The malware contains the resource sections

X64,X64DLL, andX86. Each of the resources contains an embedded PE file.Lab21-02.exe is compiled for a 32-bit system. This is shown in the PE header’s

Characteristicsfield, where theIMAGE_FILE_32BIT_MACHINEflag is set.The malware attempts to resolve and call

IsWow64Processto determine if it is running on an x64 system.On an x86 machine, the malware drops the

X86resource to disk and injects it into explorer.exe. On an x64 machine, the malware drops two files from theX64andX64DLLresource sections to disk and launches the executable as a 64-bit process.On an x86 system, the malware drops Lab21-02.dll into the Windows system directory, which will typically be C:\Windows\System32\.

On an x64 system, the malware drops Lab21-02x.dll and Lab21-02x.exe into the Windows system directory, but because this is a 32-bit process running in WOW64, the directory is C:\Windows\SysWOW64\.

On an x64 system, the malware launches Lab21-02x.exe, which is a 64-bit process. You can see this in the PE header, where the

Characteristicsfield has theIMAGE_FILE_64BIT_MACHINEflag set.On both x64 and x86 systems, the malware performs DLL injection into explorer.exe. On an x64 system, it drops and runs a 64-bit binary to inject a 64-bit DLL into the 64-bit running explorer.exe. On an x86 system, it injects a 32-bit DLL into the 32-bit running explorer.exe.

Because this malware is the same as Lab12-01.exe except with an added x64 component, a good place to begin our analysis is with Lab 12-1 Solutions. Let’s start by examining the new strings found in this binary, as follows:

IsWow64Process Lab21-02x.dll X64DLL X64 X86 Lab21-02x.exe Lab21-02.dll

We see a couple of strings that reference x64, as well as the string IsWow64Process, an API call that can tell malware if it is running as a 32-bit process on

a 64-bit machine. We also see three suspicious filenames: Lab21-02.dll, Lab21-02x.dll, and Lab21-02x.exe.

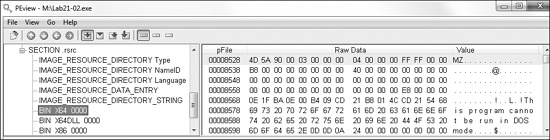

Next, we look at the malware in PEview, as shown in Figure C-70.

We see three different resource sections: X64, X64DLL, and X86. Each appears to

contain an embedded PE format file, as evidenced by the MZ header

and DOS stub. If we perform a quick dynamic analysis of this malware on x86 and x64 systems, they

both produce the annoying pop-ups just like Lab 12-1 Solutions.

Next, we move our analysis to IDA Pro to find out how the malware uses IsWow64Process. We see that Lab21-02.exe begins with

the same code as Lab12-01.exe, which dynamically resolves the API functions for

iterating through the process list. After those functions are resolved, the code deviates and

attempts to dynamically resolve the IsWow64Process function, as

shown in Example C-231.

Example C-231. Dynamically resolving IsWow64Process and calling

it

004012F2 push offset aIswow64process ; "IsWow64Process" 004012F7 push offset ModuleName ; "kernel32" 004012FC mov [ebp+var_10], 0 00401303 call ebx ; GetModuleHandleA ❶ 00401305 push eax ; hModule 00401306 call edi ; GetProcAddress ❷ 00401308 mov myIsWow64Process, eax 0040130D test eax, eax ❸ 0040130F jz short loc_401322 00401311 lea edx, [ebp+var_10] 00401314 push edx 00401315 call ds:GetCurrentProcess 0040131B push eax 0040131C call myIsWow64Process ❹

At ❶, the malware obtains a handle to

kernel32.dll and calls GetProcAddress at

❷ in order to try to resolve IsWow64Process. If it succeeds, it loads the address of the function into myIsWow64Process.

The test at ❸ is used to determine if the malware

found the IsWow64Process function, which is available only on

newer OSs. The malware does this resolution check first for compatibility with older systems that do

not support IsWow64Process. Next, the malware gets its own PID

using GetCurrentProcess, and then calls IsWow64Process at ❹, which will return true

in var_10 only if the process is a 32-bit application running

under WOW64.

Based on the result of the IsWow64Process check, there are

two code paths for the malware to take: x86 and x64. We’ll begin our analysis with the x86

path.

The x86 code path first passes the strings Lab21-02.dll and

X86 to sub_401000. Based on

our static analysis, we can guess and rename this function extractResource, as shown in Example C-232

at ❶.

Example C-232. extractResource being called with X86 parameters

004013D9 push offset aLab2102_dll ; "Lab21-02.dll"

004013DE push offset aX86 ; "X86"

004013E3 call extractResource ❶ ; formerly sub_401000Examining the extractResource function, we see that it, in

fact, extracts the X86 resource to disk and appends the second

argument to the result of GetSystemDirectoryA, thereby extracting

the X86 resource to

C:\Windows\System32\Lab21-02.dll.

Next, the malware sets SeDebugPrivilege with the call to

sub_401130, which uses the API functions OpenProcessToken, LookupPrivilegeValueA, and AdjustTokenPrivileges, as explained in Using SeDebugPrivilege. Then the malware calls EnumProcesses and loops through the process list looking for a module base name of

explorer.exe using the strnicmp function.

Finally, the malware performs DLL injection of Lab21-02.dll into

explorer.exe using VirtualAllocEx and

CreateRemoteThread. This method of DLL injection is identical to

Lab 12-1 Solutions. Comparing the MD5 hash of Lab21-02.dll

with Lab12-01.dll, we see that they are identical. Therefore, we conclude that

this malware operates the same as Lab 12-1 Solutions when it is run on a 32-bit

machine. We must investigate the x64 code path to figure out if this malware operates differently on

a 64-bit machine.

The x64 code path begins by calling the extractResource

function twice to extract the X64 and X64DLL resources to disk, as shown in Example C-233.

Example C-233. Resource extraction of two binaries when run on x64

0040132F push offset aLab2102x_dll ; "Lab21-02x.dll" 00401334 push offset aX64dll ; "X64DLL" 00401339 mov eax, edi 0040133B call extractResource ... 0040134D push offset aLab2102x_exe ; "Lab21-02x.exe" 00401352 push offset aX64 ; "X64" 00401357 mov eax, edi 00401359 call extractResource

The two binaries are extracted to the files Lab21-02x.dll and

Lab21-02x.exe, and placed into the directory returned by GetSystemDirectoryA. However, if we run this malware dynamically on a

64-bit system, we won’t see those binaries in C:\Windows\System32. Since

Lab21-02.exe is a 32-bit binary running on a 64-bit machine, it is running

under WOW64. The system directory is mapped to C:\Windows\SysWOW64, and that is

where we will find these files on a 64-bit machine.

Next, the malware launches Lab21-02x.exe on the local machine using

ShellExecuteA. Looking at the PE header of

Lab21-02x.exe, we see that the IMAGE_FILE_64BIT_MACHINE flag is set for the Characteristics field. This tells us that this binary is compiled for and will run as a

64-bit process.

In order to disassemble Lab21-02x.exe with IDA Pro, we need to use the

x64 advanced version of IDA Pro. When we disassemble this file, we see that from a high level, its

structure looks like Lab21-02.exe. For example,

Lab21-02x.exe also starts by dynamically resolving the API functions for

iterating through the process list. Lab21-02x.exe deviates from

Lab21-02.exe when it builds a string using lstrcpyA and lstrcatA, as seen at ❶ and ❷ in Example C-234.

Example C-234. Building the DLL path string and writing it to a remote process

00000001400011BF lea rdx, String2 ; "C:\\Windows\\SysWOW64\\" 00000001400011C6 lea rcx, [rsp+1168h+Buffer] ; lpString1 ... 00000001400011D2 call cs:lstrcpyA ❶ 00000001400011D8 lea rdx, aLab2102x_dll ; "Lab21-02x.dll" 00000001400011DF lea rcx, [rsp+1168h+Buffer] ; lpString1 00000001400011E4 call cs:lstrcatA ❷ ... 00000001400012CF lea r8, [rsp+1168h+Buffer]❸ ; lpBuffer 00000001400012D4 mov r9d, 104h ; nSize 00000001400012DA mov rdx, rax ; lpBaseAddress 00000001400012DD mov rcx, rsi ; hProcess 00000001400012E0 mov [rsp+1168h+var_1148], 0 00000001400012E9 call cs:WriteProcessMemory

The string built matches the location of where the DLL was dropped to disk:

C:\Windows\SysWOW64\Lab21-02x.dll. The result of this string will be contained

in the local variable Buffer (shown in bold in the listing).

Buffer is eventually passed to WriteProcessMemory in register r8 (lpBuffer parameter) at ❸, and

luckily IDA Pro has recognized and added comments for the parameters, even though there are not any

push instructions.

Seeing the DLL string written to memory like this followed by a call to CreateRemoteThread tells us that this binary also performs DLL injection.

We find the string explorer.exe in the strings listing and track

its cross-reference to 0x140001100, as shown in Example C-235 at ❶.

Example C-235. Code that uses QueryFullProcessImageNameA to look for the

explorer.exe process

00000001400010FA call cs:QueryFullProcessImageNameA

0000000140001100 lea rdx, aExplorer_exe ❶ ; "explorer.exe"

0000000140001107 lea rcx, [rsp+138h+var_118]

000000014000110C call sub_140001368This code is called within the process iteration loop, and the result of QueryFullProcessImageNameA is passed with explorer.exe to sub_140001368. By inference, we can

conclude that this is some sort of string-comparison function that the IDA Pro FLIRT library

didn’t recognize.

This malware operates in the same way as the x86 version by injecting into explorer.exe. However, this 64-bit version injects into the 64-bit version of Explorer. We open Lab21-02x.dll in the advanced version of IDA Pro and see that it is identical to Lab21-02.dll, but compiled for x64.