The Windows registry is used to store OS and program configuration information, such as settings and options. Like the file system, it is a good source of host-based indicators and can reveal useful information about the malware’s functionality.

Early versions of Windows used .ini files to store configuration information. The registry was created as a hierarchical database of information to improve performance, and its importance has grown as more applications use it to store information. Nearly all Windows configuration information is stored in the registry, including networking, driver, startup, user account, and other information.

Malware often uses the registry for persistence or configuration data. The malware adds entries into the registry that will allow it to run automatically when the computer boots. The registry is so large that there are many ways for malware to use it for persistence.

Before digging into the registry, there are a few important registry terms that you’ll need to know in order to understand the Microsoft documentation:

Root key. The registry is divided into five top-level sections called root keys. Sometimes, the terms HKEY and hive are also used. Each of the root keys has a particular purpose, as explained next.

Subkey. A subkey is like a subfolder within a folder.

Key. A key is a folder in the registry that can contain additional folders or values. The root keys and subkeys are both keys.

Value entry. A value entry is an ordered pair with a name and value.

Value or data. The value or data is the data stored in a registry entry.

The registry is split into the following five root keys:

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE(HKLM). Stores settings that are global to the local machineHKEY_CURRENT_USER(HKCU). Stores settings specific to the current userHKEY_CLASSES_ROOT. Stores information defining typesHKEY_CURRENT_CONFIG. Stores settings about the current hardware configuration, specifically differences between the current and the standard configurationHKEY_USERS. Defines settings for the default user, new users, and current users

The two most commonly used root keys are HKLM and HKCU. (These keys are commonly referred to by their abbreviations.)

Some keys are actually virtual keys that provide a way to reference the underlying registry

information. For example, the key HKEY_CURRENT_USER is actually

stored in HKEY_USERS\SID, where SID is the

security identifier of the user currently logged in. For example, one popular subkey, HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run, contains

a series of values that are executables that are started automatically when a user logs in. The root

key is HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, which stores the subkeys of SOFTWARE, Microsoft, Windows, CurrentVersion, and Run.

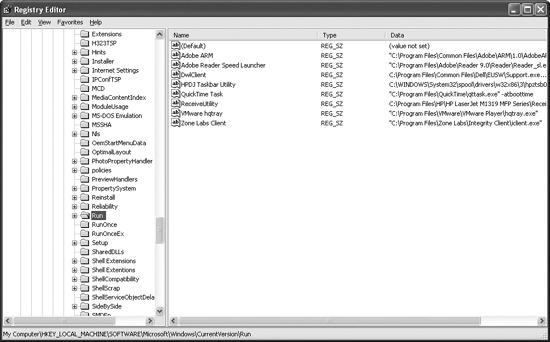

The Registry Editor (Regedit), shown in Figure 7-1, is a built-in Windows tool used to view and edit the registry. The window on the left shows the open subkeys. The window on the right shows the value entries in the subkey. Each value entry has a name, type, and value. The full path for the subkey currently being viewed is shown at the bottom of the window.

Writing entries to the Run subkey (highlighted in Figure 7-1) is a well-known way to set up software to run automatically. While not a

very stealthy technique, it is often used by malware to launch itself automatically.

The Autoruns tool (free from Microsoft) lists code that will run automatically when the OS starts. It lists executables that run, DLLs loaded into Internet Explorer and other programs, and drivers loaded into the kernel. Autoruns checks about 25 to 30 locations in the registry for code designed to run automatically, but it won’t necessarily list all of them.

Malware often uses registry functions that are part of the Windows API in order to modify the registry to run automatically when the system boots. The following are the most common registry functions:

RegOpenKeyEx. Opens a registry for editing and querying. There are functions that allow you to query and edit a registry key without opening it first, but most programs useRegOpenKeyExanyway.RegSetValueEx. Adds a new value to the registry and sets its data.RegGetValue. Returns the data for a value entry in the registry.

When you see these functions in malware, you should identify the registry key they are accessing.

In addition to registry keys for running on startup, many registry values are important to the system’s security and settings. There are too many to list here (or anywhere), and you may need to resort to a Google search for registry keys as you see them accessed by malware.

Example 7-1 shows real malware code opening the

Run key from the registry and adding a value so that the program

runs each time Windows starts. The RegSetValueEx function, which

takes six parameters, edits a registry value entry or creates a new one if it does not exist.

Note

When looking for function documentation for RegOpenKeyEx, RegSetValuEx, and so on, remember to

drop the trailing W or A

character.

Example 7-1. Code that modifies registry settings

0040286F push 2 ; samDesired 00402871 push eax ; ulOptions 00402872 push offset SubKey ; "Software\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Run" 00402877 push HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE ; hKey 0040287C ❶call esi ; RegOpenKeyExW 0040287E test eax, eax 00402880 jnz short loc_4028C5 00402882 00402882 loc_402882: 00402882 lea ecx, [esp+424h+Data] 00402886 push ecx ; lpString 00402887 mov bl, 1 00402889 ❷call ds:lstrlenW0040288F lea edx, [eax+eax+2] 00402893 ❸push edx ; cbData 00402894 mov edx, [esp+428h+hKey] 00402898 ❹lea eax, [esp+428h+Data] 0040289C push eax ; lpData 0040289D push 1 ; dwType 0040289F push 0 ; Reserved 004028A1 ❺lea ecx, [esp+434h+ValueName] 004028A8 push ecx ; lpValueName 004028A9 push edx ; hKey 004028AA call ds:RegSetValueExW

Example 7-1 contains comments at the end of

most lines after the semicolon. In most cases, the comment is the name of the parameter being pushed

on the stack, which comes from the Microsoft documentation for the function being called. For

example, the first four lines have the comments samDesired,

ulOptions, "Software\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Run", and hKey. These comments give information about the meanings of the values being pushed. The

samDesired value indicates the type of security access requested,

the ulOptions field is an unsigned long integer representing the

options for the call (remember about Hungarian notation), and the hKey is the handle to the root key being accessed.

The code calls the RegOpenKeyEx function at ❶ with the parameters needed to open a handle to the registry key

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run. The value

name at ❺ and data at ❹ are stored on the stack as parameters to this function, and are shown here as having

been labeled by IDA Pro. The call to lstrlenW at ❷ is needed in order to get the size of the data, which is given

as a parameter to the RegSetValueEx function at ❸.

Files with a .reg extension contain human-readable registry data. When a user double-clicks a .reg file, it automatically modifies the registry by merging the information the file contains into the registry—almost like a script for modifying the registry. As you might imagine, malware sometimes uses .reg files to modify the registry, although it more often directly edits the registry programmatically.

Example 7-2 shows an example of a .reg file.

Example 7-2. Sample .reg file

Windows Registry Editor Version 5.00 [HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run] "MaliciousValue"="C:\Windows\evil.exe"

The first line in Example 7-2 simply lists the version of the

registry editor. In this case, version 5.00 corresponds to Windows XP. The key to be modified,

[HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run], appears

within brackets. The last line of the .reg file contains the value name and the

data for that key. This listing adds the value name MaliciousValue, which will automatically run C:\Windows\evil.exe each time the OS boots.