The first subroutine at 0x401000 is the same as in Lab 6-1 Solutions. It’s an

ifstatement that checks for an active Internet connection.printfis the subroutine located at 0x40117F.The second function called from

mainis located at 0x401040. It downloads the web page located at: http://www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com/cc.htm and parses an HTML comment from the beginning of the page.This subroutine uses a character array filled with data from the call to

InternetReadFile. This array is compared one byte at a time to parse an HTML comment.There are two network-based indicators. The program uses the HTTP User-Agent

Internet Explorer 7.5/pmaand downloads the web page located at: http://www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com/cc.htm.First, the program checks for an active Internet connection. If none is found, the program terminates. Otherwise, the program attempts to download a web page using a unique User-Agent. This web page contains an embedded HTML comment starting with

<!--. The next character is parsed from this comment and printed to the screen in the format “Success: Parsed command is X,” where X is the character parsed from the HTML comment. If successful, the program will sleep for 1 minute and then terminate.

We begin by performing basic static analysis on the binary. We see several new strings of interest, as shown in Example C-1.

Example C-1. Interesting new strings contained in Lab 6-2 Solutions

Error 2.3: Fail to get command Error 2.2: Fail to ReadFile Error 2.1: Fail to OpenUrl http://www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com/cc.htm Internet Explorer 7.5/pma Success: Parsed command is %c

The three error message strings that we see suggest that the program may open a web page and parse a command. We also notice a URL for an HTML web page, http://www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com/cc.htm. This domain can be used immediately as a network-based indicator.

These imports contain several new Windows API functions used for networking, as shown in Example C-2.

Example C-2. Interesting new import functions contained in Lab 6-2 Solutions

InternetReadFile InternetCloseHandle InternetOpenUrlA InternetOpenA

All of these functions are part of WinINet, a simple API for using HTTP over a network. They work as follows:

InternetOpenAis used to initialize the use of the WinINet library, and it sets the User-Agent used for HTTP communication.InternetOpenUrlAis used to open a handle to a location specified by a complete FTP or HTTP URL. (Programs use handles to access something that has been opened. We discuss handles in Chapter 7.)InternetReadFileis used to read data from the handle opened byInternetOpenUrlA.InternetCloseHandleis used to close the handles opened by these files.

Next, we perform dynamic analysis. We choose to listen on port 80 because WinINet often uses HTTP and we saw a URL in the strings. If we set up Netcat to listen on port 80 and redirect the DNS accordingly, we will see a DNS query for www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com, after which the program requests a web page from the URL, as shown in Example C-3. This tells us that this web page has some significance to the malware, but we won’t know what that is until we analyze the disassembly.

Example C-3. Netcat output when listening on port 80

C:\>nc -l -p 80 GET /cc.htm HTTP/1.1 User-Agent: Internet Explorer 7.5/pma Host: www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com

Finally, we load the executable into IDA Pro. We begin our analysis with the main method since much of the other code is generated by the compiler.

Looking at the disassembly for main, we notice that it calls the

same method at 0x401000 that we saw in Lab 6-1 Solutions. However, two new calls

(401040 and 40117F) in the

main method were not in Lab 6-1 Solutions.

In the new call to 0x40117F, we notice that two parameters are pushed on the stack

before the call. One parameter is the format string Success: Parsed command

is %c, and the other is the byte returned from the previous call at 0x401148. Format

characters such as %c and %d

tell us that we’re looking at a format string. Therefore, we can deduce that printf is the subroutine located at 0x40117F, and we should rename it as

such, so that it’s renamed everywhere it is referenced. The printf subroutine will print the string with the %c

replaced by the other parameter pushed on the stack.

Next, we examine the new call to 0x401040. This function

contains all of the WinINet API calls we discovered during the basic static analysis process. It

first calls InternetOpen, which initializes the use of the

WinINet library. Notice that Internet Explorer 7.5/pma is pushed

on the stack, matching the User-Agent we noticed during dynamic analysis. The next call is to

InternetOpenUrl, which opens the static web page pushed onto the

stack as a parameter. This function caused the DNS request we saw during dynamic analysis.

Example C-4 shows the InternetOpenUrlA and the InternetReadFile

calls.

Example C-4. InternetOpenUrlA and InternetReadFile calls

00401070 call ds:InternetOpenUrlA00401076 mov [ebp+hFile], eax 00401079 cmp [ebp+hFile], 0 ❶ ... 0040109D lea edx, [ebp+dwNumberOfBytesRead] 004010A0 push edx ; lpdwNumberOfBytesRead 004010A1 push 200h ❸; dwNumberOfBytesToRead 004010A6 lea eax, [ebp+Buffer ❷] 004010AC push eax ; lpBuffer 004010AD mov ecx, [ebp+hFile] 004010B0 push ecx ; hFile 004010B1 call ds:InternetReadFile004010B7 mov [ebp+var_4], eax 004010BA cmp [ebp+var_4], 0 ❹ 004010BE jnz short loc_4010E5

We can see that the return value from InternetOpenUrlA is

moved into the local variable hFile and compared to 0 at

❶. If it is 0, this function will be terminated;

otherwise, the hFile variable will be passed to the next

function, InternetReadFile. The hFile variable is a handle—a way to access something that has been opened. This

handle is accessing a URL.

InternetReadFile is used to read the web page opened by

InternetOpenUrlA. If we read the MSDN page on this API function,

we can learn about the other parameters. The most important of these parameters is the second one,

which IDA Pro has labels Buffer, as shown at ❷. Buffer is an array of data,

and in this case, we will be reading up to 0x200 bytes worth of data, as shown by the NumberOfBytesToRead parameter at ❸. Since we know that this function is reading an HTML web page, we can think of

Buffer as an array of characters.

Following the call to InternetReadFile, code at

❹ checks to see if the return value (EAX) is 0. If it is

0, the function closes the handles and terminates; if not, the code immediately following this line

compares Buffer one character at a time, as shown in Example C-5. Notice that each time, the index into Buffer goes up by 1 before it is moved into a

register, and then compared.

Example C-5. Buffer handling

004010E5 movsx ecx, byte ptr [ebp+Buffer] 004010EC cmp ecx, 3Ch ❺ 004010EF jnz short loc_40111D 004010F1 movsx edx, byte ptr [ebp+Buffer+1] ❻ 004010F8 cmp edx, 21h 004010FB jnz short loc_40111D 004010FD movsx eax, byte ptr [ebp+Buffer+2] 00401104 cmp eax, 2Dh 00401107 jnz short loc_40111D 00401109 movsx ecx, byte ptr [ebp+Buffer+3] 00401110 cmp ecx, 2Dh 00401113 jnz short loc_40111D 00401115 mov al, [ebp+var_20C] ❼ 0040111B jmp short loc_40112C

At ❺, the cmp

instruction checks to see if the first character is equal to 0x3C, which corresponds to the <

symbol in ASCII. We can right-click on 3Ch, and IDA Pro will

offer to change it to display <. In the same way, we can do this throughout the listing for

21h, 2Dh, and 2Dh. If we combine the characters, we will have the string <!--, which happens to be the start of a comment in HTML. (HTML

comments are not displayed when viewing web pages in a browser, but you can see them by viewing the

web page source.)

Notice at ❻ that Buffer+1 is moved into EDX before it is compared to 0x21 (! in ASCII). Therefore, we can

assume that Buffer is an array of characters from the web page

downloaded by InternetReadFile. Since Buffer points to the start of the web page, the four cmp instructions are used to check for an HTML comment immediately at the start of the

web page. If all comparisons are successful, the web page starts with the embedded HTML comment, and

the code at ❼ is executed. (Unfortunately, IDA Pro fails

to realize that the local variable Buffer is of size 512 and has

displayed a local variable named var_20C instead.)

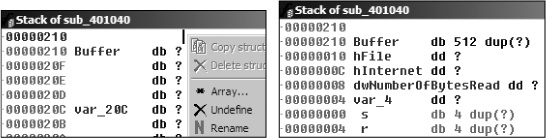

We need to fix the stack of this function to display a 512-byte array in order for the

Buffer array to be labeled properly throughout the function. We

can do this by pressing CTRL-K anywhere within the function. For

example, the left side of Figure C-19 shows the initial

stack view. To fix the stack, we right-click on the first byte of Buffer and define an array 1 byte wide and 512 bytes large. The right side of the figure

shows what the corrected stack should look like.

Manually adjusting the stack like this will cause the instruction numbered ❼ in Example C-5 to be displayed as [ebp+Buffer+4]. Therefore, if the first four characters (Buffer[0]-Buffer[3]) match <!--, the

fifth character will be moved into AL and returned from this function.

Returning to the main method, let’s analyze

what happens after the 0x401040 function returns. If this function returns a nonzero value, the

main method will print as “Success: Parsed command is

X,” where X is the character parsed from the HTML

comment, followed by a call to the Sleep function at 0x401173.

Using MSDN, we learn that the Sleep function takes a single

parameter containing the number of milliseconds to sleep. It pushes 0xEA60 on the stack, which corresponds to sleeping for one minute (60,000

milliseconds).

To summarize, this program checks for an active Internet connection, and then downloads a web

page containing the string <!--, the start of a comment in

HTML. An HTML comment will not be displayed in a web browser, but you can view it by looking at the

HTML page source. This technique of hiding commands in HTML comments is used frequently by attackers

to send commands to malware while having the malware appear as if it were going to a normal web

page.