One of the most useful pieces of information that we can gather about an executable is the list of functions that it imports. Imports are functions used by one program that are actually stored in a different program, such as code libraries that contain functionality common to many programs. Code libraries can be connected to the main executable by linking.

Programmers link imports to their programs so that they don’t need to re-implement certain functionality in multiple programs. Code libraries can be linked statically, at runtime, or dynamically. Knowing how the library code is linked is critical to our understanding of malware because the information we can find in the PE file header depends on how the library code has been linked. We’ll discuss several tools for viewing an executable’s imported functions in this section.

Static linking is the least commonly used method of linking libraries, although it is common in UNIX and Linux programs. When a library is statically linked to an executable, all code from that library is copied into the executable, which makes the executable grow in size. When analyzing code, it’s difficult to differentiate between statically linked code and the executable’s own code, because nothing in the PE file header indicates that the file contains linked code.

While unpopular in friendly programs, runtime linking is commonly used in malware, especially when it’s packed or obfuscated. Executables that use runtime linking connect to libraries only when that function is needed, not at program start, as with dynamically linked programs.

Several Microsoft Windows functions allow programmers to import linked functions not listed in

a program’s file header. Of these, the two most commonly used are LoadLibrary and GetProcAddress. LdrGetProcAddress and LdrLoadDll are

also used. LoadLibrary and GetProcAddress allow a program to access any function in any library on the system, which

means that when these functions are used, you can’t tell statically which functions are being

linked to by the suspect program.

Of all linking methods, dynamic linking is the most common and the most interesting for malware analysts. When libraries are dynamically linked, the host OS searches for the necessary libraries when the program is loaded. When the program calls the linked library function, that function executes within the library.

The PE file header stores information about every library that will be loaded and every

function that will be used by the program. The libraries used and functions called are often the

most important parts of a program, and identifying them is particularly important, because it allows

us to guess at what the program does. For example, if a program imports the function URLDownloadToFile, you might guess that it connects to the Internet to

download some content that it then stores in a local file.

The Dependency Walker program (http://www.dependencywalker.com/), distributed with some versions of Microsoft Visual Studio and other Microsoft development packages, lists only dynamically linked functions in an executable.

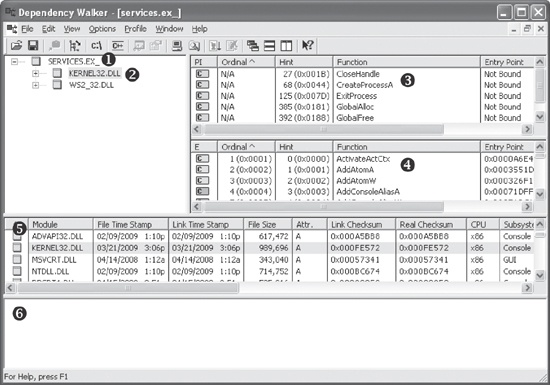

Figure 1-6 shows the Dependency Walker’s analysis of SERVICES.EX_ ❶. The far left pane at ❷ shows the program as well as the DLLs being imported, namely KERNEL32.DLL and WS2_32.DLL.

Clicking KERNEL32.DLL shows its imported functions in the upper-right

pane at ❸. We see several functions, but the most

interesting is CreateProcessA, which tells us that the program

will probably create another process, and suggests that when running the program, we should watch

for the launch of additional programs.

The middle right pane at ❹ lists all functions in KERNEL32.DLL that can be imported—information that is not particularly useful to us. Notice the column in panes ❸ and ❹ labeled Ordinal. Executables can import functions by ordinal instead of name. When importing a function by ordinal, the name of the function never appears in the original executable, and it can be harder for an analyst to figure out which function is being used. When malware imports a function by ordinal, you can find out which function is being imported by looking up the ordinal value in the pane at ❹.

The bottom two panes (❺ and ❻) list additional information about the versions of DLLs that would be loaded if you ran the program and any reported errors, respectively.

A program’s DLLs can tell you a lot about its functionality. For example, Table 1-1 lists common DLLs and what they tell you about an application.

Table 1-1. Common DLLs

DLL | Description |

|---|---|

Kernel32.dll | This is a very common DLL that contains core functionality, such as access and manipulation of memory, files, and hardware. |

Advapi32.dll | This DLL provides access to advanced core Windows components such as the Service Manager and Registry. |

User32.dll | This DLL contains all the user-interface components, such as buttons, scroll bars, and components for controlling and responding to user actions. |

Gdi32.dll | This DLL contains functions for displaying and manipulating graphics. |

Ntdll.dll | This DLL is the interface to the Windows kernel. Executables generally do not import this file directly, although it is always imported indirectly by Kernel32.dll. If an executable imports this file, it means that the author intended to use functionality not normally available to Windows programs. Some tasks, such as hiding functionality or manipulating processes, will use this interface. |

WSock32.dll and Ws2_32.dll | These are networking DLLs. A program that accesses either of these most likely connects to a network or performs network-related tasks. |

Wininet.dll | This DLL contains higher-level networking functions that implement protocols such as FTP, HTTP, and NTP. |

The PE file header also includes information about specific functions used by an executable. The names of these Windows functions can give you a good idea about what the executable does. Microsoft does an excellent job of documenting the Windows API through the Microsoft Developer Network (MSDN) library. (You’ll also find a list of functions commonly used by malware in Appendix A.)

Like imports, DLLs and EXEs export functions to interact with other programs and code. Typically, a DLL implements one or more functions and exports them for use by an executable that can then import and use them.

The PE file contains information about which functions a file exports. Because DLLs are specifically implemented to provide functionality used by EXEs, exported functions are most common in DLLs. EXEs are not designed to provide functionality for other EXEs, and exported functions are rare. If you discover exports in an executable, they often will provide useful information.

In many cases, software authors name their exported functions in a way that provides useful

information. One common convention is to use the name used in the Microsoft documentation. For

example, in order to run a program as a service, you must first define a ServiceMain function. The presence of an exported function called ServiceMain tells you that the malware runs as part of a service.

Unfortunately, while the Microsoft documentation calls this function ServiceMain, and it’s common for programmers to do the same, the function can have

any name. Therefore, the names of exported functions are actually of limited use against

sophisticated malware. If malware uses exports, it will often either omit names entirely or use

unclear or misleading names.

You can view export information using the Dependency Walker program discussed in Exploring Dynamically Linked Functions with Dependency Walker. For a list of exported functions, click the name of the file you want to examine. Referring back to Figure 1-6, window ❹ shows all of a file’s exported functions.