The user-space program loads the driver and then pops up an advertisement every 30 seconds. The driver hides the process by unlinking the Process Environment Block (PEB) from the system’s linked list.

Once this program is running, there is no easy way to stop it without rebooting.

The kernel component responds to any

DeviceIoControlrequest by unlinking the process that made the request from the linked list of processes in order to hide the process from the user.

We begin with some basic static analysis on the files. When we analyze the driver file, we see the following imports:

IofCompleteRequest

IoDeleteDevice

IoDeleteSymbolicLink

RtlInitUnicodeString

IoGetCurrentProcess

IoCreateSymbolicLink

IoCreateDevice

KeTickCountThe import for IoGetCurrentProcess is the only one that

provides much information. (The other imports are simply required by any driver that creates a

device that is accessible from user space.) The call to IoGetCurrentProcess tells us that this driver either modifies the running process or

requires information about it.

Next, we copy the driver file into C:\Windows\System32 and double-click the executable to run it. We see a pop-up ad, which is the same as the one in Lab 7-2 Solutions. We now examine what it did to our system. First, we check to see if the service was successfully installed and verify that the malicious .sys file is used as part of the service. Simultaneously, we notice that after about 30 seconds, the program pops up the advertisement again and does so about once every 30 seconds. Opening Task Manager in an effort to terminate the program, we see that the program isn’t listed. And it’s not listed in Process Explorer either.

The program continues to open advertisements, and there’s no easy way to stop it. It’s not in a process listing, so we can’t stop it by killing the process. Nor can we attach a debugger to the process because the program doesn’t show up in the process listing for WinDbg or OllyDbg. At this point, our only choice is to revert to our most recent snapshot or reboot and hope that the program isn’t persistent. It’s not, so a reboot stops it.

Now to IDA Pro. Navigating to WinMain and examining the

functions it calls, we see the following:

OpenSCManager CreateService StartService CloseServiceHandle CreateFile DeviceIoControl OleInitialize CoCreateInstance VariantInit SysAllocString ecx+0x2c Sleep OleUninitialize

WinMain can be logically broken into two sections. The

first section, consisting of OpenSCManager through DeviceIoControl, includes the functions to load and send a request to the

kernel driver. The second section consists of the remaining functions, which show the usage of a COM

object. At this point, we don’t know the target of the call to ecx+0x2c, but we’ll come back to that later.

Looking at the calls in detail, we see that the program creates a service called Process Helper, which loads the kernel driver C:\Windows\System32\Lab10-03.sys. It then starts the Process Helper service, which loads Lab10-03.sys into the kernel and opens a handle to \\.\ProcHelper, which opens a handle to the kernel device created by the ProcHelper driver.

We need to look carefully at the call to DeviceIoControl,

shown in Example C-35, because the input and output

parameters passed as arguments to it will be sent to the kernel code, which we will need to analyze

separately.

Example C-35. A call to DeviceIoControl in

Lab10-03.exe to pass a request to the Lab10-03.sys

driver

0040108C lea ecx, [esp+2Ch+BytesReturned] 00401090 push 0 ; lpOverlapped 00401092 push ecx ; lpBytesReturned 00401093 push 0 ; nOutBufferSize 00401095 push ❶0; lpOutBuffer 00401097 push 0 ; nInBufferSize 00401099 push ❷0; lpInBuffer 0040109B push ❸0ABCDEF01h ; dwIoControlCode 004010A0 push eax ; hDevice 004010A1 call ds:DeviceIoControl

Notice that the call to DeviceIoControl has lpOutBuffer at ❶ and lpInBuffer at ❷ set to NULL.

This is unusual, and it means that this request sends no information to the kernel driver and that

the kernel driver sends no information back. Also notice that the dwIoControlCode of 0xABCDEF01 at ❸ is passed

to the kernel driver. We’ll revisit this when we look at the kernel driver.

The remainder of this file is nearly identical to the COM example in Lab 7-2 Solutions, except that the call to the navigate function is inside a loop that runs continuously and sleeps for 30 seconds between each call.

Next, we open the kernel file with IDA Pro. As shown in Example C-36, we see that it calls IoCreateDevice at ❶ to create a device named

\Device\ProcHelper at ❷.

Example C-36. Lab10-03.sys creating a device that is accessible from user space

0001071A ❷push offset aDeviceProchelp ; "\\Device\\ProcHelper" 0001071F lea eax, [ebp+var_C] 00010722 push eax 00010723 call edi ; RtlInitUnicodeString 00010725 mov esi, [ebp+arg_0] 00010728 lea eax, [ebp+var_4] 0001072B push eax 0001072C push 0 0001072E push 100h 00010733 push 22h 00010735 lea eax, [ebp+var_C] 00010738 push eax 00010739 push 0 0001073B push esi 0001073C ❶call ds:IoCreateDevice

As shown in Example C-37, the function then calls

IoCreateSymbolicLink at ❶ to create a symbolic link named \DosDevices\ProcHelper at ❷ for the

user-space program to access.

Example C-37. Lab10-03.sys creating a symbolic link to make it easier for user-space applications to access a handle to the device

00010751 ❷push offset aDosdevicesPr_0 ; "\\DosDevices\\ProcHelper" 00010756 lea eax, [ebp+var_14] 00010759 push eax 0001075A mov dword ptr [esi+70h], offset loc_10666 00010761 mov dword ptr [esi+34h], offset loc_1062A 00010768 call edi ; RtlInitUnicodeString 0001076A lea eax, [ebp+var_C] 0001076D push eax 0001076E lea eax, [ebp+var_14] 00010771 push eax 00010772 ❶call ds:IoCreateSymbolicLink

We can either run the malware or just start the service to load our kernel driver into

memory. We know that the device object is at \Device\ProcHelper,

so we start with it. In order to find the function in ProcHelper

that is executed, we must find the driver object, which can be done with the !devobj command, as shown in Example C-38. The output of !devobj tells us where the DriverObject at ❶ is stored.

Example C-38. Finding the device object for the ProcHelper

driver

kd> !devobj ProcHelper

Device object (82af64d0) is for:

❶ProcHelper \Driver\Process Helper DriverObject 82716a98

Current Irp 00000000 RefCount 1 Type 00000022 Flags 00000040

Dacl e15b15cc DevExt 00000000 DevObjExt 82af6588

ExtensionFlags (0000000000)

Device queue is not busy.The DriverObject contains pointers to all of the functions

that will be called when a user-space program accesses the device object. The DriverObject is stored in a data structure called DRIVER_OBJECT. We can use the dt command to view the

driver object with labels, as shown in Example C-39.

Example C-39. Examining the driver object for Lab10-03.sys using WinDbg

kd>dt nt!_DRIVER_OBJECT 82716a98+0x000 Type : 4 +0x002 Size : 168 +0x004 DeviceObject : 0x82af64d0 _DEVICE_OBJECT +0x008 Flags : 0x12 +0x00c DriverStart : 0xf7c26000 +0x010 DriverSize : 0xe00 +0x014 DriverSection : 0x827bd598 +0x018 DriverExtension : 0x82716b40 _DRIVER_EXTENSION +0x01c DriverName : _UNICODE_STRING "\Driver\Process Helper" +0x024 HardwareDatabase : 0x80670ae0 _UNICODE_STRING "\REGISTRY\MACHINE\ HARDWARE\DESCRIPTION\SYSTEM" +0x028 FastIoDispatch : (null) +0x02cDriverInit: 0xf7c267cd long +0 +0x030 DriverStartIo : (null) +0x034DriverUnload: 0xf7c2662a void +0 +0x038 MajorFunction : [28] 0xf7c26606 long +0

This code contains several function pointers of note. These include DriverInit, the DriverEntry routine we analyzed in IDA

Pro, and DriverUnload, which is called when this driver is

unloaded. When we look at DriverUnload in IDA Pro, we see that it

deletes the symbolic link and the device created by the DriverEntry program.

Next, we examine the major function table, which is often where the most interesting

driver code is implemented. Windows XP allows 0x1C possible major function codes, so we view the

entries in the major function table using the dd command:

kd> dd 82716a98+0x38 L1C

82716ad0 f7c26606 804f354a f7c26606 804f354a

82716ae0 804f354a 804f354a 804f354a 804f354a

82716af0 804f354a 804f354a 804f354a 804f354a

82716b00 804f354a 804f354a f7c26666 804f354a

82716b10 804f354a 804f354a 804f354a 804f354a

82716b20 804f354a 804f354a 804f354a 804f354a

82716b30 804f354a 804f354a 804f354a 804f354aEach entry in the table represents a different type of request that the driver can handle, but as you can see, most of the entries in the table are for the same function at 0X804F354A. All of the entries in the table with the value 0X804F354A represent a request type that the driver does not handle. To verify this, we need to find out what that function does. We could view its disassembly, but because it’s a Windows function, its name should tell us what it does, as shown here:

kd> ln 804f354a (804f354a) nt!IopInvalidDeviceRequest | (804f3580) nt!IopGetDeviceAttachmentBase Exact matches: nt!IopInvalidDeviceRequest = <no type information>

The function at 0X804F354A is named IopInvalidDeviceRequest, which means that it handles invalid requests that this driver

doesn’t handle. The remaining functions from the major function table at offsets 0, 2, and 0xe

contain the functionality that we are interested in. Examining wdm.h, we find

that offsets of 0, 2, and 0xe store the functions for the Create,

Close, and DeviceIoControl

functions.

First, we look at the Create and Close functions at offsets 0 and 2 in the major function table. We notice that both

entries in the major function table point to the same function (0xF7C26606). Looking at that

function, we see that it simply calls IofCompleteRequest and then

returns. This tells the OS that the request was successful, but does nothing else. The only

remaining function in the major function table is the one that handles DeviceIoControl requests, which is the most interesting.

Looking at the DeviceIoControl function, we see that it

manipulates the PEB of the current process. Example C-40 shows the code that handles DeviceIoControl.

Example C-40. The driver code that handles DeviceIoControl

requests

00010666 mov edi, edi 00010668 push ebp 00010669 mov ebp, esp 0001066B call ❶ds:IoGetCurrentProcess 00010671 mov ecx, [eax+8Ch] 00010677 add ❷eax, 88h 0001067C mov edx, [eax] 0001067E mov [ecx], edx 00010680 mov ecx, [eax] 00010682 mov ❸eax, [eax+4] 00010685 mov [ecx+4], eax 00010688 mov ecx, [ebp+Irp] ; Irp 0001068B and dword ptr [ecx+18h], 0 0001068F and dword ptr [ecx+1Ch], 0 00010693 xor dl, dl ; PriorityBoost 00010695 call ds:IofCompleteRequest 0001069B xor eax, eax 0001069D pop ebp 0001069E retn 8

The first thing the DeviceIoControl function does is

call IoGetCurrentProcess at ❶, which returns the EPROCESS structure of the

process that issued the call to DeviceIoControl. The function

then accesses the data at an offset of 0x88 at ❷, and

then accesses the next DWORD at offset 0x8C at ❸.

We use the dt command to discover that LIST_ENTRY is stored at offsets 0x88 and 0x8C in the PEB structure, as

shown in Example C-41 at ❶.

Example C-41. Examining the EPROCESS structure with WinDbg

kd> dt nt!_EPROCESS

+0x000 Pcb : _KPROCESS

+0x06c ProcessLock : _EX_PUSH_LOCK

+0x070 CreateTime : _LARGE_INTEGER

+0x078 ExitTime : _LARGE_INTEGER

+0x080 RundownProtect : _EX_RUNDOWN_REF

+0x084 UniqueProcessId : Ptr32 Void

❶+0x088 ActiveProcessLinks : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x090 QuotaUsage : [3] Uint4B

+0x09c QuotaPeak : [3] Uint4B

...Now that we know that function is accessing the LIST_ENTRY

structure, we look closely at how LIST_ENTRY is being accessed.

The LIST_ENTRY structure is a double-linked list with two values:

the first is BLINK, which points to the previous entry in the

list, and the second is FLINK, which points to the next entry in

the list. We see that it is not only reading the LIST_ENTRY

structure, but also changing structures, as shown in Example C-42.

Example C-42. DeviceIoControl code that modifies the EPROCESS structure

00010671 ❶mov ecx, [eax+8Ch] 00010677 add eax, 88h 0001067C ❷mov edx, [eax] 0001067E ❸mov [ecx], edx 00010680 ❹mov ecx, [eax] 00010682 ❺mov eax, [eax+4] 00010685 ❻mov [ecx+4], eax

The instruction at ❶ obtains a pointer to

the next entry in the list. The instruction at ❷ obtains

a pointer to the previous entry in the list. The instruction at ❸ overwrites the BLINK pointer of the next entry so

that it points to the previous entry. Prior to ❸, the

BLINK pointer of the next entry pointed to the current entry. The

instruction at ❸ overwrites the BLINK pointer so that it skips over the current process. The instructions at ❹, ❺, and ❻ perform the same steps, except to overwrite the FLINK pointer of the previous entry in the list to skip the current

entry.

Rather than change the EPROCESS structure of the current

process, the code in Example C-42 changes the EPROCESS structure of the process in front of it and behind it in the

linked list of processes. These six instructions hide the current process by unlinking it from the

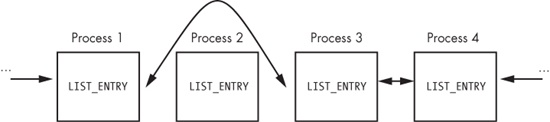

linked list of loaded processes, as shown in Figure C-34.

Figure C-34. A process being removed from the process list so that it’s hidden from tools such as Task Manager

When the OS is running normally, each process has a pointer to the process before and after it. However, in Figure C-34, Process 2 has been hidden by this rootkit. When the OS iterates over the linked list of processes, the hidden process is always skipped.

You might wonder how this process continues to run without any problems, even though it’s not in the OS’s list of processes. To answer this, remember that a process is simply a container for various threads to run inside. The threads are scheduled to execute on the CPU. As long as the threads are still properly accounted for by the OS, they will be scheduled, and the process will continue to run as normal.