Unlike C, C++ is an object-oriented programming language, following a programming model that uses objects that contain data as well as functions to manipulate the data. The functions in object-oriented programming are like functions in C programs, except that they are associated with a particular object or class of objects. Functions within a C++ class are often called methods to draw a distinction. Although many features of object-oriented programming are irrelevant to malware analysis because they do not impact the assembly, a few can complicate analysis.

Note

To learn more about C++, consider reading Thinking in C++ by Bruce Eckel, available as a free download from http://www.mindviewinc.com/.

In object-orientation, code is arranged in user-defined data types called classes. Classes are like structs, except that they store function information in addition to data. Classes are like a blueprint for creating an object—one that specifies the functions and data layout for an object in memory.

When executing object-oriented C++ code, you use the class to create an object of the class. This object is referred to as an instance of the class. You can have multiple instances of the same class. Each instance of a class has its own data, but all objects of the same type share the same functions. To access data or call a function, you must reference an object of that type.

Example 20-1 shows a simple C++ program with a class and a single object.

Example 20-1. A simple C++ class

class SimpleClass {

public:

int x;

void HelloWorld() {

printf("Hello World\n");

}

};

int _tmain(int argc, _TCHAR* argv[])

{

SimpleClass myObject;

myObject.HelloWorld();

}In this example, the class is called SimpleClass. It has

one data element, x, and a single function, HelloWorld. We create an instance of SimpleClass named myObject and call the HelloWorld function for that object. (The public keyword is a compiler-enforced abstraction mechanism with no impact on the

assembly code.)

As we have established, data and functions are associated with objects. In order to access a

piece of data, you use the form ObjectName.variableName. Functions are called similarly with

ObjectName.functionName. For example, in

Example 20-1, if we wanted to access the x variable, we would use myObject.x.

In addition to accessing variables using the object name and the variable name, you can also access variables for the current object using only the variable name. Example 20-2 shows an example.

Example 20-2. A C++ example with the this pointer

class SimpleClass {

public:

int x;

void HelloWorld() {

if (❶x == 10) printf("X is 10.\n");

}

...

};

int _tmain(int argc, _TCHAR* argv[])

{

SimpleClass myObject;

❷myObject.x = 9;

❸myObject.HelloWorld();

SimpleClass myOtherObject;

myOtherOject.x = 10;

myOtherObject.HelloWorld();

}In the HelloWorld function, the variable x is accessed as just x at ❶, and not ObjectName.x. That same variable, which

refers to the same address in memory, is accessed in the main method at ❷ using myObject.x.

Within the HelloWorld method, the variable can be accessed

just as x because it is assumed to refer to the object that was

used to call the function, which in the first case is myObject

❸. Depending on which object is used to call the

HelloWorld function, a different memory address storing the

x variable will be accessed. For example, if the function were

called with myOtherObject.HelloWorld, then an x reference at ❶ would access

a different memory location than when that is called with myObject.HelloWorld. The this pointer is used to keep

track of which memory address to access when accessing the x

variable.

The this pointer is implied in every variable access within

a function that doesn’t specify an object; it is an implied parameter to every object function

call. Within Microsoft-generated assembly code, the this

parameter is usually passed in the ECX register, although sometimes ESI is used instead.

In Chapter 6, we covered the stdcall, cdecl, and fastcall calling conventions. The C++ calling convention for the this pointer is often called thiscall. Identifying

the thiscall convention can be one easy way to identify

object-oriented code when looking at disassembly.

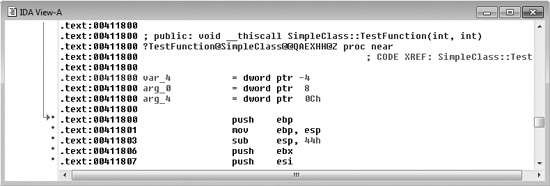

The assembly in Example 20-3, generated from

Example 20-2, demonstrates the usage of the this pointer.

Example 20-3. The this pointer shown in disassembly

;Main Function 00401100 push ebp 00401101 mov ebp, esp 00401103 sub esp, 1F0h 00401109 ❶mov [ebp+var_10], offset off_404768 00401110 ❷mov [ebp+var_C], 9 00401117 ❸lea ecx, [ebp+var_10] 0040111A call sub_4115D0 0040111F mov [ebp+var_34], offset off_404768 00401126 mov [ebp+var_30], 0Ah 0040112D lea ecx, [ebp+var_34] 00401130 call sub_4115D0 ;HelloWorld Function 004115D0 push ebp 004115D1 mov ebp, esp 004115D3 sub esp, 9Ch 004115D9 push ebx 004115DA push esi 004115DB push edi 004115DC mov ❹[ebp+var_4], ecx 004115DF mov ❺eax, [ebp+var_4] 004115E2 cmp dword ptr [eax+4], 0Ah 004115E6 jnz short loc_4115F6 004115E8 push offset aXIs10_ ; "X is 10.\n" 004115ED call ds:__imp__printf

The main method first allocates space on the stack. The beginning of the object is stored at

var_10 on the stack at ❶. The first data value stored in that object is the variable x, which is set at an offset of 4 from the beginning of the object. The value x is accessed at ❷ and is

labeled var_C by IDA Pro. IDA Pro can’t determine whether

the values are both part of the same object, and it labels x as a

separate value. The pointer to the object is then placed into ECX for the function call ❸. Within the HelloWorld

function, the value of ECX is retrieved and used as the this

pointer ❹. Then at an offset of 4, the code accesses the

value for x

❺. When the main function calls HelloWorld for the second time, it loads a different pointer into ECX.

C++ supports a coding construct known as method overloading, which is the ability to have multiple functions with the same name, but that accept different parameters. When the function is called, the compiler determines which version of the function to use based on the number and types of parameters used in the call, as shown in Example 20-4.

Example 20-4. Function overloading example

LoadFile (String filename) {

...

}

LoadFile (String filename, int Options) {

...

}

Main () {

LoadFile ("c:\myfile.txt"); //Calls the first LoadFile function

LoadFile ("c:\myfile.txt", GENERIC_READ); //Calls the second LoadFile

}As you can see in the listing, there are two LoadFile

functions: one that takes only a string and another that takes a string and an integer. When the

LoadFile function is called within the main method, the compiler

selects the function to call based on the number of parameters supplied.

C++ uses a technique called name mangling to support method overloading. In the PE file format, each function is labeled with only its name, and the function parameters are not specified in the compiled binary format.

To support overloading, the names in the file format are modified so that the name information

includes the parameter information. For example, if a function called TestFunction is part of the SimpleClass class and

accepts two integers as parameters, the mangled name of that function would be ?TestFunction@SimpleClass@@QAEXHH@Z.

The algorithm for mangling the names is compiler-specific, but IDA Pro can demangle the names

for most compilers. For example, Figure 20-1 shows the

function TestFunction. IDA Pro demangles the function and shows

the original name and parameters.

The internal function names are visible only if there are symbols in the code you are analyzing. Malware usually has the internal symbols removed; however, some imported or exported C++ functions with mangled names may be visible in IDA Pro.

Inheritance is an object-oriented programming concept in which

parent-child relationships are established between classes. Child classes inherit functions and data

from parent classes. A child class automatically has all the functions and data of the parent class,

and usually defines additional functions and data. For example, Example 20-5 shows a class called Socket.

Example 20-5. Inheritance example

class Socket {

...

public:

void setDestinationAddr (INetAddr * addr) {

...

}

...

};

class UDPSocket : publicSocket {

public:

❶void sendData (char * buf, INetAddr * addr) {

❷ setDestinationAddr(addr)

...

}

...

};The Socket class has a function to set the destination

address, but it has no function to sendData because it’s

not a specific type of socket. A child class called UDPSocket can

send data and implements the sendData function at ❶, and it can also call the setDestinationAddr function defined in the Socket

class.

In Example 20-5, the sendData

function at ❶ can call the setDestinationAddr function at ❷ even though

that function is not defined in the UDPSocket class, because the

functionality of the parent class is automatically included in the child class.

Inheritance helps programmers more efficiently reuse code, but it’s a feature that does not require any runtime data structures and generally isn’t visible in assembly code.