The malware extracts and drops the file msgina32.dll onto disk from a resource section named

TGAD.The malware installs msgina32.dll as a GINA DLL by adding it to the registry location

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Winlogon\GinaDLL, which causes the DLL to be loaded after system reboot.The malware steals user credentials by performing GINA interception. The msgina32.dll file is able to intercept all user credentials submitted to the system for authentication.

The malware logs stolen credentials to %SystemRoot%\System32\msutil32.sys. The username, domain, and password are logged to the file with a timestamp.

Once the malware is dropped and installed, there must be a system reboot for the GINA interception to begin. The malware logs credentials only when the user logs out, so log out and back in to see your credentials in the log file.

Beginning with basic static analysis, we see the strings GinaDLL and SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows

NT\CurrentVersion\Winlogon, which lead us to suspect that this might be GINA interception

malware. Examining the imports, we see functions for manipulating the registry and extracting a

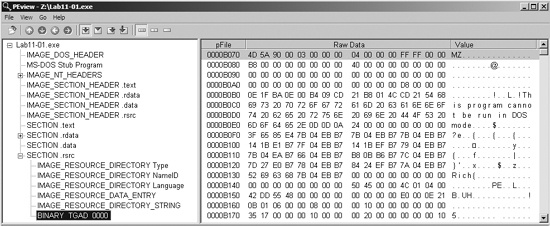

resource section. Because we see resource extraction import functions, we examine the file structure

by loading Lab11-01.exe into PEview, as shown in Figure C-35.

Examining the PE file format, we see a resource section named TGAD. When we click that section in PEview, we see that TGAD contains an embedded PE file.

Next, we perform dynamic analysis and monitor the malware with procmon by setting a filter for

Lab11-01.exe. When we launch the malware, we see that it creates a file named

msgina32.dll on disk in the same directory from which the malware was launched.

The malware inserts the path to msgina32.dll into the registry key HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Winlogon\GinaDLL, so

that the DLL will be loaded by Winlogon when the system reboots.

Extracting the TGAD resource section from

Lab11-01.exe (using Resource Hacker) and comparing it to

msgina32.dll, we find that the two are identical.

Next, we load Lab11-01.exe into IDA Pro to confirm our findings. We see

that the main function calls two functions: sub_401080 (extracts the TGAD resource

section to msgina32.dll) and sub_401000

(sets the GINA registry value). We conclude that Lab11-01.exe is an installer

for msgina32.dll, which is loaded by Winlogon during system startup.

We’ll begin our analysis of msgina32.dll by looking at the Strings output, as shown in Example C-43.

Example C-43. Strings output of msgina32.dll

GinaDLL

Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Winlogon

MSGina.dll

UN %s DM %s PW %s OLD %s ❶

msutil32.sysThe strings in this listing contain what appears to be a log message at ❶, which could be used to log user credentials if this is GINA

interception malware. The string msutil32.sys is interesting, and

we will determine its significance later in the lab.

Examining msgina32.dll’s exports, we see many functions that begin

with the prefix Wlx. Recall from Chapter 11 that GINA interception malware must contain all of these DLL exports because they are required by

GINA. We’ll analyze each of these functions in IDA Pro.

We begin by loading the malware into IDA Pro and analyzing DllMain, as shown in Example C-44.

Example C-44. DllMain of msgina32.dll getting a

handle to msgina.dll

1000105A cmp eax, DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH ❶ 1000105D jnz short loc_100010B7 ... 1000107E call ds:GetSystemDirectoryW ❷ 10001084 lea ecx, [esp+20Ch+LibFileName] 10001088 push offset String2 ; "\\MSGina" 1000108D push ecx ; lpString1 1000108E call ds:lstrcatW 10001094 lea edx, [esp+20Ch+LibFileName] 10001098 push edx ; lpLibFileName 10001099 call ds:LoadLibraryW ❸ 1000109F xor ecx, ecx 100010A1 mov hModule, eax ❹

As shown in the Example C-44, DllMain first checks the fdwReason

argument at ❶. This is an argument passed in to indicate

why the DLL entry-point function is being called. The malware checks for DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH, which is called when a process is starting up or when LoadLibrary is used to load the DLL. If this particular DllMain is called during a DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH, the code beginning at ❷

is called. This code gets a handle to msgina.dll in the Windows system

directory via the call to LoadLibraryW at ❸.

Note

msgina.dll is the Windows DLL that implements GINA, whereas msgina32.dll is the malware author’s GINA interception DLL. The name msgina32 is designed to deceive.

The malware saves the handle in a global variable that IDA Pro has named hModule at ❹. The use of this

variable allows the DLL’s exports to properly call functions in the

msgina.dll Windows DLL. Since msgina32.dll is intercepting

communication between Winlogon and msgina.dll, it must properly call the

functions in msgina.dll so that the system will continue to operate

normally.

Next, we analyze each export function. We begin with WlxLoggedOnSAS, as shown in Example C-45.

Example C-45. WlxLoggedOnSAS export just passing through to

msgina.dll

10001350 WlxLoggedOnSAS proc near

10001350 push offset aWlxloggedons_0 ; "WlxLoggedOnSAS"

10001355 call sub_10001000

1000135A jmp eax ❶The WlxLoggedOnSAS export is short and simply passes

through to the true WlxLoggedOnSAS contained in

msgina.dll. There are now two WlxLoggedOnSAS

functions: the version in Example C-45 in

msgina32.dll and the original in msgina.dll. The function

in Example C-45 begins by passing the string WlxLoggedOnSAS to sub_10001000 and then

jumps to the result. The sub_10001000 function uses the hModule handle (to msgina.dll) and the string passed

in (in this case, WlxLoggedOnSAS) to use GetProcAddress to resolve a function in msgina.dll. The malware

doesn’t call the function; it simply resolves the address of WlxLoggedOnSAS in msgina.dll and jumps to the function, as seen at

❶. By jumping and not calling WlxLoggedOnSAS, this code will not set up a stack frame or push a return address onto the

stack. When WlxLoggedOnSAS in msgina.dll is

called, it will return execution directly to Winlogon because the return address on the stack is the

same as what was on the stack when the code in Example C-45 is called.

If we continue analyzing the other exports, we see that most operate like WlxLoggedOnSAS (they are pass-through functions), except for WlxLoggedOutSAS, which contains some extra code. (WlxLoggedOutSAS is called when the user logs out of the system.)

The export begins by resolving WlxLoggedOutSAS within

msgina.dll using GetProcAddress and then

calling it. The export also contains the code shown in Example C-46.

Example C-46. WlxLoggedOutSAS calling the credential logging function

sub_10001570

100014FC push offset aUnSDmSPwSOldS ❶ ; "UN %s DM %s PW %s OLD %s" 10001501 push 0 ; dwMessageId 10001503 call sub_10001570 ❷

The code in Example C-46 passes a bunch of

arguments and a format string at ❶. This string is

passed to sub_10001570, which is called at ❷.

It seems like sub_10001570 may be the logging

function for stolen credentials, so let’s examine it to see what it does. Example C-47 shows the logging code contained in sub_10001570.

Example C-47. The credential-logging function logging to msutil32.sys

1000158E call _vsnwprintf ❶ 10001593 push offset Mode ; Mode 10001598 push offset Filename ; "msutil32.sys" 1000159D call _wfopen ❷ 100015A2 mov esi, eax 100015A4 add esp, 18h 100015A7 test esi, esi 100015A9 jz loc_1000164F 100015AF lea eax, [esp+858h+Dest] 100015B3 push edi 100015B4 lea ecx, [esp+85Ch+Buffer] 100015B8 push eax 100015B9 push ecx ; Buffer 100015BA call _wstrtime ❸ 100015BF add esp, 4 100015C2 lea edx, [esp+860h+var_828] 100015C6 push eax 100015C7 push edx ; Buffer 100015C8 call _wstrdate ❹ 100015CD add esp, 4 100015D0 push eax 100015D1 push offset Format ; "%s %s - %s " 100015D6 push esi ; File 100015D7 call fwprintf ❺

The call to vsnwprintf at ❶ fills in the format string passed in by the WlxLoggedOutSAS export. Next, the malware opens the file

msutil32.sys at ❷, which is created

inside C:\Windows\System32\ since that is where Winlogon resides (and

msgina32.dll is running in the Winlogon process). At ❸ and ❹, the date and

time are recorded, and the information is logged at ❺.

You should now realize that msutil32.sys is used to store logged credentials

and that it is not a driver, although its name suggests that it is.

We force the malware to log credentials by running Lab11-01.exe, rebooting the machine, and then logging in and out of the system. The following is an example of the data contained in a log file created by this malware:

09/10/11 15:00:04 - UN user DM MALWAREVM PW test123 OLD (null) 09/10/11 23:09:44 - UN hacker DM MALWAREVM PW p@ssword OLD (null)

The usernames are user and hacker, their passwords are test123 and p@ssword, and the domain is MALWAREVM.

Lab 11-1 Solutions is a GINA interceptor installer. The malware drops a DLL on the system and installs it to steal user credentials, beginning after system reboot. Once the GINA interceptor DLL is installed and running, it logs credentials to msutil32.sys when a user logs out of the system.