Second Edition

Copyright © 2018 Packt Publishing

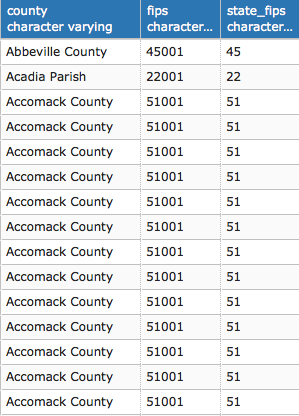

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

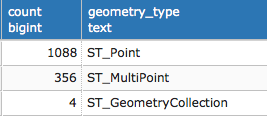

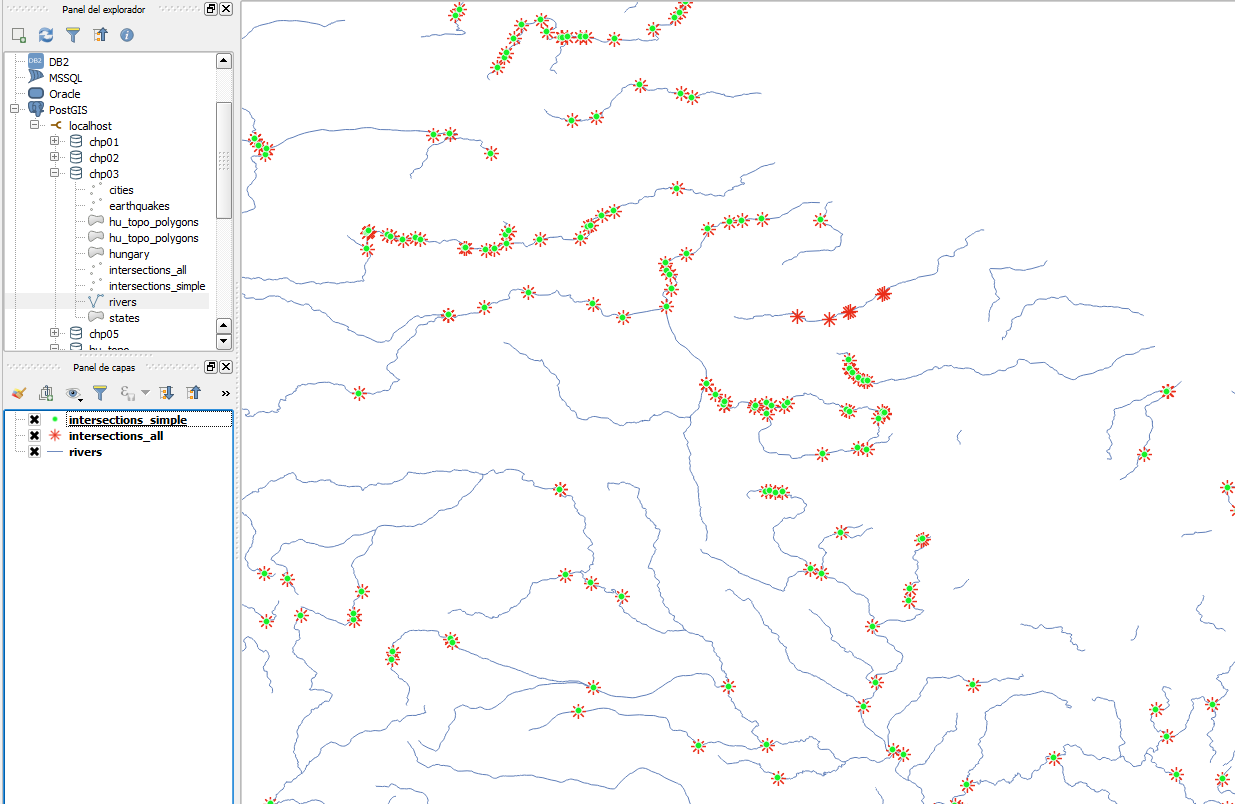

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the authors, nor Packt Publishing or its dealers and distributors, will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

Commissioning Editor: Merint Mathew

Acquisition Editors: Nitin Dasan, Shriram Shekhar

Content Development Editor: Nikhil Borkar

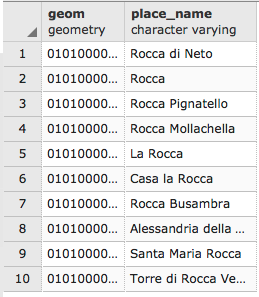

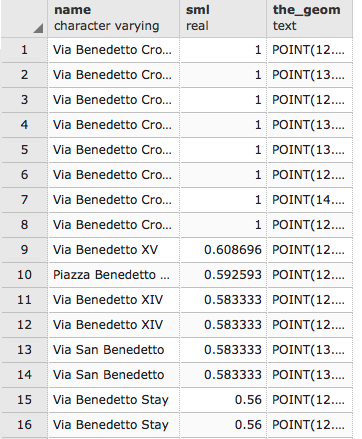

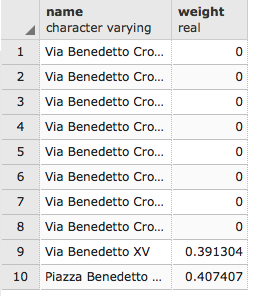

Technical Editor: Subhalaxmi Nadar

Copy Editor: Safis Editing

Project Coordinator: Ulhas Kambali

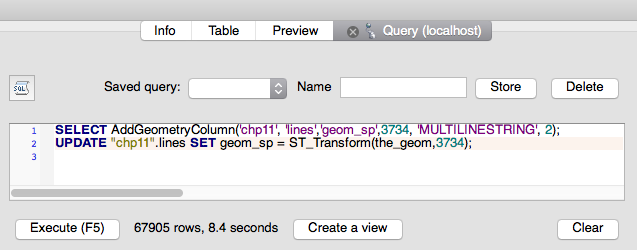

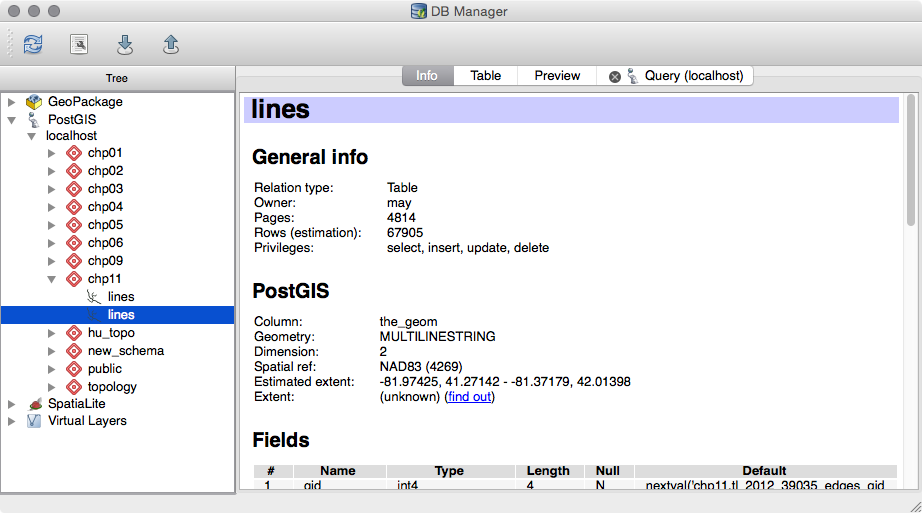

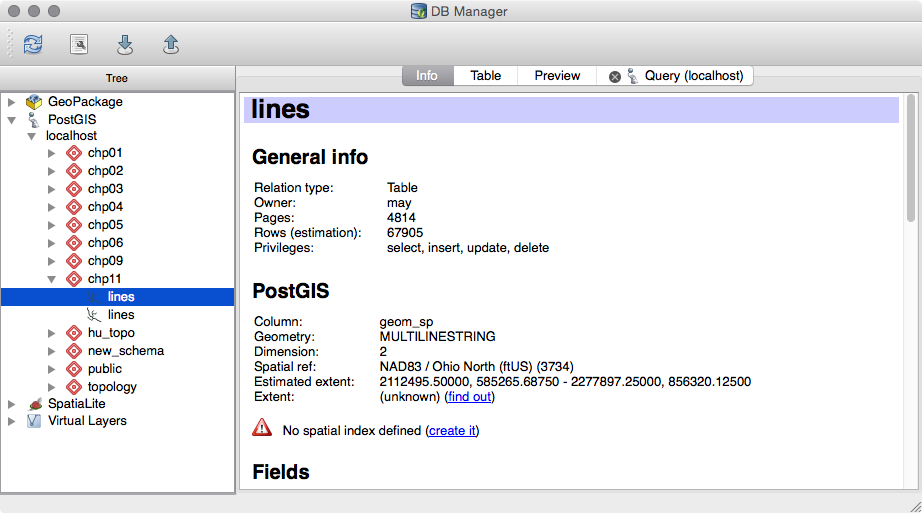

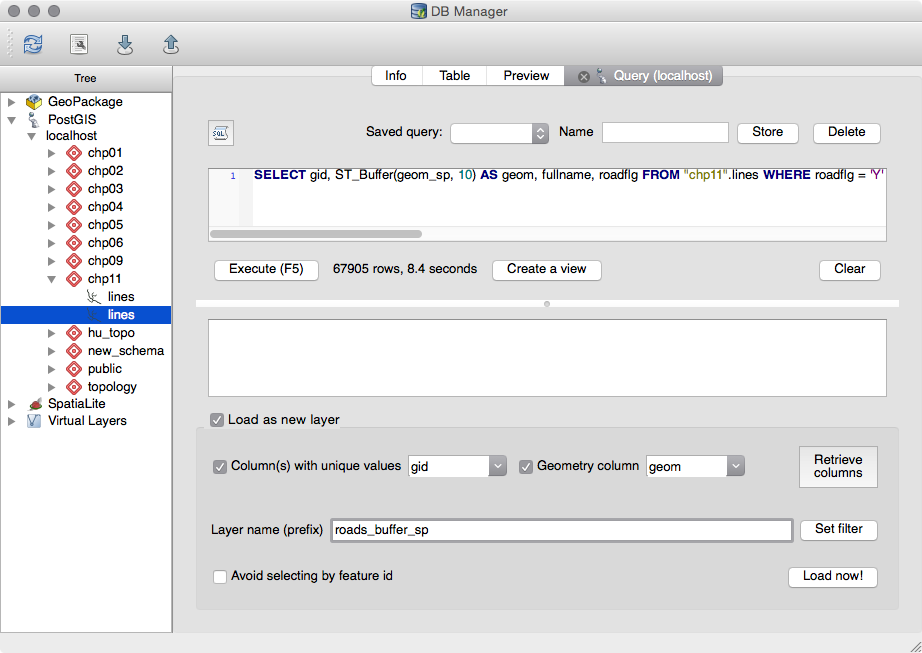

Proofreader: Safis Editing

Indexer: Mariammal Chettiyar

Graphics: Tania Dutta

Production Coordinator: Shantanu Zagade

First published: January 2014

Second edition: March 2018

Production reference: 1270318

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham

B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78829-932-9

Mapt is an online digital library that gives you full access to over 5,000 books and videos, as well as industry leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career. For more information, please visit our website.

Spend less time learning and more time coding with practical eBooks and Videos from over 4,000 industry professionals

Improve your learning with Skill Plans built especially for you

Get a free eBook or video every month

Mapt is fully searchable

Copy and paste, print, and bookmark content

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at service@packtpub.com for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters, and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

Mayra Zurbarán is a Colombian geogeek currently pursuing her PhD in geoprivacy. She has a BS in computer science from Universidad del Norte and is interested in the intersection of ethical location data management, free and open source software, and GIS. She is a Pythonista with a marked preference for the PostgreSQL database. Mayra is a member of the Geomatics and Earth Observation laboratory (GEOlab) at Politecnico di Milano and is also a contributor to the FOSS community.

Pedro M. Wightman is an associate professor at the Systems Engineering Department of Universidad del Norte, Barranquilla, Colombia. With a PhD in computer science from the University of South Florida, he's a researcher in location-based information systems, wireless sensor networks, and virtual and augmented reality, among other fields. Father of two beautiful and smart girls, he's also a rookie writer of short stories, science fiction fan, time travel enthusiast, and is worried about how to survive apocalyptic solar flares.

Paolo Corti is an environmental engineer with 20 years of experience in the GIS field, currently working as a Geospatial Engineer Fellow at the Center for Geographic Analysis at Harvard University. He is an advocate of open source geospatial technologies and Python, an OSGeo Charter member, and a member of the pycsw and GeoNode Project Steering Committees. He is a coauthor of the first edition of this book and the reviewer for the first and second editions of the Mastering QGIS book by Packt.

Stephen Vincent Mather has worked in the geospatial industry for 15 years, having always had a flair for geospatial analyses in general, especially those at the intersection of Geography and Ecology. His work in open-source geospatial databases started 5 years ago with PostGIS and he immediately began using PostGIS as an analytic tool, attempting a range of innovative and sometimes bleeding-edge techniques (although he admittedly prefers the cutting edge).

Thomas J Kraft is currently a Planning Technician at Cleveland Metroparks after beginning as a GIS intern in 2011. He graduated with Honors from Cleveland State University in 2012, majoring in Environmental Science with an emphasis on GIS. When not in front of a computer, he spends his weekends landscaping and in the outdoors in general.

Bborie Park has been breaking (and subsequently fixing) computers for most of his life. His primary interests involve developing end-to-end pipelines for spatial datasets. He is an active contributor to the PostGIS project and is a member of the PostGIS Steering Committee. He happily resides with his wife Nicole in the San Francisco Bay Area.

If you're interested in becoming an author for Packt, please visit authors.packtpub.com and apply today. We have worked with thousands of developers and tech professionals, just like you, to help them share their insight with the global tech community. You can make a general application, apply for a specific hot topic that we are recruiting an author for, or submit your own idea.

How close is the nearest hospital from my children's school? Where were the property crimes in my city for the last three months? What is the shortest route from my home to my office? What route should I prescribe for my company's delivery truck to maximize equipment utilization and minimize fuel consumption? Where should the next fire station be built to minimize response times?

People ask these questions, and others like them, every day all over this planet. Answering these questions requires a mechanism capable of thinking in two or more dimensions. Historically, desktop GIS applications were the only ones capable of answering these questions. This method—though completely functional—is not viable for the average person; most people do not need all the functionalities that these applications can offer, or they do not know how to use them. In addition, more and more location-based services offer the specific features that people use and are accessible even from their smartphones. Clearly, the massification of these services requires the support of a robust backend platform to process a large number of geographical operations.

Since scalability, support for large datasets, and a direct input mechanism are required or desired, most developers have opted to adopt spatial databases as their support platform. There are several spatial database software available, some proprietary and others open source. PostGIS is an open source spatial database software available, and probably the most accessible of all spatial database software.

PostGIS runs as an extension to provide spatial capabilities to PostgreSQL databases. In this capacity, PostGIS permits the inclusion of spatial data alongside data typically found in a database. By having all the data together, questions such as "What is the rank of all the police stations, after taking into account the distance for each response time?" are possible. New or enhanced capabilities are possible by building upon the core functions provided by PostGIS and the inherent extensibility of PostgreSQL. Furthermore, this book also includes an invitation to include location privacy protection mechanisms in new GIS applications and in location-based services so that users feel respected and not necessarily at risk for sharing their information, especially information as sensitive as their whereabouts.

PostGIS Cookbook, Second Edition uses a problem-solving approach to help you acquire a solid understanding of PostGIS. It is hoped that this book provides answers to some common spatial questions and gives you the inspiration and confidence to use and enhance PostGIS in finding solutions to challenging spatial problems.

This book is written for those who are looking for the best method to solve their spatial problems using PostGIS. These problems can be as simple as finding the nearest restaurant to a specific location, or as complex as finding the shortest and/or most efficient route from point A to point B.

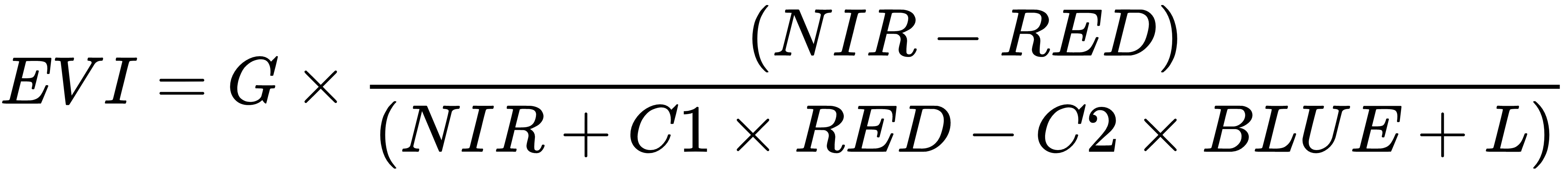

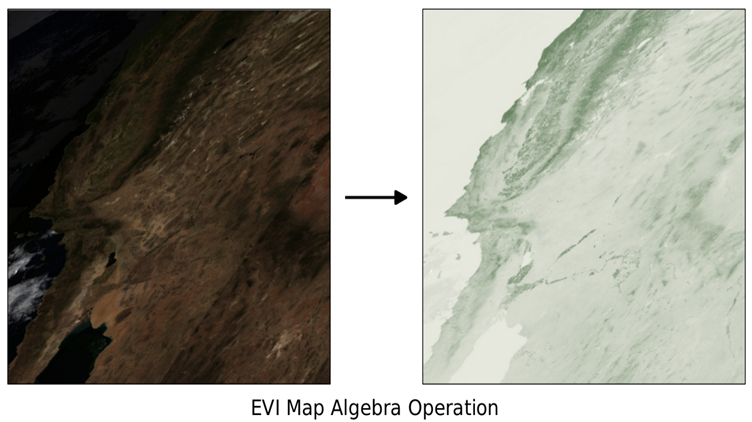

For readers who are just starting out with PostGIS, or even with spatial datasets, this book is structured to help them become comfortable and proficient at running spatial operations in the database. For experienced users, the book provides opportunities to dive into advanced topics such as point clouds, raster map-algebra, and PostGIS programming.

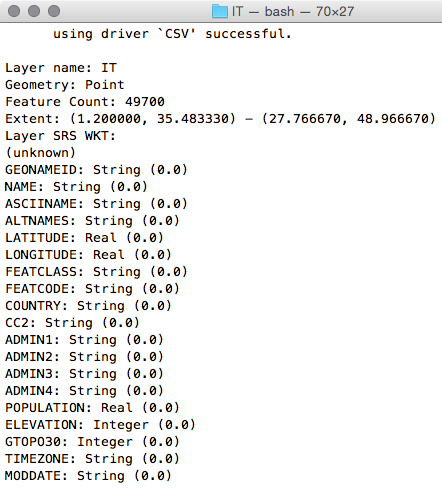

Chapter 1, Moving Data In and Out of PostGIS, covers the processes available for importing and exporting spatial and non-spatial data to and from PostGIS. These processes include the use of utilities provided by PostGIS and by third parties, such as GDAL/OGR.

Chapter 2, Structures That Work, discusses how to organize PostGIS data using mechanisms available through PostgreSQL. These mechanisms are used to normalize potentially unclean and unstructured import data.

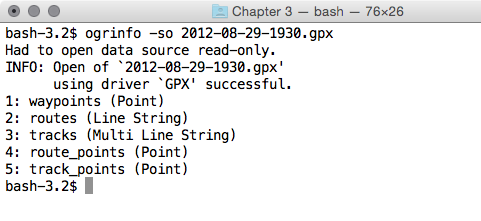

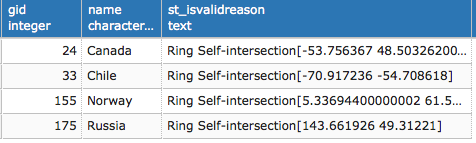

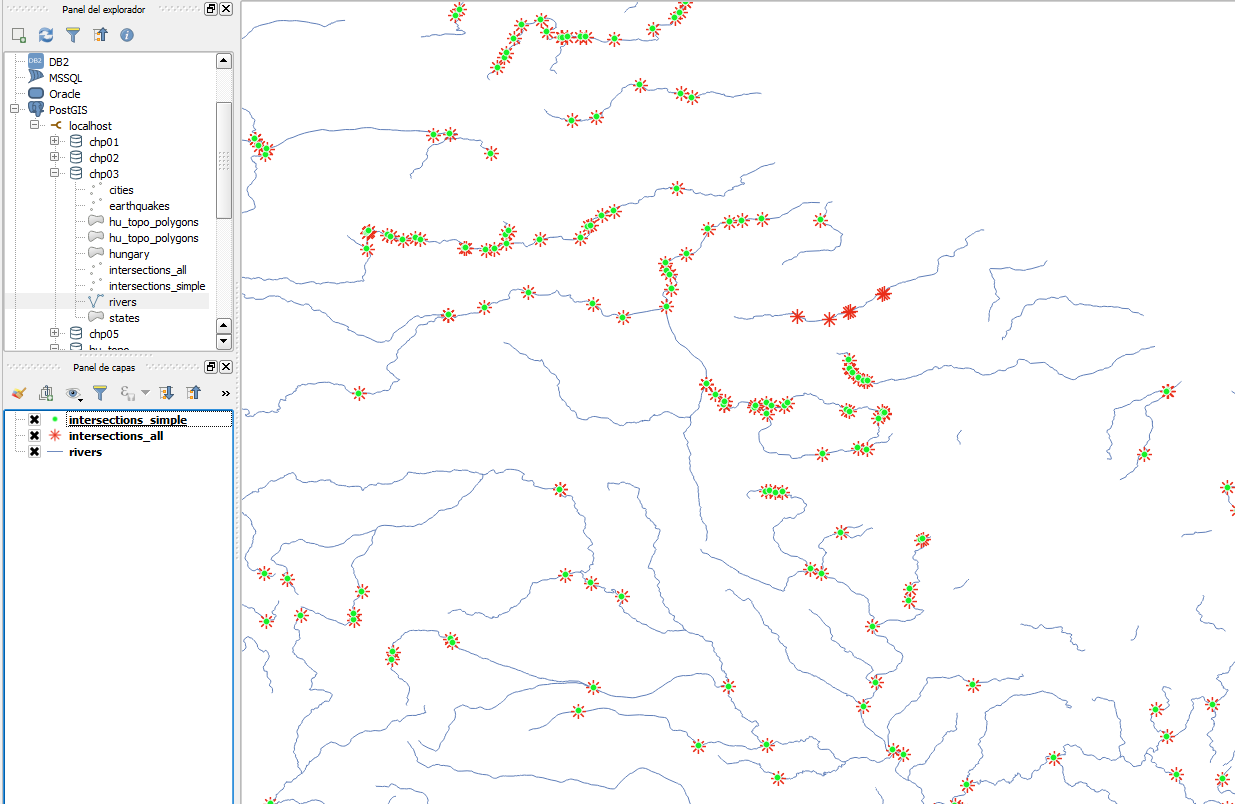

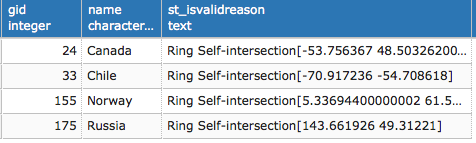

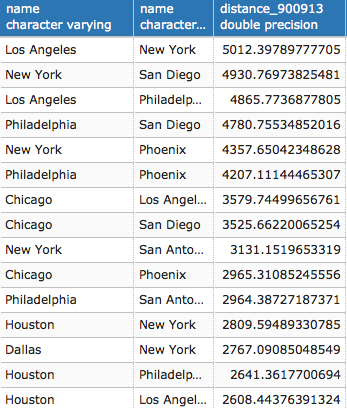

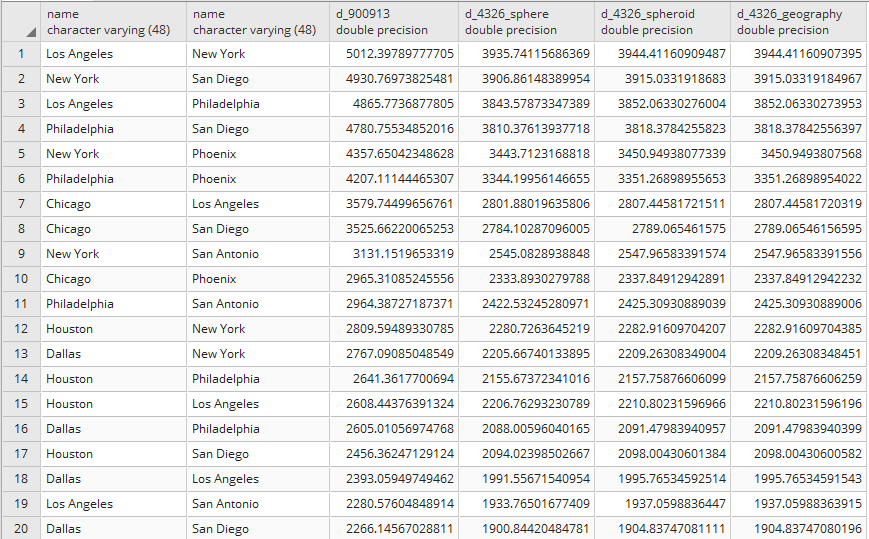

Chapter 3, Working with Vector Data – The Basics, introduces PostGIS operations commonly done on vectors, known as geometries and geographies in PostGIS. Operations covered include the processing of invalid geometries, determining relationships between geometries, and simplifying complex geometries.

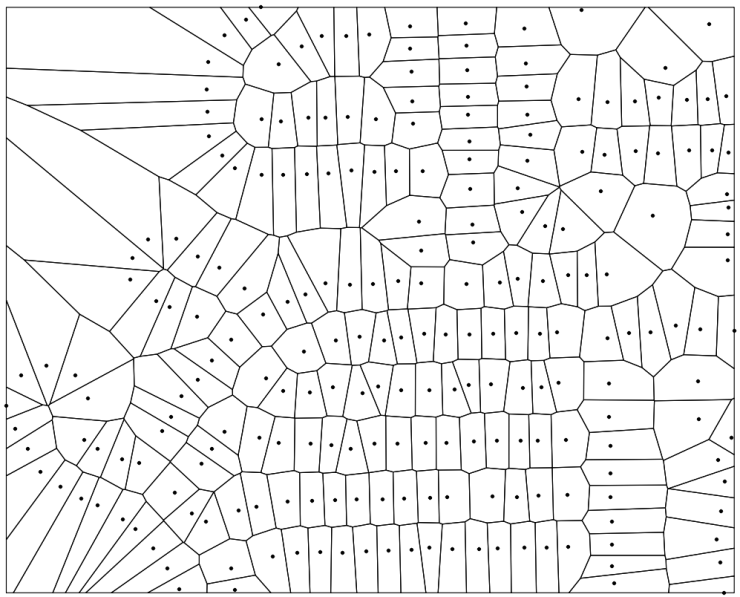

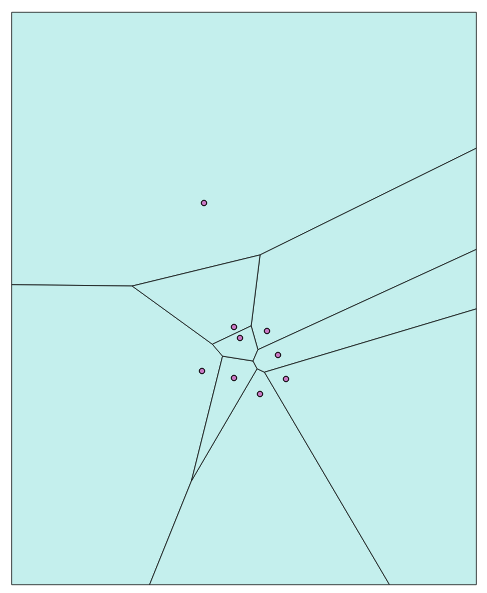

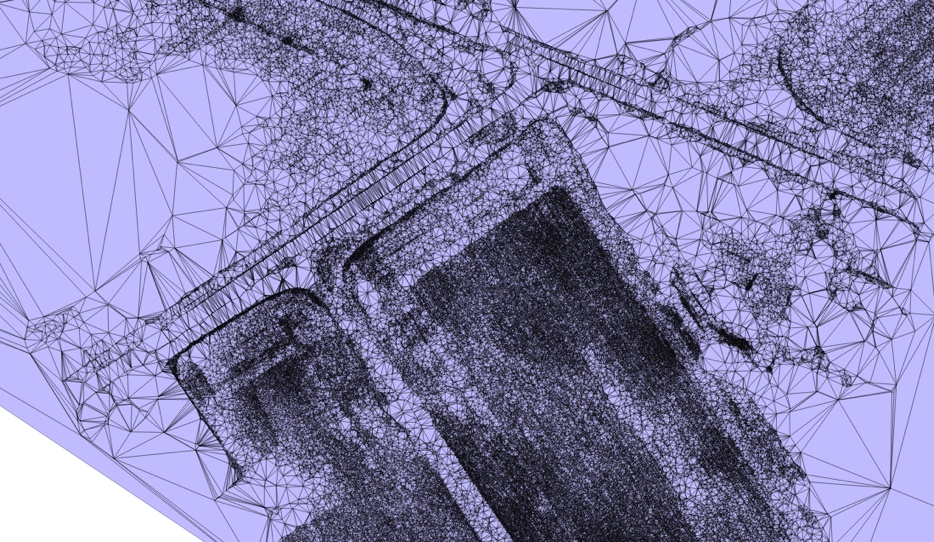

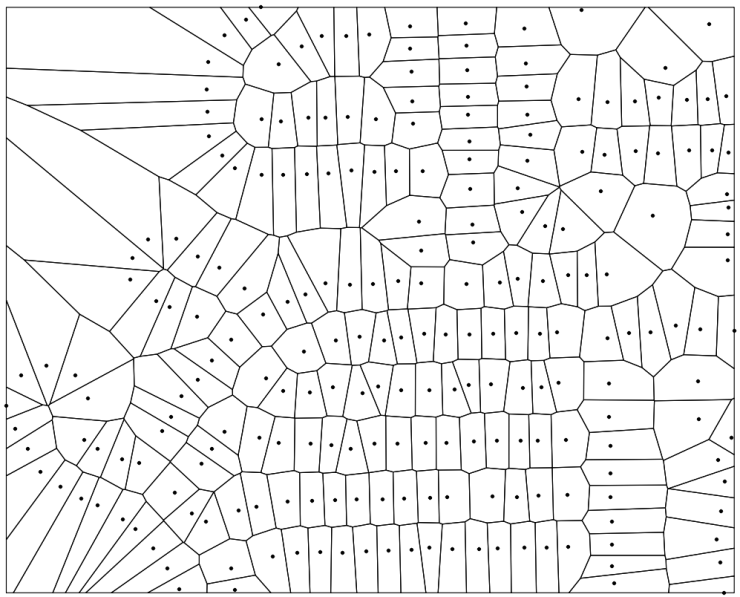

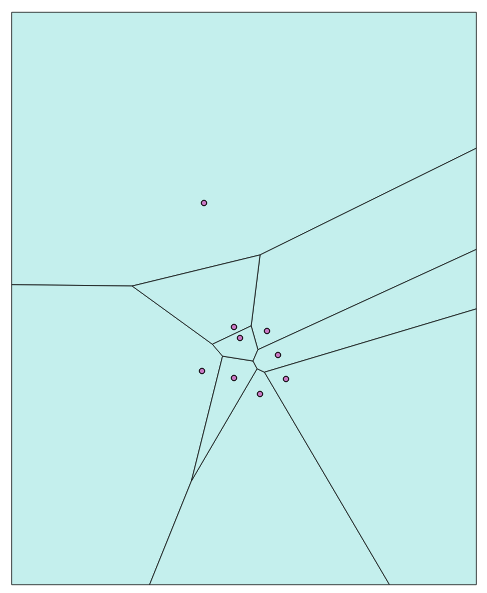

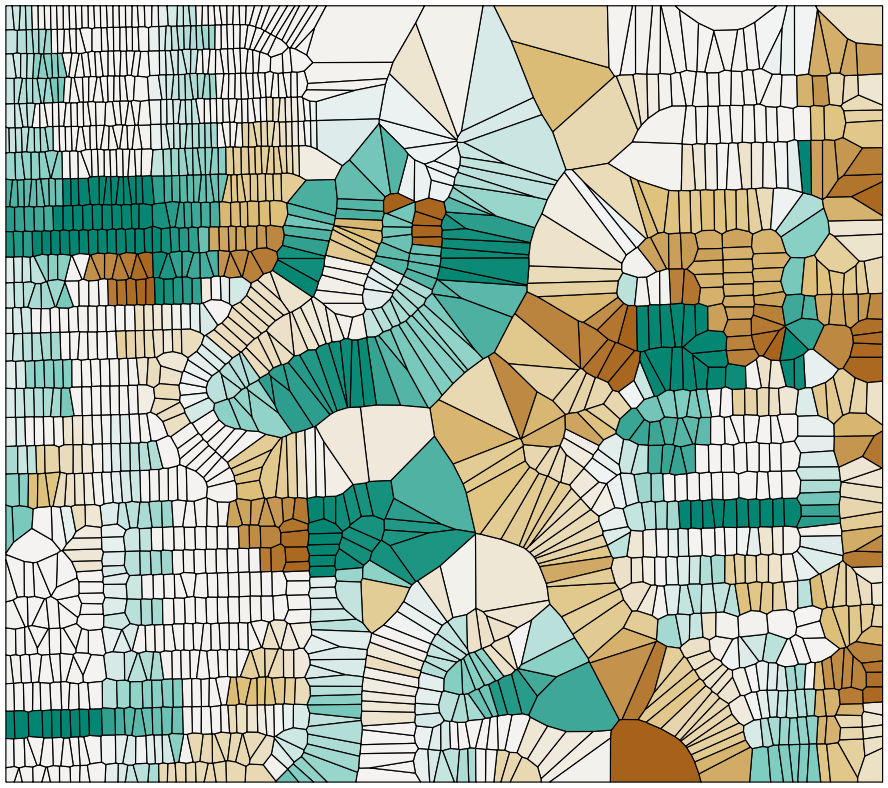

Chapter 4, Working with Vector Data – Advanced Recipes, dives into advanced topics for analyzing geometries. You will learn how to make use of KNN filters to increase the performance of proximity queries, create polygons from LiDAR data, and compute Voronoi cells usable in neighborhood analyses.

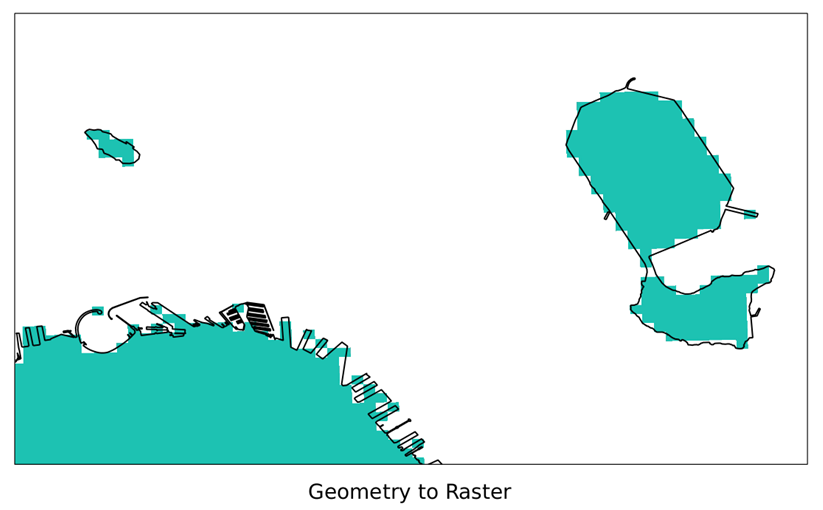

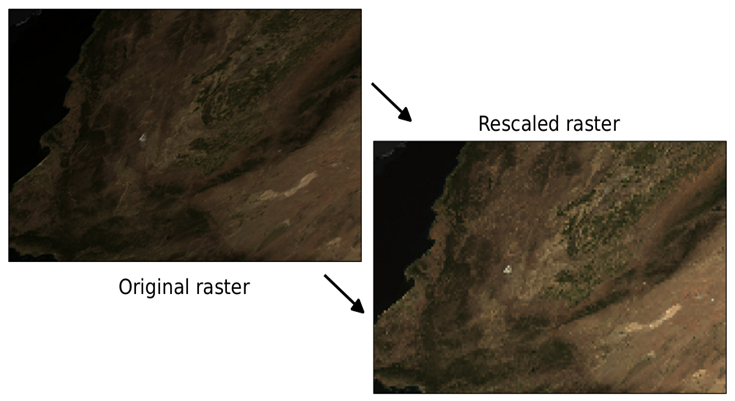

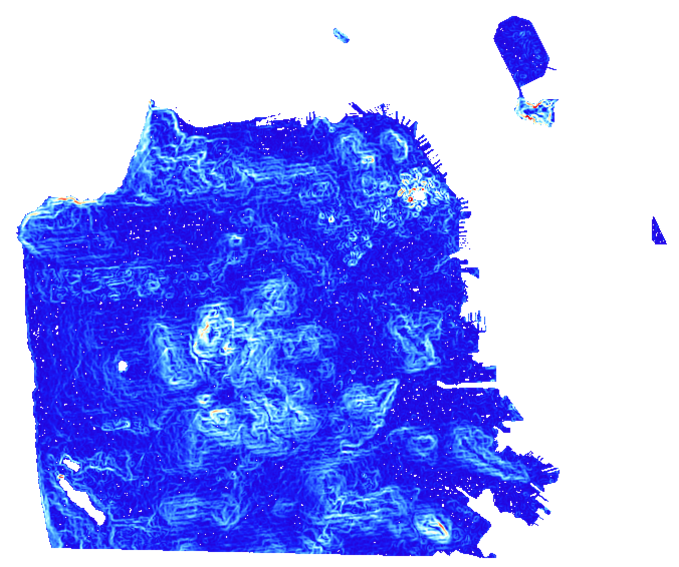

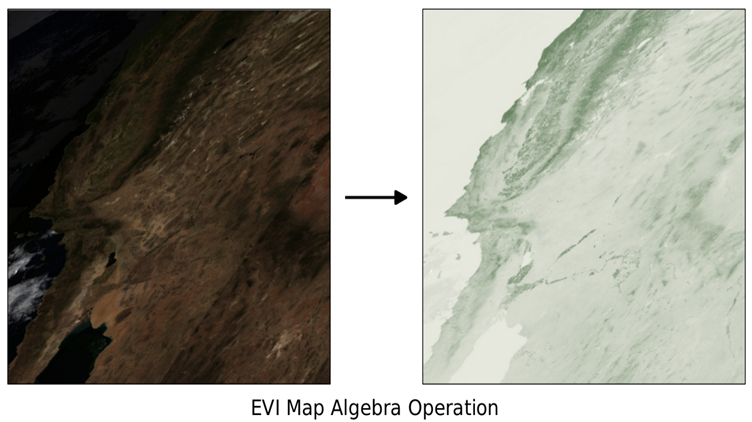

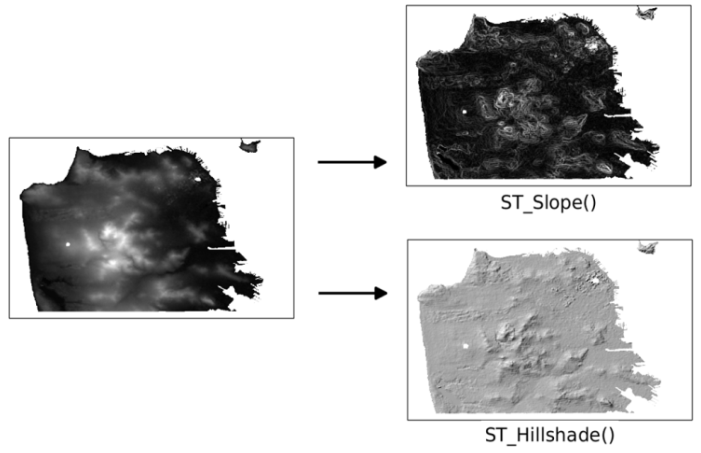

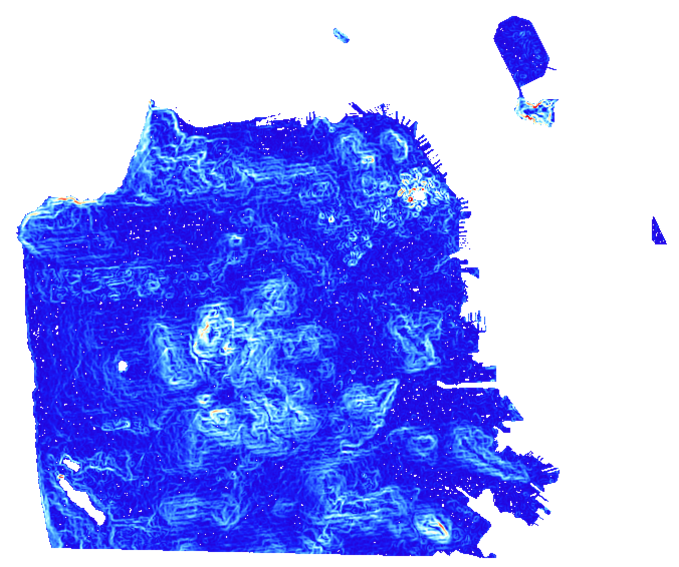

Chapter 5, Working with Raster Data, presents a realistic workflow for operating on rasters in PostGIS. You will learn how to import a raster, modify the raster, conduct analysis on the raster, and export the raster in standard raster formats.

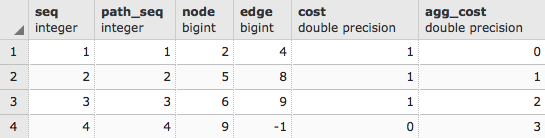

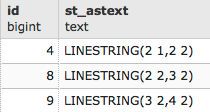

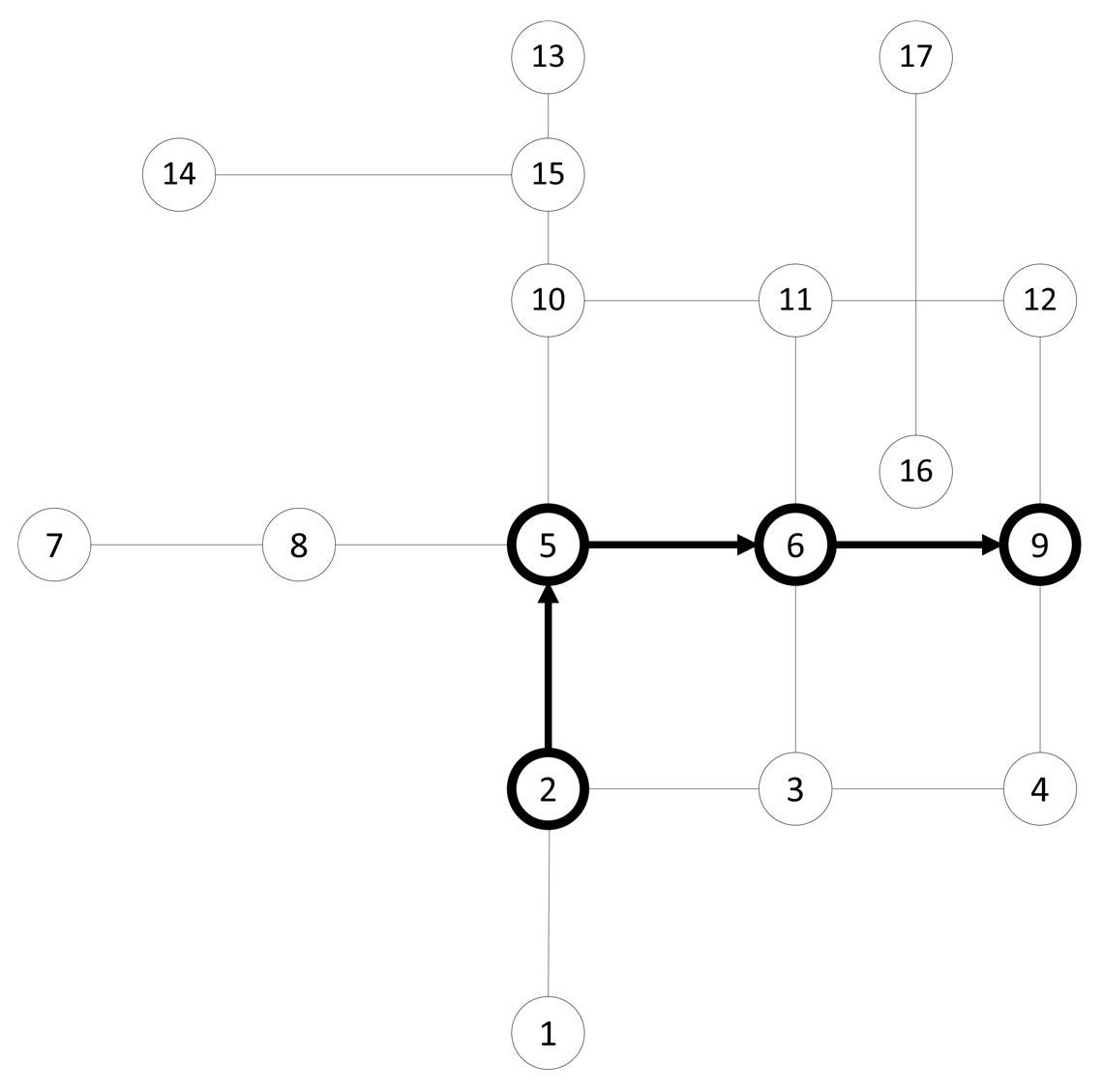

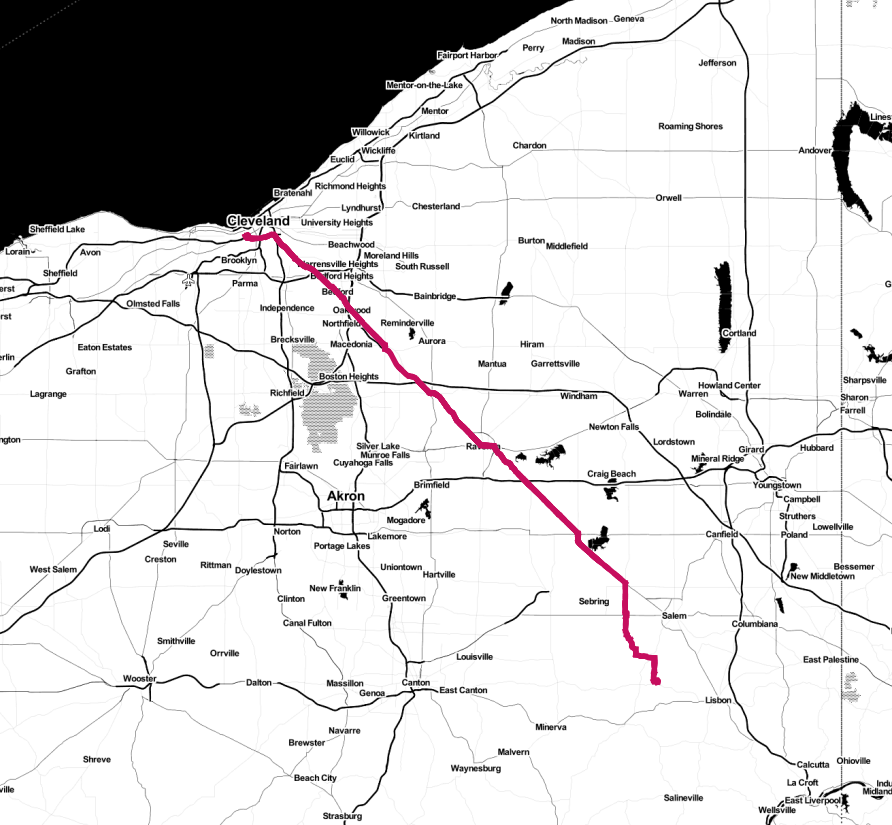

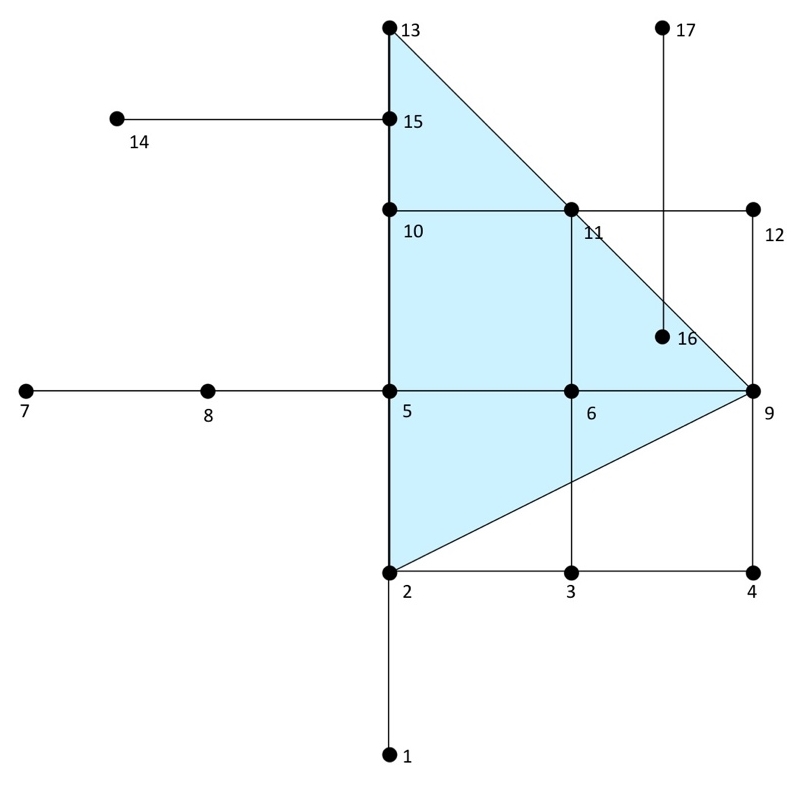

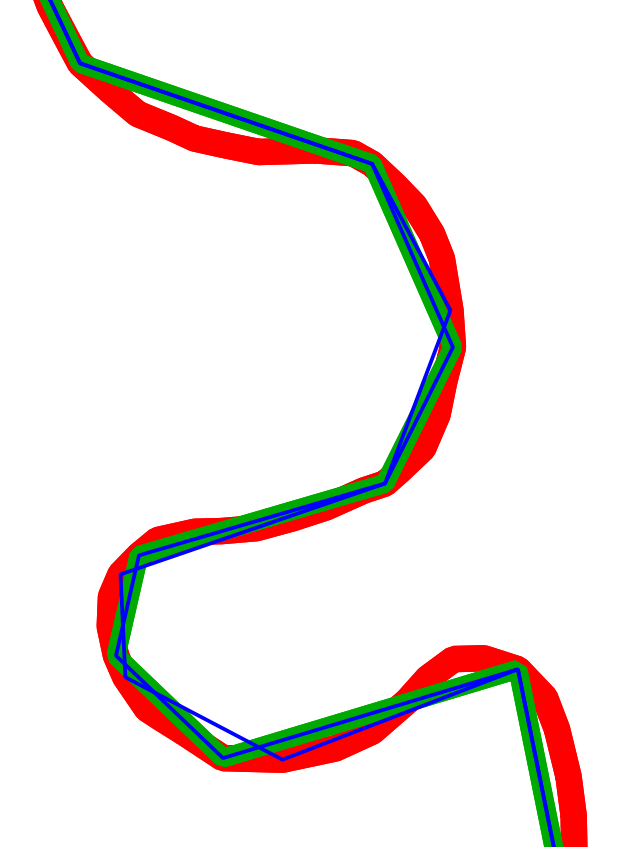

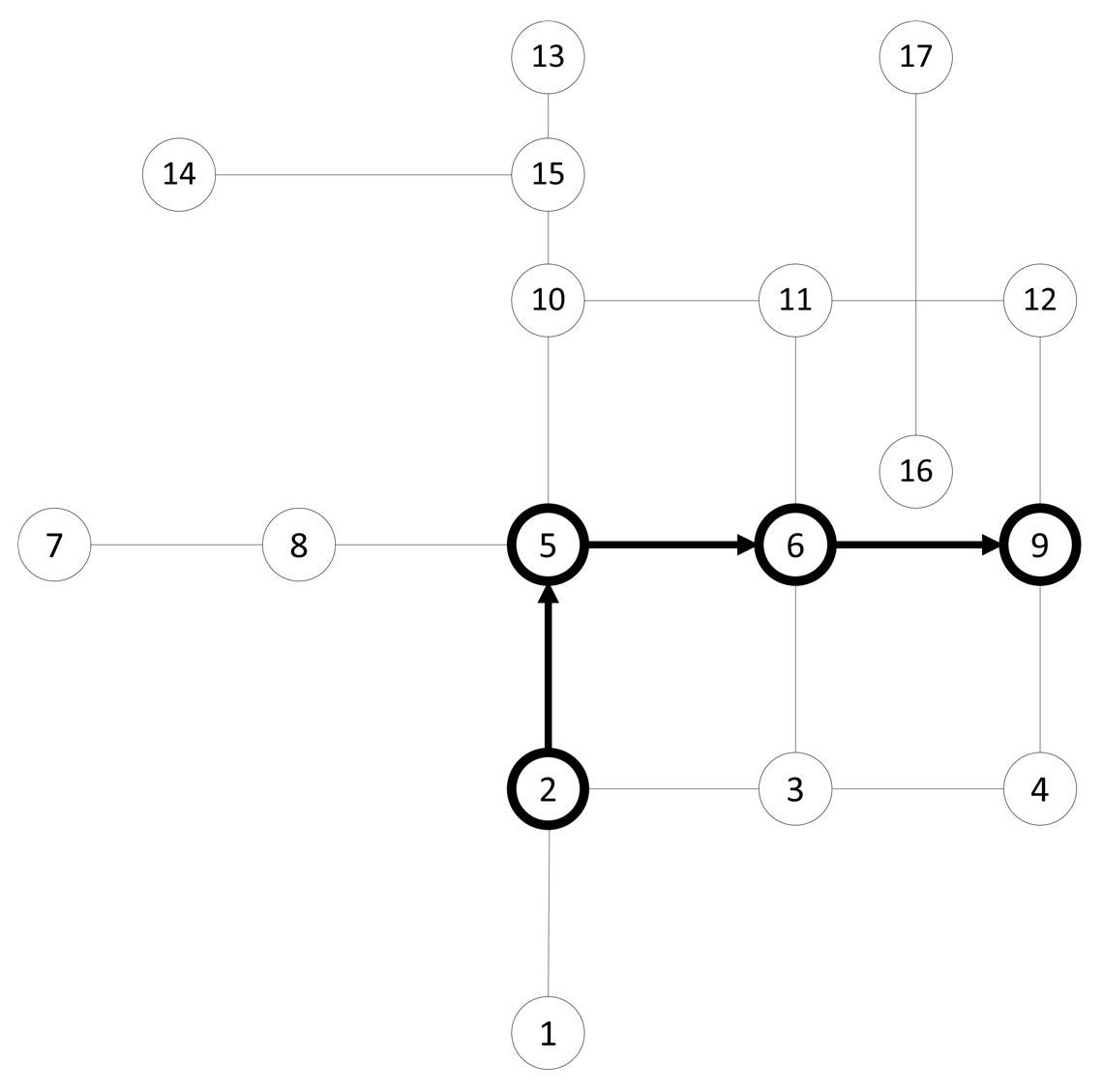

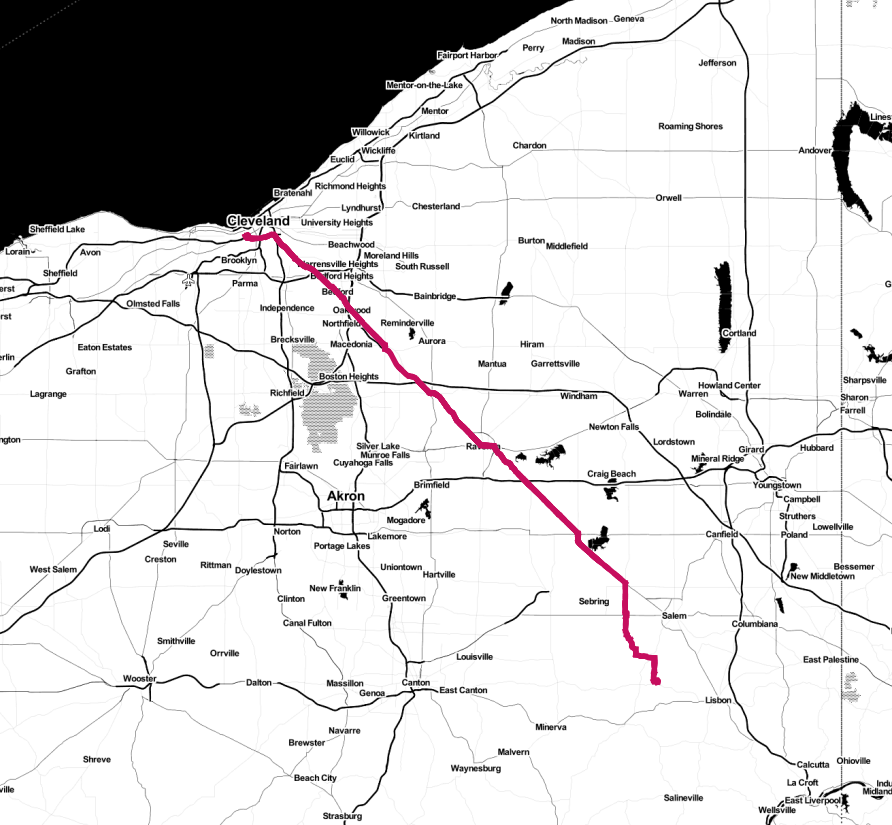

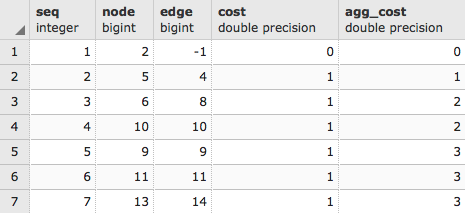

Chapter 6, Working with pgRouting, introduces the pgRouting extension, which brings graph traversal and analysis capabilities to PostGIS. The recipes in this chapter answer real-world questions of conditionally navigating from point A to point B and accurately modeling complex routes, such as waterways.

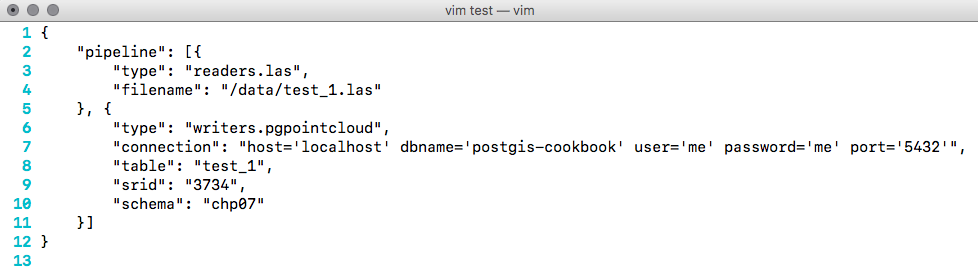

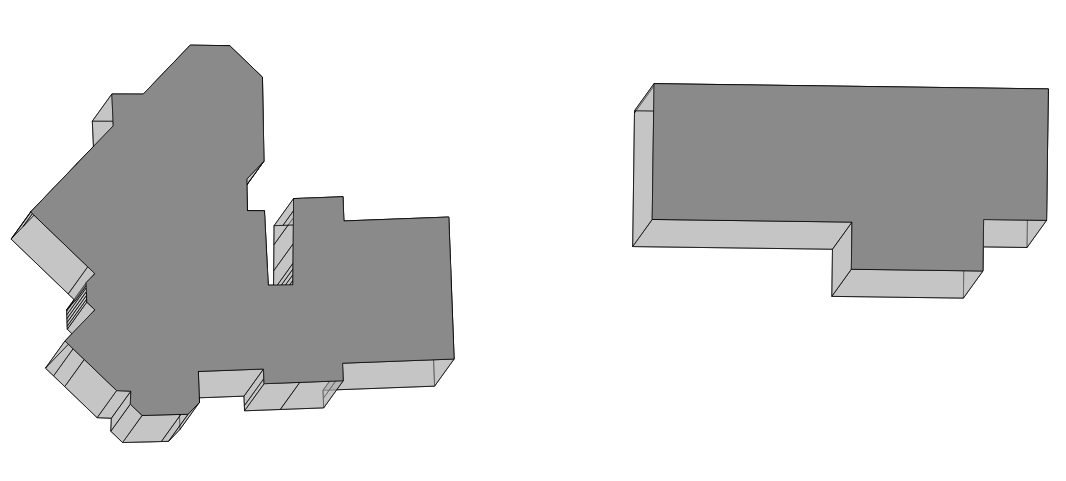

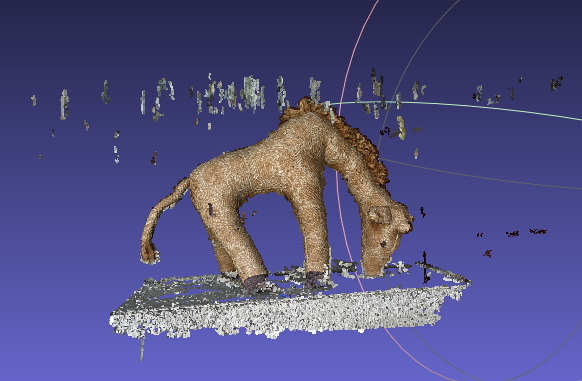

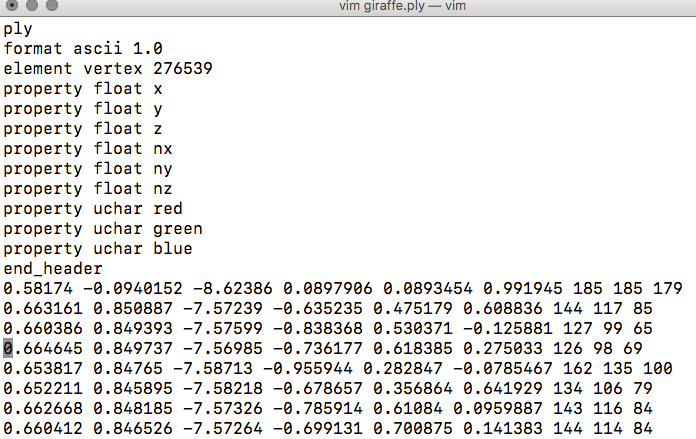

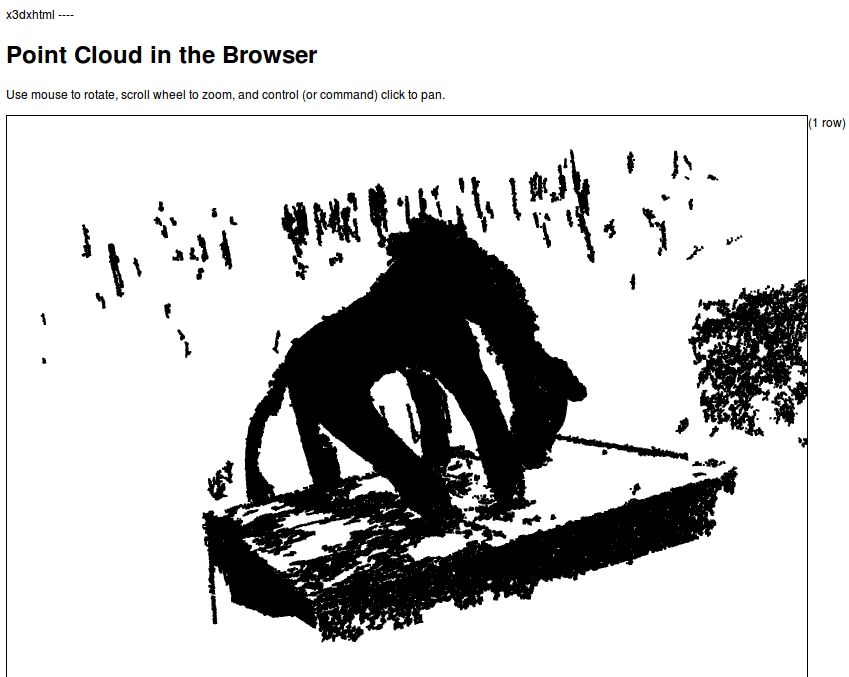

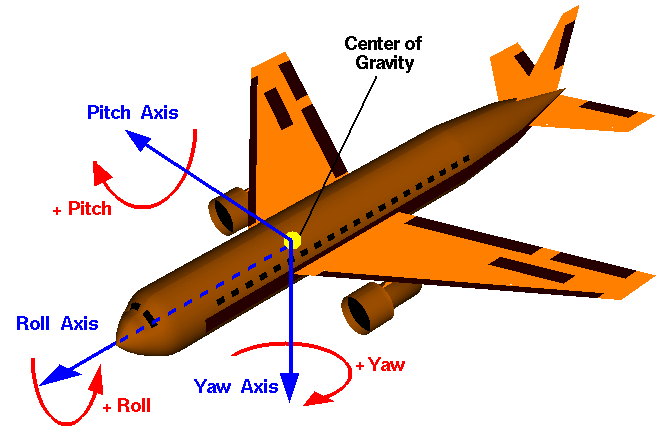

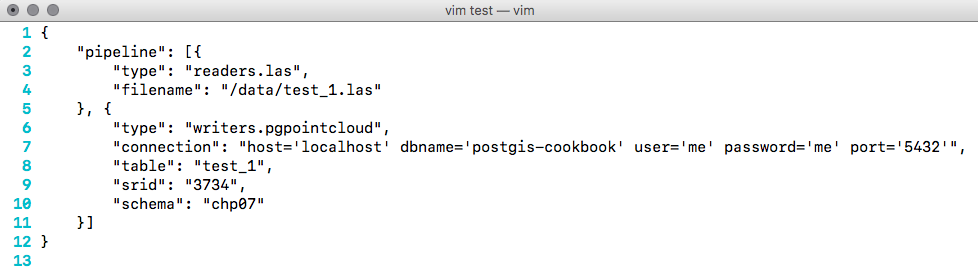

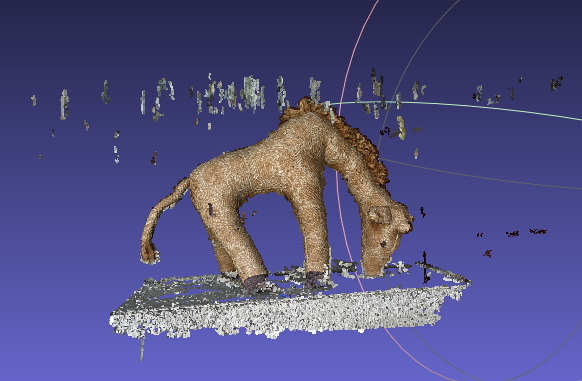

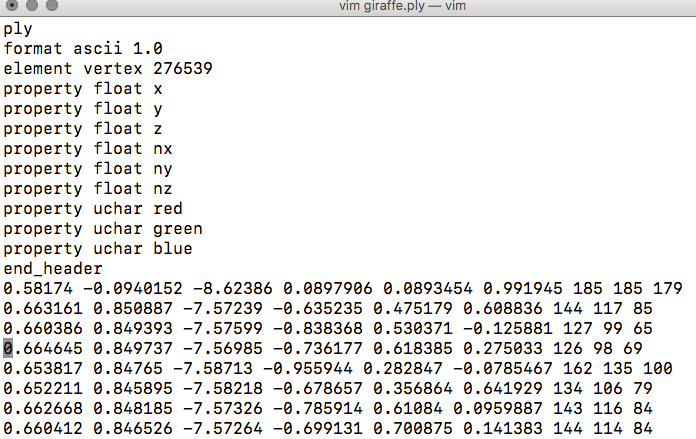

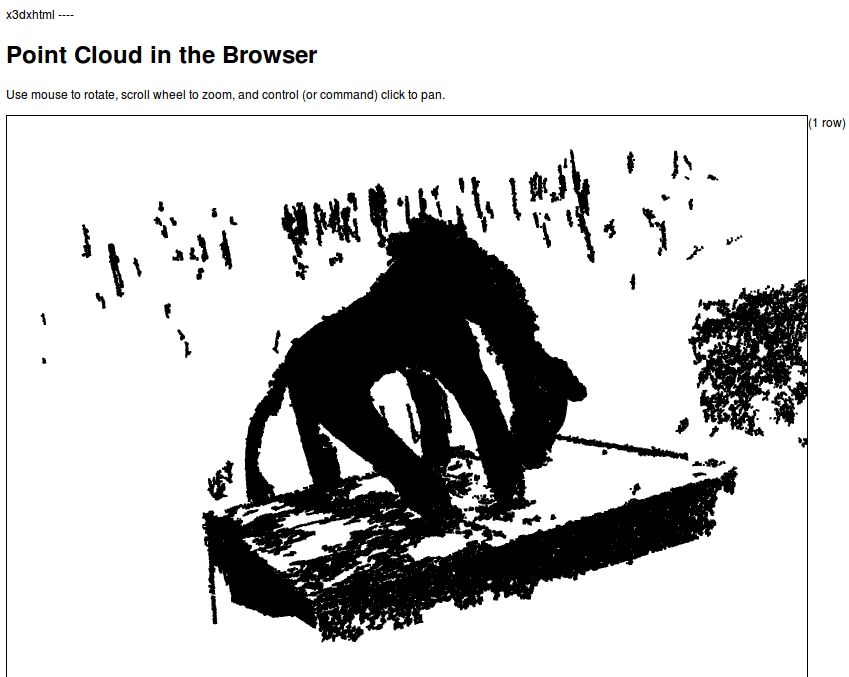

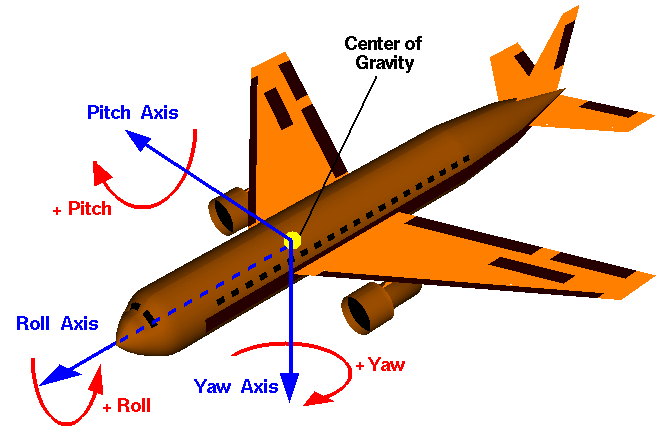

Chapter 7, Into the Nth Dimension, focuses on the tools and techniques used to process and analyze multidimensional spatial data in PostGIS, including LiDAR-sourced point clouds. Topics covered include the loading of point clouds into PostGIS, creating 2.5D and 3D geometries from point clouds, and the application of several photogrammetry principles.

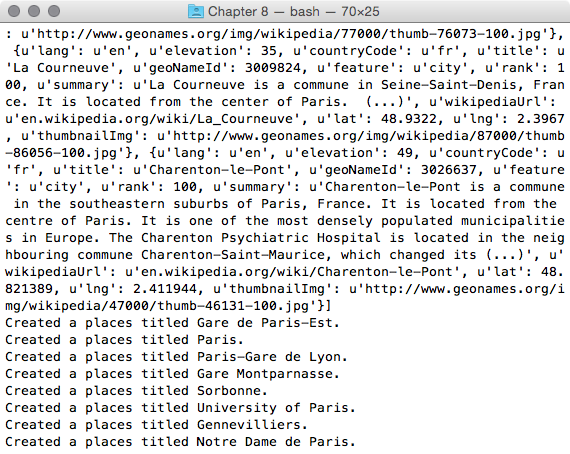

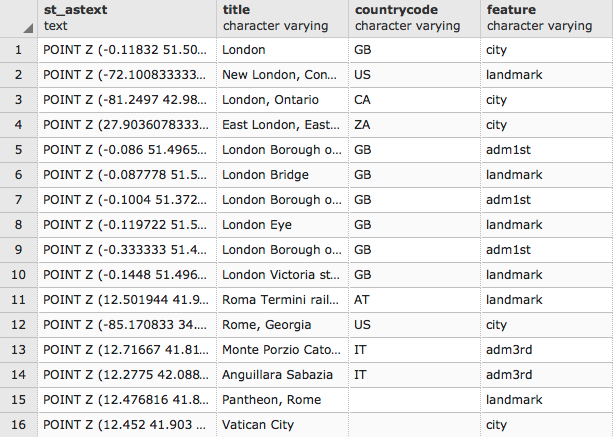

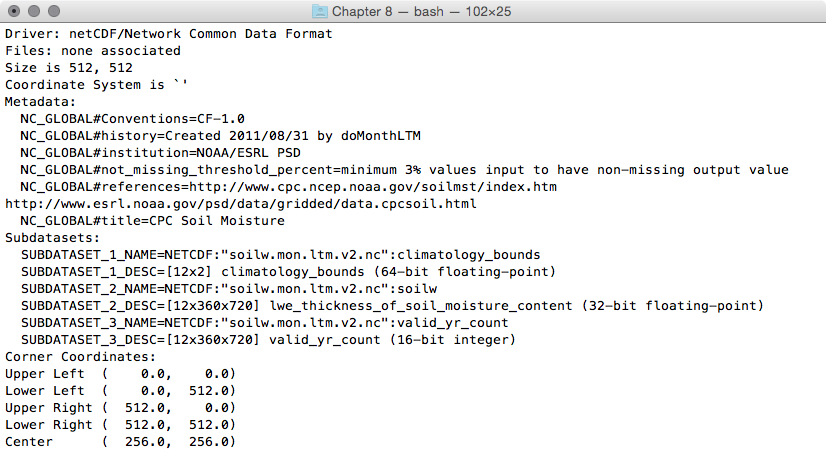

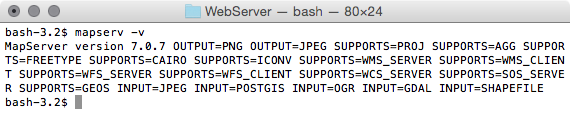

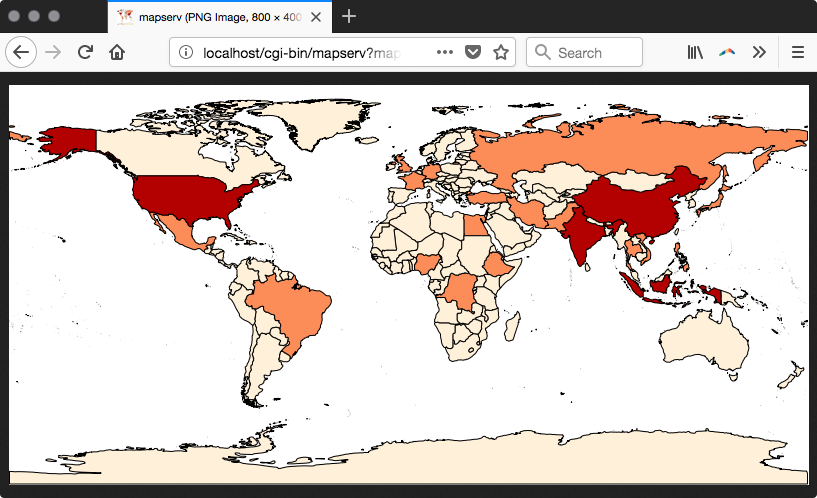

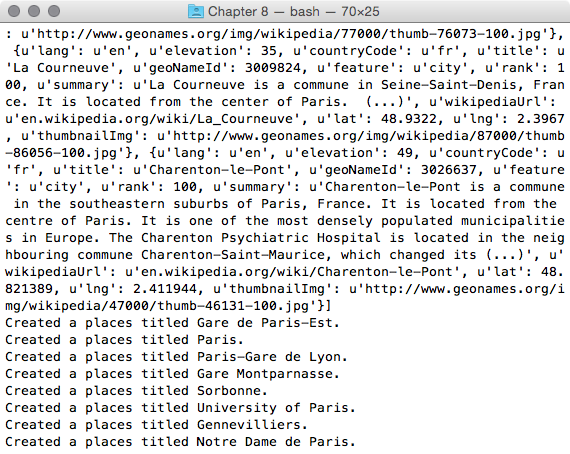

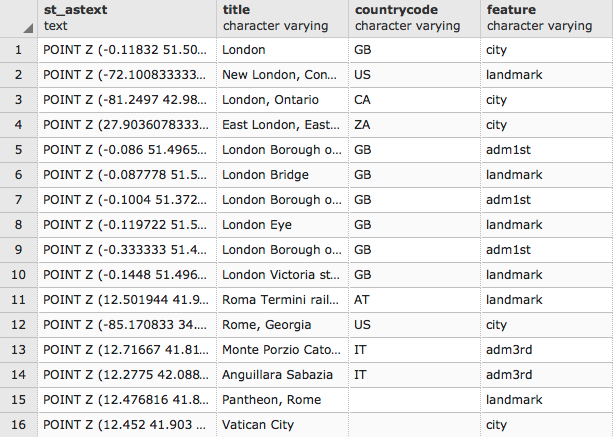

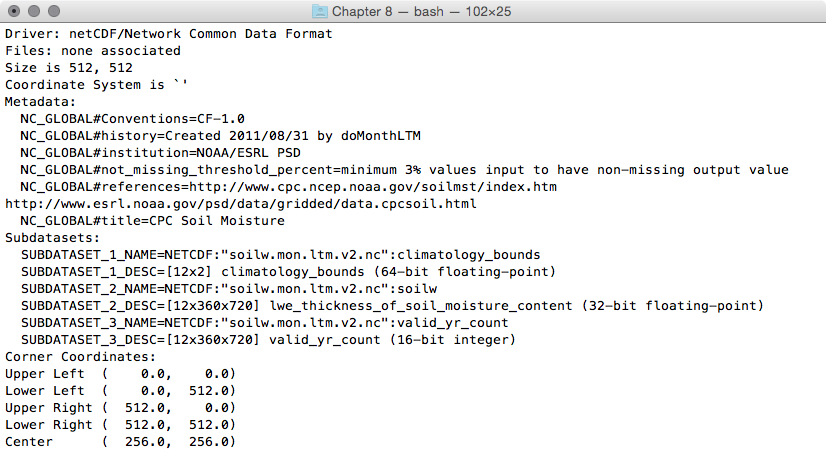

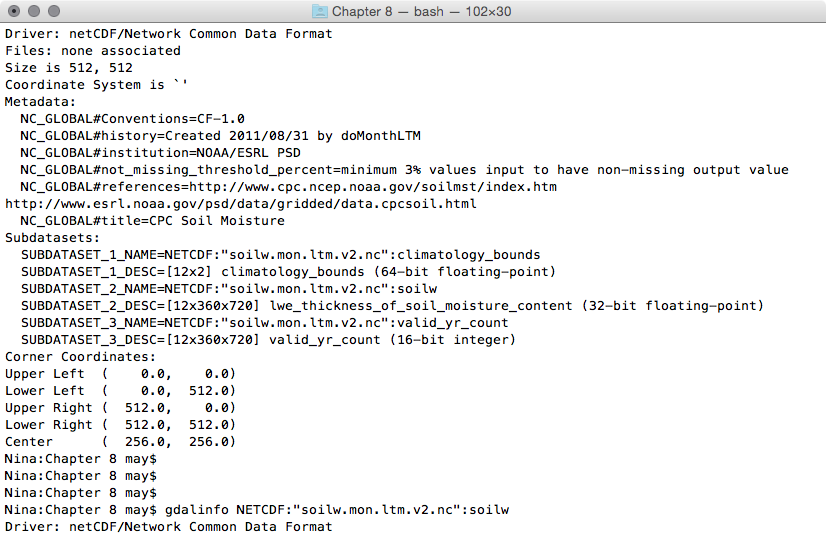

Chapter 8, PostGIS Programming, shows how to use the Python language to write applications that operate on and interact with PostGIS. The applications written include methods to read and write external datasets to and from PostGIS, as well as a basic geocoding engine using OpenStreetMap datasets.

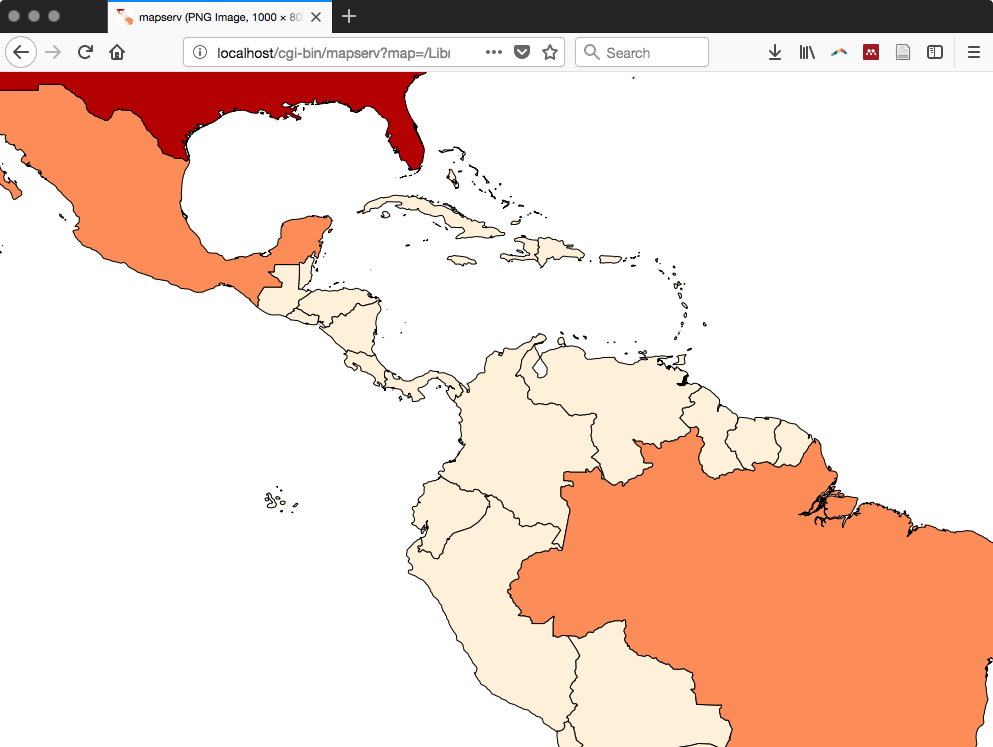

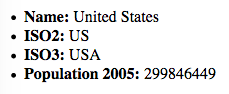

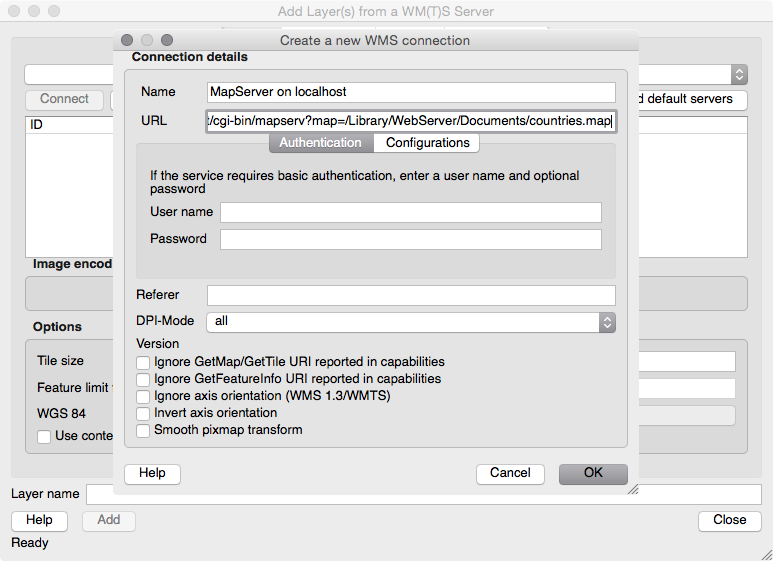

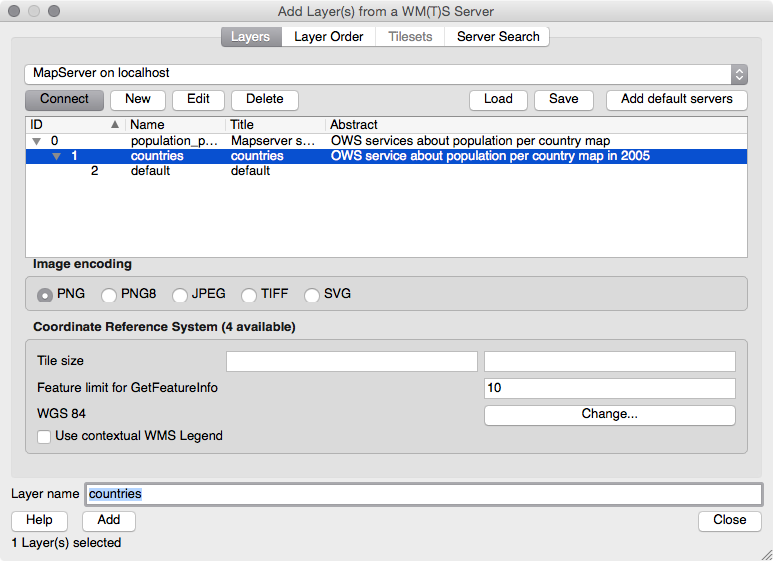

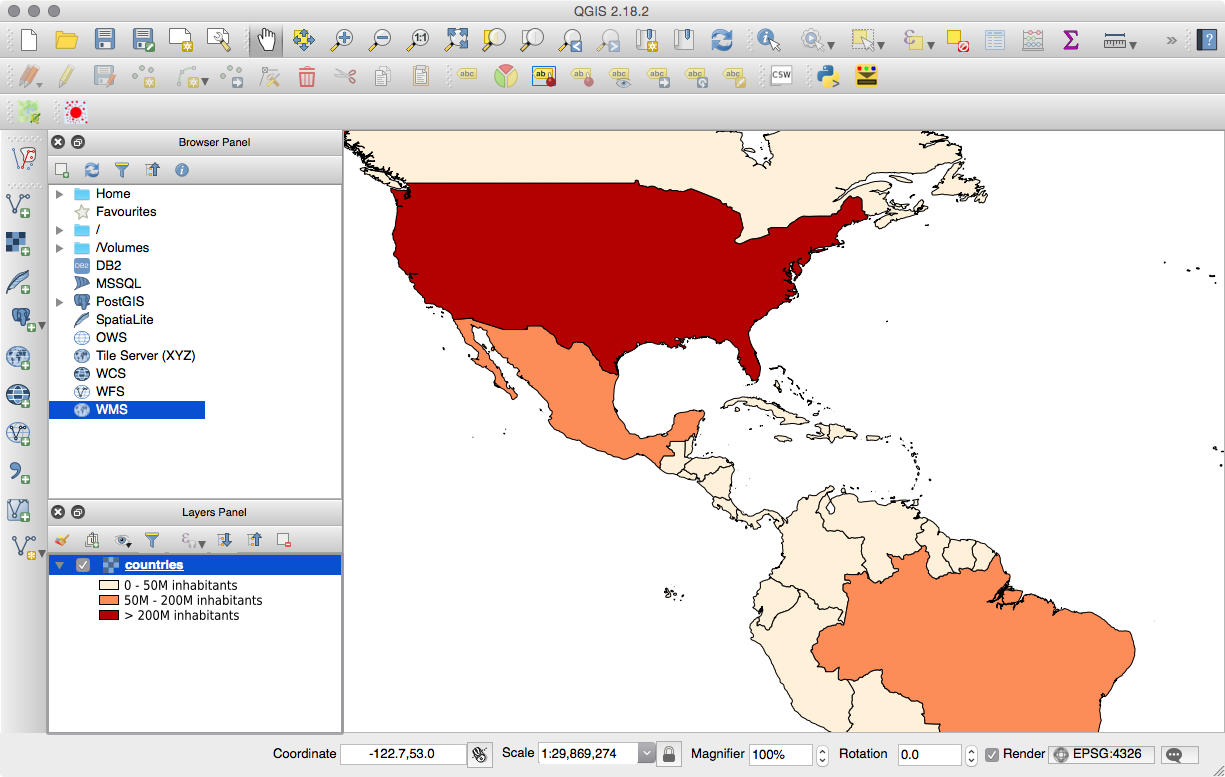

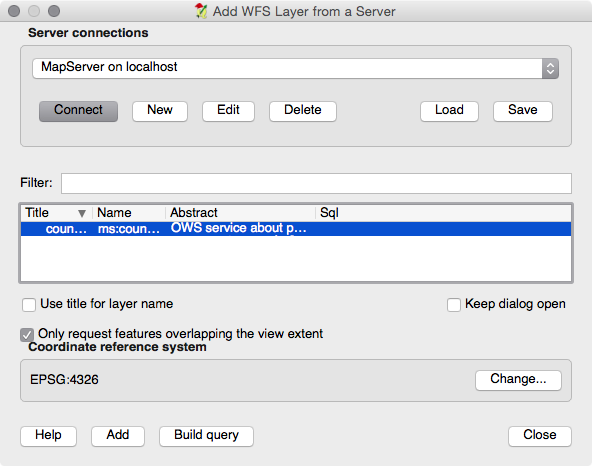

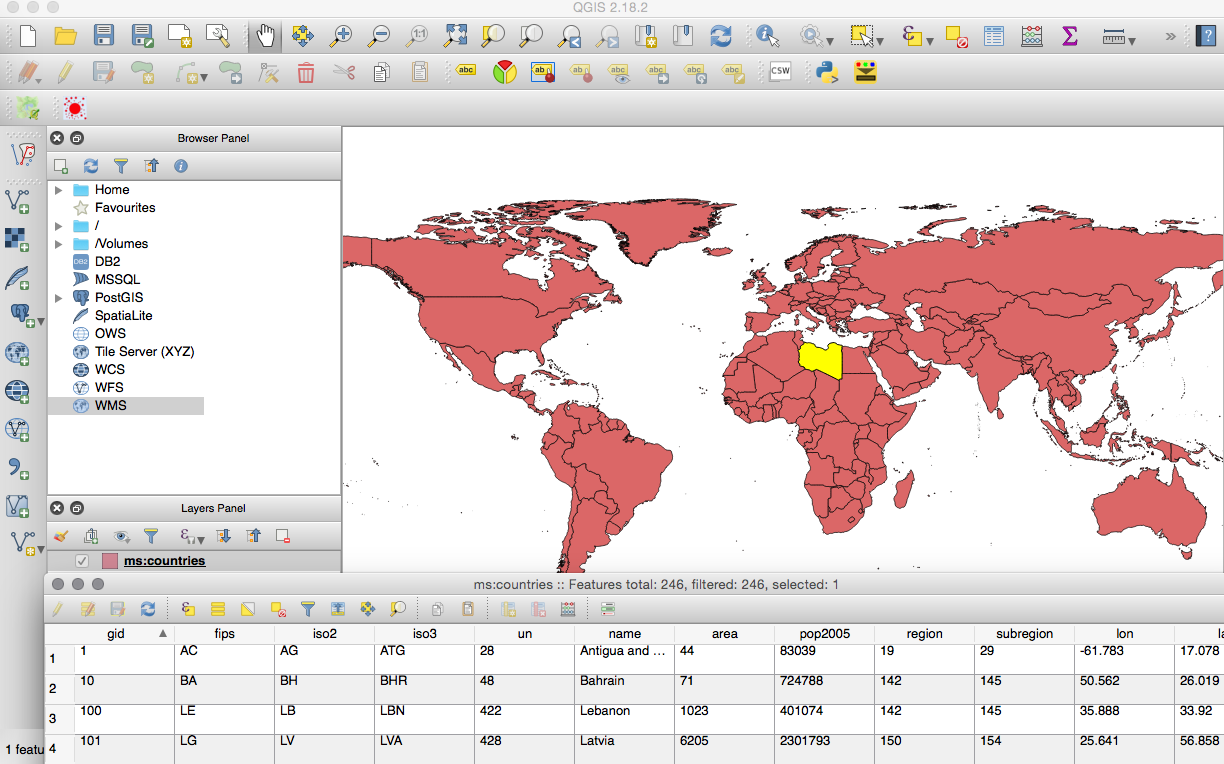

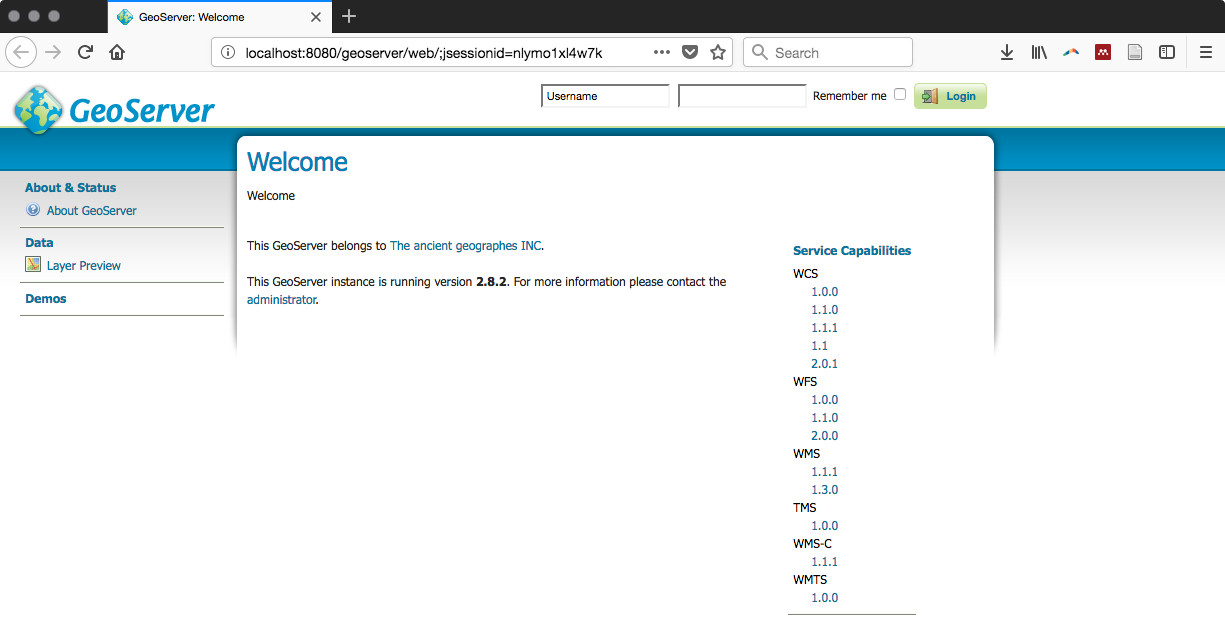

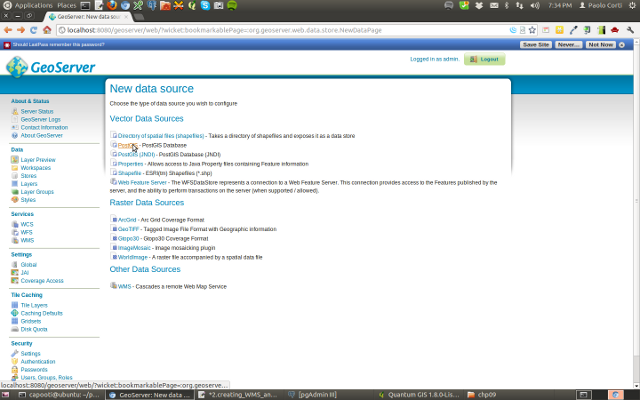

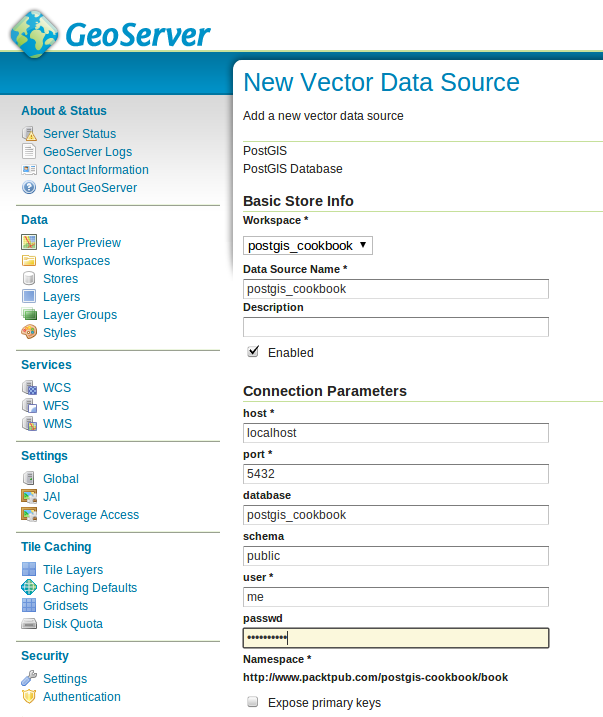

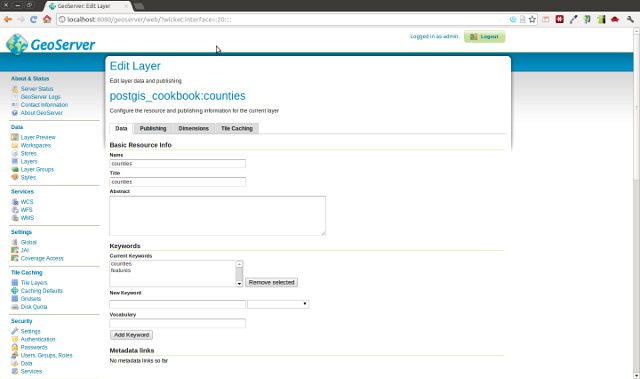

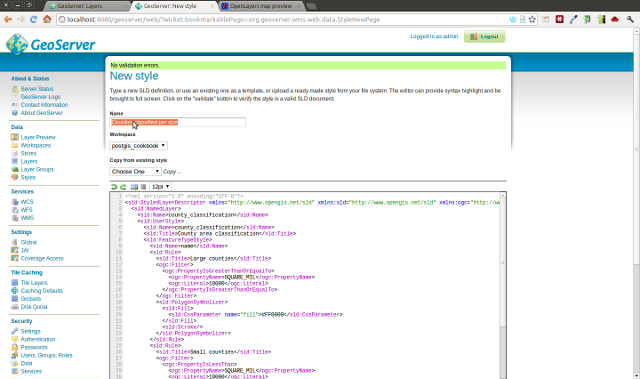

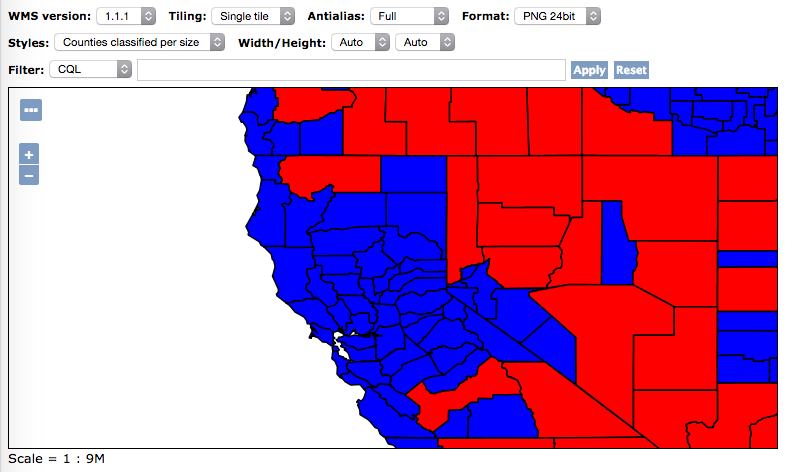

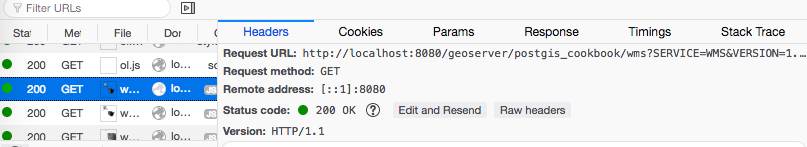

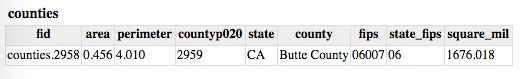

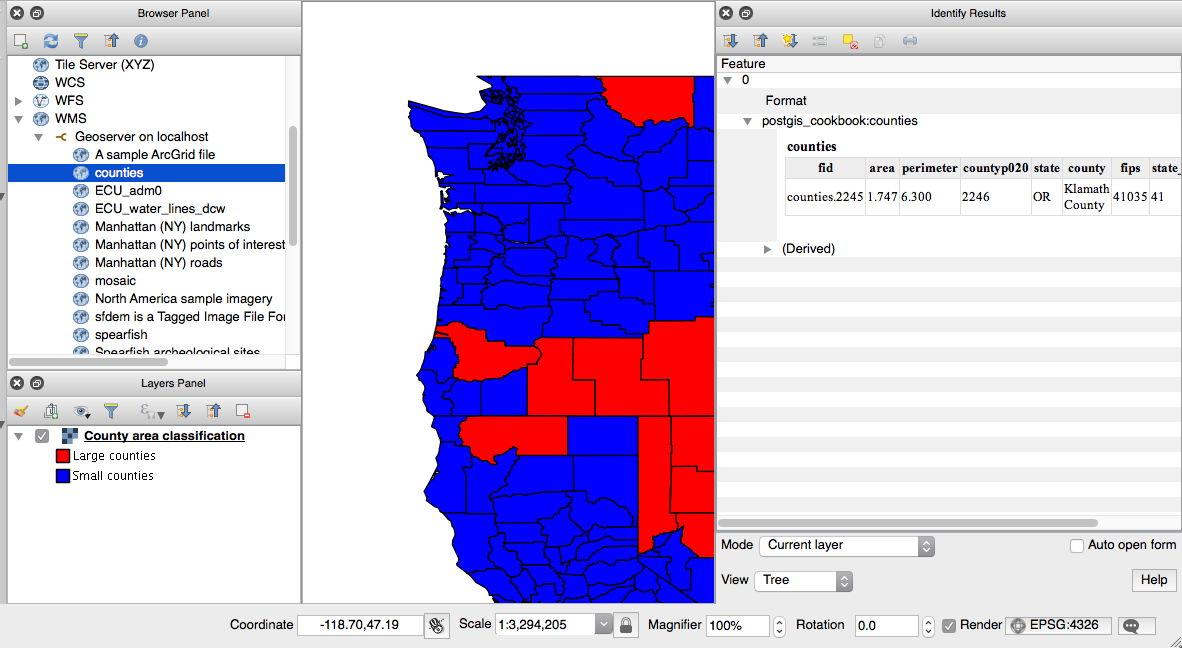

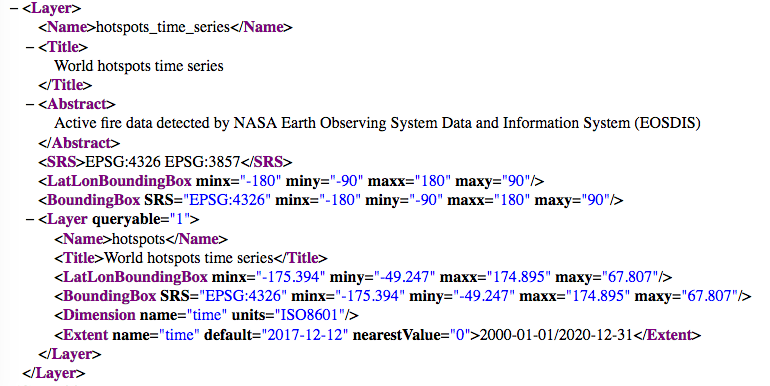

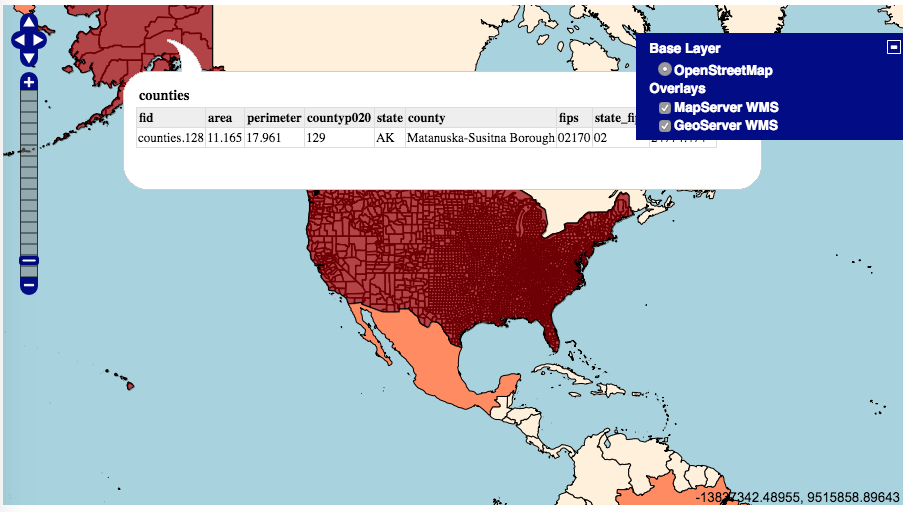

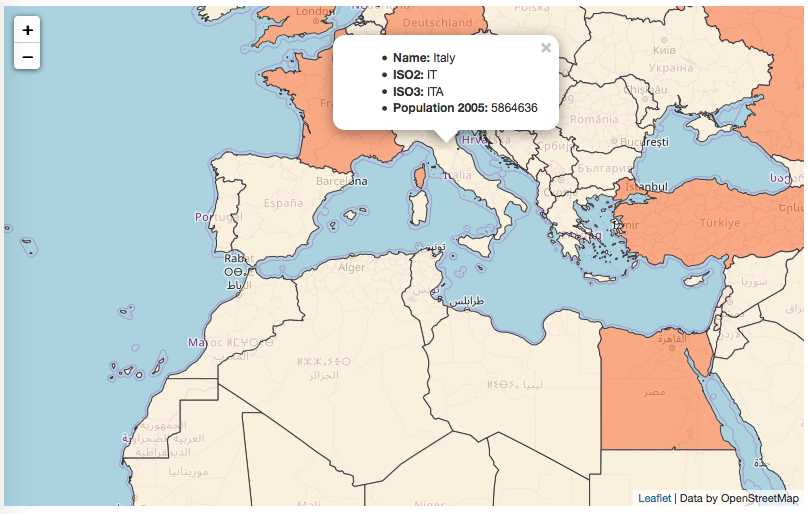

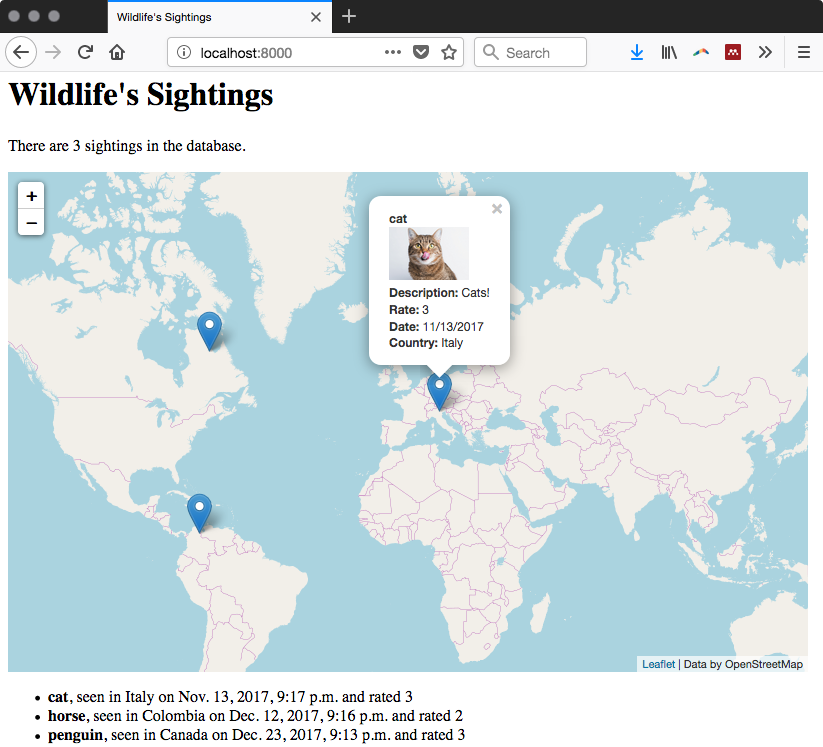

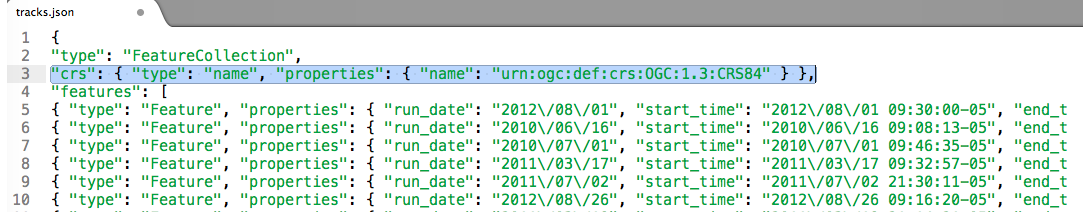

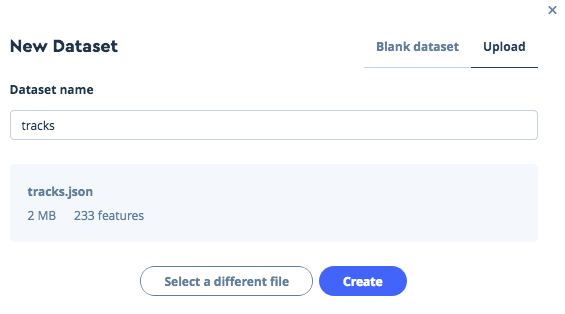

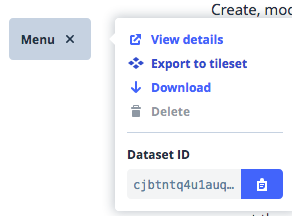

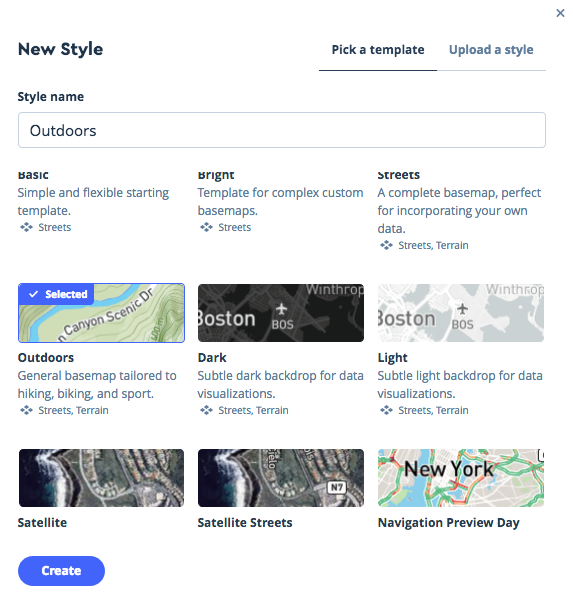

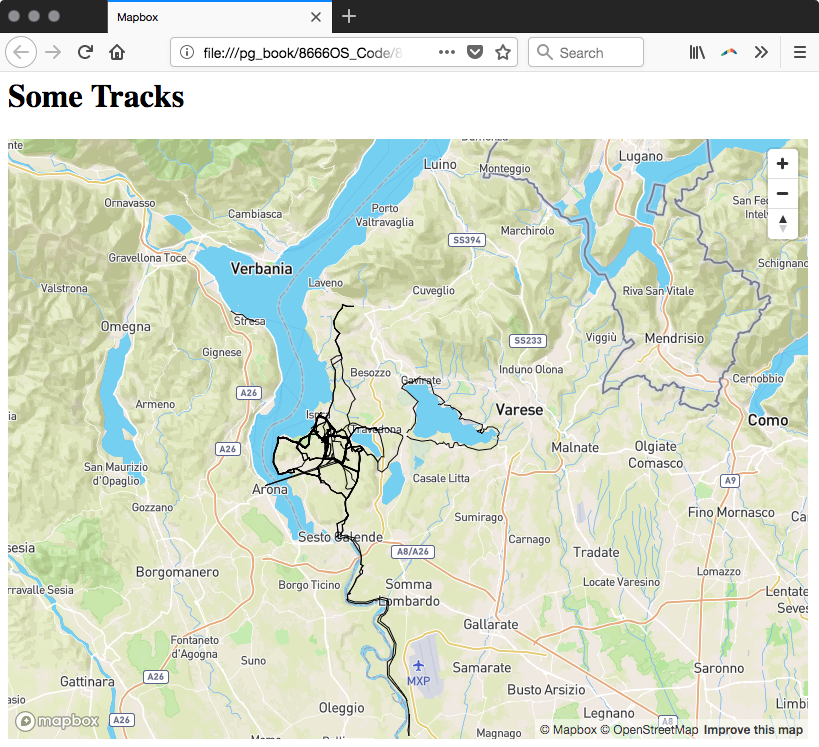

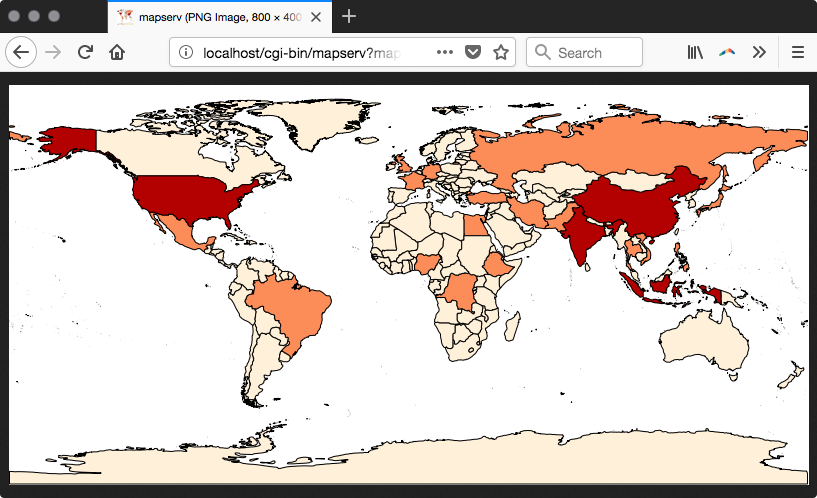

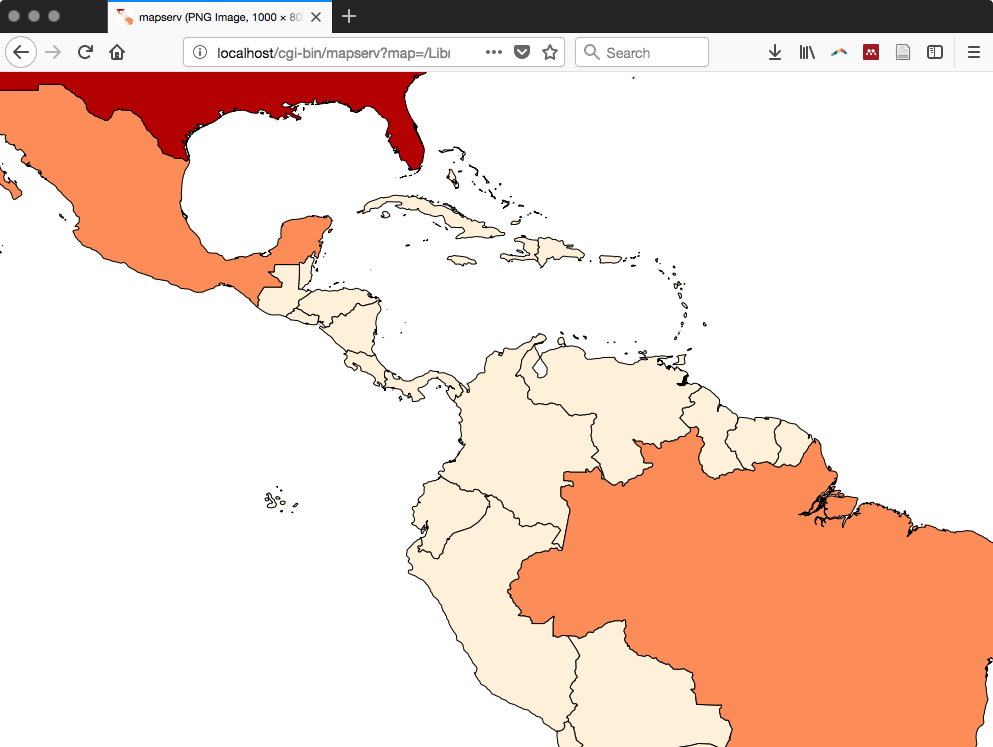

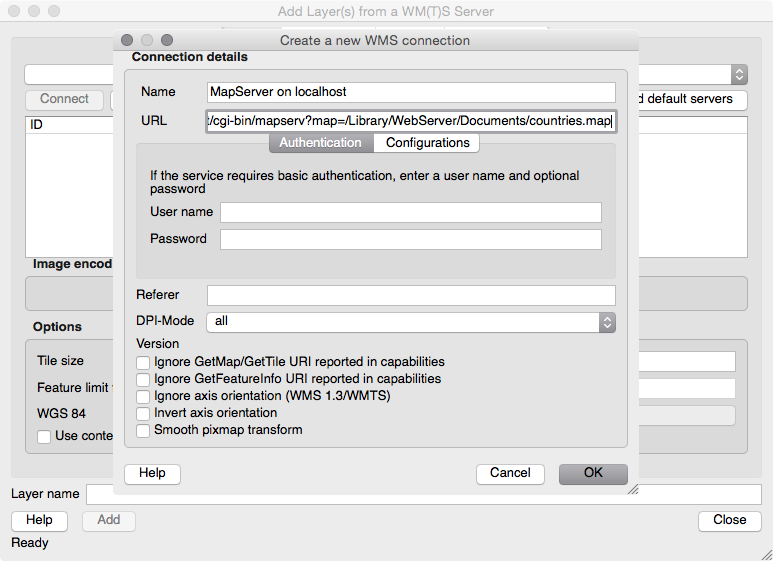

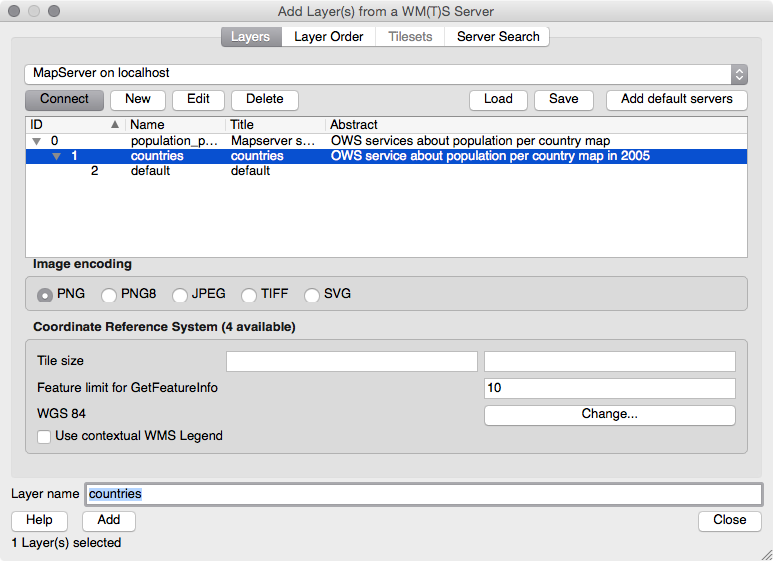

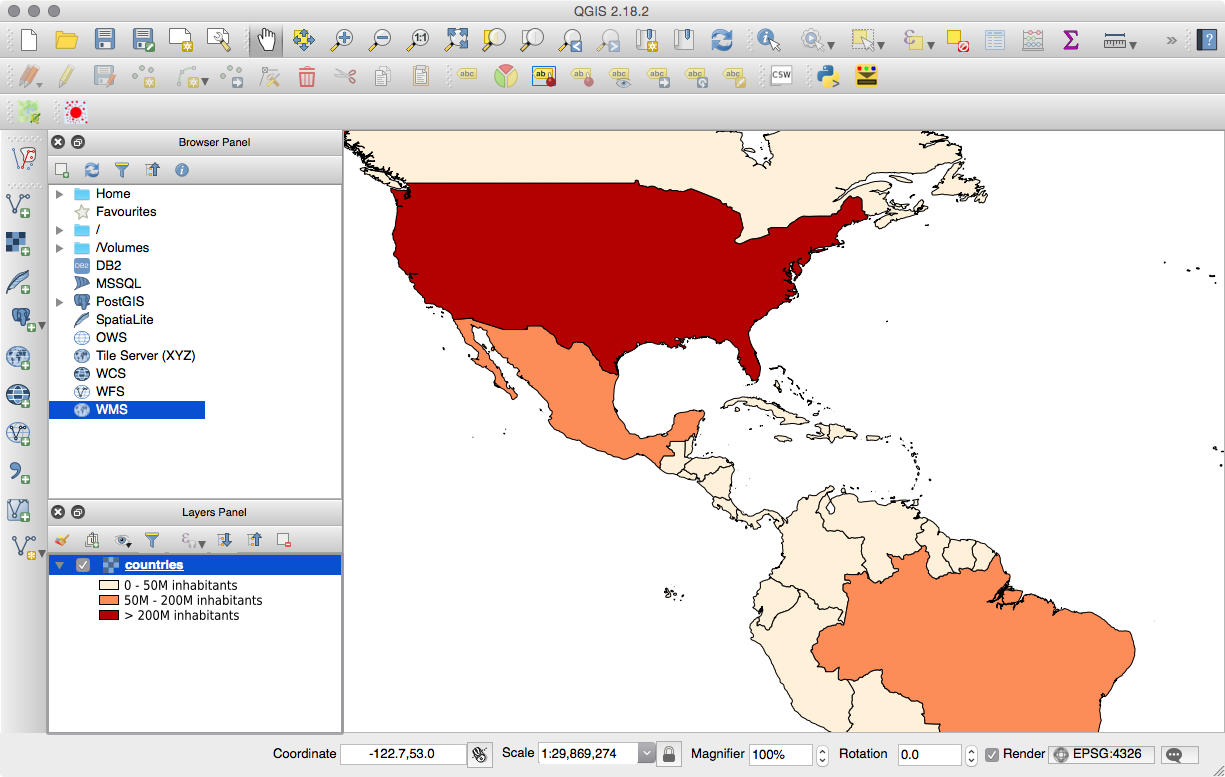

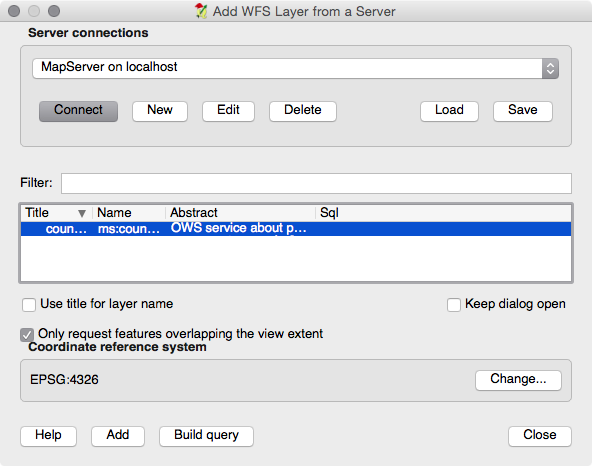

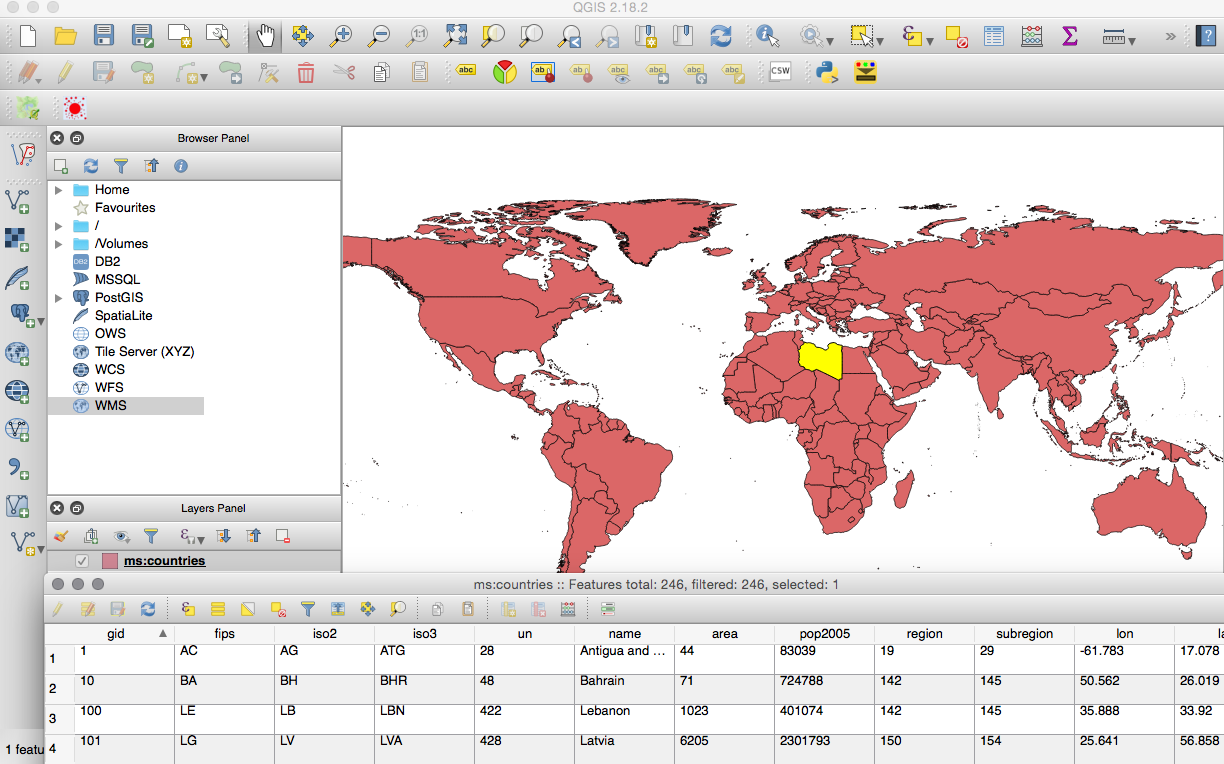

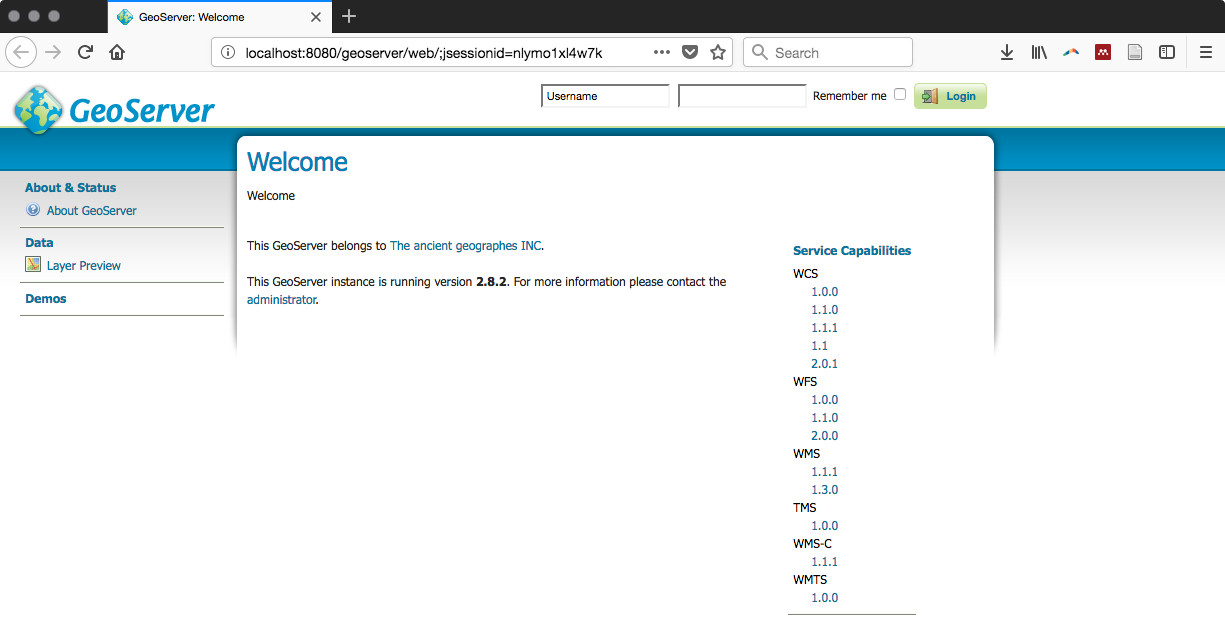

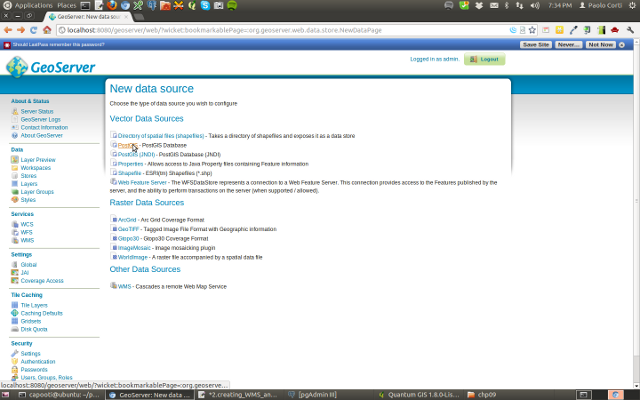

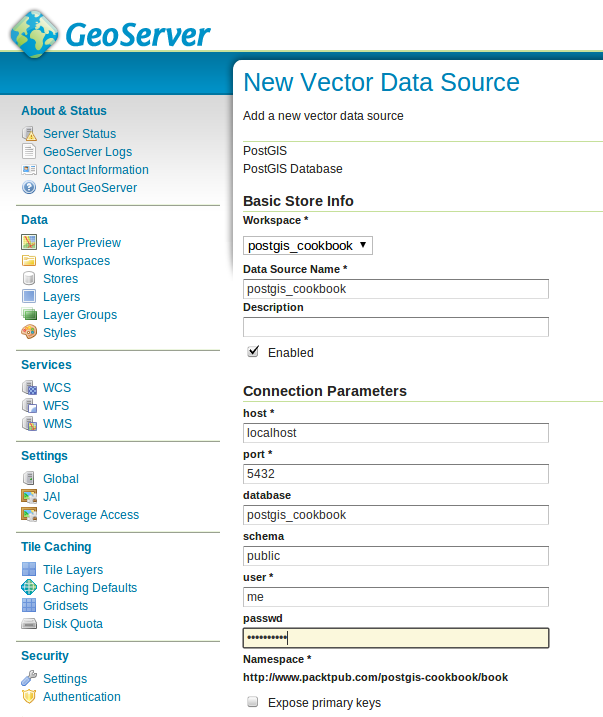

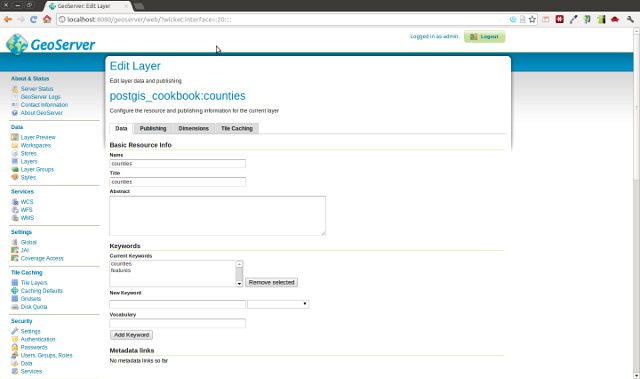

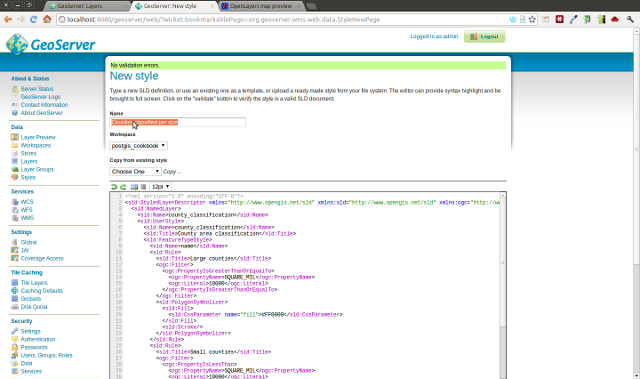

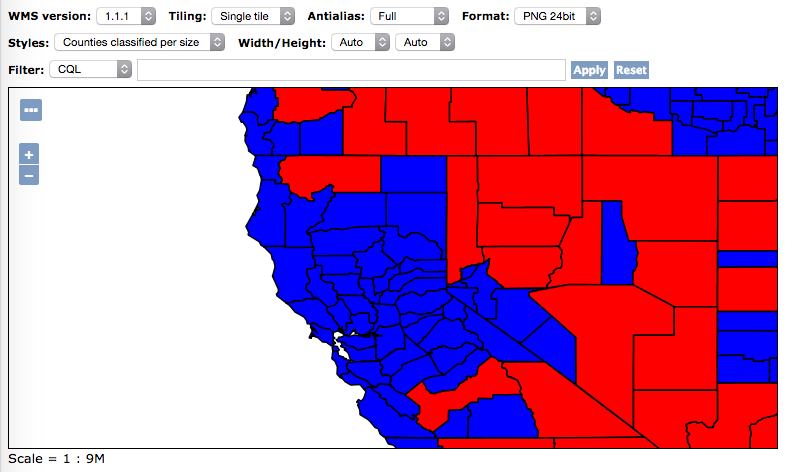

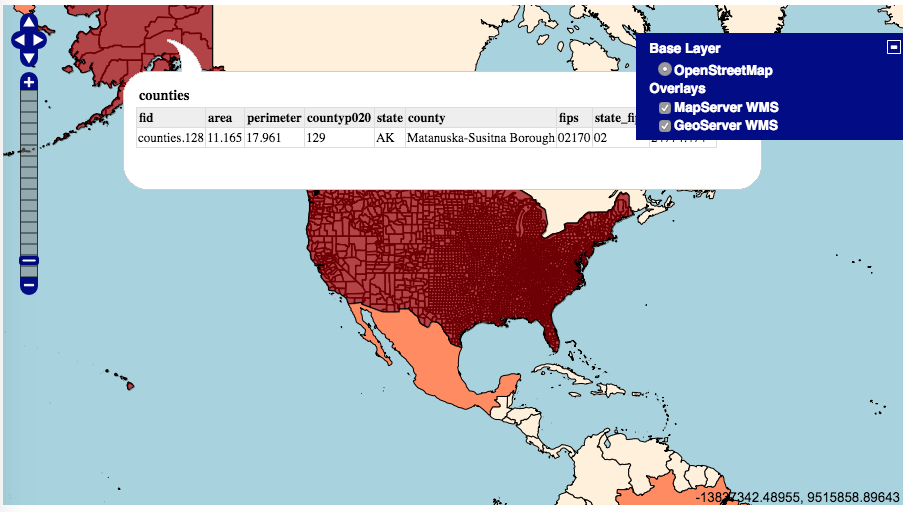

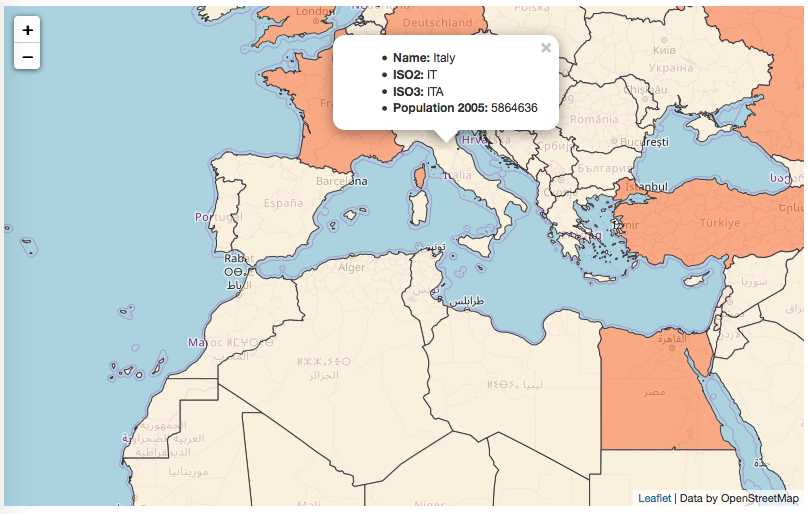

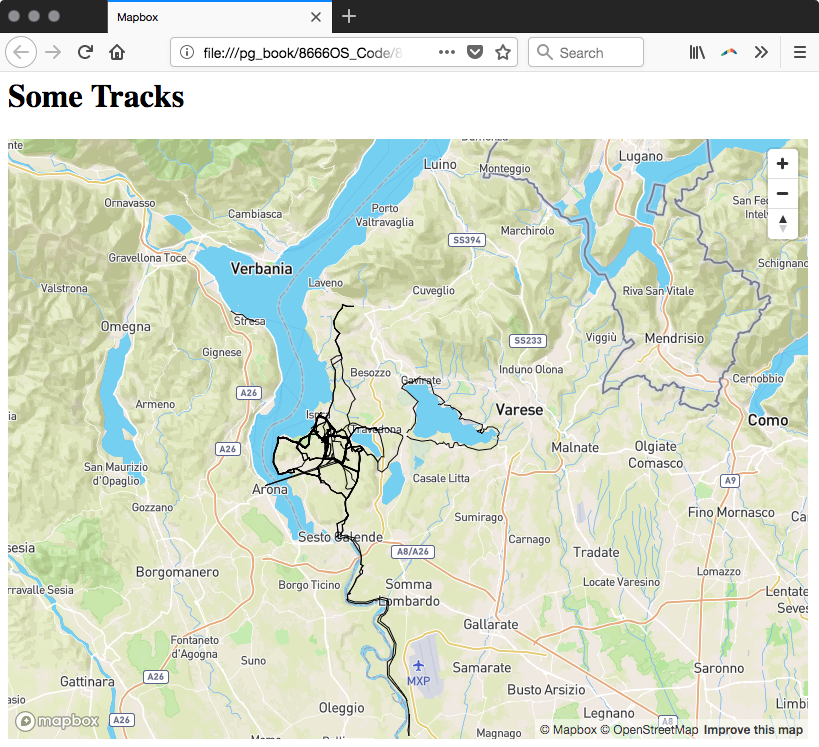

Chapter 9, PostGIS and the Web, presents the use of OGC and REST web services to deliver PostGIS data and services to the web. This chapter discusses providing OGC, WFS, and WMS services with MapServer and GeoServer, and consuming them from clients such as OpenLayers and Leaflet. It then shows how to build a web application with GeoDjango and how to include your PostGIS data in a Mapbox application.

Chapter 10, Maintenance, Optimization, and Performance Tuning, takes a step back from PostGIS and focuses on the capabilities of the PostgreSQL database server. By leveraging the tools provided by PostgreSQL, you can ensure the long-term viability of your spatial and non-spatial data, and maximize the performance of various PostGIS operations. In addition, it explores new features such as geospatial sharding and parallelism in PostgreSQL.

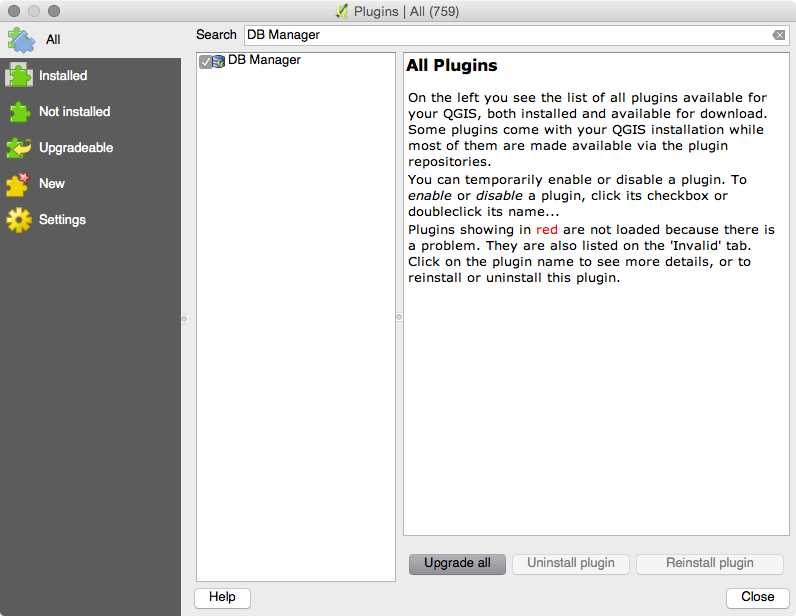

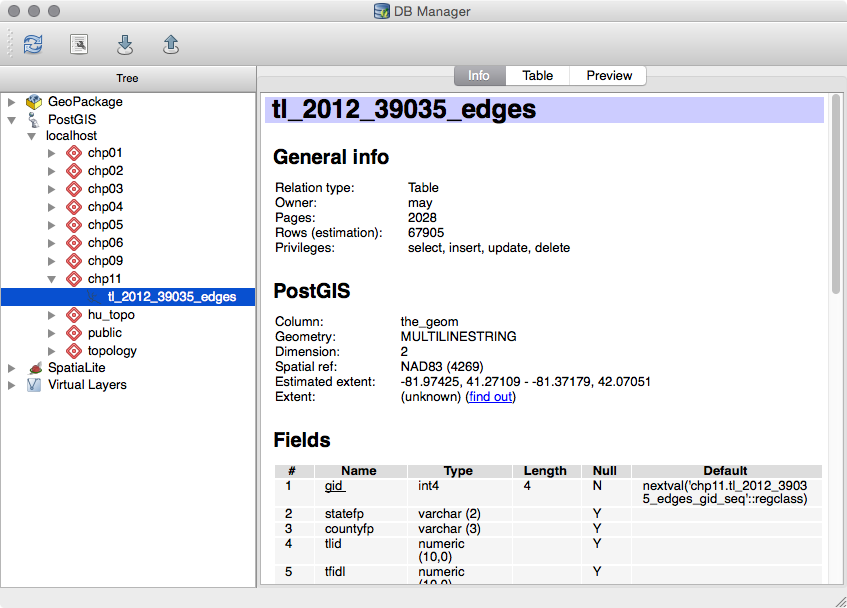

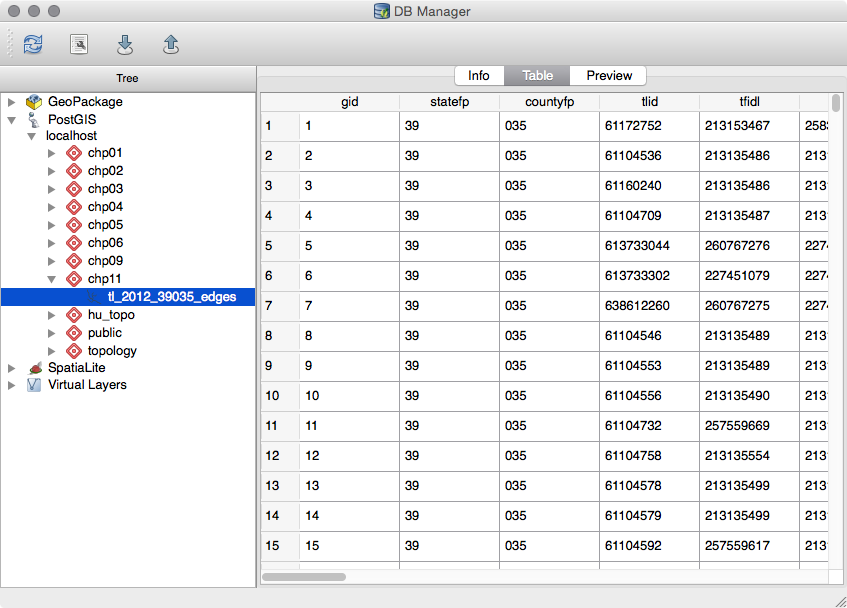

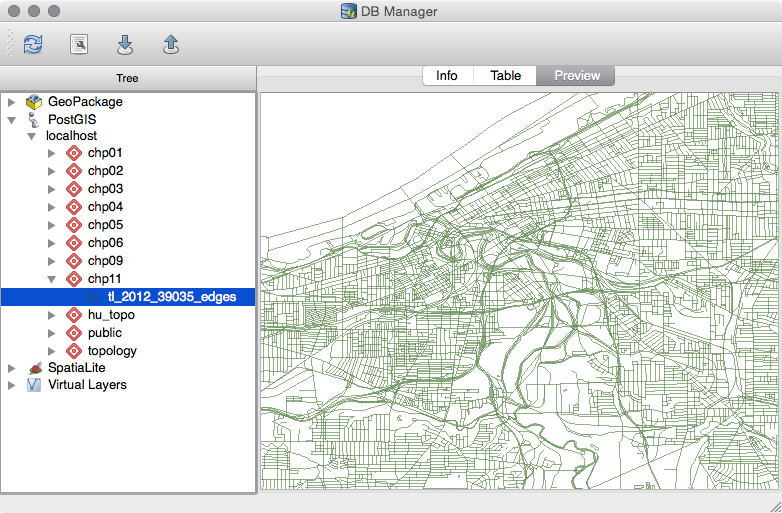

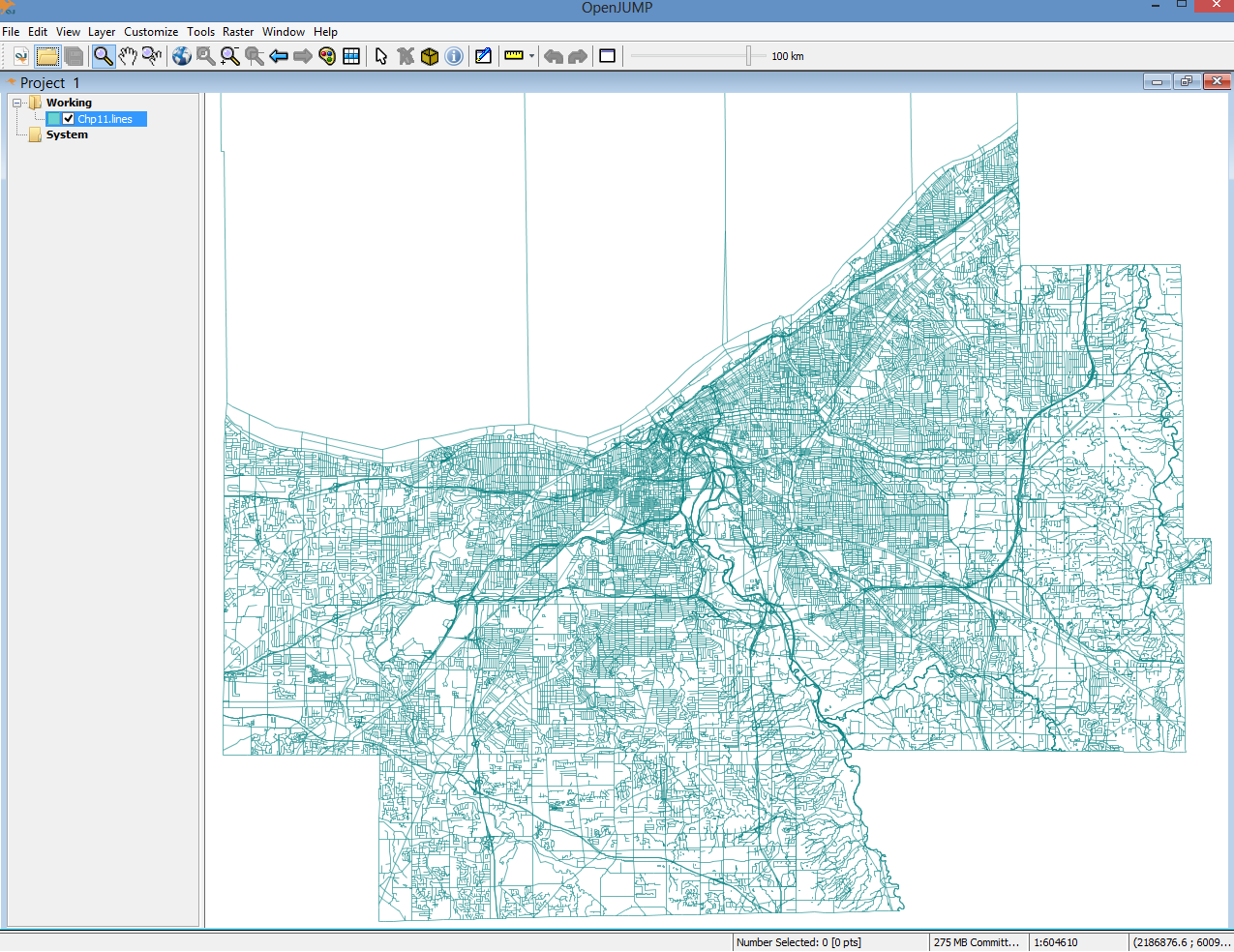

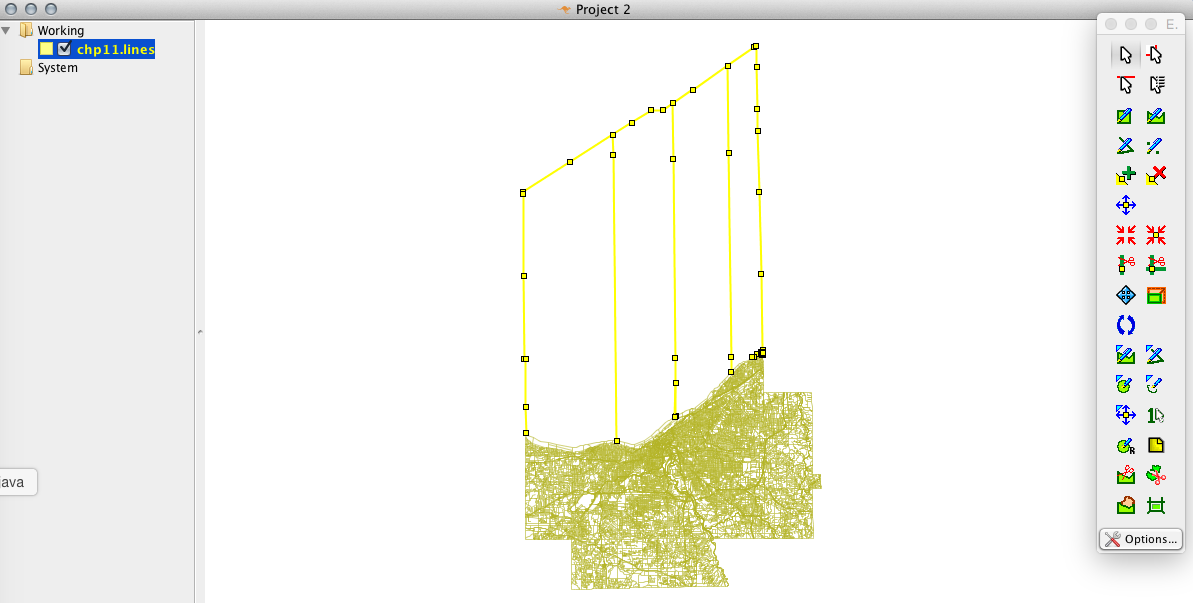

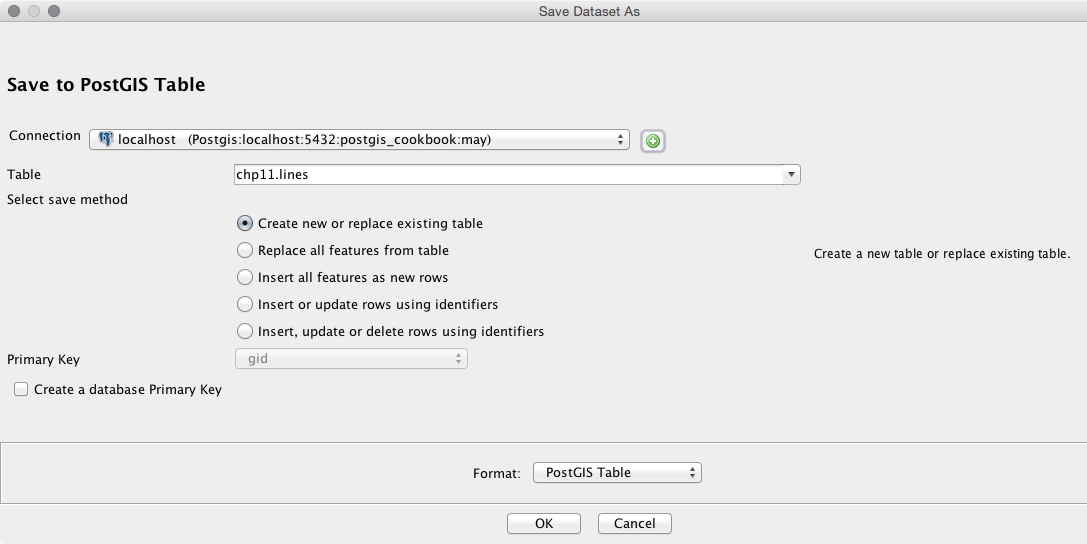

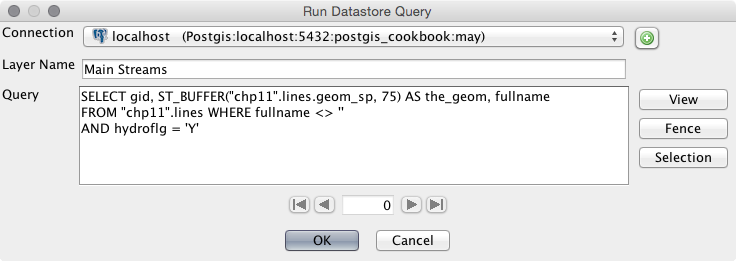

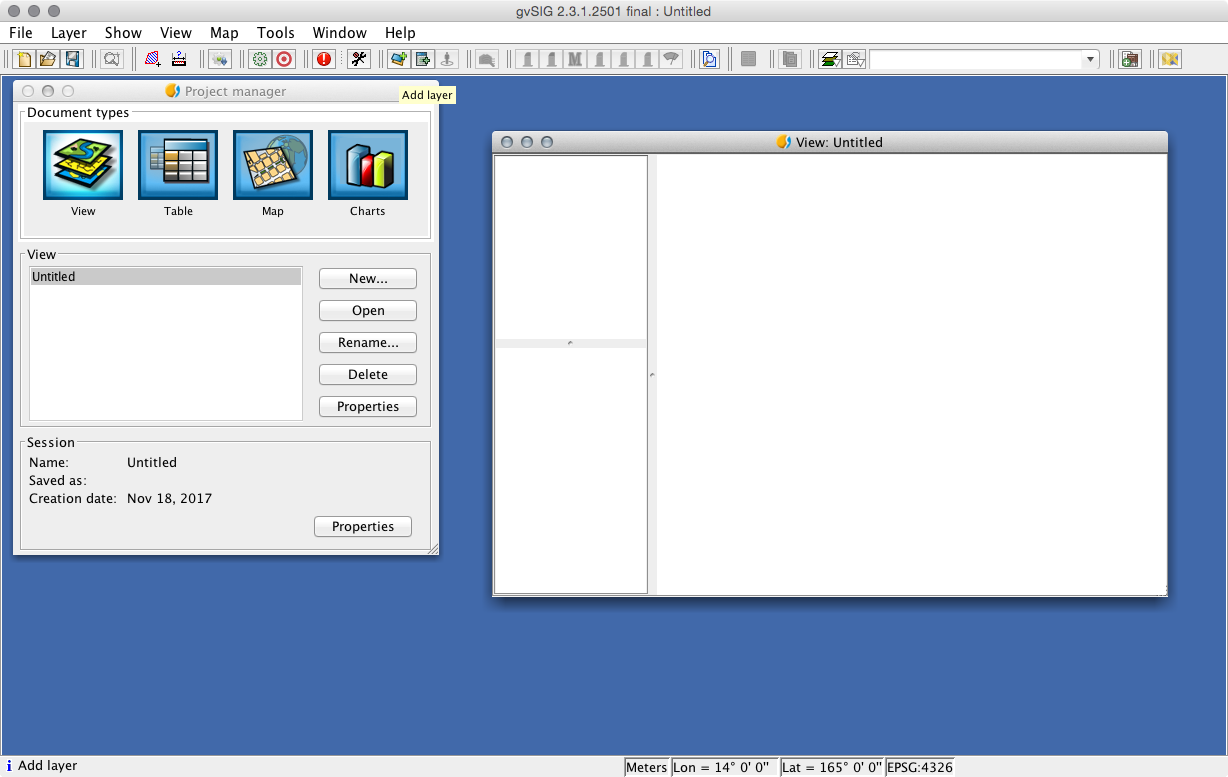

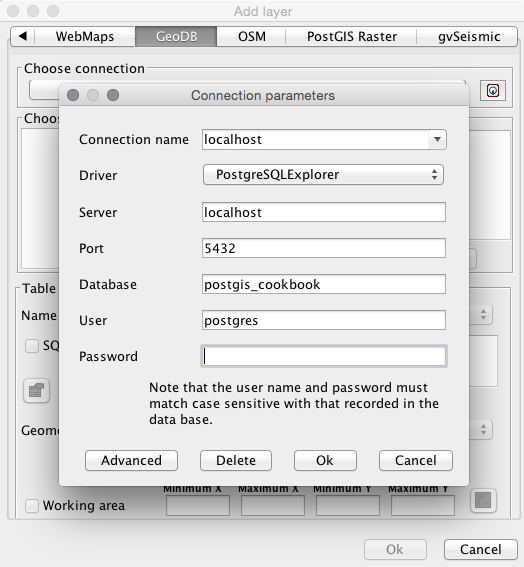

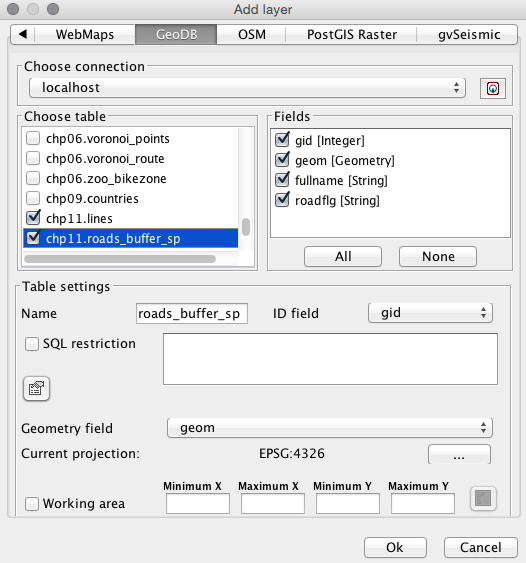

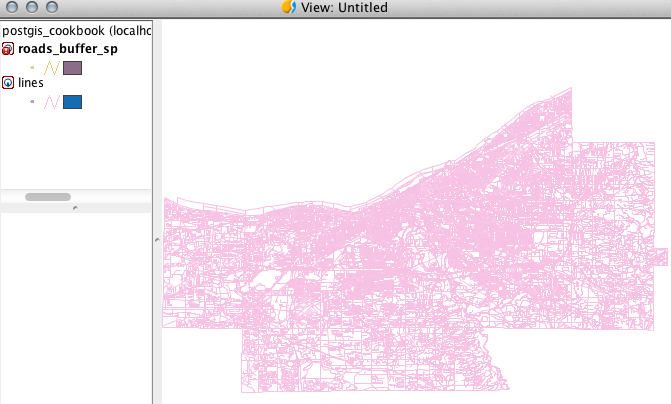

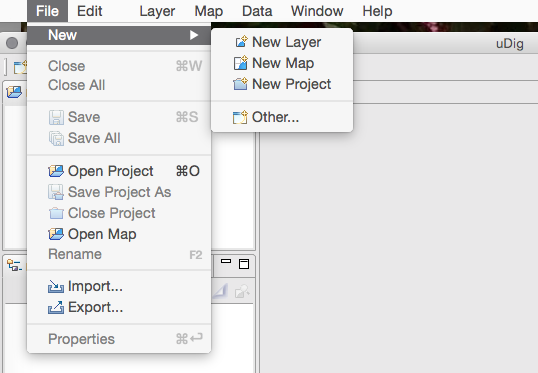

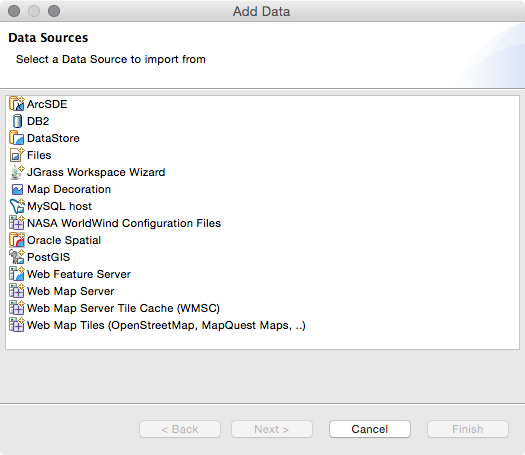

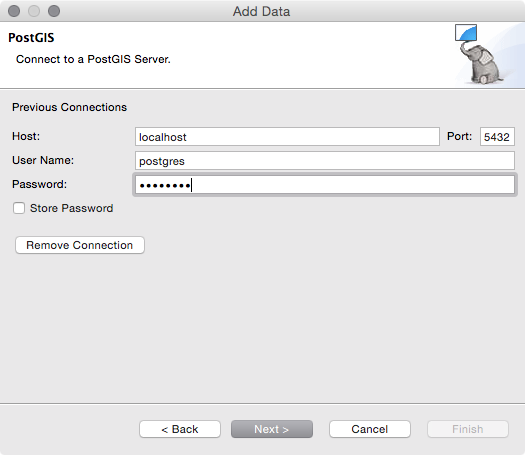

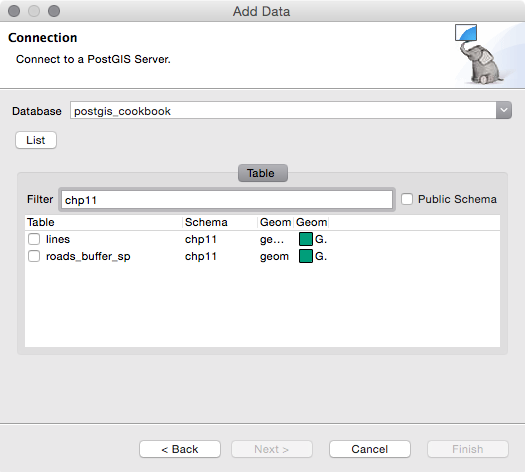

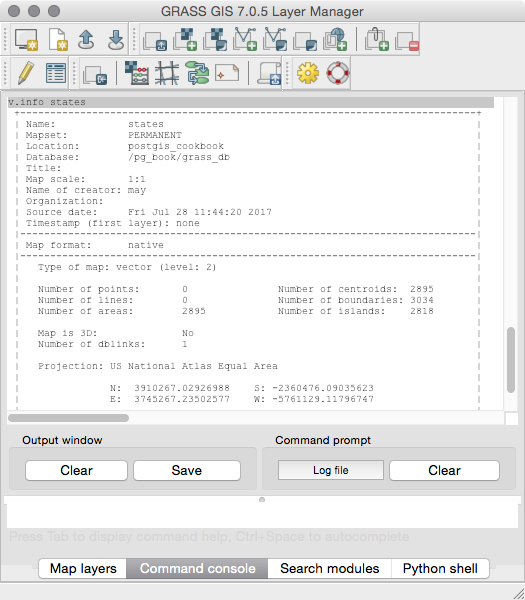

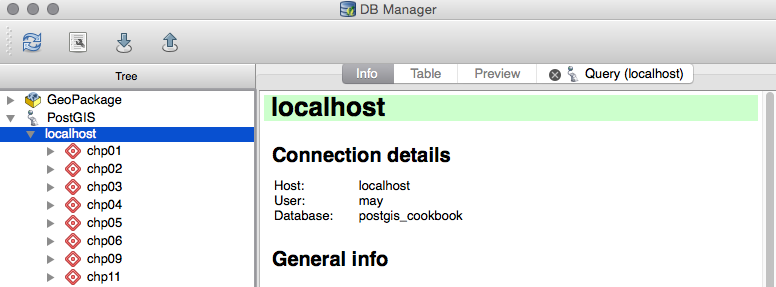

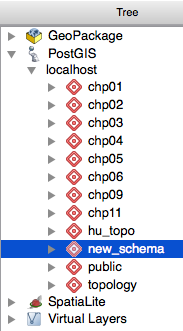

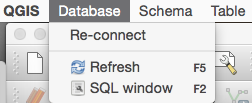

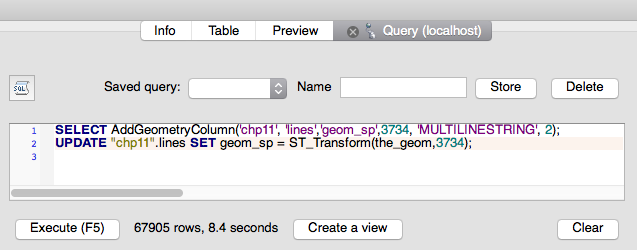

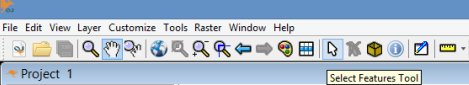

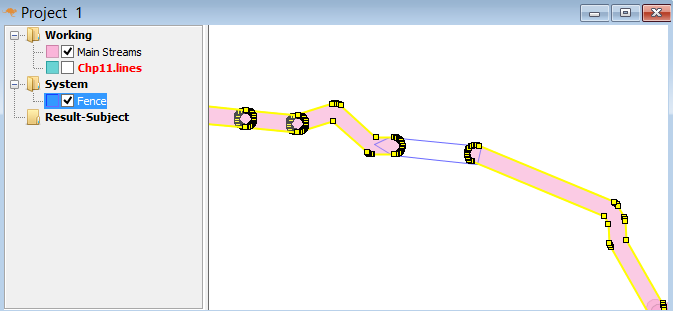

Chapter 11, Using Desktop Clients, tells you about how spatial data in PostGIS can be consumed and manipulated using various open source desktop GIS applications. Several applications are discussed so as to highlight the different approaches to interacting with spatial data and help you find the right tool for the task.

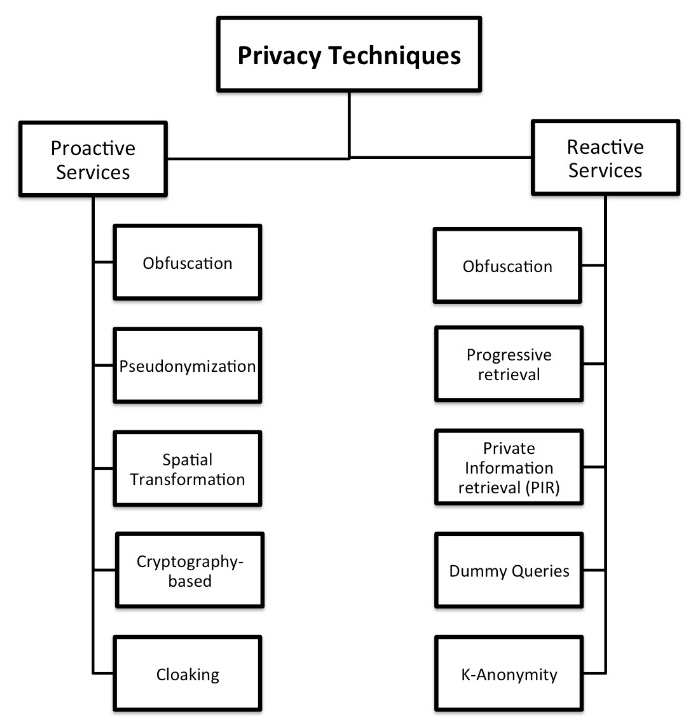

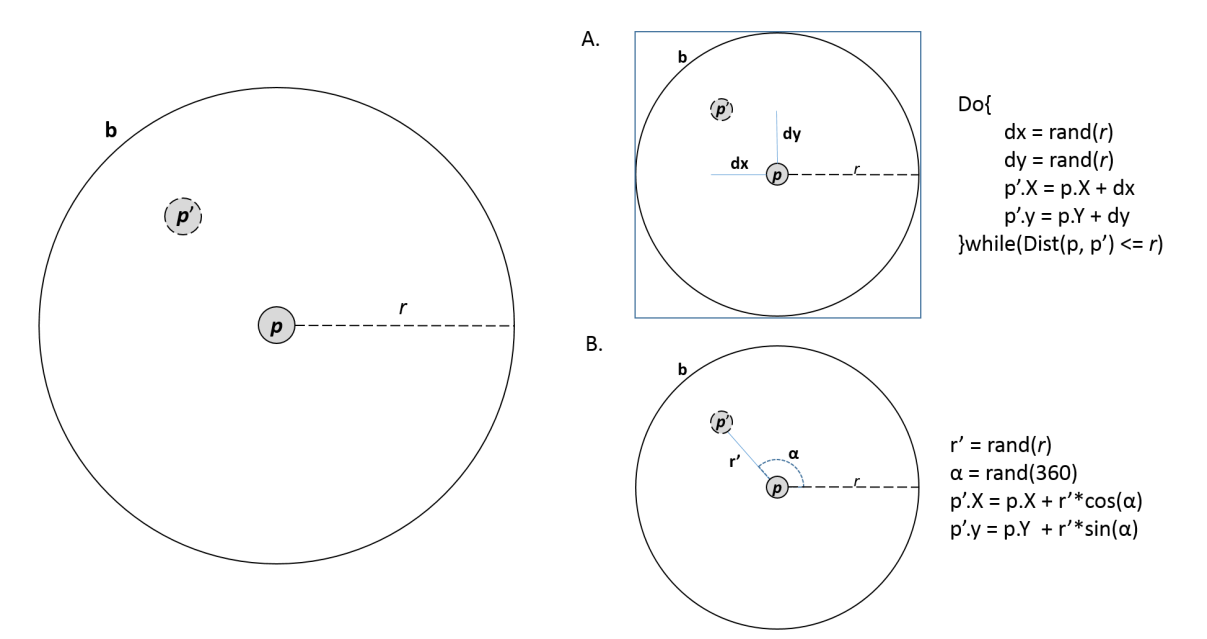

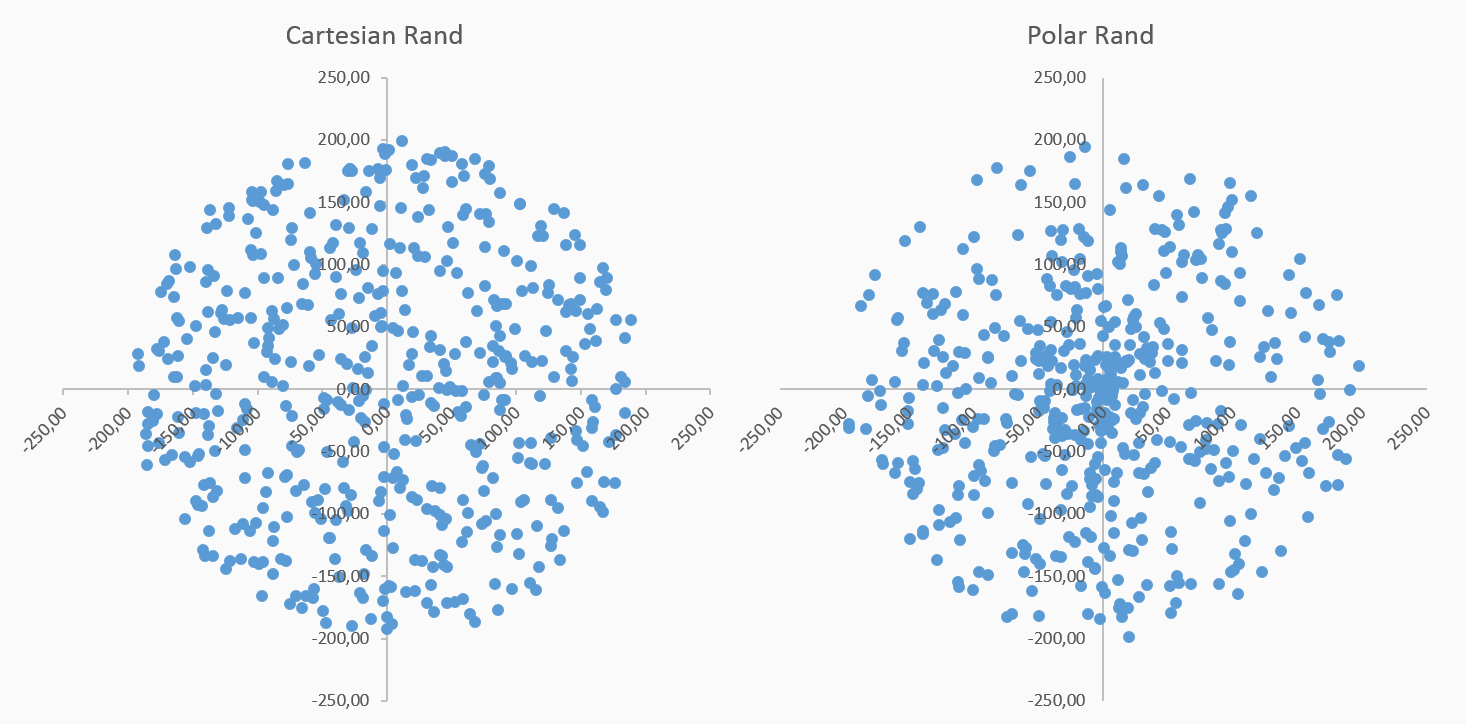

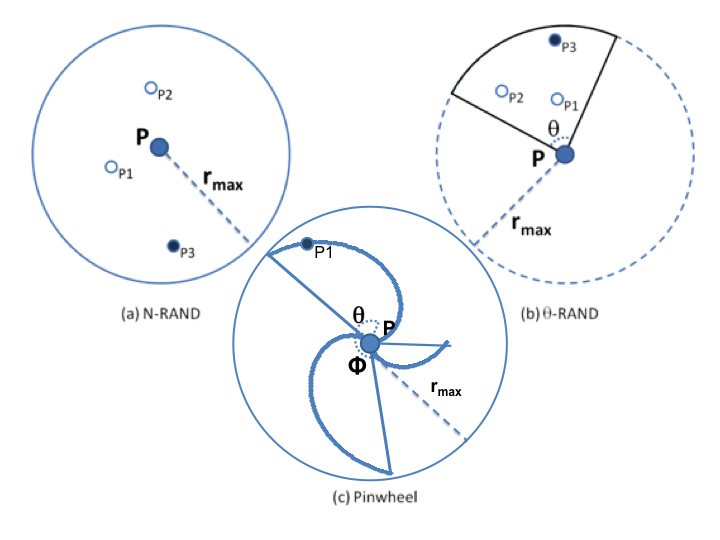

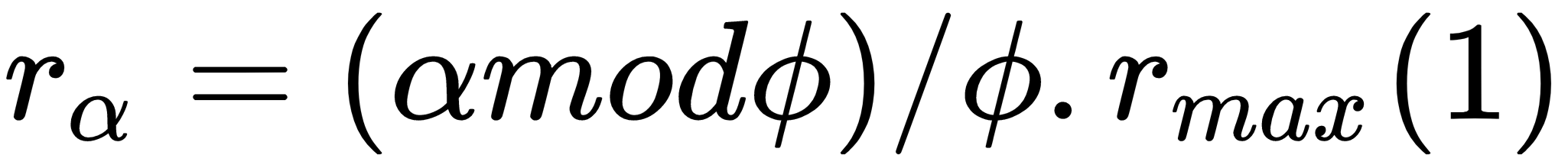

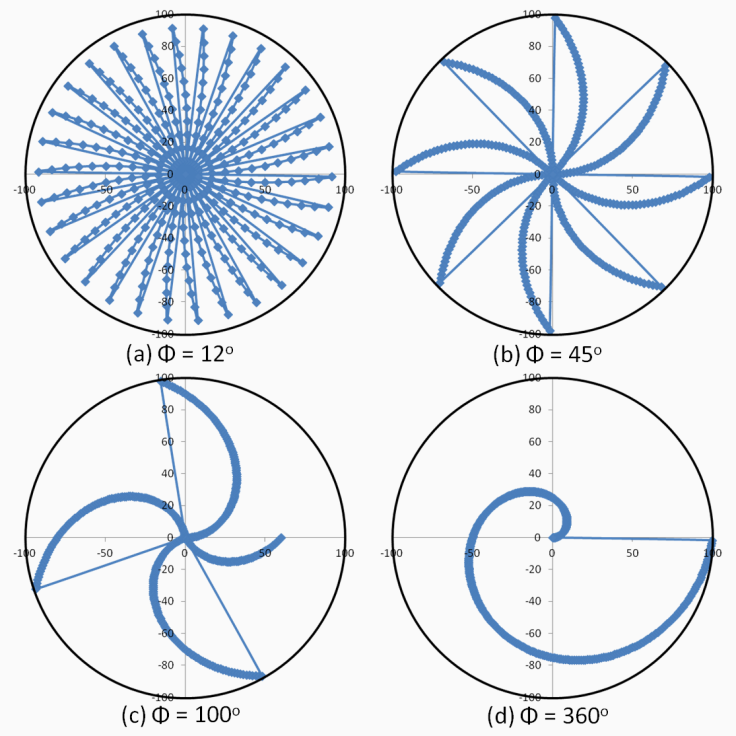

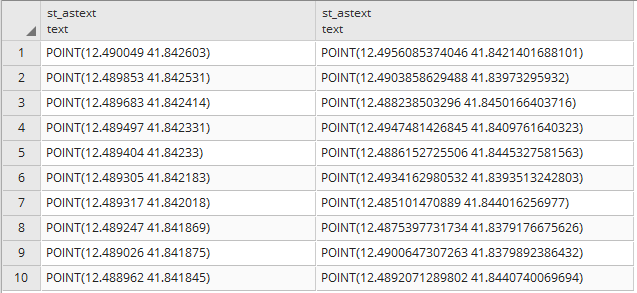

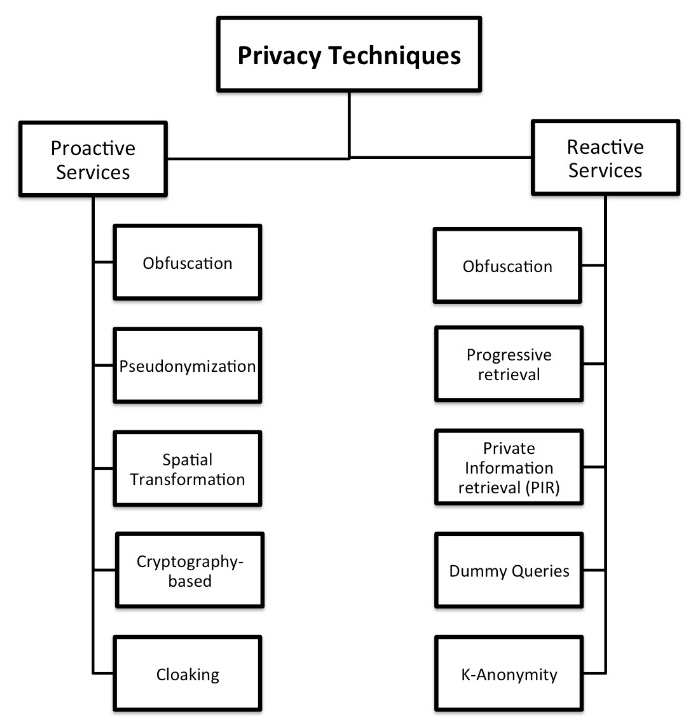

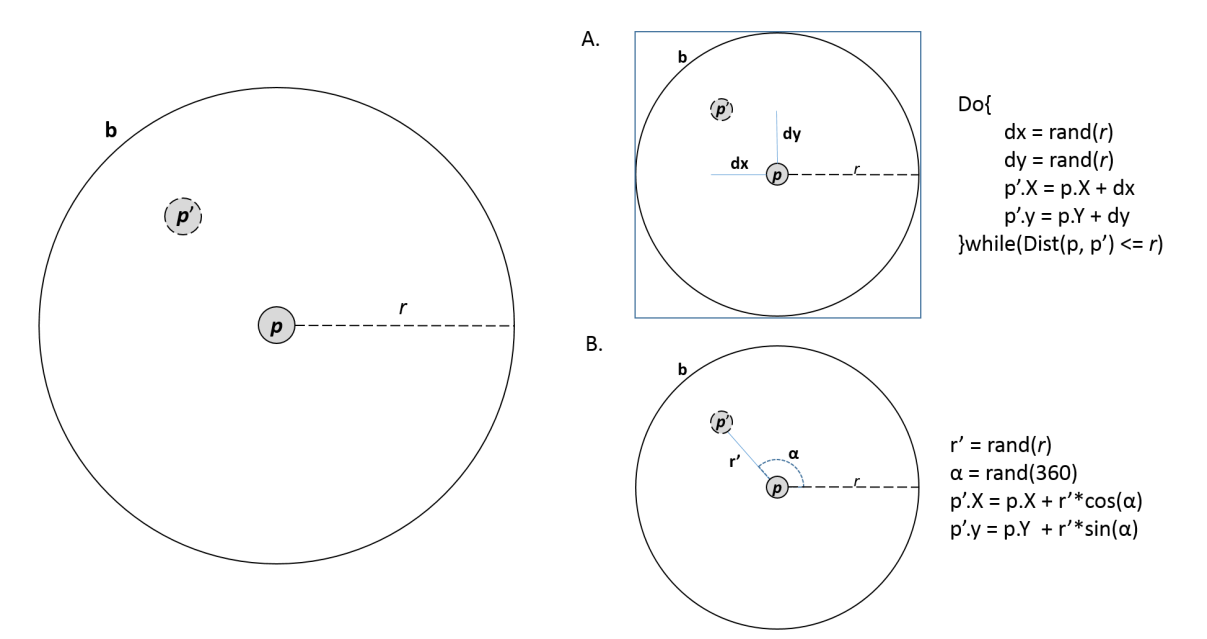

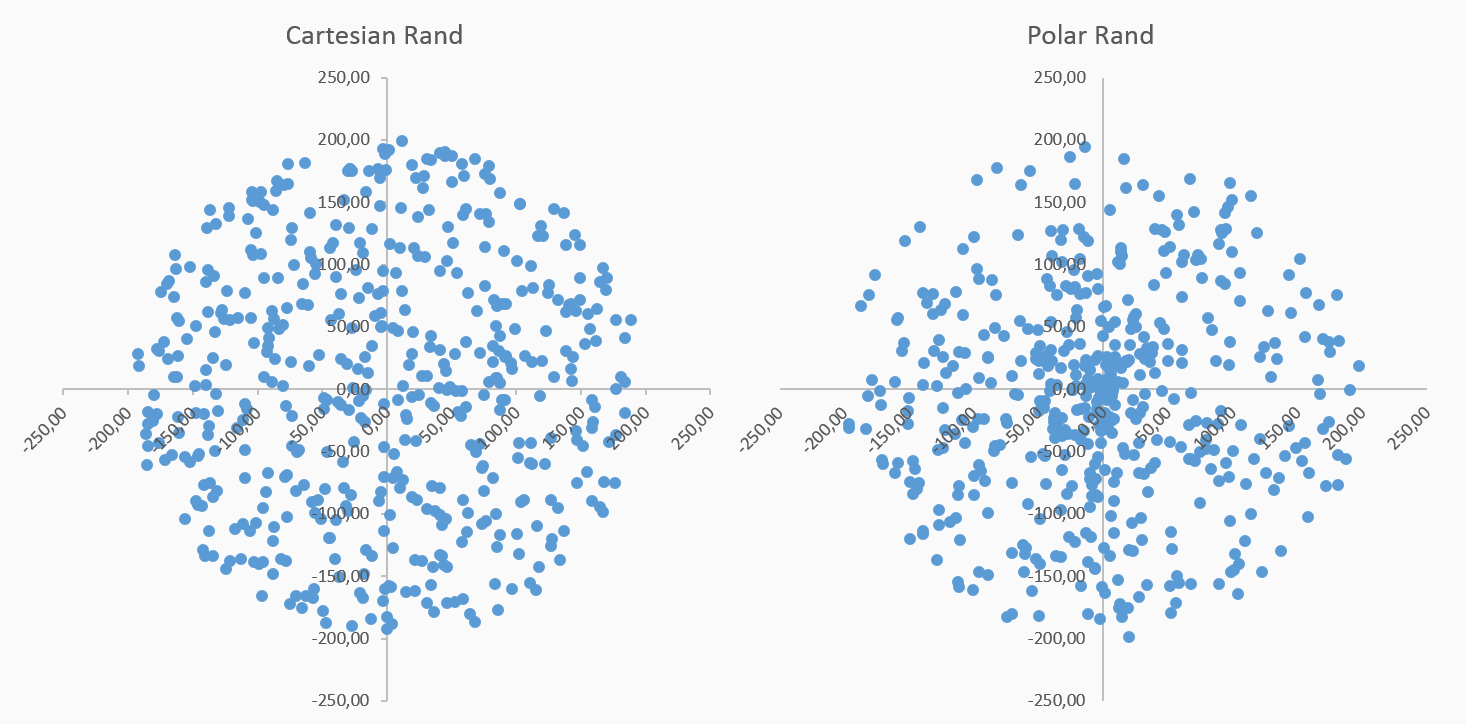

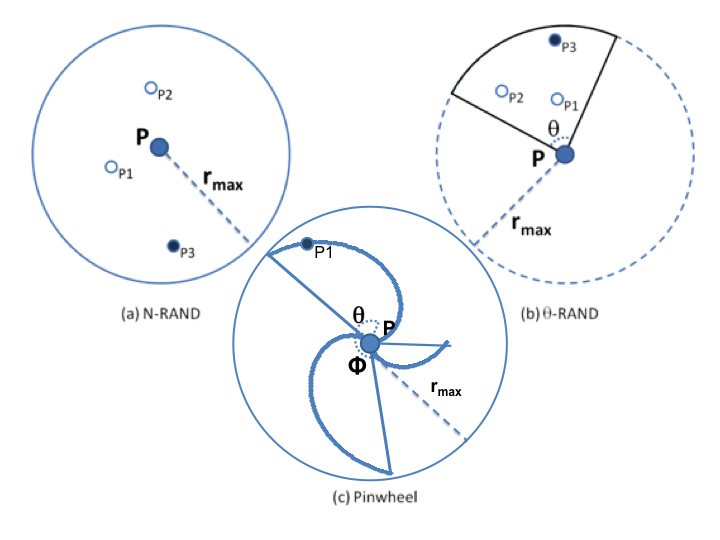

Chapter 12, Introduction to Location Privacy Protection Mechanisms, provides an introductory approximation to the concept of location privacy and presents the implementation of two different location privacy protection mechanisms that can be included in commercial applications to give a basic level of protection to the user's location data.

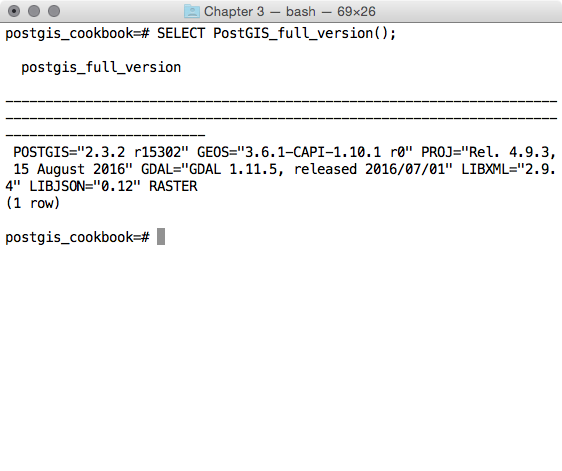

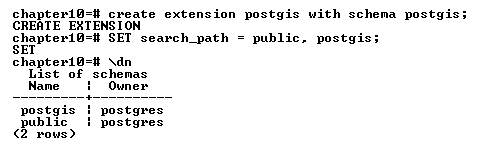

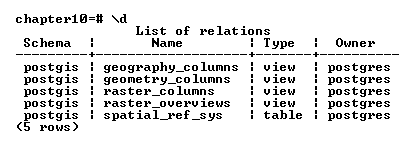

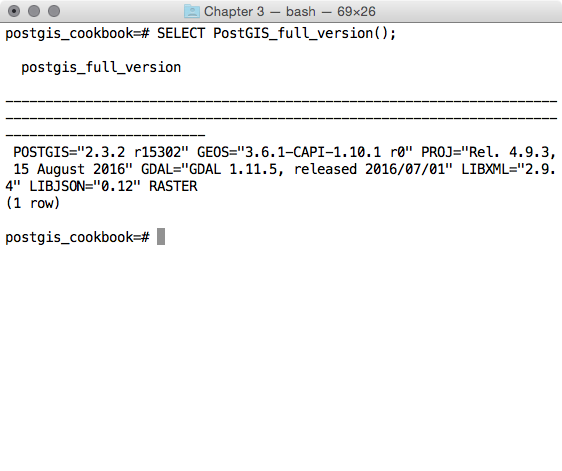

Before going further into this book, you will want to install latest versions of PostgreSQL and PostGIS (9.6 or 103 and 2.3 or 2.41, respectively). You may also want to install pgAdmin (1.18) if you prefer a graphical SQL tool. For most computing environments (Windows, Linux, macOS X), installers and packages include all required dependencies of PostGIS. The minimum required dependencies for PostGIS are PROJ.4, GEOS, libjson and GDAL.

A basic understanding of the SQL language is required to understand and adapt the code found in this book's recipes.

You can download the example code files for this book from your account at www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files emailed directly to you.

You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

The code bundle for the book is also hosted on GitHub at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/PostGIS-Cookbook-Second-Edition. In case there's an update to the code, it will be updated on the existing GitHub repository.

We also have other code bundles from our rich catalog of books and videos available at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/. Check them out!

We also provide a PDF file that has color images of the screenshots/diagrams used in this book. You can download it here: https://www.packtpub.com/sites/default/files/downloads/PostGISCookbookSecondEdition_ColorImages.pdf.

There are a number of text conventions used throughout this book.

CodeInText: Indicates code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles. Here is an example: "We will import the firenews.csv file that stores a series of web news collected from various RSS feeds."

A block of code is set as follows:

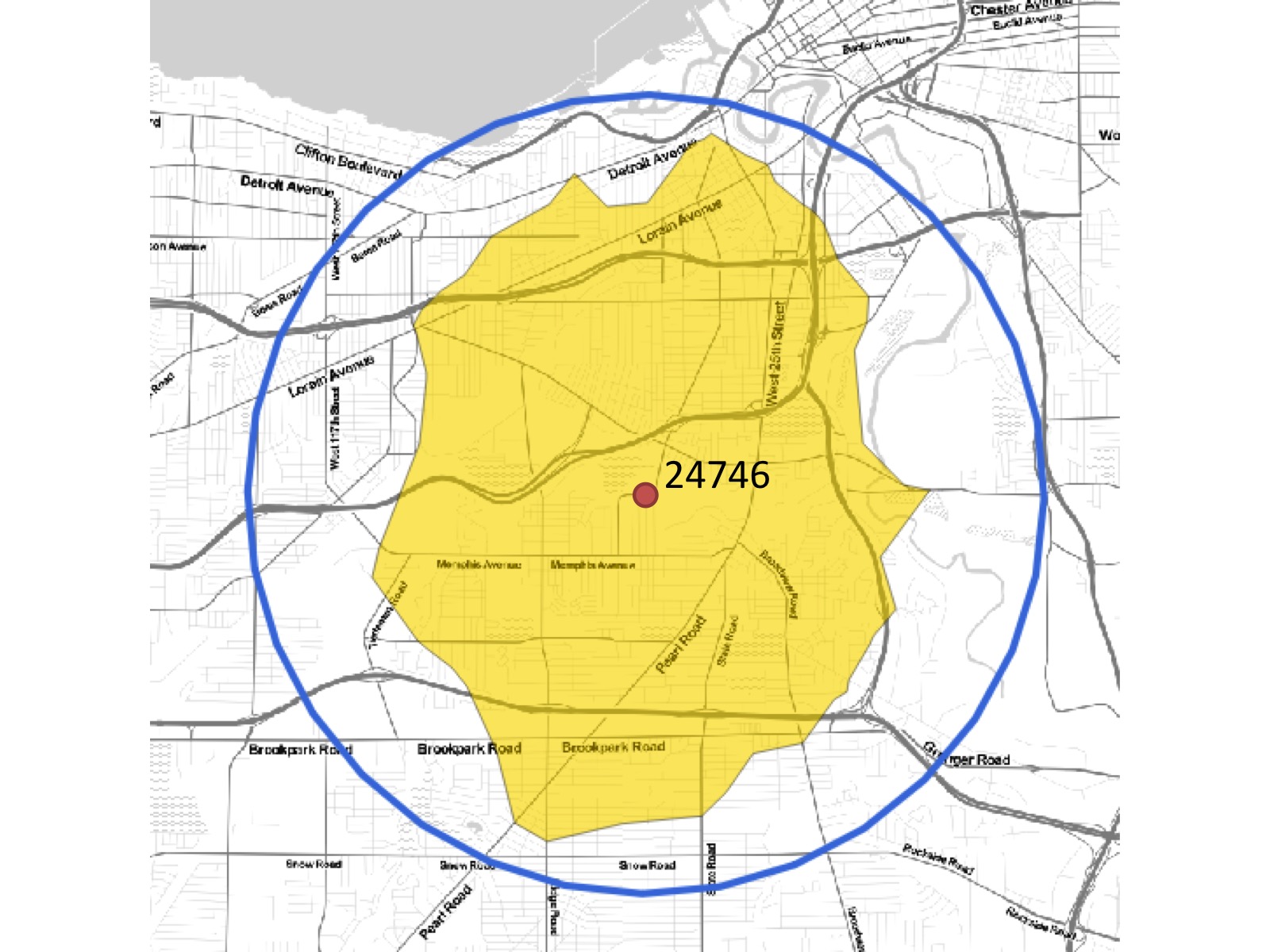

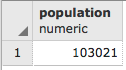

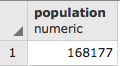

SELECT ROUND(SUM(chp02.proportional_sum(ST_Transform(a.geom,3734), b.geom, b.pop))) AS population

FROM nc_walkzone AS a, census_viewpolygon as b

WHERE ST_Intersects(ST_Transform(a.geom, 3734), b.geom)

GROUP BY a.id;

When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

SELECT ROUND(SUM(chp02.proportional_sum(ST_Transform(a.geom,3734), b.geom, b.pop))) AS population

FROM nc_walkzone AS a, census_viewpolygon as b

WHERE ST_Intersects(ST_Transform(a.geom, 3734), b.geom)

GROUP BY a.id;

Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

> raster2pgsql -s 4322 -t 100x100 -F -I -C -Y C:\postgis_cookbook\data\chap5\PRISM\us_tmin_2012.*.asc chap5.prism | psql -d postgis_cookbook

Bold: Indicates a new term, an important word, or words that you see onscreen. For example, words in menus or dialog boxes appear in the text like this. Here is an example: "Clicking the Next button moves you to the next screen."

In this book, you will find several headings that appear frequently (Getting ready, How to do it..., How it works..., There's more..., and See also).

To give clear instructions on how to complete a recipe, use these sections as follows:

This section tells you what to expect in the recipe and describes how to set up any software or any preliminary settings required for the recipe.

This section contains the steps required to follow the recipe.

This section usually consists of a detailed explanation of what happened in the previous section.

This section consists of additional information about the recipe in order to make you more knowledgeable about the recipe.

This section provides helpful links to other useful information for the recipe.

Feedback from our readers is always welcome.

General feedback: Email feedback@packtpub.com and mention the book title in the subject of your message. If you have questions about any aspect of this book, please email us at questions@packtpub.com.

Errata: Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you have found a mistake in this book, we would be grateful if you would report this to us. Please visit www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details.

Piracy: If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the internet, we would be grateful if you would provide us with the location address or website name. Please contact us at copyright@packtpub.com with a link to the material.

If you are interested in becoming an author: If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, please visit authors.packtpub.com.

Please leave a review. Once you have read and used this book, why not leave a review on the site that you purchased it from? Potential readers can then see and use your unbiased opinion to make purchase decisions, we at Packt can understand what you think about our products, and our authors can see your feedback on their book. Thank you!

For more information about Packt, please visit packtpub.com.

In this chapter, we will cover:

PostGIS is an open source extension for the PostgreSQL database that allows support for geographic objects; throughout this book you will find recipes that will guide you step by step to explore the different functionalities it offers.

The purpose of the book is to become a useful tool for understanding the capabilities of PostGIS and how to apply them in no time. Each recipe presents a preparation stage, in order to organize your workspace with everything you may need, then the set of steps that you need to perform in order to achieve the main goal of the task, that includes all the external commands and SQL sentences you will need (which have been tested in Linux, Mac and Windows environments), and finally a small summary of the recipe. This book will go over a large set of common tasks in geographical information systems and location-based services, which makes it a must-have book in your technical library.

In this first chapter, we will show you a set of recipes covering different tools and methodologies to import and export geographic data from the PostGIS spatial database, given that pretty much every common action to perform in a GIS starts with inserting or exporting geospatial data.

There are a couple of alternative approaches to importing a Comma Separated Values (CSV) file, which stores attributes and geometries in PostGIS. In this recipe, we will use the approach of importing such a file using the PostgreSQL COPY command and a couple of PostGIS functions.

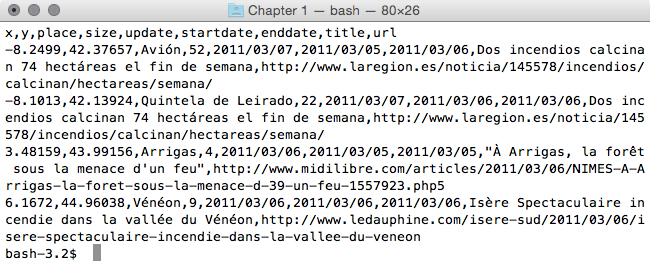

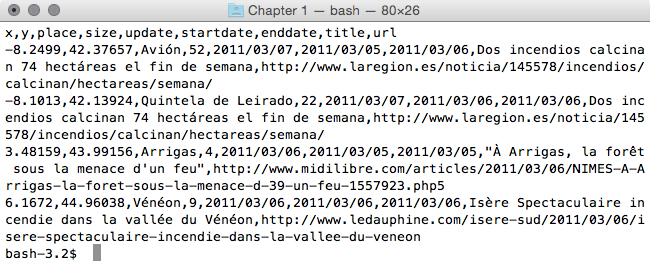

We will import the firenews.csv file that stores a series of web news collected from various RSS feeds related to forest fires in Europe in the context of the European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS), available at http://effis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/.

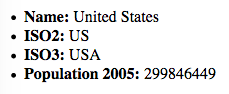

For each news feed, there are attributes such as place name, size of the fire in hectares, URL, and so on. Most importantly, there are the x and y fields that give the position of the geolocalized news in decimal degrees (in the WGS 84 spatial reference system, SRID = 4326).

For Windows machines, it is necessary to install OSGeo4W, a set of open source geographical libraries that will allow the manipulation of the datasets. The link is: https://trac.osgeo.org/osgeo4w/

In addition, include the OSGeo4W and the Postgres binary folders in the Path environment variable to be able to execute the commands from any location in your PC.

The steps you need to follow to complete this recipe are as shown:

$ cd ~/postgis_cookbook/data/chp01/

$ head -n 5 firenews.csv

The output of the preceding command is as shown:

$ psql -U me -d postgis_cookbook

postgis_cookbook=> CREATE EXTENSION postgis;

postgis_cookbook=> CREATE SCHEMA chp01;

postgis_cookbook=> CREATE TABLE chp01.firenews

(

x float8,

y float8,

place varchar(100),

size float8,

update date,

startdate date,

enddate date,

title varchar(255),

url varchar(255),

the_geom geometry(POINT, 4326)

);

postgis_cookbook=> COPY chp01.firenews (

x, y, place, size, update, startdate,

enddate, title, url

) FROM '/tmp/firenews.csv' WITH CSV HEADER;

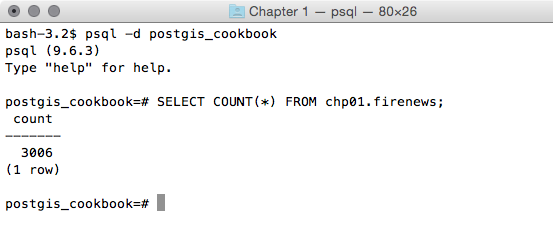

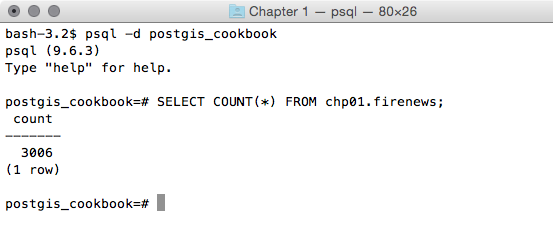

postgis_cookbook=> SELECT COUNT(*) FROM chp01.firenews;

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

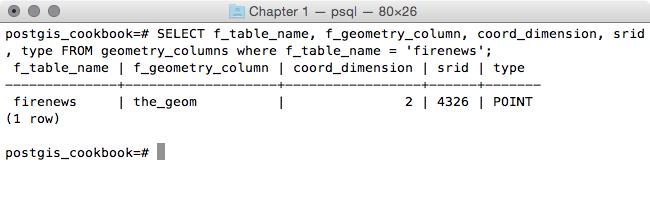

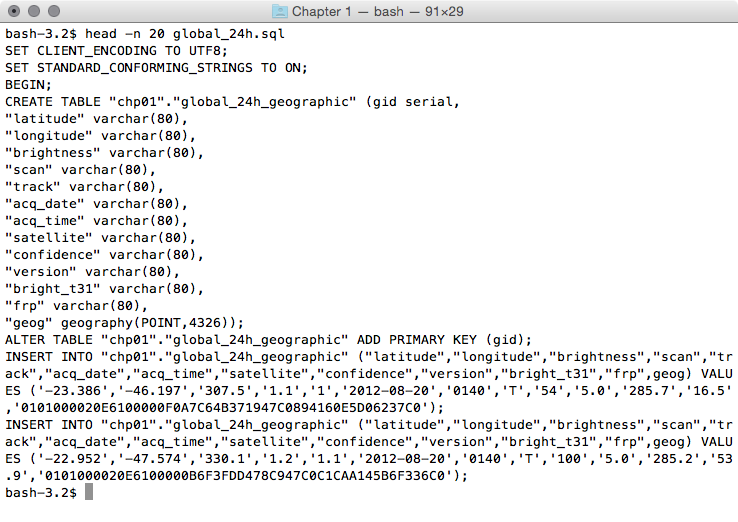

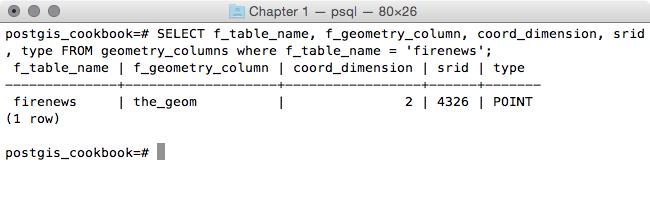

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT f_table_name,

f_geometry_column, coord_dimension, srid, type

FROM geometry_columns where f_table_name = 'firenews';

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

In PostGIS 2.0, you can still use the AddGeometryColumn function if you wish; however, you need to set its use_typmod parameter to false.

postgis_cookbook=> UPDATE chp01.firenews

SET the_geom = ST_SetSRID(ST_MakePoint(x,y), 4326); postgis_cookbook=> UPDATE chp01.firenews

SET the_geom = ST_PointFromText('POINT(' || x || ' ' || y || ')',

4326);

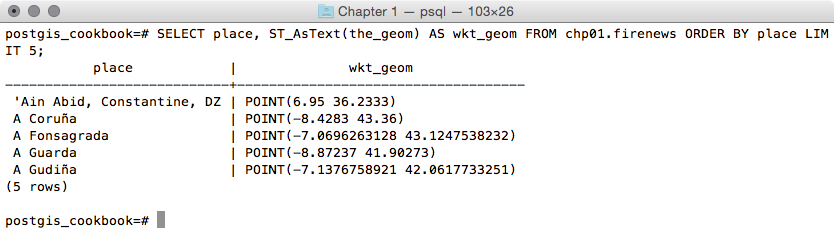

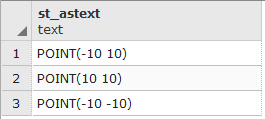

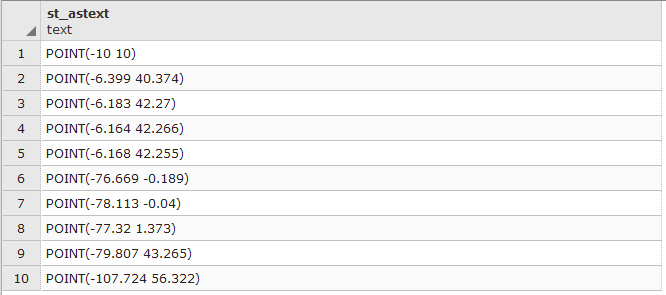

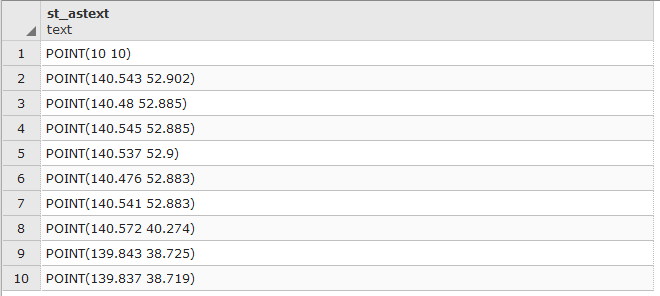

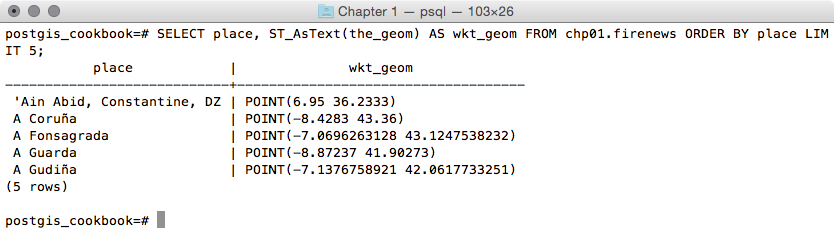

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT place, ST_AsText(the_geom) AS wkt_geom

FROM chp01.firenews ORDER BY place LIMIT 5;

The output of the preceding comment is as follows:

postgis_cookbook=> CREATE INDEX idx_firenews_geom

ON chp01.firenews USING GIST (the_geom);

This recipe showed you how to load nonspatial tabular data (in CSV format) in PostGIS using the COPY PostgreSQL command.

After creating the table and copying the CSV file rows to the PostgreSQL table, you updated the geometric column using one of the geometry constructor functions that PostGIS provides (ST_MakePoint and ST_PointFromText for bi-dimensional points).

These geometry constructors (in this case, ST_MakePoint and ST_PointFromText) must always provide the spatial reference system identifier (SRID) together with the point coordinates to define the point geometry.

Each geometric field added in any table in the database is tracked with a record in the geometry_columns PostGIS metadata view. In the previous PostGIS version (< 2.0), the geometry_fields view was a table and needed to be manually updated, possibly with the convenient AddGeometryColumn function.

For the same reason, to maintain the updated geometry_columns view when dropping a geometry column or removing a spatial table in the previous PostGIS versions, there were the DropGeometryColumn and DropGeometryTable functions. With PostGIS 2.0 and newer, you don't need to use these functions any more, but you can safely remove the column or the table with the standard ALTER TABLE, DROP COLUMN, and DROP TABLE SQL commands.

In the last step of the recipe, you have created a spatial index on the table to improve performance. Please be aware that as in the case of alphanumerical database fields, indexes improve performances only when reading data using the SELECT command. In this case, you are making a number of updates on the table (INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE); depending on the scenario, it could be less time consuming to drop and recreate the index after the updates.

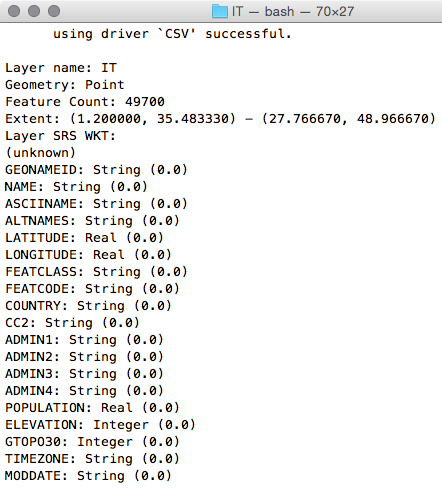

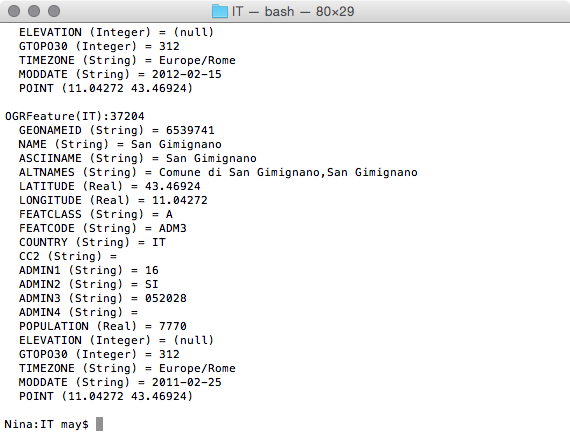

As an alternative approach to the previous recipe, you will import a CSV file to PostGIS using the ogr2ogr GDAL command and the GDAL OGR virtual format. The Geospatial Data Abstraction Library (GDAL) is a translator library for raster geospatial data formats. OGR is the related library that provides similar capabilities for vector data formats.

This time, as an extra step, you will import only a part of the features in the file and you will reproject them to a different spatial reference system.

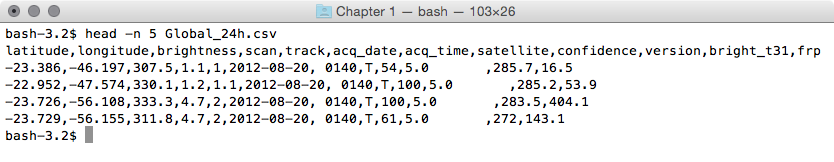

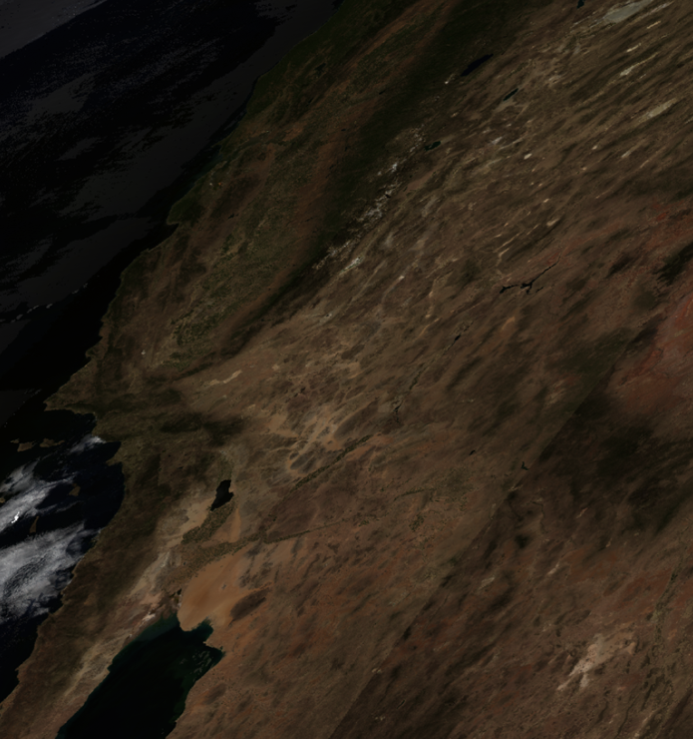

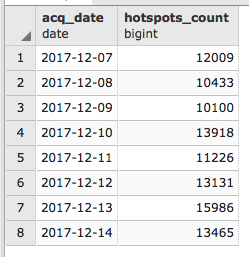

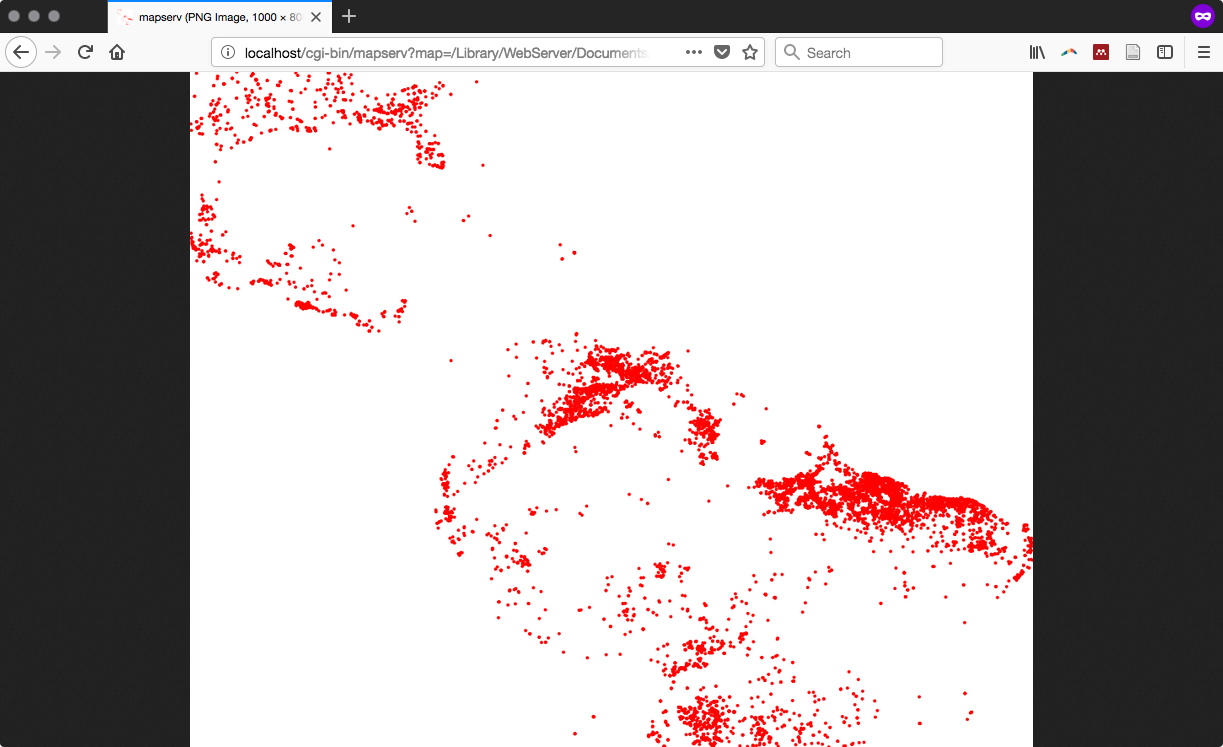

You will import the Global_24h.csv file to the PostGIS database from NASA's Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS).

You can copy the file from the dataset directory of the book for this chapter.

This file represents the active hotspots in the world detected by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) satellites in the last 24 hours. For each row, there are the coordinates of the hotspot (latitude, longitude) in decimal degrees (in the WGS 84 spatial reference system, SRID = 4326), and a series of useful fields such as the acquisition date, acquisition time, and satellite type, just to name a few.

You will import only the active fire data scanned by the satellite type marked as T (Terra MODIS), and you will project it using the Spherical Mercator projection coordinate system (EPSG:3857; it is sometimes marked as EPSG:900913, where the number 900913 represents Google in 1337 speak, as it was first widely used by Google Maps).

The steps you need to follow to complete this recipe are as follows:

$ cd ~/postgis_cookbook/data/chp01/

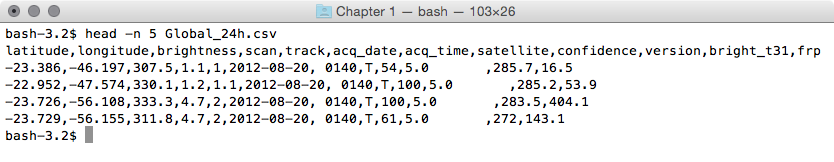

$ head -n 5 Global_24h.csv

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

<OGRVRTDataSource>

<OGRVRTLayer name="Global_24h">

<SrcDataSource>Global_24h.csv</SrcDataSource>

<GeometryType>wkbPoint</GeometryType>

<LayerSRS>EPSG:4326</LayerSRS>

<GeometryField encoding="PointFromColumns"

x="longitude" y="latitude"/>

</OGRVRTLayer>

</OGRVRTDataSource>

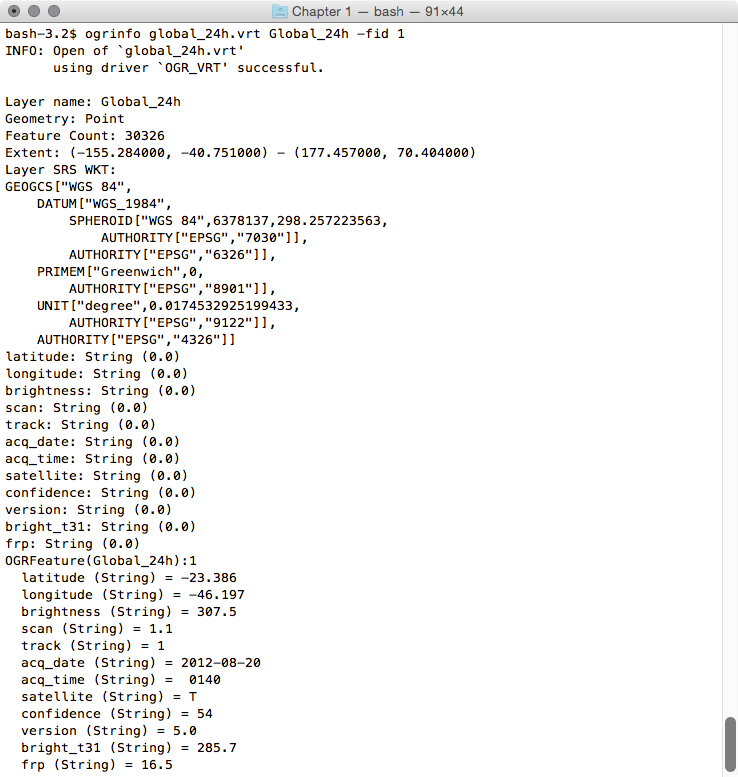

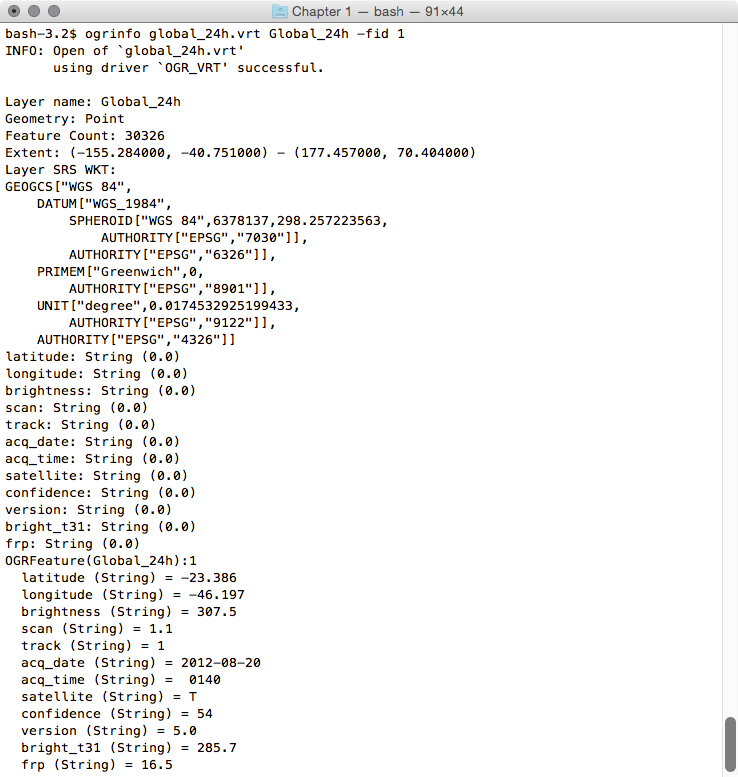

$ ogrinfo global_24h.vrt Global_24h -fid 1

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

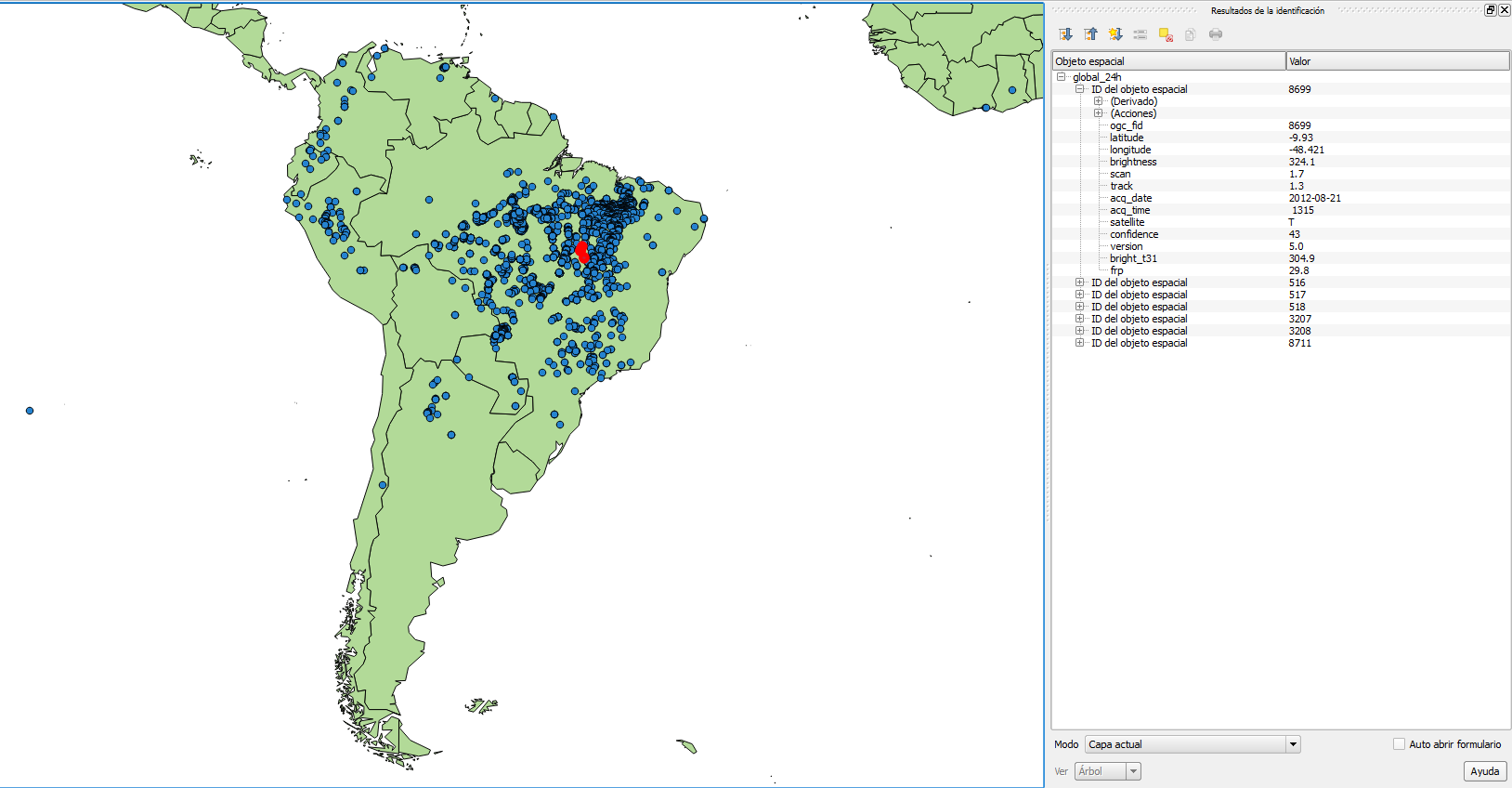

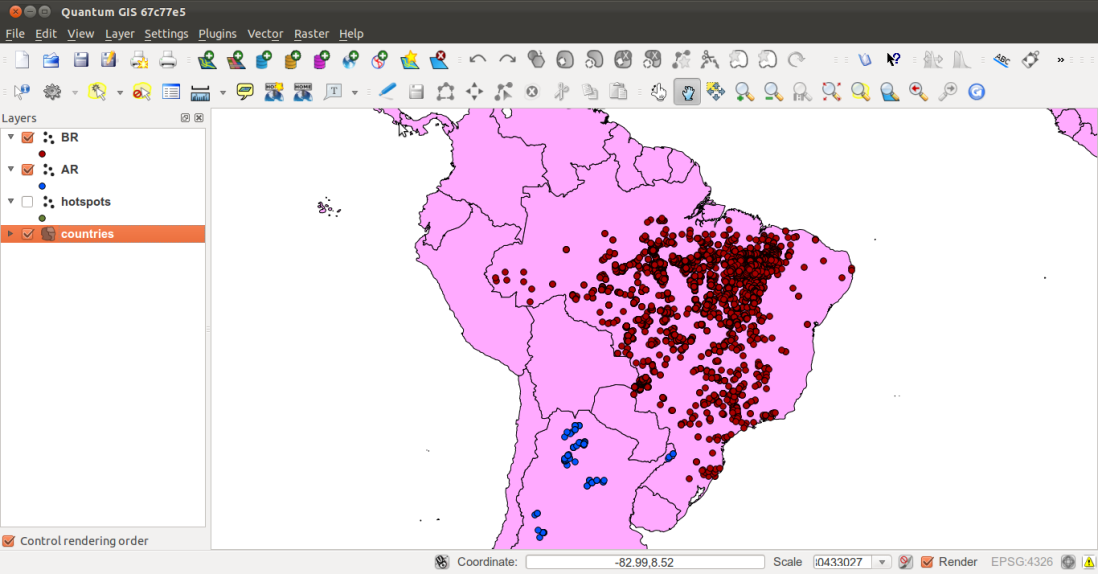

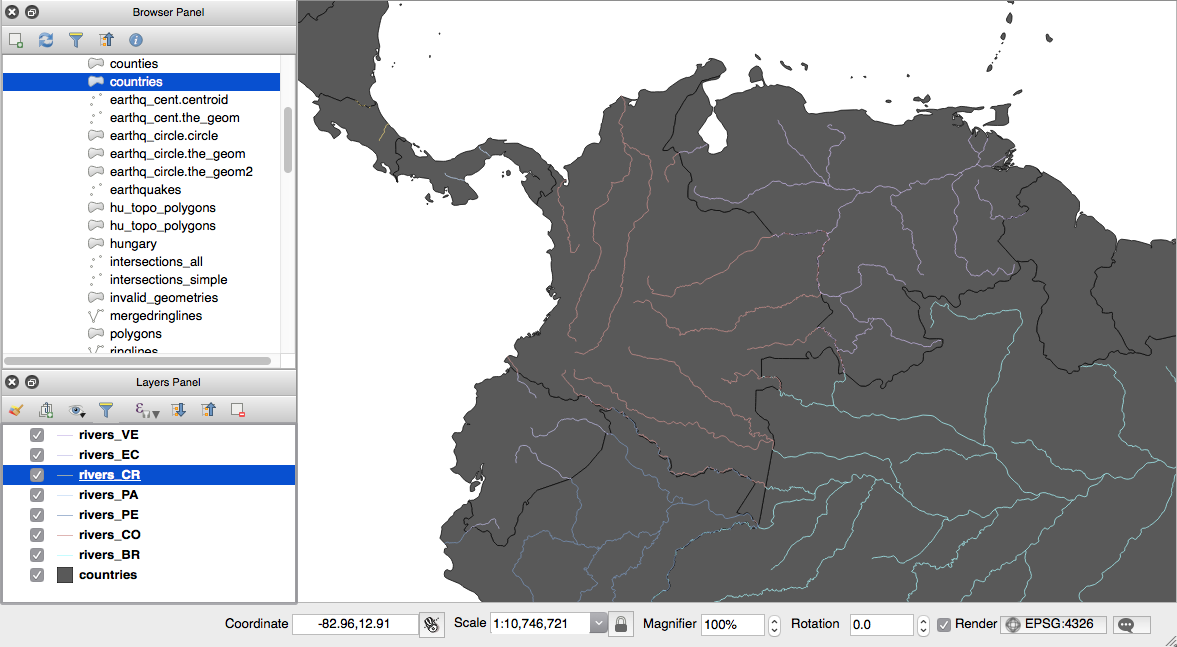

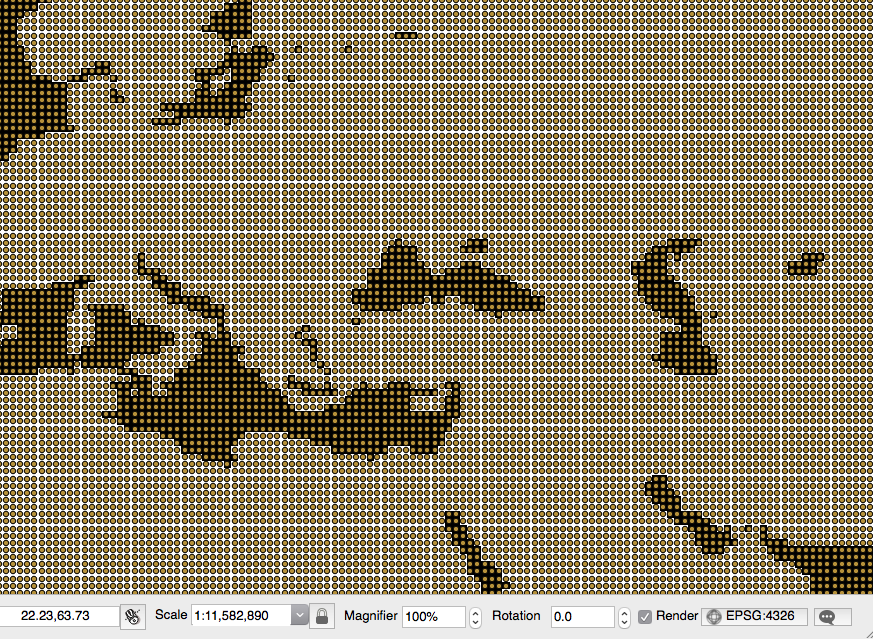

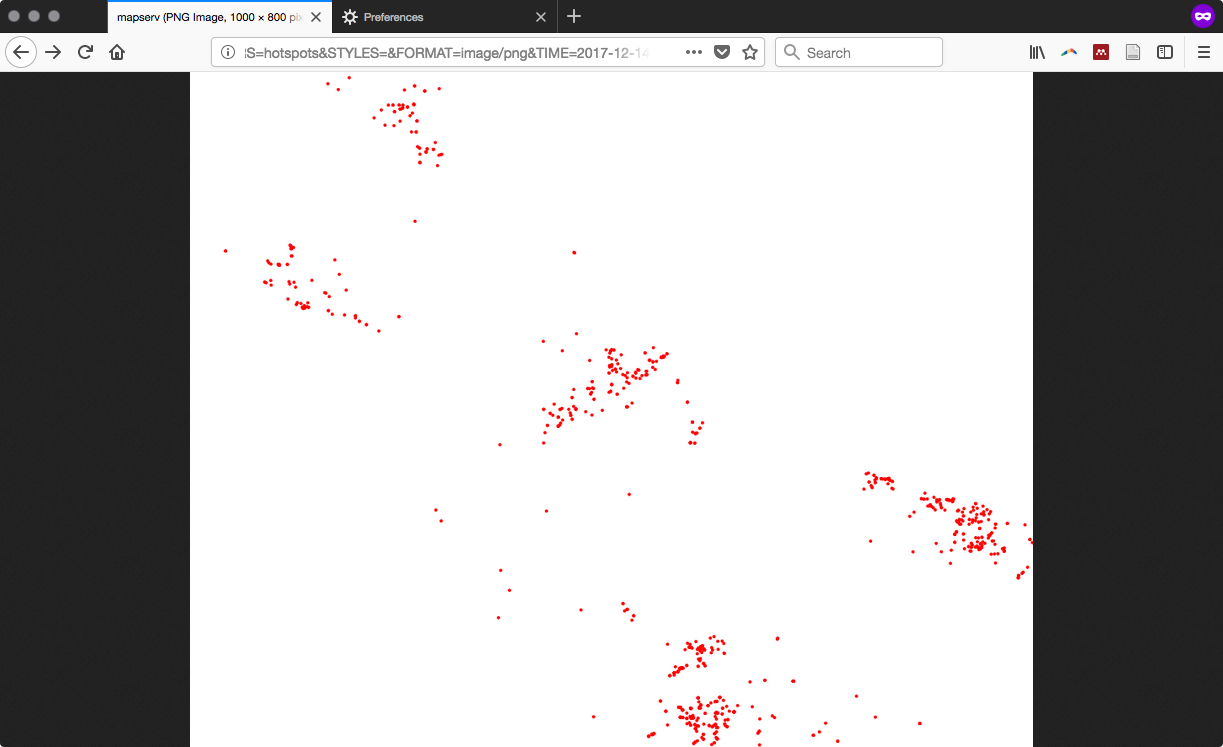

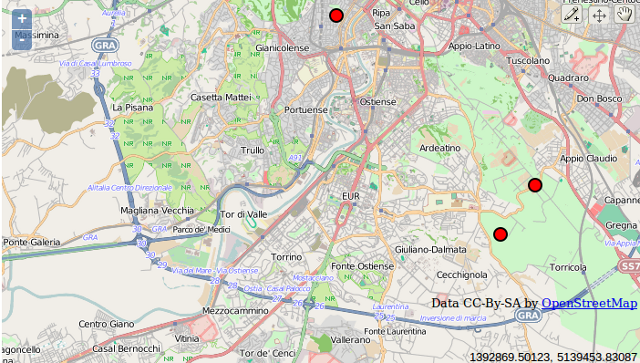

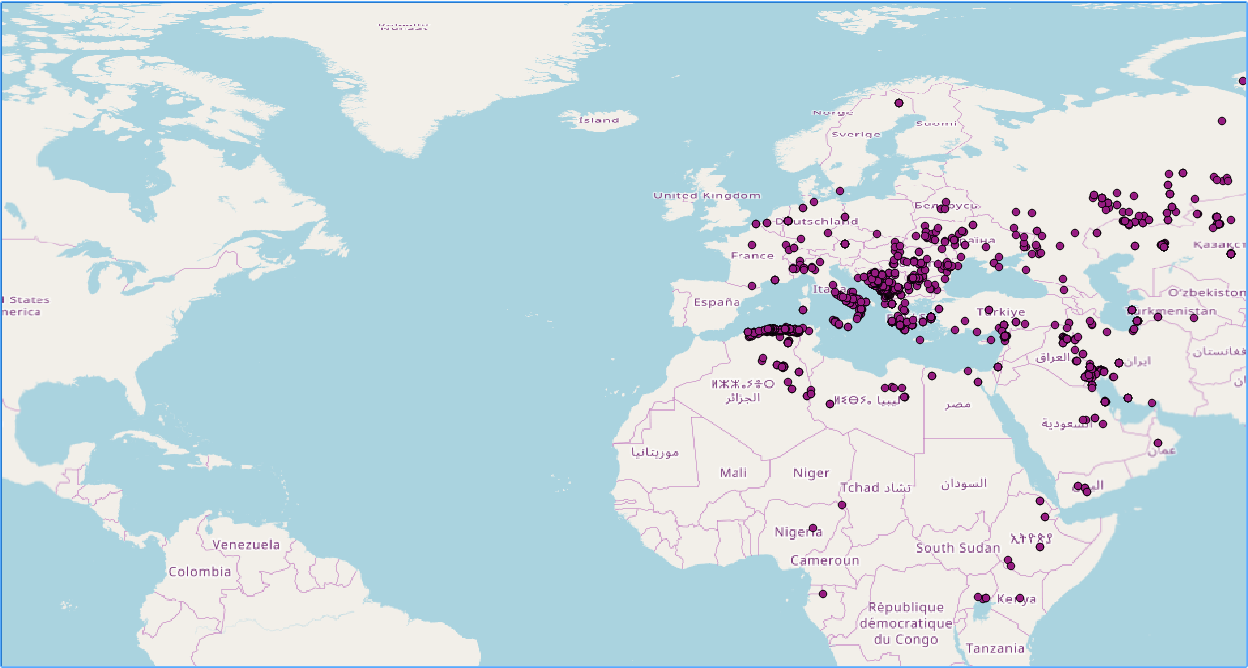

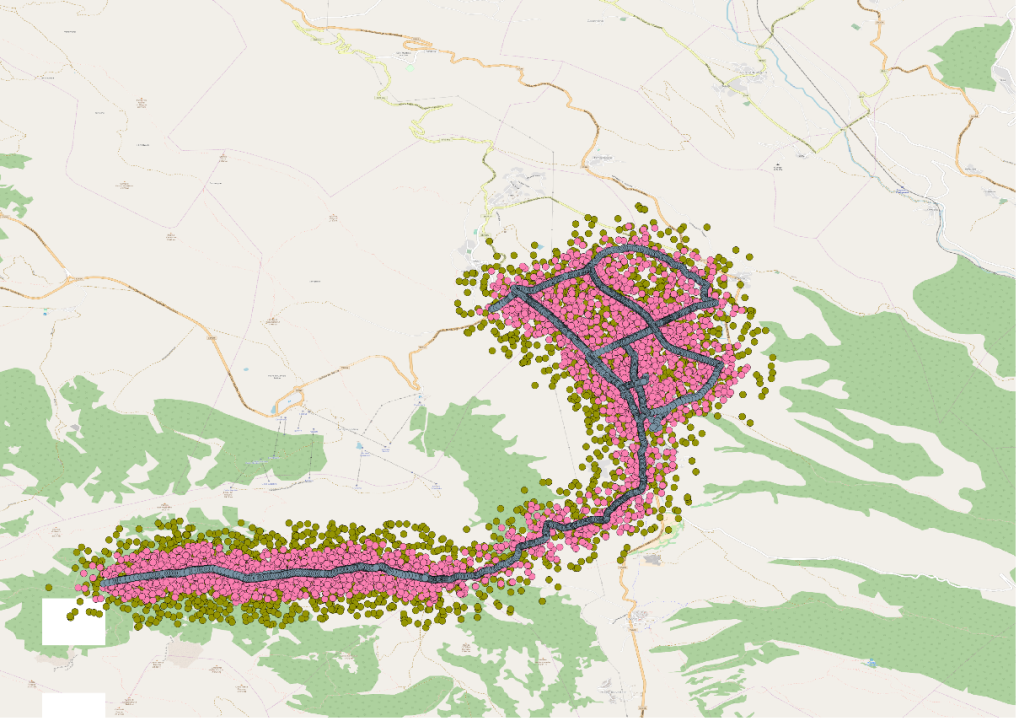

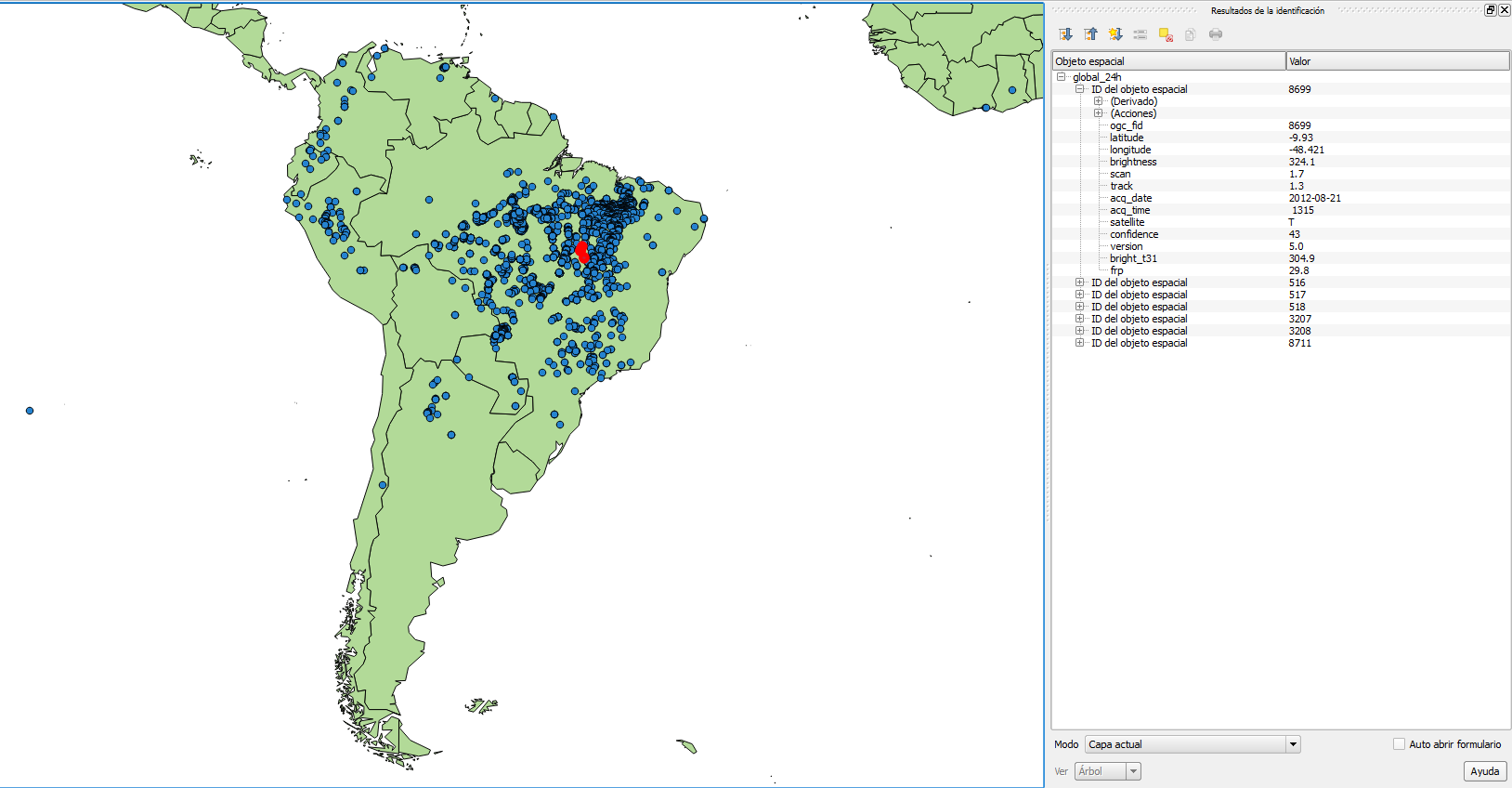

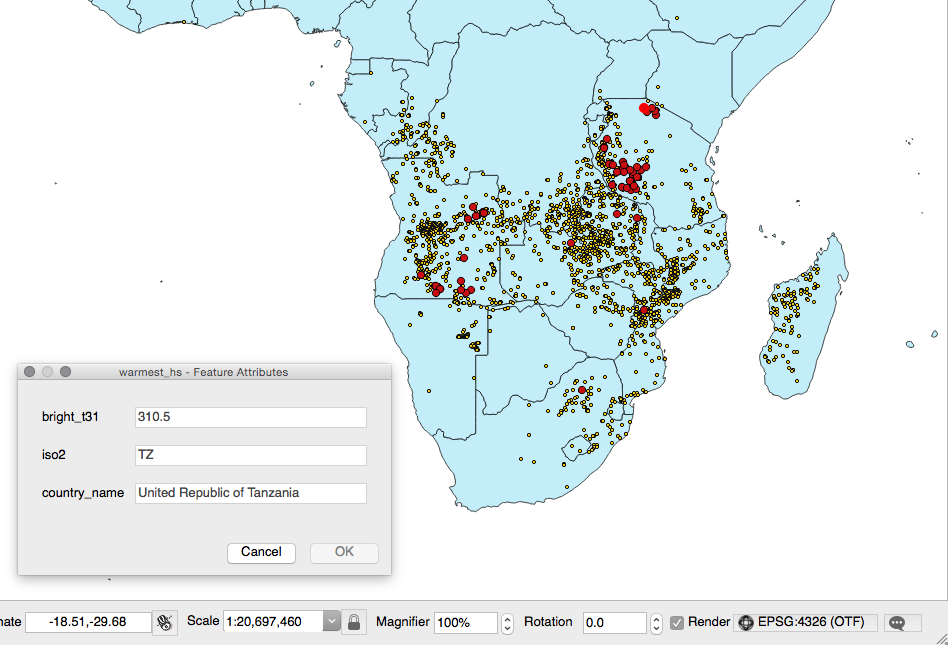

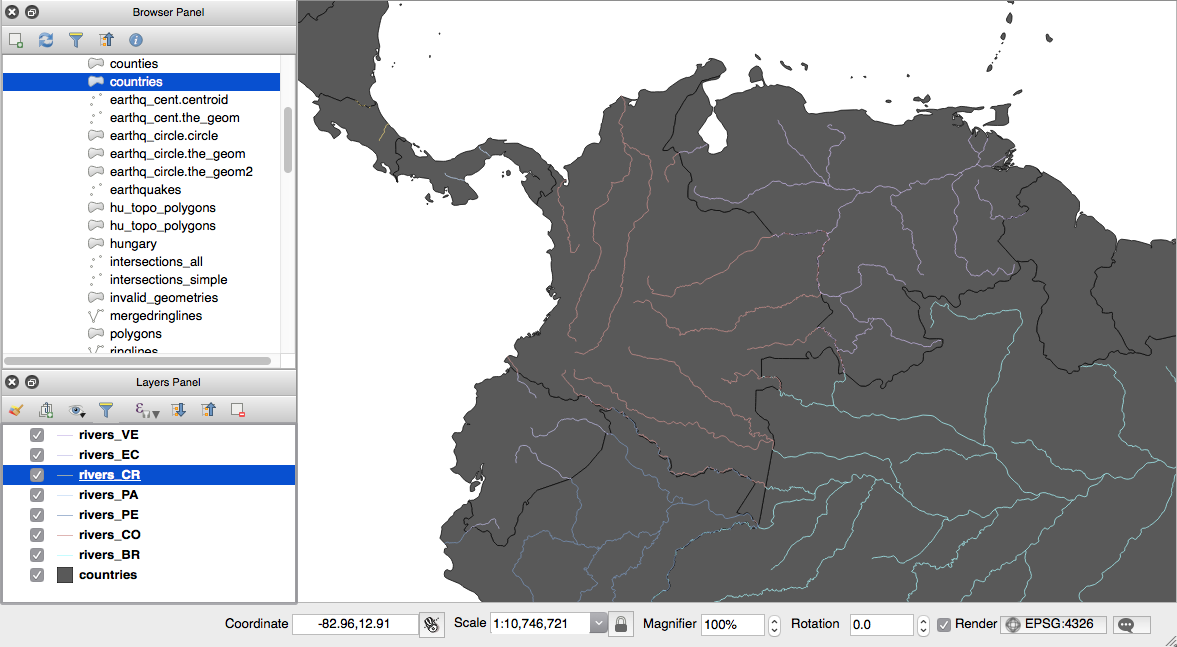

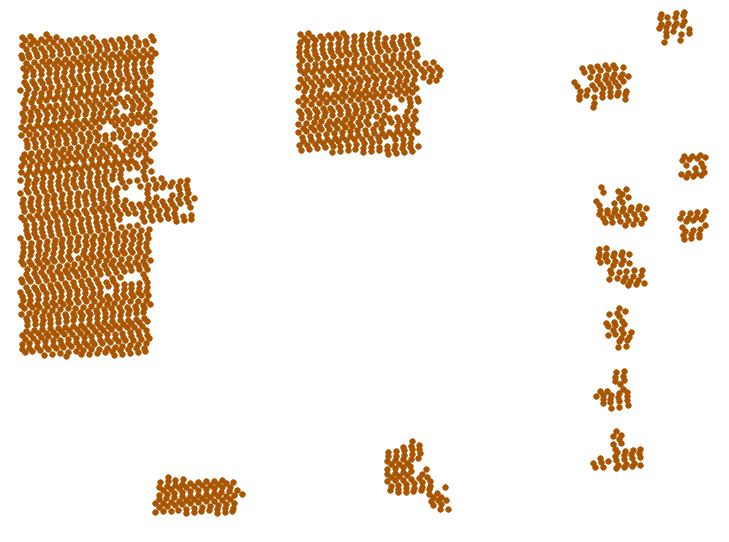

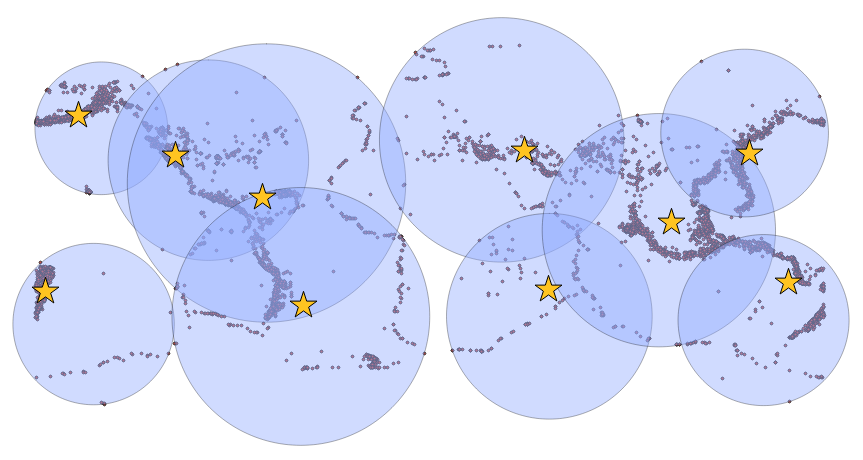

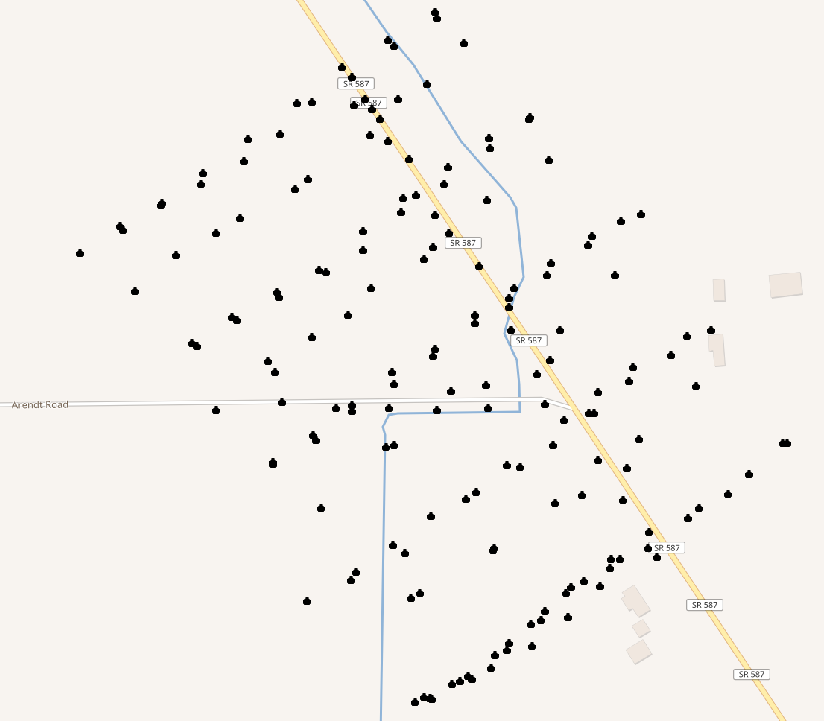

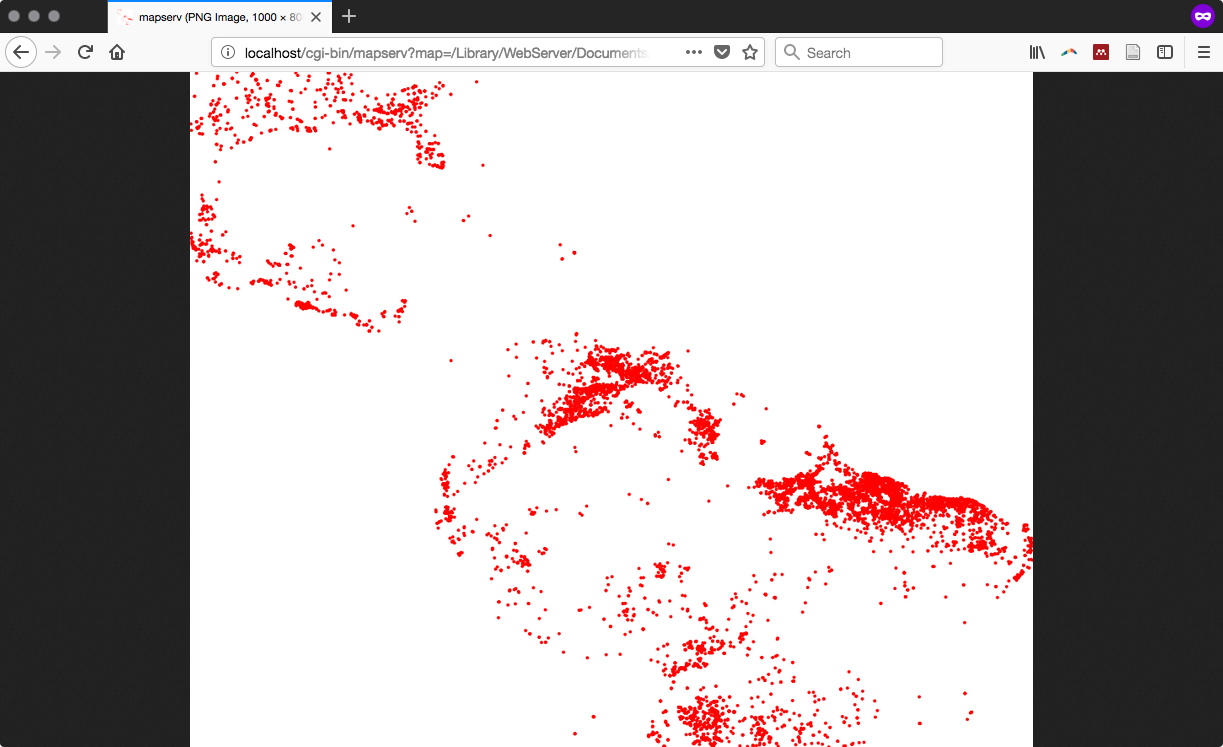

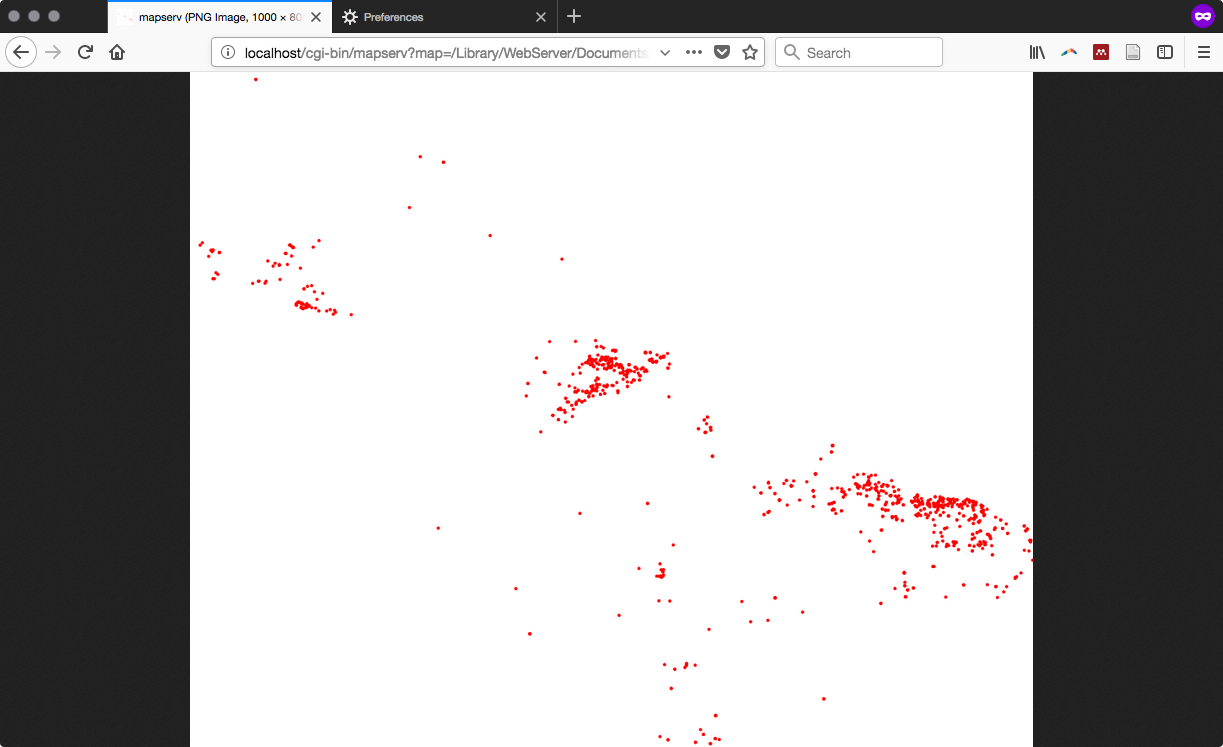

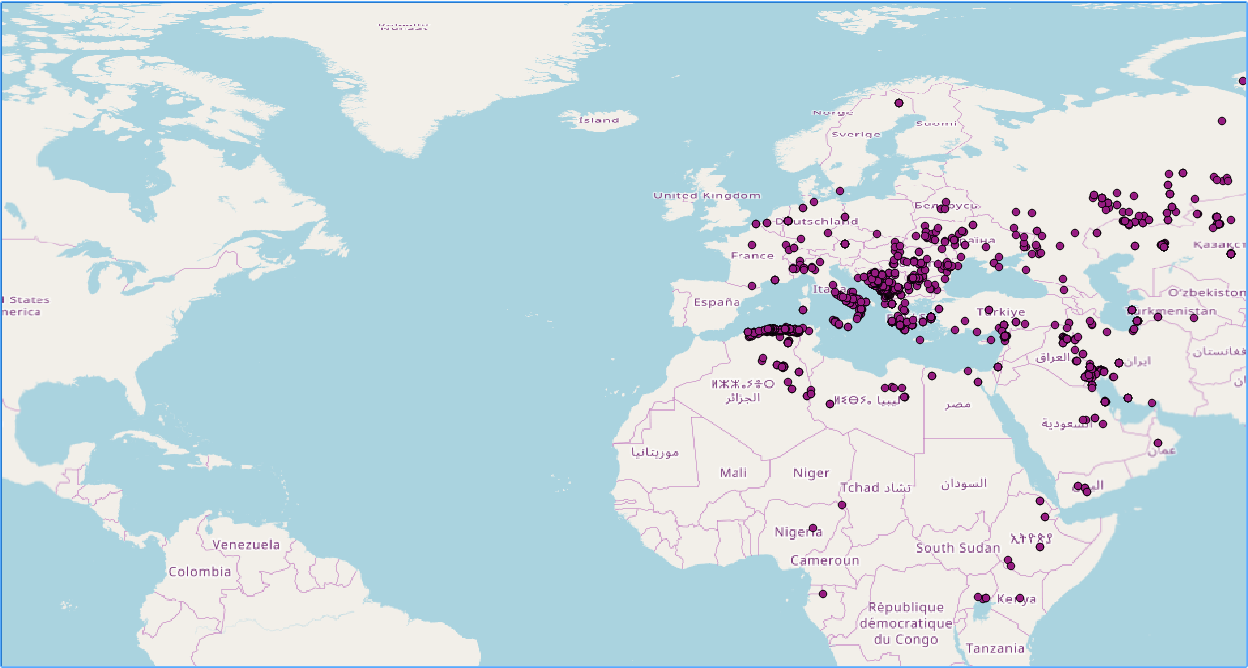

You can also try to open the virtual layer with a desktop GIS supporting a GDAL/OGR virtual driver such as Quantum GIS (QGIS). In the following screenshot, the Global_24h layer is displayed together with the shapefile of the countries that you can find in the dataset directory of the book:

$ ogr2ogr -f PostgreSQL -t_srs EPSG:3857

PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me' password='mypassword'"

-lco SCHEMA=chp01 global_24h.vrt -where "satellite='T'"

-lco GEOMETRY_NAME=the_geom

$ pg_dump -t chp01.global_24h --schema-only -U me postgis_cookbook

CREATE TABLE global_24h (

ogc_fid integer NOT NULL,

latitude character varying,

longitude character varying,

brightness character varying,

scan character varying,

track character varying,

acq_date character varying,

acq_time character varying,

satellite character varying,

confidence character varying,

version character varying,

bright_t31 character varying,

frp character varying,

the_geom public.geometry(Point,3857)

);

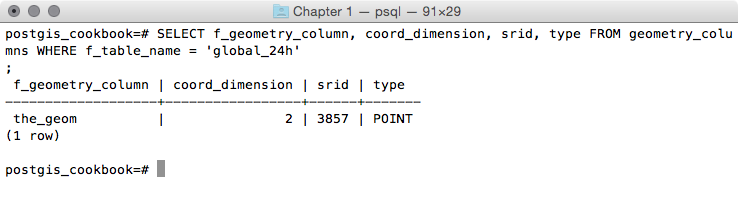

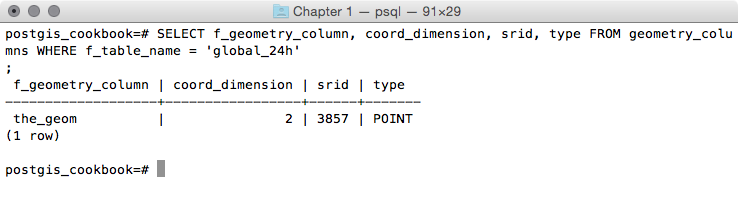

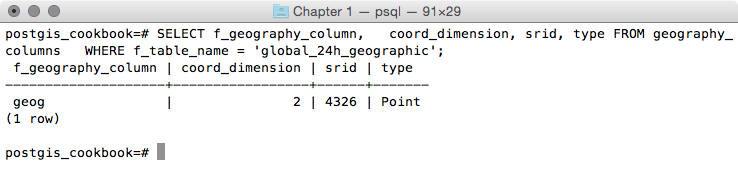

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT f_geometry_column, coord_dimension,

srid, type FROM geometry_columns

WHERE f_table_name = 'global_24h';

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

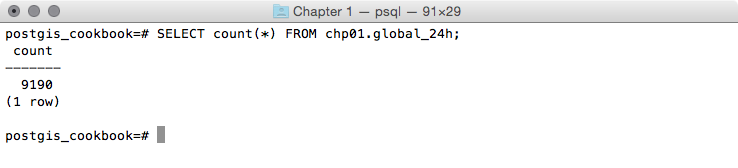

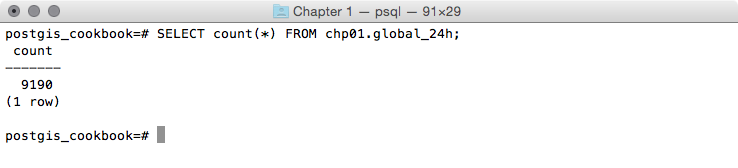

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT count(*) FROM chp01.global_24h;

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

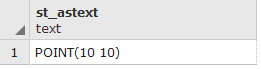

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT ST_AsEWKT(the_geom)

FROM chp01.global_24h LIMIT 1;

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

As mentioned in the GDAL documentation:

GDAL supports the reading and writing of nonspatial tabular data stored as a CSV file, but we need to use a virtual format to derive the geometry of the layers from attribute columns in the CSV file (the longitude and latitude coordinates for each point). For this purpose, you need to at least specify in the driver the path to the CSV file (the SrcDataSource element), the geometry type (the GeometryType element), the spatial reference definition for the layer (the LayerSRS element), and the way the driver can derive the geometric information (the GeometryField element).

There are many other options and reasons for using OGR virtual formats; if you are interested in developing a better understanding, please refer to the GDAL documentation available at http://www.gdal.org/drv_vrt.html.

After a virtual format is correctly created, the original flat nonspatial dataset is spatially supported by GDAL and software-based on GDAL. This is the reason why we can manipulate these files with GDAL commands such as ogrinfo and ogr2ogr, and with desktop GIS software such as QGIS.

Once we have verified that GDAL can correctly read the features from the virtual driver, we can easily import them in PostGIS using the popular ogr2ogr command-line utility. The ogr2ogr command has a plethora of options, so refer to its documentation at http://www.gdal.org/ogr2ogr.html for a more in-depth discussion.

In this recipe, you have just seen some of these options, such as:

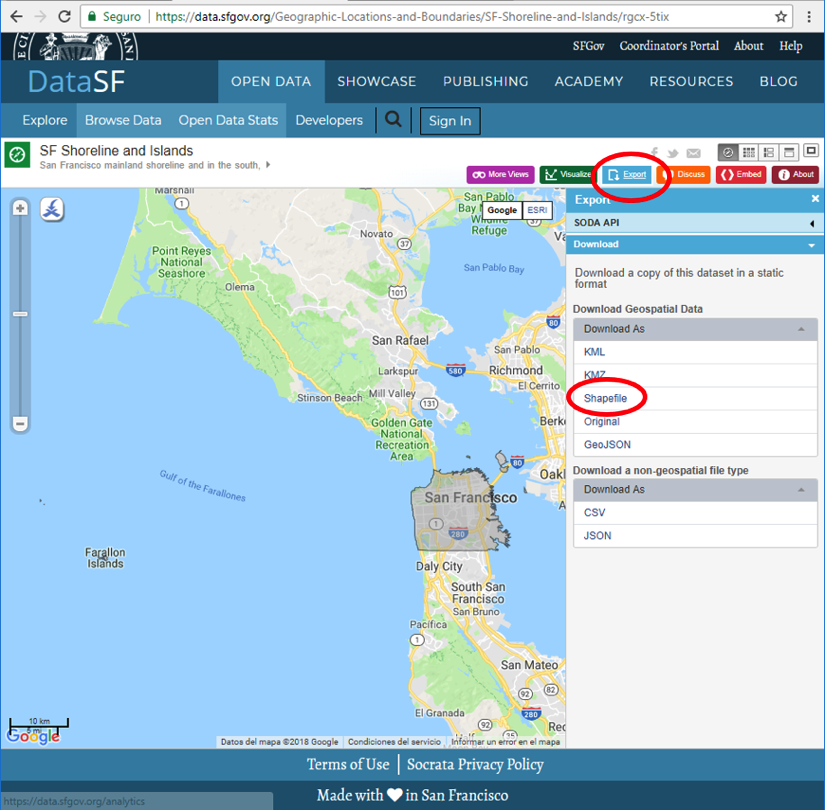

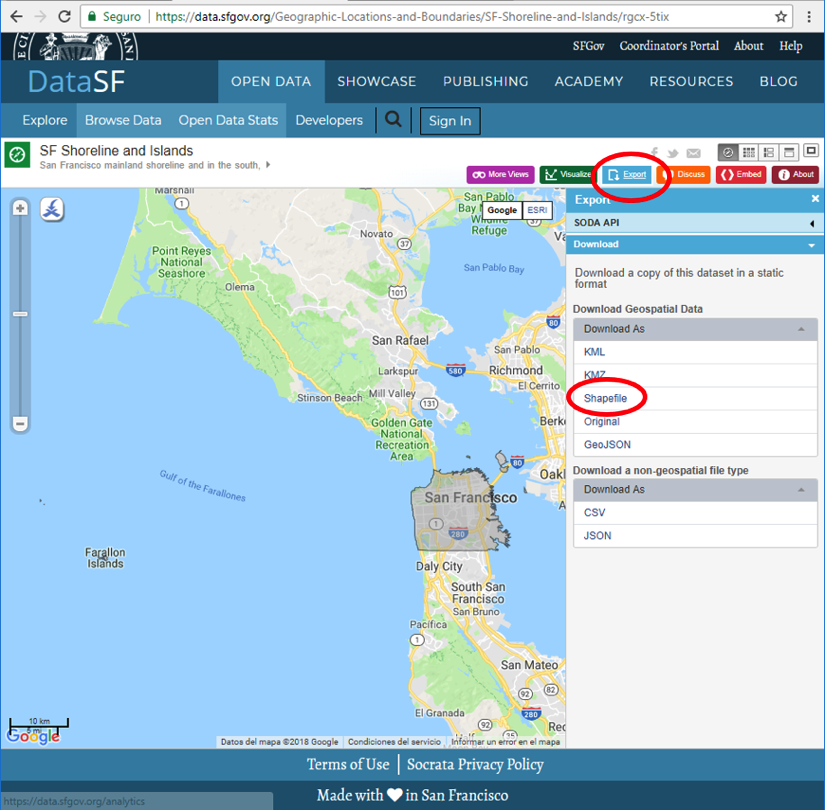

If you need to import a shapefile in PostGIS, you have at least a couple of options such as the ogr2ogr GDAL command, as you have seen previously, or the shp2pgsql PostGIS command.

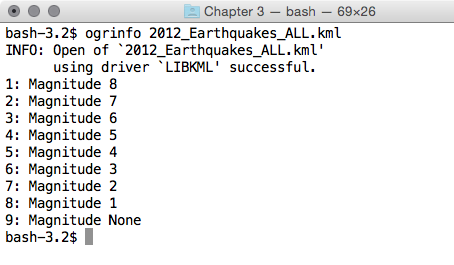

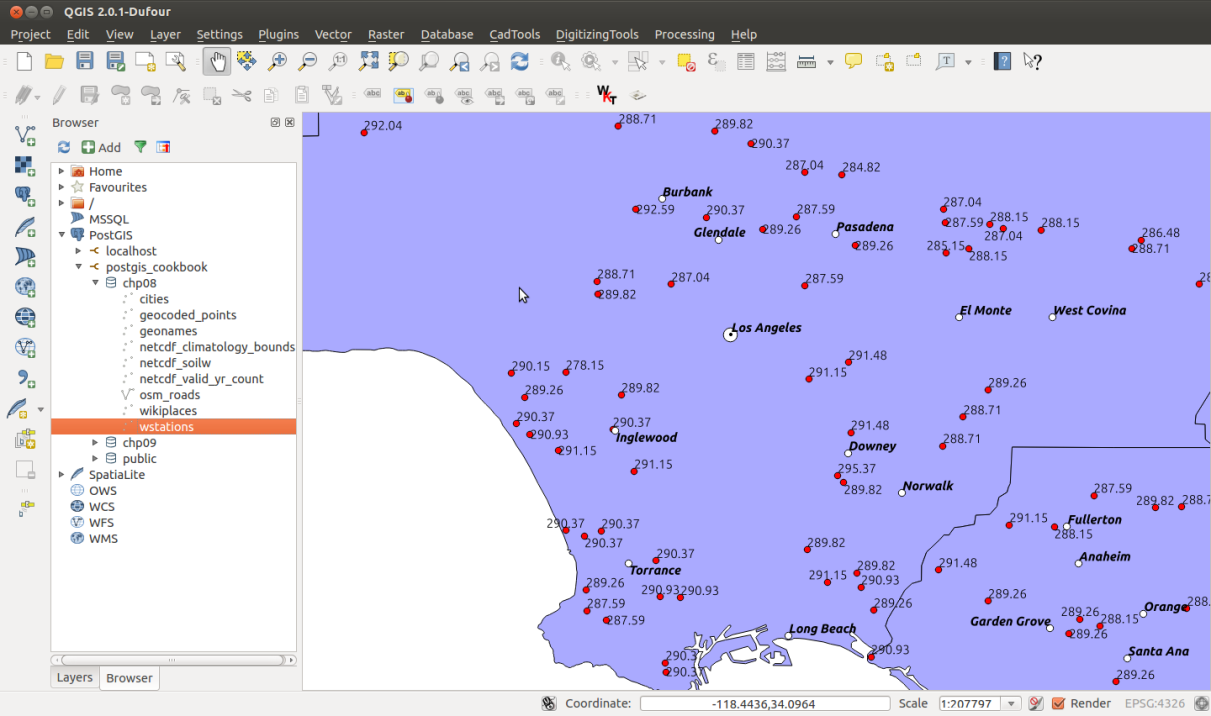

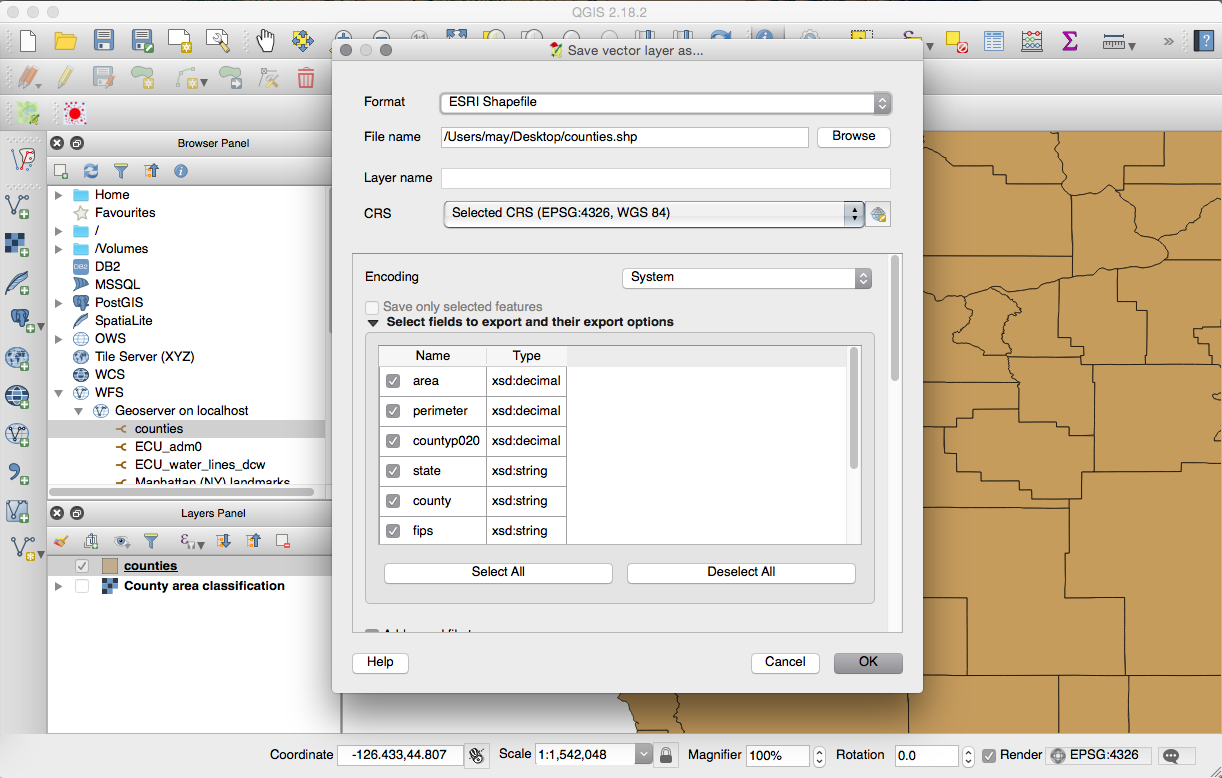

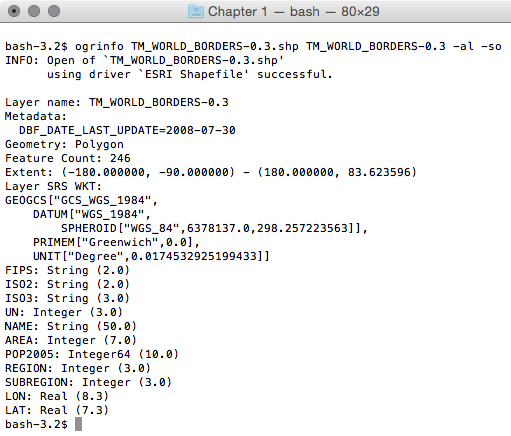

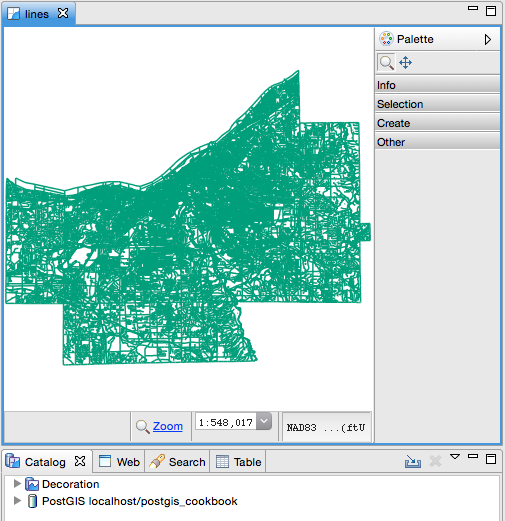

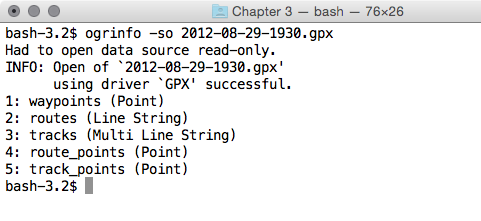

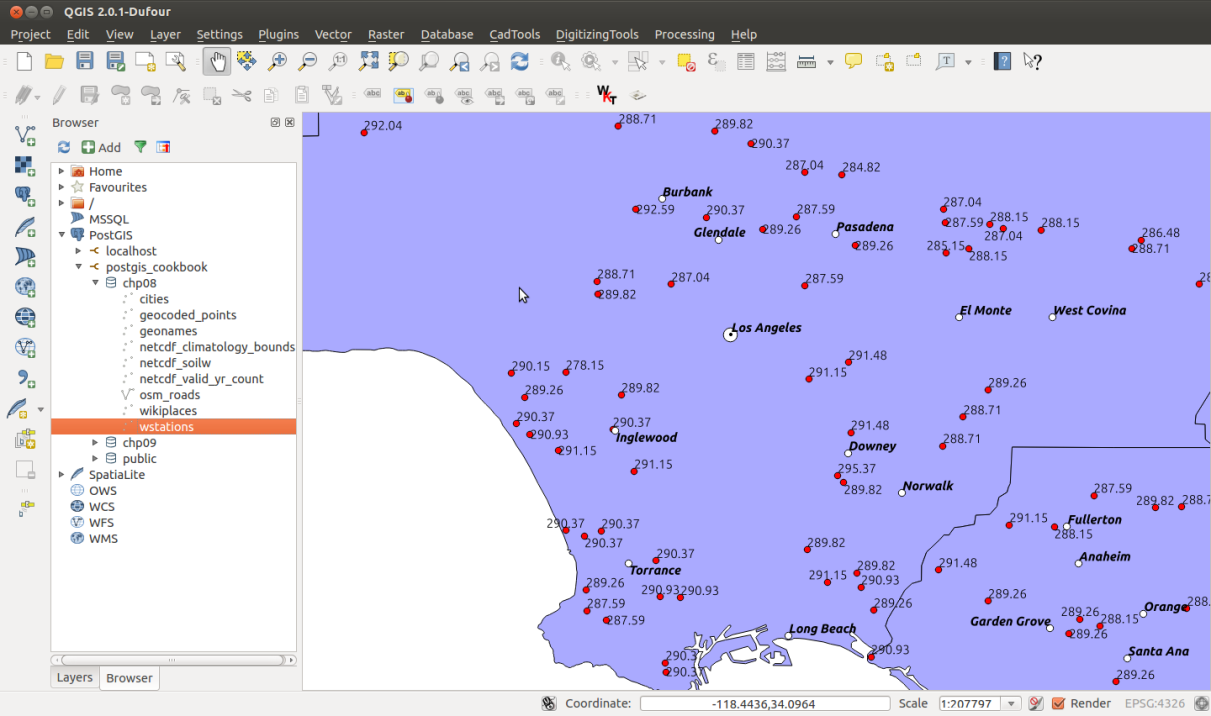

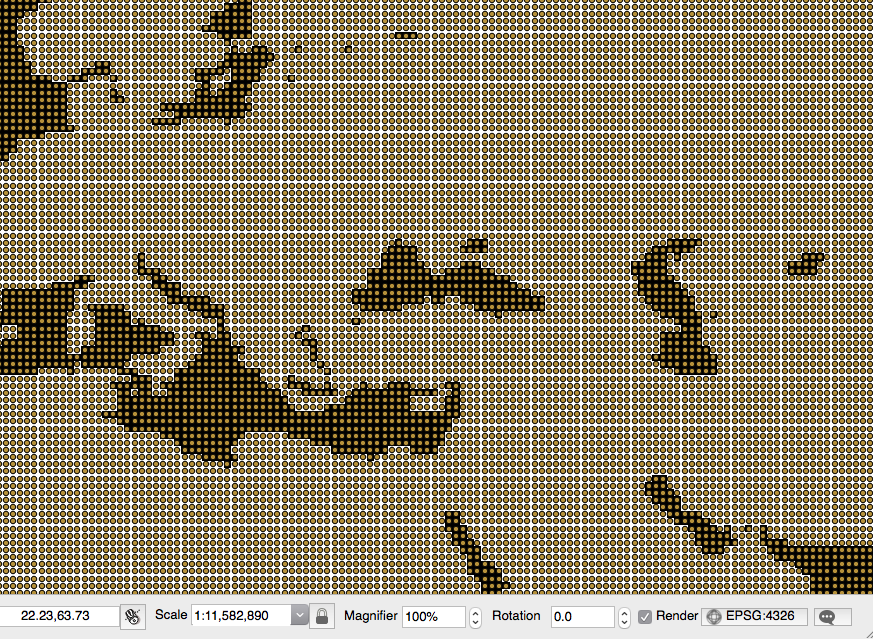

In this recipe, you will load a shapefile in the database using the shp2pgsql command, analyze it with the ogrinfo command, and display it in QGIS desktop software.

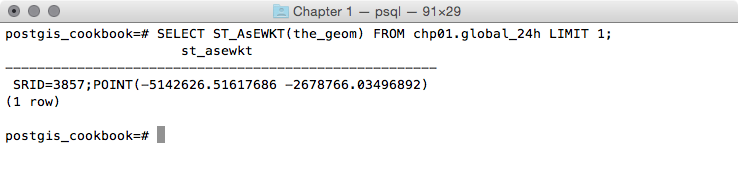

The steps you need to follow to complete this recipe are as follows:

$ ogr2ogr global_24h.shp global_24h.vrt

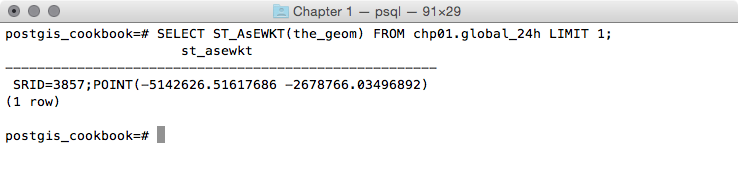

$ shp2pgsql -G -I global_24h.shp

chp01.global_24h_geographic > global_24h.sql

$ head -n 20 global_24h.sql

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

$ psql -U me -d postgis_cookbook -f global_24h.sql

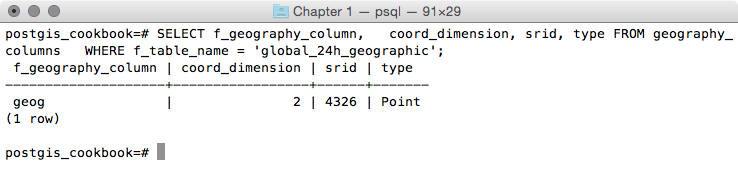

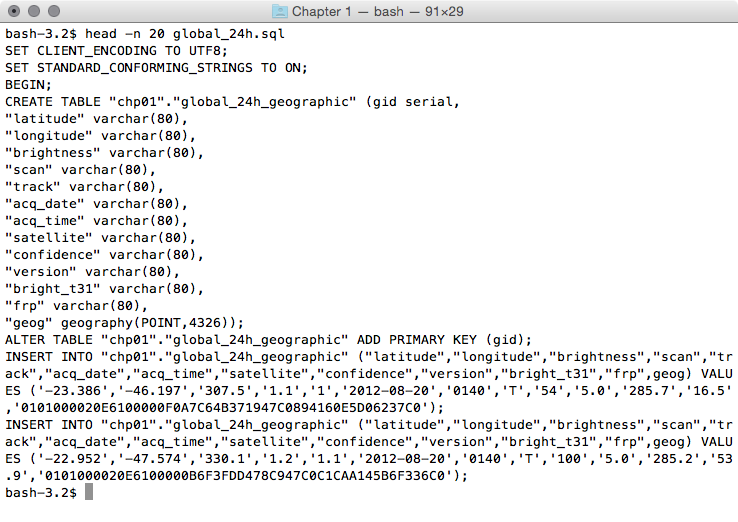

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT f_geography_column, coord_dimension,

srid, type FROM geography_columns

WHERE f_table_name = 'global_24h_geographic';

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

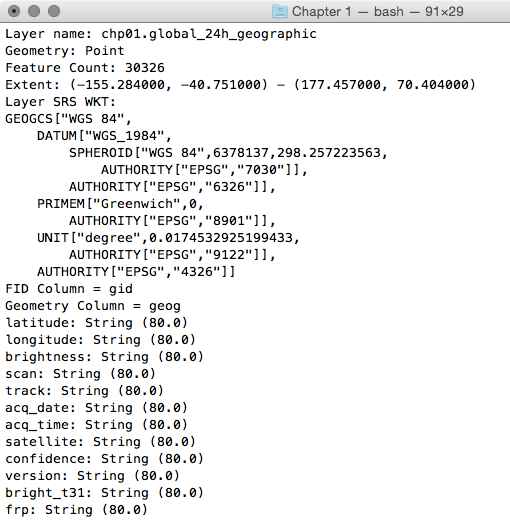

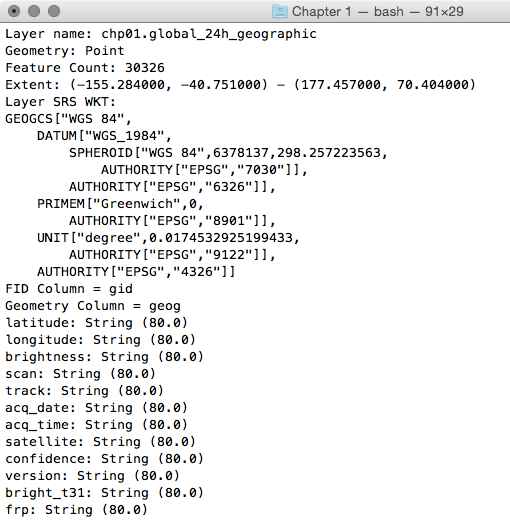

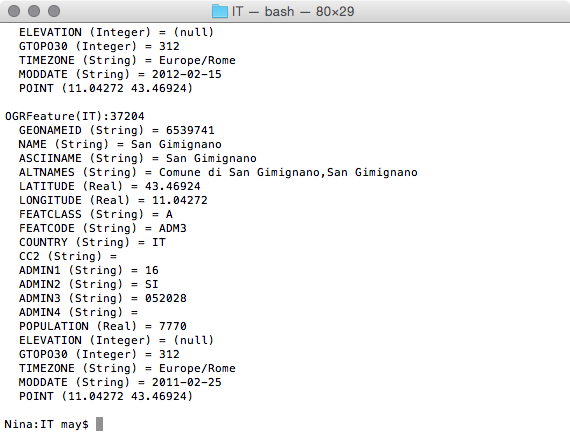

$ ogrinfo PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me'

password='mypassword'" chp01.global_24h_geographic -fid 1

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

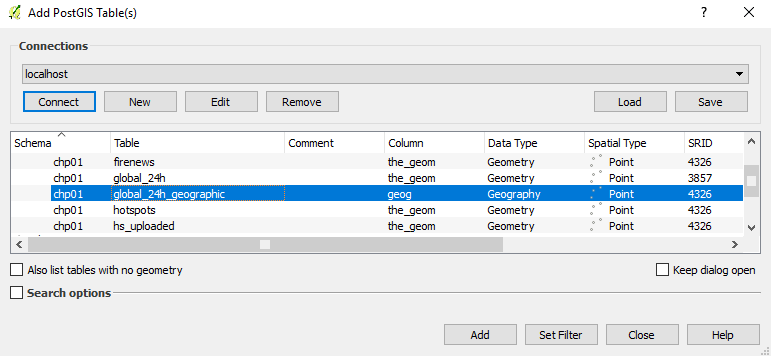

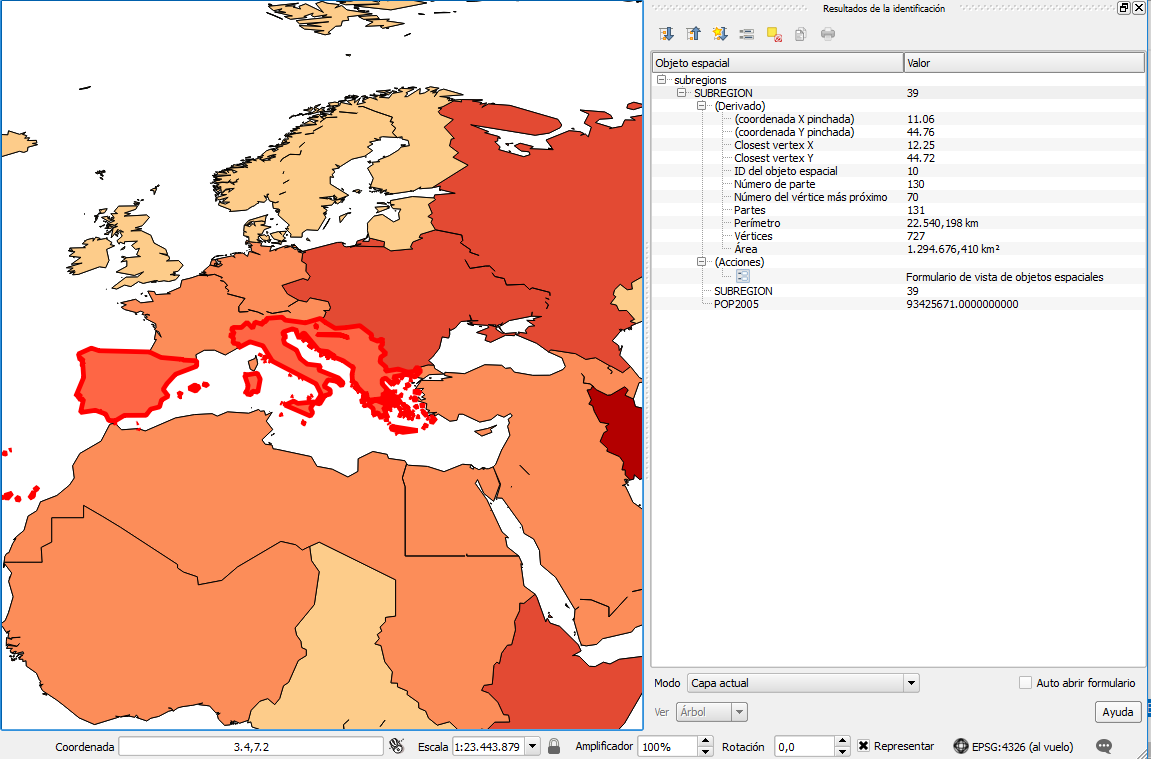

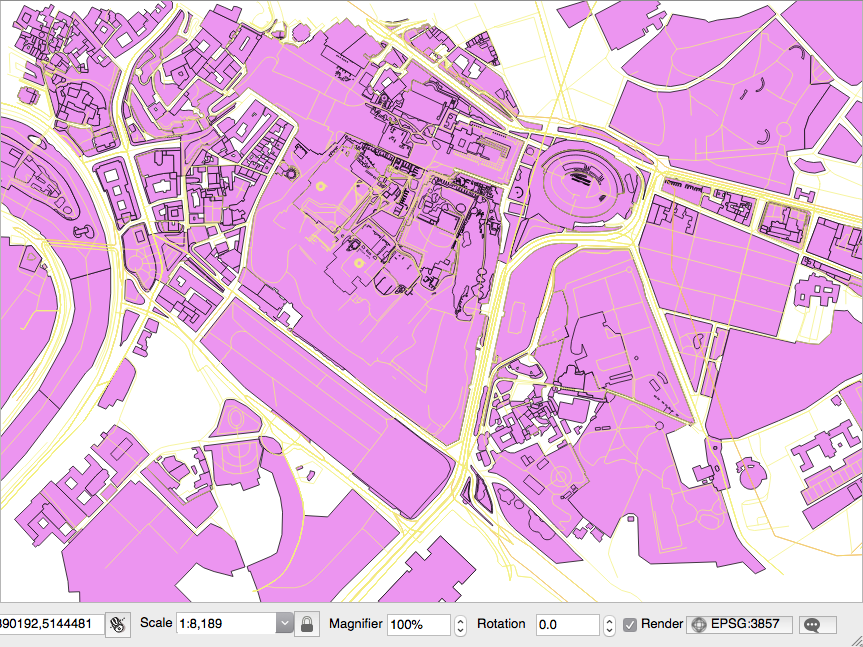

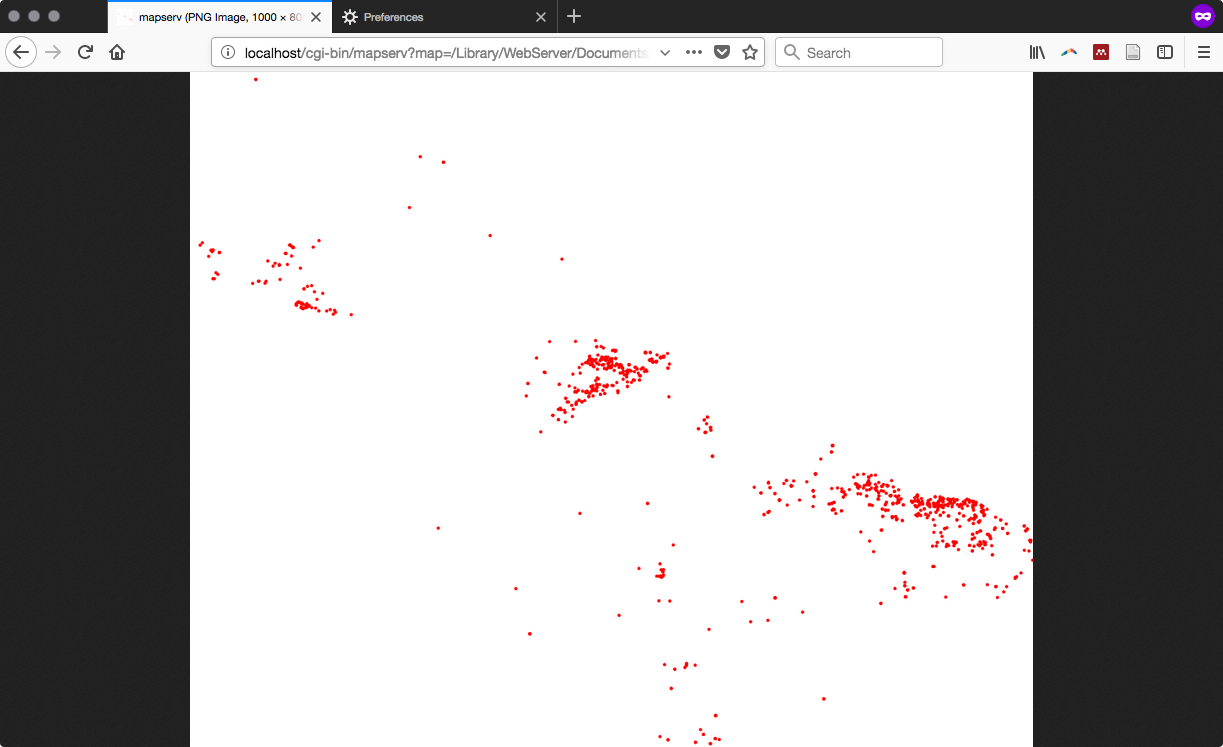

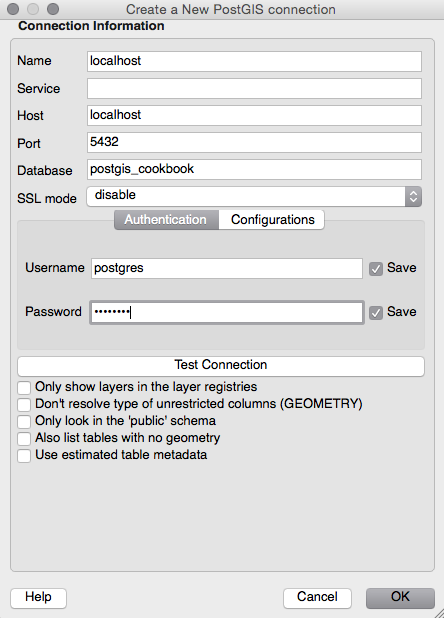

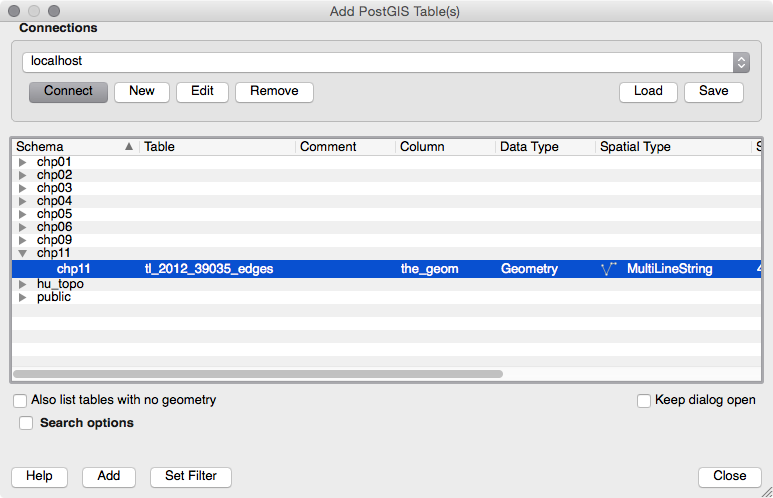

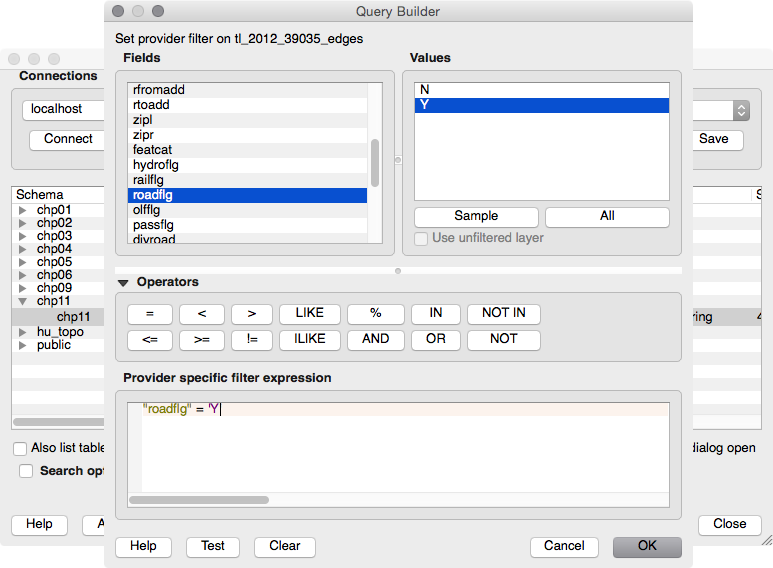

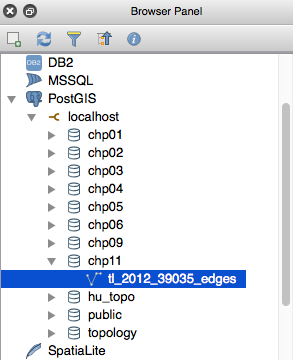

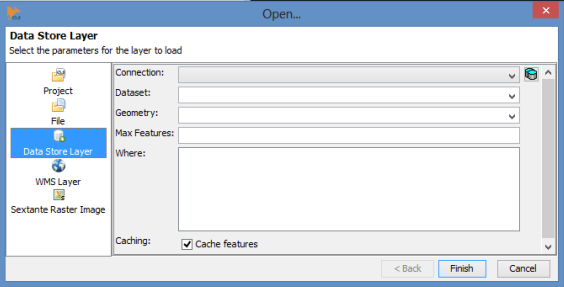

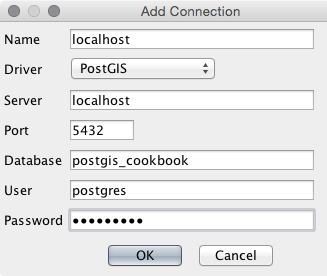

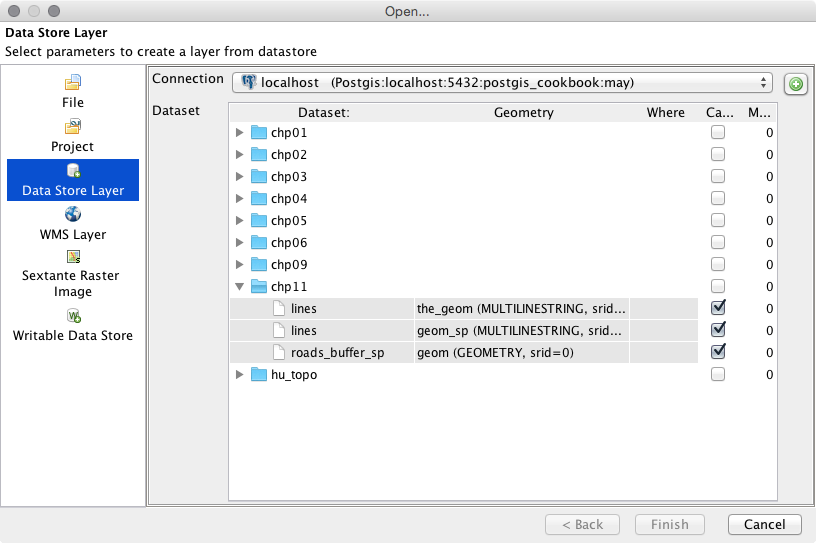

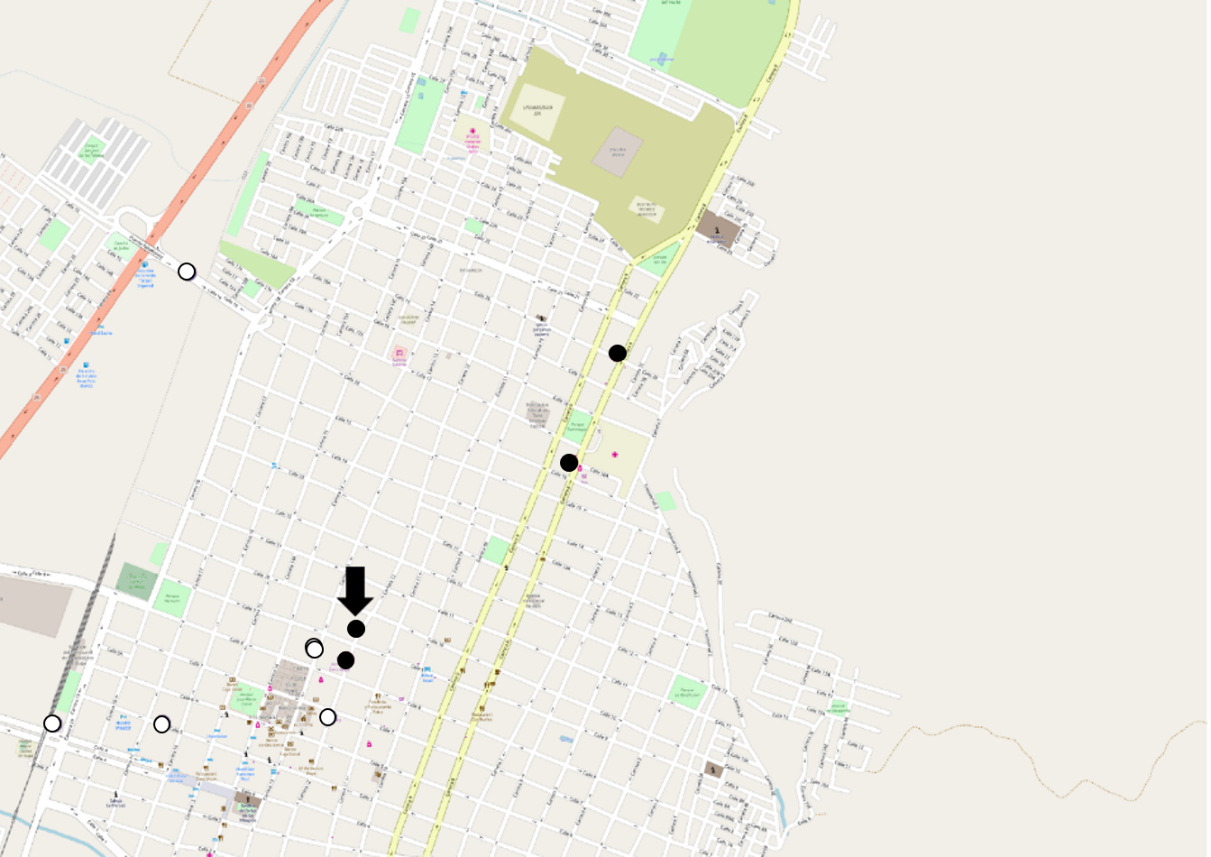

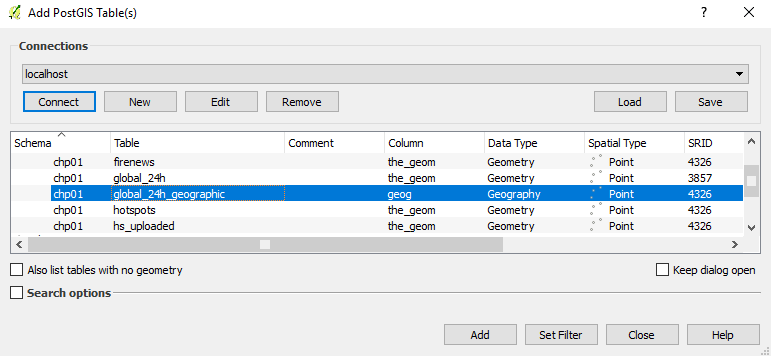

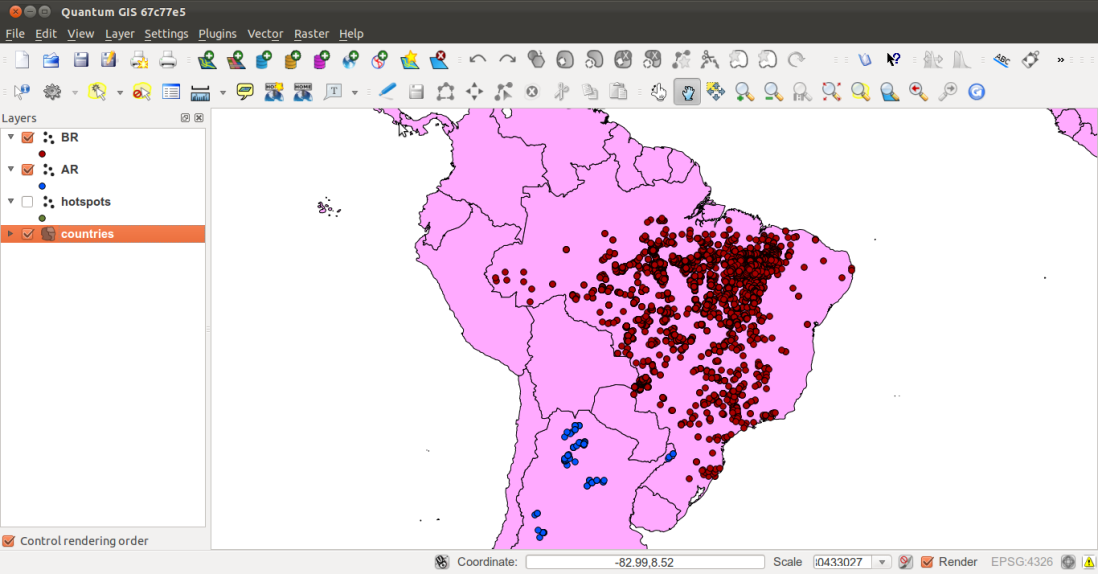

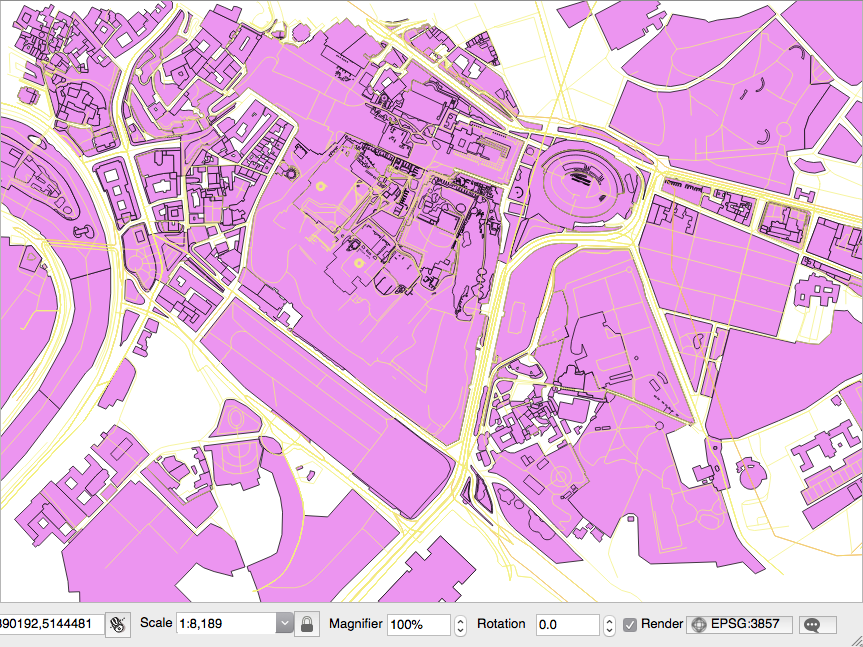

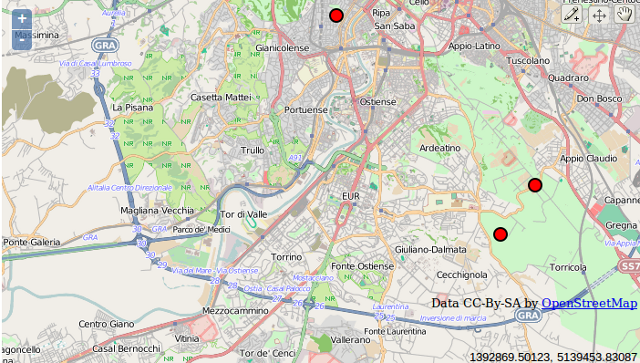

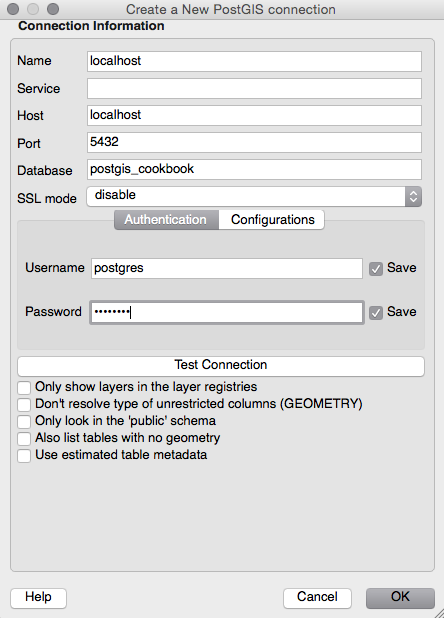

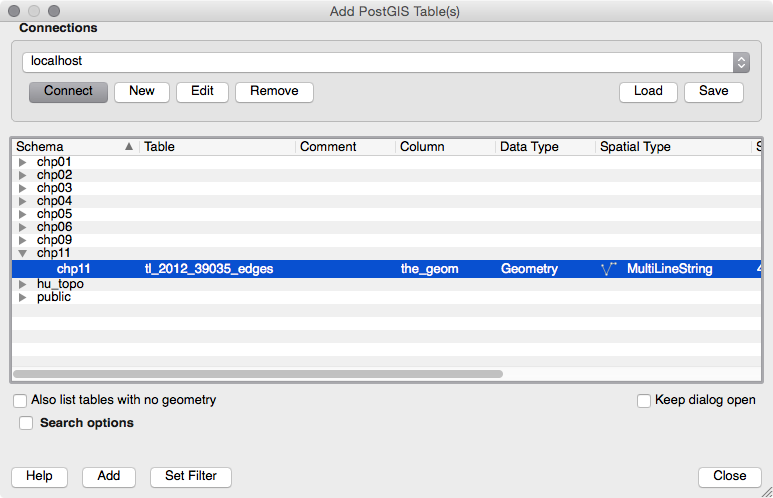

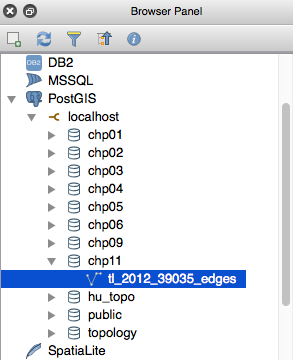

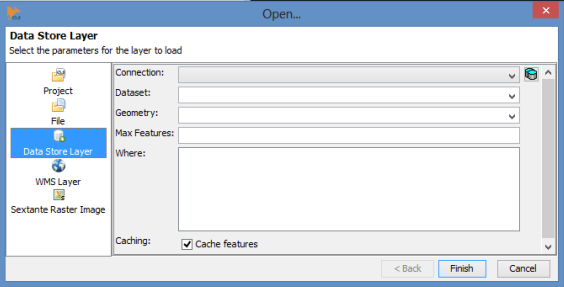

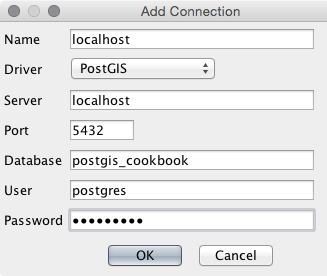

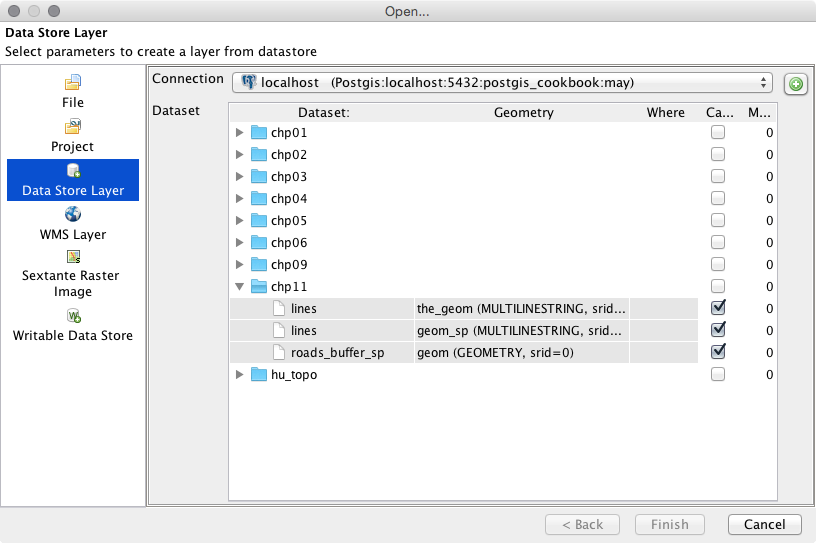

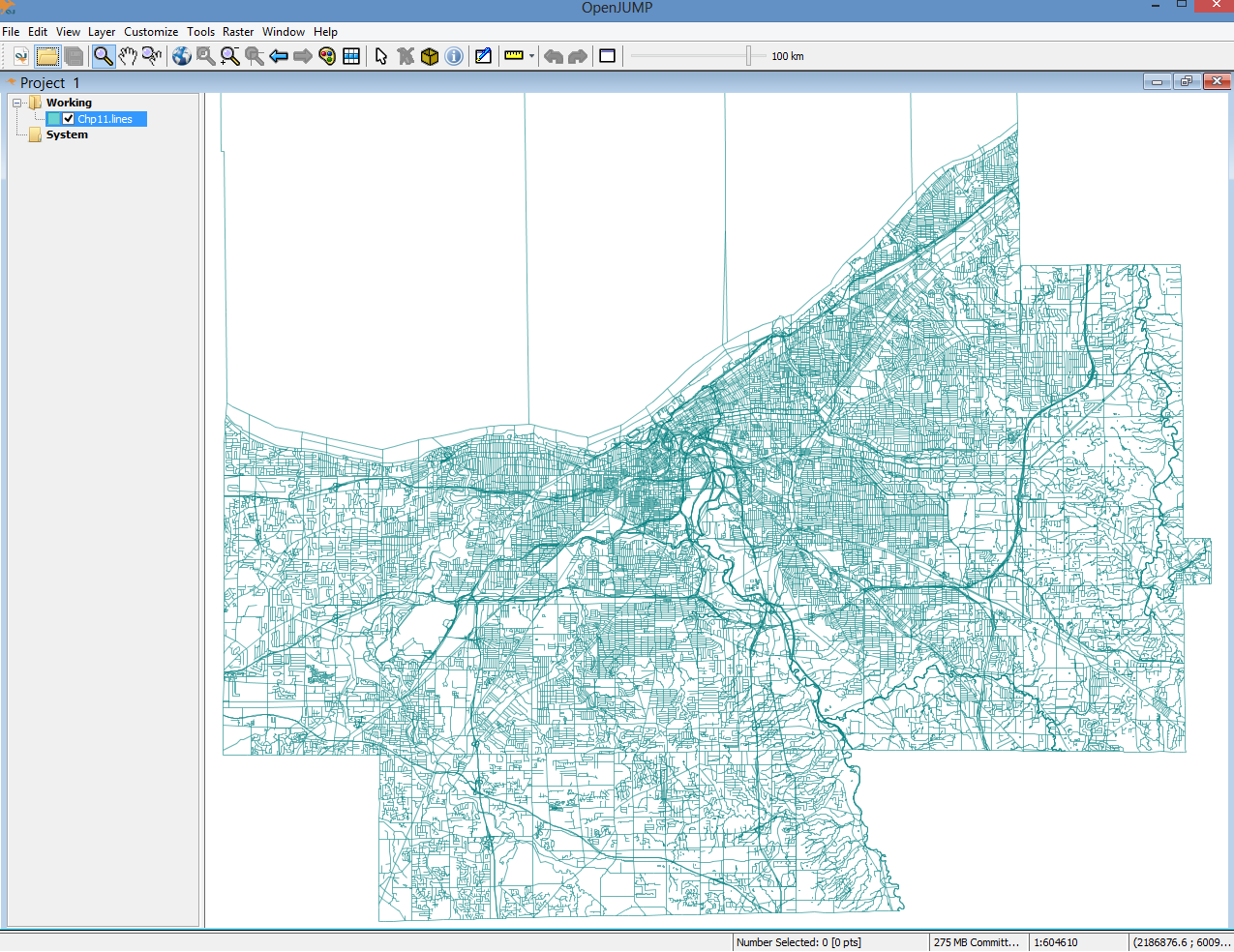

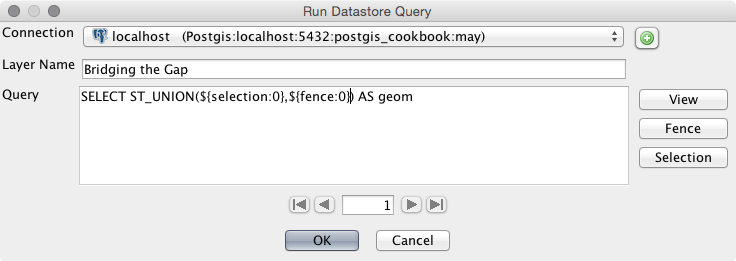

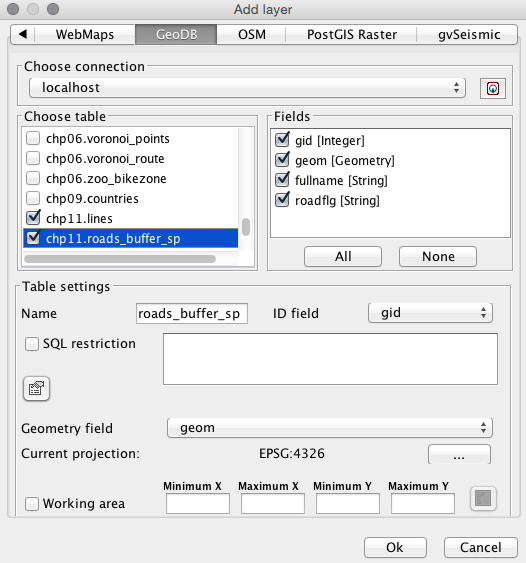

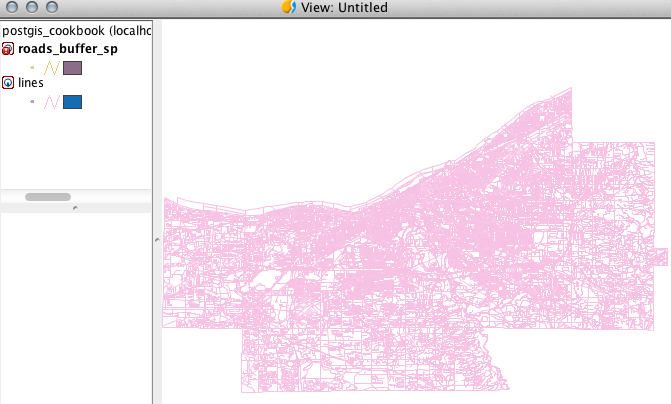

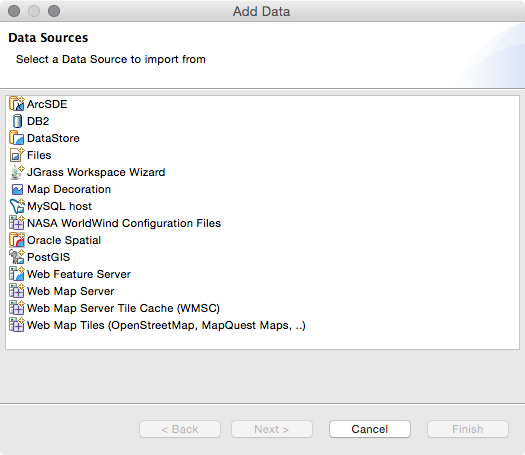

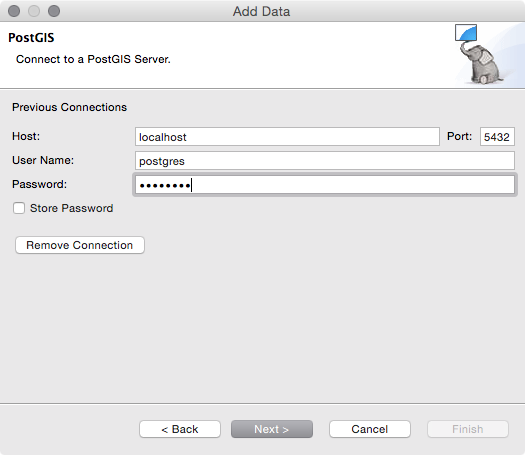

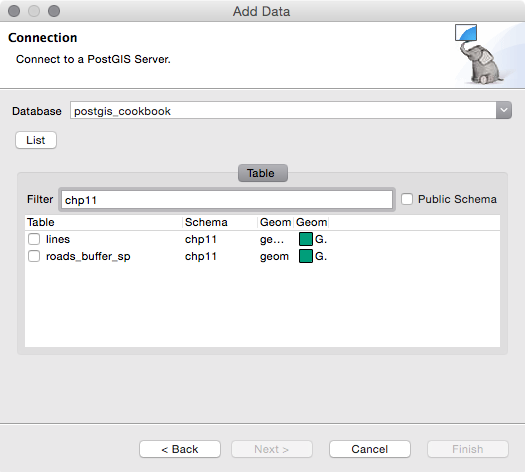

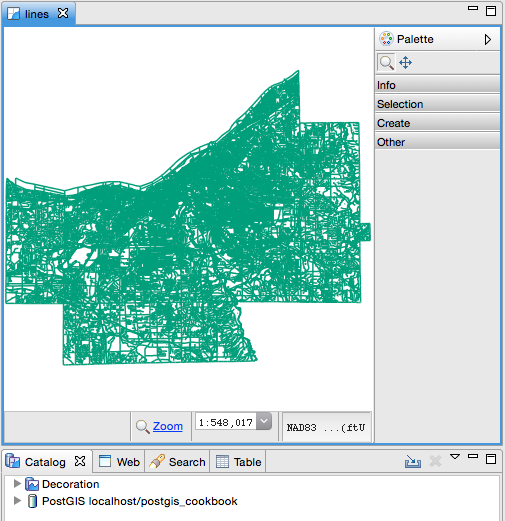

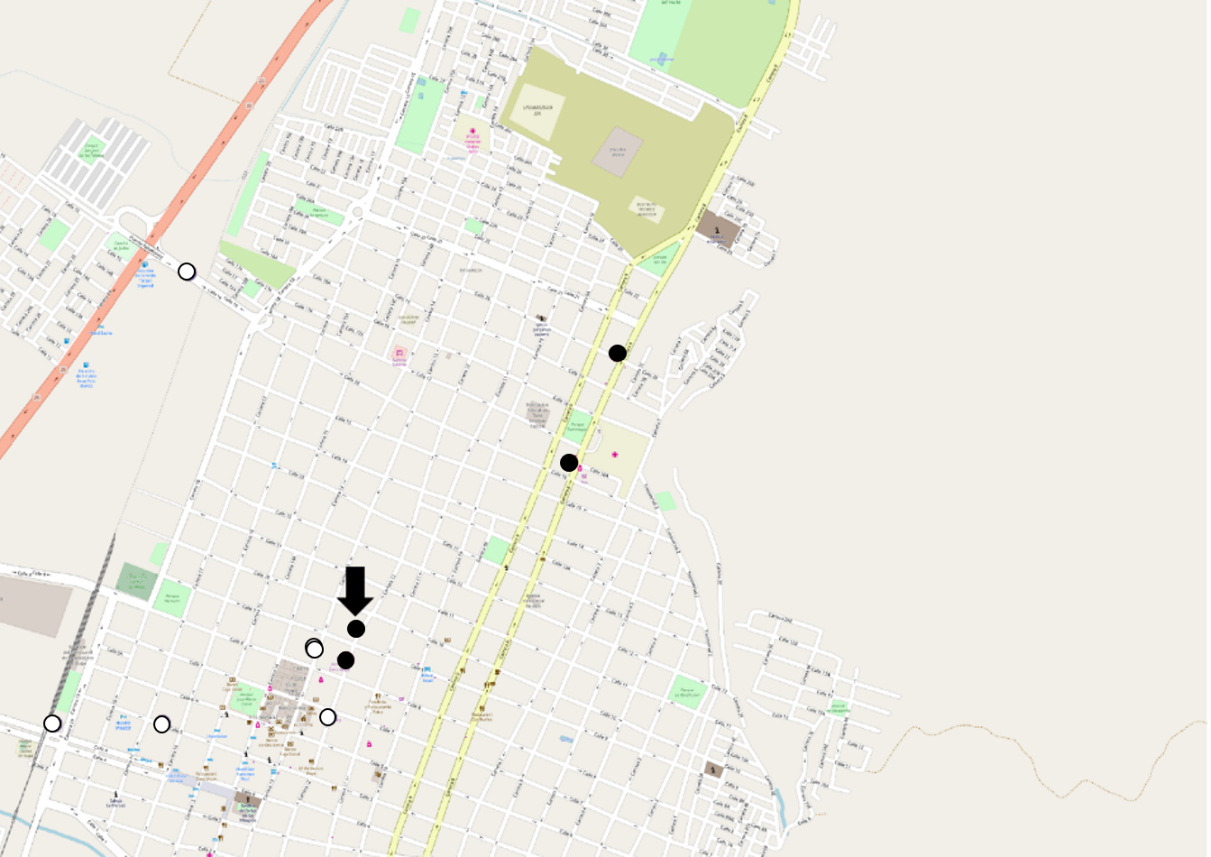

Now, open QGIS and try to add the new layer to the map. Navigate to Layer | Add Layer | Add PostGIS layers and provide the connection information, and then add the layer to the map as shown in the following screenshot:

The PostGIS command, shp2pgsql, allows the user to import a shapefile in the PostGIS database. Basically, it generates a PostgreSQL dump file that can be used to load data by running it from within PostgreSQL.

The SQL file will be generally composed of the following sections:

To get a complete list of the shp2pgsql command options and their meanings, just type the command name in the shell (or in the command prompt, if you are on Windows) and check the output.

There are GUI tools to manage data in and out of PostGIS, generally integrated into GIS desktop software such as QGIS. In the last chapter of this book, we will take a look at the most popular one.

In this recipe, you will use the popular ogr2ogr GDAL command for importing and exporting vector data from PostGIS.

Firstly, you will import a shapefile in PostGIS using the most significant options of the ogr2ogr command. Then, still using ogr2ogr, you will export the results of a spatial query performed in PostGIS to a couple of GDAL-supported vector formats.

The steps you need to follow to complete this recipe are as follows:

$ ogr2ogr -f PostgreSQL -sql "SELECT ISO2,

NAME AS country_name FROM wborders WHERE REGION=2" -nlt

MULTIPOLYGON PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me'

password='mypassword'" -nln africa_countries

-lco SCHEMA=chp01 -lco GEOMETRY_NAME=the_geom wborders.shp

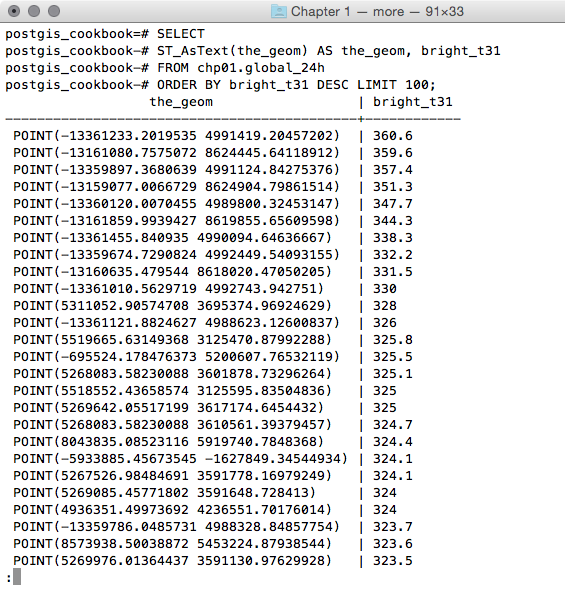

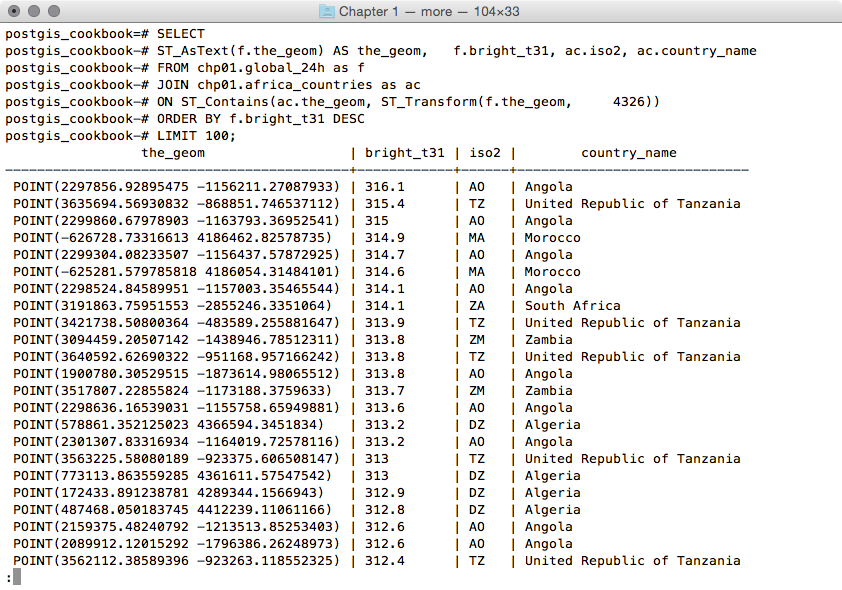

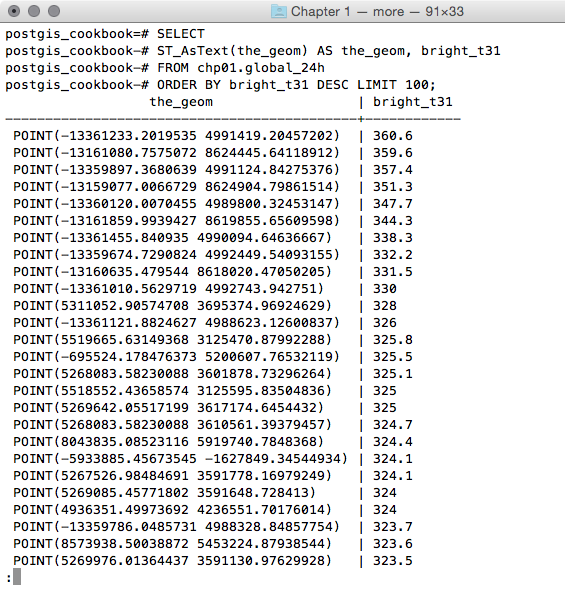

postgis_cookbook=# SELECTST_AsText(the_geom) AS the_geom, bright_t31

FROM chp01.global_24h

ORDER BY bright_t31 DESC LIMIT 100;

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

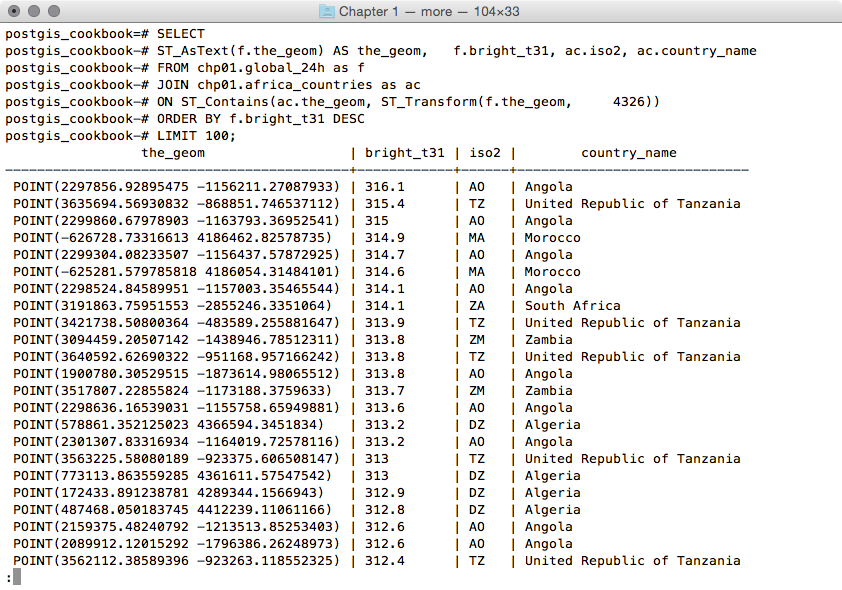

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT ST_AsText(f.the_geom)

AS the_geom, f.bright_t31, ac.iso2, ac.country_name

FROM chp01.global_24h as f

JOIN chp01.africa_countries as ac

ON ST_Contains(ac.the_geom, ST_Transform(f.the_geom, 4326))

ORDER BY f.bright_t31 DESCLIMIT 100;

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

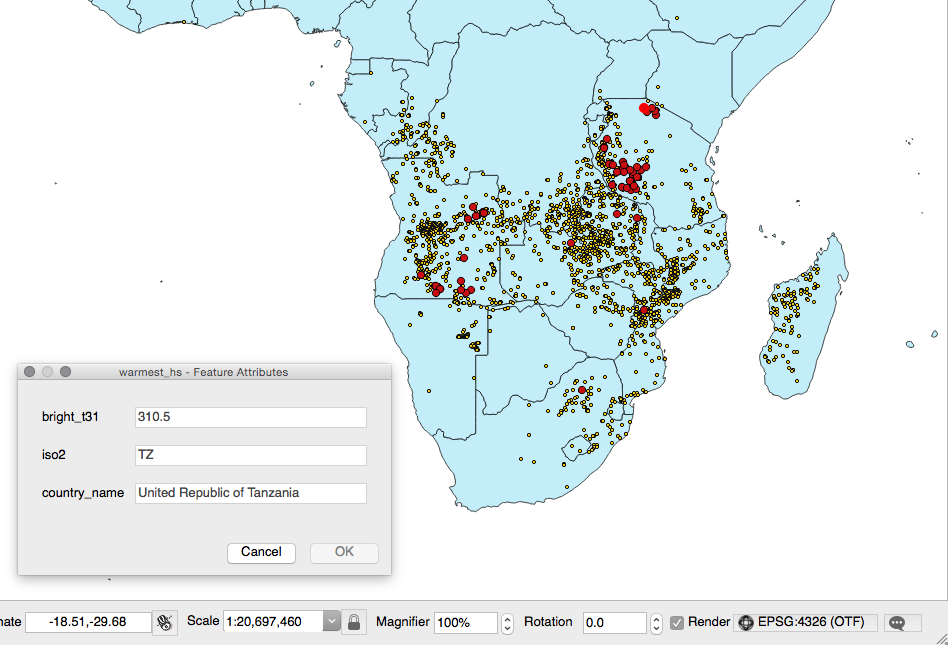

You will now export the result of this query to a vector format supported by GDAL, such as GeoJSON, in the WGS 84 spatial reference using ogr2ogr:

$ ogr2ogr -f GeoJSON -t_srs EPSG:4326 warmest_hs.geojson

PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me' password='mypassword'" -sql "

SELECT f.the_geom as the_geom, f.bright_t31,

ac.iso2, ac.country_name

FROM chp01.global_24h as f JOIN chp01.africa_countries as ac

ON ST_Contains(ac.the_geom, ST_Transform(f.the_geom, 4326))

ORDER BY f.bright_t31 DESC LIMIT 100"

$ ogr2ogr -t_srs EPSG:4326 -f CSV -lco GEOMETRY=AS_XY

-lco SEPARATOR=TAB warmest_hs.csv PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook'

user='me' password='mypassword'" -sql "

SELECT f.the_geom, f.bright_t31,

ac.iso2, ac.country_name

FROM chp01.global_24h as f JOIN chp01.africa_countries as ac

ON ST_Contains(ac.the_geom, ST_Transform(f.the_geom, 4326))

ORDER BY f.bright_t31 DESC LIMIT 100"

GDAL is an open source library that comes together with several command-line utilities, which let the user translate and process raster and vector geodatasets into a plethora of formats. In the case of vector datasets, there is a GDAL sublibrary for managing vector datasets named OGR (therefore, when talking about vector datasets in the context of GDAL, we can also use the expression OGR dataset).

When you are working with an OGR dataset, two of the most popular OGR commands are ogrinfo, which lists many kinds of information from an OGR dataset, and ogr2ogr, which converts the OGR dataset from one format to another.

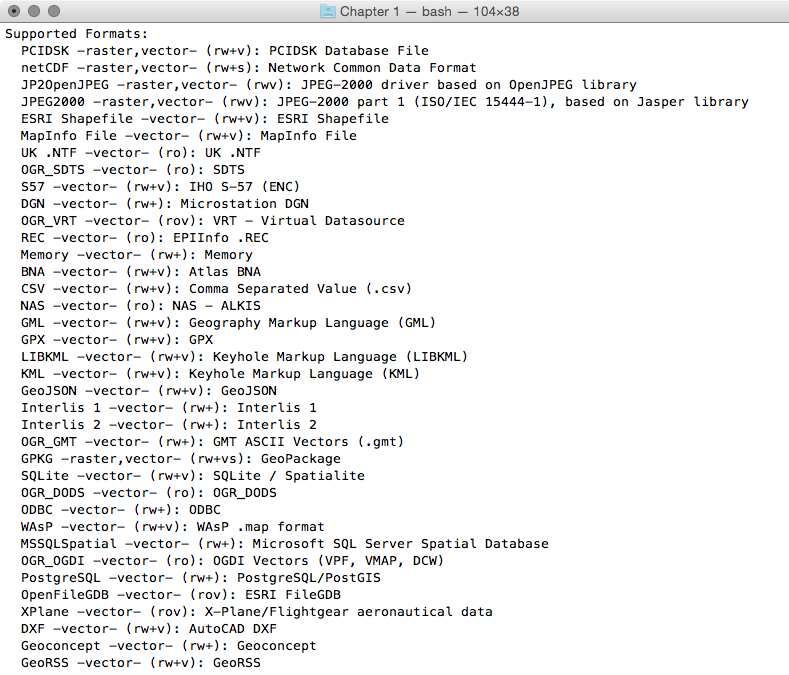

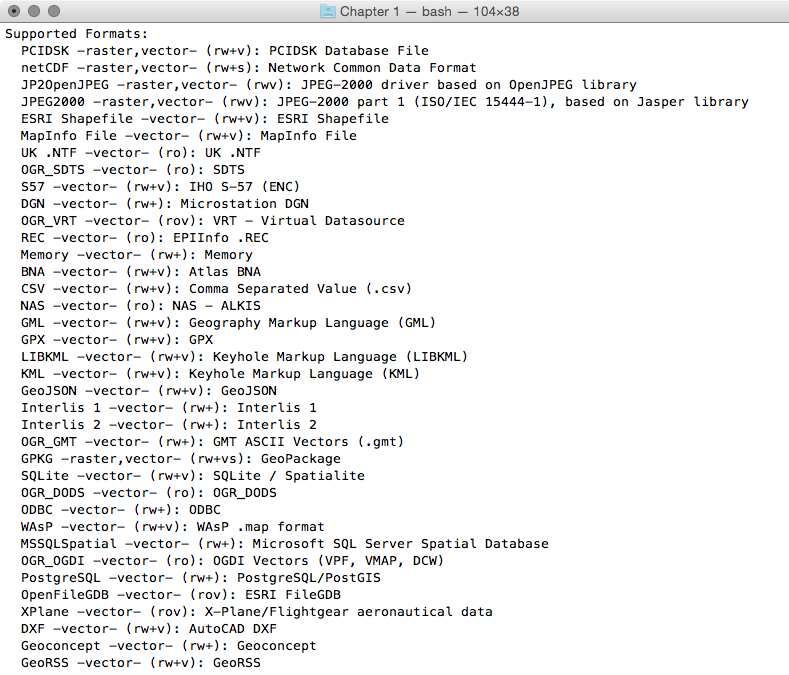

It is possible to retrieve a list of the supported OGR vector formats using the -formats option on any OGR commands, for example, with ogr2ogr:

$ ogr2ogr --formats

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

Note that some formats are read-only, while others are read/write.

PostGIS is one of the supported read/write OGR formats, so it is possible to use the OGR API or any OGR commands (such as ogrinfo and ogr2ogr) to manipulate its datasets.

The ogr2ogr command has many options and parameters; in this recipe, you have seen some of the most notable ones such as -f to define the output format, -t_srs to reproject/transform the dataset, and -sql to define an (eventually spatial) query in the input OGR dataset.

When using ogrinfo and ogr2ogr together with the desired option and parameters, you have to define the datasets. When specifying a PostGIS dataset, you need a connection string that is defined as follows:

PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me' password='mypassword'"

You can find more information about the ogrinfo and ogr2ogr commands on the GDAL website available at http://www.gdal.org.

If you need more information about the PostGIS driver, you should check its related documentation page available at http://www.gdal.org/drv_pg.html.

In many GIS workflows, there is a typical scenario where subsets of a PostGIS table must be deployed to external users in a filesystem format (most typically, shapefiles or a spatialite database). Often, there is also the reverse process, where datasets received from different users have to be uploaded to the PostGIS database.

In this recipe, we will simulate both of these data flows. You will first create the data flow for processing the shapefiles out of PostGIS, and then the reverse data flow for uploading the shapefiles.

You will do it using the power of bash scripting and the ogr2ogr command.

If you didn't follow all the other recipes, be sure to import the hotspots (Global_24h.csv) and the countries dataset (countries.shp) in PostGIS. The following is how to do it with ogr2ogr (you should import both the datasets in their original SRID, 4326, to make spatial operations faster):

$ ogr2ogr -f PostgreSQL PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook'

user='me' password='mypassword'" -lco SCHEMA=chp01 global_24h.vrt

-lco OVERWRITE=YES -lco GEOMETRY_NAME=the_geom -nln hotspots

$ ogr2ogr -f PostgreSQL -sql "SELECT ISO2, NAME AS country_name

FROM wborders" -nlt MULTIPOLYGON PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook'

user='me' password='mypassword'" -nln countries

-lco SCHEMA=chp01 -lco OVERWRITE=YES

-lco GEOMETRY_NAME=the_geom wborders.shp

The steps you need to follow to complete this recipe are as follows:

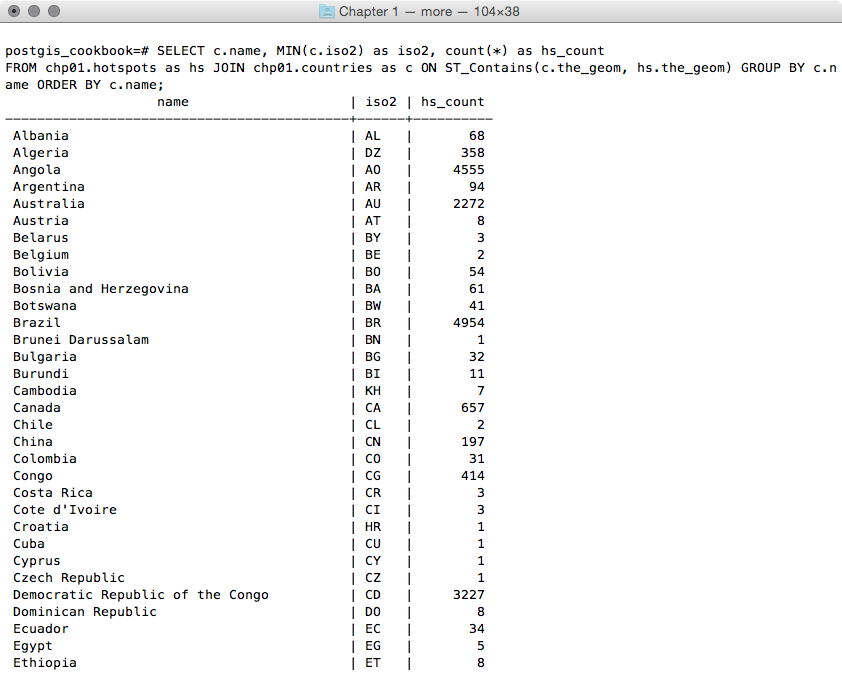

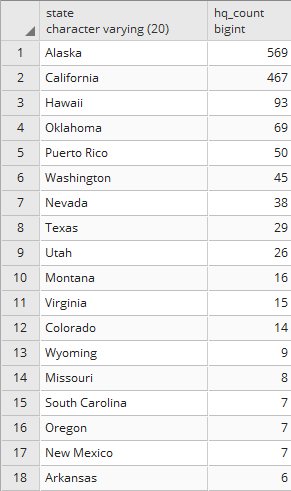

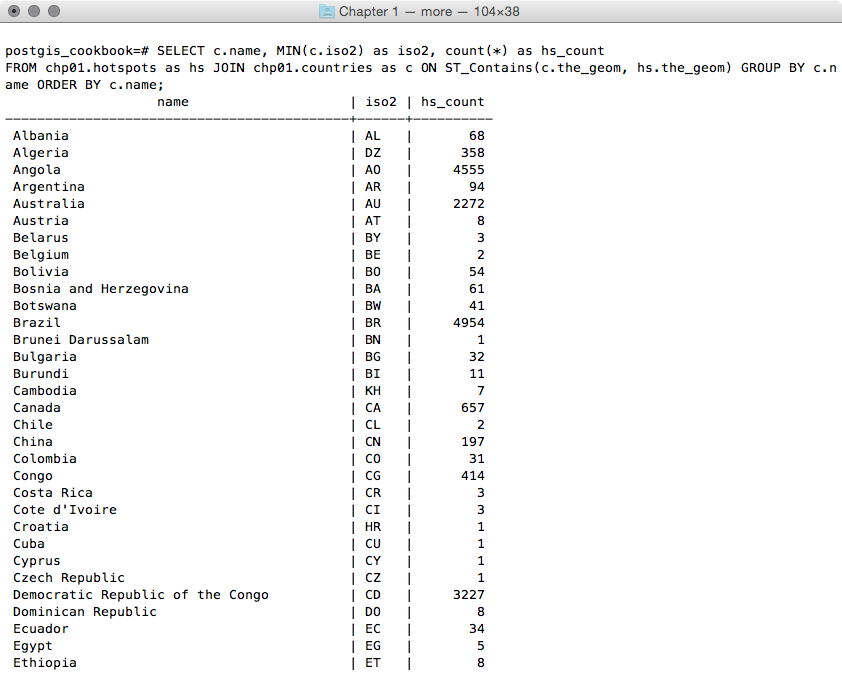

postgis_cookbook=> SELECT c.country_name, MIN(c.iso2)

as iso2, count(*) as hs_count FROM chp01.hotspots as hs

JOIN chp01.countries as c ON ST_Contains(c.the_geom, hs.the_geom)

GROUP BY c.country_name ORDER BY c.country_name;

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

$ ogr2ogr -f CSV hs_countries.csv

PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me' password='mypassword'"

-lco SCHEMA=chp01 -sql "SELECT c.country_name, MIN(c.iso2) as iso2,

count(*) as hs_count FROM chp01.hotspots as hs

JOIN chp01.countries as c ON ST_Contains(c.the_geom, hs.the_geom)

GROUP BY c.country_name ORDER BY c.country_name"

postgis_cookbook=> COPY (SELECT c.country_name, MIN(c.iso2) as iso2,

count(*) as hs_count FROM chp01.hotspots as hs

JOIN chp01.countries as c ON ST_Contains(c.the_geom, hs.the_geom)

GROUP BY c.country_name ORDER BY c.country_name)

TO '/tmp/hs_countries.csv' WITH CSV HEADER;

#!/bin/bash

while IFS="," read country iso2 hs_count

do

echo "Generating shapefile $iso2.shp for country

$country ($iso2) containing $hs_count features."

ogr2ogr out_shapefiles/$iso2.shp

PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me' password='mypassword'"

-lco SCHEMA=chp01 -sql "SELECT ST_Transform(hs.the_geom, 4326),

hs.acq_date, hs.acq_time, hs.bright_t31

FROM chp01.hotspots as hs JOIN chp01.countries as c

ON ST_Contains(c.the_geom, ST_Transform(hs.the_geom, 4326))

WHERE c.iso2 = '$iso2'" done < hs_countries.csv

chmod 775 export_shapefiles.sh

mkdir out_shapefiles

$ ./export_shapefiles.sh

Generating shapefile AL.shp for country

Albania (AL) containing 66 features.

Generating shapefile DZ.shp for country

Algeria (DZ) containing 361 features.

...

Generating shapefile ZM.shp for country

Zambia (ZM) containing 1575 features.

Generating shapefile ZW.shp for country

Zimbabwe (ZW) containing 179 features.

@echo off

for /f "tokens=1-3 delims=, skip=1" %%a in (hs_countries.csv) do (

echo "Generating shapefile %%b.shp for country %%a

(%%b) containing %%c features"

ogr2ogr .\out_shapefiles\%%b.shp

PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me' password='mypassword'"

-lco SCHEMA=chp01 -sql "SELECT ST_Transform(hs.the_geom, 4326),

hs.acq_date, hs.acq_time, hs.bright_t31

FROM chp01.hotspots as hs JOIN chp01.countries as c

ON ST_Contains(c.the_geom, ST_Transform(hs.the_geom, 4326))

WHERE c.iso2 = '%%b'"

)

>mkdir out_shapefiles

>export_shapefiles.bat

"Generating shapefile AL.shp for country

Albania (AL) containing 66 features"

"Generating shapefile DZ.shp for country

Algeria (DZ) containing 361 features"

...

"Generating shapefile ZW.shp for country

Zimbabwe (ZW) containing 179 features"

postgis_cookbook=# CREATE TABLE chp01.hs_uploaded

(

ogc_fid serial NOT NULL,

acq_date character varying(80),

acq_time character varying(80),

bright_t31 character varying(80),

iso2 character varying,

upload_datetime character varying,

shapefile character varying,

the_geom geometry(POINT, 4326),

CONSTRAINT hs_uploaded_pk PRIMARY KEY (ogc_fid)

);

$ brew install findutils

#!/bin/bash

for f in `find out_shapefiles -name \*.shp -printf "%f\n"`

do

echo "Importing shapefile $f to chp01.hs_uploaded PostGIS

table..." #, ${f%.*}"

ogr2ogr -append -update -f PostgreSQL

PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me'

password='mypassword'" out_shapefiles/$f

-nln chp01.hs_uploaded -sql "SELECT acq_date, acq_time,

bright_t31, '${f%.*}' AS iso2, '`date`' AS upload_datetime,

'out_shapefiles/$f' as shapefile FROM ${f%.*}"

done

$ chmod 775 import_shapefiles.sh

$ ./import_shapefiles.sh

Importing shapefile DO.shp to chp01.hs_uploaded PostGIS table

...

Importing shapefile ID.shp to chp01.hs_uploaded PostGIS table

...

Importing shapefile AR.shp to chp01.hs_uploaded PostGIS table

......

Now, go to step 14.

@echo off

for %%I in (out_shapefiles\*.shp*) do (

echo Importing shapefile %%~nxI to chp01.hs_uploaded

PostGIS table...

ogr2ogr -append -update -f PostgreSQL

PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me'

password='password'" out_shapefiles/%%~nxI

-nln chp01.hs_uploaded -sql "SELECT acq_date, acq_time,

bright_t31, '%%~nI' AS iso2, '%date%' AS upload_datetime,

'out_shapefiles/%%~nxI' as shapefile FROM %%~nI" )

>import_shapefiles.bat

Importing shapefile AL.shp to chp01.hs_uploaded PostGIS table...

Importing shapefile AO.shp to chp01.hs_uploaded PostGIS table...

Importing shapefile AR.shp to chp01.hs_uploaded PostGIS table......

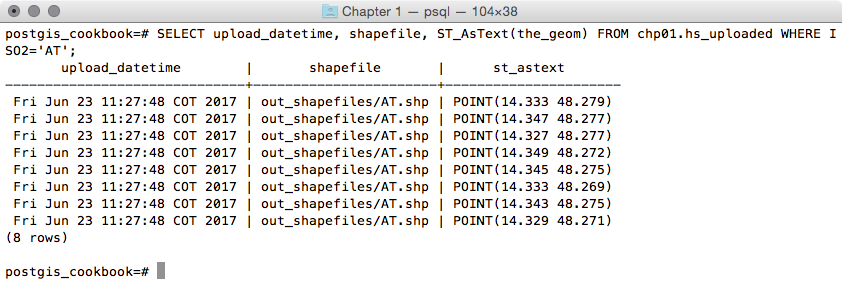

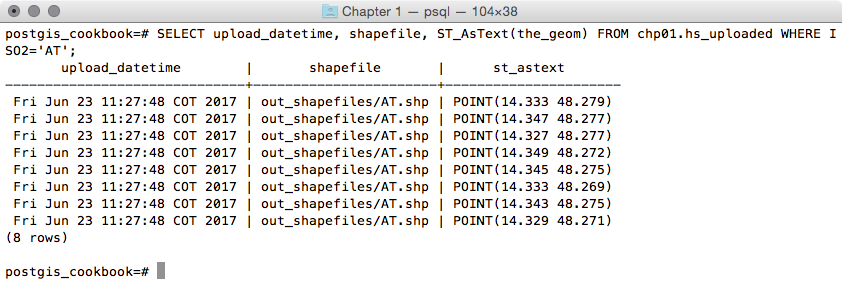

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT upload_datetime,

shapefile, ST_AsText(wkb_geometry)

FROM chp01.hs_uploaded WHERE ISO2='AT';

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

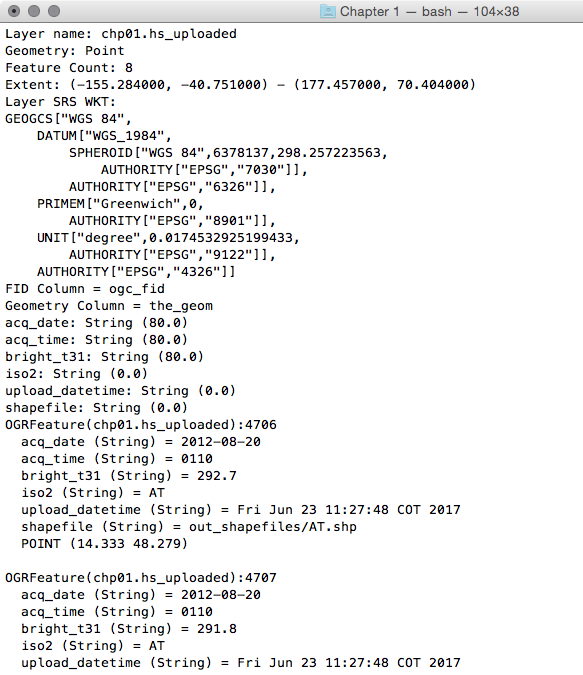

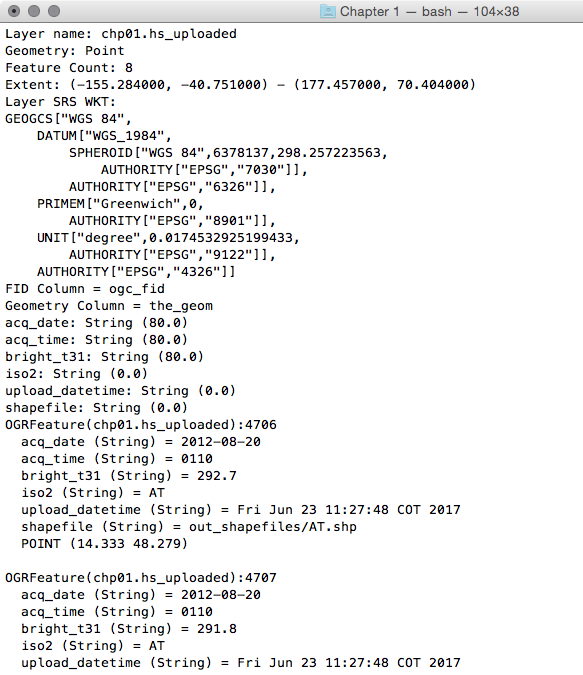

$ ogrinfo PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me'

password='mypassword'"

chp01.hs_uploaded -where "iso2='AT'"

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

You could implement both the data flows (processing shapefiles out from PostGIS, and then into it again) thanks to the power of the ogr2ogr GDAL command.

You have been using this command in different forms and with the most important input parameters in other recipes, so you should now have a good understanding of it.

Here, it is worth mentioning the way OGR lets you export the information related to the current datetime and the original shapefile name to the PostGIS table. Inside the import_shapefiles.sh (Linux, OS X) or the import_shapefiles.bat (Windows) scripts, the core is the line with the ogr2ogr command (here is the Linux version):

ogr2ogr -append -update -f PostgreSQL PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me' password='mypassword'" out_shapefiles/$f -nln chp01.hs_uploaded -sql "SELECT acq_date, acq_time, bright_t31, '${f%.*}' AS iso2, '`date`' AS upload_datetime, 'out_shapefiles/$f' as shapefile FROM ${f%.*}"

Thanks to the -sql option, you can specify the two additional fields, getting their values from the system date command and the filename that is being iterated from the script.

In this recipe, you will export a PostGIS table to a shapefile using the pgsql2shp command that is shipped with any PostGIS distribution.

The steps you need to follow to complete this recipe are as follows:

$ shp2pgsql -I -d -s 4326 -W LATIN1 -g the_geom countries.shp

chp01.countries > countries.sql

$ psql -U me -d postgis_cookbook -f countries.sql

$ ogr2ogr -f PostgreSQL PG:"dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me'

password='mypassword'"

-lco SCHEMA=chp01 countries.shp -nlt MULTIPOLYGON -lco OVERWRITE=YES

-lco GEOMETRY_NAME=the_geom

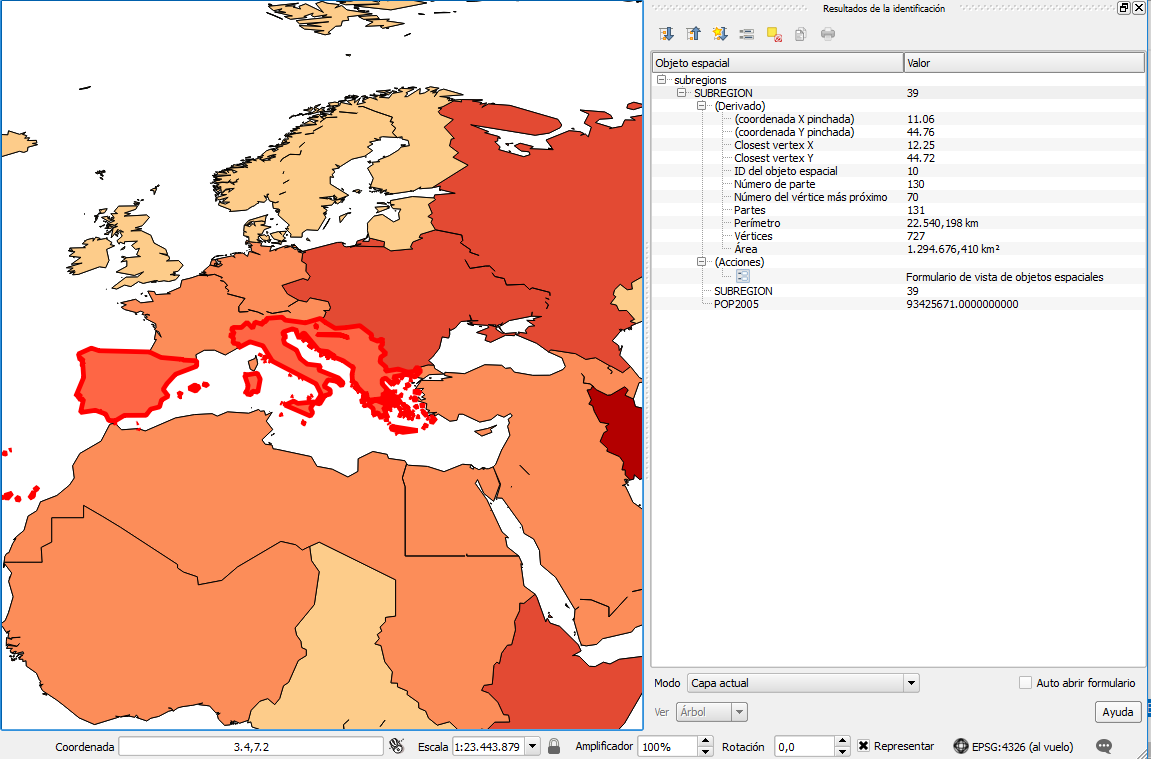

postgis_cookbook=> SELECT subregion,

ST_Union(the_geom) AS the_geom, SUM(pop2005) AS pop2005

FROM chp01.countries GROUP BY subregion;

$ pgsql2shp -f subregions.shp -h localhost -u me -P mypassword

postgis_cookbook "SELECT MIN(subregion) AS subregion,

ST_Union(the_geom) AS the_geom, SUM(pop2005) AS pop2005

FROM chp01.countries GROUP BY subregion;" Initializing... Done (postgis major version: 2). Output shape: Polygon Dumping: X [23 rows].

You have exported the results of a spatial query to a shapefile using the pgsql2shp PostGIS command. The spatial query you have used aggregates fields using the SUM PostgreSQL function for summing country populations in the same subregion, and the ST_Union PostGIS function to aggregate the corresponding geometries as a geometric union.

The pgsql2shp command allows you to export PostGIS tables and queries to shapefiles. The options you need to specify are quite similar to the ones you use to connect to PostgreSQL with psql. To get a full list of these options, just type pgsql2shp in your command prompt and read the output.

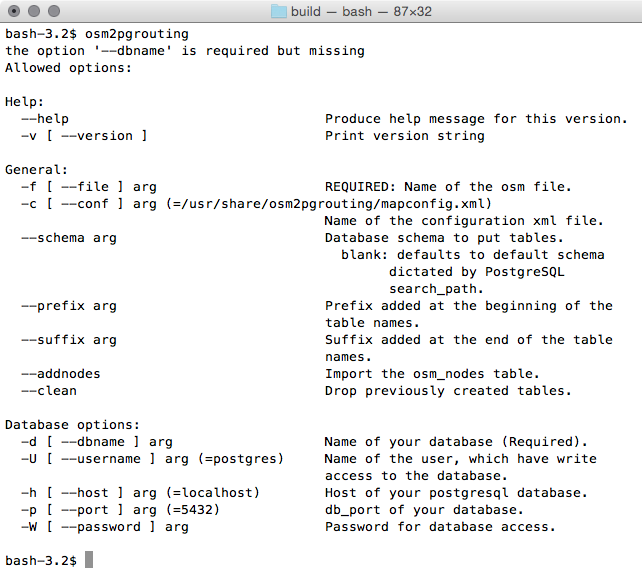

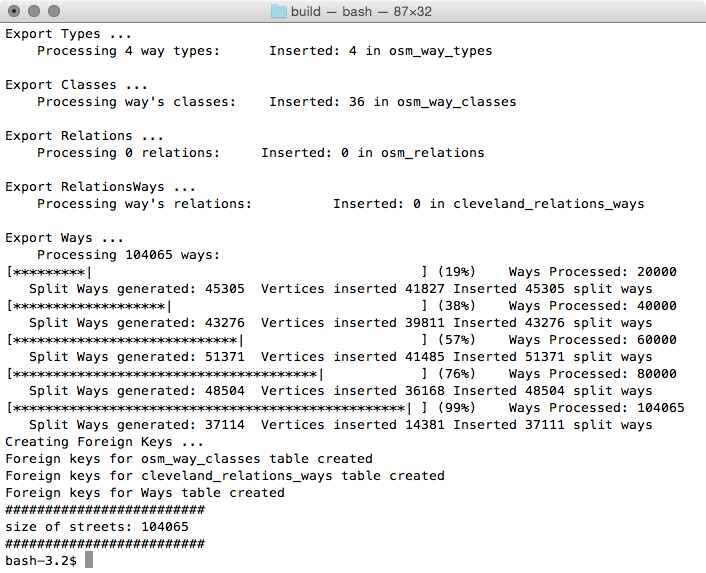

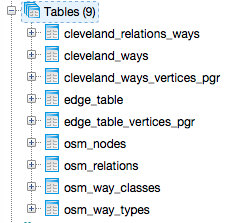

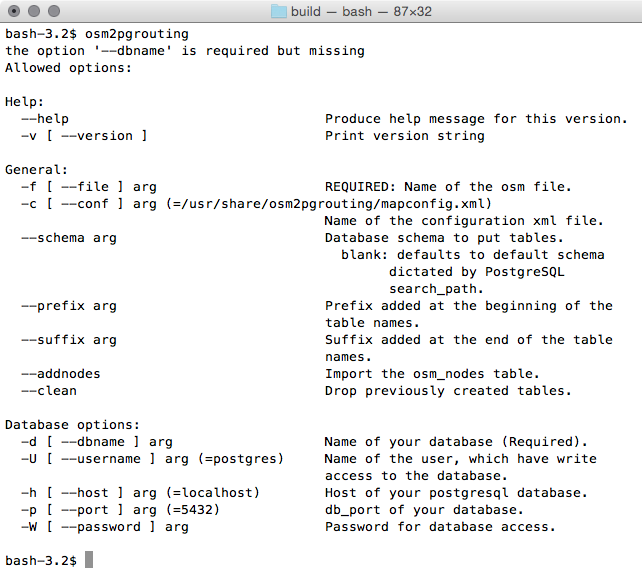

In this recipe, you will import OpenStreetMap (OSM) data to PostGIS using the osm2pgsql command.

You will first download a sample dataset from the OSM website, and then you will import it using the osm2pgsql command.

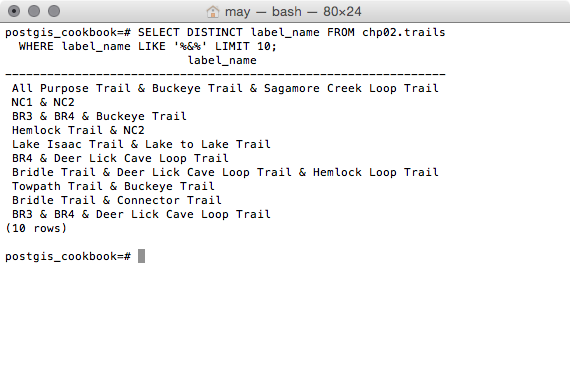

You will add the imported layers in GIS desktop software and generate a view to get subdatasets, using the hstore PostgreSQL additional module to extract features based on their tags.

We need the following in place before we can proceed with the steps required for the recipe:

$ sudo apt-get install osm2pgsql

$ osm2pgsqlosm2pgsql SVN version 0.80.0 (32bit id space)

postgres=# CREATE DATABASE rome OWNER me;

postgres=# \connect rome;

rome=# create extension postgis;

$ sudo apt-get update

$ sudo apt-get install postgresql-contrib-9.6

$ psql -U me -d romerome=# CREATE EXTENSION hstore;

The steps you need to follow to complete this recipe are as follows:

$ osm2pgsql -d rome -U me --hstore map.osm

osm2pgsql SVN version 0.80.0 (32bit id space)Using projection

SRS 900913 (Spherical Mercator)Setting up table:

planet_osm_point...All indexes on planet_osm_polygon created

in 1sCompleted planet_osm_polygonOsm2pgsql took 3s overall

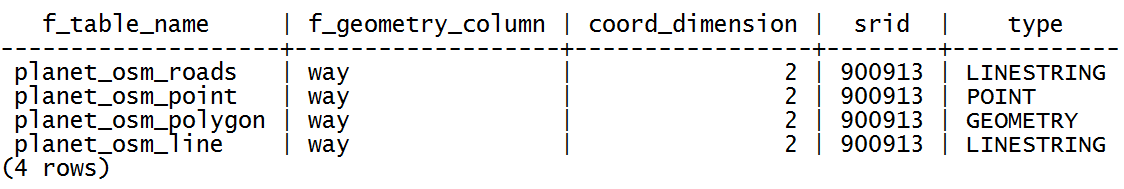

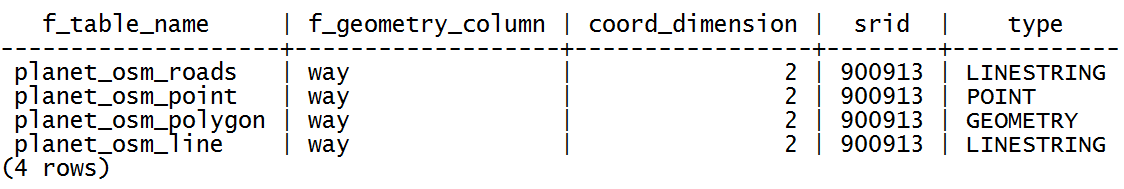

rome=# SELECT f_table_name, f_geometry_column,

coord_dimension, srid, type FROM geometry_columns;

The output of the preceding command is shown here:

rome=# CREATE VIEW rome_trees AS SELECT way, tags

FROM planet_osm_polygon WHERE (tags -> 'landcover') = 'trees';

OpenStreetMap is a popular collaborative project for creating a free map of the world. Every user participating in the project can edit data; at the same time, it is possible for everyone to download those datasets in .osm datafiles (an XML format) under the terms of the Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL) at the time of writing.

The osm2pgsql command is a command-line tool that can import .osm datafiles (eventually zipped) to the PostGIS database. To use the command, it is enough to give the PostgreSQL connection parameters and the .osm file to import.

It is possible to import only features that have certain tags in the spatial database, as defined in the default.style configuration file. You can decide to comment in or out the OSM tagged features that you would like to import, or not, from this file. The command by default exports all the nodes and ways to linestring, point, and geometry PostGIS geometries.

It is highly recommended to enable hstore support in the PostgreSQL database and use the -hstore option of osm2pgsql when importing the data. Having enabled this support, the OSM tags for each feature will be stored in a hstore PostgreSQL data type, which is optimized for storing (and retrieving) sets of key/values pairs in a single field. This way, it will be possible to query the database as follows:

SELECT way, tags FROM planet_osm_polygon WHERE (tags -> 'landcover') = 'trees';

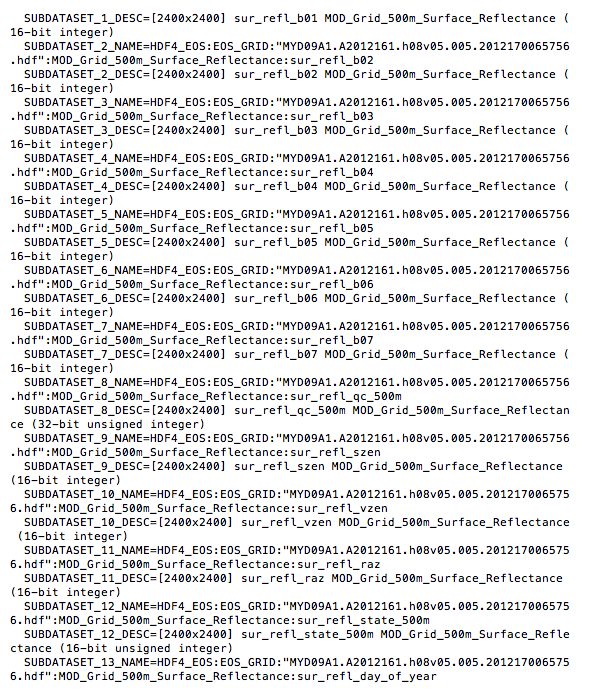

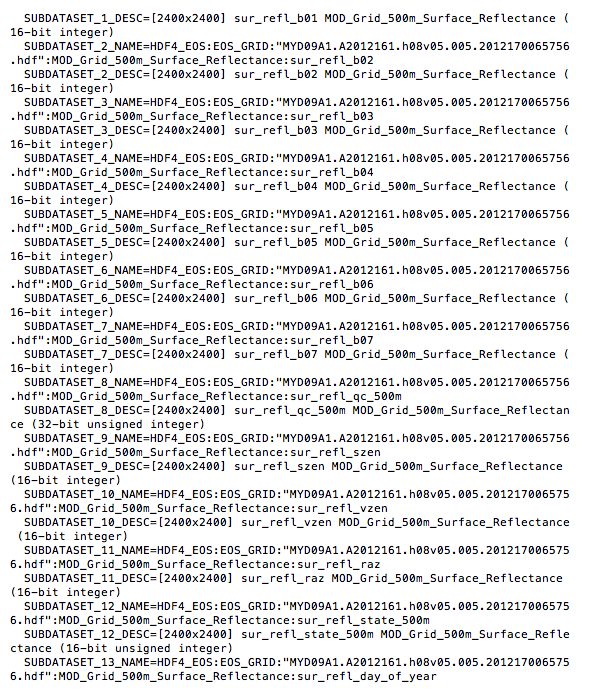

PostGIS 2.0 now has full support for raster datasets, and it is possible to import raster datasets using the raster2pgsql command.

In this recipe, you will import a raster file to PostGIS using the raster2pgsql command. This command, included in any PostGIS distribution from version 2.0 onward, is able to generate an SQL dump to be loaded in PostGIS for any GDAL raster-supported format (in the same fashion that the shp2pgsql command does for shapefiles).

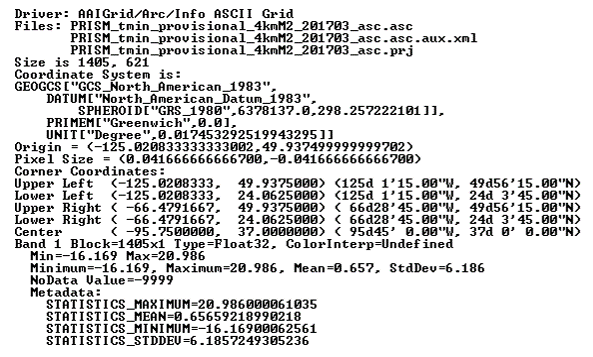

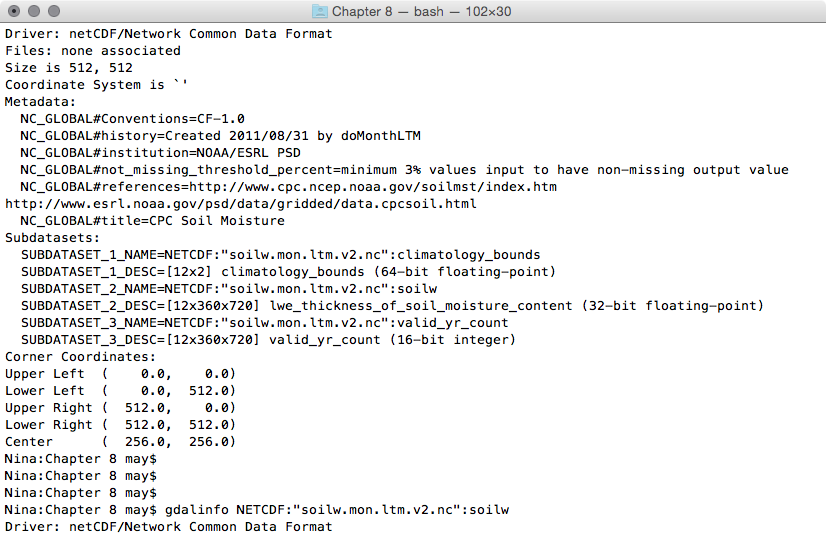

After loading the raster to PostGIS, you will inspect it both with SQL commands (analyzing the raster metadata information contained in the database), and with the gdalinfo command-line utility (to understand the way the input raster2pgsql parameters have been reflected in the PostGIS import process).

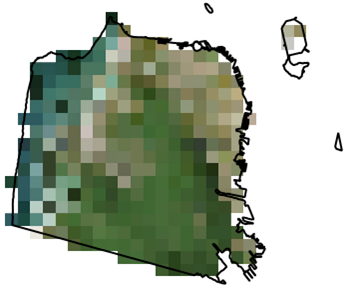

You will finally open the raster in a desktop GIS and try a basic spatial query, mixing vector and raster tables.

We need the following in place before we can proceed with the steps required for the recipe:

$ shp2pgsql -I -d -s 4326 -W LATIN1 -g the_geom countries.shp

chp01.countries > countries.sql

$ psql -U me -d postgis_cookbook -f countries.sql

The steps you need to follow to complete this recipe are as follows:

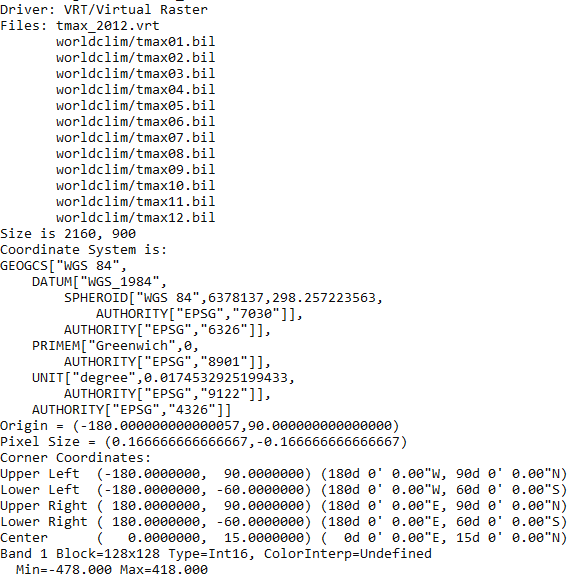

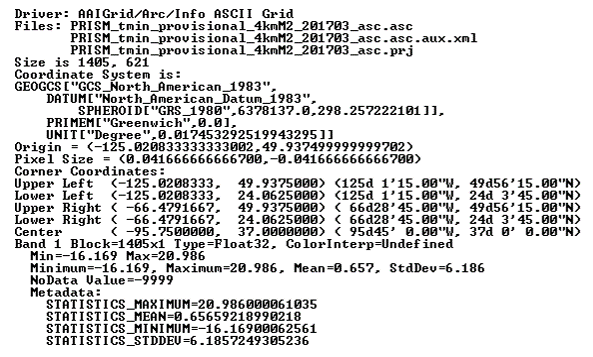

$ gdalinfo worldclim/tmax09.bil

Driver: EHdr/ESRI .hdr Labelled

Files: worldclim/tmax9.bil

worldclim/tmax9.hdr

Size is 2160, 900

Coordinate System is:

GEOGCS[""WGS 84"",

DATUM[""WGS_1984"",

SPHEROID[""WGS 84"",6378137,298.257223563,

AUTHORITY[""EPSG"",""7030""]],

TOWGS84[0,0,0,0,0,0,0],

AUTHORITY[""EPSG"",""6326""]],

PRIMEM[""Greenwich"",0,

AUTHORITY[""EPSG"",""8901""]],

UNIT[""degree"",0.0174532925199433,

AUTHORITY[""EPSG"",""9108""]],

AUTHORITY[""EPSG"",""4326""]]

Origin = (-180.000000000000057,90.000000000000000)

Pixel Size = (0.166666666666667,-0.166666666666667)

Corner Coordinates:

Upper Left (-180.0000000, 90.0000000) (180d 0'' 0.00""W, 90d

0'' 0.00""N)

Lower Left (-180.0000000, -60.0000000) (180d 0'' 0.00""W, 60d

0'' 0.00""S)

Upper Right ( 180.0000000, 90.0000000) (180d 0'' 0.00""E, 90d

0'' 0.00""N)

Lower Right ( 180.0000000, -60.0000000) (180d 0'' 0.00""E, 60d

0'' 0.00""S)

Center ( 0.0000000, 15.0000000) ( 0d 0'' 0.00""E, 15d

0'' 0.00""N)

Band 1 Block=2160x1 Type=Int16, ColorInterp=Undefined

Min=-153.000 Max=441.000

NoData Value=-9999

$ raster2pgsql -I -C -F -t 100x100 -s 4326

worldclim/tmax01.bil chp01.tmax01 > tmax01.sql

$ psql -d postgis_cookbook -U me -f tmax01.sql

If you are in Linux, you may pipe the two commands in a unique line:

$ raster2pgsql -I -C -M -F -t 100x100 worldclim/tmax01.bil

chp01.tmax01 | psql -d postgis_cookbook -U me -f tmax01.sql

$ pg_dump -t chp01.tmax01 --schema-only -U me postgis_cookbook

...

CREATE TABLE tmax01 (

rid integer NOT NULL,

rast public.raster,

filename text,

CONSTRAINT enforce_height_rast CHECK (

(public.st_height(rast) = 100)

),

CONSTRAINT enforce_max_extent_rast CHECK (public.st_coveredby

(public.st_convexhull(rast), ''0103...''::public.geometry)

),

CONSTRAINT enforce_nodata_values_rast CHECK (

((public._raster_constraint_nodata_values(rast)

)::numeric(16,10)[] = ''{0}''::numeric(16,10)[])

),

CONSTRAINT enforce_num_bands_rast CHECK (

(public.st_numbands(rast) = 1)

),

CONSTRAINT enforce_out_db_rast CHECK (

(public._raster_constraint_out_db(rast) = ''{f}''::boolean[])

),

CONSTRAINT enforce_pixel_types_rast CHECK (

(public._raster_constraint_pixel_types(rast) =

''{16BUI}''::text[])

),

CONSTRAINT enforce_same_alignment_rast CHECK (

(public.st_samealignment(rast, ''01000...''::public.raster)

),

CONSTRAINT enforce_scalex_rast CHECK (

((public.st_scalex(rast))::numeric(16,10) =

0.166666666666667::numeric(16,10))

),

CONSTRAINT enforce_scaley_rast CHECK (

((public.st_scaley(rast))::numeric(16,10) =

(-0.166666666666667)::numeric(16,10))

),

CONSTRAINT enforce_srid_rast CHECK ((public.st_srid(rast) = 0)),

CONSTRAINT enforce_width_rast CHECK ((public.st_width(rast) = 100))

);

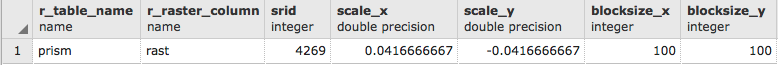

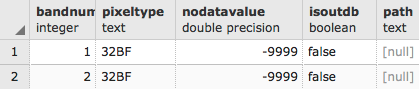

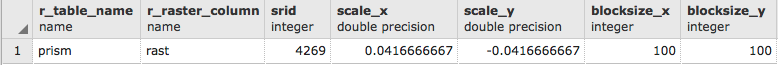

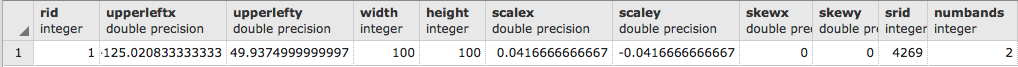

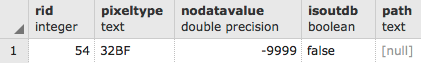

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT * FROM raster_columns;

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT count(*) FROM chp01.tmax01;

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

count

-------

198

(1 row)

gdalinfo PG":host=localhost port=5432 dbname=postgis_cookbook

user=me password=mypassword schema='chp01' table='tmax01'"

gdalinfo PG":host=localhost port=5432 dbname=postgis_cookbook

user=me password=mypassword schema='chp01' table='tmax01' mode=2"

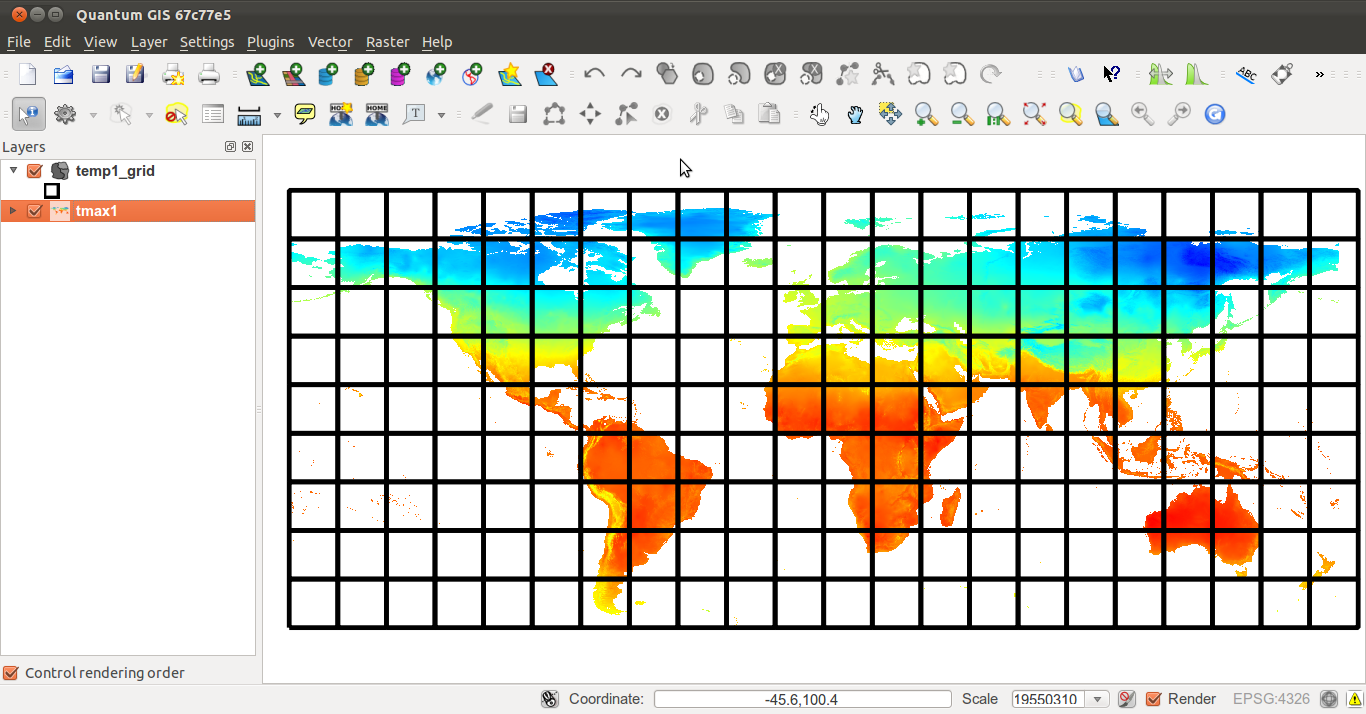

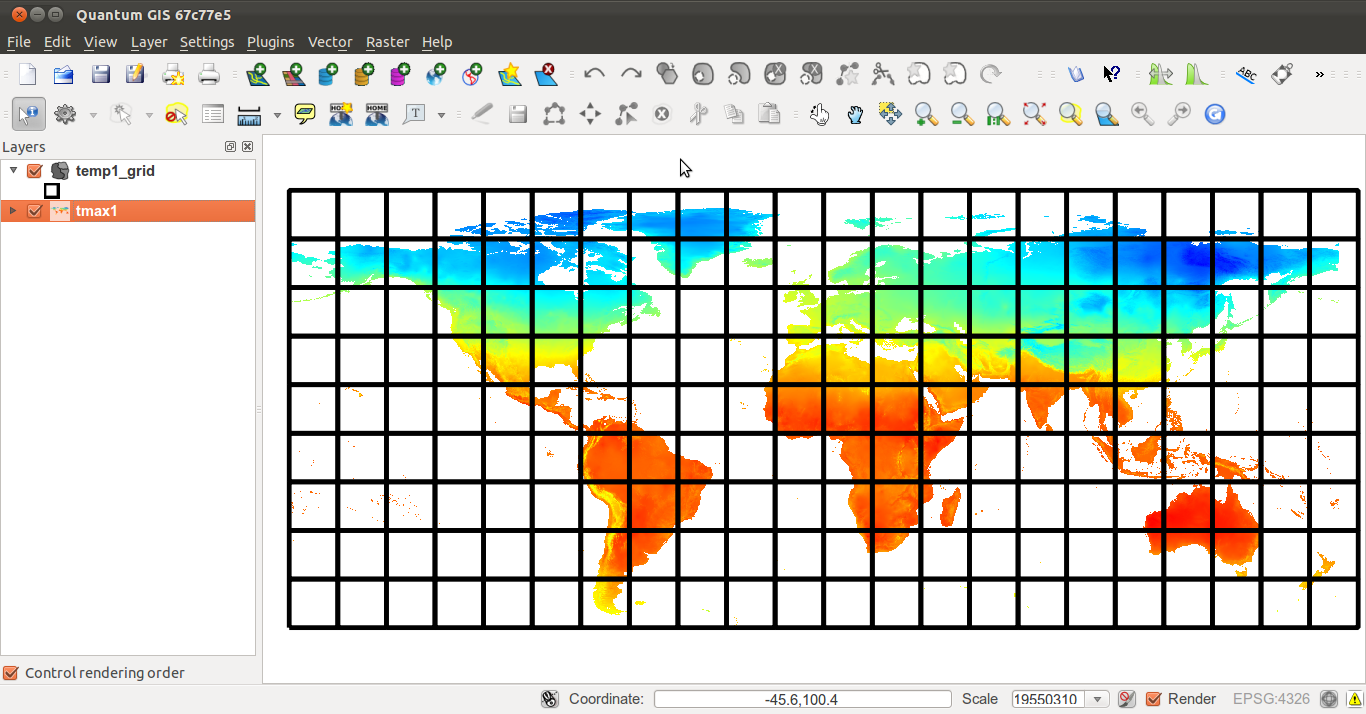

$ ogr2ogr temp_grid.shp PG:"host=localhost port=5432

dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me' password='mypassword'"

-sql "SELECT rid, filename, ST_Envelope(rast) as the_geom

FROM chp01.tmax01"

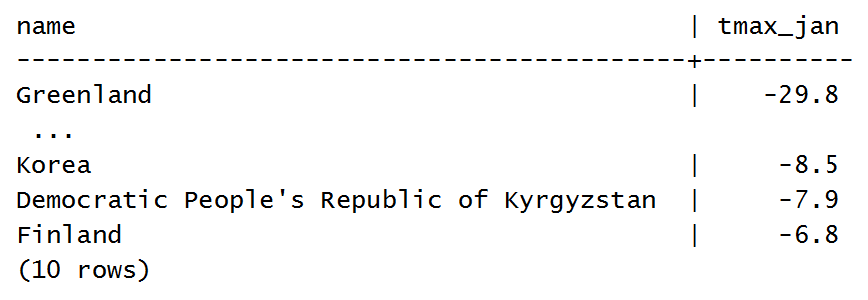

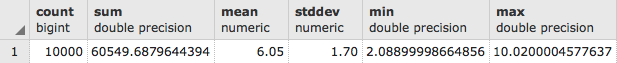

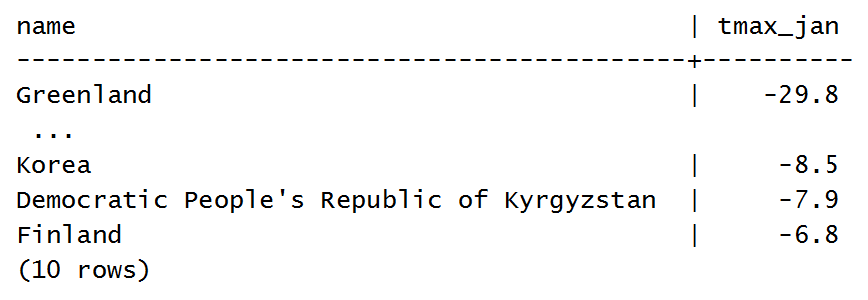

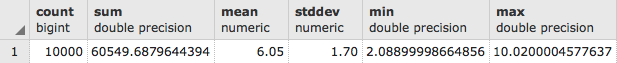

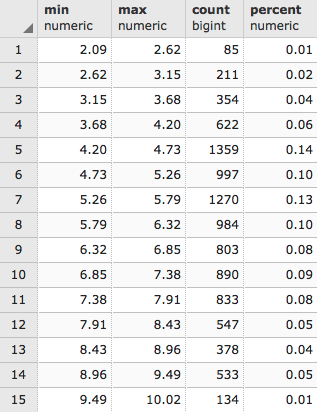

SELECT * FROM (

SELECT c.name, ST_Value(t.rast,

ST_Centroid(c.the_geom))/10 as tmax_jan FROM chp01.tmax01 AS t

JOIN chp01.countries AS c

ON ST_Intersects(t.rast, ST_Centroid(c.the_geom))

) AS foo

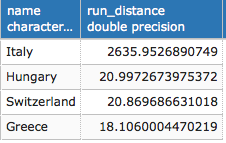

ORDER BY tmax_jan LIMIT 10;

The output is as follows:

The raster2pgsql command is able to load any raster formats supported by GDAL in PostGIS. You can have a format list supported by your GDAL installation by typing the following command:

$ gdalinfo --formats

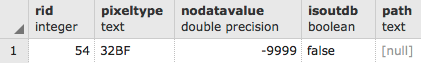

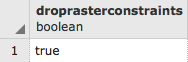

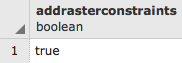

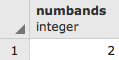

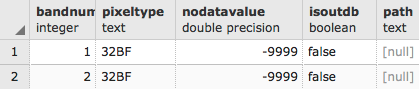

In this recipe, you have been importing one raster file using some of the most common raster2pgsql options:

$ raster2pgsql -I -C -F -t 100x100 -s 4326 worldclim/tmax01.bil chp01.tmax01 > tmax01.sql

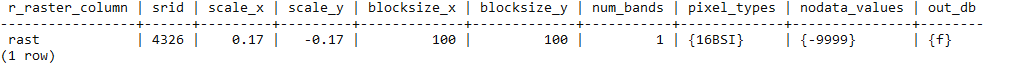

The -I option creates a GIST spatial index for the raster column. The -C option will create the standard set of constraints after the rasters have been loaded. The -F option will add a column with the filename of the raster that has been loaded. This is useful when you are appending many raster files to the same PostGIS raster table. The -s option sets the raster's SRID.

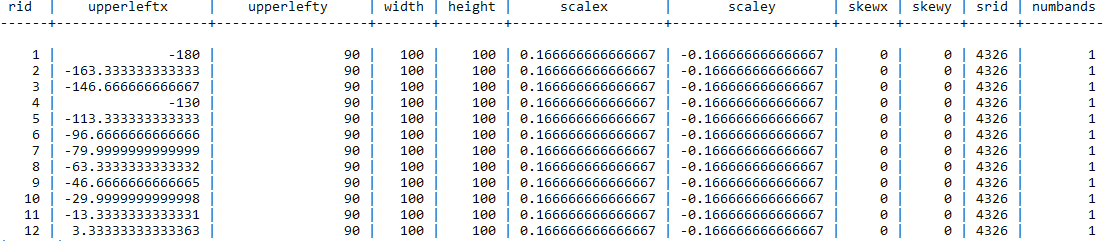

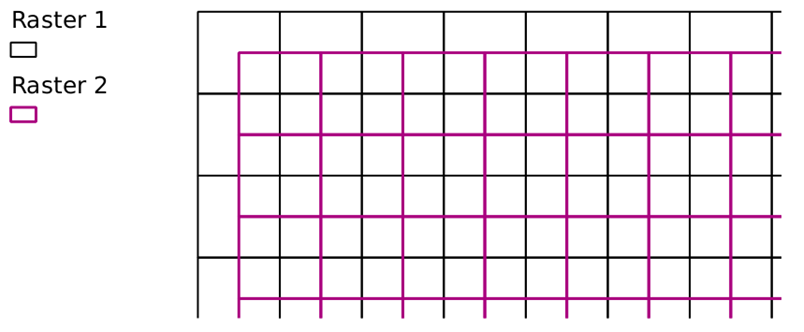

If you decide to include the -t option, then you will cut the original raster into tiles, each inserted as a single row in the raster table. In this case, you decided to cut the raster into 100 x 100 tiles, resulting in 198 table rows in the raster table.

Another important option is -R, which will register the raster as out-of-db; in such a case, only the metadata will be inserted in the database, while the raster will be out of the database.

The raster table contains an identifier for each row, the raster itself (eventually one of its tiles, if using the -t option), and eventually the original filename, if you used the -F option, as in this case.

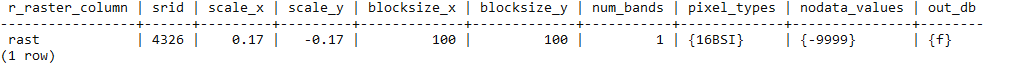

You can analyze the PostGIS raster using SQL commands or the gdalinfo command. Using SQL, you can query the raster_columns view to get the most significant raster metadata (spatial reference, band number, scale, block size, and so on).

With gdalinfo, you can access the same information, using a connection string with the following syntax:

gdalinfo PG":host=localhost port=5432 dbname=postgis_cookbook user=me password=mypassword schema='chp01' table='tmax01' mode=2"

The mode parameter is not influential if you loaded the whole raster as a single block (for example, if you did not specify the -t option). But, as in the use case of this recipe, if you split it into tiles, gdalinfo will see each tile as a single subdataset with the default behavior (mode=1). If you want GDAL to consider the raster table as a unique raster dataset, you have to specify the mode option and explicitly set it to 2.

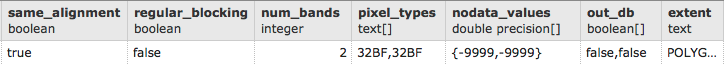

This recipe will guide you through the importing of multiple rasters at a time.

You will first import some different single band rasters to a unique single band raster table using the raster2pgsql command.

Then, you will try an alternative approach, merging the original single band rasters in a virtual raster, with one band for each of the original rasters, and then load the multiband raster to a raster table. To accomplish this, you will use the GDAL gdalbuildvrt command and then load the data to PostGIS with raster2pgsql.

Be sure to have all the original raster datasets you have been using for the previous recipe.

The steps you need to follow to complete this recipe are as follows:

$ raster2pgsql -d -I -C -M -F -t 100x100 -s 4326

worldclim/tmax*.bil chp01.tmax_2012 > tmax_2012.sql

$ psql -d postgis_cookbook -U me -f tmax_2012.sql

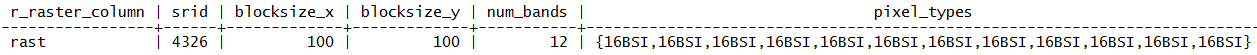

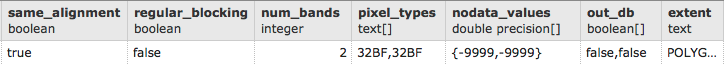

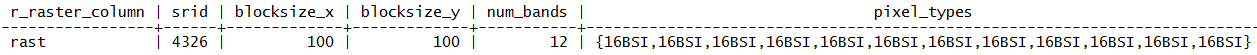

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT r_raster_column, srid,

ROUND(scale_x::numeric, 2) AS scale_x,

ROUND(scale_y::numeric, 2) AS scale_y, blocksize_x,

blocksize_y, num_bands, pixel_types, nodata_values, out_db

FROM raster_columns where r_table_schema='chp01'

AND r_table_name ='tmax_2012';

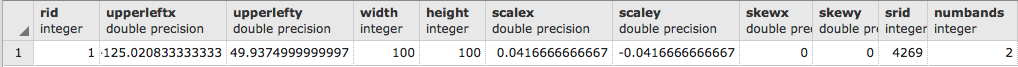

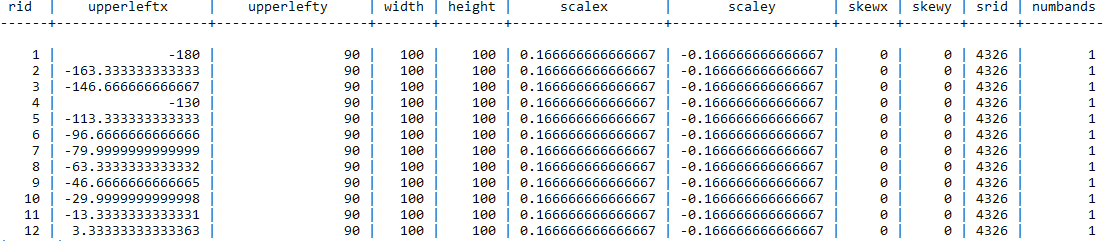

SELECT rid, (foo.md).*

FROM (SELECT rid, ST_MetaData(rast) As md

FROM chp01.tmax_2012) As foo;

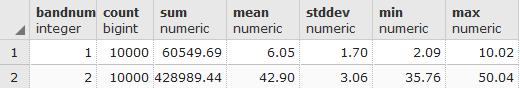

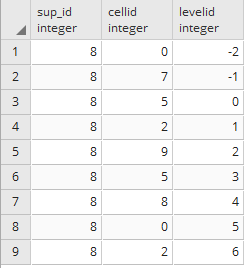

The output of the preceding command is as shown here:

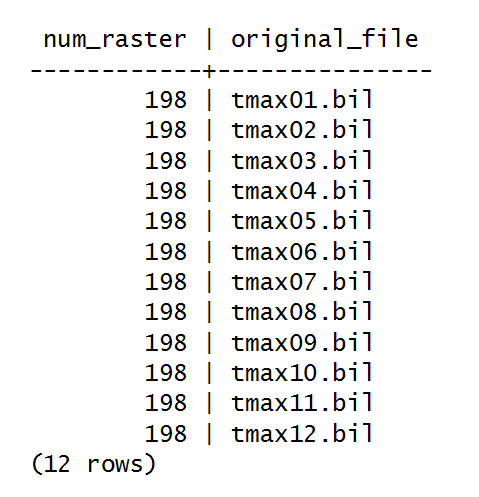

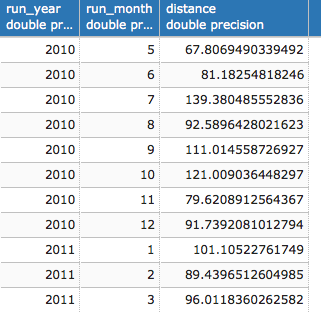

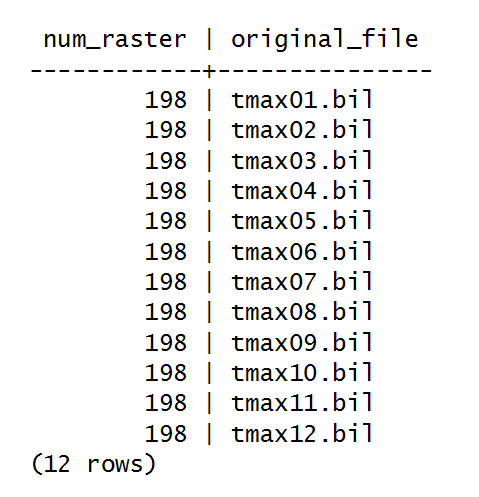

If you now query the table, you would be able to derive the month for each raster row only from the original_file column. In the table, you have imported 198 distinct records (rasters) for each of the 12 original files (we divided them into 100 x 100 blocks, if you remember). Test this with the following query:

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT COUNT(*) AS num_raster,

MIN(filename) as original_file FROM chp01.tmax_2012

GROUP BY filename ORDER BY filename;

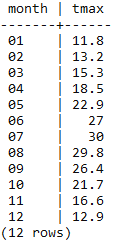

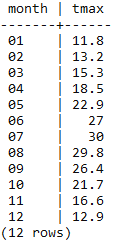

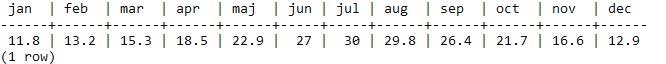

SELECT REPLACE(REPLACE(filename, 'tmax', ''), '.bil', '') AS month,

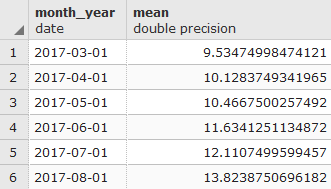

(ST_VALUE(rast, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))/10) AS tmax

FROM chp01.tmax_2012

WHERE rid IN (

SELECT rid FROM chp01.tmax_2012

WHERE ST_Intersects(ST_Envelope(rast),

ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))

)

ORDER BY month;

The output of the preceding command is as shown here:

$ gdalbuildvrt -separate tmax_2012.vrt worldclim/tmax*.bil

<VRTDataset rasterXSize="2160" rasterYSize="900">

<SRS>GEOGCS...</SRS>

<GeoTransform>

-1.8000000000000006e+02, 1.6666666666666699e-01, ...

</GeoTransform>

<VRTRasterBand dataType="Int16" band="1">

<NoDataValue>-9.99900000000000E+03</NoDataValue>

<ComplexSource>

<SourceFilename relativeToVRT="1">

worldclim/tmax01.bil

</SourceFilename>

<SourceBand>1</SourceBand>

<SourceProperties RasterXSize="2160" RasterYSize="900"

DataType="Int16" BlockXSize="2160" BlockYSize="1" />

<SrcRect xOff="0" yOff="0" xSize="2160" ySize="900" />

<DstRect xOff="0" yOff="0" xSize="2160" ySize="900" />

<NODATA>-9999</NODATA>

</ComplexSource>

</VRTRasterBand>

<VRTRasterBand dataType="Int16" band="2">

...

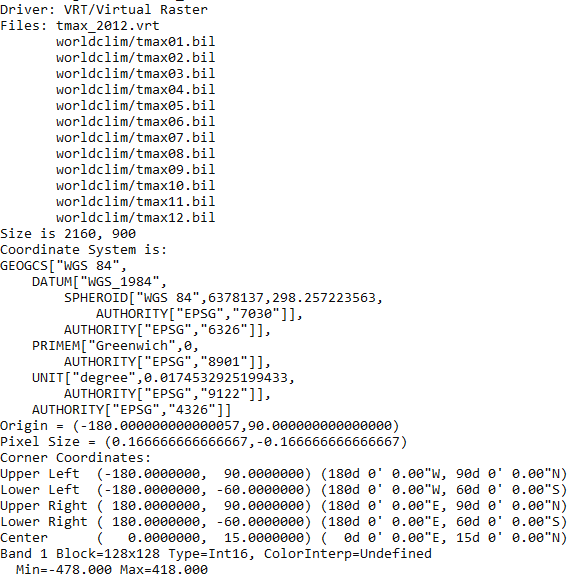

$ gdalinfo tmax_2012.vrt

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

...

...$ raster2pgsql -d -I -C -M -F -t 100x100 -s 4326 tmax_2012.vrt

chp01.tmax_2012_multi > tmax_2012_multi.sql

$ psql -d postgis_cookbook -U me -f tmax_2012_multi.sql

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT r_raster_column, srid, blocksize_x,

blocksize_y, num_bands, pixel_types

from raster_columns where r_table_schema='chp01'

AND r_table_name ='tmax_2012_multi';

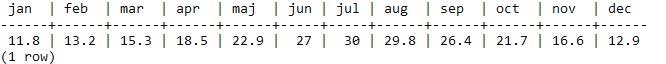

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT

(ST_VALUE(rast, 1, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))/10)

AS jan,

(ST_VALUE(rast, 2, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))/10)

AS feb,

(ST_VALUE(rast, 3, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))/10)

AS mar,

(ST_VALUE(rast, 4, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))/10)

AS apr,

(ST_VALUE(rast, 5, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))/10)

AS may,

(ST_VALUE(rast, 6, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))/10)

AS jun,

(ST_VALUE(rast, 7, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))/10)

AS jul,

(ST_VALUE(rast, 8, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))/10)

AS aug,

(ST_VALUE(rast, 9, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))/10)

AS sep,

(ST_VALUE(rast, 10, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))/10)

AS oct,

(ST_VALUE(rast, 11, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))/10)

AS nov,

(ST_VALUE(rast, 12, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))/10)

AS dec

FROM chp01.tmax_2012_multi WHERE rid IN (

SELECT rid FROM chp01.tmax_2012_multi

WHERE ST_Intersects(rast, ST_SetSRID(ST_Point(12.49, 41.88), 4326))

);

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

You can import raster datasets in PostGIS using the raster2pgsql command.

In a scenario where you have multiple rasters representing the same variable at different times, as in this recipe, it makes sense to store all of the original rasters as a single table in PostGIS. In this recipe, we have the same variable (average maximum temperature) represented by a single raster for each month. You have seen that you could proceed in two different ways:

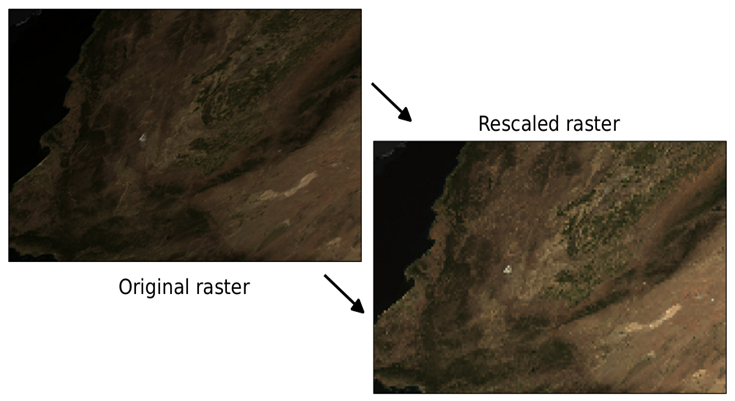

In this recipe, you will see a couple of main options for exporting PostGIS rasters to different raster formats. They are both provided as command-line tools, gdal_translate and gdalwarp, by GDAL.

You need the following in place before you can proceed with the steps required for the recipe:

$ gdalinfo --formats | grep -i postgis

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

PostGISRaster (rw): PostGIS Raster driver

$ gdalinfo PG:"host=localhost port=5432

dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me' password='mypassword'

schema='chp01' table='tmax_2012_multi' mode='2'"

The steps you need to follow to complete this recipe are as follows:

$ gdal_translate -b 1 -b 2 -b 3 -b 4 -b 5 -b 6

PG:"host=localhost port=5432 dbname='postgis_cookbook'

user='me' password='mypassword' schema='chp01'

table='tmax_2012_multi' mode='2'" tmax_2012_multi_123456.tif

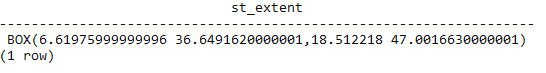

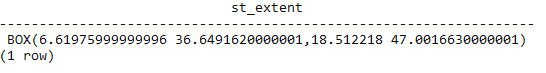

postgis_cookbook=# SELECT ST_Extent(the_geom)

FROM chp01.countries WHERE name = 'Italy';

The output of the preceding command is as follows:

$ gdal_translate -projwin 6.619 47.095 18.515 36.649

PG:"host=localhost port=5432 dbname='postgis_cookbook'

user='me' password='mypassword' schema='chp01'

table='tmax_2012_multi' mode='2'" tmax_2012_multi.tif

gdalwarp -t_srs EPSG:3857 PG:"host=localhost port=5432

dbname='postgis_cookbook' user='me' password='mypassword'

schema='chp01' table='tmax_2012_multi' mode='2'"

tmax_2012_multi_3857.tif

Both gdal_translate and gdalwarp can transform rasters from a PostGIS raster to all GDAL-supported formats. To get a complete list of the supported formats, you can use the --formats option of GDAL's command line as follows:

$ gdalinfo --formats

For both these GDAL commands, the default output format is GeoTiff; if you need a different format, you must use the -of option and assign to it one of the outputs produced by the previous command line.

In this recipe, you have tried some of the most common options for these two commands. As they are complex tools, you may try some more command options as a bonus step.

To get a better understanding, you should check out the excellent documentation on the GDAL website:

In this chapter, we will cover:

This chapter focuses on ways to structure data using the functionality provided by the combination of PostgreSQL and PostGIS. These will be useful approaches for structuring and cleaning up imported data, converting tabular data into spatial data on the fly when it is entered, and maintaining relationships between tables and datasets using functionality endemic to the powerful combination of PostgreSQL and PostGIS. There are three categories of techniques with which we will leverage these functionalities: automatic population and modification of data using views and triggers, object orientation using PostgreSQL table inheritance, and using PostGIS functions (stored procedures) to reconstruct and normalize problematic data.

Automatic population of data is where the chapter begins. By leveraging PostgreSQL views and triggers, we can create ad hoc and flexible solutions to create connections between and within the tables. By extension, and for more formal or structured cases, PostgreSQL provides table inheritance and table partitioning, which allow for explicit hierarchical relationships between tables. This can be useful in cases where an object inheritance model enforces data relationships that either represent the data better, thereby resulting in greater efficiencies, or reduce the administrative overhead of maintaining and accessing the datasets over time. With PostGIS extending that functionality, the inheritance can apply not just to the commonly used table attributes, but to leveraging spatial relationships between tables, resulting in greater query efficiency with very large datasets. Finally, we will explore PostGIS SQL patterns that provide table normalization of data inputs, so datasets that come from flat filesystems or are not normalized can be converted to a form we would expect in a database.

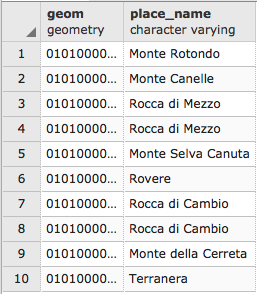

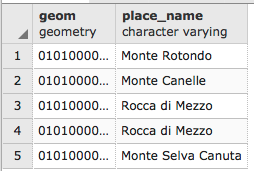

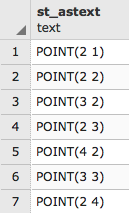

Views in PostgreSQL allow the ad hoc representation of data and data relationships in alternate forms. In this recipe, we'll be using views to allow for the automatic creation of point data based on tabular inputs. We can imagine a case where the input stream of data is non-spatial, but includes longitude and latitude or some other coordinates. We would like to automatically show this data as points in space.

We can create a view as a representation of spatial data pretty easily. The syntax for creating a view is similar to creating a table, for example:

CREATE VIEW viewname AS SELECT...

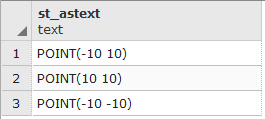

In the preceding command line, our SELECT query manipulates the data for us. Let's start with a small dataset. In this case, we will start with some random points, which could be real data.

First, we create the table from which the view will be constructed, as follows:

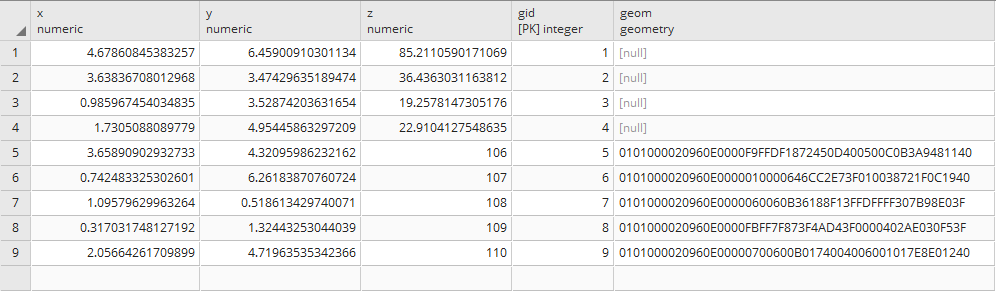

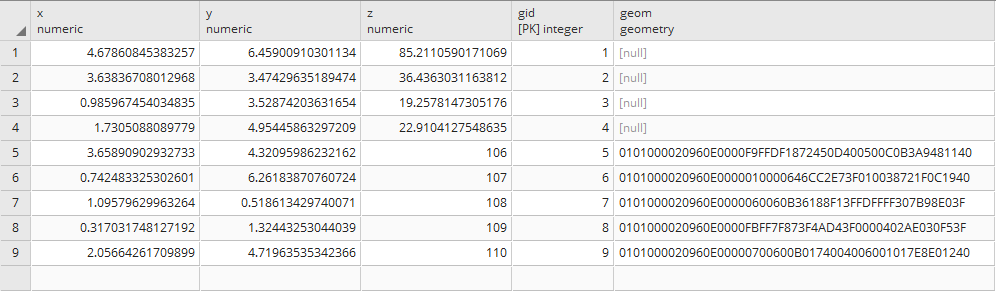

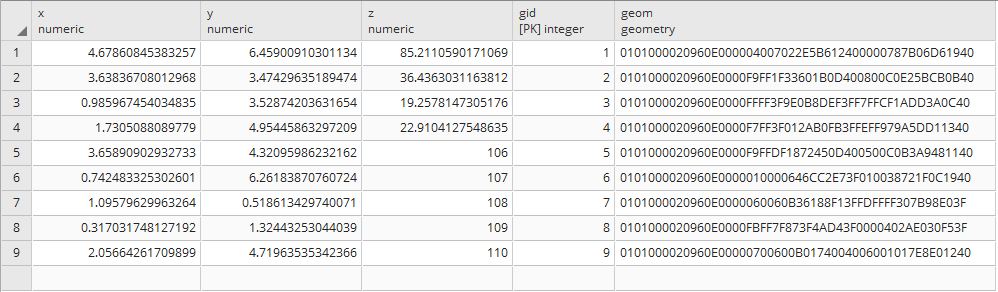

-- Drop the table in case it exists DROP TABLE IF EXISTS chp02.xwhyzed CASCADE; CREATE TABLE chp02.xwhyzed -- This table will contain numeric x, y, and z values ( x numeric, y numeric, z numeric ) WITH (OIDS=FALSE); ALTER TABLE chp02.xwhyzed OWNER TO me; -- We will be disciplined and ensure we have a primary key ALTER TABLE chp02.xwhyzed ADD COLUMN gid serial; ALTER TABLE chp02.xwhyzed ADD PRIMARY KEY (gid);

Now, let's populate this with the data for testing using the following query:

INSERT INTO chp02.xwhyzed (x, y, z) VALUES (random()*5, random()*7, random()*106); INSERT INTO chp02.xwhyzed (x, y, z) VALUES (random()*5, random()*7, random()*106); INSERT INTO chp02.xwhyzed (x, y, z) VALUES (random()*5, random()*7, random()*106); INSERT INTO chp02.xwhyzed (x, y, z) VALUES (random()*5, random()*7, random()*106);

Now, to create the view, we will use the following query:

-- Ensure we don't try to duplicate the view DROP VIEW IF EXISTS chp02.xbecausezed; -- Retain original attributes, but also create a point attribute from x and y CREATE VIEW chp02.xbecausezed AS SELECT x, y, z, ST_MakePoint(x,y) FROM chp02.xwhyzed;

Our view is really a simple transformation of the existing data using PostGIS's ST_MakePoint function. The ST_MakePoint function takes the input of two numbers to create a PostGIS point, and in this case our view simply uses our x and y values to populate the data. Any time there is an update to the table to add a new record with x and y values, the view will populate a point, which is really useful for data that is constantly being updated.

There are two disadvantages to this approach. The first is that we have not declared our spatial reference system in the view, so any software consuming these points will not know the coordinate system we are using, that is, whether it is a geographic (latitude/longitude) or a planar coordinate system. We will address this problem shortly. The second problem is that many software systems accessing these points may not automatically detect and use the spatial information from the table. This problem is addressed in the Using triggers to populate the geometry column recipe.

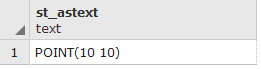

To address the first problem mentioned in the How it works... section, we can simply wrap our existing ST_MakePoint function in another function specifying the SRID as ST_SetSRID, as shown in the following query:

-- Ensure we don't try to duplicate the view DROP VIEW IF EXISTS chp02.xbecausezed; -- Retain original attributes, but also create a point attribute from x and y CREATE VIEW chp02.xbecausezed AS SELECT x, y, z, ST_SetSRID(ST_MakePoint(x,y), 3734) -- Add ST_SetSRID FROM chp02.xwhyzed;

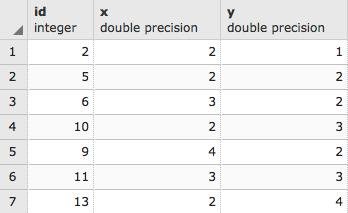

In this recipe, we imagine that we have ever increasing data in our database, which needs spatial representation; however, in this case we want a hardcoded geometry column to be updated each time an insertion happens on the database, converting our x and y values to geometry as and when they are inserted into the database.

The advantage of this approach is that the geometry is then registered in the geometry_columns view, and therefore this approach works reliably with more PostGIS client types than creating a new geospatial view. This also provides the advantage of allowing for a spatial index that can significantly speed up a variety of queries.

We will start by creating another table of random points with x, y, and z values, as shown in the following query:

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS chp02.xwhyzed1 CASCADE; CREATE TABLE chp02.xwhyzed1 ( x numeric, y numeric, z numeric ) WITH (OIDS=FALSE); ALTER TABLE chp02.xwhyzed1 OWNER TO me; ALTER TABLE chp02.xwhyzed1 ADD COLUMN gid serial; ALTER TABLE chp02.xwhyzed1 ADD PRIMARY KEY (gid); INSERT INTO chp02.xwhyzed1 (x, y, z) VALUES (random()*5, random()*7, random()*106); INSERT INTO chp02.xwhyzed1 (x, y, z) VALUES (random()*5, random()*7, random()*106); INSERT INTO chp02.xwhyzed1 (x, y, z) VALUES (random()*5, random()*7, random()*106); INSERT INTO chp02.xwhyzed1 (x, y, z) VALUES (random()*5, random()*7, random()*106);

Now we need a geometry column to populate. By default, the geometry column will be populated with null values. We populate a geometry column using the following query:

SELECT AddGeometryColumn ('chp02','xwhyzed1','geom',3734,'POINT',2);

We now have a column called geom with an SRID of 3734; that is, a point geometry type in two dimensions. Since we have x, y, and z data, we could, in principle, populate a 3D point table using a similar approach.

Since all the geometry values are currently null, we will populate them using an UPDATE statement as follows:

UPDATE chp02.xwhyzed1 SET the_geom = ST_SetSRID(ST_MakePoint(x,y), 3734);

The query here is simple when broken down. We update the xwhyzed1 table and set the the_geom column using ST_MakePoint, construct our point using the x and y columns, and wrap it in an ST_SetSRID function in order to apply the appropriate spatial reference information. So far, we have just set the table up. Now, we need to create a trigger in order to continue to populate this information once the table is in use. The first part of the trigger is a new populated geometry function using the following query:

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION chp02.before_insertXYZ() RETURNS trigger AS $$ BEGIN if NEW.geom is null then NEW.geom = ST_SetSRID(ST_MakePoint(NEW.x,NEW.y), 3734); end if; RETURN NEW; END; $$ LANGUAGE 'plpgsql';

In essence, we have created a function that does exactly what we did manually: update the table's geometry column with the combination of ST_SetSRID and ST_MakePoint, but only to the new registers being inserted, and not to all the table.

While we have a function created, we have not yet applied it as a trigger to the table. Let us do that here as follows:

CREATE TRIGGER popgeom_insert

BEFORE INSERT ON chp02.xwhyzed1

FOR EACH ROW EXECUTE PROCEDURE chp02.before_insertXYZ();

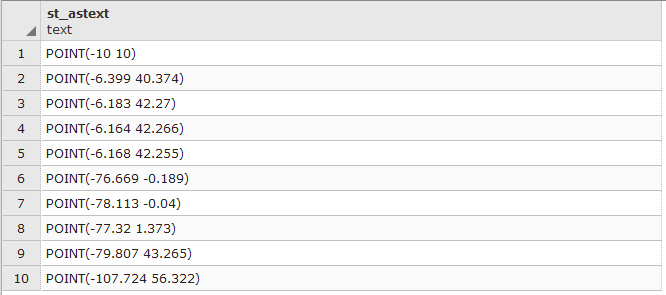

Let's assume that the general geometry column update has not taken place yet, then the original five registers still have their geometry column in null. Now, once the trigger has been activated, any inserts into our table should be populated with new geometry records. Let us do a test insert using the following query:

INSERT INTO chp02.xwhyzed1 (x, y, z)

VALUES (random()*5, random()*7, 106),

(random()*5, random()*7, 107),

(random()*5, random()*7, 108),

(random()*5, random()*7, 109),

(random()*5, random()*7, 110);

Check the rows to verify that the geom columns are updated with the command:

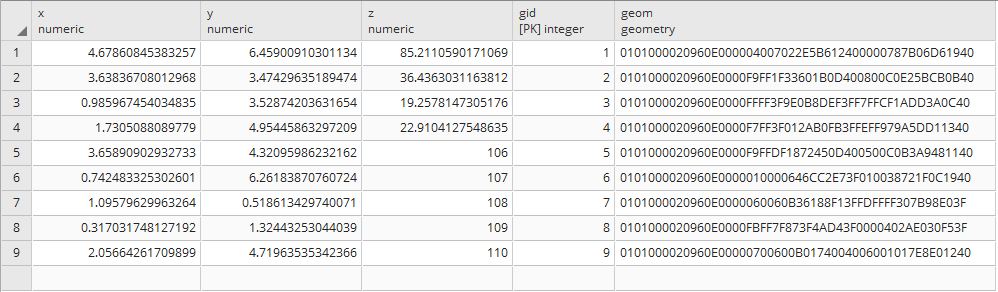

SELECT * FROM chp02.xwhyzed1;

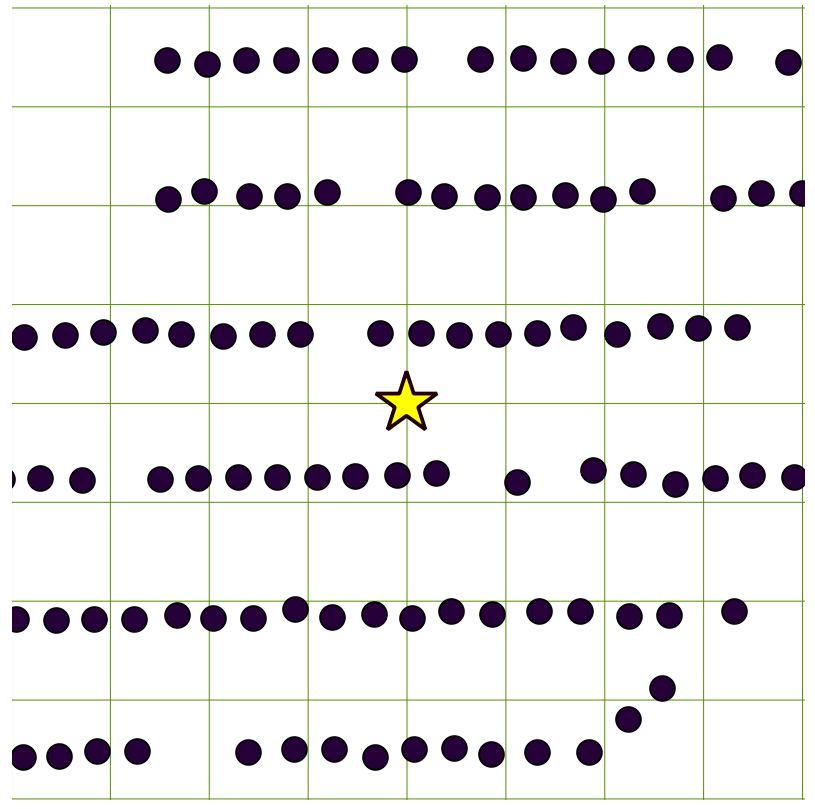

Or use pgAdmin:

After applying the general update, then all the registers will have a value on their geom column:

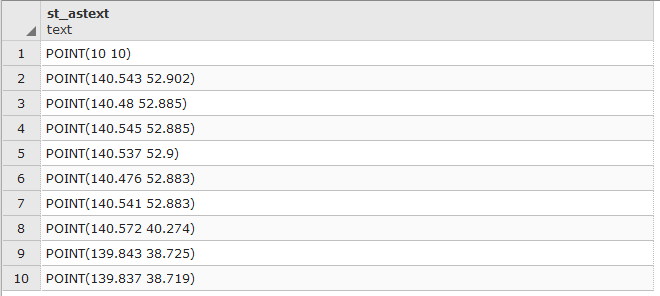

So far, we've implemented an insert trigger. What if the value changes for a particular row? In that case, we will require a separate update trigger. We'll change our original function to test the UPDATE case, and we'll use WHEN in our trigger to constrain updates to the column being changed.

Also, note that the following function is written with the assumption that the user wants to always update the changing geometries based on the changing values:

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION chp02.before_insertXYZ()

RETURNS trigger AS

$$

BEGIN

if (TG_OP='INSERT') then

if (NEW.geom is null) then

NEW.geom = ST_SetSRID(ST_MakePoint(NEW.x,NEW.y), 3734);

end if;

ELSEIF (TG_OP='UPDATE') then

NEW.geom = ST_SetSRID(ST_MakePoint(NEW.x,NEW.y), 3734);

end if;

RETURN NEW;

END;

$$

LANGUAGE 'plpgsql';

CREATE TRIGGER popgeom_insert

BEFORE INSERT ON chp02.xwhyzed1

FOR EACH ROW EXECUTE PROCEDURE chp02.before_insertXYZ();

CREATE trigger popgeom_update

BEFORE UPDATE ON chp02.xwhyzed1

FOR EACH ROW

WHEN (OLD.X IS DISTINCT FROM NEW.X OR OLD.Y IS DISTINCT FROM

NEW.Y)

EXECUTE PROCEDURE chp02.before_insertXYZ();

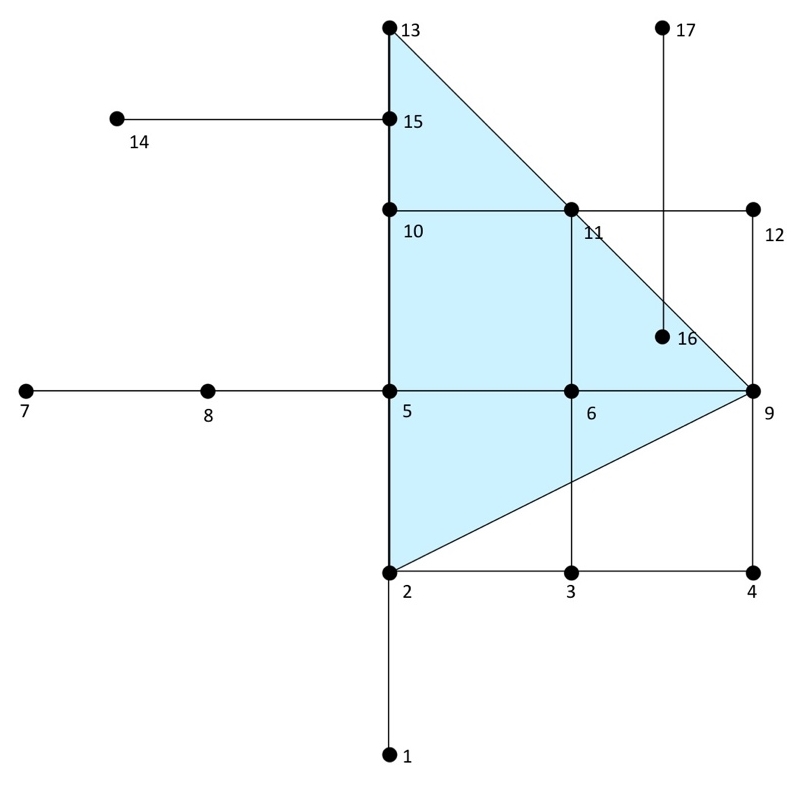

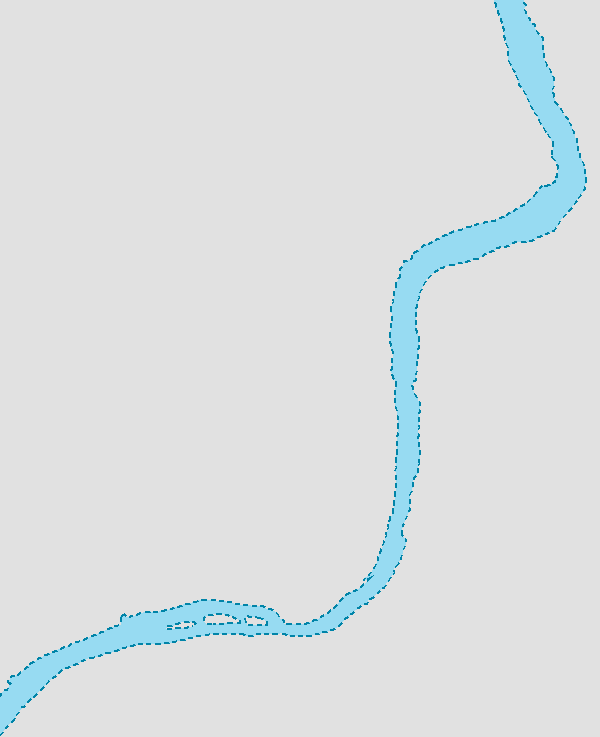

An unusual and useful property of the PostgreSQL database is that it allows for object inheritance models as they apply to tables. This means that we can have parent/child relationships between tables and leverage that to structure the data in meaningful ways. In our example, we will apply this to hydrology data. This data can be points, lines, polygons, or more complex structures, but they have one commonality: they are explicitly linked in a physical sense and inherently related; they are all about water. Water/hydrology is an excellent natural system to model this way, as our ways of modeling it spatially can be quite mixed depending on scales, details, the data collection process, and a host of other factors.

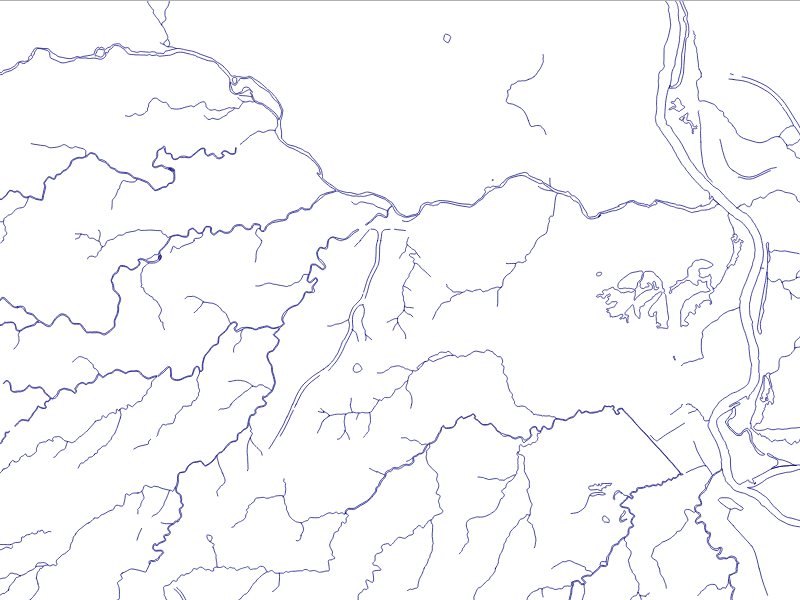

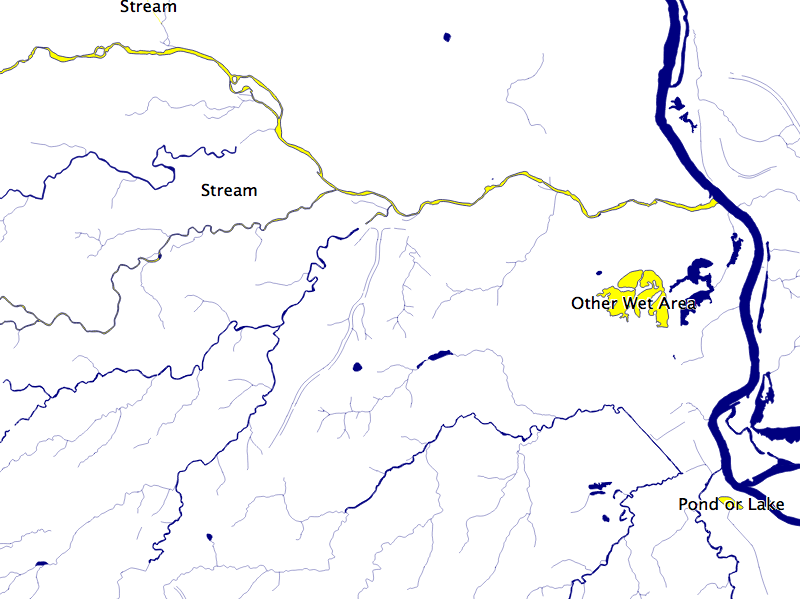

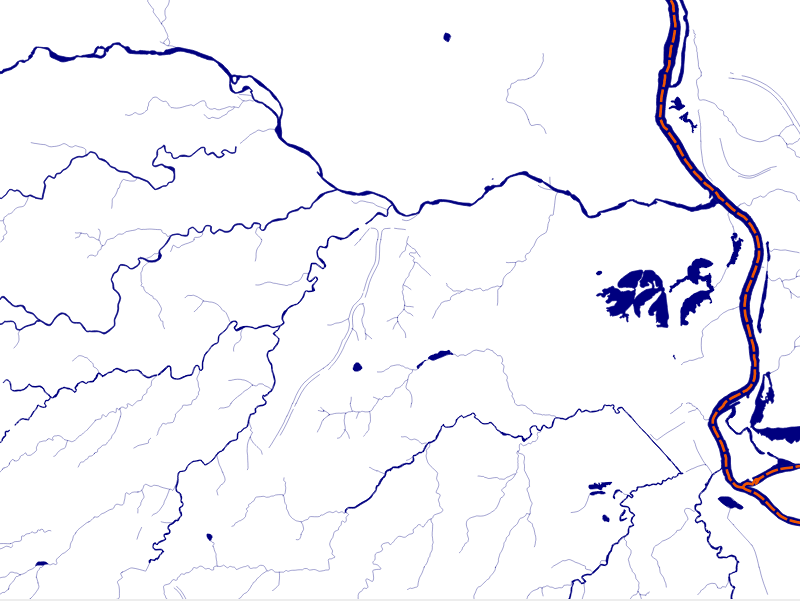

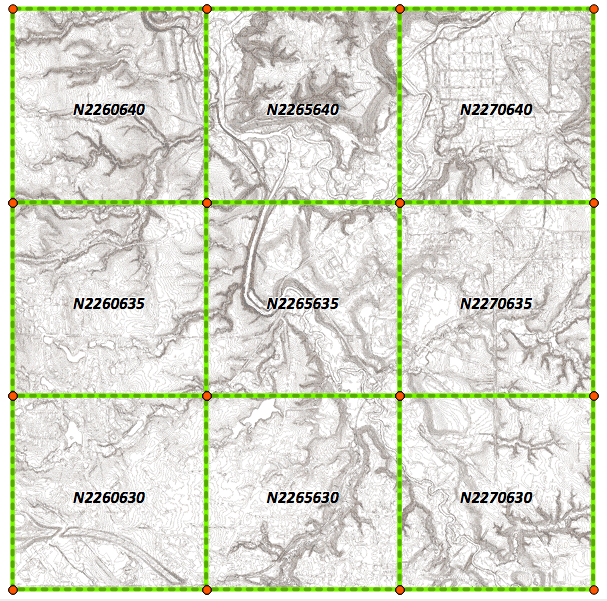

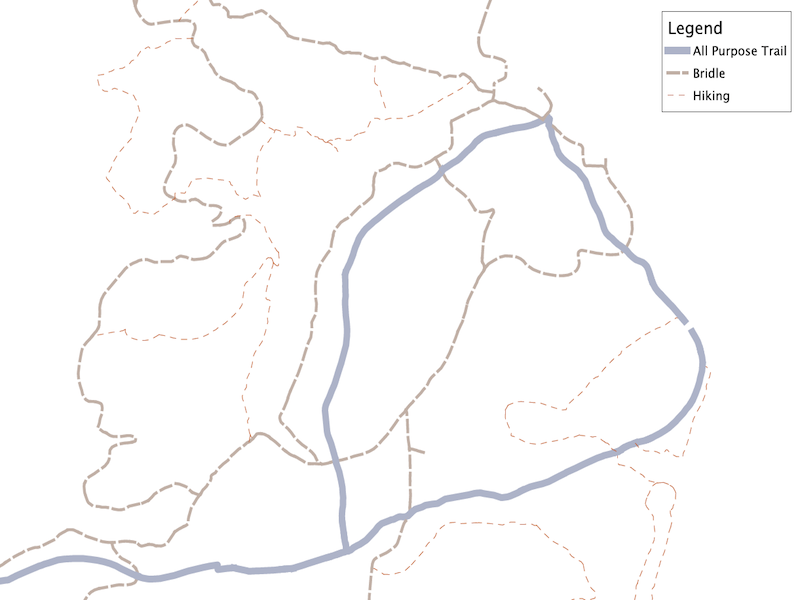

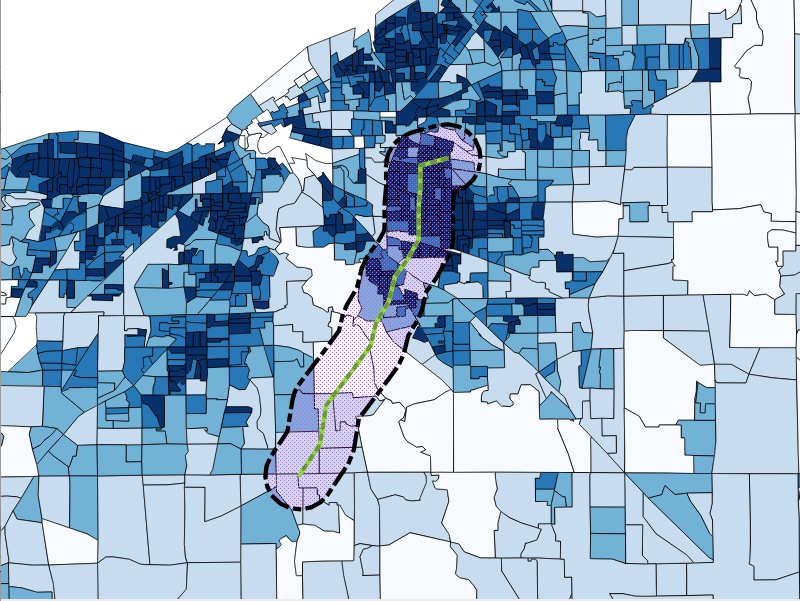

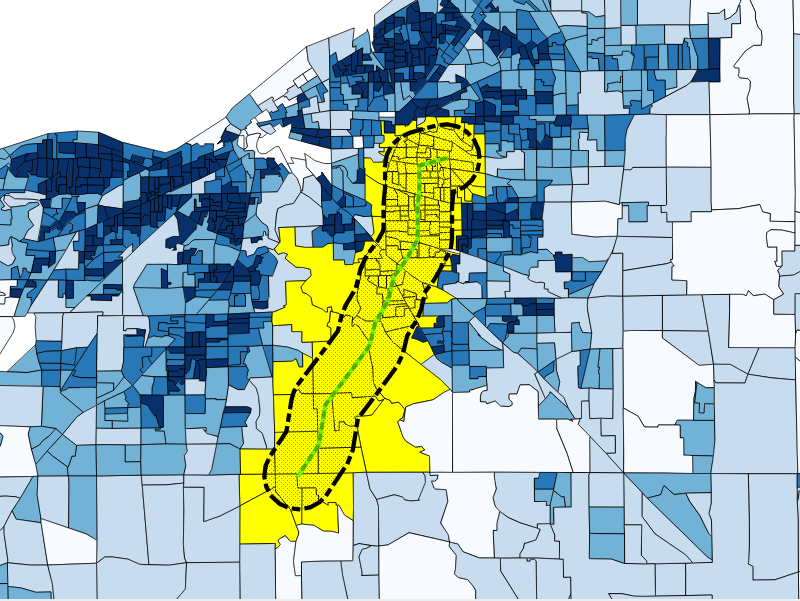

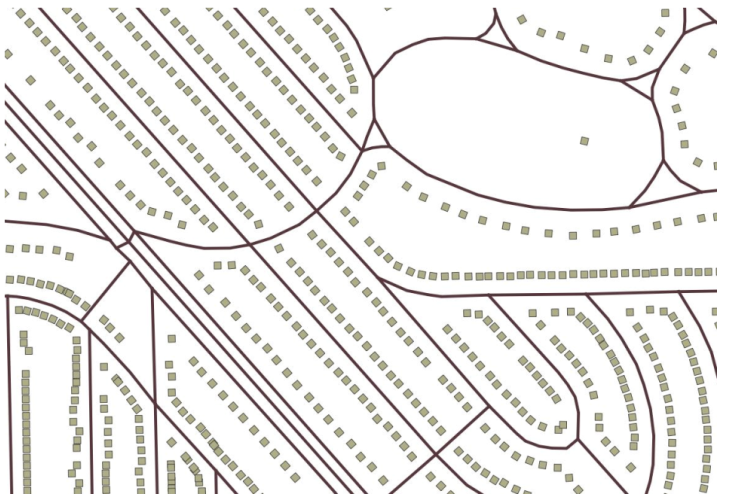

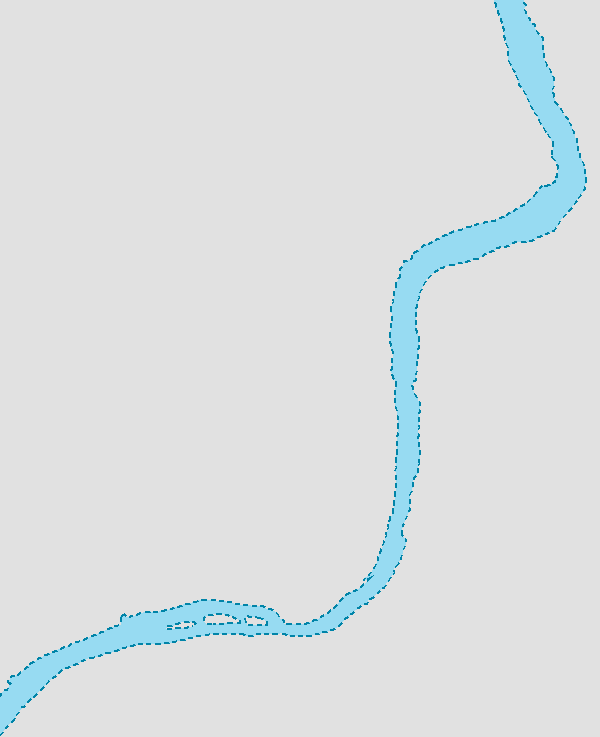

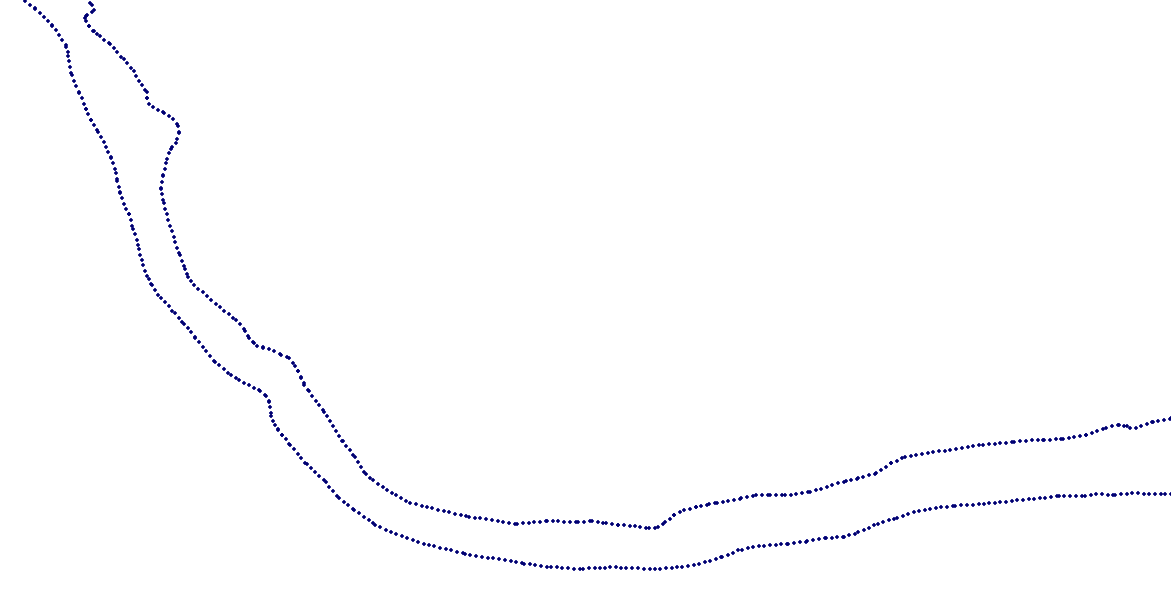

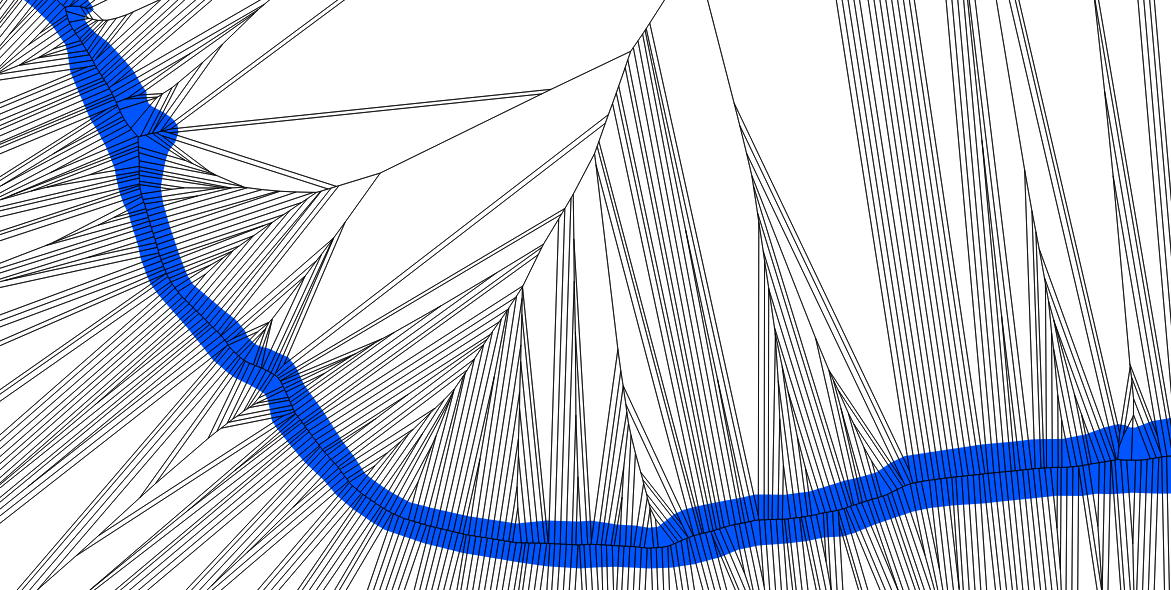

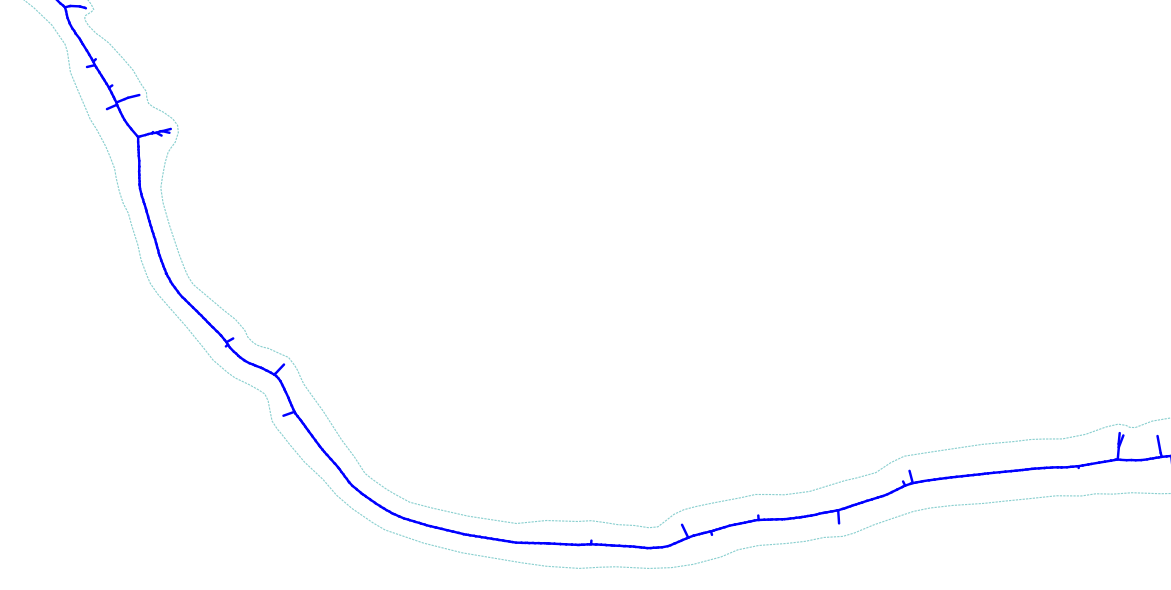

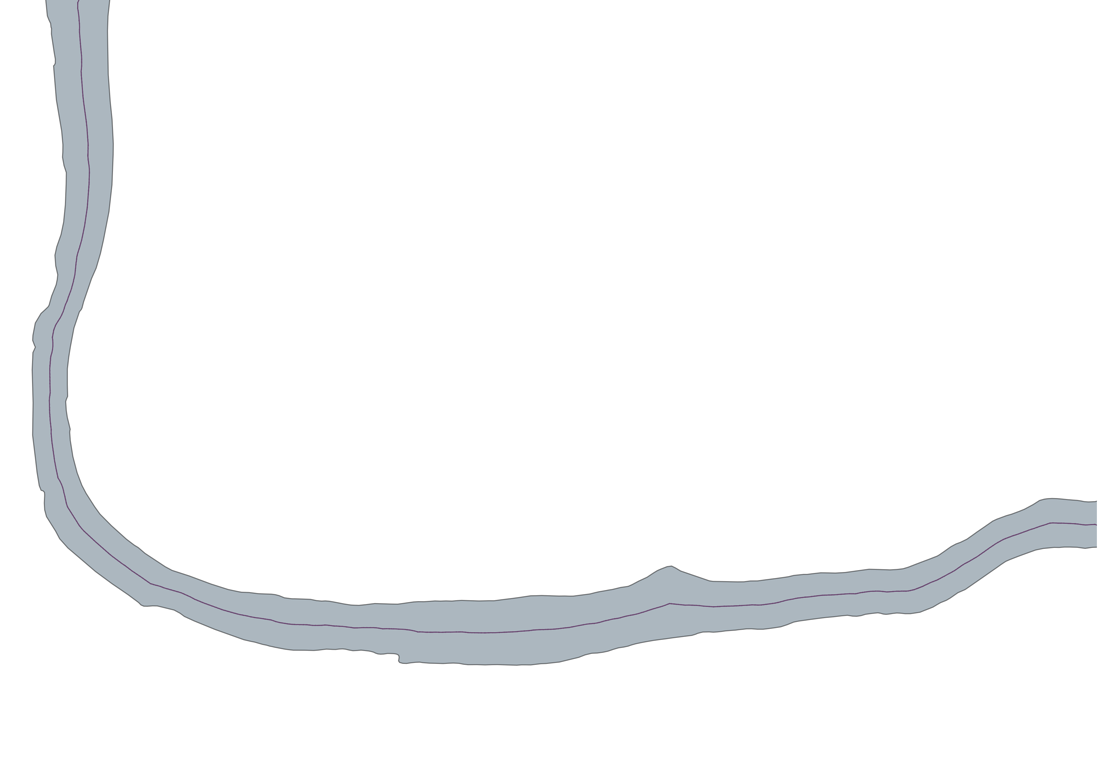

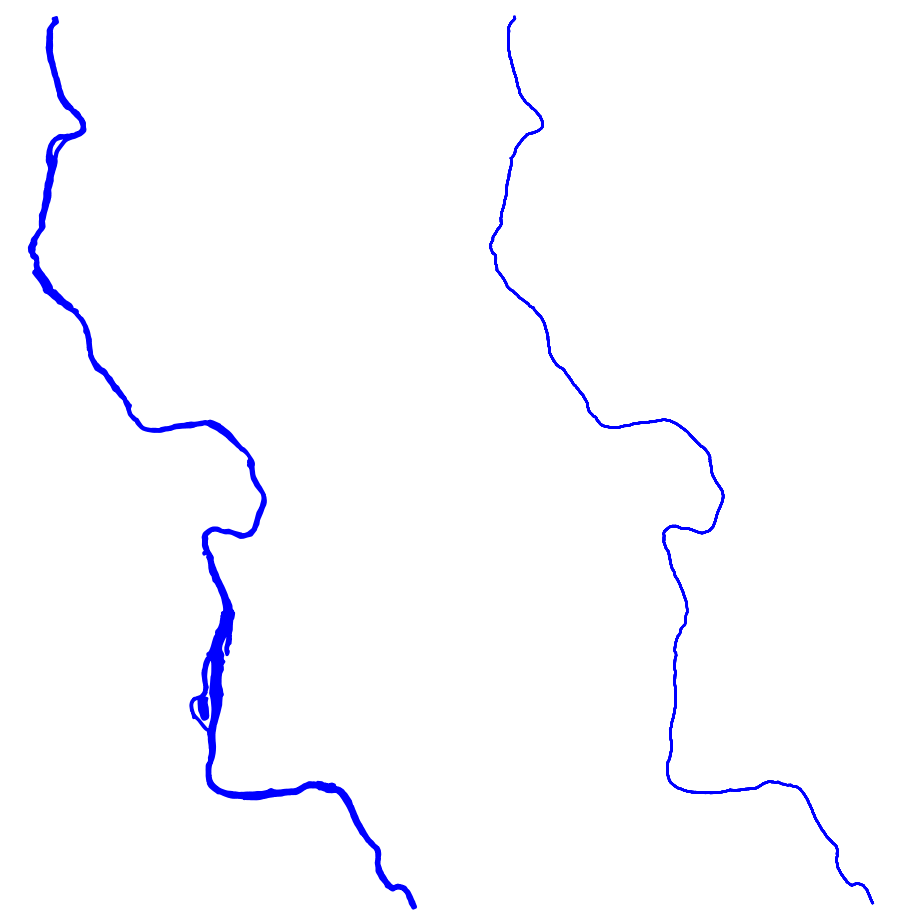

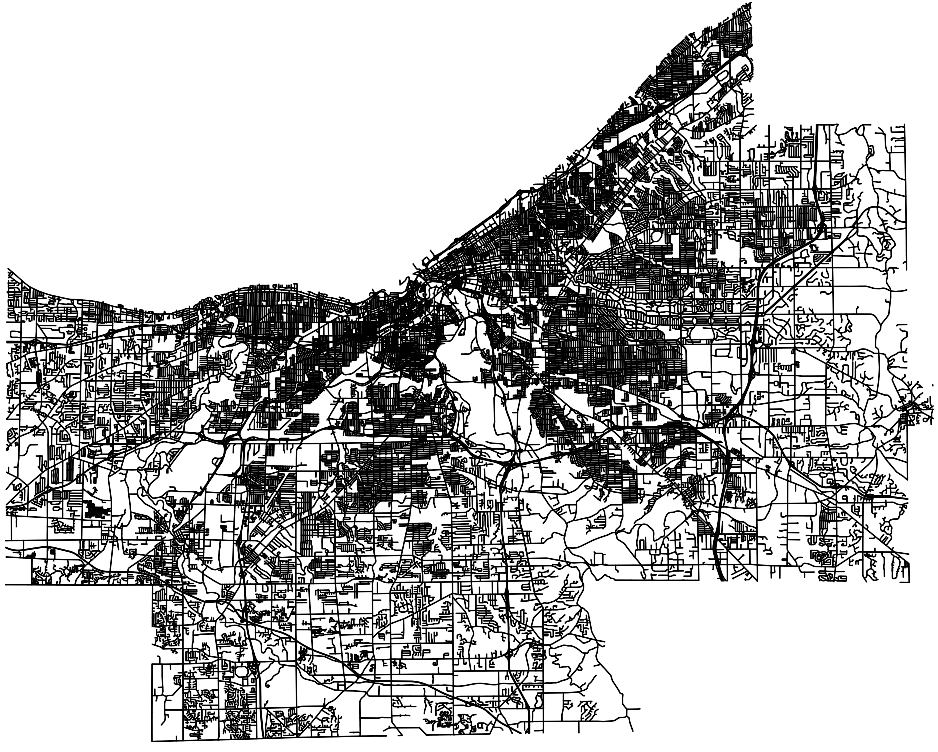

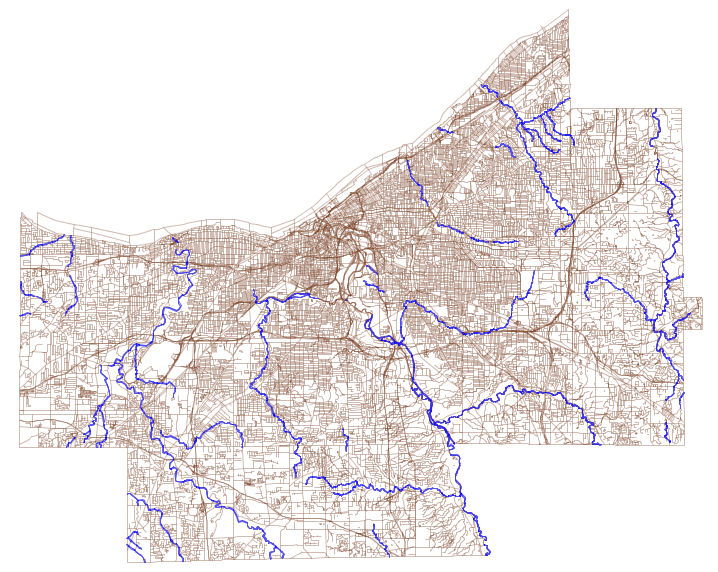

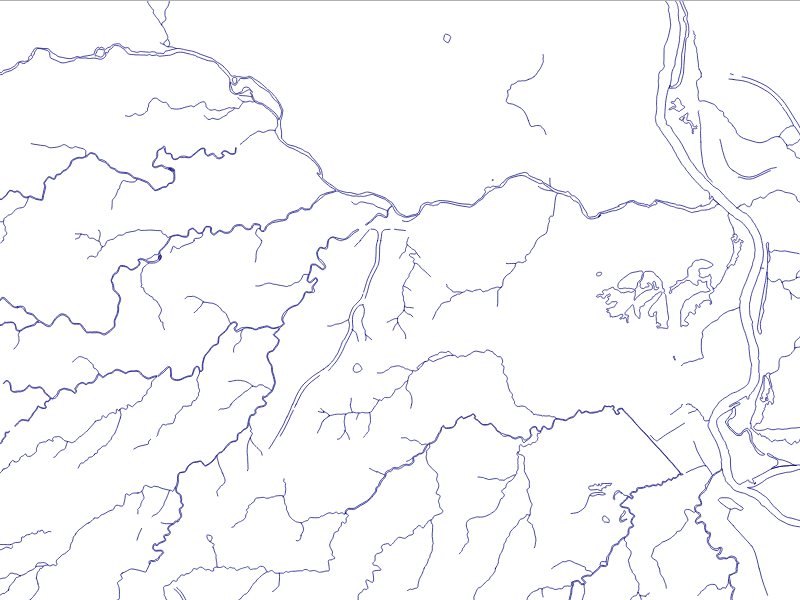

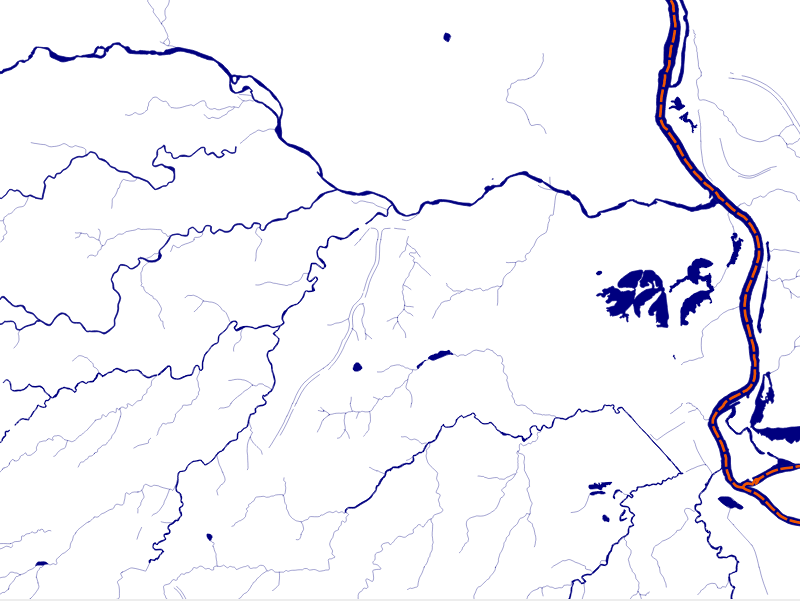

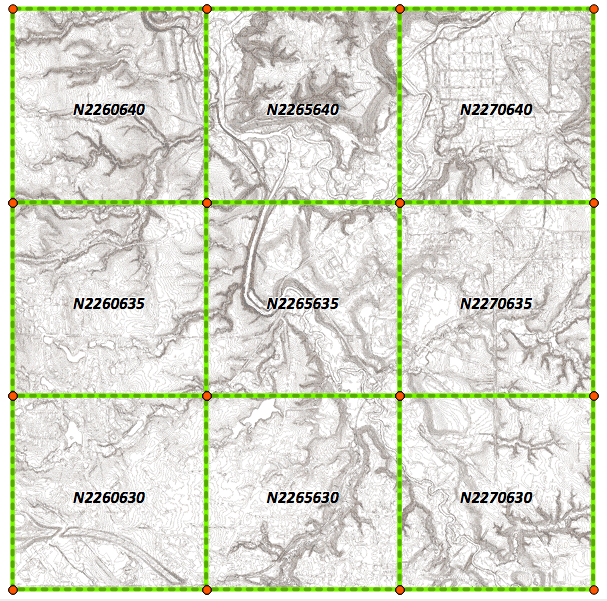

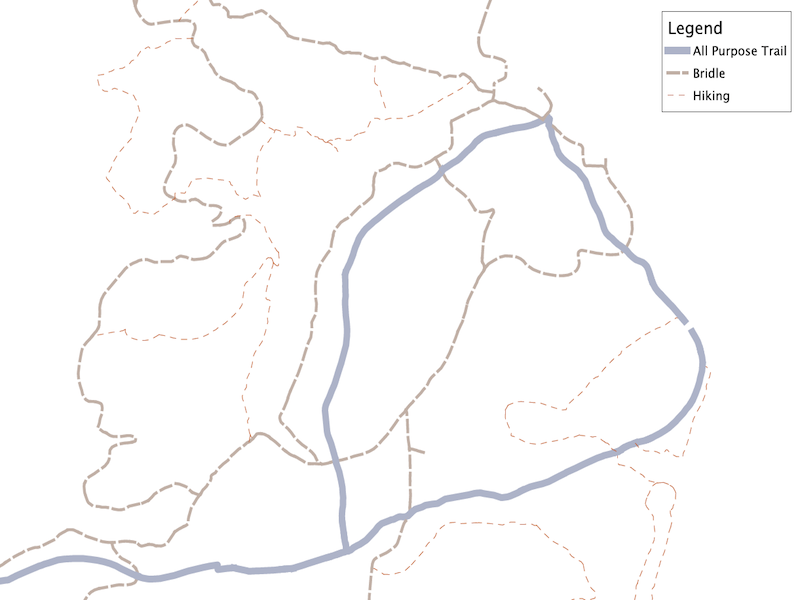

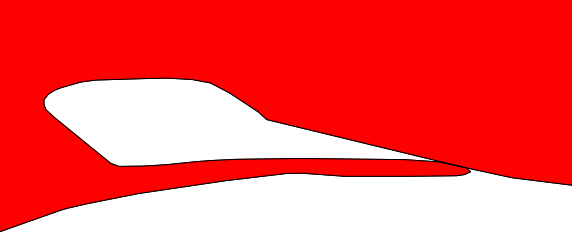

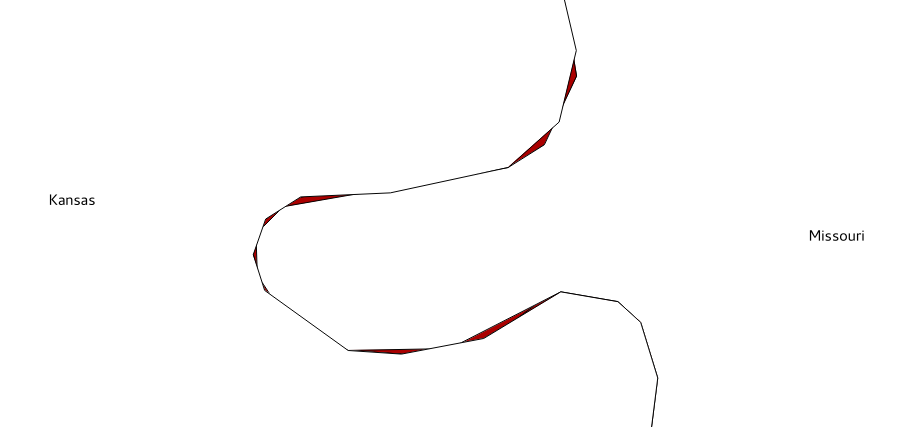

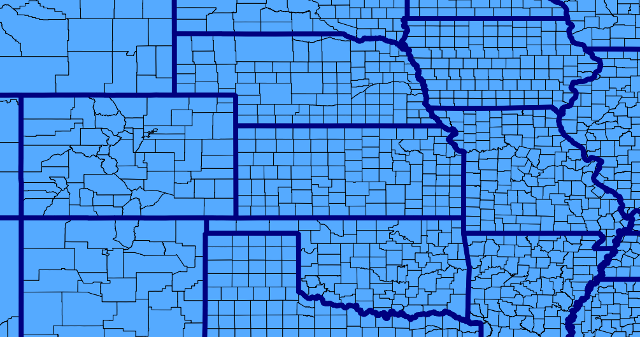

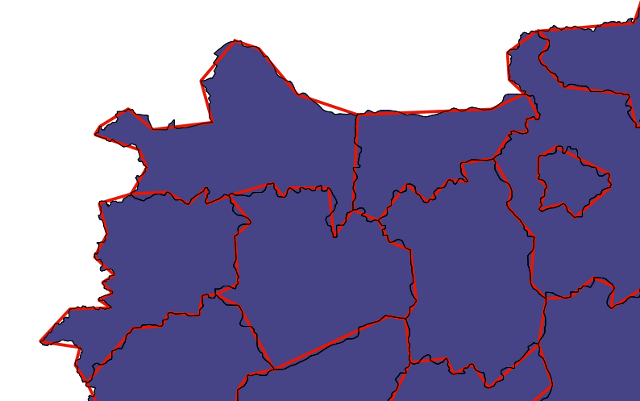

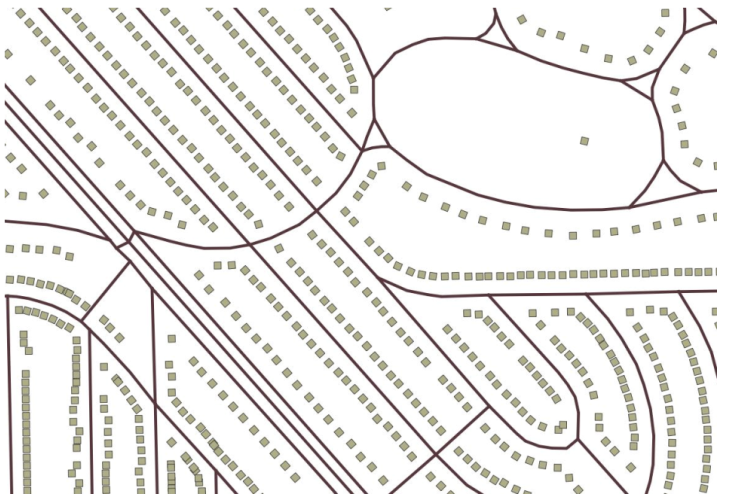

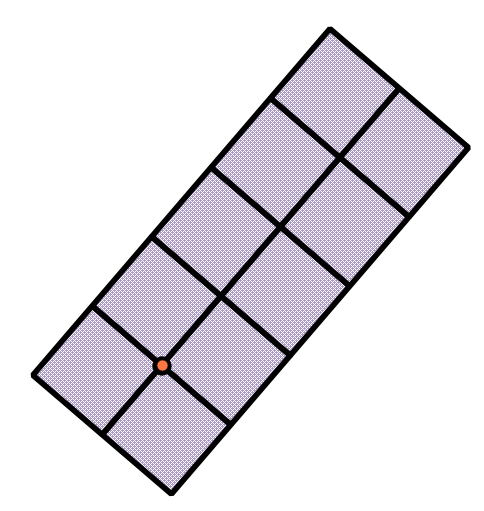

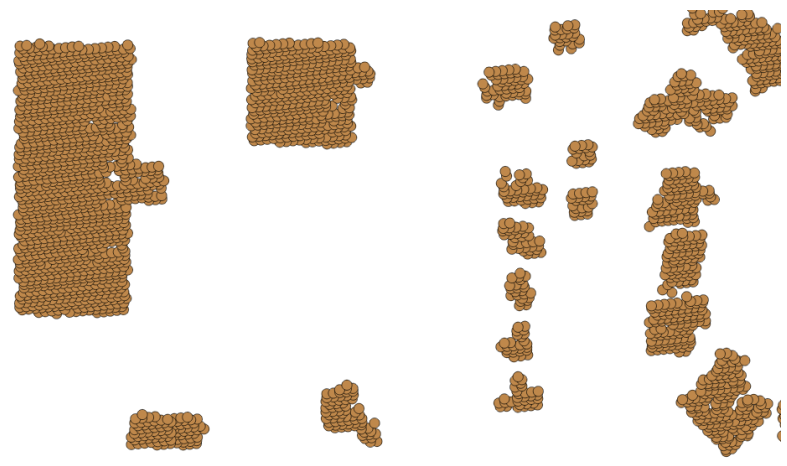

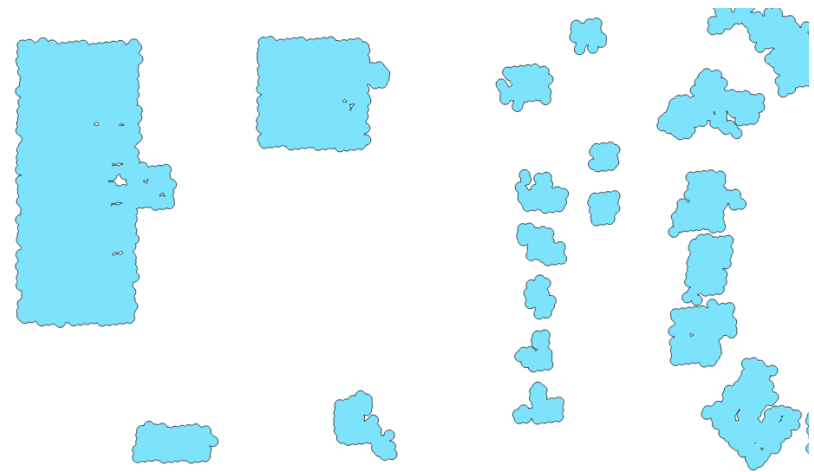

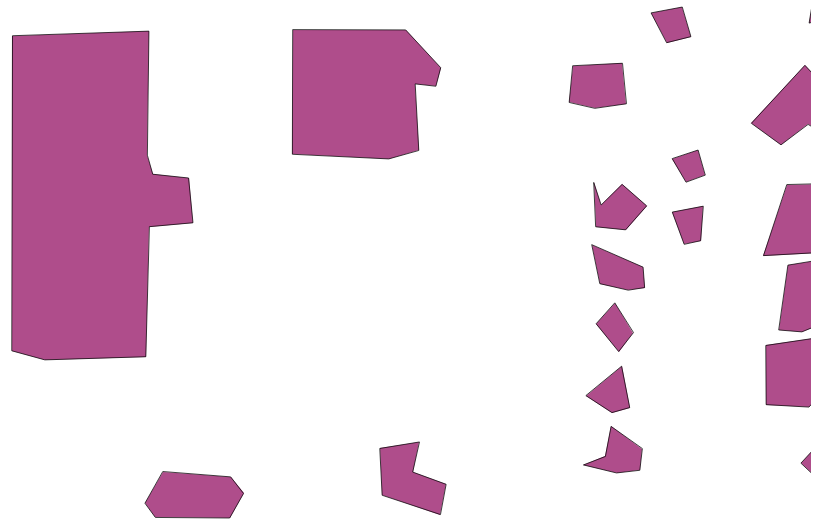

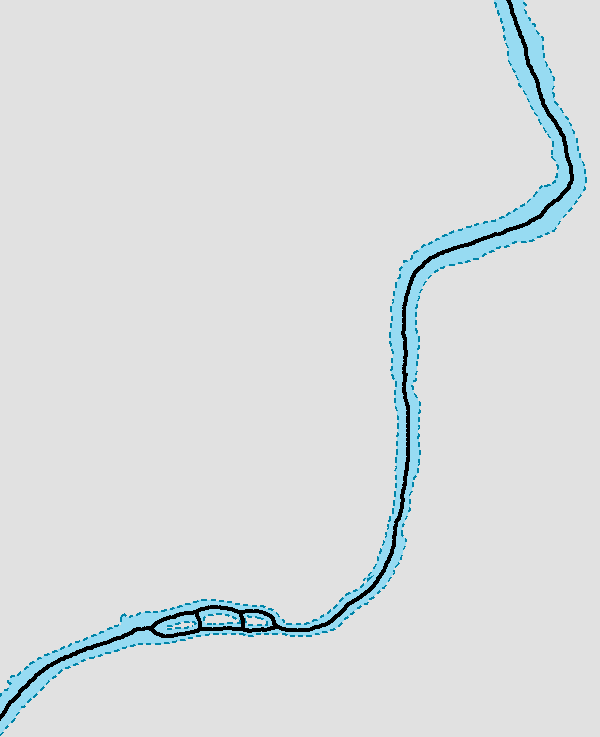

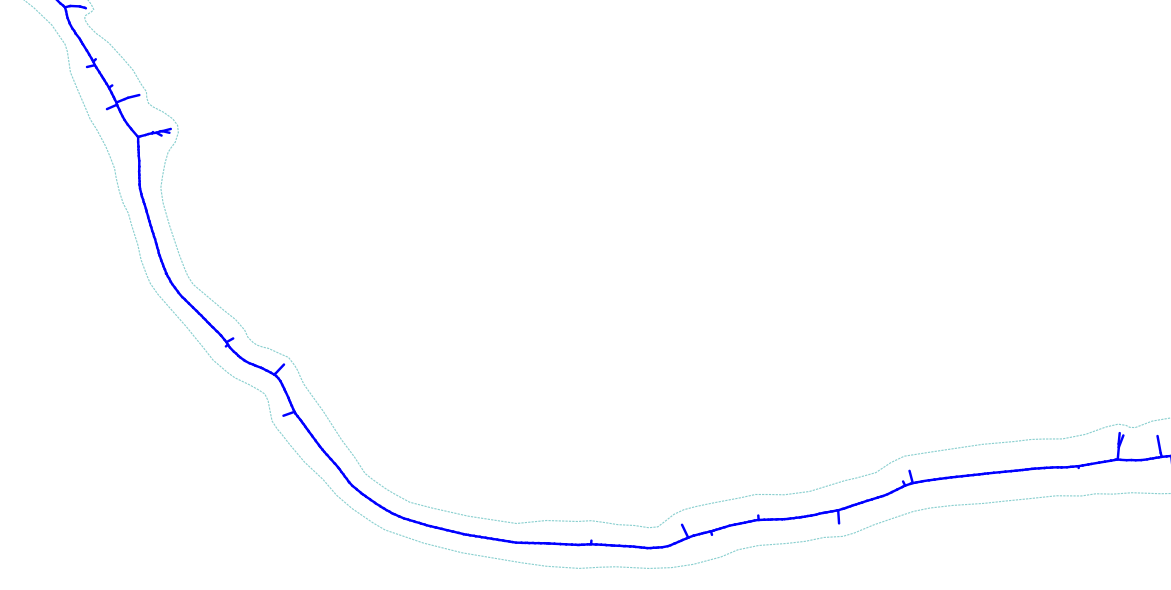

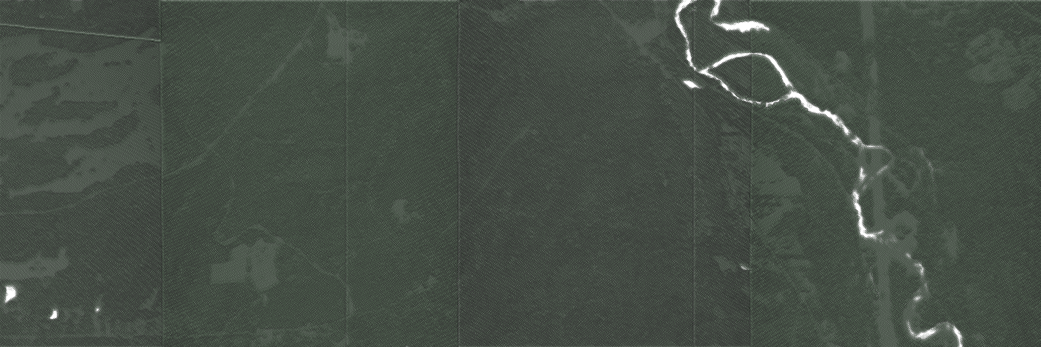

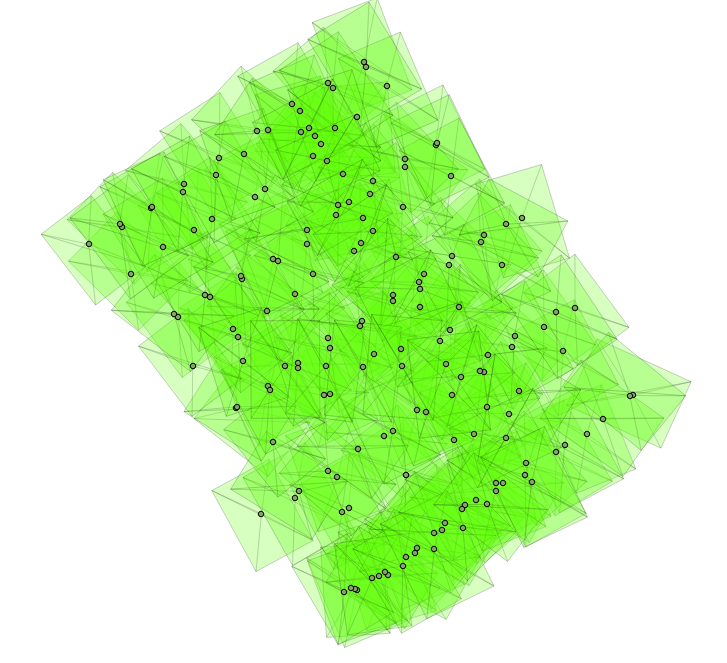

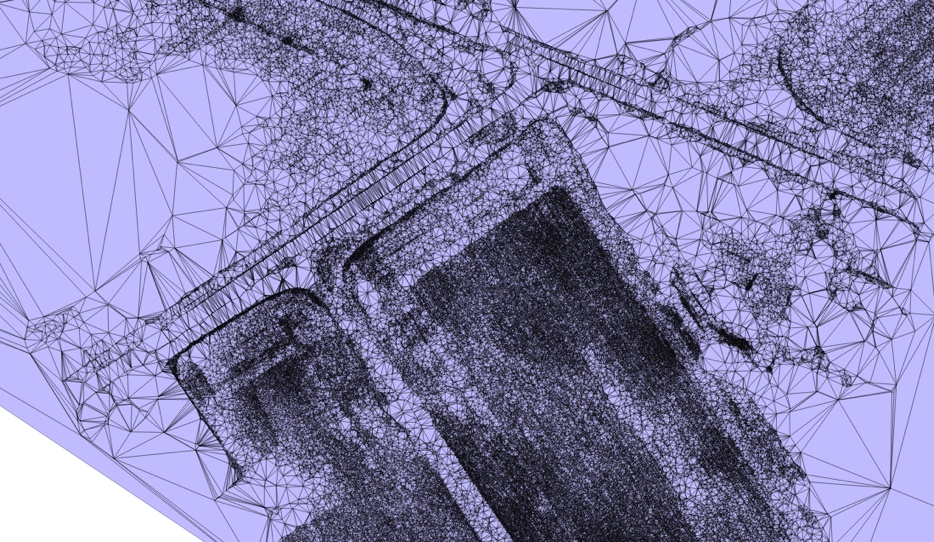

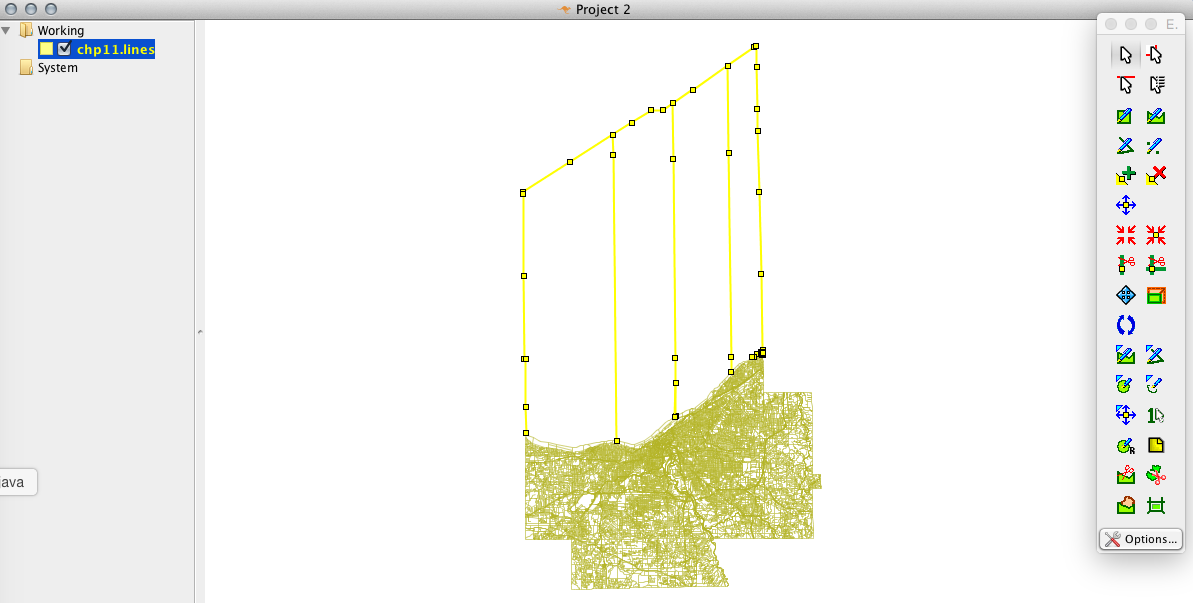

The data we will be using is hydrology data that has been modified from engineering blue lines (see the following screenshot), that is, hydrologic data that is very detailed and is meant to be used at scales approaching 1:600. The data in its original application aided, as breaklines, in detailed digital terrain modeling.

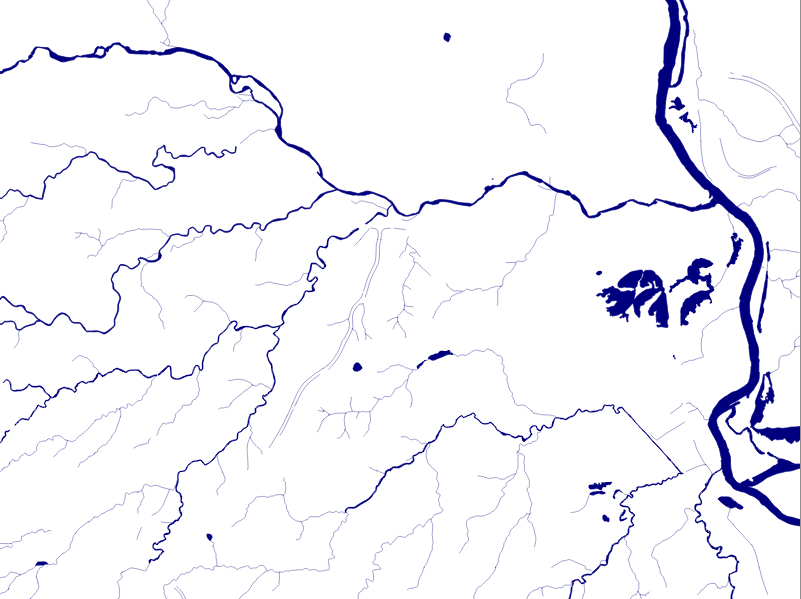

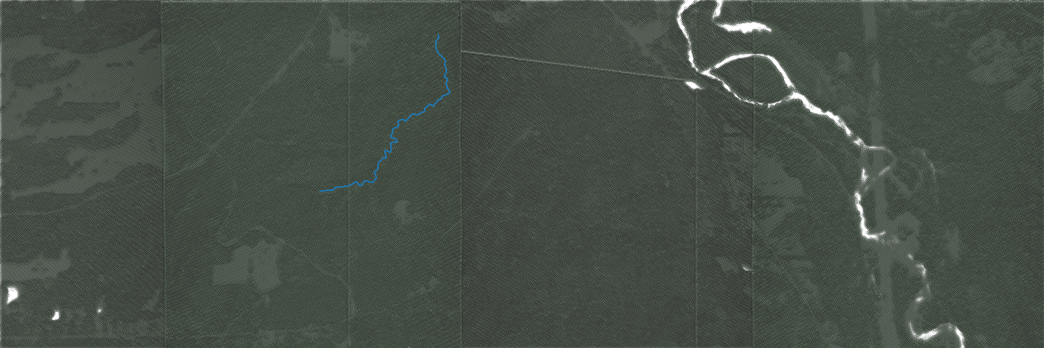

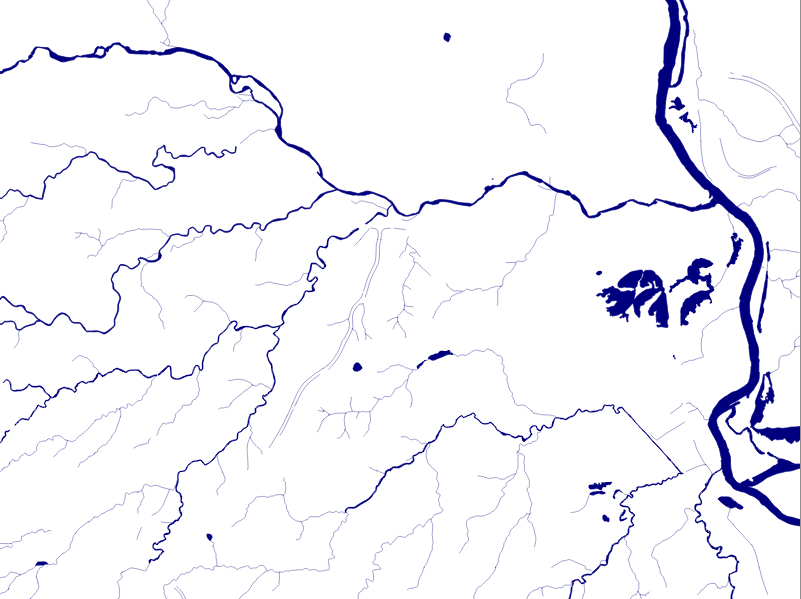

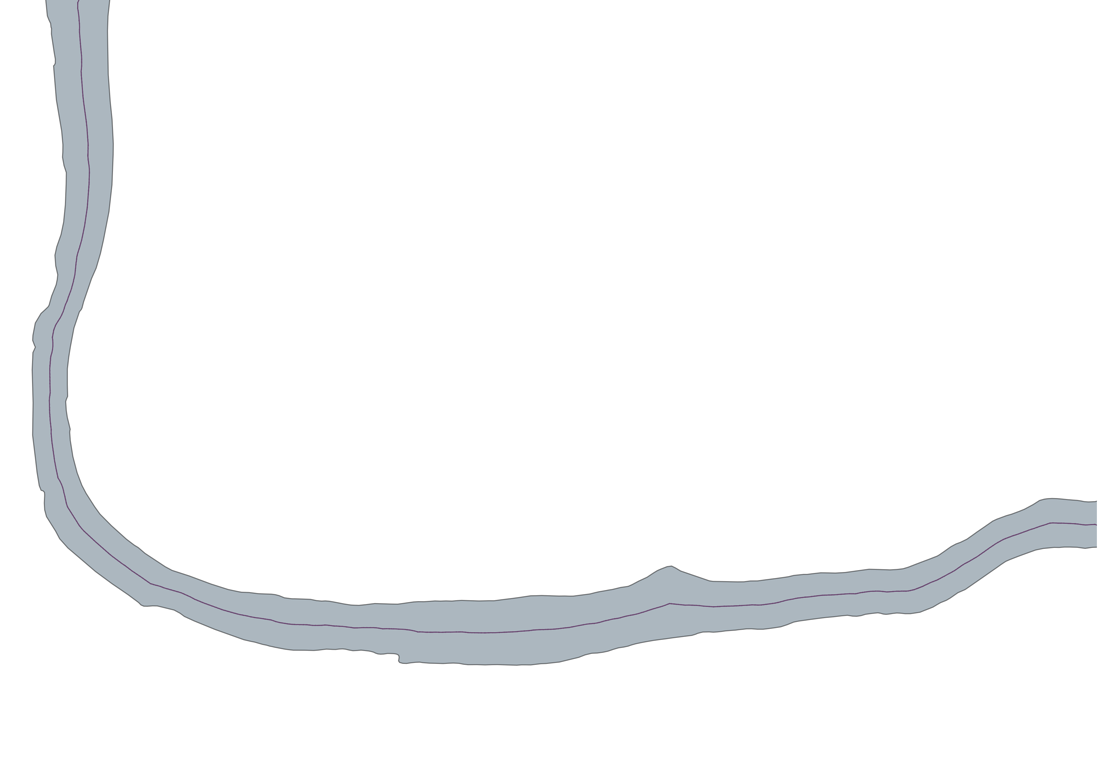

While useful in itself, the data was further manipulated, separating the linear features from area features, with additional polygonization of the area features, as shown in the following screenshot:

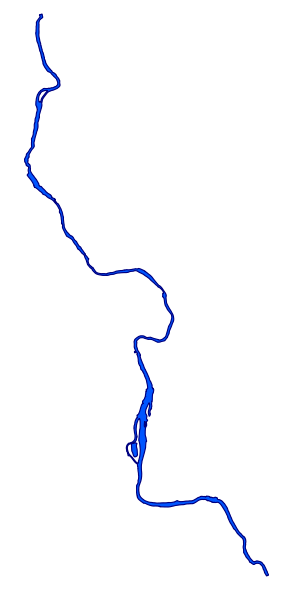

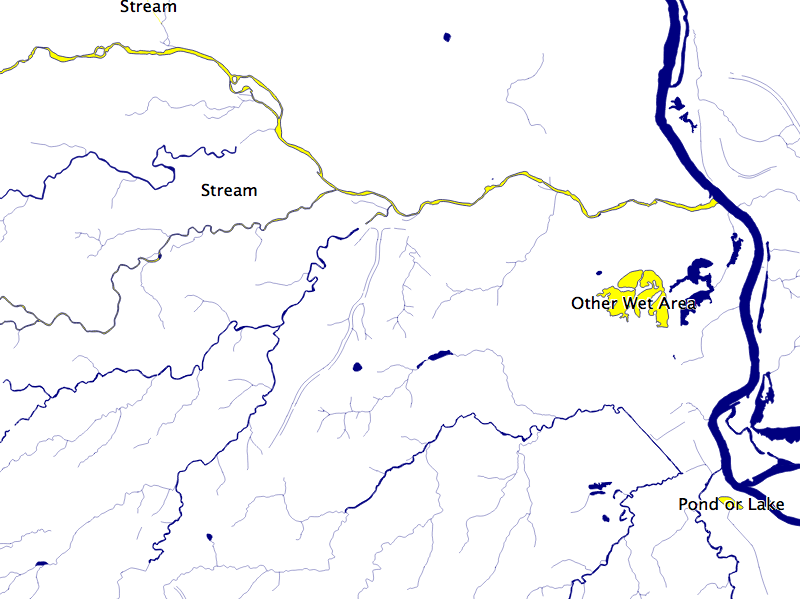

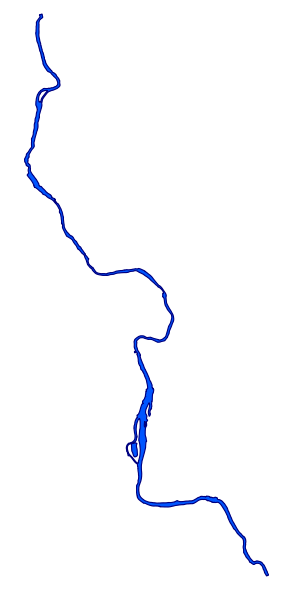

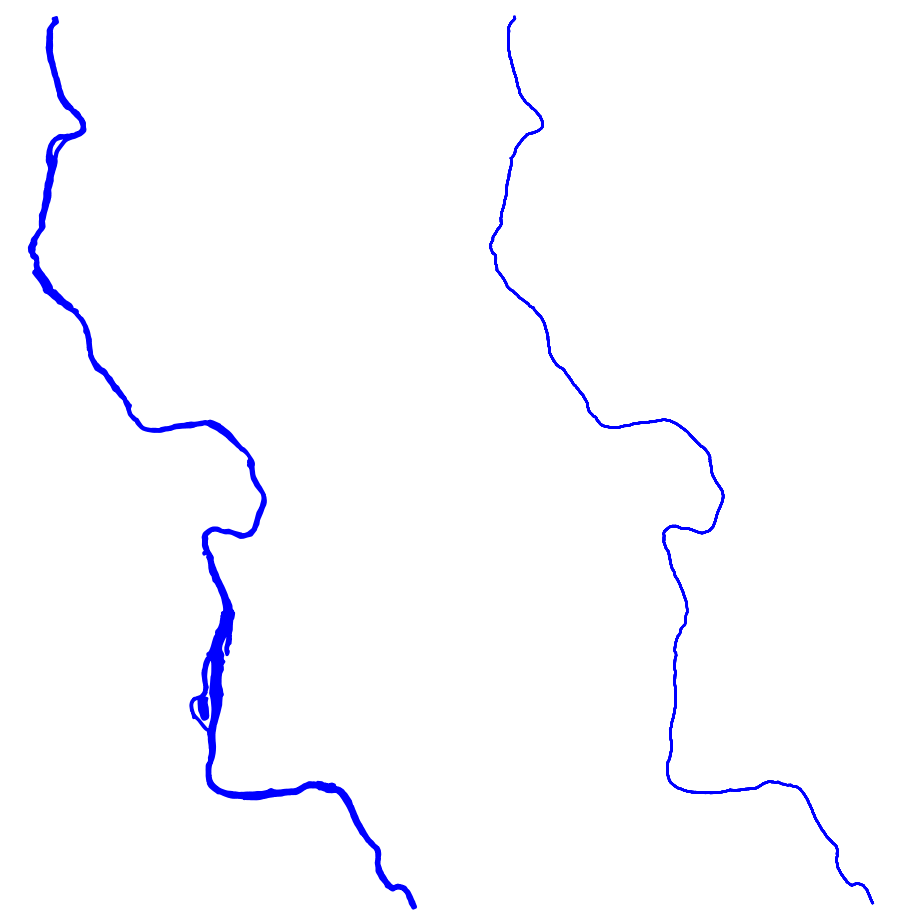

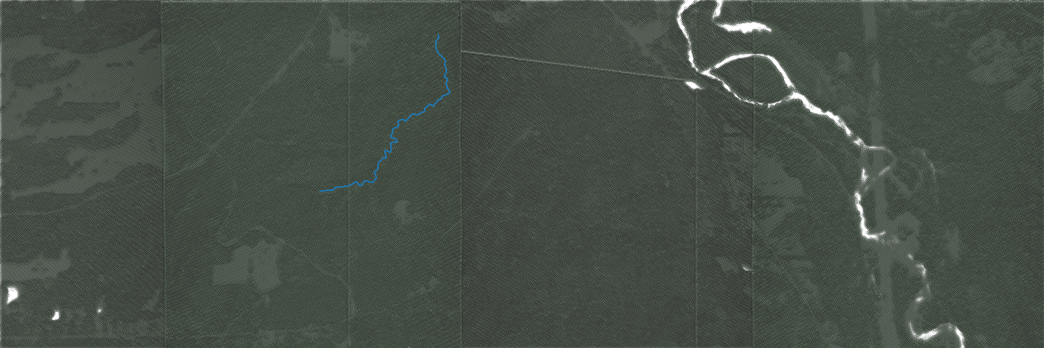

Finally, the data was classified into basic waterway categories, as follows:

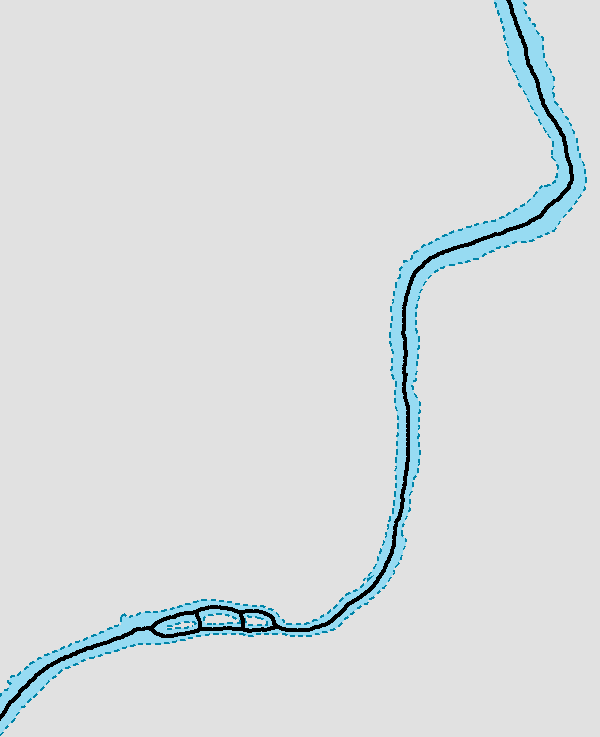

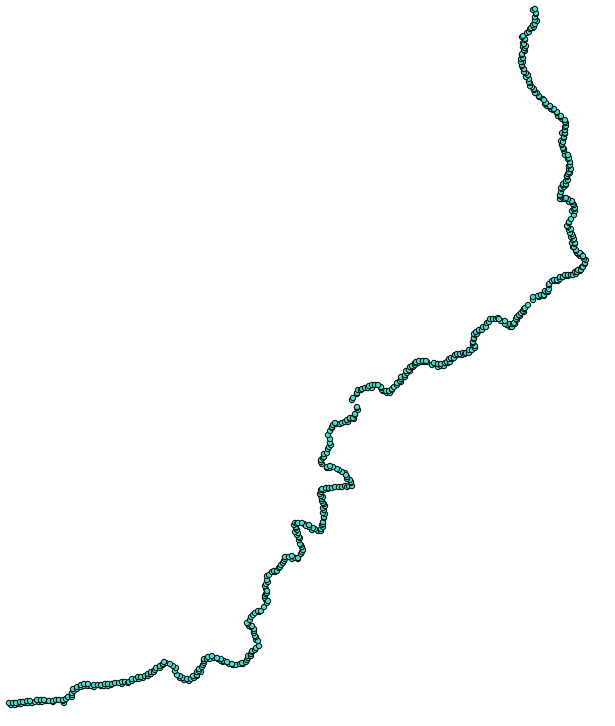

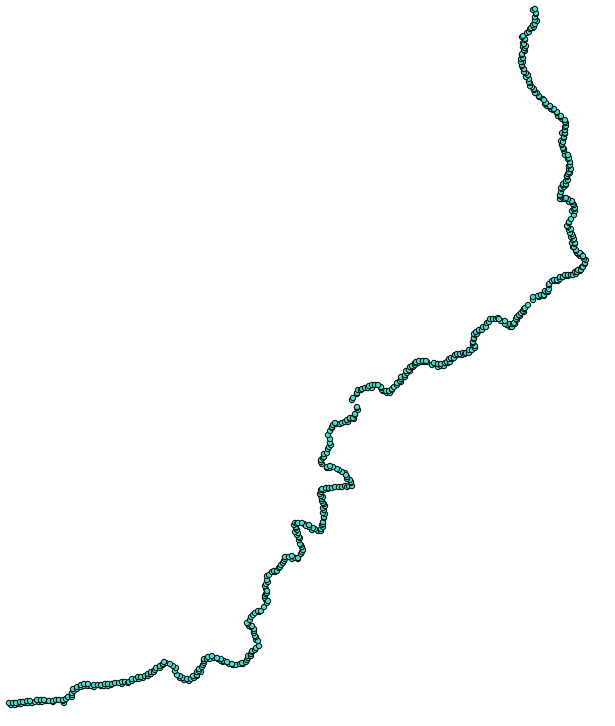

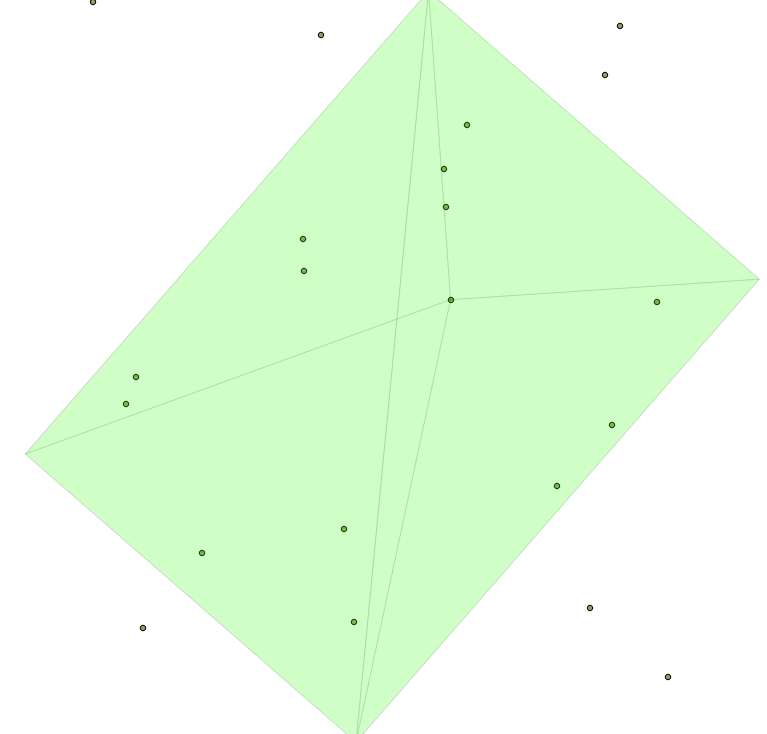

In addition, a process was undertaken to generate centerlines for polygon features such as streams, which are effectively linear features, as follows:

Hence, we have three separate but related datasets:

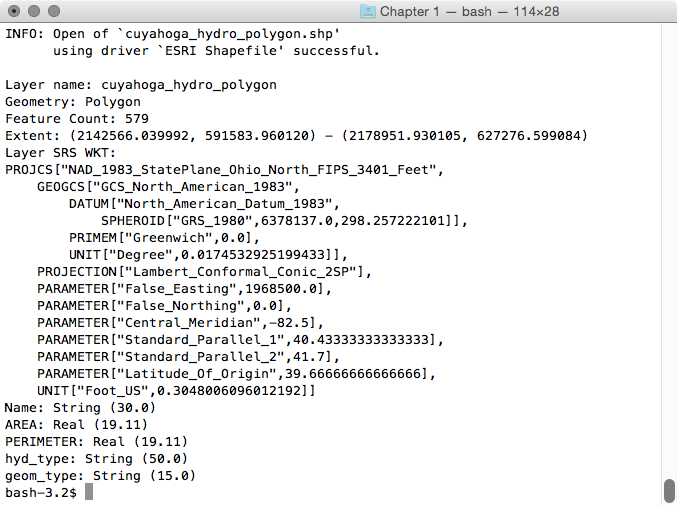

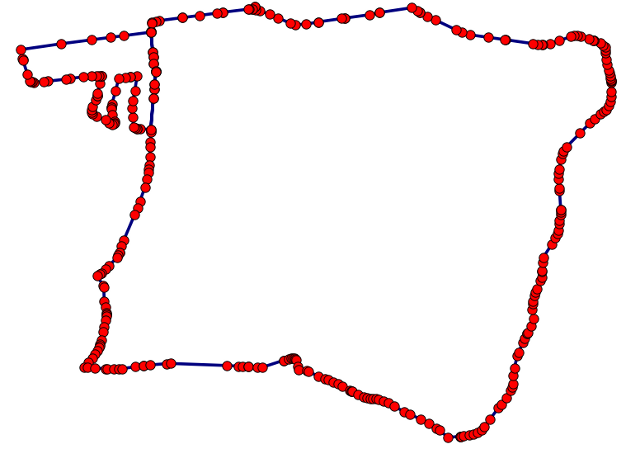

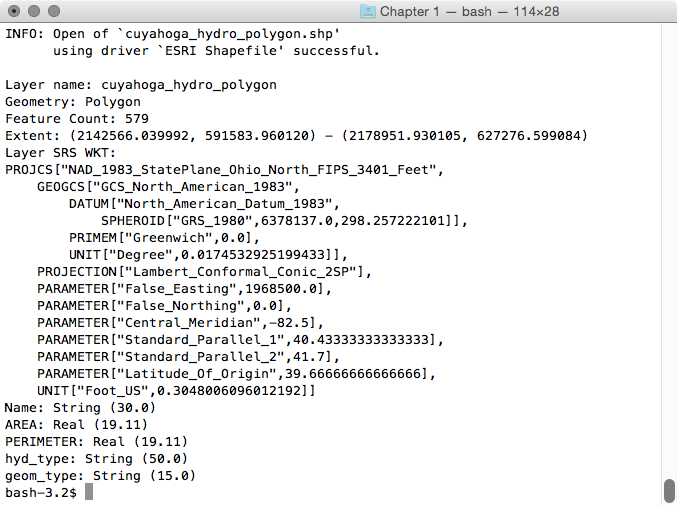

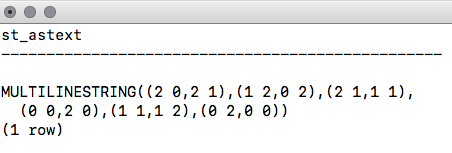

Now, let us look at the structure of the tabular data. Unzip the hydrology file from the book repository and go to that directory. The ogrinfo utility can help us with this, as shown in the following command:

> ogrinfo cuyahoga_hydro_polygon.shp -al -so

The output is as follows:

Executing this query on each of the shapefiles, we see the following fields that are common to all the shapefiles:

It is by understanding our common fields that we can apply inheritance to completely structure our data.

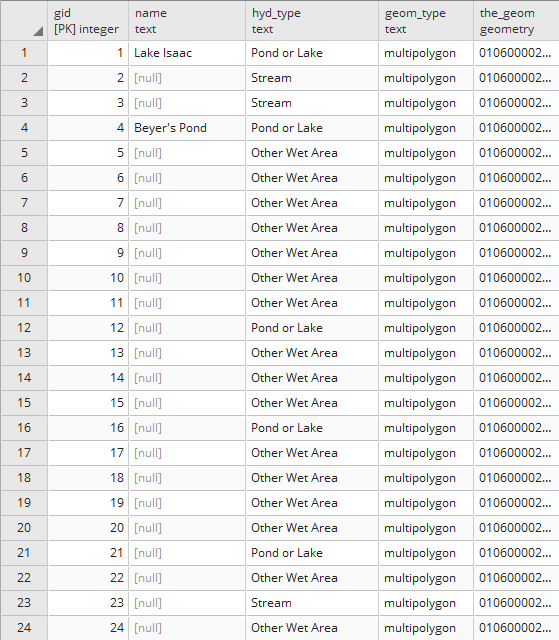

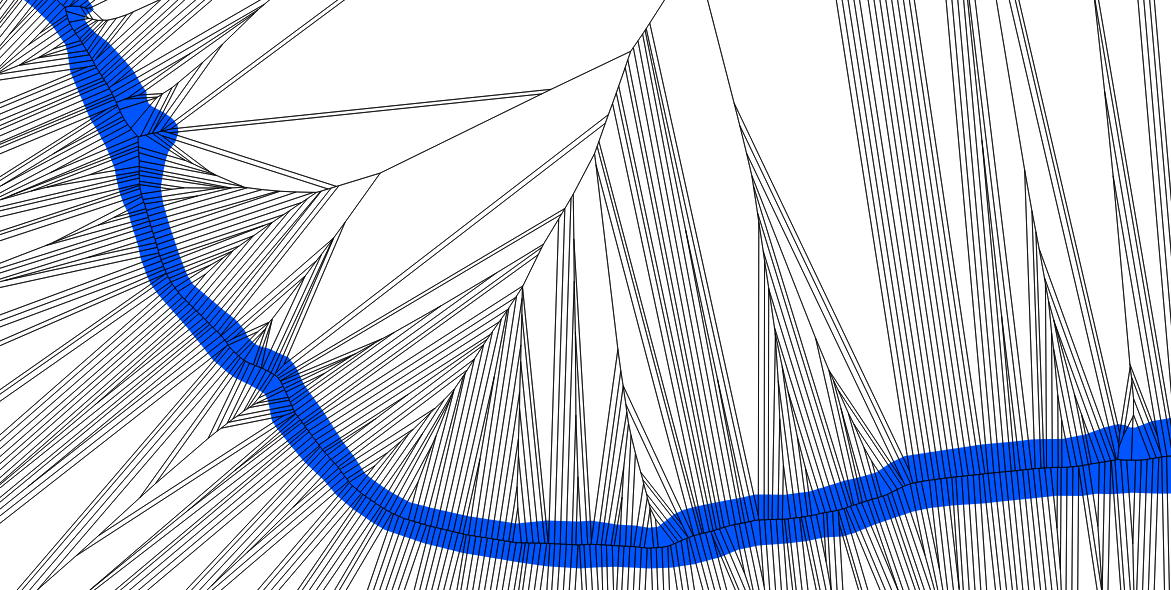

Now that we know our common fields, creating an inheritance model is easy. First, we will create a parent table with the fields common to all the tables, using the following query:

CREATE TABLE chp02.hydrology ( gid SERIAL PRIMARY KEY, "name" text, hyd_type text, geom_type text, the_geom geometry );

If you are paying attention, you will note that we also added a geometry field as all of our shapefiles implicitly have this commonality. With inheritance, every record inserted in any of the child tables will also be saved in our parent table, only these records will be stored without the extra fields specified for the child tables.

To establish inheritance for a given table, we need to declare only the additional fields that the child table contains using the following query:

CREATE TABLE chp02.hydrology_centerlines ( "length" numeric ) INHERITS (chp02.hydrology); CREATE TABLE chp02.hydrology_polygon ( area numeric, perimeter numeric ) INHERITS (chp02.hydrology); CREATE TABLE chp02.hydrology_linestring ( sinuosity numeric ) INHERITS (chp02.hydrology_centerlines);

Now, we are ready to load our data using the following commands:

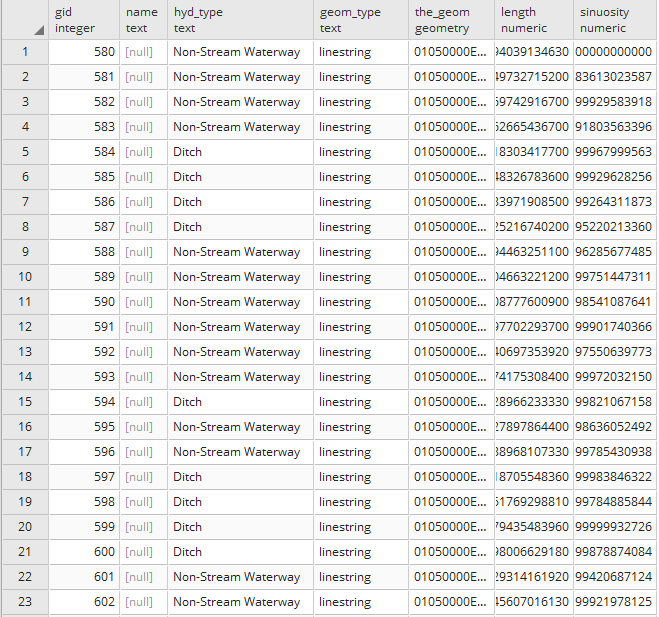

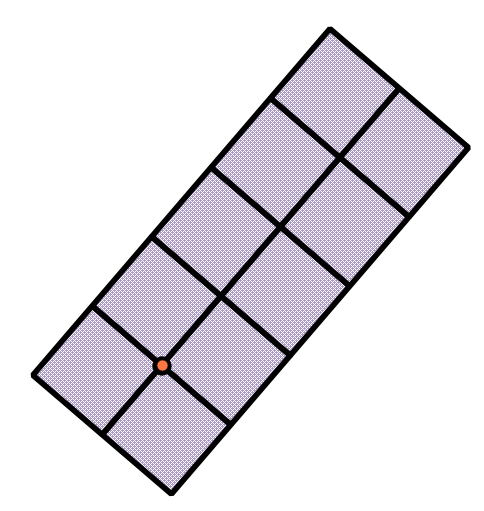

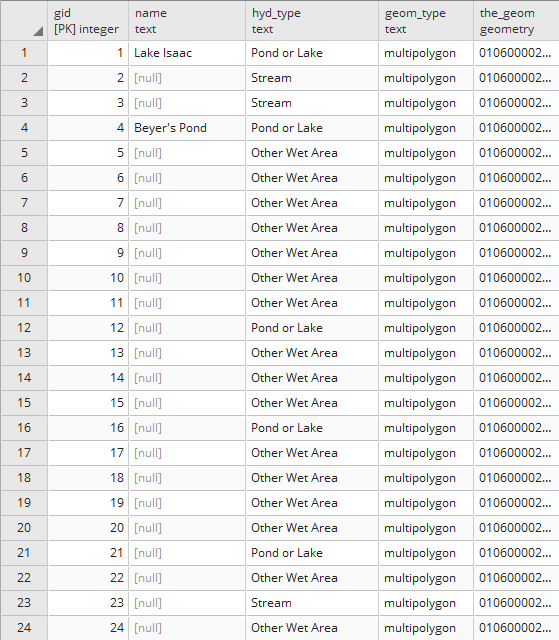

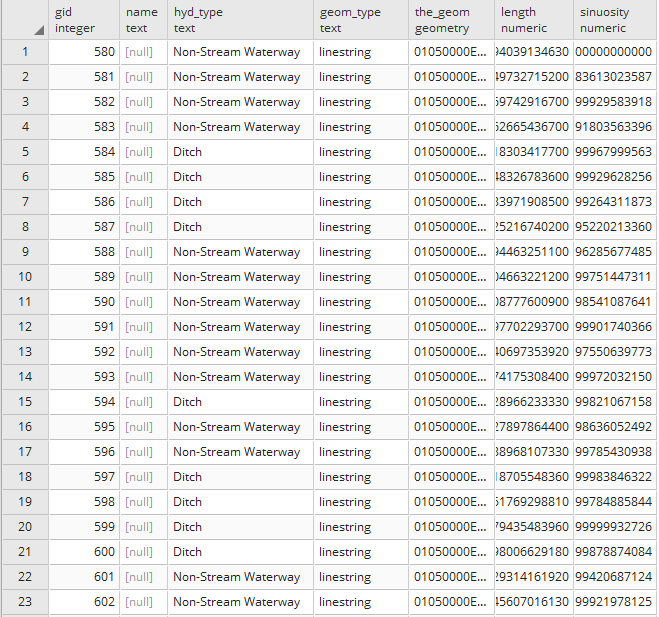

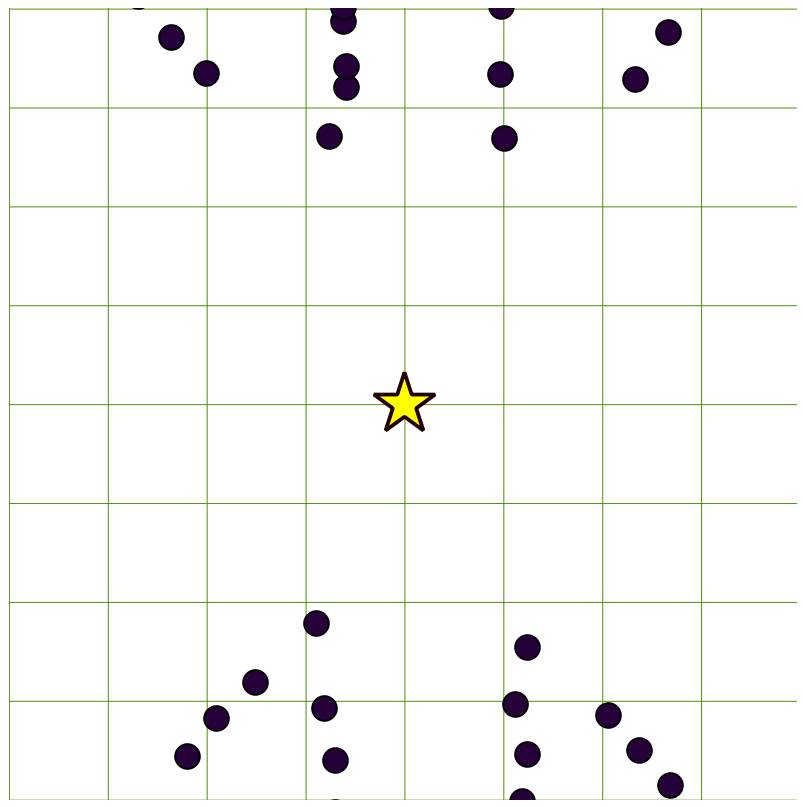

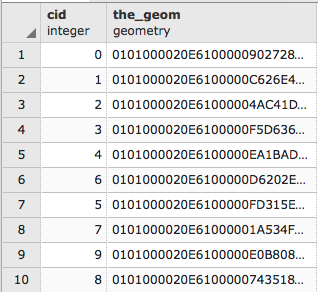

If we view our parent table, we will see all the records in all the child tables. The following is a screenshot of fields in hydrology:

Compare that to the fields available in hydrology_linestring that will reveal specific fields of interest:

PostgreSQL table inheritance allows us to enforce essentially hierarchical relationships between tables. In this case, we leverage inheritance to allow for commonality between related datasets. Now, if we want to query data from these tables, we can query directly from the parent table as follows, depending on whether we want a mix of geometries or just a targeted dataset:

SELECT * FROM chp02.hydrology

From any of the child tables, we could use the following query:

SELECT * FROM chp02.hydrology_polygon

It is possible to extend this concept in order to leverage and optimize storage and querying by using the CHECK constrains in conjunction with inheritance. For more info, see the Extending inheritance – table partitioning recipe.

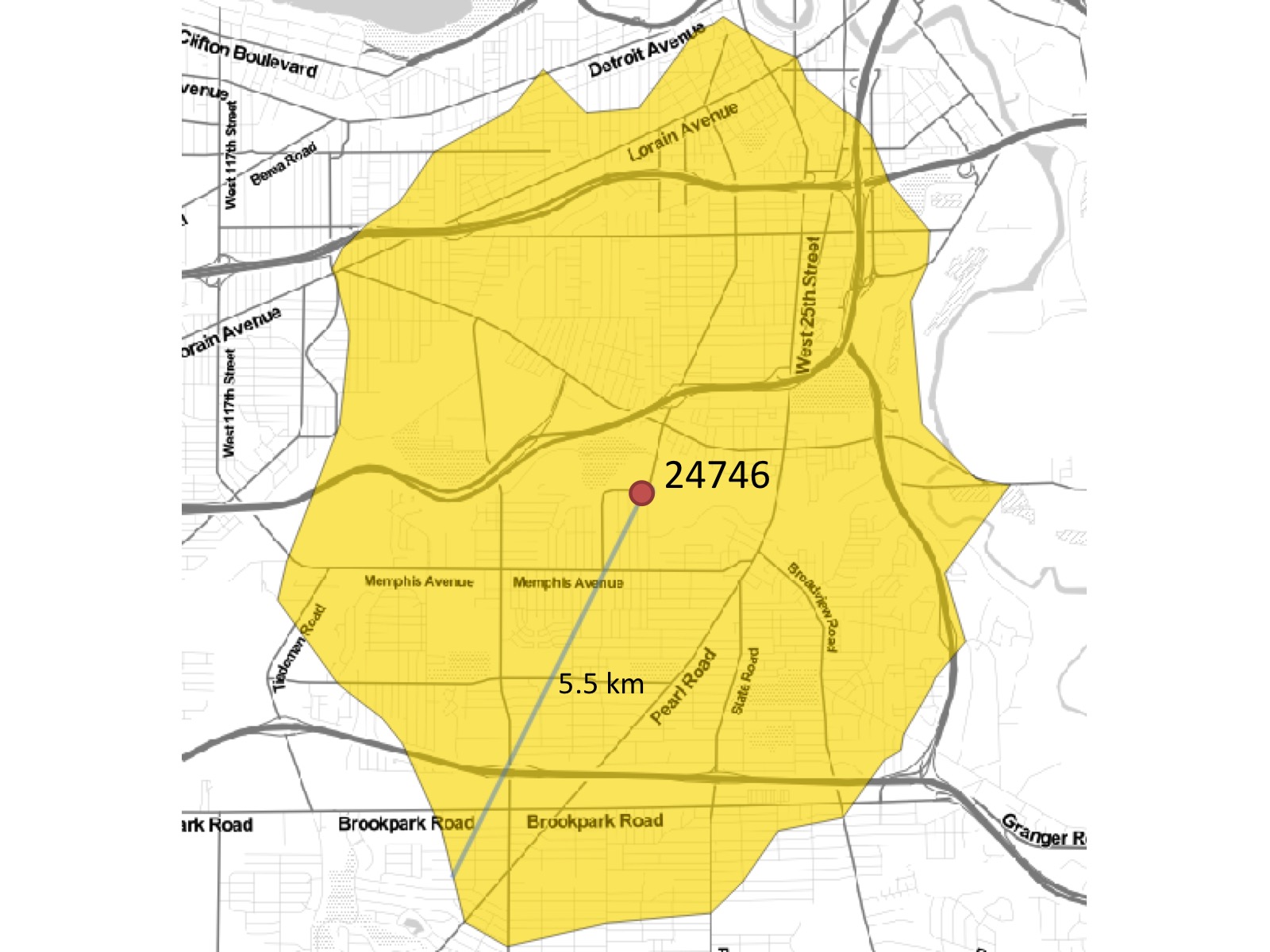

Table partitioning is an approach specific to PostgreSQL that extends inheritance to model tables that typically do not vary from each other in the available fields, but where the child tables represent logical partitioning of the data based on a variety of factors, be it time, value ranges, classifications, or in our case, spatial relationships. The advantages of partitioning include improved query performance due to smaller indexes and targeted scans of data, bulk loads, and deletes that bypass the costs of vacuuming. It can thus be used to put commonly used data on faster and more expensive storage, and the remaining data on slower and cheaper storage. In combination with PostGIS, we get the novel power of spatial partitioning, which is a really powerful feature for large datasets.