Attackers often go to great lengths to steal credentials, primarily with three types of malware:

Programs that wait for a user to log in in order to steal their credentials

Programs that dump information stored in Windows, such as password hashes, to be used directly or cracked offline

Programs that log keystrokes

In this section, we will discuss each of these types of malware.

On Windows XP, Microsoft’s Graphical Identification and Authentication (GINA) interception is a technique that malware uses to steal user credentials. The GINA system was intended to allow legitimate third parties to customize the logon process by adding support for things like authentication with hardware radio-frequency identification (RFID) tokens or smart cards. Malware authors take advantage of this third-party support to load their credential stealers.

GINA is implemented in a DLL, msgina.dll, and is loaded by the Winlogon executable during the login process. Winlogon also works for third-party customizations implemented in DLLs by loading them in between Winlogon and the GINA DLL (like a man-in-the-middle attack). Windows conveniently provides the following registry location where third-party DLLs will be found and loaded by Winlogon:

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Winlogon\GinaDLL

In one instance, we found a malicious file fsgina.dll installed in this registry location as a GINA interceptor.

Figure 11-2 shows an example of the way that logon credentials flow through a system with a malicious file between Winlogon and msgina.dll. The malware (fsgina.dll) is able to capture all user credentials submitted to the system for authentication. It can log that information to disk or pass it over the network.

Because fsgina.dll intercepts the communication between Winlogon and

msgina.dll, it must pass the credential information on to

msgina.dll so that the system will continue to operate normally. In order to do

so, the malware must contain all DLL exports required by GINA; specifically, it must export more

than 15 functions, most of which are prepended with Wlx. Clearly, if you find

that you are analyzing a DLL with many export functions that begin with the string Wlx, you have a good indicator that you are examining a GINA

interceptor.

Most of these exports simply call through to the real functions in

msgina.dll. In the case of fsgina.dll, all but the

WlxLoggedOutSAS export call through to the real functions. Example 11-1 shows the WlxLoggedOutSAS export of fsgina.dll.

Example 11-1. GINA DLL WlxLoggedOutSAS export function for logging

stolen credentials

100014A0 WlxLoggedOutSAS

100014A0 push esi

100014A1 push edi

100014A2 push offset aWlxloggedout_0 ; "WlxLoggedOutSAS"

100014A7 call Call_msgina_dll_function ❶

...

100014FB push eax ; Args

100014FC push offset aUSDSPSOpS ;"U: %s D: %s P: %s OP: %s"

10001501 push offset aDRIVERS ; "drivers\tcpudp.sys"

10001503 call Log_To_File ❷As you can see at ❶, the credential

information is immediately passed to msgina.dll by the call we have labeled

Call_msgina_dll_function. This function dynamically resolves and

calls WlxLoggedOutSAS in msgina.dll, which

is passed in as a parameter. The call at ❷ performs the

logging. It takes parameters of the credential information, a format string that will be used to

print the credentials, and the log filename. As a result, all successful user logons are logged to

%SystemRoot%\system32\drivers\tcpudp.sys. The log includes the username,

domain, password, and old password.

Dumping Windows hashes is a popular way for malware to access system credentials. Attackers try to grab these hashes in order to crack them offline or to use them in a pass-the-hash attack. A pass-the-hash attack uses LM and NTLM hashes to authenticate to a remote host (using NTLM authentication) without needing to decrypt or crack the hashes to obtain the plaintext password to log in.

Pwdump and the Pass-the-Hash (PSH) Toolkit are freely available packages that provide hash dumping. Since both of these tools are open source, a lot of malware is derived from their source code. Most antivirus programs have signatures for the default compiled versions of these tools, so attackers often try to compile their own versions in order to avoid detection. The examples in this section are derived versions of pwdump or PSH that we have encountered in the field.

Pwdump is a set of programs that outputs the LM and NTLM password hashes of local user accounts from the Security Account Manager (SAM). Pwdump works by performing DLL injection inside the Local Security Authority Subsystem Service (LSASS) process (better known as lsass.exe). We’ll discuss DLL injection in depth in Chapter 12. For now, just know that it is a way that malware can run a DLL inside another process, thereby providing that DLL with all of the privileges of that process. Hash dumping tools often target lsass.exe because it has the necessary privilege level as well as access to many useful API functions.

Standard pwdump uses the DLL lsaext.dll. Once it is running inside

lsass.exe, pwdump calls GetHash, which is

exported by lsaext.dll in order to perform the hash extraction. This extraction

uses undocumented Windows function calls to enumerate the users on a system and get the password

hashes in unencrypted form for each user.

When dealing with pwdump variants, you will need to analyze DLLs in order to determine how the

hash dumping operates. Start by looking at the DLL’s exports. The default export name for

pwdump is GetHash, but attackers can easily change the name to make it less obvious. Next, try to determine the API

functions used by the exports. Many of these functions will be dynamically resolved, so the hash

dumping exports often call GetProcAddress many times.

Example 11-2 shows the code in the exported

function GrabHash from a pwdump variant DLL. Since this DLL was

injected into lsass.exe, it must manually resolve numerous symbols before using

them.

Example 11-2. Unique API calls used by a pwdump variant’s export function GrabHash

1000123F push offset LibFileName ; "samsrv.dll" ❶ 10001244 call esi ; LoadLibraryA ... 10001248 push offset aAdvapi32_dll_0 ; "advapi32.dll" ❷ ... 10001251 call esi ; LoadLibraryA ... 1000125B push offset ProcName ; "SamIConnect" 10001260 push ebx ; hModule ... 10001265 call esi ; GetProcAddress ... 10001281 push offset aSamrqu ; "SamrQueryInformationUser" 10001286 push ebx ; hModule ... 1000128C call esi ; GetProcAddress ... 100012C2 push offset aSamigetpriv ; "SamIGetPrivateData" 100012C7 push ebx ; hModule ... 100012CD call esi ; GetProcAddress 100012CF push offset aSystemfuncti ; "SystemFunction025" ❸ 100012D4 push edi ; hModule ... 100012DA call esi ; GetProcAddress 100012DC push offset aSystemfuni_0 ; "SystemFunction027" ❹ 100012E1 push edi ; hModule ... 100012E7 call esi ; GetProcAddress

Example 11-2 shows the code obtaining handles to

the libraries samsrv.dll and advapi32.dll via LoadLibrary at ❶ and ❷. Samsrv.dll contains an API to easily

access the SAM, and advapi32.dll is resolved to access functions not already

imported into lsass.exe. The pwdump variant DLL uses the handles to these

libraries to resolve many functions, with the most important five shown in the listing (look for the

GetProcAddress calls and parameters).

The interesting imports resolved from samsrv.dll are SamIConnect, SamrQueryInformationUser,

and SamIGetPrivateData. Later in the code, SamIConnect is used to connect to the SAM, followed by calling SamrQueryInformationUser for each user on the system.

The hashes will be extracted with SamIGetPrivateData and

decrypted by SystemFunction025 and SystemFunction027, which are imported from advapi32.dll, as seen at

❸ and ❹.

None of the API functions in this listing are documented by Microsoft.

The PSH Toolkit contains programs that dump hashes, the most popular of which is known

as whosthere-alt. whosthere-alt dumps the SAM by injecting a DLL into

lsass.exe, but using a completely different set of API functions from pwdump.

Example 11-3 shows code from a whosthere-alt variant

that exports a function named TestDump.

Example 11-3. Unique API calls used by a whosthere-alt variant’s export function TestDump

10001119 push offset LibFileName ; "secur32.dll" 1000111E call ds:LoadLibraryA 10001130 push offset ProcName ; "LsaEnumerateLogonSessions" 10001135 push esi ; hModule 10001136 call ds:GetProcAddress ❶ ... 10001670 call ds:GetSystemDirectoryA 10001676 mov edi, offset aMsv1_0_dll ; \\msv1_0.dll ... 100016A6 push eax ; path to msv1_0.dll 100016A9 call ds:GetModuleHandleA ❷

Since this DLL is injected into lsass.exe, its TestDump function performs the hash dumping. This export dynamically loads

secur32.dll and resolves its LsaEnumerateLogonSessions function at ❶ to

obtain a list of locally unique identifiers (known as LUIDs). This list contains the usernames and

domains for each logon and is iterated through by the DLL, which gets access to the credentials by

finding a nonexported function in the msv1_0.dll Windows DLL in the memory

space of lsass.exe using the call to GetModuleHandle shown at ❷. This function,

NlpGetPrimaryCredential, is used to dump the NT and LM

hashes.

Note

While it is important to recognize the dumping technique, it might be more critical to determine what the malware is doing with the hashes. Is it storing them on a disk, posting them to a website, or using them in a pass-the-hash attack? These details could be really important, so identifying the low-level hash dumping method should be avoided until the overall functionality is determined.

Keylogging is a classic form of credential stealing. When keylogging, malware records keystrokes so that an attacker can observe typed data like usernames and passwords. Windows malware uses many forms of keylogging.

Kernel-based keyloggers are difficult to detect with user-mode applications. They are frequently part of a rootkit and they can act as keyboard drivers to capture keystrokes, bypassing user-space programs and protections.

Windows user-space keyloggers typically use the Windows API and are usually implemented

with either hooking or polling. Hooking uses the Windows API to notify the

malware each time a key is pressed, typically with the SetWindowsHookEx function. Polling uses the Windows API to

constantly poll the state of the keys, typically using the GetAsyncKeyState and GetForegroundWindow

functions.

Hooking keyloggers leverage the Windows API function SetWindowsHookEx. This type of keylogger may come packaged as an executable that

initiates the hook function, and may include a DLL file to handle logging that can be mapped into

many processes on the system automatically. We discuss using SetWindowsHookEx in Chapter 12.

We’ll focus on polling keyloggers that use GetAsyncKeyState and GetForegroundWindow. The GetAsyncKeyState function identifies whether a key is pressed or

depressed, and whether the key was pressed after the most recent call to GetAsyncKeyState. The GetForegroundWindow function

identifies the foreground window—the one that has focus—which tells the keylogger which

application is being used for keyboard entry (Notepad or Internet Explorer, for example).

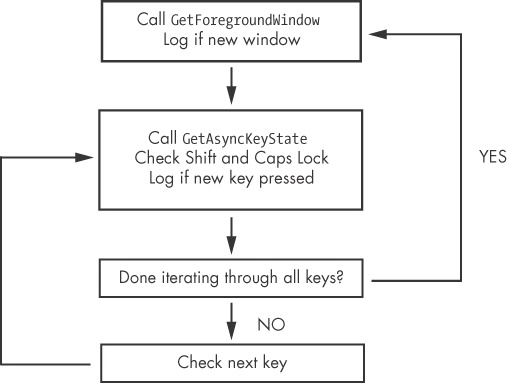

Figure 11-3 illustrates a typical loop

structure found in a polling keylogger. The program begins by calling GetForegroundWindow, which logs the active window. Next, the inner loop iterates through

a list of keys on the keyboard. For each key, it calls GetAsyncKeyState to determine if a key has been pressed. If so, the program checks the

SHIFT and CAPS LOCK keys to

determine how to log the keystroke properly. Once the inner loop has iterated through the entire

list of keys, the GetForegroundWindow function is called again to

ensure the user is still in the same window. This process repeats quickly enough to keep up with a

user’s typing. (The keylogger may call the Sleep function

to keep the program from eating up system resources.)

Example 11-4 shows the loop structure in Figure 11-3 disassembled.

Example 11-4. Disassembly of GetAsyncKeyState and GetForegroundWindow keylogger

00401162 call ds:GetForegroundWindow ... 00401272 push 10h ❶ ; nVirtKey Shift 00401274 call ds:GetKeyState 0040127A mov esi, dword_403308[ebx] ❷ 00401280 push esi ; vKey 00401281 movsx edi, ax 00401284 call ds:GetAsyncKeyState 0040128A test ah, 80h 0040128D jz short loc_40130A 0040128F push 14h ; nVirtKey Caps Lock 00401291 call ds:GetKeyState ... 004013EF add ebx, 4 ❸ 004013F2 cmp ebx, 368 004013F8 jl loc_401272

The program calls GetForegroundWindow before entering the

inner loop. The inner loop starts at ❶ and immediately

checks the status of the SHIFT key using a call to GetKeyState. GetKeyState is a quick way

to check a key status, but it does not remember whether or not the key was pressed since the last

time it was called, as GetAsyncKeyState does. Next, at ❷ the keylogger indexes an array of the keys on the keyboard using

EBX. If a new key is pressed, then the keystroke is logged after calling GetKeyState to see if CAPS LOCK is activated.

Finally, EBX is incremented at ❸ so that the next key in

the list can be checked. Once 92 keys (368/4) have been checked, the inner loop terminates, and

GetForegroundWindow is called again to start the inner loop from

the beginning.

You can recognize keylogger functionality in malware by looking at the imports for the API functions, or by examining the strings listing for indicators, which is particularly useful if the imports are obfuscated or the malware is using keylogging functionality that you have not encountered before. For example, the following listing of strings is from the keylogger described in the previous section:

[Up] [Num Lock] [Down] [Right] [UP] [Left] [PageDown]

If a keylogger wants to log all keystrokes, it must have a way to print keys like PAGE DOWN, and must have access to these strings. Working backward from the cross-references to these strings can be a way to recognize keylogging functionality in malware.