Lab13-02.exe creates large, seemingly random files in its current directory with names that start with temp and end with eight hexadecimal digits that vary for each file.

The XOR search technique identifies potential encoding-related functions at

sub_401570andsub_401739. The other three techniques suggested find nothing.The encoding functions might be found just before the call to

WriteFile.The encoding function is

sub_40181F.The source content is a screen capture.

The algorithm is nonstandard and not easily determined, so the easiest way to decode traffic is via instrumentation.

See the detailed analysis for how to recover the original source of an encoded file.

We launch the malware and see that it creates new files at a regular interval in its current directory. These files are fairly large (multiple megabytes) and contain seemingly random data with filenames that start with temp and end with some random-looking characters, something like the ones shown in Example C-101.

Example C-101. Example filenames created by Lab13-02.exe

temp062da212 temp062dcb25 temp062df572 temp062e1f50 temp062e491f

Next, we search the malware for evidence of encoding techniques using static analysis. The

PEiD KANAL plug-in, FindCrypt2 plug-in for IDA Pro, and IDA Entropy Plugin fail to find anything of

interest. However, a search for xor instructions yields the

results shown in Table C-5.

Table C-5. The xor Instructions Found in

Lab13-02.exe

Address | Function | Instruction | |

|---|---|---|---|

00401040 |

|

|

|

004012D6 |

|

|

|

0040171F | ❺ |

|

|

0040176F |

|

|

|

0040177A |

|

|

|

00401785 |

|

|

|

00401795 |

|

|

|

004017A1 |

|

|

|

004017AC |

|

|

|

004017BD |

|

|

|

004017C9 |

|

|

|

004017D4 |

|

|

|

004017E5 |

|

|

|

004017F1 |

|

|

|

004017FC |

|

|

|

0040191E |

|

|

|

0040311A |

|

| |

0040311E |

|

| |

00403688 |

|

| |

004036A5 |

|

| |

The instructions labeled ❶ in Table C-5 represent the clearing of a register and can be

ignored. The instructions labeled ❷ are contained in

library functions and can also be ignored. We are left with two functions of interest: sub_40128D

❸ and sub_401739

❹. Additionally, at 0x0040171F is in an area of code

❺ that has not been defined as a function.

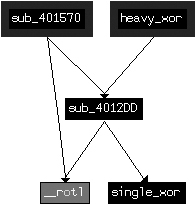

We’ll refer to sub_401739 as heavy_xor since it has so many xor instructions, and

sub_40128D as single_xor since

it has only one. heavy_xor takes four arguments, and it is a

single loop with a large block of code containing many SHL and

SHR instructions in addition to the xor instructions. Looking at the functions called by heavy_xor, we see that single_xor is related to

heavy_xor since the caller of single_xor is also called by heavy_xor, as shown in

Figure C-48.

Looking at the xor instruction at ❺ in Table C-5

(0x0040171F), we see that it is in a function, but the function was not automatically identified due

to lack of use. Defining a function at 0x00401570 results in the creation of a function that

encompasses the previously orphaned xor instruction. As seen in

Figure C-48, this unused function is also related to the

same cluster of likely encoding functions.

To confirm that heavy_xor is the encoding function,

let’s see how it is related to the temp files that were written to disk.

We can find where the data is written to disk, and then trace backward to determine if and how

encoding functions are used. Looking at the imported functions, we see WriteFile.

Checking the cross-references to WriteFile, we find

sub_401000, which takes as arguments a buffer, a length, and a

filename, and opens the file and writes the buffer to the file. We’ll rename sub_401000 to writeBufferToFile. sub_401851 is the only function that calls writeBufferToFile, and Example C-102 shows the contents of

sub_401851 (which we rename doStuffAndWriteFile), leading up to the call to writeBufferToFile at ❶.

Example C-102. Writing encrypted files

lea eax, [ebp+nNumberOfBytesToWrite] push eax lea ecx, [ebp+lpBuffer] push ecx call sub_401070 ❷ ; renamed to getContent add esp, 8 mov edx, [ebp+nNumberOfBytesToWrite] push edx mov eax, [ebp+lpBuffer] push eax call sub_40181F ❸ ; renamed to encodingWrapper add esp, 8 call ds:GetTickCount ❺ mov [ebp+var_4], eax mov ecx, [ebp+var_4] push ecx push offset Format ; "temp%08x" ❹ lea edx, [ebp+FileName] push edx ; Dest call _sprintf add esp, 0Ch lea eax, [ebp+FileName] ❻ push eax ; lpFileName mov ecx, [ebp+nNumberOfBytesToWrite] push ecx ; nNumberOfBytesToWrite mov edx, [ebp+lpBuffer] push edx ; lpBuffer call writeBufferToFile ❶

Working from the start of Example C-102, we see two function calls

to sub_401070 at ❷

and sub_40181F at ❸

that both use the buffer and length as arguments. The format string "temp%08x" at ❹ combined with the result of

GetTickCount at ❺

reveals the source of the filename, which is the current time printed in hexadecimal. IDA Pro has

labeled the filename, as indicated at ❻. From the code

in Example C-102, a good hypothesis is that sub_401070 at ❷ is used to fetch some content

(let’s call it getContent), and that sub_40181F at ❸ is used to

encrypt the contents (which we’ll rename encodingWrapper).

Looking first at our hypothesized encoding function encodingWrapper (at 0x0040181F), we see that it is merely a wrapper for heavy_xor. This confirms that the functions depicted in Figure C-48 are our encoding functions. The function encodingWrapper sets up four arguments for the encoding: a local variable

that is cleared before use, two pointers both pointing to the same buffer that is passed in from

doStuffAndWriteFile, and a buffer size that is also passed in

from doStuffAndWriteFile. The two pointers pointing to the same

buffer suggest that the encoding function takes source and destination buffers along with a

length, and that, in this case, the encoding is performed in place.

Next, we identify the source of the content that is encoded and written to disk. As we

mentioned earlier, the function getContent (at 0x00401070)

appears to acquire some content. Looking at getContent, we see a

single block of code with numerous system functions, as shown in Example C-103.

Example C-103. Windows API functions called in getContent (sub_401070)

GetSystemMetricsGetDesktopWindowGetDC CreateCompatibleDC CreateCompatibleBitmap SelectObjectBitBltGetObjectA GlobalAlloc GlobalLockGetDIBits_memcpy GlobalUnlock GlobalFree ReleaseDC DeleteDC DeleteObject

Based on this list, it is a good guess that this function is trying to capture the screen.

Notably, GetDesktopWindow (bolded) gets a handle to the desktop

window that covers the entire screen, and the functions BitBlt

and GetDIBits (also bolded) are related to retrieving bitmap

information and copying it to a buffer.

We conclude that the malware repeatedly takes snapshots of the user’s desktop and writes an encrypted version of the screen capture to a file.

In order to verify our conclusion, we can take one of the captured files, run it back through the encryption algorithm, and retrieve the originally captured image. (This assumes that the algorithm is a stream cipher and that encryption is reversible; that is, encryption and decryption do the same thing). Since we have few clues about the algorithm used, the easiest way to implement this is to use instrumentation and let the code perform the decoding for us.

Since the code already has instructions that take a buffer, encrypt it, and then write it to a file, we’ll reuse them as follows:

Let the program run as normal until just before encryption.

Replace the buffer holding the screen capture with a buffer holding a previously saved file that we wish to decrypt.

Let the program write the output to the temporary filename based on the current time.

Break the program after the first file is written.

We can implement this strategy manually using OllyDbg or use a script-based approach to provide more flexibility. We’ll look at the manual approach first.

We can implement the instrumentation strategy using OllyDbg by identifying two key

breakpoints. The first will be just before encoding, so we can use 0x00401880 as the breakpoint,

where the call to encodingWrapper occurs (❸ in Example C-102). The second

breakpoint will be after the first file is written, so we set it at 0x0040190A.

After starting the malware with OllyDbg, setting the breakpoints, and running the program, the malware will stop at the first breakpoint (0x00401880). At this point, the arguments on the stack represent the buffer to be encrypted and its length.

Right-click the top value on the stack in the stack pane (the value located at ESP) and select Follow in Dump. Next, open one of the encrypted files that the malware created in WinHex and select Edit ▸ Copy All ▸ Hex Values. Then, in OllyDbg, select the values from the top of the dump pane to the end of the memory block (OllyDbg requires the entire target area to be selected before allowing you to paste content). This selection represents the buffer that is about to be encoded, which we will now fill with the contents of the file. (Don’t worry if the memory block is longer than the buffer size; OllyDbg will paste the content only up to the length of the file.)

Now right-click the Hex dump portion of the dump pane and

select Binary ▸ Binary Paste. (If you’re using an

editor that allows you to copy binary values directly, paste into the ASCII portion of the dump pane instead.) With the buffer prepared, run OllyDbg until the

final breakpoint, and then check the malware’s directory for a new file with the same naming

convention as the previously created ones. Give this file a .bmp extension and

open it. You should see a screenshot that was taken while the malware was running.

Note

Ensure that the file size is the same as that of the second argument passed to the encryption function. If you didn’t change the screen resolution between the initial malware run and this decryption run, the sizes should be the same. If the file size is larger than the memory buffer, this technique may fail.

In order to implement the instrumentation strategy more generically (in a way that does not depend on available buffer sizes), we use the Python-based debugger API in Immunity Debugger (ImmDbg), as discussed in Scriptable Debugging, as well as in Chapter 13. We create the Python script shown in Example C-104 by saving the file with a .py extension in the PyScripts folder under the ImmDbg installation directory.

Note

Customize the example filename (C:\\temp062da212) opened and

assigned to cfile at ❶ in Example C-104 based on your

environment.

Example C-104. ImmDbg decryption script

#!/usr/bin/env python

import immlib

def main():

imm = immlib.Debugger()

imm.setBreakpoint(0x00401875) # break just before pushing args for encoding

imm.Run() # Execute until breakpoint before crypto

cfile = open("C:\\temp062da212",'rb') ❶

buffer = cfile.read() # Read encrypted file into buffer

sz = len (buffer)

membuf = imm.remoteVirtualAlloc(sz) ❷ # Allocate memory within debugger process

imm.writeMemory(membuf,buffer)

regs = imm.getRegs()

imm.writeLong(regs['EBP']-12, membuf) ❸ # Set stack variables

imm.writeLong(regs['EBP']-8, sz)

imm.setBreakpoint(0x0040190A) # after single loop

imm.Run()As you can see in Example C-104, the first breakpoint stops

execution just before the arguments are pushed on the stack. The open call at ❶ opens the encrypted file that

has already been written to the filesystem. The next few lines read the file into memory and

calculate the size of the buffer. The remoteVirtualAlloc call at

❷ is used to create an appropriately sized buffer in the

memory of the running process, and writeMemory is used to copy

the file contents into that new buffer. The two writeLong calls

at ❸ replace the stack variables for the buffer to be

encrypted and its size. The next few instructions push those variables onto the stack to be used for

the following encryption routine and the writing of the file.

Open the malware in ImmDbg, choose ImmLib ▸ Run Python Script, and then select the script that has been created. The script should run, and the debugger should halt at the second breakpoint. At this point, the malware should have written a single file in its own directory. Navigate to the malware’s directory and identify the most recently written file. Change the extension of this file to .bmp and open it. You should see the decrypted screenshot that was taken earlier by the malware.