The malware appears to be packed. The only import is

ExitProcess, although the strings appear to be mostly clear and not obfuscated.The malware creates a mutex named

WinVMX32, copies itself into C:\Windows\System32\vmx32to64.exe. and installs itself to run on system startup by creating the registry keyHKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\VideoDriverset to the copy location.The malware beacons a consistently sized 256-byte packet containing seemingly random data after resolving www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com.

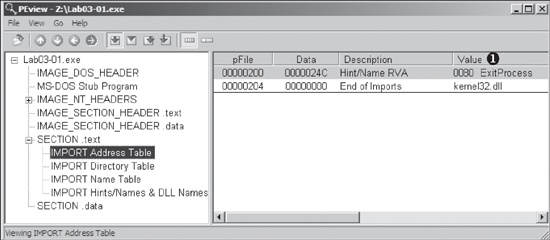

We begin with basic static analysis techniques, by looking at the malware’s PE file structure and strings. Figure C-1 shows that only kernel32.dll is imported.

There is only one import to this binary, ExitProcess,

as seen at ❶ in the import address table. Without any

imports, it is tough to guess the program’s functionality. This program may be packed, since

the imports will likely be resolved at runtime.

Next, we look at the strings, as shown in the following listing.

StubPath SOFTWARE\Classes\http\shell\open\commandV Software\Microsoft\Active Setup\Installed Components\ test www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com admin VideoDriver WinVMX32- vmx32to64.exe SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\Shell Folders AppData

We wouldn’t expect to see strings, since the imports led us to believe that the file is

packed, but there are many interesting strings, such as registry locations and a domain name, as

well as WinVMX32, VideoDriver,

and vmx32to64.exe. Let’s see if basic dynamic analysis

techniques will show us how these strings are used.

Before we run the malware, we run procmon and clear out all events; start Process Explorer; and set up a virtual network, including ApateDNS, Netcat (listening on ports 80 and 443), and network capturing with Wireshark.

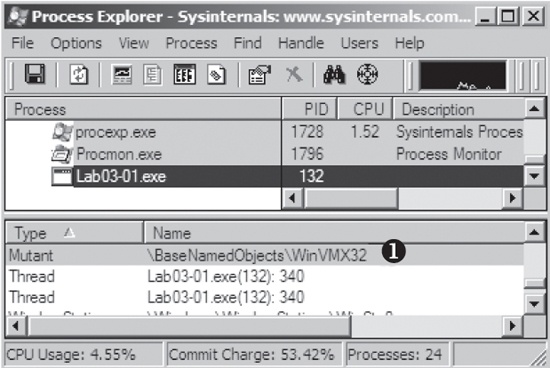

Once we run the malware, we start examining the process in Process Explorer, as shown in Figure C-2. We begin by clicking

Lab03-01.exe in the process listing and select View

▸ Lower Pane View ▸ Handles. In this view, we can see that the malware has

created the mutex named WinVMX32 at ❶. We also select View ▸ Lower Pane

View ▸ DLLs and see that the malware has dynamically loaded DLLs such as

ws2_32.dll and wshtcpip.dll, which means that it has

networking functionality.

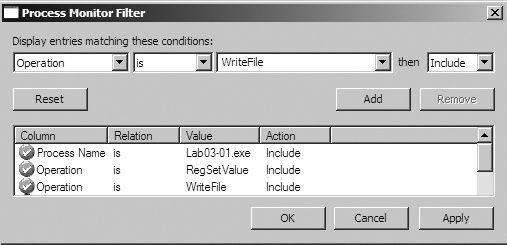

Next, we use procmon to look for additional information. We bring up the Filter dialog

by selecting Filter ▸ Filter, and then set three filters:

one on the Process Name (to show what Lab03-01.exe does to the system), and two

more on Operation, as shown in Figure C-3. We

include RegSetValue and WriteFile to show changes the malware makes to the filesystem and registry.

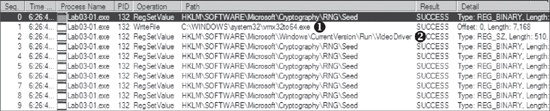

Having set our filters, we click Apply to see the filtered

result. The entries are reduced from thousands to just the 10 seen in Figure C-4. Notice that there is only one entry for

WriteFile, and there are nine entries for RegSetValue.

As discussed in Chapter 3, we often need to filter out

a certain amount of noise, such as entries 0 and 3 through 9 in Figure C-4. The RegSetValue on HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Cryptography\RNG\Seed is typical noise in the results because the

random number generator seed is constantly updated in the registry by software.

We are left with two interesting entries, as shown in Figure C-4 at ❶ and ❷. The first is the WriteFile operation at ❶.

Double-clicking this entry tells us that it wrote 7,168 bytes to

C:\WINDOWS\system32\vmx32to64.exe, which happens to be the same size as that of

the file Lab03-01.exe. Opening Windows Explorer and browsing to that location

shows that this newly created file has the same MD5 hash as Lab03-01.exe, which

tells us that the malware has copied itself to that name and location. This can be a useful

host-based indicator for the malware because it uses a hard-coded filename.

Next, we double-click the entry at ❷ in the figure, and see that the malware wrote the following data to the registry:

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\VideoDriver:C:\WINDOWS\system32\vmx32to64.exe

This newly created registry entry is used to run vmx32to64.exe on system

startup using the HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run location and creating a key named

VideoDriver. We can now bring up procmon’s Filter dialog,

remove the Operation filters, and slowly comb through the entries for any information we may have

missed.

Next, we turn our attention to the network analysis tools we set up for basic dynamic analysis. First we check ApateDNS to see if the malware performed any DNS requests. Examining the output, we see a request for www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com, which matches the strings listing shown earlier. (To be sure that the malware has a chance to make additional DNS requests, if any, perform the analysis process a couple of times to see if the DNS request changes or use the NXDOMAIN functionality of ApateDNS.)

We complete the network analysis by examining the Netcat results, as shown in the following listing.

C:\>nc -l -p 443 \7⌠ëÅ¿A :°I,j!Yûöí?Ç:lfh↨O±ⁿ)α←εg%┬∟#xp╧O+╙3Ω☺nåiE☼?═■p}»╝/ º_∞~]ò£»ú¿¼▬F^"Äμ▒├ ♦∟ªòj╡<û(y!∟♫5Z☺!♀va╪┴╗úI┤ßX╤â8╫²ñö'i¢k╢╓(√Q‼%O¶╡9.▐σÅw♀‼±Wm^┐#ñæ╬°☻/ [⌠│⌡xH╫▲É║‼ x?╦ƺ│ºLf↕x┌gYΦ<└§☻μºx)╤SBxè↕◄╟♂4AÇ

It looks like we got lucky: The malware appears to beacon out over port 443, and we were listening with Netcat over ports 80 and 443. (Use INetSim to listen on all ports at once.) We run this test several times, and the data appears to be random each time.

A follow-up in Wireshark tells us that the beacon packets are of consistent size (256 bytes) and appear to contain random data not related to the SSL protocol that normally operates over port 443.