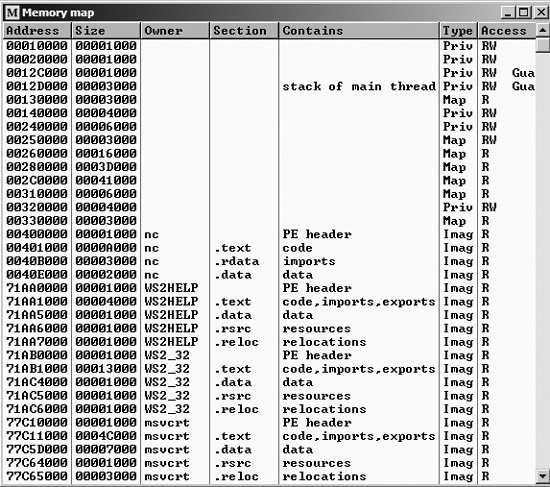

The Memory Map window (View ▶ Memory) displays all memory blocks allocated by the debugged program. Figure 9-4 shows the memory map for the Netcat program.

The memory map is great way to see how a program is laid out in memory. As you can see in Figure 9-4, the executable is labeled along with its code and data sections. All DLLs and their code and data sections are also viewable. You can double-click any row in the memory map to show a memory dump of that section. Or you can send the data in a memory dump to the disassembler window by right-clicking it and selecting View in Disassembler.

The memory map can help you understand how a PE file is rebased during runtime. Rebasing is what happens when a module in Windows is not loaded at its preferred base address.

All PE files in Windows have a preferred base address, known as the image base defined in the PE header.

The image base isn’t necessarily the address where the malware will be loaded, although it usually is. Most executables are designed to be loaded at 0x00400000, which is just the default address used by many compilers for the Windows platform. Developers can choose to base executables at different addresses. Executables that support address space layout randomization (ASLR) security enhancement will often be relocated. That said, relocation of DLLs is much more common.

Relocation is necessary because a single application may import many DLLs, each with a preferred base address in memory where they would like to be loaded. If two DLLs are loaded, and they both have the preferred load address of 0x10000000, they can’t both be loaded there. Instead, Windows will load one of the DLLs at that address, and then relocate the other DLL somewhere else.

Most DLLs that are shipped with the Windows OS have different preferred base addresses and won’t collide. However, third-party applications often have the same preferred base address.

The relocation process is more involved than simply loading the code at another location. Many instructions refer to relative addresses in memory, but others refer to absolute ones. For example, Example 9-1 shows a typical series of instructions.

Example 9-1. Assembly code that requires relocation

00401203 mov eax, [ebp+var_8]

00401206 cmp [ebp+var_4], 0

0040120a jnz loc_0040120

0040120c ❶mov eax, dword_40CF60Most of these instructions will work just fine, no matter where they are loaded in memory

since they use relative addresses. However, the data-access instruction at ❶ will not work, because it uses an absolute address to access a

memory location. If the file is loaded into memory at a location other than the preferred base

location, then that address will be wrong. This instruction must be changed when the file is loaded

at a different address. Most DLLs will come packaged with a list of these fix-up locations in the

.reloc section of the PE header.

DLLs are loaded after the .exe and in any order. This means you cannot generally predict where DLLs will be located in memory if they are rebased. DLLs can have their relocation sections removed, and if a DLL lacking a relocation section cannot be loaded at its preferred base address, then it cannot be loaded.

The relocating of DLLs is bad for performance and adds to load time. The compiler will select a default base address for all DLLs when they are compiled, and generally the default base address is the same for all DLLs. This fact greatly increases the likelihood that relocation will occur, because all DLLs are designed to be loaded at the same address. Good programmers are aware of this, and they select base addresses for their DLLs in order to minimize relocation.

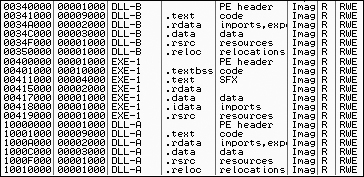

Figure 9-5 illustrates DLL relocation using the memory map functionality of OllyDbg for EXE-1. As you can see, we have one executable and two DLLs. DLL-A, with a preferred load address of 0x10000000, is already in memory. EXE-1 has a preferred load address of 0x00400000. When DLL-B was loaded, it also had preferred load address of 0x10000000, so it was relocated to 0x00340000. All of DLL-B’s absolute address memory references are changed to work properly at this new address.

If you’re looking at DLL-B in IDA Pro while also debugging the application, the addresses will not be the same, because IDA Pro has no knowledge of rebasing that occurs at runtime. You may need to frequently adjust every time you want to examine an address in memory that you got from IDA Pro. To avoid this issue, you can use the manual load process we discussed in Chapter 5.