The program creates the file C:\Windows\System32\Mlwx486.sys. You can use procmon or another dynamic monitoring tool to see the file being created, but you cannot see the file on disk because it is hidden.

The program has a kernel component. It is stored in the file’s resource section, and then written to disk and loaded into the kernel as a service.

The program is a rootkit designed to hide files. It uses SSDT hooking to overwrite the entry to

NtQueryDirectoryFile, which it uses to prevent the display of any files beginning with Mlwx (case-sensitive) in directory listings.

Looking at the imports section of this executable, we see imports for Close-ServiceHandle, CreateServiceA, OpenSCManagerA, and StartServiceA, which tell us that this program will create and start a

service. Because the program also calls CreateFile and WriteFile, we know that it will write to a file at some point. We also see

calls to LoadResource and SizeOfResource, which tell us that this program will do something with the resource

section of Lab10-02.exe.

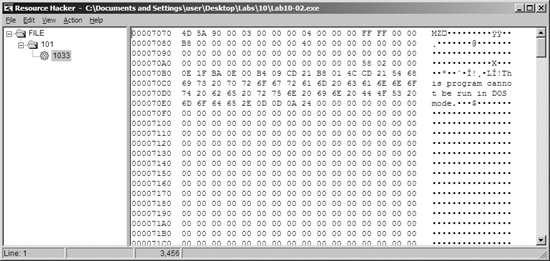

Recognizing that the program accesses the resource section, we use Resource Hacker to examine the resource section. There, we see that the file contains another PE header within the resource section, as shown in Figure C-32. This is probably another file of malicious code that Lab10-02.exe will use.

Next, we run the program and find that it creates a file and a service. Using procmon, we see that the program creates a file in C:\Windows\System32, and that it creates a service that uses that file as the executable. That file contains the kernel code that will be loaded by the OS.

We should next find the file that the program creates in order to analyze it and determine what the kernel code is doing. However, when we look in C:\Windows\System32, we find that there’s nothing there. We can see in procmon that the file is created, and there are no calls that would delete the file. Based on the facts that the file doesn’t appear but we don’t see how it was deleted and that a driver is involved, we should be suspicious that we’re dealing with a rootkit.

In order to continue investigating, we want to check to see if our kernel driver is loaded. To

do that, we use the sc command to check on the status of the

service that is running our kernel driver, as shown in Example C-29.

Example C-29. Using the sc command to get information about a

service

C:\>sc query "486 WS Driver"❶

SERVICE_NAME: 486 WS Driver

TYPE : 1 KERNEL_DRIVER

STATE : ❷4 RUNNING

(STOPPABLE,NOT_PAUSABLE,IGNORES_SHUTDOWN)

WIN32_EXIT_CODE : 0 (0x0)

SERVICE_EXIT_CODE : 0 (0x0)

CHECKPOINT : 0x0

WAIT_HINT : 0x0We query for the service name 486 WS Driver at ❶, which was specified in the call to CreateServiceA. We see at ❷ that the service

is still running, which tells us that the kernel code is in memory. Something fishy is going on

because the driver is still running, but it’s not on disk. Now, to determine what’s

going on, we connect the kernel debugger to our virtual machine, and we check to see if the driver

was actually loaded using the lm command. We see an entry that

matches the filename that was created by Lab10-02.exe:

f7c4d000 f7c4dd80 Mlwx486 (deferred)

We are now certain that the driver is loaded into memory with the filename Mlwx486.sys, but the file does not appear on disk, suggesting that this might be a rootkit.

Next, we check the SSDT for any modified entries, as shown in Example C-30.

Example C-30. An excerpt from the SSDT with one entry that has been modified by a rootkit

kd> dd dwo(KeServiceDescriptorTable) L100

...

80501dbc 8060cb50 8060cb50 8053c02e 80606e68

80501dcc 80607ac8 ❶ f7c4d486 805b3de0 8056f3ca

80501ddc 806053a4 8056c222 8060c2dc 8056fc46

...We see that the entry at ❶ is in a memory location

that is clearly outside the bounds of the ntoskrnl module but

within the loaded Mlwx486.sys driver. To determine which normal function is

being replaced, we revert our virtual machine to before the rootkit was installed to see which

function was stored at the offset into the SSDT that was overwritten. In this case, the function is

NtQueryDirectoryFile, which is a versatile function that

retrieves information about files and directories used by FindFirstFile and FindNextFile to traverse directory

structures. This function is also used by Windows Explorer to display files and directories. If the

rootkit is hooking this function, it could be hiding files, which would explain why we can’t

find Mlwx486.sys. Now that we’ve found a function that is hooking the

SSDT, we must analyze what that function is doing.

We now look more closely at the function called instead of NtQueryDirectoryFile, which we’ll call PatchFunction. The malicious PatchFunction must work

with the same interface as the original function, so we first check the documentation of the

original function. We find that NtQueryDirectoryFile is

technically undocumented according to Microsoft, but a quick Internet search will provide all the

information we need. The NtQueryDirectoryFile function is a very

flexible one with a lot of different parameters that determine what will be returned.

Now, we want to look at the malicious function to see what is being done with the requests. We

set a breakpoint on PatchFunction and discover that the first

thing it does is call the original NtQueryDirectoryFile with all

of the original parameters, as shown in Example C-31.

Example C-31. Assembly listing of PatchFunction

f7c4d490 ff7530 push dword ptr [ebp+30h] f7c4d493 ff752c push dword ptr [ebp+2Ch] f7c4d496 ff7528 push dword ptr [ebp+28h] f7c4d499 ff7524 push dword ptr [ebp+24h] f7c4d49c ff7520 push dword ptr [ebp+20h] f7c4d49f 56 push esi f7c4d4a0 ff7518 push dword ptr [ebp+18h] f7c4d4a3 ff7514 push dword ptr [ebp+14h] f7c4d4a6 ff7510 push dword ptr [ebp+10h] f7c4d4a9 ff750c push dword ptr [ebp+0Ch] f7c4d4ac ff7508 push dword ptr [ebp+8] f7c4d4af e860000000 call Mlwx486+0x514 (f7c4d514)

Note

It’s probably not completely clear from Example C-31 that the function being called is NtQueryDirectoryFile. However, if we single-step over the

call function, we see that it goes to

another section of the file that jumps to NtQueryDirectoryFile. In IDA Pro, this call would have been labeled

NtQueryDirectoryFile, but the disassembler

included in WinDbg is much less sophisticated. Ideally, we would have the file to view in IDA Pro

while we are debugging, but we can’t find this file because it’s

hidden.

The PatchFunction checks the eighth parameter, FileInformationClass, and if it is any value other than 3, it returns

NtQueryDirectoryFile’s original return value. It also

checks the return value from NtQueryDirectoryFile and the value

of the ninth parameter, ReturnSingleEntry. PatchFunction is looking for certain parameters. If the parameters

don’t meet the criteria, then the functionality is exactly the same as the original NtQueryDirectoryFile. If the parameters do meet the criteria, PatchFunction will change the return value, which is what we’re

interested in. To examine what happens during a call to PatchFunction with the correct parameters, we set a breakpoint on PatchFunction.

If we set a breakpoint on PatchFunction, it will break

every time the function is called, but we’re interested in only some of the function calls.

This is the perfect time to use a conditional breakpoint so that the breakpoint is hit only when the

parameters to PatchFunction match our criteria. We set a

breakpoint on PatchFunction, but the breakpoint will be hit only

if the value of ReturnSingleEntry is 0, as follows:

kd> bp f7c4d486 ".if dwo(esp+0x24)==0 {} .else {gc}"Note

If you have Windows Explorer open in a directory, you might see this breakpoint hit

over and over again in different threads, which could be annoying while you’re trying to

analyze the function. To make it easier to analyze, you should close all of your Windows Explorer

windows and use the dir command at a command

line to trigger the breakpoint.

Once the code filters out interesting calls, we see another function stored at offset

0xf7c4d590. Although it isn’t automatically labeled by WinDbg, we can determine that it is

RtlCompareMemory by looking at the disassembly or stepping into

the function call. The code in Example C-32 shows the

call to RtlCompareMemory at ❶.

Example C-32. Comparison of the filename to determine whether the rootkit will modify the returned

information from NtQueryDirectoryFile

f7c4d4ca 6a08 push 8 f7c4d4cc 681ad5c4f7 push offset Mlwx486+0x51a (f7c4d51a) f7c4d4d1 8d465e ❷lea eax,[esi+5Eh] f7c4d4d4 50 push eax f7c4d4d5 32db xor bl,bl f7c4d4d7 ff1590d5c4f7 call dword ptr [Mlwx486+0x590 (f7c4d590)]❶ f7c4d4dd 83f808 cmp eax,8 f7c4d4e0 7512 jne Mlwx486+0x4f4 (f7c4d4f4)

We can now see what PatchFunction is comparing. As

shown in Example C-32, the first parameter to RtlCompareMemory is eax, which stores

the offset at esi+5eh at ❷, which is the offset to a filename. Earlier in our disassembly, we saw that esi was FileInformation, which contains

the information filled in by NtQueryDirectoryFile. Examining the

documentation for NtQueryDirectoryFile, we see that this is a

FILE_BOTH_DIR_INFORMATION structure, and that an offset of 0x5E

is where the filename is stored as a wide character string. (We could also use WinDbg to tell us

what is stored there.)

To see what is stored at location esi+5eh, we use the

db command, as shown in Example C-33. This reveals that the filename is

Installer.h.

Example C-33. Examining the first argument to RtlCompareMemory

kd>db esi+5e036a302e 49 00 6e 00 73 00 74 00-61 00 6c 00 6c 00 65 00I.n.s.t.a.l.l.e. 036a303e 72 00 68 00 00 00 00 00-00 00 f6 bb be f0 6e 70r.h...........np 036a304e c7 01 47 c0 db 46 25 75-cb 01 50 1e c1 f0 6e 70 ..G..F%u..P...np 036a305e c7 01 50 1e c1 f0 6e 70-c7 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 ..P...np........

The other operand of the comparison is the fixed location f7c4d51a, and we can use the

db command to view that as well. Example C-34 shows that the second parameter to RtlCompareMemory stores the letters Mlwx, which

reminds us of the driver Mlwx486.sys.

Example C-34. Examining the second argument to RtlCompareMemory

kd>db f7c4d51af7c4d51a 4d 00 6c 00 77 00 78 00-00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00M.l.w.x......... f7c4d52a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00-00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................ f7c4d53a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00-00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

The call to RtlCompareMemory specifies a size of 8 bytes,

which represents four characters in wide character strings. The code is comparing every file to see

if it starts with the four characters Mlwx. We now have a pretty good idea that

this driver is hiding files that begin with Mlwx.

Having discovered which filenames PatchFunction will

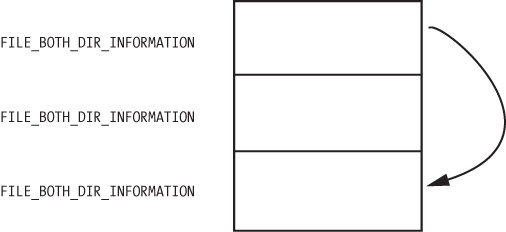

operate on, we analyze how it will change the return values of NtQueryDirectoryFile. Examining the documentation for NtQueryDirectoryFile, we see the FileInformation

structure with a series of FILE_BOTH_DIR_INFORMATION structures.

The first field in the FILE_BOTH_DIR_INFORMATION structure is the

offset that points to the next FILE_BOTH_DIR_INFORMATION. As

shown in Figure C-33, PatchFunction manipulates this field to hide certain files from the directory listing by

moving the offset forward to point to the next entry if the current entry has a filename beginning

with Mlwx.

Figure C-33 shows what the return value of

NtQueryDirectoryFile looks like for a directory that contains

three files. There is one FILE_BOTH_DIR_INFORMATION structure for

each file. Normally, the first structure would point to the second, and the second would point to

the third, but the rootkit has modified the structure so that the first structure points to the

third, thereby hiding the middle structure. This trick ensures that any files that begin with

Mlwx are skipped and hidden from directory listings.

Recovering the Hidden File

Having identified the program that is hiding files, we can try to obtain the original file used by the driver in order to perform additional analysis. There are several ways to do this:

Disable the service that starts the driver and reboot. When you reboot, the code won’t be running and the file won’t be hidden.

Extract the file from the resource section of the executable file that installed it.

Access the file even though it’s not available in the directory listing. The hook to

NtQueryDirectoryFileprevents the file from being shown in a directory listing, but the file still exists. For example, you could copy the file using the DOS commandcopy Mlwx486.sys NewFilename.sys. The NewFilename.sys file would not be hidden.

All of these options are simple enough, but the first is the best because it disables the driver. With the driver disabled, you should first search your system for files beginning with Mlwx in case there are other files being hidden by the Mlwx486.sys driver. (There are none in this case.)

Opening Mlwx486.sys in IDA Pro, we see that it is very small, so we

should analyze all of it to make sure that the driver isn’t doing anything else that

we’re not aware of. We see that the DriverEntry routine

calls RtlInitUnicodeString with KeServiceDescriptorTable and NtQueryDirectoryFile,

and then calls MmGetSystemRoutineAddress to find the

offsets for those two addresses. It next looks for the entry in the SSDT for NtQueryDirectoryFile and overwrites that entry with the address of the

PatchFunction. It doesn’t create a device, and it

doesn’t add any function handlers to the driver object.