First, we run PEiD on the Lab18-03.exe file, and it tells us that the packer is PECompact 1.68 - 1.84 -> Jeremy Collake. We load the program into OllyDbg and see several warnings that the file may be packed. We can ignore these warnings.

The program starts at address 0x00405130. We try the Find OEP by Section Hop (Trace Into) option in the OllyDump plug-in. We see the code shown in Example C-176 as OllyDump’s guess at the OEP. However, there are several reasons this doesn’t look like the OEP. The most obvious is that it accesses values above the base pointer at ❶. If this were the file’s entry point, any data above the base pointer would not have been initialized.

Example C-176. OllyDump’s guess at the OEP after using the Find OEP by Section Hop (Trace Into) option

0040A110 ENTER 0,0

0040A114 PUSH EBP

0040A115 ❶MOV ESI,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP+8]

0040A118 MOV EDI,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP+C]

0040A11B CLD

0040A11C MOV DL,80

0040A11E MOV AL,BYTE PTR DS:[ESI]

0040A120 INC ESI

0040A121 MOV BYTE PTR DS:[EDI],ALNext, we try the Find OEP by Section Hop (Trace Over)

option and we see that the code stops on a ret instruction at the

end of a function in ntdll, which is clearly not the OEP.

Since the OllyDump plug-in didn’t work, we examine the code to see if the tail jump is

easy to spot. As shown in Example C-177, we eventually come to some code that

looks like a tail jump. This code is a retn instruction followed

by a bunch of zero bytes. We know that the code can’t go past this point.

Example C-177. A possible tail jump

00405622 SCAS DWORD PTR ES:[EDI]

00405623 ADD BH,CH

00405625 STC

00405626 ❶RETN 0EC3F

00405629 ADD BYTE PTR DS:[EAX],AL

0040562B ADD BYTE PTR DS:[EAX],AL

0040562D ADD BYTE PTR DS:[EAX],ALNow, we set a breakpoint on the retn instruction at

❶ and start our program. First, we set a regular

breakpoint (INT 3). OllyDbg displays a warning, because the

breakpoint is outside the code section and may cause problems. When we run our program, we

eventually get an exception that the program can’t handle, and we see that the code at our

breakpoint has been changed. Now we know that the code is self-modifying and that our breakpoint has

not worked properly.

When dealing with self-modifying code, it’s often useful to use a hardware breakpoint

instead of a software breakpoint because the self-modifying code will overwrite the INT 3 (0xcc) instruction used to implement software breakpoints. Starting

over with a hardware breakpoint, we run the program and see that it starts to run without ever

hitting our breakpoint. This tells us that we probably haven’t found the tail jump and we need

to try another strategy.

Looking at the entry point of the packed program, we see the instructions shown in Example C-178.

Example C-178. Start of the unpacking stub

00405130 ❶JMP SHORT Lab09-02.00405138 00405132 PUSH 1577 00405137 RETN 00405138 ❷PUSHFD 00405139 ❸PUSHAD 0040513A ❹CALL Lab09-02.00405141 0040513F XOR EAX,EAX

The first instruction at ❶ is an unconditional

jump that skips the next two instructions. The first two instructions that affect memory are

pushfd at ❷ and

pushad at ❸. These

instructions save all of the registers and flags. It’s likely that the packing program will

restore all the registers and flags immediately before it jumps to the OEP, so we can try to find

the OEP by setting an access breakpoint on the stack. Presumably, there will be a popad or popfd instruction right before

the tail jump, which will lead us to the OEP.

We restart the program and step-over the first three instructions. The program should be

stopped at the call instruction at ❹ in Example C-178. Now we need to

find the value of the stack pointer to set a breakpoint. To do so, we examine the registers window,

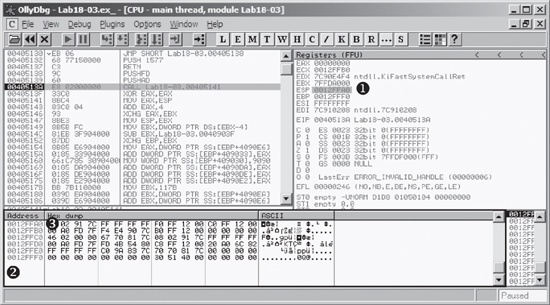

as shown on the top right of Figure C-67.

The stack is at address 0x12FFA0, as shown at ❶ in Figure C-67. To set a breakpoint, we first load that address in the memory dump by right-clicking ❶ and selecting Follow in Dump. This will make the memory dump window at ❷ appear as it does in Figure C-67.

To set a breakpoint on the last piece of data pushed onto the stack, we right-click the first data element on the stack at ❸ in Figure C-67 and select Breakpoint ▸ Memory on Access. We then run our program. Unfortunately, it reaches an unhandled exception similar to when we set a breakpoint before. Next, we set the breakpoint with Breakpoint ▸ Hardware, on Access ▸ Dword. When we start our program, our breakpoint is triggered. The program will break at the instructions shown in Example C-179.

Example C-179. Instructions where our stack breakpoint is triggered showing the tail jump

0040754F POPFD 00407550 PUSH EAX 00407551 PUSH Lab18-03.00401577 00407556 RETN 4

A few instructions into our code, we see a retn instruction

that transfers execution to another location. This is probably the tail jump. We step to that

instruction to determine where it goes and see the code in Example C-180. This

looks like the original code; the call to GetVersion at ❷ is a dead giveaway.

Note

As in Lab18-02.exe, you may need to force OllyDbg to disassemble this code using the Analysis ▸ Analyze Code command.

Example C-180. The OEP for Lab 18-3 Solutions

00401577 ❶PUSH EBP 00401578 MOV EBP,ESP 0040157A PUSH -1 0040157C PUSH Lab18-03.004040C0 00401581 PUSH Lab18-03.0040203C ; SE handler installation 00401586 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR FS:[0] 0040158C PUSH EAX 0040158D MOV DWORD PTR FS:[0],ESP 00401594 SUB ESP,10 00401597 PUSH EBX 00401598 PUSH ESI 00401599 PUSH EDI 0040159A MOV DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-18],ESP 0040159D ❷CALL DWORD PTR DS:[404030] ; kernel32.GetVersion

Now, with EIP pointing to the first instruction at ❶, we select Plugins ▸ OllyDump ▸ Dump Debugged Process. We click the Get EIP as OEP button, leaving all the other options with their default settings, and then click Dump. In the dialog, we enter a filename to save a copy of our unpacked program.

When we’re finished, we run the program and open it in IDA Pro to verify that it has been unpacked successfully. A brief analysis of the program reveals that the functionality is the same as Lab09-02.exe.

This packer uses a variety of techniques to make it difficult to unpack and recognize the tail jump. Several of the usual strategies were ineffective because the packer takes explicit steps to thwart them. If using a particular technique seems difficult on a packed program, try different approaches until one works. In rare cases, none of the techniques will work easily.