Shellcode exists as a binary blob that gains execution. It must do something useful once it gains execution, which usually means interacting with the system through APIs.

Remember that shellcode cannot use the Windows loader to ensure that all required libraries

are loaded and available, and to make sure that all external symbols are resolved. Instead, it must

find the symbols itself. The shellcode in the previous examples used hard-coded addresses to find

the symbols, but this very fragile method will work only on a specific version of an OS and service

pack. Shellcode must dynamically locate the functions in order to work reliably in different

environments, and for that task, it typically uses LoadLibraryA

and GetProcAddress.

LoadLibraryA loads the specified library and returns a

handle. The GetProcAddress function searches the library’s

exports for the given symbol name or ordinal number. If shellcode has access to these two functions,

it can load any library on the system and find exported symbols, at which point it has full access

to the API.

Both functions are exported from kernel32.dll, so the shellcode must do the following:

Find kernel32.dll in memory.

Parse kernel32.dll’s PE file and search the exported functions for

LoadLibraryAandGetProcAddress.

In order to locate kernel32.dll, we’ll follow a series of undocumented Windows structures. One of these structures contains the load address of kernel32.dll.

Note

Most of the Windows structures are listed on the Microsoft Developer Network (MSDN) site, but they are not fully documented. Many contain byte arrays named Reserved, with the warning “This structure may be altered in future versions of Windows.” For full listings of these structures, see http://undocumented.ntinternals.net/.

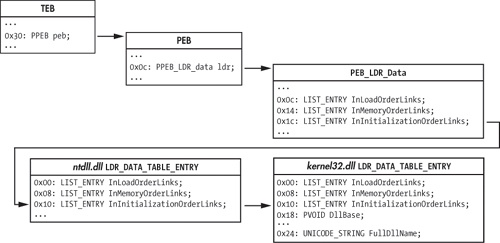

Figure 19-1 shows the data structures that are typically followed in order to find the base address for kernel32.dll (only relevant fields and offsets within each structure are shown).

The process begins with the TEB, accessible from the FS segment register. Offset 0x30 within

the TEB is the pointer to the PEB. Offset 0xc within the PEB is the pointer to the PEB_LDR_DATA structure, which contains three doubly linked lists of

LDR_DATA_TABLE structures—one for each loaded module. The

DllBase field in the kernel32.dll entry is

the value we’re seeking.

Three LIST_ENTRY structures link the LDR_DATA_TABLE entries together in different orders, by name. The InInitializationOrderLinks entry is typically followed by shellcode. From

Windows 2000 through Vista, kernel32.dll is the second DLL initialized, just

after ntdll.dll, which means that the second entry in the InInitializationOrderLinks list of structures should belong to

kernel32.dll. However, beginning with Windows 7,

kernel32.dll is no longer the second module to be initialized, so this simple

algorithm no longer works. Portable shellcode will instead need to examine the UNICODE_STRING

FullDllName field to confirm it is

kernel32.dll.

When traversing the LIST_ENTRY structures, it is important

to realize that the Flink and Blink pointers point to the equivalent LIST_ENTRY in

the next and previous LDR_DATA_TABLE structures. This means that

when following the InInitializationOrderLinks to get to

kernel32.dll’s LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY,

you need to add only eight to the pointer to get the DllBase,

instead of adding 0x18, which you would have to do if the pointer pointed to the start of the

structure.

Example 19-4 contains sample assembly code that finds the base address of kernel32.dll.

Example 19-4. findKernel32Base implementation

; __stdcall DWORD findKernel32Base(void);

findKernel32Base:

push esi

xor eax, eax

mov eax, [fs:eax+0x30] ❶ ; eax gets pointer to PEB

test eax, eax ; if high bit set: Win9x

js .kernel32_9x ❷

mov eax, [eax + 0x0c] ❹ ; eax gets pointer to PEB_LDR_DATA

;esi gets pointer to 1st

;LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY.InInitializationOrderLinks.Flink

mov esi, [eax + 0x1c]

;eax gets pointer to 2nd

;LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY.InInitializationOrderLinks.Flink

lodsd ❺

mov eax, [eax + 8] ; eax gets LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY.DllBase

jmp near .finished

.kernel32_9x:

jmp near .kernel32_9x ❸ ; Win9x not supported: infinite loop

.finished:

pop esi

retThe listing accesses the TEB using the FS segment register at ❶ to get the pointer to the PEB. The js (jump if

signed) instruction at ❷ is used to test whether the

most significant bit of the PEB pointer is set, in order to differentiate between Win9x and WinNT

systems. In WinNT (including Windows 2000, XP, and Vista), the most significant bit of the PEB

pointer is typically never set, because high memory addresses are reserved for the OS. Using the

sign bit to identify the OS family fails on systems that use the /3GB boot option, which causes the user-level/kernel-level memory split to occur at

0xC0000000 instead of 0x8000000, but this is ignored for this simple example. This shellcode chose

not to support Win9x, so it enters an infinite loop at ❸

if Win9x is detected.

The shellcode proceeds to PEB_LDR_DATA at ❹. It assumes that it is running under Windows Vista or earlier,

so it can simply retrieve the second LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY in the

InInitializationOrderLinks linked list at ❺ and return its DllBase

field.

Once you find the base address for kernel32.dll, you must parse it to find exported symbols. As with finding the location of kernel32.dll, this process involves following several structures in memory.

PE files use relative virtual addresses (RVAs) when defining locations within a file. These addresses can be thought of as offsets within the PE image in memory, so the PE image base address must be added to each RVA to turn it into a valid pointer.

The export data is stored in IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY. An RVA

to this is stored in the array of IMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY structures

at the end of the IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER. The location of the

IMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY array depends on whether the PE file is for

a 32-bit application or a 64-bit application. Typical shellcode assumes it is running on a 32-bit

platform, so it knows at compile time that the correct offset from the PE signature to the directory

array is as follows:

sizeof(PE_Signature) + sizeof(IMAGE_FILE_HEADER) + sizeof(IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER) = 120 bytes

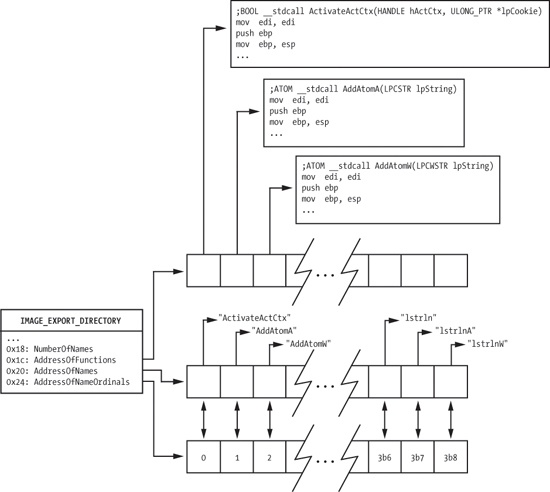

The relevant fields in the IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY structure

are shown in Figure 19-2. AddressOfFunctions is an array of RVAs that points to the actual export functions. It is

indexed by an export ordinal (an alternative way of finding an exported symbol).

The shellcode needs to map the export name to the ordinal in order to use this array, and it

does so using the AddressOfNames and AddressOfNameOrdinals arrays. These two arrays exist in parallel. They have the same

number of entries, and equivalent indices into these arrays are directly related. AddressOfNames is an array of 32-bit RVAs that point to the strings of

symbol names. AddressOfNameOrdinals is an array of 16-bit

ordinals. For a given index idx into these arrays, the symbol at

AddressOfNames[idx] has the export ordinal value at AddressOfNameOrdinals[idx]. The AddressOfNames array is sorted alphabetically so that a binary search can quickly find a

specific string, though most shellcode simply performs a linear search starting at the beginning of

the array.

To find the export address of a symbol, follow these steps:

Iterate over the

AddressOfNamesarray looking at eachchar*entry, and perform a string comparison against the desired symbol until a match is found. Call this index intoAddressOfNamesiName.Index into the

AddressOfNameOrdinalsarray usingiName. The value retrieved is the valueiOrdinal.Use

iOrdinalto index into theAddressOfFunctionsarray. The value retrieved is the RVA of the exported symbol. Return this value to the requester.

A sample implementation of this algorithm is shown later in the chapter as part of a full Hello World example.

Once the shellcode finds LoadLibraryA, it can load

arbitrary libraries. The return value of LoadLibraryA is treated

as a HANDLE in the Win32 API. Examining the HANDLE values shows that it is actually a 32-bit pointer to the dllBase of the library that was loaded, which means that the shellcode can

skip using GetProcAddress and continue using its own PE parsing

code with the dllBase pointers returned from LoadLibraryA (which is also beneficial when hashed names are used, as

explained in the next section).

The algorithm just discussed has a weakness: It performs a strcmp against each export name until it finds the correct one. This requires that the

full name of each API function the shellcode uses be included as an ASCII string. When the size of

the shellcode is constrained, these strings could push the size of the shellcode over the

limit.

A common way to address this problem is to calculate a hash of each symbol string and compare the result with a precomputed value stored in the shellcode. The hash function does not need to be sophisticated; it only needs to guarantee that within each DLL used by the shellcode, the hashes that the shellcode uses are unique. Hash collisions between symbols in different DLLs and between symbols the shellcode does not use are fine.

The most common hash function is the 32-bit rotate-right-additive hash, as shown in Example 19-5.

Example 19-5. hashString implementation

; __stdcall DWORD hashString(char* symbol);

hashString:

push esi

push edi

mov esi, dword [esp+0x0c] ; load function argument in esi

.calc_hash:

xor edi, edi ❶

cld

.hash_iter:

xor eax, eax

lodsb ❷ ; load next byte of input string

cmp al, ah

je .hash_done ; check if at end of symbol

ror edi, 0x0d ❸ ; rotate right 13 (0x0d)

add edi, eax

jmp near .hash_iter

.hash_done:

mov eax, edi

pop edi

pop esi

retn 4This function calculates a 32-bit DWORD hash value of the

string pointer argument. The EDI register is treated as the current hash value, and is initialized

to zero at ❶. Each byte of the input string is loaded

via the lodsb instruction at ❷. If the byte is not NULL, the current hash is rotated right by 13 (0x0d) at ❸, and the current

byte is added into the hash. This hash is returned in EAX so that its caller can compare the result

with the value compiled into the code.

Note

The particular algorithm in Example 19-5 has become commonly used due to its inclusion in Metasploit, but variations that use different rotation amounts and hash sizes are sometimes seen.