The import table contains kernel32.dll, NetAPI32.dll, DLL1.dll, and DLL2.dll. The malware dynamically loads user32.dll and DLL3.dll.

All three DLLs request the same base address: 0x10000000.

DLL1.dll is loaded at 0x10000000, DLL2.dll is loaded at 0x320000, and DLL3.dll is loaded at 0x380000 (this may be slightly different on your machine).

DLL1Printis called, and it prints “DLL 1 mystery data,” followed by the contents of a global variable.DLL2ReturnJreturns a filename of temp.txt which is passed to the call toWriteFile.Lab09-03.exe gets the buffer for the call to

NetScheduleJobAddfromDLL3GetStructure, which it dynamically resolves.Mystery data 1 is the current process identifier, mystery data 2 is the handle to the open temp.txt file, and mystery data 3 is the location in memory of the string

ping www.malwareanalysisbook.com.Select Manual Load when loading the DLL with IDA Pro, and then type the new image base address when prompted. In this case, the address is 0x320000.

We start by examining the import table of Lab09-03.exe and it contains

kernel32.dll, NetAPI32.dll, DLL1.dll,

and DLL2.dll. Next, we load Lab09-03.exe into IDA Pro. We

look for calls to LoadLibrary and check which strings are pushed

on the stack before the call. We see two cross-references to LoadLibrary that push user32.dll and DLL3.dll

respectively, so that these DLLs may be loaded dynamically during runtime.

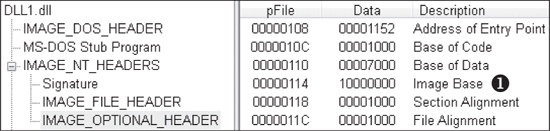

We can check the base address requested by the DLLs by using PEview, as shown in Figure C-30. After loading DLL1.dll

into PEview, click the IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER and look at the

value of Image Base, as shown at ❶ in the figure. We

repeat this process with DLL2.dll and DLL3.dll, and see

that they all request a base address of 0x10000000.

Next, we want to figure out at which memory address the three DLLs are loaded during

runtime. DLL1.dll and DLL2.dll are loaded immediately

because they’re in the import table. Since DLL3.dll is loaded

dynamically, we will need to run the LoadLibrary function located

at 0x401041. We can do this by loading Lab09-03.exe into OllyDbg, setting a

breakpoint at 0x401041, and clicking play. Once the breakpoint hits, we can step over the call to

LoadLibrary. At this point, all three DLLs are loaded into

Lab09-03.exe.

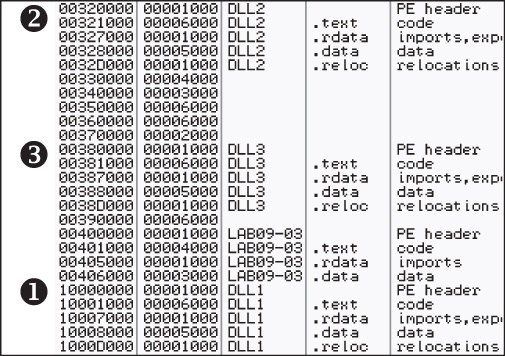

We bring up the memory map by selecting View ▸ Memory. The memory map is shown in Figure C-31 (it may appear slightly different on your machine). At ❶, we see that DLL1.dll gets its preferred base address of 0x10000000. At ❷, we see that DLL2.dll didn’t get its preferred base address because DLL1.dll was already loaded at that location, so DLL2.dll is loaded at 0x320000. Finally, at ❸, we see that DLL3.dll is loaded at 0x380000.

Example C-19 shows the calls to the exports of DLL1.dll and DLL2.dll.

Example C-19. Calls to the exports of DLL1.dll and DLL2.dll from Lab09-03.exe

00401006 call ds:DLL1Print0040100C call ds:DLL2Print00401012 call ds:DLL2ReturnJ00401018 mov [ebp+hObject], eax ❶ 0040101B push 0 ; lpOverlapped 0040101D lea eax, [ebp+NumberOfBytesWritten] 00401020 push eax ; lpNumberOfBytesWritten 00401021 push 17h ; nNumberOfBytesToWrite 00401023 push offset aMalwareanalysi ; "malwareanalysisbook.com" 00401028 mov ecx, [ebp+hObject] 0040102B push ecx ❷ ; hFile 0040102C call ds:WriteFile

At the start of Example C-19, we see a call to

DLL1Print, which is an export of DLL1.dll.

We disassemble DLL1.dll with IDA Pro and see that the function prints

“DLL 1 mystery data,” followed by the contents of a global variable, dword_10008030. If we examine the cross-references to dword_10008030, we see that it is accessed in DllMain when the return value from the call GetCurrentProcessId is moved into it. Therefore, we

can conclude that DLL1Print prints the current process ID, which

it determines when the DLL is first loaded into the process.

In Example C-19, we see calls to two exports

from DLL2.dll: DLL2Print and DLL2ReturnJ. We can disassemble DLL2.dll with IDA Pro

and examine DLL2Print to see that it prints “DLL 2 mystery

data,” followed by the contents of a global variable, dword_1000B078. If we examine the cross-references to dword_1000B078, we see that it is accessed in DllMain

when the handle to CreateFileA is moved into it. The CreateFileA function opens a file handle to temp.txt,

which the function creates if it doesn’t already exist. DLL2Print apparently prints the value of the handle for temp.txt. We

can look at the DLL2ReturnJ export and find that it returns the

same handle that DLL2Print prints. Further in Example C-19, at ❶, the handle is moved into hObject, which is passed

to WriteFile at ❷

defining where malwareanalysisbook.com is written.

After the WriteFile in Lab09-03.exe,

DLL3.dll is loaded with a call to LoadLibrary, followed by the dynamic resolution of DLL3Print and DLL3GetStructure using GetProcAddress. First, it calls DLL3Print, which prints “DLL 3 mystery data,” followed by the contents of a

global variable found at 0x1000B0C0. When we check the cross-references for the global variable, we

see that it is initialized in DllMain to the string ping www.malwareanalysisbook.com, so the memory location of the string

will again be printed. DLL3GetStructure appears to return a

pointer to the global dword_1000B0A0, but it is unclear what data

is in that location. DllMain appears to initialize some sort of

structure at this location using data and the string. Since DLL3GetStructure sets a pointer to this structure, we will need to see how

Lab09-03.exe uses the data to figure out the contents of the structure. Example C-20 shows the call to DLL3GetStructure at ❶.

Example C-20. Calls to DLL3GetStructure followed by NetScheduleJobAdd in Lab09-03.exe

00401071 lea edx, [ebp+Buffer] 00401074 push edx 00401075 call [ebp+var_10] ❶ ;DLL3GetStructure00401078 add esp, 4 0040107B lea eax, [ebp+JobId] 0040107E push eax ; JobId 0040107F mov ecx, [ebp+Buffer] 00401082 push ecx ; Buffer 00401083 push 0 ; Servername 00401085 callNetScheduleJobAdd

It appears that the result of that call is the structure pointed to by Buffer, which is subsequently passed to NetScheduleJobAdd. Viewing the MSDN page for NetScheduleJobAdd tells us that Buffer is a pointer to

an AT_INFO structure.

The AT_INFO structure can be applied to the data in

DLL3.dll. First, load DLL3.dll into IDA Pro, press the

INSERT key within the Structures window, and add the standard

structure AT_INFO. Next, go to dword_1000B0A0 in memory and select Edit ▸ Struct Var and click AT_INFO. This will cause the data to be

more readable, as shown in Example C-21. We can see that the

scheduled job will be set to ping malwareanalysisbook.com every day of the week at 1:00 AM.

We can load DLL2.dll into IDA Pro in a different location by checking the

Manual Load box when loading the DLL. In the field that says

Please specify the new image base, we type 320000. IDA Pro will do the rest to

adjust all of the offsets, just as OllyDbg did when loading the DLL.

This lab demonstrated how to determine where three DLLs are loaded into

Lab09-03.exe using OllyDbg. We loaded these DLLs into IDA Pro to perform full

analysis, and then figured out the mystery data printed by the malware: mystery data 1 is the

current process identifier, mystery data 2 is the handle to the open temp.txt,

and mystery data 3 is the location in memory of the string ping

www.malwareanalysisbook.com. Finally, we applied the Windows AT_INFO structure within IDA Pro to aid our analysis of

DLL3.dll.