Malware often goes to great lengths to hide its running processes and persistence mechanisms from users. The most common tool used to hide malicious activity is referred to as a rootkit.

Rootkits can come in many forms, but most of them work by modifying the internal functionality of the OS. These modifications cause files, processes, network connections, or other resources to be invisible to other programs, which makes it difficult for antivirus products, administrators, and security analysts to discover malicious activity.

Some rootkits modify user-space applications, but the majority modify the kernel, since protection mechanisms, such as intrusion prevention systems, are installed and running at the kernel level. Both the rootkit and the defensive mechanisms are more effective when they run at the kernel level, rather than at the user level. At the kernel level, rootkits can corrupt the system more easily than at the user level. The kernel-mode technique of SSDT hooking and IRP hooks were discussed in Chapter 10.

Here we’ll introduce you to a couple of user-space rootkit techniques, to give you a general understanding of how they work and how to recognize them in the field. (There are entire books devoted to rootkits, and we’ll only scratch the surface in this section.)

A good strategy for dealing with rootkits that install hooks at the user level is to first determine how the hook is placed, and then figure out what the hook is doing. Now we will look at the IAT and inline hooking techniques.

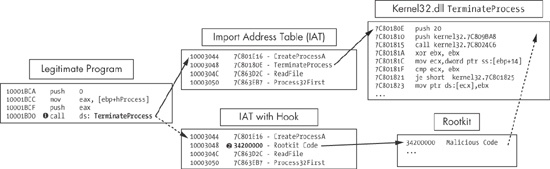

IAT hooking is a classic user-space rootkit method that hides files, processes, or network

connections on the local system. This hooking method modifies the import address table (IAT) or the

export address table (EAT). An example of IAT hooking is shown in Figure 11-4. A legitimate program calls the TerminateProcess function, as seen at ❶. Normally, the code will use the IAT to access the target function in

Kernel32.dll, but if an IAT hook is installed, as indicated at ❷, the malicious rootkit code will be called instead. The rootkit

code returns to the legitimate program to allow the TerminateProcess function to execute after manipulating some parameters. In this example,

the IAT hook prevents the legitimate program from terminating a process.

Figure 11-4. IAT hooking of TerminateProcess. The top path is the

normal flow, and the bottom path is the flow with a rootkit.

The IAT technique is an old and easily detectable form of hooking, so many modern rootkits use the more advanced inline hooking method instead.

Inline hooking overwrites the API function code contained in the imported DLLs, so it must wait until the DLL is loaded to begin executing. IAT hooking simply modifies the pointers, but inline hooking changes the actual function code.

A malicious rootkit performing inline hooking will often replace the start of the code with a jump that takes the execution to malicious code inserted by the rootkit. Alternatively, the rootkit can alter the code of the function to damage or change it, rather than jumping to malicious code.

An example of the inline hooking of the ZwDeviceIoControlFile function is shown in Example 11-7. This

function is used by programs like Netstat to retrieve network information from the system.

Example 11-7. Inline hooking example

100014B4 mov edi, offset ProcName; "ZwDeviceIoControlFile"

100014B9 mov esi, offset ntdll ; "ntdll.dll"

100014BE push edi ; lpProcName

100014BF push esi ; lpLibFileName

100014C0 call ds:LoadLibraryA

100014C6 push eax ; hModule

100014C7 call ds:GetProcAddress ❶

100014CD test eax, eax

100014CF mov Ptr_ZwDeviceIoControlFile, eaxThe location of the function being hooked is acquired at ❶. This rootkit’s goal is to install a 7-byte inline hook at the start of the

ZwDeviceIoControlFile function in memory. Table 11-2 shows how the hook was initialized; the raw bytes are shown on

the left, and the assembly is shown on the right.

The assembly starts with the opcode 0xB8 (mov imm/r), followed by four zero bytes, and then the opcodes 0xFF

0xE0 (jmp eax). The rootkit

will fill in these zero bytes with an address before it installs the hook, so that the jmp instruction will be valid. You can activate this view by pressing the

C key on the keyboard in IDA Pro.

The rootkit uses a simple memcpy to patch the zero bytes to

include the address of its hooking function, which hides traffic destined for port 443. Notice that

the address given (10004011) matches the address of the zero

bytes in the previous example.

100014D9 push 4 100014DB push eax 100014DC push offset unk_10004011100014E1 mov eax, offset hooking_function_hide_Port_443 100014E8 callmemcpy

The patch bytes (10004010) and the hook location are then

sent to a function that installs the inline hook, as shown in Example 11-8.

Example 11-8. Installing an inline hook

100014ED push 7

100014EF push offset Ptr_ZwDeviceIoControlFile

100014F4 push offset 10004010 ;patchBytes

100014F9 push edi

100014FA push esi

100014FB call Install_inline_hookNow ZwDeviceIoControlFile will call the rootkit function

first. The rootkit’s hooking function removes all traffic destined for port 443 and then calls

the real ZwDeviceIoControlFile, so everything continues to

operate as it did before the hook was installed.

Since many defense programs expect inline hooks to be installed at the beginning of functions,

some malware authors have attempted to insert the jmp or the code

modification further into the API code to make it harder to find.