To install the malware as a service, run the malware’s exported

installAfunction via rundll32.exe withrundll32.exe Lab03-02.dll,installA.To run the malware, start the service it installs using the net command

net start IPRIP.Use Process Explorer to determine which process is running the service. Since the malware will be running within one of the svchost.exe files on the system, hover over each one until you see the service name, or search for Lab03-02.dll using the Find DLL feature of Process Explorer.

In procmon you can filter on the PID you found using Process Explorer.

By default, the malware installs as the service

IPRIPwith a display name ofIntranet Network Awareness (INA+)and description of “Depends INA+, Collects and stores network configuration and location information, and notifies applications when this information changes.” It installs itself for persistence in the registry atHKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\IPRIP\Parameters\ServiceDll: %CurrentDirectory%\Lab03-02.dll. If you rename Lab03-02.dll to something else, such as malware.dll, then it writes malware.dll into the registry key, instead of using the name Lab03-02.dll.The malware resolves the domain name practicalmalwareanalysis.com and connects to that host over port 80 using what appears to be HTTP. It does a

GETrequest for serve.html and uses the User-Agent%ComputerName% Windows XP 6.11.

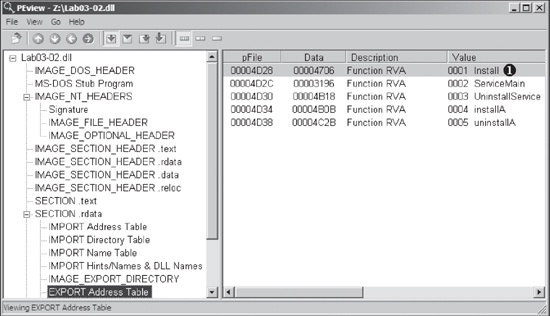

We begin with basic static analysis by looking at the PE file structure and strings. Figure C-5 shows that this DLL has five exports, as listed from

❶ and below. The export ServiceMain suggests that this malware needs to be installed as a service in order to run

properly.

The following listing shows the malware’s interesting imported functions in bold.

OpenService DeleteService OpenSCManager CreateService RegOpenKeyEx RegQueryValueEx RegCreateKey RegSetValueEx InternetOpen InternetConnect HttpOpenRequest HttpSendRequest InternetReadFile

These include service-manipulation functions, such as CreateService, and registry-manipulation functions, such as RegSetValueEx. Imported networking functions, such as HttpSendRequest, suggest that the malware uses HTTP.

Next, we examine the strings, as shown in the following listing.

Y29ubmVjdA== practicalmalwareanalysis.com serve.html dW5zdXBwb3J0 c2xlZXA= Y21k cXVpdA== Windows XP 6.11 HTTP/1.1 quit exit getfile cmd.exe /c Depends INA+, Collects and stores network configuration and location information, and notifies applications when this information changes. %SystemRoot%\System32\svchost.exe -k SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\ Intranet Network Awareness (INA+) %SystemRoot%\System32\svchost.exe -k netsvcs netsvcs SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Svchost IPRIP

We see several interesting strings, including registry locations, a domain name, unique

strings like IPRIP and serve.html, and a variety of encoded strings. Basic dynamic techniques may show us how

these strings and imports are used.

The results of our basic static analysis techniques lead us to believe that this malware needs

to be installed as a service using the exported function installA. We’ll use that function to attempt to install this malware, but before we

do that, we’ll launch Regshot to take a baseline snapshot of the registry and use Process

Explorer to monitor the processes running on the system. After setting up Regshot and Process

Explorer, we install the malware using rundll32.exe, as follows:

C:\>rundll32.exe Lab03-02.dll,installAAfter installing the malware, we use Process Explorer to confirm that it has terminated by making sure that rundll32.exe is no longer in the process listing. Next, we take a second snapshot with Regshot to see if the malware installed itself in the registry.

The edited Regshot results are shown in the following listing.

---------------------------------- Keys added ---------------------------------- HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\IPRIP ❶ ---------------------------------- Values added ---------------------------------- HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\IPRIP\Parameters\ServiceDll: "z:\Lab03-02.dll" HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\IPRIP\ImagePath: "%SystemRoot%\System32\svchost.exe -k netsvcs" ❷ HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\IPRIP\DisplayName: "Intranet Network Awareness (INA+)" ❸ HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\IPRIP\Description: "Depends INA+, Collects and stores network configuration and location information, and notifies applications when this information changes." ❹

The Keys added section shows that the malware installed

itself as the service IPRIP at ❶. Since the malware is a DLL, it depends on an executable to launch it. In fact, we see

at ❷ that the ImagePath is set to svchost.exe, which means that the

malware will be launched inside an svchost.exe process. The rest of the

information, such as the DisplayName and Description at ❸ and ❹, creates a unique fingerprint that can be used to identify the

malicious service.

If we examine the strings closely, we see SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows

NT\CurrentVersion\SvcHost and a message "You specify service name not in Svchost//netsvcs, must be one of following". If we follow our hunch and examine the \SvcHost\netsvcs registry key, we can see other potential service names we

might use, like 6to4

AppMgmt. Running Lab03-02.dll,installA

6to4 will install this malware under the 6to4 service

instead of the IPRIP service, as in the previous listing.

After installing the malware as a service, we could launch it, but first we’ll set up the rest of our basic dynamic tools. We run procmon (after clearing out all events); start Process Explorer; and set up a virtual network, including ApateDNS and Netcat listening on port 80 (since we see HTTP in the strings listing).

Since this malware is installed as the IPRIP service, we

can start it using the net command in Windows, as follows:

c:\>net start IPRIP

The Intranet Network Awareness (INA+) service is starting.

The Intranet Network Awareness (INA+) service was started successfully.The fact that the display name (INA+) matches the

information found in the registry tells us that our malicious service has started.

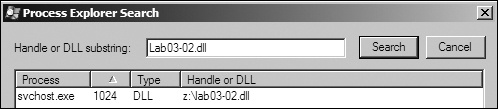

Next, we open Process Explorer and attempt to find the process in which the malware is running by selecting Find ▸ Find Handle or DLL to open the dialog shown in Figure C-6. We enter Lab03-02.dll and click Search. As shown in the figure, the result tells us that Lab03-02.dll is loaded by svchost.exe with the PID 1024. (The specific PID may differ on your system.)

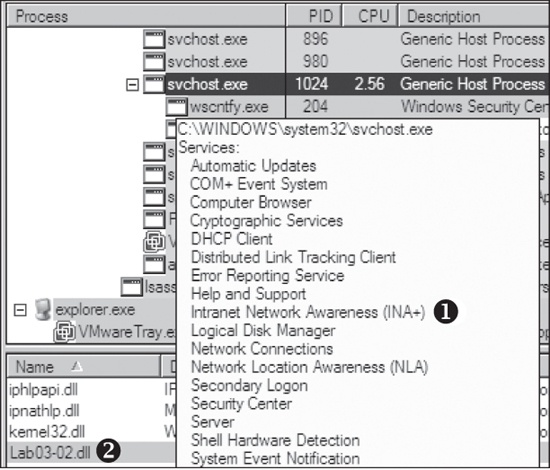

In Process Explorer, we select View ▸ Lower Pane View ▸

DLLs and choose the svchost.exe running with PID 1024. Figure C-7 shows the result. The display name Intranet Network Awareness (INA+) shown at ❶ confirms that the malware is running in

svchost.exe, which is further confirmed when we see at ❷ that Lab03-02.dll is loaded.

Next, we turn our attention to our network analysis tools. First, we check ApateDNS to see if the malware performed any DNS requests. The output shows a request for practicalmalwareanalysis.com, which matches the strings listing shown earlier.

Note

It takes 60 seconds after starting the service to see any network traffic (the

program does a Sleep(60000) before attempting network access). If

the networking connection fails for any reason (for example, you forgot to set up ApateDNS), it

waits 10 minutes before attempting to connect again.

We complete our network analysis by examining the Netcat results, as follows:

c:\>nc -l -p 80 GET /serve.html HTTP/1.1 Accept: */* User-Agent: MalwareAnalysis2 Windows XP 6.11 Host: practicalmalwareanalysis.com

We see that the malware performs an HTTP GET request over

port 80 (we were listening over port 80 with Netcat since we saw HTTP in the string listing). We run

this test several times, and the data appears to be consistent across runs.

We can create a couple of network signatures from this data. Because the malware consistently

does a GET request for serve.html, we can

use that GET request as a network signature. The malware also

uses the User-Agent MalwareAnalysis2 Windows XP 6.11.

MalwareAnalysis2 is our malware analysis virtual machine’s name (so this portion of

the User-Agent will be different on your machine). The second part of the User-Agent (Windows XP 6.11) is consistent and can be used as a network

signature.