The exports are

InstallRT,InstallSA,InstallSB,PSLIST,ServiceMain,StartEXS,UninstallRT,UninstallSA, andUninstallSB.The DLL is deleted from the system using a .bat file.

A .bat file containing self-deletion code is created, as well as a file named xinstall.log containing the string

"Found Virtual Machine, Install Cancel".This malware queries the VMware backdoor I/O communication port using the magic value

VXand the action0xAby using theinx86 instruction.To get the malware to install, patch the

ininstruction at 0x100061DB at runtime.To permanently disable the VM check, use a hex editor to modify the static string in the binary from

[This is DVM]5to[This is DVM]0. Alternatively, NOP-out the check in OllyDbg and write the change to disk.InstallRTperforms installation via DLL injection with an optional parameter containing the process to inject into.InstallSAperforms installation via service installation.InstallSBperforms installation via service install and DLL injection if the service to overwrite is still running.

Lab 17-2 Solutions is an extensive piece of malware. Our goal with this lab is to demonstrate how anti-VM techniques can slow your efforts to analyze malware. We’ll focus our discussion on disabling and understanding the anti-VM aspects of the malware. We leave the task of fully reversing the malware in this sample to you.

Begin by loading the malware into PEview to examine its exports and imports. The

malware’s extensive import list suggests that it has a wide range of functionality, including

functions for manipulating the registry (RegSetValueEx),

manipulating services (ChangeService), screen capturing (BitBlt), process listing (CreateToolhelp32Snapshot), process injection (CreateRemoteThread), and networking functionality (WS2_32.dll). We also see a set of export functions, mostly related to installation or

removal of the malware, as shown here:

InstallRT InstallSA InstallSB PSLIST ServiceMain StartEXS UninstallRT UninstallSA UninstallSB

The ServiceMain function in the export list tells us that

this malware probably can be run as a service. The names of the installation exports that end in the

strings SA and SB may be the

methods related to service installation.

We attempt to run this malware and monitor it using dynamic analysis techniques. Using procmon, we set a filter on rundll32.exe (since we will use it to run the malware from the command line), and then run the following from the command line within our VM:

rundll32.exe Lab17-02.dll,InstallRT

We immediately notice that the malware is deleted from the system and a file

xinstall.log is left behind. This file contains the string "Found Virtual Machine, Install Cancel", which means that there is an

anti-VM technique in the binary.

Note

You will sometimes encounter logging capability in real malware because logging errors can help malware authors determine what they need to change in order for their attack to succeed. Also, by logging the result of the various system configurations they encounter, such as VMs, attackers can identify issues they may encounter during an attack.

When we check our procmon output, we see that the malware created the file

vmselfdel.bat for the malware to delete itself. When we load the malware into

IDA Pro and follow the cross-references back from the vmselfdel.bat string, we reach sub_10005567, which

shows the self-deletion scripting code that is written to the .bat file.

Next, we focus on determining why the malware deleted itself. We can use the

findAntiVM.py script from the previous lab or work backward through the code by

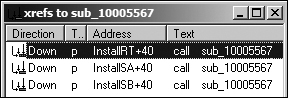

examining the cross-references to sub_10005567 (the

vmselfdel.bat creation method). Let’s examine the cross-references, as

shown in Figure C-64.

As you can see in Figure C-64, there are three

cross-references to this function, each of which is located in a different export from the malware.

Following the cross-reference to InstallRT, we see the code shown

in Example C-161 in the InstallRT export function.

Example C-161. Anti-VM check inside InstallRT

1000D870 push offset unk_1008E5F0 ; char *

1000D875 ❸call sub_10003592

1000D87A ❷mov [esp+8+var_8], offset aFoundVirtualMa ; "Found Virtual Machine,..."

1000D881 ❹call sub_10003592

1000D886 pop ecx

1000D887 ❶call sub_10005567

1000D88C jmp short loc_1000D8A4The call at ❶ is to the vmselfdel.bat function. At ❷, we see a

reference to the string we found earlier in xinstall.log, as shown in bold.

Examining the functions at ❸ and ❹, we see that ❸ opens

xinstall.log and ❹ logs "Found Virtual Machine, Install Cancel"

to the file.

Examining the code section shown in Example C-161 in graph

mode, we see two code paths to it, both conditional jumps after the calls to sub_10006119 or sub_10006196. Because

the function sub_10006119 is empty, we know that sub_10006196 must contain our anti-VM technique. Example C-162 shows a subset of the instructions from

sub_10006196.

Example C-162. Querying the I/O communication port

100061C7 mov eax, 564D5868h ;'VMXh' ❸ 100061CC mov ebx, 0 100061D1 mov ecx, 0Ah 100061D6 mov edx, 5658h ;'VX' ❷ 100061DB in eax, dx ❶ 100061DC cmp ebx, 564D5868h ;'VMXh' ❹ 100061E2 setz [ebp+var_1C] ... 100061FA mov al, [ebp+var_1C]

The malware is querying the I/O communication port (0x5668) using the in instruction at ❶. (VMware uses the virtual

I/O port for communication between the VM and the host OS.) This VMware port is loaded into EDX at

❷, and the action performed is loaded into ECX in the

previous instruction. In this case, the action is 0xA, which

means “get VMware version type.” EAX is loaded with the magic number 0x564d5868

(VMXh) at ❸, and the

malware checks that the magic number is echoed back immediately after the in instruction with the cmp at ❹. The result of the comparison is moved into var_1C, and is ultimately moved into AL as sub_10006196’s return value.

This malware doesn’t appear to care about the VMware version. It just wants to see if

the I/O communication port echoes back with the magic value. At runtime, we can bypass the backdoor

I/O communication port technique by replacing the in instruction

with a NOP. Inserting the NOP allows the program to complete installation.

Before further analyzing the imports dynamically, let’s continue to examine the InstallRT export. The code in Example C-163 is taken from the start of the InstallRT export. The jz instruction at

❶ determines if the anti-VM check will be

performed.

Example C-163. Checking the DVM static configuration option

1000D847 mov eax, off_10019034 ;[This is DVM]51000D84C push esi 1000D84D mov esi, ds:atoi 1000D853 add eax, 0Dh ❷ 1000D856 push eax ; Str 1000D857 call esi ;atoi1000D859 test eax, eax ❸ 1000D85B pop ecx 1000D85C jz short loc_1000D88E ❶

The code uses atoi (shown in bold) to turn a string

into a number. The number is parsed out of the string [This is

DVM]5 (also shown in bold). The reference to [This is

DVM]5 is loaded into EAX, and EAX is advanced by 0xD at ❷, which moves the string pointer to the 5 character,

which is turned into the number 5 with the call to atoi. The test

at ❸ checks to see if the number parsed is 0.

Note

DVM is a static configuration option. If we open the malware in a hex editor, we can

manually change the string to read [This is DVM]0, and the

malware will no longer perform the anti-VM check.

The following excerpt shows a subset of the static configuration options in

Lab17-02.exe, with a domain name and port 80 shown in bold. The LOG option (also shown in bold) is probably used by the malware to

determine if xinstall.log should be created and used.

[This is RNA]newsnews [This is RDO]newsnews.practicalmalwareanalysis.com [This is RPO]80 [This is DVM]5 [This is SSD] [This is LOG]1

We’ll complete our analysis of InstallRT by analyzing

the method sub_1000D3D0. This method is long, but all of its

imported functions and logging strings make the analysis process much easier.

The sub_1000D3D0 method begins by copying the malware into

the Windows system directory. As shown in Example C-164, InstallRT takes an optional argument. The strlen at ❶ checks the string

length of the argument. If the string length is 0 (meaning no argument), iexplore.exe is used (shown in bold).

Example C-164. Argument used as the target process name with iexplore.exe

as the default

1000D50E push [ebp+process_name] ; Str

1000D511 call strlen ❶

1000D516 test eax, eax

1000D518 pop ecx

1000D519 jnz short loc_1000D522

1000D51B push offset aIexplore_exe ; "iexplore.exe"The export argument (or iexplore.exe) is used as a target

process for DLL injection of this malware. At 0x1000D53A, the malware calls a function to find the

target process in the process listing. If the process is found, the malware uses the process’s

PID in the call to sub_1000D10D, which uses a common process

injection trio of calls: VirtualAllocEx, WriteProcessMemory, and CreateRemoteThread. We conclude that InstallRT performs

DLL injection to launch the malware, which we confirm by running the malware (after patching the

static DVM option) and using Process Explorer to see the DLL load into another process.

Next, we focus on the InstallSA export, which has the

same high-level structure as InstallRT. Both exports check the

DVM static configuration option before performing the anti-VM checks. The only difference between

the two is that InstallSA calls sub_1000D920 for its main functionality.

Examining sub_1000D920, we see that it takes an optional

argument (by default Irmon). This function creates a service at

0x1000DBC4 if you specify a service name in the Svchost Netsvcs group, or it creates the Irmon

service if you don’t specify a service name. The service is set with a blank description and a

display name of X System Services, where X is the service

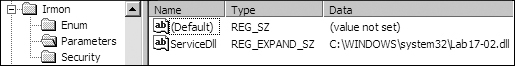

name. After creating the service, InstallSA sets the

ServiceDLL path to this malware in the Windows system directory. We confirm

this by performing dynamic analysis and using rundll32.exe to call the InstallSA function. We use Regedit to look at the Irmon service in the

registry and see the change shown in Figure C-65.

Because the InstallSA method doesn’t copy the malware

to the Windows system directory, this installation method fails to install the malware.

Finally, we focus on the InstallSB export, which has the

same high-level structure as InstallSA and InstallRT. All three exports check the DVM static configuration option

before performing the anti-VM check. InstallSB calls sub_1000DF22 for its main functionality and contains an extra call to

sub_10005A0A. The function sub_10005A0A disables Windows File Protection using the method discussed in Lab 12-4 Solutions.

The sub_1000DF22 function appears to contain functionality

from both InstallSA and InstallRT. InstallSB also takes an optional argument

containing a service name (by default NtmsSvc) that the malware uses to overwrite a service on the

local system. In the default case, the malware stops the NtmsSvc service if it is running and

overwrites ntmssvc.dll in the Windows system directory with itself. The malware

then attempts to start the service again. If the malware cannot start the service, the malware

performs DLL injection, as seen with the call at 0x1000E571. (This is similar to how InstallRT works, except InstallSB

injects into svchost.exe.) InstallSB also

saves the old service binary, so that UninstallSB can restore it

if necessary.

We’ll leave the full analysis of this malware to you, since our focus here is on anti-VM techniques. This malware is an extensive backdoor with considerable functionality, including keylogging, capturing audio and video, transferring files, acting as a proxy, retrieving system information, using a reverse command shell, injecting DLLs, and downloading and launching commands.

To fully analyze this malware, analyze its export functions and static configuration options before focusing on the backdoor network communication capability. See if you can write a script to decode network traffic generated by this malware.