After you run the malware, pop-up messages are displayed on the screen every minute.

The process being injected is explorer.exe.

You can restart the explorer.exe process.

The malware performs DLL injection to launch Lab12-01.dll within explorer.exe. Once Lab12-01.dll is injected, it displays a message box on the screen every minute with a counter that shows how many minutes have elapsed.

Let’s begin with basic static analysis. Examining the imports for

Lab12-01.exe, we see CreateRemoteThread,

WriteProcessMemory, and VirtualAllocEx. Based on the discussion in Chapter 12, we

know that we are probably dealing with some form of process injection. Therefore, our first goal

should be to determine the code that is being injected and into which process. Examining the strings

in the malware, we see some notable ones, including explorer.exe,

Lab12-01.dll, and psapi.dll.

Next, we use basic dynamic techniques to see what the malware does when it runs. When we run the malware, it creates a message box every minute (quite annoying when you are trying to use analysis tools). Procmon doesn’t have any useful information, Process Explorer shows no obvious process running, and no network functions appear to be imported, so we shift to IDA Pro to determine what is producing the message boxes.

A few lines from the start of the main function, we see the

malware resolving functions for Windows process enumeration within psapi.dll.

Example C-63 contains one example of the three

functions the malware manually resolves using LoadLibraryA and

GetProcAddress.

Example C-63. Dynamically resolving process enumeration imports

0040111F push offset ProcName ; "EnumProcessModules" 00401124 push offset LibFileName ; "psapi.dll" 00401129 call ds:LoadLibraryA0040112F push eax ; hModule 00401130 call ds:GetProcAddress00401136 mov ❶dword_408714, eax

The malware saves the function pointers to dword_408714, dword_40870C, and dword_408710. We can change these global variables to more easily identify

the function being called later in our analysis by renaming them myEnumProcessModules, myGetModuleBaseNameA, and

myEnumProcesses. In Example C-63, we should rename dword_408714 to myEnumProcessModules at ❶.

After the dynamic resolution of the functions, the code calls dword_408710 (EnumProcesses), which retrieves a PID

for each process object in the system. EnumProcesses returns an

array of the PIDs referenced by the local variable dwProcessId.

dwProcessId is used in a loop to iterate through the process list

and call sub_401000 for each PID.

When we examine sub_401000, we see that the dynamically

resolved import EnumProcessModules is called after OpenProcess for the PID passed to the function. Next, we see a call to

dword_40870C (GetModuleBaseNameA) at ❶, as shown in Example C-64.

Example C-64. Strings compared against explorer.exe

00401078 push 104h 0040107D lea ecx, [ebp+Str1] 00401083 push ecx 00401084 mov edx, [ebp+var_10C] 0040108A push edx 0040108B mov eax, [ebp+hObject] 0040108E push eax 0040108F call dword_40870C ❶ ; GetModuleBaseNameA 00401095 push 0Ch ; MaxCount 00401097 push offset Str2 ; "explorer.exe" 0040109C lea ecx, [ebp+Str1] 004010A2 push ecx ; Str1 004010A3 call _strnicmp ❷

The dynamically resolved function GetModuleBaseNameA is

used to translate from the PID to the process name. After this call, we see a comparison at

❷ between the strings obtained with GetModuleBaseNameA (Str1) and explorer.exe (Str2). The malware is

looking for the explorer.exe process in memory.

Once explorer.exe is found, the function at sub_401000 will return 1, and the main function will

call OpenProcess to open a handle to it. If the malware obtains a

handle to the process successfully, the code in Example C-65 will execute, and the handle hProcess will be used to

manipulate the process.

Example C-65. Writing a string to a remote process

0040128C push 4 ; flProtect 0040128E push 3000h ; flAllocationType 00401293 push 104h ❷ ; dwSize 00401298 push 0 ; lpAddress 0040129A mov edx, [ebp+hProcess] 004012A0 push edx ; hProcess 004012A1 call ds:VirtualAllocEx❶ 004012A7 mov [ebp+lpParameter], eax ❸ 004012AD cmp [ebp+lpParameter], 0 004012B4 jnz short loc_4012BE ... 004012BE push 0 ; lpNumberOfBytesWritten 004012C0 push 104h ; nSize 004012C5 lea eax, [ebp+Buffer] 004012CB push eax ; lpBuffer 004012CC mov ecx, [ebp+lpParameter] 004012D2 push ecx ; lpBaseAddress 004012D3 mov edx, [ebp+hProcess] 004012D9 push edx ; hProcess 004012DA call ds:WriteProcessMemory❹

In Example C-65, we see a call to VirtualAllocEx at ❶. This

dynamically allocates memory in the explorer.exe process: 0x104 bytes are

allocated by pushing dwSize at ❷. If VirtualAllocEx is successful, a pointer to the

allocated memory will be moved into lpParameter at ❸, to be passed with the process handle to WriteProcessMemory at ❹, in

order to write data to explorer.exe. The data written to the process is

referenced by the Buffer parameter in bold.

In order to understand what is injected, we trace the code back to where Buffer is set. We find it set to the path of the current directory

appended with Lab12-01.dll. We can now conclude that this malware

writes the path of Lab12-01.dll into the explorer.exe

process.

If the malware successfully writes the path of the DLL into explorer.exe, the code in Example C-66 will execute.

Example C-66. Creating the remote thread

004012E0 push offset ModuleName ; "kernel32.dll" 004012E5 call ds:GetModuleHandleA004012EB mov [ebp+hModule], eax 004012F1 push offset aLoadlibrarya ; "LoadLibraryA" 004012F6 mov eax, [ebp+hModule] 004012FC push eax ; hModule 004012FD call ds:GetProcAddress00401303 mov [ebp+lpStartAddress], eax ❶ 00401309 push 0 ; lpThreadId 0040130B push 0 ; dwCreationFlags 0040130D mov ecx, [ebp+lpParameter] 00401313 push ecx ; lpParameter 00401314 mov edx, [ebp+lpStartAddress] 0040131A push edx ❷ ; lpStartAddress 0040131B push 0 ; dwStackSize 0040131D push 0 ; lpThreadAttributes 0040131F mov eax, [ebp+hProcess] 00401325 push eax ; hProcess 00401326 call ds:CreateRemoteThread

In Example C-66, the calls to GetModuleHandleA and GetProcAddress (in bold) will be

used to get the address to LoadLibraryA. The address of LoadLibraryA will be the same in explorer.exe as it

is in the malware (Lab12-01.exe) with the address of LoadLibraryA inserted into lpStartAddress shown at

❶. lpStartAddress is

provided to CreateRemoteThread at ❷ in order to force explorer.exe to call

LoadLibraryA. The parameter for LoadLibraryA is passed via CreateRemoteThread in lpParameter, the

string containing the path to Lab12-01.dll. This, in turn, starts a thread in

the remote process that calls LoadLibraryA with the parameter of

Lab12-01.dll. We can now conclude that this malware executable

performs DLL injection of Lab12-01.dll into

explorer.exe.

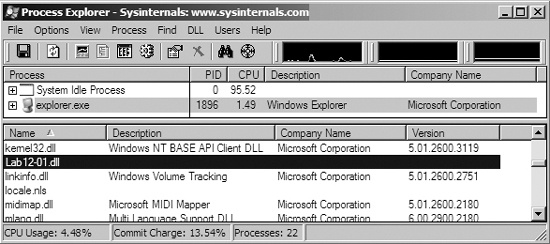

Now that we know where and what is being injected, we can try to stop those annoying pop-ups,

launching Process Explorer to help us out. As shown in Figure C-42, we select explorer.exe in

the process listing, and then choose View ▸ Show Lower Pane

and View ▸ Lower Pane View ▸ DLLs. Scrolling through

the resulting window, we see Lab12-01.dll listed as being loaded into

explorer.exe’s memory space. Using Process Explorer is an easy way to

spot DLL injection and useful in confirming our IDA Pro analysis. To stop the pop-ups, we can use

Process Explorer to kill explorer.exe, and then restart it by selecting

File ▸ Run and entering explorer.

Having analyzed Lab12-01.exe, we move on to Lab12-01.dll to see if it does something in addition to creating message boxes. When we analyze Lab12-01.dll with IDA Pro, we see that it does little more than create a thread that then creates another thread. The code in Example C-67 is from the first thread, a loop that creates a thread every minute (0xEA60 milliseconds).

Example C-67. Analyzing the thread created by Lab12-01.dll

10001046 mov ecx, [ebp+var_18] 10001049 push ecx 1000104A push offset Format ; "Practical Malware Analysis %d" 1000104F lea edx, [ebp+Parameter] 10001052 push edx ; Dest 10001053 call _sprintf ❷ 10001058 add esp, 0Ch 1000105B push 0 ; lpThreadId 1000105D push 0 ; dwCreationFlags 1000105F lea eax, [ebp+Parameter] 10001062 push eax ; lpParameter 10001063 push offsetStartAddress❶ ; lpStartAddress 10001068 push 0 ; dwStackSize 1000106A push 0 ; lpThreadAttributes 1000106C call ds:CreateThread10001072 push 0EA60h ; dwMilliseconds 10001077 call ds:Sleep1000107D mov ecx, [ebp+var_18] 10001080 add ecx, 1 ❸ 10001083 mov [ebp+var_18], ecx

The new thread at ❶, labeled StartAddress by IDA Pro, creates the message box that says “Press OK

to reboot,” and takes a parameter for the title of the box that is set by the sprintf at ❷. This parameter

is the format string "Practical Malware Analysis %d", where

%d is replaced with a counter stored in var_18 that increments at ❸. We conclude that

this DLL does nothing other than produce annoying message boxes that increment by one every

minute.