The core of a thematic map is surprisingly always its thematics. We can classify our maps based on the most important, most emphasized thematic (for example, we will end up with a road map), but it does not exclude adding more thematics for various cases. We can fill our map if it is too empty, or help the readers by adding more context. In this example, we replace our Landsat imagery by some thematics from the OpenStreetMap dataset. We will visualize land use types, rivers, and water bodies on our map. As we went through styling vector layers quite thoroughly before, we will only discuss the main guidelines to achieve nice results.

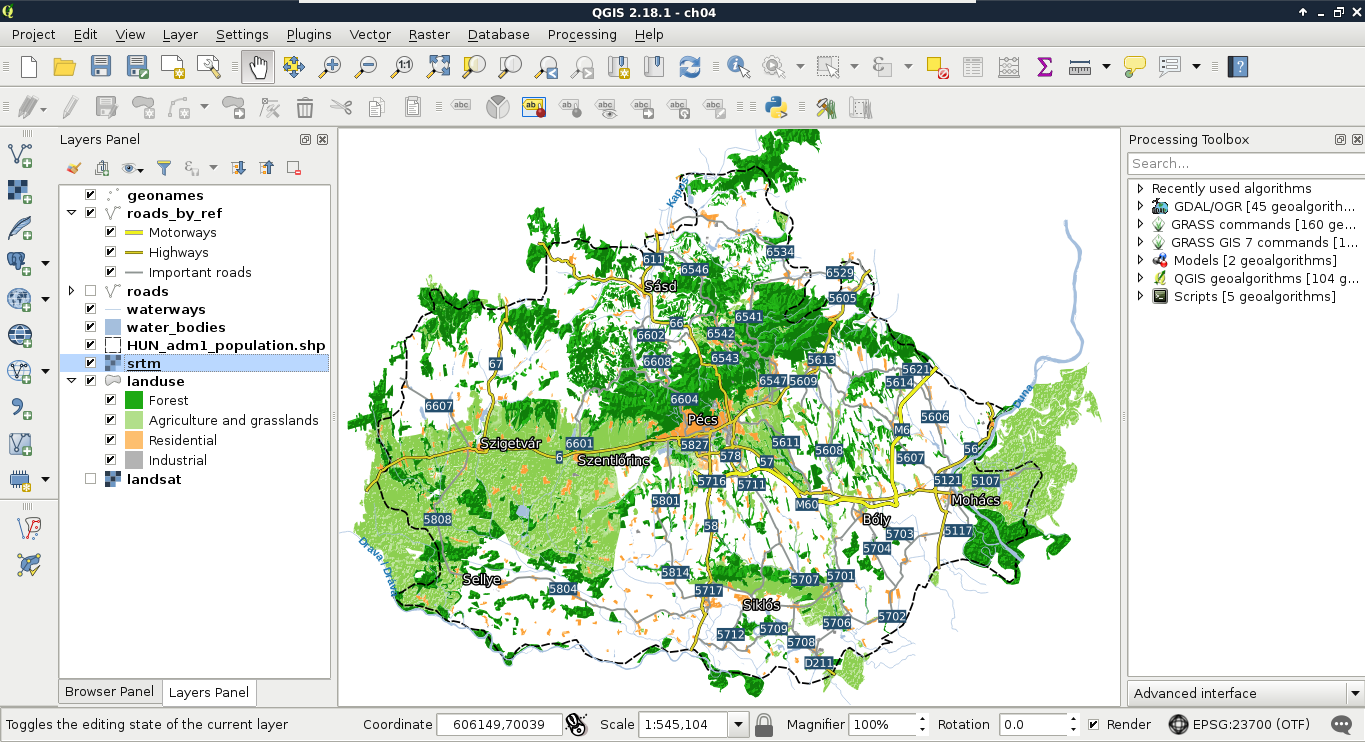

First of all, let's disable our Landsat layer, and enable the layers mentioned before. The first layer we will style is land use, as it will give the most context to the map. If we apply a categorized styling on that layer based on the fclass column, we can see similar results in the roads layer. There are many classes, most of them containing details, which are superfluous for this scale. To get rid of the unnecessary parts, and focus only on the important land use types, let's apply a rule-based styling:

- Forest: Only the forest category with a dark green color

- Agriculture and grassland: The farm, grass, meadow, vineyard, and allotments categories can go here with a light green color

- Residential: The residential category, visualized with a light orange color

- Industrial: The industrial and quarry categories, with a light grey color

As the default black outline would draw too much attention and distract readers, let's apply a 0 mm, No Pen outline style to every category. We can access the outline preferences by clicking on the Simple Fill child style element.

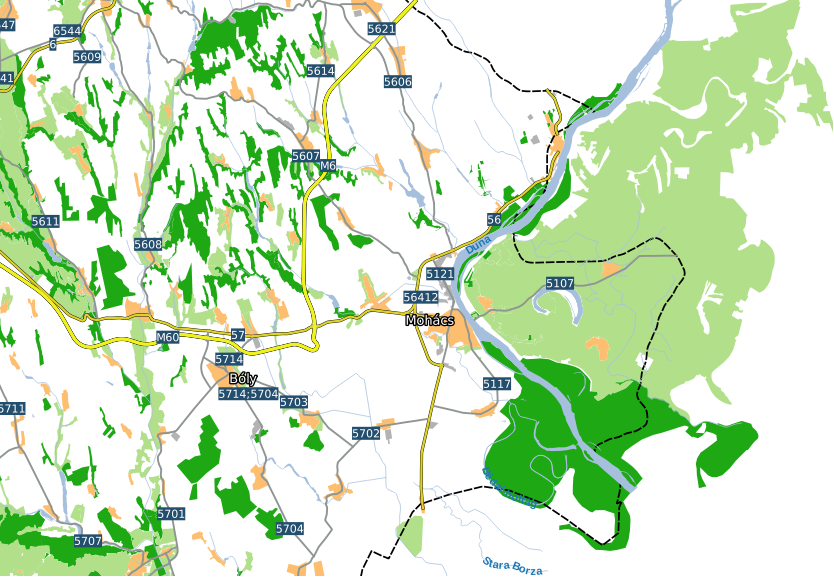

Now we will do a very cool thing. The water bodies layer not only stores lakes and other still water, but also larger rivers in a polygon format. We will not only show these lakes and rivers along with the linear river features, but also label them, making the labels run in the polygons of larger rivers. For this, let's place the river layer on top of the water bodies, and give them the same light blue color.

Next, navigate to the Labels tab of our rivers layer, and select Rule-based labeling. We apply only one rule, which only labels rivers, as we wouldn't like to load the map with labels of smaller waterways. We can build such an expression similarly to the other OSM layers as follows:

"fclass" = 'river'

In the Placement menu, we define the labels to run on a Curved path along the linear features. The only allowed position should be On line, therefore, we uncheck Above line after checking it in. Finally, in the Text menu, we specify the text color to be a darker shade of blue in order to make it go nicely with the rivers' color. I also specified another font, which enabled a Bold typeset.

As the linear features of the rivers run exactly in the middle of the outlines (in the streamline), our labels are run exactly in the middle of the polygons, along the streamlines, which looks really nice and professional:

It's time to add one final piece to our map--topography. For this task, we will need our elevation layers. If we open them all at once, we can see that they have a little overlap, making some linear artifacts. To get rid of these disturbing lines, and to get a more manageable elevation layer at once, we first create a virtual raster from the elevation datasets. Similar to the Landsat imagery, we open Raster | Miscellaneous | Build Virtual Raster from the menu bar. We browse and select every SRTM raster, then select a destination file. We do not have to check anything else, as we would like to create a seamless mosaic from the input rasters, not store them in different bands. We just select a destination folder, and name our new layer. Don't forget to append the vrt extension manually to the file name.

The next step is to pull the new srtm layer strictly above the landuse layer. We are going to style it in a new way to show elevation with shading. Let's open its Style menu, and select the Hillshade option. It will create a shaded relief based on the provided altitude and azimuth values. Those values determine the Sun's location relative to the surface. The default values are generally good for a simple visualization. Finally, let's alter the Blending mode parameter. This parameter defines how our layer are blended with the layers underneath. If we choose Overlay, it blends the shading to the colored parts of our landuse layer, and leaves the white parts. We can also reduce the layer's transparency in the Transparency tab to make the colors less vibrant, and more like the original values: