One of IDA Pro’s best features is that it allows you to modify its disassembly to suit your goals. The changes that you make can greatly increase the speed with which you can analyze a binary.

IDA Pro does a good job of automatically naming virtual address and stack variables, but you

can also modify these names to make them more meaningful. Auto-generated names (also known as

dummy names) such as sub_401000 don’t

tell you much; a function named ReverseBackdoorThread would be a

lot more useful. You should rename these dummy names to something more meaningful. This will also

help ensure that you reverse-engineer a function only once. When renaming dummy names, you need to

do so in only one place. IDA Pro will propagate the new name wherever that item is

referenced.

After you’ve renamed a dummy name to something more meaningful, cross-references will

become much easier to parse. For example, if a function sub_401200 is called many times throughout a program and you rename it to DNSrequest, it will be renamed DNSrequest throughout the program. Imagine how much time this will save you during

analysis, when you can read the meaningful name instead of needing to reverse the function again or

to remember what sub_401200 does.

Table 5-2 shows an example of how we might rename local

variables and arguments. The left column contains an assembly listing with no arguments renamed, and

the right column shows the listing with the arguments renamed. We can actually glean some

information from the column on the right. Here, we have renamed arg_4 to port_str and var_598 to port. You can see that these renamed

elements are much more meaningful than their dummy names.

IDA Pro lets you embed comments throughout your disassembly and adds many comments automatically.

To add your own comments, place the cursor on a line of disassembly and press the colon (:) key on your keyboard to bring up a comment window. To insert a repeatable comment to be echoed across the disassembly window whenever there is a cross-reference to the address in which you added the comment, press the semicolon (;) key.

When disassembling, IDA Pro makes decisions regarding how to format operands for each instruction that it disassembles. Unless there is context, the data displayed is typically formatted as hex values. IDA Pro allows you to change this data if needed to make it more understandable.

Table 5-2. Function Operand Manipulation

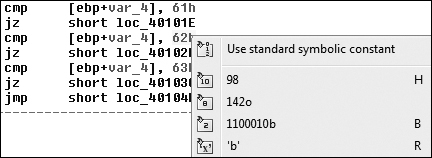

Figure 5-10 shows an example of modifying operands

in an instruction, where 62h is compared to the local variable

var_4. If you were to right-click 62h, you would be presented with options to change the 62h into 98 in decimal, 142o in octal,

1100010b in binary, or the character b in

ASCII—whatever suits your needs and your situation.

To change whether an operand references memory or stays as data, press the O key on your

keyboard. For example, suppose when you’re analyzing disassembly with a link to loc_410000, you trace the link back and see the following

instructions:

mov eax, loc_410000 add ebx, eax mul ebx

At the assembly level, everything is a number, but IDA Pro has mislabeled the number 4259840 (0x410000 in hex) as a reference to the address 410000. To correct this mistake, press the O key to change this address to the number 410000h and remove the offending cross-reference from the disassembly window.

Malware authors (and programmers in general) often use named

constants such as GENERIC_READ in their source code.

Named constants provide an easily remembered name for the programmer, but they are implemented as an

integer in the binary. Unfortunately, once the compiler is done with the source code, it is no

longer possible to determine whether the source used a symbolic constant or a literal.

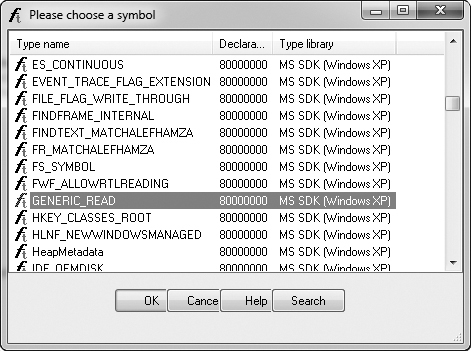

Fortunately, IDA Pro provides a large catalog of named constants for the Windows API and the C

standard library, and you can use the Use Standard Symbolic Constant option (shown in Figure 5-10) on an operand in your disassembly. Figure 5-11 shows the window that appears when you select Use

Standard Symbolic Constant on the value 0x800000000.

The code snippets in Table 5-3 show the effect

of applying the standard symbolic constants for a Windows API call to CreateFileA. Note how much more meaningful the code is on the right.

Note

To determine which value to choose from the often extensive list provided in the standard symbolic constant window, you will need to go to the MSDN page for the Windows API call. There you will see the symbolic constants that are associated with each parameter. We will discuss this further in Chapter 7, when we discuss Windows concepts.

Sometimes a particular standard symbolic constant that you want will not appear, and you will

need to load the relevant type library manually. To do so, select View

▶ Open Subviews ▶ Type Libraries to view the currently loaded libraries.

Normally, mssdk and vc6win

will automatically be loaded, but if not, you can load them manually (as is often necessary with

malware that uses the Native API, the Windows NT family API). To get the symbolic constants for the

Native API, load ntapi (the Microsoft Windows NT 4.0 Native API).

In the same vein, when analyzing a Linux binary, you may need to manually load the gnuunx (GNU C++ UNIX) libraries.

Table 5-3. Code Before and After Standard Symbolic Constants

When IDA Pro performs its initial disassembly of a program, bytes are occasionally categorized incorrectly; code may be defined as data, data defined as code, and so on. The most common way to redefine code in the disassembly window is to press the U key to undefine functions, code, or data. When you undefine code, the underlying bytes will be reformatted as a list of raw bytes.

To define the raw bytes as code, press C. For example, Table 5-4 shows a malicious PDF document named paycuts.pdf. At offset 0x8387 into the file, we discover shellcode (defined as raw bytes) at ❶, so we press C at that location. This disassembles the shellcode and allows us to discover that it contains an XOR decoding loop with 0x97 at ❷.

Depending on your goals, you can similarly define raw bytes as data or ASCII strings by pressing D or A, respectively.