When you run the program without any parameters, it exits immediately.

The

mainfunction is located at 0x00000001400010C0. You can spot the call tomainby looking for a function call that accepts an integer and two pointers as parameters.The string

ocl.exeis stored on the stack.To have this program run its payload without changing the filename of the executable, you can patch the

jumpinstruction at 0x0000000140001213 so that it is a NOP instead.The name of the executable is being compared against the string

jzm.exeby the call tostrncmpat 0x0000000140001205.The function at 0x00000001400013C8 takes one parameter, which contains the socket created to the remote host.

The call to

CreateProcesstakes 10 parameters. We can’t tell from the IDA Pro listing because we can’t distinguish between things being stored on the stack and things being used in a function call, but the function is documented in MSDN as always taking 10 parameters.

When we try to run this program to perform dynamic analysis, it immediately exits, so we

open the program and try to find the main method. (You

won’t need to do this if you have the latest version of IDA Pro; if you have an older version,

you may need to find the main method.)

We begin our analysis at 0x0000000140001750, the entry point as specified in the PE header, as shown in Example C-223.

Example C-223. Entry point of Lab21-01.exe

0000000140001750 sub rsp, 28h 0000000140001754 call sub_140002FE4 ❶ 0000000140001759 add rsp, 28h 000000014000175D jmp sub_1400015D8 ❷

We know that the main method takes three parameters:

argc, argv, and envp. Furthermore, we know that argc

will be a 32-bit value, and that argv and envp will be 64-bit values. Because the function call at ❶ does not take any parameters, we know that it can’t be the

main method. We quickly check the function and see that it calls

only functions imported from other DLLs, so we know that the call to main must be after the jmp instruction at ❷.

We follow the jump and scroll down looking for a function that takes three parameters. We pass

many function calls without parameters and eventually find the call to the main method, as shown in Example C-224. This

call takes three parameters. The first at ❶ is a 32-bit

value representing an int, and the next two parameters at

❷ and ❸ are

64-bit values representing pointers.

Example C-224. Call to the main method of

Lab21-01.exe

00000001400016F3 mov r8, cs:qword_14000B468 ❸ 00000001400016FA mov cs:qword_14000B470, r8 0000000140001701 mov rdx, cs:qword_14000B458 ❷ 0000000140001708 mov ecx, cs:dword_14000B454 ❶ 000000014000170E call sub_1400010C0

We can now move on to the main function. Early in the

main function, we see a lot of data moved onto the stack,

including the data shown in Example C-225.

Example C-225. ASCII string being loaded on the stack that has not been recognized by IDA Pro

0000000140001150 mov byte ptr [rbp+250h+var_160+0Ch], 0 0000000140001157 mov [rbp+250h+var_170], 2E6C636Fh 0000000140001161 mov [rbp+250h+var_16C], 657865h

You should immediately notice that that numbers being moved onto the stack represent ASCII

characters. The value 0x2e is a period (.), and the hexadecimal

values starting with 3, 4, 5, and 6 are mostly letters. Right-click the numbers to have IDA Pro show which characters are represented, and press R on each line

to change the display. After changing the display so that the ASCII characters are labeled properly

by IDA Pro, the code should look like Example C-226.

Example C-226. Listing 21-3L with the ASCII characters labeled properly by IDA Pro

0000000140001150 mov byte ptr [rbp+250h+var_160+0Ch], 0 0000000140001157 mov [rbp+250h+var_170], '.lco' 0000000140001161 mov [rbp+250h+var_16C], 'exe'

This view tells us that the code is storing the string ocl.exe on the stack. (Remember that x86 and x64 assembly are little-endian, so when

ASCII data is represented as if it were a 32-bit number, the characters are reversed.) These three

mov instructions together store the bytes representing

ocl.exe on the stack.

Recall that Lab09-02.exe won’t run properly unless the executable name is ocl.exe. At this point, we try renaming the file ocl.exe and running it, but that doesn’t work, so we need to continue analyzing the code in IDA Pro.

As we continue our analysis, we see that the code calls strrchr, as in Lab 9-2 Solutions, to obtain the executable’s

filename without the leading directory path. Then we see an encoding function, partially shown in

Example C-227.

Example C-227. An encoding function

00000001400011B8 mov eax, 4EC4EC4Fh 00000001400011BD sub cl, 61h 00000001400011C0 movsx ecx, cl 00000001400011C3 imul ecx, ecx 00000001400011C6 sub ecx, 5 00000001400011C9 imul ecx 00000001400011CB sar edx, 3 00000001400011CE mov eax, edx 00000001400011D0 shr eax, 1Fh 00000001400011D3 add edx, eax 00000001400011D5 imul edx, 1Ah 00000001400011D8 sub ecx, edx

This encoding function would be very tedious to analyze, so we note it and move on to see what

is done with the encoded string. We scroll down a little further to a call to strncmp, as shown in Example C-228.

Example C-228. Code that compares the filename against the encoded string and takes one of two different code paths

00000001400011F4 lea rdx, [r11+1] ; char * 00000001400011F8 lea rcx, [rbp+250h+var_170] ; char * 00000001400011FF mov r8d, 104h ; size_t 0000000140001205 call strncmp 000000014000120A test eax, eax 000000014000120C jz short loc_140001218 ❶ 000000014000120E 000000014000120E loc_14000120E: ; CODE XREF: main+16Aj 000000014000120E mov eax, 1 0000000140001213 jmp loc_1400013D7 ❷

Scrolling up to see which two strings are being compared, we discover that the first

string is the name of the malware being executed and the second is the encoded string. Based on the

return value of strncmp, we either take the jump at ❶, which continues to more interesting code, or we take the jump

at ❷, which prematurely exits the program.

In order to analyze the program dynamically, we need to get it to continue running without

exiting prematurely. We could patch the jmp instruction at

❷ in order to force the code to continue executing even

if the program name is incorrect. Unfortunately, OllyDbg does not work with 64-bit executables, so

we would need to use a hex editor to edit the bytes manually. Instead of patching the code, we can

try to determine the correct string and rename our process, as we did in Lab 9-2 Solutions.

To determine the string that the malware is searching, we can use dynamic analysis to obtain

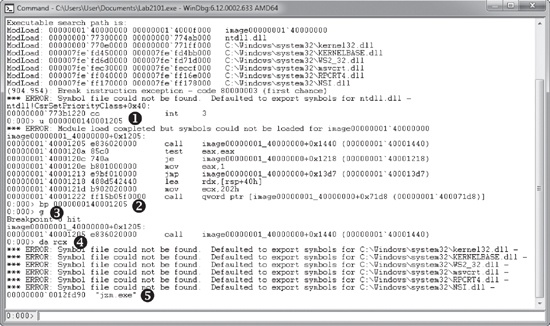

the encoded value that the executable should be named. To do so, we use WinDbg (again, because

OllyDbg does not support 64-bit executables). We open the program in WinDbg and set a breakpoint on

the call to strncmp, as shown in Figure C-69.

WinDbg output can sometimes be a bit verbose, so we’ll focus on the commands issued. We

can’t set a breakpoint using bp strncmp because WinDbg

doesn’t know the location of strncmp. However, IDA Pro uses

signatures to find strncmp, and from Example C-228, we know that the call to strncmp is at 0000000140001205. As shown in Figure C-69, at ❶, we use the u instruction to verify the

instructions at 0000000140001205, and then set a breakpoint on that location at ❷ and issue the g (go) command at ❸. When the

breakpoint is hit, we enter da

rcx to obtain the string at ❹. At

❺, we see that the string being compared is jzm.exe.

Now that we know how to get the program to run, we can continue analyzing it. We see the

following import calls in order: WSAStartup, WSASocket, gethostbyname, htons, and connect. Without spending

much effort analyzing the actual code, we can tell from the function calls that the program is

connecting to a remote socket. Then we see another function call that we must analyze, as shown in

Example C-229.

Example C-229. A 64-bit function call with an unclear number of parameters

00000001400013BD mov rcx, rbx ❶

00000001400013C0 movdqa oword ptr [rbp+250h+var_160], xmm0

00000001400013C8 call sub_140001000At ❶, the RBX register is moved into RCX. We

can’t be sure if this is just normal register movement or if this is a function parameter.

Looking back to see what is stored in RBX, we discover that it stores the socket that was returned

by WSASocket. Once we start to analyze the function at

0x0000000140001000, we see that value used as a parameter to CreateProcessA. The call to CreateProcessA is shown in

Example C-230.

Example C-230. A 64-bit call to CreateProcessA

0000000140001025 mov [rsp+0E8h+hHandle], rax 000000014000102A mov [rsp+0E8h+var_90], rax 000000014000102F mov [rsp+0E8h+var_88], rax 0000000140001034 lea rax, [rsp+0E8h+hHandle] 0000000140001039 xor r9d, r9d ; lpThreadAttributes 000000014000103C xor r8d, r8d ; lpProcessAttributes 000000014000103F mov [rsp+0E8h+var_A0], rax 0000000140001044 lea rax, [rsp+0E8h+var_78] 0000000140001049 xor ecx, ecx ; lpApplicationName 000000014000104B mov [rsp+0E8h+var_A8], rax ❶ 0000000140001050 xor eax, eax 0000000140001052 mov [rsp+0E8h+var_78], 68h 000000014000105A mov [rsp+0E8h+var_B0], rax 000000014000105F mov [rsp+0E8h+var_B8], rax 0000000140001064 mov [rsp+0E8h+var_C0], eax 0000000140001068 mov [rsp+0E8h+var_C8], 1 0000000140001070 mov [rsp+0E8h+var_3C], 100h 000000014000107B mov [rsp+0E8h+var_28], rbx ❷ 0000000140001083 mov [rsp+0E8h+var_18], rbx ❸ 000000014000108B mov [rsp+0E8h+var_20], rbx ❹ 0000000140001093 call cs:CreateProcessA

The socket is stored at RBX in code not shown in the listing. All the parameters are moved onto the stack instead of pushed onto the stack, which makes the function call considerably more complicated than the 32-bit version.

Most of the moves onto the stack represent parameters to CreateProcessA, but some do not. For example, the move at ❶ is LPSTARTUPINFO being passed

as a parameter to CreateProcessA. However, the STARTUPINFO structure itself is stored on the stack, starting at var_78. The mov instructions seen at

❷, ❸, and

❹ are values being moved into the STARTUPINFO structure, which happens to be stored on the stack, and not

individual parameters for CreateProcessA.

Because of all the intermingling of function parameters and other stack activity, it’s

difficult to tell how many parameters are passed to a function just by looking at the function call.

However, because CreateProcessA is documented, we know that it

takes exactly 10 parameters.

At this point, we’ve reached the end of the code. We’ve learned that the malware checks to see if the program is jzm.exe, and if so, it creates a reverse shell to a remote computer to enable remote access on the machine.