When you run Lab16-02.exe from the command line, it prints a usage string asking for a four-character password.

If you input an incorrect password, the program will respond “Incorrect password, Try again.”

The

strncmpfunction is called at 0x40123A.The program immediately terminates when loaded into OllyDbg using the default settings.

The program contains a

.tlssection.The TLS callback starts at 0x401060.

The

FindWindowAfunction is used to terminate the malware. It looks for a window with the class nameOLLYDBGand terminates the program if it is found. You can change the window class name using an OllyDbg plug-in like PhantOm, or NOP-out the call to exit at 0x40107C.At first, the password appears to be

bzqrwhen you set a breakpoint at thestrncmpcall.This password found in the debugger doesn’t work on the command line.

The result of

OutputDebugStringAand theBeingDebuggedflag are used as inputs to the decoding algorithm. You can use the PhantOm plug-in to ensure that theBeingDebuggedflag is 0, and you can NOP-out theaddinstruction at 0x401051.

We first run the program from the command line and see the following printed to the screen:

usage: Lab16-02.exe <4 character password>

The program is expecting a four-character password. Next, we attempt to provide the password

abcd on the command line, and get the following output:

Incorrect password, Try again.

Now, we look for a string comparison in the code so we can run the program in a debugger and

set a breakpoint at the string comparison in order to see the password. The fourth Lab 16-2 Solutions question hinted that strncmp is

used. If we load the program into IDA Pro, we see strncmp in the

main function at 0x40123A. Let’s load the program into

OllyDbg and set a breakpoint at 0x40123A.

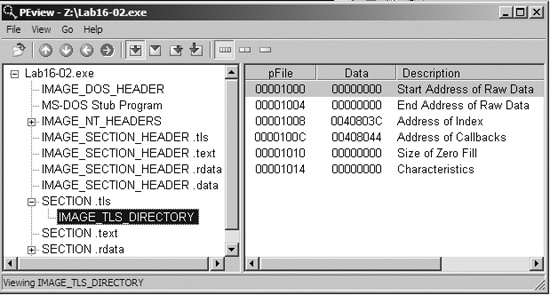

After we load Lab16-02.exe into OllyDbg, it immediately terminates without pausing the program. We suspect something is amiss, so we check the PE file structure. Figure C-62 shows the PE header section names in PEview.

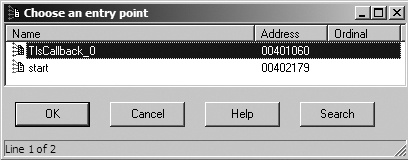

The TLS section contains callback functions that gain execution and prematurely terminate the program in OllyDbg. In IDA Pro, press CTRL-E to see the location of all entry points for the program, as shown in Figure C-63.

Double-click the TLS callback function at 0x401060 to navigate directly to the function and see if there is any anti-debugging functionality. Example C-145 shows the TLS callback code.

Example C-145. FindWindowA check for system residue of OllyDbg

00401063 cmp [ebp+arg_4], 1 00401067 jnz short loc_401081 00401069 push 0 ; lpWindowName 0040106B push offset ClassName ; "OLLYDBG" 00401070 call ds:FindWindowA ❶ 00401076 test eax, eax 00401078 jz short loc_401081 0040107A push 0 ; int 0040107C call _exit ❷

The TLS callback starts with a comparison of arg_4 to 1 to

determine whether the TLS callback is being called as a result of the process starting up. (TLS

callback functions are called at different times by the system.) In other words, this anti-debugging

technique executes only during program startup.

At ❶, the callback calls the FindWindowA function with the class name OLLYDBG. This call makes it easy for the malware to see if OllyDbg is running with its default window name. If FindWindowA finds

the window, it returns a nonzero value, which will cause the exit

function to terminate the program at ❷.

To disable this technique, NOP-out the call to exit at ❷, or use the PhantOm plug-in for OllyDbg as discussed in the previous lab. (Figure C-61 displays the options for the PhantOm plug-in.) If you’re using the PhantOm plug-in, check the Load Driver and Hide OllyDbg Windows boxes to protect against this technique.

Now load the program into OllyDbg, set a breakpoint at the strncmp call at 0x40123A, and add a command-line argument of abcd in OllyDbg before clicking the play button. When you click play, the strncmp function appears to compare abcd to bzqrp@ss; however, strncmp checks only the first 4 bytes of the bzqrp@ss

string. We conclude that the password must be bzqr, but if we try

that password on the command line outside a debugger, we receive the incorrect password error

message. We dig deeper into the code to determine if something else is going on.

We begin by properly labeling the encoded string in the listing. The second parameter passed

on the stack to strncmp is byte_408030 (a global variable), which we know to be a byte array of size 4. We change

this into a 4-byte array and rename it encoded_password.

Next, we see CreateThread called just before the call to

strncmp in the main function.

To look at the code in the thread created by this call, double-click the parameter labeled StartAddress. This function appears to be a decoding routine since it

contains many logical and shift operations on encoded_password.

Examining the decoding routine closely, we see the BeingDebugged

flag accessed, as shown in Example C-146 at ❶ and ❷.

Example C-146. Decoding routine incorporating anti-debugging in its decoding

00401124 ror encoded_password+2, 7 0040112B mov ebx, large fs:30h ❶ 00401132 xor encoded_password+3, 0C5h ... 0040117D rol encoded_password, 6 00401184 xor encoded_password, 72h 0040118B mov bl, [ebx+2] ❷ 0040118E rol encoded_password+1, 1 ... 004011A2 add encoded_password+2, bl ❸

The PEB structure is loaded into EBX at ❶, and

then the BeingDebugged flag is moved into BL at ❷. BL is then used at ❸ to modify the password. The easiest way to prevent the program from using this

technique is to ensure that the BeingDebugged flag is 0, which

can be set either manually or with the PhantOm plug-in for OllyDbg, as discussed in the previous

lab.

We load the program into OllyDbg again and break at the strncmp call at 0x40123A. This time, the password appears to be bzrr. But when we try this password on the command line, we receive the incorrect

password error message again.

Returning to the decoding routine, we see that it uses a global variable, byte_40A968, as shown in Example C-147.

Example C-147. Global byte_40A968 used in the password decoding

0040109B mov bl, byte_40A968 ❶ 004010A1 or al, 1 ... 0040110A rol encoded_password, 2 00401111 add encoded_password+1, bl ❷

At ❶, byte_40A968 is moved into BL, and BL is used in the decoding code, as seen at ❷. Double-clicking byte_40A968,

we see that it is initialized to 0, but it has a cross-reference to sub_401020. That function is shown in Example C-148.

Example C-148. OutputDebugStringA anti-debugging technique

00401024 mov [ebp+dwErrCode], 3039h 0040102B mov eax, [ebp+dwErrCode] 0040102E push eax ; dwErrCode 0040102F call ds:SetLastError ❷ 00401035 push offset OutputString ; "b" 0040103A call ds:OutputDebugStringA ❶ 00401040 call ds:GetLastError 00401046 cmp eax, [ebp+dwErrCode] ❸ 00401049 jnz short loc_40105A 0040104B mov cl, byte_40A968 00401051 add cl, 1 ❹ 00401054 mov byte_40A968, cl

At ❶, OutputDebugStringA is called, which sends a string (in this case, "b") to a debugger for display. If there is no debugger attached, an error

code is set. At ❷, SetLastError sets the error code to 0x3039, and the function checks to see if that error

is still present with the comparison at ❸. The error

code changes if the program is running outside a debugger; therefore, the comparison will set the

zero flag if the error code has not changed (running in a debugger). If this check is successful,

the code increments byte_40A968 by 1 at ❹. The easiest way to defeat this technique is to NOP-out the

add instruction at ❹.

Next, we want to track down how the function from Example C-148 (sub_401020)

is called. We check the cross-reference and see that sub_401020

is called from the TLS callback, as shown in Example C-149 (in bold).

Example C-149. The check and call from within the TLS callback

00401081 cmp [ebp+arg_4], 2

00401085 jnz short loc_40108C

00401087 call sub_401020The code in Example C-149 starts by

comparing arg_4 to the number 2. Recall from our earlier

discussion that arg_4 to the TLS callback is used to determine

when the TLS callback is made: 1 is used for when the process is starting up, 2 for when a thread is

starting up, and 3 when the process is being terminated. Therefore, this TLS callback was called

again when the CreateThread executed and caused the OutputDebugStringA to execute.

To finally get the password, we start with our OllyDbg PhantOm plug-in installed and set up to

protect us from the BeingDebugged flag check and the FindWindow check. We load the program into OllyDbg, NOP-out the add instruction at 0x401051, and set a breakpoint at the strncmp call (0x40123A). This time, the password appears to be byrr. Trying this on the command line, we get the following

message:

You entered the correct password!