The most popular covert launching technique is process injection. As the name implies, this technique injects code into another running process, and that process unwittingly executes the malicious code. Malware authors use process injection in an attempt to conceal the malicious behavior of their code, and sometimes they use this to try to bypass host-based firewalls and other process-specific security mechanisms.

Certain Windows API calls are commonly used for process injection. For example, the VirtualAllocEx function can be used to allocate space in an external

process’s memory, and WriteProcessMemory can be used to

write data to that allocated space. This pair of functions is essential to the first three loading

techniques that we’ll discuss in this chapter.

DLL injection—a form of process injection where a remote process is

forced to load a malicious DLL—is the most commonly used covert loading technique. DLL

injection works by injecting code into a remote process that calls LoadLibrary, thereby forcing a DLL to be loaded in the context of that process. Once the

compromised process loads the malicious DLL, the OS automatically calls the DLL’s DllMain function, which is defined by the author of the DLL. This function

contains the malicious code and has as much access to the system as the process in which it is

running. Malicious DLLs often have little content other than the Dllmain function, and everything they do will appear to originate from the compromised

process.

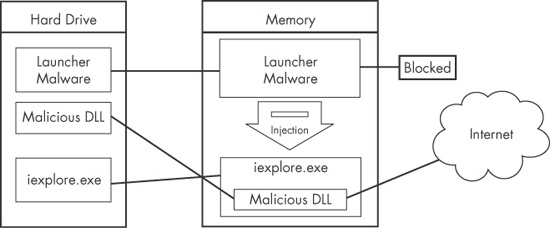

Figure 12-1 shows an example of DLL injection. In this example, the launcher malware injects its DLL into Internet Explorer’s memory, thereby giving the injected DLL the same access to the Internet as Internet Explorer. The loader malware had been unable to access the Internet prior to injection because a process-specific firewall detected it and blocked it.

Figure 12-1. DLL injection—the launcher malware cannot access the Internet until it injects into iexplore.exe.

In order to inject the malicious DLL into a host program, the launcher malware must

first obtain a handle to the victim process. The most common way is to use the Windows API calls

CreateToolhelp32Snapshot, Process32First, and Process32Next to search the

process list for the injection target. Once the target is found, the launcher retrieves the process

identifier (PID) of the target process and then uses it to obtain the handle via a call to OpenProcess.

The function CreateRemoteThread is commonly used for DLL

injection to allow the launcher malware to create and execute a new thread in a remote process. When

CreateRemoteThread is used, it is passed three important

parameters: the process handle (hProcess) obtained with OpenProcess, along with the starting point of the injected thread

(lpStartAddress) and an argument for that thread (lpParameter). For example, the starting point might be set to LoadLibrary and the malicious DLL name passed as the argument. This will

trigger LoadLibrary to be run in the victim process with a

parameter of the malicious DLL, thereby causing that DLL to be loaded in the victim process

(assuming that LoadLibrary is available in the victim

process’s memory space and that the malicious library name string exists within that same

space).

Malware authors generally use VirtualAllocEx to create

space for the malicious library name string. The VirtualAllocEx

function allocates space in a remote process if a handle to that process is provided.

The last setup function required before CreateRemoteThread

can be called is WriteProcessMemory. This function writes the

malicious library name string into the memory space that was allocated with VirtualAllocEx.

Example 12-1 contains C pseudocode for performing DLL injection.

Example 12-1. C Pseudocode for DLL injection

hVictimProcess = OpenProcess(PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, 0, victimProcessID ❶); pNameInVictimProcess = VirtualAllocEx(hVictimProcess,...,sizeof(maliciousLibraryName),...,...); WriteProcessMemory(hVictimProcess,...,maliciousLibraryName, sizeof(maliciousLibraryName),...); GetModuleHandle("Kernel32.dll"); GetProcAddress(...,"LoadLibraryA"); ❷ CreateRemoteThread(hVictimProcess,...,...,LoadLibraryAddress,pNameInVictimProcess,...,...);

This listing assumes that we obtain the victim PID in victimProcessID when it is passed to OpenProcess at

❶ in order to get the handle to the victim process.

Using the handle, VirtualAllocEx and WriteProcessMemory then allocate space and write the name of the malicious DLL into the

victim process. Next, GetProcAddress is used to get the address

to LoadLibrary.

Finally, at ❷, CreateRemoteThread is passed the three important parameters discussed earlier: the handle

to the victim process, the address of LoadLibrary, and a pointer

to the malicious DLL name in the victim process. The easiest way to identify DLL injection is by

identifying this trademark pattern of Windows API calls when looking at the launcher malware’s

disassembly.

In DLL injection, the malware launcher never calls a malicious function. As stated earlier,

the malicious code is located in DllMain, which is automatically

called by the OS when the DLL is loaded into memory. The DLL injection launcher’s goal is to

call CreateRemoteThread in order to create the remote thread

LoadLibrary, with the parameter of the malicious DLL being

injected.

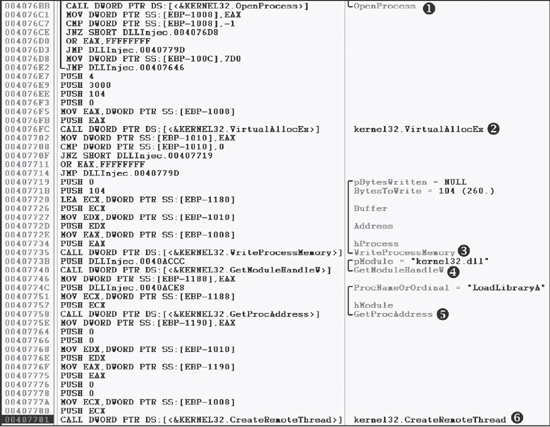

Figure 12-2 shows DLL injection code as seen through a debugger. The six function calls from our pseudocode in Example 12-1 can be seen in the disassembly, labeled ❶ through ❻.

Once you find DLL injection activity in disassembly, you should start looking for the strings

containing the names of the malicious DLL and the victim process. In the case of Figure 12-2, we don’t see those strings, but they must be accessed

before this code executes. The victim process name can often be found in a strncmp function (or equivalent) when the launcher determines the victim process’s PID. To find the malicious DLL name, we could set

a breakpoint at 0x407735 and dump the contents of the stack to reveal the value of Buffer as it is being passed to WriteProcessMemory.

Once you’re able to recognize the DLL injection code pattern and identify these important strings, you should be able to quickly analyze an entire group of malware launchers.

Like DLL injection, direct injection involves allocating and inserting code into the memory space of a remote process. Direct injection uses many of the same Windows API calls as DLL injection. The difference is that instead of writing a separate DLL and forcing the remote process to load it, direct-injection malware injects the malicious code directly into the remote process.

Direct injection is more flexible than DLL injection, but it requires a lot of customized code in order to run successfully without negatively impacting the host process. This technique can be used to inject compiled code, but more often, it’s used to inject shellcode.

Three functions are commonly found in cases of direct injection: VirtualAllocEx, WriteProcessMemory, and CreateRemoteThread. There will typically be two calls to VirtualAllocEx and WriteProcessMemory.

The first will allocate and write the data used by the remote thread, and the second will allocate

and write the remote thread code. The call to CreateRemoteThread

will contain the location of the remote thread code (lpStartAddress) and the data (lpParameter).

Since the data and functions used by the remote thread must exist in the victim process,

normal compilation procedures will not work. For example, strings are not in the normal .data section, and LoadLibrary/GetProcAddress will need to be called to access functions that are not

already loaded. There are other restrictions, which we won’t go into here. Basically, direct

injection requires that authors either be skilled assembly language coders or that they will inject

only relatively simple shellcode.

In order to analyze the remote thread’s code, you may need to debug the malware and dump

all memory buffers that occur before calls to WriteProcessMemory

to be analyzed in a disassembler. Since these buffers most often contain shellcode, you will need

shellcode analysis skills, which we discuss extensively in Chapter 19.