The problem at hand is that a proposed trail has been drawn in order to provide services for the public. This example could apply to road construction or even finding sites for commercial properties for the purpose of provisioning services.

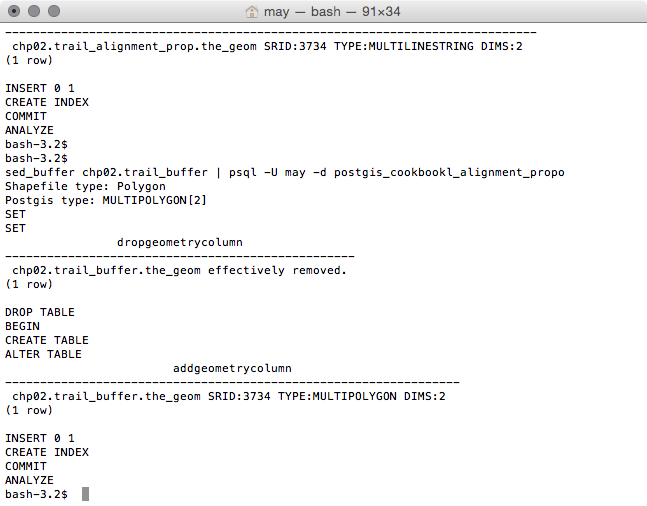

First, unzip the trail_census.zip file, then perform a quick data load using the following commands from the unzipped folder:

shp2pgsql -s 3734 -d -i -I -W LATIN1 -g the_geom census chp02.trail_census | psql -U me -d postgis_cookbook shp2pgsql -s 3734 -d -i -I -W LATIN1 -g the_geom trail_alignment_proposed_buffer chp02.trail_buffer | psql -U me -d postgis_cookbook shp2pgsql -s 3734 -d -i -I -W LATIN1 -g the_geom trail_alignment_proposed chp02.trail_alignment_prop | psql -U me -d postgis_cookbook

The preceding commands will produce the following outputs:

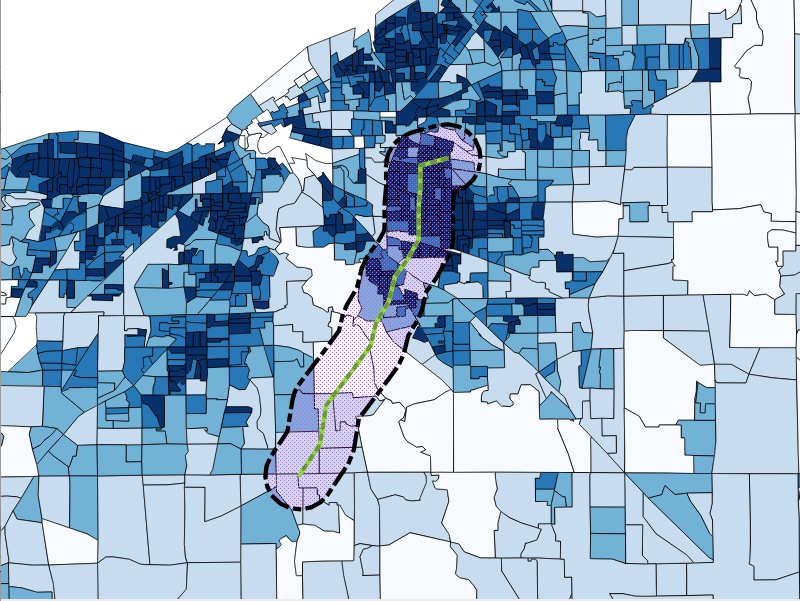

If we view the proposed trail in our favorite desktop GIS, we have the following:

In our case, we want to know the population within 1 mile of the trail, assuming that persons living within 1 mile of the trail are the ones most likely to use it, and thus most likely to be served by it.

To find out the population near this proposed trail, we overlay census block group population density information. Illustrated in the next screenshot is a 1-mile buffer around the proposed trail:

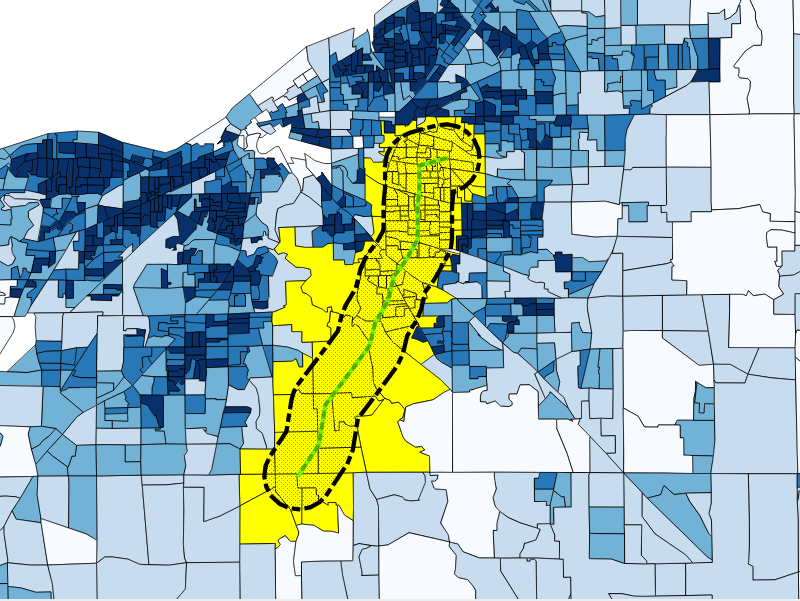

One of the things we might note about this census data is the wide range of census densities and census block group sizes. An approach to calculating the population would be to simply select all census blocks that intersect our area, as shown in the following screenshot:

This is a simple procedure that gives us an estimate of 130 to 288 people living within 1 mile of the trail, but looking at the shape of the selection, we can see that we are overestimating the population by taking the complete blocks in our estimate.

Similarly, if we just used the block groups whose centroids lay within 1 mile of our proposed trail alignment, we would underestimate the population.

Instead, we will make some useful assumptions. Block groups are designed to be moderately homogeneous within the block group population distribution. Assuming that this holds true for our data, we can assume that for a given block group, if 50% of the block group is within our target area, we can attribute half of the population of that block group to our estimate. Apply this to all our block groups, sum them, and we have a refined estimate that is likely to be better than pure intersects or centroid queries. Thus, we employ a proportional sum.