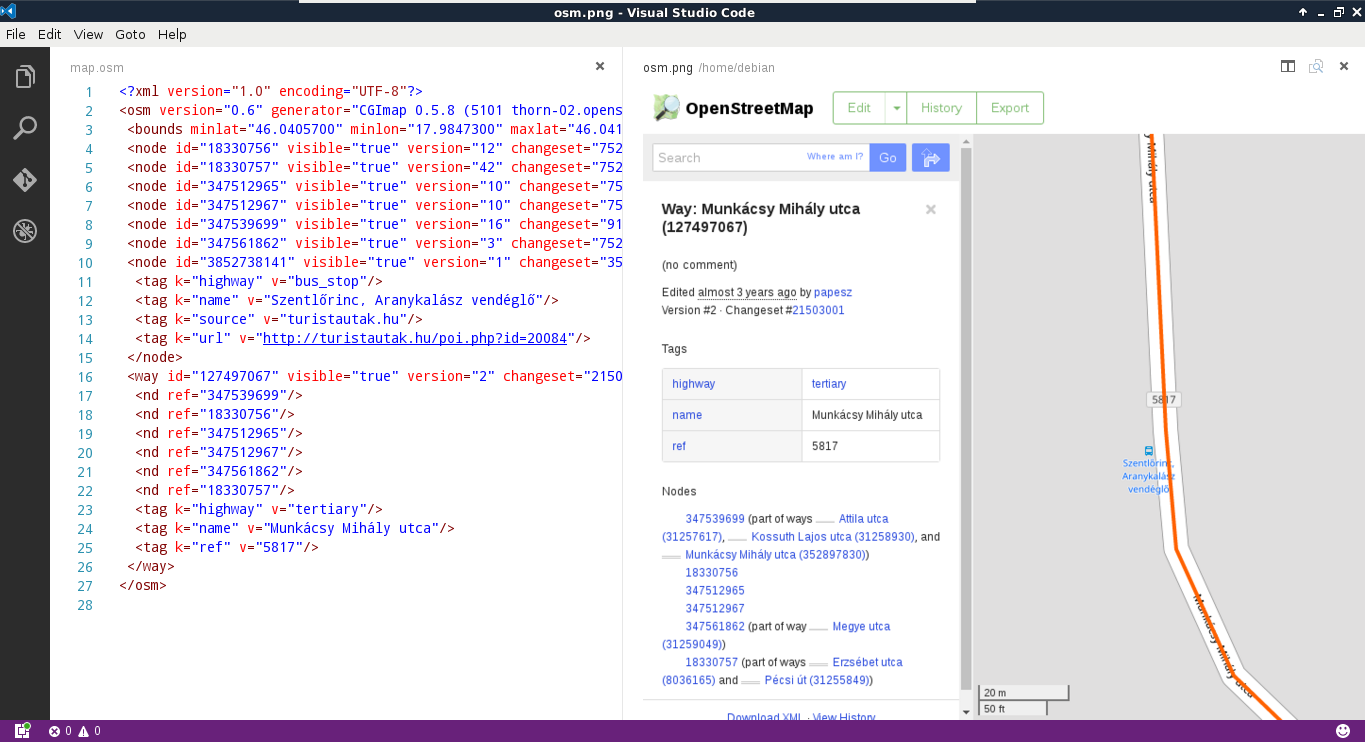

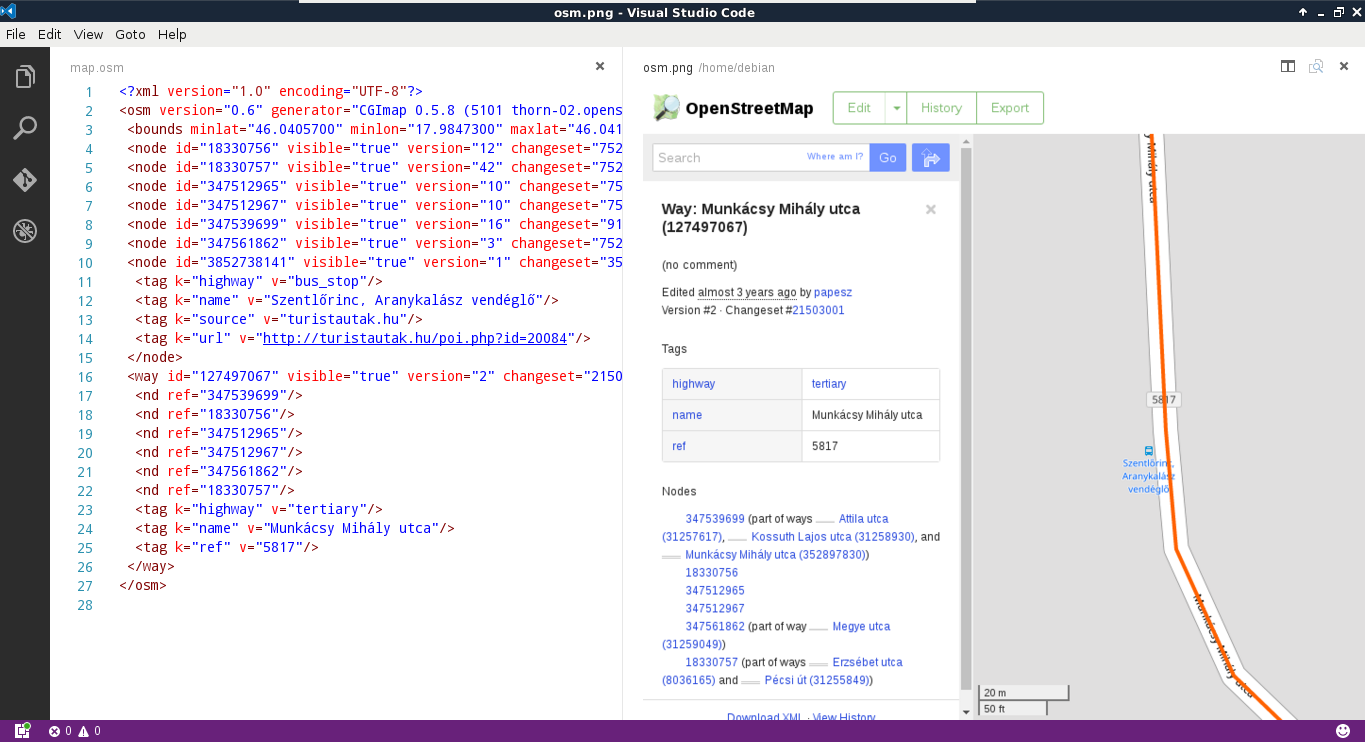

The last dataset we put our hands on is the swiss army knife of open source GIS data. OpenStreetMap provides vector data with a great global coverage coming from measurements of individual contributors. OpenStreetMap has a topological structure; therefore, it's great for creating beautiful visualizations and routing services. On the other hand, its collaborative nature makes accuracy assessments hard. There are some studies regarding the accuracy of the whole data, or some of its subsets, but we cannot generalize those results as accuracy can greatly vary even in small areas.

One of the main strengths of OpenStreetMap data is its large collection and variety of data themes. There are administrative borders, natural reserves, military areas, buildings, roads, bus stops, even benches in the database. Although its data isn't surveyed with geodesic precision, its accuracy is good for a lot of cases: from everyday use to small-scale analysis where accuracy in the order of meters is good enough (usually, a handheld GPS has an accuracy of under 5 meters). Its collaborative nature can also be evaluated as a strength as mistakes are corrected rapidly and the content follows real-world changes (especially large ones) with a quick pace.

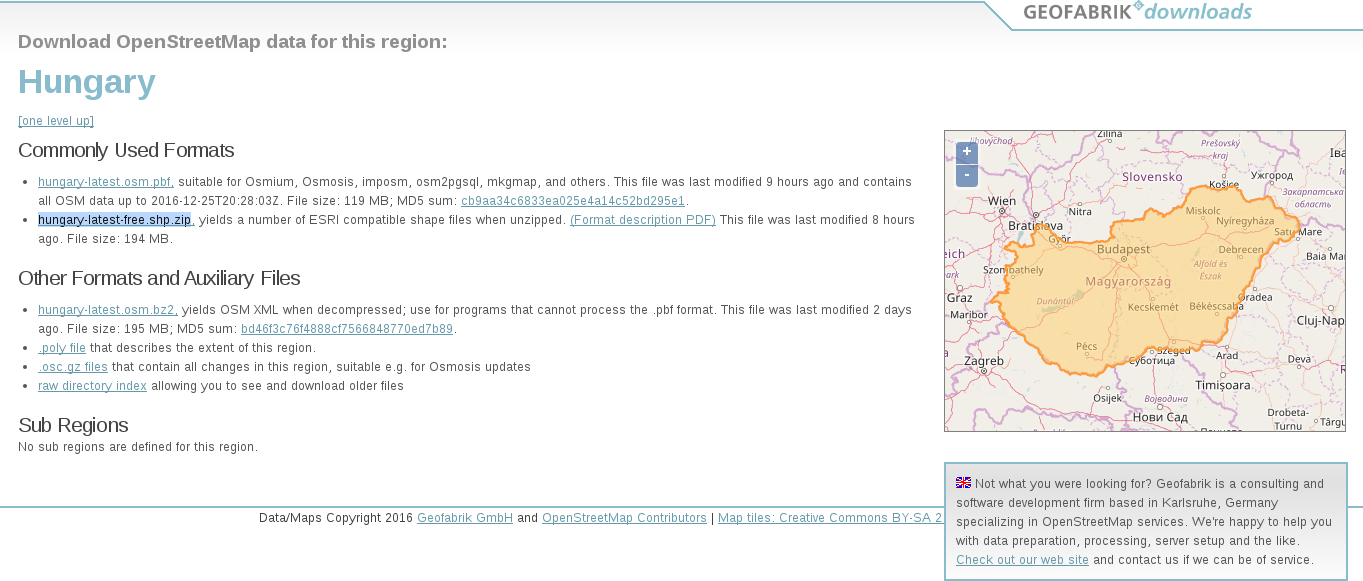

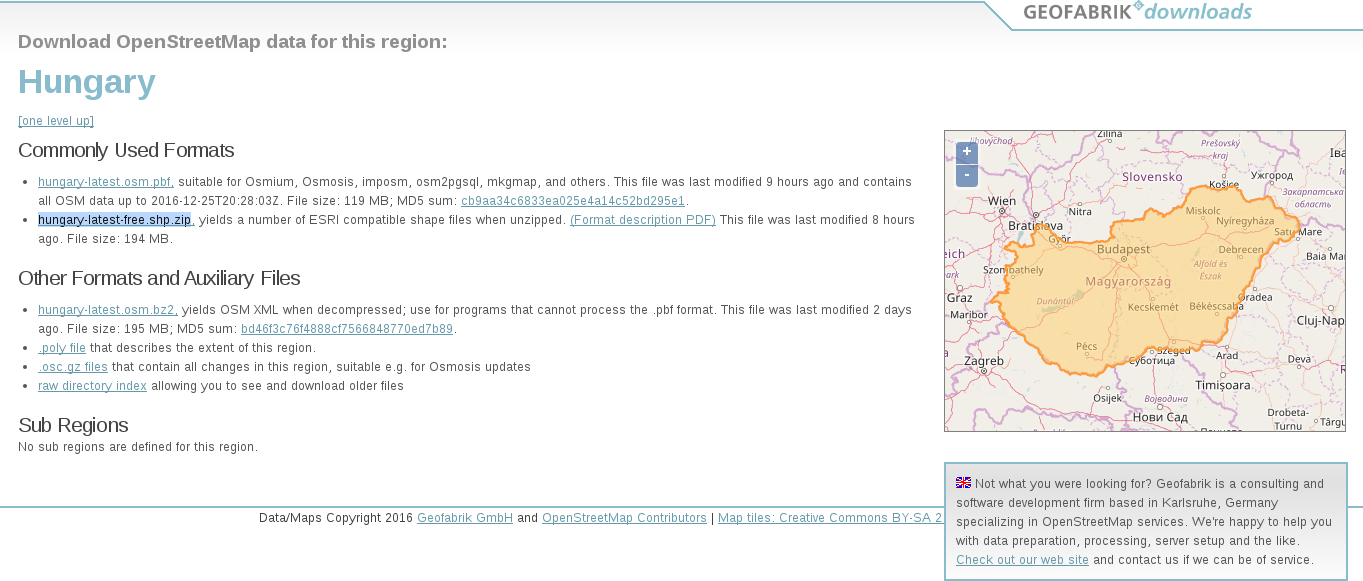

Accessing OpenStreetMap data can be tricky. There are some APIs and other means to query OSM, although either we need to know how to code or we get everything in one big file. There is one peculiar company which creates thematic data extracts from the actual content--Geofabrik. We can reach Geofabrik's download portal at http://download.geofabrik.de/. It allows us to download data in OSM's native PBF format (Protocolbuffer Binary Format), which is great for filling a PostGIS database with OSM data from the command line on a Linux system but cannot be opened with a desktop GIS client. It also serves XML data, which is more widely supported, but the most useful extracts for us are the shapefiles.

Due to various reasons, open source shapefiles are only exported by Geofabrik for small areas. We have to narrow down our search by clicking on links until the shapefile format (.shp.zip) is available. This means country-level extracts for smaller countries and regional extracts for larger or denser ones. The term dense refers to the amount of data stored in the OSM database for a given country. Let's download the shapefile for the smallest region enveloping our study area:

OpenStreetMap data is licensed under ODbL, an open source license, and therefore gives the four basic freedoms. However, it has two important conditions. The first one is obligatory attribution, while the second one is a share-alike condition. If we use OpenStreetMap data in our work, we must share the OSM part under an ODbL-compatible open source license.

ODbL differentiates three kind of products: collective database, derived database, and produced work. If we create a collective database (a database which has an OSM part), the share-alike policy only applies on the OSM part. If we create a derived database (make modifications to the OSM database), we must make the whole thing open source. If we create a map, a game, or any other work based on the OSM database, we can use any license we would like to. However, if we modify the OSM database during the process, we must make the modifications open source.

In this chapter, we installed the required open source GIS software, configured some of them, and downloaded a lot of open source data. We became familiar with open source products, licenses, and data sources. Now we can create an open source GIS working environment from zero and acquire some data to work with. We also gained some knowledge about data collection methods and their nature.

In the next chapter, we will visualize the downloaded data in QGIS. We will learn to use some of the most essential functionalities of a desktop GIS client while browsing our data. We will also learn some of the most basic attributes and specialities of different data types in GIS.

Despite the fact that some of the advanced GIS software suggest, we only need to know which buttons to press in order to get instant results, GIS is much more than that. We need to understand the basic concepts and the inner workings of a GIS in order to know the kind of analyses we can perform on our data. We must be able to come up with specific workflows, models which get us the most meaningful results. We also need to understand the reference frame of GIS, how our data behaves in such an environment, and how to interpret those results. In this chapter, we will learn about GIS data models by browsing our data in QGIS, and getting acquainted with its GUI.

In this chapter, we will cover the following topics:

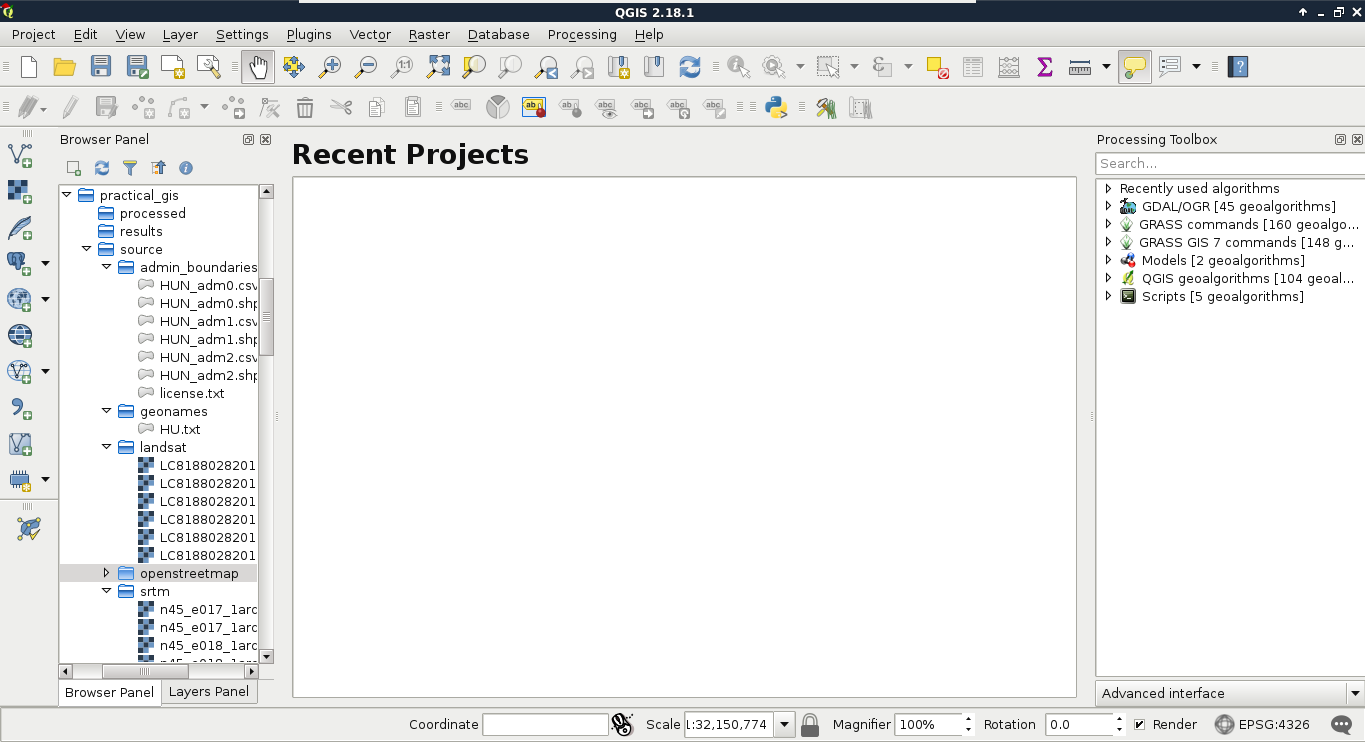

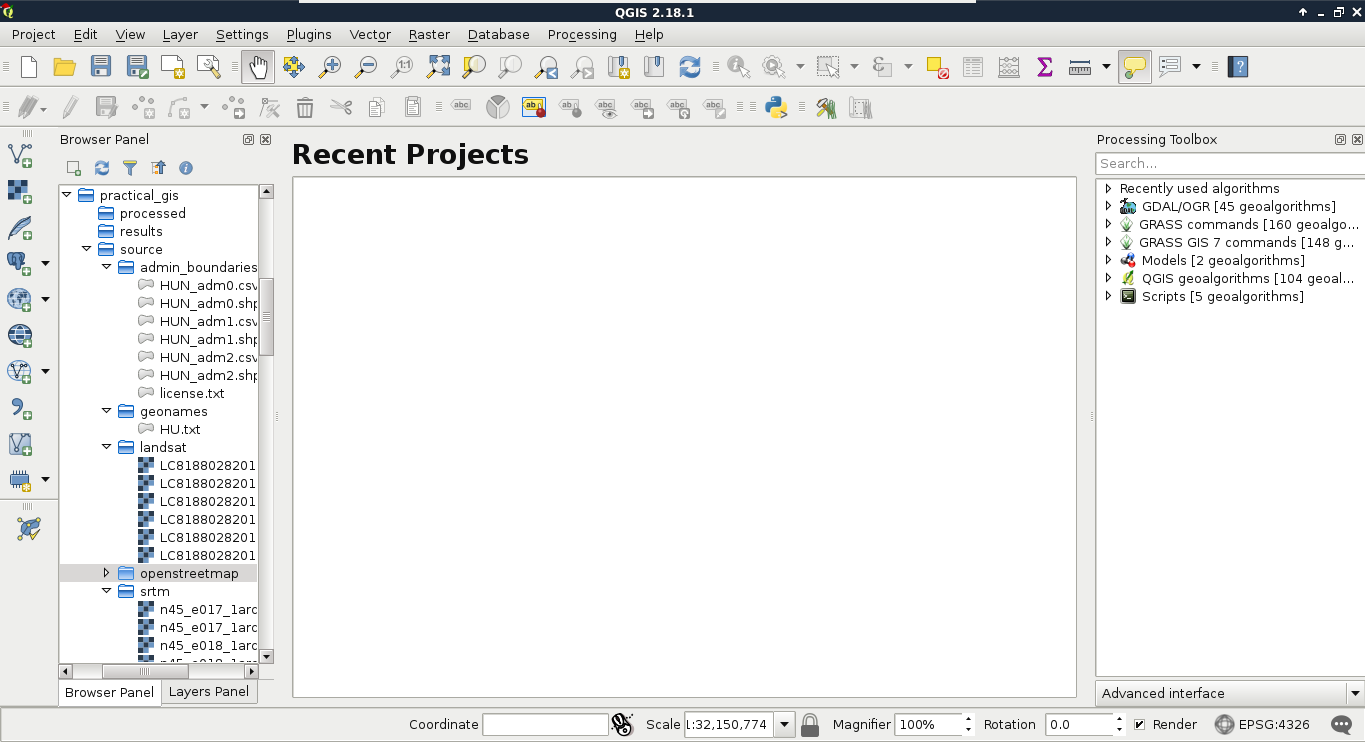

The first data type that we will use is raster data. It might be the most familiar to you, as it resembles traditional images. First of all, let's open QGIS. In the browser panel, we can immediately see our downloaded data if we navigate to our working directory. We can easily distinguish vector data from raster data by their icons. Raster layers have a dedicated icon of a 3x3 pixels image, while vector layers have an icon of a concave polygon:

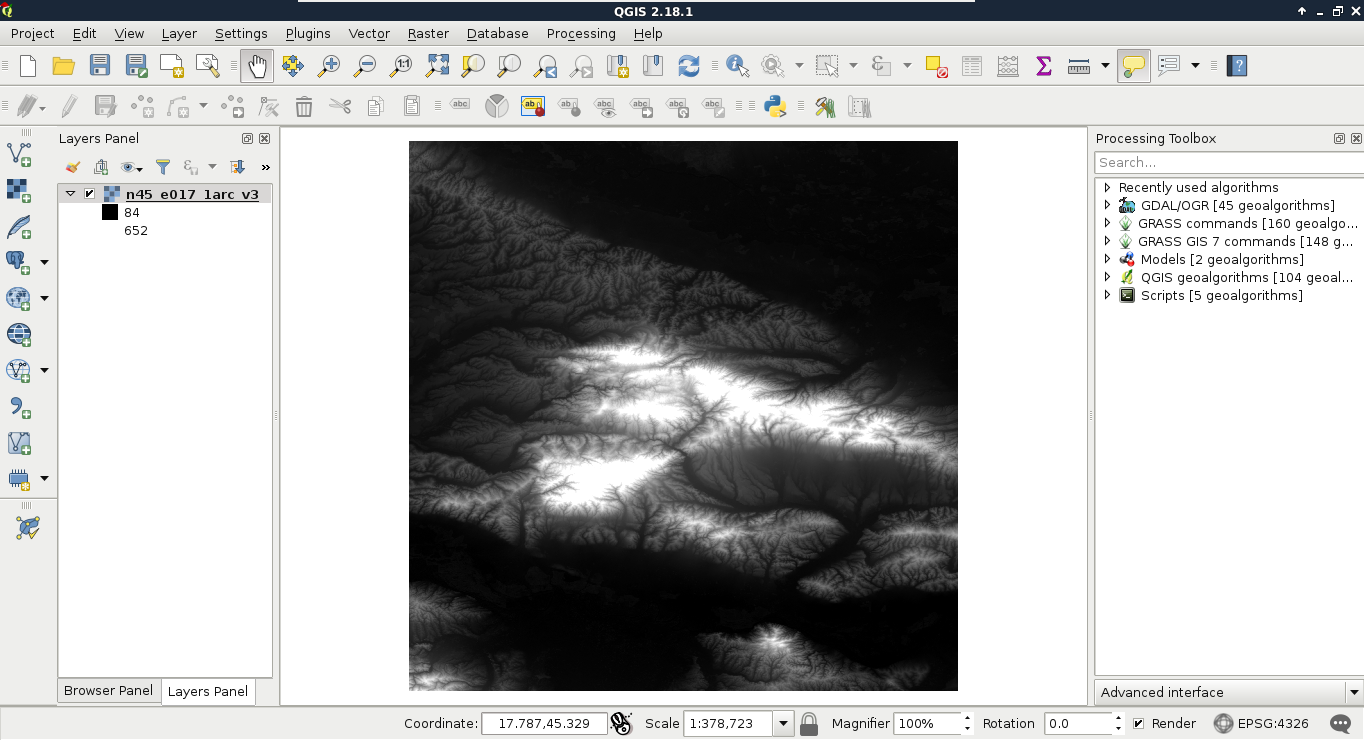

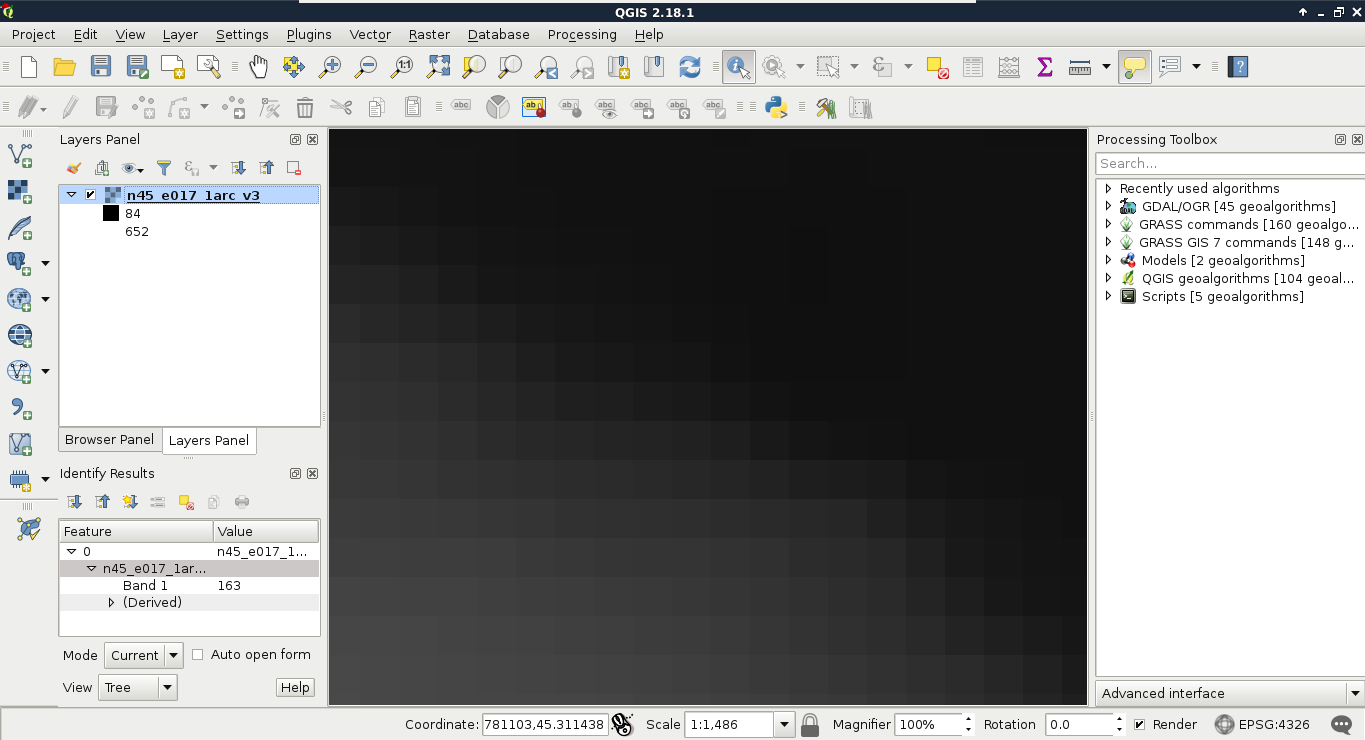

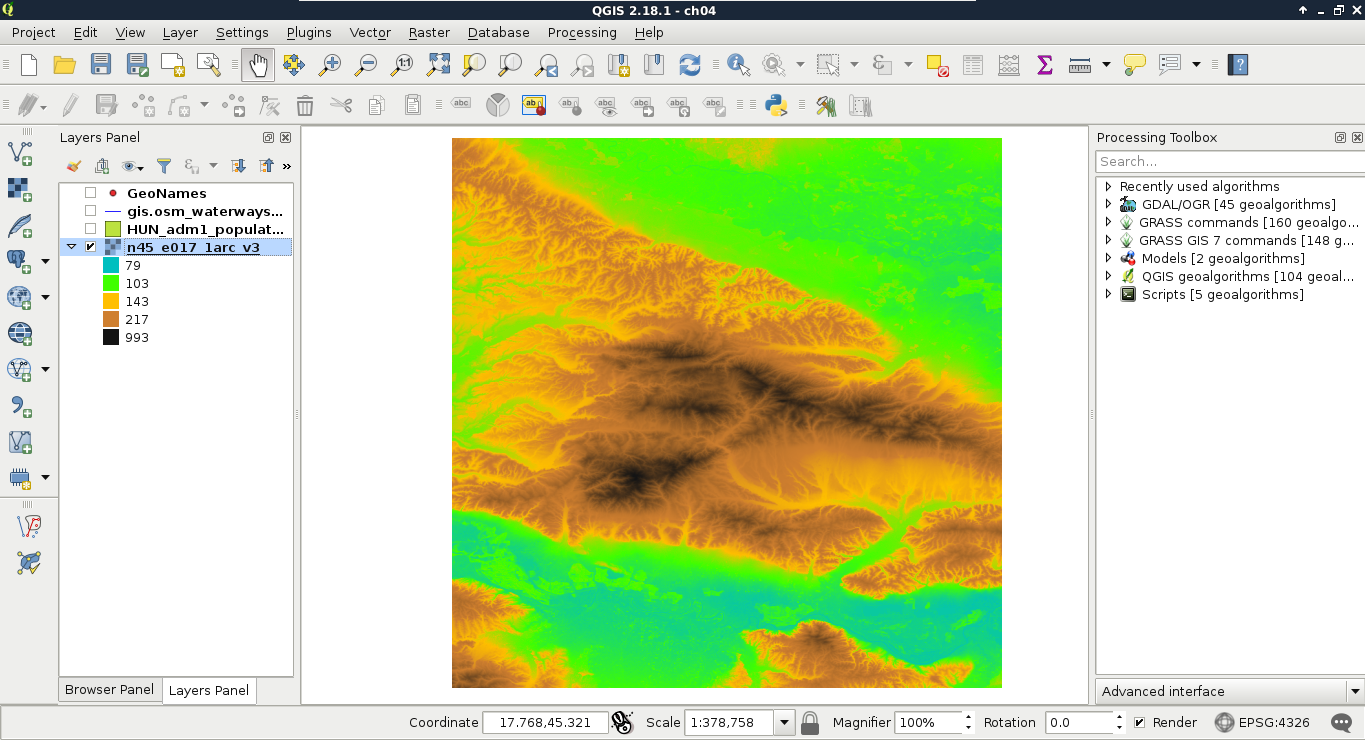

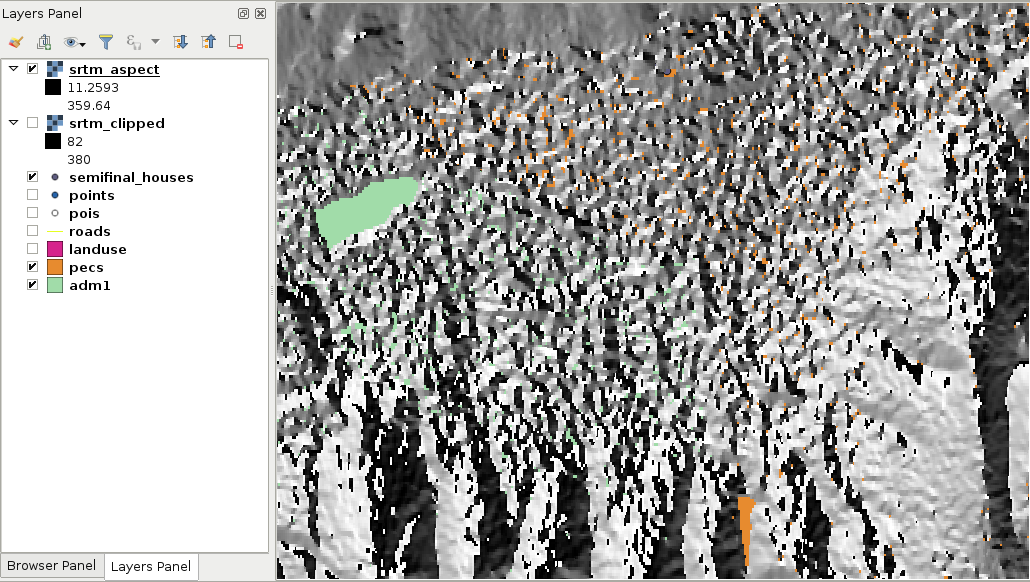

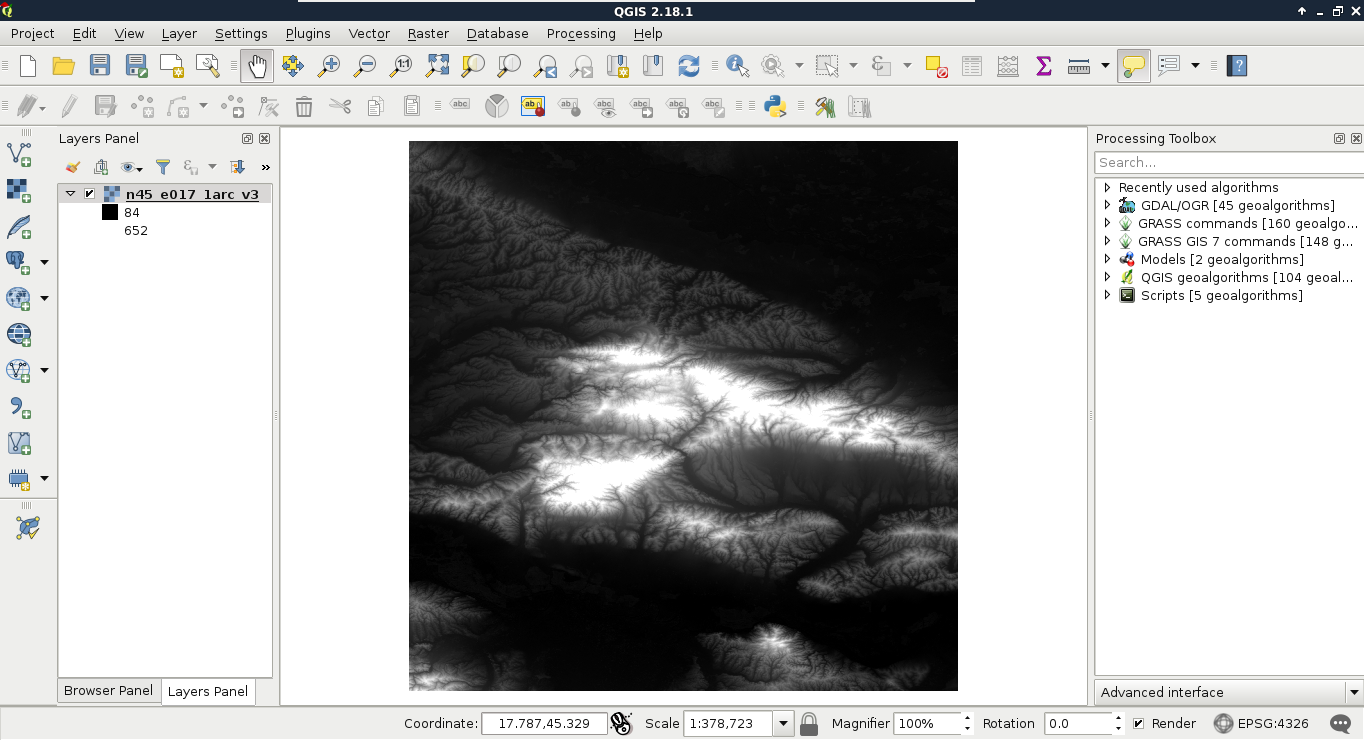

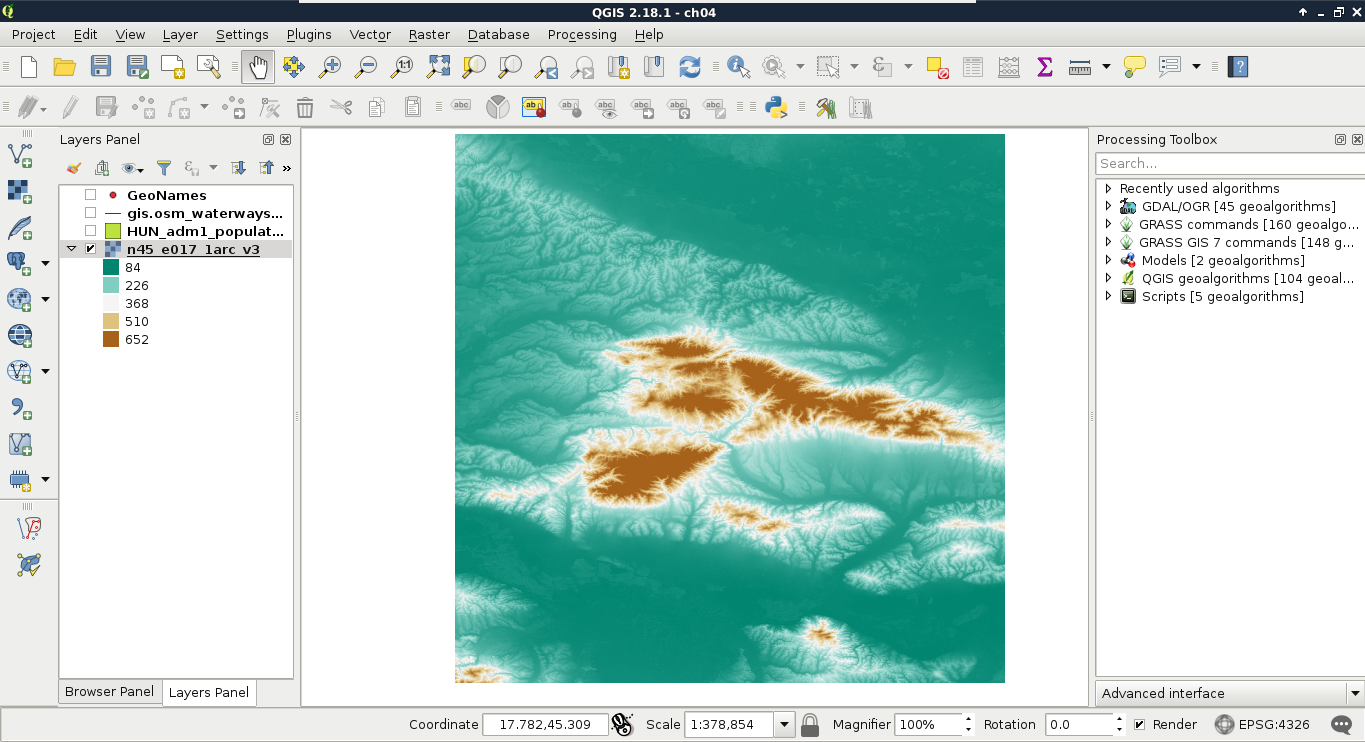

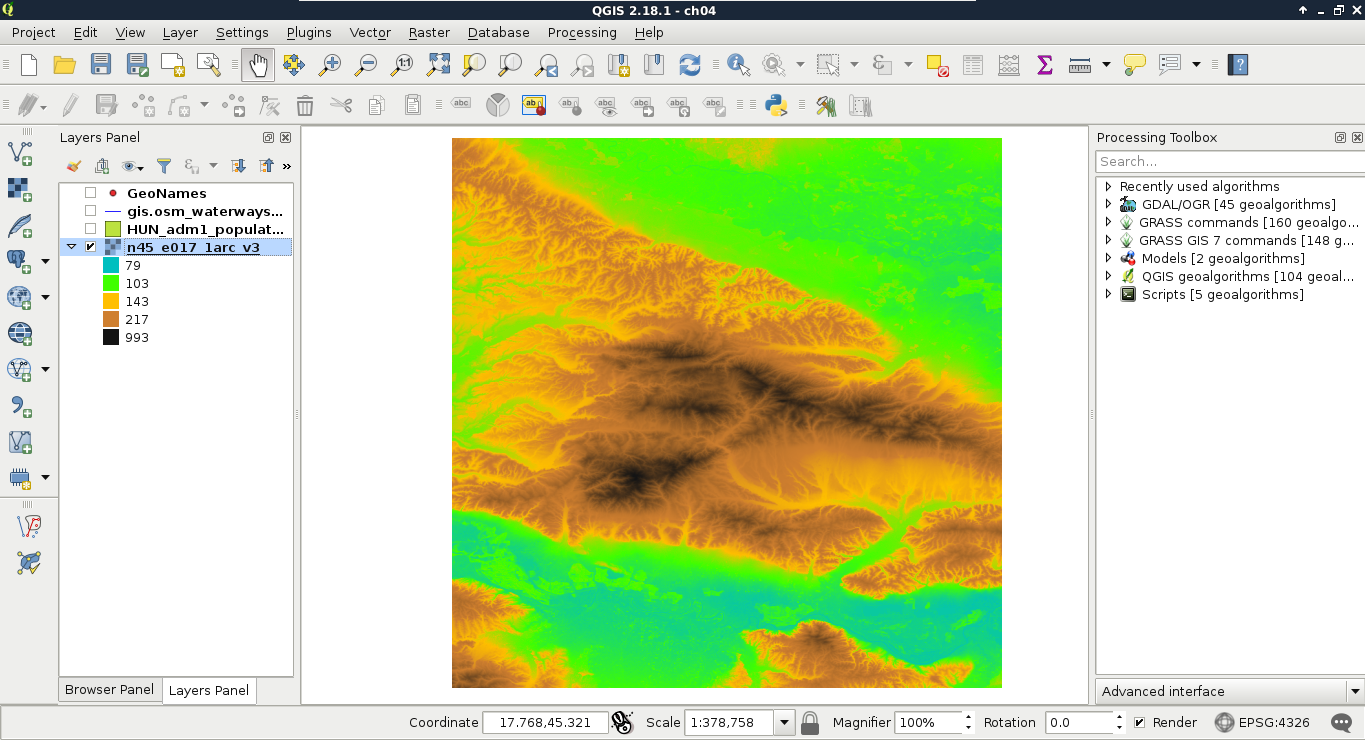

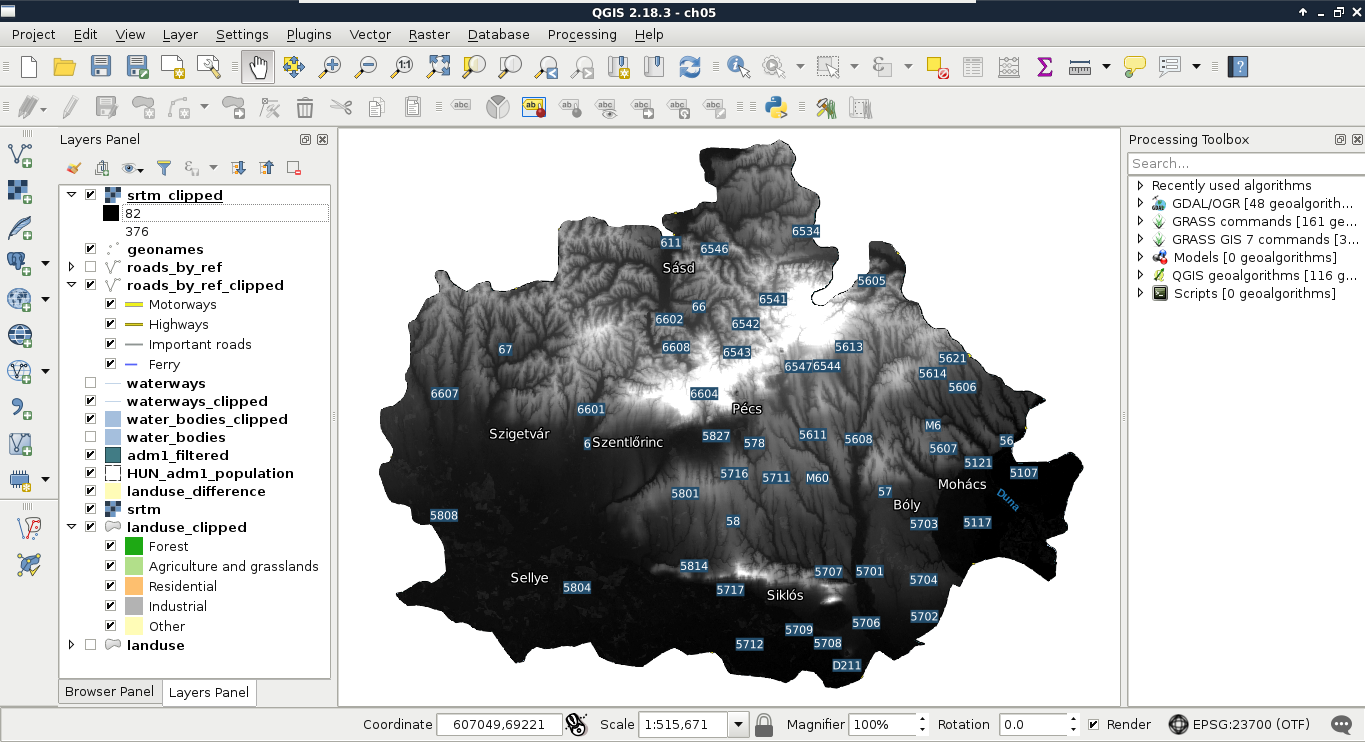

We can drag and drop most of the data from the browser panel or, alternatively, use the Add Raster Layer button from the Add layer toolbar and browse the layer. The browser panel is more convenient for easily recognizable layers as it only lists the files we can open and hides auxiliary files with every kind of metadata. Let's drag one of the SRTM rasters to the canvas (or open one with Add Raster Layer). This is a traditional, single-band raster. It is displayed as a greyscale image with the minimum and maximum values displayed in the Layers Panel:

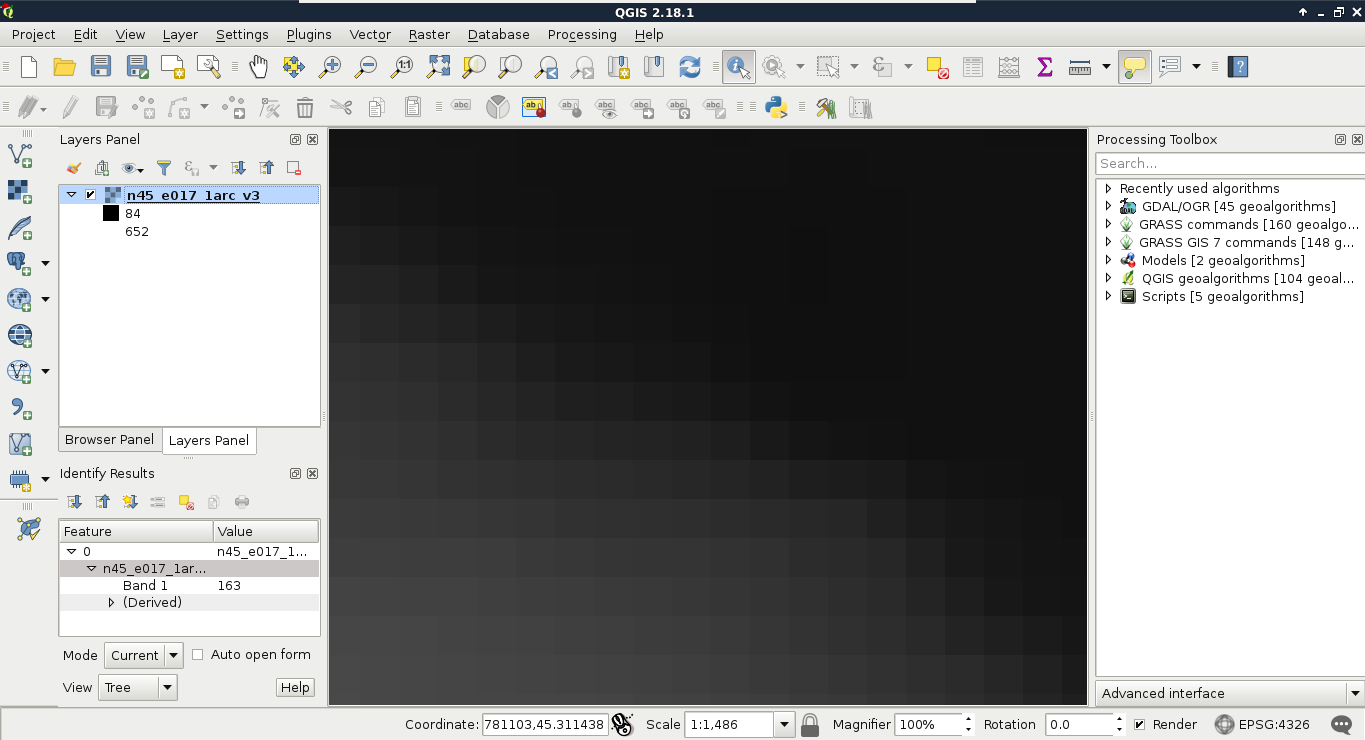

As you can see in the preceding screenshot, there is a regular grid with cells painted differently, just like an image. However, based on the maximum value of the data, its colors aren't hard coded into the file, like in an image. Furthermore, it has only a single band, not three or four bands for RGB(A). Let's examine the raster more carefully by zooming in until we can see individual cells. We can also query them for their values with the Identify Features tool by clicking on a cell (raster):

As you can see, we get a number for every cell, which can be quite out of the range of 0-255 representing color codes. These numbers seem arbitrary, and indeed, they are arbitrary. They usually represent some kind of real-world phenomenon, like in our case, the elevation from the mean sea level in meters.

These are the basic properties of the raster data model. Raster data are regular grids (matrices) made up from individual cells with some arbitrary values describing something. The values are only limited by the type of the storage. They can be in the range of bytes, 8-bit integers, 16-bit integers, floating point numbers, and so on. Rasters are always rectangular (like an image); however, they can give a feeling of having some other shape with a special kind of value: NULL or No-Data.

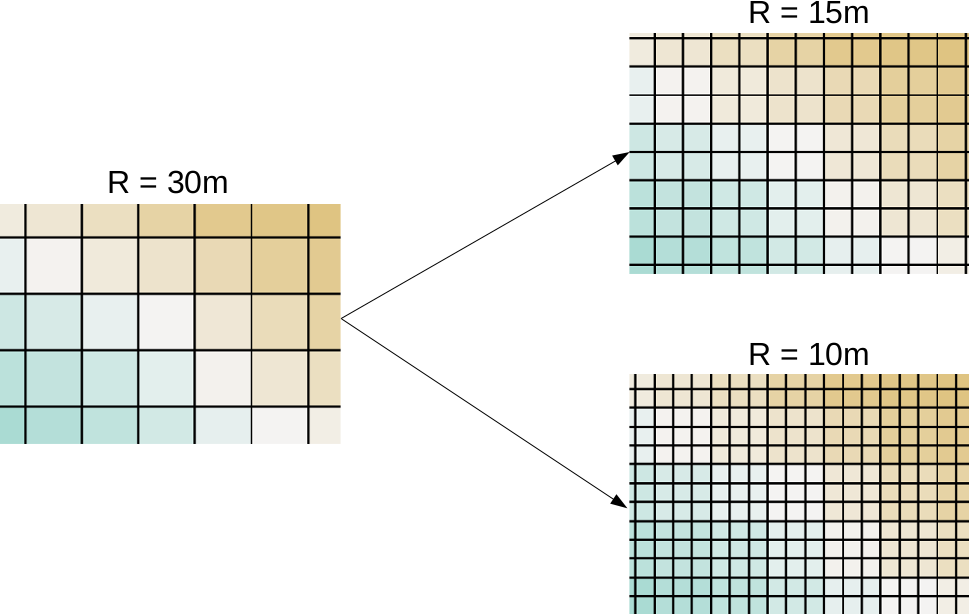

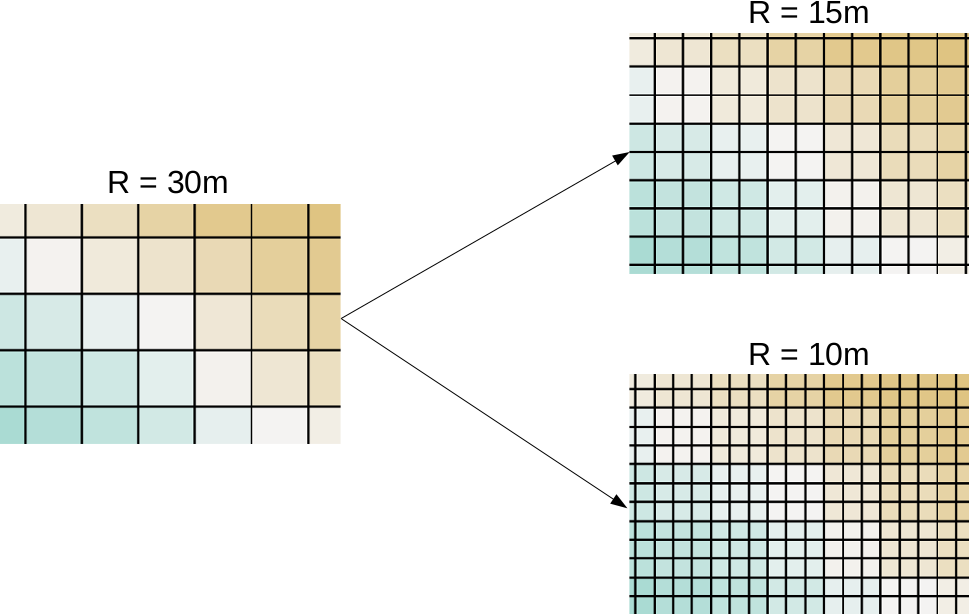

One of the most useful properties of raster data is that their coverage is continuous, while their data can change. They cover their entire extent with coincident cells. If we need a full and continuous coverage (that is, we need a value for every point describing a dynamically changing phenomenon), raster is an obvious choice. On the other hand, they have a fixed layout inherited from their resolution (the size of each cell). There are the following two implications from this property:

Of course, this property works in two ways. Rasters (especially with square cells) are generally easy and fast to visualize as they can be displayed as regular images. To make the visualization process even faster, QGIS builds pyramids from the opened rasters.

Using pyramids is a computer graphics technique adopted by GIS. Pyramids are downsampled (lower resolution) versions of the original raster layer stored in memory, and are built for various resolutions. By creating these pyramids in advance, QGIS can skip most of the resampling process on lower resolutions (zoom levels), which is the most time-consuming task in drawing rasters.

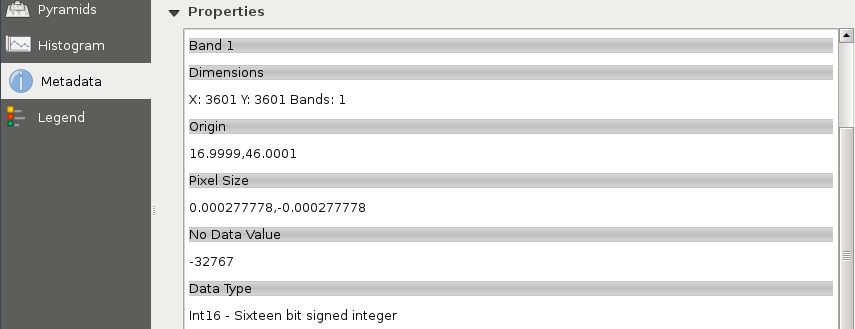

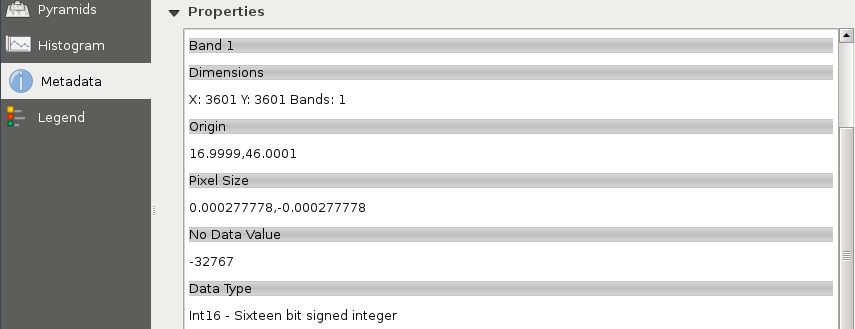

The last important property of a raster layer is its origin. As raster data behaves as two-dimensional matrices, it can be spatially referenced with only a pair of coordinates. These coordinates, unlike in graphics, are the lower left ones of the data. Let's see what QGIS can tell us about our raster layer. We can see its metadata by right-clicking on it in the Layers Panel, choosing Properties, and clicking on the Metadata tab:

As you can see in the preceding screenshot, our raster layer has a number of rows and columns, one band, an Origin, a resolution (Pixel Size), a No-Data value, and a Data Type.

To sum up, the raster data model offers continuous coverage for a given extent with dynamically changing, discrete values in the form of a matrix. We can easily do matrix operations on rasters, but we can also convert them to vectors if it is a better fit for the analysis. The raster data model is mainly used when the type of the data desires it (for example, mapping continuous data, like elevation or terrain, weather, or temperature) and when it is the appropriate model for the measuring instrument (for example, aerial or satellite imaging).

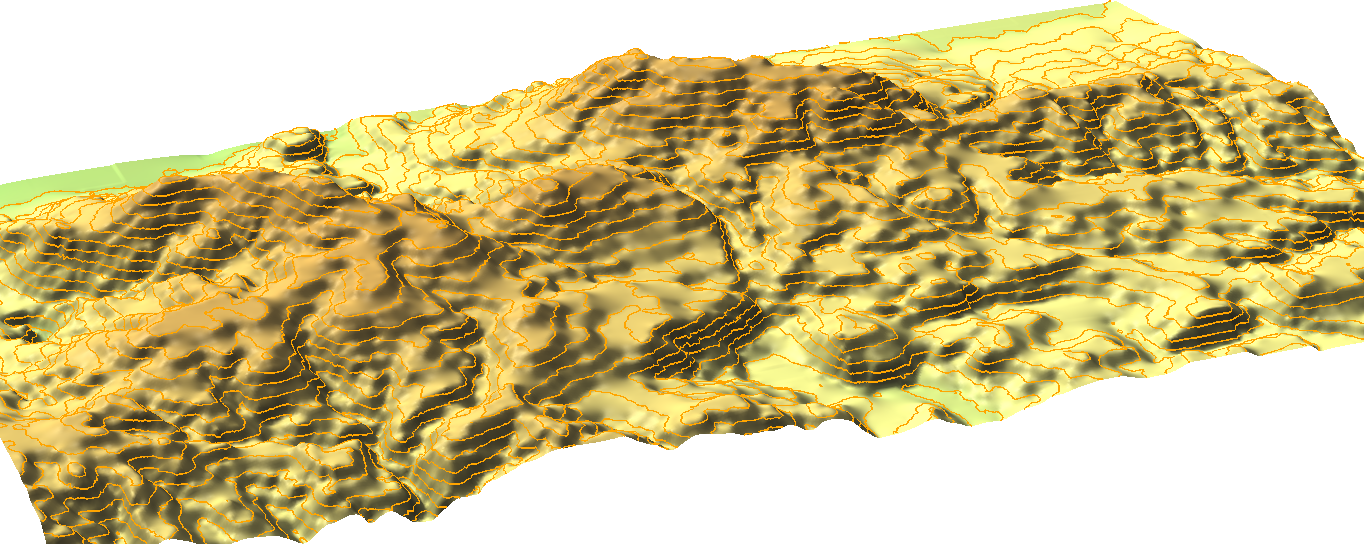

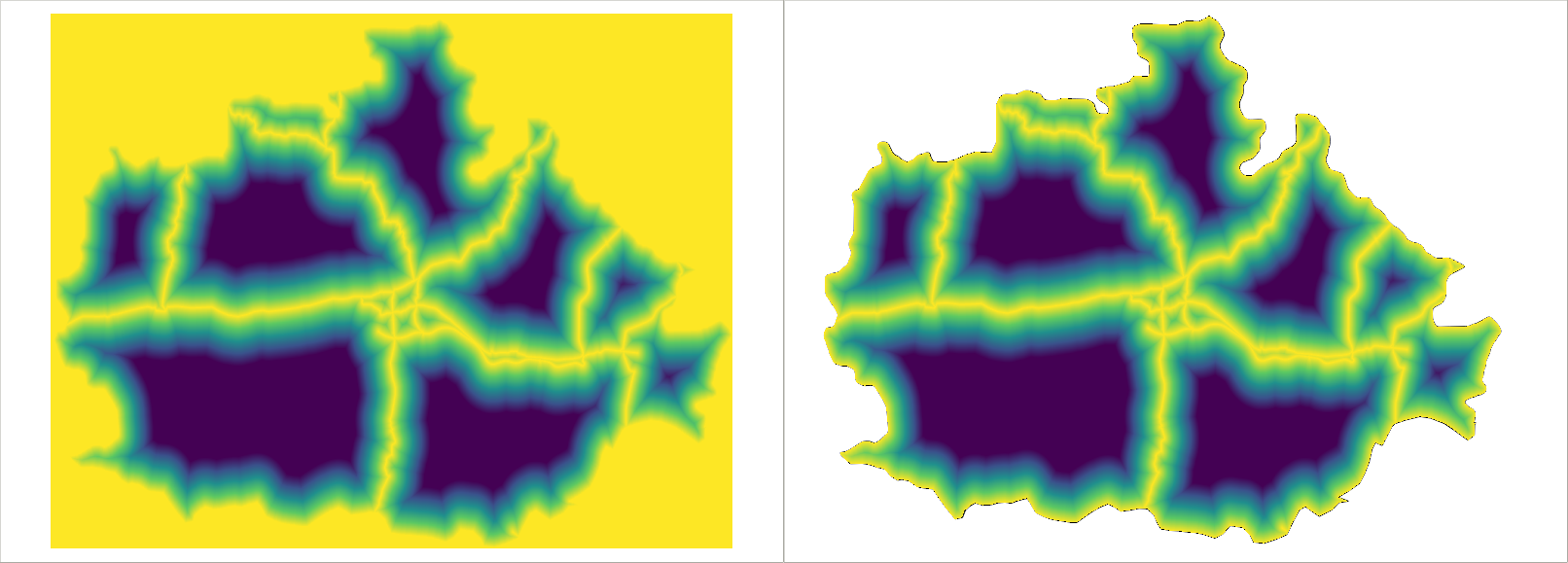

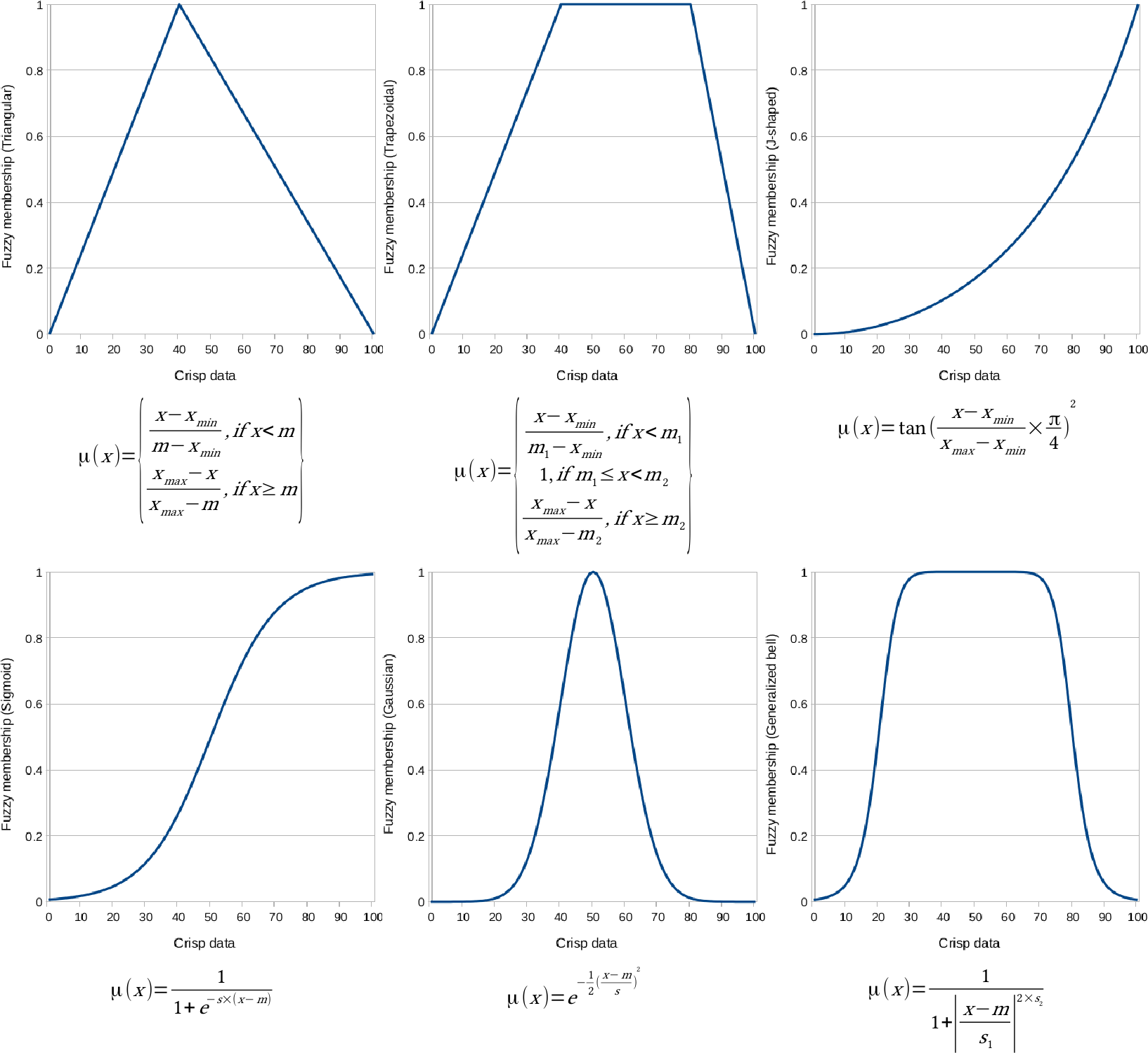

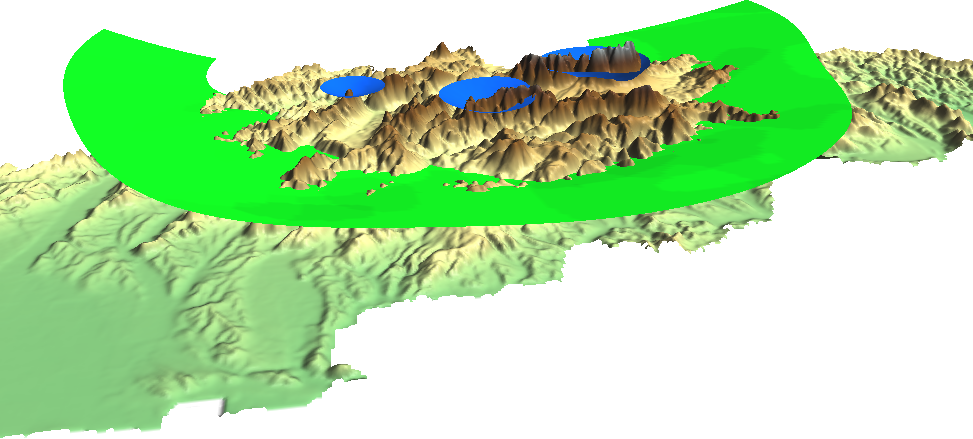

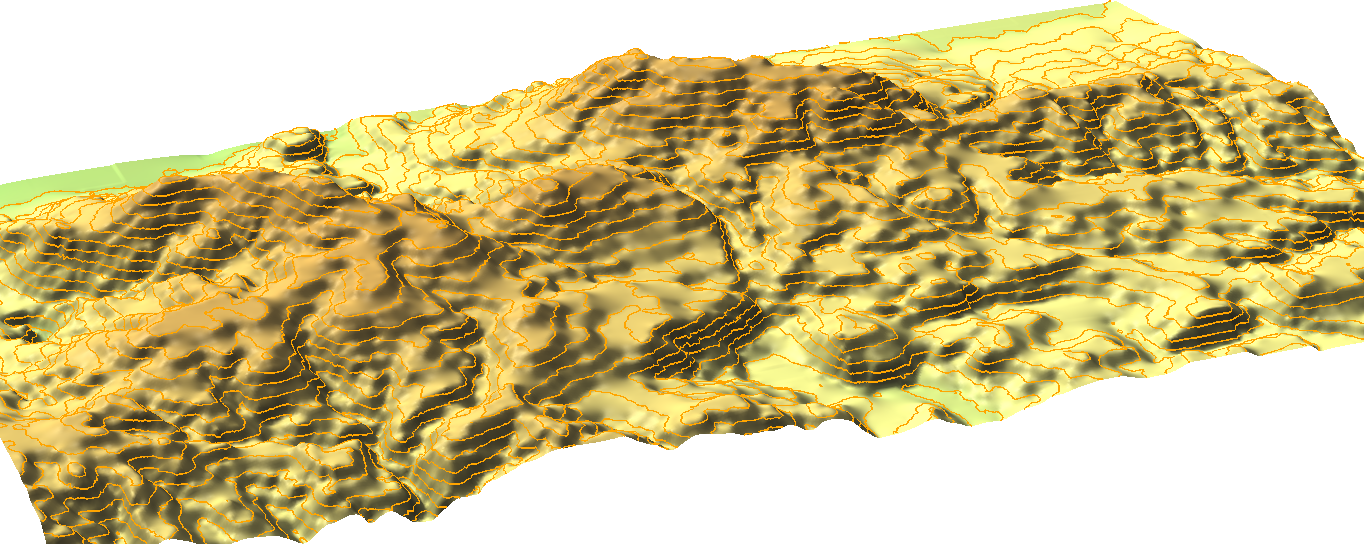

To put it simply--absolutely not. Well, maybe in QGIS a little bit, but rasters have potential far beyond the needs of an average GIS analysis. First of all, rasters do not need to be in two-dimensional space. There are 3D rasters called voxels, which can be analyzed in their volume or cut to slices, visualized in a whole, in slices, or as isosurfaces for various values (Appendix 1.1).

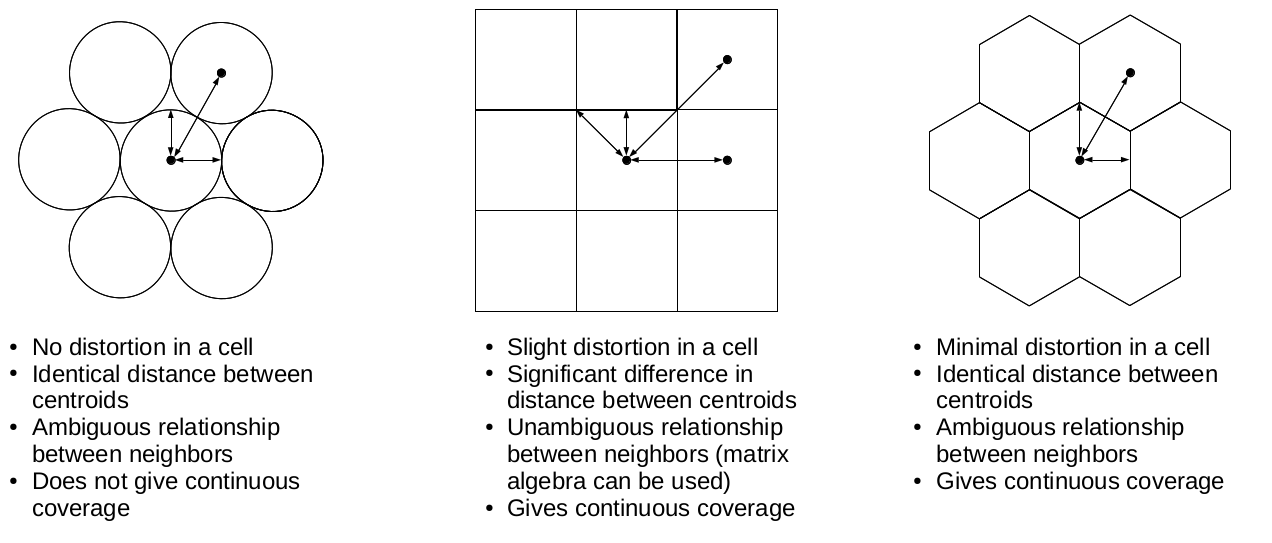

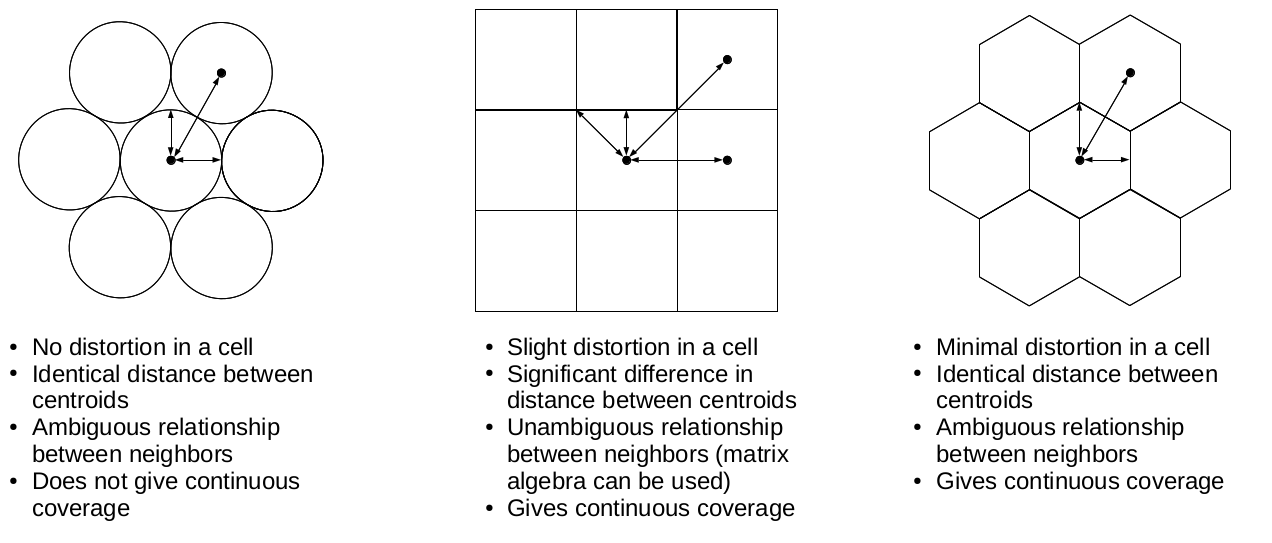

Furthermore, cells don't have to be squares. It is common practice to have different resolutions in different dimensions. Rasters with rectangular cells are supported by QGIS, and many other open source GIS clients. Rasters don't even need to have four sides. The distortions (we can call it sampling bias in some cases, mostly in statistics) caused by four-sided raster cells can be minimized with hexagons, regular shapes with the most sides capable of a complete coverage:

Okay, but can rasters only store a single thematic? No, rasters can have multiple bands, and we can even combine them to create RGB visualizations. Finally, as we contradicted almost every rule of the raster data model, do individual cells need to coincide (have the same resolution)? Well, technically, yes, but guess what? There are studies about a multi-resolution image format, which can store rasters with different sizes in the same layer. It's now only a matter of professional and business interest to create that format.

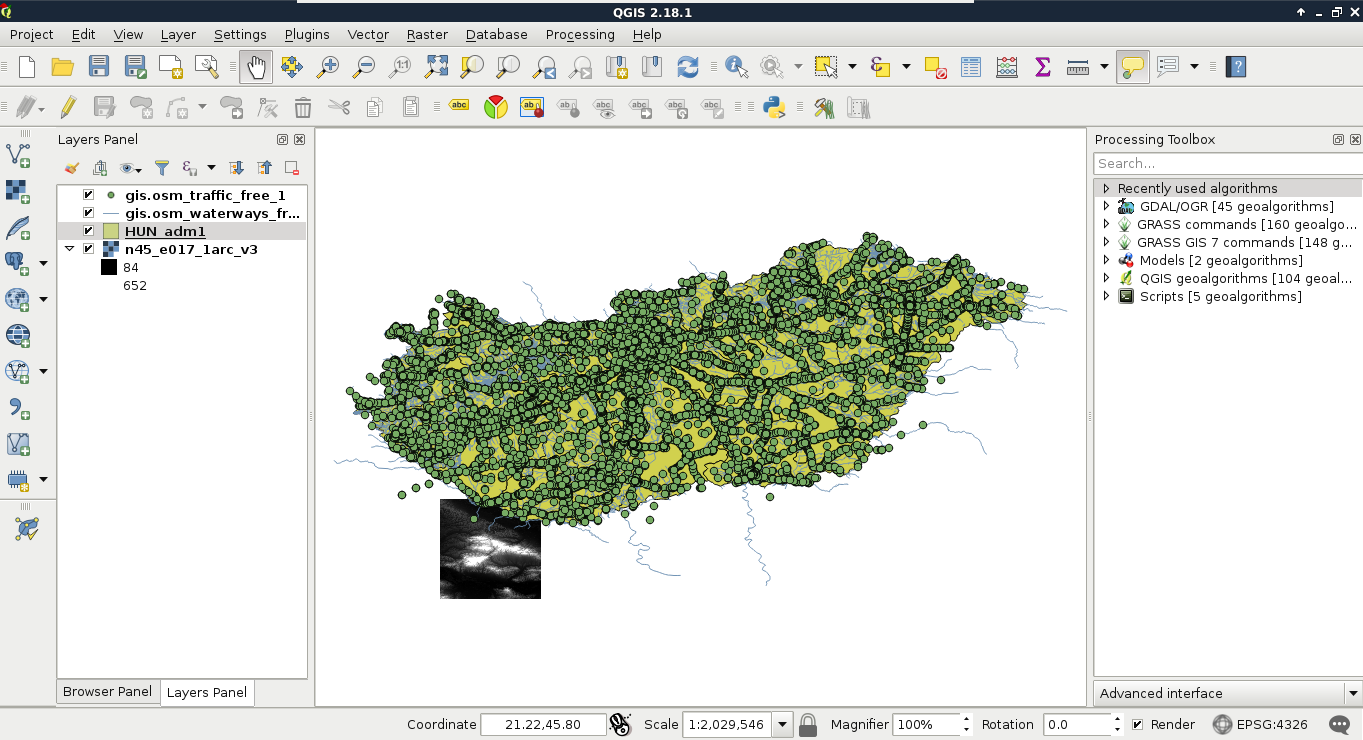

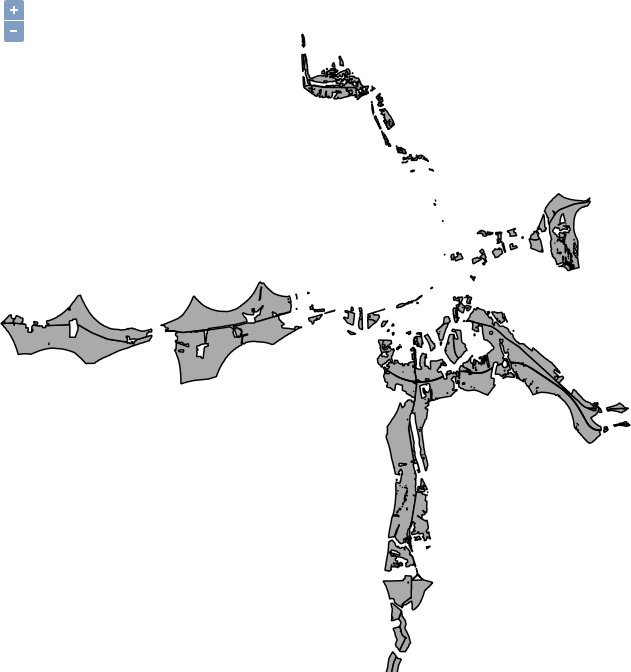

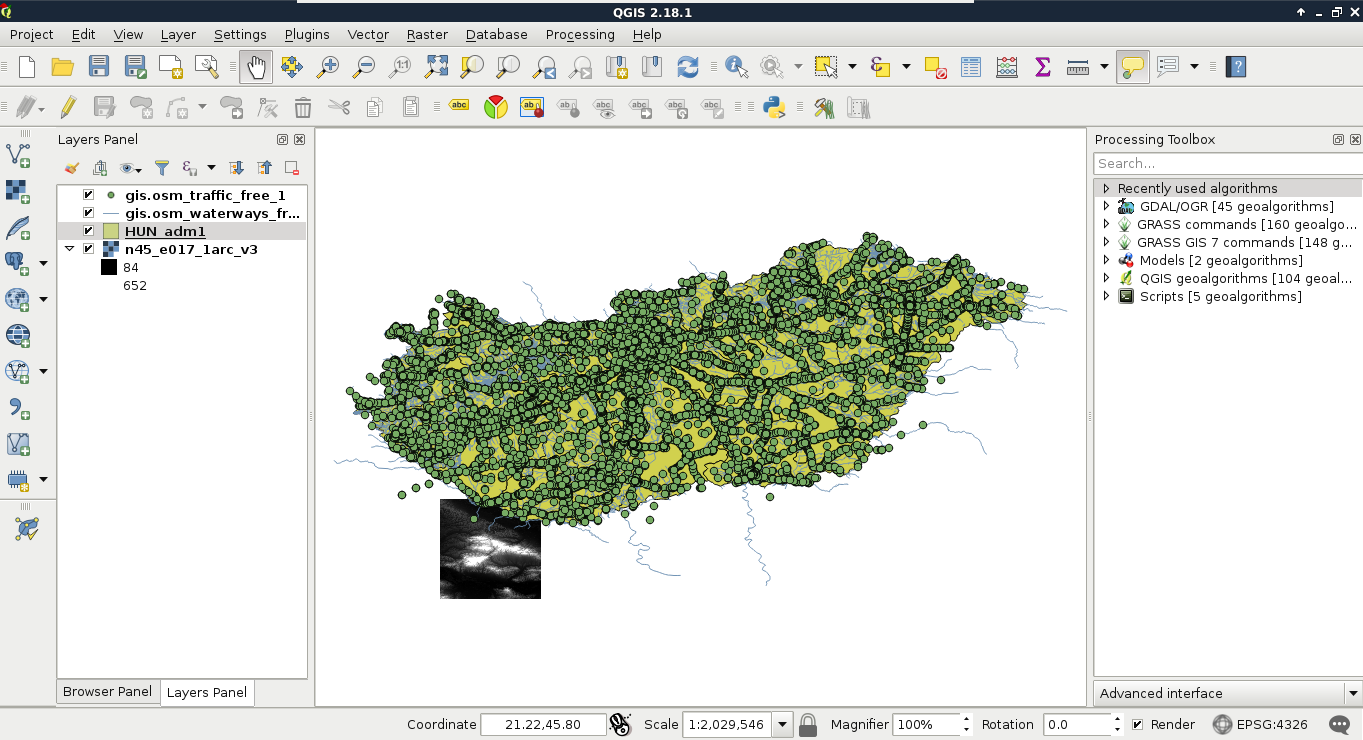

Now that you've learned the basics of raster data, let's examine vector data. This is the other fundamental data type which is used in GIS. Let's get some vector data at the top of that srtm layer. From the Browser Panel, we open up the administrative boundaries layer (the one with the shp extension) containing our study area, and the waterways and traffic layers from the OpenStreetMap data. We can also use the Add Vector Layer button from the side toolbar:

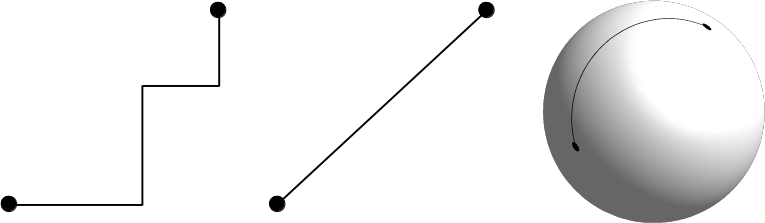

Now there are three vector layers with three different icons and representation types on our canvas. These are the three main vector types we can work with:

If we zoom around, we can see that unlike the raster layer, these layers do not pixelate. They remain as sharp as on lower zoom levels no matter how far we zoom in. Furthermore, if we use the Identify Features tool and click on a feature, it gets selected. We can see with this that our vector layers consist of arbitrary numbers of points, lines, and irregular shapes:

Vector data, unlike raster data, does not have a fixed layout. It can be represented as sets of coordinate pairs (or triplets or quads if they have more than two dimensions). The elementary unit of the vector data model is the feature. A feature represents one logically coherent real-world object--an entity. What we consider an entity depends on our needs. For example, if we would like to analyze a forest patch, we gather data from individual trees (entities) and represent them as single points (features). If we would like to analyze land cover, the whole forest patch can be the entity represented by a feature with a polygon geometry. We should take care not to mix different geometry types in a single layer though. It is permitted in some GIS software; however, as some of the geoprocessing algorithms only work on specific types, it can ruin our analysis.

Geometry is only part of a vector feature. To a single feature, we can add an arbitrary number of attributes. There are two typical distinct types of attributes--numeric and character string. Different GIS software can handle different subtypes, like integers, floating point numbers, or dates (which can be a main type in some GIS). From these attributes, the GIS software creates a consistent table for every vector layer, which can be used to analyze, query, and visualize features. This attribute table has rows representing features and typed columns representing unique attributes. If at least one feature has a given attribute, it is listed as a whole column with NULL values (or equivalent) in the other rows. This is one of the reasons we should strive for consistency no matter if the used GIS software forces it.

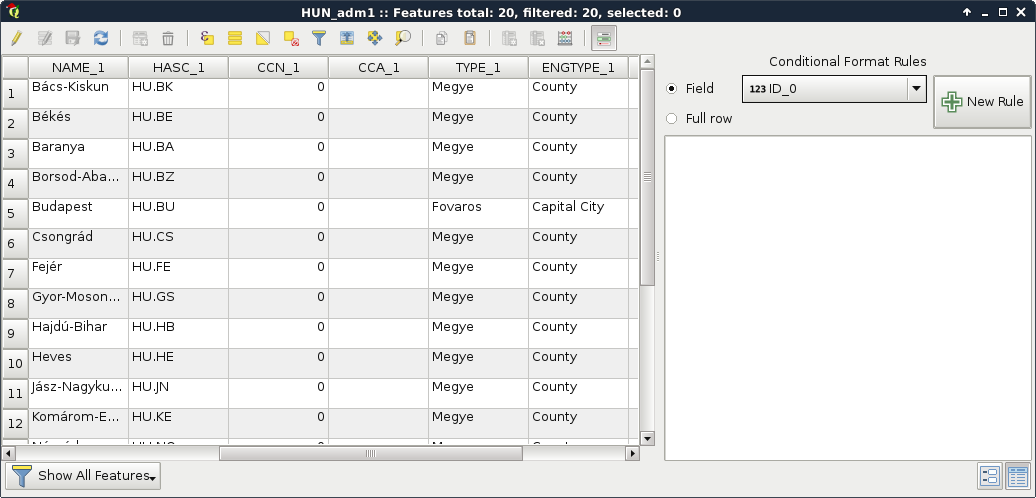

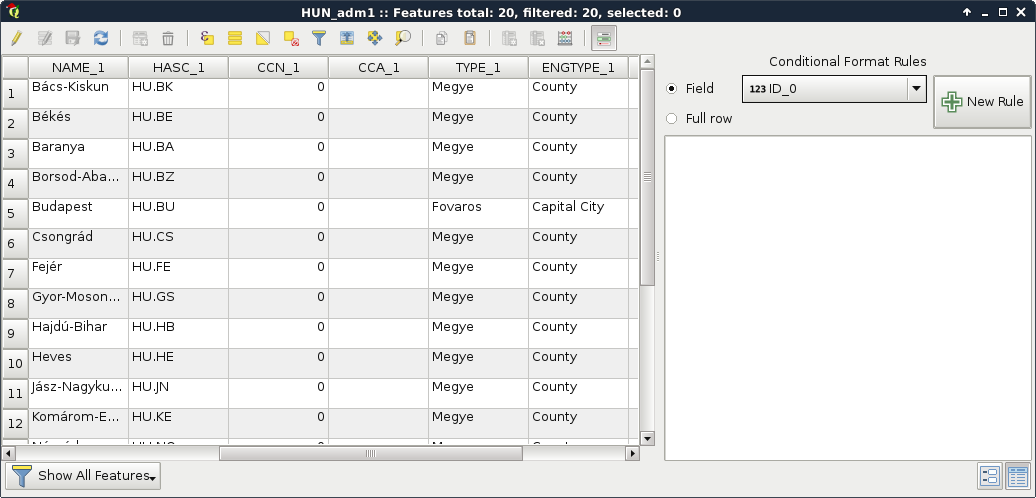

Let's open an attribute table by right-clicking on a vector layer in the Layers Panel and selecting Open Attribute Table. If we open the Conditional formatting panel in the attribute table, we can also see the type of the columns, as shown in the following screenshot:

To sum up, with the vector data model, we can represent entities with shapes consisting of nodes (start and end points) and vertices (mid points) which are coordinates. We can link as many attributes to these geometries as we like (or as the data exchange format permits). The model implies that we can hardly store gradients, as it is optimized to store discrete values associated with a feature. It has a somewhat constant accuracy as we can project the nodes and vertices one by one. Furthermore, the model does not suffer from distortions unlike the raster data model.

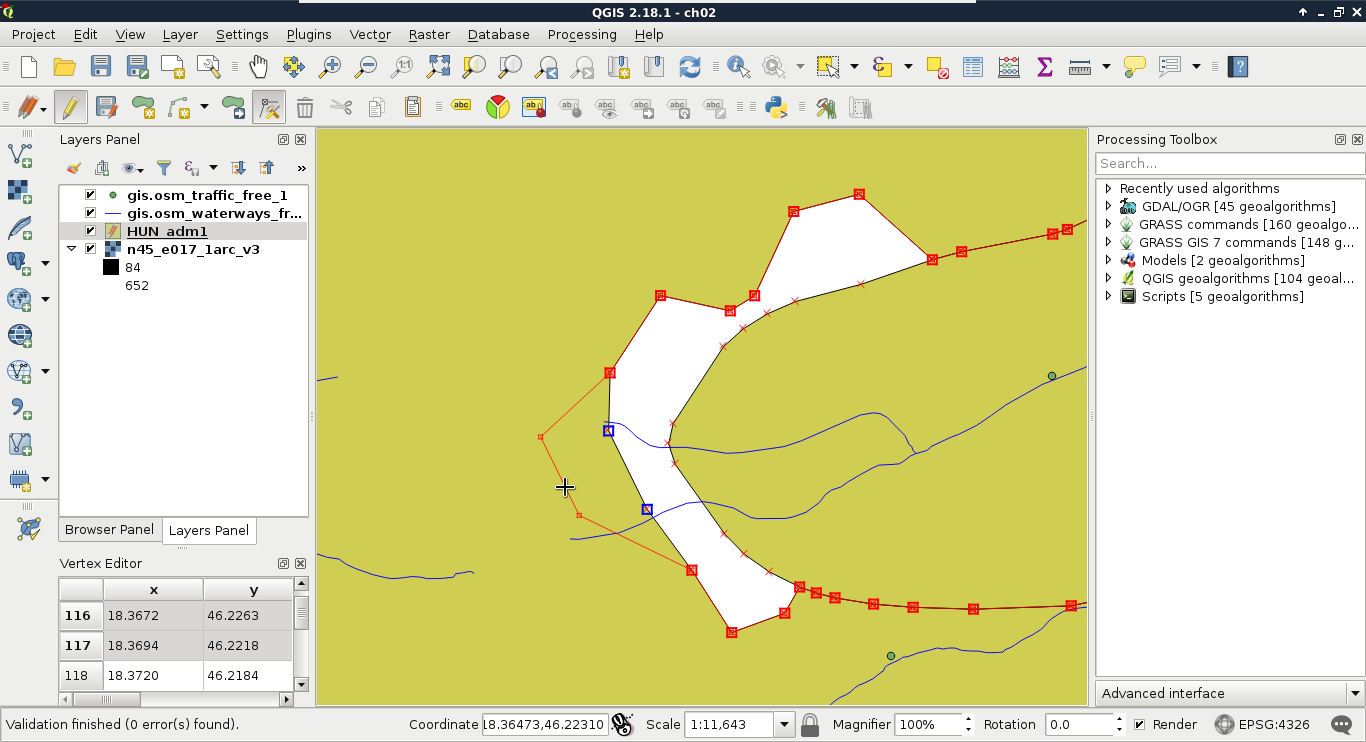

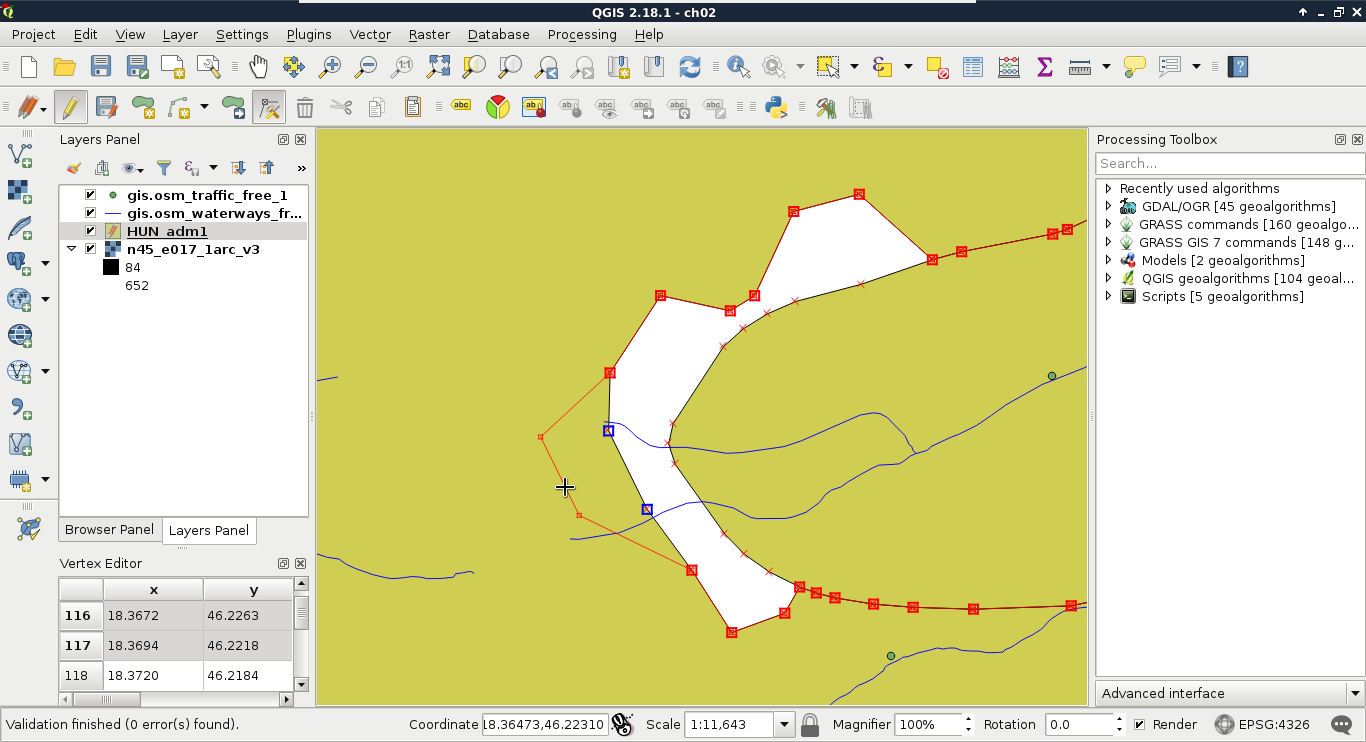

As vector geometries do not have a fixed layout, we can edit our features. Let's try it out by selecting the administrative boundaries layer in the Layers Panel and starting an edit session with the Toggle Editing tool.

We can see every node and vertex of our layer. We can modify these points to reshape our layer. Let's zoom in a little bit to see the individual vertices. From the now enabled editing tools, we select the Node Tool. If we click in a polygon with this tool, we can see its vertices highlighted and a list of numbers in the left panel. These are the coordinates of the selected geometry. We can move vertices and segments by dragging them to another part of the canvas. If we move some of the vertices from the neighboring polygon, we can see a gap appearing. This naive geometry model is called the Spaghetti model. Every feature has their sets of vertices individually and there isn't any relationship between them. Consider the following screenshot:

Finally, let's stop the edit session by clicking on the Toggle Editing button again. When it asks about saving the modifications, we should choose Stop without Saving and QGIS automatically restores the old geometries.

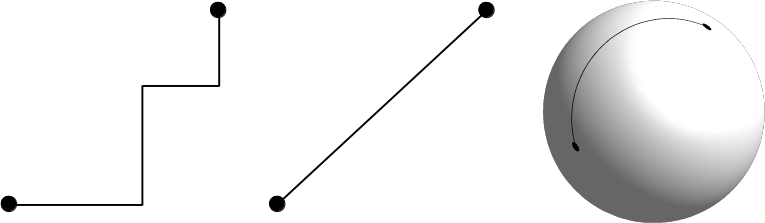

More complex geometries have more theoretical possibilities, which leads to added complexity. Defining a point is unequivocal, that is, it has only one coordinate tuple. Multi-points and line strings are neither much more complex--they consist of individual and connected coordinate tuples respectively. Polygons, on the other hand, can contain holes, the holes can contain islands (fills), and theoretically, these structures can be nested infinitesimally. This structure adds a decent complexity for a GIS software. For example, QGIS only supports polygons to the first level--with holes.

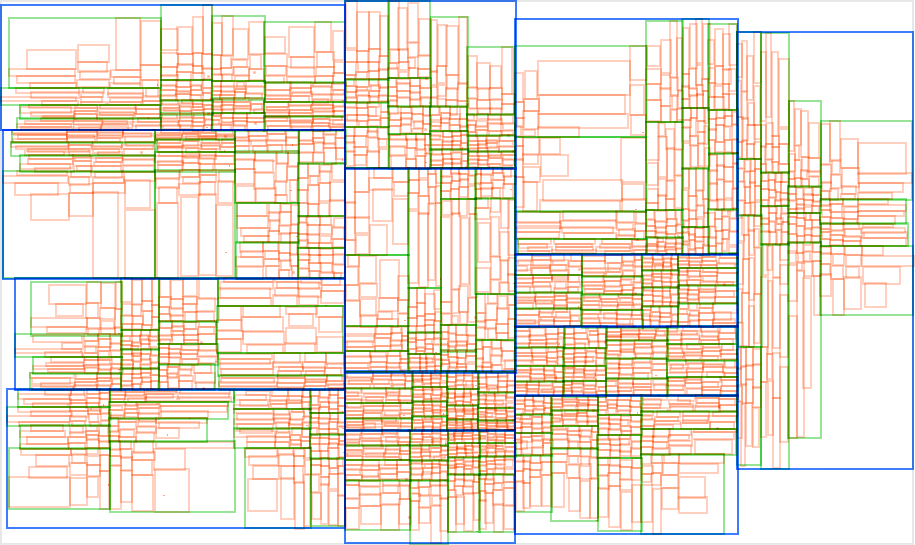

The real complexity, however, only comes with topology. Different features in a layer can have relationships with each other. For example, in our administrative boundary layer, polygons should share borders. They shouldn't have gaps and overlaps. Another great example is a river network. Streams flow into rivers, rivers flow into water bodies. In a vector model, they should be connected like in the real world.

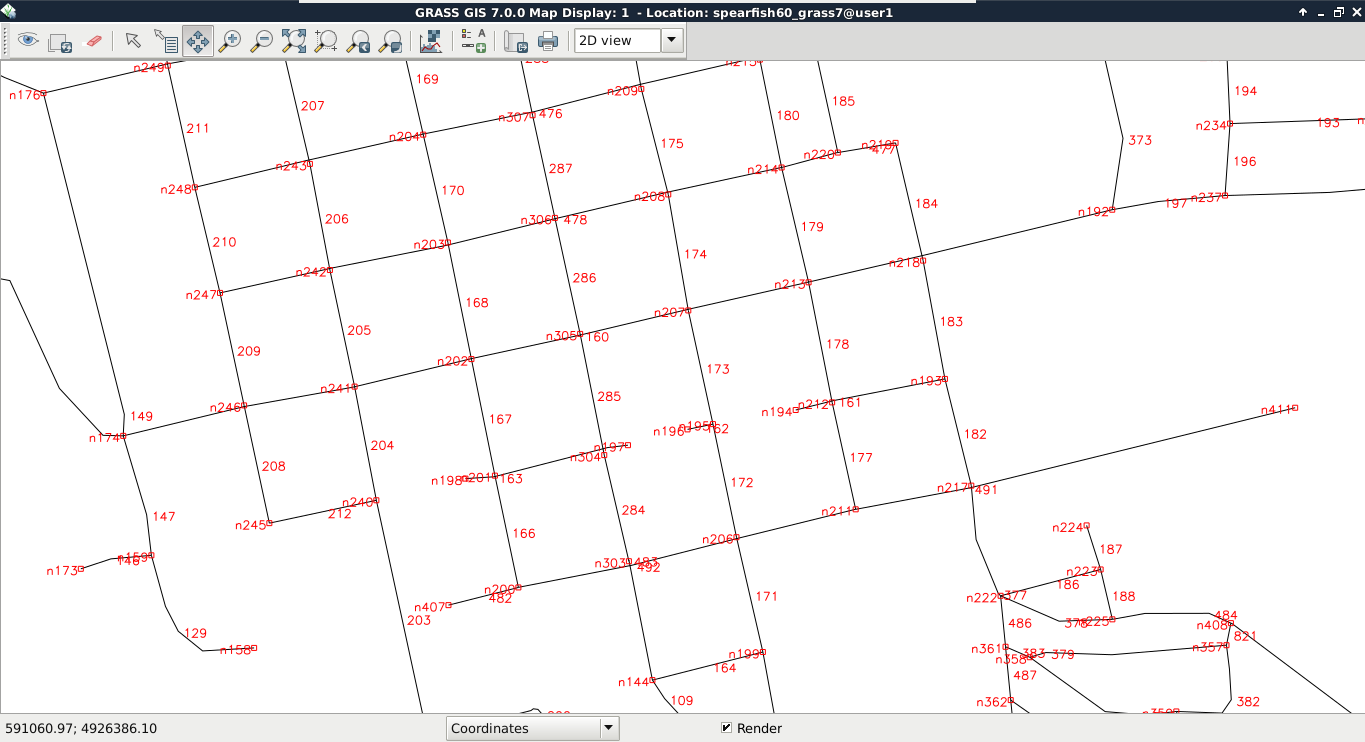

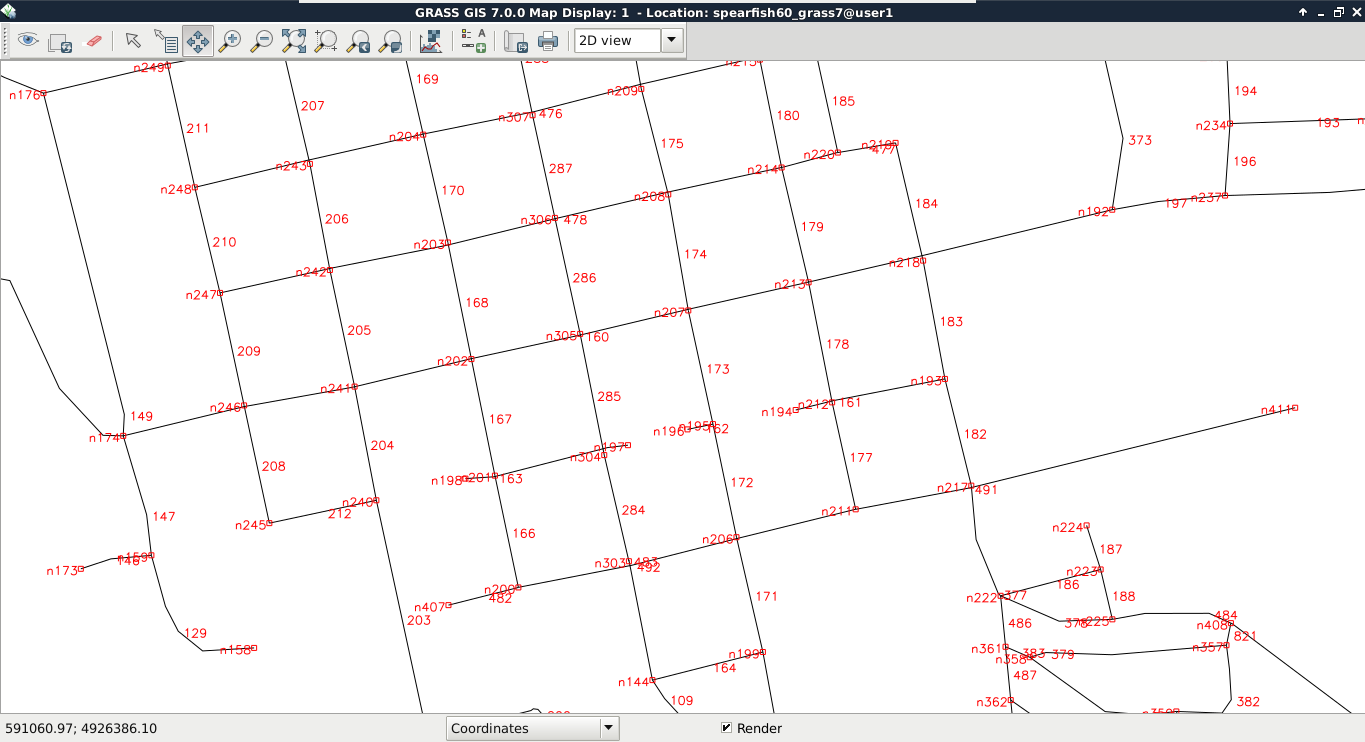

The topological geometry model (or vector model) is the sophisticated way to solve these kinds of relational problems. In this model, points are stored as nodes while other geometries form a hierarchical structure. Line segments contain references to nodes, line strings, and polygons consist of references to segments. By using this hierarchical structure, we can easily handle relationships. This way, if we change the position of a node, every geometry referring to the node changes. Take a look at the following screenshot:

Not every GIS software enforces a topological model. For example, in QGIS, we can toggle topological editing. Let's try it out by checking Enable topological editing in Settings | Snapping Options. If we edit the boundaries layer again, we can see the neighboring feature's geometry following our changes.

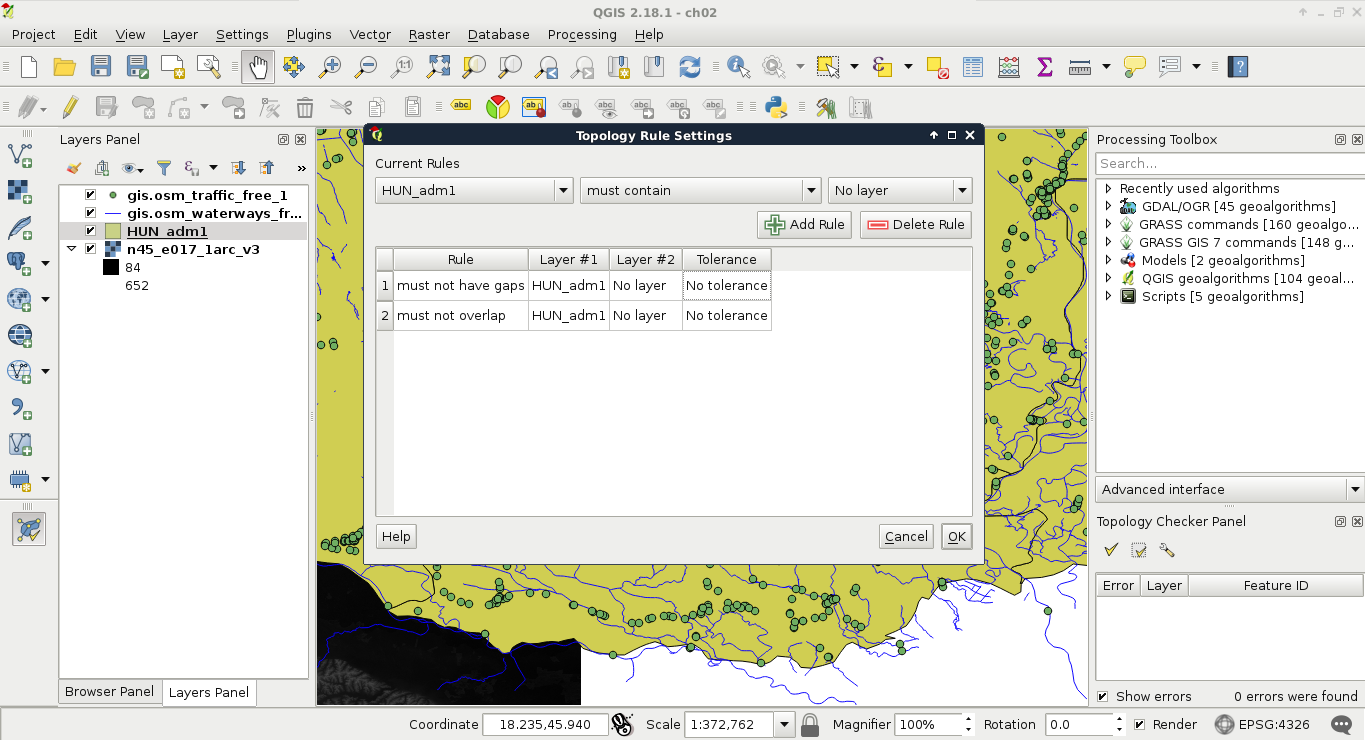

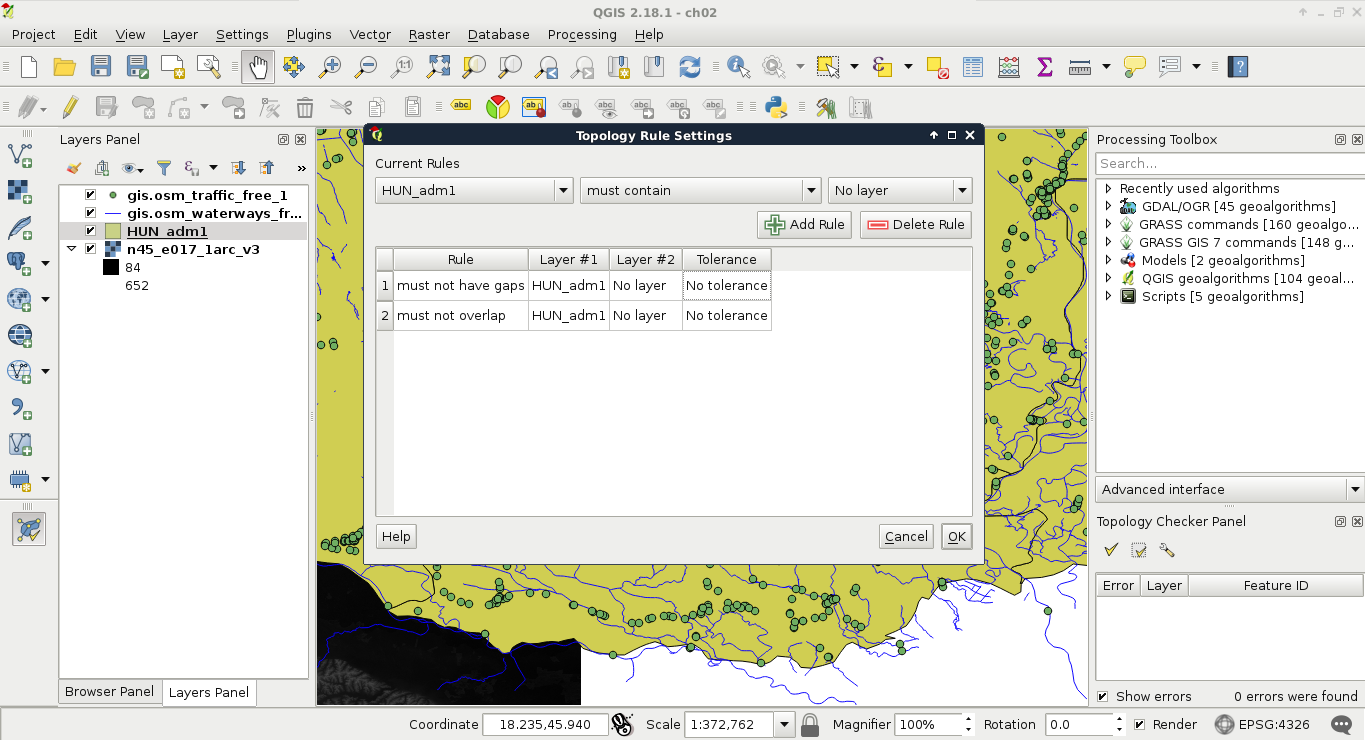

While QGIS does not enforce a topological model, it offers various tools for checking topological consistency. One of the tools is the built-in Topology Checker plugin. We can find the tool under the Add layer buttons.

If we activate the tool, a new panel appears docked under the Processing Toolbox. By clicking on Configure, we can add some topology rules to the opened vector layers. Let's add two simple rules to the administrative boundaries layer--they must not have gaps or overlaps. Consider the following screenshot:

The only thing left to do is to click on the Validate All or Validate Extent button. If we have some errors, we can navigate between them by clicking on the items one by one.

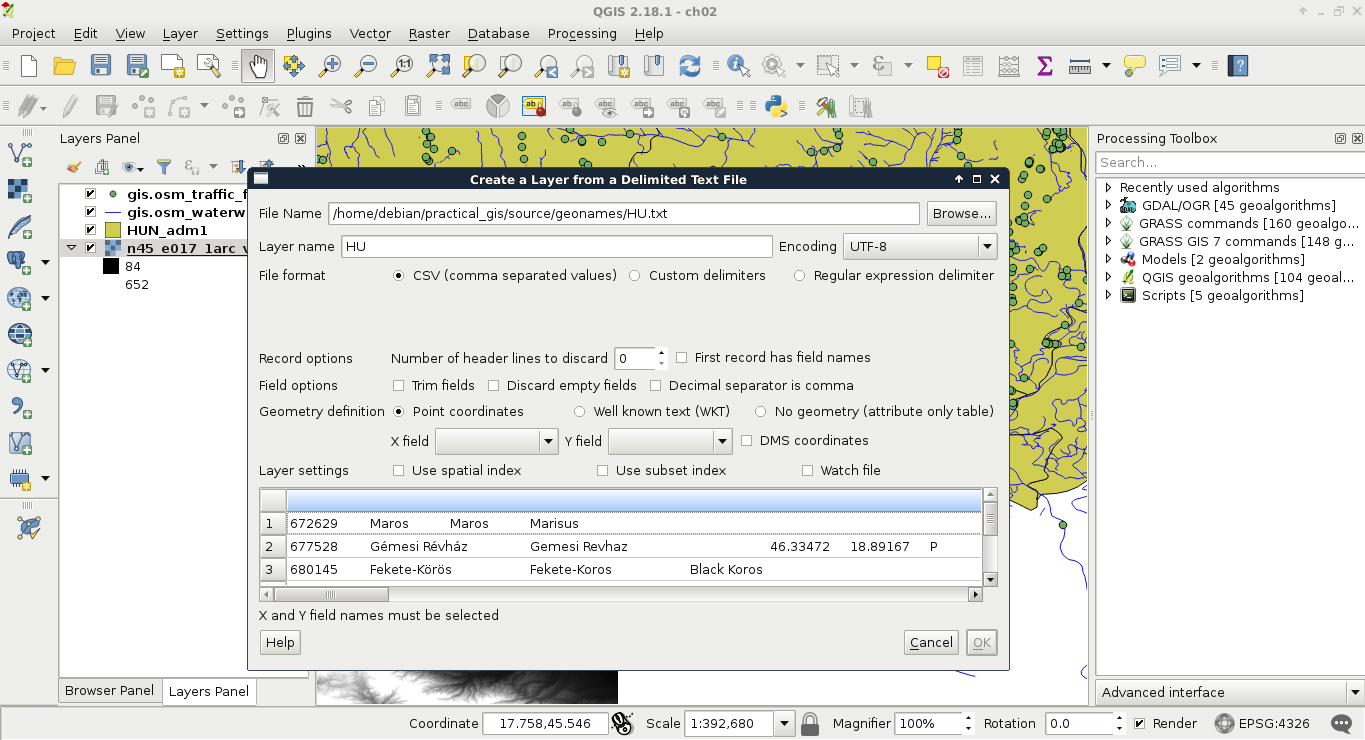

The vector layers we opened so far were dedicated vector data exchange formats; therefore, they had every information coded in them needed for QGIS to open them. There are some cases when we get some data in a tabular format, like in a spreadsheet. These data usually contain points as coordinates in columns and attributes in other columns. They do not store any metadata about the vectors, which we have to gather from readme files, or the team members producing the data.

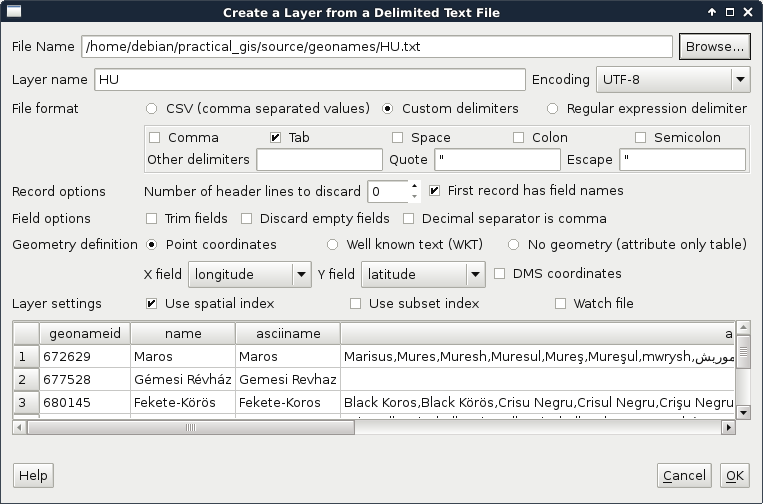

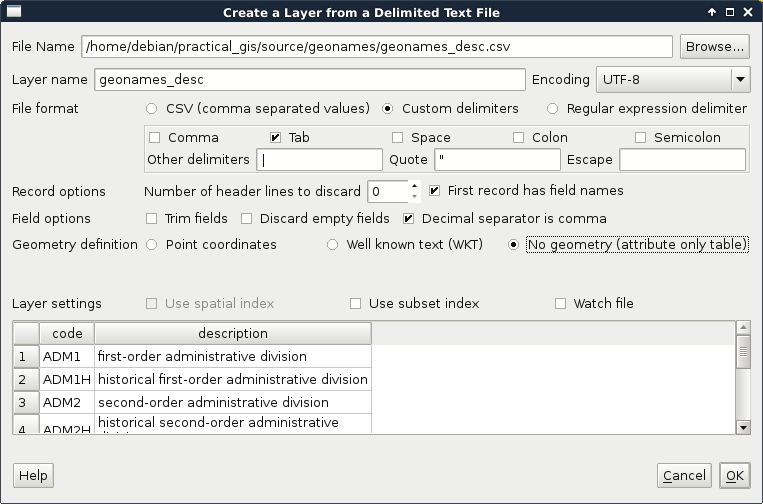

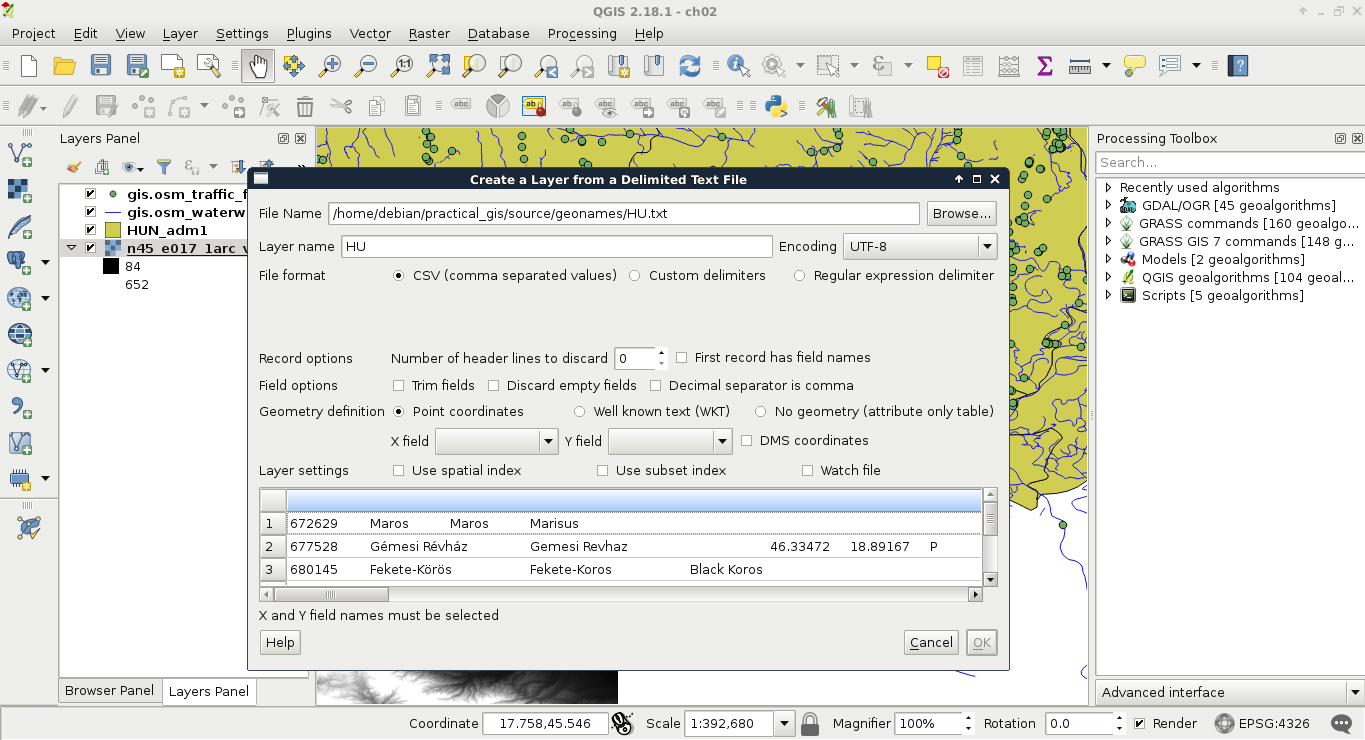

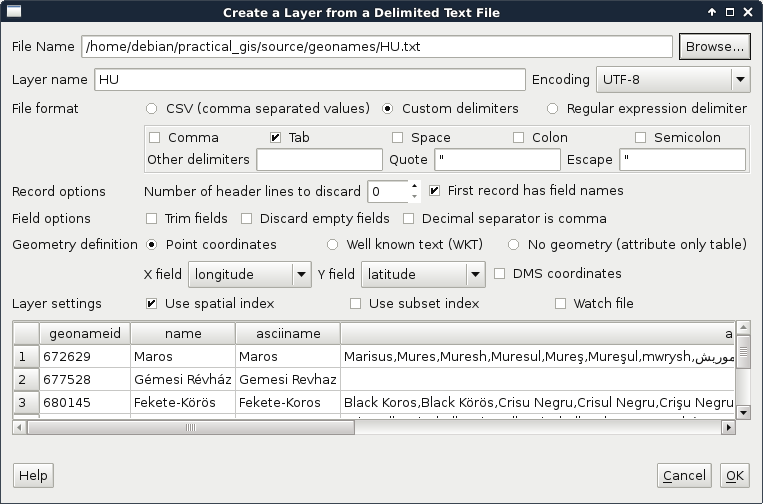

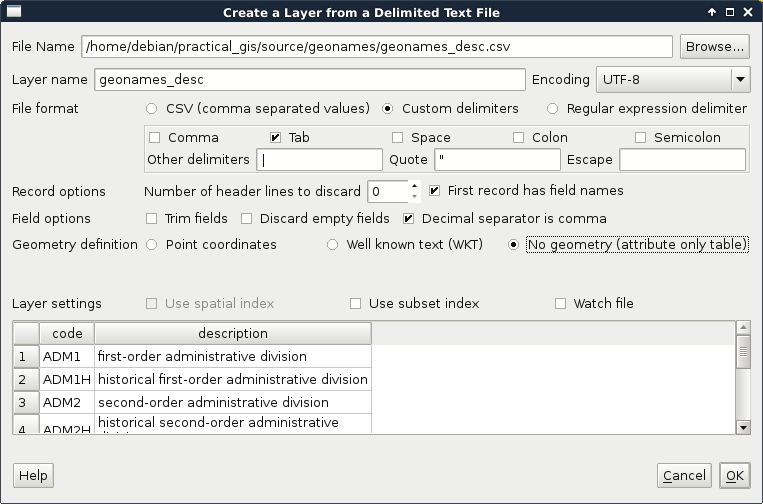

QGIS can handle one tabular format--CSV (Comma Separated Values), which is an ASCII file format, a simple text file containing tabular data. Every row is in a new line, while fields are separated with an arbitrary field separator character (the default one is the comma). The layout of such a layer is custom; therefore, we need to supply the required information about the table to QGIS. If we try to drag our GeoNames layer to the canvas, QGIS yields to a Layer is not valid error. To open these files, we need to use the Add Delimited Text Layer tool from the sidebar (comma icon):

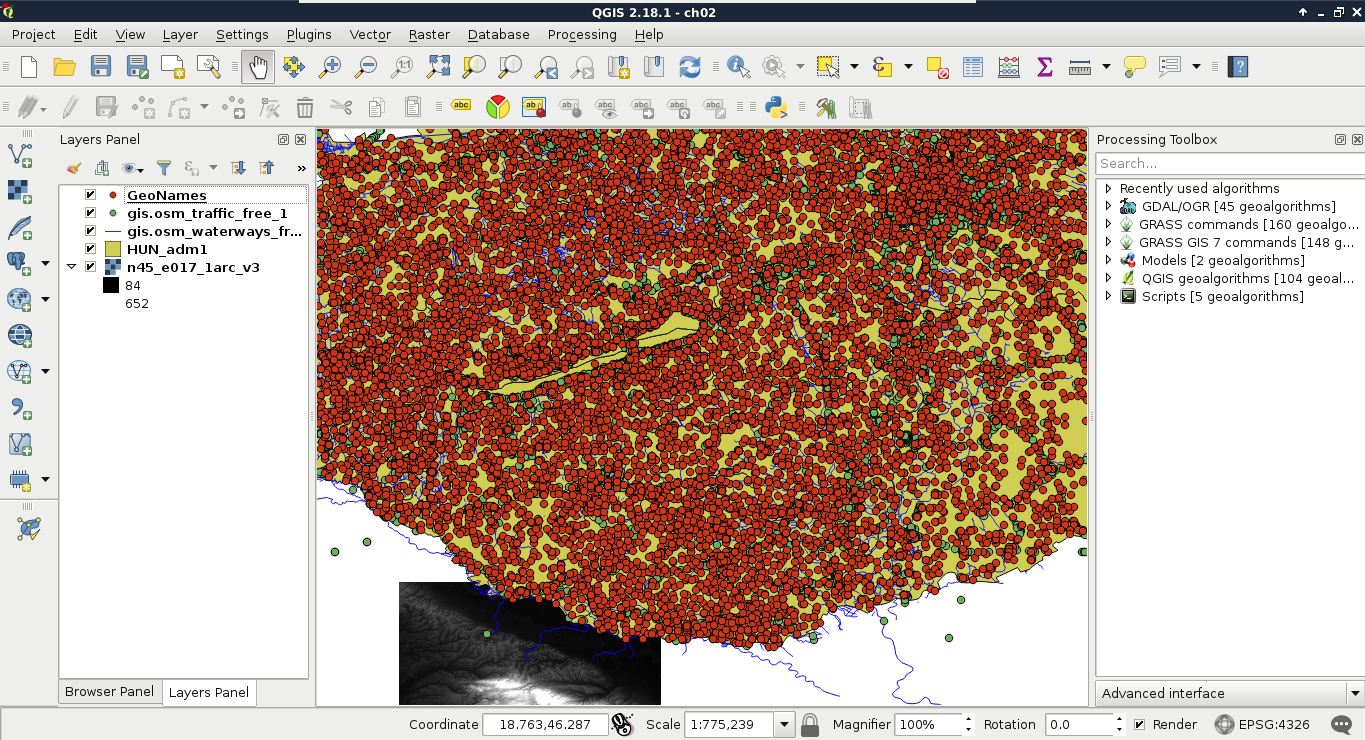

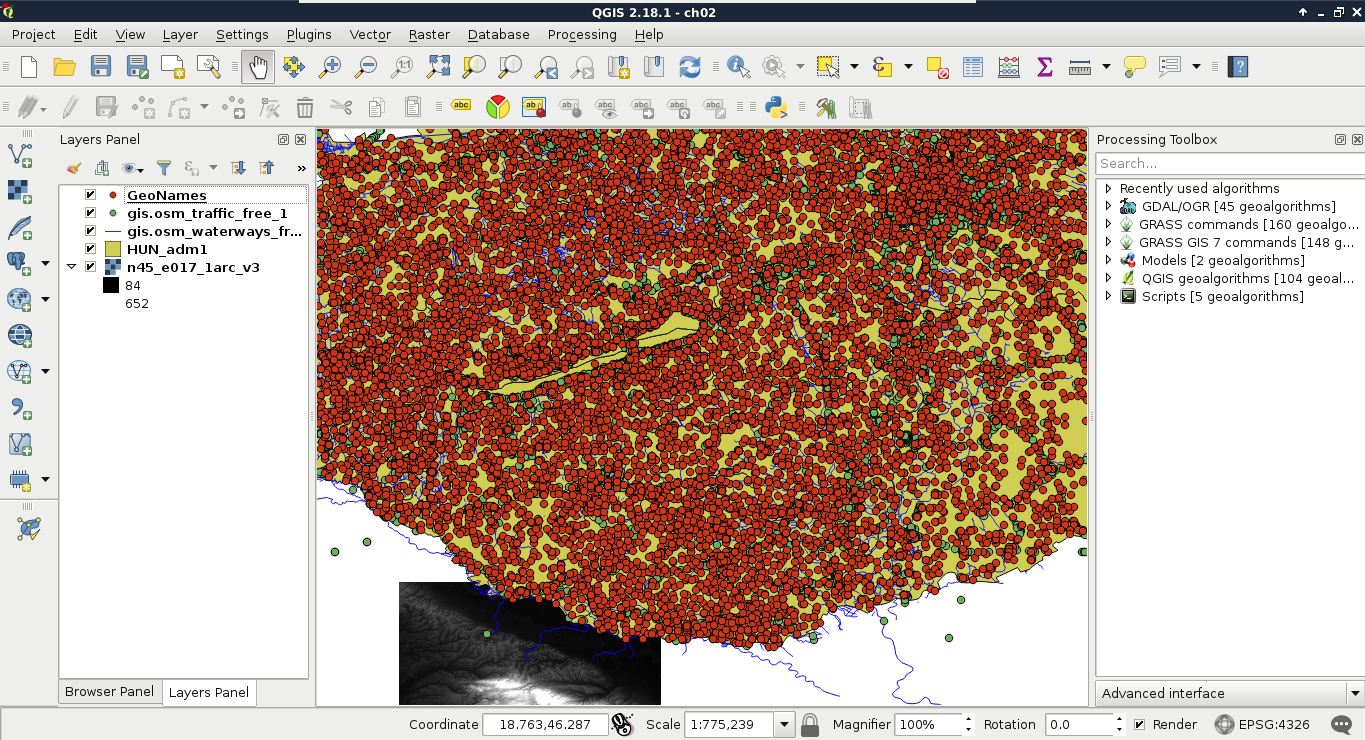

If we browse our GeoNames table, we can see that QGIS automatically creates a preview from the accessed data. We can also see that the preview is far from correct. It's time to consult the readme file coming with the GeoNames extract. In the first few lines, we can see the most important information--The data format is tab-delimited text in utf8 encoding. Let's select Custom delimiters and check Tab as a delimiter. Now we only need to supply the columns containing the coordinates. We can see there are no headers in the data. However, as the column descriptions are ordered in the readme file, we can conclude that the fifth column contains the latitude data (Y field), while the sixth column contains the longitude data (X field). This is the minimum information we can add the layer with:

When zooming around the map, we could notice the Scale changing in the status bar. GIS software (apart from web mapping solutions) usually use scales instead of zoom levels. The map scale is an important concept of cartography, and its use was inherited by GIS software. The scale shows the ratio (or representative fraction) between the map and the real world. It is a mapping between two physical units:

For example, a Scale of 1:250,000 means 1 centimeter on the map is 2500 meters (250,000 centimeters) in the real world. However, as the map scale is unitless, it also means 1 inch on the map is 250,000 inches in the real world, and so on. With the scale of the map, we can make explicit statements about its coverage and implicit statements about its accuracy. Large scale maps (for example, with a scale of 1:10,000) cover smaller areas with greater accuracy than medium scale maps (for example, with a scale of 1:500,000), which cover smaller areas with greater accuracy than small scale maps (for example, with a scale of 1:1,000,000).

We can easily imagine scales on paper maps, although the rule is the same as on the map canvas. On a 1:250,000 map, one centimeter on our computer screens equals 2500 meters in the real world. To calculate this value, GIS software use the DPI (dots per inch) value of our screens to produce accurate ratios.

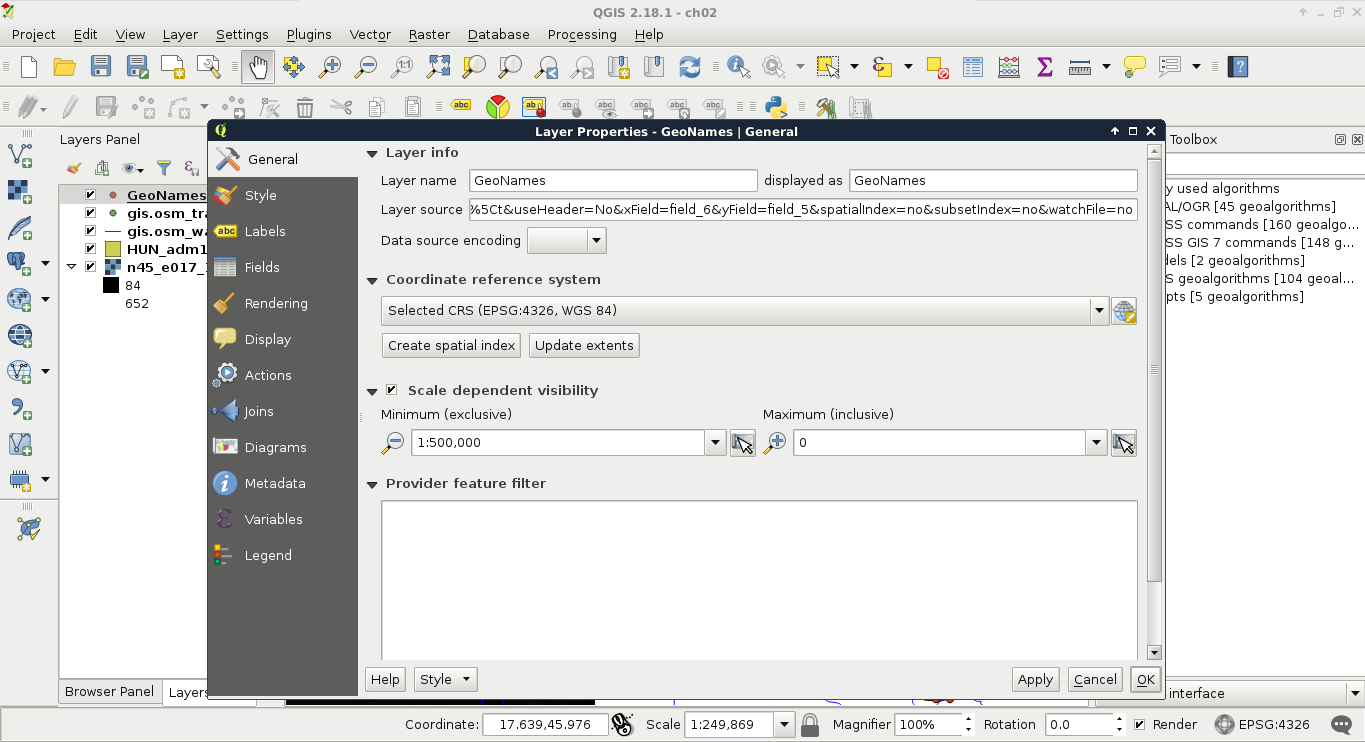

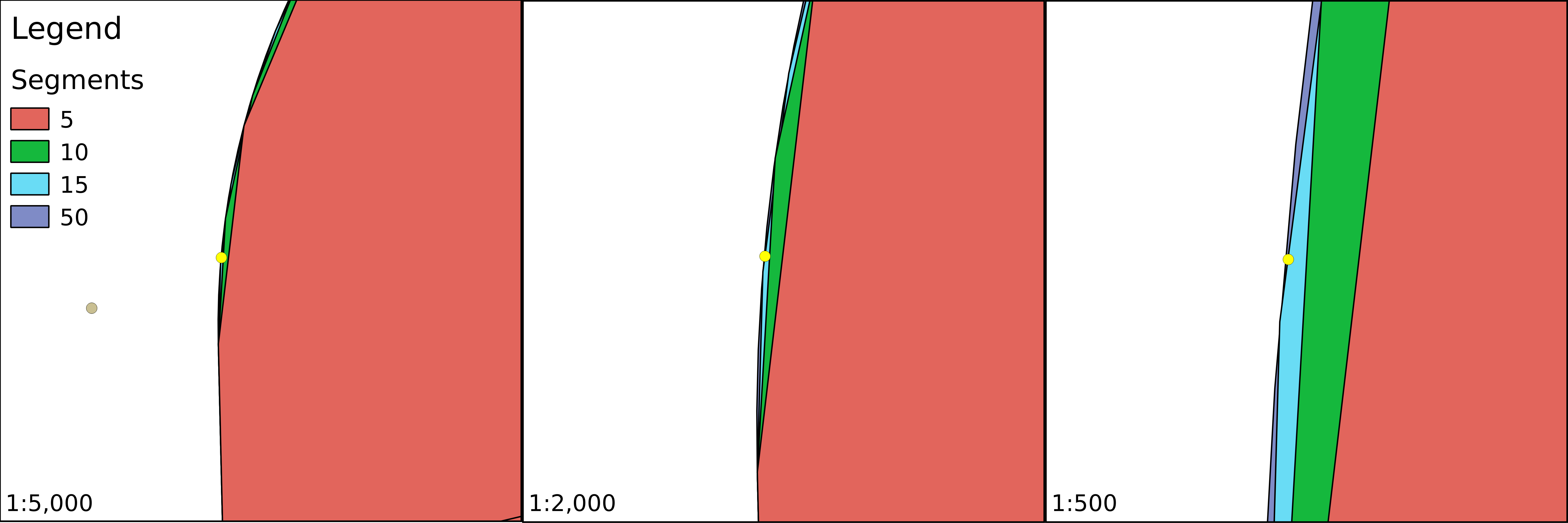

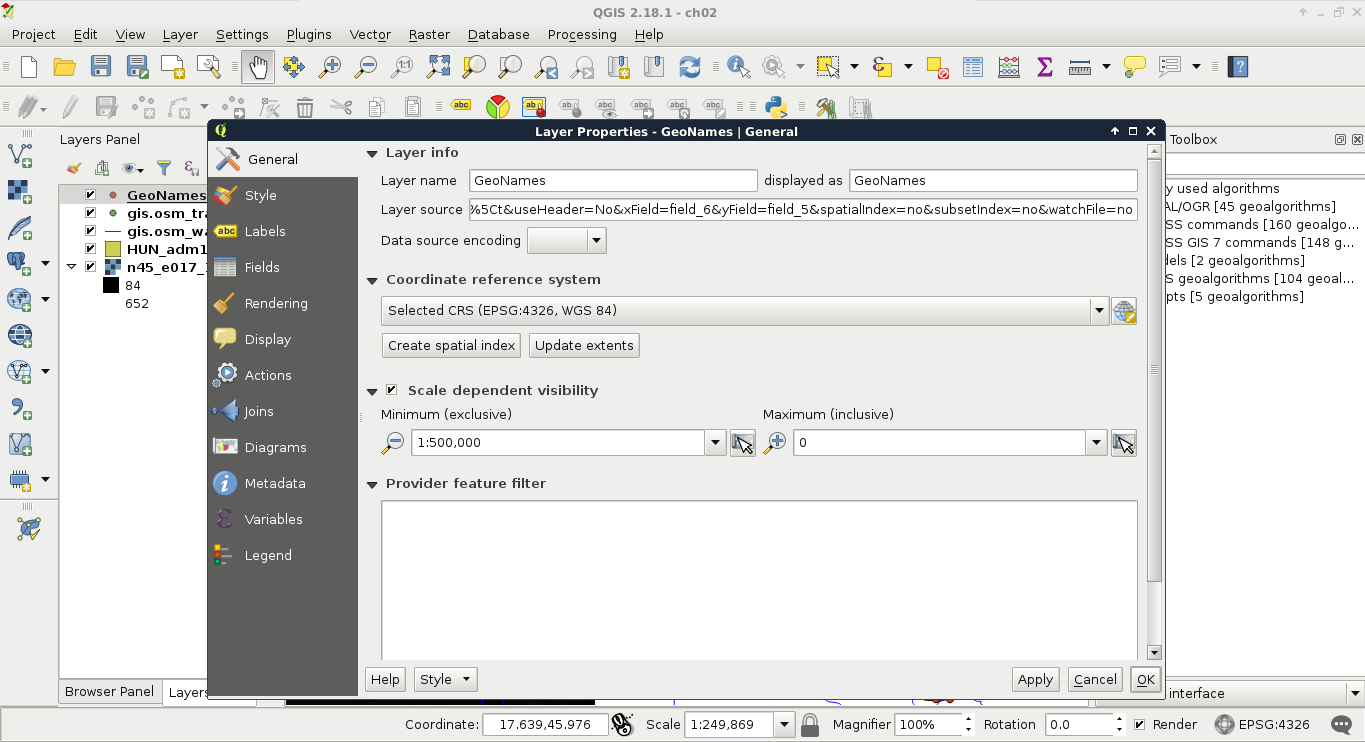

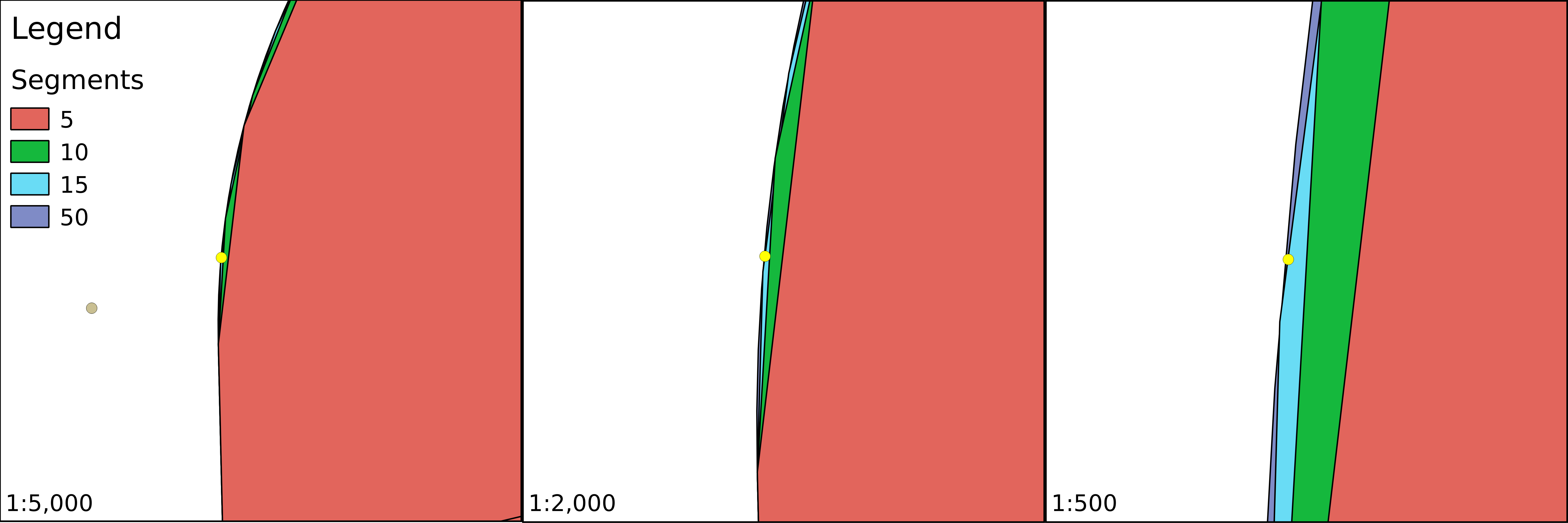

By using scales instead of fixed zoom levels, GIS software offers a great amount of flexibility. For example, we can arbitrarily change the Scale value on our status bar and QGIS automatically jumps to that given scale. The definition of map scale will follow us along during our work as QGIS (like most of the GIS software) uses scale definitions in every zoom-related problem. Let's see one of them--the scale dependent display. We can set the minimum and maximum scales for every layer and QGIS won't render them out of those bounds. Let's right-click on one of the layers and select Properties. Under the General tab, we can check Scale dependent visibility. After that, we can provide bounds to that layer. By providing a minimum value of 1:500,000 to the layer and leaving the maximum value unbounded (0), we can see the layer disappearing on 1:500,001 and smaller scales:

In this chapter, we acquainted ourselves with the GUI of QGIS and explained about data models in GIS. With this knowledge, it will be easier to come up with specific workflows later as we have an idea how the input data work and what we can do with it. We also learned about one of the mandatory cartographic elements--the map scale.

In the next chapter, we will use our vector data in another way. We will make queries on our vector layers by using both their attribute data and geometries. Finally, we will learn how to join the attributes of different layers in order to make richer layers and give ourselves more options on further visualization and analysis tasks.

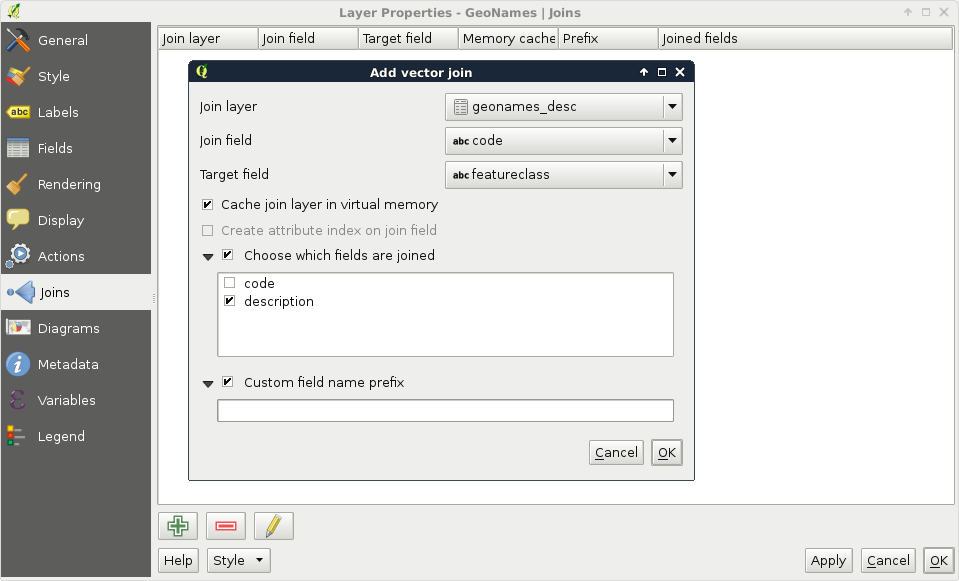

In the previous chapter, we learned how vector data compares to raster data. Although every feature can only represent one coherent entity, it is a way more powerful and flexible data model. With vectors, we can store a tremendous amount of attributes linked to an arbitrary number of features. There are some limitations but only with some data exchange formats. By using spatial databases, our limitations are completely gone. If you've worked on a study area with rich data, you might have already observed that QGIS has a hard time rendering the four vector layers for their entire extent. As we can store (and often use) much more data than we need for our workflow, we must be able to select our features of interest.

Sometimes, the problem is the complete opposite--we don't have enough data. We have features which lack just the attributes we need to accomplish our work. However, we can find other datasets with the required information, possibly in a less useful format. In those cases, we need to be able to join the attributes of the two layers, giving the correct attributes to the correct geometry types.

In this chapter, we will cover the following topics:

The first task in every work is to get used to the acquired data. We should investigate what kind of data it holds and what can we work with. We should formulate the most fundamental questions for successful work. Is there enough information for my analysis? Is it of the right type and format? Are there any No-Data values I should handle? If I need additional information, can I calculate them from the existing attributes? Some of these questions can be answered by looking at the attribute table, while some of them (especially when working with large vector data) can be answered by asking QGIS. To ask QGIS about vector layers, we have to use a specific language called SQL or Structured Query Language.

SQL is the query language of relational databases. Traditionally, it was developed to help make easy and powerful queries on relational tables. As attribute data can be considered tabular, its power for creating intuitive queries on vector layers is unquestionable. No matter if some modern GIS software uses an object-oriented structure for working with vector data internally, the tradition of using SQL, or near-SQL syntax for creating simple queries has survived. This language is very simple at its core, thus, it is easy to learn and understand. A simple query on a database looks like the following:

SELECT * FROM table WHERE column = value;

It uses the * wildcard for selecting everything from the table named table, where the content of the column named column matches value. In GIS software, like QGIS, this line can be translated to the following:

SELECT * FROM layer WHERE column = value;

Furthermore, as basic queries only allow selecting from one layer at a time, the query can be simplified as the software knows exactly which layer we would like to query. Therefore, this simple query can be formulated in a GIS as follows:

column = value

There is one final thing we have to keep in mind. Based on the software we use, these queries can be turned into real SQL queries used on internal relational tables, or parsed into something entirely different. As a result, GIS software can have their own SQL flavor with their corresponding syntactical conventions. In QGIS, the most important convention is how we differentiate column names from regular strings. Column names are enclosed in double quotation marks, while strings are enclosed in single ones. If we turn the previous query into a QGIS SQL syntax and consider value as a string, we get the following query:

"column" = 'value'

There are usually two kinds of selection methods in GIS software. There is one which highlights the selected features, making them visually distinguishable from an other one. Selected features by this soft selection method may or may not be the only candidates for further operations based on our choice. However, there is usually a hard selection called filtering. The difference is that the filtered-out features do not appear either on the canvas or in the attribute table. QGIS makes sure to exclude the filtered-out features from every further operation like they weren't there in the first place. There is one important difference between the style of selection and filtering--we can select features with the mouse; however, we can only filter with SQL expressions.

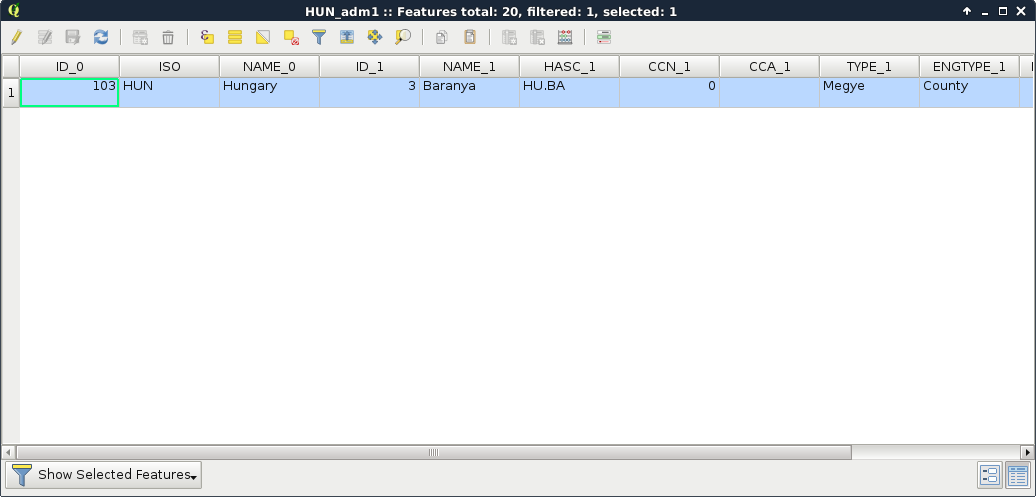

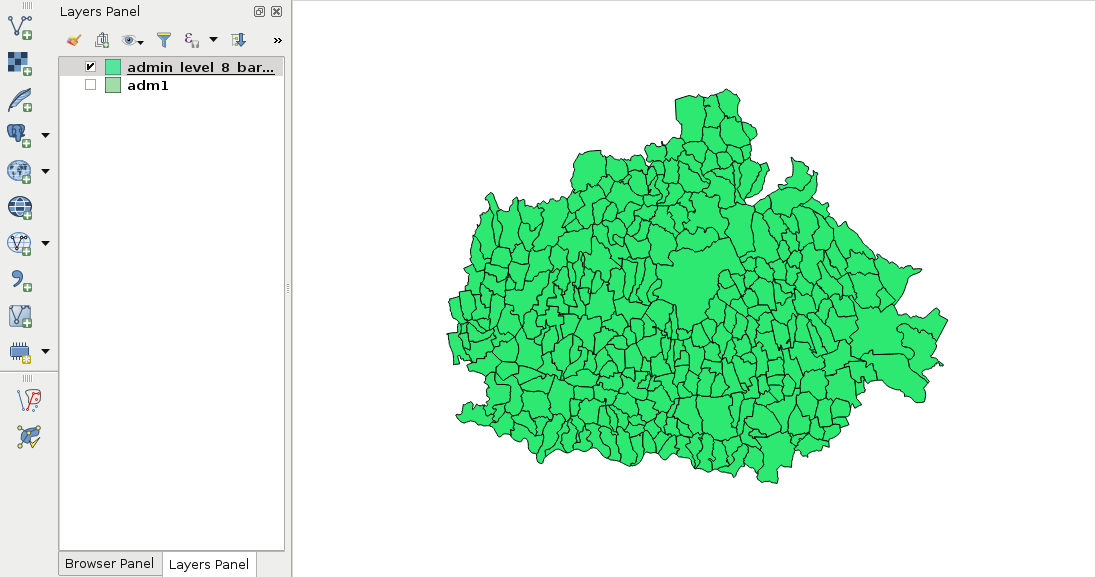

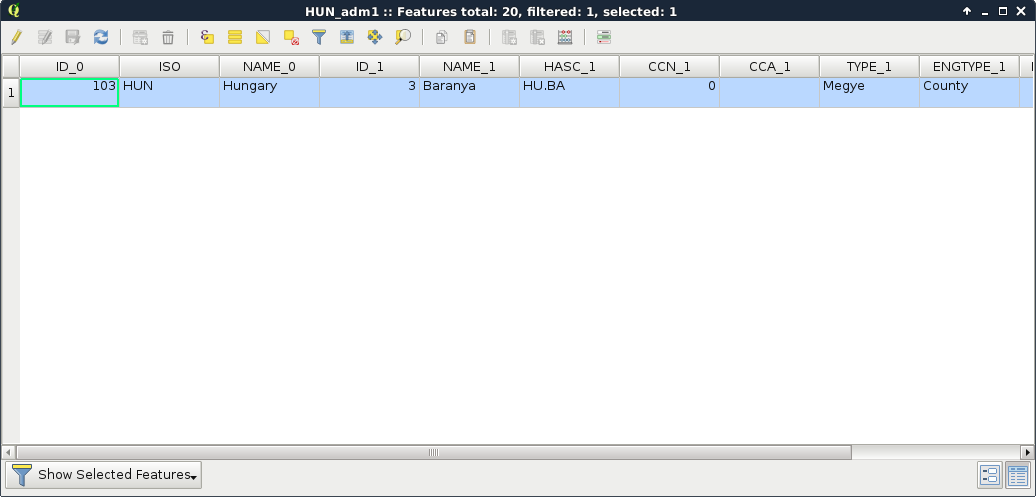

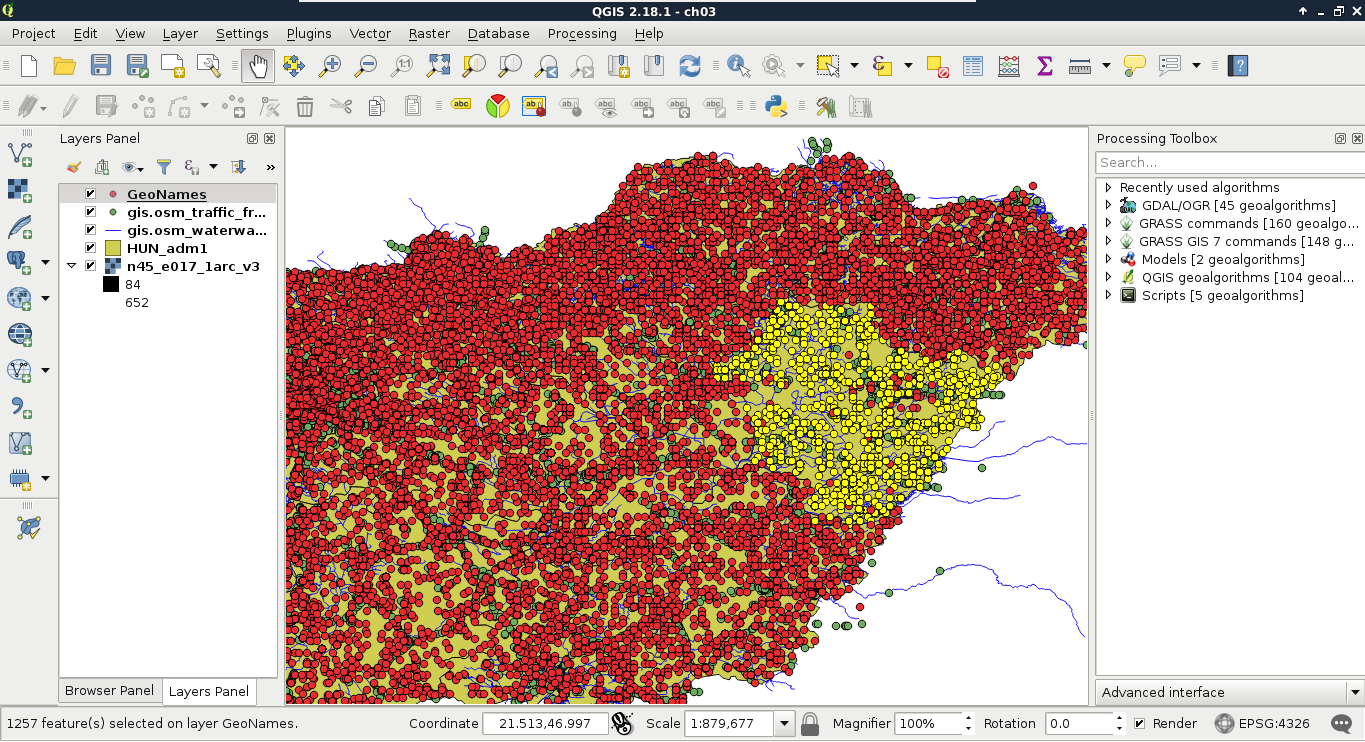

First, let's select a single feature with the mouse. To select features in QGIS, we have to select the vector layer containing the feature in the Layers Panel. Let's select the administrative boundaries layer then click on the Select Features by area or single click tool. Now we can select our study area by clicking it on the map canvas, as shown in this screenshot:

We can see the feature highlighted on the map and in the attribute table. If we open the attribute table of the layer, we can see our selected one distinguished as we have only a limited number of features in the current layer. If there are a lot of features in a layer, inspecting the selected features in the attribute table becomes harder. To solve this problem, QGIS offers an option to only show the selected features. To enable it, click on the Show All Features filter and select Show Selected Features:

The attribute table and the map canvas are interlinked in QGIS. If you click on the row number of a feature, it becomes selected and therefore, highlighted on the canvas.

From the currently opened vector layers, the GeoNames layer has the largest attribute table with the most kinds of attributes. However, as the extract does not contain headers, it is quite hard to work with it. Fortunately, CSV files can be edited as regular text files or as spreadsheets. As the first step, let's open the GeoNames file with a text editor and prepend a header line to it. It is tab delimited; therefore, we need to separate the field names with tabs. The field names can be read out from the readme file in order. In the end, we should have a first line looking something like this:

geonameid name asciiname alternatenames latitude longitude

featureclass

featurecode countrycode cc2 admin1 admin2 admin3 admin4 population

elevation

dem timezone modification

Now we can remove our GeoNames layer from the layer tree and add it again. In the form, we have to check the option First record has field names. If we do so, and name the latitude and longitude fields accordingly, we can see QGIS automatically filling the X and Y fields:

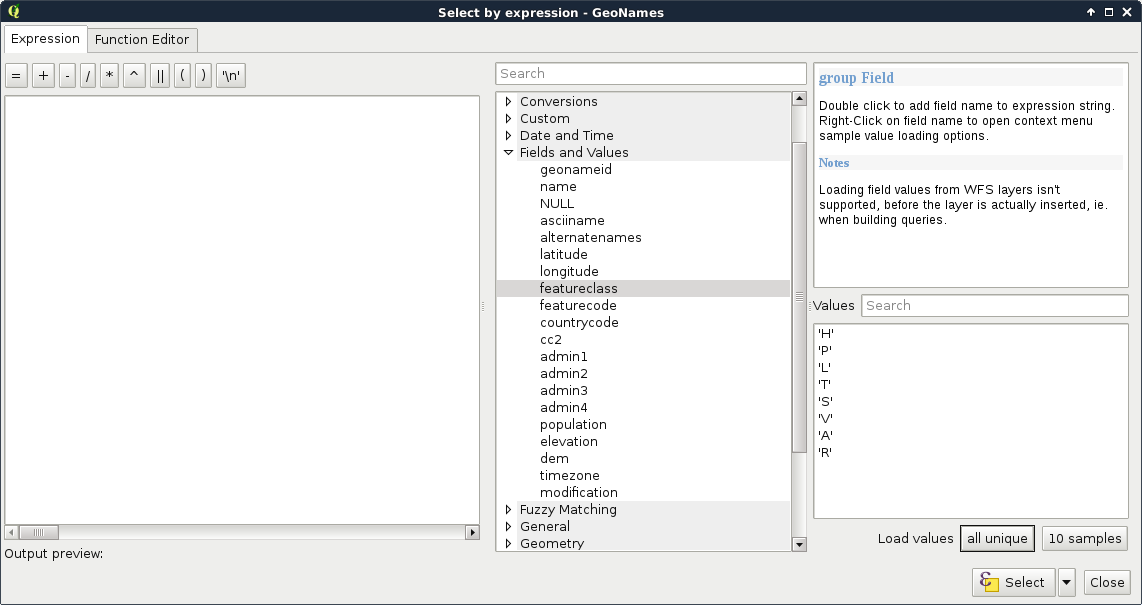

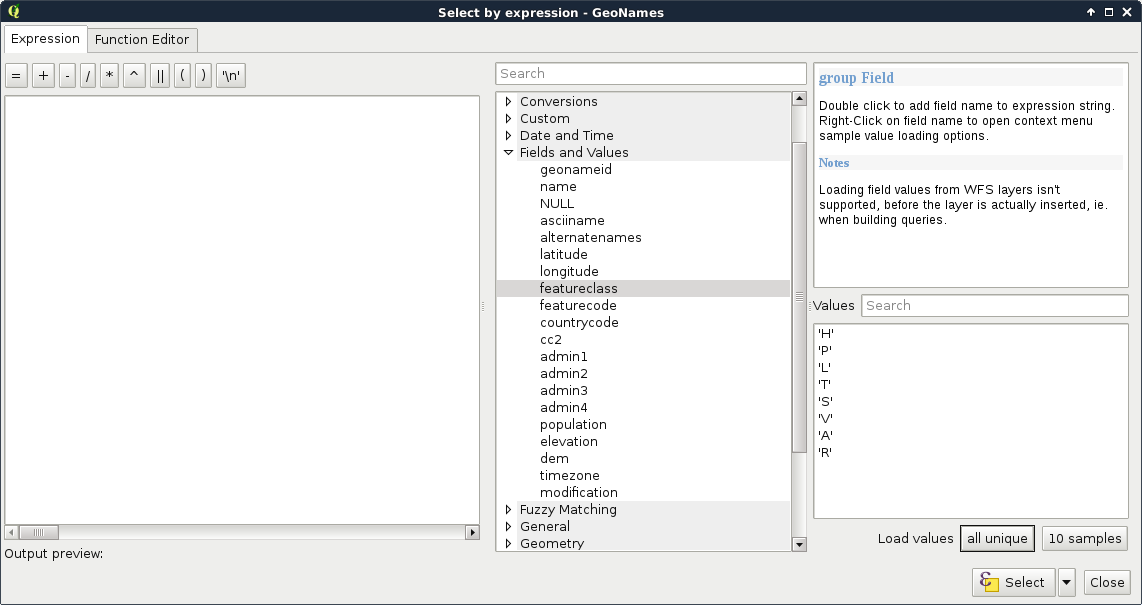

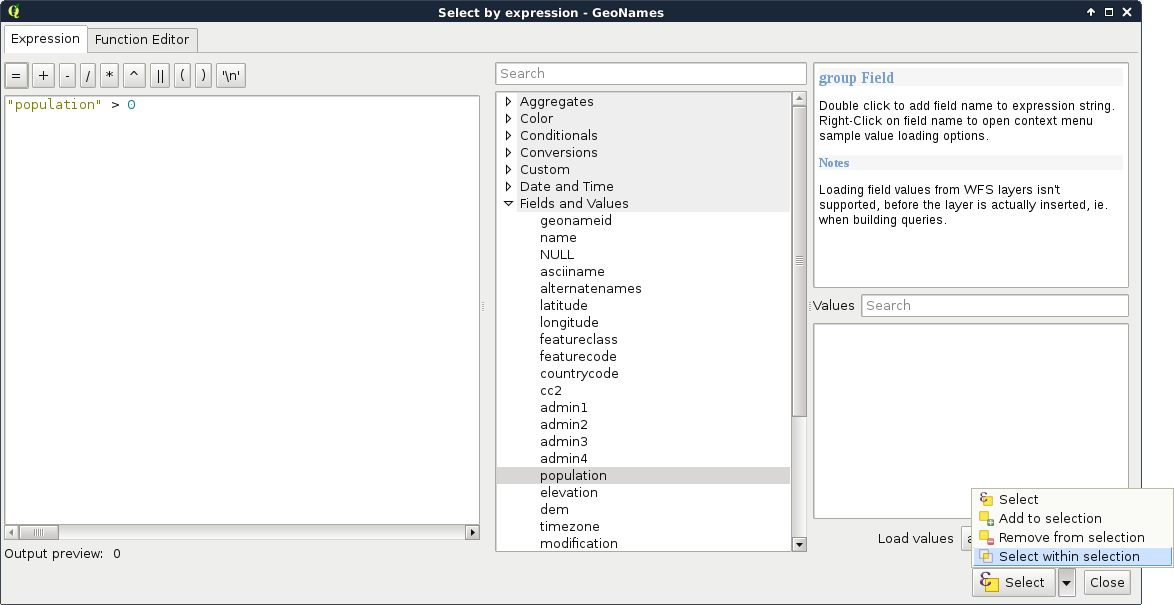

Let's select the modified GeoNames layer and open the Select features using an expression tool. We can see QGIS's expression builder, which offers a very convenient GUI with a lot of functions in the middle panel, and a small and handy description for the selected function in the left panel. We do not even have to type anything to use some of the basic queries as QGIS lists every field we can access under the Fields and Values menu. Furthermore, QGIS can also list all the unique values or just a small sample from a column by selecting it and pressing the appropriate button in the left panel:

The basic SQL expressions that we can use are listed under the Operators menu. There, every operator is a valid PostgreSQL operator, most of them are commonly found in various GIS software. Let's start with some numeric comparisons. For that, we have to choose a numeric column. We can use the attribute table for that.

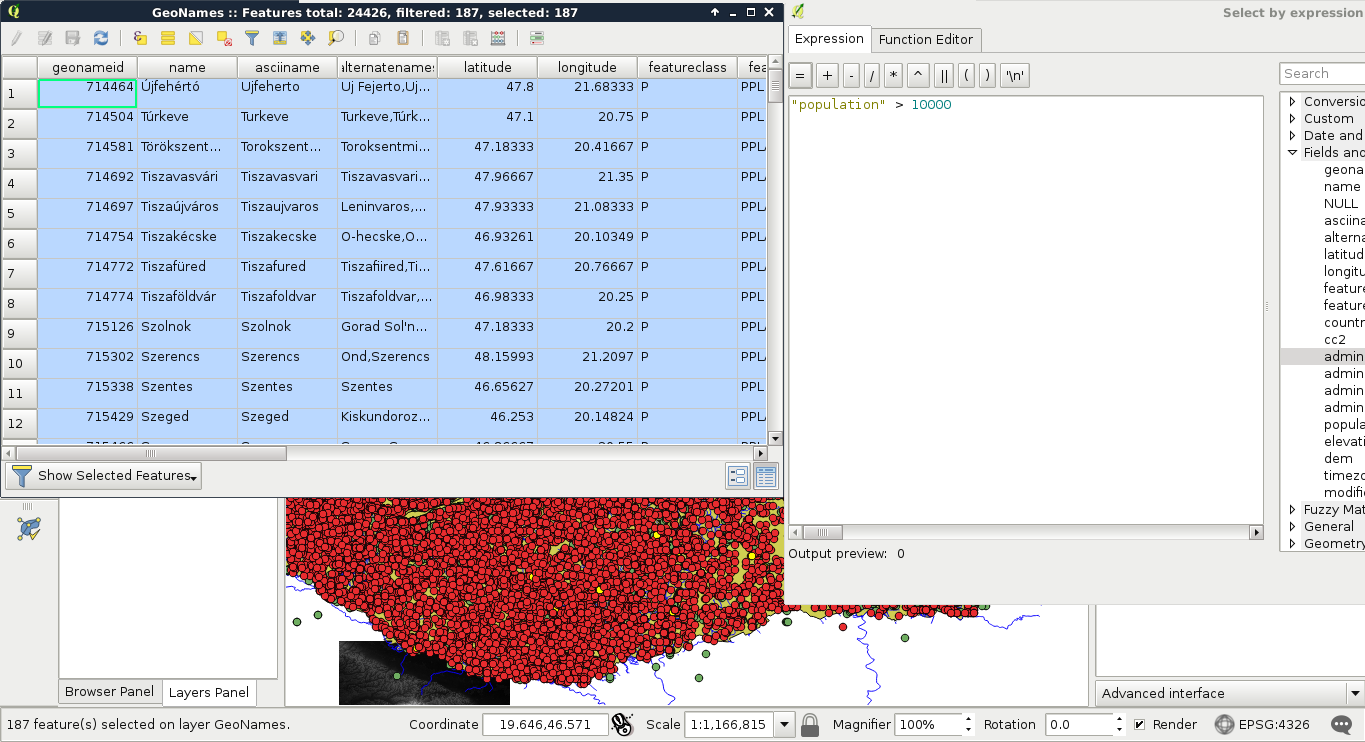

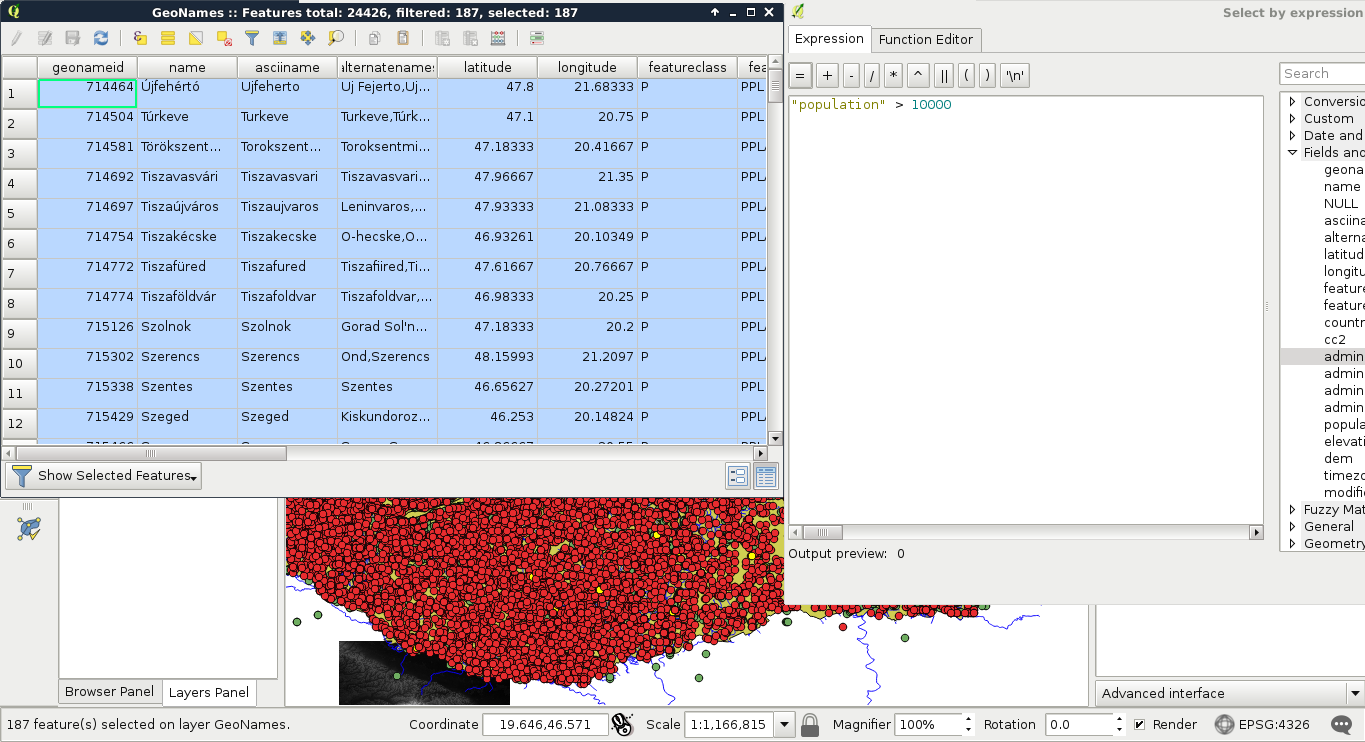

For basic numeric comparisons, let's choose the population column. In this first query, we would like to select every place where the population exceeds 10000 people. To get the result, we have to supply the following query:

"population" > 10000

We can now see the resulting features as on the following screenshot:

If we would like to invert the query, we have an easy task, which is as follows:

"population" <= 10000

We could do this as population is a graduated value. It changes from place to place. But what happens when we work with categories represented as numbers? In this next query, we select every place belonging to the same administrative area. Let's choose an existing number in the admin1 column, and select them:

"admin1" = 10

The corresponding features are now selected on the map canvas:

The canvas in the preceding screenshot looks beautiful! But how can we invert this query? If you know about programming, then you must be thinking about linking two queries logically together. It would be a correct solution; however, we can use a specific operator for these kinds of tasks, which is as follows:

"admin1" <> 10

The <> operator selects everything which is not equal to the supplied value. The next attribute type that we should be able to handle is string. With strings, we usually use two kinds of operations--equality checking and pattern matching. According to the GeoNames readme, the featurecode column contains type categories in the character format. Let's choose every point representing the first administrative division (ADM1), as follows:

"featurecode" = 'ADM1'

Of course, the inverse of this query is exactly the same like in the previous query (<> operator).

As the next task, we would like to select every feature which represents some kind of administrative division. We don't know how many divisions are there in our layer and we wouldn't like to find out manually. What we know from http://www.geonames.org/export/codes.html is that every feature representing a non-historic administrative boundary is coded with ADM followed by a number. In our case, pattern matching comes to the rescue. We can formulate the query as follows:

"featurecode" LIKE 'ADM_'

In pattern matching, we use the LIKE operator instead of checking for equality, telling the query processor that we supplied a pattern as a value. In the pattern, we used the wildcard _, which represents exactly one character. Inverting this query is also irregular as we can negate LIKE with the NOT operator, as follows:

"featurecode" NOT LIKE 'ADM_'

Now let's expand this query to historical divisions. As we can see among the GeoNames codes, we could use two underscores. However, there is an even shorter solution--the % wildcard. It represents any number of characters. That is, it returns true for zero, one, two, or two billion characters if they fit into the pattern:

"featurecode" LIKE 'ADM%'

A better example would be to search among the alternate names column. There are a lot of names for every feature in a lot of languages. In the following query, I'm searching for a city named Pécs, which is called Pecs in English:

"alternatenames" LIKE '%Pecs%'

The preceding query returns the feature representing this city along with 11 other features, as there are more places containing its name (for example, neighboring settlements). As I know it is called Fünfkirchen in German, I can narrow down the search with the AND logical operator like this:

"alternatenames" LIKE '%Pecs%' AND "alternatenames" LIKE

'%Fünfkirchen%'

The two substrings can be anywhere in the alternate names column, but only those features get selected whose record contains both of the names. With this query, only one result remains--Pécs. We can use two logical operators to interlink different queries. With the AND operator, we look for the intersection of the two queries, while with the OR operator, we look for their union. If we would like to list counties with a population higher than 500000, we can run the following query:

"featurecode" = 'ADM1' AND "population" > 500000

On the other hand, if we would like to list every county along with every place with a population higher than 500000, we have to run the following query:

"featurecode" = 'ADM1' OR "population" > 500000

The last thing we should learn is how to handle null values. Nulls are special values, which are only present in a table if there is a missing value. It is not the same as 0, or an empty string. We can check for null values with the IS operator. If we would like to select every feature with a missing admin1 value, we can run the following query:

"admin1" IS NULL

Inverting this query is similar to pattern matching; we can negate IS with the NOT operator as follows:

"admin1" IS NOT NULL

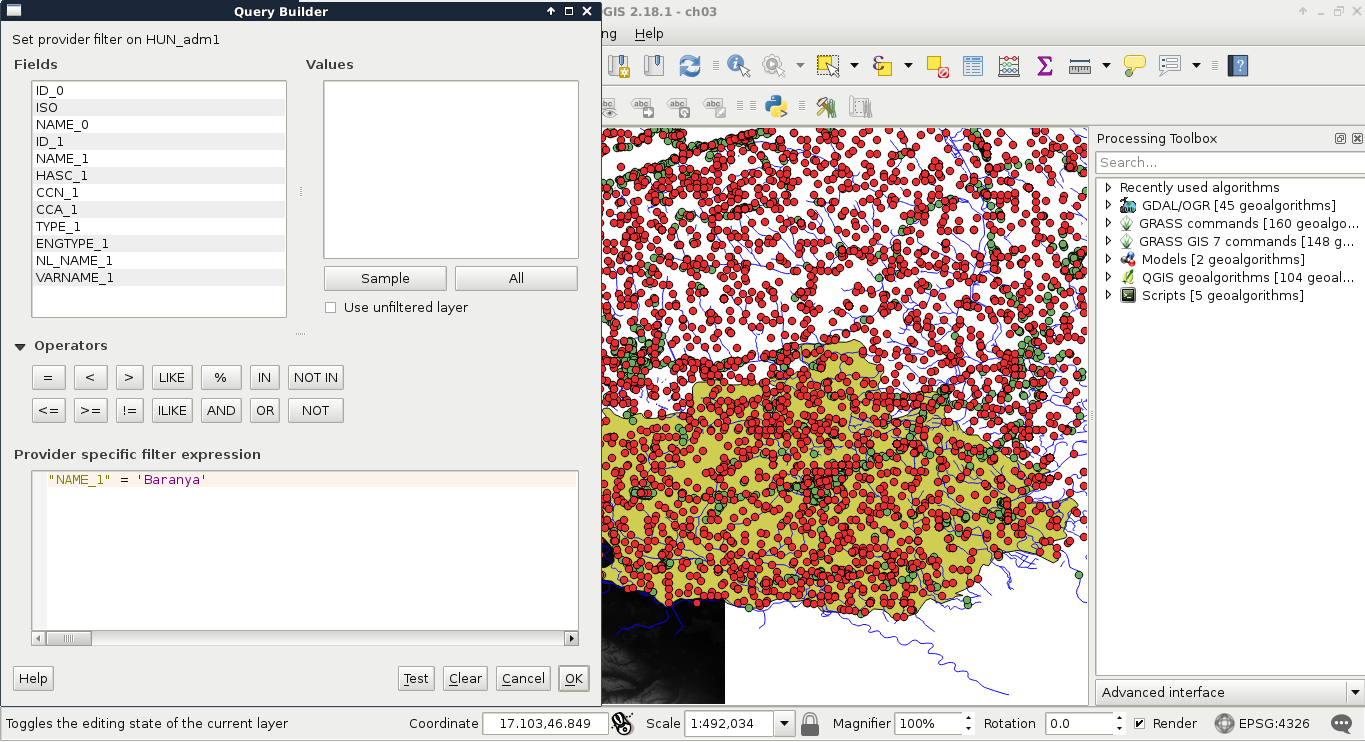

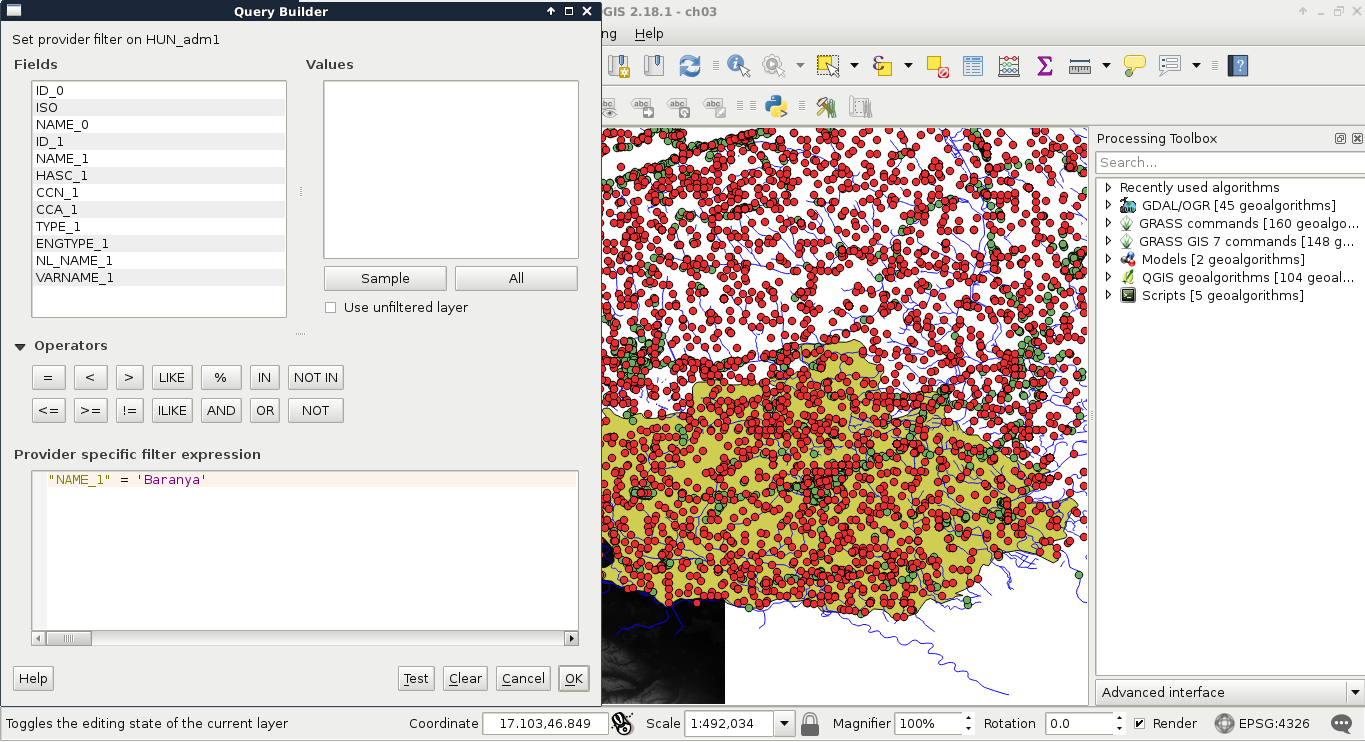

The filtering dialogue can be accessed by right-clicking on a layer in the Layers Panel and selecting Filter. As we can see in the dialogue, filtering expressions are much more restrictive in QGIS as they only allow us to write basic SQL queries with the fields of the layer. Let's inspect our study area in the administrative boundaries layer with the Identify Features tool, select a unique value like its name, and create a query selecting it. For me, the query looks like the following:

"NAME_1" = 'Baranya'

Applying the filter removes every feature from the canvas other than our study area:

Now the only feature showing up on the canvas is our study area. If we look at the layer's attribute table, we can only see that feature. Now every operation is executed only on that feature. What we cannot accomplish with filtering is increasing the performance of subsequent queries and analyses. Rendering performance might be increased, but, for example, opening the attribute table requires QGIS to iterate through every feature and fill the table only with the filtered ones.

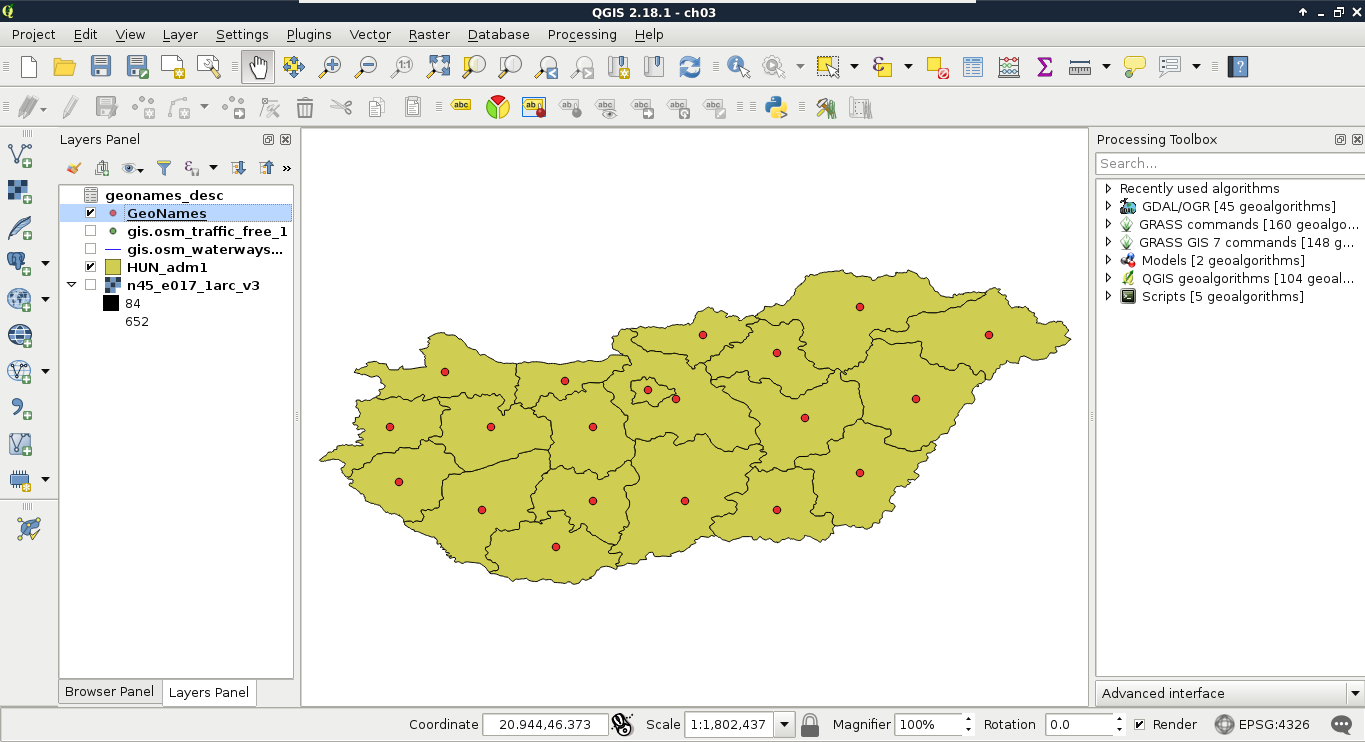

Let's practice filtering a little more by creating a filter for the GeoNames layer, selecting only points which represent first-level administrative boundaries. To do this, we have to supply the following query:

"featurecode" = 'ADM1'

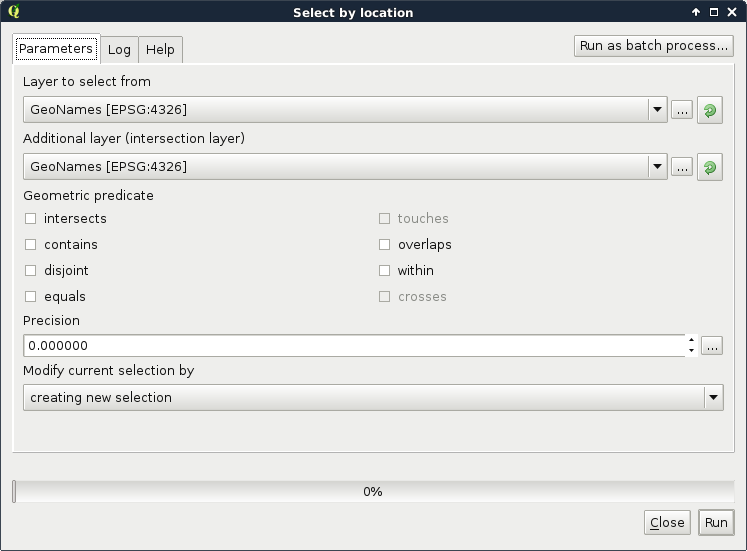

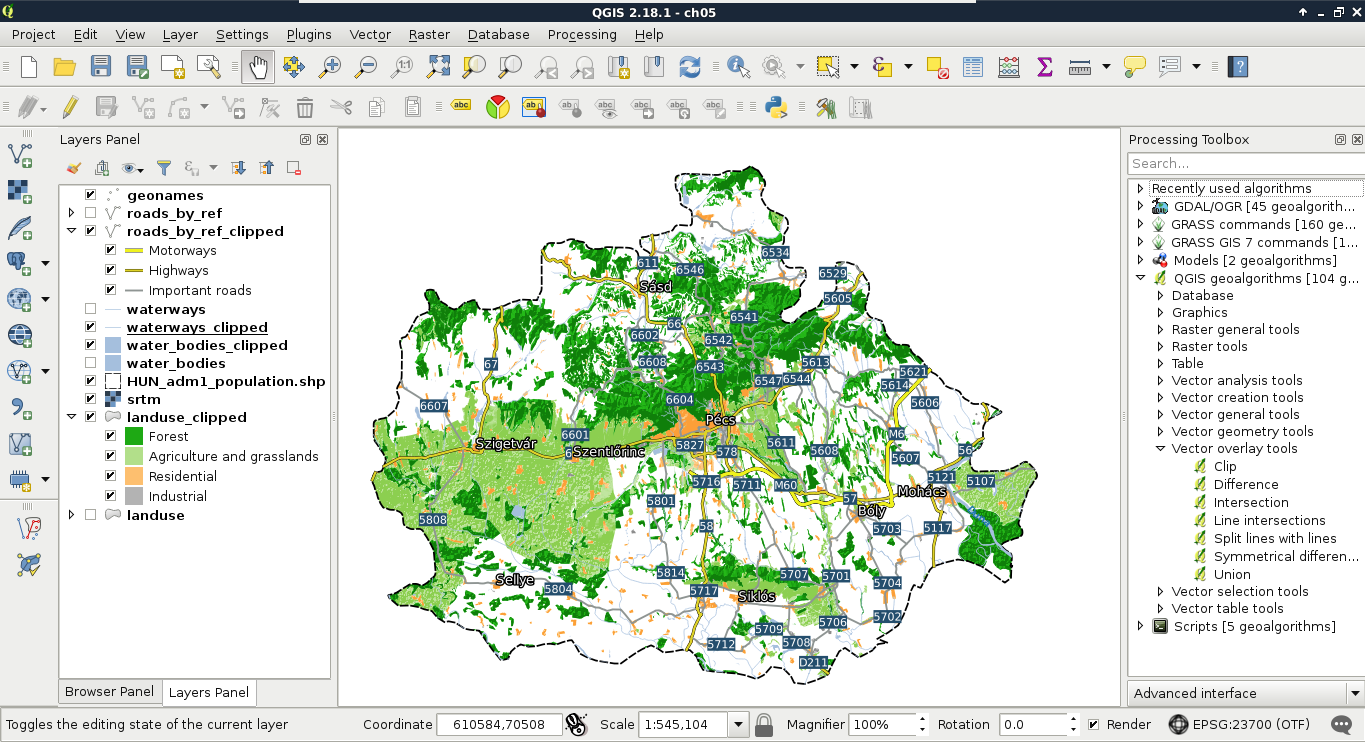

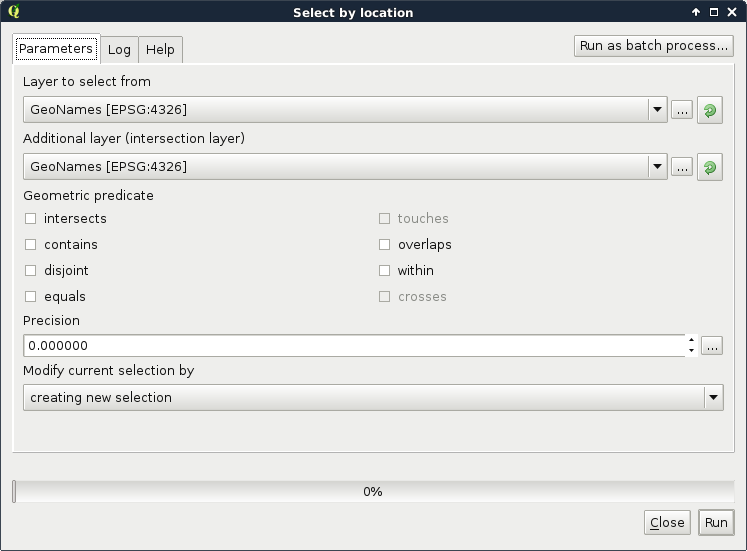

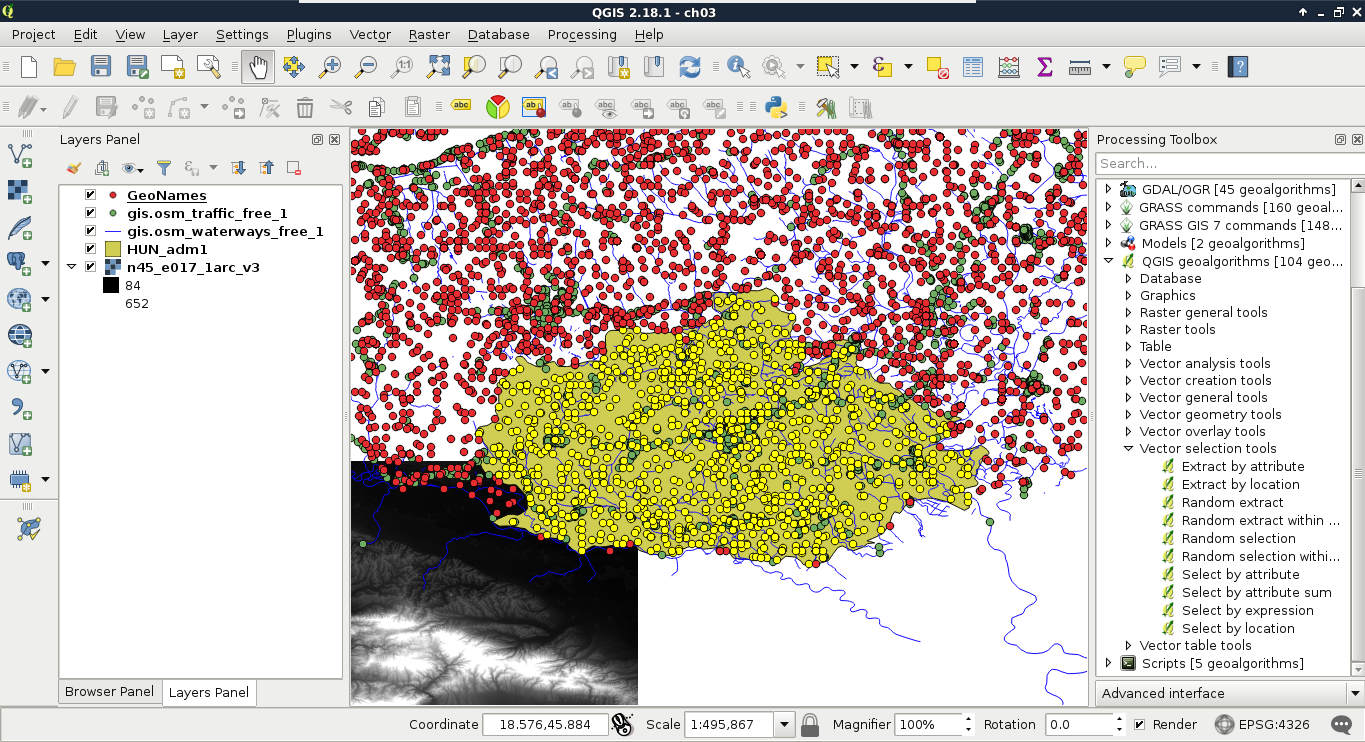

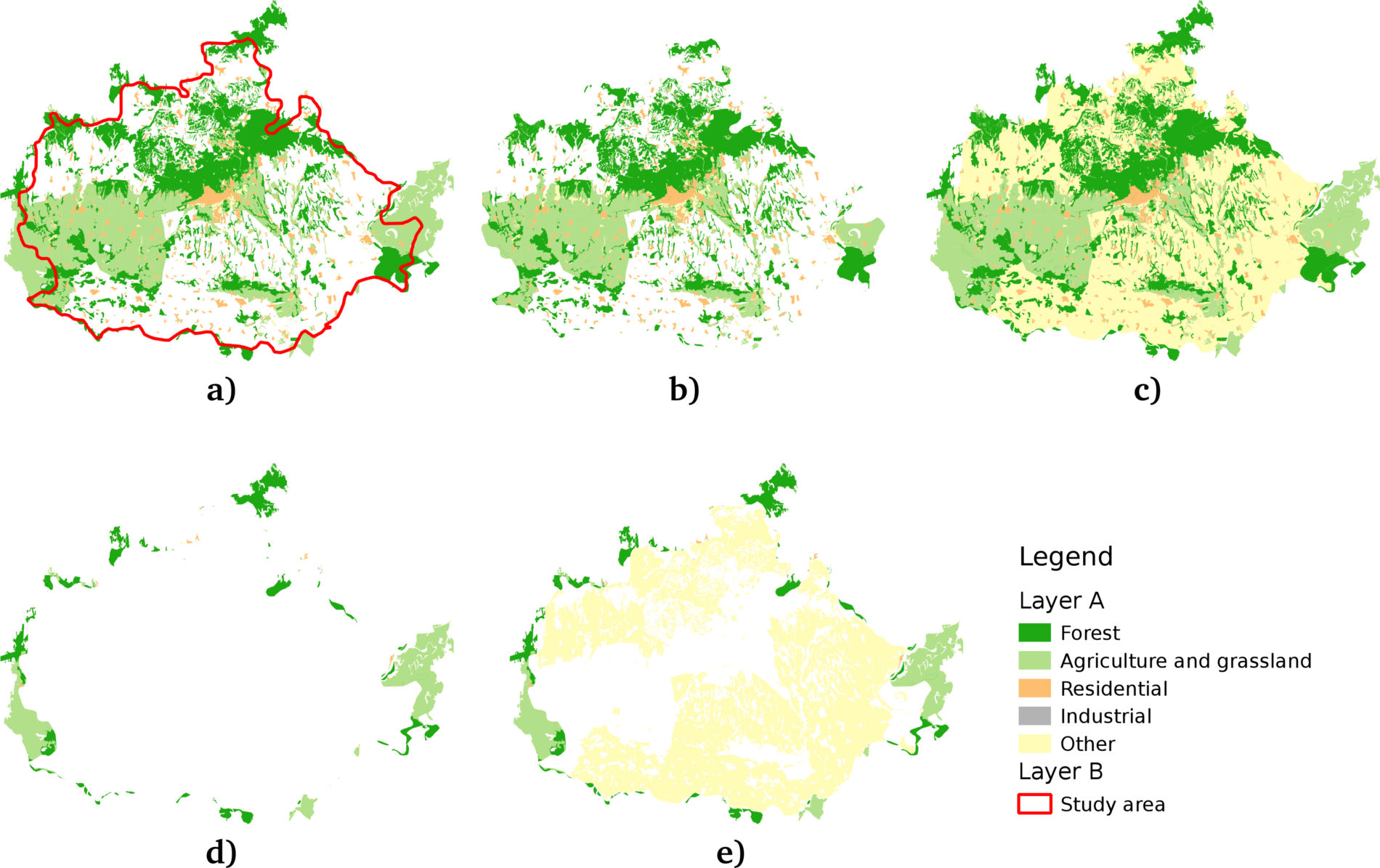

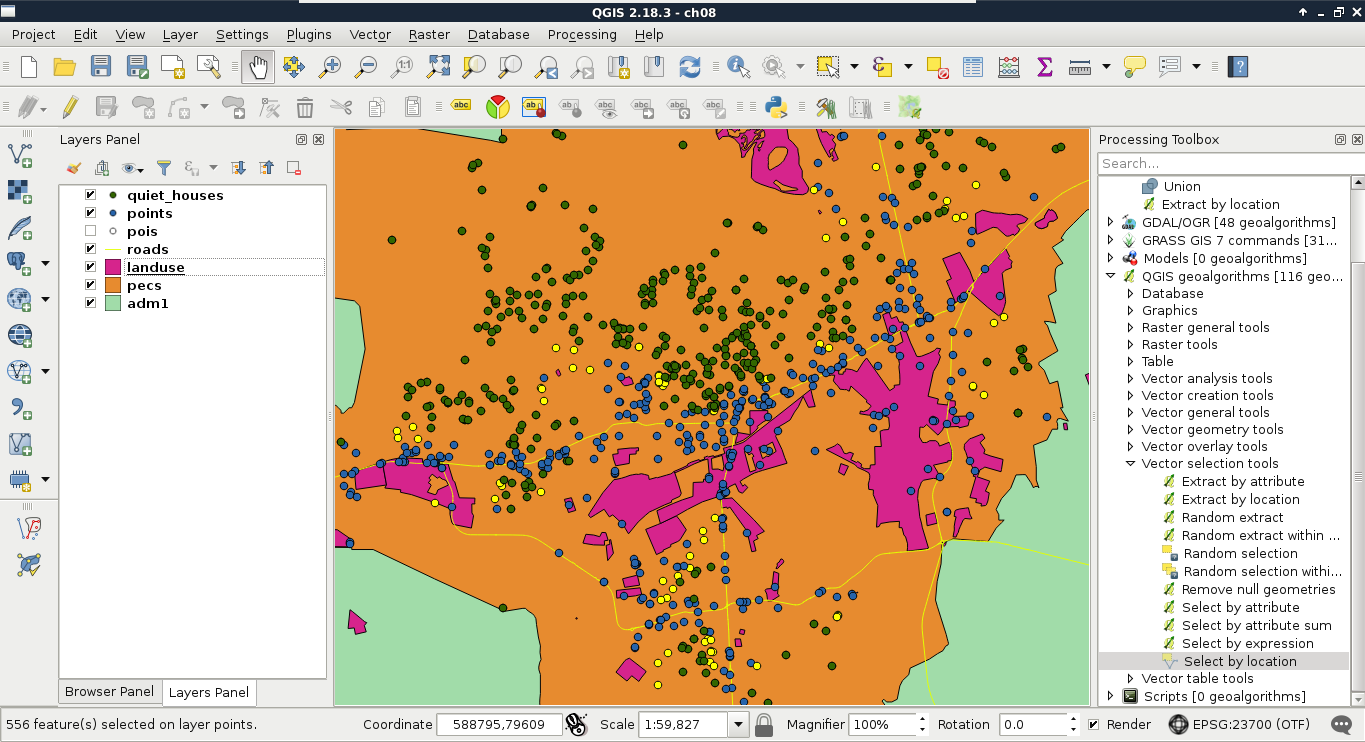

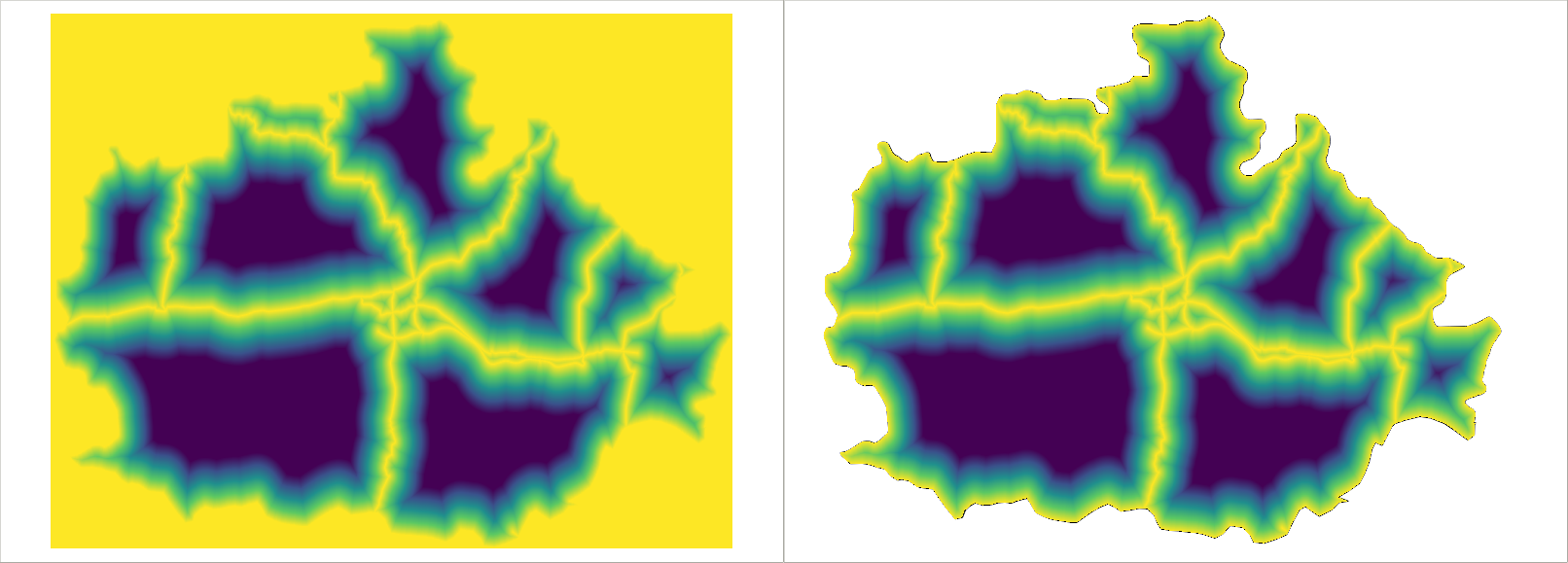

We can not only select features by their attributes, but also by their spatial relationships. These queries are called spatial queries, or selecting features by their location. With this type of querying, we can select features intersecting or touching other features in other layers. The most convenient mode of spatial querying allows us to consider two layers at a time, and select features from one layer with respect to the locations of features in the other one. First of all, let's remove the filter from our GeoNames layer. Next, to access the spatial query tool in QGIS, we have to browse our Processing Toolbox. From QGIS geoalgorithms, we have to access Vector selection tools and open the Select by location tool:

As we can see, QGIS offers us a lot of spatial predicates (relationship types) to choose from. Some of them are disabled as they do not make any sense in the current context (between two point layers). If we select other layers, we can see the disabled predicates changing. Let's discuss shortly what some of these predicates mean. In the following examples, we have a layer A from which we want to select features, and a layer B containing features we would like to compare our layer A to:

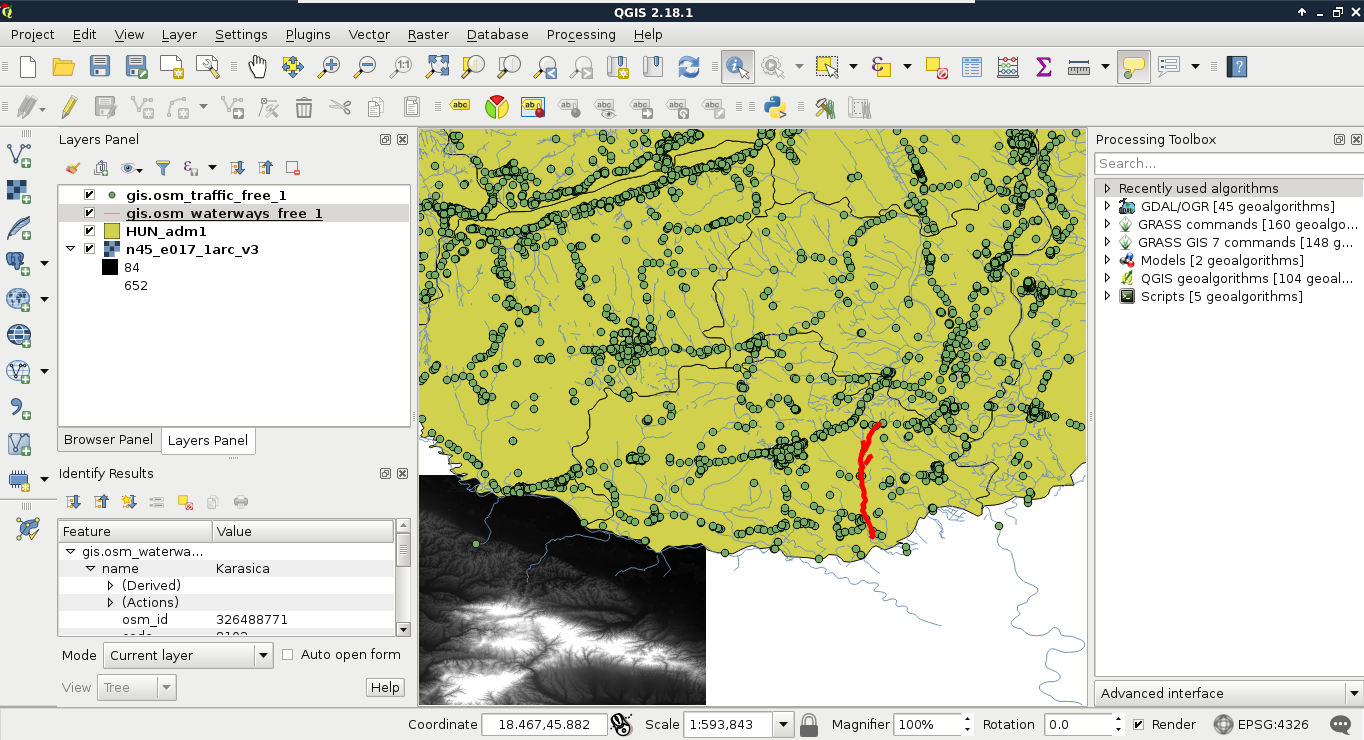

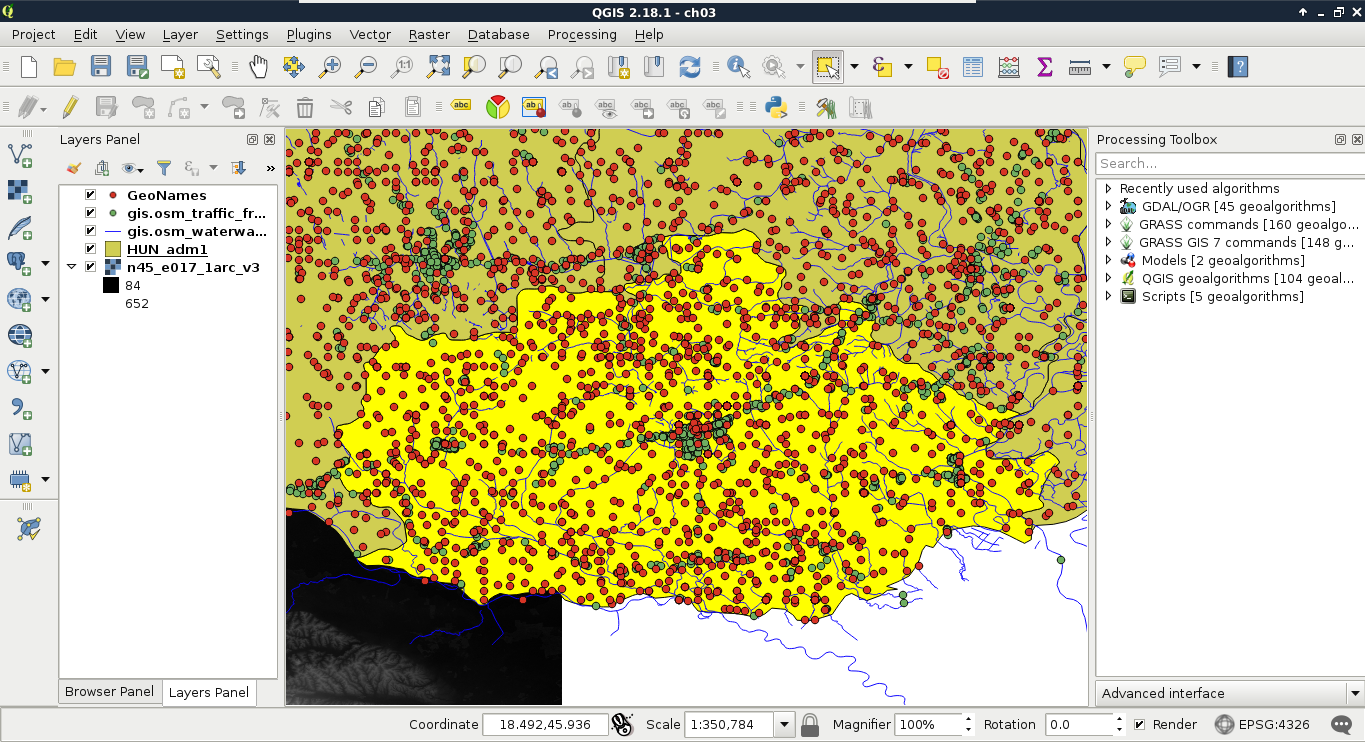

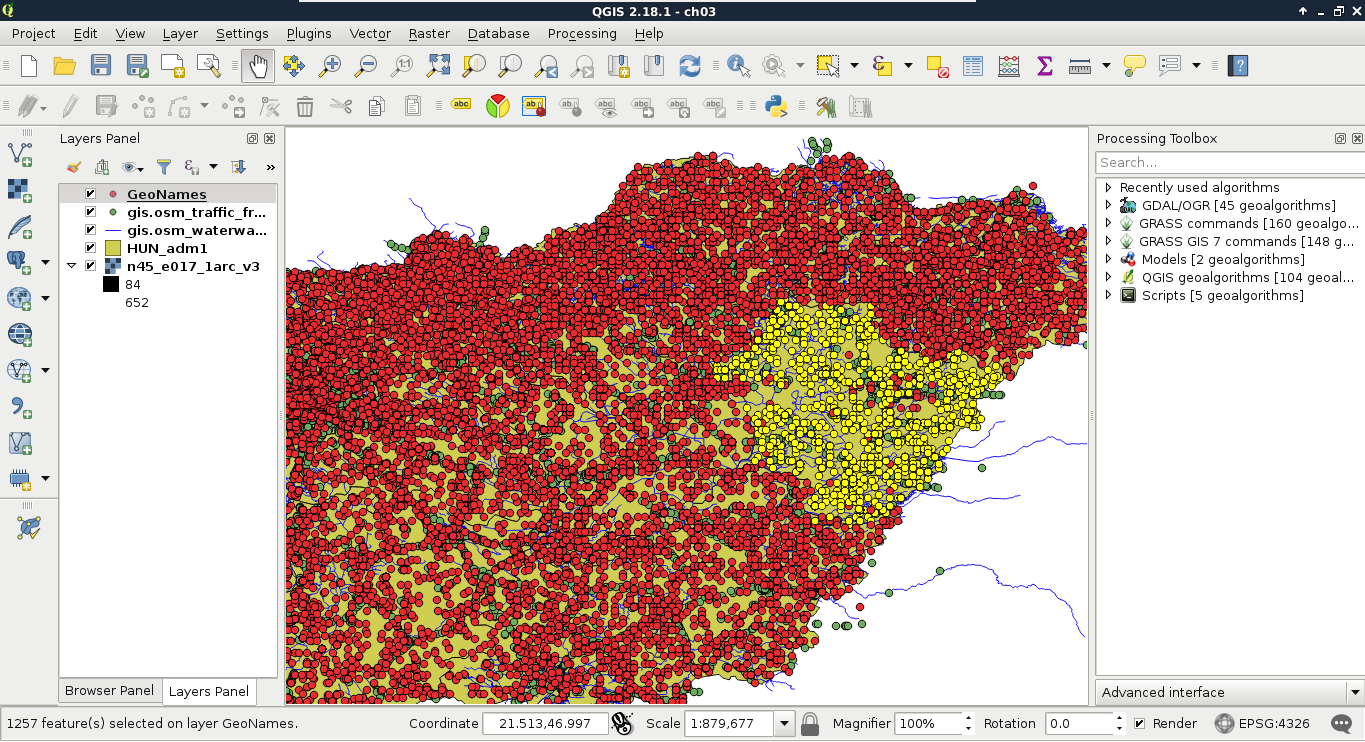

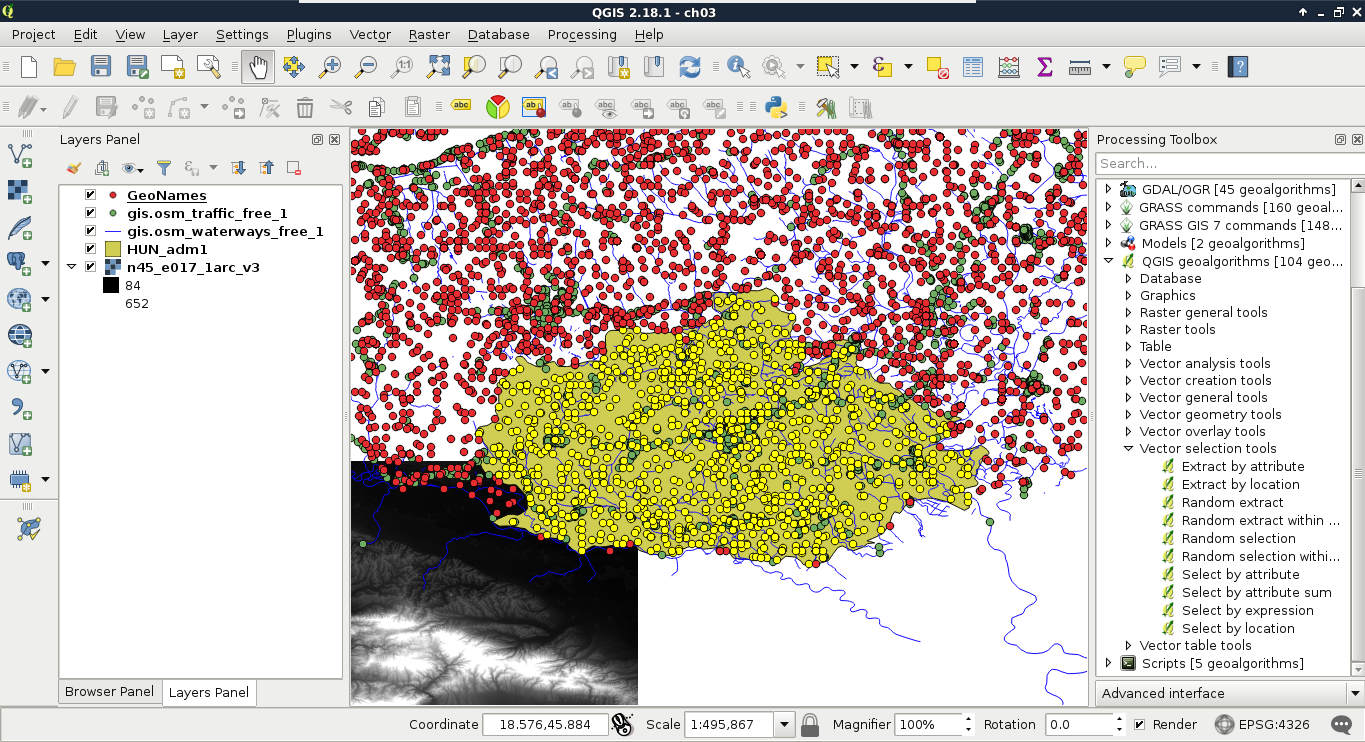

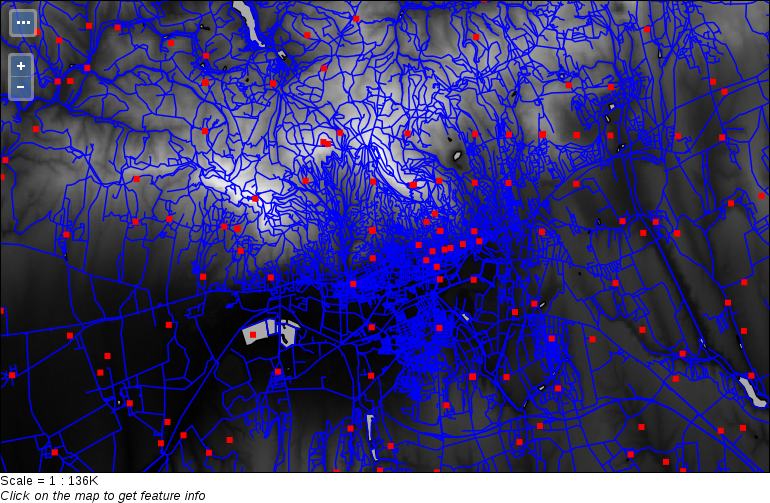

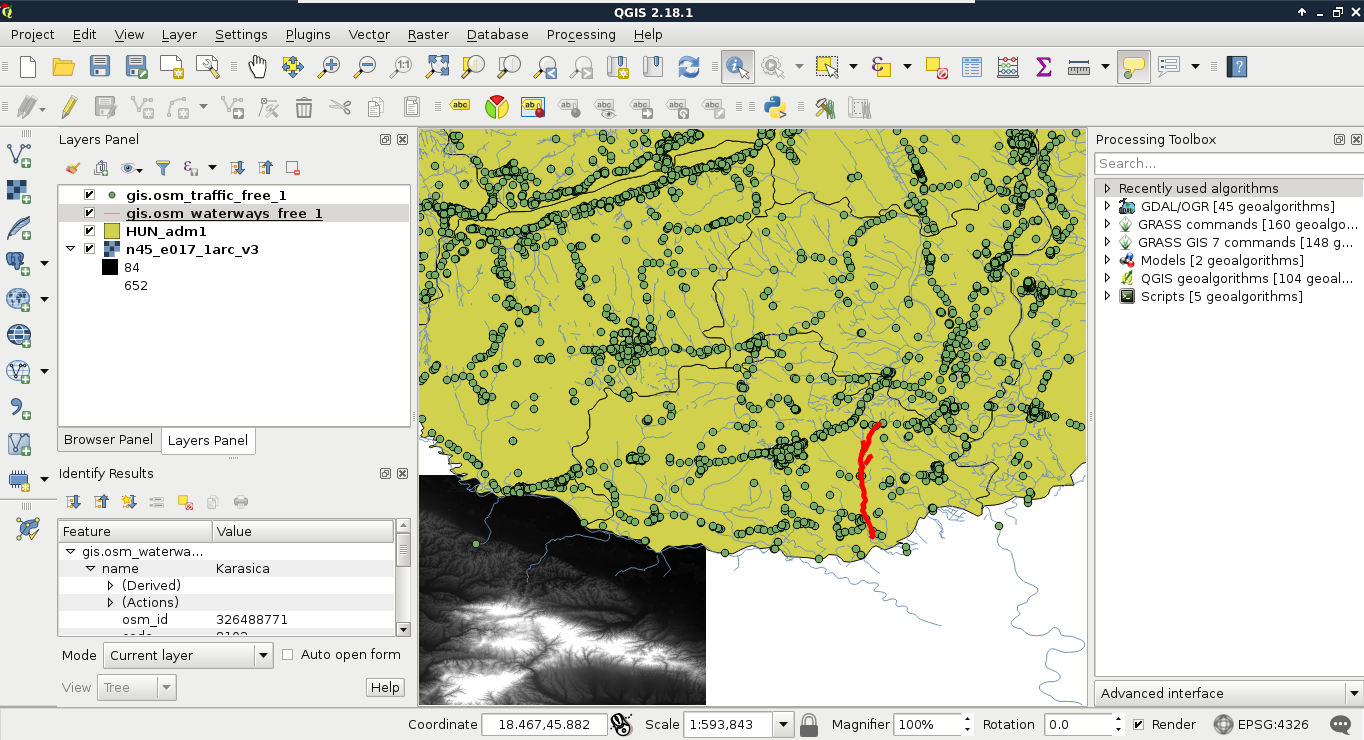

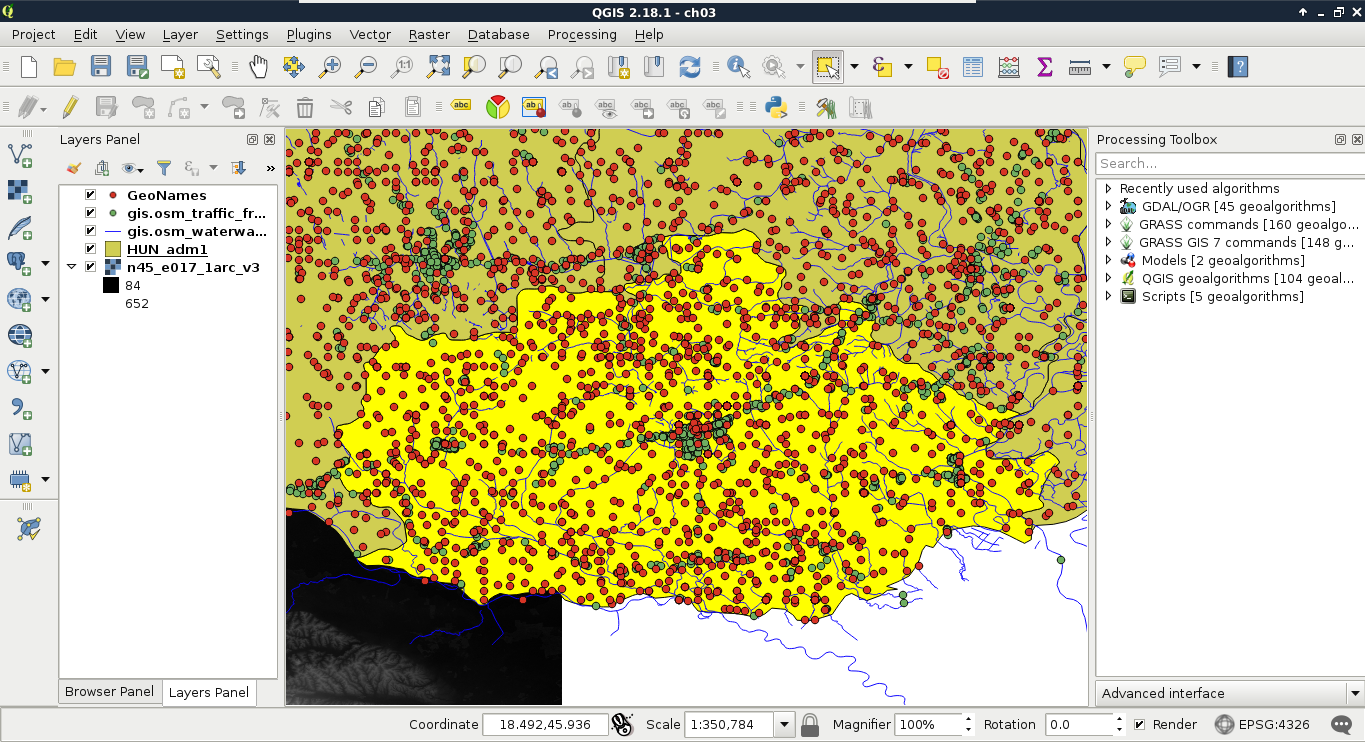

Let's select every feature from the GeoNames layer in our study area. As we have our study area filtered, we can safely pass the administrative layer as the Additional layer parameter. The only thing left to consider is the spatial predicate. Which one should we choose? You must be thinking about intersects or within. In our case, there is a fat chance that both of them yield to the same result. However, the correct one is intersects, as within does not consider points on the boundary of the polygon. After running the algorithm, we should see every point selected in our study area. Consider the following screenshot:

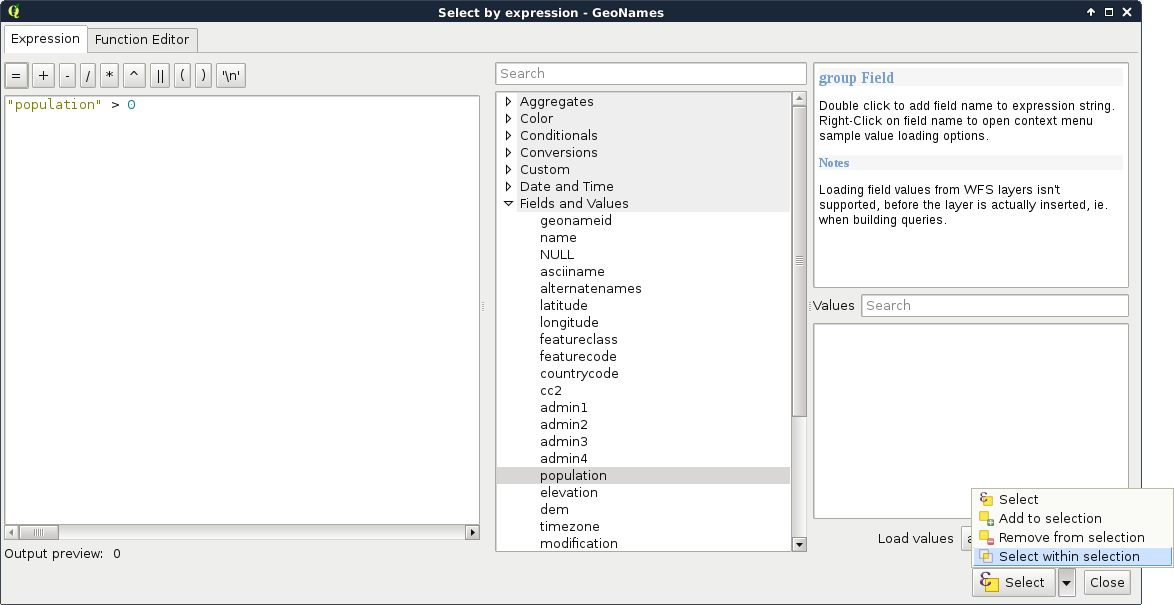

Lovely! The only problem, which I forgot to mention, is that we are only interested in features with a population value. The naive way to resolve this issue is to remove the selection, apply a filter on the GeoNames layer, and run the Select by location algorithm again. We can do better than that. If we open the query builder dialog, we can see some additional options next to Select by clicking on the arrow icon. We can add to the current selection, remove from it, and even select within the selection. For me, that is the most intuitive solution for this case. We just have to come up with a basic query and click on Select within selection:

"population" > 0

We discussed earlier that basic SQL expressions in GIS allow us to select features in only one layer. However, QGIS offers us numerous advanced options for querying even between layers. Unlike filtering, the query dialog allows us to use this extended functionality. These operations are functions which require some arguments as input and return values as output. As we can deal with many kinds of return values, let's discuss how queries work in QGIS.

First, we build an expression. QGIS runs the expression on every feature in the queried layer. If the expression returns true for the given feature, it becomes selected or processed. We can test this behavior by opening the query dialog and simply typing TRUE. Every feature gets selected in the layer as when this static value is evaluated, it yields to true for every feature. Following this analogy, if we type FALSE, none of the features get selected. What happens when we get a non-Boolean type as a return value? Well, it depends. If we get 0 or an empty string for a feature, it gets excluded, while if it is evaluated to another number, or a string, it gets selected. If we get an object as a result, that too counts as false.

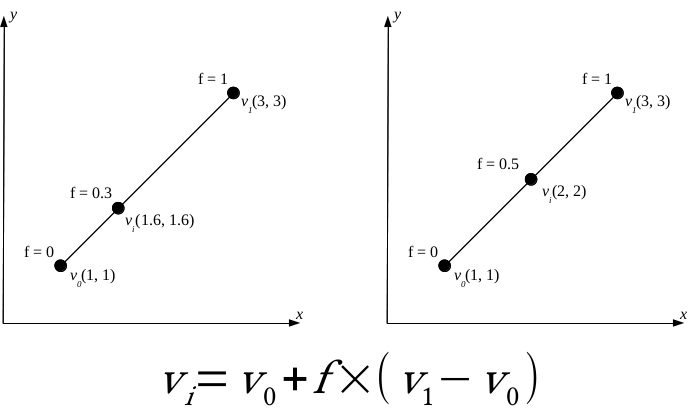

If we use the advanced functionality of the query builder, we get access to numerous variables besides functions. Some of these variables, starting with $, represent something from the current feature. For example, $geometry represents the geometry of the processed feature, while $area represents the area of the geometry. Others, starting with @, store global values. Under the Variables menu, we can find a lot of these variables. Although they do not show the @ character in the middle panel, they will if we double click on them.

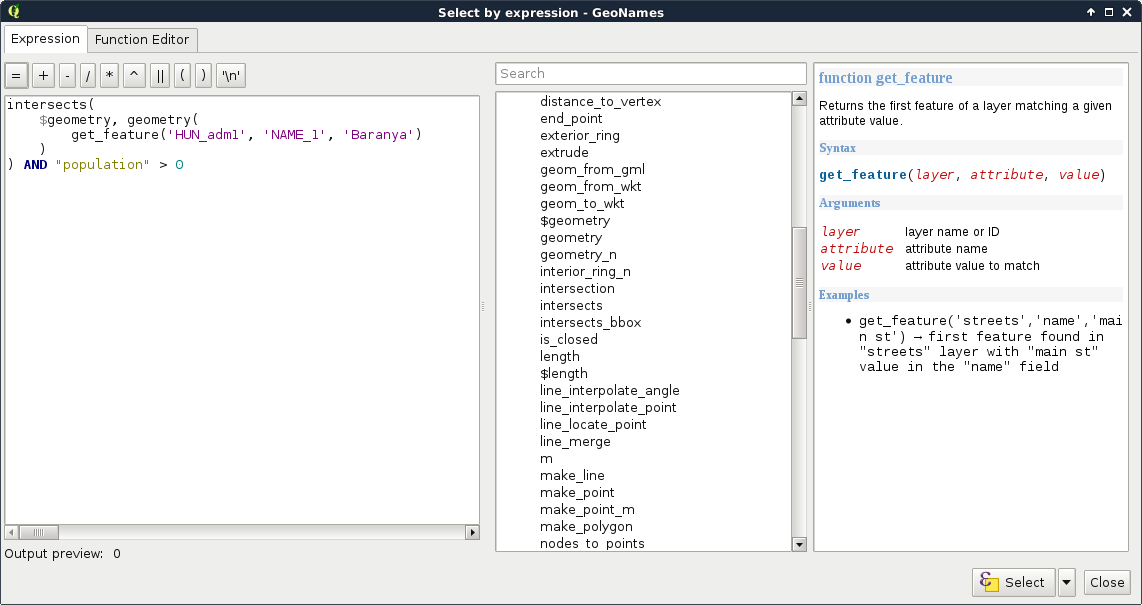

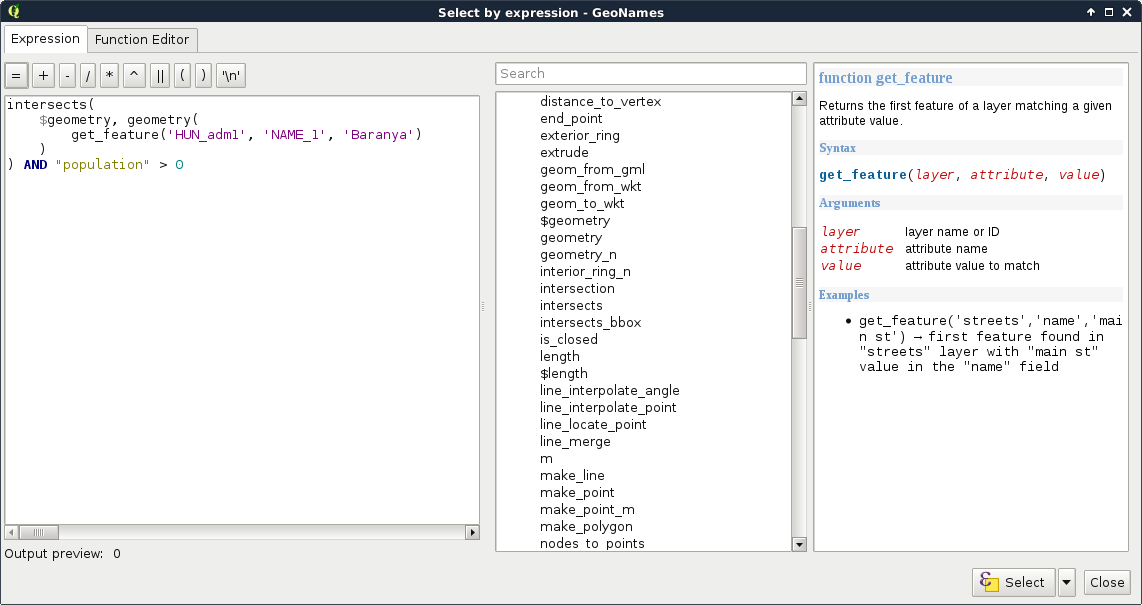

Let's create a query which does the same as our last one. We have to select every feature in our study area from the GeoNames layer which has a population value higher than 0. Under the Geometry menu in the middle panel, we can access a lot of spatial functions. The one we need in our case is intersects. We can see in the help panel that it requires two geometries and it returns true if the two geometries intersect. Accessing the geometries of the point features is easy as we have a variable for that. So far, our query looks like this:

intersects($geometry, )

Here comes the tricky part. We have to access a single constant geometry from another layer. If we browse through the available functions, we can almost instantly bump into the geometry function, which returns a geometry of a feature:

intersects($geometry, geometry( ))

As geometry can only process features, the last step is to extract the correct feature from the administrative boundaries layer. Under the Record menu, we can see the most convenient function for this task--get_feature. The function requires three arguments--the name or ID of a layer, the attribute column, and an attribute value. It's just a basic query in a functional form. After passing the required arguments, our query looks similar to the following:

intersects($geometry, geometry(get_feature('HUN_adm1', 'NAME_1',

'Baranya')))

Now we have a constant geometry, the geometries of the point features one by one, and a function checking for their intersections. The only thing left to supply is the population part. We can easily join that criterion with a logical operator as follows:

intersects($geometry, geometry(get_feature(

'HUN_adm1', 'NAME_1', 'Baranya'))) AND "population" > 0

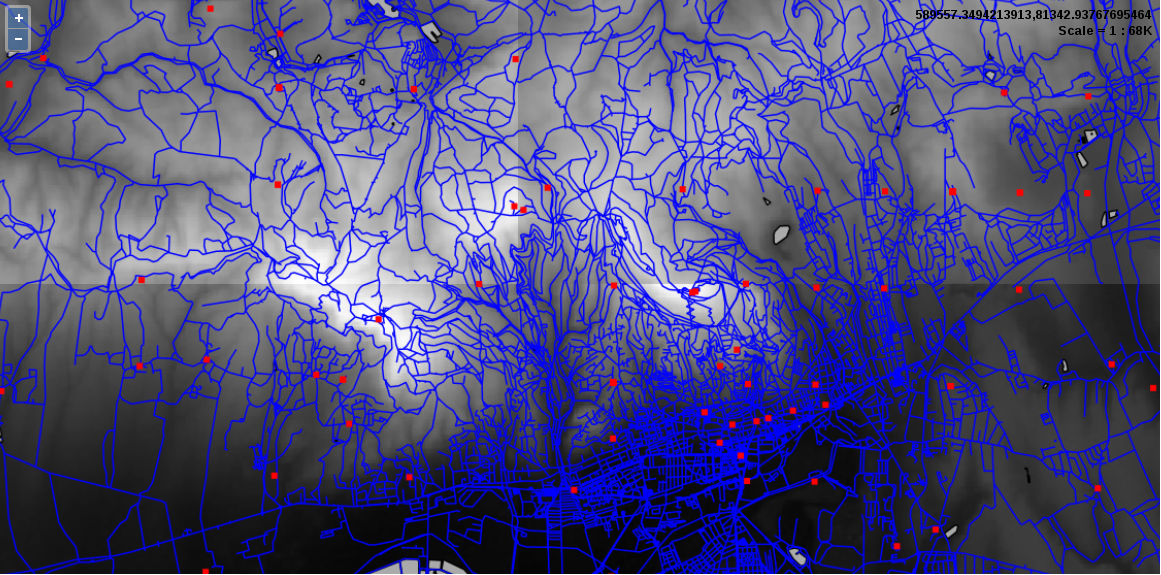

For a visual example of the query, consider the following screenshot:

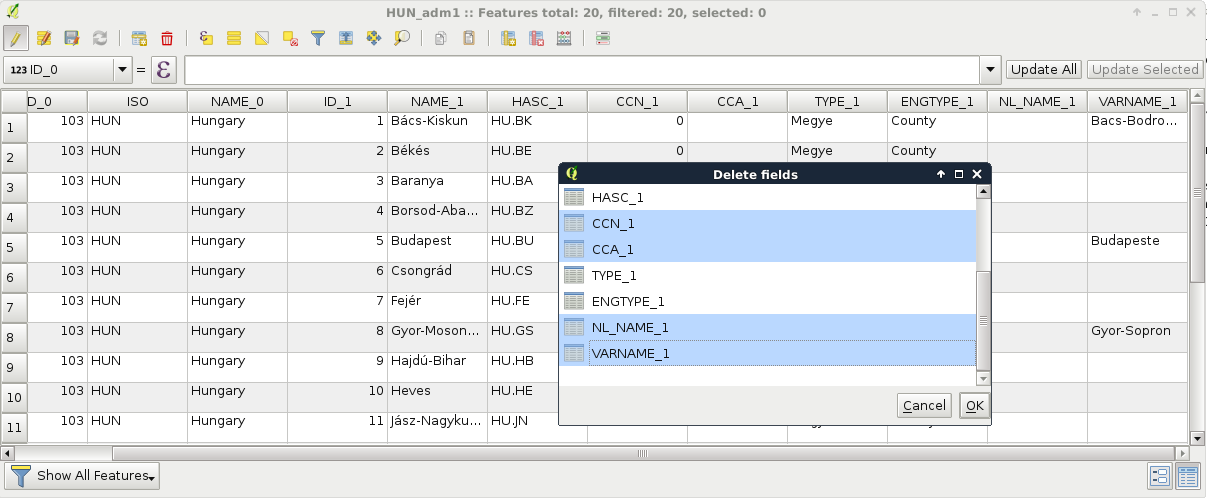

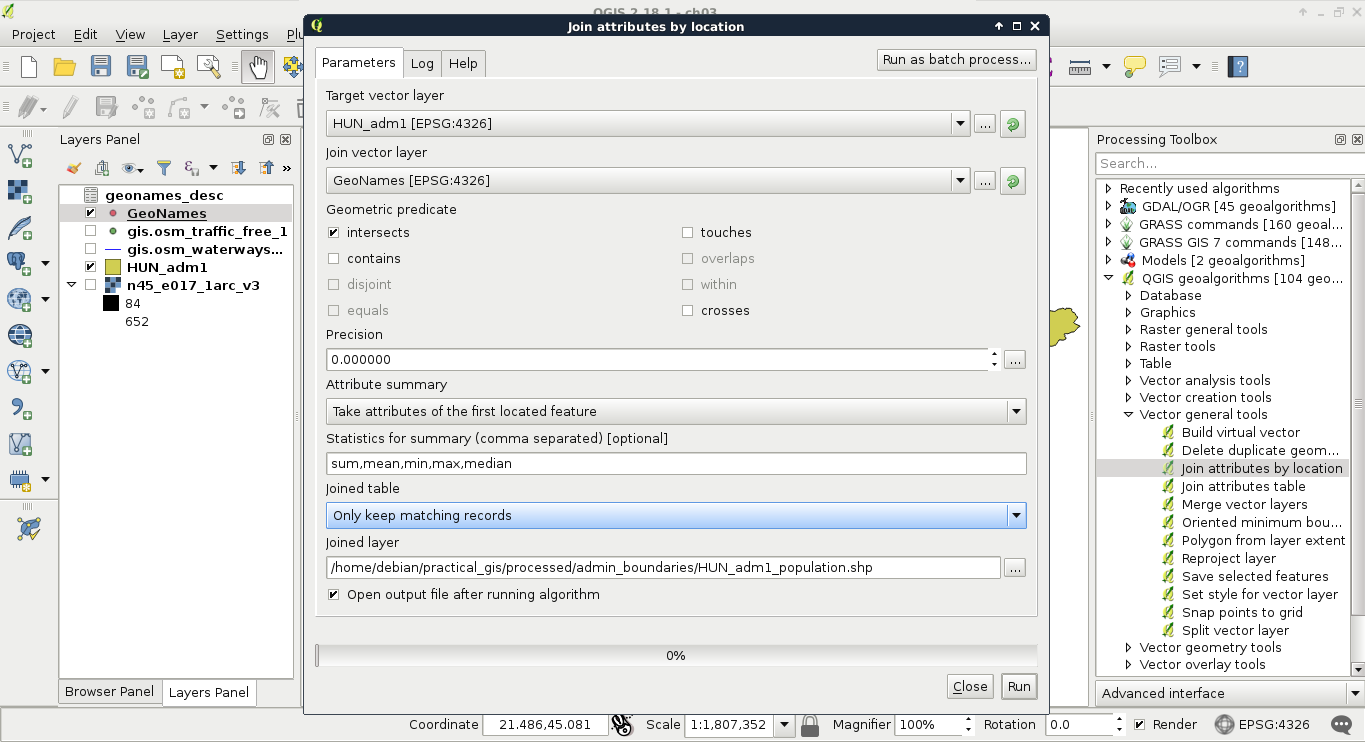

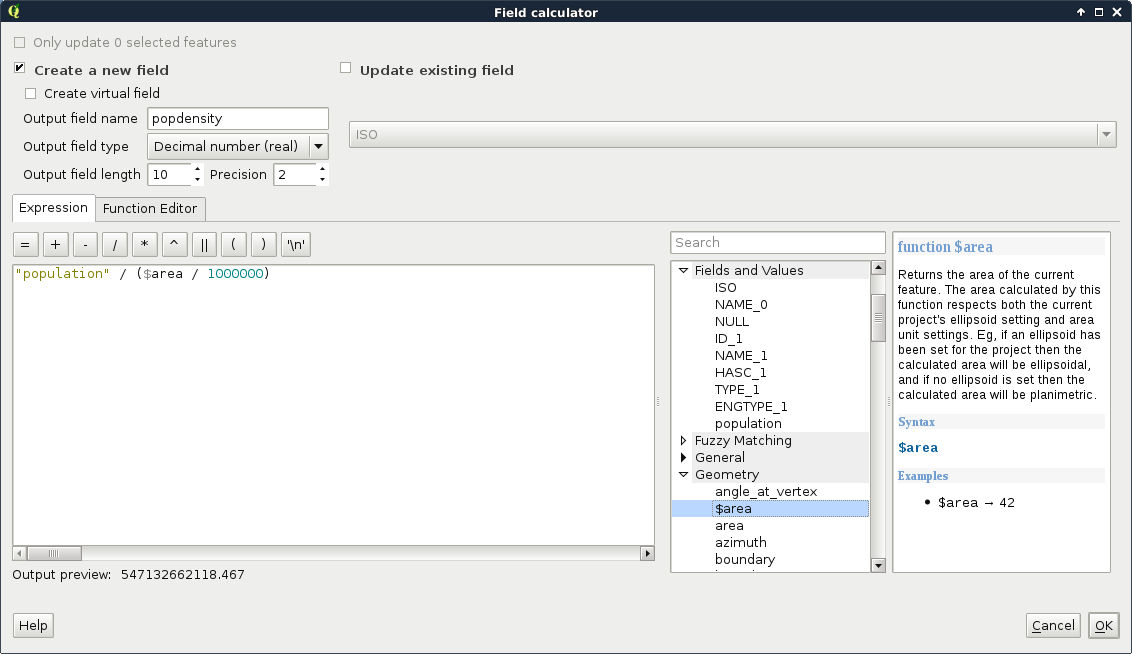

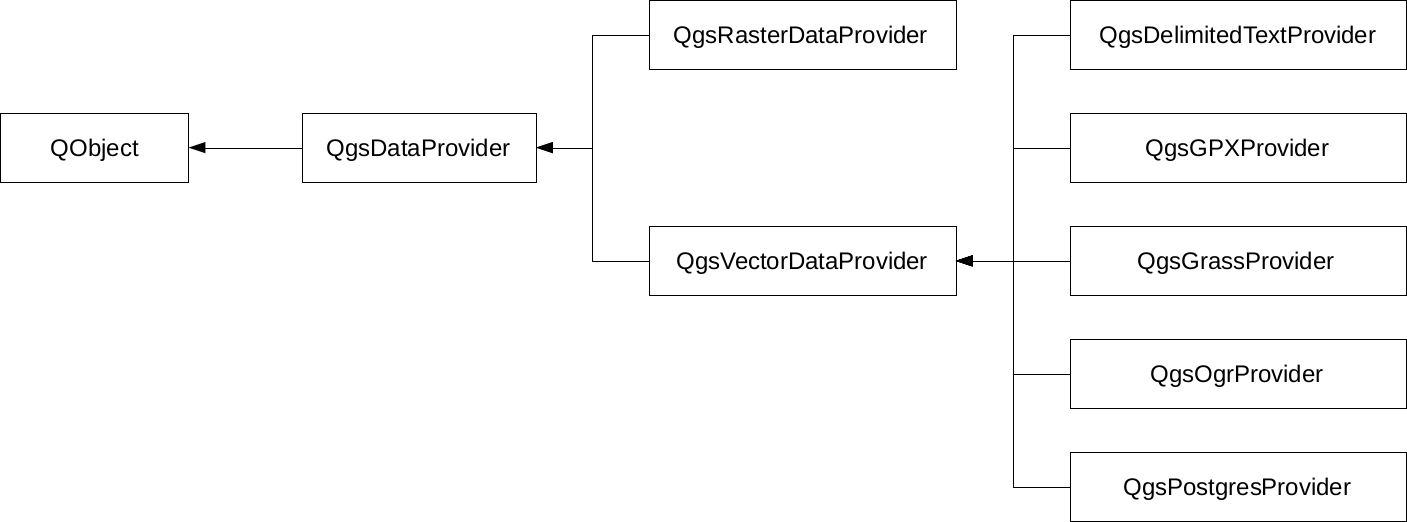

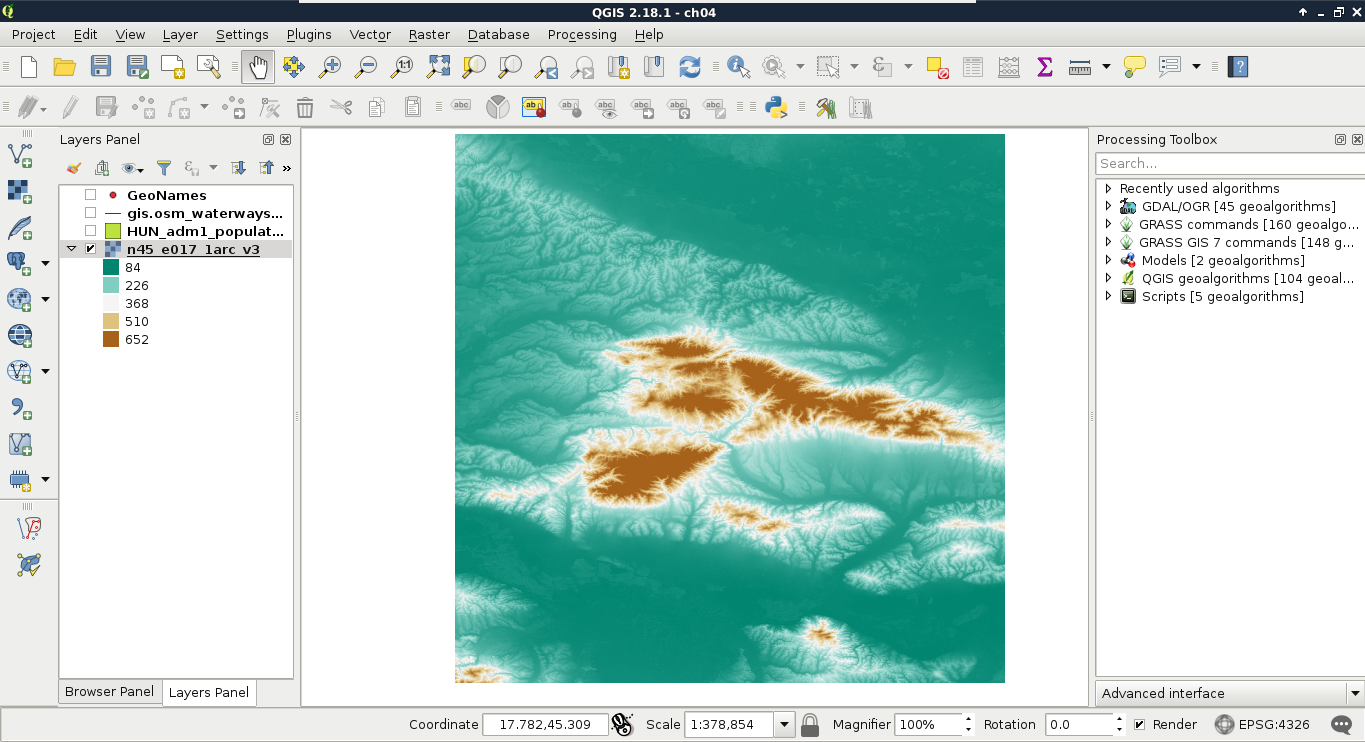

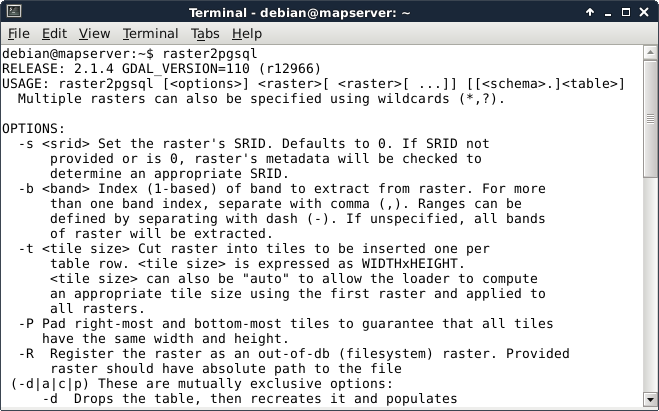

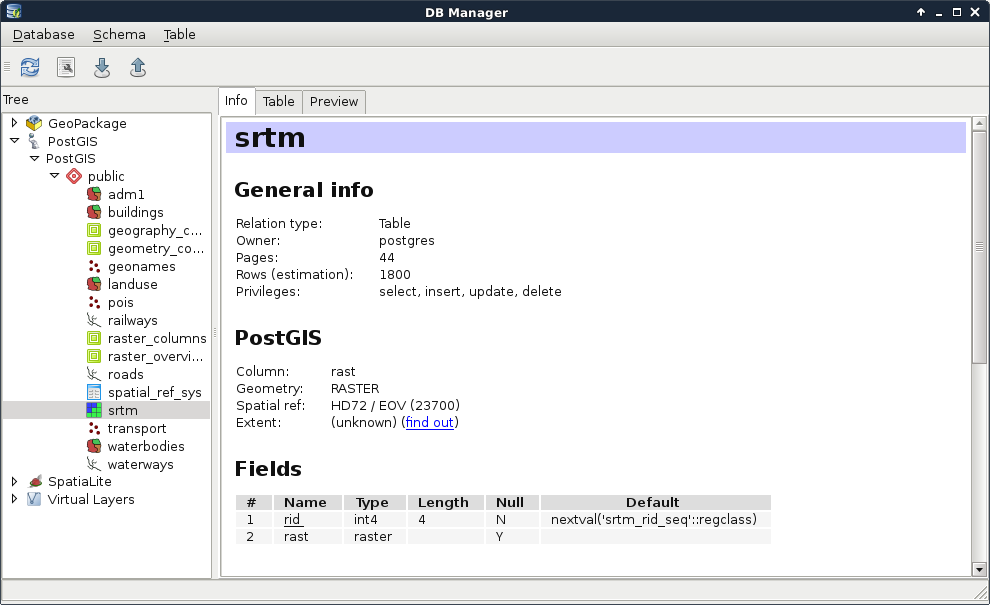

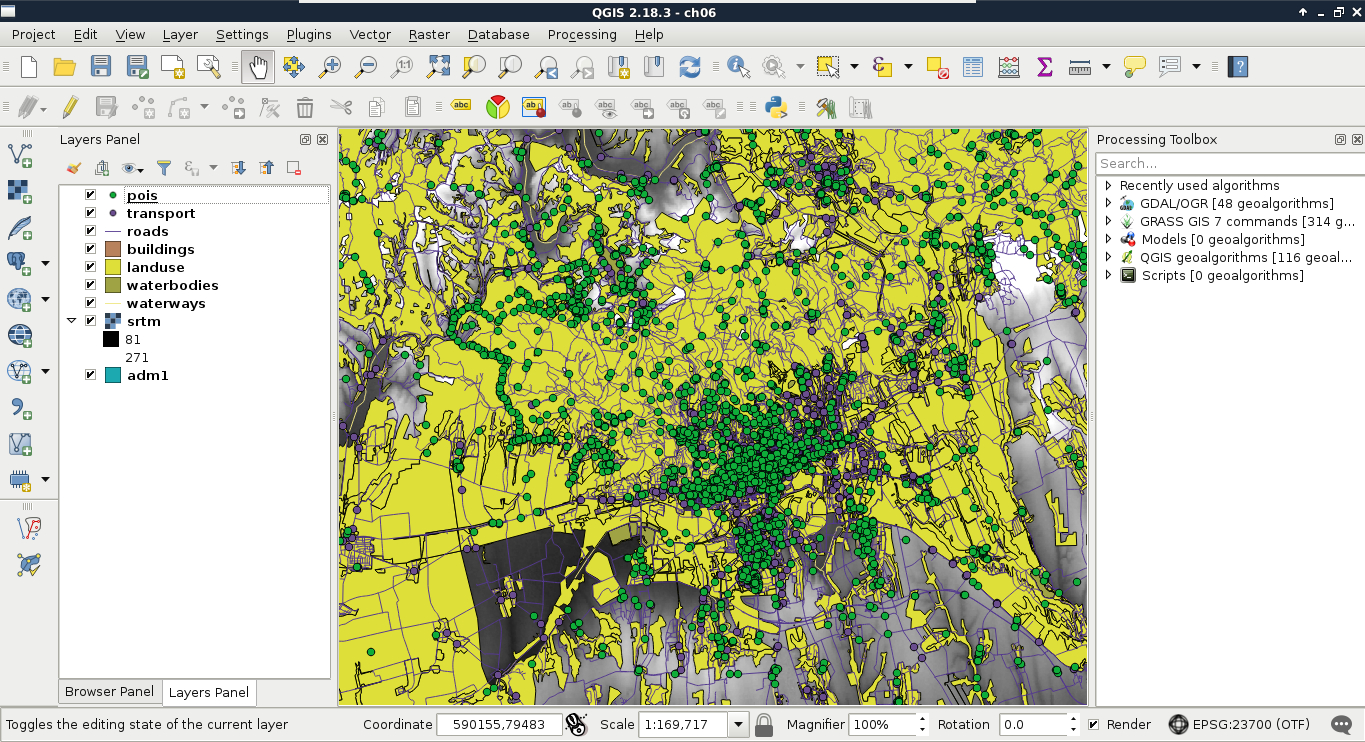

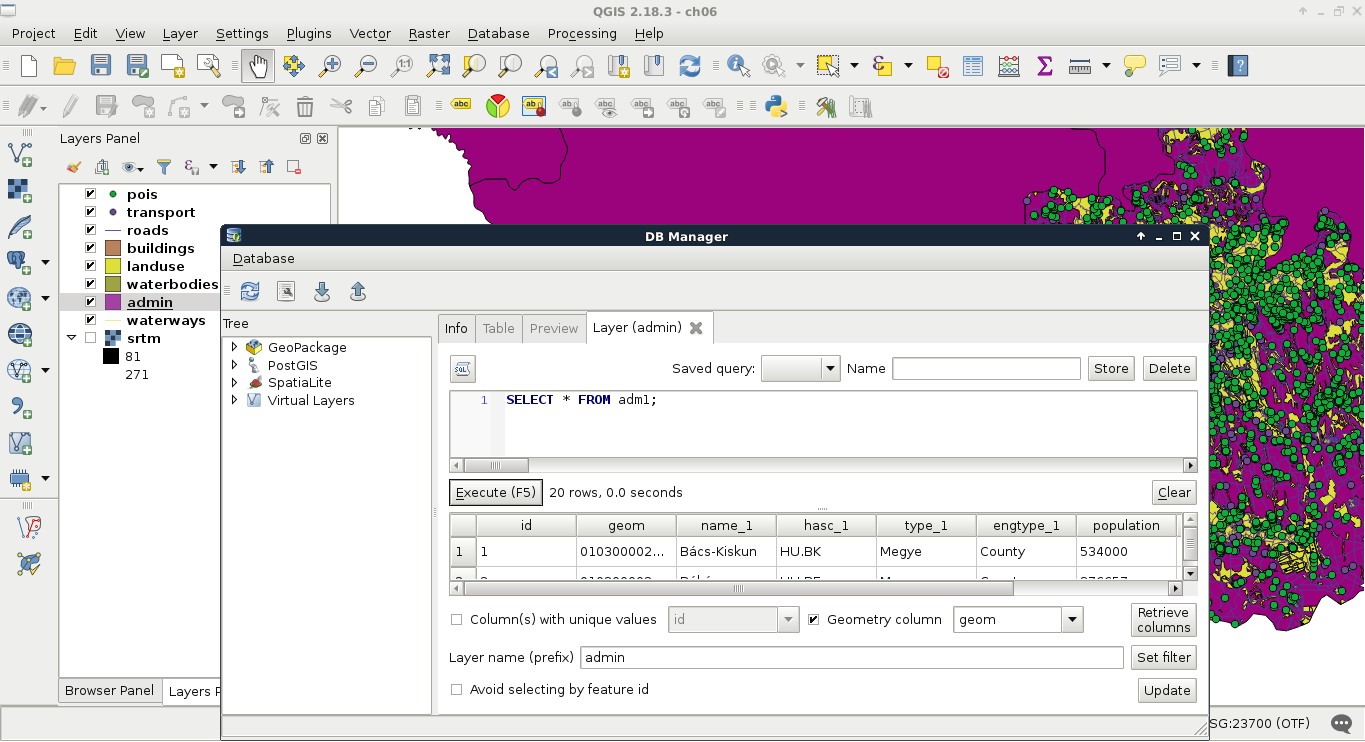

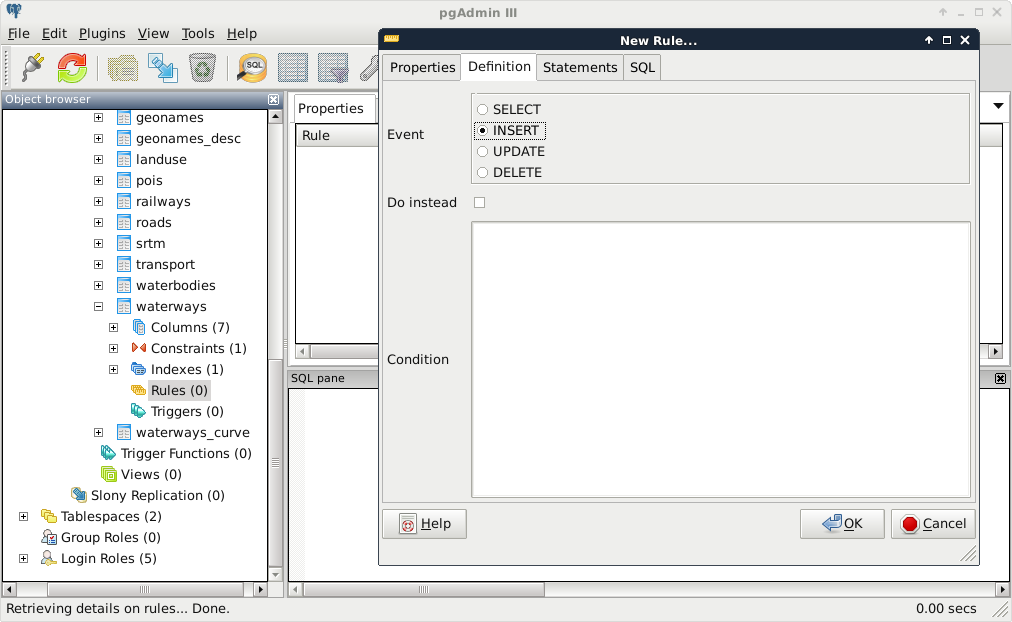

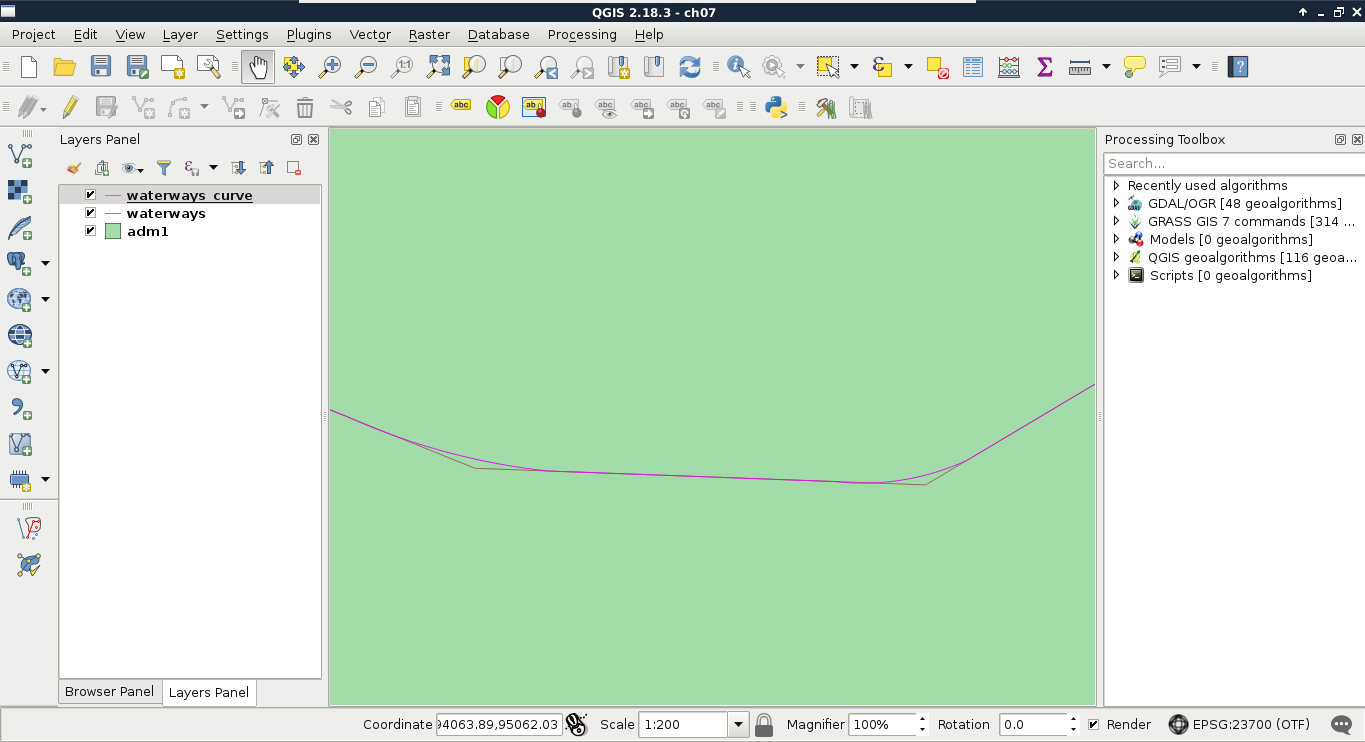

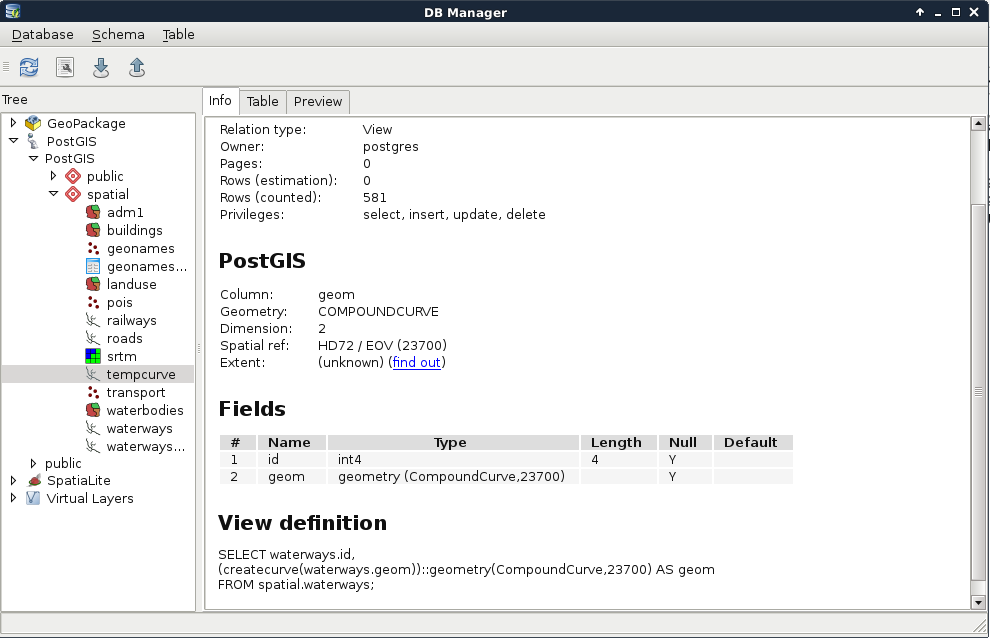

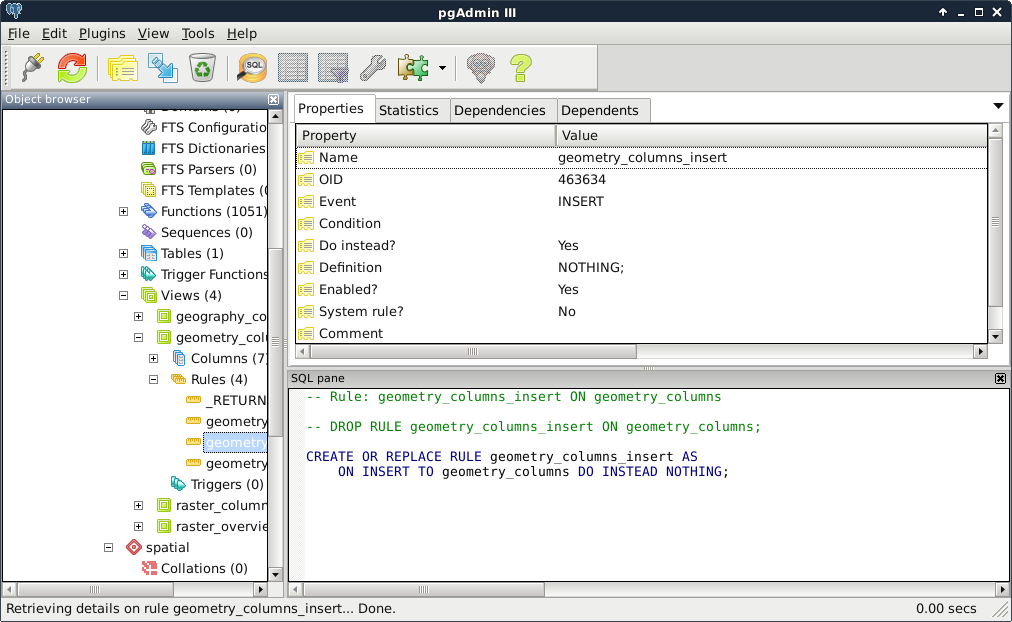

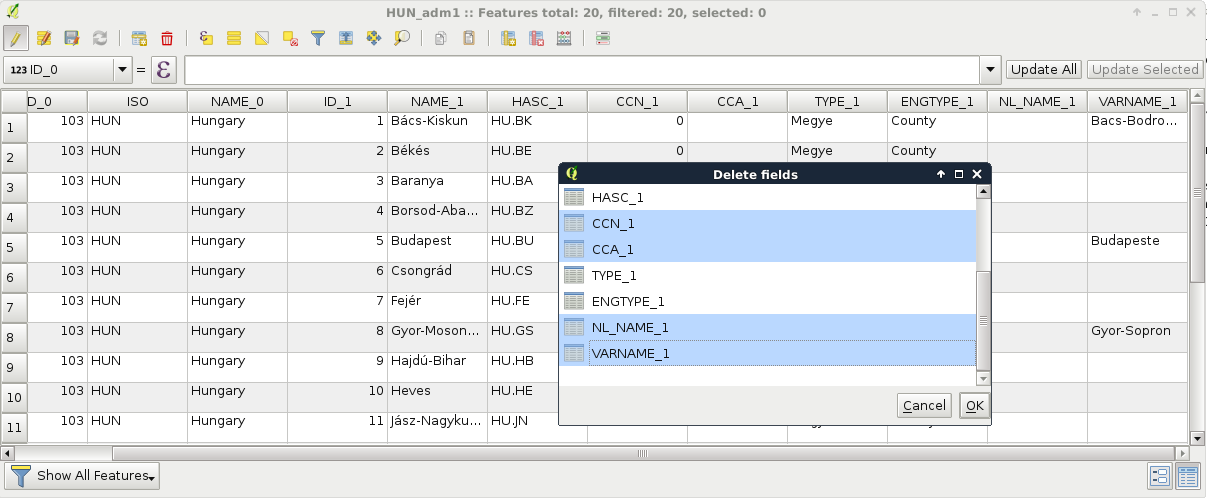

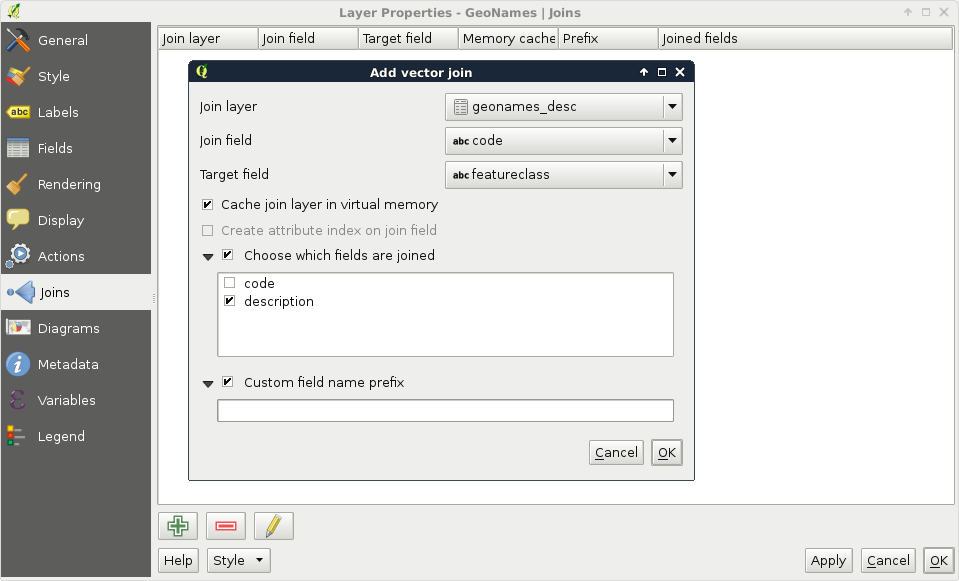

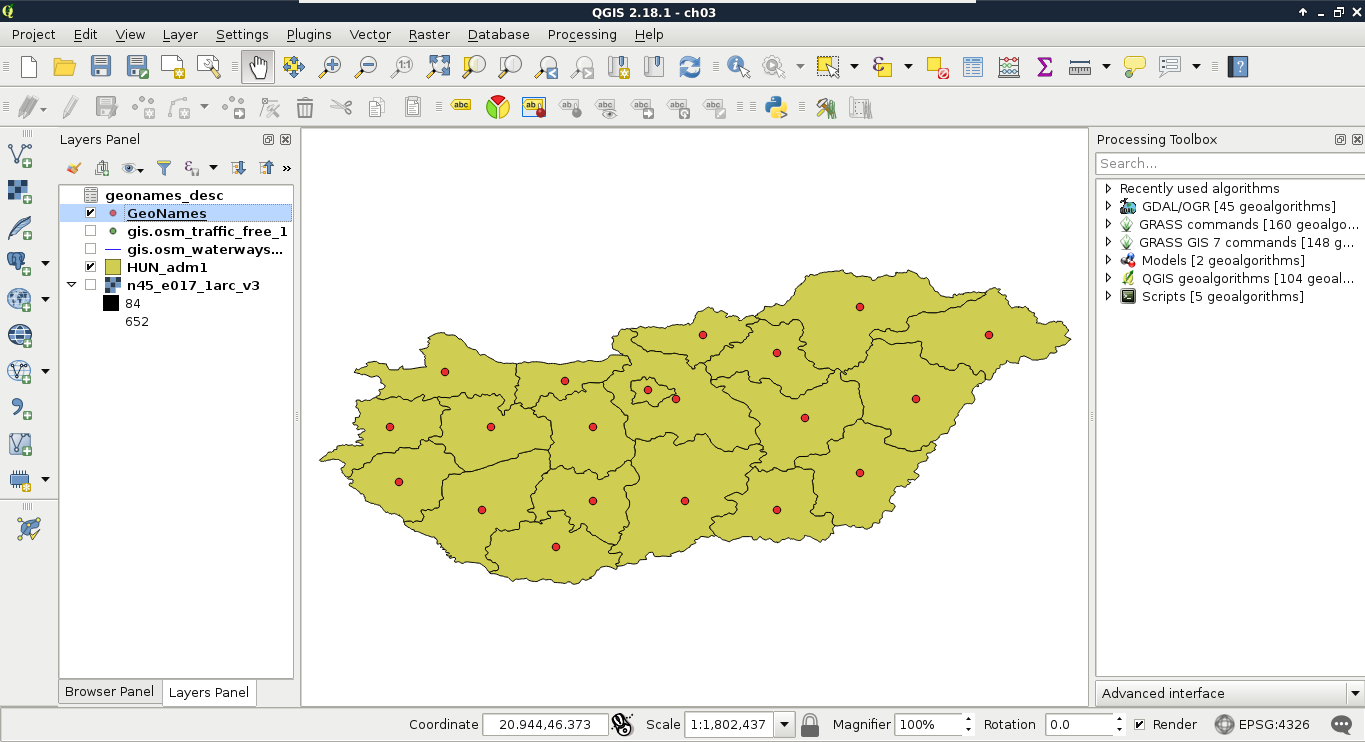

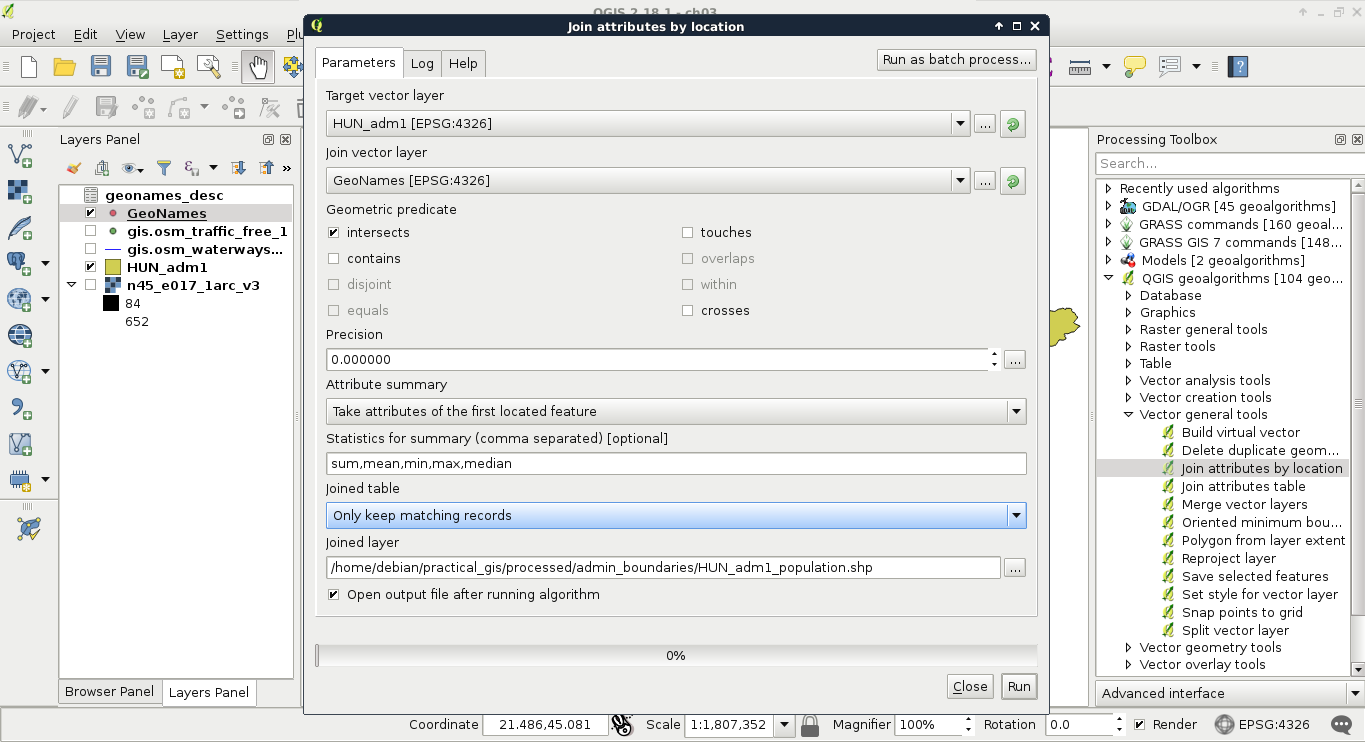

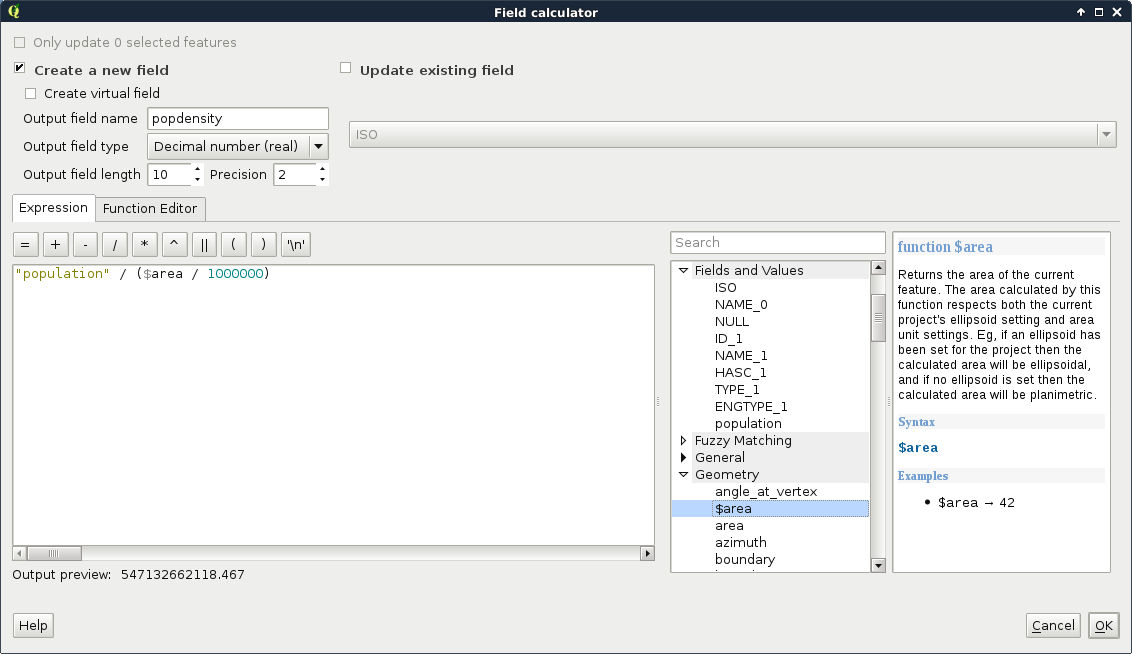

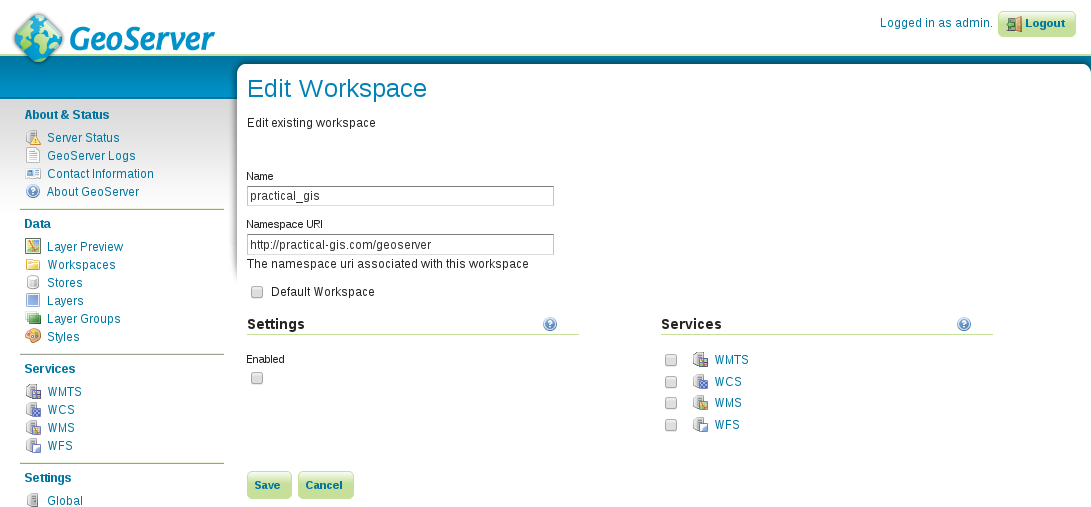

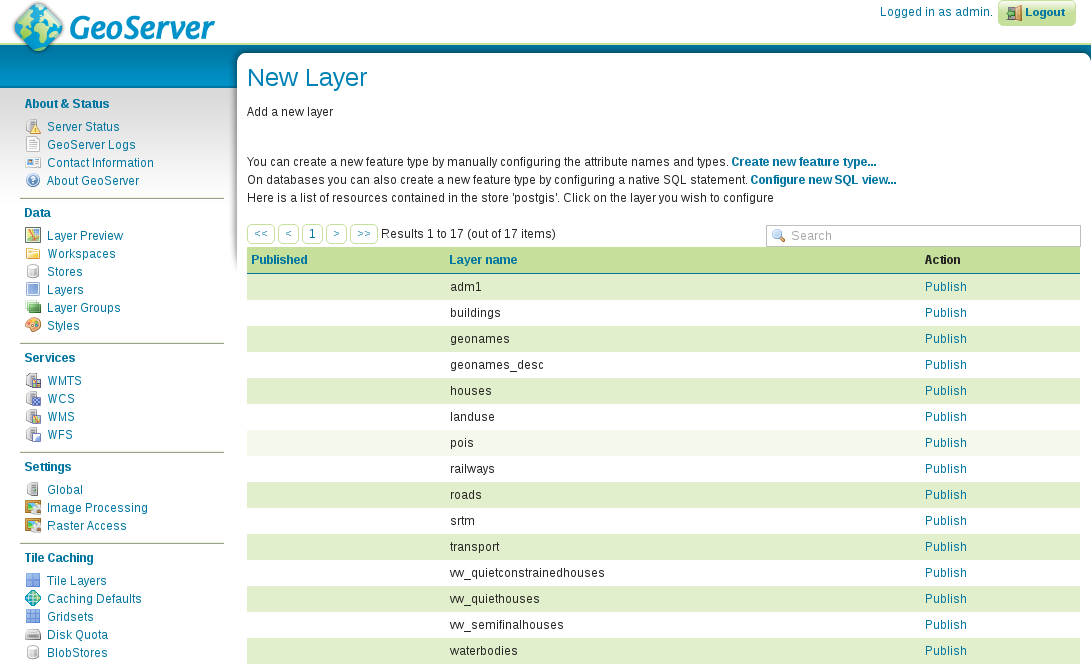

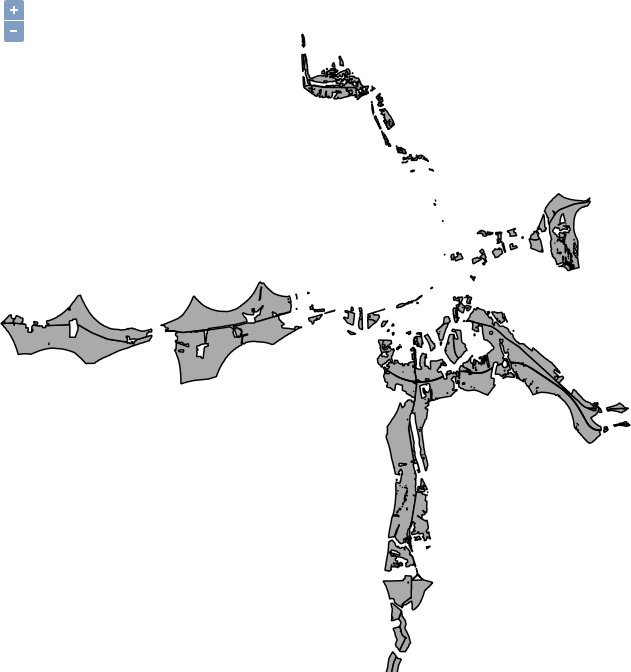

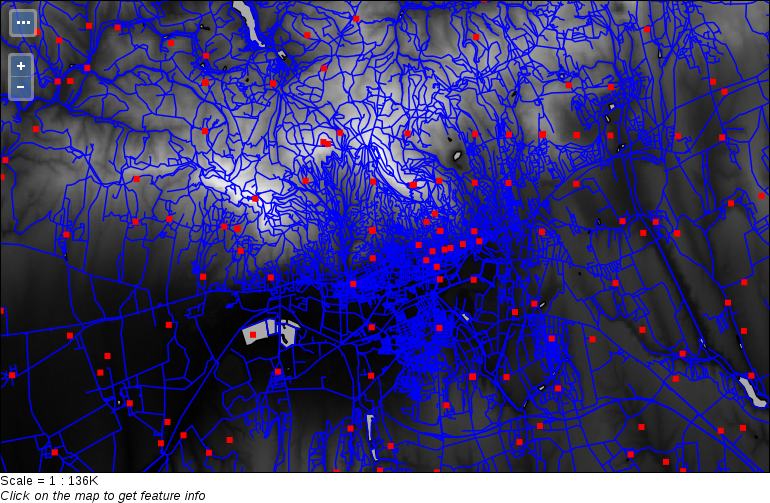

We can not only use the attribute tables of layers, but we can also extend, decrease, or modify them. These are very useful functions for maintaining a layer. For example, as data often comes in a general format with a lot of obsolete attributes, which is practically useless for our analysis, we can get rid of it in a matter of clicks. The size of the attribute table always has an impact on performance; therefore, it is beneficial to not store superfluous data.