Lab11-03.exe contains the strings

inet_epar32.dllandnet start cisvc, which means that it probably starts the CiSvc indexing service. Lab11-03.dll contains the stringC:\WINDOWS\System32\kernel64x.dlland imports the API callsGetAsyncKeyStateandGetForegroundWindow, which makes us suspect it is a keylogger that logs to kernel64x.dll.The malware starts by copying Lab11-03.dll to inet_epar32.dll in the Windows system directory. The malware writes data to cisvc.exe and starts the indexing service. The malware also appears to write keystrokes to C:\Windows\System32\kernel64x.dll.

The malware persistently installs Lab11-03.dll by trojanizing the indexing service by entry-point redirection. It redirects the entry point to run shellcode, which loads the DLL.

The malware infects cisvc.exe to load inet_epar32.dll and call its export

zzz69806582.Lab11-03.dll is a polling keylogger implemented in its export

zzz69806582.The malware stores keystrokes and the window into which keystrokes were entered to C:\Windows\System32\kernel64x.dll.

We’ll begin our analysis by examining the strings and imports for

Lab11-03.exe and Lab11-03.dll.

Lab11-03.exe contains the strings inet_epar32.dll and net start cisvc. The net start command is used to start a service on a Windows machine, but we

don’t yet know why the malware would be starting the indexing service on the system, so

we’ll dig down during in-depth analysis.

Lab11-03.dll contains the string C:\WINDOWS\System32\kernel64x.dll and imports the API calls GetAsyncKeyState and GetForegroundWindow, which makes

us suspect it is a keylogger that logs keystrokes to kernel64x.dll. The DLL

also contains an oddly named export: zzz69806582.

Next, we use dynamic analysis techniques to see what the malware does at runtime. We set up procmon and filter on Lab11-03.exe to see the malware create C:\Windows\System32\inet_epar32.dll. The DLL inet_epar32.dll is identical to Lab11-03.dll, which tells us that the malware copies Lab11-03.dll to the Windows system directory.

Further in the procmon output, we see the malware open a handle to

cisvc.exe, but we don’t see any WriteFile operations.

Finally, the malware starts the indexing service by issuing the command net start cisvc. Using Process Explorer, we see that

cisvc.exe is now running on the system. Since we suspect that the malware might

be logging keystrokes, we open notepad.exe and enter a bunch of

a characters. We see that kernel64x.dll is created.

Suspecting that keystrokes are logged, we open kernel64x.dll in a hex editor

and see the following output:

Untitled - Notepad: 0x41 Untitled - Notepad: 0x41 Untitled - Notepad: 0x41 Untitled - Notepad: 0x41

Our keystrokes have been logged to kernel64x.dll. We also see that the program in which we typed our keystrokes (Notepad) has been logged along with the keystroke data in hexadecimal. (The malware doesn’t turn the hexadecimal values into readable strings, so the malware author probably has a postprocessing script to more easily read what is entered.)

Next, we use in-depth techniques to determine why the malware is starting a service and how

the keylogger is gaining execution. We begin by loading Lab11-03.exe into IDA

Pro and examining the main function, as shown in Example C-59.

Example C-59. Reviewing the main method of

Lab11-03.exe

004012DB push offset NewFileName ; "C:\\WINDOWS\\System32\\

inet_epar32.dll"

004012E0 push offset ExistingFileName ; "Lab11-03.dll"

004012E5 call ds:CopyFileA ❶

004012EB push offset aCisvc_exe ; "cisvc.exe"

004012F0 push offset Format ; "C:\\WINDOWS\\System32\\%s"

004012F5 lea eax, [ebp+FileName]

004012FB push eax ; Dest

004012FC call _sprintf

00401301 add esp, 0Ch

00401304 lea ecx, [ebp+FileName]

0040130A push ecx ; lpFileName

0040130B call sub_401070 ❷

00401310 add esp, 4

00401313 push offset aNetStartCisvc ; "net start cisvc" ❸

00401318 call systemAt ❶, we see that the main method begins by copying Lab11-03.dll to

inet_epar32.dll in C:\Windows\System32. Next, it builds

the string C:\WINDOWS\System32\cisvc.exe and passes it to

sub_401070 at ❷.

Finally, the malware starts the indexing service by using system

to run the command net start cisvc at ❸.

We focus on sub_401070 to see what it might be doing with

cisvc.exe. There is a lot of confusing code in sub_401070, so take a high-level look at this function using the cross-reference diagram

shown in Figure C-40.

Using this diagram, we see that sub_401070 maps the

cisvc.exe file into memory in order to manipulate it with calls to CreateFileA, CreateFileMappingA, and

MapViewOfFile. All of these functions open the file for read and

write access. The starting address of the memory-mapped view returned by MapViewOfFile (labeled lpBaseAddress by IDA Pro) is

both read and written to. Any changes made to this file will be written to disk after the call to

UnmapViewOfFile, which explains why we didn’t see a

WriteFile function in the procmon output.

Several calculations and checks appear to be made on the PE header of cisvc.exe. Rather than analyze these complex manipulations, let’s focus on the data written to the file, and then extract the version of cisvc.exe written to disk for analysis.

A buffer is written to the memory-mapped file, as shown in Example C-60.

Example C-60. Writing 312 bytes of shellcode into cisvc.exe

0040127C mov edi, [ebp+lpBaseAddress] ❶ 0040127F add edi, [ebp+var_28] 00401282 mov ecx, 4Eh 00401287 mov esi, offset byte_409030 ❷ 0040128C rep movsd

At ❶, the mapped location of the file is moved

into EDI and adjusted by some offset using var_28. Next, ECX is

loaded with 0x4E, the number of DWORDs to write (movsd). Therefore, the total number of bytes is 0x4E * 4 = 312 bytes in

decimal. Finally, byte_409030 is moved into ESI at ❷, and rep movsd copies the

data at byte_409030 into the mapped file. We examine the data at

0x409030 and see the bytes in the left side of Table C-4.

The left side of the table contains raw bytes, but if we put the cursor at 0x409030 and press C in IDA Pro, we get the disassembly shown in the right side of the table. This is shellcode—handcrafted assembly that, in this case, is used for process injection. Rather than analyze the shellcode (doing so can be a bit complicated and messy), we’ll guess at what it does based on the strings it contains.

Toward the end of the 312 bytes of shellcode, we see two strings:

00409139 aCWindowsSystem db 'C:\WINDOWS\System32\inet_epar32.dll',0 0040915D aZzz69806582 db 'zzz69806582',0

The appearance of the path to inet_epar32.dll and the export zzz69806582 suggest that this shellcode loads the DLL and calls its

export.

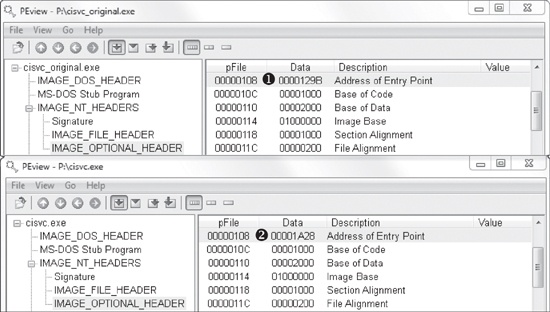

Next, we compare the cisvc.exe binary as it exists after we run the malware to a clean version that existed before the malware was run. (Most hex editors provide a comparison tool.) Comparing the versions, we see two differences: the insertion of 312 bytes of shellcode and only a 2-byte change in the PE header. We load both of these binaries into PEview to see if we notice a difference in the PE header. This comparison is shown in Figure C-41.

The top part of Figure C-41 shows the original cisvc.exe (named cisvc_original.exe) loaded into PEview, and the bottom part shows the trojanized cisvc.exe. At ❶ and ❷, we see that the entry point differs in the two binaries. If we load both binaries into IDA Pro, we see that the malware has performed entry-point redirection so that the shellcode runs before the original entry point any time that cisvc.exe is launched. Example C-61 shows a snippet of the shellcode in the trojanized version of cisvc.exe.

Example C-61. Important calls within the shellcode inside the trojanized cisvc.exe

01001B0A call dword ptr [ebp-4] ❶ 01001B0D mov [ebp-10h], eax 01001B10 lea eax, [ebx+24h] 01001B16 push eax 01001B17 mov eax, [ebp-10h] 01001B1A push eax 01001B1B call dword ptr [ebp-0Ch] ❷ 01001B1E mov [ebp-8], eax 01001B21 call dword ptr [ebp-8] ❸ 01001B24 mov esp, ebp 01001B26 pop ebp 01001B27 jmp _wmainCRTStartup ❹

Now we load the trojanized version of cisvc.exe into a debugger and

set a breakpoint at 0x1001B0A. We find that at ❶, the

malware calls LoadLibrary to load

inet_epar32.dll into memory. At ❷,

the malware calls GetProcAddress with the argument zzz69806582 to get the address of the exported function. At ❸, the malware calls zzz69806582. Finally, the malware jumps to the original entry point at ❹, so that the service can run as it would normally. The

shellcode’s function matches our earlier suspicion that it loads

inet_epar32.dll and calls its export.

Next, we analyze inet_epar32.dll, which is the same as

Lab11-03.dll. We load Lab11-03.dll into IDA Pro and begin

to analyze the file. The majority of the code stems from the zzz69806582 export. This export starts a thread and returns, so we will focus on

analyzing the thread, as shown in Example C-62.

Example C-62. Mutex and file creation performed by the thread created by zzz69806582

1000149D push offset Name ; "MZ" 100014A2 push 1 ; bInitialOwner 100014A4 push 0 ; lpMutexAttributes 100014A6 call ds:CreateMutexA ❶ ... 100014BD push 0 ; hTemplateFile 100014BF push 80h ; dwFlagsAndAttributes 100014C4 push 4 ; dwCreationDisposition 100014C6 push 0 ; lpSecurityAttributes 100014C8 push 1 ; dwShareMode 100014CA push 0C0000000h ; dwDesiredAccess 100014CF push offset FileName ; "C:\\WINDOWS\\System32\\ kernel64x.dll" 100014D4 call ds:CreateFileA ❷

At ❶, the malware creates a mutex named MZ. This mutex prevents the malware from running more than one instance of

itself, since a previous call to OpenMutex (not shown) will

terminate the thread if the mutex MZ already exists. Next, at

❷, the malware opens or creates a file named

kernel64x.dll for writing.

After getting a handle to kernel64x.dll, the malware sets the file

pointer to the end of the file and calls sub_10001380, which

contains a loop. This loop contains calls to GetAsyncKeyState,

GetForegroundWindow, and WriteFile. This is consistent with the keylogging method we discussed in User-Space Keyloggers.