The Internet is designed to be an infinitely expandable network of computers. Therefore, servers and clients are only the end points of this network--there are additional nodes doing other tasks. For example, there are DNS servers, which map IP addresses to domain names; routers and switches forward the traffic. The web is one of the largest portions of the Internet, sharing specific, standardized content between end points. For creating a web application, the midpoints are out of concern. We only need to know how to configure web servers (backend), and how to write content for web clients (frontend).

In order to have a working architecture, the web is powered by standards instead of software. These are open standards, which define the intended behavior of every step in serving and receiving data on the web, mostly maintained by a large number of experts and companies forming the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). This way, anyone can develop a web server or a web client, which is guaranteed to work with any website if these standards are followed. If not, for example, a web browser that places two line breaks on every <br> element, it is called a bug. No matter if the developers reason that this is an intended feature, as two-line breaks look much better than a single one, the standard is wrong. What do we gain from this strong standardization? We do not have to worry about compatibility issues. The standards make sure we can use Apache, nginx, Node.JS, or any other web server application as a web server, and the hosted files will work on any web browser following them. We only need to make sure that the web server we choose is capable enough for our needs, and the configuration is correct.

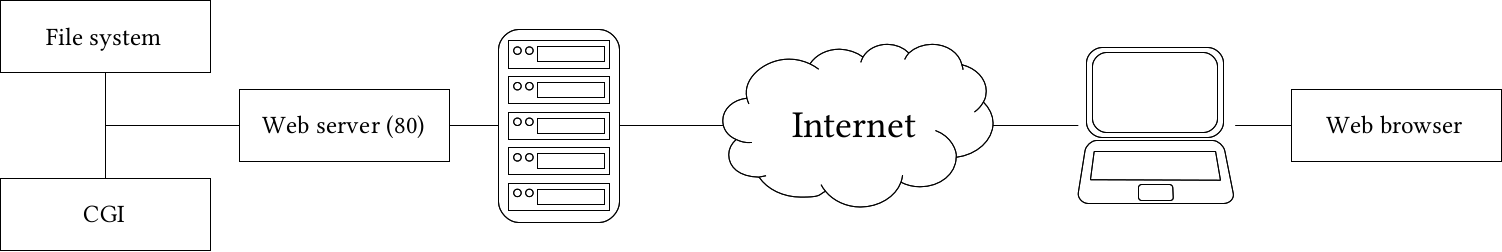

These standards are very specific, therefore, very long and complex. That is why we won't discuss them in detail but grab some of the more important parts from our perspective. In a web architecture, we have a web server, and a client capable of communicating with it (most often a web browser):

- Web server: A server application capable of communicating over the hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP or HTTPS). By default, web servers using HTTP listen on port 80, while the ones using HTTPS listen on port 443. The main responsibility of web servers is to accept HTTP requests, resolve paths, and serve content accordingly. Different web servers have different capabilities, although encrypting data (HTTPS) and compressing responses are often implemented. Web servers can access a portion of the server machine's file system from where they can serve these two kinds of resources:

- Static files: HTML, CSS, JS files, images, and other static resources for the served web page.

- CGI: Server-side scripts that the web server can call with parameters defined in the request as arguments. It resembles a command-line call with the difference that CGI programs must conform to web standards. CGI scripts can be written in any language the server's OS can run as a command-line program (most often, PHP, Python, Ruby, or C).

- Web browser: A client application capable of communicating over the hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP or HTTPS). It can send requests to web servers, and interpret responses. It can handle various types of data like the following received from a web server:

- Plain text: The most basic response type. The browser renders it as plain text.

- Structured text: Markup languages (like HTML and XML), CSS stylesheets, JS programs. The browser parses them, then creates a Document Object Model (DOM), preserving the structure and hierarchy of the source documents. It styles the DOM elements according to the rules in the stylesheets, and interprets the content of the JS files, allowing the JS programs to run on the client.

- Media elements: RGB or RGBA (red, green, blue, alpha) images in common formats (like PNG, JPEG, BMP, and GIF), video files (WEBM, OGG, and MP4), subtitles, audio files (OGG and MP3). The client incorporates these elements into its DOM structure, rendering them in a usable way.

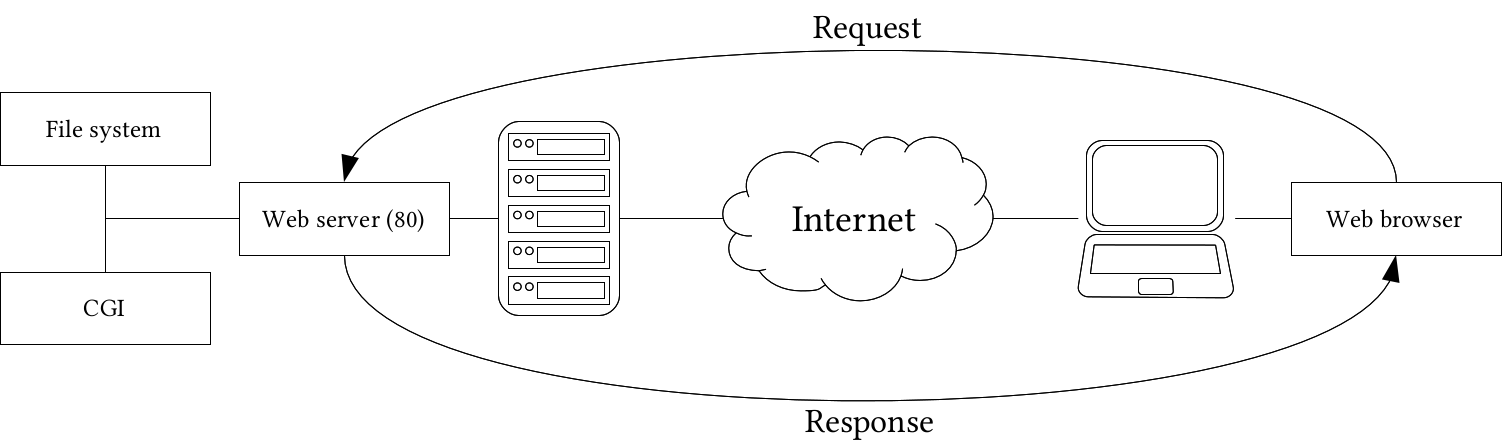

We can see the generalized scheme of the client-server architecture in the following figure:

The next step is the communication between web servers and web clients. There are various standardized requests that a client can send to a web server, which serves content accordingly. The response is also standardized, therefore, the client can interpret it:

- Request: The web client sends a request to a destination identified with a URL. The URL contains the destination server machine's IP address or domain name followed by the relative path to the requested resource from the web server's root folder (that is, the folder which holds the portion of the file system the web server has access to). If no port is specified, the client automatically sends HTTP requests to port 80, and HTTPS requests to port 443. The request additionally holds some headers, the type of the request, and optionally, some other content. There are these two important types from our perspective:

- GET: In a GET request, everything is encoded into the URL. If a script is specified as the destination, the parameters are encoded in the URL as key-value pairs separated with a =. The start of the parameters are marked with ?, while the parameter separator is &. A GET request with a CGI script can look like the following: http://mysite.com/script.php?param1=value1¶m2=value2. There is no per standard character limit on GET requests, but as they are basically URLs, using it for sending a very long representation of a complex geometry for example is impractical.

- POST: POST requests are exclusively used with CGI scripts. In the URL, only the destination is specified; the parameters are contained in the body of the request. POST requests leave no trace, therefore, they are good for sending sensitive data to the server (for example, authentication). They are also commonly used to send insensitive form data in bulk, or to upload files to the server.

- Response: If a web server is listening on the specified server's specified port, it receives the request data. If a static resource is requested by a GET request, it simply serves it as is. If a CGI script is the destination resource, it parses the parameters specified in the URL or in the POST request's body, and supplies them to the CGI script. It waits for the response of the script, then sends that response back to the web client.