The malware immediately terminates inside a VM, unlike Lab 12-2 Solutions, which performs process replacement on svchost.exe.

If you force the jumps at 0x4019A1, 0x4019C0, and 0x401467 to be taken, and the jump at 0x401A2F to not be taken, the malware performs process replacement using a keylogger from its resource section.

The malware uses four different anti-VM techniques:

It uses the backdoor I/O communication port.

It searches the registry key

SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\DeviceClassesfor the stringvmware.It checks the MAC address to see if it is the default used by VMware.

It searches the process list with a string-hashing function for processes starting with the string

vmware.

To avoid the anti-VM techniques used by this malware, you can remove VMware tools and modify the MAC address.

In OllyDbg, you can apply the following patches:

NOP-out the instruction at 0x40145D.

Change the instructions at 0x40199F and 0x4019BE to

xor eax, eax.Modify the instruction at 0x40169F to

jmp 0x40184A.

As noted in the lab description, this malware is the same as Lab12-02.exe except that it includes anti-VM techniques. Therefore, a good place to start is with a review of Lab 12-2 Solutions.

We begin by loading the binary into IDA Pro and searching for vulnerable x86 instructions

using findAntiVM.py (as in Lab 17-1 Solutions). This script

identifies one anti-VM instruction at 0x401AC8 and highlights it in red. We notice that this is the

backdoor I/O communication port being queried via the in

instruction. This anti-VM technique is contained in the function named sub_401A80 by IDA Pro. This function returns 1 if it is executing inside a VM; otherwise,

it returns 0. There is only one cross-reference from the beginning of the main function, as shown at ❶ in Example C-165.

Example C-165. The check after the call to query the I/O communication port

0040199A call sub_401A80 ❶ ; Query I/O communication port 0040199F test eax, eax ❸ 004019A1 jz short loc_4019AA ❷ 004019A3 xor eax, eax 004019A5 jmp loc_401A71

The jz instruction at ❷ must be taken, or the main

method will terminate immediately by jumping to 0x401A71. We disable this anti-VM technique by

setting the zero flag to 1 when execution arrives at the jz

instruction. To permanently disable this technique, change the test instruction at ❸ into xor eax, eax as follows:

Start OllyDbg and place your cursor on line 0x40199F.

Press the spacebar and enter

xor eax, eaxin the text box.Click Assemble.

Next, we use Strings to compare the output from Lab 12-2 Solutions to the output from Lab17-03.exe. The following are the new strings found in this lab:

vmware SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\DeviceClasses Iphlpapi.dll GetAdaptersInfo

These strings provide us with interesting leads. For example, the string SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\DeviceClasses appears to be a registry

path, and GetAdaptersInfo is a function used for getting

information about the network adapter. Digging deeper into the first string in the listing, vmware, with IDA Pro, we find only one cross-reference to this string from

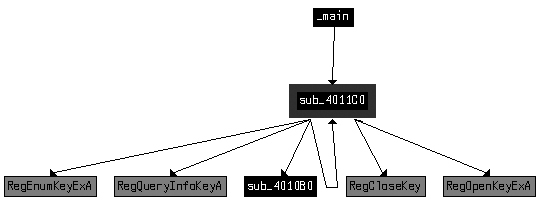

the subroutine sub_4011C0.

Figure C-66 shows the cross-reference graph for

sub_4011C0. The arrows leaving sub_4011C0 show that it calls several registry functions. The function also calls itself,

as shown by the arrow that loops back (making it a recursive function). Based on the graph, we

suspect that the function is recursively checking the registry for the string vmware. Finally, Figure C-66 shows that sub_4011C0 is called from main.

Example C-166 shows where sub_4011C0 is called at ❶

inside the main function. Three parameters are pushed onto the

stack before the call, including the registry key, which we saw in the strings listing.

Example C-166. The parameters for sub_4011C0 and the check after

004019AA push 2 ; int 004019AC push offset SubKey ; "SYSTEM\\CurrentControlSet\\Control\\Device"... 004019B1 push 80000002h ; hKey 004019B6 call sub_4011C0 ❶ 004019BB add esp, 0Ch 004019BE test eax, eax ❸ 004019C0 jz short loc_4019C9 ❷

Since SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\DeviceClasses

is passed to a recursive registry function, we can assume this function is recursively checking the

registry from that path on. This is a system residue check, as described in Chapter 17. If you examine sub_4011C0 further, you will see it loop through the registry subkeys under DeviceClasses. It compares the first six characters (after changing them

to lowercase) of each subkey name to the string vmware.

Since our goal is to have the malware run in our safe environment, we just need to ensure that

the jz instruction at ❷ is taken; otherwise, the program will terminate immediately. We disable this anti-VM

technique by making sure the zero flag is 1 when we arrive at the jz instruction. We can permanently disable this check by changing the test instruction at ❸ into

xor eax, eax using OllyDbg, as described in Searching for Vulnerable Instructions.

Next, we use IDA Pro to check the cross-references for the string GetAdaptersInfo. In Example C-167, we see the

string referenced at ❶.

Example C-167. The dynamic resolution of GetAdaptersInfo

004019C9 push offset aGetadaptersinf ; "GetAdaptersInfo" ❶ 004019CE push offset LibFileName ; "Iphlpapi.dll" 004019D3 call ds:LoadLibraryA 004019D9 push eax ; hModule 004019DA call ds:GetProcAddress 004019E0 mov GetAdaptersInfo_Address ❷, eax

The malware dynamically resolves GetAdaptersInfo using

LoadLibraryA and GetProcAddress, and loads the resulting address into a global variable, which we have

renamed GetAdaptersInfo_Address at ❷ to make it easier to recognize function calls to the

runtime-loaded address of GetAdaptersInfo.

Checking the cross-references to GetAdaptersInfo_Address,

we see it called in two places within the function sub_401670. At

a high level, this function appears similar to a function we examined in Lab 12-2 Solutions that loaded the resource section containing the keylogger. However,

the function in this lab appears to have a bunch of code added to the start. Let’s examine

that code.

Example C-168 shows the start of a series of byte

moves at ❶. This byte array initialization can be

converted to a byte array by double-clicking var_38 and setting

it to an array of size 27. We rename the array to Byte_Array to

aid our analysis later on.

Example C-168. Byte array initialization and first call to GetAdaptersInfo_Address

004016A8 mov [ebp+var_38], 0 ❶ 004016AC mov [ebp+var_37], 50h 004016B0 mov [ebp+var_36], 56h 004016B4 mov [ebp+var_35], 0 004016B8 mov [ebp+var_34], 0Ch 004016BC mov [ebp+var_33], 29h ... 0040170C mov [ebp+var_1F], 0 00401710 mov [ebp+var_1E], 27h 00401714 mov [ebp+dwBytes], 0 0040171B lea eax, [ebp+dwBytes] 0040171E push eax 0040171F push 0 00401721 call GetAdaptersInfo_Address ❷

The call to GetAdaptersInfo_Address at ❷ in Example C-168

takes two parameters: a linked list of IP_ADAPTER_INFO structures

and the size of that linked list. Here, the linked list passed in is NULL, and the size will be

returned in dwBytes. Calling GetAdaptersInfo_Address with the first parameter set to NULL is an easy way to figure out

how much data it returns in order to allocate memory for the linked list structure to be used in a

second call to GetAdaptersInfo_Address. This is the reason the

malware uses dwBytes in subsequent calls to GetProcessHeap and HeapAlloc.

Example C-169 shows that the malware uses

HeapAlloc at ❶ and

calls GetAdaptersInfo_Address a second time at ❷.

Example C-169. Second call to GetAdaptersInfo_Address, which populates

the results

0040174B call ds:HeapAlloc ❶ 00401751 mov [ebp+lpMem], eax ❸ 00401754 cmp [ebp+lpMem], 0 ... 00401766 lea edx, [ebp+dwBytes] 00401769 push edx 0040176A mov eax, [ebp+lpMem] 0040176D push eax 0040176E call GetAdaptersInfo_Address ❷

The parameter labeled lpMem by IDA Pro is the return value

from HeapAlloc, as seen at ❸. This parameter is passed to the second call of GetAdaptersInfo_Address at ❷ instead of NULL.

After the call to GetAdaptersInfo_Address, the lpMem parameter is a pointer to a linked list of IP_ADAPTER_INFO structures with a size of dwBytes.

We must add the IP_ADAPTER_INFO structure to IDA Pro since

it failed to recognize and label things fully. To do so, press the INSERT key within the Structures window and add the standard structure IP_ADAPTER_INFO. Now apply the structure to data in our disassembly as

shown in Table C-9 at ❶, ❷, and ❸.

Table C-9. Before and After Applying Structure Information and Standard Constants

The left side of Table C-9 shows the code

listing before we apply the IP_ADAPTER_INFO structure offsets and

standard constants to the data. To apply the structure, right-click the locations ❶, ❷, and ❸, and you will be given the option to turn numbers into the

descriptive strings shown in bold in the right side of the table. Using the MSDN page for IP_ADAPTER_INFO as reference, we learn about the standard constants for

Type and see that 0x6 and 0x71 correspond to an adapter type of

Ethernet or 802.11 wireless (so the address will be a MAC address).

In the three comparisons shown in Table C-9, the malware is checking for Ethernet or wireless interfaces, and then confirming that the adapter address length is greater than 2. If this check fails, the malware loops to the next adapter in the linked list. If the check succeeds, the code shown in Example C-170 will execute.

Example C-170. Comparing the adapter address to Byte_Array

004017CC jmp short loc_4017D7 004017CE mov edx, [ebp+var_3C] 004017D1 add edx, 3 ❸ 004017D4 mov [ebp+var_3C], edx ... 004017DD mov ecx, 3 ❹ 004017E2 mov eax, [ebp+var_3C] 004017E5 lea edi, [ebp+eax+Byte_Array] ❷ 004017E9 mov esi, [ebp+lpMem] 004017EC add esi, 194h ❶ 004017F2 xor edx, edx 004017F4 repe cmpsb 004017F6 jnz short loc_401814

To make this code more readable, right-click the 194h at

❶ and change it to IP_ADAPTER_INFO.Address.

The code is comparing the currently referenced IP_ADAPTER_INFO’s address to an index in Byte_Array. Byte_Array is indexed at ❷ using EAX, which is filled with var_3C, a loop counter that we see incremented by 3 at ❸. The repe cmpsb instruction compares Byte_Array to the IP_ADAPTER_INFO.Address for 3 bytes (because ECX is set to 3 at ❹), which means it is checking to see if the first 3 bytes of the

MAC address are {00h,50h,56h} or {00h,0Ch,29h} and so on. An Internet search for “00,0C,29” tells us that it is a common start of the

default MAC address for VMware. Since the array is of size 27, we know that this code compares nine

different MAC addresses (most associated with VMware).

We permanently disable this check by avoiding the MAC address comparisons altogether. Modify

the jnz instruction at 0x40169F to be jmp 0x40184A using OllyDbg’s Assemble functionality, as we did earlier to force the

malware to skip the adapter checks and go straight to the resource section manipulation code.

The final anti-VM check in this malware is in sub_401400,

which performs process replacement. The code in Example C-171 shows a call

at ❶, which determines if the jz at ❷ will be taken. If the jump is not

taken, the code will terminate without performing the process replacement.

Example C-171. Final anti-VM check

00401448 xor eax, eax ❸ ... 00401456 push 6 00401458 push 0F30D12A5h 0040145D call sub_401130 ❶ 00401462 add esp, 8 00401465 test eax, eax 00401467 jz short loc_401470 ❷

As shown in Example C-171, the anti-VM function sub_401130 takes two parameters: 6 and

the integer 0xF30D12A5. This function loops through the process

listing by calling CreateToolhelp32Snapshot, Process32First, and Process32Next.

Process32Next is inside a loop with the code shown in Example C-172.

Example C-172. Code for comparing a process name string

0040116D mov edx, [ebp+arg_4] 00401170 push edx 00401171 lea eax, [ebp+pe.szExeFile] 00401177 push eax 00401178 call sub_401060 ❶ ; make lowercase 0040117D add esp, 4 00401180 push eax 00401181 call sub_401000 ❷ ; get string hash 00401186 add esp, 8 00401189 mov [ebp+var_130], eax 0040118F mov ecx, [ebp+var_130] 00401195 cmp ecx, [ebp+arg_0] ❸

The function sub_401060 called at ❶ takes a single parameter containing the name of the process and

sets all of the parameter’s characters to lowercase. The function sub_401000 called at ❷ takes two parameters:

6 (arg_4) and the lowercase

string returned from sub_401060. The result of this function is

compared to the 0xF30D12A5 (arg_0) at ❸. If the result is equal to 0xF30D12A5, the function will return

1, which will cause the malware to terminate. In other words, sub_401000 is taking the process name and turning it into a number, and then seeing if

that number is equal to a preset value. sub_401000 is a simple

string-hashing function. Given the parameter "vmware", it returns

0xF30D12A5. The malware is cleverly using a string hash to avoid using the string vmware in the comparison, which would have made easy pickings for the

malware analyst.

To permanently disable this final anti-VM check, we can NOP-out the call to sub_401130 at 0x40145D. This forces the malware to skip the check and go

straight to the process-replacement code because the xor at

❸ in Example C-171 ensures that

the EAX register will be 0.

This malware performs four different checks for VMware. Three of these check for system residue, and the other queries the I/O communication port. The system residue checking techniques include the following:

Check the first 3 bytes of the MAC address for known values associated with virtual machines.

Check the registry for the key

vmwareunder the registry pathSYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\DeviceClasses.Check the process listing for processes beginning with the string

vmwarein any combination of uppercase and lowercase letters.