Hook injection describes a way to load malware that takes advantage of Windows hooks, which are used to intercept messages destined for applications. Malware authors can use hook injection to accomplish two things:

To be sure that malicious code will run whenever a particular message is intercepted

To be sure that a particular DLL will be loaded in a victim process’s memory space

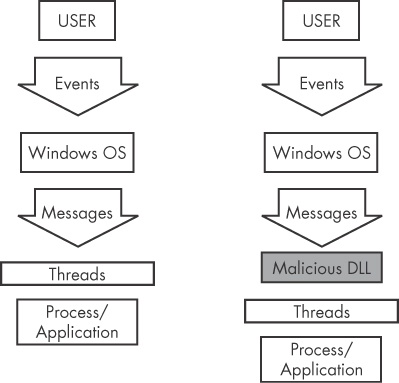

As shown in Figure 12-3, users generate events that are sent to the OS, which then sends messages created by those events to threads registered to receive them. The right side of the figure shows one way that an attacker can insert a malicious DLL to intercept messages.

There are two types of Windows hooks:

Local hooks are used to observe or manipulate messages destined for an internal process.

Remote hooks are used to observe or manipulate messages destined for a remote process (another process on the system).

Remote hooks are available in two forms: high and low level. High-level remote hooks require that the hook procedure be an exported function contained in a DLL, which will be mapped by the OS into the process space of a hooked thread or all threads. Low-level remote hooks require that the hook procedure be contained in the process that installed the hook. This procedure is notified before the OS gets a chance to process the event.

Hook injection is frequently used in malicious applications known as

keyloggers, which record keystrokes. Keystrokes can be captured by registering

high- or low-level hooks using the WH_KEYBOARD or WH_KEYBOARD_LL hook procedure types, respectively.

For WH_KEYBOARD procedures, the hook will often be running

in the context of a remote process, but it can also run in the process that installed the hook. For

WH_KEYBOARD_LL procedures, the events are sent directly to the

process that installed the hook, so the hook will be running in the context of the process that

created it. Using either hook type, a keylogger can intercept keystrokes and log them to a file or

alter them before passing them along to the process or system.

The principal function call used to perform remote Windows hooking is SetWindowsHookEx, which has the following parameters:

idHook. Specifies the type of hook procedure to install.lpfn. Points to the hook procedure.hMod. For high-level hooks, identifies the handle to the DLL containing the hook procedure defined bylpfn. For low-level hooks, this identifies the local module in which thelpfnprocedure is defined.dwThreadId. Specifies the identifier of the thread with which the hook procedure is to be associated. If this parameter is zero, the hook procedure is associated with all existing threads running in the same desktop as the calling thread. This must be set to zero for low-level hooks.

The hook procedure can contain code to process messages as they come in from the system, or it

can do nothing. Either way, the hook procedure must call CallNextHookEx, which ensures that the next hook procedure in the call chain gets the

message and that the system continues to run properly.

When targeting a specific dwThreadId, malware

generally includes instructions for determining which system thread identifier to use, or it is

designed to load into all threads. That said, malware will load into all threads only if it’s

a keylogger or the equivalent (when the goal is message interception). However, loading into all

threads can degrade the running system and may trigger an IPS. Therefore, if the goal is to simply

load a DLL in a remote process, only a single thread will be injected in order to remain

stealthy.

Targeting a single thread requires a search of the process listing for the target process and

can require that the malware run a program if the target process is not already running. If a

malicious application hooks a Windows message that is used frequently, it’s more likely to

trigger an IPS, so malware will often set a hook with a message that is not often used, such as

WH_CBT (a computer-based training message).

Example 12-4 shows the assembly code for performing hook injection in order to load a DLL in a different process’s memory space.

Example 12-4. Hook injection, assembly code

00401100 push esi 00401101 push edi 00401102 push offset LibFileName ; "hook.dll" 00401107 call LoadLibraryA 0040110D mov esi, eax 0040110F push offset ProcName ; "MalwareProc" 00401114 push esi ; hModule 00401115 call GetProcAddress 0040111B mov edi, eax 0040111D callGetNotepadThreadId00401122 push eax ; dwThreadId 00401123 push esi ; hmod 00401124 push edi ; lpfn 00401125 pushWH_CBT; idHook 00401127 callSetWindowsHookExA

In Example 12-4, the malicious DLL

(hook.dll) is loaded by the malware, and the malicious hook procedure address

is obtained. The hook procedure, MalwareProc, calls only CallNextHookEx. SetWindowsHookEx is

then called for a thread in notepad.exe (assuming that

notepad.exe is running). GetNotepadThreadId

is a locally defined function that obtains a dwThreadId for

notepad.exe. Finally, a WH_CBT message is

sent to the injected notepad.exe in order to force

hook.dll to be loaded by notepad.exe. This allows

hook.dll to run in the notepad.exe process space.

Once hook.dll is injected, it can execute the full malicious code stored

in DllMain, while disguised as the

notepad.exe process. Since MalwareProc calls

only CallNextHookEx, it should not interfere with incoming

messages, but malware often immediately calls LoadLibrary and

UnhookWindowsHookEx in DllMain

to ensure that incoming messages are not impacted.