Copyright © 2018 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing or its dealers and distributors, will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

Acquisition Editor: Ben Renow-Clarke

Content Development Editor: Monika Sangwan

Technical Editor: Gaurav Gavas

Copy Editor: Tom Jacob

Project Coordinator: Suzanne Coutinho

Proofreader: Safis Editing

Indexer: Rekha Nair

Production Coordinator: Shantanu N. Zagade

First published: March 2018

Production reference: 1290318

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham

B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78839-393-5

Mapt is an online digital library that gives you full access to over 5,000 books and videos, as well as industry leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career. For more information, please visit our website.

Spend less time learning and more time coding with practical eBooks and Videos from over 4,000 industry professionals

Improve your learning with Skill Plans built especially for you

Get a free eBook or video every month

Mapt is fully searchable

Copy and paste, print, and bookmark content

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at service@packtpub.com for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters, and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

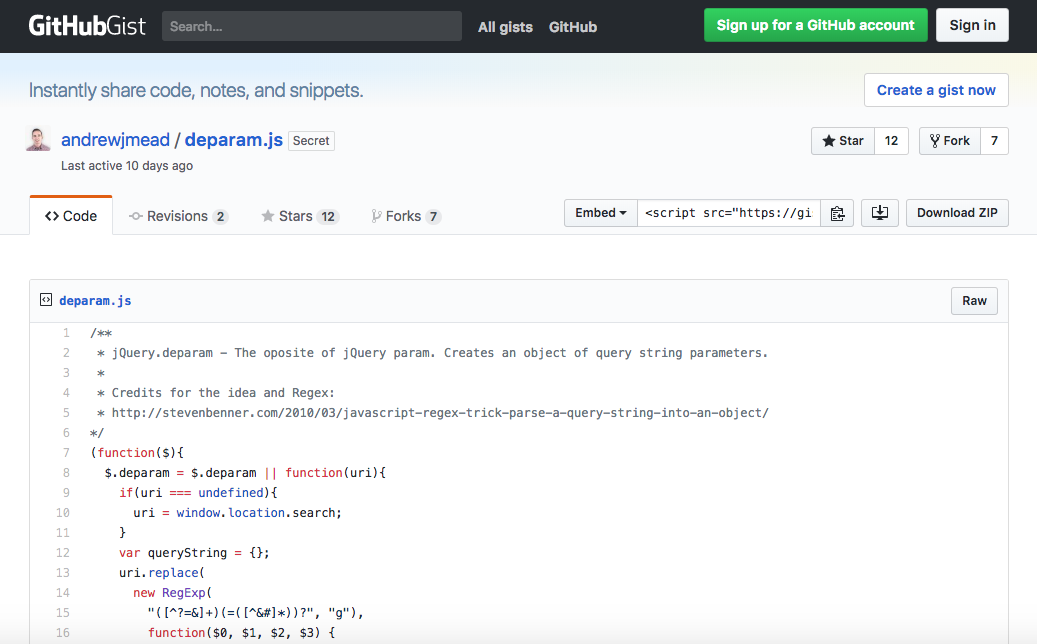

Andrew Mead is a full-stack developer living in beautiful Philadelphia! He launched his first Udemy course in 2014 and had a blast teaching and helping others. Since then, he has launched three courses with over 21,000 students and over 1,900 5-star reviews.

Andrew currently teaches Node.js, Gulp, and React. Before he started teaching, he created a web app development company. He has helped companies of all sizes launch production web applications to their customers. He has had the honor of working with awesome companies such as Siemens, Mixergy, and Parkloco. He has a Computer Science degree from Temple University, and he has been programming for just over a decade. He loves creating, programming, launching, learning, teaching, and biking.

If you're interested in becoming an author for Packt, please visit authors.packtpub.com and apply today. We have worked with thousands of developers and tech professionals, just like you, to help them share their insight with the global tech community. You can make a general application, apply for a specific hot topic that we are recruiting an author for, or submit your own idea.

Welcome to Advanced Node.js Development. This book is packed with a ton of content, projects, challenges, and real-world examples, all designed to teach you Node by doing. This means you'll be getting your hands dirty early on in the upcoming chapters writing some code, and you'll be writing code for every project. You will be writing every line of code that powers our applications. Now, we would require a text editor for this book.

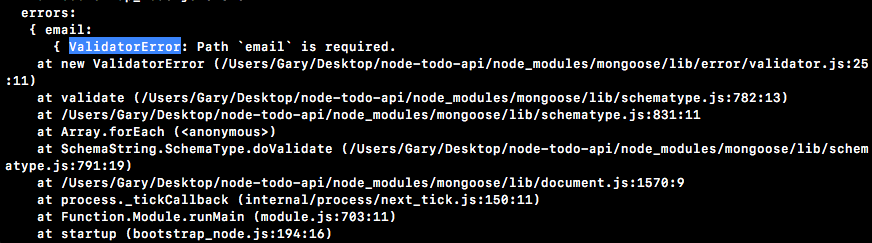

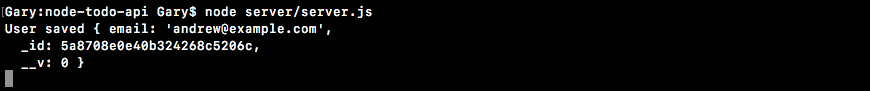

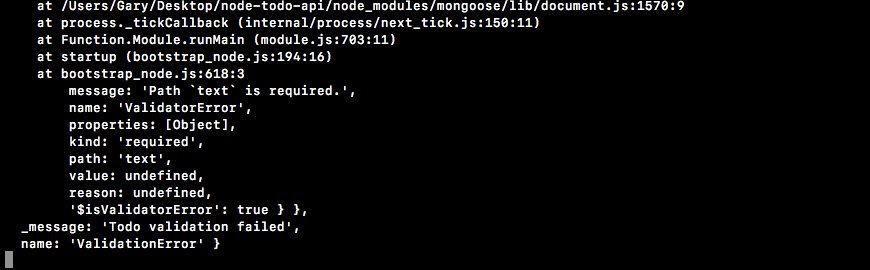

All the projects in the book are fun to build and they were designed to teach you everything required to launch your own Node app, from planning to development and testing to deploying. Now, as you launch these different Node applications and move through the book, you will run into errors, which is bound to happen. Maybe something doesn't get installed as expected, or maybe you try to run an app and instead of getting the expected output, you get a really long obscure error message. Don't worry, I am there to help. I'll show you tips and tricks to get pass through those errors in the chapters. Let's go ahead and get to it.

This book targets anyone looking to launch their own Node applications, switch careers, or freelance as a Node developer. You should have a basic understanding of JavaScript in order to follow this book.

Chapter 1, Getting Set Up, will be a very basic setup for your local environments. We'll learn to install MongoDB and Robomongo.

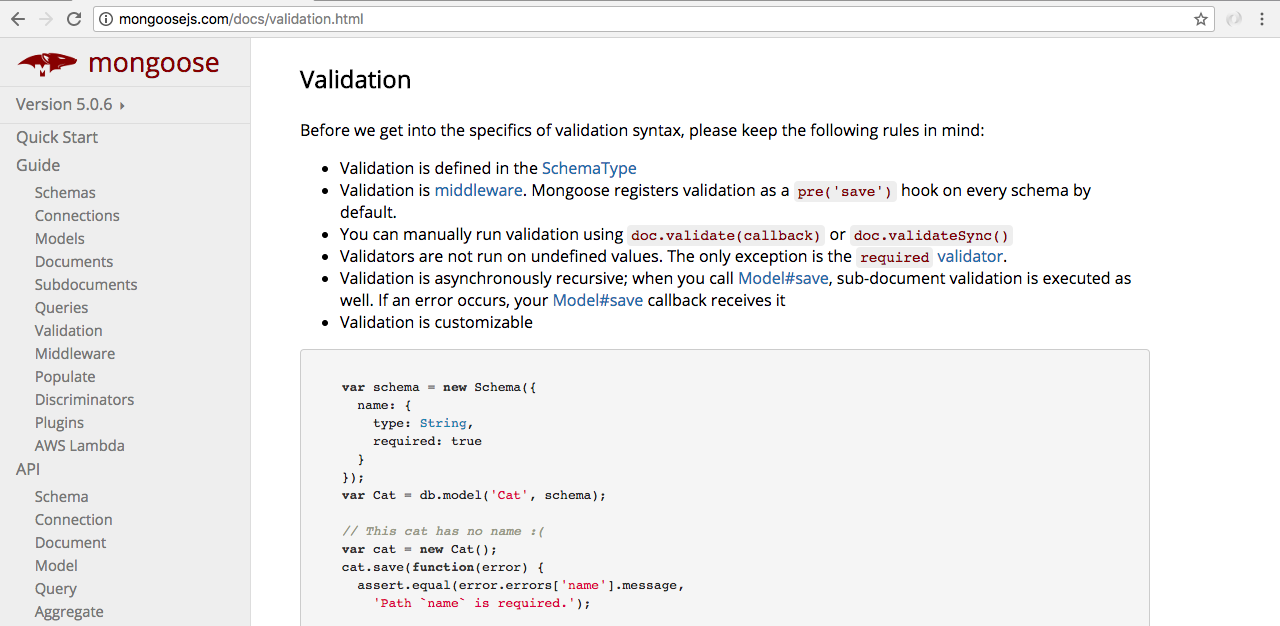

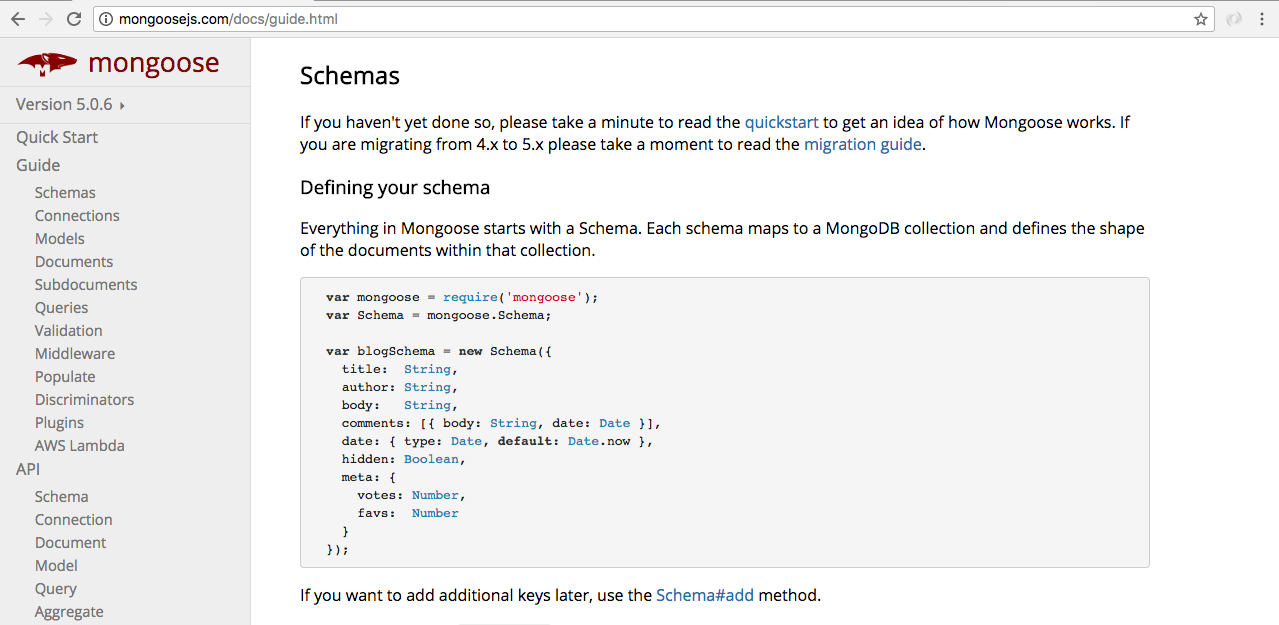

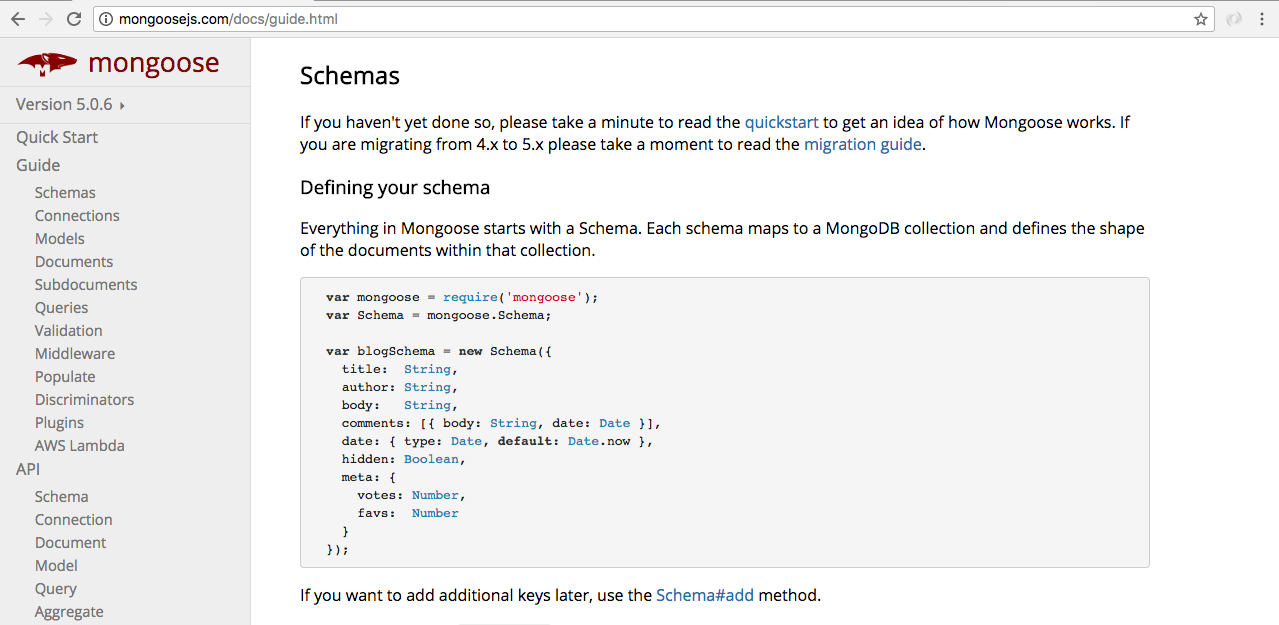

Chapter 2, MongoDB, Mongoose, and REST APIs – Part 1, will help you learn how to connect your Node applications to the MongoDB database you've been running on your local machine.

Chapter 3, MongoDB, Mongoose, and REST APIs – Part 2, will help you start playing with Mongoose and connect to our MongoDB database.

Chapter 4, MongoDB, Mongoose, and REST APIs – Part 3, will resolve queries and ID validation after playing with Mongoose.

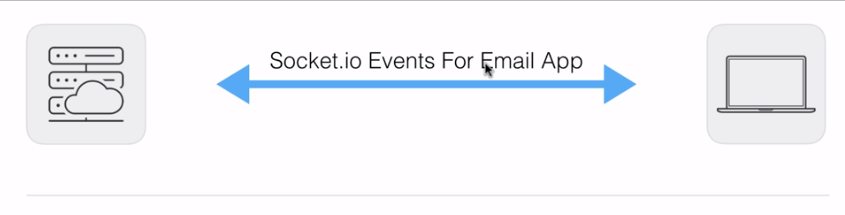

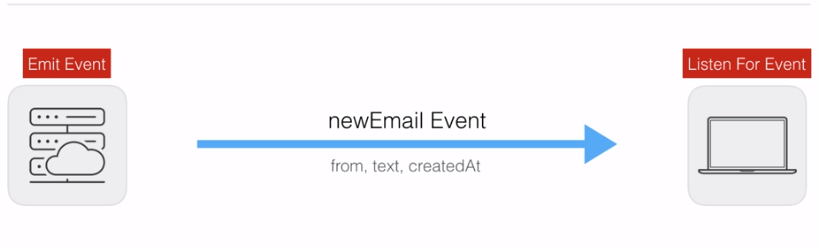

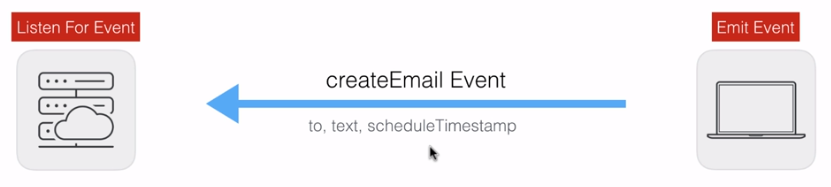

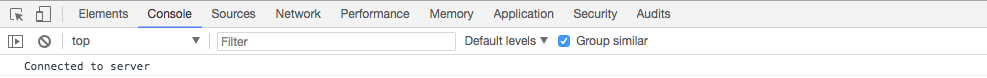

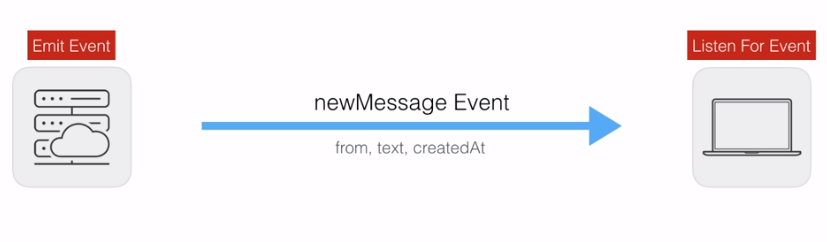

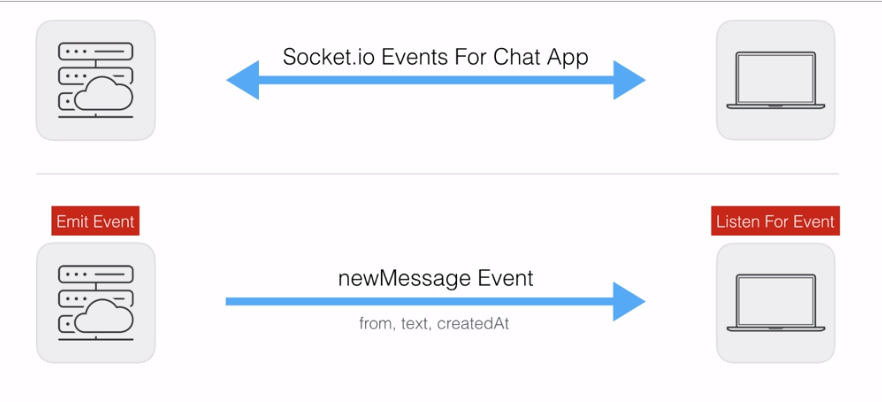

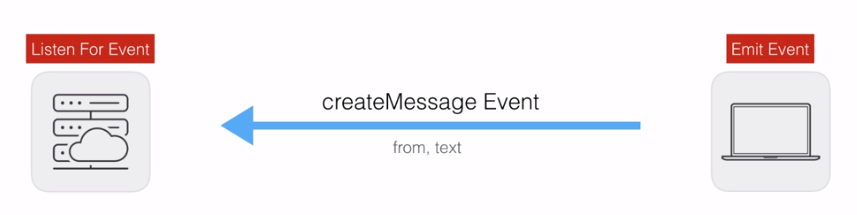

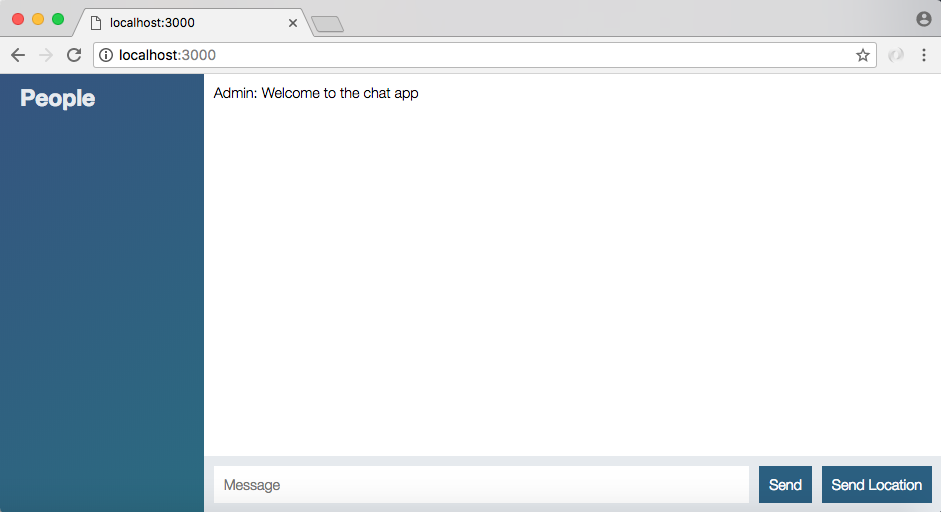

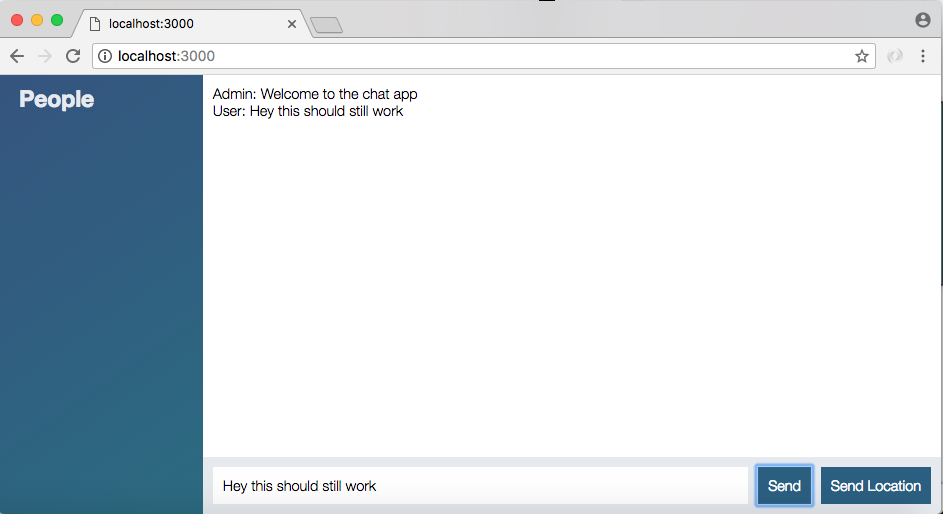

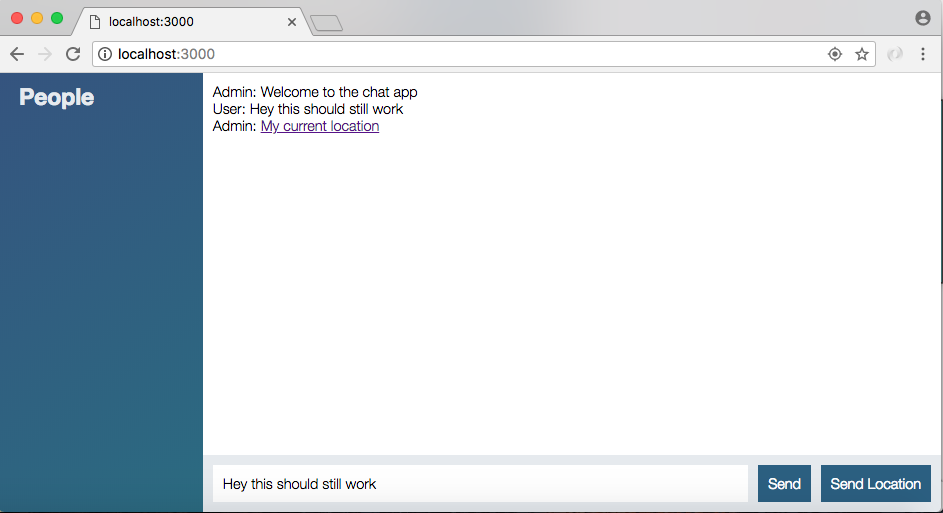

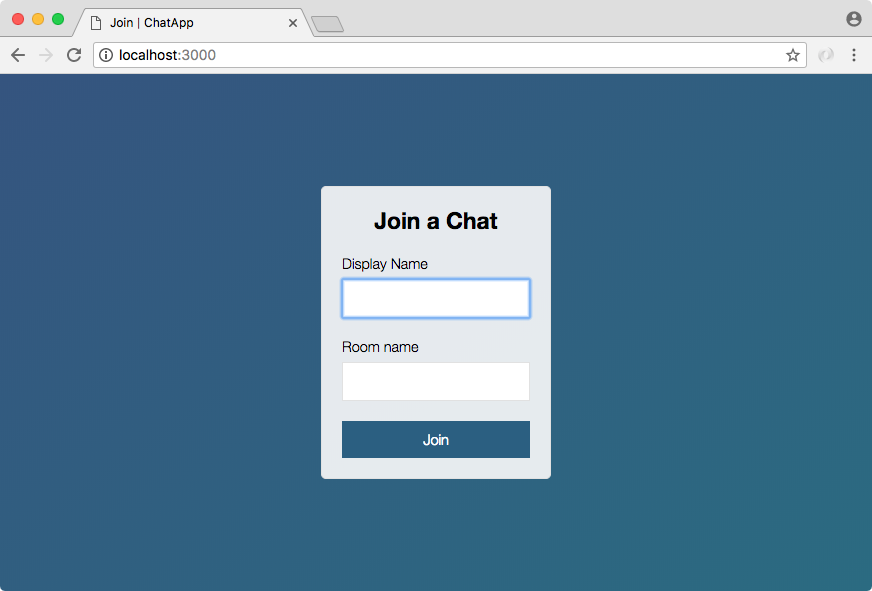

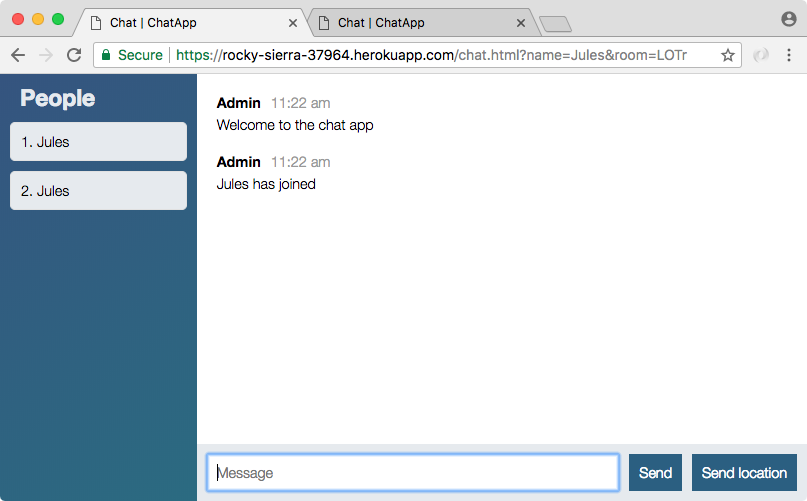

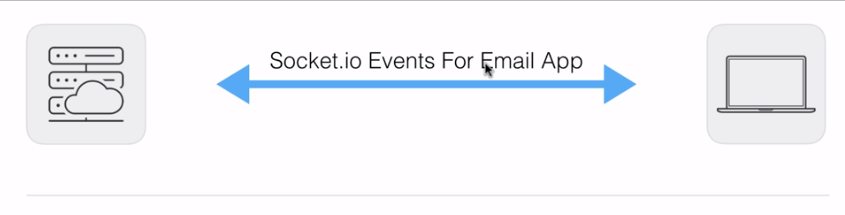

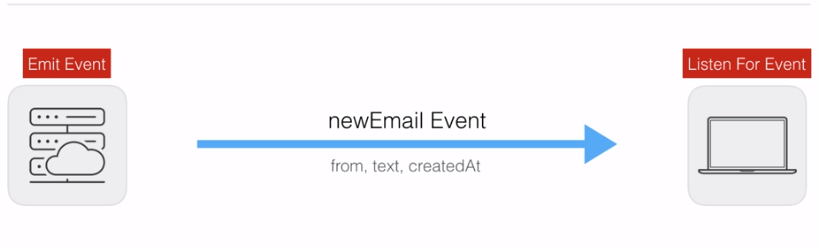

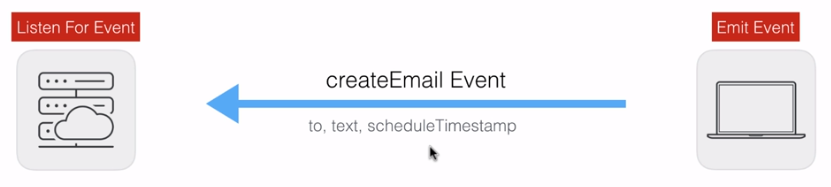

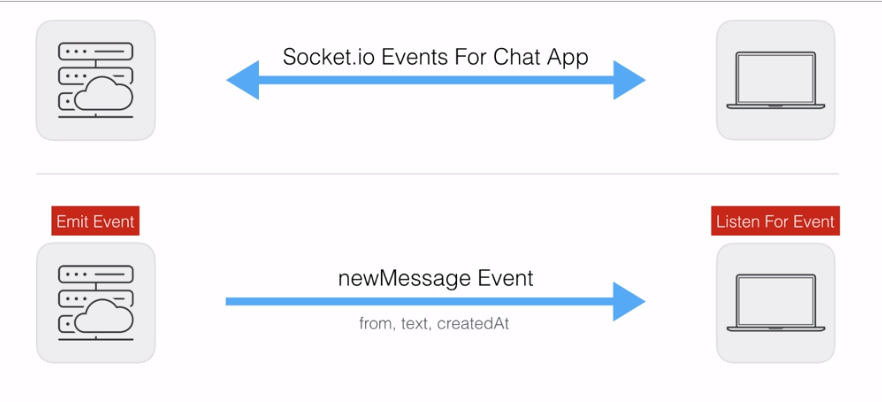

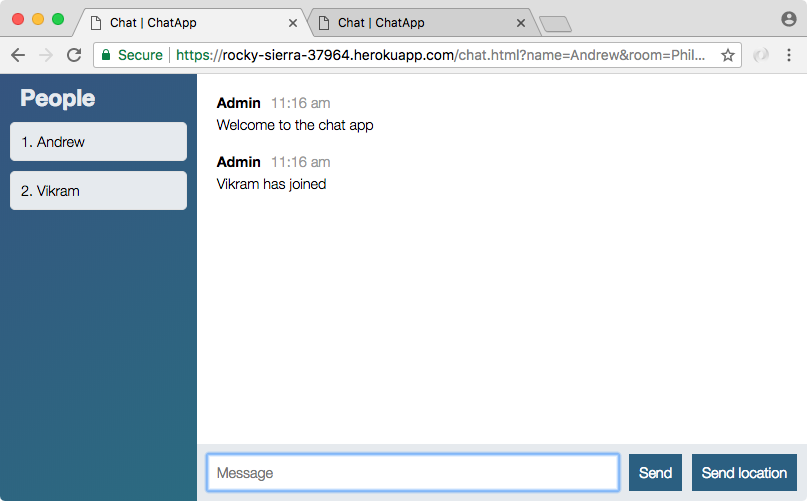

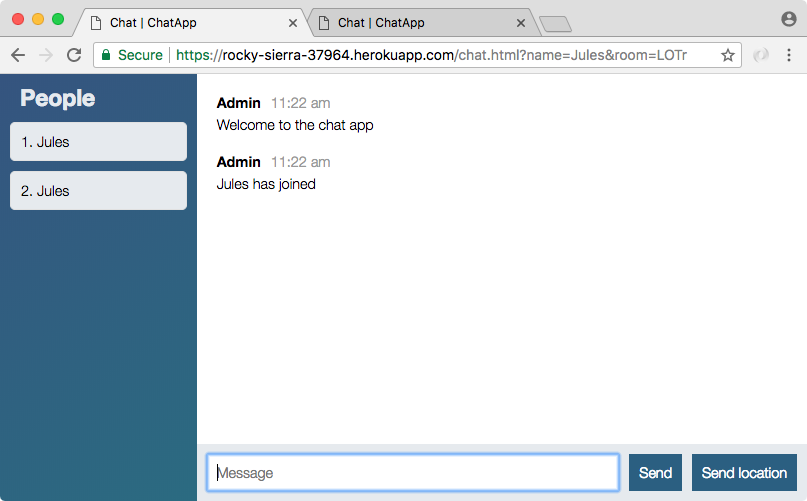

Chapter 5, Real-Time Web Apps with Socket.io, will help you learn in detail about Socket.io and WebSockets, help you and create real-time web applications.

Chapter 6, Generating newMessage and newLocationMessage, discusses how to generate text and gelocation messages.

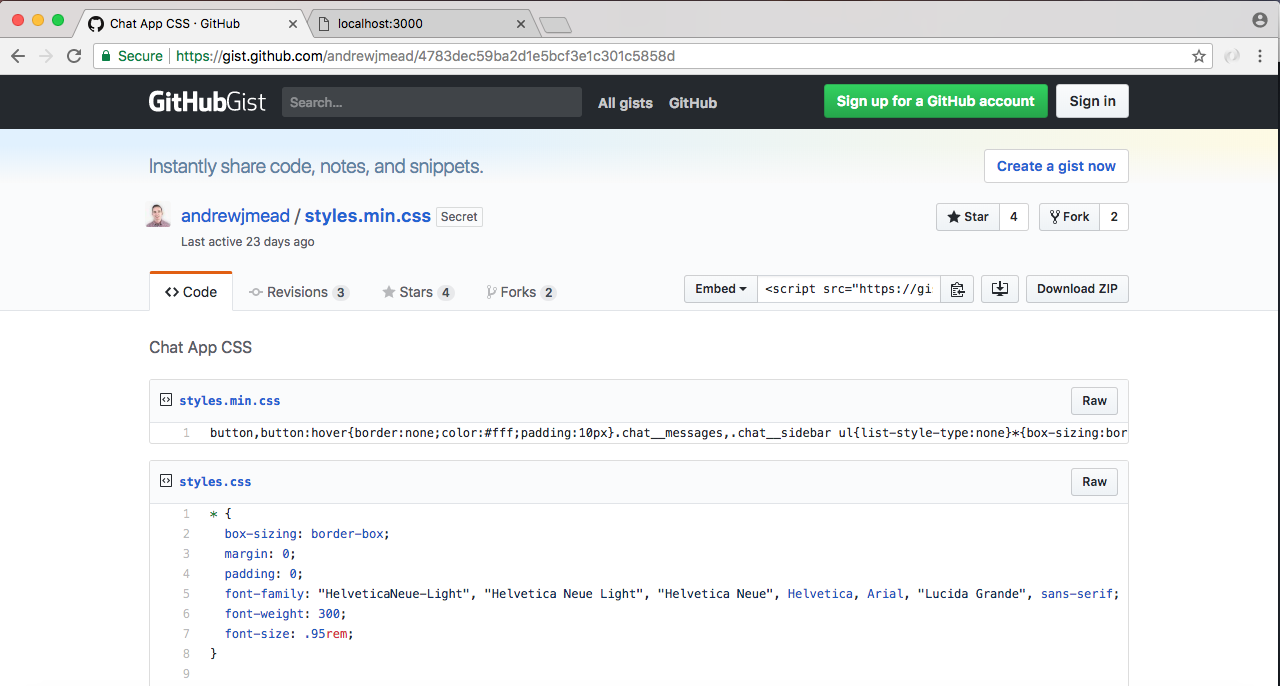

Chapter 7, Styling Our Chat Page as a Web App, continues our discussion on styling our chat page and make it look more like a real web application.

Chapter 8, The Join Page and Passing Room Data, continues our discussion about the chat page and look into the join page and passing room data.

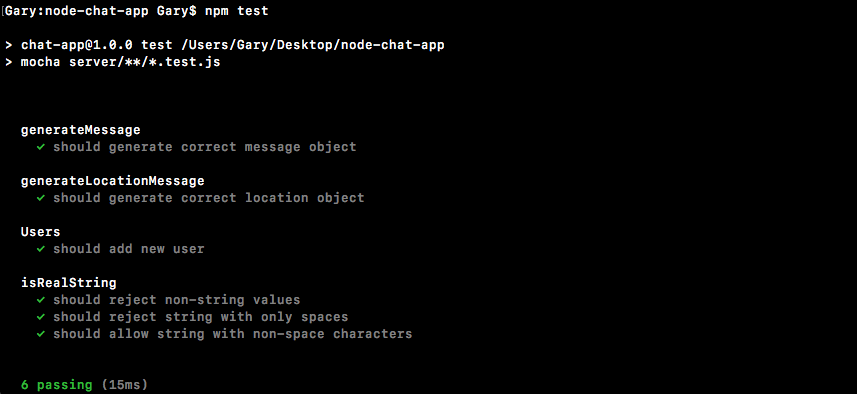

Chapter 9, ES7 classes, will help you learn the ES6 class syntax and using it creating user's class and some other methods.

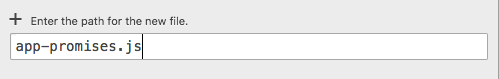

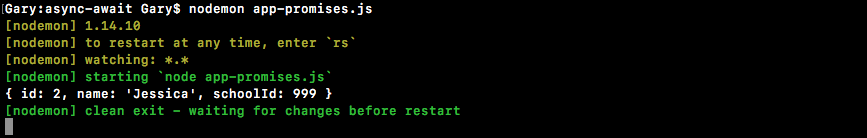

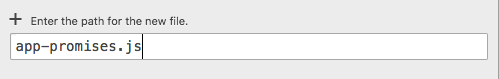

Chapter 10, Async/Await Project Setup, will walk you through the process of learning how async/await works.

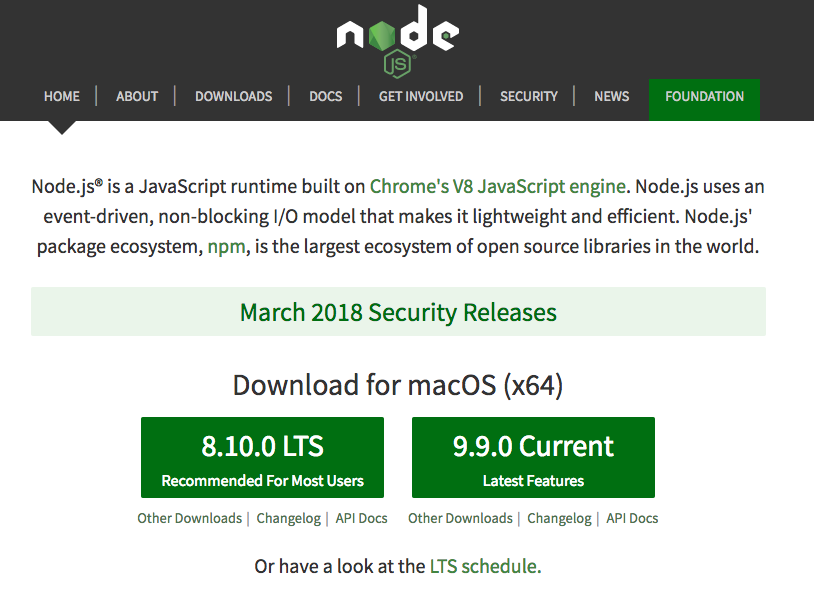

To run the projects in this book, you will need the following:

We'll see the rest of the requirements along the course of the book.

You can download the example code files for this book from your account at www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files emailed directly to you.

You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

The code bundle for the book is also hosted on GitHub at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/Advanced-Node.js-Development. We also have other code bundles from our rich catalog of books and videos available at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/. Check them out!

We also provide a PDF file that has color images of the screenshots/diagrams used in this book. You can download it here: http://www.packtpub.com/sites/default/files/downloads/AdvancedNode.jsDevelopment_ColorImages.pdf.

There are a number of text conventions used throughout this book.

CodeInText: Indicates code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles. Here is an example: "Mount the downloaded WebStorm-10*.dmg disk image file as another disk in your system."

A block of code is set as follows:

html, body, #map {

height: 100%;

margin: 0;

padding: 0

}

When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

[default]

exten => s,1,Dial(Zap/1|30)

exten => s,2,Voicemail(u100)

exten => s,102,Voicemail(b100)

exten => i,1,Voicemail(s0)

Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

$ cd css

Bold: Indicates a new term, an important word, or words that you see onscreen. For example, words in menus or dialog boxes appear in the text like this. Here is an example: "Select System info from the Administration panel."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome.

General feedback: Email feedback@packtpub.com and mention the book title in the subject of your message. If you have questions about any aspect of this book, please email us at questions@packtpub.com.

Errata: Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you have found a mistake in this book, we would be grateful if you would report this to us. Please visit www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details.

Piracy: If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, we would be grateful if you would provide us with the location address or website name. Please contact us at copyright@packtpub.com with a link to the material.

If you are interested in becoming an author: If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, please visit authors.packtpub.com.

Please leave a review. Once you have read and used this book, why not leave a review on the site that you purchased it from? Potential readers can then see and use your unbiased opinion to make purchase decisions, we at Packt can understand what you think about our products, and our authors can see your feedback on their book. Thank you!

For more information about Packt, please visit packtpub.com.

In this chapter, you'll get your local environment set up for the rest of the book. Whether you're on macOS, Linux, or Windows, we'll install MongoDB and Robomongo.

More specifically, we'll cover the following topics:

This section is for macOS and Linux users. If you are on Windows, I have written a separate section for you.

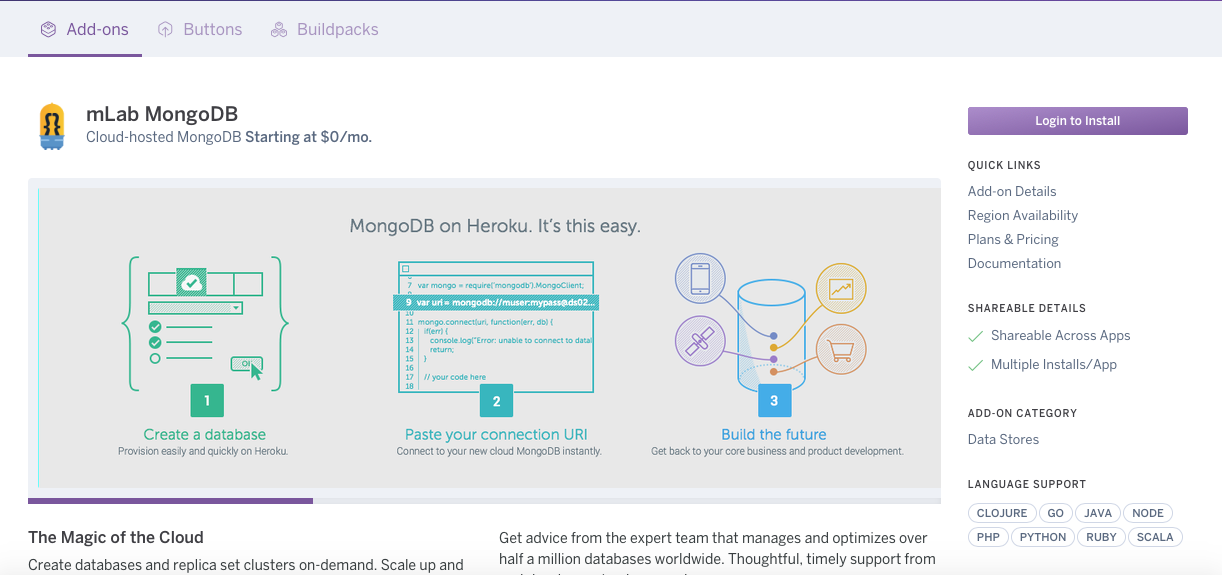

The first thing we'll do is to download and set up MongoDB, as this will be the database we will use. We'll be using a third-party service to host our database when we eventually deploy it to Heroku, but on our local machine we'll need to download MongoDB so that we can start up a database server. This will let us connect to it via our Node applications to read and write data.

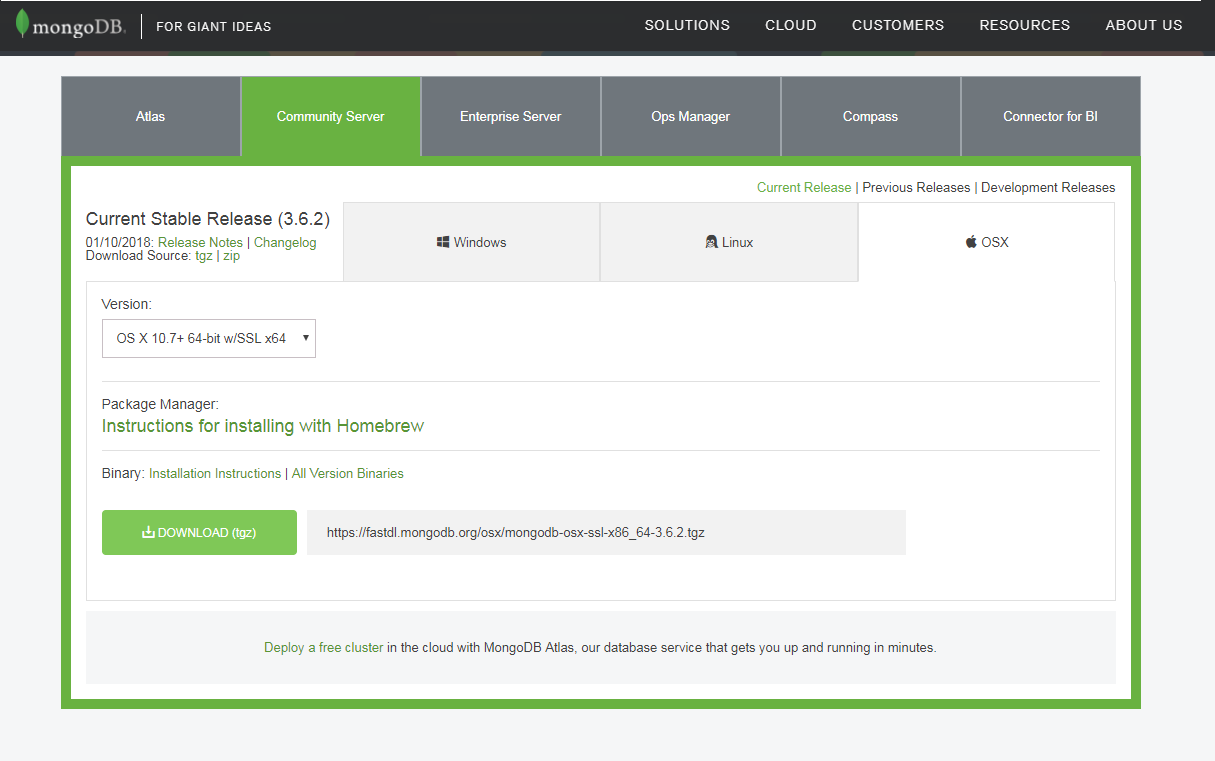

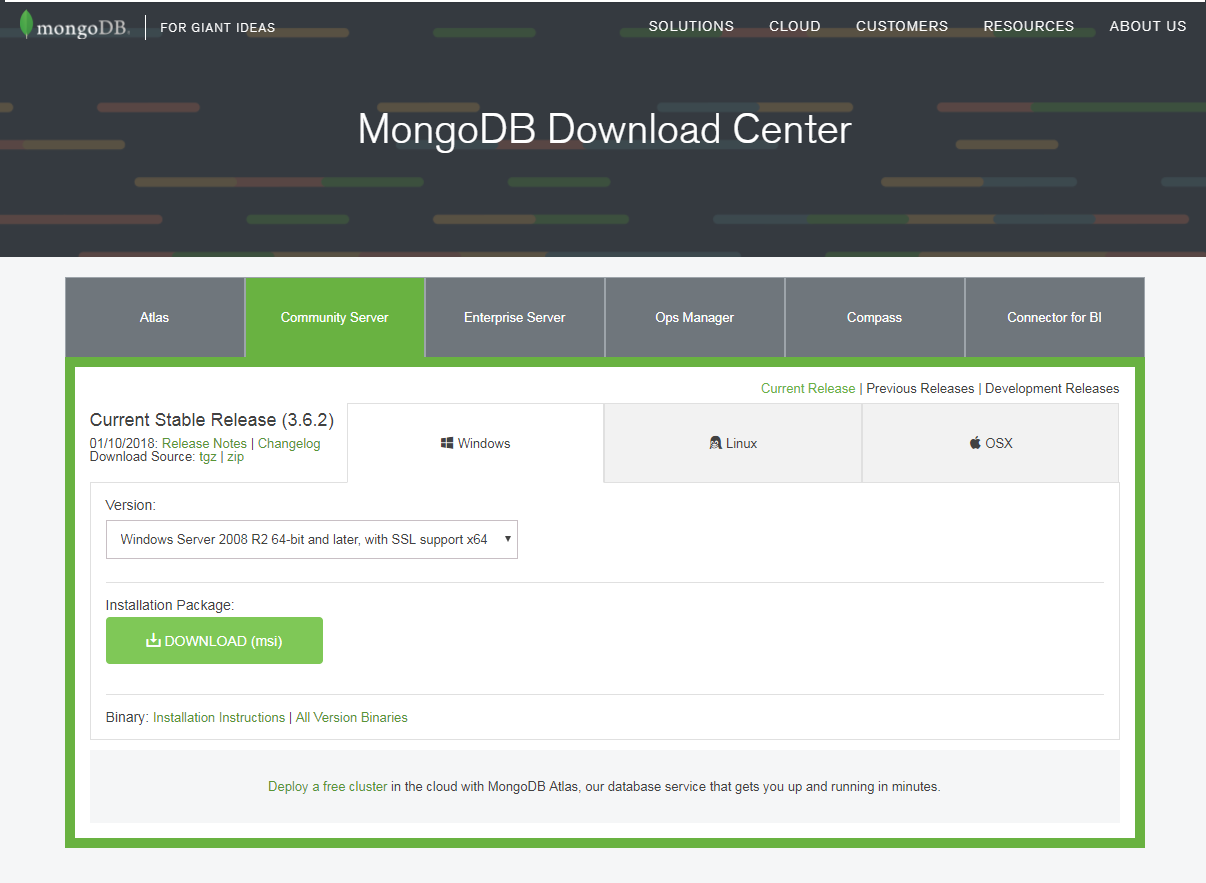

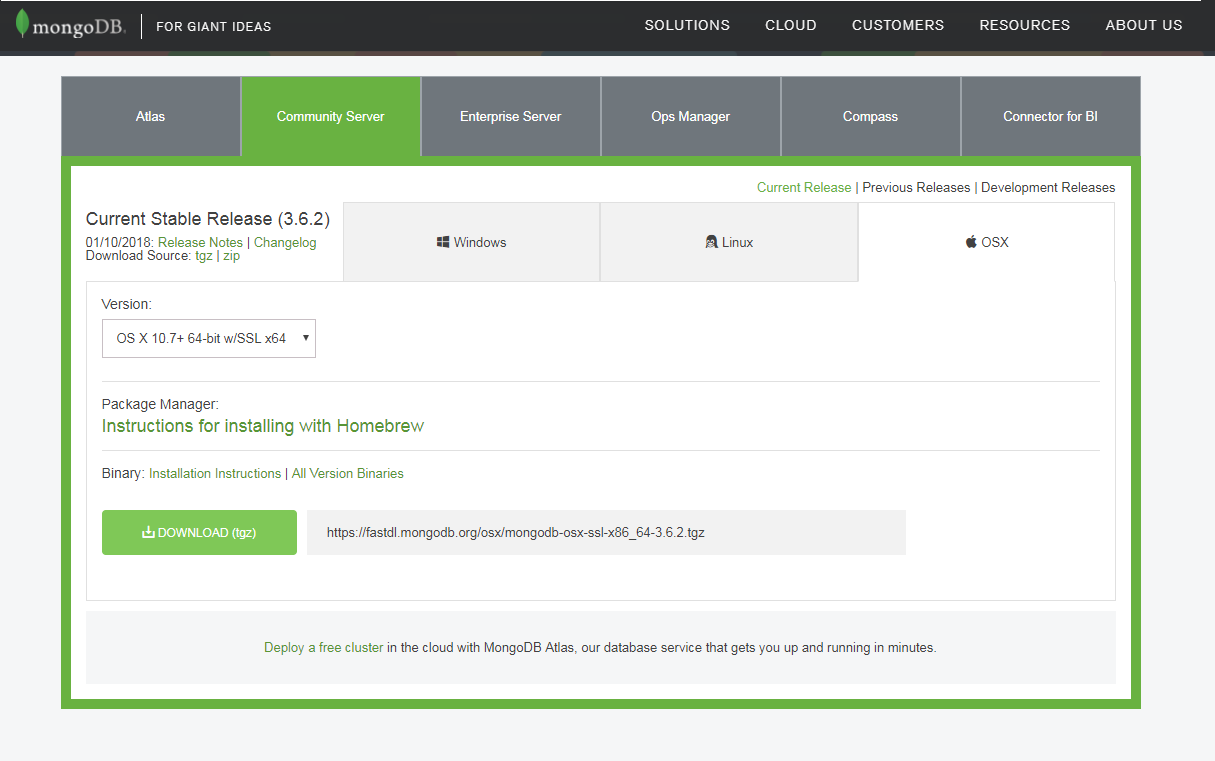

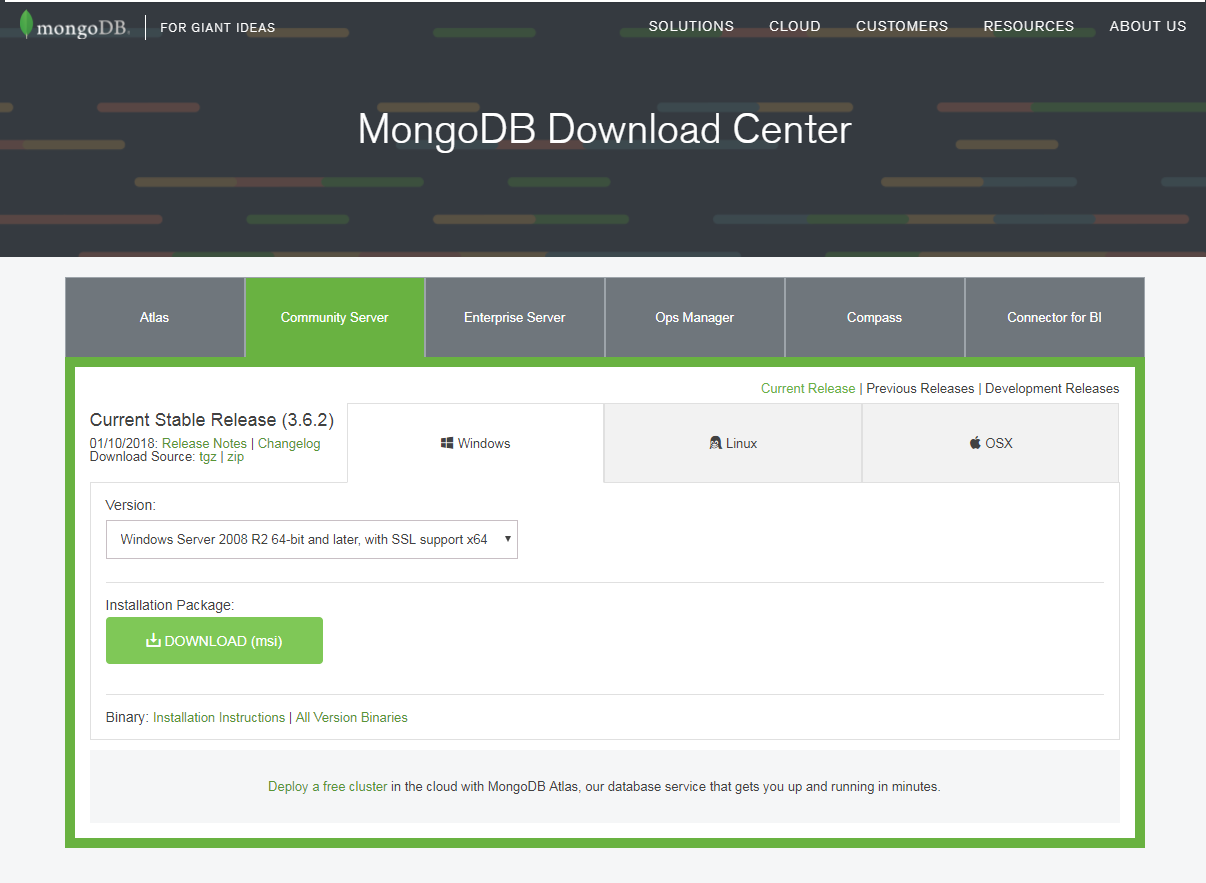

In order to grab the database, we'll head over to mongodb.com. Then we can go to the Download page and download the appropriate version.

On this page, scroll down and select Community Server; this is the one we'll be using. Also, there are options for different operating systems, whether it's Windows, Linux, macOS, or Solaris. I'm on macOS, so I'll use this download:

If you're on Linux, click on Linux; then go to the Version drop down and select the appropriate version. For example, if you're on Ubuntu 14.04, you can download the correct one from the Linux tab. Then, you can simply click on the Download button and follow along.

Next you can open it up. We'll just extract the directory, creating a brand new folder in the Downloads folder. If you're on Linux, you might need to manually extract the contents of that archive into the Downloads folder.

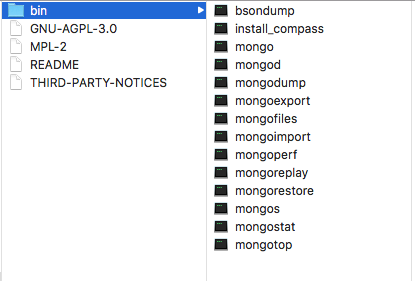

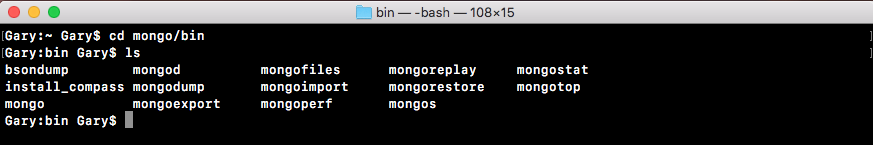

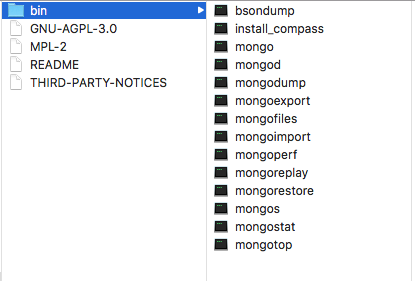

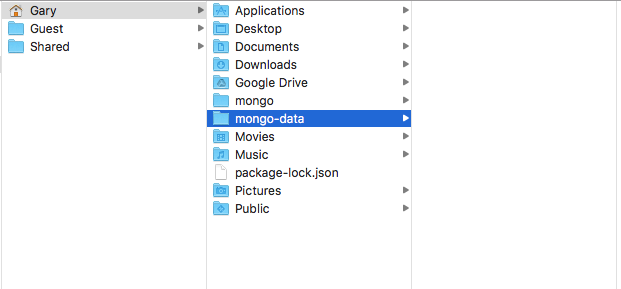

Now this folder contains a bin folder, and in there we have all of the executables that we need in order to do things such as connecting to the database and starting a database server:

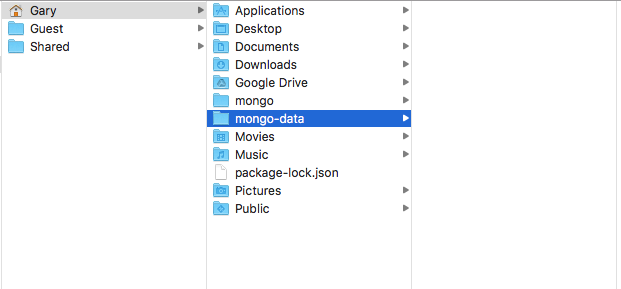

Before we go ahead and run any of them. We'll rename this directory to mongo and then move it into the user directory. You can see that now in the user directory, I have the mongo folder. We'll also create a brand new directory alongside of mongo called mongo-data, and this will store the actual data inside of the database:

So when we insert a new record into the Todos table, for example, that will live in the mongo-data folder. Once you have the mongo folder moved into the user directory and you have the new mongo-data folder, you are ready to actually run the database server from Terminal. I'll go into Terminal and navigate into that brand new mongo folder that is in the user directory, where I currently am, so I can cd into mongo, then I'll cd into the bin directory by tacking it on right there:

cd mongo/bin

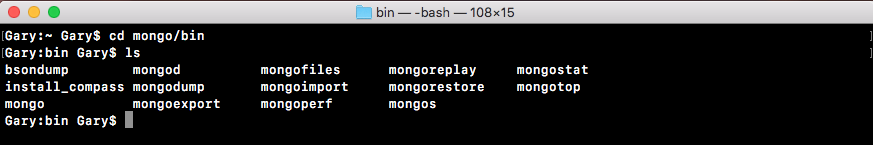

From here, we have a bunch of executables that we can run:

We have things such as bisondump and mongodump. In this section, we'll focus on: mongod, which will start up the database server, and mongo, which will let us connect to the server and run some commands. Just like when we type node we can run some JavaScript commands right in Terminal, when we type mongo, we'll be able to run some Mongo commands to insert, fetch, or do anything we like with the data.

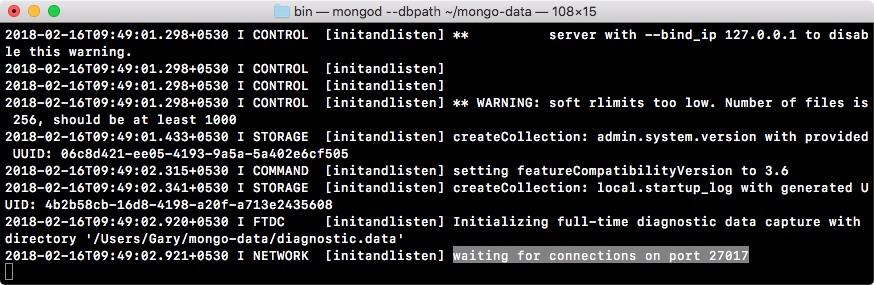

First up though, let's start up the database server. I'll use ./ to run a file in the current directory. The file we'll run is called mongod; also, we do need to provide one argument: the dbpath argument. The dbpath argument will get set equal to the path of the directory we just created, the mongo-data directory. I'll use ~ (the tilde) to navigate to the user directory, and then to /mongo-data, as shown here:

./mongod --dbpath ~/mongo-data

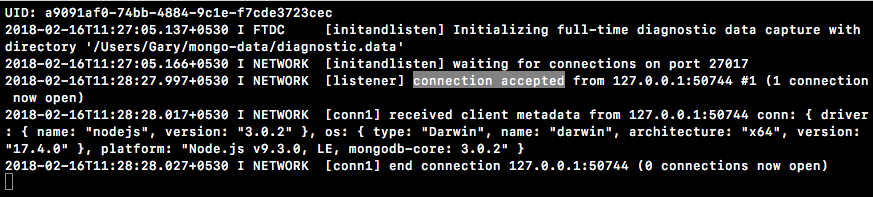

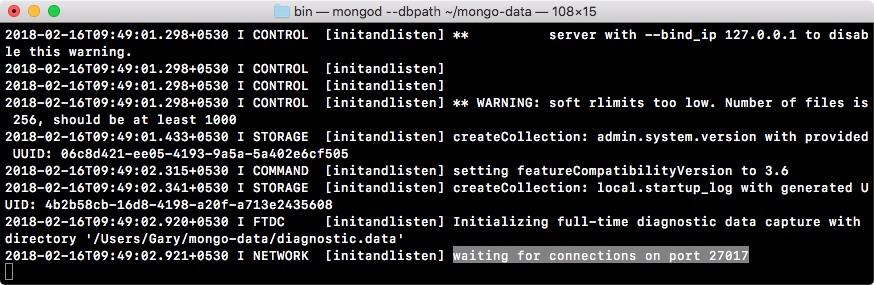

Running this command will start up the server. This will create an active connection, which we can connect to for manipulating our data. The last line that you see when you run the command should be, waiting for connections on port 27017:

If you see this, it means that your server is up and running.

Next up, let's open a new tab, which starts in the exact same directory, and this time around, instead of running mongod, we'll run the mongo file:

./mongo

When we run mongo, we open up a console. It connects to the database server we just started, and from here, we can start running some commands. These commands are just to test that things are working as expected. We'll be going over all of this in detail later in this section. For now though, we can access db.Todos, and then we'll call .insert to create a brand new Todo record. I'll call it like a function:

db.Todos.insert({})

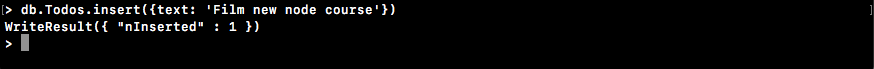

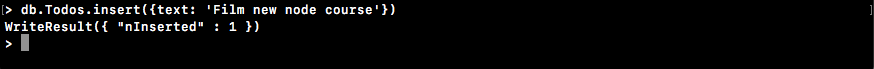

Next, inside of insert, we'll pass in our document. This will be the MongoDB document we want to create. For now, we'll keep things really simple. On our object, we'll specify one attribute, text, setting it equal to a string. Inside of quotes, type anything you want to do. I'll say Film new node course:

db.Todos.insert({text: 'Film new node course'})

With your command looking just like this, you can press enter, and you should get back a WriteResult object with an nInserted property, which is short for the number inserted: a value set to 1. This means that one new record was created, and that is fantastic!

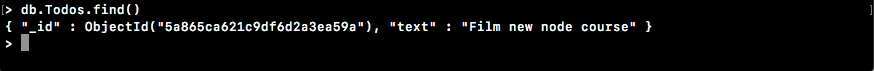

Now that we've inserted a record, let's fetch the record just to make sure that everything worked as expected.

Instead of calling insert, we'll call find without any arguments. We want to return every single item in the Todos collection:

db.Todos.find()

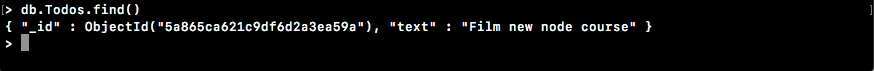

When I run this, what do we get? We get one object-looking thing back:

We have our text attribute set to the text that we provided, and we have an _id property. This is the unique identifier for each record, which we'll talk about later. As long as you're seeing the text property coming back to what you set, you are good to go.

We can shut down the mongo command. However, we will still leave the mongod command running because there's one more thing I want to install. It's called Robomongo, and it's a graphic user interface for managing your Mongo database. This will be really useful as you start playing around with Mongo. You'll be able to view the exact data saved in the database; you can manipulate it and do all sorts of stuff.

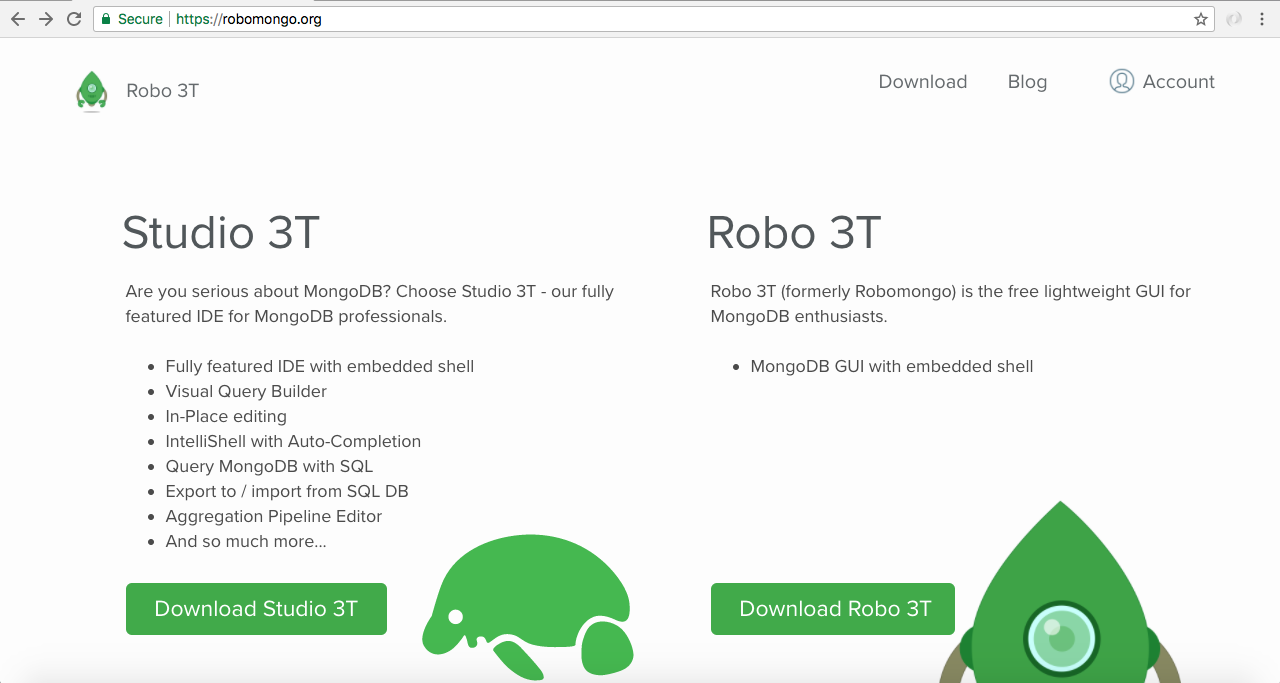

Over in Finder, we have our mongo-data directory, and you can see that there is a ton of stuff in here. This means that our data was successfully saved. All of the data is in this mongo-data directory. To download and install Robomongo, which is available for Linux, Windows and macOS, we'll head over to robomongo.org and grab the installer for our operating system:

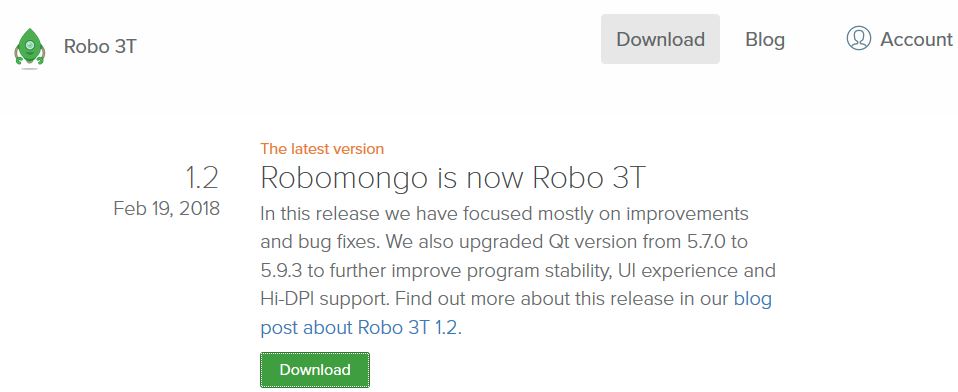

We can click on Download Robo 3T and download the most recent version; it should automatically detect your OS. Download the installer for either Linux or macOS. The one for macOS is really simple. It's one of those installers where you take the icon and drag it into the Applications folder. For Linux, you'll need to extract the archive and run the program in the bin directory. This will start up Robomongo on your Linux distribution.

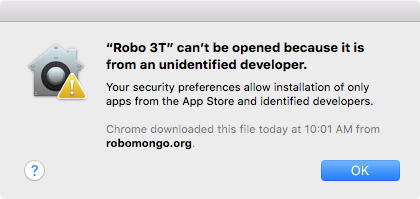

Since I'm using macOS, I'll just quickly drag the icon over to Applications, and then we can play around with the program itself. Next, I'll open it up inside the Finder. When you first open up Robomongo, you might get a warning like the following on macOS, since it's a program that we downloaded and it's not from an identified macOS developer:

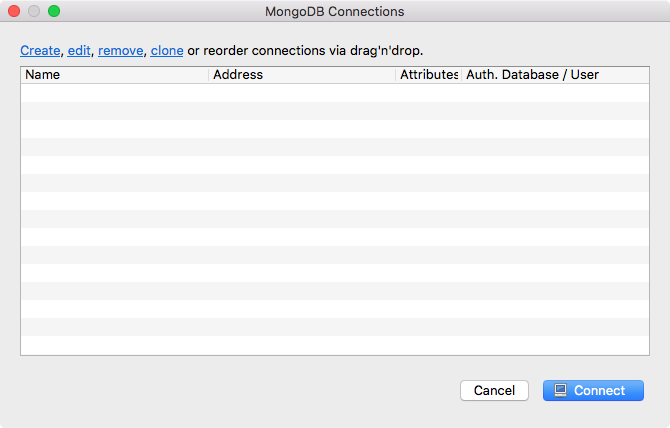

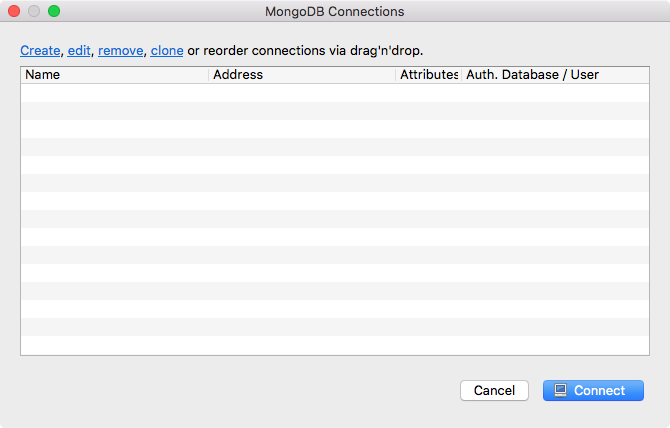

This is fine; most programs you download from the web will not be official since they did not come from the App Store. You can right-click on the downloaded package, select Open, and then click on Open again to run that program. When you first open it, you'll see some screens like the following:

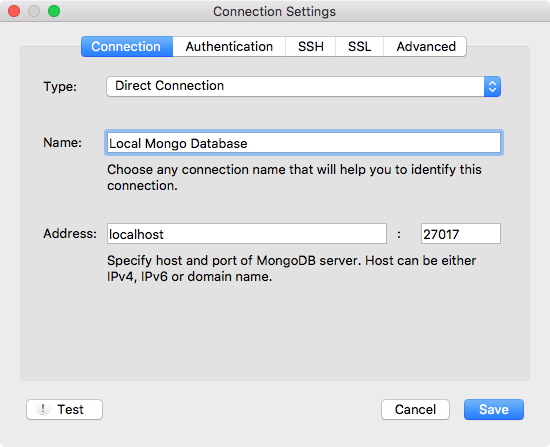

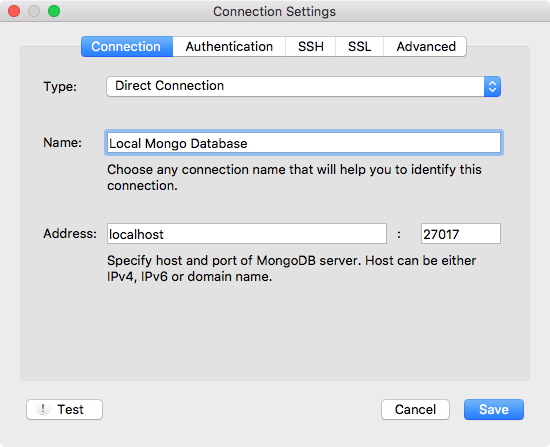

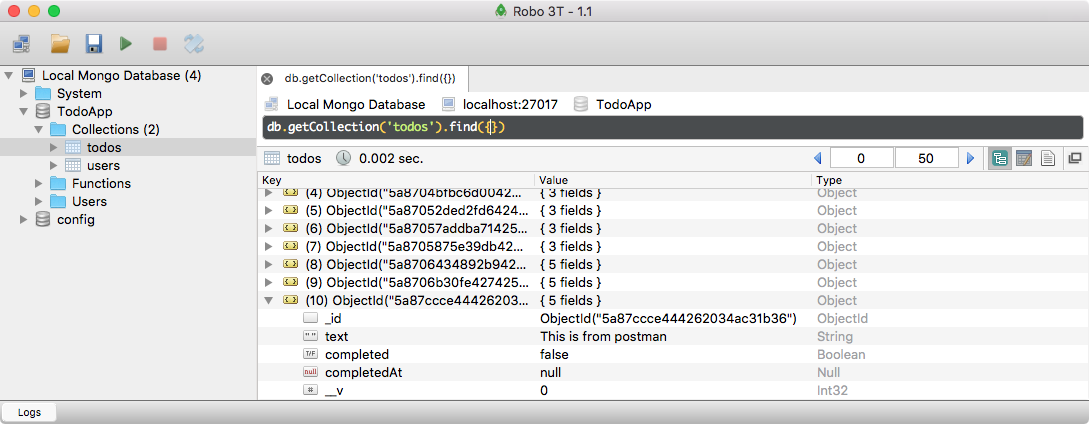

We have a little screen in the background and a list of connections; currently that list is empty. What we need to do is to create a connection for our local MongoDB database so that we can connect to it and manipulate that data. We have Create. I'll click on this, and the only thing we'll need to update is Name. I'll give it a more descriptive name, such as Local Mongo Database. I'll set Address to localhost and the 27017 port is correct; there's no need to change these. So, I'll click on Save:

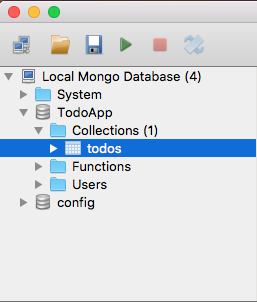

Next, I'll double-click on the database to connect to it. Inside the tiny window, we have our database. We are connected to it; we can do all sorts of things to manage it.

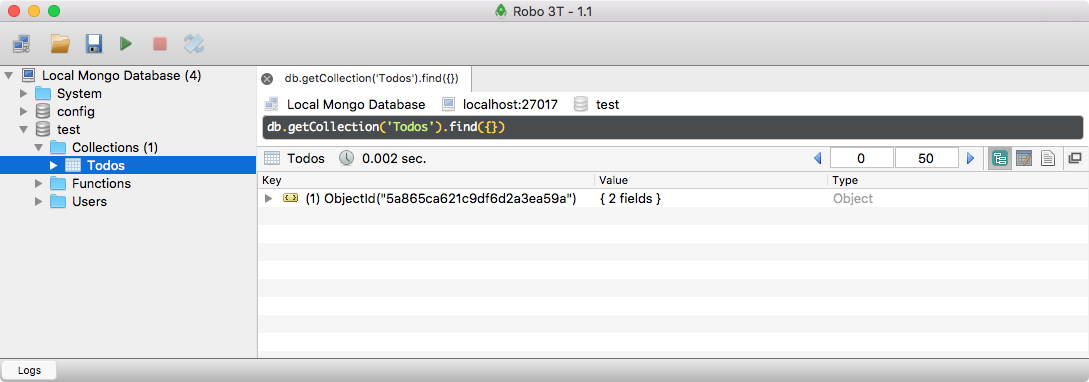

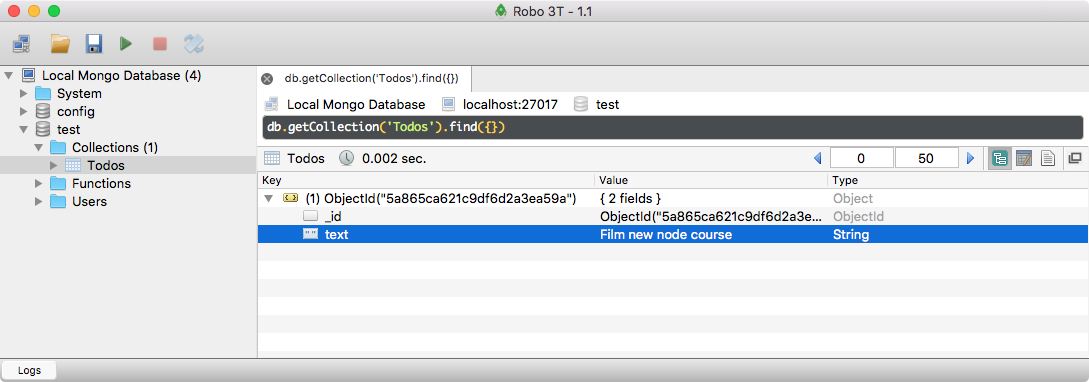

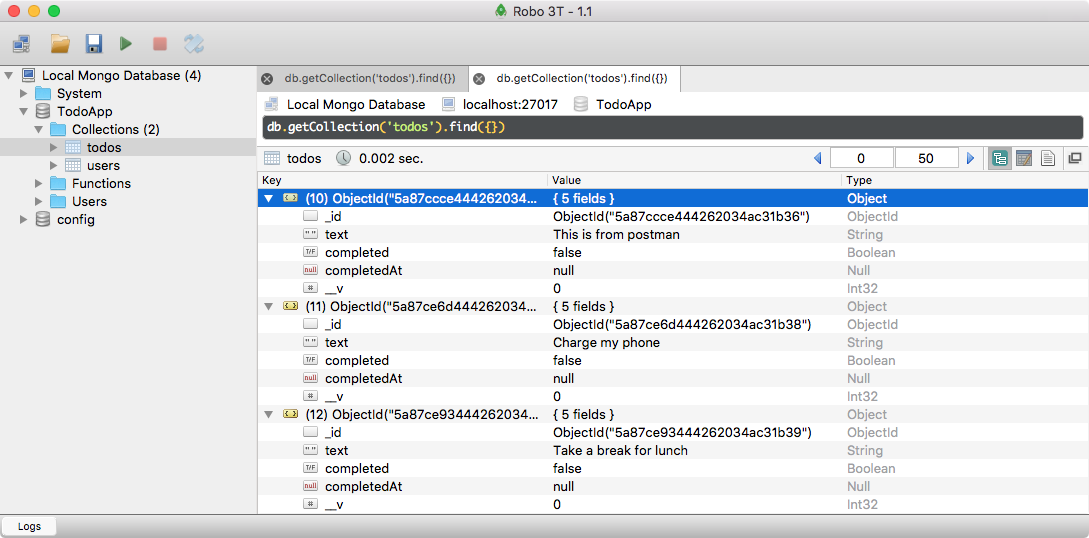

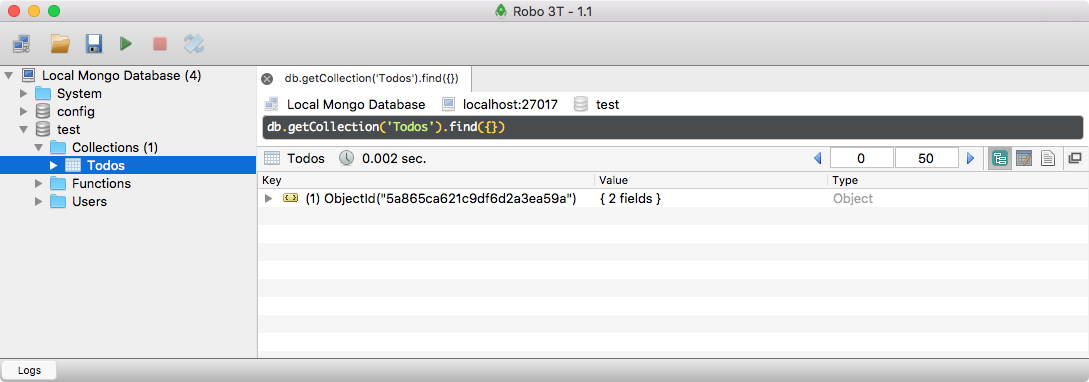

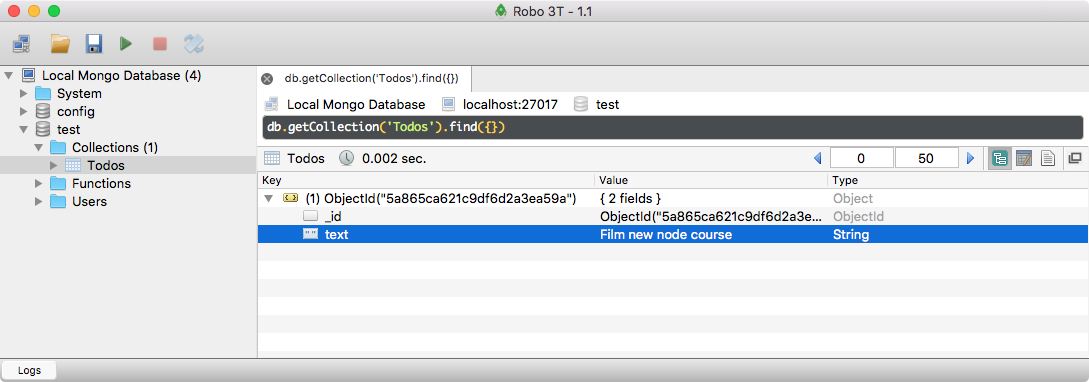

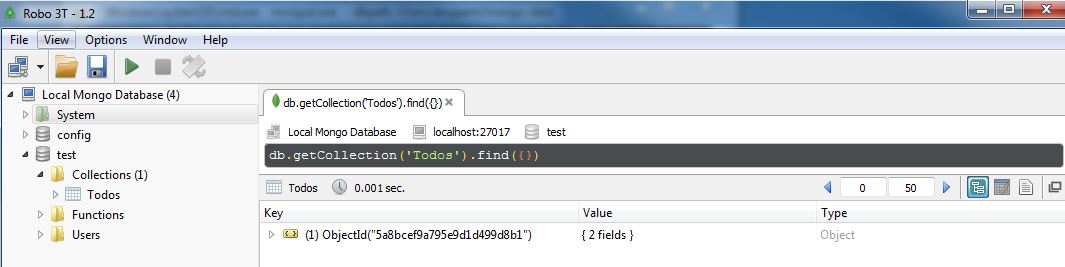

We can open up the test database, and in there, we should see one Collections folder. If we expand this folder, we have our Todos collection, and from there, we can right-click on the collection. Next, click on View Documents, and we should get our one Todo item, the one that we created over inside the Mongo console:

I can expand it to view the text property. Film new node course shows up:

If you're seeing this, then you are done.

The next section is for Windows users.

If you're on Windows, this is the installation section for you. If you're on Linux or macOS, the previous section was for you; you can skip this one. Our goal here is to install MongoDB on our machines, which will let us create a local MongoDB database server. We'll be able to connect to that server with Node.js, and we'll be able to read and write data to the database. This will be fantastic for the Todo API, which will be responsible for reading and writing various Todo-related information.

To get started, we'll grab the MongoDB installer by going over to mongodb.com. Here we can click on the big green Download button; also, we can see several options on this page:

We'll use Community Server and for Windows. If you go to the Version drop down, none of the versions there will look right for you. The top one is what we want: Windows Server 08 R2 64-bit and later with SSL support. Let's start to download this. It is slightly big; just a tad over 100 MB, so it will take a moment for the download to begin.

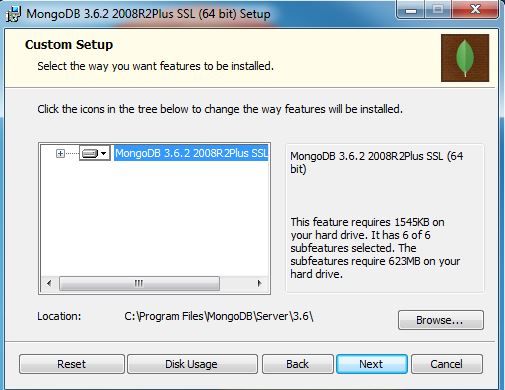

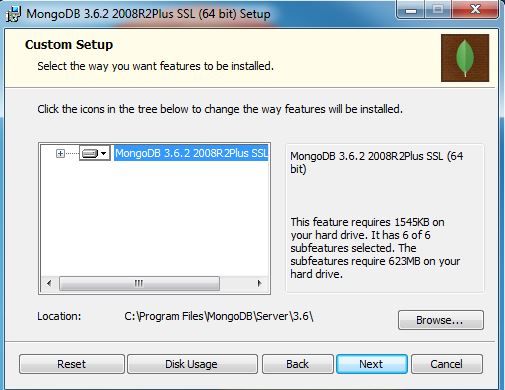

I'll start it up. It's one of those basic installers, where you click on Next a few times and you agree to a license agreement. Click on the Custom option for a second, although we will be following through with the Complete option. When you click on Custom, it will show you where on your machine it's going to be installed, and this is important. Here, you can see that for me it's on C:\Program Files\MongoDB\Server, then in the 3.2 directory:

This is going to be important because we'll need to navigate into this directory in order to start up the MongoDB server. I will go back though, and I will be using the Complete option, which installs everything we need. Now we can actually start the installation process. Usually, you have to click on Yes, verifying that you want to install the software. I'll go ahead and do that, and then we are done.

Now once it's installed, we'll navigate into Command Prompt and boot up a server. The first thing we need to do is to navigate into that Program Files directory. I'm in Command Prompt. I recommend that you use Command Prompt and not Git Bash. Git Bash will not work for starting up the MongoDB server. I'll navigate to the root of my machine using cd/, and then we can start navigating to that path using the following command:

cd Program Files/MongoDB/Server/3.2

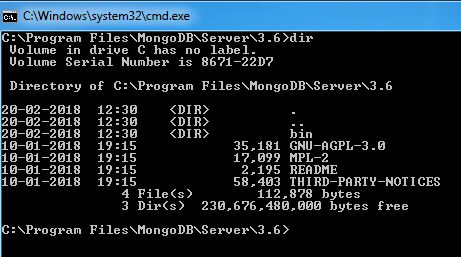

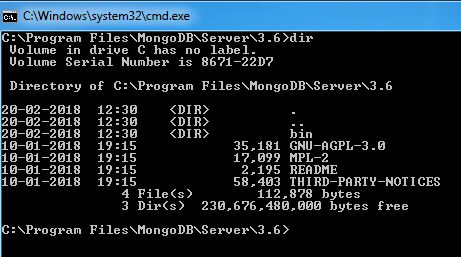

This is the directory where MongoDB was installed. I can use dir to print out the contents of this directory, and what we care about here is the bin directory:

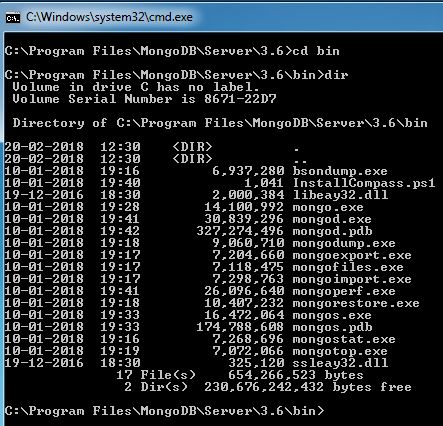

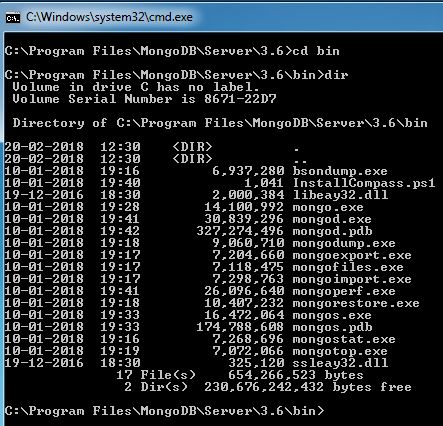

We can navigate into bin using cd bin, and print its contents out using dir. Also, this directory contains a whole bunch of executables that we'll use to do things such as starting up our server and connecting to it:

The first executable we'll run is this mongod.exe file. This will start our local MongoDB database. Before we can go ahead and run this EXE, there is one more thing we need to do. Over in the generic File Explorer, we need to create a directory where all of our data can be stored. To do this, I'll put mine in my user directory by going to the C:/Users/Andrew directory. I'll make a new folder, and I'll call this folder mongo-data. Now, the mongo-data directory is where all of our data will actually be stored. This is the path that we need to specify when we run the mongod.exe command; we need to tell Mongo where to store the data.

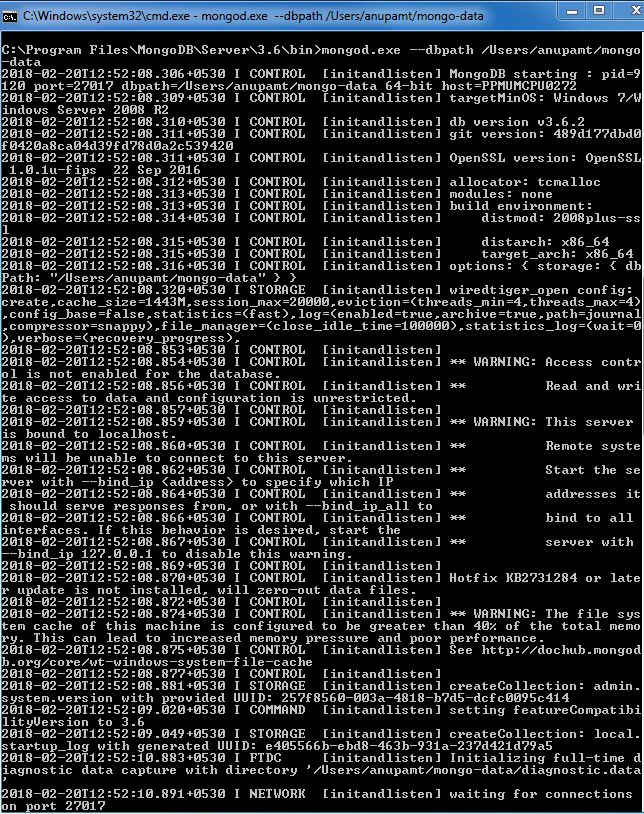

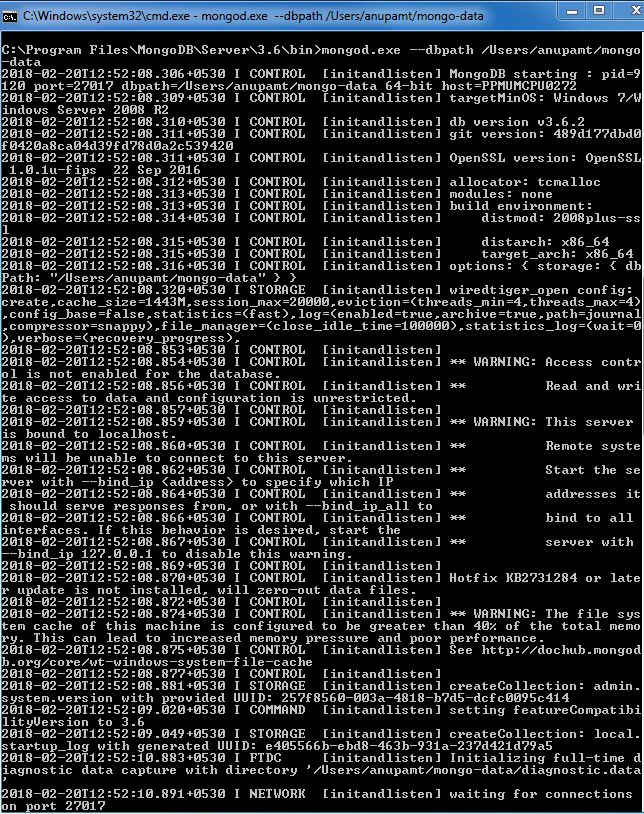

Over in Command Prompt, we can now start this command. I'll run mongod.exe, passing in as the dbpath argument, the path to that folder we just created. In my case, it's /Users/Andrew/mongo-data. Now if your username is different, which it obviously is, or you put the folder in a different directory, you'll need to specify the absolute path to the mongo-data folder. Once you have that though, you can start up the server by running the following command:

mongod.exe --dbpath /Users/Andrew/mongo-data

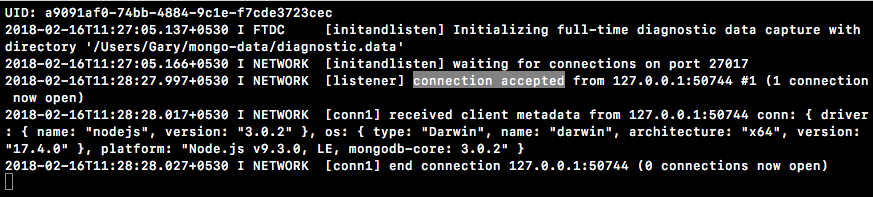

You'll get a long list of output:

The only thing you need to care about is that, at the very bottom, you should see waiting for connections on port 27017. If you see this, then you are good to go. But now that the server is up, let's connect to it and issue some commands to create and read some data.

To do this, we'll open up a second Command Prompt window and navigate into that same bin directory using cd/Program Files/MongoDB/Server/3.2/bin. From here, we'll run mongo.exe. Note that we're not running the mongod command; we're running mongo.exe. This will connect to our local MongoDB database, and it will put us in sort of a Command Prompt view of our database. We'll be able to issue various Mongo commands to manipulate the data, kind of like we can run Node from Command Prompt to run various JavaScript statements right inside the console. When we run this, we're going to connect to the database. Over in the first console window, you can see that connection accepted shows up. We do have a new connection. In the first console window now, we can run some commands to create and read data. Now I don't expect you to take away anything from these commands. We'll not talk about the ins and outs of MongoDB just yet. All I want to do is to make sure that when you run them, it works as expected.

To get started, let's create a new Todo from the console. This can be done via db.Todos, and on this Todos collection, we'll call the .insert method. Also, we'll call insert with one argument, an object; this object can have any properties we want to add to the record. For example, I want to set a text property. This is the thing I actually need to do. Inside quotes, I can put something. I'll go with Create new Node course:

db.Todos.insert({text: 'Create new Node course'})

Now when I run this command, it will actually make the insert into our database and we should get a writeResult object back, with an nInserted property set to 1. This means that one record was inserted.

Now that we have one Todo in our database, we can try to fetch it using db.Todos once again. This time, instead of calling insert to add a record, we'll call find with no arguments provided. This will return every single Todo inside of our database:

db.Todos.find()

When I run this command, We get an object-looking thing where we have a text property set to Create new Node course. We also have an _id property. The _id property is MongoDB's unique identifier, and this is the property that they use to give your document; in this case, a Todo, a unique identifier. We'll be talking more about _id and about all of the commands we just ran, a little later. For now, we can close this using Ctrl + C. We've successfully disconnected from Mongo, and now we can also close the second Command Prompt window.

Before we move on, there is one more thing I want to do. We'll be installing a program called Robomongo—a GUI for MongoDB. It will let you connect to your local database as well as real databases, which we'll be talking about later. Also, it'll let you view all the data, manipulate it and do anything you could do inside a database GUI. It's really useful; sometimes you just need to dive into a database to see exactly what the data looks like.

In order to get this started, we'll head over to a new tab and go to robomongo.org:

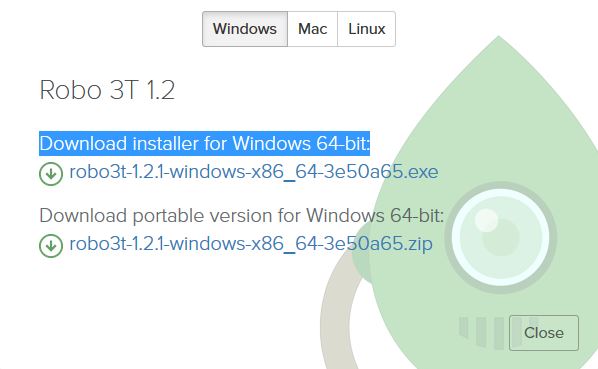

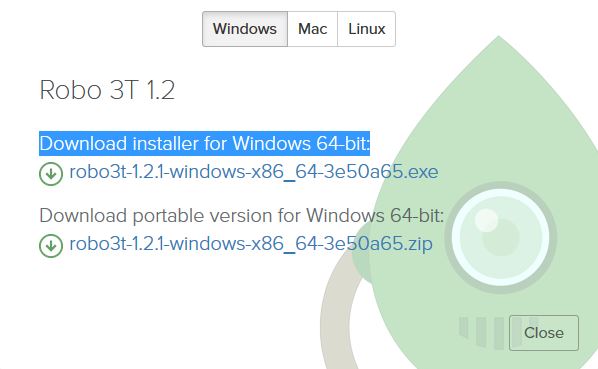

Here we can grab the installer by going to Download. We'll download the latest version, and I'm on Windows. I want the installer, not the portable version, so I'll click on the first link here:

This is going to start a really small download, just 17 MB, and we can click on Next a few times through this one to get Robomongo installed on our machines.

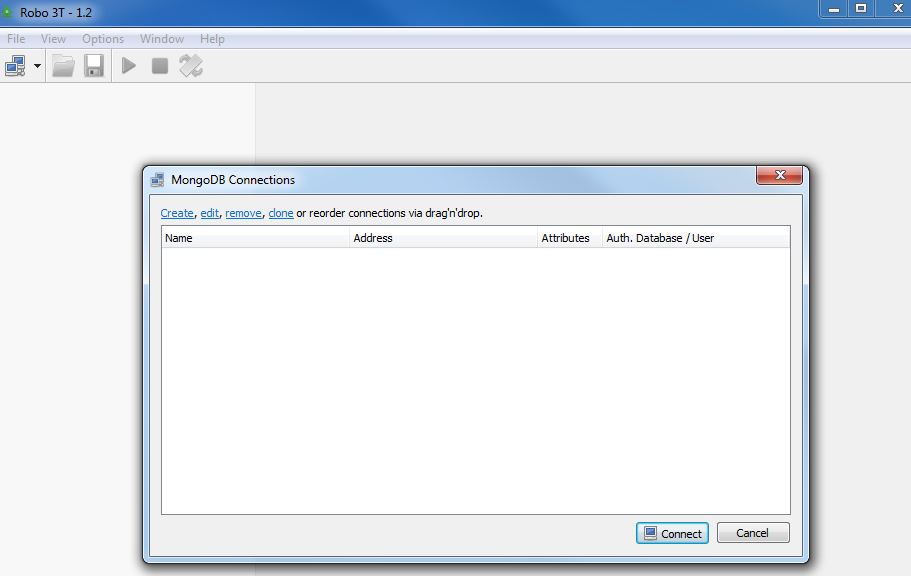

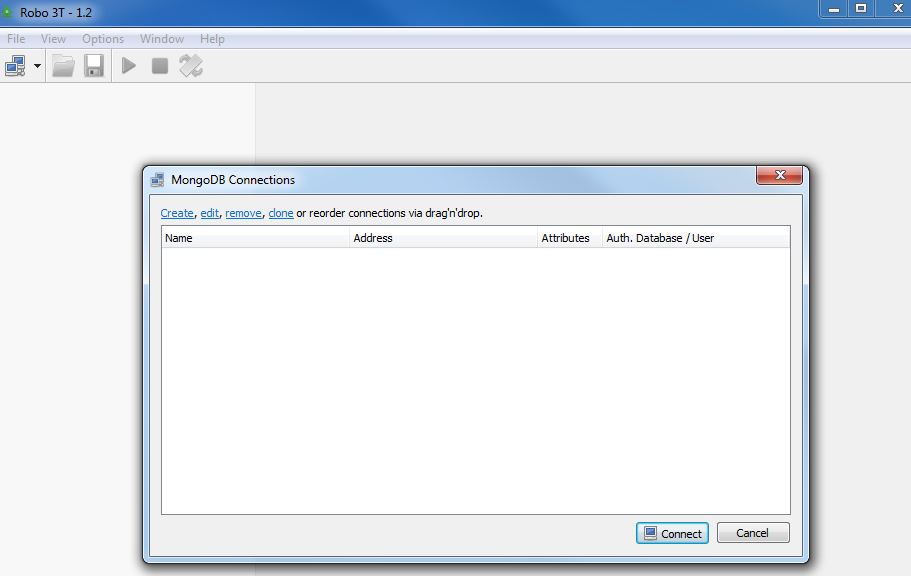

I'll start the process, confirming installation and clicking on Next just a couple of times. There's no need to do anything custom inside the settings. We'll run the installer with all of the default settings applied. Now we can actually run the program by finishing all the steps in the installer. When you run Robomongo, you'll be greeted with a MongoDB Connections screen:

This screen lets you configure all of the connections for Robomongo. You might have a local connection for your local database, and you might have a connection to a real URL where your actual production data is stored. We'll get into all that later.

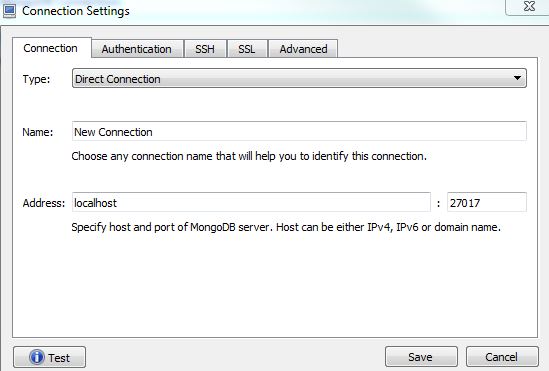

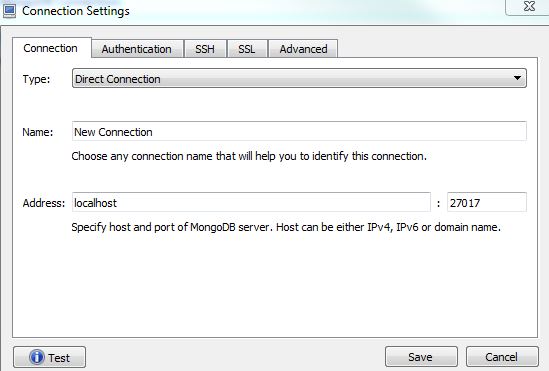

For now, we'll click on Create. By default, your localhost address and your 27017 port do not need to be changed:

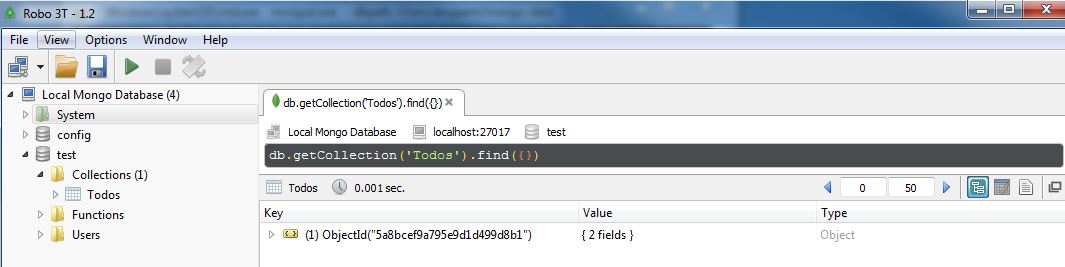

All I'm going to do is to change the name so that it's a little easier to identify. I'll go with Local Mongo Database. Now, we can save our new connection and actually connect to the database by simply double-clicking on it. When we do that, we get a little tree view of our database. We have this test database; this is the one that's created by default, which we can expand. Then we can expand our Collections folder and see the Todos collection. This is the collection we created inside the console. I'll right-click on this and go to View Documents. When I view the documents, I actually get to view the individual records:

Here, I see my _id and text properties that have Create new Node course sitting in the above image.

If you are seeing this, then this means that you have a local Mongo server running, and it also means that you've successfully inserted data into it.

In this chapter, you downloaded and ran the MongoDB database server. This means that we have a local database server we can connect to from our Node application. We also installed Robomongo, which lets us connect to our local database so that we can view and manipulate data. This comes in handy when you're debugging or managing data, or doing anything else with your Mongo database. We'll be using it throughout the book, and you'll begin to see why it's valuable in the later chapters. For now though, you are all set up. You are ready to continue on and start building the Todo API.

In this chapter, you're going to learn how to connect your Node applications to the MongoDB database you've been running on your local machine. This means that we'll be able to issue database commands right inside of our Node apps to do stuff like insert, update, delete, or read data. This is going to be critical if we're ever going to make that Todo REST API. When someone hits one of our API endpoints, we want to manipulate the database, whether it's reading all of the Todos or adding a new one. Before we can do any of that though, we have to learn the basics.

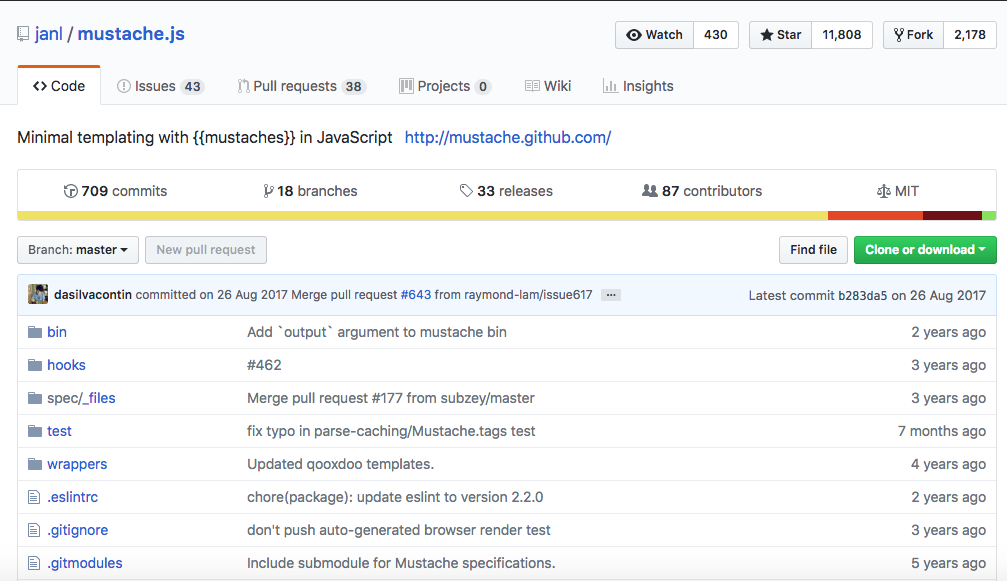

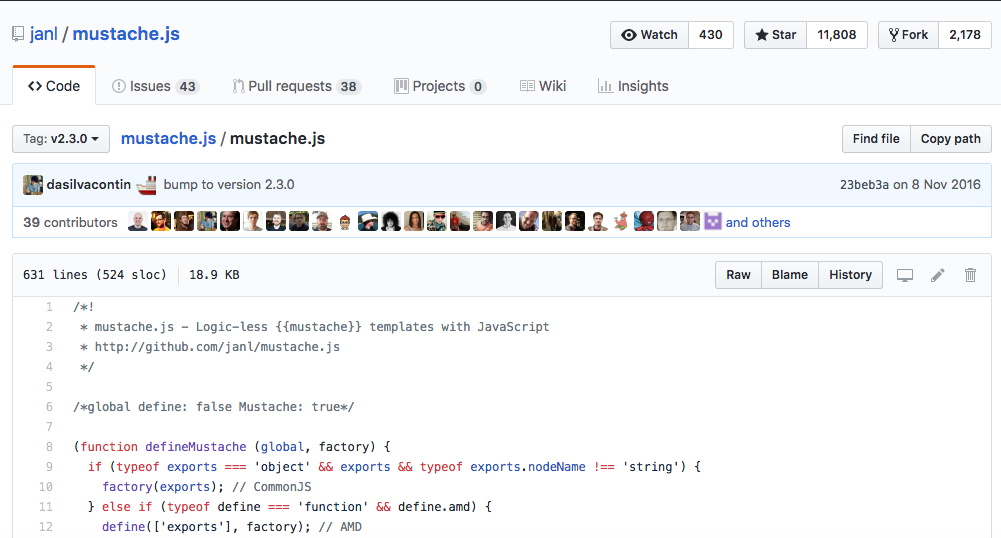

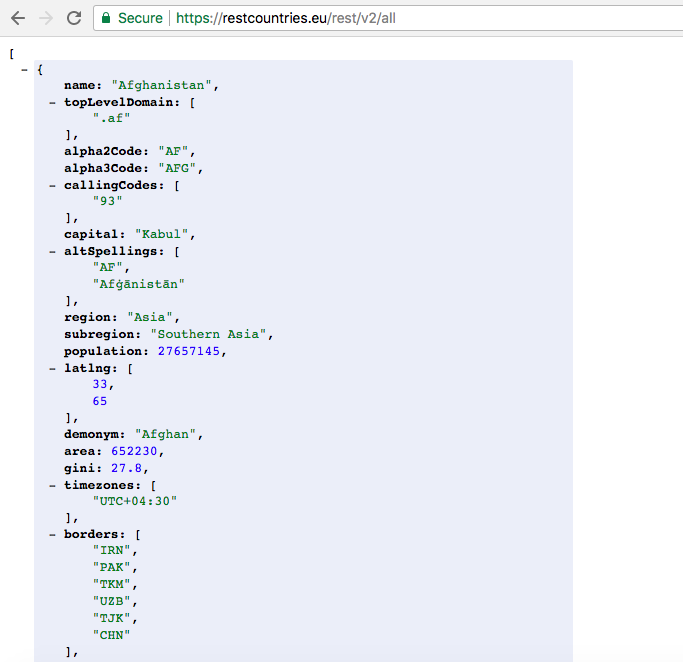

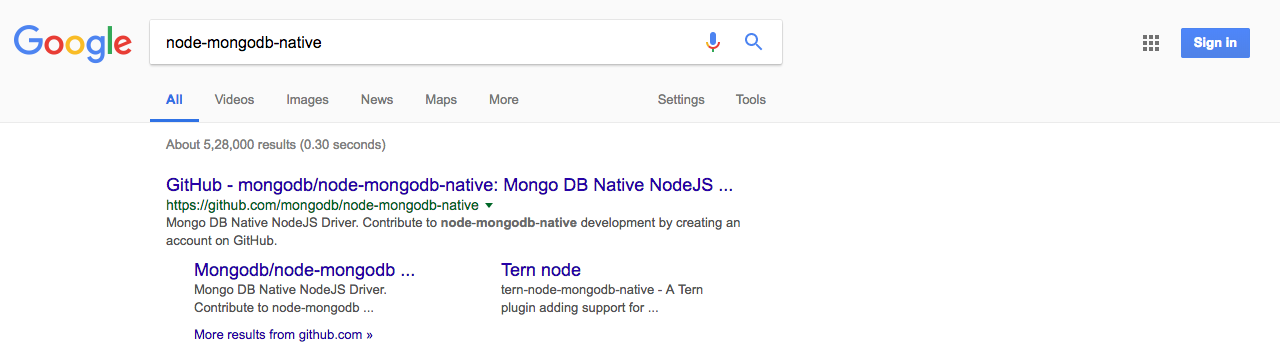

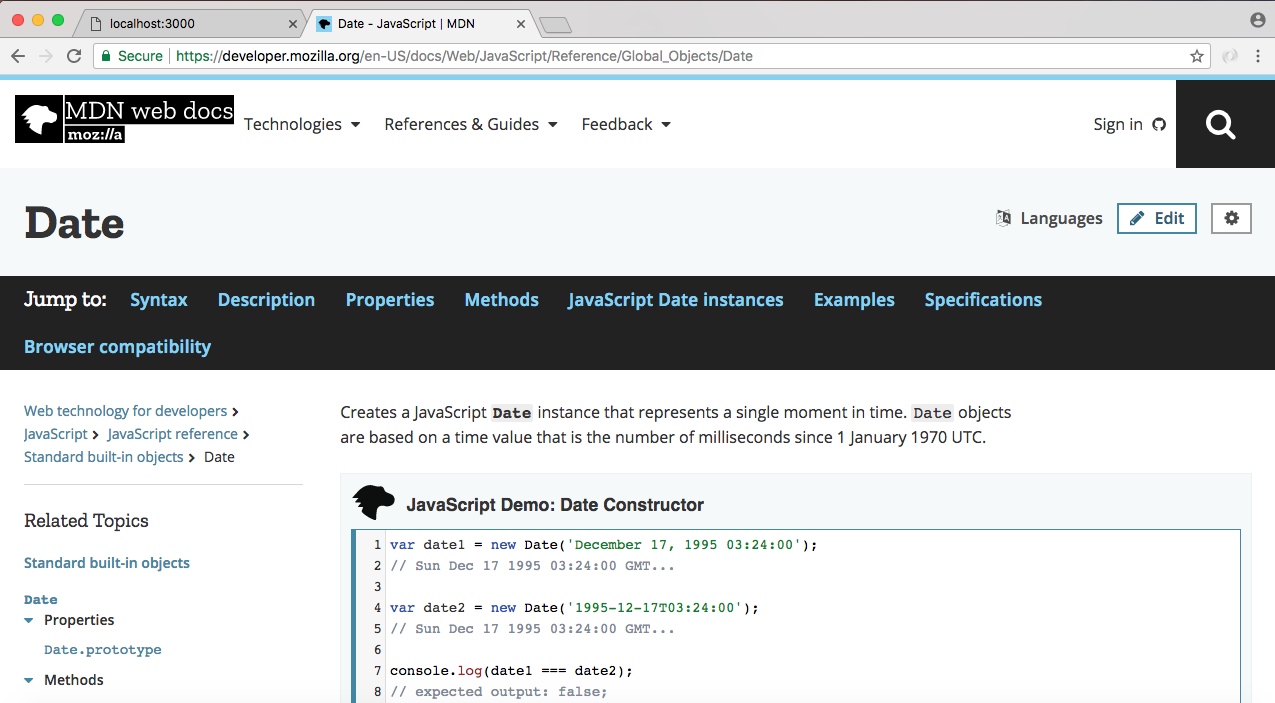

To connect to our MongoDB database from inside of Node.js, we're going to be using an npm module created by the MongoDB team. It's called node-mongodb-native, but it includes all of the features you'll need to connect to and interact with your database. To get to it, we're going to Google node-mongodb-native:

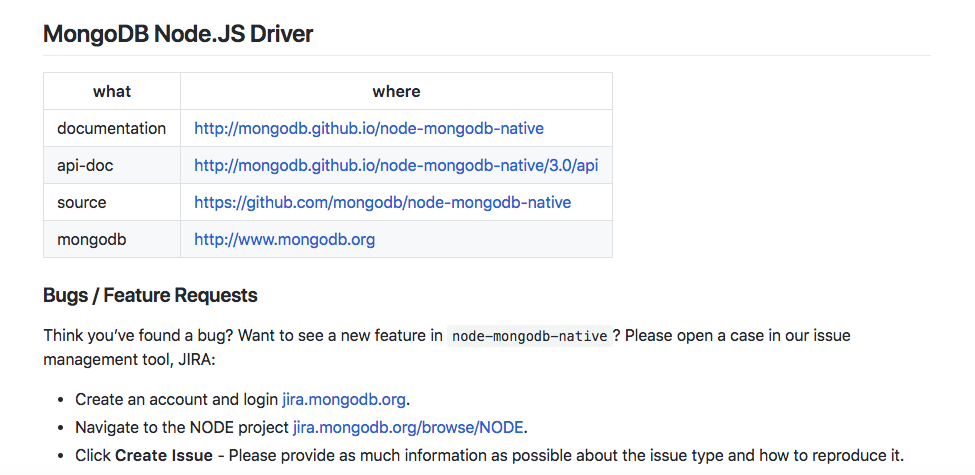

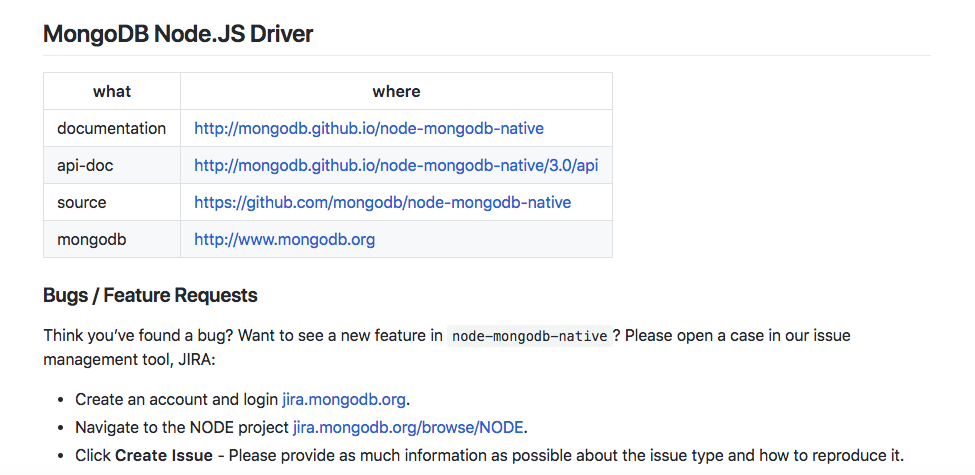

The GitHub repo, which should be the first link, is the one we want—the node-mongodb-native repository—and if we scroll down, we can take a look at a few important links:

First up we have documentation, and we also have our api-docs; these are going to be critical as we start exploring the features that we have inside of this library. If we scroll down further on this page, we'll find a ton of examples on how to get started. We'll be going through a lot of this stuff in this chapter, but I do want to make you aware of where you can find other resources because the mongodb-native library has a ton of features. There are entire courses dedicated to MongoDB, and they don't even begin to cover everything that's built-in to this library.

We're going to be focusing on the important and common subset of MongoDB that we need for Node.js apps. To get started, let's go ahead and open up the documentations, which are shown in the preceding image. When you go to the docs page, you have to pick your version. We'll be using version 3.0 of the driver, and there's two important links:

For now though, we can get started by creating a new directory for this project, and then we're going to go ahead and install the MongoDB library and connect to the database we have running. I am going to assume that you have your database running for all the sections in this chapter. I have it running in a separate tab in my Terminal.

If you're on Windows, refer to the instructions in the Windows installation section to start your database if you forget. If you're on a Linux or macOS operating system, use the instructions I have already mentioned, and don't forget to also include that dbpath argument, which is essential for booting up your MongoDB server.

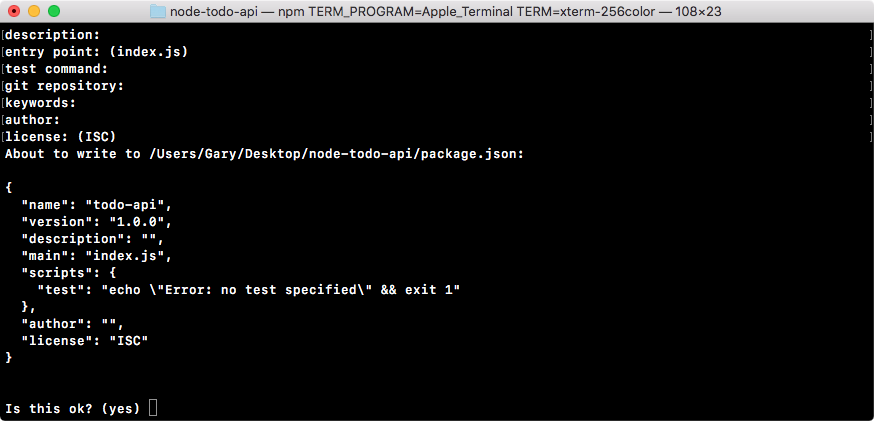

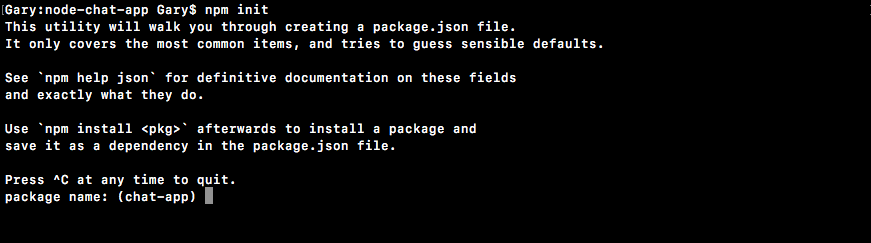

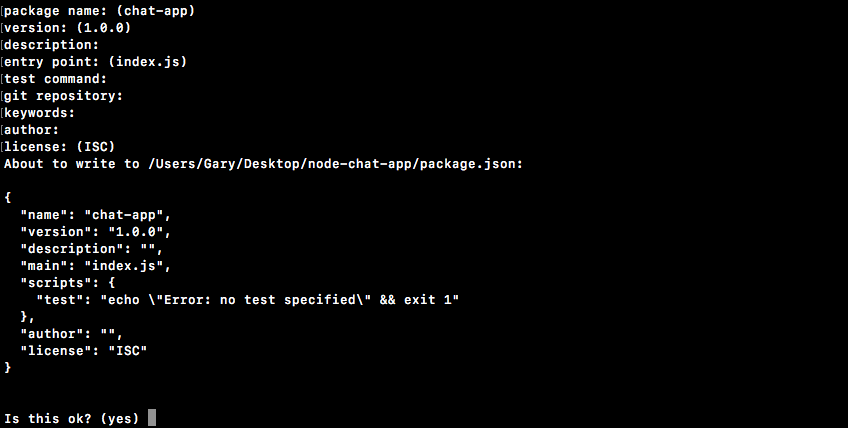

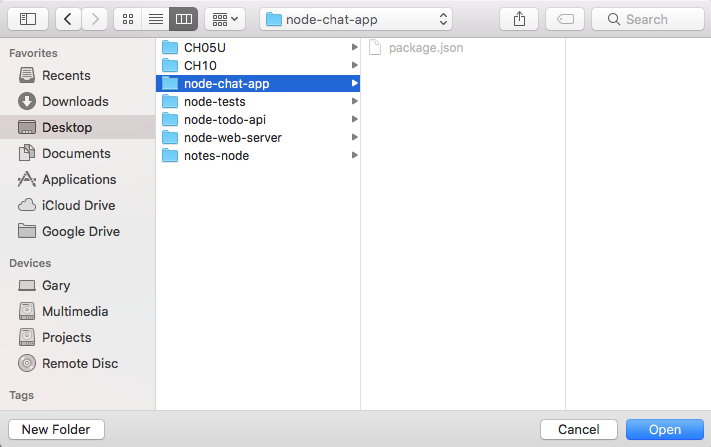

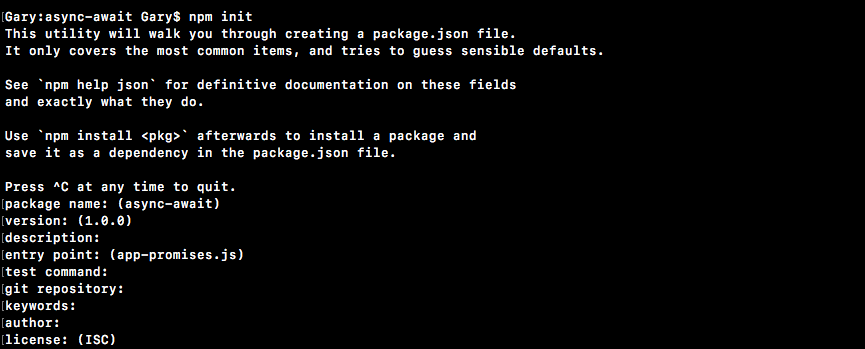

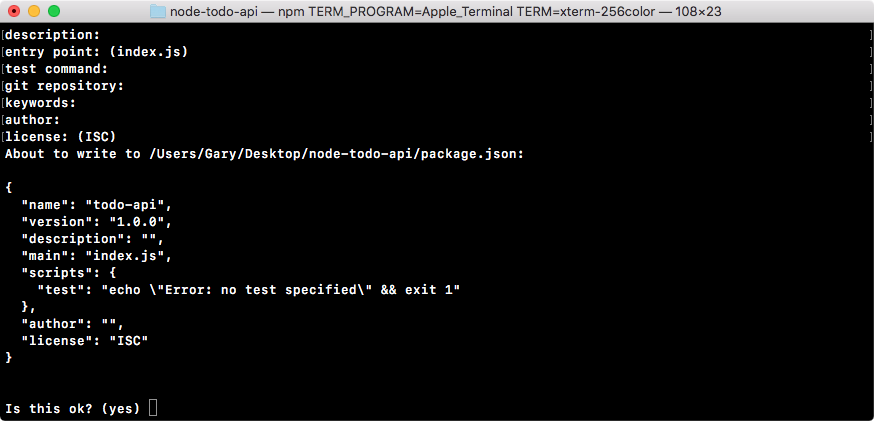

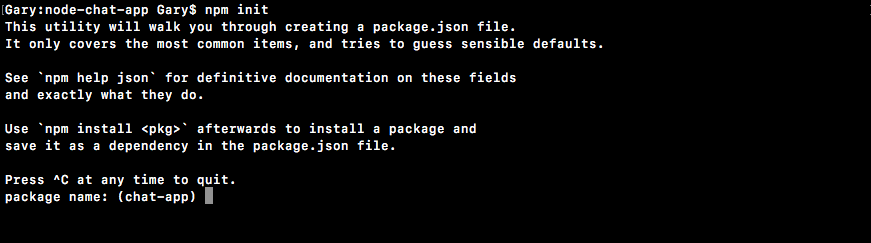

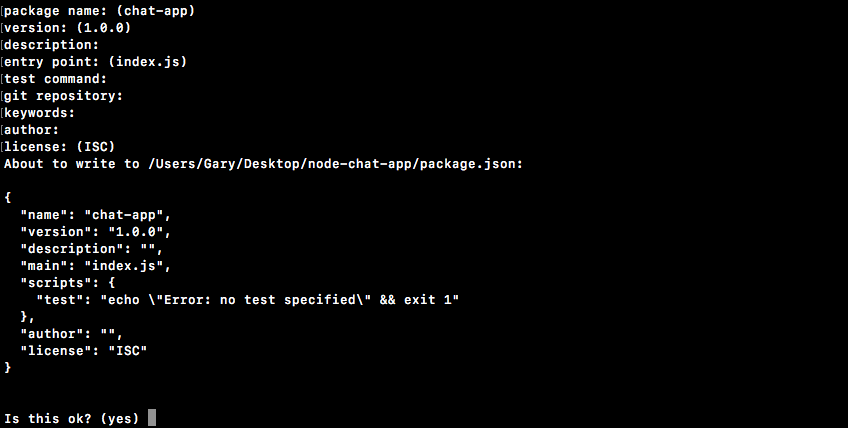

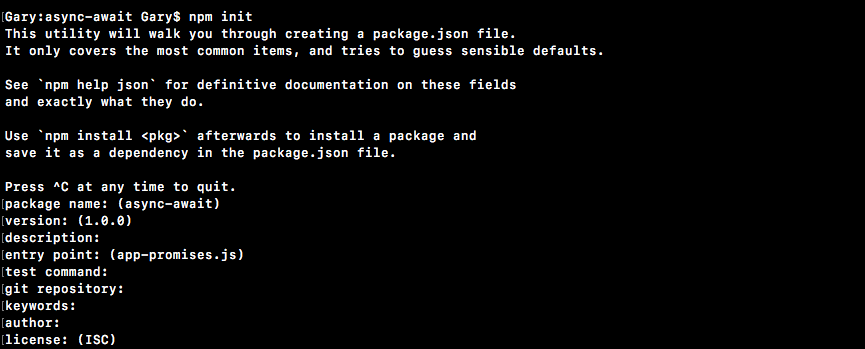

To kick things off, I'm going to make a new folder on the Desktop for the Node API. I'll use mkdir to create a new folder called node-todo-api. Then, I can go ahead and use cd to go into that directory, cd node-todo-api. And from here, we're going to run npm init, which creates our package.json file and lets us install our MongoDB library. Once again, we're going to be using enter to skip through all of the options, using the defaults for each:

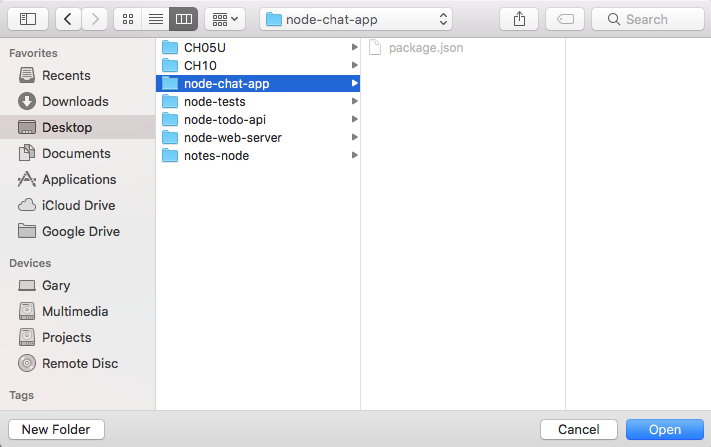

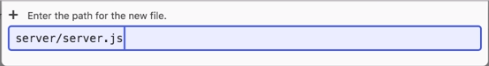

Once we get to the end we can confirm our selections, and now our package.json file is created. The next thing we're going to do is open up this directory inside of Atom. It's on the Desktop, node-todo-api. Next up, inside of the root of the project we're going to create a new folder, and I'm going to call this folder playground. Inside of this folder, we'll store various scripts. They're not going to be scripts related to the Todo API; they'll be scripts related to MongoDB, so I do want to keep them in the folder, but I don't necessarily want them to be part of the app. We'll use the playground folder for that, like we have in the past.

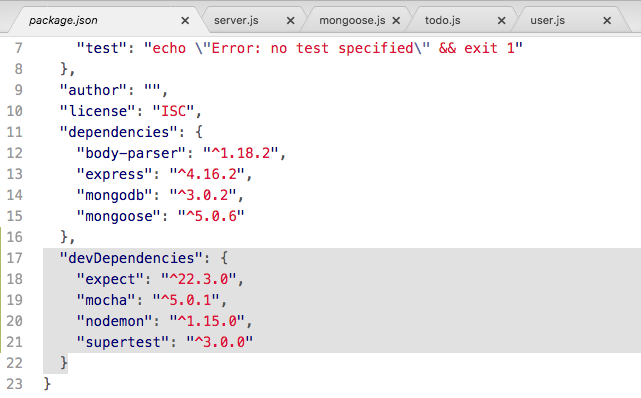

In the playground folder, let's go ahead and make a new file, and we'll call this file mongodb-connect.js. Inside of this file, we're going to get started by loading in the library and connecting to the database. Now in order to do that, we have to install the library. From the Terminal, we can run npm install to get that done. The new library name is mongodb; all lowercase, no hyphens. Then, we're going to go ahead and specify the version to make sure we're all using the same functionality, @3.0.2. This is the most recent version at the time of writing. After the version number, I am going to use the --save flag. This is going to save it as a regular dependency, which it already is:

npm install mongodb@3.0.2 --save

We're going to need this to run the Todo API application.

With MongoDB now installed, we can move it to our mongodb-connect file and start connecting to the database. The first thing we need to do is pull something out of the library that we just installed, which is the mongodb library. What we're looking for is something called the MongoClient constructor. The MongoClient constructor lets you connect to a Mongo server and issue commands to manipulate the database. Let's go ahead and kick things off by creating a constant called MongoClient. We're going to set that equal to require, and we're going to require the library we just installed, mongodb. From that library, we're going to pull off MongoClient:

const MongoClient = require('mongodb').MongoClient;

With the MongoClient now in place, we can call MongoClient.connect to connect to the database. This is a method, and it takes two arguments:

For the first argument in our case, we're going to start off with mongodb://. When we connect to a MongoDB database, we want to use the mongodb protocol like this:

MongoClient.connect('mongodb://')

Next up, it's going to be at localhost since we're running it on our local machine, and we have the port, which we have already explored: 27017. After the port, we need to use / to specify which database we want to connect to. Now, in the previous chapter, we used that test database. This is the default database that MongoDB gives you, but we could go ahead and create a new one. After the /, I'm going to call the database TodoApp, just like this:

MongoClient.connect('mongodb://localhost:27017/TodoApp');

Next up, we can go ahead and provide the callback function. I'm going to use an ES6 arrow (=>) function, and we're going to get past two arguments. The first one is going to be an error argument. This may or may not exist; just like we've seen in the past, it'll exist if an error actually happened; otherwise it won't. The second argument is going to be the client object. This is what we can use to issue commands to read and write data:

MongoClient.connect('mongodb://localhost:27017/TodoApp', (err, client) => {

});

Now, before we write any data, I'm going to go ahead and handle any potential errors that come about. I'll do that using an if statement. If there is an error, we're going to print a message to the console, letting whoever is looking at the logs know that we were unable to connect to the database server, console.log, then inside of quotes put something like Unable to connect to MongoDB server. After the if statement, we can go ahead and log out a success message, which will be something like console.log. Then, inside of quotes, we'll use Connected to MongoDB server:

MongoClient.connect('mongodb://localhost:27017/TodoApp', (err, client) => {

if(err){

console.log('Unable to connect to MongoDB server');

}

console.log('Connected to MongoDB server');

});

Now, when you're handling errors like this, the success code is going to run even if the error block runs. What we want to do instead is add a return statement right before the console.log('Unable to connect to MongoDB server'); line.

This return statement isn't doing anything fancy. All we're doing is using it to prevent the rest of the function from executing. As soon as you return from a function, the program stops, which means if an error does occur, the message will get logged, the function will stop, and we'll never see this Connected to MongoDB server message:

if(err) {

return console.log('Unable to connect to MongoDB server');

}

An alternative to using the return keyword would be to add an else clause and put our success code in an else clause, but it's unnecessary. We can just use the return syntax, which I prefer.

Now, before we run this file, there is one more thing I want to do. At the very bottom of our callback function, we're going to call a method on db. It's called client.close:

MongoClient.connect('mongodb://localhost:27017/TodoApp', (err, client) => {

if(err) {

return console.log('Unable to connect to MongoDB server');

}

console.log('Connected to MongoDB server');

const db = client.db('TodoApp');

client.close(); });

This closes the connection with the MongoDB server. Now that we have this in place, we can actually save the mongodb-connect file and run it inside of the Terminal. It doesn't do much yet, but it is indeed going to work.

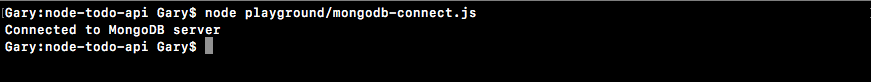

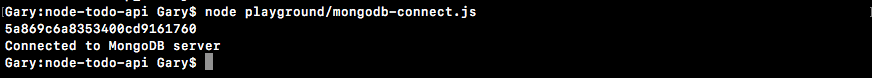

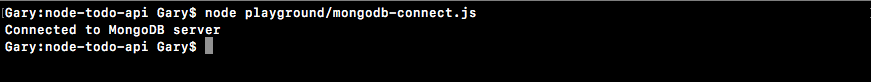

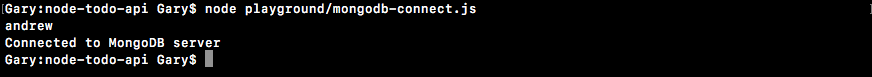

Inside the Terminal, we can run the file using node playground as the directory, with the file itself being mongodb-connect.js:

node playground/mongodb-connect.js

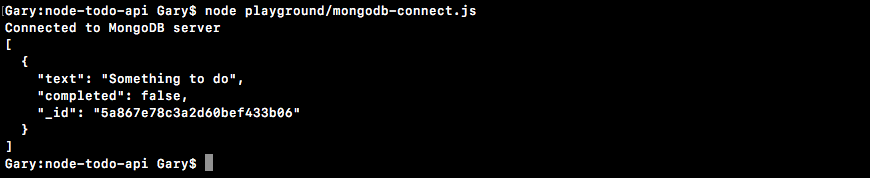

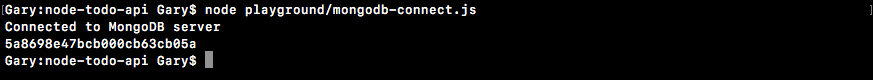

When we run this file, we get Connected to MongoDB server printing to the screen:

If we head over into the tab where we have the MongoDB server, we can see we got a new connection: connection accepted. As you can see in the following screenshot, that connection was closed down, which is fantastic:

Using the Mongo library we were able to connect, print a message, and disconnect from the server.

Now, you might have noticed that we changed the database name in the MongoClient.connect line in Atom, and we never actually did anything to create it. In MongoDB, unlike other database programs, you don't need to create a database before you start using it. If I want to kick up a new database I simply give it a name, something like Users.

Now that I have a Users database, I can connect to it and I can manipulate it. There is no need to create that database first. I'm going to go ahead and change the database name back to TodoApp. If we head into the Robomongo program and connect to our local database, you'll also see that the only database we have is test. The TodoApp database was never even created, even though we connected to it. Mongo is not going to create the database until we start adding data into it. We can go ahead and do that right now.

Inside of Atom, before our call to db.close, we're going to insert a new record into a collection. This is going to be the Todo application. We're going to have two collections in this app:

We can go ahead and start adding some data to the Todos collection by calling db.collection. The db.collection method takes the string name for the collection you want to insert into as its only argument. Now, like the actual database itself, you don't need to create this collection first. You can simply give it a name, like Todos, and you can start inserting into it. There is no need to run any command to create it:

db.collection('Todos')

Next, we're going to use a method available in our collection called insertOne. The insertOne method lets you insert a new document into your collection. It takes two arguments:

You're going to get an error argument, which may or may not exist, and you'll also get the result argument, which is going to be provided if things went well:

const MongoClient = require('mongodb').MongoClient;

MongoClient.connect('mongodb://localhost:27017/TodoApp', (err, client) => {

if(err){

console.log('Unable to connect to MongoDB server');

}

console.log('Connected to MongoDB server');

const db = client.db('TodoApp');

db.collection('Todos').insertOne({

text: 'Something to do',

completed: false

}, (err, result) => {

});

client.close();

});

Inside of the error callback function itself, we can add some code to handle the error, and then we'll add some code to print the object to the screen if it was added successfully. First up, let's add an error handler. Much like we have done previously, we're going to check if the error argument exists. If it does, then we'll simply print a message using the return keyword to stop the function from executing. Next, we can use console.log to print Unable to insert todo. The second argument I'm going to pass to the console.log is going to be the actual err object itself, so if someone's looking at the logs, they can see exactly what went wrong:

db.collection('Todos').insertOne({

text: 'Something to do',

completed: false

}, (err, result) => {

if(err){

return console.log('Unable to insert todo', err);

}

Next to our if statement, we can add our success code. In this case, all we're going to do is pretty-print something to the console.log screen, and then I'm going to call JSON.stringify, where we're going to go ahead and pass in result.ops. The ops attribute is going to store all of the docs that were inserted. In this case, we used insertOne, so it's just going to be our one document. Then, I can add my other two arguments, which are undefined for the filter function, and 2 for the indentation:

db.collection('Todos').insertOne({

text: 'Something to do',

completed: false

}, (err, result) => {

if(err){

return console.log('Unable to insert todo', err);

}

console.log(JSON.stringify(result.ops, undefined, 2));

});

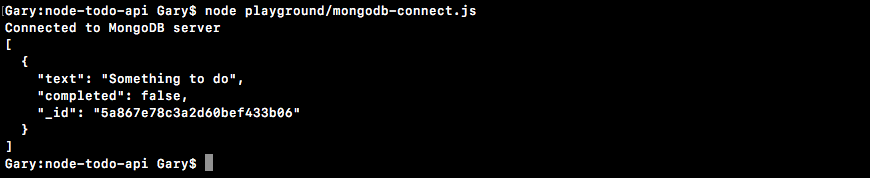

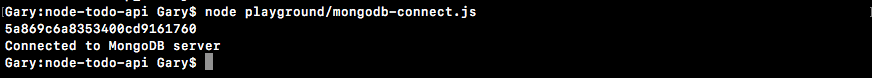

With this in place, we can now go ahead and execute our file and see what happens. Inside of the Terminal, I'm going to run the following command:

node playground/ mongodb-connect.js

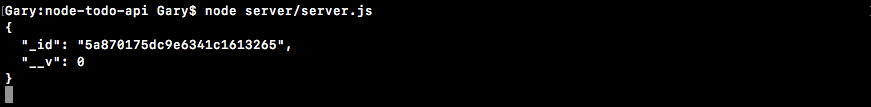

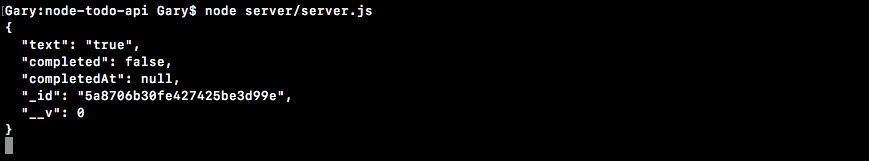

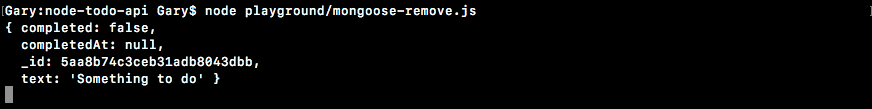

When I execute the command, we get our success message: Connected to MongoDB server. Then, we get an array of documents that were inserted:

Now as I mentioned, in this case we just inserted one document, and that shows up as shown in the preceding screenshot. We have the text property, which gets created by us; we have the completed property, which gets created by us; and we have the _id property, which gets automatically added by Mongo. The _id property is going to be the topic of the following section. We're going to talk in depth about what it is, why it exists and why it's awesome.

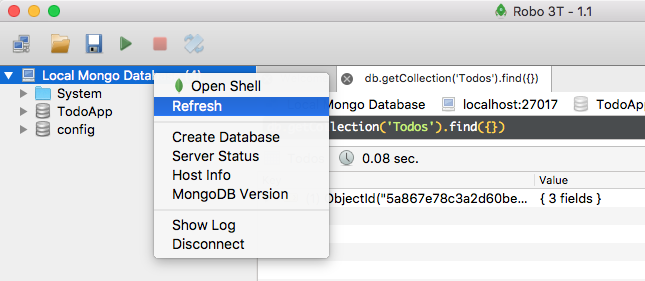

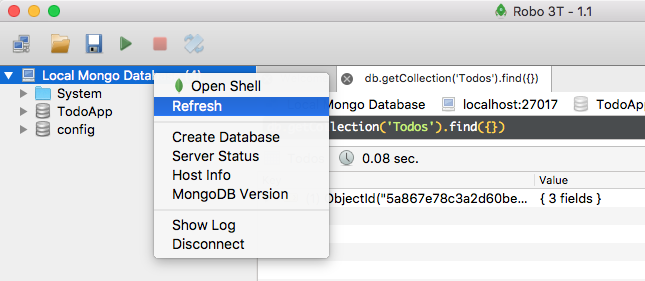

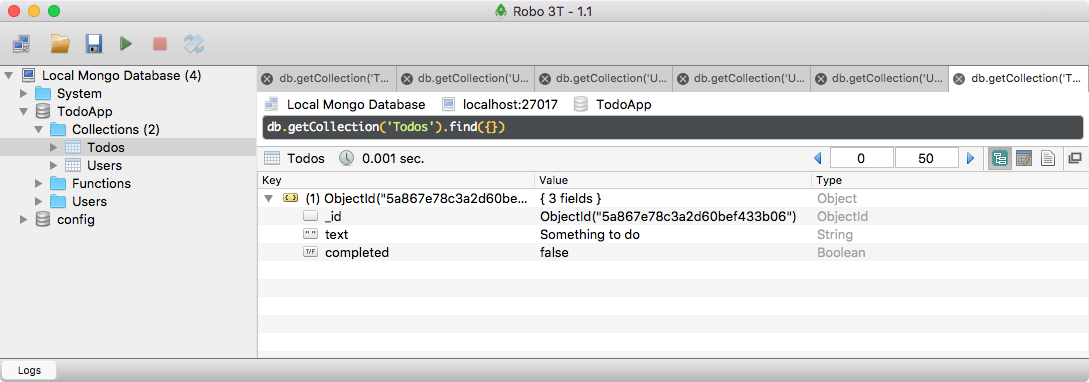

For now, we're going to go ahead and just note that it's a unique identifier. It's an ID given to just this document. That is all it takes to insert a document into your MongoDB database using Node.js. We can view this document inside of Robomongo. I'm going to right-click the connection, and click Refresh:

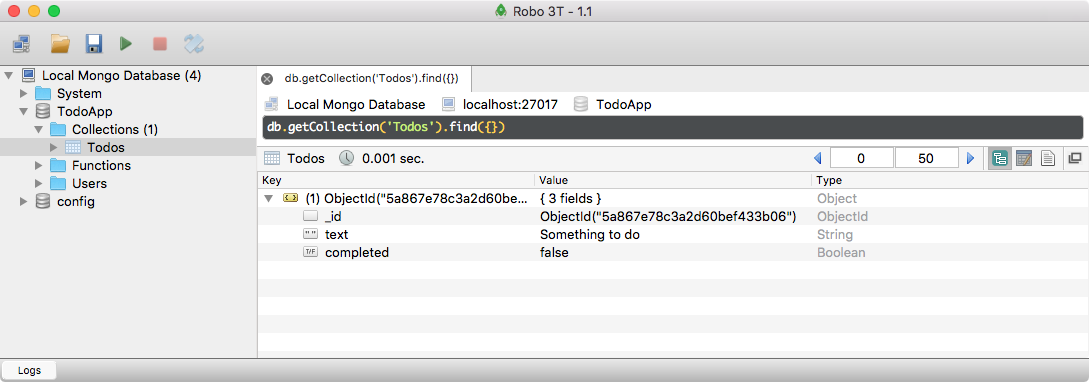

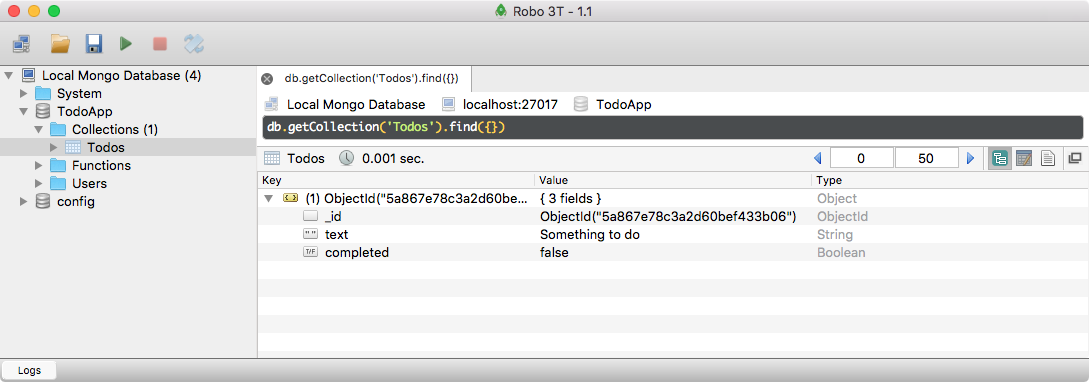

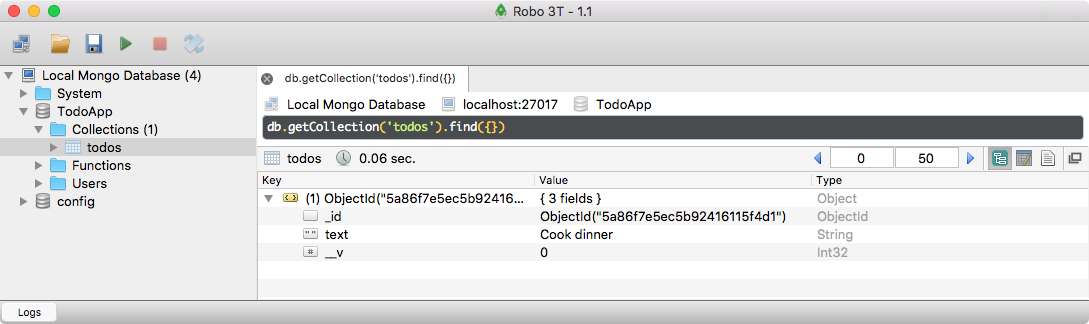

This reveals our brand new TodoApp database. If we open that up, we get our Collections list. We can then go into the Collections, view the documents, and what do we get? We get our one Todo item. If we expand it, we can see we have our _id, we have our text property, and we have our completed Boolean:

In this case, the Todo is not completed, so the completed value is false. Now, what I want you to do is add a new record into a collection. This is going to be your challenge for the section.

Inside of Atom, what I'd like you to do is take the code all the way from db.collection down to the bottom of our callback, and comment it out. Then, we're going to go ahead and add something following it. Right previous db.close(), you're going to type Insert new doc into the Users collection. This doc is going to have a few properties. I want you to give it a name property; set that equal to your name. Then, we're going to give it an age property, and last but not least we can give it a location string. I want you to insert that doc using insertOne. You're going to need to pass in the new collection name into the collection method. Then, further down, you're going to add some error-handling code, and you're going to print the ops to the screen. Once you rerun the file, you should be able to view your record in the Terminal and you should be able to refresh things. Over in Robomongo, you should see the new Users collection, and you should see your user with the name, age, and location you specified.

Hopefully, you were able to insert a new document into the Users collection. What you needed to do in order to get this done is call db.collection so we can access the collection we want to insert into, which in this case is Users:

//Insert new doc into Users(name, age, location)

db.collection('Users')

Next up, we have to call a method to manipulate the Users collection. We want to insert a new document, so we're going to use insertOne, just like we did in the previous sub-section. We're going to pass our two arguments into insertOne. The first one is the document to insert. We're going to give it a name property; I'll set that equal to Andrew. Then, we can go ahead and set the age equal to something like 25. Lastly, we'll set the location equal to my current location, Philadelphia:

//Insert new doc into Users(name, age, location)

db.collection('Users').insertOne({

name: 'Andrew',

age: 25,

location: 'Philadelphia'

}

The next argument we want it to pass in is our callback function, which is going to get called with the error object as well as the results. Inside of the callback function itself, we're going to first handle the error. If there was an error, we're going to go ahead and log it to the screen. I'm going to return console.log, and then we can put the message: Unable to insert user. Then, I'll add the error argument as the second argument for console.log. Next up, we can add our success case code. If things go well, all I'm going to do is use console.log to print result.ops to the screen. This is going to show us all of the records that were inserted:

//Insert new doc into Users(name, age, location)

db.collection('Users').insertOne({

name: 'Andrew',

age: 25,

location: 'Philadelphia'

}, (err, result) => {

if(err) {

return console.log('Unable to insert user', err);

}

console.log(result.ops);

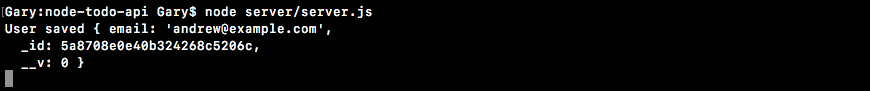

});

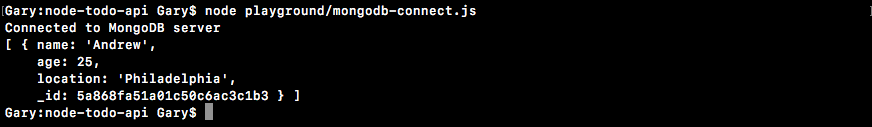

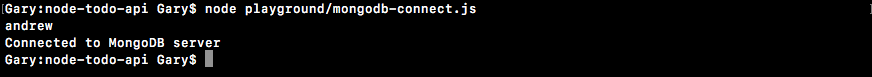

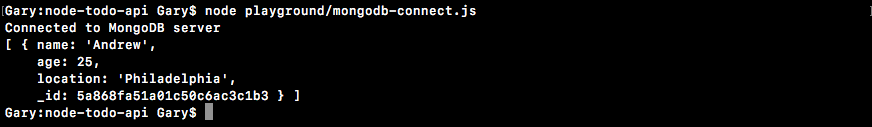

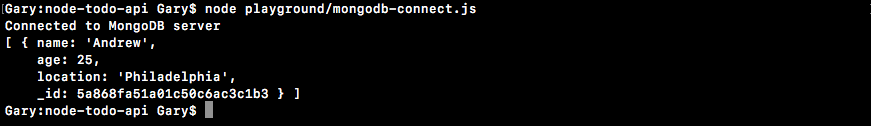

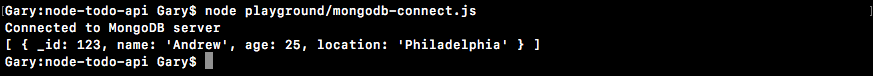

We can now go ahead and rerun the file inside of the Terminal using the up arrow key and the enter key:

We get our array of inserted documents, and we just have one. The name, age, and location properties all come from us, and the _id property comes from MongoDB.

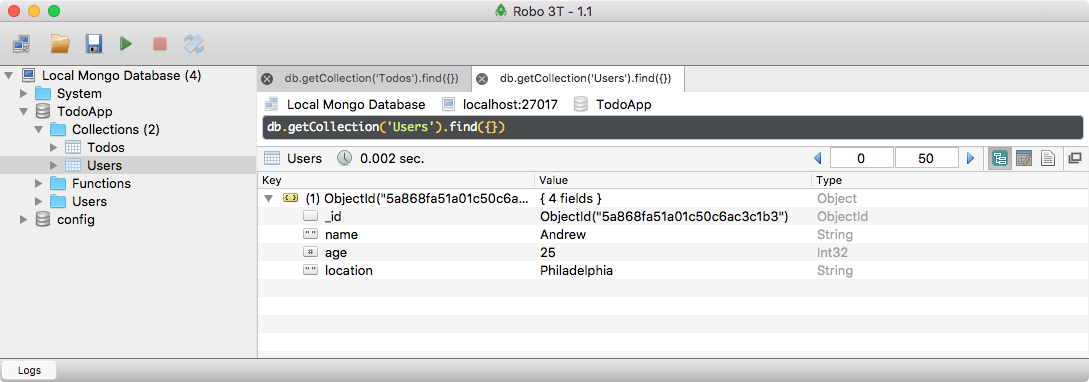

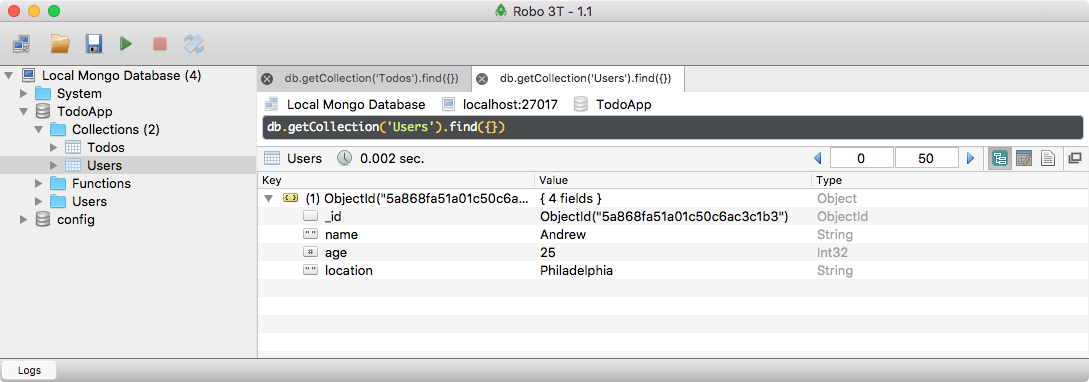

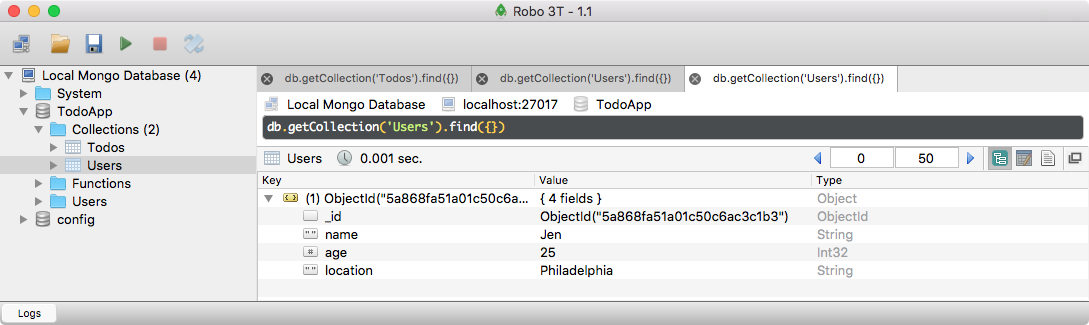

Next up, I want you to verify that it was indeed inserted by viewing it in Robomongo. In general, when you add a new collection or a new database, you can just right-click the connection itself, click Refresh, and then you should be able to see everything that was added:

As shown in the preceding screenshot, we have our Users collection. I can view the documents for Users. We get our one document with the name set to Andrew, age set to 25, and location set to Philadelphia. With this in place, we are now done. We've been able to connect to our MongoDB database using Node.js, and we've also learned how to insert documents using this mongo-native library. In the next section, we're going to take an in-depth look at ObjectIds, exploring exactly what they are and why they're useful.

Now that you have inserted some documents into your MongoDB collections, I want to take a moment to talk about the _id property in the context of MongoDB because it's a little different than the IDs that you're probably used to if you've used other database systems, like Postgres or MySQL.

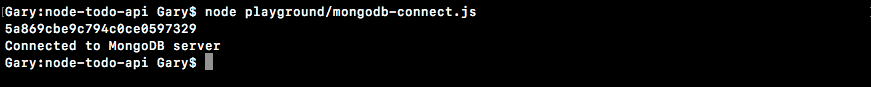

To kick off our discussion of the _id property, let's go ahead and rerun the mongodb-connect file. This is going to insert a new document into the Users collection, like we've defined in the db.collection line. I'm going to go ahead and do that by running the file through the node. It's in the playground folder, and the file itself is called mongodb-connect.js:

node playground/mongodb-connect.js

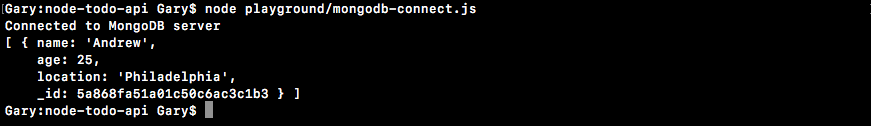

I'm going to run the command, and we're going to print out the document that got inserted:

As we've seen in the past, we get our three attributes as well as the one added by Mongo.

The first thing you'll notice about this is that it is not an auto incrementing integer, kind of like it is for Postgres or MySQL, where the first record has an ID of 1 and the second one has an ID of 2. Mongo does not use this approach. Mongo was designed to scale out really easily. Scaling out means that you can add on more database servers to handle that extra load.

Imagine you have a web app that gets about 200 users a day and your current servers are ready for that traffic. Then, you get picked up by some news outlet and 10,000 people flood your site. With MongoDB, it's really easy to kick up new database servers to handle that extra load. When we use a randomly generated ID, we don't need to constantly communicate with the other database servers to check what the highest incrementing value is. Is it 7? Is it 17? It doesn't really matter; we're simply going to generate a new random ObjectId and use that for the document's unique identifier.

Now, the ObjectId itself is made up of a few different things. It's a 12-byte value. The first four bytes are a timestamp; we'll talk about that later. That means that we have a timestamp built into the data that refers to the moment in time the ID was created. This means that in our documents, we don't need to have a createdAt field; it's already encoded in the ID.

The next three bytes are machine identifiers. This means that if two computers generate ObjectIds, their machine ID is going to be different, and this is going to ensure that the ID is unique. Next up, we have two bytes, the process ID, which is just another way to create a unique identifier. Last up, we have a 3-byte counter. This is similar to what MySQL would do. This is only 3 bytes of the ID. As we have already mentioned, we have a timestamp which is going to be unique; a machine identifier; a process ID; and lastly, just a random value. That is what makes up an ObjectId.

The ObjectId is the default value for _id. If nothing is provided, you can indeed do whatever you like with that property. For example, inside of the mongodb-connect file, I can specify an _id property. I'm going to give it a value, so let's go with 123; add a comma at the end; and that is perfectly legal:

db.collection('Users').insertOne({

_id: 123,

name: 'Andrew',

age: 25,

location: 'Philadelphia'

}

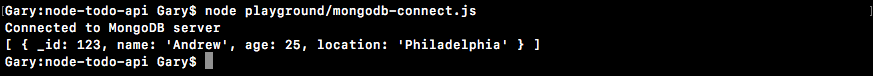

We can save the file, and rerun the script using the up arrow key and the enter key:

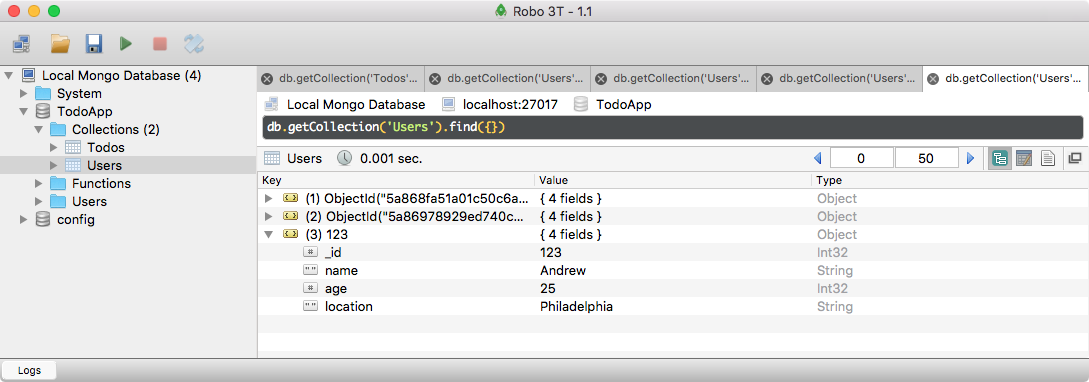

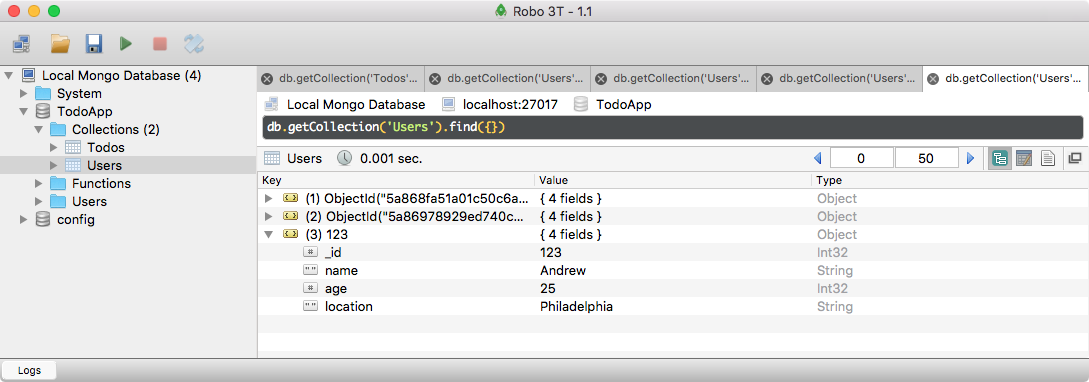

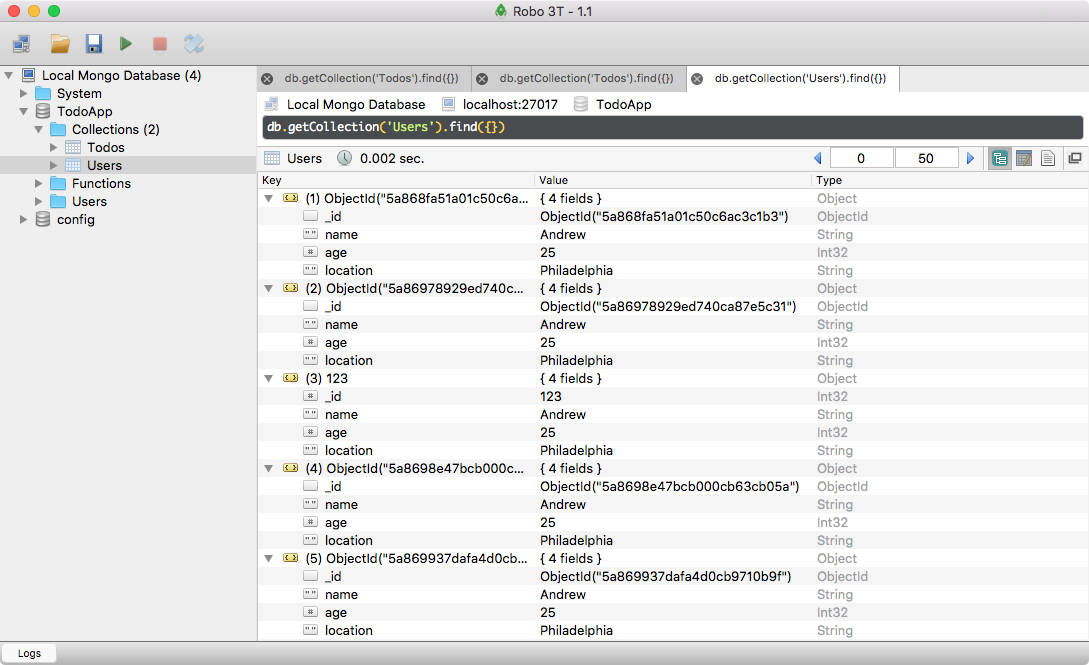

We get our record, where the _id property is 123. The ObjectId is the default way MongoDB creates IDs, but you can do anything you like for ID creation. Inside of Robomongo, we can give our Users collection a refresh, and we get our documents:

We have the one we created in the previous section and the two we just made now, all with a unique identifier. This is why unique IDs are really important. In this example, we have three properties: name, age and location, and they're the same for all the records. This is a reasonable thing to do. Imagine two people need to do the same thing, like buy groceries. That string alone is not going to be enough to uniquely identify a Todo. ObjectIds, on the other hand, are going to be unique, and that is what we're going to use to associated things like Todos with things like Users.

Next up, I want to take a look at some things we can do with the ID inside of our code. As I mentioned earlier, a timestamp is embedded inside of here, and we can actually pull that out. Inside of Atom, what we're going to do is remove the _id property. The timestamp is only going to be available when you're using the ObjectId. Then, inside of our callback, we can go ahead and print the timestamp to the screen.

db.collection('Users').insertOne({

name: 'Andrew',

age: 25,

location: 'Philadelphia'

}, (err, result) => {

if(err) {

return console.log('Unable to insert user', err);

}

console.log(result.ops);

});

If you remember, result.ops is an array of all the documents that got inserted. We're only inserting one, so I'm going to access the first item in the array, and then we're going to access the _id property. This is going to do exactly what you might think:

console.log(result.ops[0]._id);

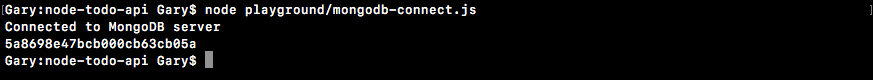

If we save the file and rerun the script over from the Terminal, all we get is the ObjectId printing to the screen:

Now though, we can call a method on the _id property.

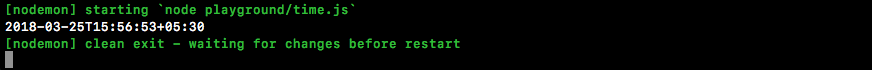

What we're going to call is .getTimestamp. The getTimestamp is a function, but it doesn't take any arguments. It simply returns the timestamp that the ObjectId was created at:

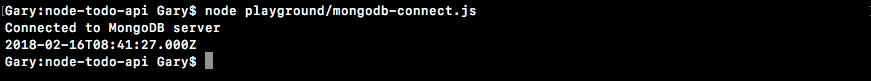

console.log(result.ops[0]._id.getTimestamp());

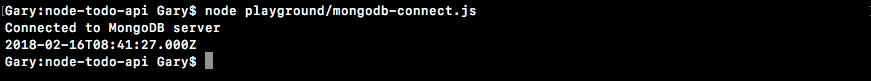

Now, if we go ahead and rerun our program, we get a timestamp:

In the preceding screenshot, I can see that the ObjectId was created on February 16th 2016 at 08:41 Z, so this timestamp is indeed correct. This is a fantastic way to figure out exactly when a document was created.

Now, we don't have to rely on MongoDB to create our ObjectIds. Inside of the MongoDB library, they actually give us a function we can run to make an ObjectId whenever we like. For the moment, let's go ahead and comment out our call to insert one.

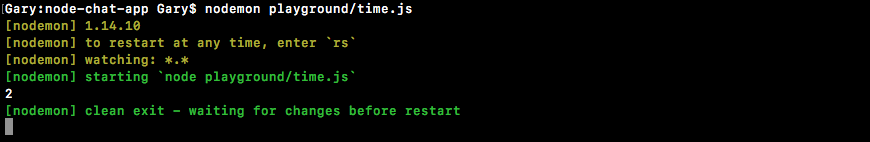

At the very top of the file, we're going to change our import statement to load in something new off of MongoDB, and we're going to do this using an ES6 feature known as object destructuring. Let's take a quick second to talk about that before we actually go ahead and use it.

Object destructuring lets you pull out properties from an object in order to create variables. This means that if we have an object called user and it's set equal to an object with a name property set to andrew and an age property set to 25, as shown in the following code:

const MongoClient = require('mongodb').MongoClient;

var user = {name: 'andrew', age: 25};

We can easily pull out one of these into a variable. Let's say, for example, we want to grab name and create a name variable. To do that using object destructuring in ES6, we're going to make a variable and then we're going to wrap it inside of curly braces. We're going to provide the name we want to pull out; this is also going to be the variable name. Then, we're going to set it equal to whatever object we want to destructure. In this case, that is the user object:

var user = {name: 'andrew', age: 25};

var {name} = user;

We have successfully destructured the user object, pulling off the name property, creating a new name variable, and setting it equal to whatever the value is. This means I can use the console.log statement to print name to the screen:

var user = {name: 'andrew', age: 25};

var {name} = user;

console.log(name);

I'm going to rerun the script and we get andrew, which is exactly what you'd expect because that is the value of the name property:

ES6 destructuring is a fantastic way to make new variables from an object's properties. I'm going to go ahead and delete this example, and at the top of the code, we're going to change our require statement so that it uses destructuring.

Before we add anything new, let's go ahead and take the MongoClient statement and switch it to destructuring; then, we'll worry about grabbing that new thing that's going to let us make ObjectIds. I'm going to copy and paste the line and comment out the old one so we have it for reference.

// const MongoClient = require('mongodb').MongoClient;

const MongoClient = require('mongodb').MongoClient;

What we're going to do is remove our .MongoClient call after require. There's no need to pull off that attribute because we're going to be using destructuring instead. That means over here we can use destructuring, which requires us to add our curly braces, and we can pull off any property from the MongoDB library.

const {MongoClient} = require('mongodb');

In this case, the only property we had was MongoClient. This creates a variable called MongoClient, setting it equal to the MongoClient property of require('mongodb'), which is exactly what we did in the previous require statement.

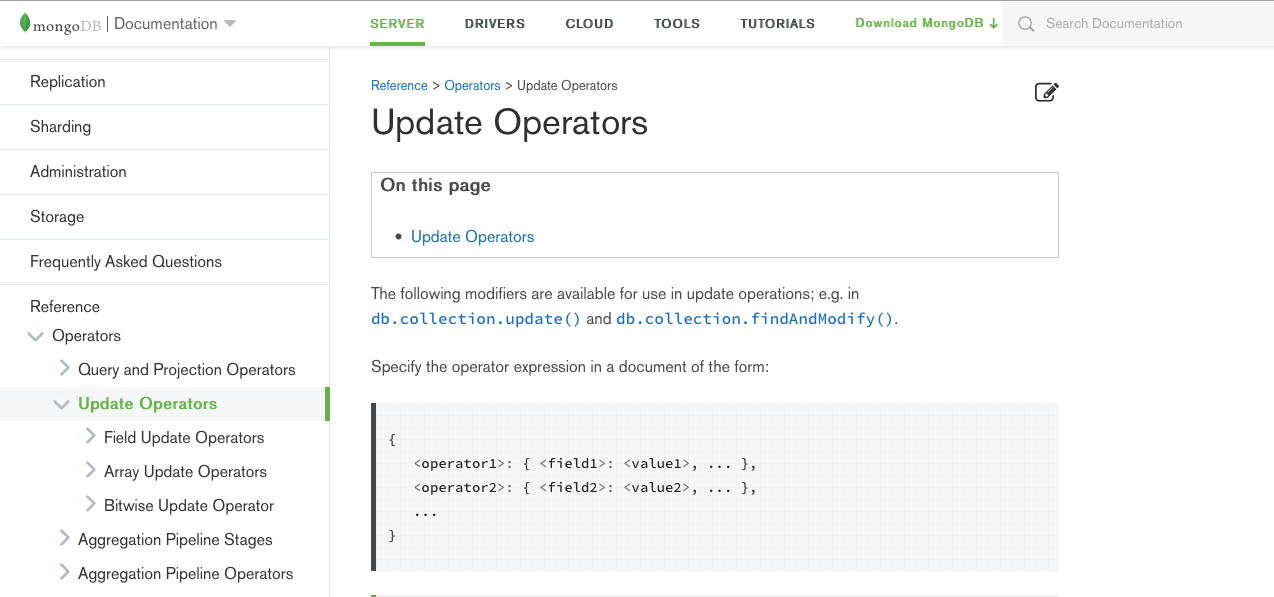

Now that we have some destructuring in place, we can easily pull more things off of MongoDB. We can add a comma and specify something else we want to pull off. In this case, we're going to pull off uppercase, ObjectID.

const {MongoClient, ObjectID} = require('mongodb');

This ObjectID constructor function lets us make new ObjectIds on the fly. We can do anything we like with them. Even if we're not using MongoDB as our database, there is some value in creating and using ObjectIds to uniquely identify things. Next, we can make a new ObjectId by first creating a variable. I'll call it obj, and we'll set it equal to new ObjectID, calling it as a function:

const {MongoClient, ObjectID} = require('mongodb');

var obj = new ObjectID();

Using the new keyword, we can create a new instance of ObjectID. Next up, we can go ahead and log that to the screen using console.log(obj). This is a regular ObjectId:

console.log(obj);

If we rerun the file over from the Terminal, we get exactly what you'd expect:

We get an ObjectId-looking thing. If I rerun it again, we get a new one; they are both unique:

Using this technique, we can incorporate ObjectIds anywhere we like. We could even generate our own, setting them as the _id property for our documents, although I find it much easier to let MongoDB handle that heavy lifting for us. I'm going to go ahead and remove the following two lines since we won't actually be using this code in the script:

var obj = new ObjectID(); console.log(obj);

We have learned a bit about ObjectIds, what they are, and why they're useful. In the following sections, we're going to be taking a look at other ways we can work with MongoDB. We'll learn how to read, remove, and update our documents.

Now that you know how to insert data into your database, let's go ahead and talk about how we can fetch data out of it. We're going to be using this technique in the Todo API. People are going to want to populate a list of all the Todo items they need, and they might want to fetch the details about an individual Todo item. All of this is going to require that we can query the MongoDB database.

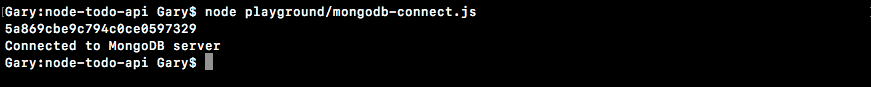

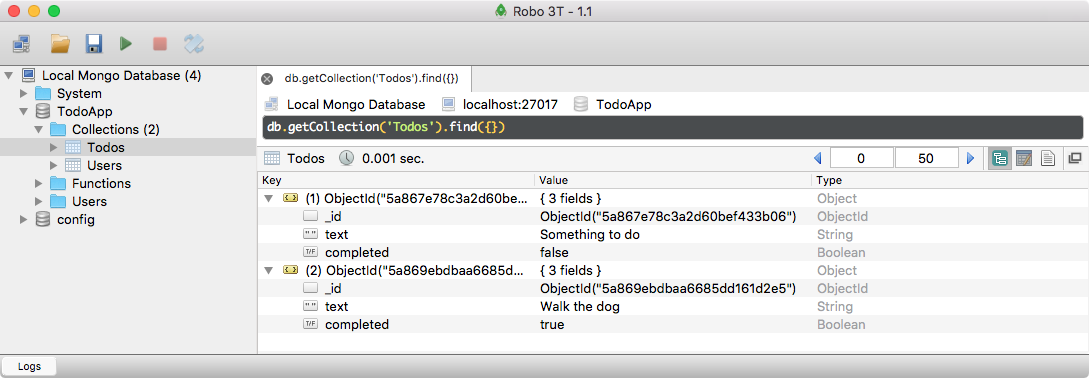

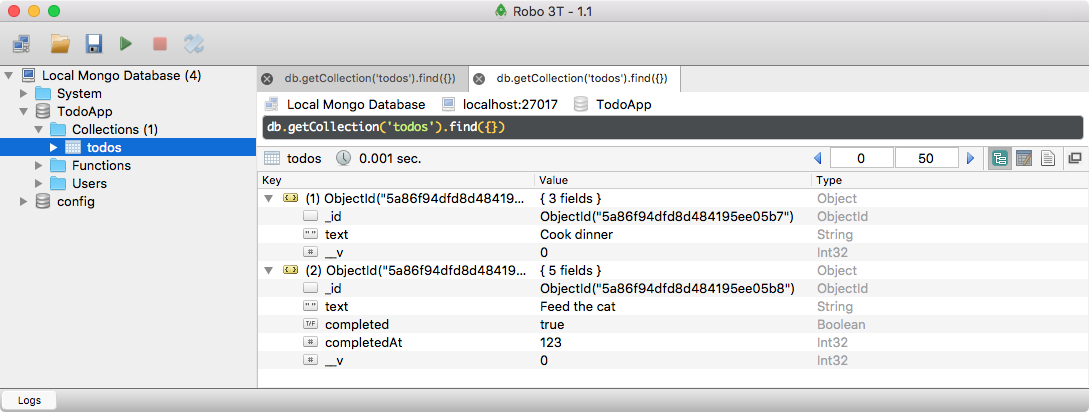

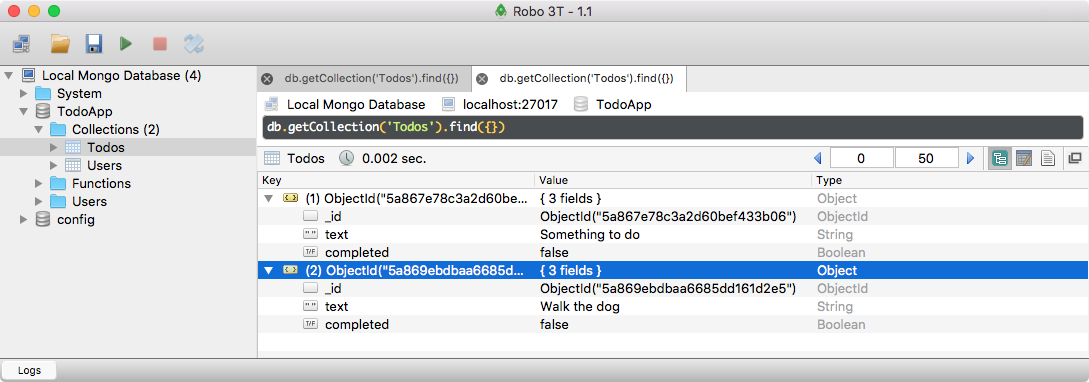

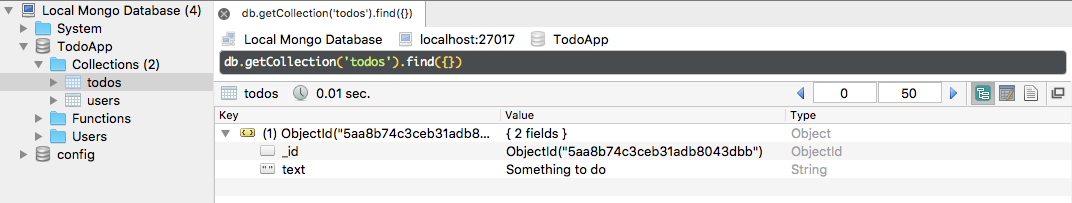

Now, we're going to create a new file based off of mongodb-connect. In this new file, instead of inserting records, we'll fetch records from the database. I'm going to create a duplicate, calling this new file mongodb-find, because find is the method we're going to use to query that database. Next, we can go ahead and remove all of the commented-out code that currently inserts records. Let's get started by trying to fetch all of the Todos out of our Todos collection. Now, if I head over to Robomongo and open up the Todos collection, we have just one record:

In order to make this querying a little more interesting, we're going to go ahead and add a second one. Right in the Robomongo window, I can click Insert Document. Robomongo can delete, insert, update, and read all of your documents, and this makes it a fantastic tool for debugging. We can add a new document on the fly, with a text property equal to Walk the dog, and we can also tack on a completed value. I'm going to set completed equal to false:

{

text : "Walk the dog",

completed : false

}

Now by default, we're not going to provide an _id prop. This is going to let MongoDB automatically generate that ObjectId, and right here we have our two Todos:

With this in place, let's go ahead and run our first query inside of Atom.

In Atom, what we're going to do is access the collection, just like we did inside of the mongodb-connect file using db.collection, passing in the collection name as the string. This collection is going to be the Todos collection. Now, we're going to go ahead and use a method available on collections called find. By default, we can call find with no arguments:

db.collection('Todos').find();

This means we're not providing a query, so we're not saying we want to fetch all Todos that are completed or not completed. We're just saying we want to fetch all Todos: everything, regardless of its values. Now, calling find is only the first step. find returns a MongoDB cursor, and this cursor is not the actual documents themselves. There could be a couple of thousand, and that would be really inefficient. It's actually a pointer to those documents, and the cursor has a ton of methods. We can use those methods to get our documents.

One of the most common cursor methods we're going to be using is .toArray. It does exactly what you think it does. Instead of having a cursor, we have an array of the documents. This means we have an array of objects. They have ID properties, text properties, and completed properties. This toArray method gets us exactly what we want back, which is the documents. toArray returns a promise. This means we can tack on a then call, we can add our callback, and when things go right, we can do something like print those documents to the screen.

db.collection('Todos').find().toArray().then((docs) => {

});

We're going to get the documents as the first and only argument here, and we can also add an error handler. We'll get passed an error argument, and we can simply print something to the screen like console.log(Unable to fetch todos); as the second argument, we'll pass in the err object:

db.collection('Todos').find().toArray().then((docs) => {

}, (err) => {

console.log('Unable to fetch todos', err);

});

Now, for the success case, what we're going to do is print the documents to the screen. I'm going to go ahead and use console.log to print a little message, Todos, and then I'll call console.log again. This time, we'll be using the JSON.stringify technique. I'll be passing in the documents, undefined for our filter function and 2 for our spacing.

db.collection('Todos').find().toArray().then((docs) => {

console.log('Todos');

console.log(JSON.stringify(docs, undefined, 2));

}, (err) => {

console.log('Unable to fetch todos', err);

});

We now have a script that is capable of fetching the documents, converting them into an array, and printing them to the screen. Now, for the time being, I'm going to comment out the db.close method. Currently, that would interfere with our previous bit of code. Our final code would look as follows:

//const MongoClient = require('mongodb').MongoClient;

const {MongoClient, ObjectID} = require('mongodb');

MongoClient.connect('mongodb://localhost:27017/TodoApp', (err, client) => {

if(err){

console.log('Unable to connect to MongoDB server');

}

console.log('Connected to MongoDB server');

const db = client.db('TodoApp');

db.collection('Todos').find().toArray().then((docs) => {

console.log('Todos');

console.log(JSON.stringify(docs, undefined, 2));

}, (err) => {

console.log('Unable to fetch todos', err);

});

//client.close();

});

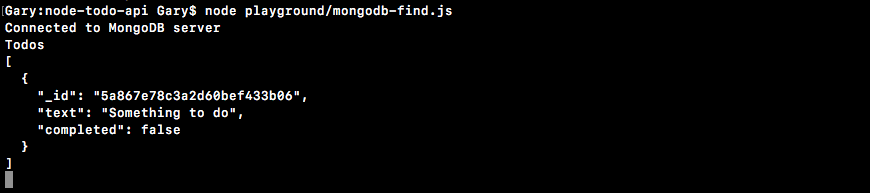

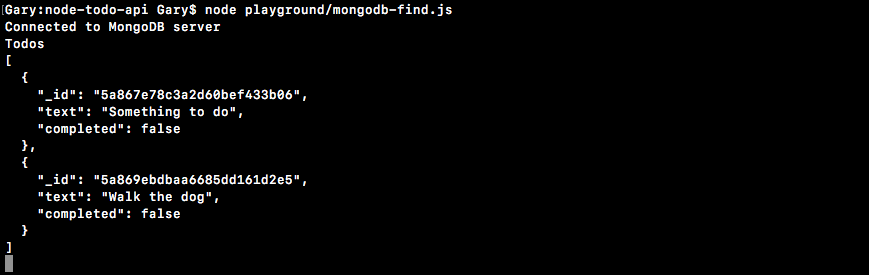

Save the file and run it from the Terminal. Inside of the Terminal, I'm going to go ahead and run our script. Obviously, since we connected to the database with Robomongo, it is running somewhere; it's running in this other tab. In the other tab, I can run the script. We're going to run it through node; it's in the playground folder, and the file itself is called mongodb-find.js:

node playground/mongodb-find.js

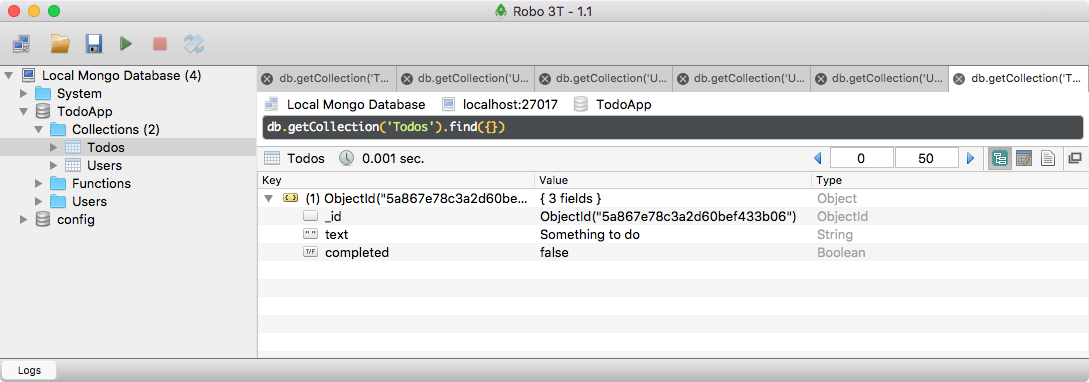

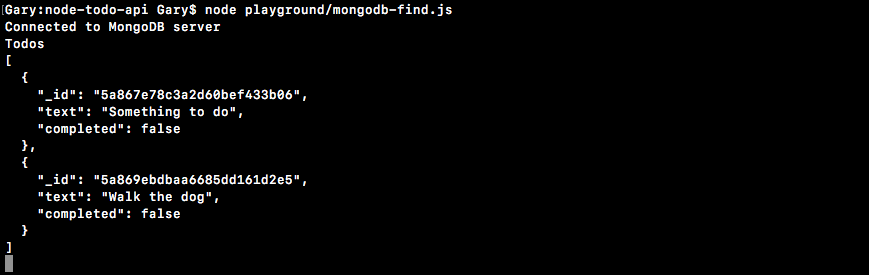

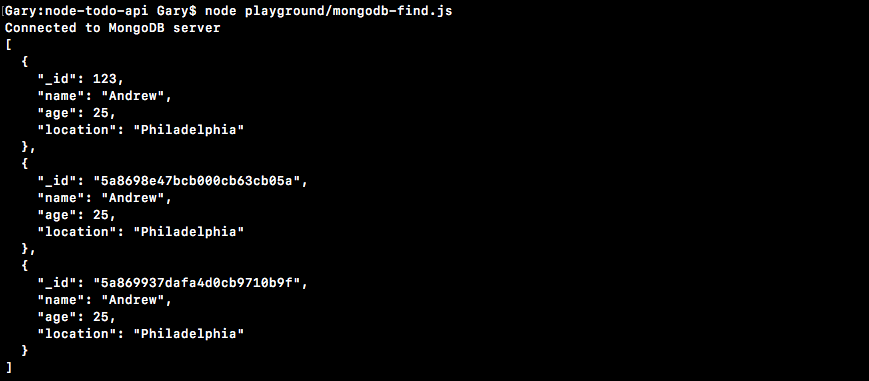

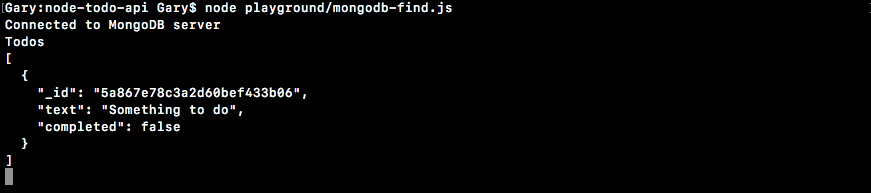

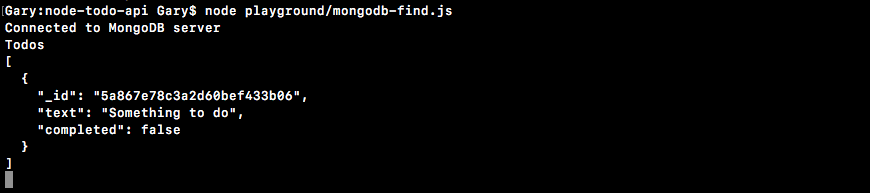

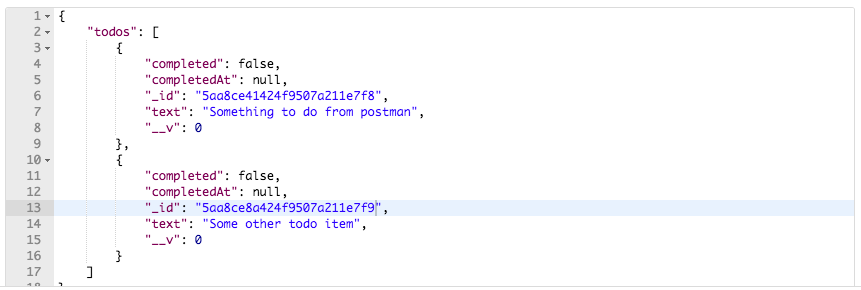

When I execute this file, we're going to get our results:

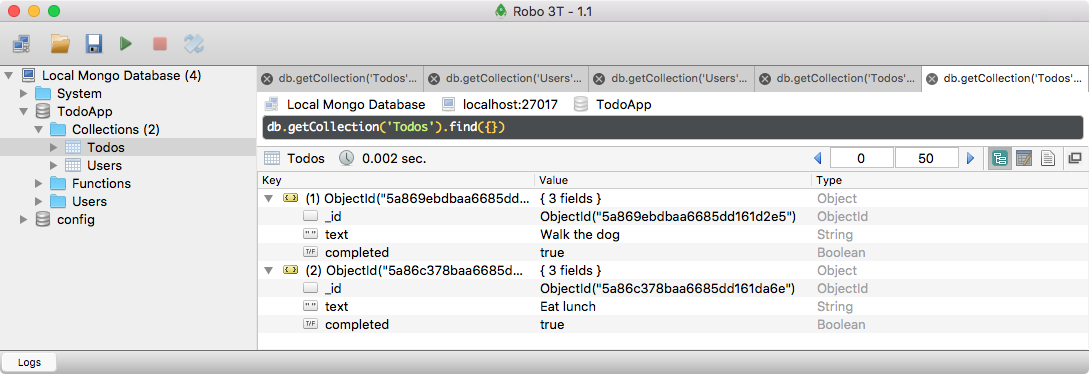

We have our Todos array with our two documents. We have our _id, our text properties, and our completed Boolean values. We now have a way to query our data right inside of Node.js. Now, this is a very basic query. We fetch everything in the Todos array, regardless of whether or not it has certain values.

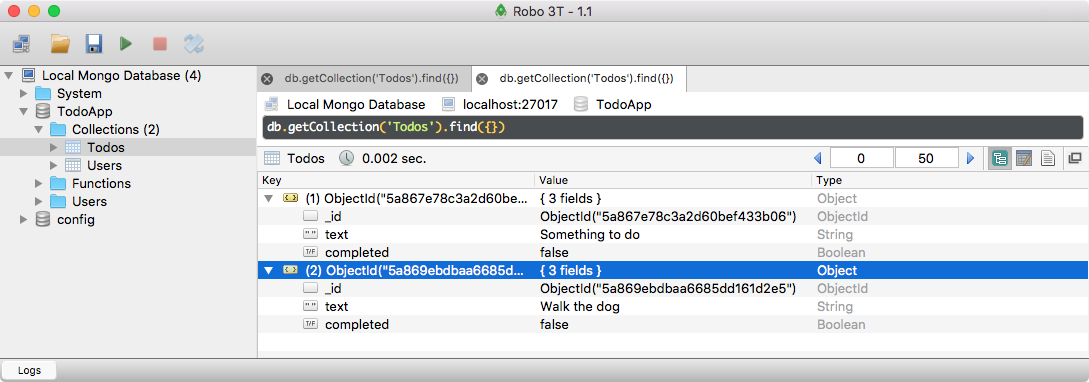

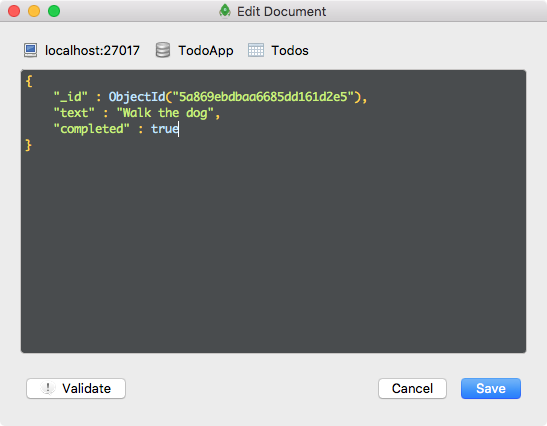

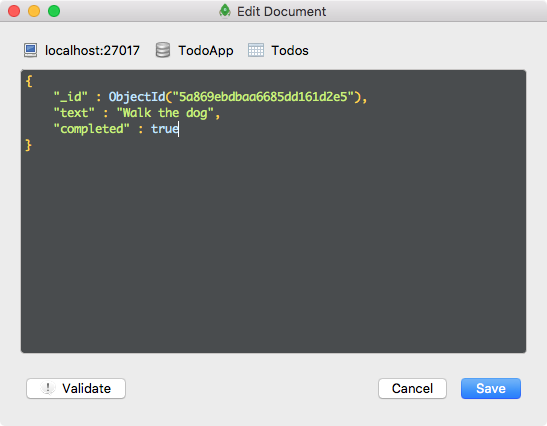

In order to query based on certain values, let's go ahead and switch up our Todos. Currently, both of them have a completed value equal to false. Let's go ahead and change the Walk the dog completed value to true so we can try to just query items that aren't completed. Over in Robomongo, I'm going to right-click the document and click Edit Document, and there we can edit the values. I'm going to change the completed value from false to true, and then I can save the record:

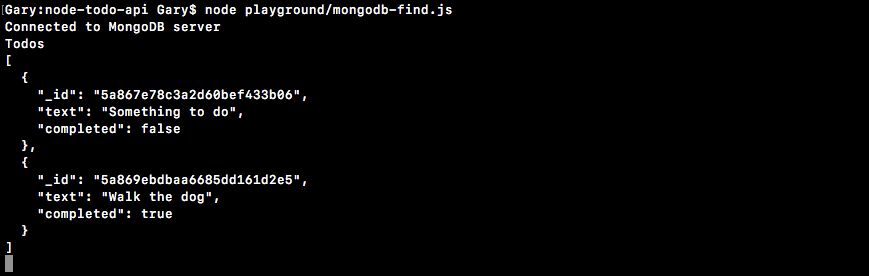

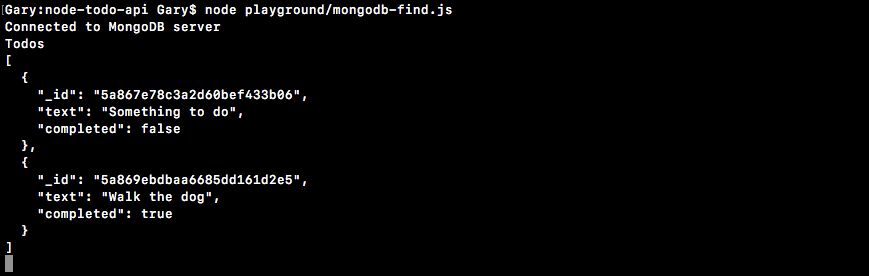

Inside of the Terminal, I can rerun the script to prove that it has changed. I'm going to shut down the script by running control + C, and then I can rerun it:

As shown in the preceding screenshot, we have our two Todos, one with a completed value of false and one with a completed value of true. By default, a Todo app is probably only going to show you the Todos collection you haven't completed. The ones you have completed, like Walk the dog, will probably be hidden, although they could be accessible if you clicked a button like Show all Todos. Let's go ahead and write a query that just fetches the Todos collection that have a completed status set to false.

To get this done, inside of Atom, we're going to make a change to how we call find. Instead of passing in 0 arguments, we're going to pass in 1. This is what's known as our query. We can start specifying how we want to query the Todos collection. For example, maybe we want to query only Todos that have a completed value equal to false. All we have to do to query by value is set up the key-value pairs, as shown here:

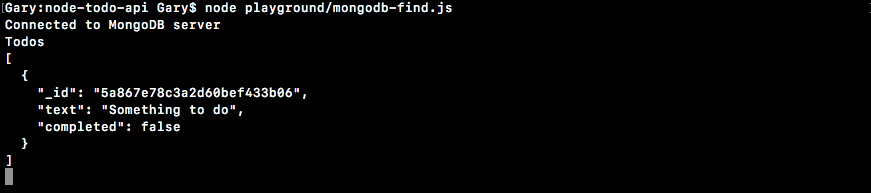

db.collection('Todos').find({completed: false}).toArray().then((docs) => {

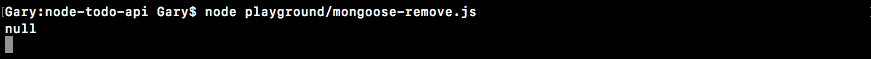

If I rerun our script over in the Terminal after shutting it down, we get just our one Todo item:

We have our item with the text equal to Something to do. It has a completed status of false, so it shows up. Our other Todo with a text property of Walk the dog is not showing up because that one has been completed. It doesn't match the query, so MongoDB does not return it. This is going to come in handy as we start querying our documents based off of completed values, text properties, or IDs. Let's take a quick moment to look at how we can query one of our Todos by ID.

The first thing we need to do is remove everything from our query object; we no longer want to query by the completed value. Instead, we're going to query by the _id property.

Now, in order to illustrate this, I'm going to grab the ID of the Todo with the completed value of false from the Terminal. I'm going to copy it using command + C. If you're on Windows or Linux, you might need to right-click after highlighting the ID, and click Copy text. Now that I have the text inside of the clipboard, I can head over to the query itself. Now, if we try to add the ID like this:

db.collection('Todos').find({_id: ''}).toArray().then((docs) => {

It is not going to work as expected because what we have inside of the ID property is not a string. It's an ObjectId, which means that we need to use the ObjectID constructor function that we imported previously in order to create an ObjectId for the query.

To illustrate how that's going to happen, I'm going to go ahead and indent our object. This is going to make it a little easier to read and edit.

db.collection('Todos').find({

_id: '5a867e78c3a2d60bef433b06'

}).toArray().then((docs) => {

Now, I'm going to remove the string and call new ObjectID. The new ObjectID constructor does take an argument: the ID, in this case, we have it stored as a string. This is going to work as expected.

db.collection('Todos').find({

_id: new ObjectID('5a867e78c3a2d60bef433b06');

})

What we're doing here is we're querying the Todos collection, looking for any records that have an _id property equal to the ID we have. Now, I can go ahead and save this file, give things a refresh by running the script again, and we'll get the exact same Todo:

I can go ahead and change it for the Walk the dog Todo by copying the string value, pasting that inside of the ObjectID constructor function, and rerunning the script. When I do this, I get the Walk the dog Todo returned because that was the ObjectId I queried.

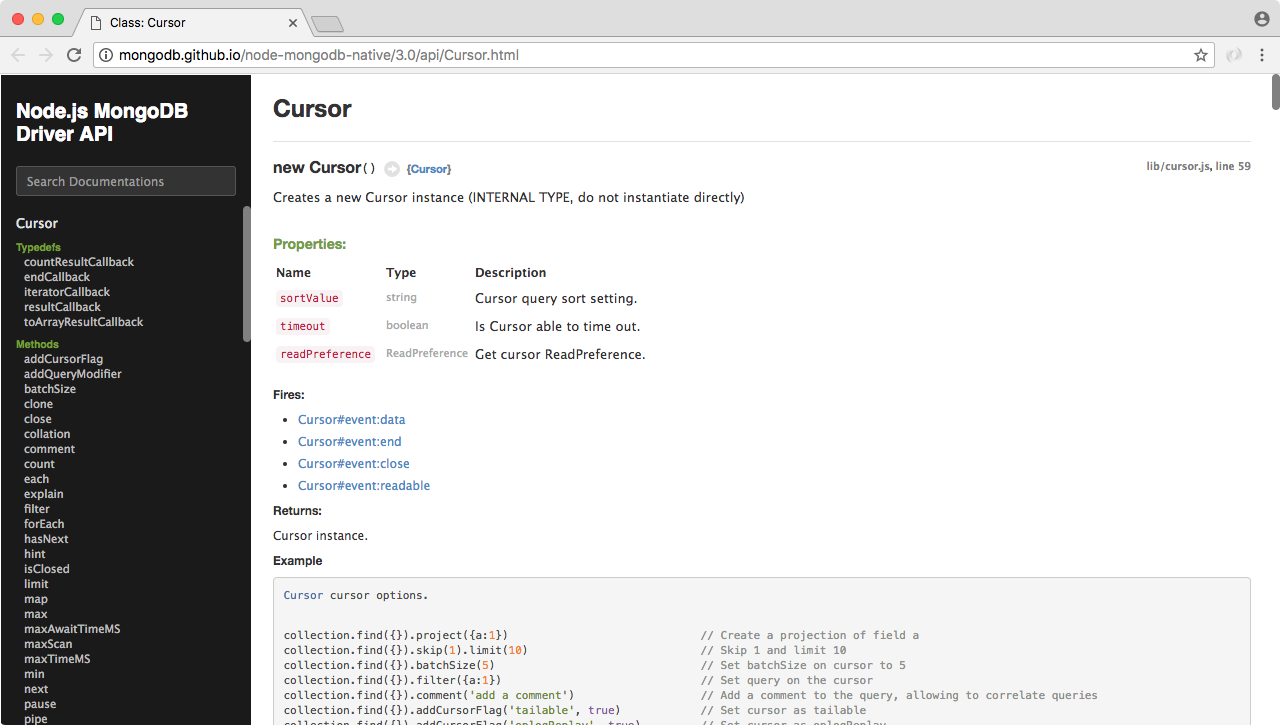

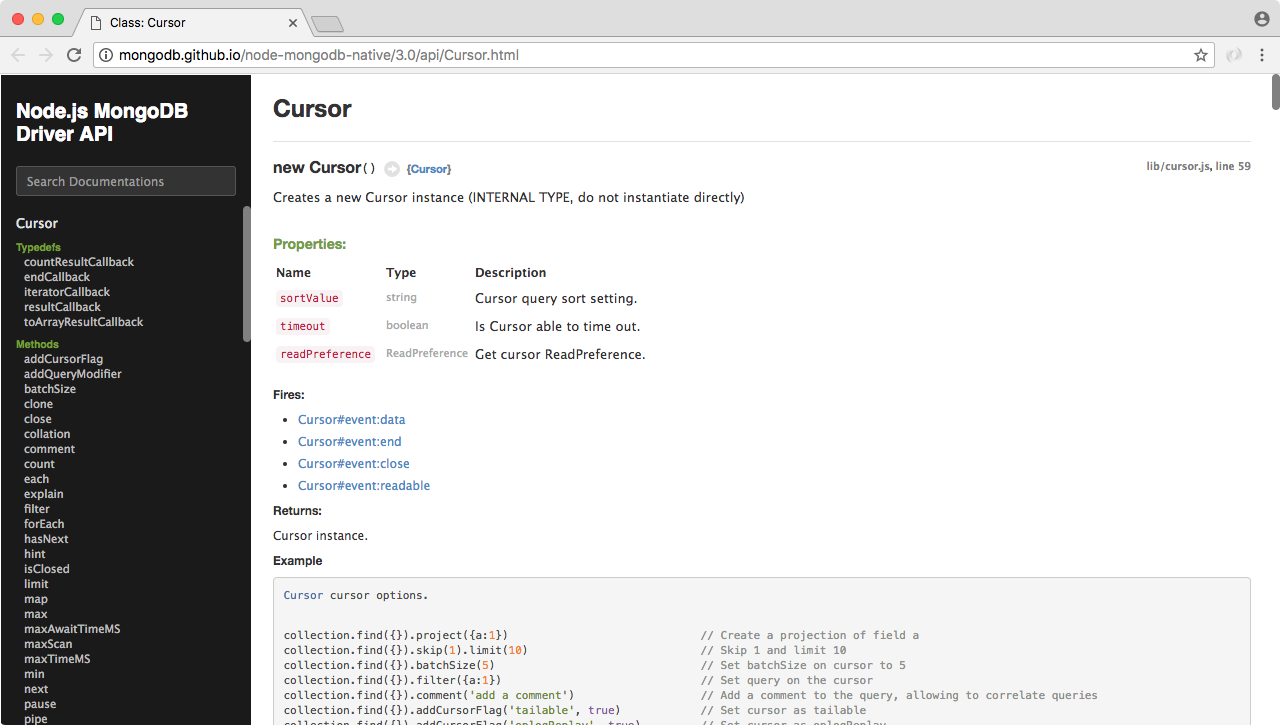

Now, querying in this fashion is one of the ways we'll be using find, but there are other methods other than toArray that are available on our cursors. We can explore other ones by heading over to the docs for the native driver. Inside of Chrome, have the MongoDB docs pulled up—these are the docs I showed you how to access in the previous chapter—and on the left-hand side, we have the Cursor section.

If you click that, we can view a list of all the methods available to us on that cursor:

This is what comes back from find. At the very bottom of the list, we have our toArray method. The one that we're going to look at right now is called count. From previous, you can go ahead and click count; it's going to bring you to the documentation; the documentation for the native driver is actually really good. There is a complete list of all the arguments that you can provide. Some of them are optional, some of them are required, and there is usually a real-world example. Next, we can figure out exactly how to use count.

Now, we're going to go ahead and implement count over inside of Atom. What I'm going to do is take the current query, copy it to the clipboard, and then comment it out. I'm going to go ahead and replace our call to toArray with a call to count. Let's go ahead and remove the query that we pass in to find. What we're going to do here is count up all of the Todos in the Todos collection. Instead of having a call to toArray, we're going to have a call to count instead.

db.collection('Todos').find({}).count().then((count) => {

As you saw inside of the examples for count, they call count like this: calling count, passing in a callback function that gets called with an error, or the actual count. You can also have a promise as a way to access that data, which is exactly what we did with toArray. In our case, instead of passing a callback function like this, we're going to use the promise instead. We already have the promise set up. All we need to do to fix this is change docs to count, and then we're going to remove the console.log caller where we print the docs to the screen. Right after we print Todos, we're going to print Todos count, with a colon passing in the value.

db.collection('Todos').find({}).count().then((count) => {

console.log('Todos count:');

}, (err) => {

console.log('Unable to fetch todos', err);

});

This is not a template string, but I am going to go ahead and swap it out with one, replacing the quotes with `. Now, I can pass in the count.

db.collection('Todos').find({}).count().then((count) => {

console.log(`Todos count: ${count}`);

}, (err) => {

console.log('Unable to fetch todos', err);

});

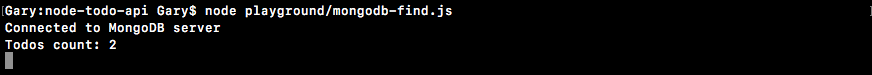

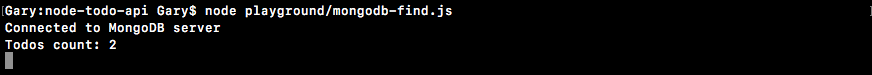

Now that we have this in place, we have a way to count up all of the Todos in the Todos collection. Inside the Terminal, I'm going to go ahead and shut down our previous script and rerun it:

We get Todos count too, which is correct. The cursor that we have, a call to find, returns everything in the Todos collection. If you count all of that up, you're going to get those two Todo items.

Once again, these are count and toArray; they're just a subset of all of the awesome methods you have available to you. We will be using other methods, whether it be the MongoDB native driver or, as you'll see later, the library Mongoose, but for now let's go ahead and do a challenge, given what you know.

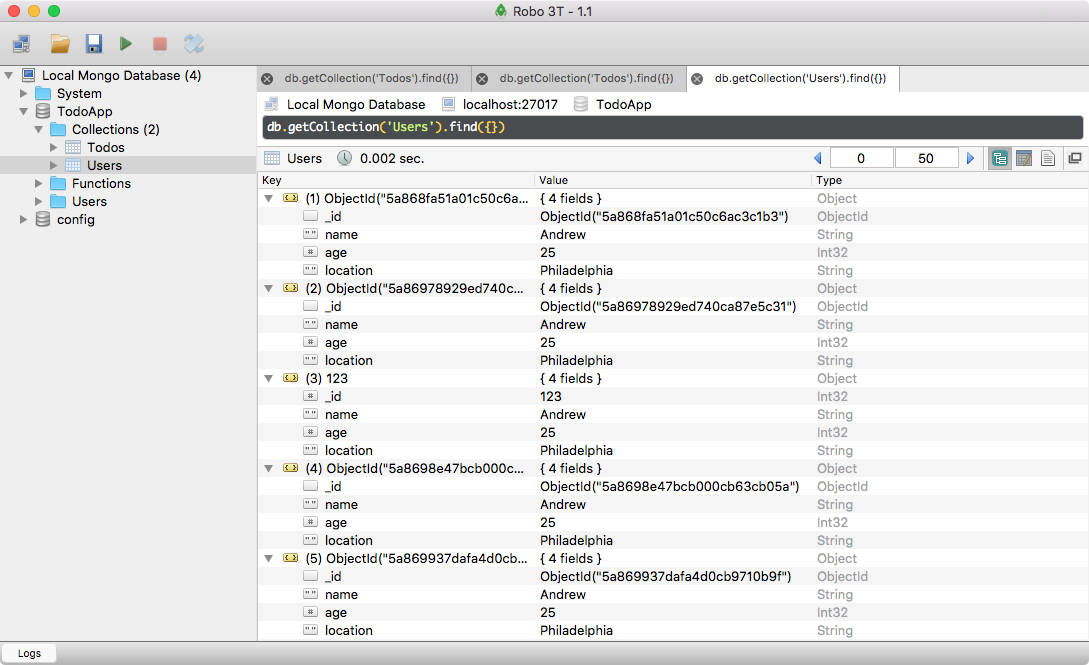

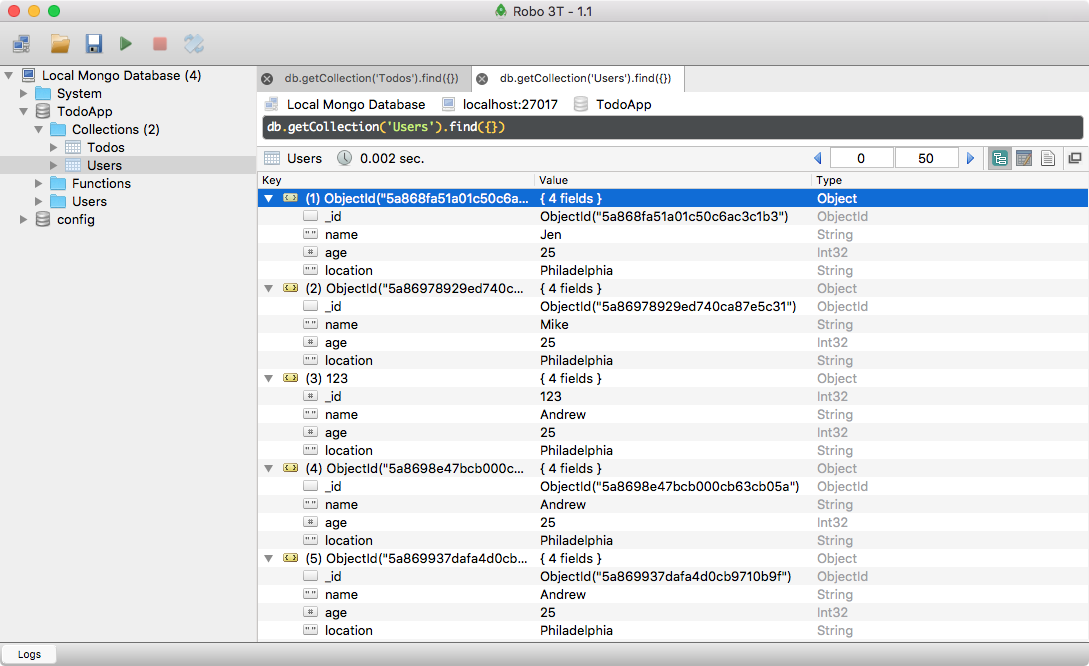

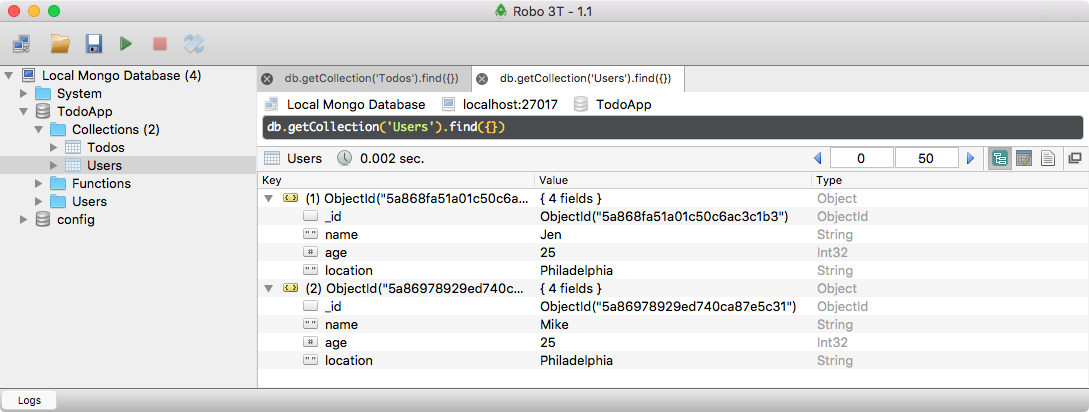

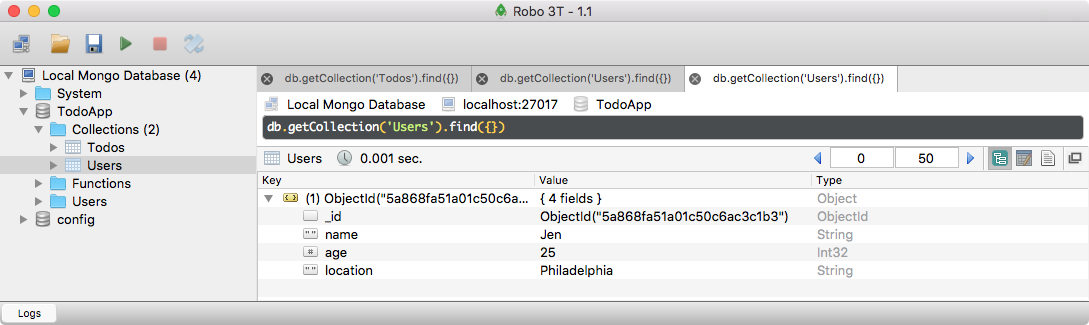

To get started, let's head into Robomongo, open up the Users collection, and take a look at all the documents we have inside of there. We currently have five. If you don't have the exact same number or yours are a little different, that's fine. I'm going to highlight them, right-click them, and click Expand Recursively. This is going to show me all of the key-value pairs for each document:

Currently, aside from the ID, they're all identical. The name's Andrew, the age is 25, and the location is Philadelphia. I'm going to tweak the name property for two of them. I'm going to right-click the first document, and change the name to something like Jen. Then, I'll go ahead and do the same thing for the second document. I'm going to edit that document and change the name from Andrew to Mike. Now I have one document with a name of Jen, one with Mike, and three with Andrew.

We're going to query our users, looking for all of the users with the name equal to the name that you provided in the script. In this case, I'm going to try to query for all documents in the Users collection where the name is Andrew. Then, I'm going to print them into the screen, and I will expect to get three back. The two with the names Jen and Mike should not show up.

The first thing we need to do is fetch from the collection. This is going to be the Users collection as opposed to the Todos collection we've used in this chapter. In the db.collection, we're looking for the Users collection and now we're going to go ahead and call find, passing in our query. We want a query, fetching all documents where the name is equal to the string Andrew.

db.collection('Users').find({name: 'Andrew'})

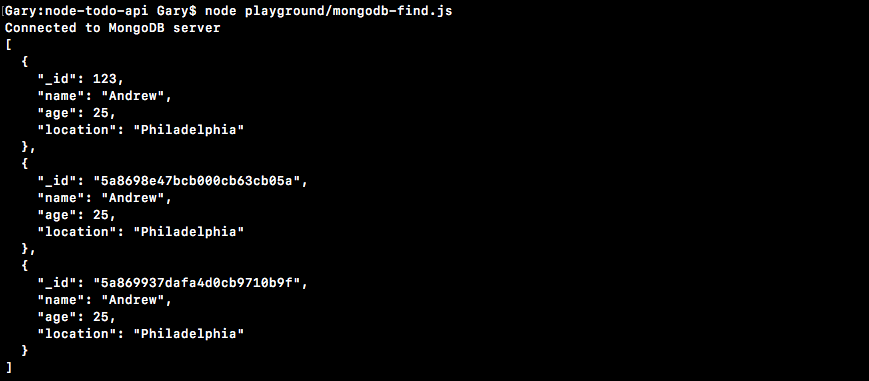

This is going to return the cursor. In order to actually get the documents, we have to call toArray. We now have a promise; we can attach a then call onto toArray to do something with the docs. The documents are going to come back as the first argument in our success handler, and right inside of the function itself we can print the docs to the screen. I'm going to go ahead and use console.log(JSON.stringify()), passing in our three classic arguments: the object itself, docs, undefined, and 2 for formatting:

db.collection('Users').find({name: 'Andrew'}).toArray().then((docs) => {

console.log(JSON.stringify(docs, undefined, 2));

});

With this in place, we have now done. We have a query, and it should work. We can test it by running it from the Terminal. Inside the Terminal, I'm going to go ahead and shut down the previous connection and rerun the script:

When I do this, I get my three documents back. All of them have a name equal to Andrew, which is correct because of the query we set up. Notice the documents with a name equal to Mike or Jen are nowhere to be found.

We now know how to insert and query data from the database. Up next, we're going to take a look at how we can remove and update documents.

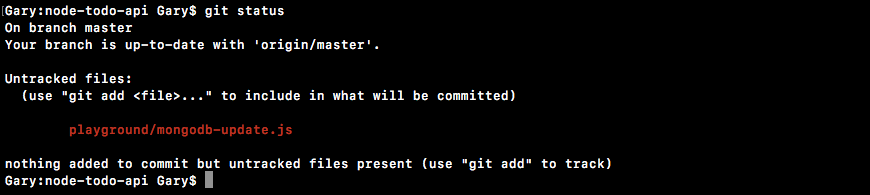

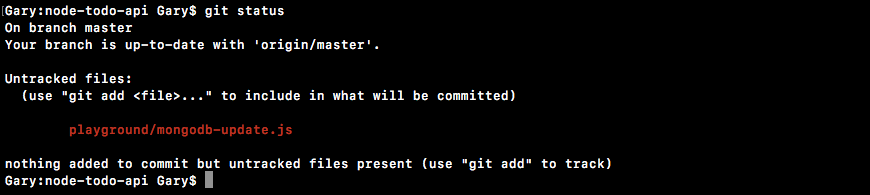

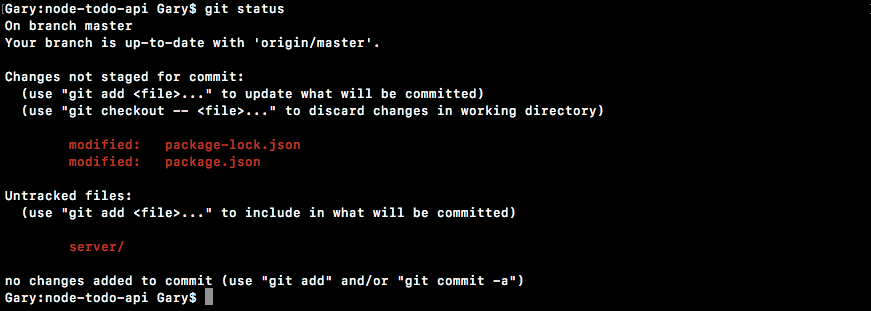

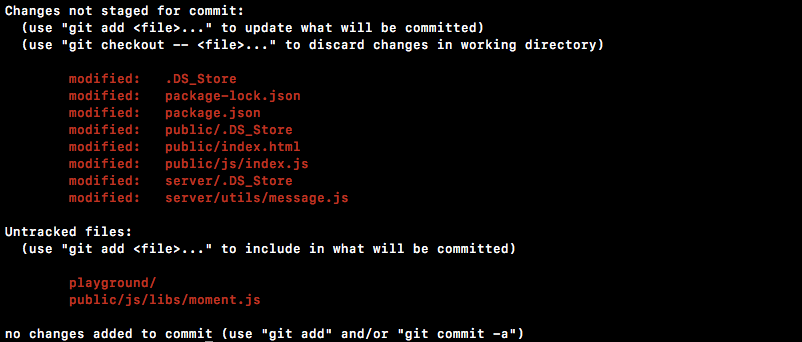

Before we go any further, I do want to add version control to this project. In this section, we're going to create a new repo locally, make a new GitHub repository, and push our code to that GitHub repository. If you're already familiar with Git or GitHub, you can go ahead and do that on your own; you don't need to go through this section. If you're new to Git and it doesn't make sense just yet, that's also fine. Simply follow along, and we'll go through the whole process.

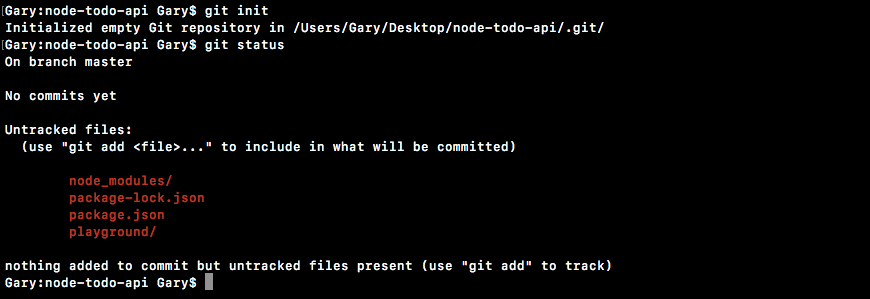

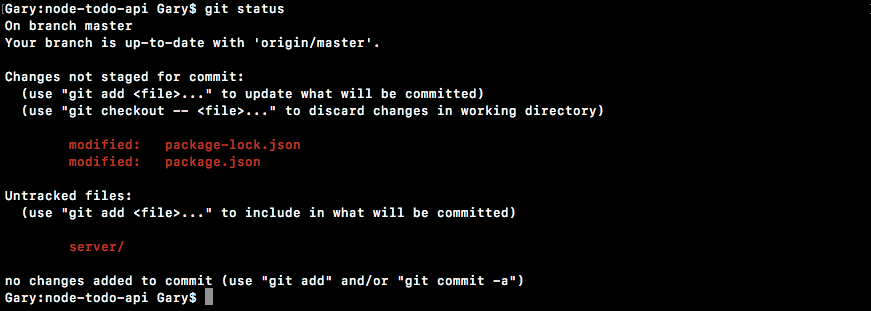

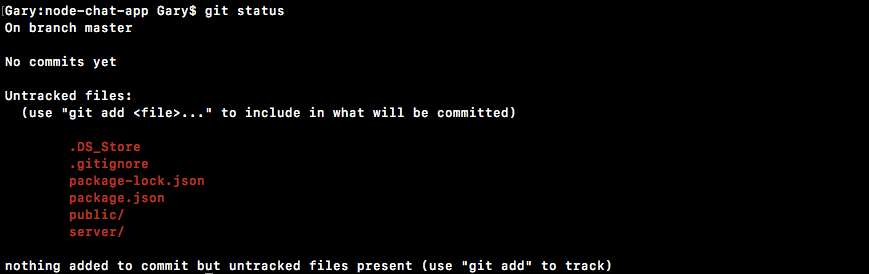

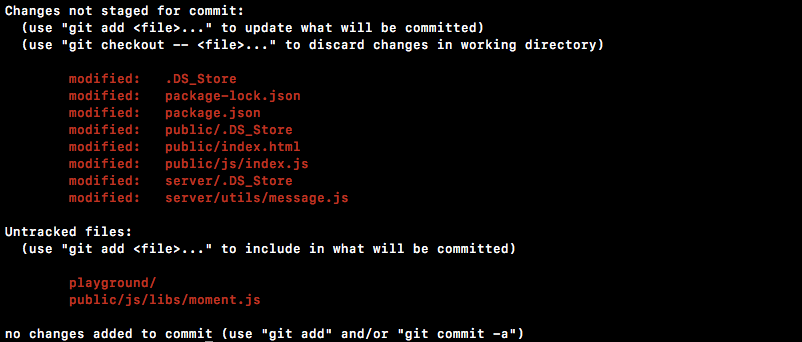

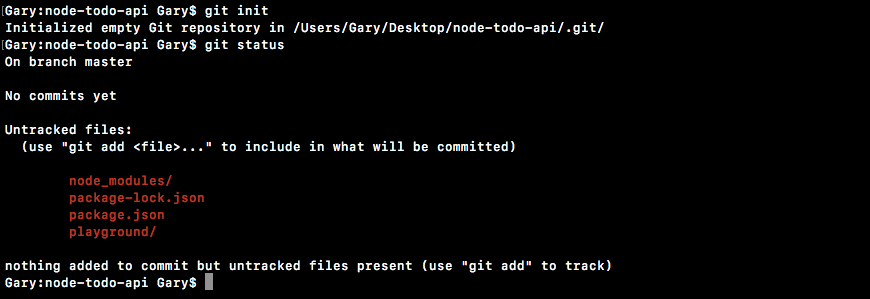

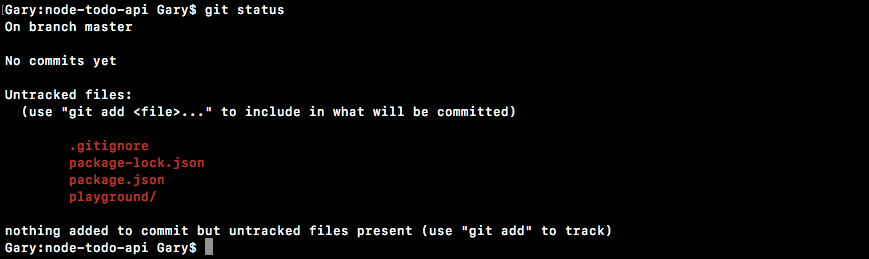

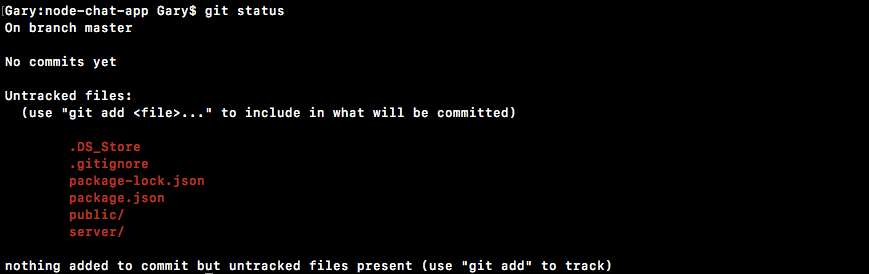

This section is going to be really simple; nothing MongoDB- related here. To get started, I am going to go ahead and initialize a new Git repository from the Terminal by using git init. This is going to initialize a new repository, and I can always run git status like this to take a look at the files that are untracked:

Here we have our playground folder, which we want to add under version control, and we have package.json. We also have node_modules. We do not want to track this directory. This contains all of our npm libraries. To ignore node_modules, in Atom we're going to make the .gitignore file in the root of our project. If you remember, this lets you specify files and folders that you want to leave out of your version control. I'm going to create a new file called .gitignore. In order to ignore the node_modules directory, all we have to do is type it exactly as it's shown here:

node_modules/

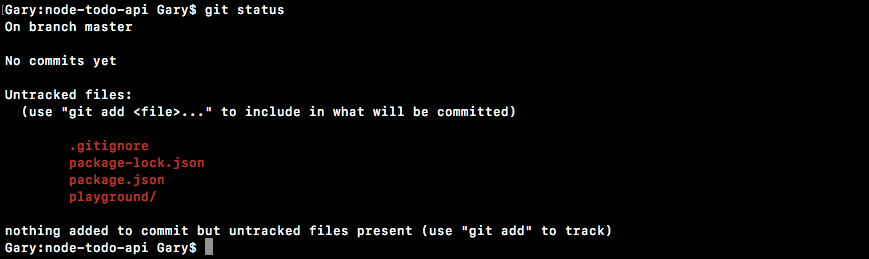

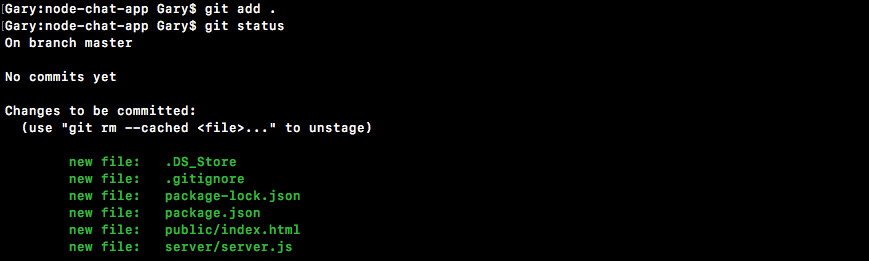

I'm going to save the file and rerun git status from the Terminal. We get the .gitignore folder showing up, and the node_modules folder is nowhere in sight:

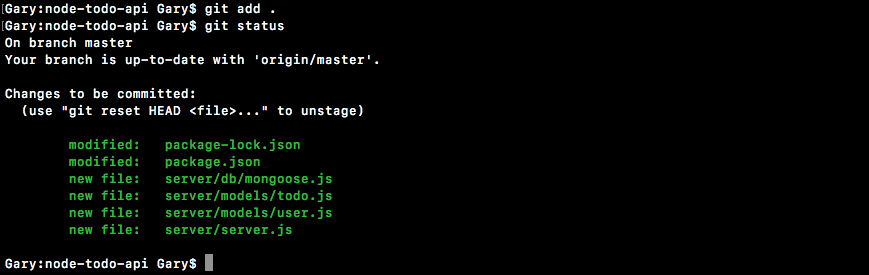

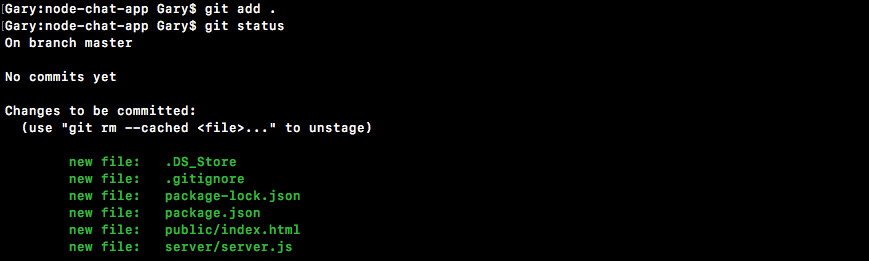

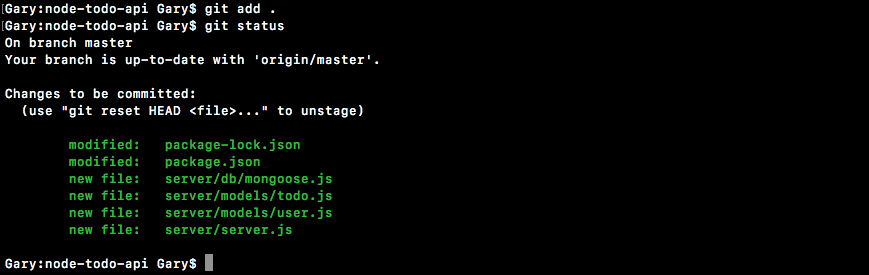

The next thing we're going to do is make our first commit, using two commands. First up, I'm going to use git add . to add everything to the next commit. Then, I can make the commit using git commit with the -m flag. A good message for this commit would be Init commit:

git add .

git commit -m 'Init commit'

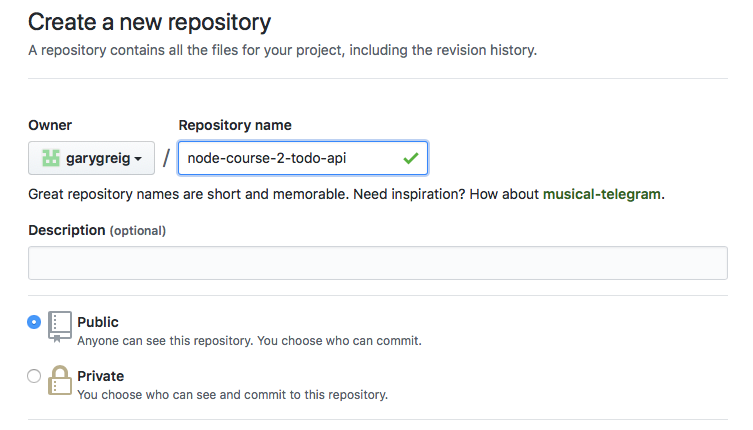

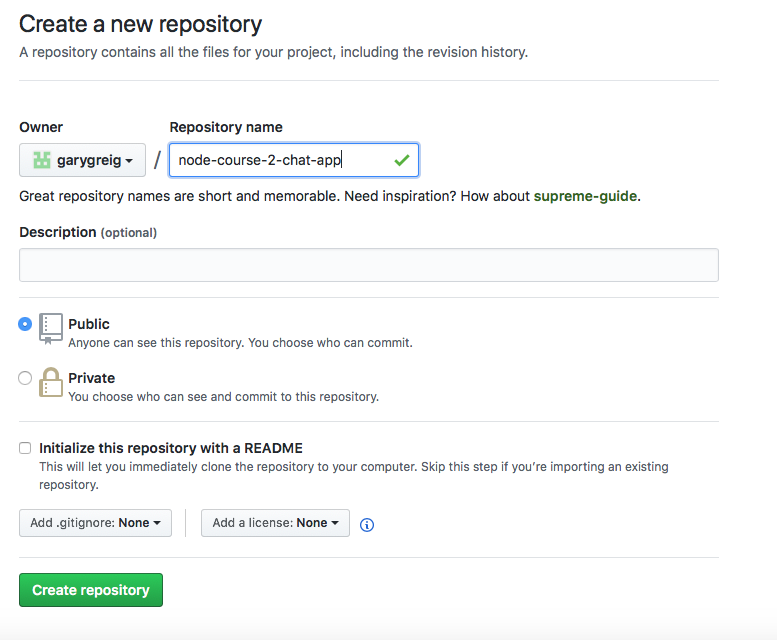

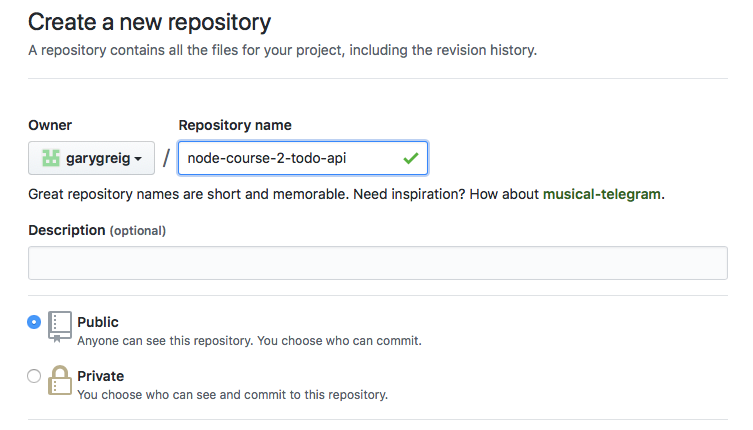

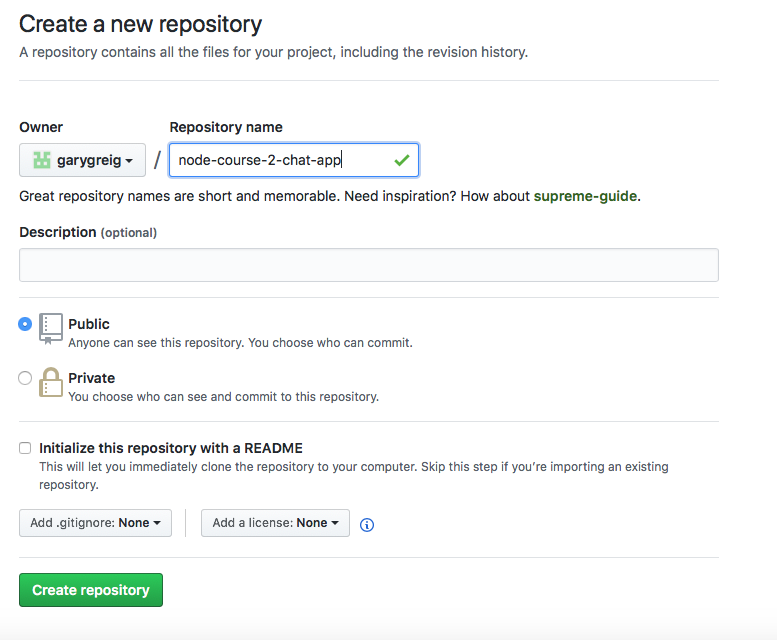

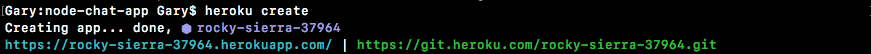

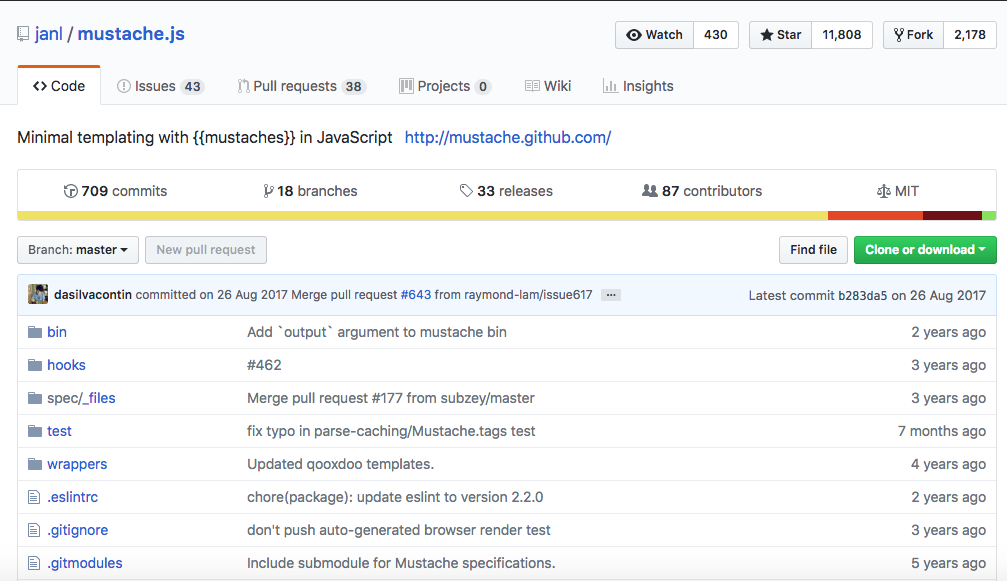

Now before we go, I do want to make a GitHub repository and get this code up there. This is going to require me to open up the browser and go to github.com. Once you're logged in we can make a new repo. I'm going to make a new repo and give it a name:

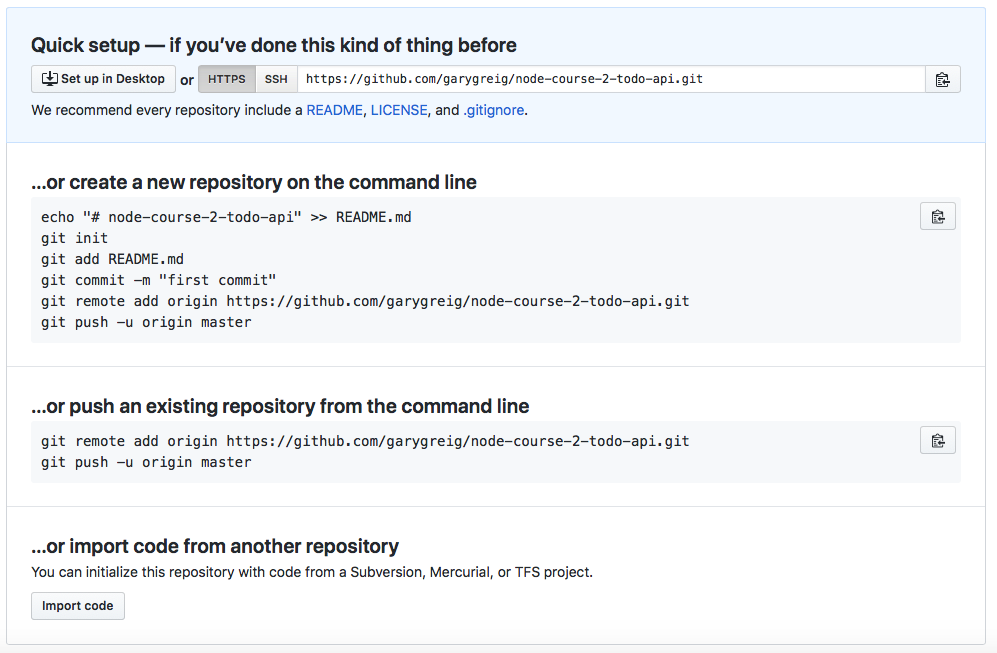

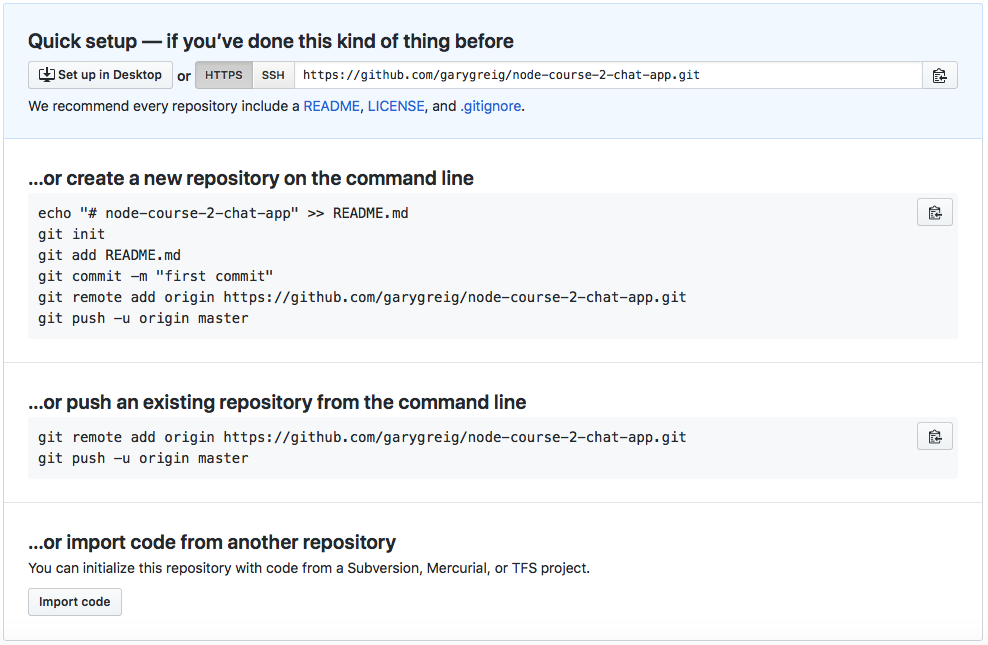

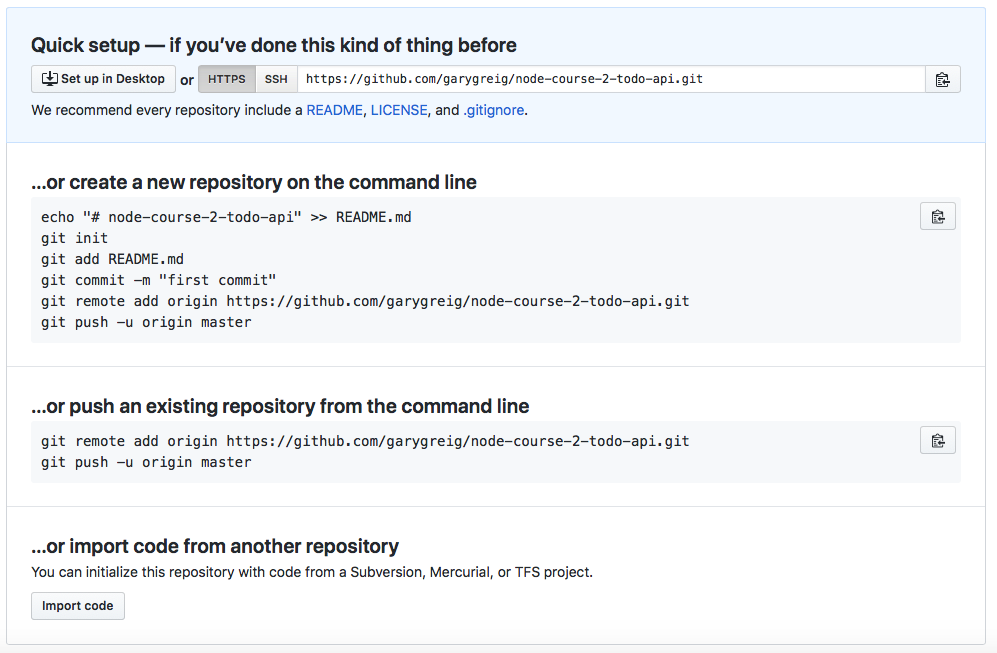

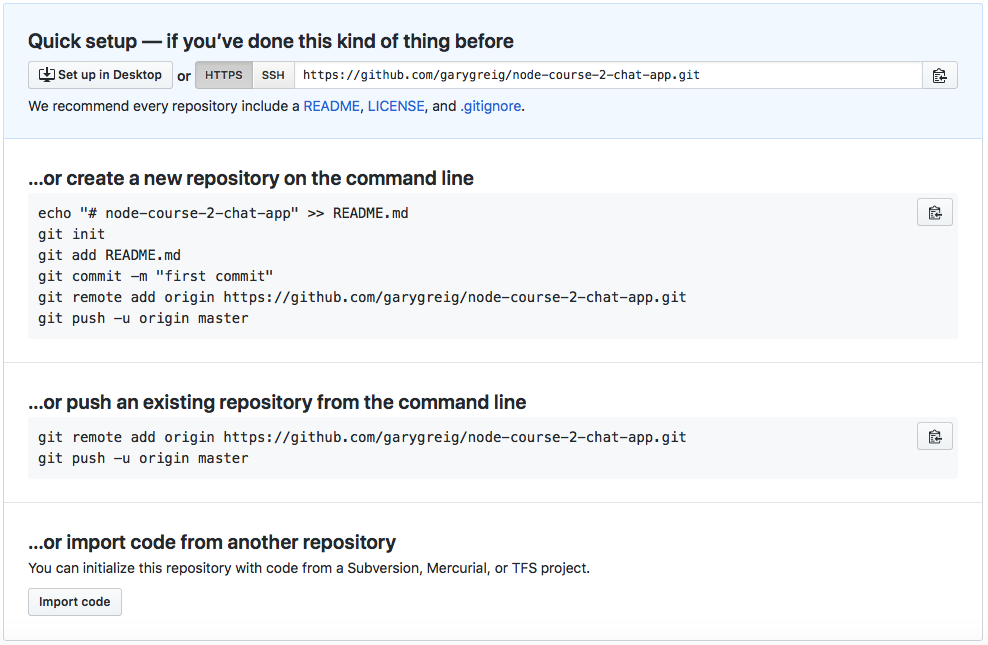

I'm going to go with node-course-2-todo-api. You can name yours something else if you wish. I'm going to go with this one to keep the course files organized. Now I can go ahead and create this repository, and as you may recall, GitHub actually gives us a few helpful commands:

In this case, we're pushing an existing repository from the command line. We already went through the steps of initializing the repository, adding our files and making our first commit. That means I can take the following two lines, copy them, head over to the Terminal, and paste them in:

git remote add origin https://github.com/garygreig/node-course-2-todo-api.git git push -u origin master

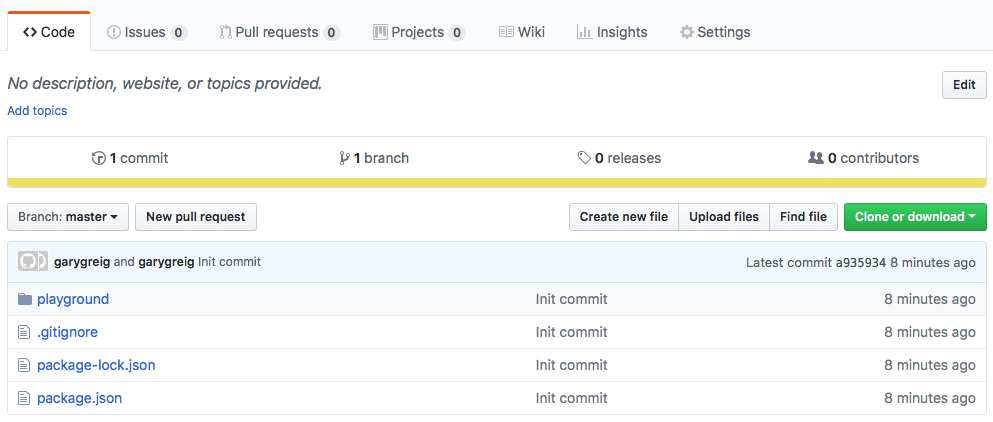

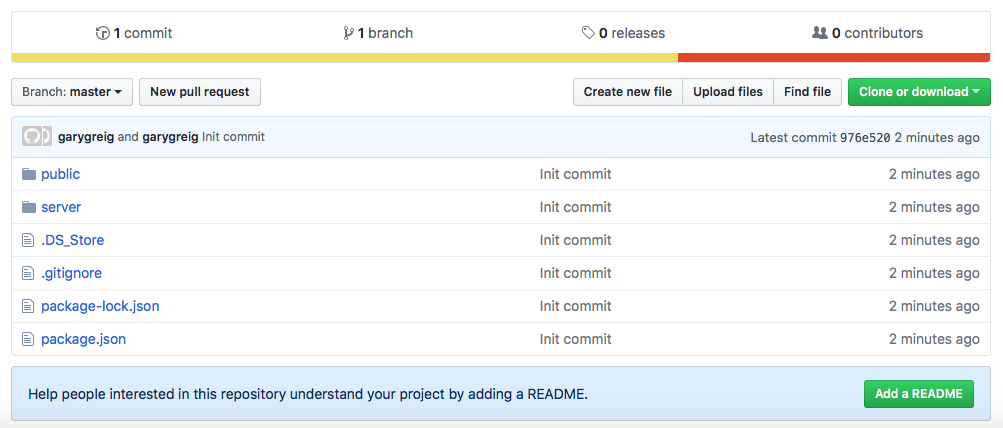

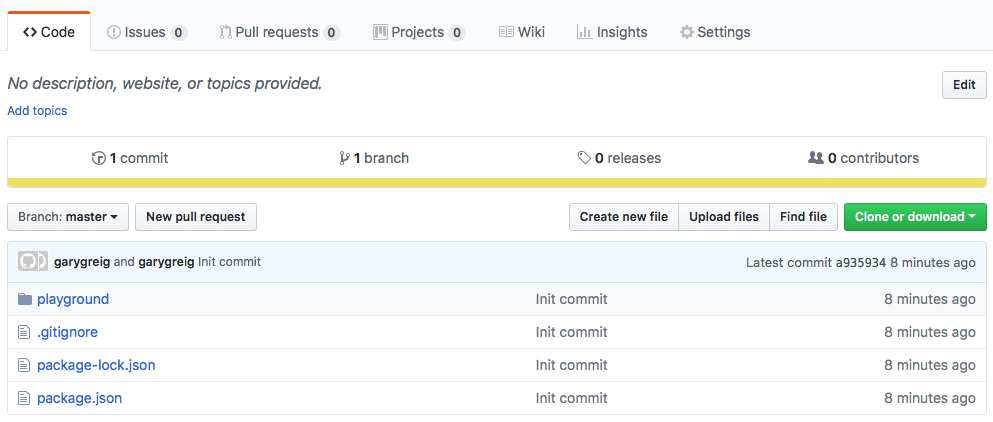

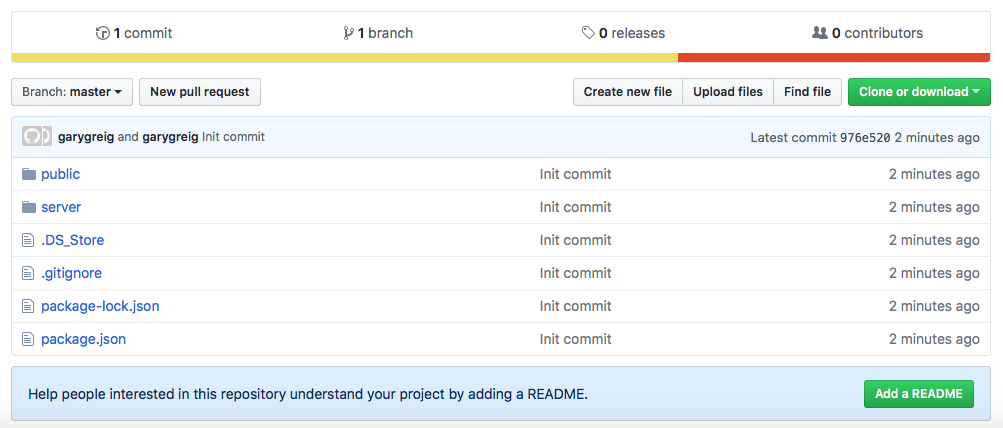

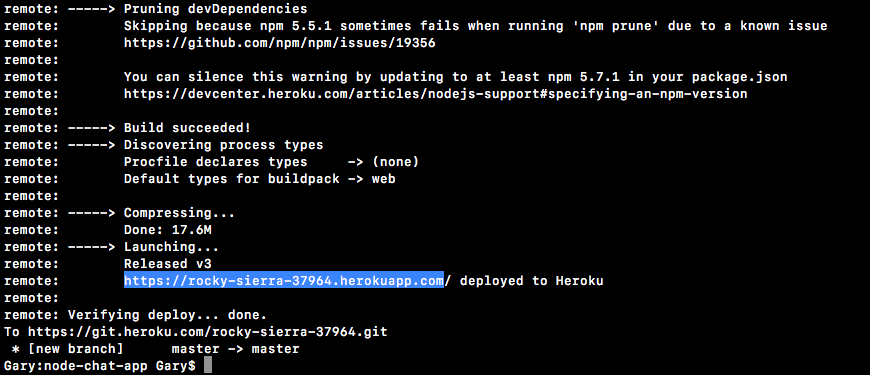

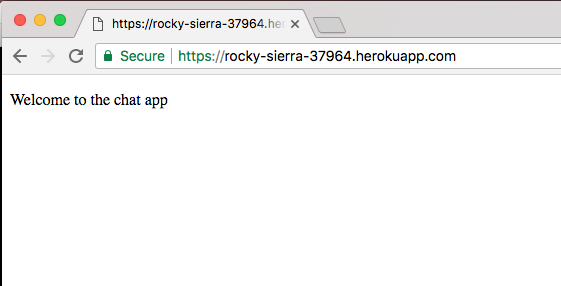

You might need to do these one at a time, depending on your operating system. On the Mac, when I try to paste in multiple commands it's going to run all but the last, and then I just have to hit enter to run the last one. Take a moment to knock that out for your operating system. You might need to run it as one command, or you might be able to paste it all in and hit enter. Either way, what we have here is our code pushed up to GitHub. I can prove that it's pushed up by refreshing the repository page:

Right there we have all of our source code, the .gitignore file, package.json, and we have our playground directory with our MongoDB scripts.

That's it for this section. We'll explore how to delete data from a MongoDB collection in the next section.

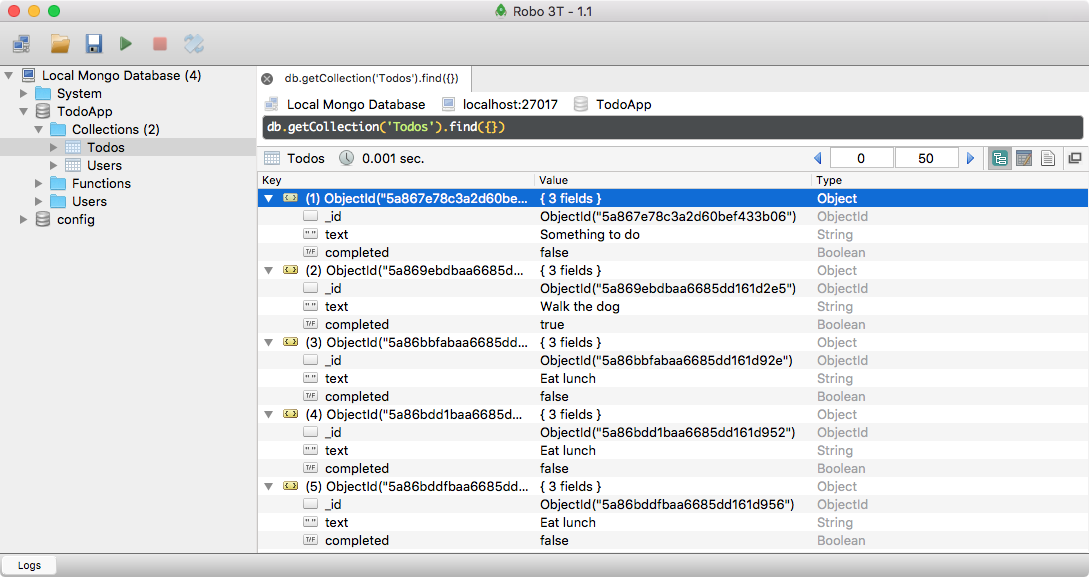

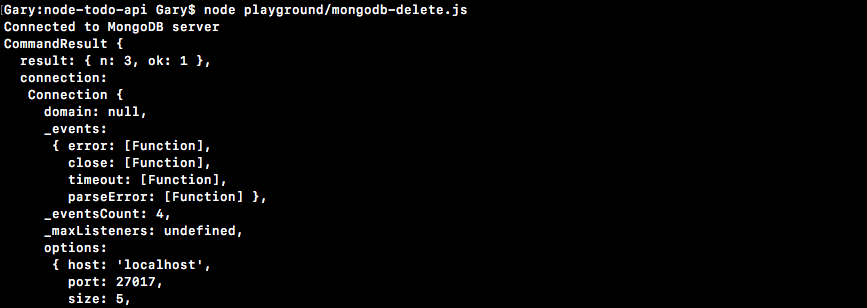

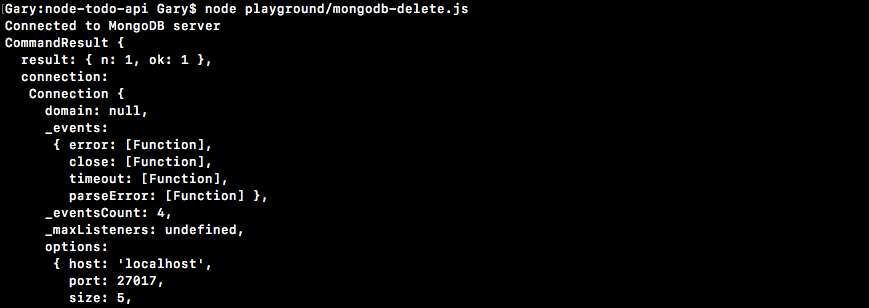

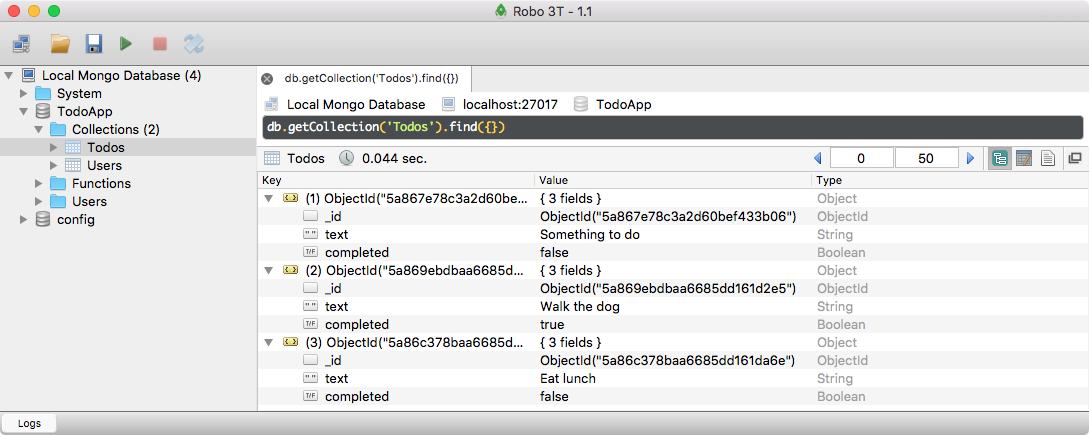

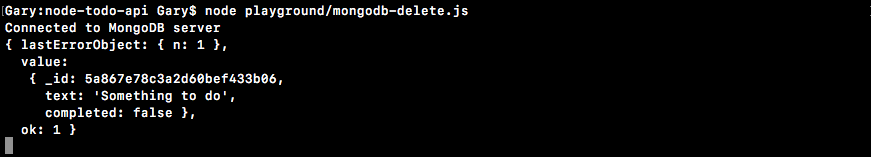

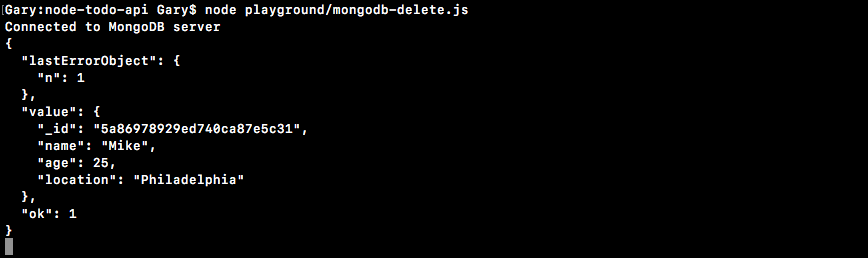

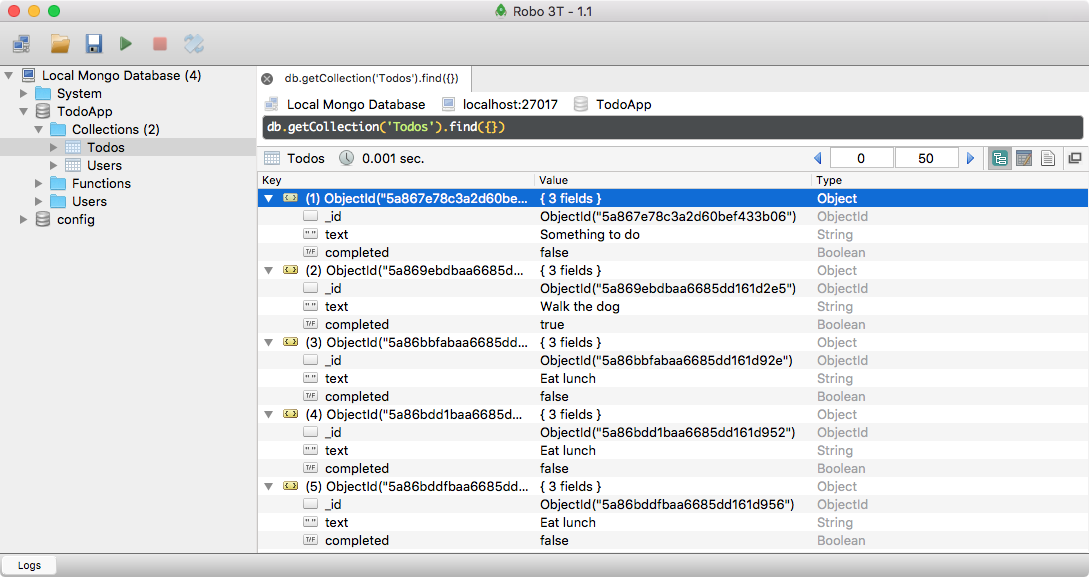

In this section, you're going to learn how to delete documents from your MongoDB collections. Before we get into that, in order to explore the methods that let us delete multiple documents or just one, we want to create a few more Todos. Currently, the Todos collection only has two items, and we're going to need a few more in order to play around with all these methods involving deletion.

Now, I do have two. I'm going to go ahead and create a third by right-clicking and then going to Insert Document.... We'll make a new document with a text property equal to something like Eat lunch, and we'll set completed equal to false:

{