The virtual machine monitor program monitors the virtual machine’s execution. It runs on the host operating system to present the guest operating system with a virtual platform. It also has a couple of security weaknesses that can allow malware to detect virtualization.

Note

The x86 instruction-related issues in virtual machines discussed in this section were originally outlined in the USENIX 2000 paper “Analysis of the Intel Pentium’s Ability to Support a Secure Virtual Machine Monitor” by John Robin and Cynthia Irvine.

In kernel mode, VMware uses binary translation for emulation. Certain privileged instructions in kernel mode are interpreted and emulated, so they don’t run on the physical processor. Conversely, in user mode, the code runs directly on the processor, and nearly every instruction that interacts with hardware is either privileged or generates a kernel trap or interrupt. VMware catches all the interrupts and processes them, so that the virtual machine still thinks it is a regular machine.

Some instructions in x86 access hardware-based information but don’t generate

interrupts. These include sidt, sgdt, sldt, and cpuid, among others. In order to virtualize these instructions properly, VMware would

need to perform binary translation on every instruction (not just kernel-mode instructions),

resulting in a huge performance hit. To avoid huge performance hits from doing full-instruction

emulation, VMware allows certain instructions to execute without being properly virtualized.

Ultimately, this means that certain instruction sequences will return different results when running

under VMware than they will on native hardware.

The processor uses certain key structures and tables, which are loaded at different offsets as a side effect of this lack of full translation. The interrupt descriptor table (IDT) is a data structure internal to the CPU, which is used by the operating system to determine the correct response to interrupts and exceptions. Under x86, all memory accesses pass through either the global descriptor table (GDT) or the local descriptor table (LDT). These tables contain segment descriptors that provide access details for each segment, including the base address, type, length, access rights, and so on. IDT (IDTR), GDT (GDTR), and LDT (LDTR) are the internal registers that contain the address and size of these respective tables.

Note that operating systems do not need to utilize these tables. For example, Windows implements a flat memory model and uses only the GDT by default. It does not use the LDT.

Three sensitive instructions—sidt, sgdt, and sldt—read the location

of these tables, and all store the respective register into a memory location. While these

instructions are typically used by the operating system, they are not privileged in the x86

architecture, and they can be executed from user space.

An x86 processor has only three registers to store the locations of these three tables.

Therefore, these registers must contain values valid for the underlying host operating system and

will diverge from values expected by the virtualized (guest) operating system. Since the sidt, sgdt, and sldt instructions can be invoked at any time by user-mode code without

being trapped and properly virtualized by VMware, they can be used to detect its presence.

Red Pill is an anti-VM technique that executes the sidt

instruction to grab the value of the IDTR register. The virtual machine monitor must relocate the

guest’s IDTR to avoid conflict with the host’s IDTR. Since the virtual machine monitor

is not notified when the virtual machine runs the sidt

instruction, the IDTR for the virtual machine is returned. The Red Pill tests for this discrepancy

to detect the usage of VMware.

Example 17-2 shows how Red Pill might be used by malware.

Example 17-2. Red Pill in malware

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

sub esp, 454h

push ebx

push esi

push edi

push 8 ; Size

push 0 ; Val

lea eax, [ebp+Dst]

push eax ; Dst

call _memset

add esp, 0Ch

lea eax, [ebp+Dst]

❶ sidt fword ptr [eax]

mov al, [eax+5]

cmp al, 0FFh

jnz short loc_401E19The malware issues the sidt instruction at ❶, which stores the contents of IDTR into the memory location

pointed to by EAX. The IDTR is 6 bytes, and the fifth byte offset contains the start of the base

memory address. That fifth byte is compared to 0xFF, the VMware signature.

Red Pill succeeds only on a single-processor machine. It won’t work consistently against

multicore processors because each processor (guest or host) has an IDT assigned to it. Therefore,

the result of the sidt instruction can vary, and the signature

used by Red Pill can be unreliable.

To thwart this technique, run on a multicore processor machine or simply NOP-out the sidt instruction.

The sgdt and sldt

instruction technique for VMware detection is commonly known as No Pill. Unlike Red Pill, No Pill

relies on the fact that the LDT structure is assigned to a processor, not an operating system. And

because Windows does not normally use the LDT structure, but VMware provides virtual support for it,

the table will differ predictably: The LDT location on the host machine will be zero, and on the

virtual machine, it will be nonzero. A simple check for zero against the result of the sldt instruction does the trick.

The sldt method can be subverted in VMware by disabling

acceleration. To do this, select VM ▶ Settings ▶ Processors and check

the Disable Acceleration box. No Pill solves this acceleration

issue by using the smsw instruction if the sldt method fails. This method involves inspecting the undocumented

high-order bits returned by the smsw instruction.

Perhaps the most popular anti-VMware technique currently in use is that of querying the I/O communication port. This technique is frequently encountered in worms and bots, such as the Storm worm and Phatbot.

VMware uses virtual I/O ports for communication between the virtual machine and the host operating system to support functionality like copy and paste between the two systems. The port can be queried and compared with a magic number to identify the use of VMware.

The success of this technique depends on the x86 in

instruction, which copies data from the I/O port specified by the source operand to a memory

location specified by the destination operand. VMware monitors the use of the in instruction and captures the I/O destined for the communication channel

port 0x5668 (VX). Therefore, the second operand needs to be

loaded with VX in order to check for VMware, which happens only

when the EAX register is loaded with the magic number 0x564D5868

(VMXh). ECX must be loaded with a value corresponding to the

action you wish to perform on the port. The value 0xA means

“get VMware version type,” and 0x14 means “get

the memory size.” Both can be used to detect VMware, but 0xA is more popular because it may determine the VMware version.

Phatbot, also known as Agobot, is a botnet that is simple to use. One of its features is its built-in support of the I/O communication port technique, as shown in Example 17-3.

Example 17-3. Phatbot’s VMware detection

004014FA push eax 004014FB push ebx 004014FC push ecx 004014FD push edx 004014FE mov eax, 'VMXh' ❶ 00401503 mov ebx, [ebp+var_1C] 00401506 mov ecx, 0xA 00401509 mov dx, 'VX' ❷ 0040150E in eax, dx 0040150F mov [ebp+var_24], eax 00401512 mov [ebp+var_1C], ebx 00401515 mov [ebp+var_20], ecx 00401518 mov [ebp+var_28], edx ... 0040153E mov eax, [ebp+var_1C] 00401541 cmp eax, 'VMXh' ❸ 00401546 jnz short loc_40155C

The malware first loads the magic number 0x564D5868

(VMXh) into the EAX register at ❶. Next, it loads the local variable var_1c into EBX,

a memory address that will return any reply from VMware. ECX is loaded with the value 0xA to get the VMware version type. At ❷, 0x5668 (VX) is

loaded into DX, to be used in the following in instruction to

specify the VMware I/O communication port.

Upon execution, the in instruction is trapped by the

virtual machine and emulated to execute it. The in instruction

uses parameters of EAX (magic value), ECX (operation), and EBX (return information). If the magic

value matches VMXh and the code is running in a virtual machine,

the virtual machine monitor will echo that back in the memory location specified by the EBX

register.

The check at ❸ determines whether the code is being run in a virtual machine. Since the get version type option is selected, the ECX register will contain the type of VMware (1=Express, 2=ESX, 3=GSX, and 4=Workstation).

The easiest way to overcome this technique is to NOP-out the in instruction or to patch the conditional jump to allow it regardless of the outcome of

the comparison.

The str instruction retrieves the segment selector from the

task register, which points to the task state segment (TSS) of the currently executing task. Malware

authors can use the str instruction to detect the presence of a

virtual machine, since the values returned by the instruction may differ on the virtual machine

versus a native system. (This technique does not work on multiprocessor hardware.)

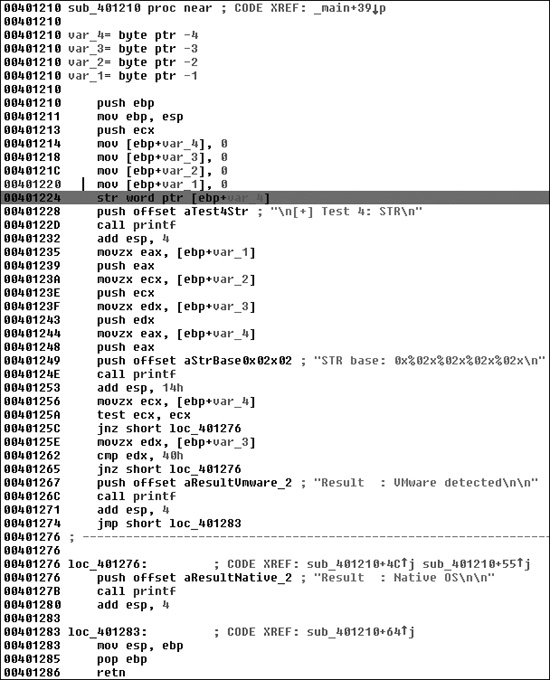

Figure 17-2 shows the str instruction at 0x401224 in malware known as SNG.exe. This loads

the TSS into the 4 bytes: var_1 through var_4, as labeled by IDA Pro. Two comparisons are made at 0x40125A and 0x401262 to

determine if VMware is detected.

We’ve just reviewed the most common instructions used by malware to employ anti-VM techniques. These instructions are as follows:

sidtsgdtsldtsmswstrin(with the second operand set toVX)cpuid

Malware will not typically run these instructions unless it is performing VMware detection, and avoiding this detection can be as easy as patching the binary to avoid calling these instructions. These instructions are basically useless if executed in user mode, so if you see them, they’re likely part of anti-VMware code. VMware describes roughly 20 instructions as “not virtualizable,” of which the preceding are the most commonly used by malware.

You can search for the instructions listed in the previous section in IDA Pro using the IDAPython script shown in Example 17-4. This script looks for the instructions, highlights any in red, and prints the total number of anti-VM instructions found in IDA’s output window.

Figure 17-2 shows a partial result of running this

script against SNG.exe with one location (str at 0x401224) highlighted by the bar. Examining the highlighted code in IDA Pro will

allow you to quickly see if the instruction found is involved in an anti-VM technique. Further

investigation shows that the str instruction is being used to

detect VMware.

Example 17-4. IDA Pro script to find anti-VM instructions

from idautils import *

from idc import *

heads = Heads(SegStart(ScreenEA()), SegEnd(ScreenEA()))

antiVM = []

for i in heads:

if (GetMnem(i) == "sidt" or GetMnem(i) == "sgdt" or GetMnem(i) == "sldt" or

GetMnem(i) == "smsw" or GetMnem(i) == "str" or GetMnem(i) == "in" or

GetMnem(i) == "cpuid"):

antiVM.append(i)

print "Number of potential Anti-VM instructions: %d" % (len(antiVM))

for i in antiVM:

SetColor(i, CIC_ITEM, 0x0000ff)

Message("Anti-VM: %08x\n" % i)ScoopyNG (http://www.trapkit.de/) is a free VMware detection tool that implements seven different checks for a virtual machine, as follows:

The first three checks look for the

sidt,sgdt, andsldt(Red Pill and No Pill) instructions.The fourth check looks for

str.The fifth and sixth use the backdoor I/O port

0xaand0x14options, respectively.The seventh check relies on a bug in older VMware versions running in emulation mode.

For a disassembled version of ScoopyNG’s fourth check, see Figure 17-2.