The functions at 0x401000 and 0x401040 are the same as those in Lab 6-2 Solutions. At 0x401271 is

printf. The 0x401130 function is new to this lab.The new function takes two parameters. The first is the command character parsed from the HTML comment, and the second is the program name

argv[0], the standardmainparameter.The new function contains a

switchstatement with a jump table.The new function can print error messages, delete a file, create a directory, set a registry value, copy a file, or sleep for 100 seconds.

The registry key

Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\Malwareand the file location C:\Temp\cc.exe can both be host-based indicators.The program first checks for an active Internet connection. If no Internet connection is found, the program terminates. Otherwise, the program will attempt to download a web page containing an embedded HTML comment beginning with

<!--. The first character of the comment is parsed and used in aswitchstatement to determine which action to take on the local system, including whether to delete a file, create a directory, set a registry run key, copy a file, or sleep for 100 seconds.

We begin by performing basic static analysis on the binary and find several new strings of interest, as shown in Example C-6.

Example C-6. Interesting new strings contained in Lab 6-3 Solutions

Error 3.2: Not a valid command provided Error 3.1: Could not set Registry value Malware Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run C:\Temp\cc.exe C:\Temp

These error messages suggest that the program may be able to modify the registry. Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run is a common autorun location

in the registry. C:\Temp\cc.exe is a directory and filename that may be useful

as a host-based indicator.

Looking at the imports, we see several new Windows API functions not found in Lab 6-2 Solutions, as shown in Example C-7.

Example C-7. Interesting new import functions contained in Lab 6-3 Solutions

DeleteFileA CopyFileA CreateDirectoryA RegOpenKeyExA RegSetValueExA

The first three imports are self-explanatory. The RegOpenKeyExA function is typically used with RegSetValueExA to insert information into the registry, usually when the malware sets

itself or another program to start on system boot for the sake of persistence. (We discuss the

Windows registry in depth in Chapter 7.)

Next, we perform dynamic analysis, but find that it isn’t very fruitful (not surprising based on what we discovered in Lab 6-2 Solutions). We could connect the malware directly to the Internet or use INetSim to serve web pages to the malware, but we wouldn’t know what to put in the HTML comment. Therefore, we need to perform more in-depth analysis by looking at the disassembly.

Finally, we load the executable into IDA Pro. The main

method looks nearly identical to the one from Lab 6-2 Solutions, except there is

an extra call to 0x401130. The calls to 0x401000 (check Internet connection) and 0x401040 (download

web page and parse HTML comment) are identical to those in Lab 6-2 Solutions.

Next, we examine the parameters passed to 0x401130. It looks like argv and var_8 are pushed onto the stack before the

call. In this case, argv is Argv[0], a reference to a string containing the current program’s name,

Lab06-03.exe. Examining the disassembly, we see that var_8 is set to AL at 0x40122D. Remember that EAX is the return value from the previous

function call, and that AL is contained within EAX. In this case, the previous function call

is 0x401040 (download web page and parse HTML comment). Therefore, var_8 is passed to 0x401130 containing the command character parsed from

the HTML comment.

Now that we know what is passed to the function at 0x401130, we can analyze it. Example C-8 is from the start of the function.

Example C-8. Analyzing the function at 0x401130

00401136 movsx eax, [ebp+arg_0] 0040113A mov [ebp+var_8], eax 0040113D mov ecx, [ebp+var_8] ❶ 00401140 sub ecx, 61h 00401143 mov [ebp+var_8], ecx 00401146 cmp [ebp+var_8], 4 ❷ 0040114A ja loc_4011E1 00401150 mov edx, [ebp+var_8] 00401153 jmp ds:off_4011F2[edx*4] ❸ ... 004011F2 off_4011F2 dd offset loc_40115A ❹ 004011F6 dd offset loc_40116C 004011FA dd offset loc_40117F 004011FE dd offset loc_40118C 00401202 dd offset loc_4011D4

arg_0 is an automatic label from IDA Pro that lists the

last parameter pushed before the call; therefore, arg_0 is the

parsed command character retrieved from the Internet. The parsed command character is moved into

var_8 and eventually loaded into ECX at ❶. The next instruction subtracts 0x61 (the letter

a in ASCII) from ECX. Therefore, once this instruction executes, ECX will equal

0 when arg_0 is equal to a.

Next, a comparison to the number 4 at ❷ checks to

see if the command character (arg_0) is a, b, c, d, or e. Any other result will force

the ja instruction to leave this section of code. Otherwise, we

see the parsed command character used as an index into the jump table at ❸.

The EDX is multiplied by 4 at ❸ because the jump

table is a set of memory addresses referencing the different possible paths, and each memory address

is 4 bytes in size. The jump table at ❹ has five

entries, as expected. A jump table like this is often used by a compiler when generating assembly

for a switch statement, as described in Chapter 6.

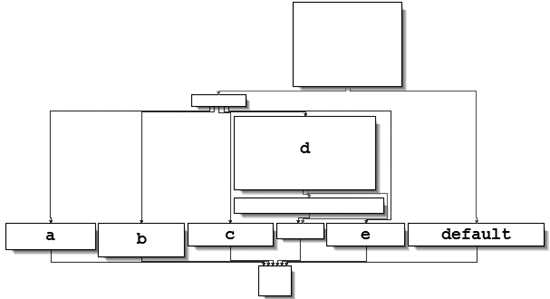

Now let’s look at the graphical view of this function, as shown in Figure C-20. We see six possible paths through the code,

including five cases and the default. The “jump above 4” instruction takes us down the

default path; otherwise, the jump table causes an execution path of the a through e branches. When you see a graph like the

one in the figure (a single box going to many different boxes), you should suspect a switch statement. You can confirm that suspicion by looking at the code

logic and jump table.

Next, we will examine each of the switch options (a

through e) individually.

The

aoption callsCreateDirectorywith the parameterC:\\Temp, to create the path if it doesn’t already exist.The

boption callsCopyFile, which takes two parameters: a source and a destination file. The destination isC:\\Temp\\cc.exe. The source is a parameter passed to this function, which, based on our earlier analysis, we know to be the program name (Argv[0]). Therefore, this option would copy Lab06-03.exe to C:\Temp\cc.exe.The

coption callsDeleteFilewith the parameterC:\\Temp\\cc.exe, which deletes that file if it exists.The

doption sets a value in the Windows registry for persistence. Specifically, it setsSoftware\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\Malwareto C:\Temp\cc.exe, which makes the malware start at system boot (if it is first copied to the Temp location).The

eoption sleeps for 100 seconds.Finally, the default option prints “Error 3.2: Not a valid command provided.”

Having analyzed this function fully, we can combine it with our analysis from Lab 6-2 Solutions to gain a strong understanding of how the overall program operates.

We now know that the program checks for an active Internet connection using the if construct.

If there is no valid Internet connection, the program terminates. Otherwise, the program attempts to

download a web page that contains an embedded HTML comment starting with <!--. The next character is parsed from this comment and used in a switch statement to determine which action to take on the local system:

delete a file, create a directory, set a registry run key, copy a file, or sleep for 100

seconds.