The attacker may find static IP addresses more difficult to manage than domain names. Using DNS allows the attacker to deploy his assets to any computer and dynamically redirect his bots by changing only a DNS address. The defender has various options for deploying defenses for both types of infrastructure, but for similar reasons, IP addresses can be more difficult to deal with than domain names. This fact alone could lead an attacker to choose static IP addresses over domains.

The malware uses the WinINet libraries. One disadvantage of these libraries is that a hard-coded User-Agent needs to be provided, and optional headers need to be hard-coded if desired. One advantage of the WinINet libraries over the Winsock API, for example, is that some elements, such as cookies and caching headers, are provided by the OS.

A string resource section in the PE file contains the URL that is used for command and control. The attacker can use the resource section to deploy multiple backdoors to multiple command-and-control locations without needing to recompile the malware.

The attacker abuses the HTTP User-Agent field, which should contain the application information. The malware creates one thread that encodes outgoing information in this field, and another that uses a static field to indicate that it is the “receive” side of the channel.

The initial beacon is an encoded command-shell prompt.

While the attacker encodes outgoing information, he doesn’t encode the incoming commands. Also, because the server must distinguish between the two communication channels via the static elements of the User-Agent fields, this server dependency is apparent and can be targeted with signatures.

The encoding scheme is Base64, but with a custom alphabet.

Communication is terminated using the keyword

exit. When exiting, the malware tries to delete itself.This malware is a small, simple backdoor. Its sole purpose is to provide a command-shell interface to a remote attacker that won’t be detected by common network signatures that watch for outbound command-shell activity. This particular malware is likely a throwaway component of an attacker’s toolkit, which is supported by the fact that the tool tries to delete itself.

We begin by performing dynamic analysis on the malware. The malware initially sends a beacon with an odd User-Agent string:

GET /tenfour.html HTTP/1.1 User-Agent: (!<e6LJC+xnBq90daDNB+1TDrhG6aWG6p9LC/iNBqsGi2sVgJdqhZXDZoMMomKGoqx UE73N9qH0dZltjZ4RhJWUh2XiA6imBriT9/oGoqxmCYsiYG0fonNC1bxJD6pLB/1ndbaS9YXe9710A 6t/CpVpCq5m7l1LCqR0BrWy Host: 127.0.0.1 Cache-Control: no-cache

A short time later, it sends a second beacon:

GET /tenfour.html HTTP/1.1 User-Agent: Internet Surf Host: 127.0.0.1 Cache-Control: no-cache

Note

If you see the initial beacon but not the second one, your problem may be due to the way that you are simulating the server. This particular malware uses two threads, each of which sends HTTP requests to the same server. If one thread fails to get a response, the entire process exits. If you rely on Netcat or some other simple solution for simulating the server, you might get the initial beacon, but when the second beacon fails, the first will quit, too. In order to dynamically analyze this malware, you must use two instances of Netcat or a robust fake server infrastructure such as INetSim.

Multiple trials don’t produce changes in the beacon contents, but modifying the host or user will change the initial encoded beacon, giving us a clue that the source information for the encoded beacon depends on host-specific information.

Beginning with the networking functions, we see imports for InternetOpenA, InternetOpenUrlA, InternetReadFile, and InternetCloseHandle, from the WinINet library. One of the arguments to InternetOpenUrlA is the constant 0x80000000. Looking up the values for the parameter affected, we see that it represents

the INTERNET_FLAG_RELOAD flag. When set, this flag produces the

Cache-Control: no-cache line from the initial beacon, which

demonstrates the advantage of using these higher-level protocols instead of more basic socket calls.

Malware that uses basic socket calls would need to explicitly include the Cache-Control: no-cache string in the code, thereby opening it up to be more easily

identified as malware and to making mistakes in its attempts to imitate legitimate traffic.

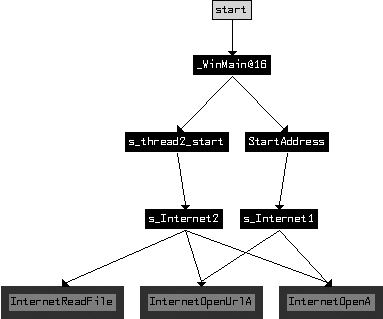

How are the two beacons related? To answer this question, we create a cross-reference graph of all functions that ultimately use the Internet functions, as shown in Figure C-55.

As you can see, the malware has two distinct and symmetric parts. Examining the first call to

CreateThread in WinMain, it is

clear that the function at 0x4014C0, labeled StartAddress, is the

starting address of a new thread. The function at 0x4015CO (labeled s_thread2_start) is also the starting address of a new thread.

Examining StartAddress (0x4014C0), we see that in addition

to the s_Internet1 (0x401750) function, it also calls malloc, PeekNamedPipe, ReadFile, ExitThread, Sleep, and another internal function. The function at s_thread2_start (0x4015CO) contains a similar structure, with calls to

s_Internet2 (0x401800), malloc, WriteFile, ExitThread, and Sleep. The function PeekNamedPipe can be used to watch for new input on a named pipe. (The

stdin and stdout associated with a command shell are both named pipes.)

To determine what is being read from or written to by the two threads, we turn our attention

to WinMain, the source of the threads, as shown in Figure C-55. We see that before WinMain starts the two threads, it calls the functions CreatePipeA, GetCurrentProcess, DuplicateHandle, and CreateProcessA.

The function CreateProcessA creates a new

cmd.exe process, and the other functions set up the new process so that the

stdin and stdout associated with the command process handles are available.

This malware author follows a common pattern for building a reverse command shell. The

attacker has started a new command shell as its own process, and started independent threads to read

the input and write the output to the command shell. The StartAddress (0x4014C0) thread checks for new inputs from the command shell using

PeekNamedPipe, and if content exists, it uses ReadFile to read the data. Once this data is read, it sends the content to

a remote location using the s_Internet1 (0x401750) function. The

other s_thread2_start (0x4015C0) connects to a remote location

using s_Internet2 (0x401800), and if there is any new input for

the command shell, it writes that to the command shell input pipe.

Let’s return to the parameters passed to the Internet functions in s_Internet1 (0x401750) to look for the original sources that make up these

parameters. The function InternetOpenUrlA takes a URL as a

parameter, which we later see passed into the function as an argument and copied to a buffer early

in the function. In the preceding function labeled StartAddress

(0x4014C0), we see that the URL is also an argument. In fact, as we trace the source of the URL, we

must go all the way back to the start of WinMain (0x4011C0) and

the call to LoadStringA. Examining the resource section of the PE

file, we see that it has the URL that was used for beaconing. In fact, this URL is used similarly

for the beacons sent by both threads.

We’ve identified one of the arguments to s_Internet1

(0x401750) as the URL. The other argument is the User-Agent string. Navigating to s_Internet1 (0x401750), we see the static string (!< at the start of the function. This matches the start of the User-Agent string seen

in the beacon, but it is concatenated with a longer string that is passed in as one of the arguments

to s_Internet1 (0x401750). Just before s_Internet1 (0x401750) is called, an internal function at 0x40155B takes two input parameters and outputs the primary content

of the User-Agent string. This encoding function is a custom Base64 variant that uses this Base64

string:

WXYZlabcd3fghijko12e456789ABCDEFGHIJKL+/MNOPQRSTUVmn0pqrstuvwxyz

When the initial beacon string is decoded, the result is as follows:

Microsoft Windows XP [Version 5.1.2600] (C) Copyright 1985-2001 Microsoft Corp. C:\Documents and Settings\user\Desktop>

The other thread uses Internet functions in s_Internet2

(0x401800). As already mentioned, s_Internet2 uses the same URL

parameter as s_Internet1. The User-Agent string in this function

is statically defined as the string Internet Surf.

The s_thread2_start (0x4015C0) thread, as mentioned

earlier, is used to pass inputs to the command shell. It also provides a facility for terminating

the program based on input. If the operator passes the string exit to the malware, the malware will then exit. The code block loc_40166B, located in s_thread2_start (0x4015C0),

contains the reference to the exit string and the strnicmp function that is used to test the incoming network

content.

Note

We could also have used dynamic analysis to gain insight into the malware. The encoding function at 0x40155B could have been identified by the Base64 strings it contains. By setting a breakpoint at the function in a debugger, we would have seen the Windows command prompt as an argument prior to encoding. The encoded command prompt varies a bit based on the specific OS and username, which is why we found this beacon changing based on the host or user.

In summary, each of the two threads handles different ends of the pipes to the command shell. The thread with the static User-Agent string gets the input from the remote attacker, and the thread with the encoded User-Agent string serves as the output for the command shell. This is a clever way for attackers to obfuscate their activities and avoid sending command prompts from the compromised server in the clear.

One piece of evidence that supports the idea that this is a throwaway component for an

attacker is the fact that the malware tries to delete itself when it exits. In WinMain (0x4011C0), there are three possible function endings. The two

early terminations occur when a thread fails to be successfully created. In all three terminal

cases, there is a call to 0x401880. The purpose of 0x401880 is to delete the malware from disk once

the malware exits. 0x401880 implements the ComSpec method of self-deletion. Essentially, the ComSpec

method entails running a ShellExecute command with the ComSpec

environmental variable defined and with the command line /c del

[executable_to_delete] > nul, which is precisely what 0x401880 does.

For signatures other than the URL, we target the static User-Agent field, the static characters of the encoded User-Agent, and the length and character restrictions of the encoded command-shell prompt, as shown in Example C-118.

Example C-118. Snort signatures for Lab 14-2 Solutions

alert tcp $HOME_NET any -> $EXTERNAL_NET $HTTP_PORTS (msg:"PM14.2.1 Suspicious

User-Agent (Internet Surf)"; content: "User-Agent\:|20|Internet|20|Surf";

http_header; sid:20001421; rev:1;)

alert tcp $HOME_NET any -> $EXTERNAL_NET $HTTP_PORTS (msg:"PM14.2.2 Suspicious

User-Agent (starts (!<)"; content: "User-Agent\:|20|(!<"; http_header;

sid:20001422; rev:1;)

alert tcp $HOME_NET any -> $EXTERNAL_NET $HTTP_PORTS (msg:"PM14.2.3 Suspicious

User-Agent (long B64)"; content:"User-Agent\:|20|"; content:!"|20|"; distance:0;

within:100; pcre:"/User-Agent:\x20[^\x0d]{0,5}[A-Za-z0-9+\/]{100,}/";

sid:20001423; rev:1;)In Example C-118, the first two signatures (20001421 and 20001422) are

straightforward, targeting User-Agent header content that should hopefully be uncommon. The last

signature (20001423) targets only the length and character

restrictions of an encoded command-shell prompt, without assuming the existence of the same leading

characters targeted in 20001422. Because the signature is looking

for a less specific pattern, it is more likely to encounter false positives. The PCRE regular

expression searches for the User-Agent header, followed by a string of at least 100 characters from

the Base64 character set, allowing for up to five characters of any value at the start of the

User-Agent (as long as they are not line feeds indicating a new header). The optional five

characters allow a special start to the User-Agent string, such as the (!< seen in the malware. The requirement for 100 characters from the Base64 character

set is loosely based on the expected length of a command prompt.

Finally, the negative content search for a space character is purely to increase the performance of the signature. Most User-Agent strings will have a space character fairly early in the string, so this check will avoid needing to test the regular expression for most User-Agent strings.