The malware checks the status of the

BeingDebugged,ProcessHeap, andNTGlobalFlagflags to determine if it is being run in a debugger.If any of the malware’s anti-debugging techniques succeed, it will terminate and remove itself from disk.

You can manually change the jump flags in OllyDbg during runtime, but doing so will get tedious since this malware checks the memory structures so frequently. Instead, modify the structures the malware checks in memory either manually or by using an OllyDbg plug-in like PhantOm or the Immunity Debugger (ImmDbg) PyCommand

hidedebug.See the detailed analysis for a step-by-step way to dump and modify the structures in OllyDbg.

Both the OllyDbg plug-in PhantOm and the ImmDbg PyCommand

hidedebugwill thwart this malware’s checks.

As noted in the lab description, this malware is the same as Lab09-01.exe, except with anti-debugging techniques. Therefore, a good place to start is either by working through Lab 9-1 Solutions or by reviewing your answers.

When we load this malware into OllyDbg, we see that it attempts to delete itself. Suspecting

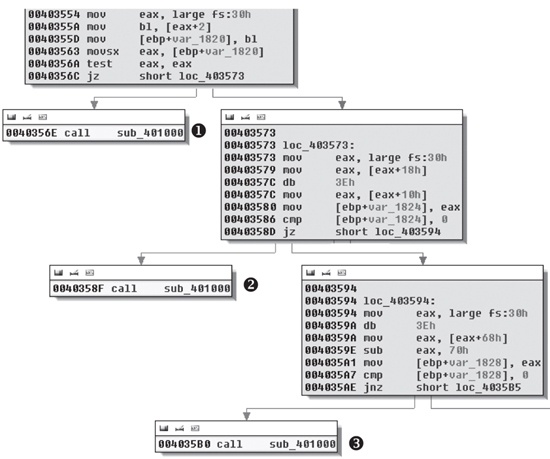

that something must be wrong or that this malware is significantly different from Lab 9-1 Solutions, we load Lab16-01.exe into IDA Pro. As shown in

Figure C-59, we notice that the beginning of the

main method appears suspicious because of several accesses of

fs:[30] and calls to a function that IDA Pro identifies as one

that doesn’t return. In fact, most functions recognized by IDA Pro have this suspicious start.

(None of the functions in Lab 9-1 Solutions have this code.)

Figure C-59. Anti-debugging checks contained at the beginning of most functions in Lab 16-1 Solutions

We see at ❶, ❷, and ❸ in Figure C-59 that sub_401000 is called and the code stops there (no lines leave the boxes). Since a line

doesn’t leave the box, it means the function probably terminates the program or doesn’t

contain a ret instruction. Each large box in Figure C-59 contains a check that decides whether sub_401000 will be called or the malware will continue to execute

normally. (We’ll analyze each of these checks after we look at sub_401000.)

The function sub_401000 is suspicious because execution

won’t return from it, so we examine it further. Example C-141 shows its final instructions.

Example C-141. Function sub_401000 with code to terminate the malware and

remove it from disk

004010CE lea eax, [ebp+Parameters] 004010D4 push eax ; lpParameters 004010D5 push offset File ; "cmd.exe" 004010DA push 0 ; lpOperation 004010DC push 0 ; hwnd 004010DE call ds:ShellExecuteA ❶ 004010E4 push 0 ; Code 004010E6 call _exit ❷

Function sub_401000 ends at ❷ with a call to _exit,

terminating the malware. The call to ShellExecuteA at ❶ removes the malware from disk by launching

cmd.exe using the parameters /c del

Lab16-01.exe. Checking the cross-references to sub_401000, we find 79 of them, most of which come from the anti-debugging code shown in

Figure C-59. Let’s dissect Figure C-59 in more detail.

Example C-142 shows the code in the top box of Figure C-59.

Example C-142. Checking the BeingDebugged flag

00403554 mov eax, large fs:30h ❶ 0040355A mov bl, [eax+2] ❷ 0040355D mov [ebp+var_1820], bl 00403563 movsx eax, [ebp+var_1820] 0040356A test eax, eax 0040356C jz short loc_403573 ❸ 0040356E call sub_401000

As you can see, the PEB structure is loaded into EAX at ❶ using the fs:[30] location, as discussed in Manually Checking Structures. At ❷, the

second byte is accessed and moved into the BL register. At ❸, the code decides whether to call sub_401000 (the

terminate and remove function) or to continue running the malware.

The BeingDebugged flag at offset 2 in the PEB structure is

set to 1 when the process is running inside a debugger, but we need this flag set to 0 in order for

the malware to run normally within a debugger. We can set this byte to 0 either manually or with an

OllyDbg plug-in. Let’s do it manually first.

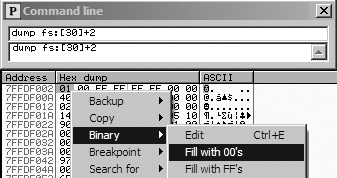

In OllyDbg, make sure you have the Command Line plug-in installed (as discussed in Chapter 9). To launch the plug-in, load the malware in OllyDbg and select Plugins ▸ Command Line. In the command-line window, enter the following command:

dump fs:[30] + 2

This command will dump the BeingDebugged flag into

the dump window. To manually clear the BeingDebugged flag, run

the dump command in the command-line window, as shown in the top

part of Figure C-60. Then right-click the BeingDebugged flag and select Binary ▸ Fill

With 00’s, as shown in the bottom portion of Figure C-60. This sets the flag to 0. With this change, the

BeingDebugged check performed several times at the start of

functions in the malware will no longer call the sub_401000

function.

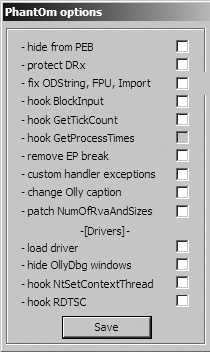

Now let’s try the plug-in approach. The OllyDbg plug-in PhantOm (http://www.woodmann.com/collaborative/tools/index.php/PhantOm) will protect you

from many anti-debug checks used by malware. Download the plug-in and install it by copying it to

your OllyDbg installation directory before launching OllyDbg. Then select Plugins ▸ PhantOm ▸ Options to open the PhantOm Options dialog, as shown in

Figure C-61. Check the first option, Hide from PEB, to set the BeingDebugged flag to 0 the

next time OllyDbg loads malware. (Confirm this by dumping the PEB structure before and after the

plug-in is installed.)

Example C-143 shows the code in the middle box of Figure C-59.

Example C-143. Checking the ProcessHeap flag

00401410 64 A1 30 00 00+ mov eax, large fs:30h ❶ 00401416 8B 40 18 mov eax, [eax+18h] ❷ 00401419 db 3Eh ❺ 00401419 3E 8B 40 10 mov eax, [eax+10h] ❸ 0040141D 89 45 F0 mov [ebp+var_10], eax 00401420 83 7D F0 00 cmp [ebp+var_10], 0 ❹ 00401424 74 05 jz short loc_40142B 00401426 E8 D5 FB FF FF call sub_401000

The PEB structure is loaded into EAX at ❶

using fs:[30]. At ❷,

the ProcessHeap structure (offset 0x18 into the PEB) is moved

into EAX, and then the ForceFlags field (offset 0x10 into the

ProcessHeap structure) is moved into EAX at ❸. ForceFlags is compared to 0

at ❹ to decide whether to call sub_401000 or to continue running normally.

An erroneous db 3Eh instruction was added by IDA Pro at

❺. We displayed the opcodes in Example C-142 to show that the 0x3E is included in the next instruction at ❸. If you look at the disassembly in OllyDbg, you won’t see this error.

Note

When you encounter erroneous db instructions, you can ignore them, but you should display opcodes to

confirm that the byte is disassembled properly in an instruction.

The 4-byte ForceFlags field is nonzero when the ProcessHeap structure is created in the debugger, and the ForceFlags field must be 0 in order for the malware to run normally within

a debugger. We need to change it to 0 when debugging, either manually with the OllyDbg Command Line

plug-in or by using the OllyDbg PhantOm plug-in, as with the BeingDebugged flag.

To set the ForceFlags field to 0 manually, launch the

Command Line plug-in by selecting Plugins ▸ Command Line,

and then enter the following command in the window:

dump ds:[fs:[30] + 0x18] + 0x10

The command dumps the ForceFlags field of the ProcessHeap structure into the dump window. Select all 4 bytes of the

ForceFlags field, and then right-click and select Binary ▸ Fill With 00’s to set the 4 bytes to 0.

Note

In Windows 7, offset 0x10 is no longer the ForceFlags field, so this anti-debugging method may end up falsely indicating the

presence of a debugger on newer versions of Windows (post-XP).

Alternatively, use the PhantOm plug-in to protect against the ProcessHeap anti-debugging technique. The PhantOm plug-in will cause this technique to

fail when you start the program with debug heap creation disabled. (You don’t need to modify

the settings as you did for the BeingDebugged flag.)

The code in the lower box of Figure C-59 is shown in Example C-144.

Example C-144. Checking the NTGlobalFlag flag

00403594 mov eax, large fs:30h ❶ 0040359A db 3Eh ❸ 0040359A mov eax, [eax+68h] ❷ 0040359E sub eax, 70h 004035A1 mov [ebp+var_1828], eax 004035A7 cmp [ebp+var_1828], 0 004035AE jnz short loc_4035B5 004035B0 call sub_401000

The PEB structure is loaded into EAX at ❶

using fs:[30], and NTGlobalFlag is accessed and moved into EAX at ❷. NTGlobalFlag is compared to 0x70, and a decision

is made whether to call sub_401000 (the terminate and remove

function) or to continue executing normally. The erroneous db 3Eh

added by IDA Pro is seen at ❸, and we ignore it.

The NTGlobalFlag flag at offset 0x68 in the PEB structure

is set to 0x70 when the process is run in a debugger. As with the other flags we’ve discussed,

we need to set this byte to 0, either manually or by using an OllyDbg plug-in.

To set NTGlobalFlag manually, launch the Command Line

plug-in by selecting Plugins ▸ Command Line, and then enter

the following command in the window:

dump fs:[30] + 0x68

This dumps the NTGlobalFlag flag into the dump window. As

with the BeingDebugged flag, select the byte, right-click, and

select Binary ▸ Fill With 00’s to set the byte to

0.

You can use also the OllyDbg plug-in PhantOm to protect yourself from the NTGlobalFlag anti-debugging technique without the need to modify any

settings.

Lab 16-1 Solutions uses three different anti-debugging techniques to attempt to thwart debugger analysis. The malware manually checks structures for telltale signs of debugger usage and performs the same three checks at the start of nearly every subroutine, which makes flipping single jump flags tedious when inside a debugger. As you’ve seen, the easiest way to defeat the malware is to change the structures in memory so that the check fails, and you can make this change either manually or with the PhantOm plug-in for OllyDbg.