The hard-coded headers include

Accept,Accept-Language,UA-CPU,Accept-Encoding, andUser-Agent. The malware author mistakenly adds an additionalUser-Agent:in the actual User-Agent, resulting in a duplicate string:User-Agent: User-Agent: Mozilla.... The complete User-Agent header (including the duplicate) makes an effective signature.Both the domain name and path of the URL are hard-coded only where the configuration file is unavailable. Signatures should be made for this hard-coded URL, as well as any configuration files observed. However, it would probably be more fruitful to target just the hard-coded components than to link them with the more dynamic URL. Because the URL used is stored in a configuration file and can be changed with one of the commands, we know that it is ephemeral.

The malware obtains commands from specific components of a web page from inside

noscripttags, which is similar to the Comment field example mentioned in the chapter. Using this technique, malware can beacon to a legitimate web page and receive legitimate content, making analysis of malicious versus legitimate traffic more difficult for a defender.In order for content to be interpreted as a command, it must include an initial

noscripttag followed by a full URL (including http://) that contains the same domain name being used for the original web page request. The path of that URL must end with96'. Between the domain name and the96(which is truncated), two sections compose command and arguments (in a form similar to/command/1213141516). The first letter of the command must correspond with an allowed command, and, when applicable, the argument must be translatable into a meaningful argument for the given command.The malware author limits the strings available to provide clues about the malware functionality. When searching for

noscript, the malware searches for<no, and then verifies thenoscripttag with independent and scrambled character comparisons. The malware also reuses the same buffer used for the domain to check for command content. The other string search for96'is only three characters, and the only other searches are for the/character. When evaluating the command, only the first character is considered, so the attacker may, for example, give the malware the command to sleep with either the wordsoftorsellerin the web response. Traffic analysis might identify the attacker’s use of the wordsoftto send a command to the malware, and that might lead to the misguided use of the complete word in a signature. The attacker is free to useselleror any other word starting withswithout modification of the malware.There is no encoding for the

sleepcommand; the number represents the number of seconds to sleep. For two of the commands, the argument is encoded with a custom, albeit simple, encoding that is not Base64. The argument is presented as an even number of digits (once the trailing96is removed). Each set of two digits represents the raw number that is an index into the array/abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789:.. These arguments are used only to communicate URLs, so there is no need for capital characters. The advantage to this scheme is that it is nonstandard, so we need to reverse-engineer it in order to understand its content. The disadvantage is that it is simple. It may be identified as suspicious in strings output, and because the URLs always begin in the same way, there will be a consistent pattern.The malware commands include

quit,download,sleep, andredirect. Thequitcommand simply quits the program. Thedownloadcommand downloads and runs an executable, except that, unlike in the previous lab, the attacker can specify the URL from which to download. Theredirectcommand modifies the configuration file used by the malware so that there is a new beacon URL.This malware is inherently a downloader. It comes with some important advantages, such as web-based control and the ability to easily adjust as malicious domains are identified and shut down.

Some distinct elements of malware behavior that may be independently targetable include the following:

Signatures related to the statically defined domain and path and similar information from any dynamically discovered URLs

Signatures related to the static components of the beacon

Signatures that identify the initial requirements for a command

Signatures that identify specific attributes of command and argument pairs

See the detailed analysis for specific signatures.

Running the malware, we see that it produces the following beacon packet:

GET /start.htm HTTP/1.1 Accept: */* Accept-Language: en-US UA-CPU: x86 Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate User-Agent: User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 7.0; Windows NT 5.1; .NET CLR 3.0.4506.2152; .NET CLR 3.5.30729) Host: www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com Cache-Control: no-cache

We begin by identifying the networking functions used by the malware. Looking at the imports,

we see functions from two libraries: WinINet and COM. The functions used include InternetOpenA, InternetOpenUrlA,

InternetCloseHandle, and InternetReadFile.

Starting with the WinINet functions, navigate to the function containing InternetOpenUrlA at 0x004011F3. Notice that there are some static strings

in the code leading up to InternetOpenA as shown in Example C-119.

Example C-119. Static strings used in beacon

"Accept: */*\nAccept-Language: en-US\nUA-CPU: x86\nAccept-Encoding: gzip, deflate" "User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 7.0; Windows NT 5.1; .NET CLR 3.0.4506.2152; .NET CLR 3.5.30729)"

These strings agree with the strings in the initial beacon. At first glance, they appear to be fairly common, but the combination of elements may actually be rare. By writing a signature that looks for a specific combination of headers, you can get a sense of exactly how rare the combination is based on how many times the signature is triggered.

Take a second look at the strings in Example C-119 and

compare them with the raw beacon packet at the beginning of the analysis. Do you notice the repeated

User-Agent: User-Agent: in the beacon packet? Although it looks

correct in the strings output, the malware author made a mistake and forgot that the InternetOpenA call includes the header title. This oversight will allow

for an effective signature.

Let’s first identify the beacon content, and then we will investigate how the malware

processes a response. We see that the networking function at 0x004011F3 takes two parameters, only

one of which is used before the InternetOpenUrlA call. This

parameter is the URL that defines the beacon destination. The parent function is WinMain, which contains the primary loop with a Sleep call. Tracing the URL parameter backward within WinMain, we see that it is set in the function at 0x00401457, which contains a CreateFile call. This function (0x00401457) references a couple of

strings, including C:\\autobat.exe and http://www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com/start.htm. The static URL (ending in

start.htm) appears to be on a branch that represents a failure to open a file,

suggesting that it is the fallback beaconing URL if the file does not exist.

Examining the CreateFile function, which uses the reference

to C:\\autobat.exe, it appears as if the ReadFile command takes a buffer as an argument that is eventually passed all the way back

to the InternetOpenUrlA function. Thus, we can conclude that

autobat.exe is a configuration file that stores the URL in plaintext.

Having identified all of the source components of the beacon, navigate back to the original

call to identify what can happen after some content is received. Following the InternetReadFile call at 0x004012C7, we see another call to strstr, with one of the parameters being <no. This strstr function sits within two loops,

with the outer call containing the InternetReadFile call to

obtain more data, and the inner call containing the strstr

function and a call to another function (0x00401000), which is called when we find the <no string, and which we can presume is an additional test of whether

we have found the correct content. This hypothesis is confirmed when we examine the internal

function.

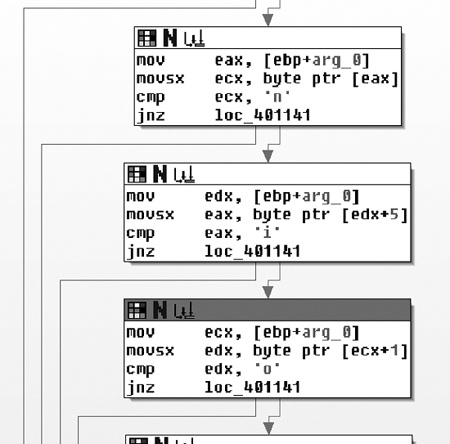

Figure C-56 shows a test of the input buffer using a chain

of small connected blocks. The attacker has tried to disguise the string he is looking for by

breaking the comparison into many small tests to eliminate the telltale comparison string.

Additionally, notice that the required string (<noscript>)

is mixed up in order to avoid producing an obvious pattern. The first three comparisons in Figure C-56 are the n in position 0,

the i in position 5, and the o

in position 1.

Two large comparison blocks follow the single-byte comparisons. The first contains a search

for the / character, as well as a string comparison (strstr) of two strings, both of which are passed in as arguments. With

some backtracking, it is clear that one of the arguments is the string that has been read in

from the Internet, and the other is the URL that originally came from the configuration file. The

search for the / is a backward search within the URL. Once found,

the / is converted to a NULL to NULL-terminate the string.

Essentially, this block is searching for the URL (minus the filename) within the returned

buffer.

The second block is a search for the static string 96'

starting at the end of the truncated URL. There are two paths at the bottom of the function: one

representing a failure to find the desired characteristics and one representing success. Notice the

large number of paths focused on the failure state (loc_401141).

These paths represent an early termination of the search.

In summary, assuming that the default URL is being used, the filter function in this part of

the code is looking for the following (the ellipsis after the noscript tag represents variable content):

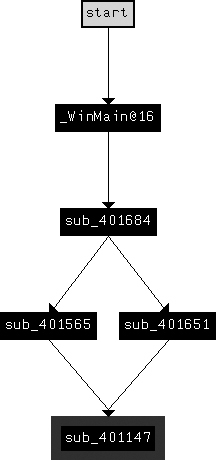

<noscript>... http://www.practicalmalwareanalysis.comreturned_content96'Now, let’s shift focus to what happens with the returned content. Returning to WinMain, we see that the function at 0x00401684 immediately follows the

Internet function (0x004011F3) and takes a similar parameter,

which turns out to be the URL.

This is the decision function, which is confirmed by recognizing the switch structure that

uses a jump table. Before the switch structure, strtok is used to

divide the command content into two parts, which are put into two variables. The following is the

disassembly that pulls the first character out of the first string and uses it for the switch statement:

004016BF mov ecx, [ebp+var_10] 004016C2 movsx edx, byte ptr [ecx] 004016C5 mov [ebp+var_14], edx 004016C8 mov eax, [ebp+var_14] 004016CB sub eax, 'd'

Case 0 is the character 'd'. All other cases are

greater than that value by 10, 14, and 15, which translates to 'n', 'r', and 's'.

The 'n' function is the easiest one to figure out, since it does

nothing other than set a variable that causes the main loop to exit. The 's' function turns out to be sleep, and it uses the

second part of the command directly as a number value for the sleep command. The 'r' and 'd' functions are related, as they both pass the second part of the command into the same

function early in their execution, as shown in Figure C-57.

The 'd' function calls both URLDownloadToCacheFileA and CreateProcessA, and looks

very much like the code from Lab 14-1 Solutions. The URL is provided by the output

of the shared function in Figure C-57 (0x00401147),

which we can now assume is some sort of decoding function. The 'r' function also uses the encoding function, and it takes the output and uses it in the

function at 0x00401372, which references CreateFile, WriteFile, and the same C:\\autobat.exe configuration

file referenced earlier. From this evidence, we can infer that the intent of the 'r' function is to redirect the malware to a different beacon site by

overwriting the configuration file.

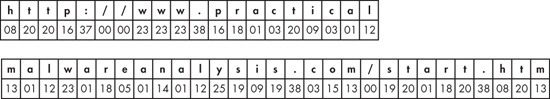

Lastly, let’s look into the encoding function used for the redirect and download functions. We already know that

once decoded, the contents are used as a URL. Examining the decoding function at 0x00401147, notice

the loop in the lower-right corner. At the start of the loop is a call to strlen, which implies that the input is encoded in pieces. Examining the end of the loop,

we see that before returning to the top, the variable containing the output (identified by its

presence at the end of the function) is increased by one, while the source function is increased by

two. The function takes two characters at a time from the source, turns them into a number (with the

atoi function), and then uses that number as an index into the

following string:

/abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789:.

While this string looks somewhat similar to a Base64 string, it doesn’t have capital letters, and it has only 39 characters. (A URL can be adequately described with only lowercase letters.) Given our understanding of the algorithm, let’s encode the default URL for the malware with the encoding shown in Figure C-58.

As you can see, any encoding of a URL that starts with http:// will

always have the string 08202016370000.

Now, let’s use what we’ve learned to generate a suitable set of signatures for the malware. Overall, we have three kinds of communication: beacon packets, commands embedded in web pages, and a request to download and execute a file. Since the request to download is based entirely on the data that comes from the attacker, it is difficult to produce a signature for it.

The beacon packet has the following structure:

GET /start.htm HTTP/1.1 Accept: */* Accept-Language: en-US UA-CPU: x86 Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate User-Agent: User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 7.0; Windows NT 5.1; .NET CLR 3.0.4506.2152; .NET CLR 3.5.30729) Host: www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com Cache-Control: no-cache

The elements in italic are defined by the URL, and they can be ephemeral (though they should

certainly be used if known). The bold elements are static and come from two different strings in the

code (see Example C-119). Since the attacker made a mistake by

including an extra User-Agent:, the obvious signature to target

is the specific User-Agent string with the additional User-Agent header:

alert tcp $HOME_NET any -> $EXTERNAL_NET $HTTP_PORTS (msg:"PM14.3.1 Specific User-Agent with duplicate header"; content:"User-Agent|3a20|User-Agent|3a20| Mozilla/4.0|20|(compatible\;|20|MSIE|20|7.0\;|20|Windows|20|NT|20|5.1\;|20| .NET|20|CLR|20|3.0.4506.2152\;|20|.NET|20|CLR|20|3.5.30729)"; http_header; sid:20001431; rev:1;)

The overall picture of the command provided by the web page is the following:

<noscript>... truncated_url/cmd_char.../arg96'

The malware searches for several static elements in the web page, including the noscript tag, the first characters of the URL

(http://), and the trailing 96'. Since the

parsing function that reads the cmd_char

structure is in a different area of the code and may be changed independently, it should be targeted

separately. Thus, the following is the signature for targeting just the static elements expected by

the malware:

alert tcp $EXTERNAL_NET $HTTP_PORTS -> $HOME_NET any (msg:"PM14.3.2 Noscript tag with ending"; content:"<noscript>"; content:"http\://"; distance:0; within:512; content:"96'"; distance:0; within:512; sid:20001432; rev:1;)

The other section of code to target is the command processing. The commands accepted by the malware are listed in Table C-8.

Table C-8. Malware Commands

Name | Command | Argument |

|---|---|---|

|

| Encoded URL |

|

| NA |

|

| Encoded URL |

|

| Number of seconds |

The download and redirect functions both share the same routine to decode the URL (as shown in Figure C-57), so we will target these two commands

together:

alert tcp $EXTERNAL_NET $HTTP_PORTS -> $HOME_NET any (msg:"PM14.3.3 Download or Redirect Command"; content:"/08202016370000"; pcre:"/\/[dr][^\/]*\/ 08202016370000/"; sid:20001433; rev:1;)

This signature uses the string 08202016370000, which we

previously identified as the encoded representation of http://. The PCRE rule

option includes this string and forward slashes, and the d and

r that indicate the download

and redirect commands. The \/

is an escaped forward slash, the [dr] represents either the

character d or r, the [^\/]* matches zero or more characters that are not a forward slash, and

the \/ is another escaped slash.

The quit command by itself only has one known character,

which is insufficient to target by itself. Thus, the last command we need to target is sleep, which can be detected with the following signature:

alert tcp $EXTERNAL_NET $HTTP_PORTS -> $HOME_NET any (msg:"PM14.3.4 Sleep

Command"; content:"96'"; pcre:"/\/s[^\/]{0,15}\/[0-9]{2,20}96'/"; sid:20001434;

rev:1;)Since there is no fixed content expression target to provide sufficient processing

performance, we will use one element from outside the command string itself (the 96') to achieve an efficient signature. The PCRE identifies the forward

slash followed by an s, then between 0 and 15 characters that are

not a forward slash ('[^\/]{0,15}), a forward slash, and then

between 2 and 20 digits plus a trailing 96'.

Note that the upper and lower bounds on the number of characters that will match the regular

expression are not being driven by what the malware will accept. Rather, they are determined by a

trade-off between what is reasonably expected from an attacker and the costs associated with an

unbounded regular expression. So while the malware may indeed be able to accept a sleep value of more than 20 digits, it is doubtful that the attacker would

send such a value, since that translates to more than 3 trillion years. The 15 characters for the

term starting with an s assumes that the attacker would continue

to choose a single word starting with s, though this value can

certainly be increased if a more foolproof signature is needed.